Abstract

Given the significant shifts in rural labor mobility patterns and their continuous influence on the transformation of the land factor market, it is crucial to understand the relationship between labor factor prices and land factor prices. This understanding is essential to keep land factor prices within a reasonable range. This study establishes a theoretical framework to investigate how migrant workers’ return shapes land price formation mechanisms. Using 2023 micro-level survey data from eight counties in Jiangsu Province, China, this study empirically examines how migrant workers’ return affects land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms through OLS regression and instrumental variable approaches. The findings show that under the current pattern of labor mobility, the outflow factor alone is no longer sufficient to exert substantial downward pressure on land transfer prices. Instead, the localized return of labor has emerged as a key driver behind the rise in land transfer prices. This upward mechanism is primarily realized through the following pathways. First, factor substitution effect: this effect lowers labor prices and increases the relative marginal output value of land factors. Second, supply–demand effect: migrant workers’ return simultaneously increases land demand and reduces supply, intensifying market shortages and driving up transfer prices. Lastly, the results demonstrate that enhancing the stability of land tenure security or increasing local non-agricultural employment opportunities can mitigate the effect of rising land transfer prices caused by the migrant workers’ return. According to the study’s findings, stabilizing land factor prices depends on full non-agricultural employment for migrant workers. This underscores the significance of policies that encourage employment for returning rural labor.

1. Introduction

China feeds 20% of the world’s population with only 9% of its arable land, producing 25% of global grain output. This achievement has not only helped China’s rural poor population completely resolve the basic survival issue of “having enough to eat,” but has also made an irreplaceable contribution to global food security governance and poverty alleviation efforts. However, in recent years, rapidly rising land transfer prices have significantly increased production costs for grain growers, severely squeezing profit margins. Data shows that from 2022 to 2024, the national average land transfer price surged from 697 yuan per mu per year to 896.7 yuan per mu per year, a sharp increase of 28.65% (Source: China Agricultural University’s China Land Policy and Law Research Center “Agricultural Land Transfer Insights” report; Note: 1 mu = 667 m2 or 0.667 ha). In 2023, the average net profit per mu of grain was only 75.14 yuan (Source: Summary of National Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data). This not only severely undermines producers’ enthusiasm for grain cultivation but also gives rise to risks of “abandoning farmland and breaching contracts,” thereby threatening China’s food security. Therefore, thoroughly investigating the causes of soaring land transfer prices and exploring countermeasures is of urgent practical significance for safeguarding national food security.

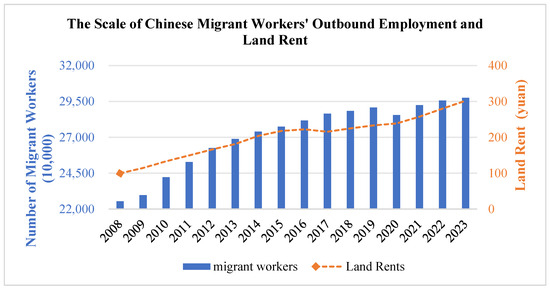

With the mass migration of agricultural labor to non-agricultural sectors, the academic community generally concurs that the land transfer market has experienced rapid development [1]. According to China’s migrant worker monitoring data, in 2023, the total number of migrant workers nationwide reached 297.53 million, accounting for 62.38% of the total rural population (Source: China Migrant Worker Monitoring Survey Report). During the same period, the total area of contracted farmland transferred nationwide exceeded 557 million mu, accounting for approximately 35.40% of the total area of farmland contracted by households (Source: Statistical Data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China). Theoretically, as rural labor shifts to non-farm jobs, fewer farm workers remain. This increases land supply in transfer markets, which should lower prices. However, contrary to theoretical expectations, as the number of rural laborers engaged in non-agricultural employment increases, land transfer prices have also risen (as shown in Figure 1). Between 2008 and 2023, the scale of the migrant worker population grew from 225.42 million to 297.53 million, an increase of 31.99%; Meanwhile, land costs rose from 99.62 yuan per mu per year to 302.16 yuan per mu per year, an increase of 203.31% (Source: Summary of National Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data). The question worth pondering and researching is: Why has the growth in rural laborers engaged in non-agricultural work not led to a drop in land transfer prices? Is it because non-agricultural employment has a limited impact on the land transfer market? Or because the internal structure of non-agricultural employment itself shows significant differences, making it impossible to directly assess its impact on the land transfer market based solely on the total number of non-agricultural jobs? Perhaps factors like the distance of non-agricultural employment matter—for example, the shift in rural labor from off-site non-agricultural work to local non-agricultural jobs, meaning the migrant workers’ return behaviors play a key role. Or maybe the impact of rural labor’s non-agricultural employment on the land transfer market requires specific conditions that have not yet been fully met.

Figure 1.

Trends in the Number of Migrant Workers and Land Rent Changes in China. (Data sources, China Migrant Workers Monitoring Report and National Abstract of Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data).

Under China’s system of collective land ownership, land serves as a crucial safeguard for farmers’ livelihoods. To protect farmers’ rights and ensure food security, China has carried out multiple reforms of the land tenure system. After 1978, the Household Responsibility System replaced collective unified management, realizing the separation of land ownership and contract management rights: ownership remained with the collective, while farm households obtained contract and management rights. Farmers could either cultivate land independently to secure subsistence grain and increase agricultural income, or transfer their management rights through market-oriented transactions to obtain property income [2]. To stabilize expectations for land use, the duration of land contracts was extended from 15 years to 30 years, with pilot programs further exploring extensions for another 30 years. With advancing urbanization, a large share of rural labor shifted to non-agricultural employment, and the proportion of part-time farming households increased [3]. In response, while maintaining collective ownership, the state promoted the reform of “separating three rights,” further dividing the contract and management rights. This reform both facilitated the concentration of land in the hands of new agricultural business entities and protected farmers’ basic contracting rights. Unlike countries with private land ownership, China strictly restricts land sales, allowing only the transfer or exchange of management rights. This not only optimizes resource allocation but also reinforces agriculture’s function as a buffer for employment, making farmland a “reservoir” that farmers can fall back on when non-agricultural employment fluctuates, and providing a cushion for returning rural laborers [4].

Return migration of labor is an important form of inter-regional population movement, referring to laborers who have been engaged in non-agricultural work outside the county for three months or longer returning to their place of household registration [5]. Monitoring data on China’s migrant workers show that between 2008 and 2023, the number of locally employed migrant workers increased from 85.10 million to 120.95 million, a growth of 42.28%. By region, compared with the end of 2019, by the end of 2023 the number of inter-provincial migrant workers had decreased by 1.57 million in the eastern region, 4.78 million in the central region, and 1.24 million in the western region (Source: National Bureau of Statistics, Monitoring Survey Reports on Migrant Workers in China for 2019 and 2023). This indicates a significant trend of return migration across all three major regions.

Although returning laborers may have various employment options, data show that 61.2% of unemployed returnees re-engage in agriculture [4]. More detailed surveys reveal that among all returning laborers, 12% are full-time farmers and 38% are part-time farmers [6]. This employment tendency is bound to exert new influences on the land transfer market. According to China’s Rural Operation and Management Statistical Bulletin, between 2009 and 2018, the number of households transferring out contracted farmland increased at an average annual rate of 10.7%, and the area of transferred-out land grew at an average annual rate of 21.8%. However, after 2018, these growth rates dropped sharply, falling to 1.6% and 2.8%, respectively (Source: China Rural Operation and Management Statistical Bulletin), reflecting the restraining effect of labor return migration on land transfer.

Regarding the impact of labor return migration on the land transfer market, existing studies have analyzed it from different perspectives. First, although returning laborers tend to engage in non-agricultural employment, their pattern of nearby employment reduces the spatial and temporal costs of agricultural production and improves the utilization of seasonally idle labor. Through these mechanisms, labor return migration reshapes the matching between people and land, which suppresses farmers’ willingness to transfer out land and may even encourage some households with stronger management capacity to expand their farming scale [7]. Second, labor return migration can also stimulate farmers with a comparative advantage in agricultural operations to transfer in land by broadening agricultural loan channels, increasing farmers’ risk-bearing capacity, enhancing participation in cooperatives and the utilization of agricultural machinery, and reducing participation in non-agricultural employment [7,8]. However, other research points out that the quantity and quality of returning labor cannot fully meet the labor demand for expanding household farming operations, and thus its impact on land transfer-in is limited [9].

Although existing studies have noted the impact of returning laborers on land resource allocation and have laid a theoretical foundation for this research, they have not fully explained why, against the backdrop of a continuous outflow of labor to non-agricultural sectors, land transfer prices have nevertheless continued to rise. When rural laborers work away from home, their physical separation from their place of residence—coupled with high transportation and time costs—makes it difficult for them to provide timely labor support for household farming. This spatial separation effectively severs their connection with the land, which could lead to an oversupply of land and suppress price growth. However, when laborers return to rural areas, whether they choose nearby non-agricultural employment or direct agricultural production, the shortened geographic distance enables them to flexibly participate in household farming activities and re-establish their connection with the land by optimizing the division of labor within the household.

This transformation prompts us to consider the following:

- (1)

- Does labor return migration, by reshaping the supply–demand relationship in the land transfer market, constitute an important reason for the recent slowdown in land transfer growth?

- (2)

- Under the new pattern of labor mobility, is there an intrinsic link between labor return migration and the continued rise in China’s land transfer prices? What mechanisms underlie this relationship?

This study will conduct an in-depth exploration of these core questions. Based on the above research questions, this study aims to achieve two core objectives. First, to systematically examine the impact of labor return migration on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms. Second, to analyze feasible pathways to address the land supply–demand imbalance and the resulting rise in land transfer prices after labor returns, from two dimensions: stabilizing land contracting rights and expanding local non-agricultural employment opportunities. To achieve these objectives, this study will use micro-survey data from Jiangsu Province, China, and apply both OLS regression models and instrumental variable methods for empirical testing.

Compared with the existing literature, the main contributions of this study are as follows: (1) Going beyond the traditional household perspective, this study systematically analyzes the impact of labor return migration on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms from the dual dimensions of the regional labor market and household decision-making. The findings reveal that rural labor return migration not only directly raises land transfer prices but also jointly drives price increases by lowering hired labor costs, reducing land supply, and stimulating competition in demand. In addition, this study explores two pathways to effectively regulate land transfer prices: increasing local non-agricultural employment opportunities and strengthening the stability of land contract rights. These findings enrich the literature on the diverse impacts of rural labor return migration and offer a new perspective for understanding the formation of land transfer prices. (2) This study adopts a rigorous empirical strategy to ensure the reliability of its conclusions. By introducing an instrumental variable approach, it effectively mitigates endogeneity issues and strengthens the credibility of the causal inferences. (3) In terms of data selection, this study takes 2019 as the baseline year for collecting labor return migration data, with a particular focus on observing labor return conditions in 2022. The data span both the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. This approach not only effectively avoids the self-selection bias of returning rural labor but also rules out the interference of historical population shocks (such as the Black Death) on agricultural product demand, thereby addressing limitations of Mankiw’s factor price theory in empirical testing. The findings of this study not only provide policy recommendations for optimizing non-agricultural employment strategies and building a stable land transfer price mechanism in China but also offer useful references for other developing countries seeking to promote coordinated reforms in labor and land factor markets.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Research on Off-Farm Employment and Farmers’ Land Transfer Behavior

Regarding the relationship between off-farm employment and farmers’ land transfer behavior, there are two main perspectives in the academic community: the “promotion hypothesis” and the “inhibition hypothesis”. Scholars who support the promotion hypothesis argue that off-farm employment promotes land transfer through a dual mechanism: on the one hand, the increase in off-farm employment opportunities raises the opportunity cost of engaging in farming; on the other hand, it broadens household income channels and reduces dependence on agricultural income, thereby facilitating land transfer-out [1,10].

In contrast, scholars who hold the inhibition hypothesis believe that off-farm employment does not necessarily lead farmers to transfer out their land. Such influence depends not only on the individual’s off-farm employment status but is also constrained by the off-farm employment situations of other household laborers [11,12]. Specifically, first, family caregiving responsibilities limit the complete transfer of labor, leading to a “part-time farming, part-time off-farm work” division of labor, which in turn inhibits land transfer-out [13]. Second, there are significant gender differences: compared with men, women’s off-farm employment exerts a stronger promoting effect on land transfer-out [14]. Moreover, the geographical radius of off-farm employment also matters [15]. Local off-farm employment, characterized by “leaving the land but not leaving the village,” makes it easier to combine farming and off-farm work, thus inhibiting land transfer-out [16]. For example, India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), by providing nearby public jobs during the slack farming season, has strengthened farmers’ tendency toward part-time farming [17]. In contrast, off-farm employment outside the locality, due to the high time and transportation costs of commuting between urban and rural areas, more readily promotes land transfer-out [10]. However, farmers’ risk-aversion motives may weaken this relationship. Because off-farm employment outside the village often involves uncertainty or risk, farmers tend to retain their land as a means of livelihood security. Even when government interventions reduce farmers’ perceived risks of off-farm employment—such as when the Bangladeshi government provided rural households with cash and credit incentives to encourage labor migration—return-home subsidies during the busy farming season instead reinforced farmers’ part-time farming mode and inhibited land transfer-out [18]. Furthermore, when migrant laborers working away from home fail to obtain stable employment security or adequate rights, the pull of local off-farm employment opportunities can further reduce smallholders’ willingness to exit agricultural production [19].

2.2. Research on Labor Mobility and the Relationship with Factor Prices

The impact of labor mobility on factor prices is mainly reflected in two aspects: labor and land. First, regarding the impact on labor prices, studies show that an inflow of migrant populations significantly increases the labor supply in the destination areas. When the demand function remains relatively stable, this leads to a decrease in the equilibrium wage level and thus a decline in labor factor prices. For example, following hurricane events impacting Florida in the southeastern United States, labor outmigration reduced the regional employment by 2.37%, which in turn pushed up labor market prices and increased farmers’ incomes by 1.92 [20]. Similarly, an increase in internal migration inflows in Brazil resulted in declining wages in the informal sector [21]. This price-transmission mechanism also underpins the core logic of industrial location choices in new economic geography: enterprises tend to shift industries toward low-wage areas with high population concentration [22]. It is noteworthy that the wage gap between the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors can induce rural laborers to migrate to urban or non-agricultural sectors. Such structural mobility leads to a shortage in agricultural labor supply, driving up agricultural labor prices and stimulating technological change [23]. For instance, nearly a century ago in the southern United States, labor shortages caused by African American migration led to rising wages for agricultural workers, which spurred local agricultural technological progress and changes in farming patterns [24]. Likewise, countries such as China and India have experienced labor substitution by machinery due to rising hired-labor costs driven by outmigration of agricultural laborers [25].

Second, regarding the impact on land prices, existing studies mainly focus on the impact of labor mobility on the prices of construction land. Taking housing prices as an example, on the demand side, population agglomeration directly drives up housing demand; on the supply side, under rigid constraints of land-use regulation and construction costs, insufficient housing supply elasticity further amplifies upward pressure on housing prices in labor-concentrated areas [26]. Conversely, labor outmigration tends to lower housing prices or rents, a mechanism confirmed by studies examining the impact of natural disasters on labor migration in the United States [27]. Similarly, industrial prices in urban areas also rise as labor inflows intensify competition [28]. In contrast, research on the impact of labor mobility on agricultural land prices is relatively scarce. For example, a study based on Ethiopia, which explored the role of land rental markets in addressing population pressure and land scarcity in Sub-Saharan Africa, found that land scarcity significantly drives up rent levels [29]. However, that study only focused on the impact of land scarcity on land prices and did not further analyze the transmission mechanism between population changes and the quantity and price of land factors. Likewise, a study on China found that cross-regional off-farm employment reduced land transfer prices and led to farmland abandonment [30]. Unfortunately, that study merely regarded this finding as a mechanism to explain land abandonment, without systematically elaborating on the intrinsic mechanism through which labor mobility affects land transfer prices. These research gaps highlight the necessity of further investigating the relationship between labor mobility and agricultural land prices.

2.3. Research on the Factors Influencing Land Transfer Prices

Academic studies on the factors influencing land transfer prices can be systematically categorized into four main areas. First, from the perspective of land quality characteristics, research shows that plots with high soil fertility, well-developed irrigation conditions, flat terrain, and contiguous layouts often command higher rent premiums because they reduce production costs and increase output efficiency [31]. Such land not only exhibits significant economies of scale, but its locational advantages—such as proximity to markets—further strengthen demand from land operators [30]. In contrast, fragmented and infertile plots, due to difficulties in mechanized farming and high operating costs, commonly face low rents or even abandonment [32].

Second, from the perspective of the land titling system, there is no consensus in the academic community. Mainstream studies argue that land titling, clarifying property rights boundaries and enhancing transaction security, significantly increases land transfer prices [33]. However, subsequent research has revealed the contextual dependence of this effect; for example, the effectiveness of titling may be influenced by historical land readjustments. Geng et al. further confirmed that farmers with readjustment experience tend to exhibit a stronger willingness to increase rents due to heightened awareness of property rights [34]. Nevertheless, studies by Xu et al. and Jiang et al. challenge this view, suggesting that land titling has not substantially affected land transfer prices, implying a potential overestimation of policy effects [35]. With the deepening of the “separation of three rights” reform, the effect of strengthened property rights has created new drivers of rent increases by enhancing operational stability and promoting investment in public goods [36].

Third, from the perspective of policy impacts such as agricultural subsidies, most studies have confirmed that subsidies generate rent-increase effects through income capitalization mechanisms. From Floyd’s classical theory to the empirical studies of Goodwin et al., significant variation has been observed in subsidy capitalization rates (25–80%) [37,38]. The degree of capitalization is influenced by subsidy types, entitlement ownership, and regional characteristics, with subsidies directly granted to operators having a more pronounced rent-increase effect [39]. Recent studies have begun to focus on the interaction between property rights and subsidies, exploring the inequality of capitalized benefits distribution among different rights holders [40].

Finally, regarding the role of market competition in the formation of land transfer prices, existing studies have paid insufficient attention to this aspect. Most research has focused on external factors affecting market competition, such as the development of digital technologies [41] or the impact of relaxed credit constraints on land demand [42], while few have systematically examined the intrinsic formation mechanisms of land transfer prices. Only a handful of studies have noted that agricultural outsourcing services can raise land transfer prices by altering the supply and demand structure in the land transfer market [43]. It is worth noting that although technological progress is a key variable affecting land transfer prices, labor remains the most direct input in agricultural production and the main agent in allocating other production factors, making its impact on land prices even more direct. From a causal chain perspective, technological change itself is an adaptive response to labor shifts; therefore, the movement of labor factors is the fundamental driver affecting land prices.

Existing research provides a theoretical foundation for examining the impact of returning labor on land transfer prices, but studies on the underlying mechanisms remain insufficient. As a core factor in agricultural production, agricultural labor not only directly participates in production processes but also plays a key role in allocating other production factors. The phenomenon of labor returning to rural areas both alleviates the agricultural labor shortages caused by rural–urban migration and inevitably brings about changes in the market for agricultural production factors—particularly having a profound impact on the supply–demand structure and price-formation mechanisms of land. Based on this, this study aims to systematically analyze the following key issues: (1) What is the direct impact of returning labor on land transfer prices? (2) Through what pathways does returning labor affect the formation of land transfer prices? (3) How can the upward pressure on land prices caused by returning labor be mitigated? A thorough exploration of these questions will not only deepen the theoretical understanding of the linkage mechanism between labor and land factors but also provide a scientific basis for countries at different stages of development to formulate differentiated land policies that align with the characteristics of labor mobility.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypothesis

The dual economy theory suggests that higher wages in the modern industrial sector, compared to the traditional agricultural sector, drive the large-scale migration of agricultural labor to urban areas or non-agricultural sectors. This labor migration not only promotes the optimal allocation of labor factors across different sectors, enhancing labor productivity and overall economic efficiency, but also facilitates the optimal allocation of land factors among different entities, improving land productivity and the overall efficiency of the agricultural economy [44,45]. However, migrant workers’ return may alter this pattern. First, migrant workers’ return leads to changes in the quantity and price of labor supply and demand in a region. According to Mankiw’s analysis of the impact of the Black Death in Europe on the quantity and price of labor and land factors, the Black Death caused a significant reduction in Europe’s population, making labor extremely scarce and reducing the number of workers available for farming. In this situation, landowners struggled to find enough labor to maintain traditional agricultural labor intensity, leading to an increase in the relative supply of land and a corresponding decrease in land rent. Similarly, under the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large number of rural laborers who had previously been engaged in non-agricultural employment outside their hometowns returned to their local areas. This increased the supply of labor in the return areas’ labor markets while also increasing the number of laborers available for farming, thereby reducing the supply of land in the region. As a result, labor migration may lead to a significant decline in the price of labor (i.e., workers’ wages) in the return areas, while the price of land in the land market may significantly increase.

Secondly, migrant workers’ return has led to changes in the supply and demand relationship of land factors in the region. On the one hand, returning migrant workers allocate their time between the non-agricultural and agricultural sectors based on their comparative advantages and the maximization of household income. However, regardless of whether returning migrant workers choose to work in the non-agricultural sector, the distance they travel from home is decreasing. This is more evident in the fact that returning migrant workers are increasingly seeking non-agricultural employment opportunities within a smaller geographical radius, and the likelihood of their entire families relocating or the adequacy of their non-agricultural labor transfers is decreasing. Such a state of unemployment or nearby employment not only supplements household agricultural production but also mitigates the seasonal idleness of labor arising from the seasonal and cyclical nature of farming, enabling fuller and more efficient use of household labor time. On the other hand, the return of labor drives down regional hired-labor wages, thereby reducing the opportunity cost for farmers to work off-farm or to be employed by other agricultural operators. This raises the relative returns to self-farming. Moreover, under self-employment, farmers can fully capture the marginal product of their own labor without accepting the discount imposed by market wages. As a result, self-employed farming enables farmers to maximize the returns to their labor, which strengthens smallholders’ demand for their own land and suppresses the supply of land to the market. Therefore, labor return not only fosters the emergence of mixed farming models but also allows farmers, through self-employment, to achieve a Pareto improvement in the allocation of labor resources—choosing a production mode that yields higher returns under given market wage conditions—thereby reducing their willingness to exit agricultural production and decreasing the supply of land in the land transfer market.

Additionally, especially when rural laborers face non-agricultural unemployment or job instability due to external shocks, and when the primary source of household income is lost but fixed expenses remain, even if small-scale farmers withdraw from agricultural production and transfer their land, they may still return to agriculture. This is primarily due to the fact that land serves as a final destination for returning migrant workers, fulfilling the functions of employment security by smoothing out the timing of rural labor force employment and income security by retaining agricultural operating income, and even acting as a form of unemployment insurance, providing the most basic livelihood protections for households [46]. Meanwhile, the return of labor increases the supply in the local labor market, which, under relatively stable demand, exerts downward pressure on wages and significantly reduces the labor costs of large-scale farming operators. These changes in labor factor prices generate a dual market effect. On the one hand, the reduction in labor costs effectively alleviates the long-standing constraints on labor input faced by large-scale operators, improving the labor-factor allocation in their production functions. On the other hand, the cost savings achieved by large-scale operators are transformed into notable economies of scale, which in turn induce additional demand for land factors. Under conditions of low land-supply elasticity, this demand shock transmitted from the labor market to the land market shifts the land demand curve to the right, causing the equilibrium price of land factors to move upward along the supply curve, ultimately manifesting as a systematic increase in land transfer prices.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H1.

Migrant workers’ return will cause land transfer prices to rise.

H2.

Migrant workers’ return will cause land transfer prices to rise by lowering labor factor prices, increasing demand in the land transaction market, and reducing supply in the land transaction market.

Stable land rights not only reduce the risk of farmers losing their land and increase the expected returns from agricultural production but also increase opportunities for rural labor to transfer to non-agricultural sectors and for land to be transferred. When land is illegally occupied or infringed upon, this system provides farmers with clearer legal protection, enabling them to protect their rights in accordance with the law and effectively alleviating their concerns about losing their land. This encourages them to participate more actively in non-agricultural industries, achieving diversified labor transfer and effective land circulation. Additionally, the institutionalized form of land rights management under national property rights provides formal legal definitions and protections for land contracting rights. This measure helps eliminate farmers’ concerns about potentially losing their contracting rights after transferring land, thereby increasing their willingness to transfer land [47]. Meanwhile, the stability of operating rights is crucial for ensuring that large-scale operators can make long-term investments in agricultural production. The increase in land value resulting from such investments reinforces the capital attributes of land, thereby enhancing the land-related asset income of contracting households [48]. Therefore, even when external non-agricultural employment opportunities are scarce, or when major unforeseen events force migrant workers to return to their rural homes, stable property rights still guarantee the residual rights in agricultural production (i.e., differential rent II generated by investment appreciation gains). This means that the land can be priced and linked to its economic value in the market. As a result, farmers are still motivated to transfer their land to share in the land appreciation gains and earn rental income.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

H3.

Stable property rights expectations can weaken the effect of migrant workers’ return on land transfer price increases.

Increasing local non-agricultural employment opportunities plays a crucial role in enhancing the re-employment of returning migrant workers, reducing local non-agricultural unemployment, or increasing employment. On the one hand, when faced with external shocks or other factors leading to migrant workers returning to their hometowns to seek employment or choose new jobs, retaining land use rights is a rational response by farmers to self-protect in the absence of economic income security [3]. Conversely, if the returning area creates more non-agricultural employment opportunities, the returning migrant workers will experience shorter periods of unemployment and have broader job selection options. Their lack of economic income security can be promptly and effectively addressed, reducing their reliance on the land’s survival security function. This will help reduce their likelihood of returning to farming, promote or continue land transfers, and thereby increase the supply in the land transfer transaction market. On the other hand, returning migrant workers, i.e., individuals who previously engaged in non-agricultural work outside their hometowns, have possessed relatively higher non-agricultural employment skills or technical capabilities [49]. This may, to some extent, create a displacement effect on local non-agricultural laborers (especially low-skilled laborers), leading to forced unemployment or job downgrades for rural laborers who previously had been working in non-agricultural work locally. However, when local non-agricultural employment opportunities are sufficient, they can both maintain the stability of the existing non-agricultural employment population and fully absorb returning labor for re-employment. This creates favorable conditions for rural labor to fully realize non-agricultural employment and has a positive promotional effect on land transfers. Under this backdrop, the total supply in the land transfer market will significantly increase, thereby exerting a certain regulatory effect on land transfer prices.

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following research hypothesis:

H4.

Increasing local non-agricultural employment opportunities can weaken the effect of migrant workers’ return on land transfer price increases.

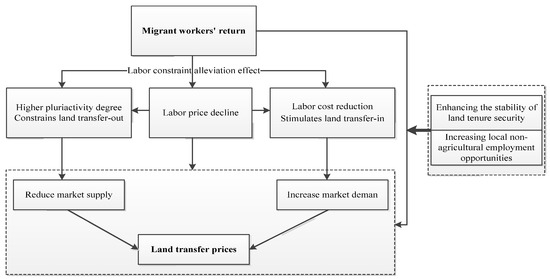

Based on the above analysis, this study constructs a theoretical framework analyzing “worker return migration’s impact on land transfer prices” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theoretical framework of worker return migration’s impact on land transfer prices. (Source: Compiled by the author).

4. Data Sources, Model Construction, and Variable Selection

4.1. Data Sources and Sample Description

Jiangsu lies in the central part of the Yangtze River Delta. It is one of China’s eastern coastal provinces. It has excellent natural endowments, with a total land area of approximately 10.76 million hectares. The terrain is flat, with an average elevation of less than 50 m. It has a subtropical monsoon climate, with an annual average temperature of 17.5 °C and an annual average precipitation of 1055 mm. The mild climate and flat terrain provide ideal conditions for agricultural production. The total arable land area in the province reaches 4.58 million hectares, with an average of approximately 0.057 hectares per capita. Over 70% of this land is flat, covering an area exceeding 7 million hectares. Economic development varies significantly across regions. The southern part of Jiangsu Province is geographically adjacent to Shanghai. This proximity has enabled it to deeply integrate into the Yangtze River Delta integration development. As a result, it has formed a modern industrial system. This system is rooted in advanced manufacturing and dominated by export-oriented high-tech industries. Consequently, it has become one of the fastest-growing regions in eastern China. In contrast, while the northern part of Jiangsu currently lags behind in economic development, it actively participates in industrial transfer from the southern region through joint development zones, focusing on cultivating industries such as electronics and high-end textiles. Additionally, the northern part of Jiangsu has vast plains and abundant water and thermal resources. It has established multiple national-level commodity grain bases. These bases play an irreplaceable strategic role in ensuring national food security and advancing agricultural modernization.

The data used in this study were obtained from a household micro-survey conducted by the research team in 2023 across eight counties in Jiangsu Province, China. Given the significant differences in economic development levels and rural social structures among the three major regions of northern, central, and southern Jiangsu, a multi-stage random sampling principle was adopted to ensure regional representativeness of the sample. Samples were selected from the three regions in a 4:2:2 ratio, three townships were selected from each county, three villages from each township, and approximately 20 households from each village, ultimately forming a sample database of 1472 households covering 24 townships and 72 villages across the eight counties. The survey questionnaire collected information on various aspects of household agricultural operations, family life, out-migration for employment, household assets, and social relationships in 2019 and 2022, which meets the requirements of this study. This study primarily examines the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices. After removing missing and outlier values from the sample, the final dataset includes 1067 transferred land plots across 72 villages, along with corresponding plot characteristics, village characteristics, household characteristics, and individual farmer characteristics. It should be noted that differences in model settings and variable selection cause the effective sample size to vary in subsequent analyses.

4.2. Model Setting

This study aims to examine the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms. To this end, we first establish an estimation model for the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices. Specifically, as follows:

In Equation (1), the dependent variable is land transfer price. The core explanatory variable L is the migrant workers’ return within the village. X is a matrix composed of control variables such as plot characteristics and village characteristics, specifically including: plot area, distance from home, soil type, soil fertility, slope, irrigation conditions, plot type, summer crop type, autumn crop type, connectivity with managed plots, and land transfer form; village outsourcing service level, village grain production income, village annual per capita net income, arable land abundance, and land fragmentation. Additionally, regional fixed effects are controlled for. is the constant term, is the coefficient to be estimated, is the matrix composed of control variable coefficients, and is the random disturbance term.

Second, to examine whether migrant workers’ return affect land factor prices through the channels of reducing labor factor prices, increasing farmers’ demand for land, and reducing the supply of land in the land transaction market, this study will conduct a mechanism test based on the aforementioned theoretical analysis. Since the traditional three-step verification method has unavoidable endogeneity issues [50], this study adopts a two-step verification method, which tests the impact of migrant workers’ return on the aforementioned mechanism variables based on Equation (1). The specific model is as follows:

In Equations (2)–(4), , , are the three mechanisms through which migrant workers’ return affects land transfer prices: migrant workers’ return reduces the price of labor as a factor of production, increases farmers’ demand for land for operations, and reduces the supply of land in the land transaction market. The price of labor as a factor of production is characterized by the price at which village-scale farming households hire labor, and the corresponding core explanatory variable L is the extent of migrant workers’ return within the village. The demand for land by households is assessed by examining changes in the area of land transferred in by households within three years of migrant workers’ return, thereby evaluating household demand for land over a longer timeframe. The core explanatory variable L corresponding to this is the household migrant workers’ return situation. The supply in the land transaction market is examined by observing the key nodes of labor return, specifically the outflow situation in the rural land transfer transaction market after 2019. The corresponding core explanatory variable L is the migrant workers’ return within the village. In Models (2) to (3), X is a matrix composed of control variables such as village characteristics and household characteristics, specifically including the average daily wage level of bricklayers in the village, the number of enterprises in the village, the annual per capita net income of the village, the level of outsourced services in the village, the grain production income of the village in 2019, the degree of aging in the village, the distance of the village from the county seat, and the proportion of labor force to the total population in the village; household agricultural labor force size, household financial constraints, household annual net income, and household head age. The control variables in Model (4) are consistent with those in Model (1). , , and are constant terms, , , and are the coefficients to be estimated, , , and are the random disturbance term.

4.3. Variable Selection

4.3.1. Dependent Variables

The dependent variable of this study is the land transfer price, which, following Qiu et al., is measured using the survey item “the rent per mu of land transferred out in 2022” [51]. Rent, as the equilibrium price formed through the interaction of supply and demand in the land market, is the price paid by land users to obtain operating rights through leasing or contract farming. This method has been widely adopted in studies related to land transfers. This indicator can effectively be combined with explanatory variables and control variables to gain insights into farmers’ decision-making logic and the factors influencing land element market prices.

4.3.2. Core Explanatory Variables

The core explanatory variable of this study is the migrant workers’ return. First, drawing on relevant research, this study defines the return of migrant workers as follows: after working for three months or longer in non-agricultural sectors outside their county seat, migrant workers return to their county of registration [52]. Second, the study compares the proportion of the village labor force engaged in off-farm employment outside the county in 2022 versus 2019 to estimate the scale of labor return to their registered (hukou) counties in 2022. Therefore, the core explanatory variable in this study is the village-level labor return ratio. Additionally, a binary dummy variable indicating whether a village has returning laborers is used in subsequent robustness tests. This resembles the variable features used in Zhou et al.’s study [2]. Finally, based on the above definition, this study identifies the return of family labor in 2022 by comparing the changes in the employment locations of each family member between 2022 and 2019. This core explanatory variable will serve as a key indicator for verifying the land demand transmission mechanism, used to validate the intrinsic link between the return of family labor and land demand in the theoretical model.

4.3.3. Mechanism Variables

This study selects labor factor prices, land market demand, and land market supply as mechanism variables to systematically examine how the migrant workers’ return affects land transfer prices. Specifically, first, labor factor prices are measured using the average daily wage level of hired labor in village-scale farming households. This approach quantifies the marginal cost of unit labor input to characterize labor factor prices. Second, for land market demand, the difference between the area of land transferred in by the household in 2022 and that in 2019 is used as a proxy variable to determine whether the household has transferred in more land. Finally, for land market supply, focusing on the key time points of labor return, the area of land transferred out after 2019 is used as a proxy variable.

4.3.4. Control Variables

Building on the core variables mentioned above, and drawing on relevant research [43,51], this study controls for variables that may influence land transfer prices at two levels: (1) Plot level, including plot area, distance from home, soil type, soil fertility, slope, irrigation conditions, plot type, summer crop type, autumn crop type, connectivity with managed plots, and land transfer form. (2) At the village level, including village outsourcing service levels, village grain production income, village annual per capita net income, arable land abundance, and land fragmentation.

4.3.5. Instrumental Variables

Given the potential endogeneity issues in the theoretical model, this study selects “the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic within a region” as an instrumental variable for migrant workers’ return. As a major sudden public health emergency, the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic is not determined by individual behavior or the current social environment. Additionally, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic constituted a major external shock to the global labor market, resulting in varying degrees of negative impacts on employment conditions across countries [53]. The impact on China’s labor market exhibited distinct heterogeneous characteristics among different groups, with migrant workers facing greater shocks compared to local urban laborers, prompting their return to their places of origin [54]. Therefore, the pandemic shock as a variable effectively meets the two necessary conditions for instrumental variable exogeneity and correlation with endogenous variables.

The variable definitions and descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable settings and descriptive statistics.

5. Empirical Results and Analysis

5.1. Analysis of Baseline Regression Results

This study aims to resolve the paradox of “why land transfer prices continue to rise synchronously against the backdrop of sustained labor shifts to non-agricultural sectors.” To systematically analyze this phenomenon, the study first clarifies the differential impacts of two labor mobility patterns—“long-distance outward migration” and “short-distance return migration”—on land transfer prices, thereby identifying the key drivers of rental price fluctuations. Building on the existing analytical framework, this section introduces the “proportion of non-agricultural employment outside the county” as a proxy variable for village labor outflow and compares its estimated results with those of the labor return variable. This approach helps to more clearly delineate the differential effects of labor mobility in different directions on land transfer prices, laying the groundwork for further investigation into the impact of labor return migration on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms.

The estimation results, as shown in Column (1) of Table 2, reveal that the coefficient estimate for the labor outflow variable is −0.00013 but fails to pass the significance test. This indicates that the negative effect of cross-county labor outflow on land transfer prices is not statistically significant. In stark contrast, the results in Column (2) show that the labor return variable is significantly positive at the 5% level. This comparative finding carries important theoretical implications: First, it confirms the structural shift in China’s rural labor mobility patterns, where the traditional labor outflow model’s dampening effect on land transfer prices has weakened. Second, and more importantly, localized labor return migration has emerged as the dominant factor driving the increase in land transfer prices. Based on this finding, the subsequent analysis will focus on dissecting the intrinsic mechanisms through which labor return migration influences land transfer prices.

Table 2.

Estimated results of the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices.

To address potential endogeneity issues in the model examining the relationship between labor return migration and land transfer prices, this study introduces the “COVID-19 pandemic shock” as an instrumental variable for migrant workers’ return and further employs the instrumental variable method (IV-2SLS) for estimation. The regression results are shown in Column (3). First, the DWH test of the model passed the significance test, confirming the existence of endogeneity issues in the model. Second, the estimated coefficient of the instrumental variable in the first-stage regression results is significant at the 1% statistical level, and the F-value of the joint significance test in the land transfer price model is greater than the empirical value of 10, indicating that the instrumental variable selected in this paper does not suffer from weak instrumental variable issues. After accounting for endogeneity, the migrant workers’ return variable remains significant with a positive coefficient. According to factor demand theory, the return of rural labor increases the supply of labor factors in the agricultural production sector, leading to a decrease in labor prices. Meanwhile, as the number of returning laborers increases, land factors become relatively scarce, causing their prices to rise, reflecting that the increase in labor factors intensifies the market competitiveness of land resources. Thus, hypothesis H1 is validated.

5.2. Robustness Test

This study tested the sample using three methods: replacing the core explanatory variable, replacing the sample, and adding control variables in order to verify the robustness of the baseline regression results.

5.2.1. Replacing the Core Explanatory Variable

For robustness testing, this study replaces the continuous variable of village labor return ratio with a binary dummy variable indicating whether the village experienced labor return. The estimation results are shown in Table 3, Column (1). The migrant workers’ return still has a significant positive impact on land transfer prices, and the empirical results are consistent with the benchmark regression results, indicating that the baseline regression results are robust.

Table 3.

Results of robustness tests.

5.2.2. Replacing the Sample

The concentrated land transfer model, dominated by village collectives and new agricultural operating entities in rural China, is becoming the primary trend. Under this model, land transfer contracts are typically long-term, and the transfer parties agree in advance on the land transfer price, which cannot be adjusted during the contract period. Additionally, the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices may exhibit lag effects. Therefore, this study attempts to conduct robustness tests using land rent from newly transferred plots in 2022 as the sample. The estimation results, shown in Table 3, Column (2), indicate that migrant workers’ return still has a significant positive impact on land transfer prices. The empirical results are consistent with the benchmark regression results, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression results.

5.2.3. Adding Control Variables

To avoid bias caused by omitting key explanatory variables, this study attempts to further introduce variables related to land investment and institutions. Specifically, land investment increases the income of land operators, with part of this income being converted into land rent in the form of differential rent [55]. To control for the impact of investment, this study uses whether the household has invested in the land parcel to characterize its influence. After controlling for the impact of land parcel investment, the estimation results in Table 3, Column (3), still support the conclusions of this study. Additionally, land rights clarification enhances the stability of land property rights by eliminating the ambiguity and instability of land property boundaries, thereby increasing land transaction prices [56,57]. To control for the impact of the land title clarification system, this study uses the number of years since village-level land title clarification to characterize the impact of the system. After controlling for the impact of land title clarification, the estimated results in Column (4) still support the conclusions of this study. Furthermore, when both variables are simultaneously introduced into the baseline regression model, and after controlling for the impacts of land investment and the land title clarification system, the estimated results in Column (5) are consistent with the baseline regression results, indicating the robustness of the baseline regression results.

5.3. Analysis of the Mechanism of Action

Since the traditional three-step verification method may have endogeneity issues in practical applications, we draw on the approaches of previous scholars to further identify the mechanism through which migrant workers’ return affects land transfer prices. The estimation results are shown in Table 4, Columns (1) to (3). First, the estimation results in Column (1) indicate that, at the 5% statistical significance level, migrant workers’ return has a significant negative impact on labor factor prices. This empirical finding reveals that, under unchanged labor demand, the increase in regional labor supply caused by migrant workers’ return directly leads to a decline in labor factor prices. This discovery aligns closely with the neoclassical economic theory of factor prices, which posits that factor prices are determined by their scarcity: when factor supply is less than demand, prices rise, and when factor supply exceeds demand, prices fall.

Table 4.

Results of mechanism of action testing.

Second, the estimation results in Column (2) show that, at the 10% level of statistical significance, the return of household labor has a significant positive impact on the increase in the area of land transferred in. This empirical finding reveals the intrinsic link between migrant workers’ return and land demand: when migrant workers return to their household registration locations, expanding the land cultivation area to maximize household total income becomes a rational decision for returning households. This behavior not only directly stimulates the land demand of returning farming households but also, through the transmission mechanism of the land transfer market, exacerbates the demand-side pressure on the regional land market, ultimately driving a significant increase in land transfer prices.

Finally, the estimated results in Column (3) indicate that, at the 5% level of statistical significance, the migrant workers’ return has a significant negative impact on land supply. This empirical finding reveals the intrinsic connection between the labor market and the land transfer market: as the proportion of rural labor returning to villages increases, farm households adjust their land resource allocation strategies based on livelihood security needs, reinforcing their tendency to self-operate land and suppressing their willingness to transfer land, ultimately leading to a contraction in the supply of land in the land transfer market. Therefore, the migrant workers’ return increases land demand while reducing land supply, leading to a shortage in the land transaction market and consequently driving up land transfer prices.

This study further found, based on survey data, that, compared with 2019, among farmers who reduced their land cultivation area in 2022, 10.48% were forced to do so because the contracting party reclaimed the land. At the same time, among farmers who answered “yes” to the question of whether they expected to increase their land cultivation area in the coming years, 34.17% cited a reduction in non-agricultural employment opportunities as the main reason for increasing their land cultivation area in the future. These two sets of data also indirectly validate the significant influence of the labor market on the price formation mechanism of the land transfer market.

Based on the above analysis, the migrant workers’ return not only indirectly raises land transfer prices by lowering labor costs but also exacerbates the imbalance between supply and demand in the land transfer market by increasing demand and reducing supply, thereby driving up land transfer prices. Thus, hypothesis H2 is validated.

5.4. Analysis of Regulatory Effects

Stable expectations regarding land contracting rights are expected to effectively alleviate concerns about labor migration to non-agricultural sectors. This stability will reduce uncertainty in land transfer processes. It will also increase the supply in the land transfer market. Ultimately, these changes are expected to regulate land transfer prices [34]. To explore this issue, this paper further introduces the variable “whether the village has notified farmers of the regulation that ‘after the second round of land contracting expires, it will be extended for another 30 years’.” This variable is used to characterize farmers’ expectations regarding the stability of their contracting rights. The estimation results are shown in Table 5, Column (1). At the 1% statistical significance level, the interaction term between labor return and land rights stability expectations has a significant negative impact on land transfer prices. This indicates that land rights stability expectations have a negative moderating effect on the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices. In other words, land rights stability expectations can mitigate the upward pressure on land transfer prices caused by migrant workers’ return. Thus, hypothesis H3 is validated.

Table 5.

Results of moderation effect analysis.

The development of the local informal labor market can effectively absorb returning labor and rural surplus labor. This enhances the adequacy of non-agricultural employment transitions for household labor [58]. It encourages such households to abandon agricultural production and engage in non-agricultural work. This, in turn, increases land supply and regulates land transfer prices. To explore this issue, this study further introduces the “development level of the local casual labor market” to characterize the development level of the local informal employment market. Specifically, the method involves dividing the proportion of labor force engaged in casual work near the village into three levels: low, medium, and high. The higher the level, the higher the development level of the casual labor market, and vice versa. This study defines casual work as low-skilled work with flexible working hours and piece-rate pay.

The estimation results are shown in Table 5, Column (2). At the 1% significance level, the interaction term between labor return and the development level of the local casual labor market has a significant negative impact on land transfer prices. This indicates that the development level of the local casual labor market has a negative moderating effect on the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices. In other words, as the development level of the local casual labor market increases, the upward pressure on land transfer prices caused by migrant workers’ return is mitigated. Thus, hypothesis H4 is validated.

Based on the above analysis, strengthening expectations of land tenure stability can effectively alleviate the pressure of rising land transfer prices caused by the migrant workers’ return. Similarly, increasing non-agricultural employment opportunities in the local casual labor market can also effectively mitigate this pressure.

6. Discussion

Against the backdrop of continuously rising land transfer prices, high unit production costs, and declining international competitiveness of Chinese agricultural products, this study systematically analyzes the internal mechanisms driving the rise in land transfer prices. It also explores methods or pathways to regulate these prices. This research is of great significance for reducing agricultural production costs and enhancing producers’ enthusiasm for grain production.

In recent years, the interplay between the labor market and the land market has become a key focus of research both domestically and internationally. This study shares similarities with existing research on related topics but also introduces new perspectives. Empirical results indicate that the migrant workers’ return significantly increases land transfer prices. This finding not only extends existing research on the impact of labor return on land transfer, but more importantly, it fills a research gap in analyzing the formation mechanism of land transfer prices from the perspective of labor.

This study finds that labor return significantly increases land transfer prices. The root of this phenomenon lies in the structural shift in rural labor mobility under the evolving urban–rural development pattern—namely, a gradual transition from “long-distance cross-regional outflow” to “localized short-distance return.” Data from migrant worker monitoring between 2010 and 2024 confirm this trend: the increase in local migrant workers reached 136.16%, significantly higher than the 116.53% increase in out-migrating workers. Moreover, the rapid growth of locally employed migrant workers shows a spatial–temporal consistency with the upward trend in land transfer prices. This structural adjustment in the spatial allocation of labor affects land transfer prices through three pathways: (1) by reducing regional labor prices, (2) by reducing regional land supply, and (3) by stimulating regional land demand. These factors combine to produce a strong upward pressure on land transfer prices. Notably, this positive price effect not only fully offsets any potential price-decreasing effects caused by labor outflow but also becomes a key driver of sustained increases in land rents at the macro level.

Mechanism analysis: First, this study finds that labor return significantly lowers labor prices. The reason is that returning labor substantially increases the supply of labor in the destination area; under relatively stable labor demand, an increase in supply inevitably leads to a decline in the equilibrium wage level. This conclusion aligns with the findings of Diodato et al., who, based on data on migrant labor return in Mexico, also observed a suppressing effect of labor return on local wages [59]. However, a cautionary note is warranted: the wage-reducing effect brought about by labor return may trap farm workers in poverty and hinder the adoption of labor-saving technologies. The study by Martin et al. further confirmed this negative effect [60].

Second, this study finds that rural labor return significantly reduces the supply of land. The reasons are as follows: on the one hand, labor return pushes down regional wage levels, reducing farmers’ opportunity cost of off-farm employment, thereby increasing the relative returns to self-farming. Under a self-employment model, farmers can capture the entire marginal product of their labor, which strengthens their demand for self-cultivated land. On the other hand, off-farm work is often located far away, with high transportation and time costs, making it difficult to replenish household agricultural labor in a timely manner. After labor return, whether through nearby non-farm employment or direct farming, shorter geographic distance enables timely participation in household production and optimizes internal labor division, thus reducing the willingness to transfer out land and suppressing land market supply. This is consistent with the conclusions of Kang et al., who explored the relationship between employment distance and farmers’ land transfer-out behavior in the context of rural labor return [9]. It is worth noting that this finding differs from the conclusions of Kang et al. in their study on labor return and farmers’ land transfer-out under different employment choices [6]. This difference may stem from heterogeneity in research periods: the present study focuses on land supply under the wave of labor return following the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas previous studies did not distinguish between the historical stock of land transfer-out and newly added flows, leading to opposite conclusions.

Third, this study finds that labor return significantly increases land demand. The reasons are twofold: on the one hand, labor return effectively alleviates labor shortages in agricultural production, prompting households with returning labor to expand their land operation scale; on the other hand, the increased labor supply in the local labor market reduces hired labor costs, and this cost advantage is converted into substantial economies of scale, further encouraging large-scale operators to continuously expand their land operation area. This finding is consistent with the results of Zhou et al. and Huang et al., who examined the impact of returning migrant workers on land transfer-in in China [7,8].

The impact of rising land transfer prices exceeds expectations, as confirmed by many studies as follows: First, the trend of land capitalization may exacerbate social stratification. Rising prices gradually push poor rural households out of the land transaction market, leading to the concentration of land resources in the hands of the wealthy [61]. This not only creates a food security crisis amid the process of “de-peasantization,” but also reinforces class stratification through the mechanism of “hired labor–surplus value extraction,” severely hindering the achievement of the United Nations’ 2030 poverty reduction goals [62]. Second, rising land transfer prices may become a barrier for young people to participate in the land market, hindering intergenerational renewal in agricultural production and trapping agricultural transformation in an “aging trap” [63,64]. These impacts are widespread in African regions, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. These findings provide an important warning for developing countries to balance land market reforms and maintain land transfer prices within a reasonable range. In response, this study proposes alleviating the upward pressure on land transfer prices caused by labor return from two dimensions: enhancing the stability of property rights and increasing local non-farm employment opportunities, thereby providing useful policy references for developing countries.

This study may have limitations in the following two aspects. First, this study, based on the unique institutional context of China’s collective land ownership system, systematically examines the impact of labor return on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms. These findings may not be directly generalizable to countries or regions that implement private land ownership or have markedly different socioeconomic conditions. The generalizability of the findings is primarily constrained by two factors:

- (1)

- Labor migration patterns. Influenced by factors such as the household registration (hukou) system or land institutions, labor migration in many developing countries often exhibits a pattern of “circular migration,” making labor return more prevalent. By contrast, in developed countries such as those in Europe and North America, rural-to-urban migration is typically a one-way process, with relatively few cases of labor return. Even when return migration occurs, the likelihood of returnees re-engaging in agricultural production is relatively low (although cross-border labor return can indirectly increase land values by boosting local demand for agricultural products). Therefore, the findings of this study are more applicable to the context of developing countries. In developed countries, the effect of labor return on land transfer prices may be weaker or may take a longer time to materialize. It is worth noting that existing research on how natural disaster shocks lead to population outflow in developed countries and consequently reduce land values share similar theoretical logic with this study and serves as a valuable complement [24,65].

- (2)

- Land institutions. In China, the collective ownership of land results in fragmented plots distributed among numerous smallholder farmers. Farmers only hold land use rights, while ownership remains with the collective. This institutional arrangement means that large-scale land management must be achieved through multi-party land transfers rather than outright land sales. Such a structure provides an institutional basis for returning laborers to continue farming. Coupled with Chinese farmers’ deep emotional attachment to land, when off-farm employment is disrupted, land often becomes an important livelihood safeguard. This also explains why China’s smallholder economy has not exited completely and why large-scale farming remains unstable in recent years. By contrast, in developed countries such as those in Europe and North America, a more relaxed land-to-population ratio allows large-scale farming to be realized primarily through market-based leasing or sales. Particularly in countries with private land ownership, the complete transfer of land property rights means that, even if labor return occurs, it is difficult to exert a strong short-term impact on land market supply and demand. Therefore, the findings of this study may be more applicable to countries with collective land ownership or tight land-to-population ratios, such as Vietnam and other developing countries [66], or developed countries currently experiencing counter-urbanization.

Second, although this study attempts to examine the long-term changes in the land market induced by labor return from a dynamic perspective, data limitations make it difficult to analyze the relationship over a longer time span. Fortunately, the data cover periods both before and after the outbreak of COVID-19, a major public health event that triggered large-scale labor return to places of household registration, which to some extent helps mitigate the issue of farmers’ self-selection.

Based on these limitations, future research could make breakthroughs in the following directions: First, in terms of data, this study primarily relies on Chinese data. Future work could integrate the LSMS (Living Standards Measurement Study) database led by the World Bank and the LFS (Labor Force Survey) database promoted by the International Labor Organization to conduct cross-institutional, cross-country, and long-term comparative studies on the relationship between labor mobility and land factor prices. Second, in terms of research content, this study has not yet explored in depth the welfare changes experienced by different types of farmers following the increase in land transfer prices caused by labor return. This topic merits focused attention and in-depth analysis in future research.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

7.1. Conclusions

Under the current labor mobility dynamics, the sheer outflow of labor is no longer sufficient to exert substantial downward pressure on land transfer prices. Instead, the positive impetus from localized labor return migration has emerged as the key driver of land rental price fluctuations. This study systematically examined the impact of migrant workers’ return on land transfer prices and its underlying mechanisms. First, the benchmark regression results and robustness tests indicate that migrant workers’ return to their household registration areas significantly increases local land transfer prices. Compared with villages without migrant workers’ return, villages with labor return have significantly higher land transfer prices, validating Hypothesis 1.

Second, the mechanism analysis results indicate that migrant workers’ return to the household registration area not only increases land transfer prices by lowering local labor factor prices and raising land factor prices but also by increasing local land demand and reducing land market supply. This validates Hypothesis 2.

Finally, the moderating effect analysis results indicate that stabilizing expectations regarding land contracting rights and increasing local non-agricultural employment opportunities can mitigate the upward pressure on land transfer prices caused by migrant workers’ return. This provides solutions to reduce the stagnation of rural surplus labor in agriculture, enhance the adequacy of labor force transfer to non-agricultural sectors, and stabilize land transfer prices.

7.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed to provide policy guidance for effectively regulating land transfer prices and mitigating the squeeze on profit margins caused by high prices:

Promote non-agricultural employment and labor transfer. The government should actively create more flexible non-agricultural employment opportunities to facilitate the full transfer of labor from the agricultural to the non-agricultural sectors. This not only provides returning rural laborers with more employment options but also alleviates supply pressure in the land transfer market, thereby regulating land transfer prices.

Strengthen employment guidance and training. For returning rural laborers, the government should provide employment guidance and vocational skills training. This will enhance the accumulation of human capital among rural laborers and strengthen their competitiveness in the non-agricultural labor market. Improved stability in non-agricultural employment will reduce demand fluctuations in the land transfer market caused by employment instability, thereby mitigating fluctuations in land transfer prices.

Stabilize expectations regarding land contracting rights. Strengthening the protection of land contracting rights facilitates the orderly conduct of land transfers and the protection of farmers’ rights. Stable expectations regarding land contracting rights can enhance farmers’ confidence in long-term land contracting rights, stimulate their enthusiasm for participating in land transfers, and reduce price fluctuations in the land transfer market caused by unstable land rights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and Y.J.; methodology, M.G.; software, M.G.; validation, M.G.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G. and R.P.; resources, M.G.; data curation, M.G. and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, R.P. and Y.J.; visualization, R.P.; supervision, R.P.; project administration, Y.J.; funding acquisition, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Program of National Fund of Philosophy and Social Science of China (21&ZD101).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| IV-2SLS | Instrumental Variables-Two-Stage Least Squares |

| DWH | Durbin-Wu-Hausman |

References

- Xu, M.; Chen, C.; Xie, J. Off-farm employment, farmland transfer and agricultural investment behavior: A study of joint decision-making among North China Plain farmers. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 95, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Ji, Y. The Impact of Off-Farm Employment Recession and Land on Farmers’ Mental Health: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Land 2024, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]