Abstract

The construction of a fence in the sea made of bamboo sticks along the coastal areas of Tangerang, Indonesia, caused controversy and many public debates in most Indonesian media. The case is, however, not unique. It provides a means to pose three questions related to the following topics: (1) which controversies and contradictions between formal procedures and informal practices related to land and sea rights exist; (2) which values and perceptions of the involved stakeholders play a role in these controversies and contradictions; and (3) which kinds of boundary work or boundary objects could resolve these controversies and contradictions. The theoretical embedding for the subject lies in the theories of territory and space on the one hand and formal institutional models of land and sea on the other. The analytical model used to evaluate the controversies and contradictions is McKinsey’s 7S model, while the data used are extracted from journalistic public media reports and social media. The results show a significant discrepancy between the values connected to formal and informal territorial claims, as well as a lack of enforcement capacity to address this discrepancy. Instead, the policy response exhibits an excessive and uncontrolled discretionary space for all stakeholders to pursue their own interests. The theoretical novelty is that institutional models governing territorial sea and land rights, restrictions and responsibilities need to be aligned and connected based on detecting where and how the values of affected stakeholders can be harmonized, rather than enforcing a unilateral system of values of disconnected systems (of either land or sea). The policy implementation implications are to create stricter procedural steps when providing building permits in coastal areas, with better enforcement and stricter control. Soft governance campaigns should raise awareness of what is allowed and required for coastal building permits and reclamations. Additionally, there could be quicker, more thorough inspections of emerging or hidden practices of non-approved fencing and non-approved occupation of coastal land and sea.

1. Introduction

The construction of a fence in the sea made of bamboo sticks along Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia’s coastal areas, was controversial and broadly discussed in most Indonesian media. The fence reached a length of more than 30 km and became visible to the local population via aerial and satellite images. The fence closed off a bay to local fishing traffic and appeared to be an initial delineation of what looked like a reclamation plan. Various stories emerged about who constructed this fence and why. Moreover, questions emerged, such as the following: who authorised this construction, and why was the local population apparently not involved in the planning and evaluation of its possible impacts? Was there a plan at all, and had rights and responsibilities already been surrendered or allowed outside standard institutional and legal procedures? Was this a unique case of apparently informal or extra-legal demarcation of sea territory, or was this a signal that a broader process is taking place whereby individuals and private and/or public organisations can claim and demarcate sea and land rights themselves rather than rely on officially approved procedures and participatory, inclusive processes? If so, are alternative institutional processes emerging alongside the formal ones, or in the absence of effective formal ones?

Addressing and understanding these questions is part of broader scientific discourses on coastal governance, marine spatial planning, and rural coastal land tenure security. Whereas marine resources from seas and oceans are for companies and governments the new frontiers of economic development, for others, such as rural coastal communities, there are significant risks of not equally benefiting from the share of gains and profits generated by these investments [1]. Moreover, rural coastal communities are, on average, more vulnerable than inland and urban communities, as they also have to cope with the effects of climate change [2], global ocean pollution, unequal spatial development [3] and land grabbing. Hence, there is a need to balance and optimise blue growth and blue justice with sustainable and responsible marine and blue governance.

A core issue here is how rights, restrictions and responsibilities are understood in these debates. This depends on both practices and legalities concerning land use planning of coastal zones and the allocation of spatial land and marine rights. On the other hand, it depends on adequately identifying which economic opportunities exist in the coastal space, defined by territorial and institutional boundaries. Currently, however, many of the historically developed practices of local communities are under pressure due to global challenges and rapid migration rates, as well as insufficient attempts by coastal investors and developers to use the knowledge and experiences of local communities. This can lead to unexpected territorial claims and controversies, such as the emergence of sea fences, which cannot directly be traced to any rational and/or community-based planning process with an associated allocation of rights, restrictions and responsibilities.

This article starts by developing a theoretical contribution regarding the connection of land and sea rights. It draws on two theoretical modelling perspectives: a territoriality and spatial perspective on the one hand, and an institutional perspective on formality and informality on the other, understood within the Indonesian legal and institutional context of land and sea rights. Both perspectives serve as a basis to describe and categorise the subsequent emerging practices of the specific case of the sea fences in Tangerang (using information available through recent and accessible documentation). With these descriptions, the main aim of the study is to generate a better understanding of the institutional connections between land and sea rights. Specifically, the study analyses the following questions: (1) which controversies and contradictions between formal procedures and informal practices related to land and sea rights exist? (2) Which values and perceptions of the involved stakeholders play a role in these controversies and contradictions? (3) Which kinds of boundary work or boundary objects could resolve these controversies and contradictions? The structure and categorisation of empirical data and the subsequent analysis use McKinsey’s 7S model, which is introduced in the methodological section. After this follows a discussion and interpretation with regards to the main research questions.

2. Theoretical Embedding

The theoretical embedding starts by viewing land and sea from the perspective of territoriality and space. From this conceptualisation, one can describe how Indonesia has regulated their territory and space of both land and sea.

2.1. Territoriality and Space

Territory refers to the authority and responsibility of a certain space within boundaries. Territoriality refers to the process of establishing ownership and control over a space, whether it is a physical location or a broader neighbourhood [4]. A key factor is the debate about the legitimacy of control over space. The debate around its legitimacy is the question of the extent to which the physical environment interacts with social factors to shape an individual’s behaviour. Or, in other words, once any actor claims a space, when or how will that claim become legitimate, legal or illegal, and which authority has the mandate and the adequate enforcement power to rule over this space, even if this means involuntary eviction?

The conventional manner of gaining and documenting legitimate claims or formal rights is either by adjudicating or delineating these rights, followed by cadastral mapping and registration and/or recording process in a formally recognised legal database. It is also common to use Land Administration Domain Models (LADMs), in which the actors, space, rights, restrictions and responsibilities are described and formally connected. Similar models exist for sea or marine rights [5].

There are, however, several situations in which the conventional approaches to the legal recognition of land or sea rights are challenged. In coastal areas affected by tidal floods, formally registered land may become permanent or semi-permanent sea space. Labh [6] lists how much land Archipelagic countries may lose due to climate change-induced sea level rise. Countries such as Tuvalu, Seychelles and the Maldives may be reduced significantly in total territory. Legally, this also implies that in these cases, the land rights of the lost land may still exist, at least for some time, until there is a formal declaration that space has become sea instead of land [7]. This declaration automatically changes the spatial authority, as different ministries or agencies are mandated to allocate rights, restrictions and licenses over sea or coastal areas instead of land areas.

Another situation concerns reclamation. This changes the control over a space in the other direction, from the sea or water bodies to land agencies and municipalities. The newly reclaimed land typically becomes subject to the same landownership laws as existing land, meaning it can be owned, sold or used under local regulations. The reclaimed land can be subject to zoning laws and development regulations, like other land areas. Land reclamation reduces the sea area as the former seabed becomes land, impacting the extent of the territorial sea and other maritime zones. Land reclamation can have implications under international law, particularly concerning the delimitation of maritime boundaries and the rights of coastal states. A documented dispute concerning the Spratly Islands between China and the Philippines questions under which conditions a reclaimed area previously regarded as a low-tide elevation or a rock landmass without any economic or international territorial status becomes an island with territorial rights [8]. Besides the recognition of land or sea rights, reclamation projects are often subject to environmental legal restrictions aimed to minimize their impact on the marine environment.

A third situation, which confounds who has control over space, concerns the construction of houses on or on top of the water. Ref. [9] describes how the Bajau tribe in Indonesia construct their houses and entire community areas on top of water or sea areas. Culturally, they are one of the sea nomad tribes of Southeast Asia who regard their residential area and their livelihood as the sea itself. Living in close harmony with the sea’s characteristics, they have a communal sense of property. From a land registration point of view, the ownership or land rights of the community members are difficult to register, as the properties are not on land and thus cannot be connected to coordinates on land. Ref. [10] argues that their rights can be protected through so-called HGB rights, which in Indonesian land law refers to the right to build and own buildings on land that is not theirs. In the case of the Bajau tribe, these HGB certificates were provided for a maximum period of 30 years, with an extension possibility of 20 years. According to Article 35 of the Indonesian land law, such building rights can even be transferred to any third party, and the right can be upgraded to a Freehold title by applying to upgrade the status of Land Rights under applicable laws and regulations. Similar is the situation in the Netherlands, which registers so-called ‘woonboten’ (houseboats) as legal ownership in the public register of properties but cannot register the exact location of these. It may use the mooring for property tax or valuation purposes.

A last comment on the lawful or unlawful claiming of land or sea concerns the activities of fencing and fencing off. Ref. [11] describes how large landscapes of grazing land are being fenced off in Kenya to exercise influence and power in a conflict over statutory and pastoralist land tenure. They argue that ‘While fences fill in landscapes, and grazing restrictions are set within (still unfenced) conservancies, the dependency on the commons may sooner or later push these hybrid pastoral practices to a point where their grazing practices are no longer compatible with a fully fenced landscape’. In other words, fencing is a means to control space yet ultimately leads to a tragedy of the commons or the public benefits.

From these quandaries and contradictions, one can derive the following key adapted principles of territoriality and space with a specific reference to integrating land and sea rights, restrictions and responsibilities:

- The current spatial boundaries between land and sea create an institutional vacuum and overlap, contradicting operational procedures and expectations. These can be interpreted as co-existing institutional frameworks, leading to either discretionary or opportunistic decisions about which framework to apply to benefit individual interests, or to legal plurality where individuals and stakeholders may be subjected to different rules, which can lead to conflicts, injustices and decreased trust in state-based regulations and operations. To overcome these quandaries, the control over land and sea should be interconnected and reflect both a spatial and legal continuum. This can be the basis for a single (omnibus) law.

- Coastal governance is currently an assembly of land use planning and marine spatial planning. In their execution, these planning systems are disconnected, leading to overlaps and gaps in spatial allocations and distribution of rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Spatial planning laws and regulations should integrate procedures considering all values and claims from all affected stakeholders on land and sea.

- There is a fundamental difference between models of ownership and use on land or on sea, resulting in different types of rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Connecting these two in a single framework is needed, but would also require a novel understanding of how to model the spatial entities, as well as how to assign and qualify rights. For example, hybrid and dynamic spatial entities may be required for hybrid constructions on land and sea.

2.2. Institutional Models of Land and Sea Rights in Indonesia

Land and sea rights are typically managed in two separate institutional systems: spatial planning and land administration (including cadastral surveys and registration of land rights, restrictions and responsibilities) and ocean, marine and fisheries management. On top of that, local and regional coastal governments manage the coastal spaces. Analysing how such systems operate can rely on various logics and principles, which determine inter-and intra-organisational and institutional relations and interactions. The formal rules prescribe the expected ‘humanly devised constraints in behaviour’, whereas the de facto practices reveal the ‘rules, norms, and social structures created by people that shape and limit individual behaviour within a society’ (using the classical definition of [12]). Comparing how and why these differ can reveal the causes and effects of controversies and contradictions.

The formal procedures in Indonesia to obtain ownership, use, building rights, licenses, etc., and decide on responsibilities, restrictions, ramifications, sanctions, penalties over non-compliance with land and sea laws, etc., depend on different laws which overlap and interact. Table 1 describes these laws:

Table 1.

Formal land-related procedures in Indonesia.

According to Indonesian law, maritime and terrestrial areas are governed under different spatial jurisdictional authorities. Terrestrial areas fall under the authority of the Ministry ATR/BPN, the government body authorised to issue land certificates, including SHMs and SHGBs. Generally, SHMs and SHGBs are issued by local Land Offices. However, for SHMs with an area exceeding 3000 m2 (non-agricultural land) or 50,000 m2 (agricultural land), and SHGBs exceeding 3000 m2 (for individuals) or 20,000 m2 (for legal entities), the authority to grant the rights is vested in the Regional Office or Central Government. Furthermore, the authority over spatial conformity differs between terrestrial and coastal areas. For land in terrestrial areas, spatial conformity refers to the Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW) or the Detailed Plan of Spatial Planning (RDTR) issued by the Local Government, or to the National RTRW if the area is designated as a National Strategic Area (PSN). Meanwhile, for coastal areas, the spatial conformity refers to the Zoning Plan for Coastal Areas and Small Islands (RZWP3K), which falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of KKP. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) may also be involved in environmental impact assessment, particularly concerning conservation areas. However, granting SHMs and SHGBs in coastal areas requires a Location Permit from the Ministry of KKP, ensuring its alignment with the RZWP3K and approval of Marine Spatial Utilisation Suitability (KKPRL). If the land originates from reclamation, it must be accompanied by a Reclamation Permit issued by the Governor or Minister of KKP. We further present a comparison of land certificate issuance (SHMs and SHGBs) between terrestrial and coastal areas, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison between the issuance of land certificates (SHMs and SHGBs) in terrestrial and coastal areas.

While Indonesian law provides a comprehensive framework for land and marine spatial planning, contradictions frequently emerge in its implementation. The ‘Pagar Laut’ case illustrates the regulatory tensions arising from fragmented spatial governance in Indonesia’s coastal areas. While the Ministry of ATR/BPN holds authority over land certification (SHM, SHGB), spatial conformity in coastal and marine zones falls under the Ministry of KKP through the RZWP3K and the KKPRL mechanism. This duality often results in overlapping jurisdictions, where land titles might be granted without sufficient alignment (or permit) with marine spatial planning, resulting in permits or land rights being issued in coastal zones without alignment across planning regimes. In cases involving reclaimed land, this creates legal pathways for privatisation (such as the case of ‘Pagar Laut’), despite their social or ecological contestation. The lack of harmonised planning between terrestrial (RTRW/RDTR) and marine (RZWP3K) systems, compounded by weak enforcement and limited recognition of customary marine tenure, further exacerbates community-developer conflicts and undermines sustainable coastal governance, leaving the traditional users vulnerable to exclusion. These tensions reflect a broader structural gap between legal design and enforcement capacity, as well as a lack of integrated governance across land–sea boundaries.

3. Materials and Methods

To understand how, when, where and why the controversies and contradictions connected to the ‘Pagar Laut’ emerged it was first important to retrieve as much as possible the facts that could describe in which geographical context the ‘Pagar Laut’ was constructed and to generate a timeline of the reports and reported events. As the documentation on the issue was relatively limited in the scientific literature and publicly accessible government reports, the methodology of data collection relied on a systematic search for grey literature, consisting of reliable and reputable journalistic media, websites and hard copy publications, as well as on the social media tags #pagarlaut. Inclusion criteria required the following: that articles of publications (1) discussed the ‘Pagar Laut’ either directly or in relation to broader issues such as marine governance, land and sea rights or environmental and natural resources management; (2) that they originated from reputable media outlets, verified community platforms, academic blogs or official government communications; and (3) that they provided identifiable authorship or clear institutional affiliation. Reliability was assessed through triangulation by cross-verifying information across at least two independent sources and evaluating each source for internal consistency, author or institutional credibility, as well as the absence of overt bias.

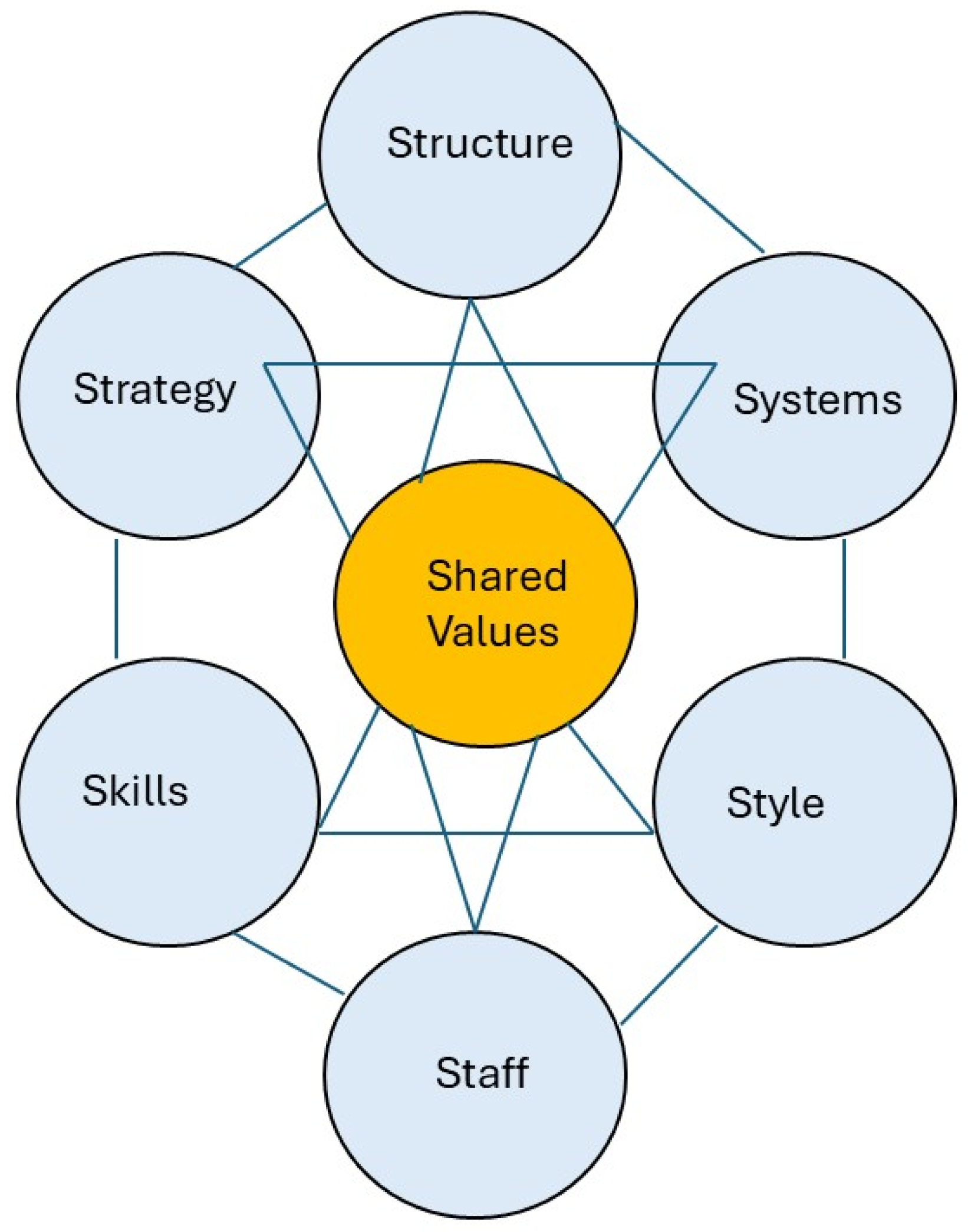

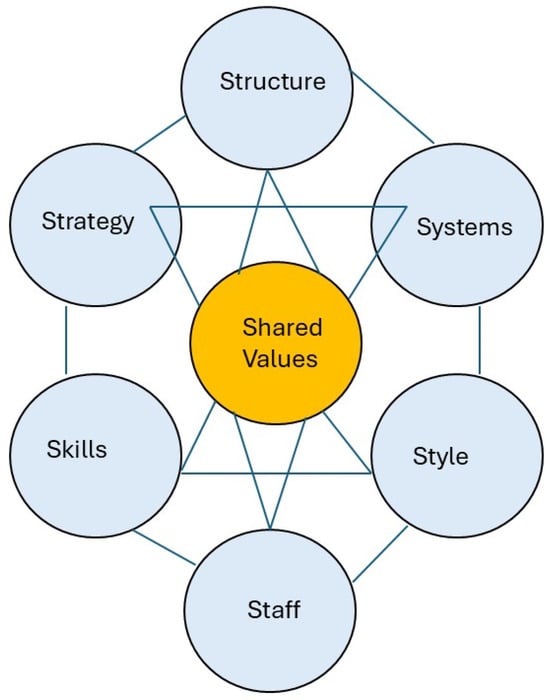

Once these were collected, an interpretative review took place to address the research questions more specifically. This interpretation was based on a set of prompts derived from the McKinsey 7S Model [13,14,15]. Although this model has not yet been utilized in describing modelling spatial conflicts, such as the use of stakeholder analysis, participatory rural appraisals, logical framework analysis or multi-criteria analysis, it has specific characteristics which make it suitable for generating a broader perspective of why and how the conflicts arise and where potential exists for resolving the conflicts. Compared to conventional stakeholder analysis, the 7S model views the stakeholders’ values and intentions from a broader structural and organisational perspective. Compared to participatory rural appraisals, this model not only involves particular groups to identify and map areas of conflict and potential solutions but also considers a broader group of affected actors, stakeholders and beneficiaries into account in their operational environment. Compared to logical framework analysis or multi-criteria analysis, the model does not assume the full rationality of actors in optimising mediated solutions but rather reasons from a bounded rationality in an operational context. For this study, the model served as an analytical model to evaluate the actual practices of controversies and contradictions arising from the differences between formal procedures and informal practices related to land and sea rights. This model connects the behaviour and perceptions of interrelated stakeholders through the 7S’s, which represent Structure, Strategy, Skill, System, Shared Values, Style, and Staff (presented in Figure 1). The 7S model posits that organisations, or organisational systems, succeed and perform well when all these factors align and mutually reinforce each other. Analysing where the factors do not align makes it possible to find causes for the controversies and contradictions and starting points for improving, regulating or re-engineering the organisational system.

Figure 1.

The McKinsey 7S Model.

We used a deductive thematic analysis to map the data onto the 7S framework. Each of the seven elements was allocated to a predefined analytical category. Relevant text excerpts from the collected grey literature, social media content, and official documents were coded manually into one or more of these categories. For example, descriptions of stakeholder roles, institutional hierarchies, or bureaucratic channels were coded under the Structure category, while statements reflecting motivations, tactics, or advocacy approaches were mapped under Strategy. Mentions of customary law, traditions, or social norms/values or legal frameworks were categorised as Systems, and references to specific capacities or knowledge (such as traditional ecological practice or legal expertise) were assigned to the Skills category. The Staff category captured the individuals or actors mentioned, while Style referred to their modes of communication or engagement and Shared Values reflected underlying principles, norms or cultural orientations. Where data segments addressed multiple dimensions, dual or cross-category coding was applied. This process allowed for a comparative analysis across stakeholder groups and enabled the identification of both alignment and contradiction among the elements, contributing to a deeper understanding of the root causes of the observed tensions.

Following the thematic coding using the McKinsey 7S framework, a comparative alignment matrix was developed to visualise the degree of convergence or divergence among stakeholder groups across each of the seven elements. The matrix employed a colour-coded system to indicate three levels of alignment, which are green (aligned), yellow (partial/mixed alignment) and red (conflicting or misaligned). Alignment judgments were based on two criteria: (1) substantive convergence, referring to whether stakeholders used similar systems, values or structures; and (2) functional compatibility or conflict, which refers to whether stakeholder actions, strategies or institutional roles supported, ignored or obstructed one another. The matrix was populated using synthesised evidence from the coded data and illustrates how differing institutional logics, operational strategies and value systems contribute to the contradictions and controversies surrounding the ‘Pagar Laut’ issue.

4. Results

4.1. Study Site

The sea fence spans approximately 30.16 kilometres along the coastal waters of six sub-districts and 17 villages within the Tangerang and Serang Regencies. Positioned about 200–500 m offshore, the barrier extends from Teluknaga to Kronjo. The surroundings primarily consist of swamps, fishponds and mangrove forests. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the sea barrier, with an example of the existing conditions in Kohod Village, which has been at the centre of the media coverage and the discussion in this paper.

Figure 2.

Indicative sea fences’ location, delineated from Google Earth on 12 April 2025 and presentation material from the Directorate General of Spatial Planning, Ministry of ATR/BPN. The site photos were obtained through on-site field surveys.

4.2. Sequence of Events

The Indonesian newspaper Kompas reported on 23 January 2025 that since early January 2025, the public had witnessed and been shocked by the discovery of a mysterious 30.16-km sea fence in the waters of Tangerang Regency, Banten [16]. The sea fence is reportedly made of bamboo that is stuck into the seabed. The initial issue surrounding the mysterious coastal fence was the illegal and unlawful reclamation of coastal waters, which later expanded to include environmental, socio-economic and coastal management concerns. The report further stated that several authorities had intervened in dealing with the sea fence, from the local government to the central government. Some parties admitted to having a role in constructing the sea fence, while others denied it. Also, several officials’ names were dragged into the vortex of the Tangerang Sea fence case.

At roughly the same time, a report from the VOI reported that the Indonesian Ombudsman (ORI) had investigated the case [17]. The ORI concluded that the 30.16 km long sea fence affected 16 villages in six sub-districts, including Kronjo, Kemiri, Mauk, Sukadiri, Pakuhaji and Teluknaga. This area is included in the general utilisation area regulated by Regional Regulation Number 1 of 2023. This area covers critical zones such as fishery capture, fishing ports, tourism and energy management. These reported facts triggered discussions and critical remarks by experts, practitioners and politicians. A marine expert from Airlangga University, Prof. Mochammad Amin Alamsjah, emphasized that the fence contradicts Article 33 paragraph 3 of the 1945 Constitution, which states that the state controls the sea and the natural resources within it for the welfare of the people [18]. The legal argument is that the sea fence violates this law and can potentially damage the marine ecosystem: “This fence can accelerate sedimentation, damage fish habitat, and threaten the life of marine biota such as coral reefs and seagrass beds”. Another impact was that local fishermen had difficulty going to sea because their access was restricted. As a result, they needed to look for new locations that were further away, required more money, and contributed to the decline in fish yields: “If this sea fence remains, fishermen will have more difficulties. Productivity decreases, and their economy can be disrupted,” stated Prof. Amin.

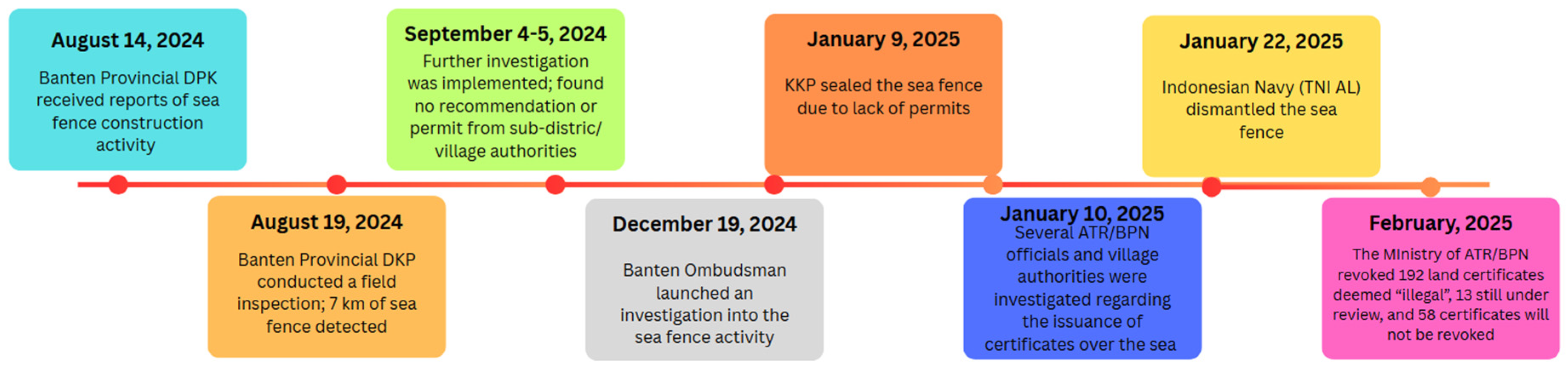

Despite reaching national notice in early 2025, officials were aware of the sea fence’s existence some months previously. The Banten Provincial Marine and Fisheries Office (DKP) first received a report concerning the structure on 14 August 2024. Five days later, a field inspection revealed that the fence at that time extended approximately 7 kilometres. In early September 2024, DKP Banten, in coordination with the Civil Service Police Unit (Polsus) from the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (KKP), conducted further site visits and discussions. Findings revealed that the construction lacked official recommendations or permits from local sub-district or village authorities. Shortly thereafter, the Ministry of KKP sealed off the structure, citing the absence of a Coastal and Small Islands Zoning Utilisation Permit (KKPRL) and its location within designated Capture Fisheries and Energy Management Zones.

Further investigation revealed that several land certificates had been issued in the coastal fence area, comprising 263 plots with Building Use Right (SHGB) status—258 owned by private entities and 9 by individuals—and 17 plots held by individuals with private rights (SHM). In a press conference on 30 January 2025, the current Minister of ATR/BPN, Nusron Wahid, stated that nearly all of these certificates were issued through the conversion of traditional land rights (girik) that had been issued in 1982, indicating that no new land rights had been granted. Moreover, as the certificates were issued between 2022 and 2023, less than five years since the issue arose, they may be revoked directly without court proceedings due to administrative irregularities [19]. In February 2025, the Ministry of ATR/BPN revoked 193 certificates deemed illegal due to procedural errors, while 13 remained under review and 58 were not revoked.

While some parties have claimed that the sea fences were constructed on submerged land to prevent coastal abrasion, Gadjah Mada University (UGM) experts have refuted this assertion. A study conducted by the UGM team, using satellite imagery, indicates that the area has historically been part of the sea. The imagery reveals that since 1976, the shoreline has remained hundreds of meters away from the current location of the sea fences. This pattern persisted through 1982. Although there have been some land certificate claims, the satellite data consistently shows that the area has never constituted dry land. Further analysis using Sentinel-2 satellite data suggests that the sea fence was likely constructed around May 2024 [20].

There were also significant debates on the fences’ legality and the information’s transparency. There were serious allegations of permits being obtained through questionable means. The issuance of SHGB and SHM titles for the contested area suggests possible legal manipulation and land mafia practice. According to the Agrarian Reform Consortium (KPA), the subdivision of SHGB into smaller plots was mostly intended to allow registration at the local Land Office (district level), bypassing central government oversight. Furthermore, SHGB titles cannot legally be issued over marine areas, as stipulated in Government Regulation No. 18/2021 in conjunction with Ministerial Regulation Number 18/2021. KPA also noted potential alterations to land and marine spatial planning at the local government level, which may have shifted coastal boundaries, enabling the issuance of location permits (PKKPR) to support SHGB registration [21]. The progression of the case is further illustrated in the timeline presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Chronological overview of the major events and milestones related to sea fences’ case.

Besides the newspaper and grey literature articles, the online discussions with #pagarlaut demonstrated a range of strong opinions. Drawing on the information gathered, the key controversies are related to environmental damage, anticipated impact on local fishermen, issues of legality and transparency and mere conflicting interests of stakeholders. The debates showed the conflicting interests of stakeholders. The controversy highlights the tension between economic development and environmental protection. Critics argue that the ‘Pagar Laut’ projects prioritise the interests of investors over the well-being of local communities and the environment. The environmental damage controversy is based on the concern that the fencing structures could potentially harm the coast. The critique was that the fences disrupt the natural water flow, leading to sedimentation and damage to marine habitats. This disruption also poses a threat to the biodiversity of the area, affecting various marine species. From the perspective of local fishermen, the main problems were that the ‘Pagar Laut’ structures had been accused of obstructing traditional fishing routes and access to fishing grounds. This directly impacts the livelihoods of local fishermen, who rely on these areas for their sustenance. Those fishermen feel they are being kept out of their own “home”. The development of ‘Pagar Laut’ should be carried out with greater transparency and inclusive public engagement, and it is essential that such initiatives consider the interests of multiple stakeholders, including local fishers and coastal communities [22].

The lack of transparency in the planning and construction fuelled suspicion and distrust among local communities. There were also allegations of corruption. The ‘Pagar Laut’ issue drew attention from high-ranking officials, indicating the seriousness of the situation. There are calls for thorough investigations and legal action against those responsible for illegal activities. Some expressed the feeling that a “mafia” is controlling the progress of these projects, which could have legal and political ramifications.

4.3. The Stakeholders Related to 7Ss in the ‘Pagar Laut’ Case

Table 3 presents the stakeholders—persons or institutions—who are involved in the ‘Pagar Laut’ issue.

Table 3.

Stakeholders involved in the issue of ‘Pagar Laut’.

While Table 3 outlines the roles of each stakeholder, their interactions reveal power asymmetries that shape the outcomes of the ‘Pagar Laut’ controversy. Government bodies such as the Ministry of ATR/BPN and KKP hold formal authority over land and marine governance, enabling them to issue certificates and define spatial boundaries. The governments also have the authority to revoke land rights or permits, a power that is particularly relevant after this case gained national attention. However, institutional fragmentation and overlapping jurisdictions between terrestrial and marine authorities often create loopholes that can be exploited for legal abuses or conflicts of interest in managing the coastal area. Local communities, particularly fishermen/fishing communities, are at the lowest end of the power hierarchy. Despite their deep-rooted dependence on the area, they lack formal recognition in the decision-making process and often find their customary rights excluded from official spatial plans and consideration in granting permits. Their interactions with government officials are largely reactive and occur after decisions are made. On the other hand, village authorities, such as the head of the Kohod Village, play a mediating role between higher government authorities and the local community. In the ‘Pagar Laut’ case, his involvement included the approval of preliminary documents that enabled the land certification, despite lacking full authority over coastal spatial planning. Their role is administrative but constrained, operating in a context of asymmetrical power where district, provincial or ministerial actors make the final decisions.

Organisations and experts play intermediary roles by amplifying community concerns and pressuring state institutions, but their influence depends on public visibility and political receptiveness. Developers, on the other hand, benefit from strong access to legal and administrative processes, often backed by financial resources and formal documentation, creating a structural imbalance in their favour. As for law enforcement/legal authority, such as the Ombudsman, they act as regulatory enforcers. Their effectiveness often depends on political will and institutional clarity. Their authority is substantial, but enforcement can be selective, influenced by jurisdictional ambiguity or high-level directives. As for the media, it serves as a powerful non-state actor, shaping the narrative. It amplifies local grievances, highlights inconsistencies in official statements and pressures institutions to act. Although the media do not have formal decision-making power, they play a key role in influencing public opinion and catalysing accountability, especially in cases where state responses are slow or opaque.

4.4. The 7S Values

Analysing the stakeholders of the ‘Pagar Laut’ issue for similarities in behaviour, strategy, skills, systems, values, presentation styles and staff reveals a complex picture of convergence and divergence. While some actors—such as local communities, civil society organisations and environmental experts—shared values rooted in ecological sustainability, transparency and social justice, other actors, including certain government bodies and private developers, appeared driven by growth-oriented or profit-maximising strategies. Structural and systematic fragmentation among institutions has led to inconsistencies in the application of land and marine spatial regulations, with varying levels of institutional and legal capacity across actors. Although operating within a common bureaucratic structure and legal framework, government bodies differ in their effectiveness and public engagement approaches. They generally require legal expertise and public communication skills. Local communities rely heavily on local knowledge and uphold values related to traditional livelihoods and cultural preservation. Organisations and experts primarily engage in research, advocacy and legal reform. Developers and private companies, by contrast, emphasise legal compliance, financial planning and professional stakeholder presentations. These differences are also reflected in strategic and skill-based approaches: developers and officials leverage legal, financial and economic tools, while civil society actors rely on advocacy, grassroots mobilisations and traditional practices to assert their rights. Communication styles further illustrate these divides, with formal bureaucratic discourse often clashing with affected communities’ direct, emotive expressions. We summarise the findings of the seven values of all involved stakeholders in Table 4.

Table 4.

7S values of all involved stakeholders.

Furthermore, we also present a colour-coded matrix in Table 5 to visualise stakeholder alignment with or divergence from each of the seven elements. Red colours represent the highest distance (or lowest likelihood) from reaching a consensus on this issue, orange represents a partial alignment, and green implies the highest probability of reaching a consensus. The assessments in this table are based on how firm and strict or inert each stakeholder is on the specific aspect, and the colour codes are based on interpretations of documented evidence.

Table 5.

The color-coded matrix visualizing stakeholders alignment and divergence on each 7S elements.

This matrix shows that government institutions and companies/developers tend to operate within formal legal frameworks and structured hierarchies. However, their goals and strategies often diverge. While governments are expected to prioritise policy enforcement and uphold public accountability, developers are primarily motivated by profit and project delivery deadlines. Additionally, overlapping authorities and jurisdictional ambiguities within government situations often result in internal misalignment, inconsistent enforcement, and conflicting interests among officials. Local communities, in contrast, rely on informal structures and traditional knowledge systems, which frequently place them at odds with both state-led and corporate approaches. NGOs and experts occupy a semi-formal role, advocating for community rights through legal, research-based and public awareness strategies. They partially align with both institutional and grassroots perspectives but face limitations in bridging systemic gaps due to limited enforcement capacity, lack of formal authority and structural power imbalances between stakeholders. On the other hand, local communities are often the most in conflict with formal systems, not only due to the lack of legal recognition for their traditional land and sea rights, but also because of the emotional and cultural disconnection caused by top-down governance. Their ties to customary practices and collective identity frequently clash with bureaucratic procedures that overlook local voices and on-the-ground experiences.

5. Discussion

The analysis reveals key contradictions, boundaries and areas in terms of reaching potential consensus. The subsequent subsections address these.

5.1. The Relevance of Shared Values

Firstly, significant contradictions emerged, particularly in the domain of shared values. Government bodies and organisations generally prioritise legal frameworks, regulatory compliance, public accountability and public interests. In contrast, developers prioritise profit and efficiency, and local communities emphasise cultural preservation, environmental sustainability and traditional livelihoods. These differing values result in significant rigid and fixed positions and hence conflicts in relation to the sea fence issue.

5.2. The Implications of Cultural and Organisational Boundaries

Secondly, clear cultural and organisational boundaries exist between stakeholders, especially in structure, style and strategy. Government institutions and developers operate in a nodal cooperation culture through a formal, hierarchical system with structured communication and strategic planning. In contrast, communities often function through informal networks, relying on direct action, pragmatic and ad hoc cooperative structures and emotive appeals. This divergence in operational systems and communicative approaches reinforces divisions and can hinder mutual understanding and boundary work. The informal nature of community organisation can also limit their ability to develop and implement structured strategies, especially when engaging with institutional stakeholders. Without formal frameworks, the community may struggle to maintain consistency, coordinate efforts or gain legitimacy in policy discussions, further widening the gap between them and more institutionalised actors.

5.3. The Effects of Different Communication Styles

Thirdly, communication styles vary significantly among stakeholders, from formal government statements to emotional community protests. The rigidity of structures and systems in which the actors operate and interact influences the shared values in the operationalisation of strategies. Discretionary spaces of decision makers and strategists expand and open the possibilities for opportunistic behaviour and corruption. If the desired results cannot be achieved via formal processes, actors start to reach their goals via informality and possibly illegality. Additionally, multiple narratives start to emerge with processes of reframing, blaming and shaming. Such novel strategies may conceal the strategic informality and illegality. A panel discussion aired on YouTube revolved around the contrasting perspectives of the police and prosecutors, with the police focusing on document forgery and the prosecutors leaning towards corruption. The panel highlighted the importance of collaboration between the police and the prosecutor’s office, potentially with KPK assistance, to resolve the case effectively and transparently. The panel expressed public concern over the release of the suspect due to the expiration of the detention period, emphasising the need for justice and accountability. They stress that focusing on corruption charges could reveal a broader network of involved parties beyond the initial four suspects. Ultimately, they urge the police to align with the prosecutor’s direction by investigating forgery and corruption to ensure a thorough and credible legal process.

5.4. The Strategies of Reaching Consensus and Seeking Boundary Objects

Fourth, while Table 5 highlights the differences between the 7Ss and difficulties in reaching consensus, Table 5 is also helpful in assessing the potential for so-called boundary objects or boundary work to start or create a dialogue to resolve the differences [23,24,25]. Similar to other studies on resolving coastal land use planning conflicts, such as [26,27], the use of the 7S framework aims at identifying and diagnosing problems on the one hand and using this information to mediate conflicting land and sea use claims on the other. Yet, different from these studies is that the 7S framework describes the stakeholders’ values in a broader interconnected context of organisational and societal factors, and uses this context also to seek practical as well as institutional solutions. This approach helps to identify the boundary objects from the perspective of similar operational subjectivities, rather than from the perspective of rational economic models [26] or more abstract policy objectives [27]. This could, for example, start by identifying which staff from different stakeholders have a similar educational or geographical background, which could serve as a basis for boundary work. These similar backgrounds may epistemically and/or emotionally connect staff members of various stakeholders and thus create a fundamental willingness to move forward and adapt their positions in the debate. It may also be a start for further information exchange and transparency in what is expected and what is being achieved and debunk some of the narratives emerging in regular and social media. Another anchor to foster boundary work is to start the exchange of formal academic/scientific knowledge and information, visible and manifested in longitudinal geospatial information (for example, with multi-year remote sensing), with historical community-based experiences of managing the land and water in coastal areas. Connecting these through open and iterative dialogues could generate new perspectives and chances for the development and relevance of coastal areas.

5.5. The Implications for Further Research

Finally, this study contributes to empirical and theoretical insights into ongoing debates on coastal governance by examining how territoriality, institutional authority and legal frameworks interact in hybrid land–sea spaces. By foregrounding the Indonesian case, particularly through the lens of coastal reclamation, informal marine occupancy and intersecting planning regimes, it contributes to territoriality in fluid geographies, institutional failures in spatial governance and legal pluralism in coastal areas. In contrast to traditional land-based territoriality, which is defined by stable boundaries and state control, coastal spaces in Indonesia exemplify a more fluid and contested form of spatial control. Actors such as Bajau communities and private developers (in the case of ‘Pagar Laut’) exercise overlapping territorial claims that are not easily captured by existing land–sea divisions. The institutional implications of the fluidity of the land–sea spaces imply that new types of legal spaces need to be defined, both as three-dimensional legal spaces and as legal spaces with dynamic and extendable boundaries. The former is similar to governing and allocating rights to communal urban spaces and shared apartment rights, whereas the latter is similar to governing pastoralist and indigenous principles of spatial rights. Combining these into one system thus requires rethinking the absoluteness of property rights, both in registering the boundaries (i.e., introducing marine and land cadastres with fuzzy boundaries or using combined land and sea plots) and registering land rights, restrictions and responsibilities (i.e., using new types of use and possession rights).

6. Conclusions

The analysis reveals that there is no shortage of laws and rules to regulate land and water rights, restrictions and responsibilities. Nevertheless, the case of the sea fence also demonstrates that these tend to contradict each other. This is rooted in the legal ambiguity when referring to coastal spaces, which include terrestrial areas immediately adjacent to moving coastlines and coastal water areas where land-based constructions are planned. Additionally, spatial land use plans affect land and water institutional mandates differently, creating ambiguity in the responsibilities and thus creating flexible and opportunistic strategies for all stakeholders, which may not serve the public interest. The controversies occur especially in the operationalisation of the strategies and the mandates of the different organisations, as they operate with varying systems, staff and styles, which are so rigid that reaching consensus is difficult. On the other hand, it also opens discretionary spaces for the involved parties, which creates the potential for bypassing formal rules, opting for informality and ultimately for corruption.

The values of the involved stakeholders which play a role in the controversies and contradictions are the perceived obviousness of adhering to the rule of law, the perceived necessity of public interests, the perceived relevance of cultural heritage, the perceived relevance and urgency of environmental sustainability and social justice and the perceived priority of profit maximisation and cost efficiency. As stakeholders rank these values in different orders, they pursue their interests in different ways, ranging from reasoning from legal procedures and the need for administrative processes to advocacy and litigation. These value conflicts lead to insurmountable legal and institutional mandate operationalisation differences in solving territorial issues concerning land and water rights. The sea fences are a manifestation of these insurmountable differences in legal and institutional mandates, yet these differences do not offer a clear path to resolving the issues at stake. In other words, the sea fences can emerge because the insurmountable differences create discretionary spaces for the actions and behaviour of the involved parties. They create opportunities for bribery, intransparency and non-controllable arrangements.

Despite the stakeholders’ insurmountable differences in sea fences, the boundary objects of joint epistemic values and dialogues on development opportunities in coastal land and water areas can bring divergent positions closer together. Still, there also needs to be boundary work to foster public interests and mutually beneficial outcomes. This will require, however, improved stakeholder dialogues to narrow down the discretionary spaces which come with legal and institutional ambiguity. In essence, stakeholders’ dialogues should also derive more transparent operational processes and co-existing value systems. We posit, therefore, that exploring the sea fences case has offered a justification for theoretical and practical claims that, in contrast to existing spatial frameworks, alternative institutional models governing territorial sea and land rights, restrictions and responsibilities need to be designed. This can be done by designing an operational legal process which detects where and how the values of affected stakeholders can be harmonised, instead of maintaining contradictory and overlapping systems which rely on a unilateral system of values of disconnected systems (of either land or sea).

Methodologically, this research primarily relied on secondary data sources, as direct contacts with the stakeholders and direct field observations were not possible due to the sensitivity of the case itself. This is indeed causes the potential risk of not being able to verify the data with its own or alternative data sources. Subsequent research should therefore test and validate the findings with additional primary data sources. Further research is also necessary to investigate other cases and locations where sea fences have emerged to verify if similar value conflicts have occurred and check if these have also led to informality and illegality. Additionally, one could expand the research to locations where fences have been created on land and assess if the role of coastal areas influences the outcomes in terms of informality and illegality. Finally, what was not part of the scope of this study, yet is still relevant, is to investigate how land and water rights can be unified into a single legal and institutional system such that ambiguities in land management and land use planning can be diminished.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, W.T.d.V.; methodology, W.T.d.V.; formal analysis, W.T.d.V. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.T.d.V. and S.P.; writing—review and editing, W.T.d.V. and S.P.; visualisation, S.P.; supervision, W.T.d.V.; funding acquisition, W.T.d.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SHGB | Building Right Certificate |

| SHM | Individual Right Certificate |

| PKKPR | Location permit regarding spatial planning |

| RTRW | Regional Spatial Planning |

| RDTR | Detailed Plan of Spatial Planning |

| RZWP3K | Zoning Plan for Coastal Areas and Small Islands |

| KKPRL | Marine Spatial Utilization Suitability |

| The Ministry of ATR/BPN | The Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Agency Republic of Indonesia |

| The Ministry of KKP | The Ministry of Marine and Fisheries Republic of Indonesia |

| The Ministry of KLHK | The Ministry of Environment and Forestry |

References

- Ballesteros, C.; Esteves, L.S. Integrated assessment of coastal exposure and social vulnerability to coastal hazards in East Africa. Estuaries Coasts 2021, 44, 2056–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, N.J.; Blythe, J.; White, C.S.; Campero, C. Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Mar. Policy 2021, 125, 104387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhtar, E.A.; Abdillah, A.; Widianingsih, I.; Adikancana, Q.M. Smart villages, rural development and community vulnerability in Indonesia: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2219118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, E. Defensible Space. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzuri, A.; Hassan, M.I.; Rahman, A.A. Incorporating Adjacent Free Space (AFS) for marine spatial unit in 3D marine cadastre data model based on LADM. Land Use Policy 2024, 139, 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labh, N. Reconsidering Sovereignty Amid the Climate Crisis. 2025, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 34. Available online: https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Labh-Climate%20Sovereignty.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Pinuji, S.; de Vries, W.T.; Rineksi, T.W.; Wahyuni, W. Is Obliterated Land Still Land? Tenure Security and Climate Change in Indonesia. Land 2023, 12, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirasola, C. What Makes an Island? Land Reclamation and the South China Sea Arbitration. Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. 2015. Available online: https://amti.csis.org/what-makes-an-island-land-reclamation-and-the-south-china-sea-arbitration/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Soegiono, P.D.; Arifin, L.S. Sustainable Aspects of Wall Constructions of Traditional Houses: Insights from the Bajau Tribe House, Indonesia. ISVS E-J. 2024, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.M.; Pide, A.S.; Lahae, K.; Intan, W.O. Challenges and Legal Certainty of Land Rights for the Bajo Tribe in the Context of SDG 15: Perspective of Building Use Rights and Ownership Rights. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2025, 5, e02963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvschal, M.; Gravesen, M.L. De-/fencing grasslands: Ongoing boundary making and unmaking in postcolonial Kenya. Land 2021, 10, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Channon, D.F.; Caldart, A.A. McKinsey 7S model. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. The McKinsey 7S model helps in strategy implementation: A theoretical foundation. Tec. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, T.; Waterman, R.H., Jr. McKinsey 7-S model. Leadersh. Excell. 2011, 28, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Perjalanan Kasus Pagar Laut Tangerang dari Awal Ditemukan Sampai SHGB Dicabut. Available online: https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2025/01/23/050000065/perjalanan-kasus-pagar-laut-tangerang-dari-awal-ditemukan-sampai-shgb?page=all (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Looking for the Brain Behind the Tangerang Sea Fence. Available online: https://voi.id/en/tulisan-seri/453555 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Polemik Pagar Laut di Tangerang, Nelayan Terancam! Available online: https://fpk.unair.ac.id/polemik-pagar-laut-di-tangerang-nelayan-terancam/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Nusron: Sertifikat Pagar Laut Tangerang Konversi Girik ke SHGB-SHM. Available online: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/4616934/nusron-sertifikat-pagar-laut-tangerang-konversi-girik-ke-shgb-shm (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Soal Polemik Pagar Laut, Pakar UGM Sebut Perairan Kepulauan Tidak Boleh Dimiliki Individu atau Perusahaan. Available online: https://ugm.ac.id/id/berita/soal-polemik-pagar-laut-pakar-ugm-sebut-perairan-kepulauan-tidak-boleh-dimiliki-individu-atau-perusahaan/ (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- KPA Anggap Sertifikat HGB di Lokasi Pagar Laut Bentuk Akrobatik Hukum. Available online: https://www.tempo.co/hukum/kpa-anggap-sertifikat-hgb-di-lokasi-pagar-laut-bentuk-akrobatik-hukum-1197320 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Aemanah, U. Konsep Pagar Laut. In Kajian Pagar Laut dalam Perspektif Hukum Agraria, 1st ed.; Siagian, A.A., Ed.; CV. Gita Lentera: Padang, Indonesia, 2025; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, F.; Chrisman, N. Boundary objects and the social construction of GIS technology. Environ. Plan. A 1998, 30, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapsed, J.; Salter, A. Postcards from the edge: Local communities, global programs and boundary objects. Organ. Stud. 2024, 25, 1515–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional ecology, translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanbo, Q.; Shilei, W.; Yaya, T.; Guanghui, J.; Tao, Z.; Liang, M. Territorial spatial planning for regional high-quality development–An analytical framework for the identification, mediation and transmission of potential land utilization conflicts in the Yellow River Delta. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C. Transcending land–sea dichotomies through strategic spatial planning. Reg. Stud. 2021, 55, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).