How Campus Landscapes Influence Mental Well-Being Through Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Insights from SEM and Explainable Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypothetical Framework

2.1. Mechanisms by Which Landscape Perception Influences Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance

2.2. Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Dual Dimensions of Emotional Belonging

2.3. The Influence of Perceived Social Acceptance on School Belonging and Psychological Well-Being

2.4. School Belonging and Psychological Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

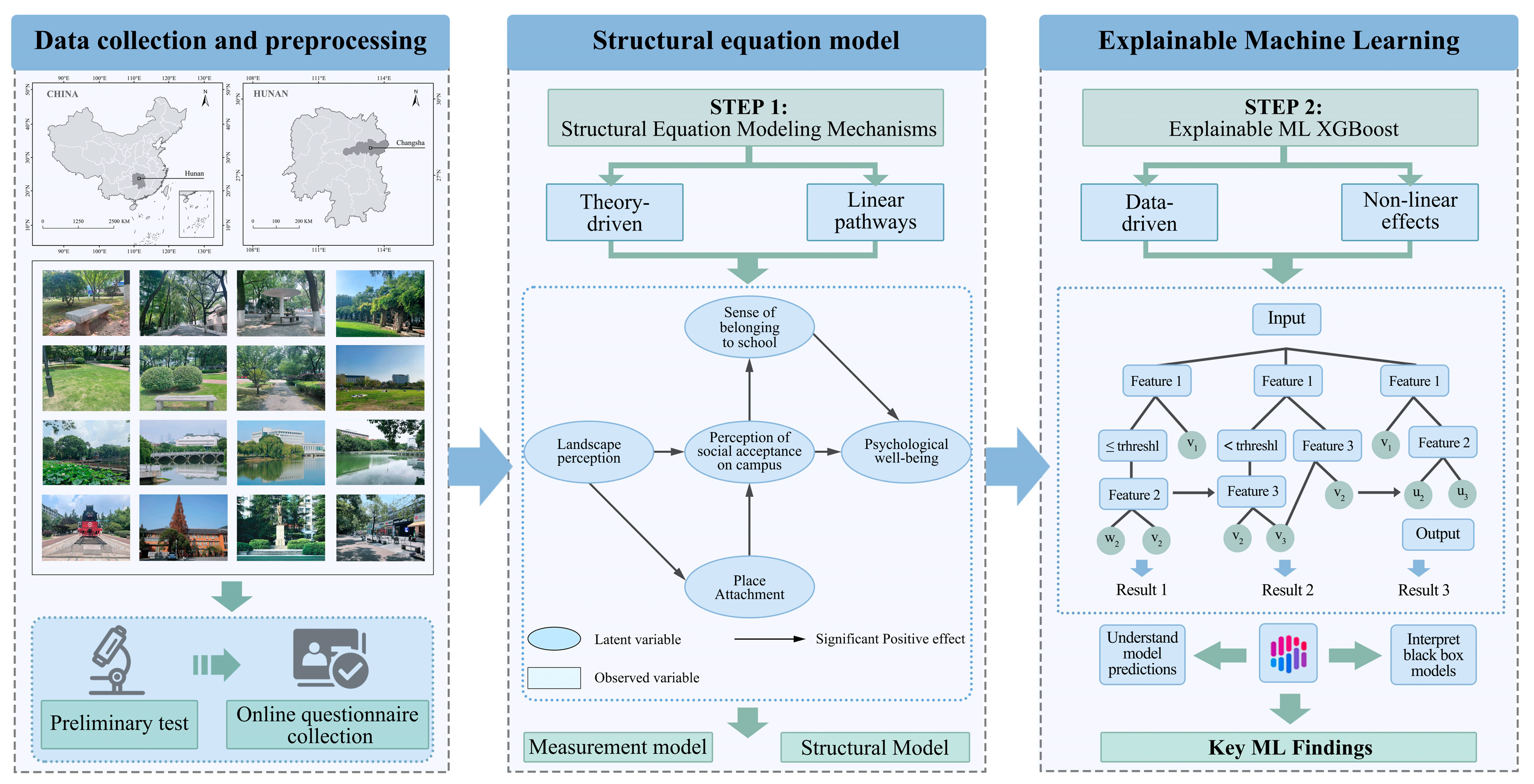

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Data Collection and Variable Construction

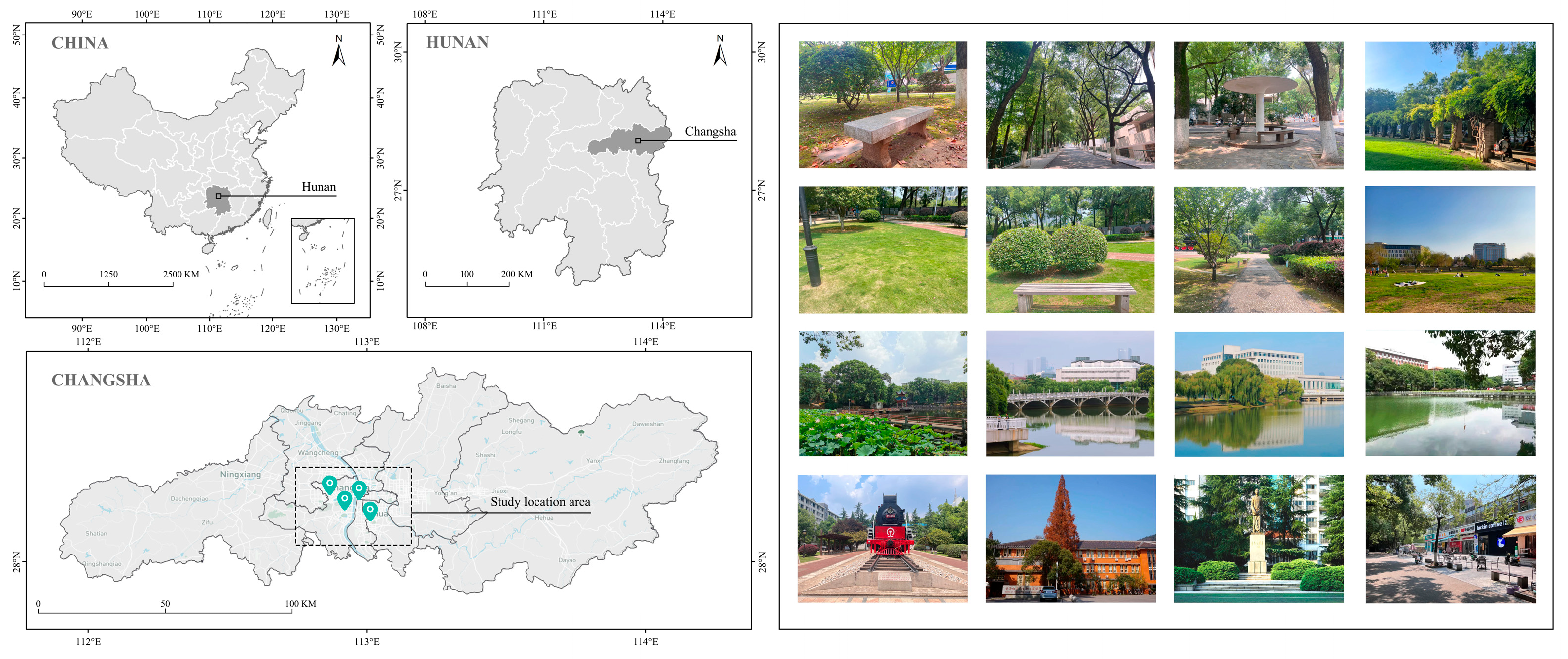

3.2.1. Site Selection

3.2.2. Questionnaire Design

- (1)

- Basic demographic information, including gender, age, educational level, field of study, monthly expenditure, and Body Mass Index (BMI);

- (2)

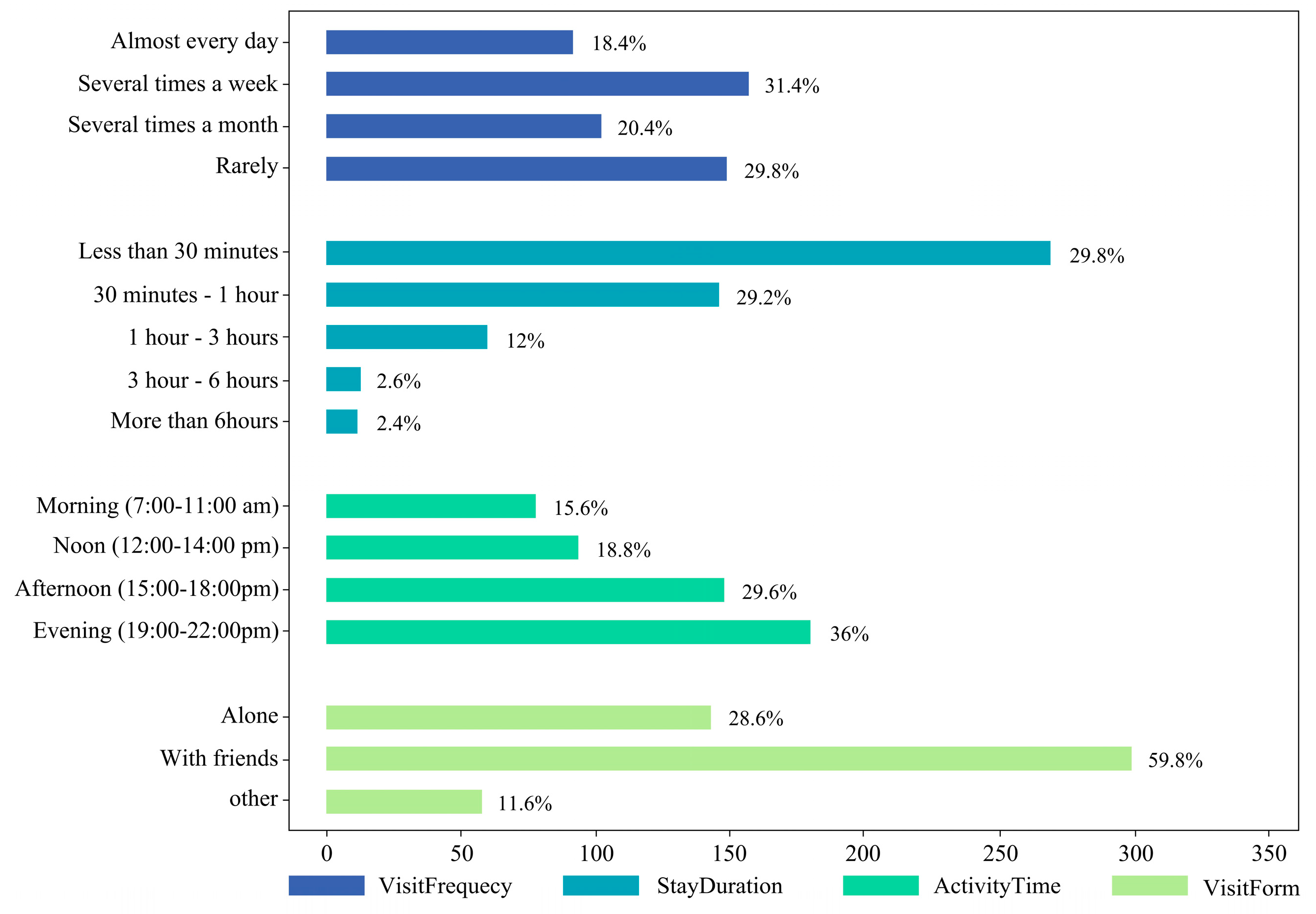

- Campus green space usage behavior, including the visit frequency, duration of stay, time of day, and usage patterns;

- (3)

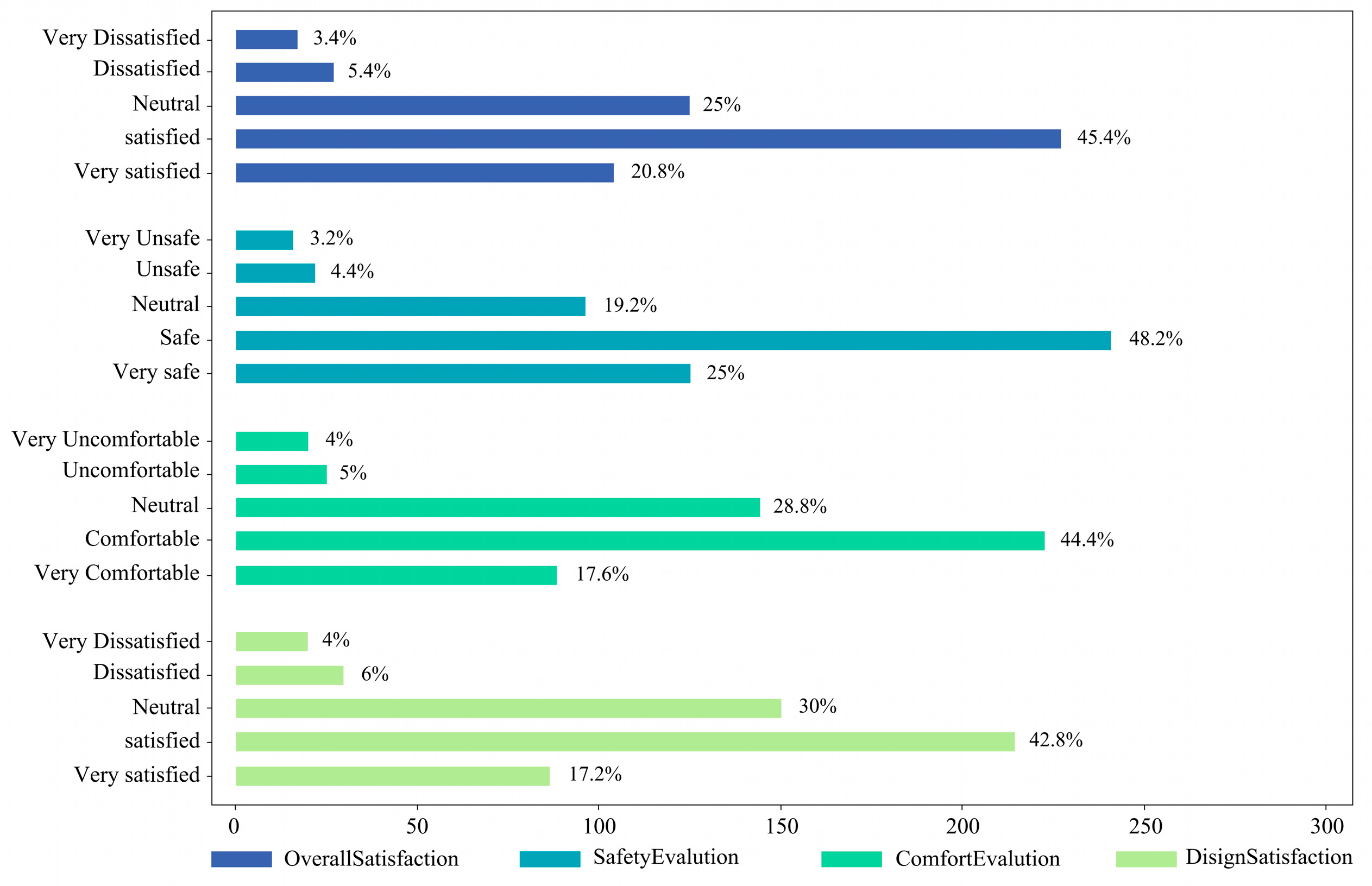

- Evaluation of campus landscape spaces, including perceived adequacy of spatial design, comfort, safety, and overall satisfaction;

- (4)

- Standardized scales for core variables, adapted from validated instruments and modified to fit the current research context. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

3.3. Research Methodology

3.3.1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

3.3.2. XGBoost-SHAP

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample Population

4.2. Results of the Structural Equation Model

4.2.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

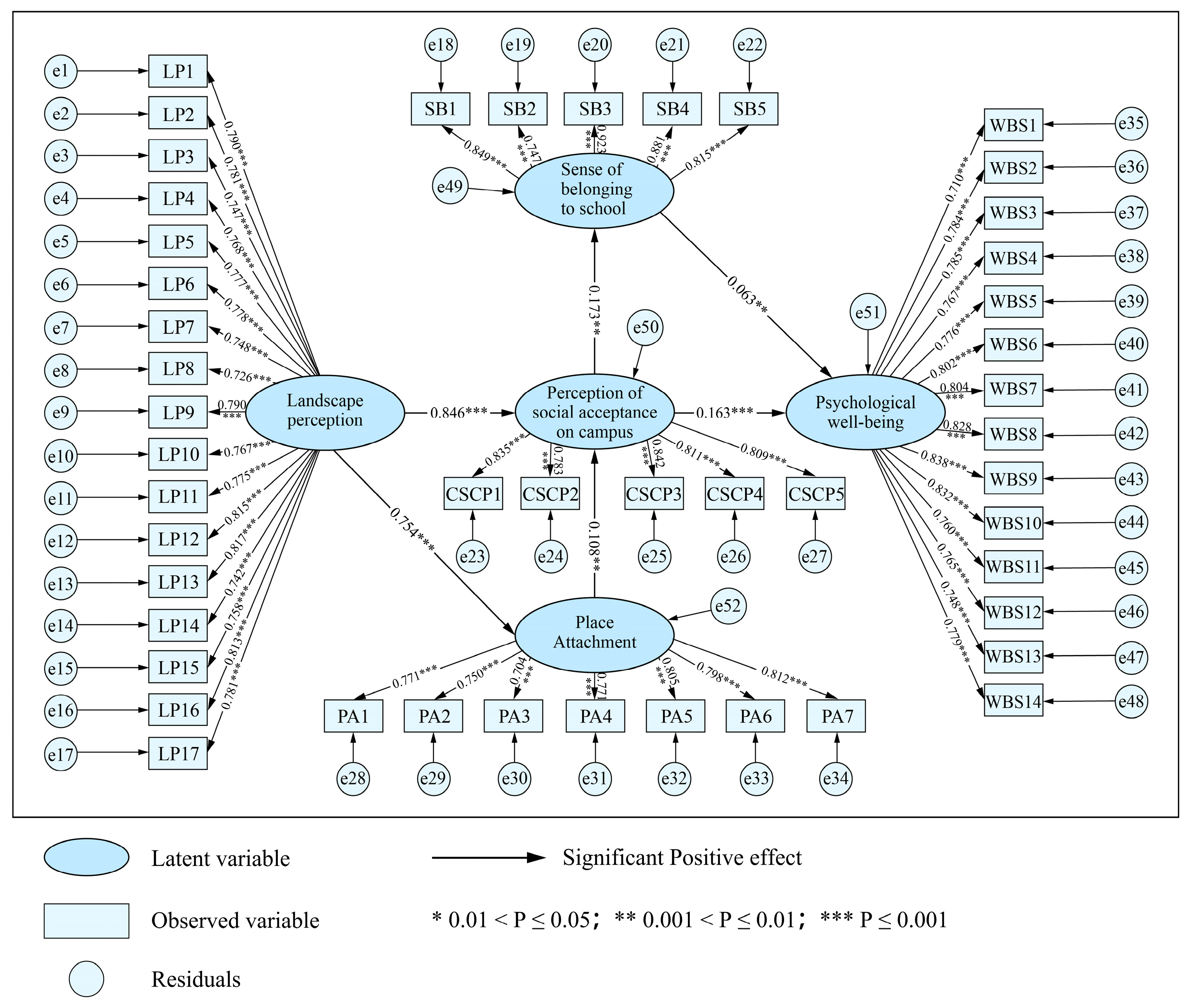

4.2.2. Structural Equation Modeling Results

4.3. Insights from Machine Learning on the Determinants of Psychological Well-Being

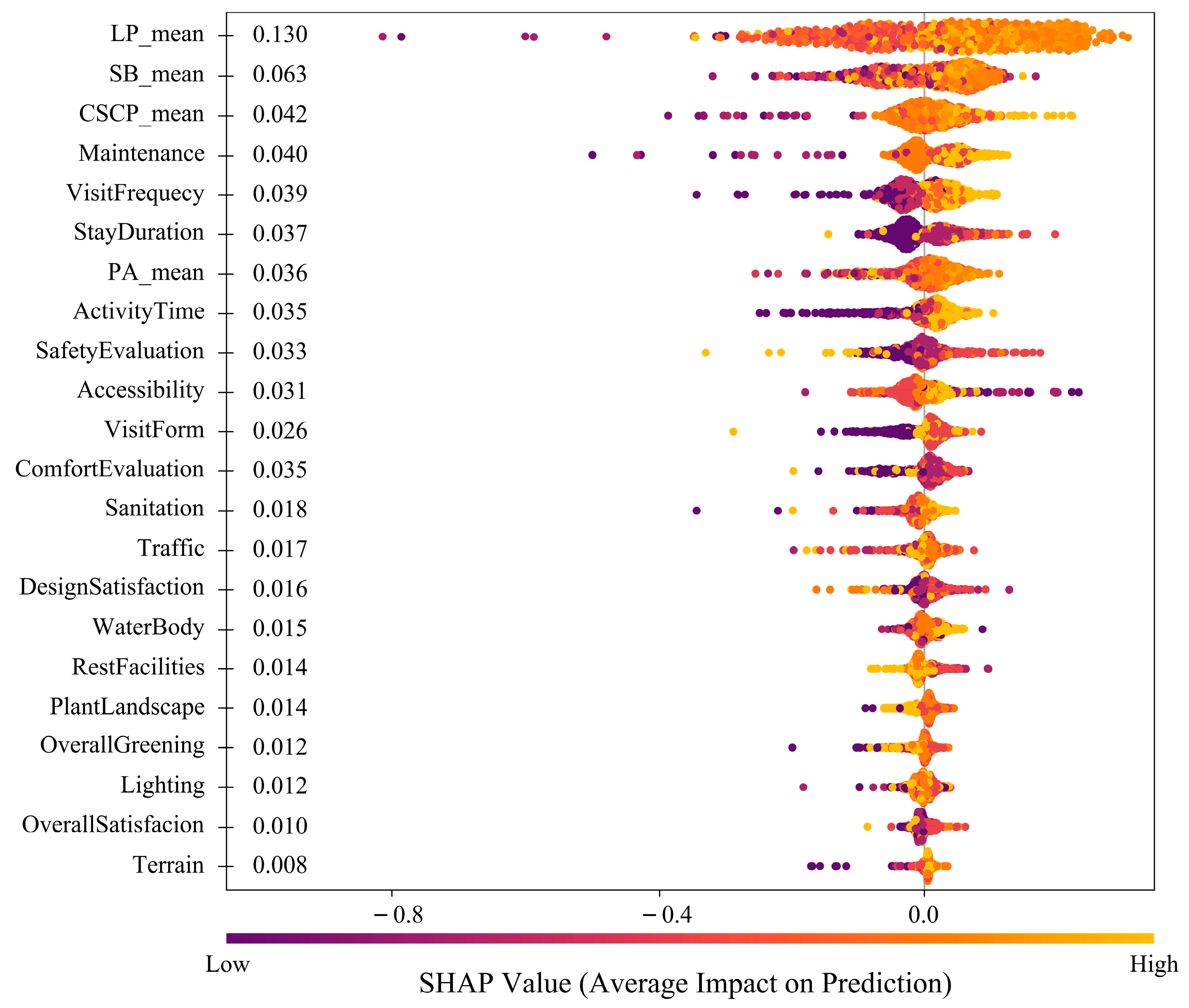

4.3.1. Feature Importance Analysis

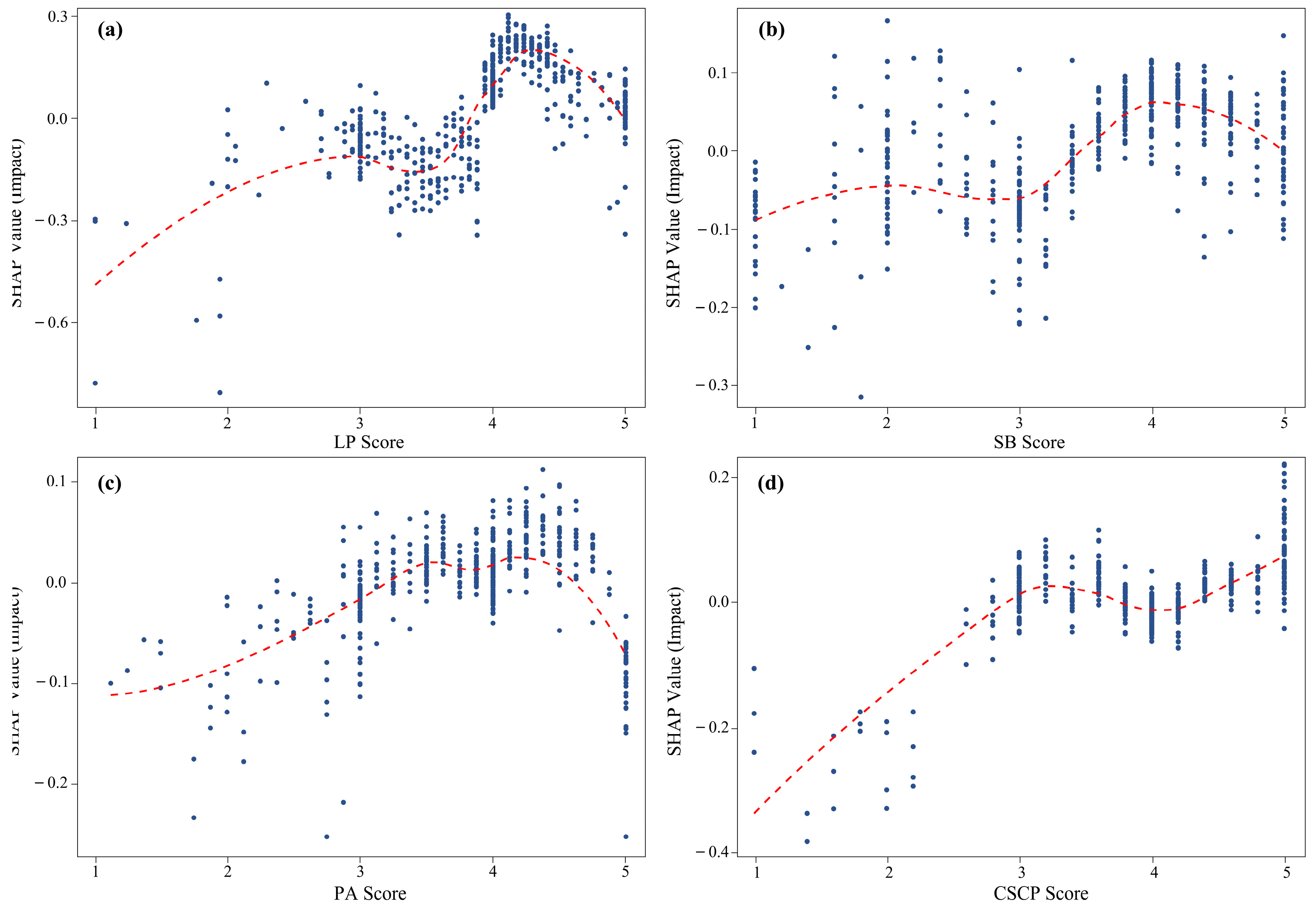

4.3.2. Nonlinear Effects and Threshold Patterns

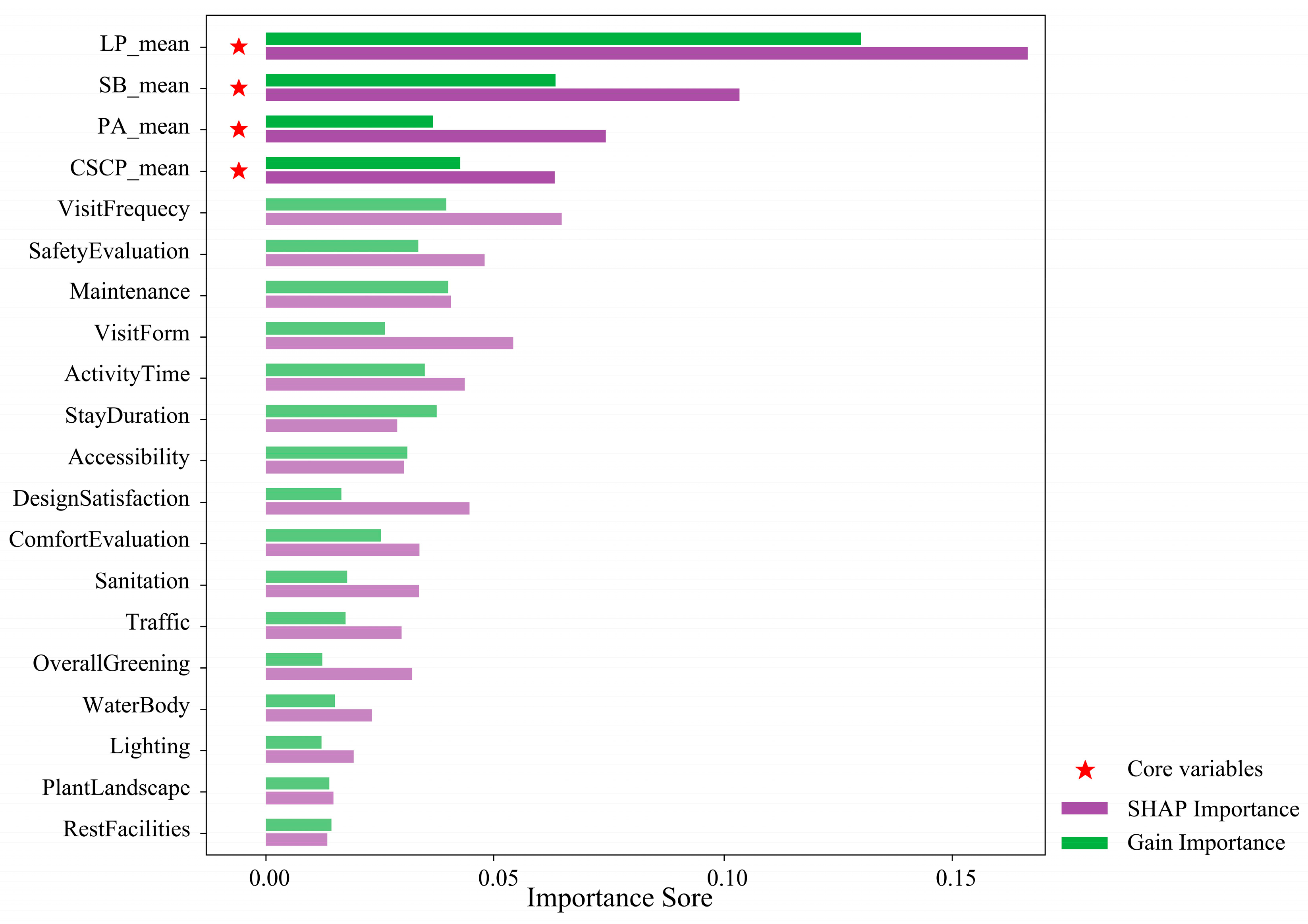

4.3.3. Comparative Analysis of Feature Importance

5. Discussion

5.1. The Interplay Between Campus Landscapes and Social Interaction

5.2. Diminishing Marginal Returns and Saturation Points in Psychological Well-Being

5.3. Integrated Strategies for Optimizing Campus Landscapes and Social Environments

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The SEM results support the hypothesized pathways. Campus landscapes emerge as a starting point for fostering students’ emotional identification and social connection. Landscape perception is significantly associated with psychological well-being via the mediating roles of place attachment, perceived social acceptance, and school belonging.

- (2)

- The XGBoost and SHAP analyses further reveal that landscape perception contributes the most substantial predictive power among all variables, followed by school belonging and perceived social acceptance. These findings highlight the central role of environmental and social-identity factors in shaping psychological outcomes. Behavioral variables—such as green space maintenance quality, visitation frequency, and duration of stay—also show stable but relatively secondary effects.

- (3)

- Clear nonlinear relationships are observed between the core variables and psychological well-being. The positive effects of landscape perception, place attachment, and school belonging plateau at higher levels, indicating diminishing marginal returns. In contrast, perceived social acceptance displays an activation threshold effect, where high levels of social inclusion lead to additional well-being benefits.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| LP | Landscape perception |

| SB | Sense of belonging to school |

| PA | Place attachment |

| WBS | Psychological well-being |

| CSCP | Perception of social acceptance on campus |

References

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P.; et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruffaerts, R.; Mortier, P.; Kiekens, G.; Auerbach, R.P.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Green, J.G.; Nock, M.K.; Kessler, R.C. Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 225, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Cai, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, Z.; He, L.; Li, J. Prevalence of depression among university students in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-S.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Zhu, W.; Ye, Y.-P.; Li, Y.-X.; Meng, S.-Q.; Feng, S.; Li, H.; Cui, Z.-L.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Status and epidemiological characteristics of depression and anxiety among Chinese university students in 2023. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chang, Y.; Cai, X.; Liu, S.; Peng, Y.; Feng, T.; Qi, J.; Ji, Y.; Xia, Y.; Lai, W. Health perception and restorative experience in the therapeutic landscape of urban wetland parks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1272347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Williams, K.J.H.; Sargent, L.D.; Williams, N.S.G.; Johnson, K.A. 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Yang, R.; Li, S. The role of urban green space in promoting health and well-being is related to nature connectedness and biodiversity: Evidence from a two-factor mixed-design experiment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 245, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, K.; Bian, F. How does campus-scape influence university students’ restorative experiences: Evidences from simultaneously collected physiological and psychological data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, R.; Van Calster, H.; Ozen, M.; Benchrih, R.; Heyman, S.; Swerts, E.; Wuyts, A.; Lammens, L.; Lommelen, E.; Leone, M.; et al. Green space at school and attention in primary school children in Belgium: A stratified matched case-control study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 105, 128680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ji, Y.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Lai, W.; Feng, T. Analysis of students’ positive emotions around the green space in the university campus during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 888295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Kirkwood, N. The varied restorative values of campus landscapes to students’ well-being: Evidence from a Chinese University. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, W.; Lu, T. Landscape characteristics of university campus in relation to aesthetic quality and recreational preference. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wu, H.; Collins, R.; Deng, K.; Zhu, W.; Xiao, H.; Tang, X.; Tian, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L. Integrative analysis of health restoration in urban blue-green spaces: A multiscale approach to community park. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, J.; Sun, Y. Psychological and Visual Perception of Campus Lightscapes Based on Lightscape Walking Evaluation: A Case Study of Chongqing University in China. Buildings 2024, 14, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabozorgi, K.; van der Jagt, A.; Bell, S.; Smith, H. The role of university campus landscape characteristics in students’ mental health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 111, 128863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foellmer, J.; Kistemann, T.; Anthonj, C. Academic Greenspace and Well-Being—Can Campus Landscape be Therapeutic? Evidence from a German University. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2021, 2, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakody, D.Y.; Adams, V.M.; Pecl, G.; Lester, E. What makes a place special? Understanding drivers and the nature of place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 163, 103177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Shao, G.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, P. Insights into citizens’ experiences of cultural ecosystem services in urban green spaces based on social media analytics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 244, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Dinh, N.; Zhang, H. How Landscape Preferences and Emotions Shape Environmental Awareness: Perspectives from University Experiences. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, B.; Liang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, W. Time-varying and non-linear associations between metro ridership and the built environment. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 132, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, Z. Evaluation of urban green space landscape planning scheme based on PSO-BP neural network model. Alexandria Eng. J. 2022, 61, 7141–7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, L. Urban virtual environment landscape design and system based on PSO-BP neural network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A. Landscape perception, preference, and schema discrepancy. Environ. Plan. B 1987, 14, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, J.; Deng, T.; Tian, J.; Wang, H. Exploring perceived restoration, landscape perception, and place attachment in historical districts: Insights from diverse visitors. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1156207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhöfen, J.; Härtel, T.; Reichert, G.; Randler, C. The relationship between perception and landscape characteristics of recreational places with human mental well-being. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallavollita, W.L.; Lyons, M.D. Social acceptance from peers and youth mentoring: Implications for addressing loneliness and social isolation. J. Community Psychol. 2023, 51, 2065–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K.R.; Jablansky, S.; Scalise, N.R. Peer social acceptance and academic achievement: A meta-analytic study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 113, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kang, J. Effects of natural sound tempo and social conditions on social Interaction: An interactive virtual experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2025, 104, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Azcárraga, C.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of urban parks and their relation to user well-being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K.; Rivera, E.; Loh, V.; Deforche, B.; Best, K.; Timperio, A. What entices older adults to parks? Identification of park features that encourage park visitation, physical activity, and social interaction. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 217, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester-Herber, M. Underlying concerns in land-use conflicts—The role of place-identity in risk perception. Environ. Sci. Policy 2004, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.S.; Stedman, R.C. A comparative analysis of predictors of sense of place dimensions: Attachment to, dependence on, and identification with lakeshore properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, G.; Reed, P.; Harris, C. Testing a place-based theory for environmental evaluation: An Alaska case study. Appl. Geogr. 2002, 22, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Lee, J.H.; Luloff, A.E. Incorporating Physical Environment-Related Factors in an Assessment of Community Attachment: Understanding Urban Park Contributions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Gu, D.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; Lv, B. Exploring the Link Between Landscape Perception and Community Participation: Evidence from Gateway Communities in Giant Panda National Park, China. Land 2024, 13, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Albert, C.; Guo, X. Exploring the effects of soundscape perception on place attachment: A comparative study of residents and tourists. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 222, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenow, C.; Grady, K.E. The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 62, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. School Bullying and Youth Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: Do School Belonging and School Achievement Matter? Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 2460–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpershoek, H.; Canrinus, E.T.; Fokkens-Bruinsma, M.; de Boer, H. The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Res. Pap. Educ. 2020, 35, 641–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, N.C.S. Nurturing a Sense of Belonging at School: What Helps Pupils Feel Connected? Available online: https://www.ncb.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/news-opinion/nurturing-sense-belonging-school-what-helps-pupils-feel (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Das, K.V.; Jones-Harrell, C.; Fan, Y.; Ramaswami, A.; Orlove, B.; Botchwey, N. Understanding subjective well-being: Perspectives from psychology and public health. Public Health Rev. 2020, 41, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. The Science of Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 37. [Google Scholar]

- Kutek, S.M.; Turnbull, D.; Fairweather-Schmidt, A.K. Rural men’s subjective well-being and the role of social support and sense of community: Evidence for the potential benefit of enhancing informal networks. Aust. J. Rural Health 2011, 19, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Gabriel, S. Chapter Five—The relentless pursuit of acceptance and belonging. In Advances in Motivation Science; Elliot, A.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 9, pp. 135–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo-Rendón, R.; López-Angulo, Y.; Pérez-Villalobos, M.V.; Díaz-Mujica, A. Perceived Social Support and Its Effects on Changes in the Affective and Eudaimonic Well-Being of Chilean University Students. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.; Senra, C.; Fernández-Rey, J.; Merino, H. Sociotropy, Autonomy and Emotional Symptoms in Patients with Major Depression or Generalized Anxiety: The Mediating Role of Rumination and Immature Defenses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Štremfel, U.; Šterman Ivančič, K.; Peras, I. Addressing the Sense of School Belonging Among All Students? A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 2901–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Zhang, T. How Does the Experience of Forest Recreation Spaces in Different Seasons Affect the Physical and Mental Recovery of Users? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Intergroup neighbouring in urban China: Implications for the social integration of migrants. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Neighborhood environments and inclusive cities: An empirical study of local residents’ attitudes toward migrant social integration in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 226, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Duru, E. Initial Development and Validation of the School Belongingness Scale. Child Indic. Res. 2017, 10, 1043–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; Parkinson, J.; Secker, J.; Stewart-Brown, S. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software: Encino, CA, USA, 1995; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.H.; Hossain, S.B.; Mahmud, M.A.; Rahman, K.M.; Mridha, M.S.; Hassan, M.S.; Rahman, S.; Karim, M.R. Exploration of the factors associated with suicide ideation among students: A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2025, 21, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, T.N.; Violato, C. Structural equation modeling in medical research: A primer. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Shi, Y.; Xu, L.; Lu, Z.; Feng, M.; Tang, J.; Guo, X. Exploring the scale effect of urban thermal environment through XGBoost model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Guo, W.; Tang, S.; Zhang, J. Effects of patterns of urban green-blue landscape on carbon sequestration using XGBoost-SHAP model. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 476, 143640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Overview. In International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science; Lovric, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 904–907. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Cai, X.; Peng, Y.; Liu, S.; Lai, W.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, L. The relation between barrier-free environment perception and campus commuting satisfaction. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1294360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M. How might contact with nature promote human health? Promising mechanisms and a possible central pathway. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menatti, L.; Casado da Rocha, A. Landscape and Health: Connecting Psychology, Aesthetics, and Philosophy through the Concept of Affordance. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 00571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Escribano, M.; De Pinedo-García, M. Affordances and Landscapes: Overcoming the Nature–Culture Dichotomy through Niche Construction Theory. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 02294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zentall, S. Optimal stimulation as theoretical basis of hyperactivity. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1975, 45, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez de Aldecoa, P.; Burdett, E.; Gustafsson, E. Riding the elephant in the room: Towards a revival of the optimal level of stimulation model. Dev. Rev. 2022, 66, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C.; Rehdanz, K. The role of urban green space for human well-being. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Jiang, M.; Shi, H.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Li, M.; Jia, X.; Wang, Y. Cross-sectional association of residential greenness exposure with activities of daily living disability among urban elderly in Shanghai. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 230, 113620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Z.; Yang, B.; Ou, Y.; Bloom, M.S.; Han, F.; Qu, Y.; Nasca, P.; Matale, R.; Mai, J.; Wu, Y. Maternal residential greenness and congenital heart defects in infants: A large case-control study in Southern China. Environ. Int. 2020, 142, 105859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, W. Assessing the nonlinear impact of green space exposure on psychological stress perception using machine learning and street view images. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1402536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarasinghe, K.; Rodolfa, K.T.; Lamba, H.; Ghani, R. Explainable machine learning for public policy: Use cases, gaps, and research directions. Data Policy 2023, 5, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Mahdzar, S.S.S.; Li, W. Park inclusive design index as a systematic evaluation framework to improve inclusive urban park uses: The case of Hangzhou urban parks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q. Research on improving urban park green space landscape quality based on public psychological perception: A comprehensive AHP-TOPSIS-POE evaluation of typical parks in Jinan City. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1418477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y. Campus landscape perception decoded by surveys combined with eye tracking: Visual and cultural perception for user well-being. Build. Environ. 2025, 283, 113341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 183 | 36.6% |

| Female | 317 | 63.4% |

| Age(years) | ||

| 17–18 | 54 | 10.8% |

| 19–20 | 205 | 41.0% |

| 21–22 | 164 | 32.8% |

| 23–29 | 77 | 15.4% |

| Education | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 467 | 93.4% |

| Master and above | 33 | 6.6% |

| Specialty | ||

| Philosophy | 17 | 3.4% |

| Economics | 30 | 6.0% |

| Law | 15 | 3.0% |

| Education | 62 | 12.4% |

| Literature | 27 | 5.4% |

| History | 10 | 2.0% |

| Science | 32 | 6.4% |

| Engineering | 40 | 8.0% |

| Agronomy | 13 | 2.6% |

| Medicine | 29 | 5.8% |

| Business Administration | 47 | 9.4% |

| Arts | 146 | 29.2% |

| Others | 32 | 6.4% |

| Monthly consumption | ||

| <1000 CNY | 43 | 8.6% |

| 1000–2000 CNY | 282 | 56.4% |

| 2000–3000 CNY | 108 | 21.6% |

| >3000 CNY | 67 | 13.4% |

| BIM | ||

| <18.5 | 133 | 26.6% |

| 18.5–23.9 | 324 | 64.8% |

| 24.0–27.9 | 34 | 6.8% |

| >28.0 | 9 | 1.8% |

| Structure Variables | Code | Source of Observation Indicators | Standardized Factors Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha Value | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape perception | LP1 | The campus has a high vegetation coverage rate in green spaces. | 0.790 | 0.962 | 0.998 | 0.624 |

| LP2 | The campus green spaces are characterized by a rich botanical diversity. | 0.781 | ||||

| LP3 | A rich variety of natural sounds can be heard in the campus green spaces. | 0.747 | ||||

| LP4 | A rich variety of colors can be observed in the campus green spaces. | 0.768 | ||||

| LP5 | The campus green space design conveys a sense of friendliness, such as through the inclusion of accessible facilities. | 0.777 | ||||

| LP6 | Being in campus green spaces evokes a sense of inner peace. | 0.778 | ||||

| LP7 | There is sufficient space available for further development within the campus green areas. | 0.748 | ||||

| LP8 | Natural landscapes dominate over artificial ones in the campus green spaces. | 0.726 | ||||

| LP9 | The campus green spaces feature diverse vegetation profiles. | 0.790 | ||||

| LP10 | The terrain of the campus green spaces is undulating. | 0.767 | ||||

| LP11 | There is a clear vertical stratification of the landscape in the campus green spaces. | 0.775 | ||||

| LP12 | The landscape design of the campus green spaces is well-conceived. | 0.815 | ||||

| LP13 | The landscape of the campus green spaces is aesthetically pleasing. | 0.817 | ||||

| LP14 | The campus green landscape incorporates elements of the university’s historical and cultural identity. | 0.742 | ||||

| LP15 | The landscape design of the campus green spaces is highly distinctive. | 0.758 | ||||

| LP16 | Engaging in activities within campus green spaces evokes a sense of enjoyment. | 0.813 | ||||

| LP17 | Engaging in activities within campus green spaces is accompanied by a strong sense of safety. | 0.781 | ||||

| Sense of belonging to school | SB1 | You feel like you do not belong to this school. | 0.849 | 0.925 | 0.985 | 0.721 |

| SB2 | You feel that you have not participated in most school activities. | 0.747 | ||||

| SB3 | You feel excluded at this school. | 0.923 | ||||

| SB4 | At this school, you feel that your friends and teachers usually ignore you. | 0.881 | ||||

| SB5 | At this school, you do not have anyone you feel closely (or genuinely) connected to. | 0.815 | ||||

| Place Attachment | PA1 | The campus green spaces are comfortable and allow me to do the things I want. | 0.771 | 0.912 | 0.986 | 0.594 |

| PA2 | I can get more satisfaction in the campus green spaces than in other places. | 0.750 | ||||

| PA3 | What I do on the campus green spaces than in other places. | 0.704 | ||||

| PA4 | The campus green allows me to see what I am interested in. | 0.771 | ||||

| PA5 | I feel that the campus green spaces are part of my life. | 0.805 | ||||

| PA6 | I have a strong identification with the campus green spaces. | 0.798 | ||||

| PA7 | The campus green spaces are special, and I have a good feeling about them. | 0.812 | ||||

| Psychological well-being | WBS1 | I have been feeling optimistic about the future. | 0.710 | 0.957 | 0.996 | 0.504 |

| WBS2 | I have been feeling useful. | 0.784 | ||||

| WBS3 | I have been feeling relaxed. | 0.785 | ||||

| WBS4 | I have been feeling interested in other people. | 0.767 | ||||

| WBS5 | I have had energy to spare. | 0.776 | ||||

| WBS6 | I have been dealing with problems well. | 0.802 | ||||

| WBS7 | I have been thinking clearly. | 0.804 | ||||

| WBS8 | I have been feeling good about myself. | 0.828 | ||||

| WBS9 | I have been feeling close to other people. | 0.838 | ||||

| WBS10 | I have been feeling confident. | 0.832 | ||||

| WBS11 | I have been able to make up my own mind about things. | 0.760 | ||||

| WBS12 | I have been feeling loved. | 0.765 | ||||

| WBS13 | I have been interested in new things. | 0.748 | ||||

| WBS14 | I have been feeling cheerful. | 0.779 | ||||

| Perception of social acceptance on campus | CSCP1 | In the past six months, the experience you had with your classmates was positive. | 0.835 | 0.908 | 0.982 | 0.697 |

| CSCP2 | In the past six months, your classmates have been friendly toward you. | 0.783 | ||||

| CSCP3 | In the past six months, your classmates have been polite to you. | 0.842 | ||||

| CSCP4 | In the past six months, your classmates have been welcoming toward you. | 0.811 | ||||

| CSCP5 | In the past six months, you felt your classmates respected you. | 0.809 |

| Fit Index | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | 2.086 | 0.047 | 0.938 | 0.935 |

| Value | <3 | <0.08 | ≥0.9 | ≥0.9 |

| Latent Variable | Indicator | Estimate | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape perception | LP1 | 0.790 | *** |

| LP2 | 0.781 | *** | |

| LP3 | 0.747 | *** | |

| LP4 | 0.768 | *** | |

| LP5 | 0.777 | *** | |

| LP6 | 0.778 | *** | |

| LP7 | 0.748 | *** | |

| LP8 | 0.726 | *** | |

| LP9 | 0.790 | *** | |

| LP10 | 0.767 | *** | |

| LP11 | 0.775 | *** | |

| LP12 | 0.815 | *** | |

| LP13 | 0.817 | *** | |

| LP14 | 0.742 | *** | |

| LP15 | 0.758 | *** | |

| LP16 | 0.813 | *** | |

| LP17 | 0.781 | *** | |

| Sense of belonging to school | SB1 | 0.849 | *** |

| SB2 | 0.747 | *** | |

| SB3 | 0.923 | *** | |

| SB4 | 0.881 | *** | |

| SB5 | 0.815 | *** | |

| Place attachment | PA1 | 0.771 | *** |

| PA3 | 0.750 | *** | |

| PA4 | 0.704 | *** | |

| PA5 | 0.771 | *** | |

| PA6 | 0.805 | *** | |

| PA7 | 0.798 | *** | |

| PA8 | 0.812 | *** | |

| Psychological well-being | WBS1 | 0.710 | *** |

| WBS2 | 0.784 | *** | |

| WBS3 | 0.785 | *** | |

| WBS4 | 0.767 | *** | |

| WBS5 | 0.776 | *** | |

| WBS6 | 0.802 | *** | |

| WBS7 | 0.804 | *** | |

| WBS8 | 0.828 | *** | |

| WBS9 | 0.838 | *** | |

| WBS10 | 0.832 | *** | |

| WBS11 | 0.760 | *** | |

| WBS12 | 0.765 | *** | |

| WBS13 | 0.748 | *** | |

| WBS14 | 0.779 | *** | |

| Perception of social acceptance on campus | CSCP1 | 0.835 | *** |

| CSCP2 | 0.783 | *** | |

| CSCP3 | 0.842 | *** | |

| CSCP4 | 0.811 | *** | |

| CSCP5 | 0.809 | *** |

| Path | Estimate | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landscape perception → Place attachment | 0.754 | *** | Support |

| Landscape perception → Perception of social acceptance on campus | 0.846 | *** | Support |

| Place attachment → Perception of social acceptance on campus | 0.108 | ** | Support |

| Perception of social acceptance on campus → Sense of belonging to school | 0.173 | ** | Support |

| Perception of social acceptance on campus → Psychological well-being | 0.163 | *** | Support |

| Sense of belonging to school → Psychological well-being | 0.063 | ** | Support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Liu, S. How Campus Landscapes Influence Mental Well-Being Through Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Insights from SEM and Explainable Machine Learning. Land 2025, 14, 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091712

Chang Y, Yang Y, Cai X, Zhou L, Li J, Liu S. How Campus Landscapes Influence Mental Well-Being Through Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Insights from SEM and Explainable Machine Learning. Land. 2025; 14(9):1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091712

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Yating, Yi Yang, Xiaoxi Cai, Luqi Zhou, Jiang Li, and Shaobo Liu. 2025. "How Campus Landscapes Influence Mental Well-Being Through Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Insights from SEM and Explainable Machine Learning" Land 14, no. 9: 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091712

APA StyleChang, Y., Yang, Y., Cai, X., Zhou, L., Li, J., & Liu, S. (2025). How Campus Landscapes Influence Mental Well-Being Through Place Attachment and Perceived Social Acceptance: Insights from SEM and Explainable Machine Learning. Land, 14(9), 1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14091712