1. Introduction and Scope

Since the 1970s, the concept of cultural heritage (CH) has evolved from a narrow focus on preserving monumental architecture and designated sites to a broader, more dynamic understanding that includes living traditions, intangible practices, and the sociocultural processes that sustain them [

1,

2,

3]. This evolution has been shaped by critical milestones such as the European Charter for the Conservation of Architectural Heritage (1975) and the Amsterdam Declaration (1975), which introduced the principle of integrated conservation—embedding heritage within community life, urban planning, and socio-economic processes [

4,

5]. Today, CH is increasingly recognized as a socially constructed and dynamic phenomenon that reflects and validates community identity across time and space [

3,

6].

Within this expanded heritage discourse, the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach—formally adopted by UNESCO in 2011—represents a conceptual and operational shift from monument-focused preservation toward a systems-based understanding of urban heritage [

7,

8]. The HUL approach integrates complementary principles, concepts, and scopes previously addressed separately and adopted in earlier European and international recommendations and charters. The HUL framework acknowledges that cities are complex, layered systems where natural, cultural, tangible, and intangible elements are interdependent, and where identity is shaped by the interplay of urban morphology, built form, landscape, and community values [

1]. This holistic perspective moves beyond the “heritage-as-object” paradigm to consider “heritage-as-process,” recognizing the continuous adaptation of cultural values and physical spaces to contemporary needs [

9].

In the context of sustainable development, HUL and CH play indispensable roles. Heritage assets can foster place-based innovation, enable adaptive reuse and circular economy strategies, support cultural diversity, and provide ecological benefits through the conservation of traditional landscapes and practices [

10,

11,

12]. Moreover, heritage strengthens local identity and community resilience, making it a critical asset in addressing global challenges such as climate change, rapid urbanization, and social fragmentation [

13,

14,

15]. The UN’s Habitat III agenda explicitly states that urban heritage constitutes a social, cultural, and economic resource that should be safeguarded and leveraged through participatory approaches [

16].

Yet, despite their potential, both HUL and CH remain underrepresented in international sustainable development frameworks. In the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda, CH appears explicitly only in Goal 11, target 11.4—focused narrowly on safeguarding heritage—without systematic integration into broader targets on climate action (SDG 13), poverty alleviation (SDG 1), or economic growth (SDG 8) [

15,

17,

18]. This marginalization stems from several interrelated factors. First, heritage is often still perceived as a “luxury” concern, secondary to infrastructure, economic growth, and security priorities [

15,

19]. Second, the legal frameworks governing heritage are fragmented and inconsistent, with varying definitions and levels of protection across jurisdictions [

20,

21]. Third, global agreements frequently treat heritage as a static object to be safeguarded, rather than as an evolving process embedded in community life and urban systems [

14]. Finally, a persistent policy–practice gap exists, as heritage policy and urban development policy remain siloed, with insufficient cross-sectoral governance to operationalize heritage as a driver of sustainability [

22].

This paper argues that embedding the HUL approach and a systemic understanding of CH into urban development strategies is essential for achieving sustainable cities that balance growth with cultural and environmental integrity [

7,

11]. We will use cases where heritage has been a resource for urban and regional development (the Halland Model) and examples from European and Asian Capitals of Culture programs to argue how heritage can move from a marginal consideration to a central component in sustainable urban policy. By linking theory with practice, we seek to bridge the gap between heritage discourse and its implementation in the pursuit of holistic, people-centered, and resilient urban development.

2. Research Questions and Conceptual Framing

This paper explores how HULs—or heritage systems—can serve as enablers and resources for sustainable urban development. In doing so, it addresses the following research questions: How can heritage systems function as a starting point for sustainable urban development processes? To support this inquiry, several sub-questions are considered: What is the current state of the literature on this? What principal recommendations can be developed? What are the specific models used? Are there principles to follow for a “successful” process? What are the success factors and obstacles? And what preconditions and resources are required for successful processes?

This research employs a qualitative, multi-case methodology grounded in systems thinking. First, a comprehensive literature review was undertaken to examine global and regional policy frameworks, scholarly debates, and prior empirical studies on cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. A conceptual framework integrating value-based and people-centered approaches was developed to guide the analysis. Specific case studies—spanning Europe and Asia—were chosen to capture diverse sociocultural, political, and economic contexts. Data collection combined documentary analysis, stakeholder interviews, and observation of implemented projects. Cross-case thematic coding identified recurring patterns, enabling a comparative analysis of strategies, enablers, and barriers. The methodology emphasizes triangulation to ensure the validity and robustness of findings. Insights were refined through expert consultation workshops to enhance practical applicability. This approach allows for both theoretical advancement and context-sensitive recommendations. The design also ensures that heritage systems are analyzed as dynamic, interrelated processes rather than static entities.

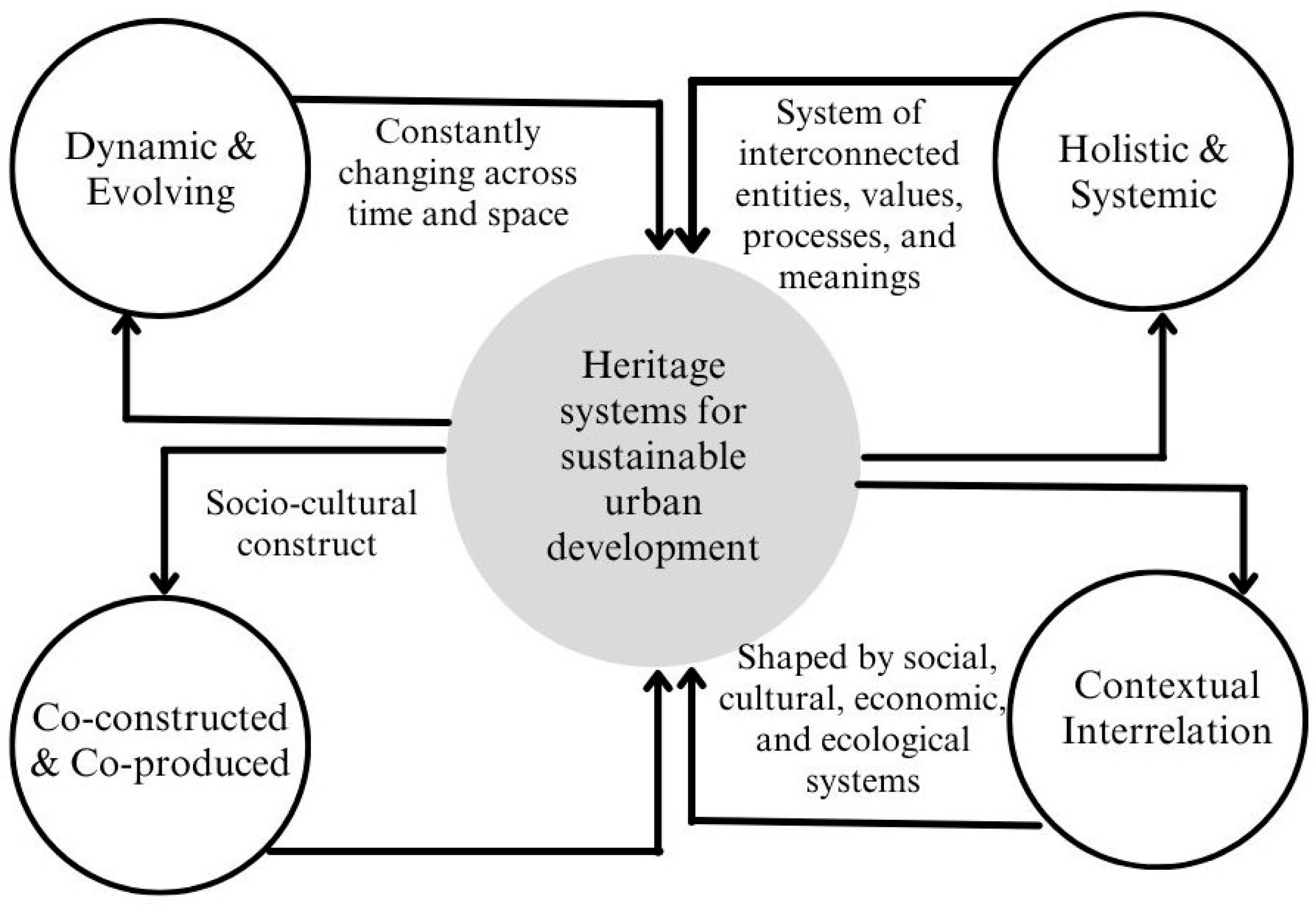

In approaching these questions, this research draws on a contemporary conceptualization of CH (

Figure 1), as formulated by scholars such as Salvador Muñoz Viñas, Cornelius Holtorf, and others. This conceptualization is based on a holistic, systemic view of heritage that acknowledges entities, processes, values, and other intangible dimensions as integral parts of a heritage system. This system approach highlights the continuous interaction and interdependence between heritage and its surrounding urban elements—social, cultural, economic, and environmental. Reflecting this paradigm, scholars now often conceptualize urban heritage as “constructed” or “produced” through ongoing processes involving multiple actors and forces, rather than merely inherited or static [

23]. Central to this discourse is the notion of co-construction, which emphasizes that urban heritage is collaboratively shaped through the dynamic interactions among communities, institutions, and physical elements of the city. This perspective aligns with emerging frameworks in critical heritage studies that stress participatory, bottom-up knowledge production and management [

24,

25].

The remainder of this article is structured to explore the relationship between CH and sustainable urban development through both theoretical analysis and practical case studies.

Section 3 introduces the evolving understanding of CH by examining heritage as a system, tracing its development from traditional monument-focused approaches to more integrated, systemic, and socially embedded perspectives.

Section 4 explores the opportunities and challenges of linking CH with sustainable development, drawing from global and regional policy frameworks, research findings, and project examples that illustrate heritage’s potential contribution to social, economic, and environmental goals.

Section 5 focuses on the role of Capitals of Culture programs as incubators for sustainable heritage-led urban development, offering concrete examples of how cultural policy can foster long-term transformation.

Section 6 presents key findings from selected case studies, highlighting how heritage-based planning contributes to sustainability goals. Finally,

Section 7 discusses the implications of the study, identifies the gap between policy and practice, and highlights the challenges and risks associated with implementing holistic heritage strategies in contemporary urban development.

3. Heritage as a System: Toward a New Heritage Approach

The concept of CH has significantly evolved since the beginning of the contemporary conservation movement in the 19th century. Initially focused on individual (outstanding) monuments and mainly tangible heritage, the understanding of CH today is fundamentally different: “(...) ‘heritage’ (is seen) as a social and political construct encompassing all those places, artefacts and cultural expressions inherited from the past which, because they are seen to reflect and validate our identity as nations, communities, families and even individuals, are worthy of some form of respect and protection” [

2].

The conservation movement started in the mid-20th century with a clear focus on castles and churches [

26]. This was followed by a greater interest in historic ensembles and whole built environments. This broadened perspective included the “in-between” listed buildings in conservation efforts. These ensembles comprised listed and non-listed buildings, but were still determined by sets of buildings [

27]. A significant milestone came in the 1970s, when the Council of Europe declared the European Year of Architectural Heritage (1975). This coincided with the European Charter for the Conservation of Architectural Heritage, adopted by the Council of Europe, which emphasized the concept of “integrated conservation” as essential for effective heritage management [

4]. The Amsterdam Declaration, also issued in 1975 [

5], further established integrated conservation as a contemporary guideline [

5]. Architectural heritage was to be integrated into community and regional planning, with social and economic issues, and in co-operation with citizens. In particular, the interaction between people and the surrounding built environment was emphasized. Preservation issues were to be included in all urban planning, not just for listed buildings.

The 2011 UNESCO HUL Recommendation introduced additional layers related to functions and values, mainly inspired by urban morphologists like Conzen [

28]. With the professionalization of the heritage sector in the 20th century and the expansion of heritage assets—including new categories of CH—the concept and understanding of CH have evolved considerably, recognizing its complexity. This shift moves away from a traditional, sector-specific, one-dimensional perspective toward a more integrated, multidimensional, community-focused, dynamic, and systemic approach that aligns various policy areas and resources [

29].

While this paper discusses heritage as a system, moving from individual properties to larger ensembles and the HUL, it should also be noted that much of this thinking has been in practice for decades and is not entirely novel. Historic districts as ensembles have been designated in the United States since the 1970s, and heritage conservation areas—effectively micro-landscapes—have been formally recognized in Australia during the same period [

30,

31]. A key milestone in this evolution was the 1999 Burra Charter by ICOMOS Australia, which provided renewed emphasis on a value-based approach to CH by providing guidance for the sustainable management of places of cultural significance. This approach was further developed through research by the Getty Conservation Institute [

32,

33], which aimed to move beyond Western value systems and address diverse cultural contexts in Asia, Africa, and South America. Recognizing this longer trajectory situates the HUL within a broader continuum of heritage planning innovations rather than as a sudden paradigm shift. The HUL draws on a century-long tradition of practice and on existing regulatory frameworks and policy documents to promote a holistic, integrated, and value-based approach to CH [

34].

This evolving understanding of CH has driven a parallel transformation in the conservation of built heritage and the broader heritage sector. In many cases, the focus has shifted from safeguarding individual monuments to managing complex historic environments, and from emphasizing tangible heritage with minimal intervention to promoting conservation through active participation, prioritizing community well-being. Nowadays, three distinct yet compatible paradigms coexist: preservation, which emphasizes authenticity; conservation, centered on adaptive reuse; and heritage management, which prioritizes meaning and experience [

35]. Janssen et al. [

36] further identify three emerging approaches: conservation as a sector, which treats built heritage separately from spatial development (silo-thinking); conservation as a factor, which views heritage as a resource; and conservation as a vector, where built heritage serves as the foundation for sustainable spatial development. In a similar vein, conservation can be understood as a shift in focus from the protection of monuments through legislation (“protect the buildings”), via the use of traditional crafts and materials (“restore the buildings”), to the adaptive reuse of conserved and rehabilitated historic environments (“use the preserved and conserved buildings”) [

9]. Though these approaches have evolved independently, they remain equally relevant today [

22]. As a result, the preservation of buildings and monuments can no longer be considered in isolation from their use and urban context, necessitating a holistic and systemic perspective.

At the same time, Harold Kalman recognizes that the understanding of heritage has changed, noting that “A view shared by many current writers on heritage theory is that our understanding of heritage conservation, including values and best practices, is socially constructed and not absolute” [

3] (p. 52). Over time, CH has become increasingly more popular, diverse, and complex. Growing interest in its use and function within society has had significant implications for the field of urban heritage. As the focus on utility and purpose has expanded, various epistemologies, methods, and disciplines have begun to explore the subject. Geographer Simone Sandholz [

23] (p. 3) argues that the heritage discourse has evolved in two key ways: first, through a shift in content and scale, from individual buildings to larger ensembles and the HUL; and second, through the growing influence of international actors and role models.

Wetterberg [

37] describes conservation as a fundamentally contested concept, understood as taking something from the past and consciously bringing it into the future. Conservation as a discipline lies at the intersection of the objects of conservation—whether material or intangible—the meanings people attribute to them, and the professional practices that have developed in relation to both. It explores the conditions for the care and survival of cultural objects from cultural, social, and scientific perspectives, as well as social and cultural processes that lead to the definition and designation of certain cultural objects as CH. The term “cultural object” is generic and encompasses cultural artefacts of various kinds, from newspapers and ancient finds to medieval cathedrals and contemporary urban environments [

38].

Critically, any such process—whether community-based or expert-driven—relies on the identification and negotiation of heritage values. These values are mutable, shaped by generational perspectives and subject to the “shifting baseline syndrome,” whereby each generation redefines significance based on its own lived experiences and collective memory [

39]. Explicitly acknowledging this mutability is essential to understanding why heritage priorities, community attachments, and expert assessments may diverge over time.

The shift toward a more complex understanding of heritage encourages systemic approaches that are better equipped to address higher levels of complexity and engage multiple stakeholders [

38]. For the Habitat III conference in Quito on “Housing and Sustainable Urban Development”, the UN recognized that “Urban heritage represents a social, cultural, and economic asset and resource reflecting the dynamic historical layering of values that have been developed, interpreted, and transmitted by successive generations as well as representing an accumulation of diverse traditions and experiences. Urban heritage comprises urban elements (urban morphology and built form, open and green spaces, urban infrastructure), architectural elements (monuments, buildings), and intangible elements. Urban heritage conservation, or urban conservation, relates to urban planning processes aimed at preserving cultural values, assets, and resources through conserving the integrity and authenticity of urban heritage, while safeguarding intangible cultural assets through a participatory approach” [

16] (pp. 1–2).

Alongside the evolving understanding of CH, urban heritage is now viewed more systemically, continuously interacting with its surrounding elements rather than existing in isolation. Some scholars argue that what we now consider to be urban heritage is not merely an organically “grown” asset but rather a constructed or “produced” entity shaped by urban planning and preservation efforts [

23,

40]. This evolving understanding of heritage—rooted in systems thinking and aligned with broader spatial, social, and cultural dynamics—has significant implications for how heritage is integrated into sustainable development frameworks. The next section explores related opportunities and challenges from both conceptual and practical perspectives.

4. Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Development: Opportunities and Challenges

The 2013

Hangzhou Declaration: Placing Culture at the Heart of Sustainable Development Policies [

41] emphasizes the need to strengthen the role of culture in various fields, ranging from economic development and social cohesion to poverty reduction. The document proposes several strategies for integrating culture into sustainable development, including fostering peace and reconciliation through culture, ensuring cultural rights for all, and leveraging cultural and tourism sectors to create jobs, particularly for youth, women, and marginalized communities. Additionally, it highlights the importance of promoting environmental sustainability by safeguarding traditional skills and knowledge, strengthening resilience to disasters, addressing climate change through local traditional knowledge, and developing culture-aware urban policies [

41].

At the European level, CH has been given a stronger position in several communications and political documents such as Towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage for Europe, the EU agenda for cultural heritage research and innovation, the European Heritage Label, the New Agenda for Culture, and the 2019–2022 Work Plan for Europe (European Union, 2014 [

29]). Nevertheless, studies show that only a few regions in Europe emphasize CH within their regional smart specialization strategies [

10]. Moreover, while CH is increasingly acknowledged for its potential to address broader developmental challenges, it is still largely viewed as a ‘vulnerable’ asset to be protected, rather than as a driver of development and resilience [

13]. Furthermore, there is noticeable resistance among developed countries to integrating cultural industries within the international development agenda, as economic crises, global competition, and security challenges have taken precedence [

19].

Currently, numerous policymakers, scholars, and stakeholders recognize CH as a vital resource for citizens and a critical element of competitive advantage, rather than an obstacle to economic growth or a luxury [

9,

42]. Several scholars and projects stand out, offering a range of practical, cross-disciplinary case studies that highlight the significant role of heritage in promoting sustainable development and advancing the SDGs across various contexts [

43]. A key contribution is the volume

Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action [

44], which goes beyond theoretical considerations to focus on the implementation of the 2011 UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. It explores the integration of heritage management into the broader context of sustainable urban development, using 28 cities as case studies.

This integration is further exemplified by two notable initiatives that have positioned CH as a cornerstone in local development strategies: HerO (Heritage as Opportunity) and COMUS (Community-Based Urban Development Project). These projects reflect a shift in the perception of CH, emphasizing its growing significance for local communities and its social and economic impact [

40]. Another notable example is the research report by PRAXIS, which analyzes how heritage research—through various approaches and collaboration between researchers—addressed complex development challenges in areas including poverty alleviation, disaster response and resilience, and adaptation to climate change [

45]. The report highlights sixteen projects that focus on the centrality of human–nature interaction to tackle climate change and foster community resilience. These projects demonstrate how heritage can contribute to achieving multiple SDGs. Specifically, they support SDG 2 (Target 2.4.2) by promoting sustainable agriculture and food systems, SDG 13 (Targets 13.1, 13.2, 13.3, and 13.b) by addressing climate action and strengthening resilience to climate-related hazards, and SDG 15 (Target 15.3.4) by encouraging the preservation of ecosystems and biodiversity. This research exemplifies the role of heritage as a tool in sustainable development, offering innovative solutions for community resilience in the face of environmental challenges. Additionally, 17 projects related to human rights, inequality reduction, and minorities’ inclusion have used art, creativity, and emotional engagement to achieve their goals. Through festivals, digital heritage, digital sharing, and other expressions, they amplify marginalized voices, challenge official narratives, and contribute to social change, peacebuilding, and symbolic reparation.

Building on these insights, Giliberto and Labadi [

43] critically examined the potential of CH as a tool for sustainable development, focusing on its economic, social, and environmental contributions. By analyzing three heritage-focused projects in the Middle East and North Africa, the authors highlighted how CH can address global challenges like poverty alleviation, gender equality, and environmental sustainability through the promotion of locally driven tourism; enhancement of heritage-based economic sectors; gender mainstreaming and political representation; and women’s empowerment via new income generation activities. Moreover, Guzmán et al. [

20] analyzed 19 reports to examine the integration of CH as a means for sustainable development. Their findings revealed three levels of inclusion: (1) the strategic level, (2) the operational level, and (3) the monitoring level [

20]. They also identified two primary approaches to heritage from an urban development perspective: viewing it as cultural capital and as an urban phenomenon requiring tailored urban management.

Building on the recognition of CH’s contribution to sustainable development and resilience, Gustafsson and Ripp [

11] elaborate on heritage-based urban development and recovery. They propose a metamodel for heritage-driven urban recovery, drawing on successful case studies such as the COMUS project and the Halland model. These models highlight how CH can be leveraged not only for environmental sustainability, but also as a means to foster social cohesion and economic revitalization in urban contexts. Going beyond the predominant focus on the protection and conservation of CH during disaster events and recovery phases, the proposed metamodel offers guidance on utilizing CH for urban recovery processes, while considering both the system and the context in which they occur [

11].

CH is a sociocultural construct, and heritage values are ambivalent, dissonant, and politicized [

6,

46]. By the end of the twentieth century, key documents and recommendations for the conservation and management of CH began to emphasize the adoption of a value-based approach [

8,

47,

48]. In parallel, scholars and organizations have developed various assessment methods and typologies of heritage values—ranging from aesthetic, social, and historical to economic, political, and ecological [

32,

33]. However, applying a value-based approach remains challenging, especially when traditional methods for evaluating significance are questioned for their ability to capture diverse and changing perspectives [

49].

Crucially, heritage recognition is never politically neutral. Heritage is often strategically curated by political actors to legitimize dominant narratives and marginalize dissenting ones. This dynamic is especially visible in the Chinese context, where heritage sites associated with minority communities have been systematically neglected, repurposed, or demolished under the guise of modernization or development. As recent scholarship shows [

50,

51], such practices function to consolidate state power and suppress alternative cultural identities. Similar processes can also be observed in other contexts where heritage designation, funding, and public celebration are aligned with ideological and economic agendas. Mechanisms such as the designation of Capitals of Culture, while positioned as inclusive, often reflect calculated choices about which spaces and stories are preserved, privileging certain narratives while excluding others. Recognizing this political selectivity is critical for a nuanced understanding of heritage as both a cultural and political tool.

When CH is perceived as a dynamic process of living practices [

14], concerns of heritage preservation in disaster management shift from focusing on the physical to addressing the living aspect. While the

physical space serves as a support system in recovery, resilience equally stems from the

lived space, which encompasses community institutions, cultural practices, and traditional knowledge [

14,

52]. This highlights the necessity of incorporating heritage-based and community-based human agencies and systems into sustainability and resilience frameworks. Traditional practices and knowledge systems, such as agricultural methods and construction techniques, demonstrate sustainable human–environment interactions, helping communities adapt to diverse environmental and societal challenges while preserving their cultural identity [

53]. These practices offer proven strategies for disaster mitigation and strengthening community adaptive capacity [

52]. For instance, in Timbuktu, the use of traditional practices and materials, along with the involvement of local artisans, played a crucial role in restoring and preserving CH in the face of climate change [

53].

Hosagrahar et al. [

15] identified several misconceptions regarding the relationship between CH and sustainable development. One common misconception is that economic development in emerging economies is urgent, while heritage conservation is a luxury, assuming that these goals are mutually exclusive [

15]. Another confines heritage conservation to restoration, fearing development will lead to unchecked commercial expansion—in reality, the challenge is to ensure inclusive and sustainable growth. Others assume that physical characteristics alone shape social behavior, neglecting cultural ties, or that social cohesion rests solely on shared norms, overlooking how diversity can also foster unity. The notion that heritage is irrelevant to contemporary life is similarly flawed; heritage is ever-present, shaping our lived environments. Finally, the idea that heritage conservation is financially unfeasible ignores evidence of its long-term social and economic benefits when supported by inclusive governance and careful assessment [

15].

While international frameworks and research have emphasized the integration of heritage in sustainable development, concrete initiatives are required to translate these goals into practice. One prominent example is the Capital of Culture model, which—though not free from political selectivity—demonstrates how temporary cultural initiatives can catalyze long-term heritage-led urban development.

5. Capitals of Culture as Incubators for Sustainable Heritage-Led Urban Development

One widespread and diffused example of working towards the HUL approach and Heritage Systems thinking can be found within the City/Capital of Culture (CoC) program. While focused on cultural events and activities rather than strictly on heritage, it is especially flexible and adaptable to a wide range of contexts and issues. Past research has clearly demonstrated this linkage between CoCs and heritage, with host cities using the opportunity of the event to develop new heritage narratives, protect at-risk sites, introduce new adaptive uses of heritage spaces, develop new cultural policies, and involve a diverse array of local communities [

54,

55].

The global spread of CoCs begins with the European Capital of Culture (ECoC) that began in 1985 and has since become the primary cultural policy of the European Commission [

53]. Hosted by more than 80 cities over the last 40 years, the program landed in major cities like Athens, Paris, and Florence in its initial years and more recently in the small cities of Bad Ischl, Eleusis, and Matera. Following the success of the ECoC, spinoff projects of varying scales and geographic spread have since arisen. These range from the intracity scale, like the London Borough of Culture, to the regional scale, like the Capital of Catalan Culture, national programs like the UK City of Culture and Italian Capital of Culture, as well as wider global territories like the Arab Capital of Culture or Culture City of East Asia [

56]. Often, these major cultural events are increasingly seen by local stakeholders and decision makers as opportunities to stimulate urban regeneration, enhance city branding, drive economic development, and expand the creative industries [

57]. Scholars have problematized key aspects of these events and their social and spatial impacts [

58]. Such critiques challenge the hyperbolic narratives of culture-led transformation, instead revealing uneven geographies of culture, differentiated cultural experiences, and diverse socio-economic realities [

58]. These debates underscore the importance of examining specific success cases where the hosting process became a catalyst for rethinking the city’s cultural heritage policies, governance models, and approaches to meaningful public participation.

In the case of the 2016 Wrocław ECoC, the process of bidding for and winning the event highlighted the potential of cultural policy to activate processes of development and transformation [

59]. The event enabled the recognition of new spaces as part of the city’s heritage, from industrial zones to Soviet-era brutalist architectural blocks, resulting in restoration projects and the insertion of new cultural uses (see

Figure 2). This helped to expand the thinking of heritage from beyond the historic core to include other areas of the city [

60]. The event also led to innovative participatory approaches in the development of events and projects during the ECoC. The public was invited to develop their own proposals as part of a microgrant system that saw cultural events held in ‘forgotten’ heritage spaces and highlight tangible and intangible memories, also addressing the difficult memories of WWII and the population exchange which occurred between German and Polish residents following the war. The success of this event program has been the development of a new cultural policy infrastructure that continues these efforts even following the close of the event. The microgrant system extended beyond 2016 to allow local residents to continue proposing and developing projects that engage with and expand the understanding of CH across the HUL of Wrocław [

60]. The ongoing continuation of these cultural heritage policies and actions results from the dedication of legacy funds to these efforts, as well as the consistent governance. In many events, the organizing body is disbanded following the event, and all of the built-up capacities are lost. Instead, in Wrocław, the Impart 2016 Festival Office was rebranded and continued as the Wrocław Culture Zone and played a key role in overseeing this long-term legacy [

61]. The ECoC initiative contributed to expanding conceptualizations of local heritage, expanding to include both more recent tangible heritage as well as intangible cultural activities by not only involving the local community, but putting them in a decision-making role to generate new projects.

In the case of Hull, the 2017 UK City of Culture (UKCoC) played a key role in both tangible urban regeneration and the intangible restoration of the city’s identity and heritage. Hull had long suffered from a negative reputation following a long period of socio-economic decline since the 1930s, and the UKCoC helped address these issues, with the city’s heritage ultimately playing a key role [

62]. With a significant presence of long-undervalued maritime heritage, the event served as an opportunity to educate, promote, and reinterpret this history through artistic and cultural events. One of the aims was to link the city’s heritage of its maritime industry, both tangible and intangible elements, with current industries manufacturing wind turbines to establish a continuity of its past and future. These efforts were successful in putting Hull ‘on the map’ once again within the national context [

63]. At the same time, it was also extremely successful in activating widespread participation with significant enthusiasm for volunteering to support the event organization and planning, an initiative continuing beyond the event [

64]. These efforts led to increased attention and ongoing investment in the city’s heritage, with a refurbishment of the Hull Maritime Museum that aims to establish this important heritage as part of the Yorkshire region [

65]. Through the event, heritage could be framed not only as part of the city’s heritage, but a key component to generate long-term, wider urban and territorial regeneration, connecting Hull to a much larger historic cultural landscape. In this case, the widespread public support, engagement, and volunteering to be part of the event led to a greater knowledge and appreciation of CH, establishing it as a key part of the city’s future development plans.

As part of the Italian Capital of Culture (ICoC), Bergamo (

Figure 3) and Brescia co-hosted the event in 2023 with the aim of establishing stronger territorial links between the two Lombard cities. The event was specifically granted to these two cities jointly as part of the post-COVID recovery efforts, as both cities were especially hard hit during the pandemic. The program development adopted an open-ended format that avoided the role of an artistic director to drive a singular vision, but rather promoted a bottom-up approach to adopt a variety of events and activities organized across the key themes of health, nature, innovation, and hidden treasures [

66]. The event organization also adhered to the Charter for Mega-events in Heritage-rich Cities to ensure the protection and promotion of heritage by responding to contextual needs, adopting inclusive governance models, thinking about the long-term planning legacies, and recognizing diverse communities and identities [

67]. The linking of the city occurred through the simultaneous hosting of paired events as well as the reinforcing of territorial and infrastructural connections. In particular, hiking paths and bike trails connected the two cities by activating the agricultural and mountain cultural landscapes that surround them. Additional train connections were added during the year to also enhance the exchange between these two cities, to encourage participation between the events and help develop a new regional pole to balance the centrality of Milan. Within Brescia, restoration projects and artistic events helped to promote the city’s lesser-known but important UNESCO World Heritage site, and NGOs like Line Culture used the event to organize new public activities and community events in the historic center using temporary architectural solutions [

68]. In this instance, the understanding of cultural heritage went beyond the individual building or even the urban scale to encompass a territorial and landscape dimension, highlighting a more holistic and widespread approach.

Beyond the European context, the city of Xi’an hosted the 2019 Culture City of East Asia (CCEA) event, which highlighted the city’s expansive built and urban heritage (

Figure 2). With a population of nearly 13 million, it represents a drastically different urban scale from the previous examples. Yet the CoC model can adapt to meet the different needs of different contexts. As the original capital city of ancient China, the city retains many important sites from over two millennia, most notably the UNESCO World Heritage site of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor that hosts the Terracotta Army, but also other listed sites including Weiyang and Daming Palaces and the Big and Small Wild Goose Pagodas. The CCEA provided the opportunity to organize a series of cultural events in heritage sites across the city. These events primarily focused on intangible heritage, organizing traditional music, theater, and dance performances. For example, the opening ceremony was held in front of the Southern Gate of the historic 14th-century Ming Dynasty city walls (see

Figure 4). The cultural programming of the event helped contribute to a set of urban development plans that, since 2005, have aimed at shifting the city’s growth from a post-industrialized model to establishing an urban center of heritage and culture [

69]. Current historic and cultural city plans project these aims until 2035, placing the event not as a final point of arrival, but rather as a stepping stone in a long-term strategy. The widespread distribution of the event through cultural activities spread across historic areas helped to highlight the wealth of the city’s heritage and activate it as a key resource for future development. The focus on intangible heritage also represents a shift away from large-scale heritage-led development schemes centered on built heritage to promote other dimensions of the city’s past.

These examples represent just a fraction of the possible cases that can be discussed from the numerous CoCs that are now actively taking place around the world. Yet these reflections from the ECoC, UKCoC, ICoC, and CCEA show the diversity and adaptability of these programs to align with and promote heritage as part of wider urban and cultural landscapes. These cases demonstrate how new cultural or temporary uses have been introduced into heritage spaces, often as ways to activate overlooked or undervalued historic areas. These strategies have been critical to changing not only the understanding or knowledge about this expanded urban heritage, but also to positioning it in a central role to drive social, economic, and cultural regeneration. Many of these approaches also involved various forms of public participation in the development of cultural programs or in the implementation of events. This wide level of inclusion was key to the expanded appreciation and valuing of heritage. They expanded the physical as well as mental conceptions of heritage, contributing to, if not intentionally then at least incidentally, the implementation of the HUL and long-term sustainable development, with heritage taking a central role. Bergamo and Brescia represent how these events can go beyond confined interpretations of heritage to engage with wider urban and cultural heritage landscapes.

Although Capitals of Culture are often temporary, they encourage innovative uses of heritage. Complementing these initiatives, the following section examines long-term, place-based models that integrate adaptive reuse and circular economy principles into heritage-led development. In Xi’an, the focus on intangible heritage responded to local needs by introducing new uses and highlighting aspects of the city’s history beyond the existing built heritage. However, hosting these events also carries risks. At times, they create a tunnel vision that focuses solely on the event itself, leaving little vision or resources for the post-event phase. As seen in Wrocław, long-term legacies depended on retaining the management expertise and capabilities developed during the event, rather than losing them. Tourism poses another common challenge: while these events partly serve to promote and attract visitors, the key challenge is finding the appropriate balance, avoiding both the overloading of historic places with mass tourism and the creation of local economies that are overly dependent on tourism or the festivalisation of heritage [

70].

Many questions are central to assessing whether CoCs genuinely support sustainable urban development, including culture for whom, which values are prioritized, and who participates in safeguarding these values. Without deliberate efforts to embed heritage into state and municipal planning instruments, empower community decision-making, and ensure inclusive governance at all stages—from bidding to legacy—the risk is that these events function as temporary branding exercises, reinforcing heritage hierarchies rather than transforming them [

2]. Moreover, the strong emphasis on tourism-driven regeneration in many CoCs can intensify heritage commodification, gentrification, and “festivalisation,” producing long-term sociocultural impacts that may undermine sustainability. The Liverpool 2008 CoC illustrates these tensions: political actors used a broad, anthropological notion of culture to drive regeneration and rebrand the city, but in doing so created contested place-myths that sanitized less celebratory aspects of urban life [

58].

6. Adaptive Reuse and Circular Economy in Heritage-Led Development: The Halland and CLIC Projects

The Halland Model is a valuable source of knowledge for understanding the role that cultural conservation can play in regional sustainable development [

71]. During the severe economic downturn in Sweden in the early 1990s, with high unemployment, particularly in the construction industry, a successful cross-sectoral collaboration between the construction industry partners, labor market policy, and the heritage sector was initiated. By providing unemployed construction workers with training in traditional building techniques and allowing them to practice in various restoration projects, historic buildings under threat of demolition were saved from destruction. In total, 100 buildings were restored in the Halland region on Sweden’s west coast, along with as over 30 buildings in the Baltic Sea region. More than 1200 unemployed construction workers were trained in traditional construction techniques. The project was characterized by its multi-problem-oriented approach: it was about saving historic buildings in danger of demolition (see

Figure 5), but also about further training the region’s construction workforce, increasing the skills of the entire construction industry and its various actors, saving existing jobs and creating new ones, etc.

Achieving such cooperation required all stakeholders to share a common vision: to prepare the region for the next boom in the transition to a post-industrial economy. Within this framework, it was possible to agree “to save the houses, save the jobs, and save the crafts”. Already in the first year of the ten-year project, the focus shifted from prioritizing historical values alone in the selection of buildings to be restored, toward emphasizing their new functions. This meant that in addition to developing planning documents for CH conservation, labor market policy, training, co-financing, etc., it was also necessary to develop systems for selecting future adaptive reuse and how it could act as a driving force for the transition to a sustainable society.

Adaptive reuse is defined as “any building work and intervention aimed at changing its capacity, function or performance to adjust, reuse or upgrade a building to suit new conditions or requirements” [

72]. The concept and techniques of adaptive reuse are applied to allow the present and future use of an abandoned or ineffective building, group of buildings, landscape, or site, changing/improving its functions and adapting its technology to new needs [

73], to a threshold that does not compromise its multidimensional significance, its “complex value”.

The EU Horizon interdisciplinary research project CLIC (Circular models Leveraging Investments in CH adaptive reuse) studied and discussed the multidimensional impact of sustainable CH management on local communities [

12]. The overall objective of the project was to identify evaluation tools to test, implement, validate, and share innovative circular financing, business, and governance models for systemic adaptive reuse of CH and landscapes, demonstrating their economic, social, and environmental benefits in terms of long-term economic, cultural, and environmental wealth. The concept and techniques of adaptive reuse were applied to enable the current and future use of an abandoned or inefficient building, group of buildings, landscape, or site, by modifying or improving its functions and adapting its technology to new needs, without jeopardizing its multidimensional significance or complex value. The adaptive reuse of CH was also considered one of the most efficient and environmentally friendly tools for modern urban development toward sustainability. Innovative financial, business, and governance circular models for the regeneration of CH were proposed and piloted to mobilize new investments to create shared value, in particular through cooperative, synergistic, sharing, and solidarity economic models (e.g., social enterprise models, impact investing). The adaptive reuse of CH is an integral part of the circular economy model that Europe is adopting to replace the current linear economy.

However, to be a full member of the sustainable development movement, it is often not enough to consider CH as an asset; it also needs to be implemented with rational circular business models. CH can be viewed as a “common good” [

74]. According to the results of the CLIC project, commons and circular economy are interrelated: the circular economy offers a co-evolutionary perspective for the conservation and management of the heritage, imitating nature’s auto-poietic processes [

10,

12]. A circular economy is a systemic approach to economic development designed to benefit businesses, society, and the environment. In contrast to the ‘take–make–waste’ linear model, a circular economy is regenerative by design and aims to gradually decouple growth from the consumption of finite resources [

75]. Circular models can be applied not only to industrial processes, but also to financing, business, and governance models, creating synergies between multiple actors, reducing the use of resources, and reusing/regenerating values, capitals, and knowledge.

CLIC studies have been conducted on identifying evaluation tools to test, implement, validate, and share innovative

circular financing, business, and governance models for the

systemic adaptive reuse of CH and landscape, as well as to demonstrate the economic, social, and environmental convenience in terms of long-lasting economic, cultural, and environmental wealth. The adaptive reuse of CH is also considered today as one of the most effective and environmentally friendly tools of modern urban development toward sustainability [

76]. The evaluation and comparison of the impacts of systemic adaptive reuse in the economic, social, environmental, and cultural dimensions is required, through the identification of specific criteria and indicators from the perspective of a circular economy. In the Västra Götaland region in western Sweden, the objectives of the CLIC project were to extend the circular economy perspective from other sectors (textile and furniture) to CH. The project aimed to support local actors in site development through both financial and process support, co-creating Local Action Programs for the reuse of disused CH, and the development of new circular business models for new investments in buildings and operations. Local Action Programs have been developed with bottom-up approaches within Heritage Innovation Partnerships. These actions were shaped in circular business model workshops involving local stakeholders from the public sector, enterprises, civil society, and cultural and creative industries, together with researchers. The Halland Model and the CLIC project highlight how adaptive reuse and circular economy principles can position CH as a driver of sustainable urban development. The following section expands the conversation beyond the two case studies, addressing broader reflections, policy–practice mismatches, and practical risks of implementing the HUL approach.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined how heritage systems, conceptualized through the HUL approach, can serve as dynamic enablers and resources for sustainable urban development. By systematically addressing the research questions posed in the introduction, it demonstrates that heritage systems function effectively as starting points for integrated urban development processes when understood as complex, multilayered systems, encompassing tangible and intangible cultural, social, economic, and environmental dimensions.

This research confirmed that successful heritage-led urban development relies on inclusive governance structures and active community participation to balance preservation priorities with contemporary urban needs. This aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 11, emphasizing sustainable cities and resilient infrastructure. The study identified key success factors, such as collaborative multi-stakeholder engagement, the adaptive reuse of heritage assets, and the integration of circular economy principles, exemplified by case studies like the Halland Model and the CLIC project.

Yet, heritage cannot be seen as neutral. At its core, heritage is politicized and contested across temporal, spatial, cultural–economic, and public–private axes [

25,

76]. As Smith and Akagawa [

6] argue, conflict and identity politics are inherent to heritage. This implies that even when heritage is framed by national policies, it is frequently managed at the local level, where tensions between “official” narratives and local historical knowledge, national identity and everyday sociocultural practices, and bureaucratic priorities and citizenship rights become most visible [

77]. The contested character of heritage reinforces the necessity of civic engagement, participatory planning, and inclusive governance, which have become central to international declarations on sustainable urban development. However, genuine inclusivity requires attention to conflict, negotiation, and power relations. Different modes of participation—ranging from informative to transformative—produce distinct outcomes in terms of knowledge sharing, decision-making, and the redistribution of power [

78]. Importantly, participatory heritage practices remain deeply dependent on local contexts and shifting configurations of governance, and thus require a critical assessment of what forms of participation are pursued and whose interests they serve [

79].

These dynamics become even more complex in contexts where international agencies and donors play a significant role. While UNESCO, the World Bank, the European Commission, and other actors often advocate for community empowerment, local activists and citizens in cities—particularly in the Global South—frequently remain the weakest link in decision-making. Procedural and discursive aspects of participation can be critical, and tensions often arise over whose cultural identity and social, political, and ecological values are prioritized in heritage management.

Against this backdrop, the analysis of cultural event programs such as Capitals of Culture illustrates both opportunities for urban regeneration and risks of gentrification, commodification, and sociocultural exclusion. These findings emphasize the need for deliberate, context-sensitive planning instruments that address the political, contested, and power-laden character of heritage while embedding it sustainably within urban policy frameworks.

This research contributes to the field by situating heritage not merely as a static asset to be preserved, but as a dynamic “common good” and a catalyst for social cohesion, economic resilience, and environmental sustainability. Integrating value-based, people-centered approaches provides a conceptual and practical blueprint for navigating the complexity of heritage-led urban development in diverse global contexts.

The following discussion is organized into two key subsections that further elaborate on the implications of this research. The first addresses the persistent gap between policy and practice, highlighting examples where CH is either well integrated or overlooked in urban development strategies. The second explores the main challenges and risks associated with implementing the HUL approach, focusing on governance, professional capacity, socio-economic impacts, and environmental vulnerabilities. Together, these sections contextualize the opportunities and limitations of heritage-led urban sustainability in contemporary practice.

7.1. The Policy–Practice Gap

The policy–practice gap exists in two directions. On one hand, there are contexts where policies explicitly include CH and culture as assets for urban development and for improving the quality of life of local communities. Examples can be found at UNESCO World Heritage Sites, where management plans have increasingly expanded beyond conservation and preservation to include strategies for sustainable urban development (e.g., Kairos, Hero, Regensburg).

At the regional level, for example, the Bavarian State Ministry of Science and the Arts underscores the importance of art and culture in fostering regional identity and stimulating innovation. By investing over half a billion euros into these sectors, the ministry supports a diverse range of cultural institutions and activities, positioning them as vital drivers of urban development

1. Similar efforts can be observed in Chemnitz, Germany which is focusing on CH to drive urban renewal. The city plans to implement policies that integrate culture into its development strategies, aiming to enhance social cohesion and stimulate economic growth

2.

On the other hand, in many cases, CH plays a significant role as a contextual or material resource, but this contribution is not explicitly recognized in local or regional policy frameworks. In such instances, policies often remain narrowly focused on the “safeguarding” dimension of heritage, defining the boundaries of acceptable change to historic urban fabric [

80]. Such approaches reveal a persistent disconnect between heritage’s actual societal role and how it is institutionally acknowledged. Moreover, even where policies adopt a more integrated view, implementation is conditioned by political contestation, conflicting priorities, and uneven capacities across governance scales. This underscores that the policy–practice gap is not merely technical, but deeply political, shaped by negotiations over whose values and identities are represented in heritage and whose are left marginalized [

25]. Accordingly, this study recommends strengthening interdisciplinary collaboration, fostering inclusive governance models, and leveraging innovative circular business models to sustain heritage’s multifaceted values.

7.2. Challenges and Risks in Applying the HUL Approach

The implementation of the HUL approach comes with a number of practical and systemic challenges that hinder its widespread adoption. One of the primary challenges of this approach is the conflict between the heritage conservation techniques and the demands of contemporary urban development. Urban areas are under constant pressure to expand infrastructural facilities, improve transportation systems in a sustainable way, and increase housing availability, which often conflict with the preservation of historic structures or landscapes. Planners and policymakers frequently struggle to balance these competing interests, especially when heritage sites lack formal protection or when local governments prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term sustainability. Additionally, there is a shortage of skilled professionals trained in interdisciplinary methods that combine heritage conservation with urban planning, social science, circular business models, and environmental management. Financial limitations further complicate matters, as heritage projects typically require substantial and sustained investment for documentation, restoration, maintenance, and community engagement. Smaller municipalities and developing countries, in particular, may lack the resources or political support to pursue such initiatives comprehensively.

Institutional fragmentation remains a significant challenge in the management of historic urban areas. Multiple government departments—such as culture, planning, tourism, and environment—often operate independently, or even at cross-purposes, resulting in incoherent strategies and duplicated efforts. This fragmentation is further complicated by the paradox between universality and locality in heritage governance. While the HUL approach promotes a holistic framework, its implementation varies widely due to massive differences in legal and regulatory systems, as well as institutional structures across countries. These disparities lead to uneven levels of adaptation and application of HUL principles. Moreover, legal and regulatory frameworks are often outdated or not adequately aligned with the holistic principles of the HUL approach, which considers both tangible and intangible heritage in dynamic urban environments.

In many contexts—particularly in Global South cities—public participation and community engagement, central to the HUL, challenge existing regulatory structures. At times, the approach is perceived as being imposed by international bodies, neglecting local specificities. Inconsistencies in heritage valuation—what is considered worth preserving and by whom—also pose a problem, as heritage discourse is frequently politicized and reframed according to the interests of local actors. Local communities may value certain places for their social or cultural meanings, even if these are not formally recognized as heritage by authorities. Without mechanisms for inclusive decision-making and stakeholder engagement, such discrepancies can erode trust and result in contested urban projects. The successful implementation of the HUL approach depends on locally embedded management frameworks and effective coordination between diverse actors, making adaptation to context and governance culture a key challenge for its broader application. While this study offers foundational insights and practical implications, future research is encouraged to explore the long-term socio-environmental impacts of heritage-led sustainable development and to critically examine how participatory mechanisms are shaped by power relations at international, national, and local levels.

While the HUL approach is designed to be inclusive and adaptive, it carries certain risks if implemented without careful planning and social safeguards. One of the most critical risks is heritage-led gentrification, where conservation efforts in historic neighborhoods attract investment and tourism but simultaneously drive up property values and living costs. This often results in the displacement of long-time, lower-income residents, leading to social exclusion and the erosion of community identity. In such cases, heritage conservation intended to honor local culture and history ironically becomes a force for cultural homogenization and economic inequality. This process, sometimes referred to as “aesthetic displacement,” alters the social fabric of neighborhoods, turning them into commercialized or sanitized versions of their past, primarily for consumption by wealthier outsiders or tourists.

Another danger lies in the potential misuse or politicization of heritage narratives. Heritage can be selectively interpreted or emphasized to support nationalistic, economic, or ideological agendas, marginalizing minority voices or alternative histories. This can lead to a narrow or distorted representation of urban identity and inhibit reconciliation in post-conflict or post-colonial settings. Furthermore, the complexity of managing HUL projects—which often involve overlapping interests from residents, private developers, heritage professionals, NGOs, and local governments—can result in bureaucratic gridlock or governance failures. Without strong institutional capacity and transparent decision-making structures, the implementation of HUL principles may stall or produce uneven results. There is also an environmental risk. In regions vulnerable to climate change or natural disasters, historic urban areas may lack the resilience measures necessary to withstand increasing threats, and retrofitting them for resilience can be technically and ethically complicated. If not addressed properly, these dangers can undermine the goals of sustainable and inclusive urban development that the HUL approach seeks to achieve.