Abstract

This paper investigates the cultural landscapes established by nineteenth-century German immigrants in South Australia and the southern Riverina of New South Wales, with particular attention to settlement patterns, architectural traditions and toponymic transformation. German immigration to Australia, though numerically modest compared to the Americas, significantly shaped local communities, especially due to religious cohesion among Lutheran migrants. These settlers established distinct, enduring rural enclaves characterized by linguistic, religious and architectural continuity. The paper examines three manifestations of these cultural landscapes. A rich toponymic landscape was created by imposing on natural landscape features and newly founded settlements the names of the communities from which the German settlers originated. It discusses the erosion of German toponyms under wartime nationalist pressures, the subsequent partial reinstatement and the implications for cultural memory. The study traces the second manifestation of a cultural landscapes in the form of nucleated villages such as Hahndorf, Bethanien and Lobethal, which often followed the Hufendorf or Straßendorf layout, integrating Silesian land-use principles into the Australian context. Intensification of land use through housing subdivisions in two communities as well as agricultural intensification through broad acre farming has led to the fragmentation (town) and obliteration (rural) of the uniquely German form of land use. The final focus is the material expression of cultural identity through architecture, particularly the use of traditional Fachwerk (half-timbered) construction and adaptations such as pug-and-pine walling suited to local materials and climate. The paper examines domestic forms, including the distinctive black kitchen, and highlights how environmental and functional adaptation reshaped German building traditions in the antipodes. Despite a conservation movement and despite considerable documentation research in the late twentieth century, the paper shows that most German rural structures remain unlisted and vulnerable. Heritage neglect, rural depopulation, economic rationalization, lack of commercial relevance and local government policy have accelerated the decline of many of these vernacular buildings. The study concludes by problematizing the sustainability of conserving German Australian rural heritage in the face of regulatory, economic and demographic pressures. With its layering of intangible (toponymic), structural (buildings) and land use (cadastral) features, the examination of the cultural landscape established by nineteenth-century German immigrants adds to the body of literature on immigrant communities, settler colonialism and landscape research.

1. Introduction

Immigrant communities the world over tend to be culturally conservative, maintaining their language, religious belief systems and general cultural traditions [1,2]. Among the latter are dress, artistic expressions, such as music and art, and skills and styles related to craft and manufacture but also agricultural practices and patterns of land use, as well as building styles. Unless forced upon the immigrants, assimilation with the host community occurs only slowly, usually lasting at least a full generation and often two—in particular, when the immigrants’ religious practices differ from the host community, as was the case with Lutheran Germans who are the focus of this paper. While language, religion and other intangible expressions of culture are essential elements of the cultural identity of the immigrants, and thus strongly adhered to, other traditions are more readily subject to adaptation to local social or environmental conditions. In consequence, these are more likely to disappear.

New cultural landscapes can be created where the immigrants are settler colonialists invading and occupying land owned by First Nations peoples, subsequently displacing them from their ancestral lands through violence of disease. These landscapes will manifest themselves in land use changes, the establishment of cadastral land subdivisions, and toponymic definitions as well as settlements and infrastructure. This will lead to a rich and dense tapestry or settler colonialist expressions with residual elements of the First Nations landscapes, usually surviving in those remnant spaces that settler colonialist deemed to be economically less important. The cultural landscape of immigrants who arrived in a space that has already been structured by settler colonialists will remain fragmented unless successive acquisition of property by immigrant families will create ghetto-like community.

This paper will examine the nature of Lutheran German immigrant communities in terms of their settlement pattern in South Australia where, at least in some areas, they were the first settler colonists on the ground. The paper will demonstrate the emergence of unique cultural landscape in Australia, focusing on toponymic landscapes and their erasure due to political pressures, as well as the nature and subsequent change of architectural traditions.

A considerable body of work exists on the history of the Lutheran German immigration to South Australia during the nineteenth-century, in particular, the peculiar circumstances of the initial settlements which gave rise to cohesive communities. A small body of work, mainly in the unpublished, gray literature, has been carried out on the land use patterns and architecture of these Lutheran German immigrants.

This paper will examine the cultural landscape left by the Lutheran German settlers in South Australia by layering an intangible cultural landscape represented by toponymic features over a visual cultural landscape manifested by cadastral features and land use patterns as well as structural remains in the form of vernacular architecture. The study not only speaks to manifestations of settler colonialism in general but also informs the body of literature on immigrant communities circumscribed by a common religion that is alien to the host community, as well as to general cultural landscape research.

Methodological Approach

While this paper is a deliberation and, therefore, does not follow the standard IMRAD (introduction, methodology, results and discussion) format of papers, some comments on the methodological approach are in order. The paper is a mixed-method study drawing on multiple lines of methodologically independent historical and contemporary evidence bases.

Toponymic data of communities and geographical features are derived from geographic names gazetteers and cadastral maps, with the renaming of these features during World War I (as well as subsequent revocation) evidenced in government documents. Nineteenth-century cadastral maps, as well as contemporary cadastral maps [3] and aerial photography (Google Maps, Apple maps), serve as datasets for the assessment of nineteenth-century settlement and agricultural land use patterns and their persistence to the present day. Historic lithographs, historic and modern photography and a field survey by the authors provide the data for the discussion of the features of past vernacular architecture and its survival to the present day.

A comparison of proportions calculator based as used to examine differences in toponymic nomenclature [4].

2. German Settlement in Australia

Between 1847 and 1910, about 4.14 million persons emigrated from Germany, mainly to the United States of America but also to Canada, South America and Australia. While in overall terms German immigration to Australia may be small in comparison to the Americas, it is highly significant at a national level as Germans constituted the largest non-English speaking faction of immigrants during the nineteenth century [5,6].

While much has been written of the presence of German settler communities in South Australia and southern New South Wales, often from the viewpoint of personal [7,8,9,10], local [11,12] and religious histories [13], it needs to be clearly stated that a very considerable number of German immigrants did not settle with these but remained in the capital cities or moved into rural areas, merging with and assimilating into the Anglo-Celtic settler colonialist society [13]. The critical factors for this were their religious affiliation and their professions. Professionals (doctors, etc.), as well as skilled trade people, made up the majority of immigrants [14], and miners found ready opportunities in urban communities [15,16,17], while unskilled laborers and agricultural workers settled in rural areas commensurate with the skill base [16,18]. In terms of religious drivers for choice of settlement, while Lutherans, and in particular Lutherans from the former German provinces of Silesia (now Śląsk, Poland), the Mark Brandenburg and Posen (now Poznań, Poland), formed cohesive religion-focused communities, Catholics and Lutherans from the western states of Germany readily merged with and assimilated into the other settler communities. As such then, while these immigrants had an influence on the social and scientific cultural landscape of South Australia [17,19,20,21,22,23], their dispersal into and assimilation with the wider Anglo-Celtic community meant that they, unlike the Lutheran Germans, did not result a tangible cultural landscape.

Small-scale, individual German immigration to South Australia has occurred since 1836 [24]. Following an invitation by George Fife Angas, the first major contingent of German settlers arrived in South Australia in 1837, establishing the community of Klemzig (now a suburb of Adelaide), with part of the second contingent Hahndorf in the Adelaide Hills [24,25,26,27]. The reasons for these immigrants to leave their home communities in Prussia was not only the well-publicized disagreement about the enforced standardization of the liturgy of the Lutheran Church [25,26,27,28] but also due to worsening economic conditions due to failing crops [15] and the ongoing economic depression in the textile industry of Silesia [29].

Whilst rights to religious freedom motivated the arrival of the first Lutheran German immigrants to Adelaide [5], deteriorating economic conditions, industrialization and a wish to avoid conscription were the most influential reasons for successive immigration to Australia [30]. Letters home as well as a plethora of German-language immigrant guides fueled chain migration to South Australia [16,25,31,32,33,34] but also to New South Wales and Victoria [35]. This is illustrated by the fact that most of the immigration occurred between 1855 and 1865, well after religious conditions had improved in Germany but when economic conditions were still poor [15]. Some German states, such as the Kingdom of Hannover, the Kingdom of Württemberg and the Grand Duchy of Baden, encouraged and even financed the emigration of impoverished rural people [36,37], with Hannover funding the emigration of over 1100 persons from the Harz region [38].

Despite the variety of reasons for immigration, the initial religious factor still has major significance for continued Lutheran chain migration to South Australia, where group immigration was favored due to the spiritual and moral strength that such groups provided in the new homeland. The fact that many of the initial settlers arrived in groups of similar social and regional origin [39]—rather than as individual families as was the case with German immigrants in New South Wales, for example—meant that cohesive clustered settlements developed. Subsequent chain migration could recruit into these settlements. This established and then maintained culturally and linguistically homogenous communities of Germans particularly in the rural areas of South Australia, which persisted well into the twentieth century. While selected recruitment into these settlements continued, the bulk of German immigrants arriving in the 1870s and 1880s settled in areas other than the established communities [15]—a fact that can be explained both by the then prevailing land prices but also by the fact that the regional origin of these ‘new’ immigrants was more diverse.

During the initial settlement period, extended families as well as members from the same source communities in Germany chose, where possible, land allotments next or close to each other to be able to work together and assist each other in farming activities [40,41]. The Lutheran religion, underpinned by its great faith in communal and family responsibility [42], resulted in the formation of compact nucleated settlements, particularly in rural areas [43], fostered by homogeny in language, religion, customs, occupation and socio-economic structure [44]. Such homogenous communities were alien to the British settler colonialist approach of settlement and thus often remained isolated from close social contact with English communities. As such, they preserved strong and rigid ties of the German language, German language schools and Lutheranism with sermons, hymnbooks and bibles in German [45,46,47].

As German immigrants had to change citizenship and become naturalized citizens of the Colony of South Australia in order to own land, almost half of the immigrants chose to do so within five years [39,40,48]. Irrespective of naturalization, endogamy prevailed among the early immigrants. During the period of 1842–1856, 89% of German immigrant men married women of German origin. Between 1863 and 1867, that figure was still 79% [40]. While the percentages dropped in subsequent years among the wider German immigrant community, Lutheran faith determined that endogamy remained high among the purely Lutheran communities—and this is despite the fact that the Lutheran church in Australia has split into several rival synods [15,27,49,50,51]. As a result of this cultural and spiritual cohesiveness, even second-generation Lutheran Germans in South Australia were seen to maintain distinctive social and cultural traits [39,43,50]. Among urban Germans on the other hand, exogamy occurred already among the first locally born generation, although formal cultural and political integration was slow [52].

While generally labeled ‘Germans’ by virtue of the country of origin, the many early German immigrants to South Australia, forming the settlements of Klemzig, Hahndorf and Lobethal, were actually Wends and Sorbs, a Slavic community from Lusatia (Lausitz) and Silesia (Schlesien) in eastern Germany. Others, by virtue of chain migration, formed loosely cohesive subcommunities, such as Schönborn and Neu-Mecklenburg populated by immigrants from Mecklenburg, Ebenezer by Wends from Saxony, Peter Hill by Wends from Prussia [53] and Bethel by Moravian Germans from Saxony [54].

From South Australia onwards, migration occurred to northwestern Victoria and to the Riverina Area in Southwestern New South Wales [55,56]. The literature available on the settlement pattern of Germans in the southern Riverina is largely limited to Jindera and Walla Walla, which were the arrival locations of the first highly publicized group treks from South Australia in 1867 and 1868 [57]. However German settlement in this region covered a much broader area, as evident from the scattering of Lutheran churches throughout the southern Riverina.

There the Lands Acts of 1861 fundamentally changed the land rules, which led to the opening up of new lands for settlers since they allowed selectors the right to obtain a Crown Grant for a ‘Home Maintenance Area’ of land without survey (‘conditional purchase’) in any Crown Land, leased or unleased. The purchase conditions imposed were that ‘living areas’ were to be between 40 and 320 acres in size (§13), that the selector had to pay AUD 1 per acre with a deposit of 5%, i.e., 25% of the purchase price (§13) upfront with the balance of the purchase price to be paid within three years (or deferred indefinitely by paying 5% interest per annum) (§18), that the selector had to reside on the block of land selected and that they could demonstrate ‘improvements of AUD 1 per acre minimum (§19)’ [58,59]. Such improvements commonly took the form of land clearing and fencing. When considering the large anomalies in prices, it is not difficult to see why the decision to relocate to New South Wales was made by expanding families in South Australia [1,60,61].

Communities in the southern Riverina, but especially in the Barossa Valley and the Adelaide Hills, while well assimilated into Australian society, have maintained some of their cultural identity and many of their traditions [62,63] as manifested in material culture [52,64,65], German-style cuisine [66,67,68,69,70], small goods and baked goods [52] and parts of their language [71,72,73]. Today, these also function as tourist attractions [62,74,75,76].

3. German Settlement Patterns in South Australia

While in many instances the German immigrants were the first settler colonialists on the ground, the land had already been expropriated from the Kaurna, Ngadjuri and Peramangk as traditional owners and custodians of the country. This expropriation, based on the, now nullified, British colonial doctrine of terra nullius, allowed for the partition of Indigenous Australian lands and subsequent acquisition by settler colonialists, who then could on-sell this land in toto or in parcels (but see Chalmers [77] for a discussion that Indigenous Australian land rights were recognized in the early days of the British colony of South Australia).

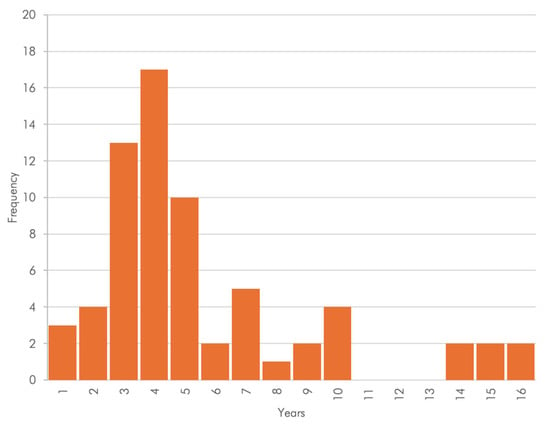

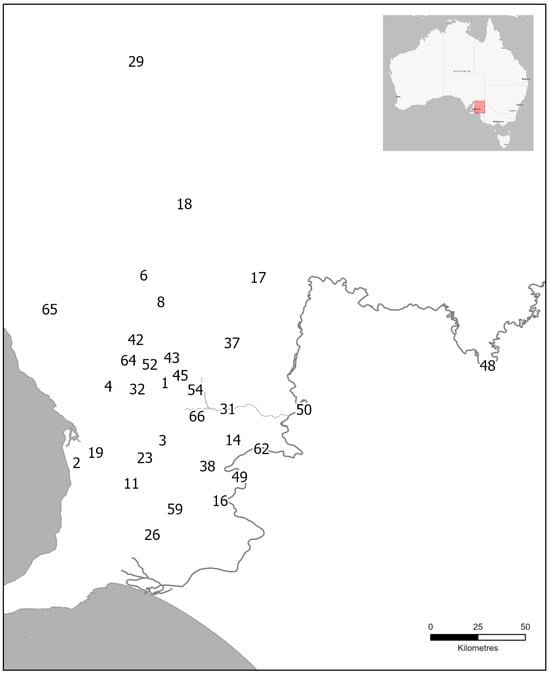

As noted, German settlement occurred from the mid 1830s onwards, with the majority of settlements (57.4%) being founded between 1845 and 1860 (Figure 1) with two major clusters of such settlements which commenced at a similar time. A northern cluster centered on the Barossa Valley and a southern cluster centered on the Adelaide Hills (Figure 2) [15]. Since both areas form major tourist attractions, these have seen some attention in the hospitality and tourism literature as cultural landscapes of wine and food in the tourism sphere [66,68,74,75]. With the exception of papers by Young [78] and Johnston [79] and an unpublished assessment by Heuzenroeder [80], however, little systematic work has been carried out on the non-consumptive nature of the cultural landscape generated by German immigrants in South Australia. The following section will examine the manifestations of that landscape: a toponymic landscape, a cadastral landscape and a landscape formed by German vernacular architecture.

Figure 1.

Frequency of the formation of German communities and settled places in South Australia.

3.1. A Toponymic Landscape

A considerable body of work has examined the impact of British settler colonialism on the toponymic landscape of Country cared for millennia by Indigenous Australian peoples as well as recent efforts to rectify these [81,82,83,84]. No detailed work has been carried out examining the German imprint on the toponymic landscape of South Australia with the exception of their renaming during World War II [13,85].

Where Germans were the first settler colonialists to alienate land, dispossessing the Kaurna, Ngadjuri and Peramangk as traditional owners of Country, they created a toponymic landscape that reflected their cultural upbringing. In this, the German settlers did not differ markedly from other settler colonialist communities [86,87,88]. The German toponyms of settled places were derived from religious sources (e.g., Bethanien and Lobethal), which make up 13.2% of all place names, from a person’s name (e.g., Hahndorf named after Captain Hahn), which make up 30.9% of all place names), and source communities in German homeland (e.g., Heidelberg and Klemzig), which make up 52.9% of all place names.

When considering the naming of the 53 German communities and settled places over time (Table A1 and Table A2), differences can be noted between the three key phases as derived from the distribution in Figure 1 (pre-1845, 1845–1860 and 1860–1914). During the early period of German settlement (pre-1845), religious-, personal- and source-community derived toponyms are evenly represented (28.6% each). During the heyday of settlement, in the period between 1854 and 1859, toponyms derived from the source communities dominated (60%), being very significantly more common than toponyms derived from personal names (22.5%, p = 0.0007) or with religious connotation (15.0%, p < 0.0001). In the final period (1860–1914), the proportion of toponyms with religious connotation decreased further (5.6%), while those derived from personal names (44.4%) and source communities (50.0%) were similar.

The German toponyms of geographic features and cadastral units (hundreds) differ from those associated with settlements (Table A3 and Table A4, Figure 3). Personal names dominate with 72.2%, which is very significantly greater than the proportion of names associated with settlements (p < 0.0001). German toponyms of geographic features associated with communities in German homeland (13.8%) are very significantly less than names associated with settlements (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Location of geographical features in the Adelaide Hills and the Barossa Valley carrying German toponyms prior to 1917. For details of numbered (letters) locations, see Table A3. Also shown are the Somme (formerly Rhine River North) and Marne Rivers (formerly Rhine River South). Map oriented north.

It should be noted, however, that not all German settlements carried German names. A number of sizeable Lutheran congregations formed in places that had already been given English toponyms, such as Light’s Pass (<1847) and Angas Park (<1847) [48].

For the first few years, early settler colonialists managed to establish cordial relationships with the owners of Country [89]. While this is not the place to discuss the role and nature of the early and later immigrant Lutheran pastors not only attending to their own flock but also missionizing the Indigenous Australian communities of South Australia (see [90,91,92,93,94,95,96]), it is worth noting several missionaries had learnt the language in the late 1830 and early 1840s and had become familiar with customs and country [90,97,98,99,100]. This then raises the question why Kaurna, Ngadjuri and Peramangk toponymy was not maintained when settlement locations were selected. Reading between the lines, it would appear that their enthusiasm was not necessarily shared by the other Lutheran pastors. It should to be noted that the Lutheran church in South Australia was notoriously fractious, resulting in two competing synods as early as 1846 and three synods by 1856 when a Victorian Synod splintered off [50,101].

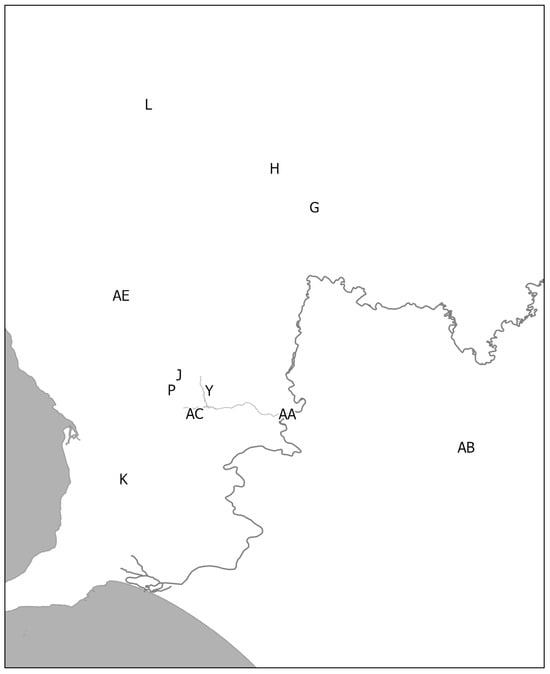

The practice of porting the names of the source communities to the new settlement spaces is a common trope among many settler colonialist societies, with German settlers practicing the same outside Australia as well [102]. German settlers imposing a range of toponyms derived from their source communities onto the South Australian landscape (Figure 4) can be seen through several lenses. Through the lens of settler colonialism, this can be interpreted as a deliberate act of colonization and domination of an inhabited, but perceived to be untamed, land. In this reading, it does not differ from the toponyms imposed by British, predominately English, settler colonialists [82,83,84]. Unlike the British pattern, however, which saw individuals relocating to and settling in rural and regional spaces in the post-convict era, German immigration entailed the physical and cultural translocation of entire extended families and small community groups [103].

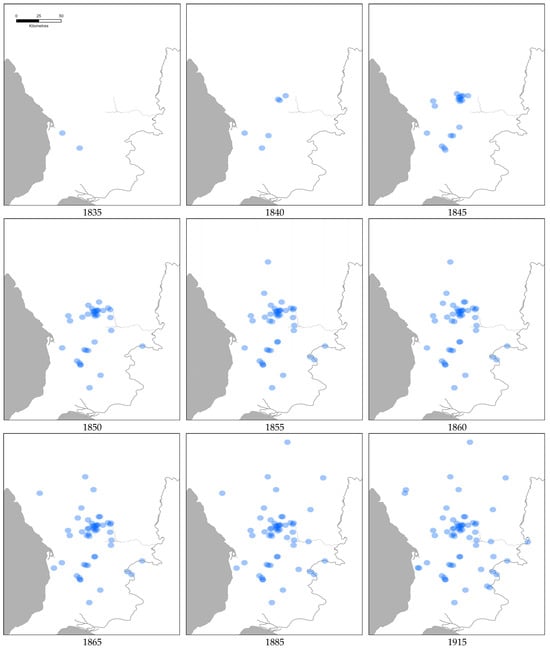

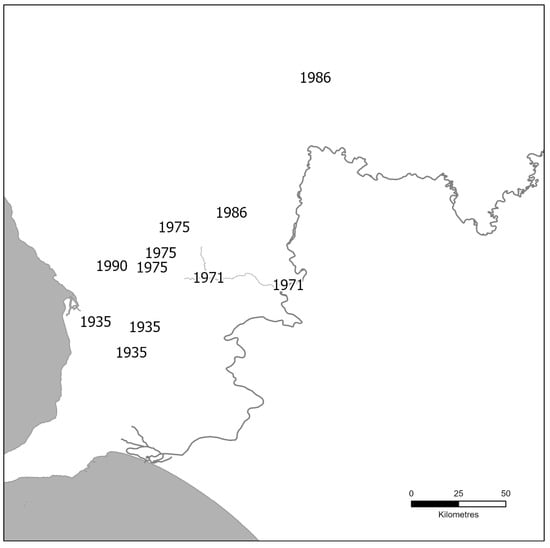

Figure 4.

Expansion of German communities and settled places, 1835–1915. The circles indicate a radius of 3 km around each community, indicating an area that can be easily reached within an hour’s walk. Maps oriented north.

This allows us to look at the toponymy through a different lens. While the Australian environment differed dramatically from the immigrants’ homeland, they recreated viable German communities with tangible expressions in land use patterns and architecture (see below) and with intangible expressions such as faith, customs and language. What could not be created ad hoc was the sense of and attachment to place, which required a passage of time. The layering landscape of the Barossa Valley and the Adelaide Hills with German toponyms, with their echoes of the home communities they had left, may have acted as a stand in. This also fits with the settlement intensification within Germany itself, where large tracts of uncleared forest were cleared for the establishment of Waldhufendörfer. There, the toponyms often again echoed the source communities but with the prefix of Neu (new). In the South Australian setting, but virtue of large-scale displacement, the ‘Neu’ was eschewed. The prefix was used when a new settlement was spawned in South Australia. A good example is Hoffnungsthal, which in 1847, against the advice of the Kaurna people, had been founded on the bed of an ephemeral lake [104]. When the lake flooded in 1853, the settlement had to be abandoned and reestablished as Neu Hoffnungsthal on higher ground in 1855 [105].During World War I, when Imperial Germany had become the enemy, German settlers were regarded by many as a possible fifth column and placed under surveillance for possible signs of disloyalty to Australia, with some community members interned [106,107,108]. In South Australia, like in other states, German toponyms were substituted by English appellations (Table A1 and Table A3). In total, 69 South Australian locations had to change their names [109,110,111], thereby effectively erasing the German presence from the broader toponymic landscape. Only minor, locally significant toponyms escaped the attention of the Nomenclature Committee. Following initial agitation in 1928, three German toponyms were reinstated in 1935 [85,112] with a number of others in the 1970s and 1980s [105] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Restoration of German toponyms 1935 to 1986. Map oriented north.

Not considered here is the lower-level toponymic landscape in the form of street names associated with local German settlers, which can range from 35% of all streets in Hahndorf to 60% of streets in Gomersal [63].

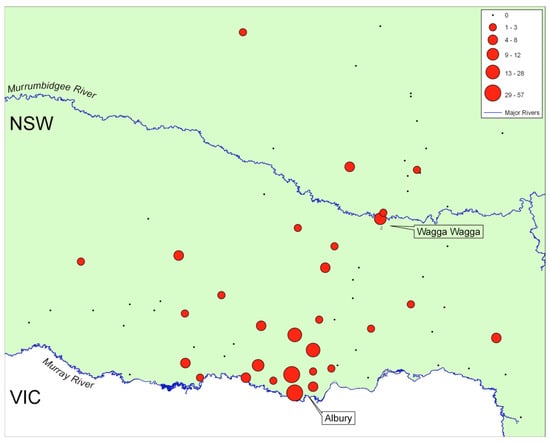

In the east, in New South Wales, British settler colonialists had established rural communities after they had systematically dispossessed the Wiradjuri peoples in the northern and southern Riverina following the [113,114]. By the time the German settlers arrived from South Australia in the 1860s [8,115,116,117] (Figure 6), the toponymic landscape had been firmly shaped by a combination of settler colonialists’ origins (e.g., Alma Park and Edgehill) and geographical landmarks (e.g., Pleasant Hills), as well as interpretations of Wiradjuri toponyms (e.g., Gerogery, Jindera, Temora and Walla Walla). The only renaming during World War I affected the community of Germanton, so named because it had formed around a public house owned by a German family at the crossing over Ten Mile Creek [10,118]. This was renamed to Holbrook in 1915 [119].

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of German land holdings in the Albury, Corowa, Hume, Urana and Wagga Wagga police districts in 1884 (source: [55]).

3.2. A Cadastral Landscape

Unless they are pastoralists establishing large stations for the grazing of cattle or sheep, settler colonialists will bring with them and apply the land use patterns of their homeland, with the spatial layout of settlement reflecting deeply ingrained traditions. Where German immigrant communities formed concentrated settlements, they espoused the traditional Reihendorf, a linear settlement where properties were aligned next to each other on one of two sides of a road as opposed to a Weiler (a scattered settlement), a Haufendorf (clumped irregular settlement), a Angerdorf (arranged around a Commons) or a Runddorf (arranged around a village square) [120,121,122]. Examples for this can be found in Lutheran communities in the United States of America [123,124,125], Canada [102], Brazil [126] and the Ukraine [102].

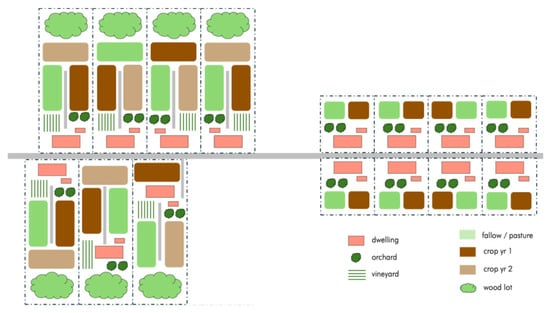

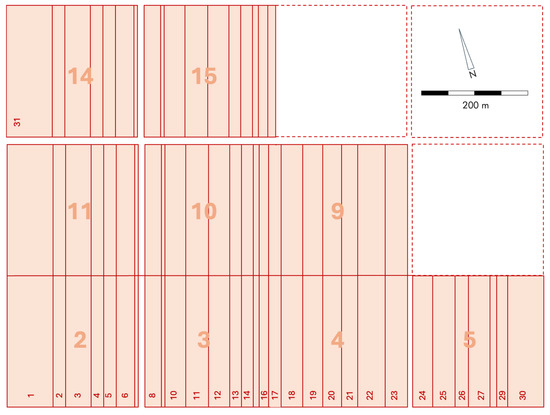

Not surprisingly, then, the German immigrants applied the settlement styles and agricultural practices that they were accustomed to in the source areas in Silesia, Posen and the Mark Brandenburg [127,128]. In South Australia, the key land use pattern employed by German immigrants was that of a Reihendorf. We need to consider two types, the Hufendorf and the Strassendorf, which are distinguished by the location of the arable land in relation to the homestead (see below) (Figure 7) [128,129]. Often, a Strassendorf was founded along a preexisting road or track with preexisting land parcellation, whereas a Hufendorf is commonly founded in an un-parcellated space, which allows the imposition of land use and habitation patterns.

Figure 7.

Schematic of a German-style settlements in Australia: Hufendorf (left) and Strassendorf (right).

The majority of the German communities in South Australia espoused the Hufendorf pattern, where agricultural properties were aligned along a road, usually on both sides unless one side was bounded by a creek, with the farmhouse located close to the road and the agricultural production zone stretching at the rear (Figure 7) [129]. Consequently, the land allotments were a series of extended rectangles with the narrow side along the road. A common design saw the homestead close to the road with outbuildings, such as a barn and pigsty, at the rear. The near-homestead area was used for a small-scale vegetable garden, a few fruit trees or a small orchard and some vines or a small vineyard [130].

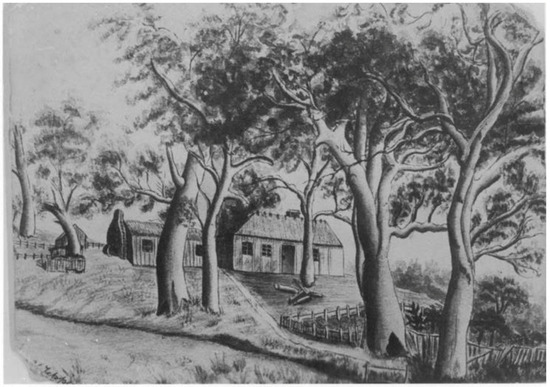

The families commonly kept a horse, a handful of cows and a few pigs (Table A5) [41,55]. The core of the agricultural production area was taken up by a field system with was managed in a three-year rotation of wheat, barley and fallow, which served as pasture. The far rear of the property served as a woodlot, either uncleared bush or planted up with pine and other timber (Figure 7 left). Depending on the topography, variations existed where the homestead was erected in the middle or towards the rear of the property (Figure 8). The Hufendorf was not a fixed entity but could, subject to the availability of land, be extended along the road at both ends. The village of Bethanien, as depicted in 1845, is a good example (Figure 9). As much of the land used by the early German settlers had to be cleared to be usable for agriculture, German geographers apply the term Waldhufenflur, which in the German homeland refers to a landscape, where the settlement comprises of strips of cleared land surrounded by uncleared forest [39,131].

Figure 8.

Plan of Hahndorf. The initial settlement of 1839 with houseblocks (pink) and parcellation for farmland (light green). Also shown are the creeks and the 2 m isolines (source: LocalWiki [132] with modifications by the author, basemap data: [3]). Map oriented north.

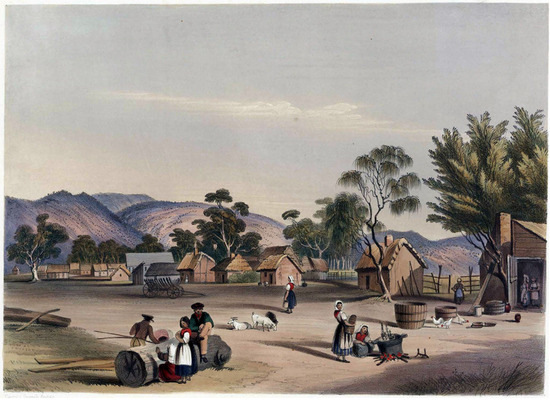

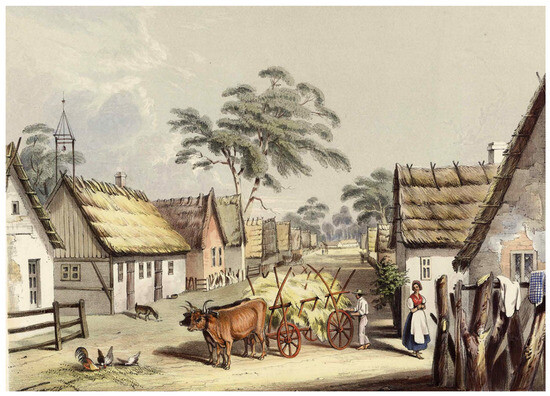

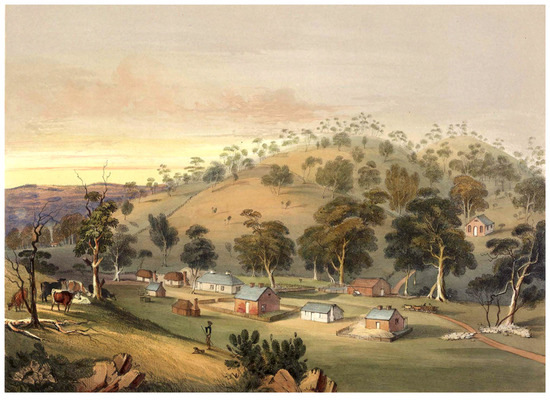

The other main type of German settlement is the Straßendorf, where the farm buildings are also arranged along a road, but where the farmland itself is located in the surrounding area. In the Straßendorf, the homestead is always very close to the road with outbuildings, such as a barn and pigsty, as well as a small-scale vegetable garden and a few fruit trees at the rear (Figure 7 right). Early examples for this are the German settlements of Klemzig (Figure 10) as well as German Pass (Angaston) (Figure 11), as depicted in 1845.

Much less frequently were German villages in South Australia arranged in a horse-shoe shape with properties facing an open space that was not a formal Commons but could be subdivided. The only village of that kind in South Australia was Hahndorf. The literature commonly describes Hahndorf as a Hufendorf, that in its later developments became a Strassendorf [133]. Upon closer inspection, however, Hahndorf in its early beginnings is a hybrid of a Strassendorf and a Runddorf. While the properties are arrayed in a horseshoe shape (Figure 8), they do not face each other as would be the case in a Runddorf, nor are they aligned in a linear array as a Strassendorf. The shape seems to have been defined by the available land (in sections 4002, 4003 and 4004 of the Hundred of Onkaparinga). All early land allotments are relatively small, between one and one and a half acres, which is too small to function as a viable economic unit in a Hufendorf. They were, essentially, houseblocks located on a flat alluvial land that was serviced by three creeks. The array of the houseblocks in a U-shape ensured that the fertile area enclosed by these houseblocks remained available for distribution as prime farmland. That land is not parcellated into short, narrow strips of land due to subdivision in the past 185 years but by design. Such narrow strips ensured a more equitable distribution of access to land with better water and soil than would have been the case with larger blocks. Some of these strips were extremely narrow and functioned as well-watered blocks with a low gradient and a soil of high quality. Some of these seed blocks are as narrow as 2 m. The slopes to the north and to the east, however, which were likewise parcellated, were less fertile, being covered with gravelly loam. Subsequent acquisition and subdivision of sections surrounding the initial settlement saw the creation of both Hufendorf-style larger strips of land in the southwest (south of the Main Street) and a continuation of the Strassendorf pattern to the east (Figure 8) [103,134].

The 54 founding families of 1839 could select a house block as well as several farm blocks [135]. In most cases, the farm blocks were not contiguous with the houseblock, but exceptions exist. Figure 12 exemplifies this well: the holdings of Gottlob Fliegert (green) and Friedrich Paech (red) are scattered at different elevation with small seed blocks. Gottlob Zilm (yellow) owned a houseblock with a contiguous farm block to the north, as well as seed blocks, while Andreas Philipp (blue) was blessed with a long contiguous strip of land that extended uphill on the opposite side of his houseblock. In addition, he held two seed blocks and another isolated piece of land.

German-owned farms essentially operated as subsistence agriculture. Grain, legumes and root crops (potatoes, etc.) were stored in barns and cellars. Vines produced grapes that could be transformed into wine but, importantly, also into vinegar (for pickling). Meat and fresh produce could be preserved through fermenting (e.g., Sauerkraut), pickling, drying, smoking and salting. Any surplus of grain or livestock (seasonally pigs), well beyond what was needed as a safeguard for the following year both as seed and for consumption, was sold for profit [52]. Any profits were reinvested in the farm by paying off the lease or in the acquisition of additional land. Being what amounted to a self-sustaining entity, coupled with a frugal lifestyle, ensured that most German farms in South Australia could be weather seasonal fluctuations and thus could be passed on intergenerationally, while British settlers, who soon converted to monoculture, were exposed to the boom-and-bust cycles of the Australian agricultural economy.

Figure 9.

The Hufendorf of Bethanien in 1846. Drawing by George Fife Angas [136].

Figure 10.

The Strassendorf of Klemzig in 1845. Drawing by George Fife Angus [136].

Figure 11.

The Strassendorf of German Pass (Angaston) in 1846. Drawing by George Fife Angas [136].

Figure 12.

Plan of Hahndorf 1839, illustrating the initial settlement of 1839 with houseblocks (pink), the distributed houseblock and farm blocks as illustrated by the holdings of Gottlob Fliegert (green), Friedrich Paech (red), Andreas Philipp (blue) and Gottlob Zilm (yellow). Also shown are the creeks and the 10 m isolines (basemap data: [3]). Map oriented north.

Statistical data for Bethanien for 1843, i.e., three years after the foundation of the settlement, show both the state of land clearing and the rapid establishment of farming (Table A5). They also well exemplify the nature of the three-filed system of German farming in South Australia. Of the 29 subsistence farmers, whose land holdings were enumerated, the average area under cultivation was 16.5 acres (range 3.5–39 acres). All grew wheat, and most of them also grew barley (93.1% of land holders) and peas (89.7%). Rye (10.3%) and oats (10.3%) were more rarely grown. All bar one of the subsistence farmers maintained a vegetable garden, usually of ½ acre size, which would have been used to grow potatoes and possibly turnips. In terms of combined acreage, 77.5% were under wheat, 13.7% under barley and 3.6% under peas, with 3.7% used for gardening. Considering the livestock herd, the majority of households kept cattle (89.7%) and pigs (86.2%), followed by goats (44.8%) and sheep (10.3%). Only one farmer owned a horse. In terms of the combined livestock herd, just under half were cattle (45.8%) followed by pigs (28.9%) and goats (22.9%). Sheep were uncommon (2.2%).

Following Hahndorf, the major German settlements of Lobethal and Bethanien were developed on a lease-to-purchase basis where the square 80 to 150 ha large sections of a hundred (the South Australian cadastral unit) were broken up into Hufendorf-type strips of land. Initially leased from GF Angas or from wealthy German settlers who could afford outright purchase [24], these leaseholds were gradually converted into freehold land owned by German families (Figure 13) [39]. Such land units were soon traded as some German settlers, who had commenced farming to sustain themselves, reverted to their original trades as soon as the economic conditions in the settlements warranted [137]. This is well evidenced by numerous advertisements in the Deutsche Post für Australien, a German-language newspaper published from 1848 in Adelaide, and the Südaustralische Zeitung, a German-language newspaper published from 1851 onwards in Tanunda (for German language press, see [138]).

Figure 13.

Hufendorf-type land division in Bethanien as it appeared in 1858 (after Erdmann [39]). Holdings: 1—C. Dohnt; 2—J.G. Nitschke; 3—F.C. Klingenbiel; 4—F.G. Hamdorf; 5—unknown; 6—J.A. Stelzer; 7—S.J. Laubsch; 8—S.J. Laubsch; 9—F. Topp; 10—S.J. Laubsch; 11—W.J. Klau; 12—Church and School; 13—C.F. Krause; 14—C. Pohlner; 15—I. Pohlner; 16—J.G. Schilg; 17—G. Kune; 18—C. Seidel; 19—E. Hippauf; 20—J.G. Hohnberg; 21—A.R. Gay; 22—E.W. Milich; 23—F.W. Gehlinng; 24—C.H. Thiele; 25—J.W. Gutschke; 26—J.W. Gutschke; 27—J.F. Sonntag; 28—K. Otto; 29—J.W. Gutschke; 30—G. Klaffuss; 31—C. Schilling.

When the first locally born generation was looking to establish itself on the land in the 1860s, land prices in South Australia in the ‘traditional’ settlement areas had increased considerably. Thus, some moved to new areas north and east of Barossa, where they selected larger blocks of land and eschewed the use of the Hufendorf pattern. Others moved to the Riverina in southern New South Wales where land had been opened up for selection in 1861. There, many settlers developed Hufendorf-style settlements, such as at Jindera, while others selected larger blocks [1]. At the time that the second locally born generation of German settlers was looking for land by the late 1880s and early 1890s, the land in the wheat-sheep belt of New South Wales had been fully parcellated. While still establishing close-neighbor land selection, the new German settlements retained, by necessity, the British layout of more equilateral blocks as well as the pattern of locating the homesteads near the center of the block or on elevated spots in that block (e.g., Alma Park [139,140,141,142]).

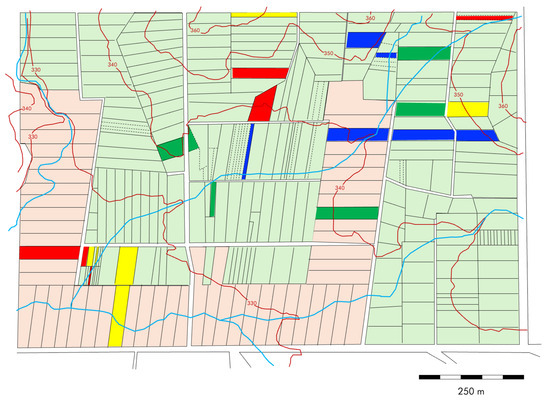

The Hufendorf land parcellation survived in some areas of South Australia, where some of the current-day property boundaries still reflect the original subdivisions. An example is Bethanien/Bethany in the Hundred of Moonoorro, where the 1850s pattern (Figure 13) is still well preserved in some the sections (Figure 14). In part, this is facilitated by the fact that much of the agricultural land use in the Barossa Valley is vineyards where such land sizes do not matter. This can be contrasted with the situation at Langmeil, which today forms part of the town of Tanunda. The original Hufendorf pattern (Figure 15A) has been largely obliterated by the urban infill development of Tanunda (Figure 15B). Only on closer inspection, and only with the knowledge of their existence, can some of the original property boundaries still be recognized.

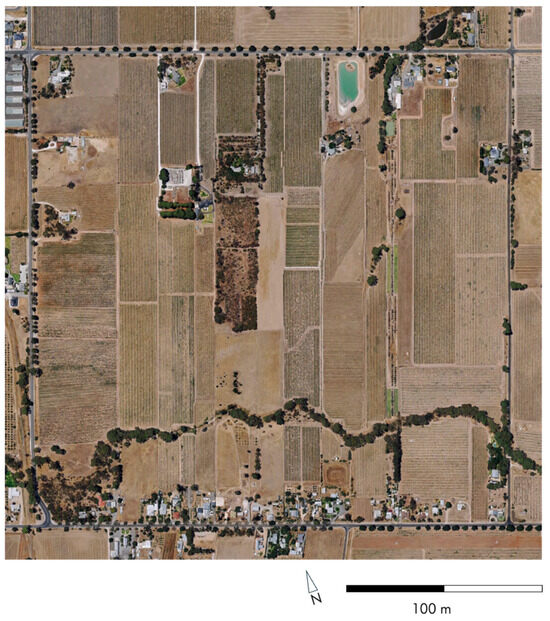

Figure 14.

Aerial image of section 3 of the Hundred of Moorooroo, South Australia. Note that much of the Hufendorf parcellation of land has survived to the present day. The size of the section is 4000 by 4000 feet (source: Apple Maps 2025).

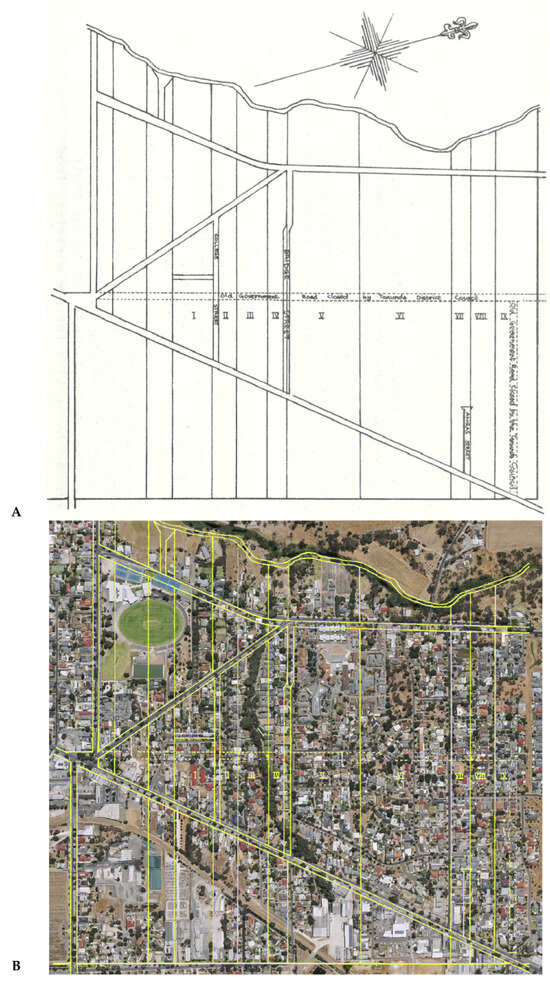

Figure 15.

Hufendorf-type land division in Langmeil (founded in 1846). (A) as it appeared in 1857 on a plan drawn by C. von Bertouch [143]. (B) Aerial image of present-day Tanunda (base photo Google Maps).

In those limited areas of New South Wales, the German settlements also used Hufendorf land parcellation, as exemplified by a section of the Parish of Jindera (Figure 16). That original parcellation, however, has now been obliterated by land aggregation over time and the subsequent conversion into broad acre farming (Figure 17).

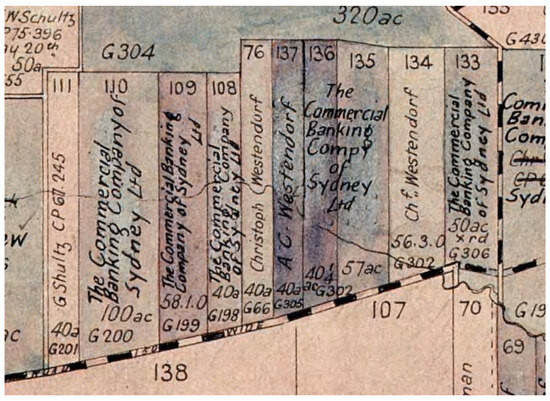

Figure 16.

Hufendorf-type land division along the Howlong to Jindera Road, NSW [144]. The map shows numerous hand annotations of ownership transfer to the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, demonstrating the extent of farm bankruptcies during the 1893–1895 depression [1].

Figure 17.

Aerial image of a section of the Howlong to Jindera Road, NSW. The image covers the same area as shown in Figure 16. Note the obliteration of the former land use pattern. Also note the remnant uncleared bushland in the north-western corner of the image (source: Apple Maps 2025).

4. German Rural Architecture

While there are numerous regional variations and environmental adaptations, a German farm typically consists of a farmhouse (‘Bauernhaus’), a barn (‘Scheune’) and a range of ancillary structures such as a smithy/work shed, a chook house and maybe a pigsty. It would also have a horticultural production garden and orchard nearby.

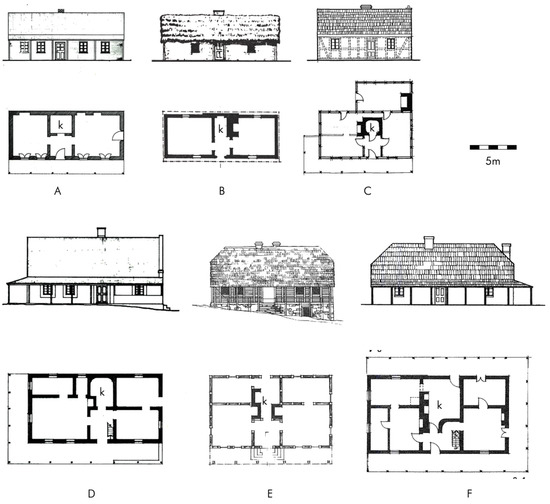

While German farm houses (‘Bauernhaus’) vary architecturally from region to region, there are some commonalities, especially most of northern and eastern Germany [145]. Generally speaking, the traditional German Bauernhaus of the larger farms is comprised of a two-story living section for the extended family, commonly taking up about one third of the floor space, a larger covered yard/hall section (‘Diele’) used for threshing and temporary storage and an animal section (‘Stall’) that allowed families to stable livestock and working animals during the winter months when they could not be kept, and fed, out in the paddocks [145]. Commonly the building has a high-pitched roof, which is often of the same height as the building. In Germany, the steep pitch prevents the build-up of snow, which could endanger the structural integrity of the roof, while the resulting cavernous roof space allows farmers to store large quantities of fodder (i.e., straw and hay) to feed the animals during the winter months. The design concept of housing people and livestock under the same roof, which goes back to the early Neolithic linear pottery culture [146,147], is highly energy efficient as the warmth of the animals contributes to the heating of the living quarters and the hay and straw stacked in the roof space acts as insulation.

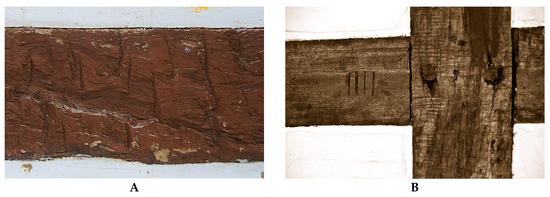

The size and height of the roof, as well as the weight of the fodder stored there, required a very strong wall construction. Setting aside buildings erected wholly from rubble masonry, the overwhelming majority of traditional German farmhouses are of a heavy, cross-braced platform-framed construction, exhibiting prominent compartments (‘Fachwerk’). A few examples exist, where the living quarters are erected in stone, while the animal section is comprised of Fachwerk. Most of the bracing is purely functional, designed to evenly distribute the weight of the roof and its contents. Only the street facade tended to show an ornamental pattern, often with additional cross bracing to achieve symmetry or, on occasion, with curved or otherwise ornamented braces. The individual posts, beams and braces were cut from single pieces of timber, trimmed to shape, numbered and stored (Figure 18) [148]. Once all required elements were completed, the frame of the structure could be assembled in a comparatively short time with the help of neighbors and extended family. All joints were scarfed or slotted, which allowed for the ready fitting of the completed timbers. Almost all fastening occurred with wooden pegs and dowels (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Examples of Fachwerk construction in the Australian setting. (A): adze marks on a beam on the external face of the building. (B): assembly mark (Roman numeral III) on the interior face of a beam (Australian Arms, Hahndorf, SA).

The compartments of the Fachwerk were commonly filled with wattle-and-daub, a fill of wickerwork that was filled and covered with loam, with each compartment then loam-rendered, leaving the wooden framing exposed (Figure 19). An alternative method, used in areas where willow saplings and shoots for wickerwork were not as readily accessible was to place wooden stakes into the compartment and fill the interstices with pug that was loam-rendered, again leaving the wooden framing exposed (‘Lehmstakenfachwerk’) (Figure 20). Wealthier home owners could afford to have the compartments filled with brick work (‘brick nogging’) (Figure 21).

Figure 19.

Fachwerk, showing the exposed wooden framing and wattle-and-daub compartments. Roberts Cottage & Mortuary, Hahndorf, SA (2009).

Figure 20.

Lehmstakenfachwerk. Internal compartment wall with wooden slats but pug infill instead of Lehmwickel, Gething’s Barn, Hahndorf, SA (2009).

Figure 21.

Fachwerk, showing brickwork-filled compartments. Paech House, Paechtown, SA (2009).

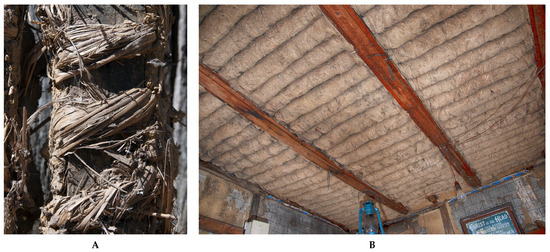

The roof was traditionally covered with reeds, straw or terracotta shingles. The internal and external wall compartments were filled with brick (northern Germany) or wattle and daub (central and southern Germany). The latter is either a lattice woven from thin twigs of willow or elm (‘wattle’), or a row of wooden slats, the interstices of which are filled and covered with a mixture of clay and chaff (‘daub’). The floor covering at ground level was either flagstones, brick or compacted soil, with floorboards used in some of the living quarters. The floors of the upper level and the roof space (where drawn in) were of wood. The ceilings of the living quarters comprised of Lehmwickel, loam-covered battens slotted between the floor joists (also known as ‘Dutch biscuits’). These battens, which had been wrapped with straw and covered with daub, were inserted side by side, with the interstices filled in and smoothed out, thus providing additional insulation (Figure 22). While in poorer households the Lehmwickel remained exposed, they were smoothed and painted over in more wealthy households (Figure 23).

Figure 22.

Lehmwickel. (A) Exposed straw of a decayed Lehmwickel, Roden’s Farm, Hahndorf (2009); (B) Lehmwickel ceiling, Buerger Residence, Penshurst, Vic (2009).

Figure 23.

Ceiling showing exposed floor joists, Paech House, Paechtown, SA (2009).

Traditionally, all German farmhouses have a single-or multiple-roomed, stone lined and sometime stone-paved cellar that was necessary for the cool storage of milk, dairy products and meat, as well as the dark storage of root crops (e.g., potatoes and turnips).

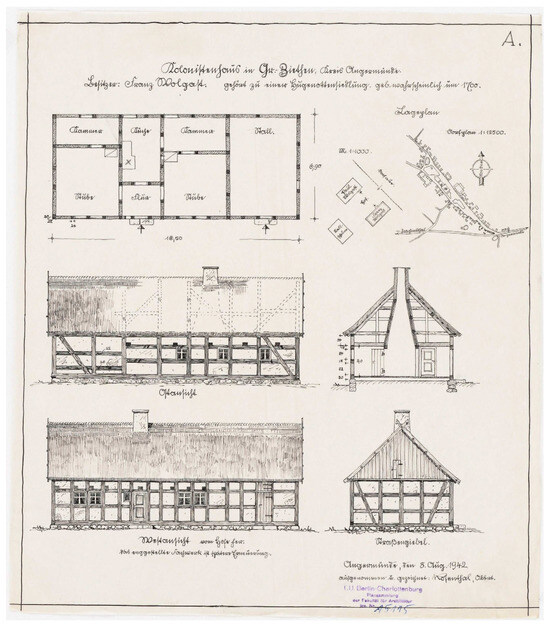

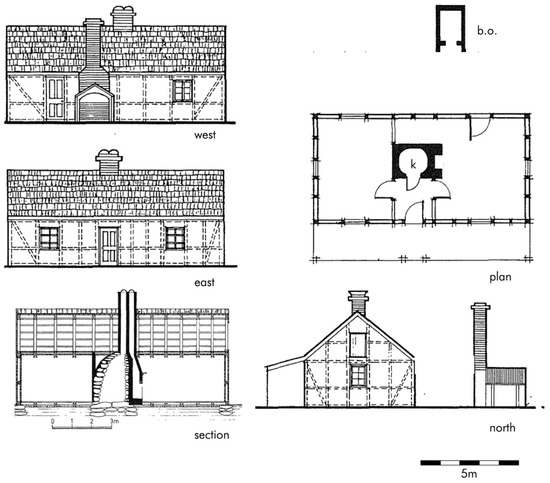

Where the livestock numbers were small, or where only small livestock, such as goats and pigs were kept, smaller single-story farmhouses could be built. These commonly exhibit a central hall section (‘Flur’) with stabling on one side and living quarters on the other. That design saw central hallway that connected to a back door and which contained one or more hearths for heating and cooking (‘Querflurhaus’). Variations exist, such as designs with an internal kitchen at the end of the hallway rather than another exit door, or designs where the internal stabling was eschewed in favor of additional living quarters. The high-pitched roof was used for fodder storage, dried fruit or flax, with some roofs containing a small, latticed compartment where small livestock, such as a nanny goat, could be kept there during winter (Figure 24). These designs were common in the less wealthy areas of Silesia and the Mark Brandenburg [149,150]. In the latter area, that building style then modified into a Kolonistenhaus (colonist’s home) (Figure 25)—a style was encouraged by royal decree as part of Prussian agricultural intensification in the late 1700s (‘Friderizianische Kolonisation’) [151,152].

Figure 24.

Latticed compartment in the roof space. Schirmer’s Cottage, Hahndorf, SA (2009).

Figure 25.

Drawing of a late eighteenth century Kolonistenhaus Groß-Ziethen, Brandenburg, Germany [153].

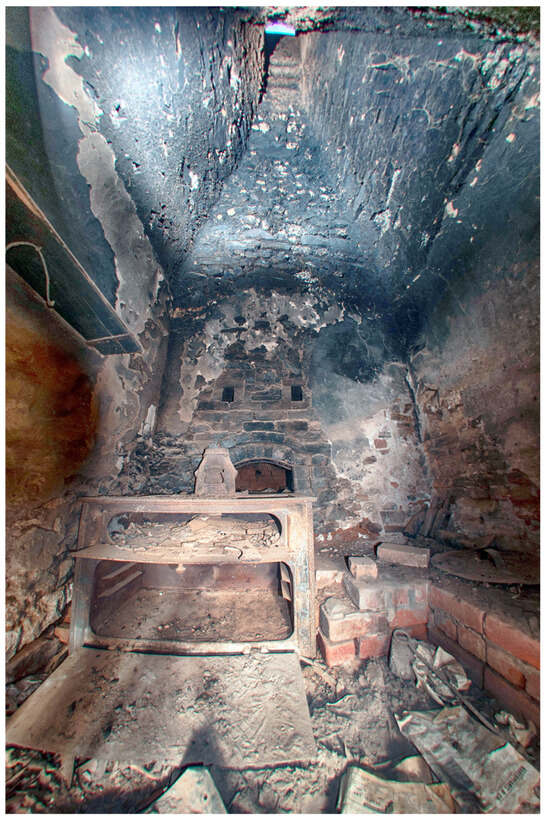

A design unique to Eastern Germany was the schwarze Küche (black kitchen, also known as Rauchküche), a window-less kitchen space with a low entrance from the main hallway. One of the major concerns of having an internal cooking space, where the fire would be kept up all day, was that a sudden downdraft in the chimney could spread hot embers throughout the kitchen, causing a building fire. The design of the black kitchen alleviated this risk primarily through the design of the ‘chimney,’ which encompassed the entire ceiling which funnel- or dome-shaped reached to the roof, terminating in a standard flue (‘Mantelschornstein’, Figure 26 and Figure 27). With this design, the force of any downdraft was dissipated by the time it reached the hearth itself. The hearth itself was set in a recess with a hutch that prevented sparks from escaping, while small flues directed the exhaust into the funnel-shaped ceiling. To further fire-proof the kitchen, the walls were made of field stone held together with mud mortar and rendered with a layer of loam, and the floor was covered with flag stones. The large exhaust space in the ceiling could also be used to air-dry fruit and to smoke meat and sausages.

Figure 26.

Interior of the Schwarze Küche, Doering Property, St Kitts, SA (2009). The soot-covered funnel-shaped ceiling, giving the space the name ‘black kitchen,’ is self-evident. Note the built-in hearth in the rear with the two exhaust holes. The vertical distortion of the image is caused by the use of an ultra-wide camera lens to capture the interior of a small space from floor to central chimney.

Figure 27.

Entrance to the Schwarze Küche, Doering Property, St Kitts, SA (2009). The open door at the far right of the image is the front door. The multi-colored door leads to the living quarters.

The barn served as an unheated storage structure for additional hay and straw, for food and seed grain, as well as for wagons and machinery. The barn was usually made of a lighter construction, unless the roof space was used for fodder storage. The other outbuildings could be of varied construction, ranging from Fachwerk to simple weatherboard or rubble stone construction [145].

5. Adaptation to Australian Climatic Conditions

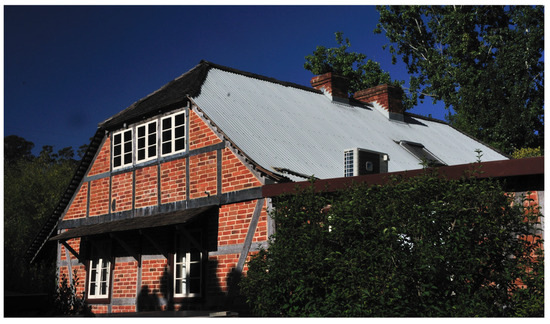

Many of the early German buildings in South Australia are of the classic German design of Silesia. While the majority of buildings that are shown in the street scene of Klemzig in 1845 are rendered, one of these shows structural Fachwerk (Figure 10). The examples discussed here are representative of the extant building stock, chosen by virtue of accessibility and ability to exemplify aspects of construction and decay. As such then, this is not a holistic study and assessment of all local example, such as those carried out in the 1970s and 1980s by the (now defunct) South Australian Centre for Settlement Studies [143,154,155,156,157,158].

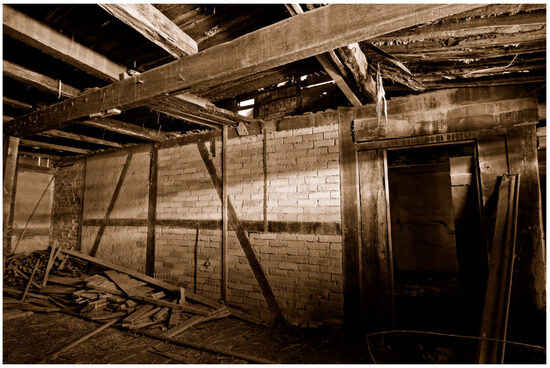

Extant structures in Hahndorf and environs, for example, are Schroeder’s (Mooney’s) barn (Figure 28), Roberts Cottage & Mortuary (Figure 19) and Gething’s barn (Figure 29), as well as the more elaborate Paech (Figure 21) and Jaensch residences, which show exposed structural Fachwerk. Schroeder’s barn, erected in the mid 1850s, is a standard Bauernhaus, with sections for humans and animals under a high roof (Figure 28). The building is of mixed construction, with the external shell of the human section and the western gable made from rubble stone, the internal structure and partitions of that section are made from Fachwerk with brick infill (Figure 30), while the animal section is made from Fachwerk with wattle and daub in-fill. Gething’s barn (Figure 29), by contrast, is a two-roomed barn with a high-pitched roof, strong compartment work and wall infills that resemble Lehmwickel but are Lehmstakenfachwerk (Figure 20).

Figure 28.

Schroeder’s Barn, Hahndorf, SA (2009).

Figure 29.

Gething’s Barn, Hahndorf, SA (2009).

Figure 30.

Interior of Schroeder’s Barn, Hahndorf, SA (2009). Shown is the wall separating the living single quarters from the stable. Note the brick infill of the compartments.

Very soon it became apparent to the German settlers that Australian climatic conditions were radically different from those prevalent in Germany. Primarily, the winters in Australia are nowhere near as severe as those in the homeland. This meant that livestock could be kept in the paddocks during all seasons and neither required stabling nor supplementary feeding of hay during the colder months. The implications for architecture were obvious. As livestock did not need to be stabled under the same roof, the farmhouses could be much smaller and limited to smaller specialist structures.

At the same time, the fact that fodder did not have to be stored in the roof space and the absence of snow loading—at least in the areas settled by German farmers in Australia—meant that roofs could be smaller and lower-pitched, leading to a lower weight of the roof structure. In consequence, the framing of the house did not need to be as heavily timbered and strongly braced either (Figure 31). The resulting savings in terms of the nature, size and quantity of timber parts, combined with the savings in labor in both cutting and trimming that timber, as well as the subsequent erection of the building, must not be underestimated.

Figure 31.

Otto Tepper’s pug-and-pine dwelling in Hoffnungsthal ca. 1849 [159].

The Prussian Kolonistenhaus design was eminently suited to the new circumstances. Not surprisingly, then, it was widely adopted. The most basic version was that of a two-roomed cottage with a central hallway that led to rooms on either side and opened into a black kitchen (Figure 32 and Figure 33A) with the living room unheated or heated (Figure 33A). The design was modular, which allowed one to add a room at the rear which benefitted from the heat radiating from the black kitchen (Figure 33C). Alternatively, the building floor plan could be doubled by adding a building at the sides and the rear (Figure 34 and Figure 35). The basic floor plan could be easily adapted to serve as a four-roomed cottage with black kitchen (Figure 33D) or a Flurküche (Figure 33E). Further expansion into a five-roomed unit could be easily achieved by scaling up the floor plan (Figure 33E).

Figure 32.

Fachwerk house with black kitchen, 135 Main Street, Lobethal (source: [158]).

Figure 33.

Elevations and ground plans of German Fachwerk houses in South Australia indicating the position of the kitchen (k). (A) Schwarz House, Bethany; (B) Handje House, Maranganga; (C) 24 Gumercha Road, Lobethal; (D) Keil House, Bethany; (E) House in Paechtown; (F) House on section 433 Hundred of Truro (sources: [143,157,158,160]).

Figure 34.

A German homestead in the Barossa Valley, ca. 1900. Note the Fachwerk building on the left has a stable-cum-Diele on the left and two rooms with a central corridor on the right. The building on the right appears to be a cottage that was extended at the rear (as evidenced by the double-ridged rood). Note the well in the right foreground (source: State Library of South Australia B-17017).

Figure 35.

Doering Property, St Kitts, SA (2009). The building in the center is the first pug-and-pine building on the site, containing the black kitchen. The property expanded with the building on the left and then the 1920 structure on the right.

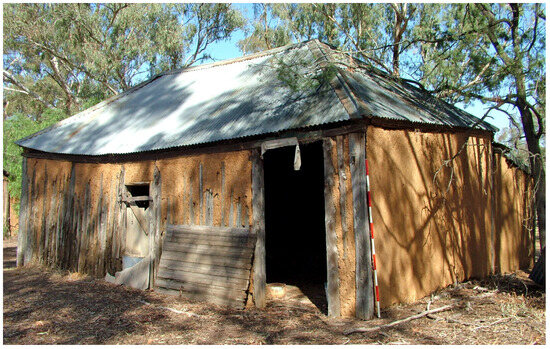

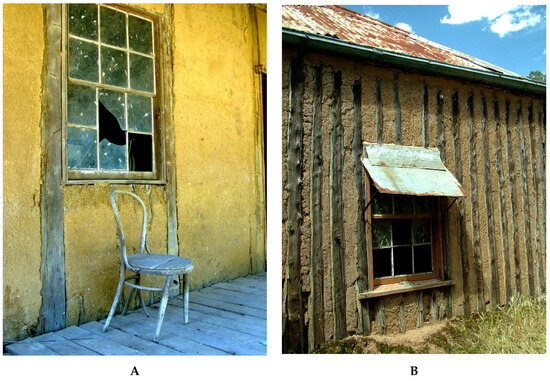

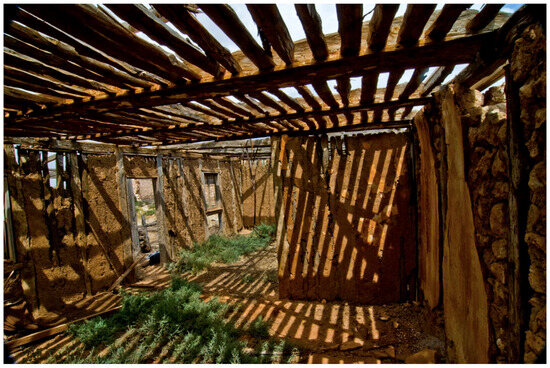

In essence, once the construction of double-story farmhouses was eschewed in favor of single-story cottages, these smaller buildings no longer required a framing with dense compartment work and strong cross-bracing. It was sufficient to merely set up heavy corner posts and a series of wall posts, the latter usually spaced at approximately ten-foot intervals. The posts were joined by a top plate onto which the cross beams were placed, adding lateral strength. This resulted in tall and widely spaced compartments without a base plate. As these compartments were considerably bigger than the traditional ones, the established method of using small twigs or Dutch biscuits could not be employed. The local adaptation was to extend on the concept of Dutch biscuits and to nail seven-foot stem sections of 10–15 cm thick saplings of Murray pine (Callitris sp.) to the top plate as well as the bottom sill acting in lieu of a proper base plate. These saplings were spaced as close together as possible, with the interstices, as well as their surfaces, pugged with the daub mixture (pug-and-pine, construction). To increase adhesion of the pug, the bark of the saplings was retained. The resulting wall could then be rendered (Figure 36 and Figure 37).

Figure 36.

Pug-and-pine building, Lieschke’s farm, Edgehill, NSW (2009).

Figure 37.

Examples of environmental decay of pug-and-pine walls. (A): well loam-rendered and yellow-washed external wall (Drew Property, Edgehill, NSW). (B): loss of protective loam-render exposing pine uprights and pug-fill of the interstices (Klemke Property, Edgehill, NSW).

This solution was a win–win for the German farmer selecting land, especially in New South Wales. There, a period of heavy pastoral grazing in the 1830s to 1850s, which saw extensive land clearing as well as widespread ringbarking of trees to improve the spread of pastures, coupled with changed fire regimes, favored the spread of Murray Pine (Callitris sp.) on sandy soils. By the mid 1860s and early 1870s, this pine regrowth had become a ‘menace’ [161], with stands locking up, resulting in stem diameters between 15 and 20 cm diameter [162,163].

To ensure productivity of the land, especially for grain production, farmers had to clear cut the saplings. These provided a ready source of raw material for the walls, while the local clayey soil, often quarried during the digging of a small farm dam, was mixed with chaff to provide the pugging materials. Larger pine trees were cut and split to provide the posts for the dwellings [164].

6. Effects of Management

During the 1970s and early 1980s, which were the heyday of heritage protection in Australia with a strong conservation and protection ethic [165,166,167], the (then) Australian Heritage Commission as well as the (then) Heritage Conservation Branch of the South Australian Government commissioned a number of heritage assessments. Assessed was the extant architecture in Bethany [168], Hahndorf [133,154], Light’s Pass [169], Lobethal [158,170] and Mount Pleasant [171] as well various locations throughout in the Barossa Valley [172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183].

Compared with the large number of identified properties, only a few of these are listed in the local and state heritage registers and thus protected from demolition, although environmental decay due to owner neglect is more difficult to prevent. An exception is Hahndorf, which was declared a state heritage area in 1988 and which has seen management attention [184,185,186].

When well maintained and rendered, these pug-and-pine buildings are difficult to identify. Only upon close inspection may tell-tale signs become apparent, such as thicker walls, or the exposed tops of earthen walls in the roof space. While a considerable number of these buildings are still in existence, they are threatened by environmental and anthropogenic forces. The major cause of decay are human agents, primarily due to changed expectations as well as detrimental council policies.

Setting aside the mansions of the wealthy, most nineteenth-century dwellings tended to be small structures with small and dark rooms. For reasons of fire protection, the kitchens were in separate buildings out in the back, as were laundry and toilet facilities [187]. While subsequent remodeling and renovation may have seen the integration of the kitchen and toilet into the main residential structure, this did little to change and improve on the nature of the living and bedrooms. Changed expectations of life style and residential comfort, concomitant with the availability of effective heating and cooling systems, saw the emergence of new house designs, especially a radically modified floorplan, an increase in the size of rooms and an increase in the size and number of windows [187].

In terms of the overall size of the building and the smallness and relative darkness of the rooms, the pug-and-pine dwellings are no different from nineteenth-century brick or weatherboard structures. They differ, however, in one crucial aspect: even under normal climatic conditions, the walls of these buildings will exhibit some minor contraction and expansion, leading to fissure cracks in the plaster and whitewash. In areas with reactive clay soils or where extreme summer temperatures predominate, these movements would be exacerbated. Consequently, very small amounts of plaster or whitewash will exfoliate both on the external and, more critically, on the internal surfaces. To prevent fine plaster dust in the rooms, the walls were often covered with Hessian, which conveniently also hid any of the cracks. These walls not only had an uneven appearance with rounded corners and cornices but did not allow for the ready fastening of pictures and other wall decorations (pers. obs. Lieschke Property, Edgehill, NSW). While families took these inconveniences as a given during the nineteenth century and put up with them during the early twentieth century, they no longer conformed with modern expectations of lifestyle and living comfort. It was inevitable that they would be replaced. Intergenerational change often forced the issue, with a wave of new buildings in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s.

The demand for residential accommodation in spatially constrained urban areas meant that many of the historic buildings were demolished and replaced by contemporary versions—unless they had been heritage listed which ensured retention, albeit with subsequent modification, commonly through additions at the rear. The demand for development space is much less in rural areas, however, which meant that many farmers built their new home adjacent to or near the original home and merely abandoned the old residence. A wave of such replacements occurred between the late 1970s and l980s. Today, only very few farmers still live in the original pug-and-pine dwellings.

Processes of Decay

Once abandoned, environmental decay sets in. Fortuitously, Callitris is a termite-resistant wood, which means that the primary causes of decay are those that impact on the earth component of the walling. Earth structures are very susceptible to the deleterious effects of moisture, primarily falling damp (once the roof is breached), penetrating damp (once the render has eroded) and rising damp (once the damp-proof course has been breached or bypassed). The decay principles of roofless soil structures are well understood and need not be repeated in depth [164,188,189]. Suffice to say thermal and moisture regimes in Australia are not uniform but subject to diurnal and seasonal fluctuations. Once exposed to moisture ingress, the clay packets in the soil of the walling will hydrate and swell followed by subsequent contraction during the drying (dehydration) phase. During dehydration, the clay particles may detach from non-pliable surfaces such as the internal stakes in Fachwerk or the vertical uprights in the pug-and-pine structures, creating fissures and gaps, which facilitate further moisture ingress (Figure 38). Extensive hydration will cause disaggregation, causing clay platelets to separate and become susceptible to minor physical impact. Thus, rain drops or rain splash from hard surfaces will cause the platelets to be dislodged and washed away, leading to surface erosion of walling. The decay accelerates once the external protection (roof and render) has been impaired or lost.

Figure 38.

Wall structure of a pug-and-pine building, showing the structural, roughly hewn post, the walling made of pine saplings with their bark attached and the pugging with chaff as temper material. Note the cracking due to repeated hydration and rehydration events. Klemke Property, Edgehill, NSW (2009).

Good examples for this kind of decay are structures on those farm properties where the original residence is no longer needed for habitation or storage and the pug-and-pine building has been abandoned and the roof has been damaged, lost or removed. Decay of wall surfaces does not progress uniform but will first impact the ceiling and then disproportionately affect those façades that are exposed to prevailing moisture while also being shielded from sunlight and thus from drying effects (southern walls). A good example for this is the Schulz Property where the Lehmwickel ceiling has decayed, but some of the walls are still extant (Figure 39).

Figure 39.

Decay of a deroofed pug-and-pine building. Note the stakes of the fully decayed Lehmwickel ceiling, while some of the vertical walls are still extant Schulz Property, Cambrai, SA (2009).

Ongoing decay of the walling will expose and then isolate the structural timbers as walling made of pine saplings leaving a wooden skeleton (Figure 40 and Figure 41). Photodegradation of the timbers (Figure 40) will lead to structural collapse, with remnants of stone-built chimneys and black kitchens the only reminder.

Figure 40.

Decay of a deroofed pug-and-pine building. Note the stone walling of the former black kitchen, as well a small remnant section of the pug–and–pine wall at right. Original owners unclear; Steinfeld, SA (2009).

Figure 41.

Decay of a deroofed pug-and-pine building. Part of the chimney can be seen in the right background. Krischel property, Steinfeld, SA (2009).

7. Is There a Future for These Structures?

Much of the heritage conservation effort has been focused on the village communities rather than the rural areas. Hahndorf, for example, was declared a state heritage conservation area in 1988, and heritage standards were developed for that area [185]. Other properties, such as those in Bethany, Lights Pass and Lobethal, are occupied residences that are being maintained (albeit with alterations). The majority of farm buildings that make up the tangible evidence of German settlement in South Australia are not listed on the local, let alone the State heritage register and thus have no protection from alteration or neglect.

What future, if any, do these abandoned buildings have? In urban areas where the buildings are used as residences, it is possible to ensure adequate maintenance and conservation through owner-education, possibly augmented through financial incentives (e.g., [190,191]), or to find appropriate adaptive reuse options for most buildings, even for seemingly single-use properties such as churches [192]. These opportunities are only rarely applicable in the case of isolated buildings on private farms in rural settings. While such buildings can be heritage listed, the reality is that the maintenance of such unwanted structures represents a considerable burden and financial impost on the owner. Moreover, rural local governments tend to have a smaller rate base than metropolitan councils and thus have smaller budgets, yet by nature of their spatial size, they tend to have higher demands on the maintenance of road and other community infrastructure. In consequence, rural councils do not tend to offer the financial heritage incentives that metropolitan councils can provide [193]. While community-led initiatives or development-integrated conservation are options in urban areas and clustered settlements, they are not feasible in dispersed locations, unless the surrounding land is used for viticulture and thus has a ready client base of tourists.

Consequently, most of the abandoned buildings in rural areas are rapidly falling into a state of benevolent neglect and decay. Ever since the collapse of HIH as a major insurer in 2001, however, public liability issues have come to the forefront of local government policy [194]. It is no longer possible to allow buildings to graciously slide into a state of decay and ruin. Derelict buildings, once structurally unsound, are deemed to pose a risk to the public and, therefore, are condemned and commonly ordered to be demolished. Thus, the days of most German pug-and-pine buildings seem to be numbered.

On occasion, forces beyond mere disuse and neglect conspire to destroy this heritage. Rural Australia has experienced an economic and social decline, with the population of many communities shrinking. The days of the small family farm are essentially over, with many small acreage farmers working another job. Few younger families wish to continue farming and instead prefer to live and work in regional centers. To remain viable, modern agricultural production requires larger properties, which has led to the acquisition, or lease, of smaller properties. It is the homesteads of these properties that have been abandoned once the families move into town.

Perversely, several rural councils, in South Australia, for example, actively penalize owners who wish to maintain, or at least retain, their historic buildings. These councils define ratable dwellings as those that can be lived in, as opposed to those that are actively inhabited. It is hardly surprising that farmers have little desire to pay rates on structures that are superfluous to their needs. The easiest unequivocal way to demonstrate that a dwelling is no longer inhabitable is to take off its roof—with the added benefit of salvaging the roofing iron for future use or scrap metal sale.

In consequence, there are many former German pug-and-pine dwellings in South Australia that are reduced to the mere skeletons of their walling. Their future is bleak.

8. Conclusions

The early German immigrants to South Australia, many of whom arrived as cohesive religious and regional communities, established distinct settlements with their own toponymic and spatial identities. These communities transplanted not only agricultural land use practices and architectural forms but also intangible cultural elements, such as language, faith, and social structure. Their approach to land use, particularly the widespread adoption of the Hufendorf and Strassendorf models, left enduring marks on the physical geography of South Australia and, later, in some parts of New South Wales. While the German toponymic landscape was largely erased during World War I due to xenophobic sentiment, many of the physical manifestations, in the form of parcels of land and architectural footprints, survived well into the twentieth century.

A central theme throughout the investigation is the dialectic between persistence and adaptation. The settlers maintained strong cultural cohesion, especially in the first and second generations, supported by communal religious institutions and shared social values. However, they also responded pragmatically to the radically different environmental conditions of the Australian continent. Climatic realities such as mild winters, the absence of snow loads and different building materials led to the evolution of German building forms, most notably in the adaptation of Fachwerk construction and the development of the pug-and-pine technique, which integrated German building traditions with local material availability.

Yet, these once-cohesive landscapes are now increasingly fragmented. Urban expansion, agricultural intensification and changing social values have diminished the visibility and significance of these early settlements. The very factors that once ensured their sustainability, self-reliance, communal labor and intergenerational transfer have been undermined by rural depopulation, modern housing expectations and the economic pressures of contemporary farming. Many of the remaining vernacular buildings face environmental degradation, which is compounded by a lack of heritage incentives to preserve isolated and now-obsolete farm buildings.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data to report.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was written and accepted as a contribution to a projected Festschrift volume for Sabine Sauer, town archaeologist (Stadtarchäologin) of Neuss (North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Since that volume (‘Keller, Kloester und Kataster’) never eventuated, the original contribution, which focused solely on the architecture, was considerably expanded into the present paper. I am indebted to Deanna Duffy (Spatial Analysis Unit, Charles Sturt Universoty) for the maps reproduced as Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

German toponyms of German communities in South Australia renamed in 1917. For location, see Figure 2. Abbreviations: GT—toponym derived from geographical features; HT—toponym derived from a community in Germany; PT—toponym derived from a person’s name; RT—toponym with religious connotation [85,105,111].

Table A1.

German toponyms of German communities in South Australia renamed in 1917. For location, see Figure 2. Abbreviations: GT—toponym derived from geographical features; HT—toponym derived from a community in Germany; PT—toponym derived from a person’s name; RT—toponym with religious connotation [85,105,111].

| No. | German Name | Meaning | Type | Founded | Village Type | Substitution | Reverted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bethanien | Bethany | RT | 1841 | Hufendorf | Bethany | |

| 2 | Bismarck | German chancellor | PT | 1903 | Weeroopa <1> | ||

| 3 | Blumberg | town in Lower Silesia | HT | 1848 | Birdwood <2> | ||

| 4 | Blumenthal | town in Silesia | HT | 1848 | Hufendorf | Lakkari | |

| 5 | Buchsfelde | Buch’s field | PT | 1848 | Loos | 1990 | |

| 6 | Carlsruhe (1) | town in Baden | HT | 1857 | Kunden | ||

| 7 | Friedrichstadt | town in Upper Silesia | HT | 1847 | Tangari | ||

| 8 | Friedrichswalde | town in Brandenburg | HT | 1867 | Tarnma | ||

| 9 | Grünberg | town in Silesia | HT | 1853 | Hufendorf | Karalta | 1975 |

| 10 | Grünthal (2) | town in Silesia | HT | 1847 | Verdun | ||

| 11 | Hahndorf | Hahn’s village | PT | 1838 | Hufendorf | Ambleside | 1935 |

| 12 | Heidelberg | town in Baden | HT | 1865 | Kobandilla | ||

| 13 | Herrgott Springs | personal name | PT | 1859 | cluster | Marree | 1979 |

| 14 | Hildesheim | town in Germany | HT | 1891 | Punthari | ||

| 15 | Hoffnungsthal | town in Silesia | HT | 1847–1853 | Hufendorf | Karrawirra | 1975 |

| 16 | Jaenschtown * (3) | personal name | PT | 1909 | Kerkanya | ||

| 17 | Kirchauff | politician | PT | 1884 | Beatty | ||

| 18 | Klaebes | personal name | PT | 1879 | Kilto | ||

| 19 | Klemzig | town in Silesia | HT | 1838 | Strassendorf | Gaza | 1935 |

| 20 | Kronsdorf | crown village | HT | 1847 | Kabminye | 1975 | |

| 21 | Langdorf | town in Silesia | HT | ~1845 | Kaldukee | ||

| 22 | Langmeil | town in Brandenburg. | HT | 1846 | Bilkyara | 1975 | |

| 23 | Lobethal | valley of praise | RT | 1841 | Hufendorf | Tweedvale | 1935 |

| 24 | Neudorf | town in Lower Silesia | HT | 1852 | Mamburdi | 1986 | |

| 25 | Neukirch | town in Silesia | HT | 1860 | Dimchurch | 1975 | |

| 26 | Neu Hamburg | town in Germany | HT | 1850 | Willyaroo | ||

| 27 | Neu Mecklenburg | province in Germany | HT | <1866 | Gomersal | ||

| 28 | Oliventhal | town in Bohemia | RT | <1848 | Olivedale | ||

| 29 | Petersberg (4) | town in Silesia | PT | 1876 | Peterborough | ||

| 30 | Rhine Park | river in Germany | HT | 1857 | Kongolia | ||

| 31 | Rhine Villa | river in Germany | HT | 1880 | Cambrai | ||

| 32 | Rosenthal | town in Silesia | HT | 1850 | Rosedale | ||

| 33 | Schoenthal | town in Lower Silesia | HT | 1847 | Hufendorf | Boongala | |

| 34 | Schreiberhau (5) | town in Lower Silesia | HT | ~1849 | Warre | 1975 | |

| 35 | Seppelts | personal name | PT | 1851 | Dorrien | ||

| 36 | Siegersdorf | town in Silesia | HT | 1849 | Bultawilta | 1975 | |

| 37 | Steinfeld | town in the Rhineland | HT | 1882 | Stonefield | 1986 | |

| 38 | Summerfeldt | summer field | GT | 1881 | Summerfield | ||

| 39 | Vogelsang’s Corner | personal name | PT | 1911 | Teerkoore | 1986 |

Notes: <1> became Brooklyn Park in 1944; <2> Initially meant to be Worltatti [111]; Spelling variations (1) Karlsruhe; (2) Grunthal; (3) Jaenschton; (4) Petersburg; (5) Schreiberau/Schrieberau.

Table A2.

German toponyms of informal German communities in South Australia. For location, see Figure 2. Abbreviations. GT—toponym derived from geographical features; HT—toponym derived from a community in Germany; PT—toponym derived from a person’s name; RT—toponym with religious connotation [105,111].

Table A2.

German toponyms of informal German communities in South Australia. For location, see Figure 2. Abbreviations. GT—toponym derived from geographical features; HT—toponym derived from a community in Germany; PT—toponym derived from a person’s name; RT—toponym with religious connotation [105,111].

| No. | German Name | Meaning | Type | Founded | Village Type | Substitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Altona | town in Hamburg | HT | 1866 | subdivision | — |

| 41 | Altona | town in Hamburg | HT | 1911 | subdivision | — |

| 42 | Bethel | biblical name | RT | 1855 | — | |

| 43 | Ebenezer | stone of help | RT | 1852 | — | |

| 44 | German Flat | generic | gen | 1851 | — | |

| 45 | German Pass | generic | gen | 1842 | Angaston | |