Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Conservation: The Role of Gender and Education in Northeastern Algeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

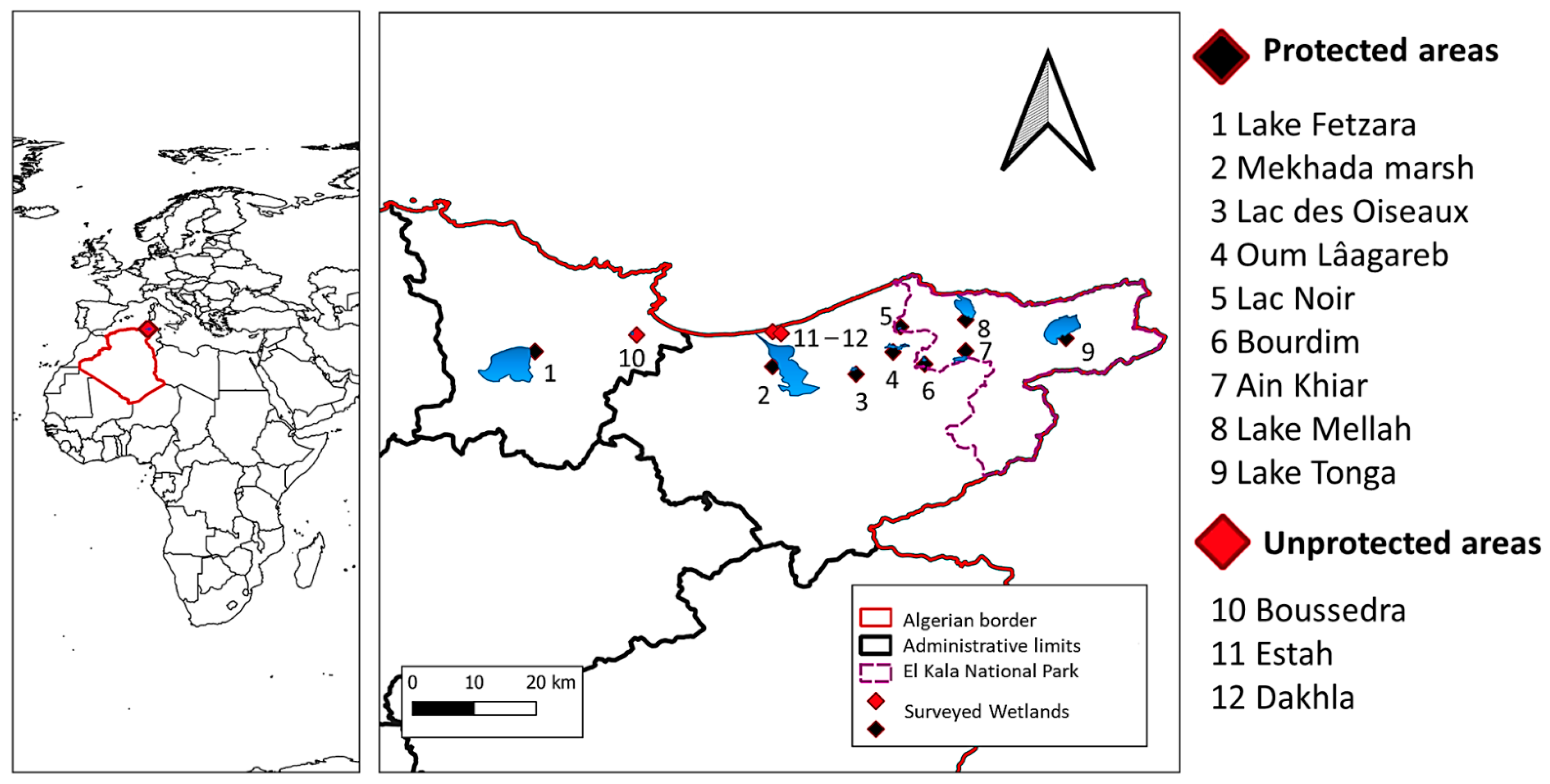

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Design and Data Collection

2.3. Sampling Strategy

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Provisioning Services

3.2. Regulating Services

3.3. Cultural Services

3.4. Sociodemographic Associations

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic Influences on Ecosystem Service Perceptions

4.2. Provisioning Services: The Role of Education over Gender

4.3. Cultural Services: The Dual Influence of Gender and Education

4.4. Integrating Gender and Traditional Knowledge into Conservation Governance of Regulating and Cultural Services

4.5. The Role of Protected Areas in Shaping Perceptions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellard, C.; Bertelsmeier, C.; Leadley, P.; Thuiller, W.; Courchamp, F. Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doney, S.C.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Duffy, J.E.; Barry, J.P.; Chan, F.; English, C.A.; Galindo, H.M.; Grebmeier, J.M.; Hollowed, A.B.; Knowlton, N.; et al. Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eekhout, J.P.C.; de Vente, J. Global impact of climate change on soil erosion and potential for adaptation through soil conservation. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 226, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samraoui, B.; de Bélair, G. Les zones humides de la Numidie orientale: Bilan des connaissances et perspectives de gestion. Synth. 1998, 4, 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Samraoui, B.; Samraoui, F. An ornithological survey of Algerian wetlands: Important Bird Areas, Ramsar sites and threatened species. Wildfowl 2008, 58, 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Benslimane, N.; Chakri, K.; Haiahem, D.; Guelmami, A.; Samraoui, F.; Samraoui, B. Status and distribution of the endangered White-headed Duck Oxyura leucocephala in Algeria: A reassessment. J. Insect Conserv. 2019, 23, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, A.; Schmidt, K.; Ruiz-Frau, A.; Nicholas, K.A.; Bierry, A.; de Vries Lentsch, A.; Dyankov, A.; Joyce, D.; Liski, A.H.; Marbà, N.; et al. Sociocultural valuation of ecosystem services for operational ecosystem management: Mapping applications by decision contexts in Europe. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2245–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-C.E.; Passarelli, S.; Lovell, R.J.; Ringler, C. Gendered perspectives of ecosystem services: A systematic review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 31, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortnam, M.; Brown, K.; Chaigneau, T.; Crona, B.; Daw, T.M.; Gonçalves, D.; Hicks, C.; Revmatas, M.; Sandbrook, C.; Schulte-Herbruggen, B. The gendered nature of ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Adams, B.; Berkes, F.; Ferriera de Athayde, S.; Dudley, N.; Hunn, E.; Maffi, L.; Milton, K.; Rapport, D.; Robbins, P.; et al. The Intersections of Biological Diversity and Cultural Diversity: Toward Integration. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; Vadez, V.; Huanca, T.; Leonard, W.R.; Wilkie, D. Cultural transmission of ethnobotanical knowledge and skills: An empirical analysis from an Amazonian society. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2010, 31, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samraoui, F.; Aouadi, A.; Talbi, A.; Samraoui, B. Socio-demographic correlates of biodiversity perception: The need for environmental education. J. Contemp. Trends Issues Educ. 2022, 1, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Czyżyk, K.; Woźnicka, M.; Dudek, T.; Fialova, J.; Korcz, N. The importance of forest management in psychological restoration: Exploring the effects of landscape change in a suburban forest. Land 2024, 13, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) V5.1: Guidance on the Application of the Revised Structure; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Available online: https://cices.eu (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- De Vaus, D.A. Surveys in Social Research, 4th ed.; University College of London Press: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zalidis, G.C.; Mantzavelas, A.L. Inventory of Greek wetlands as natural resources. Wetlands 1996, 16, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Taguchi, T. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aouadi, A.; Samraoui, F.; Talbi, A.; Souiki, L.; Samraoui, B. Perceived wetland wildlife in a North African urban setting: Conservation implications. Bull. Société Zool. Fr. 2021, 146, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Garcia, E.A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1263–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed.; Stata Press: Lakeway Drive College Station, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. Gender and forest conservation: The impact of women’s participation in community forest governance. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2785–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, T.C.; Powell, B.; Ickowitz, A.; Foli, S.; Pinedo-Vasquez, M.; Nasi, R.; Padoch, C. Food Security and Nutrition: The Role of Forests; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2013; Available online: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/4103/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Tiliouine, H. Gender Dimensions of Quality of Life in Algeria. In Gender, Lifespan and Quality of Life; Eckermann, E., Ed.; Social Indicators Research Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheriet, B. Gender as a catalyst of social and political representations in Algeria. J. N. Afr. Stud. 2004, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Brancalion, P.H.S.; Laestadius, L.; Bennett-Curry, A.; Buckingham, K.; Kumar, C.; Moll-Rocek, J.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Wilson, S.J. When is a forest a forest? Forest concepts and definitions in the era of forest and landscape restoration. Ambio 2016, 45, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgrim, S.E.; Cullen, L.C.; Smith, D.J.; Pretty, J. Ecological knowledge is lost in wealthier communities and countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human–nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjeris, F. Deconstructing gender stereotypes in standardized English language school textbooks in Algeria: Implications for equitable instructional materials. Discourse Stud. 2024, 26, 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. Celebrating and Upholding Indigenous Women—Keepers of Indigenous Scientific Knowledge; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://iucn.org/blog/202208/celebrating-and-upholding-indigenous-women-keepers-indigenous-scientific-knowledge (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Pascual, R.; Piana, L.; Bhat, S.U.; Castro, P.F.; Corbera, J.; Cummings, D.; Delgado, C.; Eades, E.; Fensham, R.J.; Fernández-Martínez, M.; et al. The Cultural Ecohydrogeology of Mediterranean-Climate Springs: A Global Review with Case Studies. Environments 2024, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, D.A. Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity; UNEP and Intermediate Technology Publications: Nairobi, Kenya, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zent, S.; Maffi, L. Final Report on Indicator No. 2: Methodology for Developing a Vitality Index of Traditional Environmental Knowledge (VITEK) for the Project “Global Indicators of the Status and Trends of Linguistic Diversity and Traditional Knowledge”; Terralingua: Atlantic Mine, MI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Battisti, C.; Poeta, G.; Fanelli, G. Non-native species as paradoxical contributors to cultural ecosystem services in urban green spaces: Implications for conservation education. Web Ecol. 2018, 18, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, J.; Gavin, M.C. Perceptions of the value of traditional ecological knowledge to formal school curricula: Opportunities and challenges from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Misiani, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sakwa, A. Traditional ecological knowledge of shifting agriculture of Bulang people in Yunnan, China. Am. J. Environ. Prot. 2020, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavito-Bermudez, D. Biocultural learning: Beyond ecological knowledge transfer. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2134–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, J. The end of the Matriline? The changing roles of women and descent amongst the Algerian Tuareg. J. N. Afr. Stud. 2003, 8, 121–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadgil, M.; Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio 1993, 22, 151–156. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4314060 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Arora-Jonsson, S. Virtue and vulnerability: Discourses on women, gender and climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, L.; Messaoudene, M. Gendered and gender-neutral character of public places in Algeria. Quaest. Geogr. Pozn. 2021, 40, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhi, Z.S. Algerian Women, Citizenship, and the ‘Family Code’. Gend. Dev. 2003, 11, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.E.; Evans, K.L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, I. De la difficulté (sexuelle) d’être une femme célibataire au Maghreb: Une étude de témoignages et d’œuvres d’écrivaines algériennes et marocaines. Mod. Contemp. Fr. 2015, 23, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.G.; Grillas, P.; Al Hreisha, H.; Balkız, Ö.; Borie, M.; Boutron, O.; Catita, A.; Champagnon, J.; Cherif, S.; Çiçek, K.; et al. The future for Mediterranean wetlands: 50 key issues and 50 important conservation research questions. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 276 | 50.0% |

| Female | 276 | 50.0% | |

| Age | 20–60 years | 468 | 84.8% |

| >60 years | 84 | 15.2% | |

| Education | Without formal education | 92 | 16.7% |

| Elementary school | 108 | 19.6% | |

| Middle school | 104 | 18.8% | |

| High school | 162 | 29.3% | |

| University level | 86 | 15.6% | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 184 | 33.3% |

| Employee | 208 | 37.7% | |

| Farmer | 36 | 6.5% | |

| Retired | 24 | 4.3% | |

| Student | 16 | 2.9% | |

| Others | 84 | 15.2% | |

| Residence Status | Protected | 444 | 80.4% |

| Unprotected | 108 | 19.6% |

| Question | Gender Chi2 (p-Value) | Education Chi2 (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1—Usage Frequency | 7.86 (0.16) | 80.71 (<0.001) |

| Q2—Perception of Changes | 12.73 (0.026) | 46.13 (0.03) |

| Q3—Importance to Well-Being | 9.35 (0.15) | 60.29 (0.006) |

| Q4—Policy Adequacy | 2.67 (0.75) | 48.29 (0.018) |

| Q5—Management Challenges | 34.79 (0.05) | 194.32 (0.001) |

| Question | Gender Chi2 (p-Value) | Education Chi2 (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Q6—Concern Level | 1.91 (0.75) | 46.44 (0.003) |

| Q7—Perception of Changes | 16.36 (0.002) | 26.52 (0.32) |

| Q8—Knowledge of Benefits | 6.42 (0.16) | 19.28 (0.73) |

| Q9—Management Challenges | 25.92 (0.16) | 153.00 (0.02) |

| Q10—Policy Adequacy | 1.46 (0.68) | 14.97 (0.66) |

| Question | Gender Chi2 (p-Value) | Education Chi2 (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Q11—Cultural Engagement | 4.22 (0.03) | 16.61 (0.01) |

| Q12—Perceived Importance | 1.18 (0.55) | 21.37 (0.04) |

| Q13—Learning About Significance | 6.19 (0.10) | 27.65 (0.06) |

| Q14—Traditional Ceremonies | 0.05 (0.97) | 30.84 (0.002) |

| Q15—Educational Integration | 0.08 (0.76) | 9.41 (0.15) |

| Q16—Perceived Impact of Loss | 4.71 (0.19) | 17.99 (0.12) |

| Q17—Preferred Promotion Strategies | 8.22 (0.14) | 26.31 (0.01) |

| Test Category | Survey Question | Raw p-Value | Bonferroni Adj. | Bonferroni Reject | FDR Adj. | FDR Reject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning (gender) | Q1 | 0.16 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Provisioning (gender) | Q2 | 0.026 | 0.884 | False | 0.0785 | False |

| Provisioning (gender) | Q3 | 0.15 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Provisioning (gender) | Q4 | 0.75 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Provisioning (gender) | Q5 | 0.05 | 1.0 | False | 0.1133 | False |

| Provisioning (education) | Q1 | 0.001 | 0.034 | True | 0.017 | True |

| Provisioning (education) | Q2 | 0.03 | 1.0 | False | 0.0785 | False |

| Provisioning (education) | Q3 | 0.006 | 0.204 | False | 0.034 | True |

| Provisioning (education) | Q4 | 0.018 | 0.612 | False | 0.068 | False |

| Provisioning (education) | Q5 | 0.001 | 0.034 | True | 0.017 | True |

| Regulating (gender) | Q6 | 0.75 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Regulating (gender) | Q7 | 0.002 | 0.068 | False | 0.017 | True |

| Regulating (gender) | Q8 | 0.16 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Regulating (gender) | Q9 | 0.16 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Regulating (gender) | Q10 | 0.68 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Regulating (education) | Q6 | 0.003 | 0.102 | False | 0.0204 | True |

| Regulating (education) | Q7 | 0.32 | 1.0 | False | 0.4185 | False |

| Regulating (education) | Q8 | 0.73 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Regulating (education) | Q9 | 0.02 | 0.68 | False | 0.068 | False |

| Regulating (education) | Q10 | 0.66 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q11 | 0.03 | 1.0 | False | 0.0785 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q12 | 0.55 | 1.0 | False | 0.6926 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q13 | 0.1 | 1.0 | False | 0.2 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q14 | 0.97 | 1.0 | False | 0.97 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q15 | 0.76 | 1.0 | False | 0.783 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q16 | 0.19 | 1.0 | False | 0.2584 | False |

| Cultural (gender) | Q17 | 0.14 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Cultural (education) | Q11 | 0.01 | 0.34 | False | 0.0425 | True |

| Cultural (education) | Q12 | 0.04 | 1.0 | False | 0.0971 | False |

| Cultural (education) | Q13 | 0.06 | 1.0 | False | 0.1275 | False |

| Cultural (education) | Q14 | 0.002 | 0.068 | False | 0.017 | True |

| Cultural (education) | Q15 | 0.15 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Cultural (education) | Q16 | 0.12 | 1.0 | False | 0.2267 | False |

| Cultural (education) | Q17 | 0.01 | 0.34 | False | 0.0425 | True |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samraoui, F.; Nahli, C.; Snani, S.; Nedjah, R.; Aouadi, A.; Rouibi, Y.; Satour, A.; Samraoui, B. Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Conservation: The Role of Gender and Education in Northeastern Algeria. Land 2025, 14, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071454

Samraoui F, Nahli C, Snani S, Nedjah R, Aouadi A, Rouibi Y, Satour A, Samraoui B. Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Conservation: The Role of Gender and Education in Northeastern Algeria. Land. 2025; 14(7):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071454

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamraoui, Farrah, Chahrazed Nahli, Sarra Snani, Riad Nedjah, Abdallah Aouadi, Yacine Rouibi, Abdellatif Satour, and Boudjéma Samraoui. 2025. "Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Conservation: The Role of Gender and Education in Northeastern Algeria" Land 14, no. 7: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071454

APA StyleSamraoui, F., Nahli, C., Snani, S., Nedjah, R., Aouadi, A., Rouibi, Y., Satour, A., & Samraoui, B. (2025). Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and Conservation: The Role of Gender and Education in Northeastern Algeria. Land, 14(7), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14071454