1. Introduction

Wilson’s “Biophilia Theory” posits that the desire to connect with nature stems from an innate bond between humans and the natural world [

1]. As urbanization increases, people tend to seek contact with nature and expect both psychological and physical benefits from it. Research has shown that natural environments can aid in health restoration, stress relief, cognitive function improvement, and enhanced mood and well-being [

2,

3,

4,

5]. However, rapid industrialization and urbanization have caused severe degradation of the urban natural environment and a sharp decline in the growth of urban green spaces, both of which have increased the risk of declining public health [

2]. As nations increasingly prioritize public health and well-being, offering more accessible and multifunctional nature-based spaces within urban settings has become a key issue in urban planning [

6]. Given the high cost and limited availability of urban land, enhancing the value of urban green spaces and promoting residents’ quality of life and emotional well-being have become key concerns for urban planners and managers. Among various types of urban green spaces, urban forests have been identified as an important form of green space for urban populations [

7]. Benefits associated with exposure to urban forest environments include physical and mental well-being, vitality, recreation, health, aesthetic enjoyment, and a sense of connection with nature [

8,

9,

10]. As a specific form of urban forest, urban forest parks combine the natural characteristics of forests with the structural features of urban parks. Research has shown that parks with forested areas offer greater benefits than other types of green spaces [

11]. Nevertheless, the extent to which these benefits are realized may depend on individual psychological factors and situational contexts. Therefore, it is important to recognize that exposure to nature alone does not necessarily lead to positive psychological outcomes [

12]. Individuals’ motivations to visit urban green spaces are closely related to their needs and expectations [

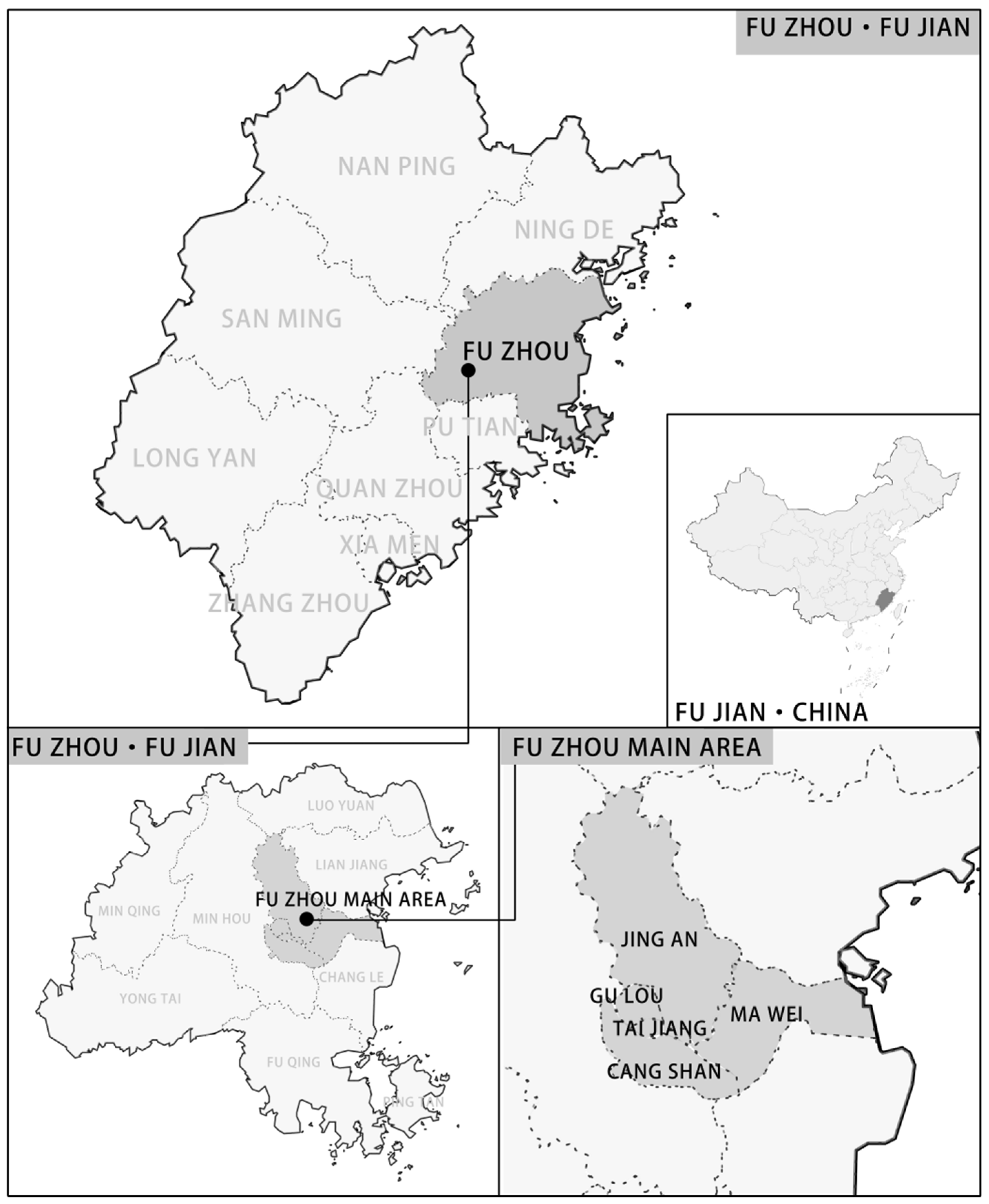

13], and different motivations may lead to different behavioral, emotional, and experiential outcomes. Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian Province in China, is a city with 58 forest-covered hills within its urban built-up area. This topographical feature is relatively rare. In the Fuzhou Green Space System Plan (2021–2035), the city set a strategic goal of building “A Blessed City with a Thousand Parks.” Therefore, it is crucial to understand why local residents choose to visit urban forest parks and whether their visiting motivations influence the positive emotional responses gained from nature exposure. This knowledge can support more effective planning, design, and management of urban forest parks, enhance their ecological and social value, and help meet public needs and expectations.

Visiting motivation refers to the internal psychological processes that initiate, direct, and sustain individuals’ physical and leisure activities toward one or more goals [

14]. Across the globe, studies on various types of urban green spaces have explored the diversity of motivations under different cultural contexts. For example, in Guangzhou, China, major motivations for visiting urban green spaces include enjoying fresh air and beautiful scenery, relaxation, exercise, peace and quiet, contact with nature, and playing with children. Social interaction was mentioned more frequently by older individuals [

15]. In Shanghai, the most common reasons for visiting small urban green spaces were relaxation and rest, physical exercise, and meeting friends, followed by taking children out, walking, and being in nature or fresh air [

16]. Teenagers in both Guangzhou and Australia reported similar motivations, such as relaxation, breathing fresh air, nature exposure, and escaping daily stress [

17,

18]. By contrast, in the Netherlands, adolescents primarily visited urban green spaces for sports and social activities [

19]. In South Korea, social media big data identified seven main motivations for visiting urban forests: “cafe-related walk,” “healing trip,” “daily leisure,” “family trip,” “wonderful view,” “clean space,” and “exhibition and photography.” In Malaysia, 74.7% of people visited urban green spaces to breathe fresh air, followed by stress relief, relaxation, exercise, games, and maintaining physical fitness [

20]. Norwegian adults typically cited nature experience, convenience, and body-oriented benefits as primary motivations for engaging in green exercise within urban green spaces [

21]. In Serbia, relaxation, tranquility, natural surroundings, and fresh air were the dominant motivations for park visitation [

22]. In Coimbra, Portugal, landscape beauty, spatial tranquility, the presence of water, and accessibility were the most fundamental factors influencing park choice. In contrast, park size, access to sports facilities, and opportunities for social interaction varied across different types of urban green space [

23]. For residents in Vilnius, Lithuania, external pull factors included leisure walking, enjoying fresh air, observing nature, relaxing, and engaging in physical activities. Common internal push factors were proximity and a sense of safety [

24]. A survey conducted in three European cities found that proximity and accessibility were the most important motivations overall. Physical space for activity was more favored by younger users, while older adults preferred nature, landscape, or wilderness. Social or cultural interaction was considered the least important factor [

25]. These studies highlight differences in urban green space visit motivations across cities. For instance, “close to home or accessible” was a strong motivation in Lithuania and other European cities, but not in Guangzhou, Malaysia, or Norway. Fresh air was a dominant motivation for residents in Guangzhou, Malaysia, Serbia, and Lithuania, but was less common in Korea and Portugal. Social interaction was a less important motivation in Guangzhou and many European cities, but played a more prominent role in Shanghai.

Compared to the extensive research on motivations, barriers to use have received relatively less academic attention. Barriers function as inhibitors of Behaviour and may also serve as external indicators of an individual’s lack of amotivation. Accessibility issues are among the most frequently reported physical barriers [

26,

27]. For instance, visitation rates decline significantly when the distance to green spaces exceeds 300–400 m [

28]. A travel time of 30 min often serves as a psychological threshold for potential visitors [

15]. Time-related constraints are also recognized as a significant social barrier. Lack of time and poor accessibility are commonly cited obstacles to park use [

21]. Other prominent barriers include work obligations, household responsibilities, poor health, and adverse weather conditions [

29]. Vulnerable groups, such as parents with young children, older adults with limited mobility, and individuals with chronic illnesses or disabilities, face particular challenges in accessing urban green spaces [

30]. Aging and health-related issues are especially salient obstacles [

29]. Additionally, certain spatial features, such as complex path layouts, difficult terrain, inadequate lighting, and dense vegetation, can indirectly discourage use by reducing confidence and motivation [

31]. Safety concerns are also critical [

31]. Damaged facilities, insufficient lighting, unclean areas, pet waste, graffiti, and vandalism all contribute to negative perceptions of safety and heightened fear of crime [

32]. Some individuals report having no specific reason or express a lack of interest in urban green spaces [

29], which suggests the presence of psychological barriers related to motivational deficits.

Although studies have explored the motivations and constraints associated with urban green space use, most have focused on general urban green space types, with only a few targeting specific categories. Among them, research on urban forest parks remains limited, especially in the context of Chinese culture. Since motivations for visiting urban green spaces may vary by type, it is essential to accurately capture visit motivations specific to urban forest parks. On this basis, further exploration of the internal links between urban forest park visit motivations and positive emotional responses is warranted. Previous studies have shown that motivation is associated with a range of positive behavioral outcomes, such as higher engagement, enhanced positive emotions, stronger persistence, and greater satisfaction [

33,

34,

35]. Subjective well-being (SWB), as a key indicator of individuals’ life satisfaction and emotional status, is a comprehensive psychological evaluation that reflects an individual’s overall level of cognitive satisfaction with life and emotional experience over a given period. Its typical structure encompasses three dimensions: life satisfaction, positive affect, and negative affect [

36]. In contrast to traditional measures of happiness based on material conditions or external achievements, Subjective well-being emphasizes a state of feeling rather than having, representing a model of happiness centred on internal psychological experience. Ryan and Deci (2000) noted that, when individuals experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness in their activities, they tend to achieve higher levels of well-being, thereby providing a theoretical basis for understanding how motivation contributes to well-being [

37]. Empirical evidence suggests that park visitation frequency is positively associated with the well-being of urban residents [

38]. Individuals with easier access to green infrastructure or those living in aesthetically pleasing neighborhoods tend to report higher levels of well-being [

39]. Therefore, Subjective well-being has become an important indicator for assessing the psychological benefits that urban residents derive from engaging in green space activities. In various fields, such as psychology and management, empirical research has confirmed the significant effects of motivation and behavioral intention on individual well-being [

37,

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, most studies have examined motivation and behavioral intention separately, with limited research addressing the complex relationships among motivation, behavioral intention, and subjective well-being. These few studies are mainly situated in the field of tourism management. For example, a survey during the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that tourists’ positive emotions in daily life increased their motivations for “escape and relaxation,” “safety and convenience,” and “family interaction,” as well as their intention to revisit destinations, offering insights for tourism recovery [

44]. A recent study found that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of health-and-wellness tourists significantly predicted behavioral intention, with perceived value playing a partial mediating role [

45], highlighting the potential of intrinsic motivation in health tourism. In the domain of urban green space, existing studies have primarily used theoretical perspectives such as Attention Restoration Theory, Stress Recovery Theory, Biophilia Hypothesis, and Environmental Preference Theory to explain how urban green spaces affect physical and mental health and well-being. However, there remains a lack of understanding of how different types of urban forest park visit motivations and behavioral intentions interact to influence subjective well-being, particularly within a behavioral psychology framework.

Drawing from multiple theories of human behavioral motivation, this study adopts an integrated framework combining Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour to better understand the relationship between individuals’ motivations and behavioral intentions. Self-Determination Theory is one of the most widely applied theories in motivation research. Its key strength lies in its dynamic model structure [

37]. By categorizing different types of motivation and emphasizing basic psychological needs, Self-Determination Theory offers a powerful framework for understanding and promoting voluntary Behaviour. However, Self-Determination Theory does not specify the exact process through which motivation is transformed into intention and Behaviour. In contrast, the Theory of Planned Behaviour provides a well-established explanation for the formation of behavioral intention and actual Behaviour [

46], and has been extensively applied across domains such as health behaviour, tourism, environmental protection, education, and consumer behaviour. Unlike Self-Determination Theory, the Theory of Planned Behaviour is a static model and pays limited attention to the dynamic and complex nature of behavioral decision-making. Moreover, the Theory of Planned Behaviour does not clearly account for the origin of behavioral antecedents [

47].

Recent research suggests combining Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour to better understand both the quality of motivation and the processes that turn motivation into intention and action [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. In the health sector, a meta-analysis of 36 empirical studies systematically examined the relationships between Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour constructs; the results support the complementarity of these two frameworks and highlight that their integration offers greater explanatory power for motivation, intention, and health behaviour [

47]. Additionally, the I-Change meta-theory proposed by De Vries et al. outlines, at a broad level, the motivation–intention–behaviour sequence and distinguishes different stages of intention [

48]. Building on these theories, this study operationalizes SDT-based visit motivation into three types and, within the Theory of Planned Behaviour, presents a testable model of “motivation→behavioral intention→subjective well-being”, thus extending explanations that typically conclude at behaviour to include psychological outcomes and well-being. By combining these perspectives, we develop a more comprehensive and complementary analytical framework and test it within the context of urban forest parks. This study aims to apply this integrated socio-psychological model to the setting of urban forest parks, seeking to overcome the limitations of single-theory approaches in explaining visit motivations and emotional responses.

This study aims to examine how different types of visit motivations in the context of urban forest parks influence behavioral intention and subjective well-being, and to explore the mediating role of behavioral intention in this process. Using recreational visitors to urban forest parks in Fuzhou as a case study, we empirically test the pathways linking visit motivations to urban forest park usage decisions and subjective well-being. This research seeks to determine whether activating or strengthening different types of urban forest park visit motivations produces differential effects on well-being outcomes. The findings may provide practical implications for encouraging public engagement with urban forest parks and promoting greater psychological benefits through urban nature contact.

6. Conclusions

This study reveals the differentiated pathways through which various types of motivation influence subjective well-being via behavioral intention. The results show that intrinsic motivation significantly and positively affects behavioral intention, whereas extrinsic motivation and amotivation have significant adverse effects. Behavioral intention, in turn, strongly predicts subjective well-being. Amotivation demonstrates a dual effect: it negatively influences subjective well-being through partial mediation but also exerts a direct positive influence. The results confirm the mediating role of behavioral intention, showing that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations enhance well-being only through complete mediation. These findings contribute to the integration of Self-Determination Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour, providing empirical evidence for understanding how motivation and intention interact to shape the psychological benefits of urban forest park visitation.

The findings hold significant practical value for policymakers, planners, and managers. First, strategies should focus on supporting the internalization of extrinsic motivation. Framing park visitation as a positive social norm and encouraging participatory governance, volunteer engagement, and environmental education can shift externally driven motives (“I have to go”) toward autonomous engagement (“I want to go”), ensuring more sustainable park use. Second, the positive direct effect of amotivation suggests that natural environments have inherent restorative properties. Park design should therefore emphasize restorative features—such as quiet rest areas, flowing water features, diverse vegetation, and suitable lighting—to trigger unconscious relaxation and psychological restoration. Promotional strategies could highlight effortless relaxation and the natural healing capacity of parks, targeting amotivated individuals with messages such as “Relax, Even Without a Plan.” Accessibility and convenience should also be prioritized, lowering barriers to entry and making urban forest parks a natural part of daily life.

Building on the study’s limitations, future research should broaden the cultural scope of samples to test the applicability of the framework across diverse contexts. Additional mediators and moderators, such as emotional responses, environmental perception, and social support, should be incorporated to explain better the pathways linking motivation, intention, and well-being. Combining self-reported data with objective behavioral measures (e.g., GPS tracking, physiological indicators, or time-use diaries) would enhance the robustness of findings. Moreover, refining motivation measurement tools is essential to reduce conceptual overlap between extrinsic and intrinsic items and to capture nuanced motivational profiles more accurately. Advancing these directions will provide stronger evidence on how different types of motivation shape behavioral intentions and well-being outcomes in urban forest park settings.