Counter-Cartographies of Extraction: Mapping Socio-Environmental Changes Through Hybrid Geographic Information Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

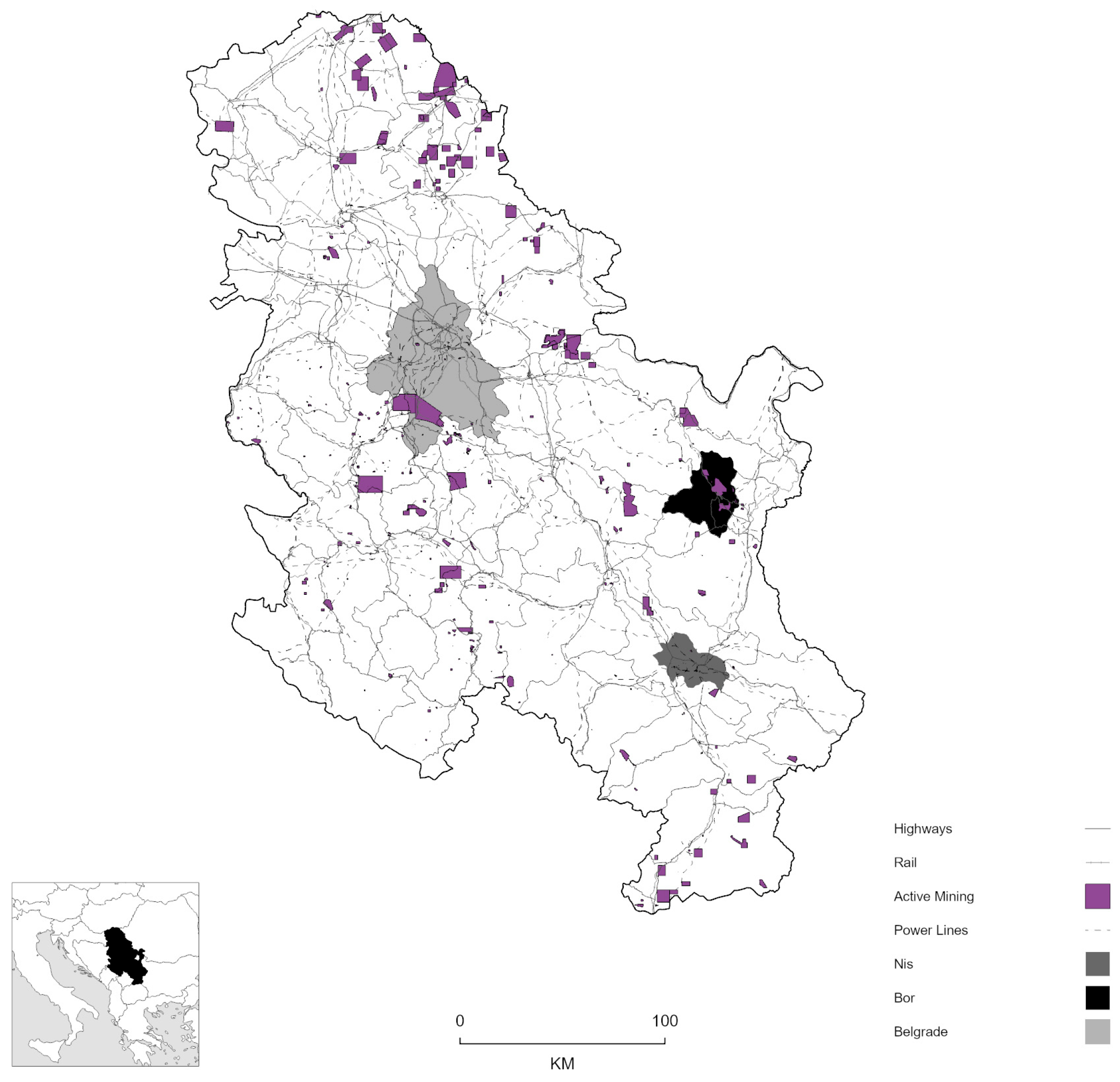

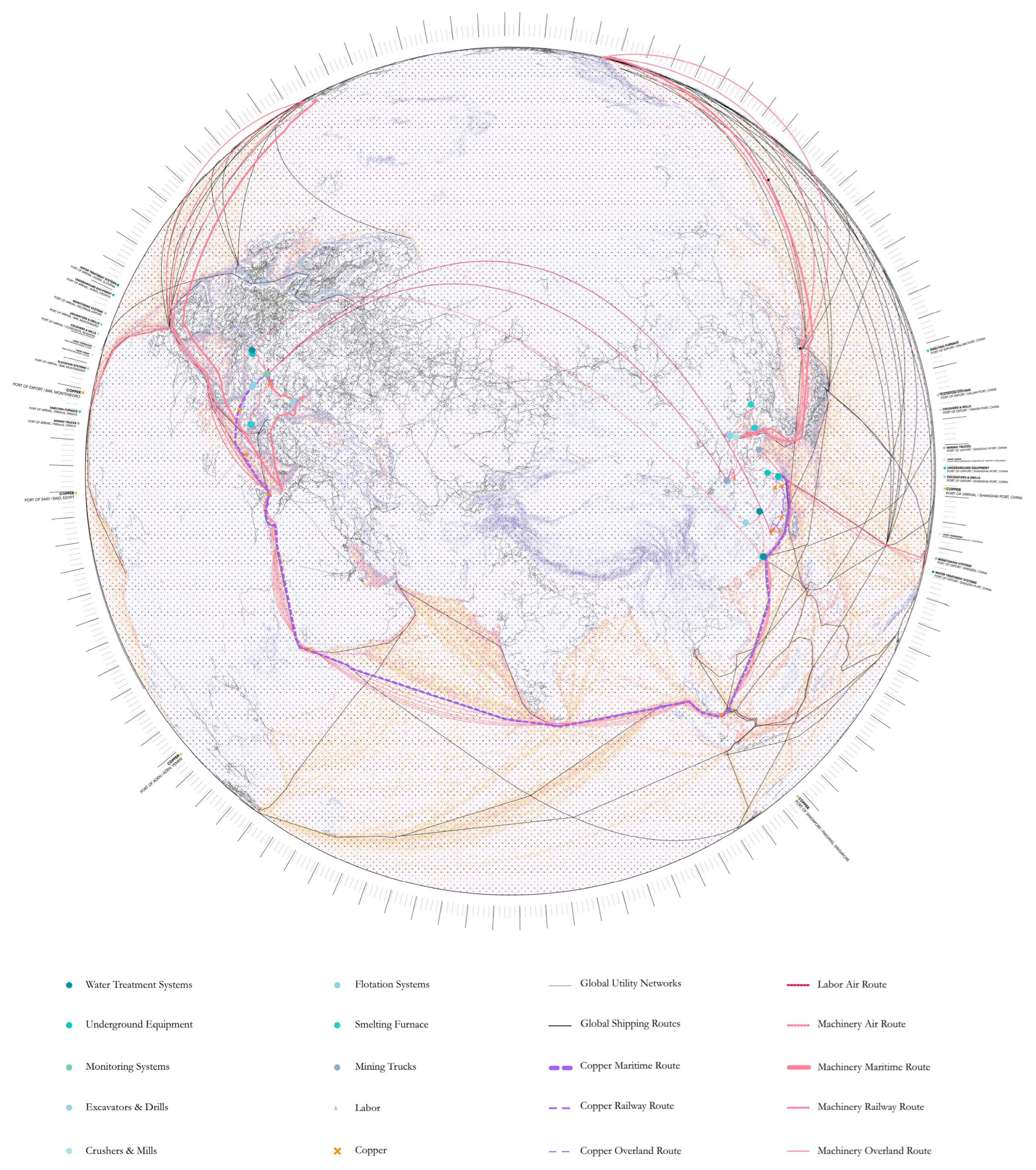

1.1. Krivelj at the Threshold of Global Extraction

1.2. Problem Space: Critiquing Planetary Urbanization

1.3. Counter-Cartographies as Methodological Intervention

- Geomatics offers tools for territorial analysis via satellite imagery, GIS mapping, and environmental modeling;

- Ethnographic fieldwork reveals the emotional and historical aspects of displacement [17] via oral histories, sensory ethnography, and participatory mapping;

- Architecture deciphers legal frameworks that make extraction possible and inevitable, viewing spatial plans and built forms as ideological tools.

1.4. Situating the Research: From Local Narratives to Global Assemblages

1.5. Research Questions and Objectives

- How do transscalar extraction processes, from global supply chains to bodily exposures, manifest in the spatial reorganization of Krivelj?

- What knowledge and tools are needed to map these transformations without reproducing the forces of abstraction?

- How can transdisciplinary methods enable rigorous, flexible, and collaborative counter-cartographies?

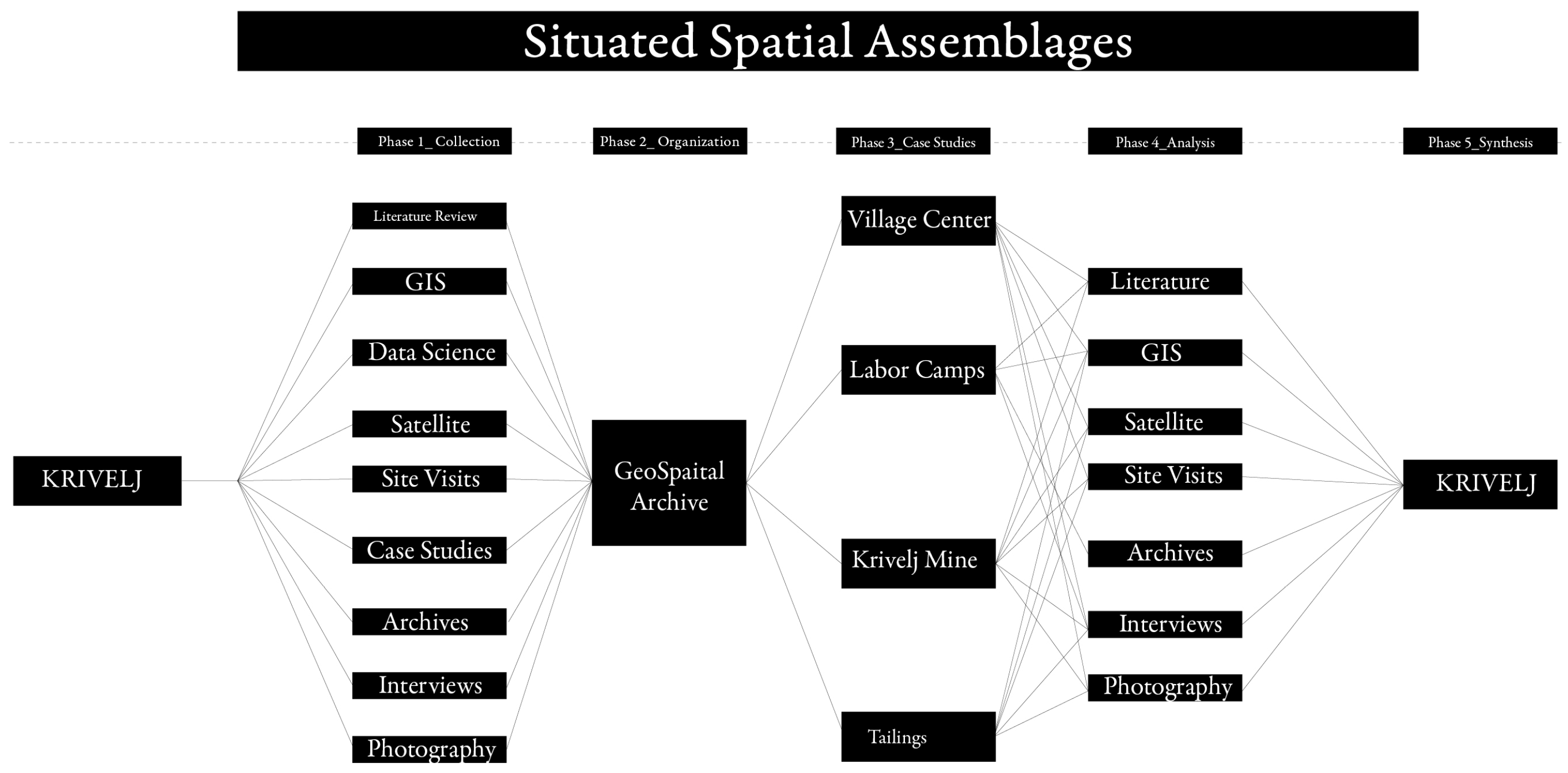

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Research Orientation: Why a Transdisciplinary Approach?

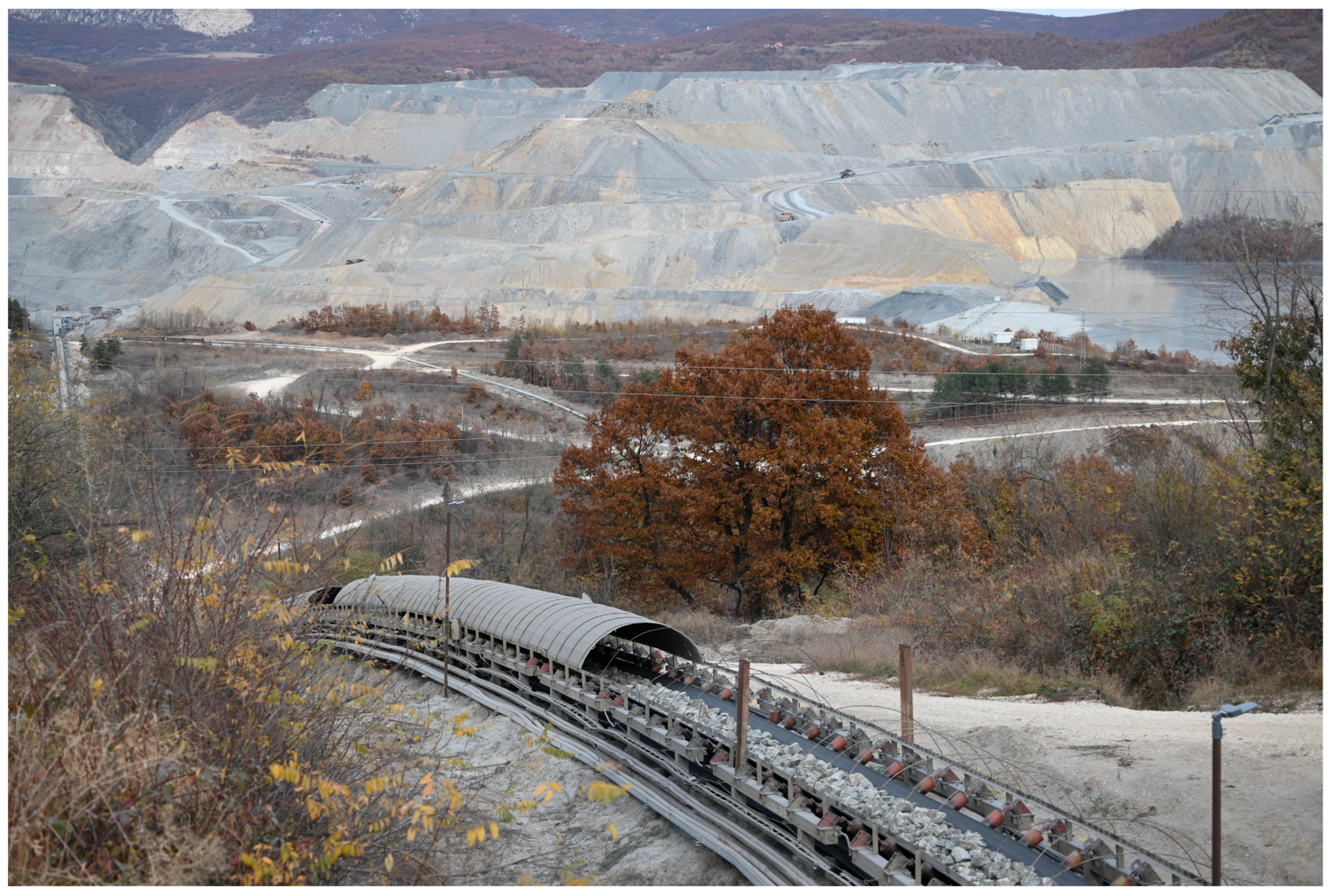

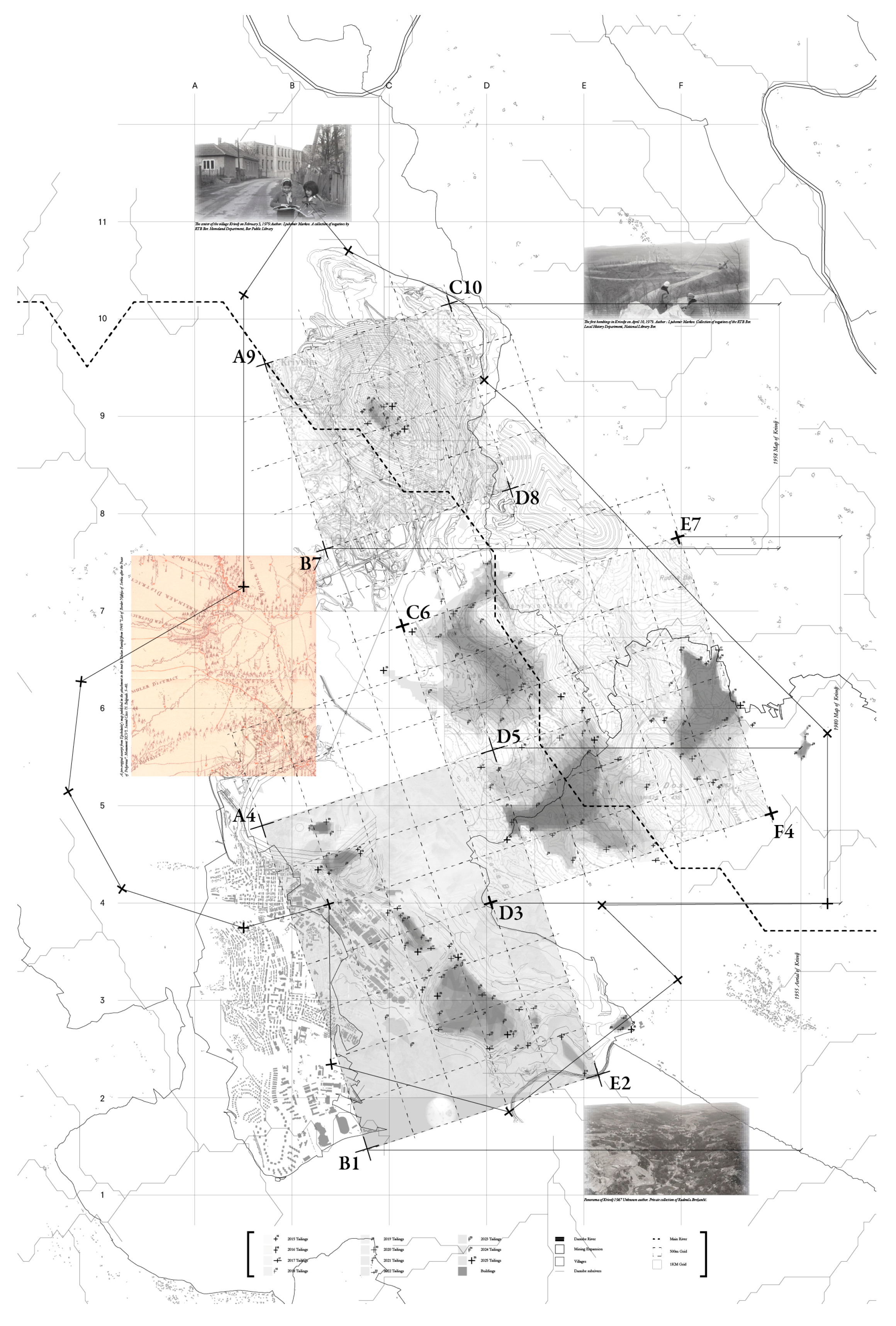

2.2. The Research Site: Krivelj as a Territorial Laboratory

2.3. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Structure

- Territorial Restructuring: Building on Stuart Elden’s reconceptualization of territory as a form of political technology [33], this research explores how territory is created through planning, force, and abstraction.

- Forensic Spatial Analysis: Drawing on Eyal Weizman’s work with Forensic Architecture, this research employs mapping not as a neutral representation but as a counter-investigative practice that reveals hidden or denied spatial histories [7].

2.4. Methodological Contributions by Discipline

- Satellite Remote Sensing: Analyzing Landsat and Sentinel-2 imagery revealed land cover changes, assessed vegetation loss, and tracked hydrological rerouting. NDVI analysis showed a decline in biomass near the tailing expansions.

- Environmental Modeling: measuring and modeling air, water, and noise pollution as a result of mining and the expansion of the mine.

- Georeferencing Participatory Data: Residents’ memory maps from the workshop are overlaid on official cadastral basemaps, revealing spatial gaps between official and lived geographies.

- Software and Datasets: ArcGIS Pro and Rhino were the main tools, with data from Copernicus, NASA EarthData, and the Serbian Geodetic Authority.

- Semi-Structured Interviews: Conducted with twelve residents, mostly displaced or at risk, focusing on place attachment, memory, health, and spatial practices pre- and post-mine expansion.

- Personal Sketching: Interviewees illustrated their memories of Krivelj “before the mine.” These sketches evolved into intuitive maps that expressed personal geographies and localized epistemologies of space. Intuitive mapping challenges the Cartesian, objective, and colonial logics of conventional cartography by foregrounding affective, embodied, and subjective spatial experiences. Drawing from critical theory, psychoanalysis, and feminist geography, this methodology sees maps not merely as representational tools but as instruments for exposing and subverting hegemonic spatial orders.

- Positional Awareness: Documented spatial and ethical tensions, especially when community suspicions about academic visitors intersected with trauma and grief.

- Spatial Plan Analysis: Reviewed spatial planning documents to integrate extraction with regional development goals while examining any potential contradictions with reality.

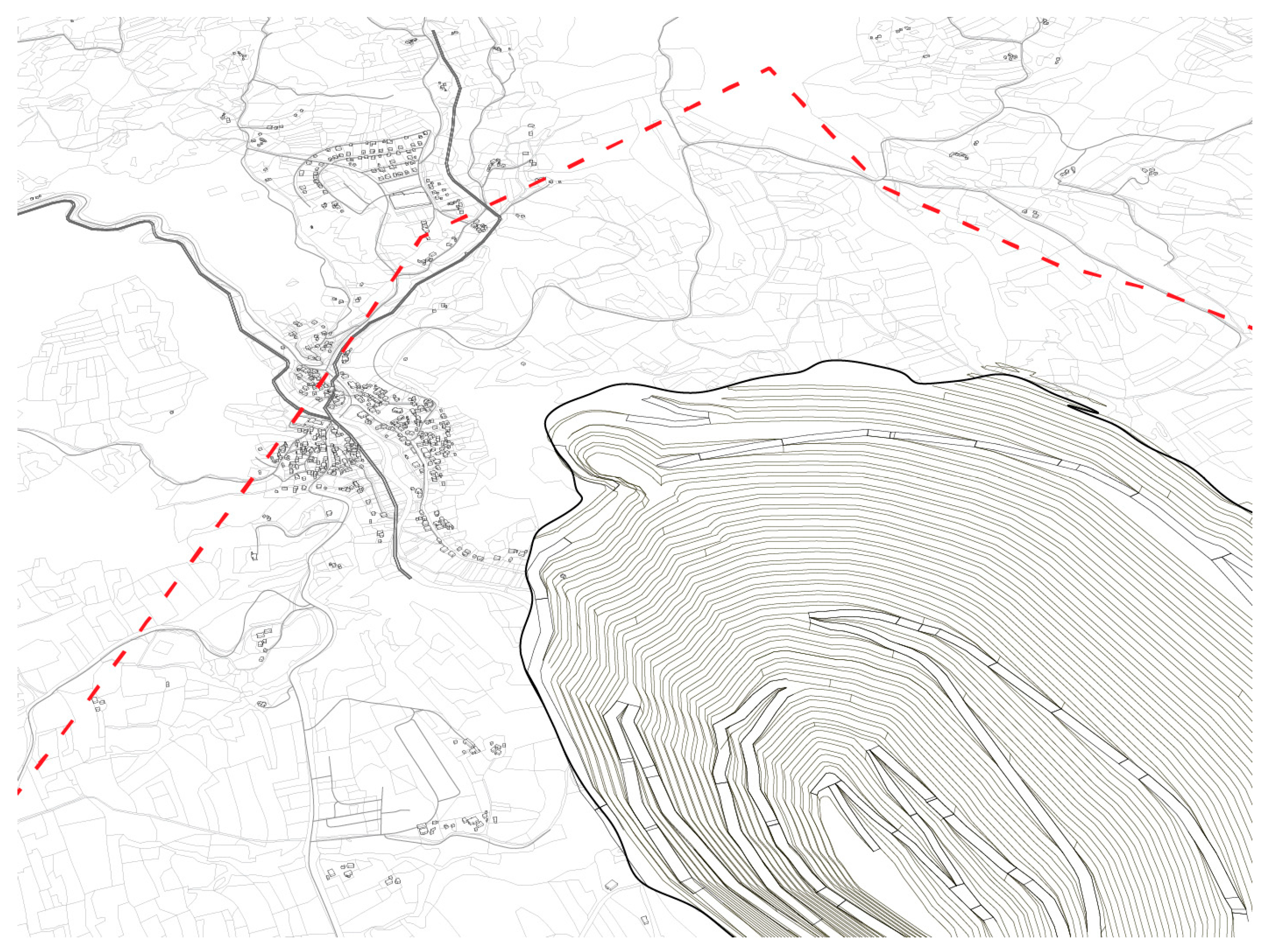

- Cadastral Review: Property titles and land classifications were examined via Serbia’s e-Cadastre. The people on the land still own areas labeled as owned by Zijin in the Planning reports.

- Design Reading: Analyzed urban planning and relocation for housing, villages, and worker camps using architectural methods. Key questions included the following: What life is envisioned by these spaces? Who do they aim to exclude?

2.5. Participatory Counter-Mapping and Reflexive Practices

- Mapping Workshops: Residents illustrated memory-based spatial features, such as vanished orchards, community gathering spots, and burial sites (Figure 6).

- GIS Integration: The drawings were digitized, georeferenced, and integrated with GIS layers displaying zoning changes, mining concessions, and tailings expansion.

- Map Narration: Residents annotated digital maps with stories, warnings, or critiques, turning them into spatial testimonies (Figure 7).

2.6. Integration and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Social Entanglements: Mapping Fragmented Relocation

3.2. Labor Entanglements: Mapping Economic Dependency and Precarity

3.3. Mapping as a Counter-Narrative: Revealing Entangled Geographies

3.4. Visual and Cartographic Methods for New Spatial Plans

- Hydrological disturbances: Redirection of the Krivelj River affects downstream flooding and soil erosion.

- Toxic flows: Mapping pollutant distribution from tailing ponds to rivers and aquifers shows the link between local ecological crises and broader environmental systems, challenging the notion of isolated extraction areas.

3.5. Synthesis and Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Extraction as Territorial Rewriting: Beyond Material Degradation

4.2. Critiquing Urban Abstraction: Planetary Urbanization Revisited

4.3. Scalar Entanglement and the Body as a Site of Extraction

4.4. Counter-Cartography as Spatial Praxis

4.5. Political Implications: Extraction as Governance and Governance as Extraction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Correa, F. Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. When Territory Deborders Territoriality. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2013, 1, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. Transition Minerals Tracker: 2024 Global Analysis; Business & Human Rights Resource Centre: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/from-us/briefings/transition-minerals-tracker-2024-global-analysis/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Journalists in Trouble: Russian Authorities Declare RFE/RL an ‘Undesirable Organization’; Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: Prague, Czech Republic; Available online: https://about.rferl.org/article/journalists-in-trouble-russian-authorities-declare-rfe-rl-an-undesirable-organization/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Petrović, M.; Tošović, L.; Krčum, A. Population Relocation from Mining Activity Zone: A Case Study of the Krivelj Settlement. In Lokalna Samouprava u Planiranju i Uređenju Prostora i Naselja. Zbornik Radova Mladih Istraživača; Joksimović, M., Protić, B., Eds.; Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, S. Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weizman, E. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability; Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Planetary Urbanization. In Urban Constellations; Gandy, M., Ed.; Jovis Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Katsikis, N. Operational Landscapes: Hinterlands of the Capitalocene. Archit. Des. 2020, 90, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, E. Culture and Imperialism; Vintage Books, Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Urbanisms, Worlding Practices and the Theory of Planning. Plan. Theory 2011, 10, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, K. Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space; Verso: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Łapinski, J.L. Rozwój zrównowa zony a polityczny poziom definiowania natury/Sustainable Development Versus Political Aspect of Defining the Nature. Probl. Ekorozw. Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 4, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, C. Vagabond Capitalism and the Necessity of Social Reproduction. Antipode 2004, 36, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, J. Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, C. A Phenomenology of Landscape; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Veselinović, M. The Post-Socialist Legacy of Bor: Industry, Displacement and Memory. J. Balk. Stud. 2015, 11, 110–132. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanović, N.; Danilović Hristić, N.; Petrić, J. Spatial Planning, Environmental Activism, and Politics—Case Study of the Jadar Project for Lithium Exploitation in Serbia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, W. Constitutive outsides or hidden abodes? Totality and ideology in critical urban theory. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 1827–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, A. The Resurgence of the ‘Region’ and ‘Regional Identity: Theoretical Perspectives and Empirical Observations on Regional Dynamics in Europe. Rev. Int. Stud. 2009, 35, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longley, P.A.; Goodchild, M.F.; Maguire, D.J.; Rhind, D.W. Geographic Information Systems and Science, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vujić, S. The History of Serbian Mining. In Serbian Mining and Geology in the Second Half of XX Century, Roots; Academy of Engineering Sciences of Serbia, Matica Srpska, Mining Institute of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sekulić, D. Glotzt Nicht so Romantisch—On Extra-Legal Space in Belgrade; Jan van Eyck Academie and Early Works: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vujosevic, M.; Nedovic-Budic, Z. Planning and institutional reforms in an environment of transition: A case of Serbia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2006, 14, 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Serbia. Law on Investments. In Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia; No. 89/2015 and 95/2018; Government of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ristivojević, D.; Lazar, D. Bor Mining and Smelting Complex (Serbia Zijin Copper)—Bor, Majdanpek, 741 Krivelj, and Oštrelj, Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://thepeoplesmap.net/project/bor-mining-and-smelting-complex-serbia-zijin-copper/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Novaković, I.; Todorović Štiplija, N. Privilegovani Prijatelj: Kakve Koristi ima Srbija od Prodaje RTB-a Bor? Centar za Savremene Politike (CSP): Belgrade, Serbia, 2020; ISBN 978-86-80576-11. Available online: https://centarsavremenepolitike.rs/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Privilegovani-prijatelj-Kakve-koristi-ima-Srbija-od-prodaje-RTBa-Bor.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025). (In Serbian)

- B92. Available online: https://www.b92.net (accessed on 24 March 2025). (In Serbian).

- Zijin Mining Group Co., Ltd. Interim Report 2024; Zijin Mining Group Co., Ltd.: Longyan, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.zjky.cn (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- An interview with Jasna Tomić, resident and activist. 4 November 2024.

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Interview with Siniša Trkulja, representative of Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure of Republic of Serbia. 13 February 2025.

- Elden, S. The Birth of Territory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D. Everything Sings: Maps for a Narrative Atlas; Siglio Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- An interview with Milos Božić, resident and activist. 6 December 2024.

- Petrović, M.; Tošović, L.; Krčum, A. Population relocation from mining activity zone: A case study of the Krivelj settlement. In Planska i Normativna Zaštita Prostora i Životne Sredine, Zbornik Radova Mladih Istrazivača; Univerzitet u Beogradu-Geografski fakultet, Beograd: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.E. Mappings; Reaktion Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, J.B. Deconstructing the Map. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovis. 1989, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manić, B.; Petrić, J.; Milijić, S. (Eds.) Jubilee 65 Years: Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning of Serbia 1954–2019; Institute of Architecture and Urban Planning of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, K.H. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N. Fortunes of Feminism: From State-Managed Capitalism to Neoliberal Crisis; Verso: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W.D. Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and Decolonial Freedom. Theory Cult. Soc. 2009, 26, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbembe, A. Necropolitics. Public Cult. 2003, 15, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dixit, M.; Danilović Hristić, N.; Stefanović, N. Counter-Cartographies of Extraction: Mapping Socio-Environmental Changes Through Hybrid Geographic Information Technologies. Land 2025, 14, 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081576

Dixit M, Danilović Hristić N, Stefanović N. Counter-Cartographies of Extraction: Mapping Socio-Environmental Changes Through Hybrid Geographic Information Technologies. Land. 2025; 14(8):1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081576

Chicago/Turabian StyleDixit, Mitesh, Nataša Danilović Hristić, and Nebojša Stefanović. 2025. "Counter-Cartographies of Extraction: Mapping Socio-Environmental Changes Through Hybrid Geographic Information Technologies" Land 14, no. 8: 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081576

APA StyleDixit, M., Danilović Hristić, N., & Stefanović, N. (2025). Counter-Cartographies of Extraction: Mapping Socio-Environmental Changes Through Hybrid Geographic Information Technologies. Land, 14(8), 1576. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14081576