Typo-Morphology as a Conceptual Tool for Rural Settlements: Decoding Harran’s Vernacular Heritage with Reflections from Alberobello

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Foundations

1.2. Conic Domed Dwellings

1.3. Problem Statement, Aims, and Research Questions

- Uncover the spatial and typological logic underlying Harran’s domed housing system.

- Trace its transformation across time through a multiscale analysis, from individual building units (compound scale) to the broader urban fabric (both ditrict and town scales).

- Offer reflections from the case of Alberobello to understand the influence of planning policy, heritage governance, and cultural continuity.

- How do the spatial organization and typological logic of Harran’s domed dwellings reflect patterns of adaptation, growth, and cultural continuity?

- In what ways can typo-morphological analysis reveal the evolutionary paths of such settlements across different scales?

- What lessons can be drawn from the comparison with Alberobello regarding the integration of heritage morphology into planning and conservation strategies?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Selection

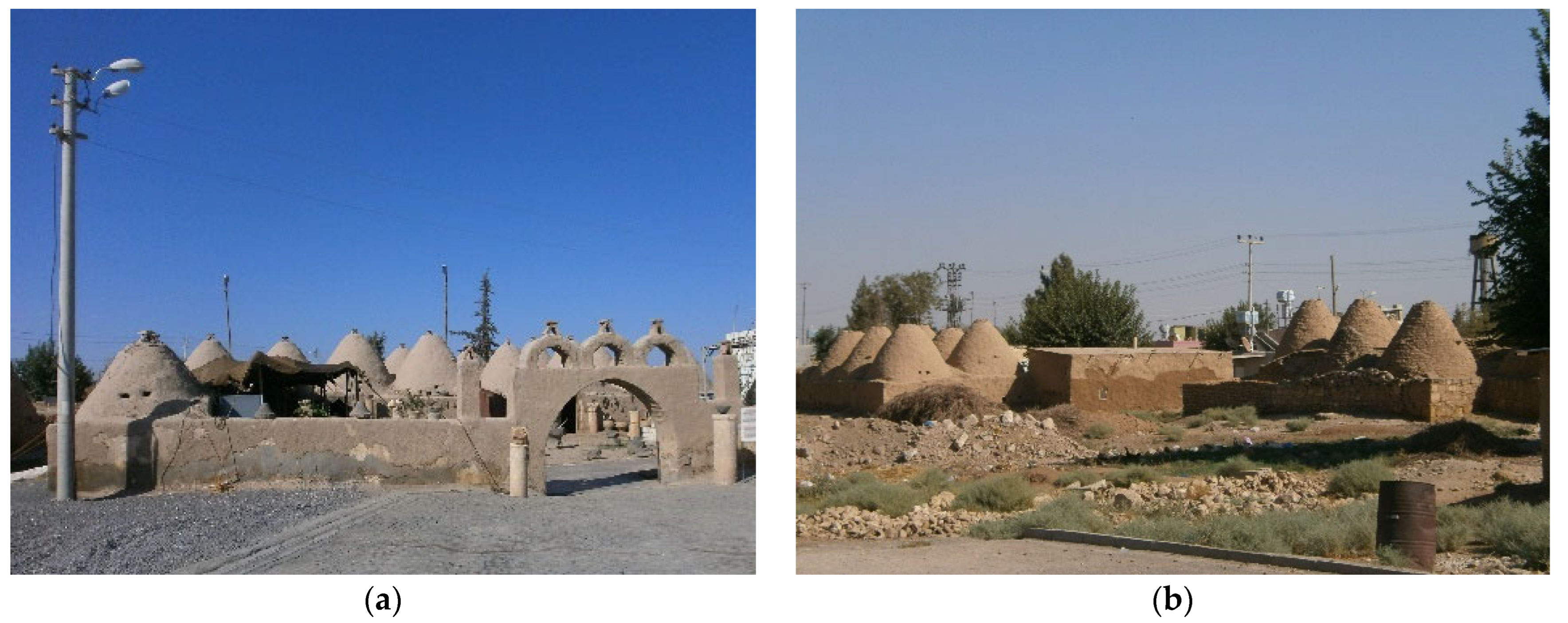

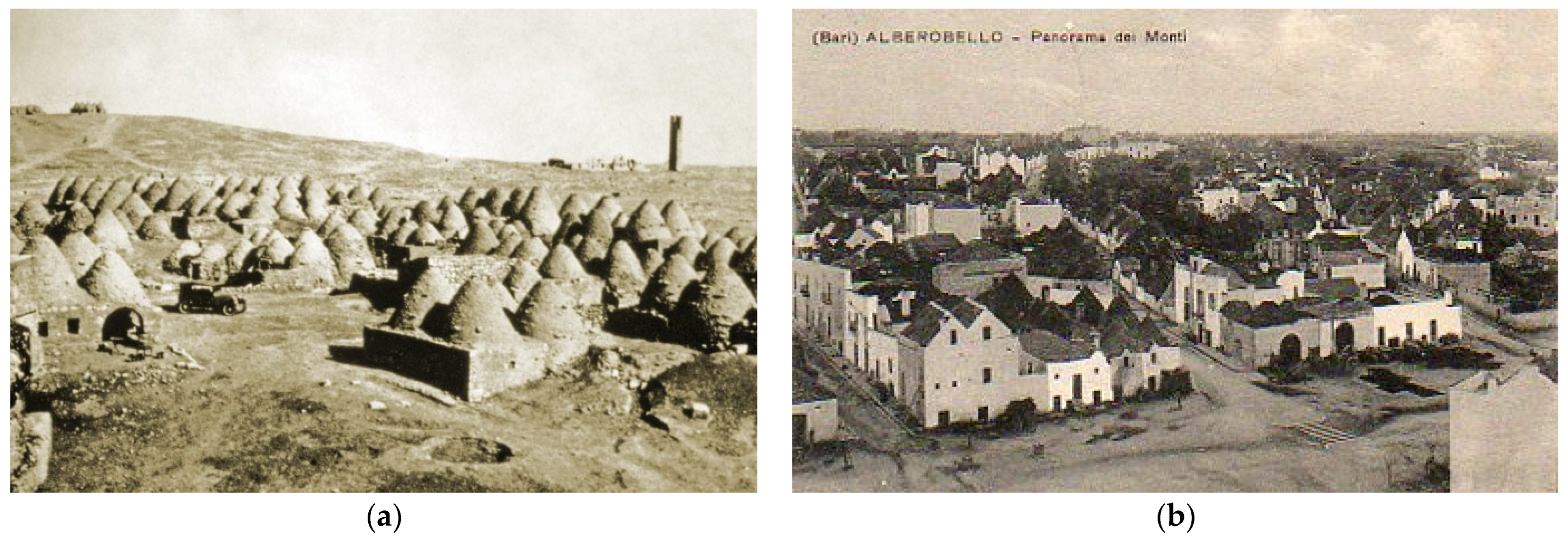

2.1.1. Harran (Şanlıurfa, Türkiye)

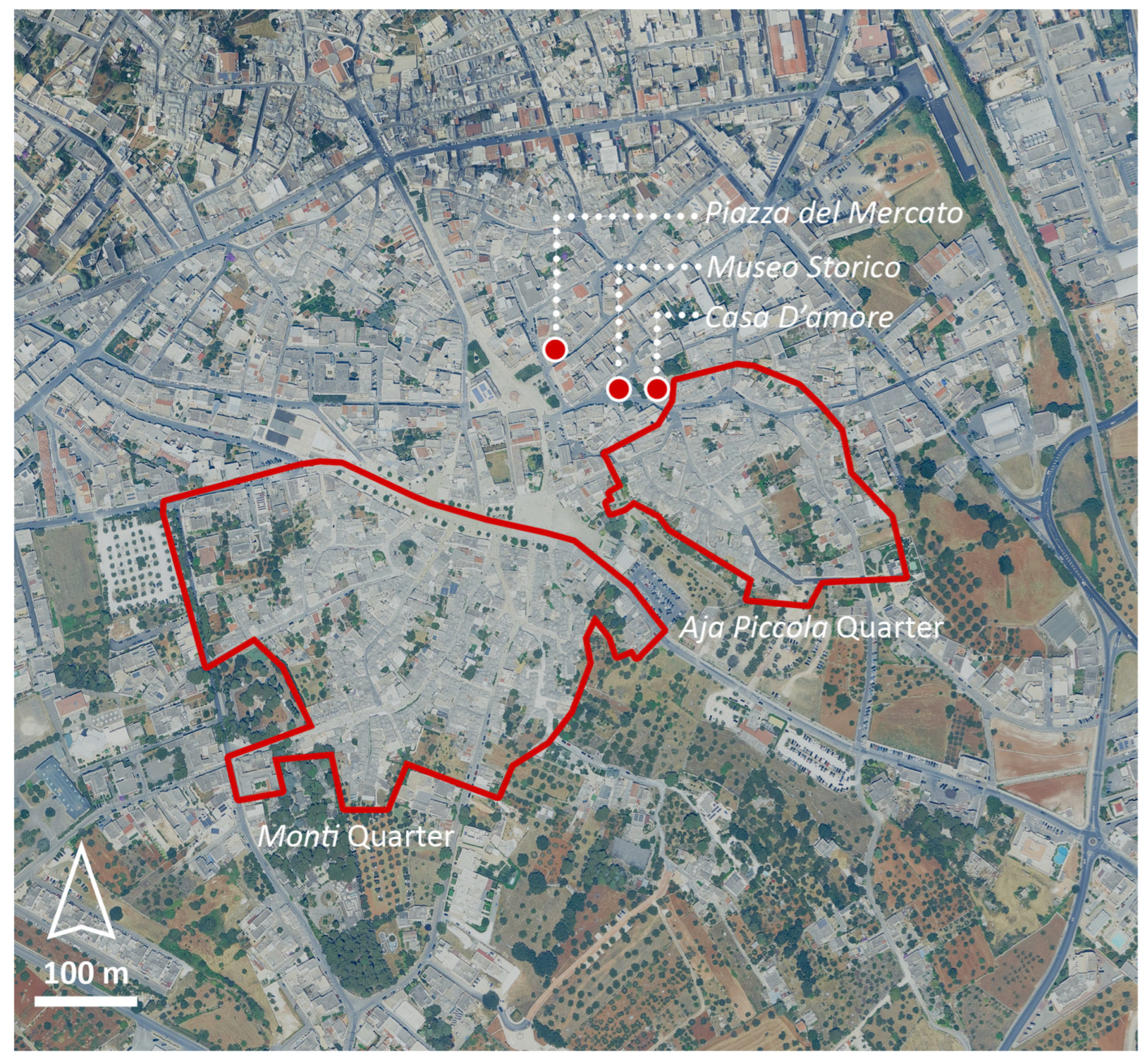

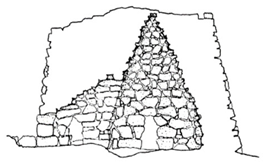

2.1.2. Alberobello (Puglia, Italy)

2.2. Data Collection

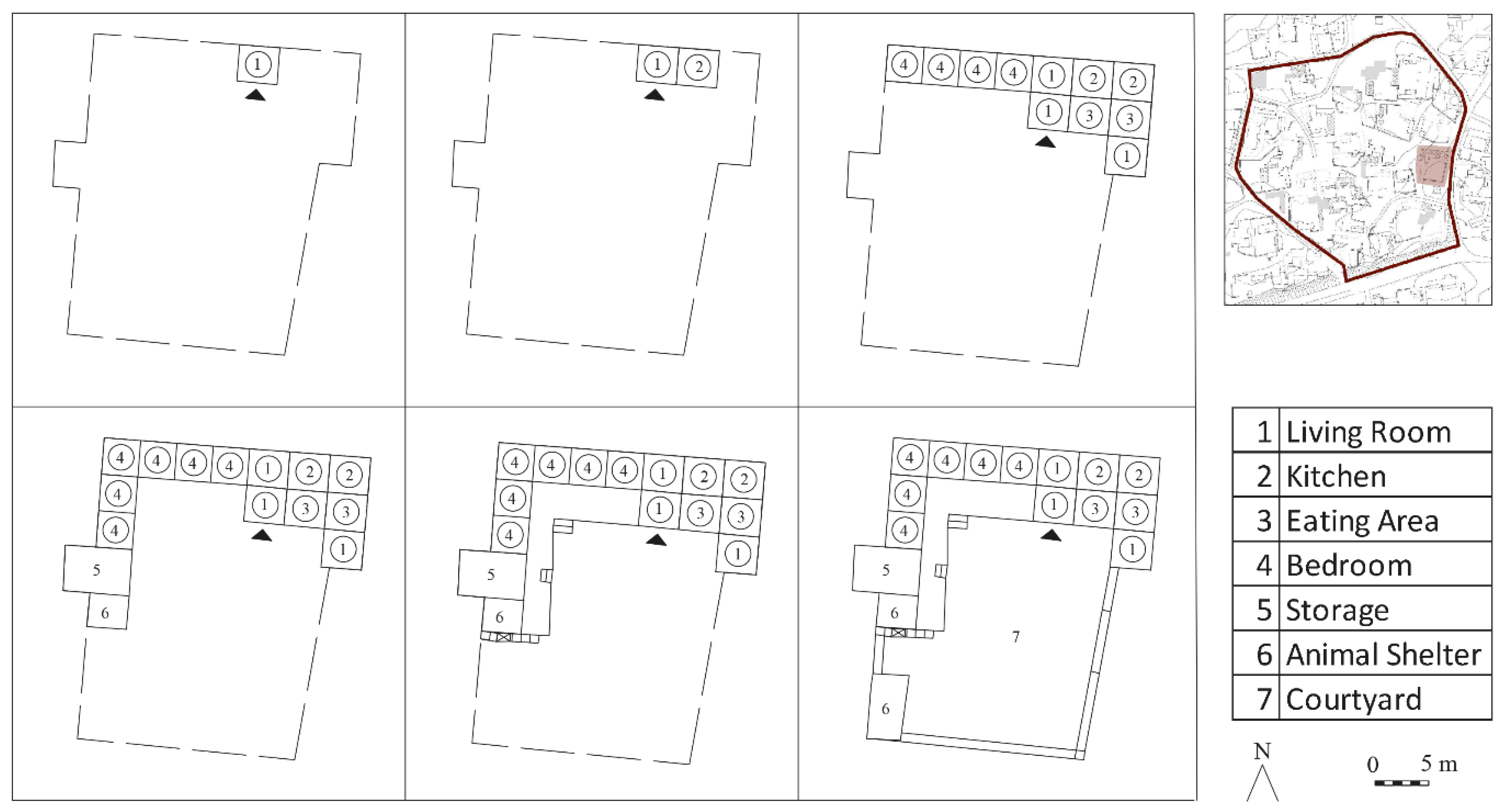

2.3. Typo-Morphological Framework (Compound Scale)

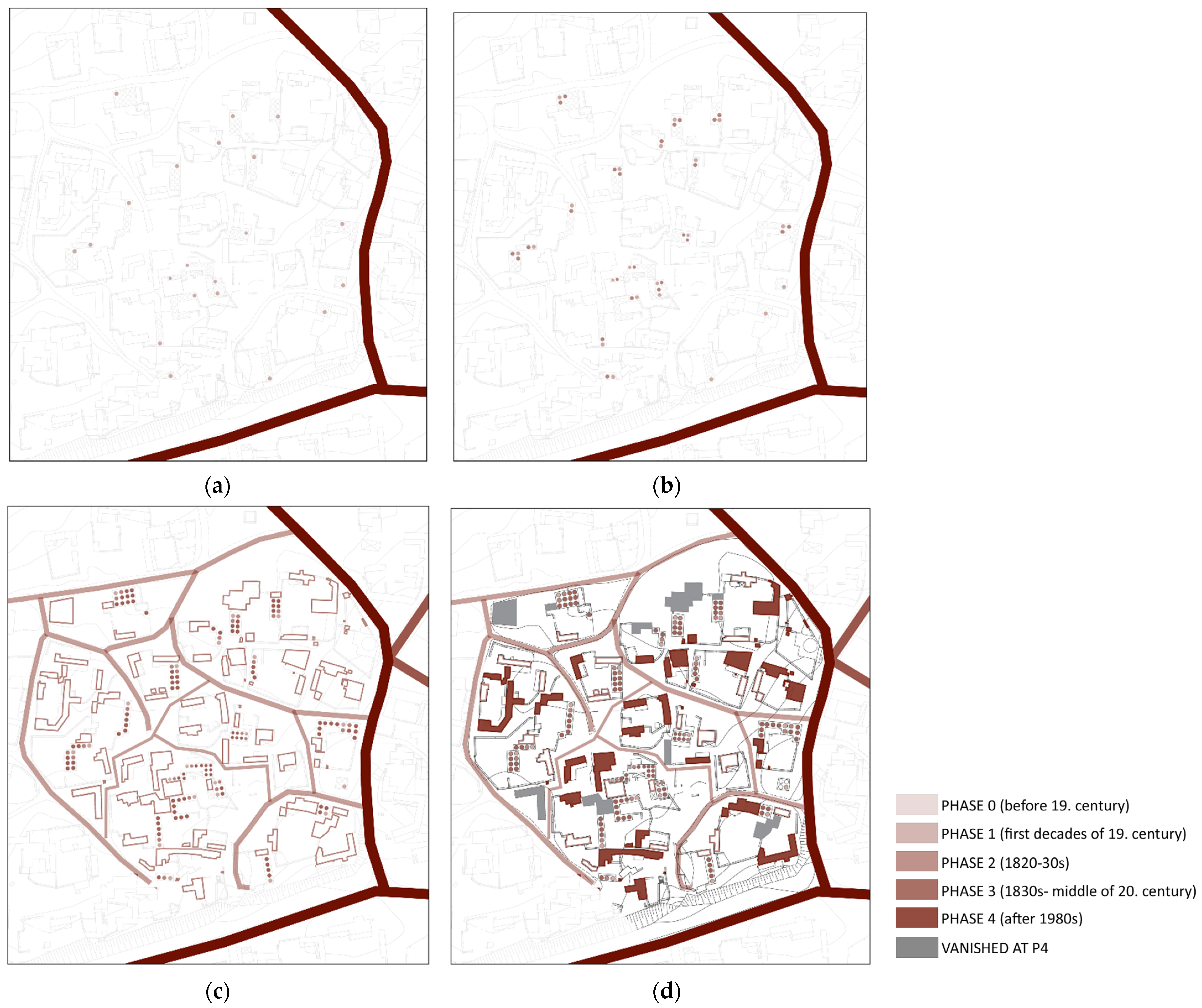

2.4. Expansion Analysis (District and Town Scales)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Methodological Discussion

3.2. Typo-Morphological Framework (Compound Scale)

3.3. Expansion Analysis of the Settlement (District and Town Scales)

3.3.1. District Scale

3.3.2. Town Scale

3.4. Reflections from Alberobello

3.4.1. Morphological Similarities and Divergences

3.4.2. Legal and Institutional Reflections

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Anno Domini |

| BC | Before Christ |

| E | East |

| Ha | Hectare |

| GAP | Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi—Southeastern Anatolian project |

| ICOMOS | International Council on Monuments and Sites |

| Mw | Moment Magnitude (used for measuring earthquake magnitude) |

| N | North |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| VGI | Volunteered Geographic Information |

| km | Kilometer |

References

- Cataldi, G.; Maffei, G.L.; Vaccaro, P. Saverio Muratori and the Italian School of Planning Typology. Urban Morphol. 2002, 6.1, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maretto, M. View of the Early Contribution of Saverio Muratori: Between Modernism and Classicism. Available online: https://journal.urbanform.org/index.php/jum/article/view/3970/3343 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Samoná, G. Tradizionalismo Ed Internazionalismo in Architettura. Rass. Di Archit. 1929, 2, 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Strappa, G. Reading the Built Environment as a Design Method. In Urban Book Series; Teaching Urban Morphology; Oliveira, V., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovski, T.; Axelsson, Ö. Typo-Morphology and Environmental Perception of Urban Space. In Proceedings of the ISUF 2018 XXV International Conference: Urban Form and Social Context: From Traditions to Newest Demands, Krasnoyarsk, Russia, 5–9 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gugliotta, R. Reading Morphology Through Diagrams. Exploring Methodology. In Proceedings of the 6th ISUFitaly International Conference: Morphology and Urban Design—New Strategies for a Changing Society, Bologna, Italy, 8–10 June 2022; pp. 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Strappa, G. Urban Morphology Following the Muratorian Tradition. “DeğişKent” Değişen Kent, Mekân ve Biçim Türkiye Kentsel Morfoloji Araştırma Ağı. In Proceedings of the II. Kentsel Morfoloji Sempozyumu, Istanbul, Turkiye, 31 October–2 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.I.; Koren, A.S.A.; Hassan, G.F.; El Fayoumi, M.A.; Afifi, S.Z. Urban Morphology Schools of Thoughts; A Holistic Overview. YMER 2024, 22, 747–768. [Google Scholar]

- Bechlem, R.; Djouad, F.-Z.; Salah-Salah, H. Morphological Analysis of Public Spaces and Their Contribution to Urban Resilience in Guelma, Algeria. J. Mediterr. Cities 2024, 4, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, A.; Monti, P.; Coch Roura, H.; Cecere, C. Climatic Performance of Urban Textures: Analysis Tools for a Mediterranean Urban Context. Energy Build 2019, 185, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarco, C. The Substrate and Urban Transformation. Rome: The Formative Process of the Pompeo Theater Area. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2019, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunca, Ö.; Rutten, K. The Corbelled Dome in the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. In Earthen Domes et Habitats. Villages of Northern Syria an Architectural Tradition Shared by East and West; Mecca, S., Dipasquale, L., Eds.; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sami, K.; Özdemir, İ. The Vernacular Houses of Harran and Cultural Heritage-Turkey. Int J Acad Res 2011, 3, pp.148–151. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdar, S.İ. Urfa-Harran Houses and Living Spatial Places. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. Technol. 2017, 17, 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Günkut, A. Geleneksel Harran Evleri. In Yurt Ansiklopedisi, Cilt.10; Anadolu Yayıncılık: Istanbul, Turkiye, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest; Thames & Hudson: London, UK, 1978; p. 252. [Google Scholar]

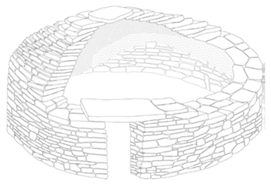

- Rovero, L.; Tonietti, U. A Modified Corbelling Theory for Domes with Horizontal Layers. Constr Build Mater 2014, 50, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygielman, M. Tholos Tombs in Etruria. In Earthen Domes et Habitats. Villages of Northern Syria an Architectural Tradition Shared by East and West; Mecca, S., Dipasquale, L., Eds.; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vegas, F.; Mileto, C.; Cristini, V. Corbelled Dome Architecture in Spain and Portugal, Earthen Domes And Habitats. In Earthen Domes et Habitats. Villages of Northern Syria an Architectural Tradition Shared by East and West; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ghobadian, V. Climatic Analysis of the Iranian Traditional Buildings; Tehran University Publications: Tehran, Iran, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Niroumand, H.; Jamil, M.; Zain, M.F.M. The Earth Refrigerators as Earth Architecture. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2012, 3, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakadaki, M. Corbelled Dome Architecture in Greece. In Earthen Domes et Habitats. Villages of Northern Syria an Architectural Tradition Shared by East and West; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dipasquale, L.; Devaux, E. The Urban Morphology of Dome Villages. In Earthen Domes et Habitats. Villages of Northern Syria an Architectural Tradition Shared by East and West; Edizioni ETS: Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.-C.; Swenson, A. Construction|History, Types, Examples, & Facts. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/construction (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Ölçer, S.; Önal, M.; Yuksel, F.S.K.; Pişkin, N.; Çiftçi, S. Effects of 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Centered Earthquakes on Şanliurfa Immovable Cultural Heritage and Earthquake Debris Excavation Works. TÜBA-KED Türkiye Bilim. Akad. Kültür Envant. Derg. 2024, 30, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, S. Harran ve Alberobello Kardeş Şehir Oldu. ŞURKAV Kültür Sanat Ve Tur. Derg. 2014, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Başaran, T. Thermal Analysis of the Domed Vernacular Houses of Harran, Turkey. Indoor Built Environ. 2011, 20, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahya, O. Urfa- Harran Bölgesinde Geleneksel Halk Mimarisinde Tuğla-Taş –Kerpiç Evler Üzerine Bir İnceleme. In Proceedings of the II. Milletlerarası Türk Folklor Kongresi Bildirileri, Bursa, Turkiye, 22–28 June 1981; Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Ankara, Turkiye, 1983; pp. 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W.; Vogel, G. Atlas Zur Baukunst Band 1 Allgemeiner Teil Baugeschichte Von Mesopotamien Bis Byzanz. LANGENSCHEIDT: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Özdeniz, M.B.; Bekleyen, A.; Gönül, I.A.; Gönül, H.; Sarigül, H.; Ilter, T.; Dalkiliç, N.; Yildirim, M. Vernacular Domed Houses of Harran, Turkey. Habitat Int. 1998, 22, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardımcı, N. Mezopotamya’ya Açılan Kapı Harran; Eski Anadolu Kentler Dizisi, Ege Yayınları.: Istanbul, Turkiye, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu, S.İ. Early Bronze Age Architecture and Pottery Data from Harran Höyük in the Light of New Excavations. In Harran ve Çevresi Arkeoloji; Şurkav Yayınları: Şanlıurfa, Turkiye, 2019; pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kürkçüoğlu, A.C.; Karahan kara, Z. Harran—Medeniyetler Kavşaği.; Harran Kaymakamliği Kültür Yayinlari: Şanliurfa, Turkiye, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Harran Prefecture Harran Kaymakamlığı—Dünyanın İlk Üniversitesi. Available online: http://www.harran.gov.tr/ilk-universite (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Lloyd, S.; Brice, W.; Gadd, C.J. Harran. Anatol. Stud. 1951, 1, 77–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, D.S. Medieval Ḥarrān: Studies on its Topography and Monuments, I. Anatol. Stud. 1952, 2, 36–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golitsis, P. On Simplicius’ Life and Works: A Response to Hadot. Aestimatio Sources Stud. Hist. Sci. 2018, 12, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, G.; Parlavecchia, M.; Dal Sasso, P. Typological Characterisation and Territorial Distribution of Traditional Rural Buildings in the Apulian Territory (Italy). J. Cult. Herit 2019, 39, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieva, M.; Di Gioia, M.; Leone, F.M.; Regina, R.; Schiavone, F.A. The Concept of Morpho-Typology in the Alberobello Urban Organism. In Proceedings of the 5th ISUFitaly International Conference Rome, Rome, Italy, 19–22 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bertella, G.; Droli, M. Creative Practices of Local Entrepreneurs Reinventing Built Heritage. In Creating Heritage for Tourism; Palmer, C., Tivers, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Trulli of Alberobello—UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/787/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- UNESCO. The Trulli of Alberobello—Maps—UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/787/maps/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Muratori, S. Studi per Una Operante Storia Urbana Di Venezia; Istituto Poligrafico Dello Stato: Roma, Italy, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia, G. Lettura Di Una Città: COMO; Centro Studi di Storia Urbanistica: Rome, Italy, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Ogut, O.; Mutlu, N.D.; Oguz, B.; Ozdemir, O.C. The Reflection of Local Materials and Culture on Architecture: A Case Study of Harran. Adv. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2021, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saylan, S.; Gürer, T.K. Typomorphology: A Methodological Approach to Context Analysis in Architectural Design Education. Iconarp Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2024, 12, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wu, Y.; Fang, K.; Liu, X. Typo-Morphological Approaches for Maintaining the Sustainability of Local Traditional Culture: A Case Study of the Damazhan and Xiaomazhan Historical Area in Guangzhou. Buildings 2023, 13(9), 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, M.L.; Svenningsen, S. Reconstructing Historical Rural Addresses with VGI and Digitized Aerial Photography . Digit. Humanit. Nord. Balt. Ctries. Publ. 2019, 2, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, M.; Yılmaz, A. View of A Study of Local Environment of Harran Historical Domed Houses in Terms of Environmental Sustainabilit. J. Asian Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, D. From Pastoral Peasantry to Tribal Urbanites: Arab Tribes and the Foundation of the Islamic State in Syria. In Nomads, Tribes, and the State in the Ancient Near East: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives; Szuchman, J., Ed.; The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van der Steen, E. Tribal Societies in the Nineteenth Century: A Mode; Szuchman, J., Ed.; The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Birinci, S.; Kıvanç Kaymaz, Ç.; Camci, A. Harran County Seat and Traditional Dome in Terms of Culture Tourism (Şanliurfa). Turk. Studies. Int. Period. Lang. Lit. Hist. Turk. Or Turk. 2017, 12/3, 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ünver, I.H.O. Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP). Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 1997, 13, 453–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikme, Y. Harran’ın Konik Kubbeli Evlerine Bakım. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/kultur-sanat/harranin-konik-kubbeli-evlerine-bakim/1387796 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Sanliurfa Governorship Şanlıurfa Valiliği—Harran. Available online: http://www.sanliurfa.gov.tr/harran3 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Sel, B.D.; Çelebioğlu, B.; Özdemir, O.Ç. Examining the Sustainable Urban Environments. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Turkish Travel Agencies Harran Houses. TURSAB 2013, 335, 40–45.

- Anadolu Doğa ve Kültür Koruma Kooperatifi (AnaDOKU). General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museums Harran Management Plan (2016–2021); Şanlıurfa: Şanlıurfa, Turkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Todisco, L.; Sanitate, G.; Lacorte, G. Geometry and Proportions of the Traditional Trulli of Alberobello. Nexus Netw. J. 2017, 19, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieva, M.; Indrio, G.; Lasorella, D.; Gorgoglione, G.; Di Bari, P. Urban Morphology in Historical Context the Concept of “Trullo Type” in the Formation of Alberobello Urban Organism. In Proceedings of the 5th ISUFitaly International Conference Rome, Rome, Italy, 19–22 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, A. Voyages Archéologiques Dans la Turquie orientale: I, Texte/Albert Gabriel; Avec un Recueil D’inscriptions Arabes par Jean Sauvaget; E. de Boccard: Paris, France, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Heritage Centre Harran and Sanliurfa. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/1400/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage. 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org.tr/Dosyalar/ICOMOSTR_en0464200001536913566.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

| Place | Date | Drawing | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

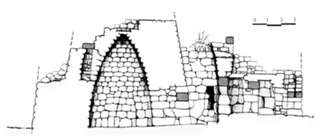

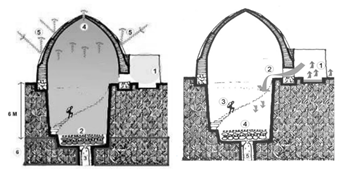

| Mesopotamia | 5900–5300 BC |  | Tholos is a building type with a rectangular planned entrance and a round planned main room. Both round structures and rectangular structures have stone foundations, masonry walls, and plaster [12,16]. |

| Italy | Around 1500 BC |  | Nuragic culture is noted for monumental architecture and prolific metallurgical activities [17]. |

| Italy | Around 1000 BC |  | The Etruscan tomb structure showed a significant improvement in the Mediterranean tomb architecture [18]. |

| Spain and Portugal | Around 1000 BC |  | This type of domed structure is used by societies engaged in transhumance activities. According to the seasons, shepherds come to these regions to graze their animals in the summer [19]. |

| Iran (ice houses) | Around 440 BC |  | The emergence and development of these structures have occurred through historical processes, the need to keep materials and water cold in the desert heat, and experience and knowledge gained by people [20,21]. |

| Greece | 6th century |  | These are built in rectangular and terraced forms in a small, modest manner on mountain slopes, low-altitude areas, transition routes, and winter pasture areas [22]. |

| Syria | 14th century |  | The morphology of the house in towns and villages developed from the material expression of uses, customs, beliefs, and the culture of a particular people [23]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ogut, O. Typo-Morphology as a Conceptual Tool for Rural Settlements: Decoding Harran’s Vernacular Heritage with Reflections from Alberobello. Land 2025, 14, 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071463

Ogut O. Typo-Morphology as a Conceptual Tool for Rural Settlements: Decoding Harran’s Vernacular Heritage with Reflections from Alberobello. Land. 2025; 14(7):1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071463

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgut, Ozge. 2025. "Typo-Morphology as a Conceptual Tool for Rural Settlements: Decoding Harran’s Vernacular Heritage with Reflections from Alberobello" Land 14, no. 7: 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071463

APA StyleOgut, O. (2025). Typo-Morphology as a Conceptual Tool for Rural Settlements: Decoding Harran’s Vernacular Heritage with Reflections from Alberobello. Land, 14(7), 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071463