1. Introduction

Common prosperity, with its emphasis on addressing income disparities, narrowing the poverty gap, and achieving inclusivity, has gained global consensus [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This consensus reflects the vision of human society, advocated by Stephanie Kelton, where prosperity is widespread and shared, with an economy that benefits everyone, not just those at the top [

5]. Governments worldwide commit to this developmental goal for human society, recognizing the pivotal role of common prosperity in attaining sustainable development. In China, common prosperity is emphasized as a long-term goal following the elimination of extreme poverty and the realization of a moderately prosperous society, aiming to address issues of inequality and underdevelopment [

6]. Essentially, common prosperity pertains to the elimination of polarization and poverty. Based on the practice of China’s social and economic development, the concept of common prosperity integrates “development” and “sharing”, aiming to achieve “shared prosperity” rather than “equal prosperity” through redistribution [

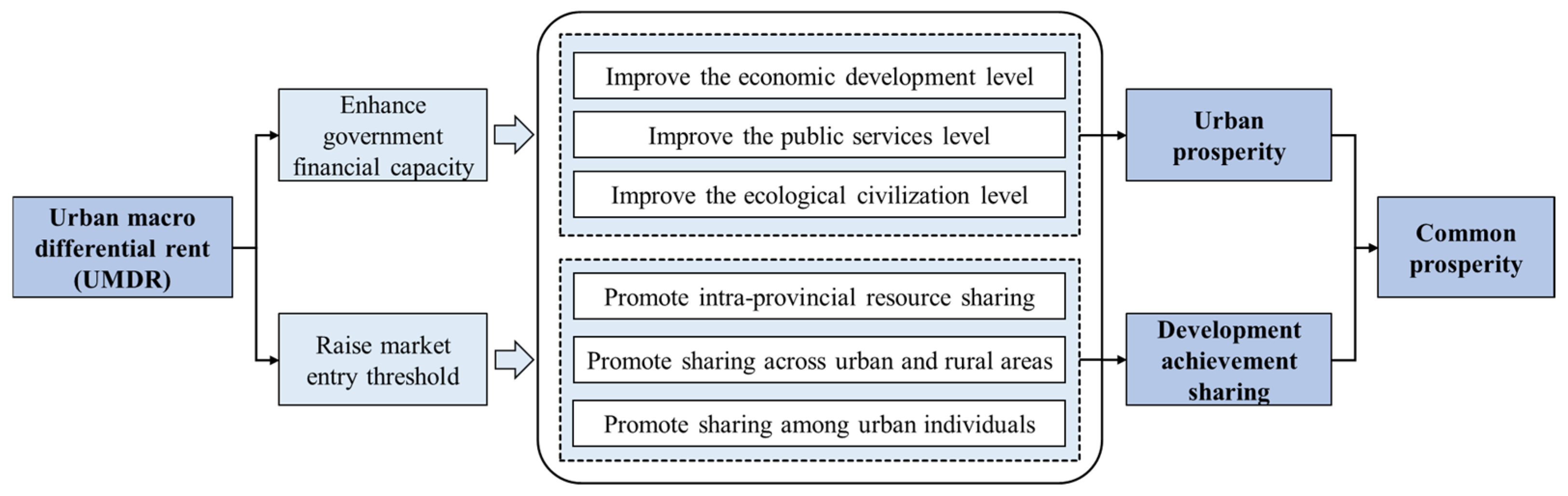

7]. The concept first emphasizes urban prosperity, meaning the continuous improvement of societal welfare and well-being at higher levels of development [

8]. This is manifested through enhanced economic growth, public services, and ecological civilization, forming the essential material foundation for achieving common prosperity. Second, common prosperity is defined by the principle of sharing development achievement, ensuring that the benefits of reform and development are distributed more equitably among all people [

9]. This necessitates a balanced distribution of gains across urban and rural areas, throughout provinces, and among urban residents themselves. Therefore, common prosperity represents a situation where both the material and spiritual well-being of individuals are enhanced, ensuring equal rights for different groups to access wealth and quality public services [

8,

9]. It involves an ongoing process of good governance that adapts to societal changes. Development must be aligned with the carrying capacity of the population, resources, and environment, and it must also keep pace with social progress [

9]. Currently, China has made significant progress in eradicating extreme poverty [

10,

11]. Its large economy and population of around 1.4 billion continue to pose challenges in advancing common prosperity. China still faces significant income and wealth disparities, with a Gini coefficient persistently above 0.46 and wealth inequality showing signs of renewed expansion [

12]. In addition, the expanding urban–rural divide and regional development disparities emphasize the pressing need to develop a strategy for equitable growth [

13]. Therefore, China urgently needs a comprehensive approach to achieving common prosperity. Given China’s economic scale and demographic diversity, its strategies and successes in this area are paramount and provide a pivotal case study for the global effort.

In China’s state-owned urban land system, local governments rely on land transfer fees as a primary revenue source [

14]. Representing the transaction price for urban land use rights, land transfer fees serve as a capitalized income from leasing land, reflecting the combined revenue of urban land utilization and distribution [

15]. The land utilization revenue of a city significantly impacts its local government’s fiscal capacity and the national income redistribution [

16,

17]. Recently, disparities in land revenue among cities have widened rapidly due to differences in locational factors and capital investment [

15], leading to the emergence of urban macro differential rent (UMDR). It refers to the land differential income, which exceeds the absolute land rent of a city due to variations in location, scale, and function. The UMDR serves as the financial backbone for local governments, enabling them to craft policies that attract resources, invest in urban public infrastructure, and optimize the allocation of ecological space [

18,

19,

20]. This fiscal strategy is pivotal for enhancing urban economic growth, improving public services, and advancing ecological sustainability [

21,

22,

23]. Moreover, UMDR enables local governments to implement targeted policies that bridge development gaps between urban and rural areas, as well as different population groups, distributing wealth and opportunities more equitably by leveraging differences in land value and financial returns [

24,

25]. By addressing specific economic and social needs, UMDR supports more balanced and inclusive development, which is pivotal for achieving common prosperity [

26]. Given the notable influence of land value and related fiscal revenues on socio-economic objectives, it is crucial to analyze UMDR’s contribution to achieving common prosperity in China.

Scholars have extensively researched the differential land rent across different regions within cities and proposed that urban differential rent can maximize the rational use of limited land and enhance the environmental, social, and economic benefits of urban land use [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. However, few studies focus on UMDR that examine this concept from a broader citywide perspective. The significant and rapidly expanding differences in land rent among cities of various tiers are influenced by factors such as geographical location, economic development level, future development expectations, and capital flow [

32]. Scholars devised a calculation model for UMDR, applying Marx’s theory of ground rent. They contend that UMDR, generated by disparities in location and investment, aggravates urban inequality, impeding equal regional development [

33]. Contrary to this viewpoint, certain scholars argue that UMDR exerts a beneficial influence on urban development. They highlight the beneficial effects of UMDR, arguing that it boosts the quality of urban development by stimulating factor flow, fostering industrial upgrades, and so forth [

15]. These findings suggest that views on the impact of UMDR are divided and need further investigation.

Existing research mainly focuses on constructing and evaluating indicator systems for common prosperity [

6,

34], examining their impact factors, such as resource utilization efficiency [

35], low-carbon initiatives [

36], and digital inclusive finance [

37]. The relationship between UMDR and common prosperity is less established. A related study on the impact of UMDR on regional economic disparities in China finds that the emergence of UMDR is accompanied by uneven regional economic development, with increasing disparities in land rent between cities leading to wider regional economic gaps. The scholar believes that narrowing the land rent gap between underdeveloped and developed cities promotes the reduction of regional economic disparities [

38]. Using 273 prefecture-level cities in China from 2004 to 2017 as research subjects, other scholars employed econometric models and mediation effect models to examine the impact mechanism of UMDR on high-quality urban development. They concluded that UMDR significantly promotes the high-quality development of cities through several mechanisms: accelerating factor flow, fostering coordinated industrial development, improving infrastructure supply, equalizing public services, stabilizing fiscal support, and protecting the ecological environment [

15]. The aforementioned research findings primarily explore the impact of UMDR on regional disparities and the economic and social development of cities, addressing only a small aspect of the connotation of common prosperity and not extending to the impact of UMDR on common prosperity. Addressing this gap, we explore the spatiotemporal evolution and causal relationship between UMDR and common prosperity by using data from 280 Chinese cities spanning 2007 to 2020.

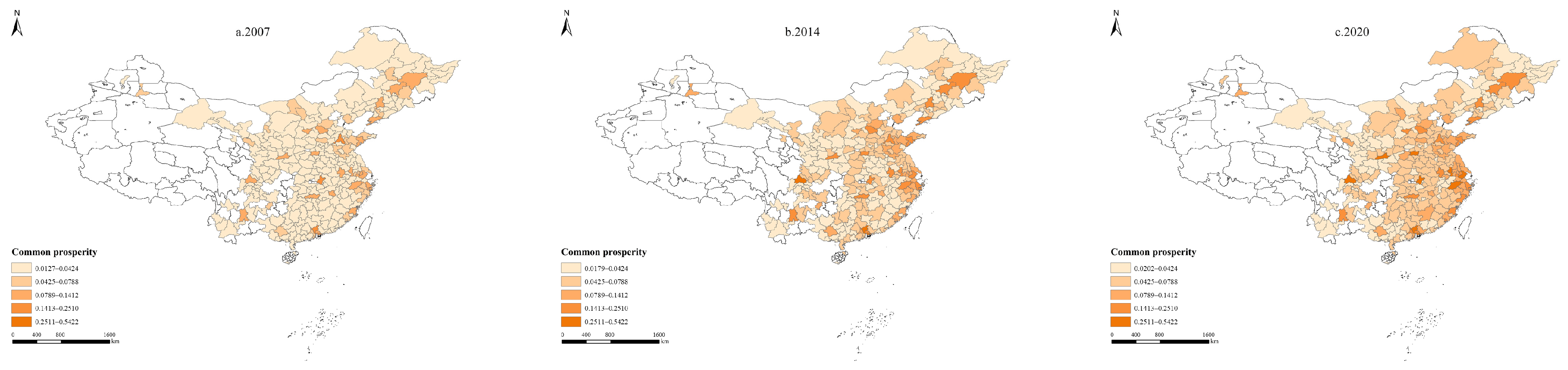

In our paper, we comprehensively measure the common prosperity index and the degree of UMDR. Throughout the study period, both indices showed a distinct upward trend and displayed a significant spatial correlation. Further econometric analysis confirmed that UMDR significantly enhances the level of common prosperity. This conclusion remains robust after conducting a series of general endogeneity tests and implementing controls for endogeneity. Our analysis reveals that UMDR boosts common prosperity by enhancing urban prosperity and development achievement sharing. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that the effects of UMDR on common prosperity, urban prosperity, and development achievement sharing are notably stronger in eastern cities and those where service industries dominate the economy.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the impact of urban differential rent on common prosperity. It enriches the existing literature in three ways. First, our study offers a fresh insight into understanding the urban land revenue disparity and the common prosperity development goal through the empirical evidence on differential land rent from a broad citywide perspective. By broadening the scope to encompass entire cities, our study offers a more comprehensive understanding of how land revenue dynamics at a macro level influence the broader socio-economic outcomes. Second, by meticulously deconstructing and analyzing the layers of common prosperity indicators, we explored the impact mechanisms of UMDR on common prosperity across various dimensions. This detailed approach is vital considering the multifaceted nature of common prosperity. By dissecting these layers, our study deepens the understanding of how UMDR influences various facets of urban development and achievement sharing and identifies critical areas for policy intervention to foster common prosperity. Third, our study offers valuable insights from a developing country perspective, demonstrating that urban land revenue disparity can be a potent catalyst for common prosperity. This is particularly relevant for countries with substantial state land holdings, where our findings can inform and enhance land regulation reforms. Moreover, our study systematically underscores the dual functionality of land rent, not only as a mechanism for fostering economic growth but also as a means to promote social and regional equity.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the theoretical analysis and hypotheses.

Section 3 presents the methodology.

Section 4 reports the results and analysis.

Section 5 introduces the mechanism analysis. The heterogeneity effect is presented in

Section 6. Finally,

Section 7 draws the conclusions.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

From the perspective of urban macro differential rent, this paper analyzes the impact of urban land revenue on common prosperity in a panel dataset covering 280 Chinese cities from 2007 to 2020. Within our sample, the spatiotemporal evolution of UMDR and common prosperity exhibits striking similarities. Empirical results further reveal a significant promotion of common prosperity by UMDR, where a 1 standard unit increase in UMDR corresponds to a 0.217 standard unit increase in the level of common prosperity. This growth is primarily driven by improvements in urban prosperity and development achievement sharing. UMDR positively impacts economic development, transportation infrastructure, healthcare, public culture, social security, and ecological civilization levels, thereby promoting urban common prosperity. It also contributes to the sharing of development achievements by facilitating more equitable sharing of achievements between urban and rural areas and among individuals. Nevertheless, UMDR falls short in promoting intra-provincial resource sharing. Furthermore, UMDR has a more significant driving effect on the common prosperity of eastern cities and cities dominated by the service industry.

Our study provides several policy implications. Firstly, to attain common prosperity, administrative bodies should maximize the benefits of UMDR. Our findings show that UMDR plays a pivotal role in stimulating economic growth, improving public services, and ensuring equitable distribution of development gains between urban and rural areas, thus aiding social equity. Therefore, local governments need to enhance urban allure to elevate land values and rents, effectively leveraging UMDR’s potential in generating income and applying threshold screening to consistently progress towards common prosperity.

Secondly, to ensure equitable advancement in common prosperity, the nation should implement specific policies aiding cities and regions with low UMDR, focusing particularly on central and western areas. Our findings suggest that while a higher UMDR bolsters common prosperity in cities, predominantly in eastern regions, it simultaneously disadvantages cities and regions with significantly low land rents. This imbalance could result in these areas falling further behind in achieving common prosperity. Consequently, the central government should offer special assistance, including fiscal transfers and investment incentives, to mitigate these disparities.

Finally, throughout the development of common prosperity, it is crucial to fortify regional resource-sharing mechanisms. Our research identifies limitations in facilitating regional resource sharing via UMDR; therefore, it is essential to establish and execute intra-provincial resource-sharing mechanisms. These should include fiscal redistribution and comprehensive regional development strategies, ensuring that the advantages of high UMDR in specific cities are extended to their neighboring areas.