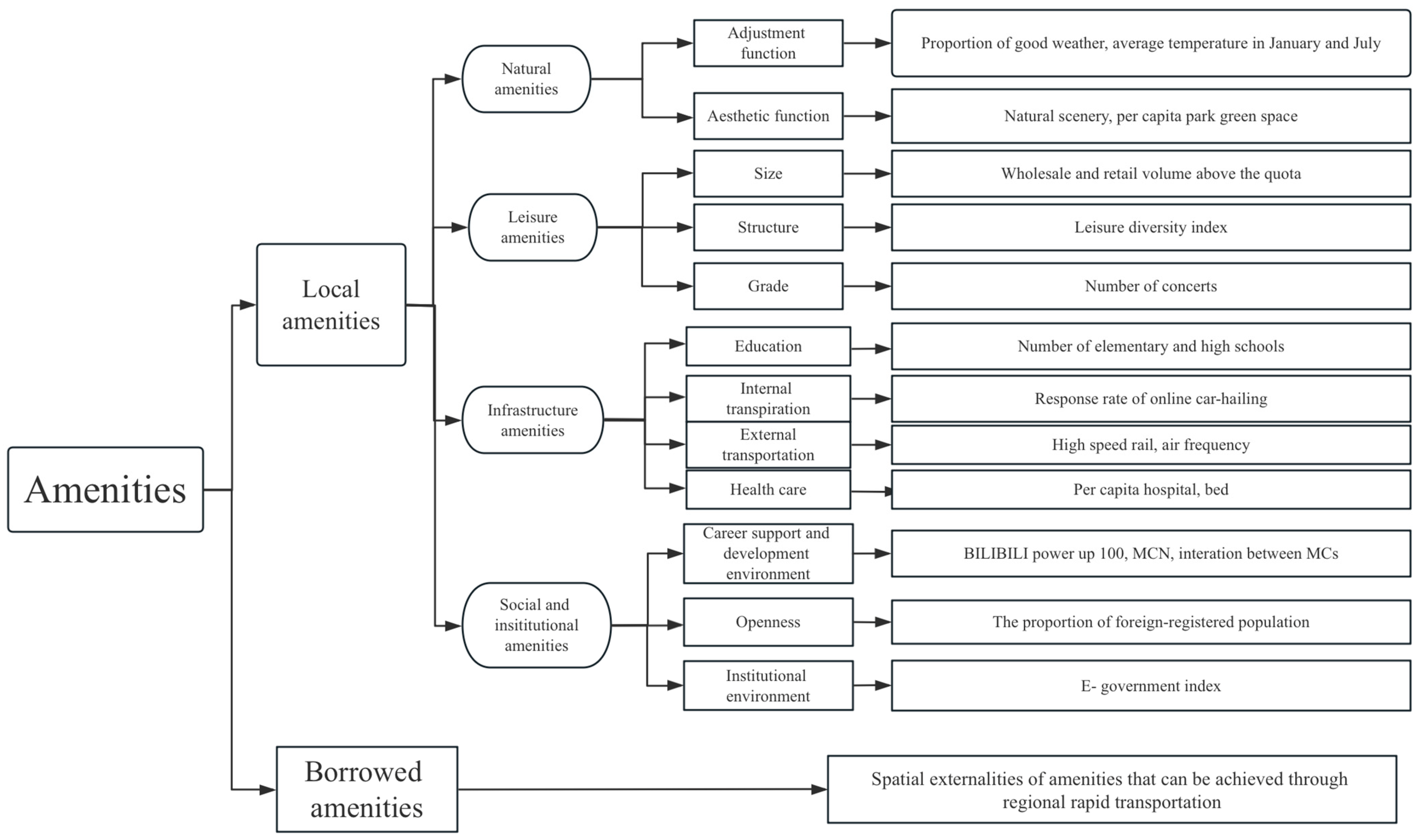

4.2.2. Influencing Mechanism

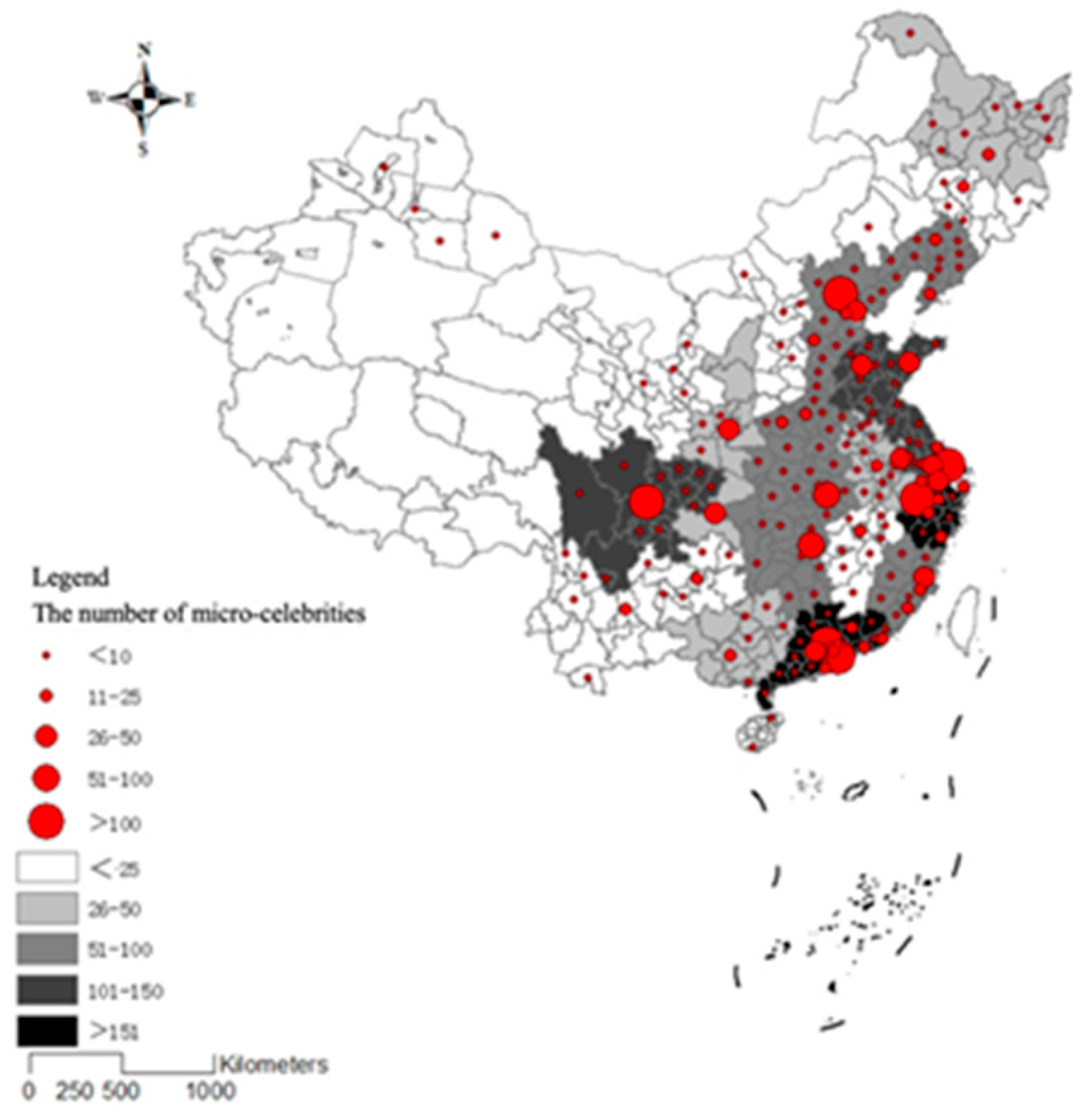

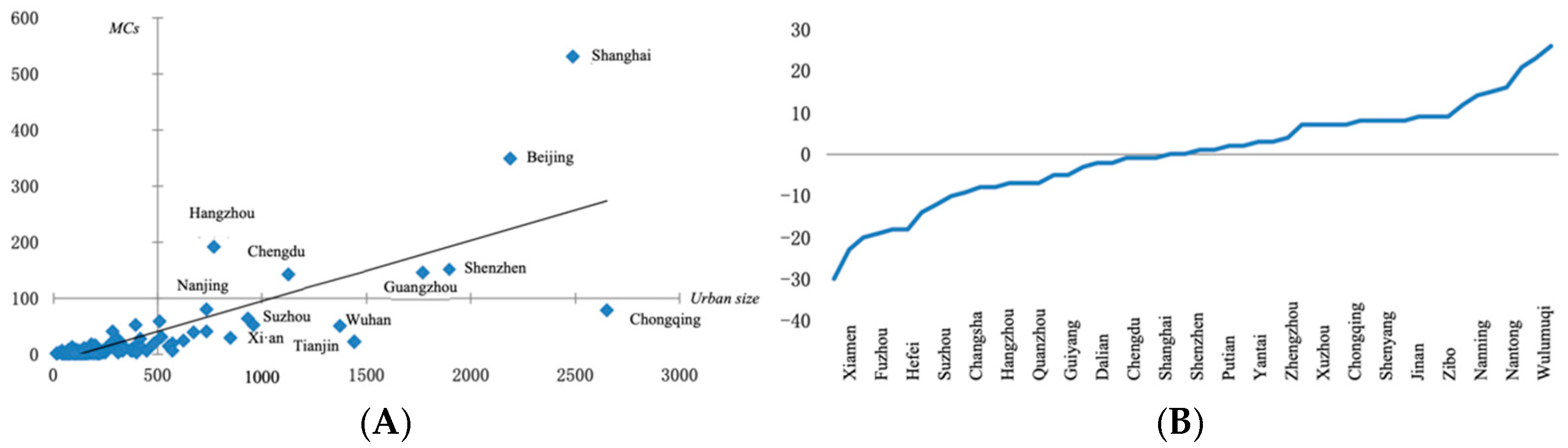

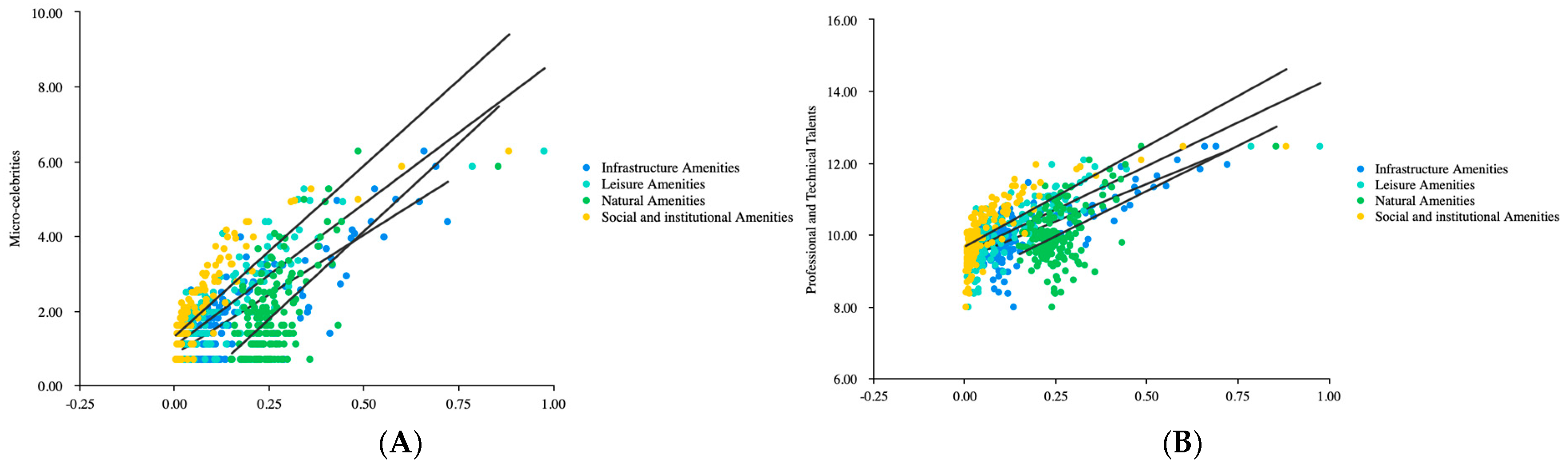

The regression results are listed in

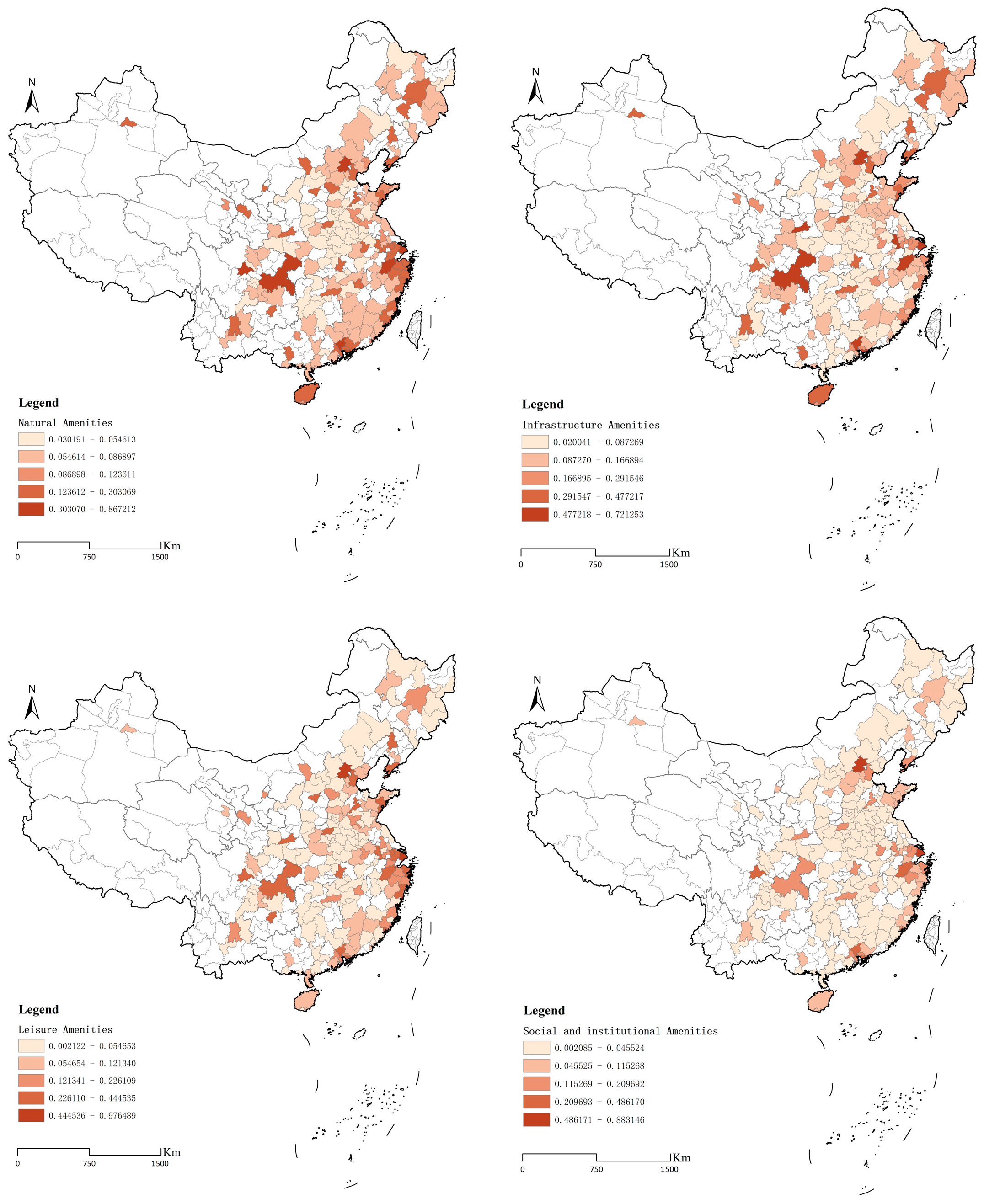

Table 3. Natural amenities display a weak influence on micro-celebrities. Although the scatter plot and separate regression model show a significant correlation, the effect of natural amenities is notably weakened when other socio-economic and cultural factors are considered. This finding indicates that the classic natural factors highlighted in migration literature—such as warm winters, cool summers, and air quality—are insufficient to be the primary factors influencing micro-celebrities’ location choices.

However, this does not imply that natural amenities are irrelevant. The narrowing gap in air quality across Chinese cities due to green development strategies and the fact that the natural environment tends to be more appealing to the elderly, while most micro-celebrities are younger, may also contribute to these findings. When controlling for employment factors, the influence of natural amenities becomes significant, highlighting their importance to some extent (

Table 4).

Infrastructure, leisure, and social and institutional amenities consistently exert a significant positive impact on the distribution of micro-celebrities when controlling for economic factors and employment opportunities. Previous literature has recognized infrastructure and leisure opportunities as the basis of urban life quality and objective happiness. Scholars have argued that cities are more defined as places providing employment opportunities for professional and technical talents [

62], while creative talents view cities as places to enjoy life [

63]. This can be confirmed by comparing the results of Models 1 and 2 (

Table 5). The impact of amenities is lower for professional and technical talents, supporting Florida’s assertion that “the creative class is more inclined to high-amenities cities than professional and technical talents”. Specifically, convenient infrastructure meets residents’ daily needs [

64], while the scale, diversity, and selectivity of leisure opportunities satisfy creative talents’ pursuit of personal quality of life and various post-work consumption activities.

As can be seen from model 1 (

Table 3), the influence of social and institutional amenities on digital creative talents is significantly higher than other amenities and increases with the enhancement of talent mobility and autonomy (model 1 and 2). This shows that the local social institutional environment has become the core condition for cities to attract creative talents in the digital era, because the spatial binding and social contract relationship between digital creative talents and enterprises is weak, while obtaining mobility and freedom, identity, social support, security, and income stability has gradually become important challenges for them. The social and institutional amenities are the key to solving such challenges. Once social and institutional amenities are established, the resulting regional brand effect and circular cumulative effect strengthen the attraction of digital creative talents. This phenomenon explains why Hangzhou has formed a micro-celebrity cluster while Suzhou and Nanjing have not (

Table 5). However, social and cultural amenities are not the primary factors shaping the distribution of creative talents unless other amenity dimensions are sufficiently high. For example, most cities in Hebei Province have failed to attract micro-celebrities, despite many incentive policies introduced for digital media and entrepreneurship subsidies, due to the low levels of other amenities. This suggests that different dimensions of amenities have more complex sequences and interactions than simple correlations in their functioning.

These results remain robust even after considering urban employment levels. The debate on the importance of economic opportunities versus amenities in talent location decision-making has persisted since Florida introduced the creative class theory [

65]. Previously, it was acknowledged that amenities had an insignificant impact on the location of skilled talents [

66]. However, recent evidence suggests a growing significance of amenities, although economic factors continue to have a significantly greater impact on creative talents [

67]. Our findings indicate that employment opportunities do not significantly diminish the pursuit of amenities by digital creative talents, marking a distinct difference from professional and technical talents. Nonetheless, our results show that amenities exert a more pronounced influence on technical professionals than employment.

The analyses reveal that the adjustment function indicators of natural amenities have a weak and unrobust influence on the micro-celebrity distribution after controlling for other amenities and economic factors (

Table 6). In contrast, aesthetic functions indicators consistently show significant positive effects, indicating that creative talents prefer natural public spaces offering leisure, relaxation, and entertainment functions. These spaces, which are the objective basis of happiness [

68], have been lost to varying degrees during the rapid urban expansion that China has experienced in the past few decades.

The influence of leisure amenities is primarily realized through structural and scale indicators rather than hierarchical indicators (

Table 7). Experiences from developed countries show that the high levels of spiritual consumption opportunities are more attractive to creative talents than the convenience of daily consumption. Our findings, however, suggest that the effect of higher levels of cultural consumption is not essential in developing countries after controlling for daily consumption opportunities. This does not mean that high-level spiritual consumption activities are dispensable, as these activities can be accessed inter-urban due to their low frequency of consumption in most cases. Florida’s emphasis on “a theater is more important than a shopping mall” does not consider the complementary and borrowing amenities of neighboring cities.

The regression results for infrastructure amenities indicate that the inter-urban communication ability plays a positive role, remaining robust after controlling for other dimensions of amenities (

Table 8). However, the influence of intra-urban transportation accessibility decreases significantly. Micro-celebrities exhibit higher mobility than other occupational types due to the freelance nature of their work. This finding provides evidence that the ability to communicate outside the city is more attractive to creative talents than intra-city accessibility. Meanwhile, flexible ride-hailing is more favored by digital creative talents than public transportation. In terms of medical facilities, basic medical facilities seem to be insufficient to affect the distribution of digital creative talents, but high-level hospitals have a significant impact.

The coefficients of social and institutional amenities indicators were all significantly positive (

Table 9), the coefficient for MCNs decreases after considering other amenities levels, and the influence of interaction between micro-celebrities increases. On the one hand, communication based on shared identity strengthens group identity. On the other hand, micro-celebrities build and strengthen personal social networks, accumulate social capital, and improve their resistance to career instability through co-creation with other micro-celebrities [

69]. This also explains the impact of MCNs, which provide temporary services such as advertising, media design, and technical support, even though most micro-celebrities do not directly join MCNs. Such partnerships, based on temporary projects, can also create informal social networks to withstand instability. Interestingly, the initial distribution pattern of micro-celebrities appears non-significant for subsequent distribution when other amenities are controlled. The initial micro-celebrities introduced this new occupation to the public, leading to its gradual acceptance by the mainstream, which caused local imitation and, consequently, more micro-celebrities. This demonstration effect is spatially dependent, making the current situation significantly related to the initial pattern of micro-celebrity distribution. However, the influence of this demonstration effect is more critical in the early stages, and as the number of we-media creators has soared in recent years, the occupation of micro-celebrity has become widely accepted, weakening the demonstration effect when other amenities indicators are controlled. This means that many cities that do not have the advantage of initial agglomeration of digital creative talents can catch up through amenities. For example, the number of the first Top 100 MCs in Hangzhou, Chengdu, and Nanjing is much lower than that in Beijing and Shenzhen, but to date, the number of MCs in these cities has been close to Shenzhen. According to the above analysis, this kind of catch-up depends more on social and institutional factors.

The results indicate that leisure, infrastructure, and social and cultural amenities can be borrowed between cities. Notably, the effects of leisure and institutional amenities remain significant even after controlling for local amenities levels. This finding confirms the importance of considering spatial borrowing in the analysis of amenities. Without accounting for this, the impact of local amenities may be overestimated, especially concerning creative talents. It further suggests that the location decisions of micro-celebrities are influenced not only by a combination of economic and social factors within a city but also by the amenities available in surrounding cities.

When the level of local infrastructure amenities is controlled, the borrowing effect of infrastructure amenities becomes insignificant, highlighting the greater importance of local infrastructure conditions. Although the investment in transportation, medical care, education, and other infrastructure in cities at the prefecture level and above is somewhat correlated with the local economic level, national policies aimed at ensuring fairness in infrastructure distribution generally maintain a consistent level of infrastructure across these cities [

70]. The Moran’s I result also supports the finding that infrastructure amenities exhibit lower agglomeration and narrower inter-city gaps compared to other amenities, making it less likely for people to change their location based on such narrow differences in infrastructure. In reality, it is common for smaller cities to borrow high-level medical and transportation infrastructure from central cities, but this borrowing is more prevalent between county towns and prefecture-level cities rather than between cities of the same administrative level.

The borrowing of leisure amenities remains significant even after controlling for local amenities levels, indicating the equal importance of both local leisure opportunities and inter-urban leisure accessibility. These results provide empirical support for the “spatial quality” models in new spatial economics. However, the influence of leisure amenities in surrounding areas diminishes when local leisure opportunities are taken into account. This finding confirms that amenities related to daily life are the main factors affecting the distribution of micro-celebrities, while the influence of high-level consumption is statistically insignificant. A possible reason is that low-frequency consumption can be accessed inter-urban.

Social and institutional amenities borrowed from surrounding cities continue to impact the distribution of micro-celebrities, even when other variables and local amenities are controlled (

Table 10). Institutions, especially informal ones in traditional industries, tend to be highly localized, and the conditions for spatial spillover of economic effects from institutions are much more complex than those for infrastructure and leisure opportunities. However, the agglomeration of micro-celebrities in surrounding cities can be promoted by the institutions and social amenities of a central city, meaning that demonstration and imitation also occur between cities, particularly when transportation between them is convenient. Overall, the professionalization of micro-celebrities may be achieved through a combination of complementary institutions, informal micro-celebrity social networks, brand cooperation in the central city, and local cost advantages in peripheral areas. This complementary combination generally occurs in urban agglomerations with well-developed intercity transportation networks, but it does not universally apply unless the peripheral areas have sufficiently high amenities. For example, Hebei Province, despite its proximity to Beijing and the availability of convenient transportation networks and low living costs, has failed to form a micro-celebrity cluster.