Abstract

This study explores the interplay between environmental justice and energy democracy in the context of forest-based energy conflicts in Türkiye, focusing on the case of the Akbelen Forest. It draws on qualitative data from community-based actions and legal documents to examine how local communities engage in collective action against extractivist energy policies that threaten their ecological and social environments. The findings reveal a complex web of multilayered injustices, including procedural, distributional, and recognitional dimensions, experienced by the affected populations. In this regard, the Akbelen case demonstrates how these different dimensions intersect and constitute a framework of “multiple justice”. The central argument of this study, developed primarily through our visualised network graph, is that the Akbelen case demonstrates the limitations of current environmental governance frameworks in accommodating community-based ecological values and rights. This analysis demonstrates how energy democracy can function as both a normative and strategic instrument for rethinking participatory planning and forest governance. The present paper contributes to ongoing debates in the fields of political ecology and environmental governance by situating grassroots mobilisation within a broader discussion of just energy transitions. The study also emphasises the necessity of inclusive, multi-actor governance models that prioritise democratic participation, ecological integrity, and intergenerational equity.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on the nexus between environmental justice and energy policy, particularly in the context of extractive activities in ecologically sensitive areas. Forest-based energy conflicts have emerged as pivotal arenas where contestations over land use, democratic participation, and environmental values unfold. As of 2024, fossil fuels still account for more than 80% of the global primary energy supply, with coal alone generating 37% of global electricity—underscoring the continued centrality of fossil-based systems despite transition efforts [1]. These conflicts frequently involve profoundly inequitable power dynamics between state authorities, private enterprises, and local communities, resulting in what scholars have termed “multi-dimensional environmental injustices” [2,3].

Türkiye has also been affected by this trend. In the aftermath of the global economic crisis of 2008, privatisation policies have been implemented across the world, including in Türkiye. In Türkiye, privatisation—particularly within the energy sector—has emerged as a pivotal mechanism for capital accumulation. The enclosure of communal spaces accelerated in the early 2000s, coinciding with the commencement of private and state investments in the energy sector. This acceleration can be attributed to the aforementioned privatisation process [4].

In this sense, the case of Akbelen, which includes forested areas and olive groves, is a prominent example of the process of enclosure of the commons in Türkiye, both in terms of its public visibility and the level of social reaction [5,6,7]. From an academic perspective, Akbelen exhibits several salient features that render it the primary subject of this study. Firstly, the Akbelen Forest has become a prominent site of community-based actions against extractive energy policies, particularly coal mining expansion projects that threaten both ecological integrity and local livelihoods.

Secondly, although no tangible or symbolic spatial gain—meaning a collectively achieved preservation, reclamation, or reconfiguration of space and its uses—was realised in the Akbelen case (i.e., grassroots mobilisations and legal processes did not prevent the transformation of the area’s existing character), this example is noteworthy due to the continuity of community-based actions, the decisive role of local actors, and strong inter-scale organising networks (for debates on conceptualisations comparable to what we term “spatial gain”, see [8,9,10,11,12]). This social reaction, which emerged in a small-scale rural settlement such as İkizköy, where the Akbelen Forest is located, did not remain confined to the local level but also garnered international recognition when one of the pioneering figures was elected as muhtar (village headperson) in 2024 and was later included in the BBC’s list of ‘100 women creating impact in the world’ [13].

Thirdly, the Akbelen case constitutes a significant example of the forms of community-based actions adopted by grassroots mobilisations against the destruction caused by energy production. The allocation of forested areas and olive groves, which are commons, for coal mining activities is not only a spatial loss, but also an example of the top-down rescaling strategies that cause this loss to occur and institutionalise this loss as official policy. Despite the fact that the mining activity is undertaken by the private sector, the commons are being reorganised by the state through spatial allocation, permit processes, and legal mechanisms. As an alternative to the top-down rescaling process, a multi-actor bottom-up form of rescaling has been developed in Akbelen. This extends to local, regional, national, and global scales. It is evident that local communities, non-governmental organisations of various scales, professional chambers, experts, activists, and international environmental organisations have collectively established a robust social mobilisation by establishing an alternative scaling network.

However, despite the aforementioned community-based actions, which resonated internationally, and the form of scaling that developed from the bottom up, a spatial gain could not be achieved in the case of Akbelen. Indeed, almost all of the Akbelen Forest and other villages in the vicinity of this forest have been destroyed. The central issue addressed in this study therefore concerns the underlying factors that have impeded the attainment of spatial gain in Akbelen, despite the presence of a robust scaling network and social mobilisation.

The last factor that underscores the significance of this study is that, although earlier studies have documented analogous conflicts in Latin America and Southeast Asia, there remains a paucity of research examining how discourses on energy democracy emerge from grassroots mobilisations in Türkiye’s forest regions. For instance, some Indigenous communities in Ecuador and Colombia have experienced similar forms of resource-led displacement and ecosystem loss [14]. On the other hand, the Waorani case as a court victory in Ecuador illustrates the extent to which legal initiatives can protect and ensure recognition of ancestral land rights of local residents [15]. Similarly, some prominent grassroots mobilisations in Brazil’s wind and solar corridors also underscore how energy democracy initiatives can arise as forms of collective action against extractivist energy policies [16]. Comparable examples from Southeast Asia have also emerged as eco-social mobilisations, particularly Indigenous blockades in Sarawak, which exemplify how local residents have challenged deforestation and logging pressures on customary land in Malaysia [17].

Analogous to instances observed in Ecuador, Colombia, and Southeast Asia, Akbelen exemplifies a grassroots organising that has emerged through the initiatives of local communities, leading to the involvement of multi-level actors, and yet resulting in spatial losses despite the implementation of social and legal initiatives. In this particular context, Akbelen represents a distinctive case in Türkiye, where the notions of energy democracy and multiple injustices are discussed in parallel. However, the concept of spatial gain has not yet been realised. In this context, as outlined in the preceding section, this study not only identifies the challenges of effective participation and governance, but also discusses the transformative potential of energy democracy in addressing the multiple injustices categorised in this study.

On the basis of the reasons outlined above, the interplay between environmental justice claims and forest governance structures remains underexplored in the Turkish context. This study therefore addresses these gaps by analysing the Akbelen case through the lenses of energy democracy and environmental justice. The following research questions guide the analysis: Firstly, how do local communities conceptualise their community-based actions in response to forest-based energy projects? Secondly, what forms of participatory governance do they envision in response to extractivist interventions? Drawing upon a comprehensive set of qualitative data, encompassing interviews, observational studies, and document analysis, this study undertakes a systematic examination of procedural, distributional, and recognitional dimensions of injustice experienced by communities engaged in the Akbelen social mobilisation.

More broadly, this study argues that the Akbelen case reveals the limitations of conventional forest and energy governance frameworks in recognising and addressing community-based environmental values. By situating local community actions within the broader discourse of just energy transition, we argue that energy democracy provides a valuable normative and analytical lens for rethinking forest governance and participatory planning. This contribution is further strengthened by (i) integrating theoretical discussions on multi-level governance and rescaling into the Akbelen case, framing it as a form of commoning practice, and (ii) employing a methodological approach that goes beyond in-depth interviews and discourse analysis, by visualising a network graph mapping the types and qualities of relationships among all involved actors, thereby identifying governance gaps.

In this regard, the article is structured in four parts, excluding the introduction and conclusion. The first section examines the existing scholarly literature concerning energy democracy, multi-dimensional injustices, and energy policies in Türkiye. The second part outlines the materials and methods employed. The third part presents the results, while the fourth part discusses the findings of the research in relation to broader scholarly, theoretical, and practical debates.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

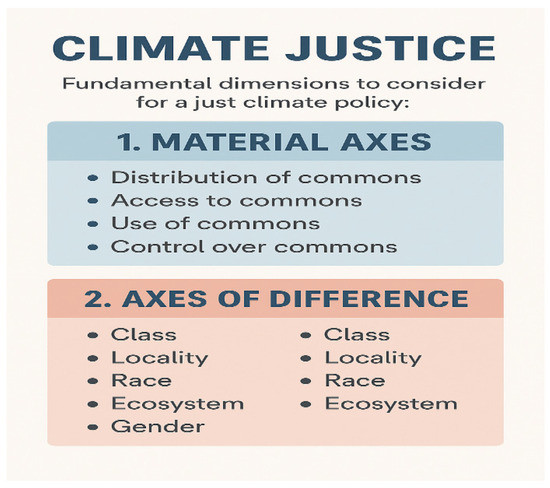

The concept of justice, although most often associated with social and economic dimensions, must also be examined through geographic, historical, institutional, and cultural perspectives. In the contemporary era, demands for justice are on the rise in a variety of domains, including, but not limited to, race, gender, climate, energy, and space. This demonstrates that these justice demands are intricately intertwined [18,19,20,21]. The interconnection of these demands forms the basis of a conceptual framework that is frequently referred to as “multiple justice” [22] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Axes of climate justice (created by the authors).

This overarching framework encompasses a range of issues related to space, environment, and energy. In this study, the concept of “multiple justice” is mainly operationalised through the simultaneous analysis of distributional (who bears the costs and who benefits), procedural (who is involved in decision-making processes), and recognitional (whose identities and values are acknowledged) dimensions. These overlapping layers are particularly evident in the Akbelen case, where the convergence of unequal distribution of ecological burdens, procedural exclusion from governance and decision-making mechanisms, and marginalisation of local identities is observed. In our framework, energy democracy is employed as a normative and strategic lens that brings the aforementioned justice claims, governance challenges, and struggles over the commons into a shared analytical ground.

In the contemporary context, the spatial dimensions of environmental justice have become increasingly apparent, particularly in the context of conflicts arising in sectors such as energy and mining. Theoretical discussions in this area are deepened by the examination of spaces both as physical entities and as structures that generate justice or injustice [23,24]. In this regard, the theory of the commons provides a seminal framework for the pursuit of justice. This theoretical framework situates collective resource management, community-based participation, and subjectification in decision-making processes at the core of its analytical paradigm [25,26].

The primary advantage of interpreting the commons in this manner is that they are not restricted solely to the sharing of property or natural resources. Rather, this approach highlights the connection between these elements and the social reproduction of communities, as well as the collective decision-making capacity that exerts a significant influence on spatial existence [26].

From a historical perspective, the enclosure practices that led to the loss of the commons are being reproduced in the present day, particularly through energy and mining investments.

The legitimisation of such forms of enclosure is achieved through various means, including the delimitation of physical space, the privatisation of property, the centralisation of decision-making mechanisms, and the restriction of democratic participation. Multi-scalar governance models, implemented as an alternative solution to this process, focus on resource use and the social production of scale itself [27]. Taken together, discussions on commons and scale shed light on how struggles over space are inherently struggles for justice; they bring together the distributional, procedural, and recognitional dimensions under the much broader horizon of energy democracy.

Consequently, grassroots mobilisations seeking to reclaim the commons should not be regarded solely as ecological demands. These initiatives are also powerful political movements with the potential to transform governance. This is precisely where energy democracy, environmental justice, and multi-level governance intersect: grassroots mobilisations both challenge extractivist energy regimes and policies and reveal justice deficits and generate demands for more inclusive governance models that potentially cut across local, national, and global levels. De Angelis [28] argues that such alternatives emerge from commons, mobilisations, and spatial gains and emphasises that these mobilisations are of paramount importance for both social transformation and inter-scalar interactions.

A salient characteristic of these mobilisations is their capacity to articulate multiple and diverse demands for justice through their relationships with actors operating at different levels. These types of community-based actions and grassroots mobilisations, which often emerge at the local level, are rescaled over time through networks they establish with national, regional, and sometimes global actors. In this context, scale is not a fixed or measurable concept, but rather one that is continuously produced and reshaped through institutions, forms of knowledge, governance structures, and networks (see [29,30,31]).

In this manner, these multifaceted groups generate discourses on alternative forms of governance that advocate for energy democracy [32,33]. In this context, scale must be considered more than simply an analytical instrument. This phenomenon has been theorised as a structure that is produced and transformed within the context of social relations. A prime example of this phenomenon is the Lumad community in the Philippines. In this particular instance, the group developed a model of “community-based land governance” aimed at counteracting mining activities. This model not only redefined the physical space of the community but also reasserted their right to participate in decision-making processes [34]. This example underscores the ways in which community-based land governance can redefine participatory practices.

A comparable example can be found in Som Energia, a company based in Spain. In this particular instance, citizen-led energy cooperatives have advanced a paradigm of energy democracy, premised on the collective management of energy as commons [35]. This case illustrates how energy democracy can be anchored in cooperative structures.

The examples under consideration generally repudiate the environmental costs imposed on rural areas by demands originating from urban centres. This process, termed “planetary urbanisation” by Brenner and Schmid [27], involves the conversion of rural regions into production areas to satisfy urban demand. This phenomenon gives rise to novel spatial contradictions, thus necessitating the establishment of new shared governance regimes designed to address them. This theoretical approach, conceptualised as planetary urbanisation, highlights the structural contradictions emerging at the rural–urban nexus.

These worldwide discussions on environmental justice and energy democracy also resonate strongly in Türkiye. In the Turkish case, we observe that rural communities are exposed to similar dynamics of enclosure and dispossession, yet within a governance regime and structure designed primarily by the typical features of centralisation and state-driven energy regimes.

The presented examples illustrate that energy production and consumption are not merely technical and economic matters. These elements are of paramount importance, raising deeply political and ethical questions. As evidenced by the Akbelen example, such mobilisations and organisations at the grassroots level can be considered both a form of “revolt” and attempts to build alternative ways of life and governance. Taken together, these discussions and examples illustrate how multiple justice, the commons, and multi-scalar governance interconnect to form the analytical perspective applied in the Akbelen case.

Within this framework, in cases where there is inequitable distribution of energy policies, climate justice serves as a crucial analytical lens. This approach facilitates a systematic comprehension of the environmental damages and the multiple injustices experienced by affected communities. Fraser [36] proposes a three-part concept of justice, namely recognition, redistribution, and representation, which can provide a fundamental framework for understanding such inequalities. Rancière [37], by contrast, posits that the essential nature of justice is not contingent upon its outcomes, but rather on the question of who becomes visible in politics. The following question is posed by this approach: to what extent are marginalised groups able to participate meaningfully in climate governance?

Research shows that the presence of the layers of governance—especially in regions most affected by climate change—can significantly influence how people perceive local development and fairness. A pertinent example of this phenomenon is Durban, a city in South Africa, which vividly illustrates these dynamics [38].

Energy justice is predicated upon principles of distribution, recognition, participation, and rights. As noted by Healy et al. [39] and Sovacool et al. [40], these principles are increasingly shaping the language and priorities of energy policy. In this case, the consideration of structural difficulties pertaining to the energy supply chain, from production to consumption, is the principal matter of the research. Such concerns frequently extend beyond national boundaries, requiring more integrated approaches to energy systems. It is evident that rural populations and marginalised groups are more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of energy infrastructures. Beyond local impacts, the aforementioned harms might potentially exacerbate the erosion of democratic participation, spatial coherence, and procedural justice.

The concept of energy democracy postulates that energy governance should be rooted in local, transparent, and less centralised models, in contrast to energy regimes that are predicated on fossil fuels, characterised by centralisation and hierarchical structures [41,42]. Whereas all these dynamics can be encountered in divergent global contexts—from the Philippines to Spain— they take on specific resonance in the Turkish context. At this point, we can place the intersection of energy democracy and debates on environmental justice within a governance structure that is characterised by the features of strong centralisation and recurrent patterns of rural dispossession. In Türkiye, cases such as Akbelen illustrate that rural areas have effectively been transformed into sacrifice zones to address the energy demands of urban areas [43]. In this sense, the fact that production is concentrated in rural areas while consumption is centred in urban areas gives rise to significant spatial and structural injustices [44]. This aptly indicates how worldwide debates on the issues of planetary urbanisation, the commons, and energy justice find adequate concrete expression in Türkiye, especially through conflicts over forest and land governance.

Since 1980, there has been an observable shift towards a market-based model in the governance of energy, replacing the previously dominant state-centred approach [4]. Community-based mobilisations against energy and mining projects have proliferated across Türkiye in recent years. These mobilisations commenced with opposition to hydroelectric dams and have evolved into more widespread challenges to thermal and coal-powered plants. It is evident that these mobilisations, despite their frequent localisation, constitute an integral component of a more extensive socio-ecological landscape of contestation and have contributed to the emergence of novel political subjectivities within the domain of environmental governance.

In sum, the theoretical framework provided in this study demonstrates how energy democracy operates as both a normative and analytical bridge that links debates on multiple justice, commons, and governance to concrete cases, such as Akbelen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Area: The Akbelen Forest

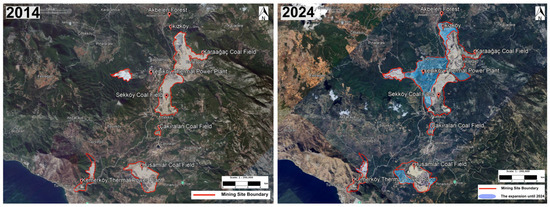

This study focuses on the Akbelen Forest, which is located within the boundaries of İkizköy in the Milas district of Muğla Province, Türkiye (see Figure 2). The geographic coordinates of the Akbelen Forest study area are approximately 37.1991° latitude and 27.5878° longitude.

Figure 2.

The spatial expansion of lignite fields around Akbelen and İkizköy (delineated by the authors utilising Google Earth, version 7.3; Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA, data from 2014 to 2024).

Figure 2 depicts the spatial expansion of coal mining areas, using Google Earth imagery from 2014 to 2024. Red borders denote existing mining licence areas, while blue tones represent new mining areas that have emerged over the past decade [45]. The aforementioned expansion has had a direct impact on settlements such as Akbelen Forest, İkizköy, and Sekköy, prompting significant debates regarding energy production processes, environmental justice, and forest governance.

Since the 1980s, the region has been subject to intensive coal mining operations to supply the Yeniköy and Kemerköy thermal power plants. A total area of 55,000 hectares has been classified as severely degraded, with approximately 50% consisting of forested areas and the remainder comprising fertile agricultural lands and olive groves.

The coal concession area encompasses a total of 60 villages and neighbourhoods. To date, 8 villages have been completely eradicated, 4 have been significantly damaged, and 37 remain under existential threat.

Laws No. 4628 and 6446 have had a considerable impact on the role of the private sector in energy planning, significantly increasing its influence (see Table 1). Nevertheless, this radical transition has generated profound discord between development objectives and environmental sustainability. As Gümüşel and Gündüzyeli [46] accurately observe, policies prioritising energy security are perceived by local actors as representing ecological surrender and exclusion from democratic decision-making processes at the grassroots level.

Table 1.

Changes in Türkiye’s energy laws over the years (created by the authors based on publicly available sources [47,48]).

The Akbelen Forest became the site of significant contention over energy policy following the designation of the area for open-pit coal mining in 2018. This decision led to substantial deforestation and the displacement of local communities. The area was allocated to the Yeniköy-Kemerköy Electricity Production Company through a privatisation tender, and mining activities expanded under Article 16 of Türkiye’s Forest Law (Law No. 6831).

It is therefore pertinent to briefly examine the amendment added to the Mining Law No. 3213 in July 2025. The introduction of this regulation resulted in the inclusion of a new definition of “strategic/critical mine” within the legislation, accompanied by the provisional incorporation of Article 45 into Mining Law No. 3213. Concurrently, Article 11 of the Law underwent amendments, transferring expropriation powers for these mines to the relevant ministries. In the EIA (ÇED) process, the institutional comments were limited to 90 days, and applications were deemed approved if no response was provided within this period.

It is anticipated that mining permits will be issued at no cost in state forests and that these permits will be executed by the General Directorate of Mining and Petroleum Affairs (MAPEG); permission to operate in olive groves has been granted on the condition that the trees are relocated. Moreover, the amendment in question pertains to the designation of specific areas encompassing olive groves near the Yatağan, Yeniköy, and Kemerköy thermal power plants, which were subsequently rendered accessible for mining activities. This determination was effectuated through the delineation of their respective coordinates [49].

The new bill introduces provisions for the exploration and extraction of mineral resources in areas designated for olive groves, forests, and pastures. It is observed that this bill has the potential to impinge upon the public participation process and institutional oversight, a phenomenon that can be attributed to the limitations imposed on the environmental and social impact assessment process. The potential consequences could lead to dispossession and an increased risk of displacement of rural communities. The relocation of olive trees to other areas demonstrates a lack of consideration for the integrity of the ecosystem. The Law on Olive Groves has also been identified as creating a legal loophole that could be exploited with this new proposal.

These amendments/new regulations create serious socio-ecological risks and are crucial for contextualising the Akbelen case, as discussed in the following sections. In response, local residents, civil society actors, and environmental groups initiated an ongoing social mobilisation, including legal challenges and a continuous vigil to protect the forest.

2.2. Research Design and Methodology

The present study adopted a qualitative research design, with fieldwork primarily conducted between 22 and 27 May 2024 in İkizköy and the city centre of Muğla. However, it is important to note that some interviews—such as the one with TEMA on 10 May 2024—took place a little earlier, while others were extended over time due to delayed responses, despite repeated follow-ups. The most recent interview was conducted with 350.org on 21 July 2025.

The data presented herein were collected through semi-structured, in-depth interviews with local stakeholders engaged in mobilisations opposing the expansion of coal mining in the Akbelen Forest. Prior to data collection, ethical approval for the study was obtained. Participants were identified and selected through a two-stage sampling strategy: Firstly, in order to identify the actors involved in the mobilisation in Akbelen, a preliminary media scan was conducted for the period from 2000 onwards, in parallel with the period during which energy privatisations took place in Turkey. We scanned the digital archives of some prominent newspapers reflecting different political inclinations, including liberal, conservative, and leftist perspectives. We employed keywords such as “protest, social mobilisation, urban mobilisations, environmental action” and other associated concepts, including “community-based actions, demonstration, activism”.

Secondly, based on scan results, participants were selected using non-probability sampling (see [50]). Within the framework of this sampling technique, actors were categorised by scale (sub-local, local, national, global) and type (local residents, NGO representatives, municipal officials, national/international organisations) using purposive sampling. Participants were then identified and interviewed using a snowball sampling method to reach less visible actors and obtain key information: Only those who were willing, reachable, and responsive were interviewed. In-depth interviews were conducted with 32 actors, of which almost 9 per cent were conducted with global actors, 25 per cent with national actors, and 65 per cent with local actors.

Following this process, a table was prepared indicating the actors actively involved at different scales (global, national, local). The following Table 2 displays a list of these actors who were interviewed, along with those who were categorised as unfit for participation for some reasons, as explained below.

Table 2.

The number of actors providing support to the Akbelen mobilisation, as well as the number of those who were interviewed at length (created by authors).

Fieldwork was completed when responses began to converge and no new themes emerged, indicating that data saturation had been reached [51]. Interviews with local residents and institutional actors were conducted in a variety of settings—including private homes, NGO offices, and open-air forest vigil sites—according to accessibility and participant preference. Actors who either rejected interview requests or could not be reached despite numerous efforts are indicated in Table 2 as “0”. It should be underlined that interviews with state institutions were not conducted, as the official state actors did not make a direct or positive contribution to the process in terms of the aforementioned spatial gain. However, the role of the state—whether positive or negative—was critically scrutinised through legal and institutional documents as secondary data.

The interviews were audio-recorded with participants’ consent and analysed through thematic coding. Thematic coding was applied to all these interviews, and the coding process was conducted in three stages: (i) open coding was performed to capture recurring ideas; (ii) axial coding was performed to group codes under the broader categories of spatial, procedural, and recognitional justice, and governance gap; and (iii) selective coding was performed to refine the main themes. The coding process was conducted manually using MS Excel and MS Word. The rationale behind this choice was to circumvent the potential pitfalls of superficiality, particularly in light of the discourse analysis employed in the study. This approach was undertaken to enhance the analytical process with qualities such as transparency, depth, and rigour. Following the conclusion of previous processes, efforts were made to ensure that the resultant themes reflected not only the empirical data but also the framework of environmental justice and energy democracy.

The interview questions focused on the perceived environmental and social impacts of mining, the legal and institutional dimensions of land expropriation, and the ways in which justice, displacement, and participation were experienced by different actors. The analysis placed emphasis on procedural and spatial justice, as well as the role of community agency in responding to extractivist policies. In order to achieve this objective, the initial phase of the research involved the application of a critical realist perspective [52] to the interpretation of the participants’ narratives. This entailed the utilisation of an interpretive and discourse analysis approach [53], a method that facilitates the identification of underlying power dynamics and socio-spatial structures that exert a significant influence on the participants’ lived experiences. In addition to thematic and discourse analysis, a network graph was created using in-depth interviews and secondary data. The purpose of this was to map the relations between actors over time and to identify the governance gap. The latter was undertaken in order to explain the failure in spatial gain.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Enclosure and Community Gains

The expansion of the mining concession into Akbelen Forest has intensified spatial enclosure, manifesting in the fragmentation and restriction of local access to forests, olive groves, and agricultural lands. An analysis of interview data indicates that residents view this process not only as environmental degradation but also as the systematic disruption of their everyday spatial practices. As L6-1 from İkizköy noted, “We are no longer able to traverse the lands where we previously harvested olives or collected firewood.” Such statements emphasise the loss of mobility and traditional land-use rights caused by deforestation and fencing. L5-1, who traces the origins of enclosures in this region back to the energy sector privatisations of the 1980s in Türkiye, states the following:

“When the first [power plant] was to be established in Kemerköy, they didn’t want it there (…). He sees the fruits drying up. He sees the villagers being displaced, he experiences it, and he says, “We don’t want this.” [In 1980s] (…), it was the first place where they said, “we don’t want this, don’t let it be built.” They suppressed them by saying, “roads will come, civilisation will come, water will come here, don’t you want your villages to develop?” (…) I don’t know if they kept watch there or anything, but the women really put up a strong response, but unfortunately, they did what they had planned. The villagers, after that, almost the entire Milas, surrendered from the beginning, saying, “You can’t stand against them; they get what they want.” (…) “What happened, they responded to, but it was done anyway” kind of hopelessness [has emerged].”

Yet, these losses have simultaneously engendered what can be termed “spatial gain”, as defined earlier—new forms of territorial consciousness and collective ownership of space. Participants emphasised the symbolic and strategic value of the forest occupation (vigil area), describing it as “a commoning practice” and “a living space emerging from a grassroots mobilisation process”. L6-9, who describes the space where commoning practices are continuously generated and reproduced, uses the following expressions for the vigil area:

“Look, here we all work in the fields, take care of our animals, and graze them. We never have a day off. Life is like this in the village. But every evening, even if it’s just for 5 min, we come here to our café [referring to the vigil area]. We read the articles of the Constitution. We are reading the articles of the law. Our friend here has been on duty in the tent for 2 years. We are not leaving him alone. We will never give up our actions.”

As demonstrated by the aforementioned statements, it can be deduced that Akbelen is not a state-defined space. Instead, it has evolved into a site of community-based actions, where demands for equality, liberty, and justice are made concretely, novel collective subjectivities are formed, and, in Balibar’s terms [54], “egaliberty” is realised.

These emerging geographies of community-based actions have redefined the relationship between local residents and the forest, transforming it from a site of extraction into a space of political subjectivity and ecological care. In this sense, spatial enclosure has paradoxically triggered a process of spatial empowerment.

3.2. Participation, Actors, and Governance Gaps

The interviews reveal a marked dissonance between official governance frameworks and the participatory aspirations of local actors. The participants repeatedly emphasised the absence of meaningful consultation and the procedural injustices embedded within the decision-making processes concerning mining expansion. Whilst the company and government agencies claim to have obtained legal authorisation, local residents and civil society groups have characterised the process as opaque, top-down, and exclusionary. L6-2’s statements regarding the process are as follows:

“After the disappearance of Işıkdere, immediately after the 2019 local elections, the company sends a notice to [the residents of] Ova Mevkii, Karacahisar, Karadam, and Akbelen (…), which [it had previously said] it would not buy, and says, “We will buy these places too, sell them to us” (…). In the notice, it says, “Come to the company on this date and at this time.” He is calling them to his feet. They are already exempt from the EIA (ÇED). And they also say, “Are you going to sell it, or should we expropriate it?” Because they have permits, they have licenses. If they don’t do it, the state will be able to do it.”

A wide range of actors have emerged as part of the solidarity network, including environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs), professional chambers (e.g., the Chambers of Agriculture and Electrical Engineers), and local municipal representatives. It is noteworthy that local residents and activists in particular have played a pivotal role in organising and maintaining the forest vigil, positioning themselves not merely as victims of dispossession but also as proactive agents of ecological defence.

Explaining the legal basis of these mobilisations carried out by various actors across multiple levels and scales, L7-2 uses the following expressions:

“We, the people of İkizköy, are determined to defend our right to live in a healthy environment, as granted by the constitution, to the fullest. I am reading Article 56 of our Constitution. Everyone has the right to live in a healthy and balanced environment. Our right to life cannot be seized. This homeland is ours. Who are we? We are patriots who take care of our land, air, trees, (…) water, and nature (…).”

The groups that are directly affected by the environmental policies employ a variety of strategies, including legal action, media campaigning, and direct action, with the aim of addressing and eliminating multi-dimensional injustices.

Nevertheless, these disparate endeavours have been only partially effective, largely due to the absence of functional and operational channels for democratic participation. The exclusion of a particular segment of local actors from democratic decision-making processes is indicative of the structural fragility inherent in environmental governance in Türkiye. While a modicum of participation remains a theoretical possibility, the aforementioned processes are, in practice, confined to less effective reactive protests. In legal proceedings or by the central administration, a discourse based on the principle of “public interest” is generally employed to justify the situation. It has been asserted that this discourse results in the marginal presentation and perception of social reactions. To illustrate this point, an account from the awareness-raising meetings in the region regarding “public interest”, as recounted by L6-2, is as follows:

“One of the volunteer lawyers came and talked about the process in Efemçukuru. He said, “They will talk to you about the public interest.” He said, “The same thing was done there too.” One of our uncles from the village asked the following question: “Mr. Lawyer, I don’t understand, who are these people referred to as the public here?” Well, if these are public, what about us, aren’t we considered public too?”

The conflict referenced above pertaining to the definition and substance of the concept of “public” can be interpreted as a hegemonic narrative embedded within official discourse, which aims to render the conflict invisible, as expressed by Laclau and Mouffe [55]. If this discourse is accepted in its current form, it has the potential to result in the exclusion of the residents of Akbelen from processes that will have an impact on their living spaces. Furthermore, as Fraser [56] asserts, this may directly precipitate a crisis in the public sphere. Whilst the prevailing centralised legal frameworks continue to restrict local participation and spatial justice in forest and energy governance, a recent ruling by Turkish legal authorities may signal a potential change in the prevailing state of affairs. The Council of State’s 4th Chamber recently overturned the local court’s decision exempting Akbelen from the requirement of a ÇED/EIA for the project. Consequently, a new expert site inspection was ordered on the grounds of inadequate scrutiny [57]. This decision has the capacity to initiate the establishment of procedural justice and institutional accountability in extractive contexts.

At this juncture, N4-2 and L5-1 underscore the imperative to broaden the scope and expand the scale of the public domain, as delineated below, respectively:

“In Türkiye, the planning system is obliged to secure environmental protection areas and rural living spaces in higher-scale plans. Additionally, the destruction of local residents’ living spaces for energy production is unacceptable from a planning ethics perspective. Because the fundamental principle of planning is to ensure the balanced distribution of social benefits and to define public good based on spatial justice. However, what is at stake here is the elimination of a village, a forest, and communal living for energy production by a private company under the guise of public benefit.”

“We have now seen this: Politics alone is not enough here. Institutions alone are not enough; civil society organisations and associations alone are not enough. And the villagers alone are not enough. They all need to be part of a whole. There is a tripod here. Look, it always forms three and stands, it stands balanced. No, this mobilisation should be like that too. It needs to include the members of parliament as well. It needs to be included in the press aspect. The local must already necessarily be included.”

The findings of this study demonstrate that environmental injustices are intricately intertwined at both spatial and procedural levels in the Akbelen case. Evidently, the process of coal mining instigates expropriation processes, which threaten not only the natural environment, but also the livelihoods of the local population. Akbelen, conversely, serves as a prominent example of a grassroots organising, demonstrating the capacity for the formulation of alternative governance demands that are antithetical to the aforementioned injustices. This finding suggests that current governance models are inadequate in effectively addressing social needs. The root cause of this insufficiency is attributable to the presence of multiple actors and conflicting approaches and policies. These findings will now be addressed in the following sections by relating them to the existent scholarly literature.

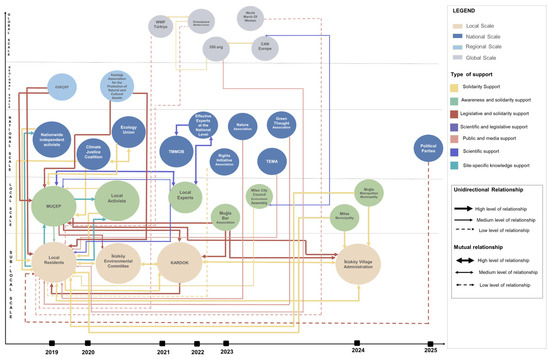

These limitations pave the way for the analysis of actor relationships and governance gaps, as illustrated in Figure 3. As shown in Figure 3, the positions of the actors engaged in spatial mobilisation in Akbelen Forest are represented at various governance scales, including sub-local, local, national, regional, and global levels. The figure also demonstrates the relationships that have developed between these actors over time, as well as the types and intensities of these relationships. The diagram illustrates the multi-scalar participation of actors in Akbelen, while also revealing gaps in the governance structure and discontinuities in vertical linkages.

Figure 3.

The network graph indicating the scaling patterns of the actors in the Akbelen case (created by the authors).

The diagram under scrutiny here demonstrates the existence of strong relationships predicated on the basis of mutual information exchange between sub-local and local actors. The İkizköy Çevre Komitesi (İkizköy Environmental Committee), local residents, local activists, the İkizköy muhtarlık (the village administration, which changed after the 2024 local elections), the Karadam-Karacahisar Nature and Solidarity Association (KARDOK), and the Muğla Environmental Platform (MUÇEP) demonstrate a strong grassroots network structure, organised through high-level solidarity and information sharing.

The types of support represented by the colours in the legend include solidarity-based relationships, awareness-raising activities, media and visibility support for publicising the mobilisations, support for expertise-based technical knowledge and legal consultancy, the sharing of regional scientific knowledge, and the transmission of place-specific tacit knowledge. The existence of these various forms of support is indicative of the multifaceted circulation of information and interaction that characterises governance processes. Furthermore, these data highlight the presence of knowledge gaps and deficiencies in participation that become apparent across diverse spatial scales.

National and global actors appear to have predominantly pursued campaigns, relying on public opinion, media, and expertise, and have been insufficient in establishing direct and sustained relationships with local institutions. With the expansion and increased visibility of the protests in 2023, the involvement of global actors such as Greenpeace, 350.org, and the World March of Women marked a significant turning point in the intersection of local mobilisations with international environmental justice discourses. However, these relationships are often indirect, mediated through umbrella organisations such as MUÇEP, and direct ties with local communities based on information exchange remain limited.

The changes in the administrations of the Muğla Metropolitan Municipality and Milas Municipality following the 2024 local elections, coupled with the appointment of one of Akbelen’s most prominent figures as muhtar (village headperson), resulted in significant institutional support for the Akbelen mobilisation. The substantial and efficacious assistance furnished by these emergent actors to the process proved to be of paramount importance, not solely in the legal domain, but also in the translation of local imperatives into governance mechanisms through infrastructural contributions. Nevertheless, this impact was also constrained by two factors that significantly restricted local governments’ capacity for intervention: the centralised administrative structure of Türkiye, in conjunction with the concentration of administrative authority—particularly in relation to forestry areas—within the central administration. Consequently, while the post-election changes in local government provided technical and legal support for the Akbelen process, this support was constrained by the limitations of authority in decision-making processes.

As shown in Figure 3 and as interviewee N1 asserts:

“Local governments are unable to engage in the process. This is due to the fact that the process is overseen directly by the ministry. It is imperative to recognise that local government is bound by the constraints of its authority. Nevertheless, they were offering support, albeit limited. We issued an open letter to the central government, inviting dialogue, but regrettably, we received no response”.

This situation, which the participant also clearly indicated, is a clear indicator of a governance gap: The prevailing centralised institutional structure engenders a symbolic participation of local actors, thereby impeding their involvement in decision-making processes.

The frequently unidirectional and constrained relationships cultivated by actors at the national, regional, and global levels with the local level create a governance deficit. For instance, a notable disparity exists in the nature of relationships cultivated by actors such as TEMA, the Nature Association, and the Green Thought Association. These entities predominantly engage in one-way relationships with MUÇEP or local residents, while exhibiting minimal or no engagement with other organisations. It appears that global actors (for example, Greenpeace Akdeniz, 350.org, and Can Europe) mostly maintain indirect relationships with national or local actors such as MUÇEP, thereby failing to establish robust direct ties with local people or solidarity network organisations. Consequently, the political visibility of local mobilisations has remained limited at the global level, and local tacit knowledge is not integrated into institutional policies.

In sum, the diagram illustrating the Akbelen case demonstrates that horizontal organisational networks are robust; however, there are also evident gaps and discontinuities in vertical inter-scale relationships.

These findings actually indicate that grassroots actors have succeeded in establishing resilient horizontal networks. However, since fragmented vertical ties and limited structural openness continue to exist, a substantial governance gap persists, as will be discussed later in more detail in the discussion section.

4. Discussion

4.1. Reframing Spatial and Procedural Justice Through the Akbelen Case

This research demonstrates that the spatial enclosure in Akbelen entails not only environmental but also political consequences.

This finding aligns with Schlosberg’s [2] perspective of multi-level justice. According to Schlosberg, spatial injustice emerges in conjunction with procedural exclusion and lack of recognition. Schlosberg’s discussion of “multi-dimensional justice” is also based on Fraser’s tripartite concept of justice (redistribution, recognition, representation) [58]. In the Akbelen case, there has been a significant disparity and disconnection between concepts and issues such as “national interest” and “energy security”. These concepts are frequently invoked by official state/government officials and coincide with the marginalisation experienced by the local people. This profound tension therefore reveals how justice can be defined and experienced differently by different actors.

In this particular context, the extent to which the concepts analysed in the Akbelen case, namely “public interest” and “energy security”—which can be defined as superordinate concepts—contradict the life practices of local people on the ground. These concepts, which are frequently reiterated and prominent in the official state discourse, are often perceived and experienced in ambiguous and exclusionary ways from the perspective of people living on the ground. This conceptual disconnection is not confined to spatial enclosures; it also reveals multiple forms of injustice, such as procedural exclusion and recognitional injustice. The statements of L2 and N3, respectively, serve as concrete indicators of this experience of injustice.

“This is a complete energy injustice. There’s been an attempt to legitimise this injustice through the principle of public interest. However, if a need is being discussed, it’s a need that concerns the entire public. If you create a public good by destroying the right to life and living space of a segment of the public, you can’t hide the fact that the energy you produce is unfair from the outset. Moreover, if the mineral you mine for this energy is extremely low-quality coal, which will produce high carbon emissions, the injustice you’re inflicting on the ecosystem becomes apparent.

Our focus was on protecting and defending nature and life. And in doing so, we were all learning together. And indeed, that’s exactly what happened. Unless the energy issue is socialised, unless renewable energy systems that don’t harm nature are questioned, unless energy production processes are planned solely for need, not profit, and unless the opinions of the public and experts, which are the most important elements of this, are consulted, the problems energy production will create not only in Türkiye but worldwide remain the same: injustice and ecological destruction.

The Akbelen struggle represents a response to the disregard for the public in energy policies and also a significant practice in defending nature. Energy policies should be developed in accordance with the wishes of the people, not corporations.”

“Akbelen’s presence on the international agenda and its significant public outcry have increased the belief that fossil fuels should be questioned and that discussions about renewable energy can be framed within the context of the “nature-human” relationship. Energy is a necessity. But is the energy produced for domestic needs anyway? I doubt it. On the one hand, they’re producing energy, and on the other, it’s unfair. It’s ecologically unfair, and it’s unfair in terms of the villagers’ right to life.”

At this juncture, the collective mobilisation in Akbelen functioned both as a challenge to dominant frameworks and an exemplification of a common space wherein alternative social imaginations and common life practices were produced in tandem.

The vigil space created by the Akbelen case can be conceptualised as a form of “liminal commons” [59] wherein collective rituals give rise to alternative imaginaries and transitions [60]. In this sense, the vigil should not only be regarded as a symbolic presence. It is also a commons-based institution where new decision-making practices, rules of collective care, and forms of solidarity are both enacted and consolidated. Consequently, grassroots mobilisation in Akbelen signifies not merely the protection of land but also the reconfiguration of the terms of environmental citizenship. This symbolic transformation also yielded tangible outcomes. For instance, the vigil site turned into a platform where legal strategies were planned and coordinated, collaborations with national NGOs were fostered, and ecological practices, such as collective tree planting and seed preservation, were introduced. Through these actions, the symbolic living space was transformed into a site of both political mobilisation and ecological stewardship.

4.2. Grassroots Participation and the Limits of Official Discourse

The case study also illuminates the constraints imposed by participatory mechanisms within the environmental governance structure of Türkiye. Despite constitutional provisions and procedural formalities, meaningful involvement remains elusive. Fraser’s [36] argument posits that representation constitutes an indispensable component of justice, being as vital as recognition and redistribution. The absence of representation can result in a process of “misframing”. From this standpoint, Dryzek [61], for instance, discusses the systematic consequences of deliberative democracy and the absence of participation. In other words, the phenomenon under discussion leads to the exclusion of certain groups from political processes and the suppression of their voices. This inevitably and gravely harms both the scope and legitimacy of democratic participation. The response given by L6-4 regarding this is as follows:

“We know that there is such a thing as clean energy; it doesn’t [necessarily have to be] coal. But here they are taking our forest, our olive grove; without even asking us. We do not want to be displaced. These decisions should not be made at the top; the state should listen to us first. We are also citizens of this country, let us have a say too.”

These reactions exemplify not only a response towards exclusion but also the rise of solidarity, empathy, and novel democratic decision-making mechanisms informed by local environmental consciousness. As G1 states,

“(…) People from many different disciplines came and informed everyone involved with their expertise, from ecosystem knowledge to legal knowledge. Strong organising was undertaken. Discussions were held on how to make energy sustainable. Perhaps if this process had lasted a little longer, a broadly participatory report on energy democratisation and energy justice could have been produced.”

Comparable tendencies can also be observed at the global level. For instance, the renewable energy cooperatives in Spain [62] and the rise of local community-based actions against central energy systems in Japan [63] illustrate the empowerment of energy democracy internationally.

Figure 3, as examined above, points to the structural tensions debated in this section. Figure 3 illustrates that coordination among actors in the Akbelen case is largely fragmented. This provides insight into the governance gap that is located in the centre of challenges derived from grassroots participation. As illustrated in Figure 3, the directions of the previously analysed arrows and the irregular connections identified within this framework demonstrate this phenomenon. In the Akbelen example, there is a layered mobilisation, but within it, there is a clear lack of coordination—i.e., a governance gap. The multi-level actor structure in Akbelen, which developed over time through the solidarity and participation of actors at different levels, is not as coherent or harmonious as might be expected. In summary, the relationships that are clearly revealed by the ambiguous or disconnected arrows in the figure highlight a serious governance gap in two dimensions: namely, joint strategy development and effective intervention.

This fragmentation cannot be considered merely a technical coordination problem. This phenomenon is indicative of a systemic issue, namely that the prevailing environmental governance mechanisms impede rather than facilitate participation [29]. The governance gap also reflects some actor-specific constraints in addition to these structural constraints. These limitations can be listed as limited organisational capacity, resource restrictions, and the lack of long-term strategic alliances among NGOs and local committees. Hence, the aforementioned gap in Akbelen is twofold: First, a serious structural problem is already rooted in Türkiye’s centralised governance system. Second, a relational problem stems mainly from irregular actor capacities and weak inter-scalar linkages. Whilst the increasing number of actors involved can be considered a positive factor, crucial structural issues—such as unequal access to information, participation in decision-making processes, and legitimate representation—remain unequally distributed among the actors. This clearly demonstrates that horizontal, transparent, and inclusive governance, an integral component of energy democracy, has yet to be institutionalised in the Akbelen case. Some comparable dynamics can be readily observed in other extractivist conflicts in the Global South. In these cases, nominal decentralisation coexists with highly centralised decision-making structures. These conflictual features of the governance regimes lead to similar patterns of symbolic participation and structural exclusion. As demonstrated in this framework, multiple forms of injustice—which are categorised as procedural, recognition-based, and spatial—are intertwined in the Akbelen case. Nevertheless, participation remains predominantly symbolic. It is evident that a multi-level grassroots mobilisation, organising, and solidarity network potential has emerged in Akbelen [64].

However, it is imperative to establish an equitable and sustainable basis for cooperation among the relevant actors in order to effectively realise this potential. In this instance, as in many others, the state bears responsibility for instituting a participatory decision-making process with all its social, political, and legal dimensions. In order to establish a multi-actor and multi-scalar energy justice governance, it is essential that national and global actors establish more intense relationships with local actors. These relationships should be based on mutual exchanges of all kinds of information—legal, scientific, and otherwise—and focus on public and media support.

4.3. Towards a Just Energy Transition: Lessons from Akbelen

The Akbelen case provides a notable framework for the evaluation of just energy transitions. As Sovacool et al. [40] aptly observe, decarbonisation policies at the global level predominantly concentrate on technical and market-based solutions (for the issue of just transition at this point, see [65]). This therefore results in the exclusion of local-scale expectations of justice demands. Similarly, Hainsch et al. [66] underscore that the energy transition should be firmly strengthened not only by technological advancement, but also via public trust, participation, and consideration of the socio-political context.

In this sense, the grassroots mobilisations in Akbelen exemplify both equitable distribution of resources and a holistic approach grounded in local knowledge, individual agency, and environmental sensitivity. McCarthy [67] also underpins this claim by proposing that a just transition necessitates a structural reconfiguration of socio-ecological relations (for debates on policy-making and transitional justice, see [68]).

L7-1, L6-1, and G2’s fundamental expectations regarding energy justice are as follows, respectively:

“Well, we look at it as a whole, (…) [not] just displacement. Really, the reduction of economic value, the reduction of social (…) [value], the destruction of land, the pollution of air and water… So, there is really more harm than benefit here. I mean, we know this now. I mean, everyone knows. We are saying, ‘Are we going to reach the electricity we produce in our homes like this?’“ (…) Our policies should no longer be based on something that destroys nature, human life, and the lives of living beings. (…) There are plenty of alternatives. So, it should be done in a way that does not harm nature, the forest, the villagers, or agriculture. We hear about Germany, how many months of sunshine do they get? Even so, all (…) houses have solar panels on their roofs. (…) Our hometown is already a land of sunshine…”

“We don’t want to get our energy from coal (…). (…) They should ask me first (…). Let them set up the wind [tribune]. Let them set up solar energy. Well, in democracy, there is no end to solutions. Of course, climate change happened. Where is the climate? (…) The climate has changed. The weather has changed. The balance of summer and winter has changed. In other words, our psychology as humans has been disrupted. Coal caused this. The era of black coal has come. Damn coal! I don’t want that black coal.”

“The mining activities carried out in Akbelen Forest involve serious violations not only in terms of ecological aspects but also in terms of energy justice and democratic participation principles. The allocation of forested and olive grove areas for fossil fuel-based energy production without the consent of the local population is indicative of an energy policy lacking social legitimacy. As a global organisation, we argue that energy systems should be evaluated not only for their economic but also for their ethical and social dimensions. The grassroots mobilisation in Akbelen is a strong expression of the call for a just transition from fossil fuels, participatory governance, and community-based energy policies.”

This study underscores that multi-level governance has a pivotal role in promoting effective and inclusive cooperation between the national government, municipalities, civil society, and other potentially affected parties. It is evident that strategies for energy transition have been influenced by bottom-up approaches and participatory processes, as evidenced by cases such as the Greek islands. These strategies have the potential to foster the establishment of democratic and enduring energy communities [69].

Conversely, the absence of analogous institutional and participatory mechanisms is apparent. It is evident that this key gap has a detrimental effect on the scope and quality of democratic participation, thus weakening ecological and social resilience. For this fundamental reason, the concept of energy democracy must not remain at the theoretical level, but must become a practical and institutional tool for sustainable and just environmental governance.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the Akbelen Forest case to explore how spatial and procedural dimensions of environmental injustice unfold in the context of extractive energy projects in Türkiye. The analysis was based on qualitative fieldwork and was grounded in the frameworks of environmental justice and energy democracy. It revealed that the mining-driven enclosure of forest lands not only restricts access and erodes livelihoods but also fosters new forms of spatial consciousness and grassroots mobilisations. They, predominantly led by local residents and activists, demonstrate the transformative potential of participatory, place-based environmental politics.

The findings emphasise that current environmental governance mechanisms in Türkiye are inadequate in ensuring meaningful participation, recognition, and representation for affected communities. In contrast to the passive acceptance of top-down decisions characteristic of conventional communities, these groups articulate demands for justice, autonomy, and ecological integrity, often outside formal institutional frameworks. The Akbelen case thus contributes to broader debates on just energy transitions. It emphasises that socio-political inclusion of all affected actors and the expansion of local government authority are necessary for sustainable and democratic energy futures.

This study therefore demonstrates the following policy implications: It is imperative to (i) enhance the efficacy of participatory governance in environmental decision-making processes, by institutionalising mechanisms that facilitate early, inclusive, and ongoing consultation with affected communities (see [70,71]). The institutionalisation of these participatory tools—particularly deliberative democracy mechanisms, which are among the most relevant—remains insufficient in Türkiye, as evidenced by rural cases such as Akbelen. As far as the Turkish context is concerned, these participatory structures could comprise some essential and typical practical tools of deliberative democratic decision-making processes: citizen assemblies, community-based energy cooperatives, environmental ombudsman/mediation mechanisms, local referenda in project-affected districts, and digital participation platforms supported by transparent data sharing. Moreover, it is imperative to (ii) acknowledge the validity of indigenous ecological knowledge and cultural affiliations to the land in energy planning processes, particularly in forested and rural regions; (iii) adopt a multi-scalar governance approach that fosters collaboration between local governments, civil society, and national authorities to address spatial justice and sustainability; (iv) ensure transparency and accountability in energy and land-use policies, particularly in contexts involving privatisation, expropriation, and long-term ecological risks; and (v) provide support for the emergence of community-based energy models aligned with the principles of energy democracy.

Some particular mechanisms could consist of legal frameworks empowering energy cooperatives, incentives for community-owned renewable projects, and the institutionalisation of local–national consultation platforms. In these platforms, rural communities should be represented alongside state and private actors. This approach is key to reducing socio-environmental conflict and enhancing resilience. The purpose of recommending such concrete mechanisms in this study is to underline that the development of participatory governance structures in Türkiye necessitates not only normative commitments but also institutional innovations suited to local socio-political realities.

It is important to note that the aforementioned 2025 jurisprudence by the Council of State indicates how legal avenues still have the potential to enhance participatory accountability. The necessity to establish institutional mechanisms is thus underscored. Furthermore, it underscores the pressing necessity to proactively fortify procedural mechanisms that are capable of cultivating justice in environmental governance.

These concluding remarks are also demonstrated in the actor relationships visualised by a network graph. While the multi-actor structure initially established by Akbelen represented a line of grassroots organising, it appears that there is, in fact, a lack of coordination among these actors at different levels. This finding suggests the presence of a governance deficit. The Akbelen example demonstrates that a mobilisation that began at a local level has evolved over time into a broader mobilisation, primarily due to the participation of actors at different scales. Nevertheless, the same example also demonstrates that communication and interaction networks among actors remain quite limited.

Consequently, the absence of collaborative action among the relevant stakeholders has served to diminish the efficacy of the multi-level structure. The most significant conclusion is that the mere existence of participatory mechanisms is insufficient in environmental decision-making processes. The key lies not only in institutional participation but also in establishing a foundation for equal, transparent, and sustainable cooperation among the various actors involved in the process. Conversely, the practical implementation of energy democracy remains quite limited.

In conclusion, the objective of this study is to provide a critical evaluation of the currently applied energy policies, without portraying the Turkish state as an inherent problem. The Turkish state, which is a central and important actor in this context, can also be part of the solution. Concepts such as energy supply security, public interest, and national interest, which are frequently emphasised within the framework of official discourse by the Turkish state, are indeed legitimate and indispensable frameworks not only in Türkiye’s policy-making but also in that of other states.

However, this study emphasises the problems that could arise from defining these frameworks solely based on existing energy sources and centralised production-management models. In this context, such an approach has the potential to hinder social legitimacy and ecological sustainability. A pivotal solution therefore lies in redefining public interest and national interest. Nevertheless, policy-making processes should be founded upon multi-actor, multi-level, and multi-dimensional participation mechanisms. The establishment of a governance mechanism that prioritises energy democracy and incorporates local knowledge and needs is imperative for the successful implementation of this approach. The Akbelen example demonstrates that the further democratisation of energy policy can enhance social justice in Türkiye and strengthen the legitimacy of the state and public trust in similar cases.

Notwithstanding the potential contributions of these comprehensive conclusions, this study is not without its limitations. A significant strength of this study is its objective to establish a dialogical framework at the intersection of energy democracy and environmental justice, integrating these concepts with academic and political debates. The objective of this study is twofold: firstly, to provide a more profound theoretical perspective, and secondly, to offer practical insights into the real-world applications of the subject matter. This will be achieved by means of an examination of the Akbelen case. Nevertheless, despite this endeavour, the research is grounded in a single case study due to not finding a similar case that had multi-scale grassroots attempts yet received no spatial gain (especially in Türkiye) and a comparatively limited fieldwork period (including the number of actors who did not respond), which imposed constraints on the number and diversity of interview participants. Despite endeavours to incorporate a diverse range of local actors and perspectives, the findings may not fully encapsulate the intricacies of energy-related conflicts in other regions or institutional contexts. Furthermore, the exclusive utilisation of qualitative methodologies, whilst facilitating depth and nuance, may constrain the generalisability of the conclusions derived.

However, it should be noted that these limitations may also present several important areas of opportunity for future research. It is recommended that future research adopt a comparative multi-case approach across different geographies experiencing similar extractive interventions in order to address the identified limitations. Longitudinal studies could also shed light on how community-based actions evolve over time and what institutional, ecological, or legal impacts they produce. Furthermore, the integration of quantitative data—including environmental degradation metrics, energy output figures, and socio-economic indicators—has the potential to enhance analytical depth and broaden the empirical scope. Conducting such studies would facilitate the integration of localised community-based actions within the overarching framework of global energy transitions and multi-scalar environmental governance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.E.; methodology, H.E., G.T. and Y.S.A.; software, G.T.; validation, H.E. and Y.S.A.; formal analysis, H.E. and Y.S.A.; investigation, H.E., G.T. and Y.S.A.; resources, H.E., G.T. and Y.S.A.; data curation, H.E. and Y.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.E., G.T. and Y.S.A.; writing—review and editing, H.E. and Y.S.A.; visualization, G.T.; supervision, H.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of AKDENIZ UNIVERSITY (protocol code 28.03.2024-887996).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Energy Institute (EI). Statistical Review of World Energy. 2024. Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Schlosberg, D. Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environ. Politics 2004, 13, 517–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temper, L.; del Bene, D.; Martinez-Alier, J. Mapping the frontiers and front lines of global environmental justice: The EJAtlas. J. Political Ecol. 2015, 22, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erensü, S. Powering neoliberalization: Energy and politics in the making of a new Turkey. Energy Res. Soc. Sci 2018, 41, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News Türkçe. Akbelen Ormanı’nda Dört Yıldır Direnenler Anlatıyor: “Bir Tek Ağacı Bile Kaybetmemeliyiz” [Those Who Have Been Resisting in Akbelen Forest For Four Years Say: “We Must Not Lose A Single Tree”]. 25 July 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/turkce/articles/cx0w9n7vkqjo (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Limb, L. “We Will Not Give Up”: How a Turkish Forest Became the Site of Fierce Coal Mine Resistance. Euronews. 2023. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/green/2023/07/28/we-will-not-give-up-how-a-turkish-forest-became-the-site-of-fierce-coal-mine-resistance (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Associated Press. Locals Vow to Keep Fighting to Save a Forest in Southwest Turkey After the Chainsaws Finish Work. AP News. 2023. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/akbelen-ikizkoy-turkey-forest-mining-environment-protest-b7be1431daa5614aa0b7d1f81d47669c (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Stavrides, S. Common Space: The City as Commons; Zed Books: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. Writings on Cities; Kofman, E.; Lebas, E., Translators; Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens, M.; Kostakis, V. Towards a New Reconfiguration among the State, Civil Society and the Market. J. Peer Prod. 2015, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, A. Working with Strangers in Saturated Space: Reclaiming and Maintaining the Urban Commons. Antipode 2015, 47, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffentzis, G.; Federici, S. Commons against and beyond Capitalism. Community Dev. J. 2014, 49, i92–i105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News Türkçe. BBC 100 Kadın 2024: Listede Kimler Var? [BBC 100 Women 2024: Who’s on the List?]. 3 December 2024. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/turkce/resources/idt-4f79d09b-655a-42f8-82b4-9b2ecebab611 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Borras, S.M., Jr.; Franco, J.C.; Isakson, S.R.; Levidow, L.; Vervest, P. The rise of flex crops and commodities: Implications for research. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waorani of Pastaza v. Ecuadorian State. Decision by the Pastaza Provincial Court on Free, Prior and Informed Consent and rights of nature. Tribunal de Garantías Penales de Pastaza. 2019. Available online: https://www.derechosdelanaturaleza.org.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/SENTENCIA-PRIMER-NIVEL.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Avila, S. Environmental justice and the expanding geography of wind power conflicts. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosius, J.P. Prior Transcripts, Divergent Paths: Resistance and Acquiescence to Logging in Sarawak, East Malaysia. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1997, 39, 468–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N.; Honneth, A. Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-Philosophical Exchange; Golb, J.; Ingram, J.; Wilke, C., Translators; Verso: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. On law and disagreement. Some comments on “interpretative pluralism”. Ratio Juris 2003, 16, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G. Beyond distribution and proximity: Exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice. Antipode 2009, 41, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]