Decoding Socio-Cultural Spatial Patterns in Historic Chinese Neighborhoods: A Pattern Language Approach from Chengdu

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Socio-Cultural Activities and Wellbeing in Urban Spaces

2.2. Spatial Quality and the Everyday Urban Fabric

2.3. Pattern Language as a Framework for Spatial Analysis

2.4. Identified Knowledge Gap

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sites Selection and Survey Scope

3.2. Research Design and Objectives

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Triangulation

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

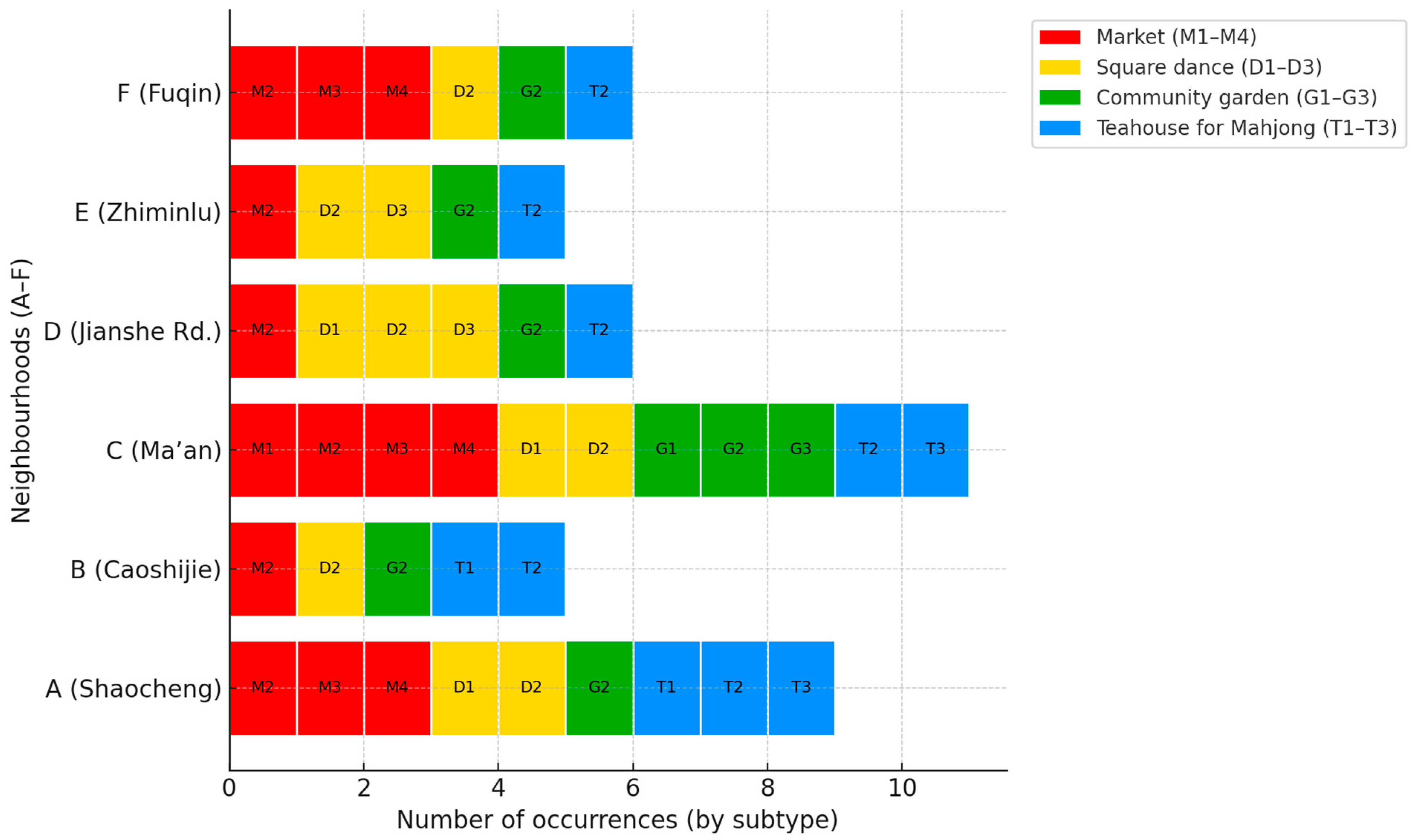

4.1. Overview of Observed Socio-Cultural Practices

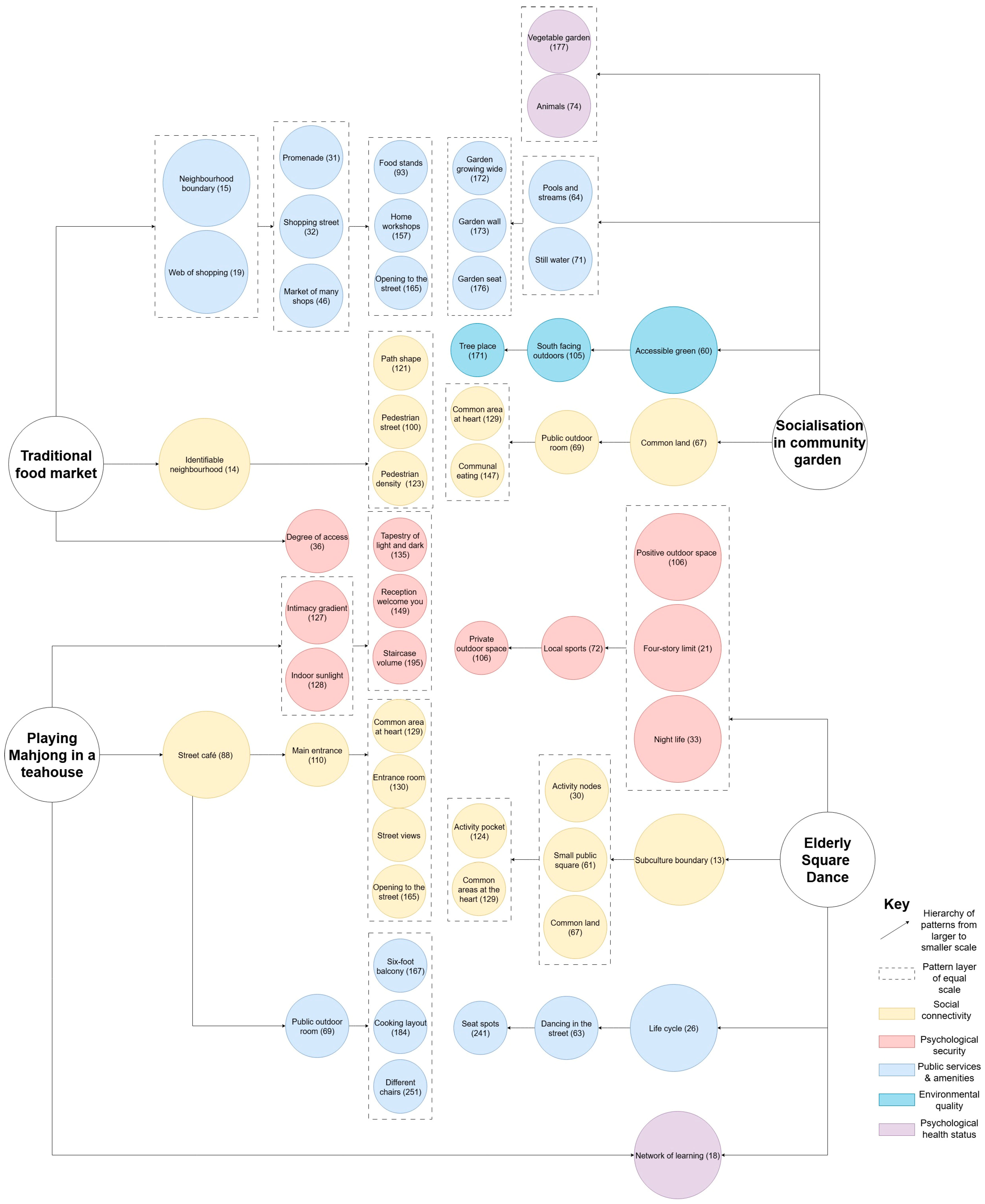

4.2. Spatial Analysis by Activity

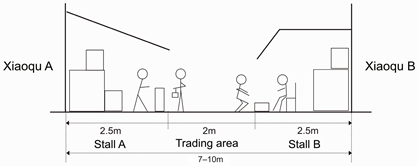

4.2.1. Traditional Food Market

4.2.2. Square Dance

4.2.3. Socialization in Community Gardens

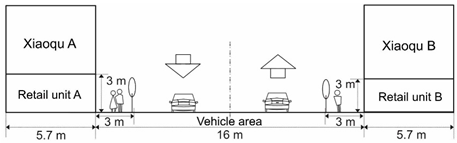

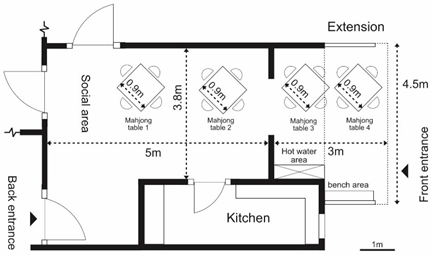

4.2.4. Teahouse for Playing Mahjong

4.2.5. Summary

4.3. Synthesis: Shared Carriers of Elderly Socio-Cultural Activities

5. Discussion

5.1. Corroboration

5.1.1. Patterns Parallel with ‘A Pattern Language’ and Supporting Elderly Wellbeing

5.1.2. Deviations and Additions Beyond Pattern Language

| Activity Code | Additional Patterns Found |

|---|---|

| M1—Informal food market |

|

| M2—Ground floor retail unit |

|

| M3—Large open-air markets |

|

| M4—Markets converted from former residential units |

|

| D1—Coupled dance |

|

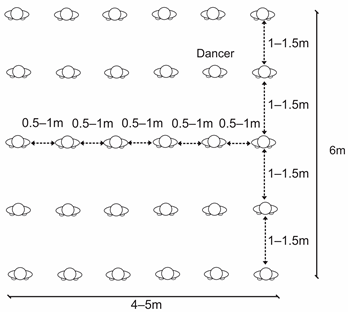

| D2—Dance in a matrix |

|

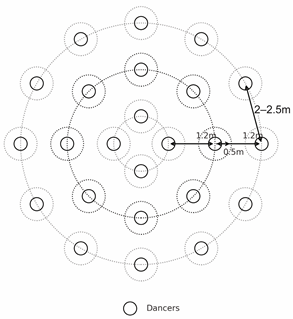

| D3—Circled dance |

|

| G1—Planned garden |

|

| G2—Informal gardens |

|

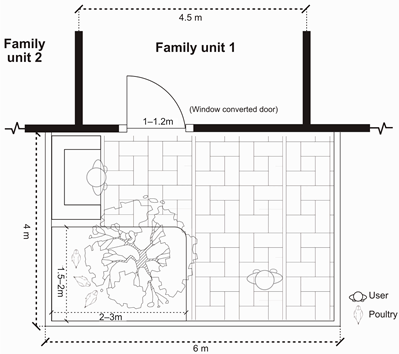

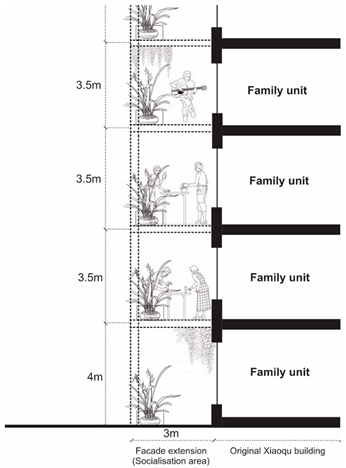

| G3—Vertical garden |

|

| T1—Ground floor family unit converted into a teahouse |

|

| T2—Original ground floor retail teahouse |

|

| T3—Outdoor teahouse |

|

5.2. A Pattern-Based Framework for Shared Public Space Making in Age-Friendly Regeneration

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Activities | Size | Patterns |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Food market | Large | Identifiable neighborhood (14), Neighborhood boundary (15), Web of shopping (19), |

| Medium | Promenade (31), Shopping street (32), Market of many shops (46), Degree of Publicness (36) | |

| Small | Food stands (93), Pedestrian street (100), Path shape (121), Home workshop (157) | |

| Elderly square dance | Large | Subculture boundary (13), Life cycle (26), Network of Learning (18), Four-story limit (21), Activity nodes (30), Night life (33) |

| Medium | Small public squares (61), Dancing in the street (63), Common land (67), Local sports (72) | |

| Small | Positive outdoor space (106), Activity pocket (124), Seat spots (241) | |

| Socialization in community garden | Large | Accessible green (60), Common land (67), Positive outdoor space (106) |

| Medium | Public outdoor room (69), Animals (74), South facing outdoors (105), Common area at the heart (129), Communal eating (147), Vegetable garden (177) | |

| Small | Pools and streams (64), Still water (71), Tree place (171), Garden growing wide (172), Garden wall (173), Garden seat (176) | |

| Playing Mahjong in teahouse | Large | Network of Learning (18), Street café (88), Street views (164), Opening to the street (165) |

| Medium | Public outdoor room (69), Main entrance (110), Intimacy gradient (127), Indoor sunlight (128), Common area at the heart (129), Tapestry of light and dark (135), Reception welcomes you (149) | |

| Small | Six-foot balcony (167), Cooking layout (184) |

Appendix A.2

| 1. General Information |

|

| 2. Spatial Setting |

|

| □ Alley |

| □ Courtyard |

| □ Market stall zone |

| □ Teahouse exterior |

| □ Square/open paved area |

| □ Garden edge/green fringe |

| □ Building threshold/corridor |

|

| 3. Activities and Behavioral Patterns |

|

| □ Square dancing |

| □ Mahjong playing |

| □ Gardening or plant care |

| □ Market vending |

| □ Informal gathering/chatting |

| □ Child play |

| □ Solitary use (e.g., resting, stretching, cleaning) |

| □ Other (specify): ___________________________ |

|

| 4. Spatial Interactions and Social Dynamics |

|

| 5. Environmental Qualities (relevant to Pattern Language) |

|

| 6. Observer Reflections |

|

Appendix B

| Shared Public-Space Type | Activity Subtypes | Supporting Patterns (Canonical + Additional) | Design Strategies (Condensed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear pedestrian corridor | M1, M2, D1 | Shopping Street (32); Food Stands (93); Web of Shopping (19); Path Shape (121); Activity Nodes (30); M1-1; M1-4; M2-1; D1-3 | Preserve continuous spine; add shaded stalls + low seating at thresholds; create 4–6 m pockets/lay-bys; protect flow continuity |

| Inner neighborhood courtyard | M3, D2, G2, T3 | Market of Many Shops (46); Home Workshop (157); Dancing in the Street (63); Positive Outdoor Space (106); Garden Wall (173); M3-1; M3-3; D2-2; G2-2; T3-1 | Hybrid layouts with visual openness; uninterrupted surfaces framed by benches; shade + permeable edges for T3; tap/compost points for G2 |

| Corridor/street corner | M1, D1 | Shopping Street (32); Food Stands (93); Activity Nodes (30); Night Life (33); Subculture Boundary (13); M1-4; D1-3 | Formalize 4–6 m corner pockets; ambient lighting; soft paving; queue/edge management that keeps the spine clear |

| Residential shopfront/downstairs | M4, G3, T3 | Promenade (31); Identifiable Neighborhood (14); Garden Wall (173); Street Views (164); M4-3; G3-1; T3-2 | Maintain semi-permeable thresholds (half-open doors, see-through screens); visible forecourt seating; shaded, non-blocking portable tables |

| Small residual square | D1, G2 | Activity Nodes (30); Positive Outdoor Space (106); Garden Wall (173); D1-3; G2-2 | Widen pockets to 4–6 m; perimeter benches/lean-rails; edge planting with tap access; keep sightlines clear |

| Formal plaza/civic square | D2, D3 | Common Area at the Heart (129); Life Cycle (26); Dancing in the Street (63); Positive Outdoor Space (106); D2-2; D3-2 | Keep effective width 14–21 m; continuous perimeter seating; low-glare evening lighting; provide shade structures |

| Community park | D3, G1, G2 | Accessible Green (60); Vegetable Garden (177); Garden Growing Wild (172); Common Area at the Heart (129); G1-1; G2-2; D3-3 | Shade along paths; visible small plots at edges; safe cross-views to dance areas; provide water access and storage |

| Community edge | M4, D2, G2 | Promenade (31); Identifiable Neighborhood (14); Street Views (164); Positive Outdoor Space (106); M4-1; D2-1; G2-3 | Soften hard gates; mark semi-permeable community fronts; edge seating + lighting; maintain clear entrances |

| Vertical thresholds (balconies) | G3 | Garden Wall (173); Indoor Sunlight (128); G3-1; G3-2 | Encourage rail planters/trellises; safe fixings + drip trays; support resident-driven greening |

| Indoor communal room | T1, T2 | Opening to the Street (165); Indoor Sunlight (128); Public Outdoor Room (69); Street Café (88); T1-1; T1-2; T2-1; T2-3 | Soft thresholds and flexible furniture; warm ambient lighting; accessible seating plans; preserve social acoustics of play |

| Shared public-space type | Activity subtypes | Supporting patterns (canonical + additional) | Design strategies (condensed) |

| 1 | Chinese square dance is an evening group dance in public spaces, mainly among older residents, for exercise and social bonding. |

| 2 | The number denotes the numeric patterns from ‘A Pattern Language’ book by Chirstopher Alexander. |

References

- Ruan, J.; Zheng, W.; Zhuang, Y. Everyday life experiences of Chinese community-dwelling oldest old who live alone at home. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2253937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Sunikka-Blank, M. Urban densification and social capital: Neighbourhood restructuring in Jinan, China. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing neighbourhood cohesion under the impact of urban redevelopment: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, T. Subjective Well-Being of Historical Neighborhood Residents in Beijing: The Impact on the Residential Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Shang, Q.; Bu, Q. Consequences of living environment insecurity on health and well-being in southwest China: The role of community cohesion and social support. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e6414–e6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Kong, L.; Lin, G.C.S. Interpreting China’s new urban spaces: State, market, and society in action. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Chen, X. Demolition, Rehabilitation, and Conservation: Heritage in Shanghai’s Urban Regeneration, 1990–2015. J. Archit. Urban. 2017, 41, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dijst, M.; Van Acker, V.; Chai, Y. Understanding effects of daily activity on neighborhood belongingness: A Chinese perspective. Cities 2025, 158, 105680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Zhou, R.; Xing, Z.; Guo, W. Micro-resilience assessment tool for living streets: Development, testing, and application in Chinese Jiangnan’s small and medium-sized cities. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, F. Micro-regeneration and participatory governance: A local social governance experiment in China. J. Chin. Gov. 2025, 10, 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Che, T.; Wu, Y. Community well-being service supply to the urban elderly based on preferred sequence demand: A case study in Zhenhai district, Ningbo. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Qiao, G.; Zhang, G.; He, X.; Ma, R. Multifaceted impacts of double-aging neighborhood’s built environments on SAIP: A deep dive into Chinese rapidly aging urban society. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1504195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961; 458p. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Behavior in Public Places: Notes on the Social Organization of Gatherings; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space, Reprint of 1974 original ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments. Developing age-friendly cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoof, J.; Kazak, J.K.; Perek-Białas, J.M.; Peek, S.T.M. The Challenges of Urban Ageing: Making Cities Age-Friendly in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977; p. 1171. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Bos-de Vos, M.; Mulder, I.; van Eldik, Z. Navigating Approaches to the Use of Pattern Language Theory in Practice. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Biljecki, F.; Kraak, M.-J. Formalising the urban pattern language: A morphological paradigm towards understanding the multi-scalar spatial structure of cities. Cities 2025, 161, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.; Weng, L.-J.; Botticello, A.L. Social participation reduces depressive symptoms among older adults: An 18-year longitudinal analysis in Taiwan. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Bai, X.; Feng, N. Social participation and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults: A study on rural–urban differences. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Zhou, H.; He, Z. The mediating role of psychological resilience between social participation and life satisfaction among older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Dai, W.; Liu, J.; Tao, J. Less Social Participation Is Associated With a Higher Risk of Depressive Symptoms Among Chinese Older Adults: A Community-Based Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 781771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Maliki, N.; Wang, Y. The Role of Urban Parks in Promoting Social Interaction of Older Adults in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.-Y. The impact of social participation on the quality of life among older adults in China: A chain mediation analysis of loneliness, depression, and anxiety. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1473657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, B.; Dong, L.; Zheng, T.; Wu, R. The Moderating Effect of Social Participation on the Relationship between Urban Green Space and the Mental Health of Older Adults: A Case Study in China. Land 2024, 13, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeljić-Mihailović, N.; Brkić-Jovanović, N.; Krstić, T.; Simin, D.; Milutinović, D. Social participation and depressive symptoms among older adults during the Covid-19 pandemic in Serbia: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 44, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, M.; Wang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Yu, X.; Tian, K. The impact of social participation on mental health among the older adult in China: An analysis based on the mental frailty index. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1557513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, D. Impact of living patterns and social participation on the health vulnerability of urban and rural older persons in Jiangsu Province, China. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, J.; Xia, B.; Chen, Q.; Buys, L.; Susilawati, C.; Drogemuller, R. Impact of the Built Environment on Ageing in Place: A Systematic Overview of Reviews. Buildings 2024, 14, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoof, J.; Marston, H.R.; Kazak, J.K.; Buffel, T. Ten questions concerning age-friendly cities and communities and the built environment. Build. Environ. 2021, 199, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, D.W.; Barnett, A.; Nathan, A.; Van Cauwenberg, J.; Cerin, E.; Council on Environment and Physical Activity (CEPA)–Older Adults Working Group. Built environmental correlates of older adults’ total physical activity and walking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, M.; Eloy, S.; Marques, S.; Dias, L. Older people perceptions on the built environment: A scoping review. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 108, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Taplin, D.; Scheld, S. Rethinking Urban Parks: Public Space & Cultural Diversity; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. Collective culture and urban public space. City 2008, 12, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Q.; Thai, H.M.H. Mapping the character of urban districts: The morphology, land use and visual character of Chinatowns. Cities 2024, 148, 104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, S.; Xia, C.; Tung, C.-L. Investigating the effects of urban morphology on vitality of community life circles using machine learning and geospatial approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 167, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, W. The Return of Public Life: The Teahouse, Urban Citizens, and Socialist State In Post-Mao China. Quad. Stor. 2015, 50, 409–437. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Nanchizi New Courtyard Housing in Beijing: Residents’ Perceptions and Experiences of the Redevelopment. JCAU 2020, 2, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Liu, T.; Deng, J.; Yu, X.; Liao, S.; Shen, K. The importance, performance analysis and improvement of township traditional market environment based on behavioural demand—Taking Taoyuan County Market in Hunan Province as an example. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 23, 1500–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y. Transforming Public Spaces in Post-Socialist China’s Danwei Neighbourhoods: The Third Dormitory of the Party Committee of Shandong Province. Urban Plan. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Kita, M.; Matsubara, S.; Okyere, S.A.; Shimoda, M. Socio-Spatial Changes in Danwei Neighbourhoods: A Case Study of the AMS Danwei Compound in Hefei, China. Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, H.; Cao, X.; Yue, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, H. Spatial quality measurement of commercial streets in old cities of medium-sized cities in China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 3070–3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liao, J.; Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Shang, A.; Huang, Z. Evaluating the Spatial Quality of Urban Living Streets: A Case Study of Hengyang City in Central South China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, M. A Study on the Influencing Factors of the Vitality of Street Corner Spaces in Historic Districts: The Case of Shanghai Bund Historic District. Buildings 2024, 14, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; He, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, C. The Relationship Between Built Environment and Mental Health of Older Adults: Mediating Effects of Perceptions of Community Cohesion and Community Safety and the Moderating Effect of Income. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 881169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, F.; Schwanen, T. ‘I like to go out to be energised by different people’: An exploratory analysis of mobility and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Chen, Z.-l.; Wei, Y.; Gu, N.; Tang, S.-l. Examining dynamic developmental trends: The interrelationship between age-friendly environments and healthy aging in the Chinese population—Evidence from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, 2011–2018. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J. Developing a cultural sustainability assessment framework for environmental facilities in urban communities. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwani, A.B.; Maliki, H.T.; Mawlan, K.A. Spatiality of Outdoor Social Activities in Neighborhood Urban Spaces: An Empirical Investigation in Erbil City Neighborhoods. Buildings 2025, 15, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hakimi, H.A.; Azmi, N.F.; Li, K.; Duan, B. A Framework for Heritage-Led Regeneration in Chinese Traditional Villages: Systematic Literature Review and Experts’ Interview. Heritage 2025, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Urban Vitality Measurement and Influence Mechanism Detection in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Z. A review of urban vitality research in the Chinese world. Trans. Urban Data Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA; Chichester, UK, 1998; pp. 314–367. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes, M.; Ostwald, M. Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language: Analysing, mapping and classifying the critical response. City Territ. Archit. 2017, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, B.S. Generative processes for revitalizing historic towns or heritage districts. Urban Des. Int. 2007, 12, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felstead, A.; Thwaites, K. Grounded Patterns: Creating a Socio-Spatial Language for Residents’ Participation in Cohousing Landscapes; University of Strathclyde Publishing: Glasgow, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Namwanje, P.; Munoz Sanz, V.; Rocco, R. The Pattern Language Approach as a Bridge Connecting Formal and Informal Urban Planning Practices in Africa. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Nijhuis, S.; Dijkstra, R. Towards a pattern language for green space design in high density urban developments. J. Urban Des. 2024, 29, 576–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.; Hanks, L.; Wang, Q. Extracting a local pattern language: A case study of Khartoum’s City Centre. Urban Des. Int. 2024, 29, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Li, H. Urban morphology and local citizens in China’s historic neighborhoods: A case study of the Stele Forest Neighborhood in Xi’an. Cities 2017, 71, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, H. Pedestrian vitality characteristics in pedestrianized commercial streets-considering temporal, spatial, and built environment factors. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Abd Malek, M.I.; Ja’afar, N.H.; Sima, Y.; Han, Z.; Liu, Z. Unveiling the potential of space syntax approach for revitalizing historic urban areas: A case study of Yushan Historic District, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 1144–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Public space and its publicness in people-oriented urban regeneration: A case study of Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 2319–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Gu, T. Comparative analysis of spatial patterns and driving factors of historic districts in the Chinese four ancient capitals. npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kidokoro, T.; Seta, F.; Shu, B. Spatial-Temporal Assessment of Urban Resilience to Disasters: A Case Study in Chengdu, China. Land 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.; Zhang, J.; Yee, S.J.; Goh, C.K. Chengdu, where the everyday becomes art [Eye on Sichuan series]; ThinkChina: Singapore. 2025. Available online: https://www.thinkchina.sg/culture/chengdu-where-everyday-becomes-art-eye-sichuan-series (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Bishop, K.; Marshall, N.; Rahmat, H.; Thompson, S.; Steinmetz-Weiss, C.; Corkery, L.; Tietz, C.; Park, M. Behavior Mapping and Its Application in Smart Social Spaces. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.; Campbell, G.; Gregg, M. Real Time Search User Behavior; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 3961–3966. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J. Observation for Data Collection in Urban Studies and Urban Analysis; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Oswald, F. Environmental Perspectives on Aging; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, 6th ed.; The Danish Architectural Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; pp. 7–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, C.; Gallacher, J.; Webster, C. Urban built environment configuration and psychological distress in older men: Results from the Caerphilly study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Cao, X. Improving Care for Elders Who Prefer Informal Spaces to Age-Separated Institutions and Health Care Settings. Innov. Aging 2019, 3, igz019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E. Ageing and the City: Making Urban Spaces Work for Older People; HelpAge International: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Yang, Z.; Cui, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Liu, Y. Age-Friendly Public-Space Retrofit in Peri-Urban Villages Using Space Syntax and Exploratory Factor Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, C.; Carpentieri, G.; Masoumi, H. Measuring spatial accessibility to urban services for older adults: An application to healthcare facilities in Milan. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fancello, G.; Vallée, J.; Sueur, C.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Kestens, Y.; Montanari, A.; Chaix, B. Micro urban spaces and mental well-being: Measuring the exposure to urban landscapes along daily mobility paths and their effects on momentary depressive symptomatology among older population. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Barnett, A.; Zhang, C.J.P.; Lai, P.-C.; Sit, C.H.P.; Lee, R.S.Y. How urban densification shapes walking behaviours in older community dwellers: A cross-sectional analysis of potential pathways of influence. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.; Chalfin, A. Ambient lighting, use of outdoor spaces and perceptions of public safety: Evidence from a survey experiment. Secur. J. 2021, 35, 694–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, R.L.; Caponecchia, C.D.; Gopaldasani, V. Impact of Public Seating Design on Mobility and Independence of Older Adults. Exp. Aging Res. 2021, 47, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, H.; Oswald, F. Advancing understanding of person-environment interaction in later life: One step further. J. Aging Stud. 2019, 51, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Francis, C. People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Li, C. A phenomenological exploration of the square dance among the Chinese elderly in urbanised communities. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2021, 28, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces; Conservation Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen, T.; Portegijs, E.; Viljanen, A.; Eronen, J.; Saajanaho, M.; Tsai, L.-T.; Kauppinen, M.; Palonen, E.-M.; Sipilä, S.; Iwarsson, S.; et al. Individual and environmental factors underlying life space of older people-study protocol and design of a cohort study on life-space mobility in old age (LISPE). BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Ehrenfeucht, R. Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.; Kang, J. Soundscape and Sound Preferences in Urban Squares: A Case Study in Sheffield. J. Urban Des. 2005, 10, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraei, M.; Paxton, A.; Xygalatas, D. Aligned bodies, united hearts: Embodied emotional dynamics of an Islamic ritual. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2024, 379, 20230162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.; Franke, T.; McKay, H.; Sims-Gould, J. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health Place 2015, 34, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.L.; Masser, B.M.; Pachana, N.A. Positive aging benefits of home and community gardening activities: Older adults report enhanced self-esteem, productive endeavours, social engagement and exercise. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120901732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yanai, S.; Xu, G. Community gardens and psychological well-being among older people in elderly housing with care services: The role of the social environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 94, 102232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjaestad, S.L.; Mackelprang, J.L.; Sugiyama, T.; Chandrabose, M.; Owen, N.; Turrell, G.; Kingsley, J. Associations of time spent gardening with mental wellbeing and life satisfaction in mid-to-late adulthood. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 87, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M.T.S.; Roxas, M.E.D. Fifty Shades of Green: Vertical Gardening by the Elderly as Expression of Creativity and Empowerment. J. Nat. Stud. 2019, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, T.; Costa, J.; Santos, O.; Sousa, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Freire, E. Evidence on the contribution of community gardens to promote physical and mental health and well-being of non-institutionalized individuals: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, I. Feeling at home in contemporary Japan: Space, atmosphere and intimacy. Emot. Space Soc. 2014, 15, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Flowers, E.; Ball, K.; Deforche, B.; Timperio, A. Designing parks for older adults: A qualitative study using walk-along interviews. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 54, 126768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, T.; Ward Thompson, C. Older people’s health, outdoor activity and supportiveness of neighbourhood environments. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.; Conejos, S.; Chan, E. Social needs of the elderly and active ageing in public open spaces in urban renewal. Cities 2015, 52, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Soltani, S. Behaviors of seniors and impact of spatial form in small-scale public spaces in Chinese old city zones. Cities 2020, 107, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padeiro, M.; de São José, J.; Amado, C.; Sousa, L.; Roma Oliveira, C.; Esteves, A.; McGarrigle, J. Neighborhood Attributes and Well-Being Among Older Adults in Urban Areas: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Res. Aging 2022, 44, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, E.; Maing, M. Influential factors of age-friendly neighborhood open space under high-density high-rise housing context in hot weather: A case study of public housing in Hong Kong. Cities 2021, 115, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, B. Singing together in the park: Older peoples’ wellbeing and the singingscape in Guangzhou, China. Emot. Space Soc. 2023, 47, 100947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Chau, H.W.; Abe, T.; Kato, Y.; Jamei, E.; Veeroja, P.; Mori, K.; Sugiyama, T. Third Places for Older Adults’ Social Engagement: A Scoping Review and Research Agenda. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Activities | Frequency | A 1 | B | C | D | E | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Traditional food markets | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Square dancing | 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Street-side vendors | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Public chess playing | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Playing Mahjong in teahouses | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Street water calligraphy writing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Community street haircuts | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Community gardening | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| M1—Informal food market 1 | Pattern matches |

| Identifiable Neighborhood (14), Web of Shopping (19), Promenade (31), Market of Many Shops (46), Food Stands (93), Pedestrian Street (100) |

| |

| M2—Ground floor retail unit | |

| Neighborhood Boundary (15), Shopping Street (32), Degree of Publicness (36), Path Shape (121) |

| M3—Large open-air markets | |

| Market of Many Shops (46), Home Workshop (157), Path Shape (121), Food Stands (93) |

| M4—Markets converted from former residential units | |

| Identifiable Neighbourhood (14), Promenade (31), Shopping Street (32), Pedestrian Street (100) |

| D1—Coupled dance | Patterns matches |

| Subculture Boundary (13), Activity Nodes (30), Night Life (33), Common Land (67), Small Public Squares (61) |

| D2—Dance in a matrix | |

| Dancing in the Street (63), Local Sports (72), Activity Pocket (124), Positive Outdoor Space (106), Seat Spots (241) |

| D3—Circled dance | |

| Common Area at the Heart (129), Indoor Sunlight (128), Network of Learning (18), Life Cycle (26) |

| G1—Planned garden | Pattern matches |

| Accessible Green (60), Common Land (67), Positive Outdoor Space (106), Public Outdoor Room (69), Communal Eating (147), Vegetable Garden (177) |

| G2—Informal gardens | |

| Garden Growing Wild (172), Garden Wall (173), Garden Seat (176), Common Area at the Heart (129), South Facing Outdoors (105), Tree Place (171) |

| |

| G3—Vertical garden | |

| Life Cycle (26), South Facing Outdoors (105), Garden Wall (173), Garden Seat (176) |

| T1—Ground floor family unit converted into a teahouse | Pattern matches |

| Opening to the Street (165), Street Views (164), Street Café (88), Intimacy Gradient (127), Reception Welcomes You (149), Six-Foot Balcony (167) |

| T2—Original ground floor retail teahouse | |

| Indoor Sunlight (128), Common Area at the Heart (129), Main Entrance (110), Public Outdoor Room (69), Tapestry of Light and Dark (135), Network of Learning (18) |

| T3—Outdoor teahouse | |

| Street Views (164), Street Café (88), Opening to the Street (165) |

| Identified Shared Public Space | Activity Types Hosted | Sites Observed | Interviewee Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear pedestrian corridor | M1, M2, D1 | A, B, C, D, F |

|

| Inner neighborhood courtyard | M3, D2, G2, T3 | A, B, C, D, F |

|

| Corridor/street corner | M1, D1 | A, C, D |

|

| Residential shopfront/downstairs | M4, G3, T3 | C, D |

|

| Small residual square | D1, G2 | A, B, C, D, F |

|

| Formal plaza or civic square | D2, D3 | All |

|

| Community park | D3, G1, G2 | A, B, C, D, F |

|

| Community edge | M4, D2, G2 | All |

|

| Vertical thresholds (balconies) | G3 | D |

|

| Indoor communal room | T1, T2 | A, C |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Dimitrijevic, B. Decoding Socio-Cultural Spatial Patterns in Historic Chinese Neighborhoods: A Pattern Language Approach from Chengdu. Land 2025, 14, 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091803

Zhang Y, Dimitrijevic B. Decoding Socio-Cultural Spatial Patterns in Historic Chinese Neighborhoods: A Pattern Language Approach from Chengdu. Land. 2025; 14(9):1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091803

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yaozhong, and Branka Dimitrijevic. 2025. "Decoding Socio-Cultural Spatial Patterns in Historic Chinese Neighborhoods: A Pattern Language Approach from Chengdu" Land 14, no. 9: 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091803

APA StyleZhang, Y., & Dimitrijevic, B. (2025). Decoding Socio-Cultural Spatial Patterns in Historic Chinese Neighborhoods: A Pattern Language Approach from Chengdu. Land, 14(9), 1803. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091803