1. Introduction

The growing interest in the commons paradigm across multiple disciplines reflects a wider discomfort with the dominant systemic models that underpin contemporary societies. The challenges posed by the neoliberal model, which deepened socio-economic inequalities on a global scale, favoured the environmental collapse and democracy erosion, call for a radical reconsideration of this model by looking for alternative frameworks of co-existence and collective responsibility. In particular, the blind faith in a progressive neoliberal logic—which relies on favouring capital accumulation while dismantling mechanisms of social cohesion [

1]—has instead fostered societies marked by hyper-competitiveness, self-interest, and the erosion of spaces for care, creativity and solidarity [

2]. In this regard, the issue of collective urban assets and their management becomes central in the debate on the future of territories and their governance.

Within the framework of the civil economy, the commons model is increasingly asserting itself as an effective solution for the fair and equitable management of collective resources, both material (such as water, electricity, buildings) and intangible (such as knowledge, codes, ideas, knowledge or more generally cultural heritage), trying to overcome the traditional dichotomy between public and private. One of the earliest contributions to this debate is the article “The Tragedy of the Commons”, published in 1968 by Garrett Hardin, where the author addresses the problem of overpopulation and the management of limited resources through the metaphor of common grazing. Hardin highlights a rift between the commons and the communities, arguing that, in the absence of regulation, the uncontrolled use of commons resources will lead to their inevitable depletion. To avoid this “tragedy,” he proposes introducing external control and management mechanisms. His contribution, which matured in an era of growing ecological awareness, influenced the debate on sustainability and governance of communal resources, stimulating reflections that still question its premises and possible alternatives. Starting with the crucial issue of commons management, Elinor Ostrom, in her famous work “Governing the Commons” [

3], through an analysis conducted on different experiences of collective property management in various parts of the world, it showed how, under certain social and organisational conditions, shared administration can be very effective even in comparison with a model based on individual ownership. In particular, Ostrom, overcoming Hardin’s considerations related to privatisation or government intervention as possible solutions and the limits of the state-private property dichotomy, introduces a third solution that consists of the shared and participatory management of these assets, which aims to ensure their collective use for common benefit.

In the Italian context, “The Terrible Right” [

4] animated the legal debate between the 1960s and 1970s, leading to a reinterpretation of the Civil Code in light of the constitutional principle of the social function of property. The Civil Code of 1942, built on a patrimonial conception centred mainly on land ownership and the regime of ownership of property, detached itself from the Italian Constitution, which, on the other hand, has a personalistic imprint, placing the person at the centre and also recognizing property as having a functional value, which considers its use for general interests. In this context, aimed at overcoming the individualistic view of the Romanist matrix, the studies of Paolo Grossi [

5] played a key role. He pointed out the existence of models of collective resource management, using the concept of “another way of owning”, which is not fully aligned with the Civil Code, but indicates a “cultural pluralism that we must be inspired by and equipped with to avoid trampling on collective property because we have not understood it or have not even tried to understand it” [

6]. His contribution favoured the recognition of goods essential for a free and dignified existence. It played a key role in the overcoming of the 1927 law on civic uses [

7], also paving the way for the theoretical elaboration of common goods.

The two dimensions of urban and civic are closely interconnected, as civic use is one of the tools employed in managing urban commons—also known as “emerging commons” [

8,

9,

10]. These “rights of enjoyment” (hunting, fishing, grazing, or woodland rights) [

11], rooted primarily in the feudal legal tradition and still widespread in Italy in rural areas, are based on a collective structure for managing shared assets and are classified as real rights over property owned by others, held by a community [

12]. They grant that community—and each of its members—the ability to derive specific benefits from land owned by public or private entities, serving as a partial source of sustenance [

13].

Currently, collective properties in Italy are regulated by Law 168/2017 [

14] which, in contrast to the 1927 legislation on civic uses, does not seek to abolish collective rights but rather to recognise and protect them. However, this law remains closely tied to rural and agro-silvo-pastoral contexts. It does not address the new forms of civic use that have emerged within urban movements advocating for the governance of so-called emerging commons, referred to as

urban civic uses. Yet even in these urban contexts, the underlying approach reflects what Paolo Grossi described as “another way of owning” [

5]: a form of open and collective management of a resource—most often public—by a community that, while not formally structured as a legal entity, is nonetheless capable of stewarding and enhancing the asset collectively.

As of today, the Italian legal system still lacks a national legislative definition of “commons.” The first definition of “common good” developed in Italy was formulated by the Rodotà Commission [

15], which described such goods as those that “serve functions essential to the exercise of fundamental rights and to the free development of the person.” This concept, which has been adopted in various municipal statutes and regulations across Italy, places the relationship between goods and individuals—mediated through fundamental rights—at its core. This understanding has also been enabled by a constitutional premise that links public ownership to public use, and obliges private property to fulfil a “social function” [

16], thereby reaffirming the legal significance of a rights-based approach to law.

This paper aims to contribute to the growing reflection on the collective management of community assets, a theme closely intertwined with the broader debate on commons, and in particular urban commons, as subjects of participatory and bottom-up governance models. The main objective is to explore how such models—by defining goods not by ownership but by their social function and mode of governance—challenge the dominant paradigm of individual ownership and advance a collective, community-based approach. This perspective is partially reflected in Italy’s Law 168/2017, which recognises collective domains and civic uses, where the rights-holder is not the individual, but a community, conceived as an exponential collective entity. However, despite the emergence of these models, there remains a significant research and regulatory gap in Italy, particularly concerning the explicit recognition of the notion of urban commons. The latter has sparked wide-ranging academic and public debate, from whether such spaces can be interpreted within the Civil Code’s notion of “goods” to broader questions of ownership, access, and collective governance. Nevertheless, the practical implementation of urban commons governance remains uneven and poorly codified.

Against this backdrop, this paper seeks to critically assess how, in the absence of comprehensive regulation, local practices and negotiated governance models are filling the legal and institutional void, shaping a new understanding of urban commons as a space of civic innovation and legal experimentation. In this context, civil society has played a pioneering role, particularly at the local level, where an unprecedented mobilisation has occurred to reclaim underused spaces and reassign them new social roles. This valorisation process has involved not only third-sector actors and established networks, but also informal, spontaneously formed communities. Local governments, too, have shown variable degrees of support, often developing heterogeneous and experimental approaches to these initiatives. Additionally, philanthropic foundations have contributed, sometimes directly, but more often by funding grassroots or community-led projects.

In this article, the inquiry begins with a critical review of internationally established definitions of the commons, drawing from both scientific literature and grey sources. This first review aims to identify shared conceptual ground and develop an operative taxonomy useful for comparative and analytical purposes. Building on this general framework, the research then focuses on the Italian context, where the absence of a national law regulating the commons foregrounds the importance of local practices and conditions for their recognition and governance. Within this twofold structure, the following research questions are addressed:

What are the distinctive features of urban commons, and what value-based dimensions influence their emergence, collective use, and sustainability in different contexts?

What criteria and operational conditions make it possible to identify effective governance models for urban commons in practice, particularly where—in absence of specific regulatory frameworks—local variables become crucial in enabling the transition of places from private or economic goods to collectively managed resources?

To answer these questions, this paper analyses some relevant cases arising in the territory of Southern Italy, exploring the role of situated innovation in the recognition and management of the urban commons, even when not formally recognised as such.

The paper is structured according to the following framework:

Section 2 presents the aforementioned literature review;

Section 3 exhibits the methodological framework, describing the main phases and tools for the elaboration of the COMmons Places ASSessment (COMPASS) approach;

Section 4 illustrates the five Case Study selection and deepens their analysis;

Section 5 discusses the results regarding the implementation of COMPASS in the selected case studies, and analyses the potential and critical issues of this approach;

Section 6 is dedicated to the conclusion and future perspectives of research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions and Taxonomies of Urban Commons

The term “common good” already reveals in its dual noun nature a semantic combination of the noun “good” and the adjective “common.” Hess and Ostrom defined a common good as “a resource shared by a group of people” [

17], in the sense that a good or resource to be common must possess a use value for a plurality of individuals. However, this definition does not seem sufficient, since in this sense any urban space or object takes on—or could take on—a use value for a particular group. An economic aspect emerges from the International Association of the Study of the Commons (IASC) definition of “common good” that characterises “resources” as common good when “people do not have to pay to exercise their rights of use and access within a set of institutions or rules that protect the goods from excessive use by people who do not [respect their] fragility or limitations” [

18]. Even this definition has some critical issues in excluding categories of open-access intangible goods, such as knowledge or information, scientific databases, the arts, and open-source software, which do not possess physical limits and therefore require management for their sustainability. Therefore, it is necessary to retrace some historical taxonomies to redefine the commons, starting when economist Paul Samuelson [

19] introduced the distinction between private and collective goods to represent the social choice between capitalism and socialism, envisioning an optimal balance between the two systems. He emphasised the concept of rivalry—that is, the extent to which the consumption of a good by one individual affects the possibility of consumption by other individuals—which, in the category of goods with free access without material constraint (intangible goods), does not exist, since their use does not limit the use by others.

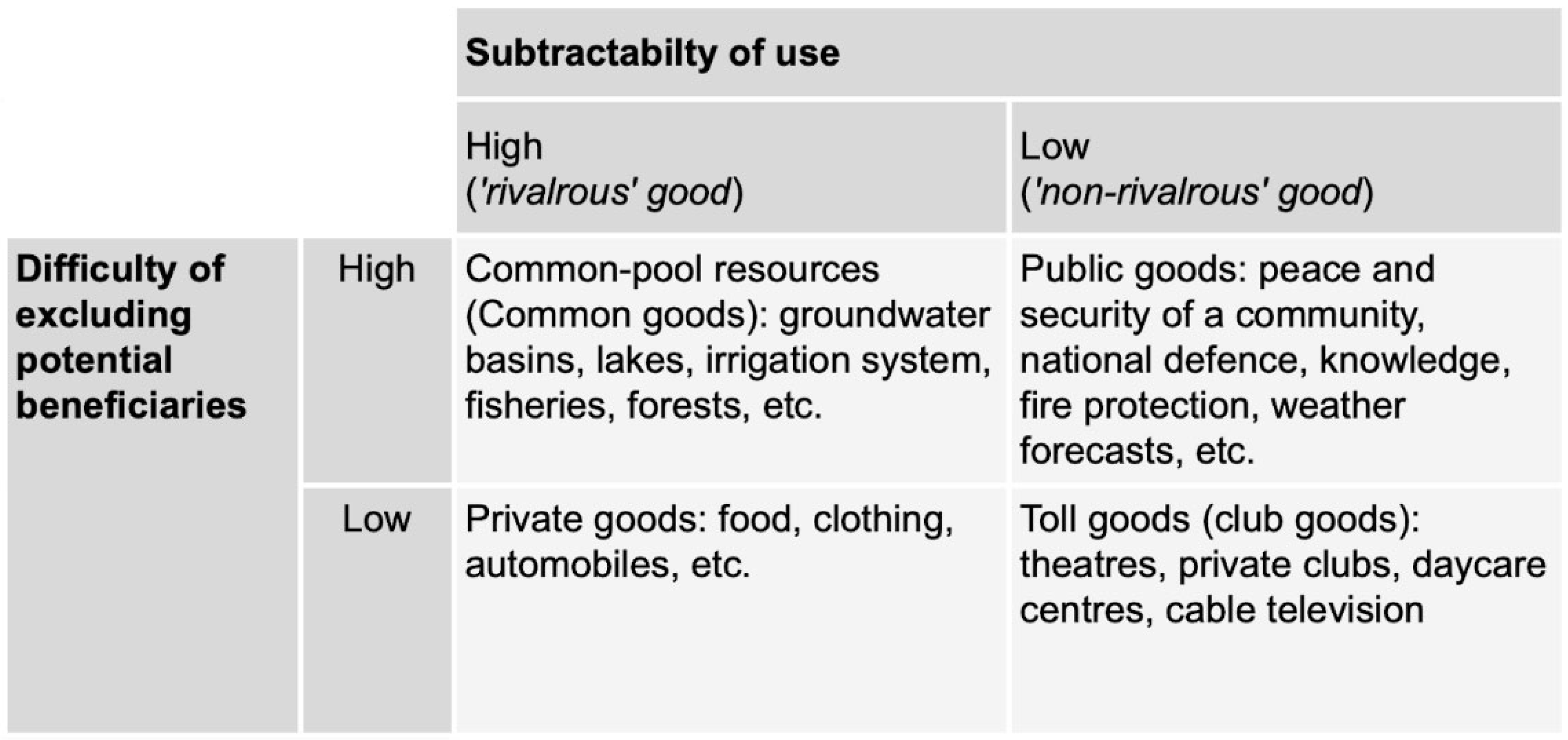

In economic theory, the concept of rivalry of a good does not concern the capitalist social relations through which it is produced, but rather its consumption and use by other consumers simultaneously. On the other hand, a good is considered nonrivalrous if the cost of providing it to another individual is zero (marginal cost equal to zero). While Samuelson focused on rivalry, Prest & Musgrave [

20] wondered whether a good could be made available only to those who meet certain conditions (excludability), such as paying a price. This distinction led to the formulation of the 2 × 2 classification matrix of economic goods, still used today. According to Elinor Ostrom’s [

21] reinterpretation, it assumes a nonbinary division of these categories of goods and replaces the concept of good rivalry with that of use excludability (

Figure 1).

In this matrix, goods are divided by the degree of difficulty of exclusion of potential beneficiaries (high or low) and by the degree of subtractability of use (high or low). In the low subtractability—high beneficiary exclusion difficulty quadrant, we have the “nonrivalrous” goods, also known as public goods, which can thus be enjoyed simultaneously by an unlimited number of consumers. In the opposite position, we find high subtractability—low exclusion difficulty where private goods are placed. The lower left cell, which indicates low substitutability and low exclusion difficulty, houses club goods [

22] or pay goods, resources that lie somewhere between public and private goods and reveal different willingness to pay depending on the availability of the user who uses that type of good. Finally, there remain the commons, referred to here as subtractable goods with a low degree of excludability, such as natural resources.

As pointed out by De Angelis [

23], if only an economic approach is adopted, such characteristics are relegated to an intrinsic property of the good (endogenous), while the meaning that a community of people attributes to it is not taken into account at all. There are, in fact, exogenous features, identified by De Angelis (

Table 1) as the system of social relations of the commons, which attributes to the commons the claim by a plurality, the commoners, that claims ownership of that good as a common good (commonwealth/common goods).

The close correlation between the three dimensions—spatial, social, and governmental—shapes the complex entity of urban commons [

24], or emerging goods, as social infrastructures that are both deeply dependent on the specific territorial context and, at the same time, generative of alternative social dynamics based on shared collective values.

From Ostrom’s study of the commons, several fundamental principles emerge, in which these three dimensions intersect to define the boundaries of a common good, ensuring that its use does not instead lead to a tragedy. In 2017, Derek Wall [

25] revisited these principles, summarising them into the following eight key points:

Commons must have clearly defined boundaries. Specifically, who has the right to access what? Without a designated community of beneficiaries, it becomes a free-for-all, and that is not how commons function.

Rules should be adapted to local circumstances. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to managing common resources. Local populations and ecological needs should shape rules.

Participatory decision-making is vital. Various ways exist to ensure this, but people are more likely to follow the rules if they have a role in creating them.

Commons must be monitored. Once rules are established, communities need mechanisms to ensure they are upheld. Commons do not function purely on goodwill but require accountability.

Sanctions for those who abuse the commons should be graduated. These should include warning systems and fines, as well as informal reputational consequences within the community, rather than immediate exclusion from the resource.

Conflict resolution should be easily accessible. When issues arise, resolving them should be informal, cost-effective, and straightforward. This ensures that anyone can seek mediation and no one is excluded. Problems should be addressed rather than ignored because of legal costs.

Commons need the right to self-organise. Rules are meaningless if a higher local authority does not recognise them as legitimate.

Commons function best when nested within more extensive networks. Some resources can be managed locally, but others may require broader regional or supra-local cooperation.

However, the principles outlined above cannot be fully applied to urban commons in the same way they have been used to understand the management and governance of natural resources [

26], making it necessary to interpret and adapt them to the realities under study in this contribution. Cities, indeed, are highly regulated spaces where natural resources, urban infrastructure, and social structures intersect and intertwine. They are not merely containers of pre-existing commons but environments in which these commons often result from social and political processes, with a spatial consistency very different from that of natural resources.

Urban commons can emerge through co-production practices and collaborative governance that not only manage existing resources but also actively contribute to the creation of new shared resources. This distinctive characteristic implies that the management of urban commons cannot disregard legal experimentation and the need to adapt public and private regulation to foster participatory governance forms.

2.2. Space Commoning as New Forms of Social Organisation

The commons’ spatial, physical, and territorial dimensions emerge strongly in terms of not only consumption and capacity of the commodity but also its capacity to produce social relations through space. Several authors have addressed this issue in the literature [

27,

28,

29], bringing out even in the study of the commons a conception of space that interacts with such relations and ensures concrete contexts to support their representations [

30] “Spaces, concrete lived spaces, are works (the result of labour), but also the means to shape possible future worlds. If we connect this perspective with Lefebvre’s idea that the city is the collective “oeuvre” of its inhabitants, then the potentialization of space is shaped through human interactions that develop shared worlds. To potentialise those shared worlds, which means to challenge their meaning and their power to present the distribution of the sensible as an indisputable order of life, people have to activate the potentials of commoning. And this essentially amounts to the liberation of commoning from capitalist command” [

30].

As observed by Stavrides [

30], space acquires a pre-figurative capacity since it succeeds in its multiple arrangements not only to illustrate or represent the social relations that take—or might take—place in it but also to prefigure as a medium of different social conditions, a testing ground for possible futures through prefigurative politics. In other words, spaces pre-figure possible scenarios, developing imaginaries through practices of emancipation and reappropriation of the power of “commoning”.

According to Otte and Volont, there are two main approaches to the spatial dimension of the commons [

30]. The endogenous approach focuses on the relationship between a group of people and shared space. It was Elinor Ostrom [

3] who, with her seminal study “Governing the Commons” and its design principles for successful management of the commons (pp. 90–102), brought to academic attention the issue of having to make rules in response to the free-riding phenomenon of the commons that Hardin [

31] was concerned about in the “Tragedy of the Commons”. The second, on the other hand, is an exogenous approach, pursued by post-Marxist scholars, including Dardot and Laval [

32] and De Angelis [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], which considers common space (commons) not only as a shared place but as the result of a struggle or claim against the dominant logic of privatisation and control of space by the state or market.

According to this view, space commoning [

30] represents an opportunity to experiment with new forms of social organisation, in which space, understood as threshold space, is configured as a transitional dimension, open to changing uses and meanings. Stavrides argues that these spaces should not take definitive forms, but rather should remain creations-in-the-making as part of a common world-in-the-making. In other words, while the endogenous approach (such as Ostrom’s) focuses on a community’s internal management of shared resources, the exogenous approach interprets the creation of common spaces not only as places of co-belonging and co-ownership but as places of political action and resistance, where dominant forms of collective living are questioned and transformed.

2.3. Commons in the Italian Law

In the case of Italian law, defining what constitutes a “common good” is not easy, especially due to the absence of a comprehensive legal framework that formally recognises them within the national legal system. However, numerous regional and local regulations have been developed over the years, inspired by Italian jurisprudence (Cass. S.U., nn. 3665 and 3811 of 2011; Corte Cost. n. 119 of 2015; Cons. St. n. 769 del 2015; TAR Lazio nn. 4157, 4158, 4184 of 2016; TAR Veneto, n. 273 of 2018; Cons. Stato, n. 5372 of 2018) and the principles outlined by the Rodotà Commission [

4], which have helped define some characteristics of common goods at the national level. Through a constitutional reinterpretation of property rights, these reflections on common goods have also led to the drafting of a framework law proposal aimed at modifying the civil code’s approach to public goods, which is considered inadequate.

In June 2007—due to a progressive process of public asset disposal through privatisation, which had begun in the 1990s for financial reasons—the Minister of Justice at the time appointed a commission, chaired by Stefano Rodotà, to draft a framework law proposal for the modification of civil code regulations on public goods (Articles 822–830 of the Civil Code). The proposal presented by the Commission provided for classifying goods into three categories—common goods, public goods, and private goods—further subdivided internally, to replace the existing legal regime of public domain and state-owned assets. Although this proposal was never translated into law, it played a fundamental role in laying the groundwork for the doctrinal debate, which peaked between 2011 and 2014. This period saw the success of the referendum campaign for water as a common good and the emergence of a series of occupations of abandoned assets, beginning with the Teatro Valle experience in Rome. The framework law proposal thus defined the concept of common goods, which has since been repeatedly referenced in local regulations, jurisprudence, and legal scholarship.

Beyond the theoretical debate, another area that seems necessary to explore further concerns the management models of common goods. In the Italian experience, the practical applications of this phenomenon particularly involve urban commons, which can be empirically defined as goods located in urban contexts suitable, at least potentially, for cultural, recreational, artistic, and sports activities that impact the psychological and physical well-being of individuals and lend themselves to collective use. Among these, it is primarily public goods that are involved, but since cities inherently represent a privileged context for managerial innovation and the interaction between public and private entities, this does not exclude other possibilities regarding the nature of the goods involved. Regardless of ownership, common goods tend to catalyse collective interests and, at times, even private ones, acquiring significance that can justify their recognition as goods of general interest, such as ecclesiastical goods or those confiscated from organised crime. Analysing the action in the management of urban commons, three approaches emerge: that of municipalities that adopt a regulation on common goods, that of municipalities without a regulation, and the third, the model of civic uses, as adopted in Italy, in the city of Naples. From these assumptions, two collective management frameworks for this particular type of goods can be derived: (1) the co-management model between public administration and private entities, outlined in particular by the regulations on urban commons through collaboration agreements; and (2) the model of collective self-governance, where collective management is based on declarations of civic and collective urban use, which, while referring to private law institutions, do not adopt their normative frameworks. These parameters have also identified the case studies in which the developed evaluation framework can be applied and tested.

3. Methodological Framework

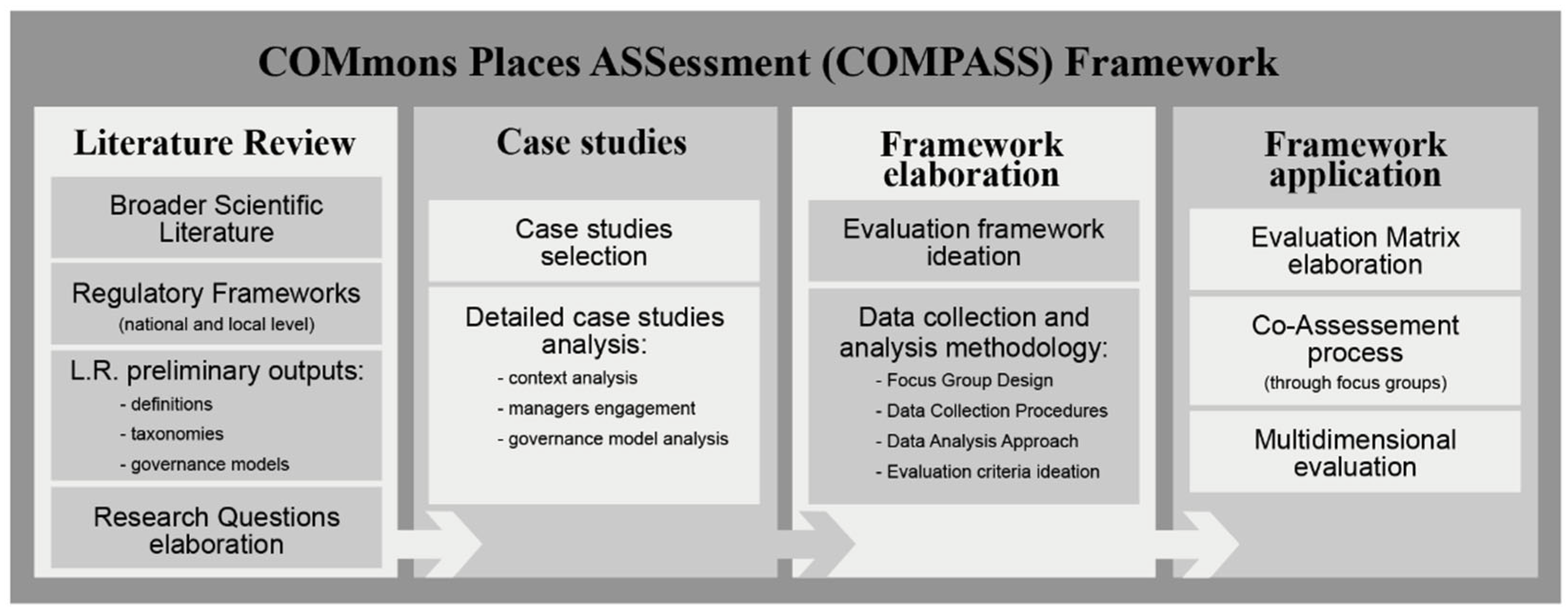

The present research is based on an empirical methodological approach (

Figure 2) that aims to elaborate an evaluative framework for comparing different practices of governance to understand their specific characteristics, the levels of “commoning” process that characterise the selected places, and what contextual conditions fuel convergences or divergences in the emerging results.

Economic goods refer to those exchangeable products or services that hold economic value based on the price determined by consumers’ willingness to pay within a market. The difference between economic goods and common goods lies in the fact that the former, within a neoclassical economic framework, acquire market values that vary according to each consumer’s willingness to pay. In contrast, the latter, as we will see later in the literature, generates a plurality of collective values recognised not by a single individual but by a community [

35,

36,

37].

The interpretation of the transition of urban spaces towards commoning in the common goods debate starts from an extensive literature review, which was conducted to outline the state of the art and identify the main theoretical and operational issues related to the study topic. The literature review allowed the construction of an evaluation framework, in which a set of criteria was developed to assess the transition of the analysed spaces from economic to common goods.

3.1. Data Collection

The proposed COMmoning Places ASSessment Framework (COMPASS) was then applied to a selection of case studies in the Campania region, identified for their relevance to the issues that emerged in the literature review phase, for the scientific interest of the topic in the local context, and the deep knowledge of the researchers involved in the present contribution of these practices supported scientifically in their evolution.

Specifically, five case studies located in the Campania region were identified: iMorticelli in Salerno, Lido Pola Bene Comune and the Ciro Colonna Multipurpose Center in Naples, Forum Lab in Anacapri and the Multipurpose center Schifa Lab in Atena Lucana to highlight the diversity of legal, social and spatial configurations that characterise the management and sustainability of urban commons in different territorial contexts. The case studies were compared to identify convergences or divergences in management approaches, according to the commoning process, regarding their specific objectives, contexts, and activated regenerative processes. Finally, the discussion of the results enables systematisation of what has been learned to guide the next steps of the research.

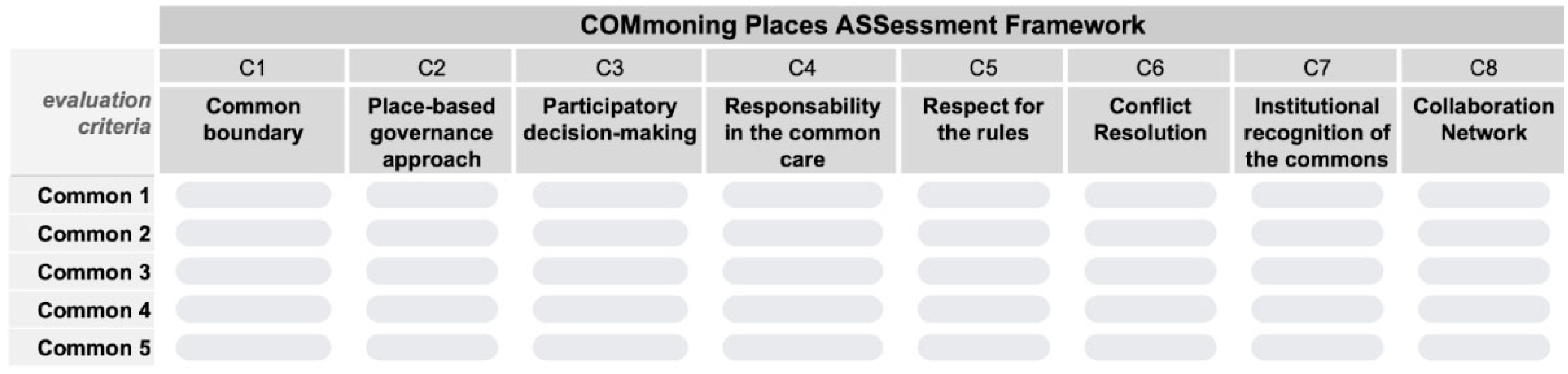

Based on the findings from the literature review, a qualitative evaluation framework was constructed to assess the degree of transition of spaces from economic goods to common goods. The objective of the framework is to offer a scientific tool to investigate the governance of assets and provide fields of reflection within and outside the organization, including in comparison with other assets and contexts, different in terms of spatial and normative contexts. This evaluation framework adopts appropriate criteria that allow for a detailed exploration of the governance characteristics applied in these places and the degree to which these places align with the commons parameters defined in the literature. More specifically, starting from the principles of Elinor Ostrom as rewritten by Derek Wall, eight specific criteria (

Figure 3) were identified through which the different case studies considered can be compared.

3.2. Data Analysis

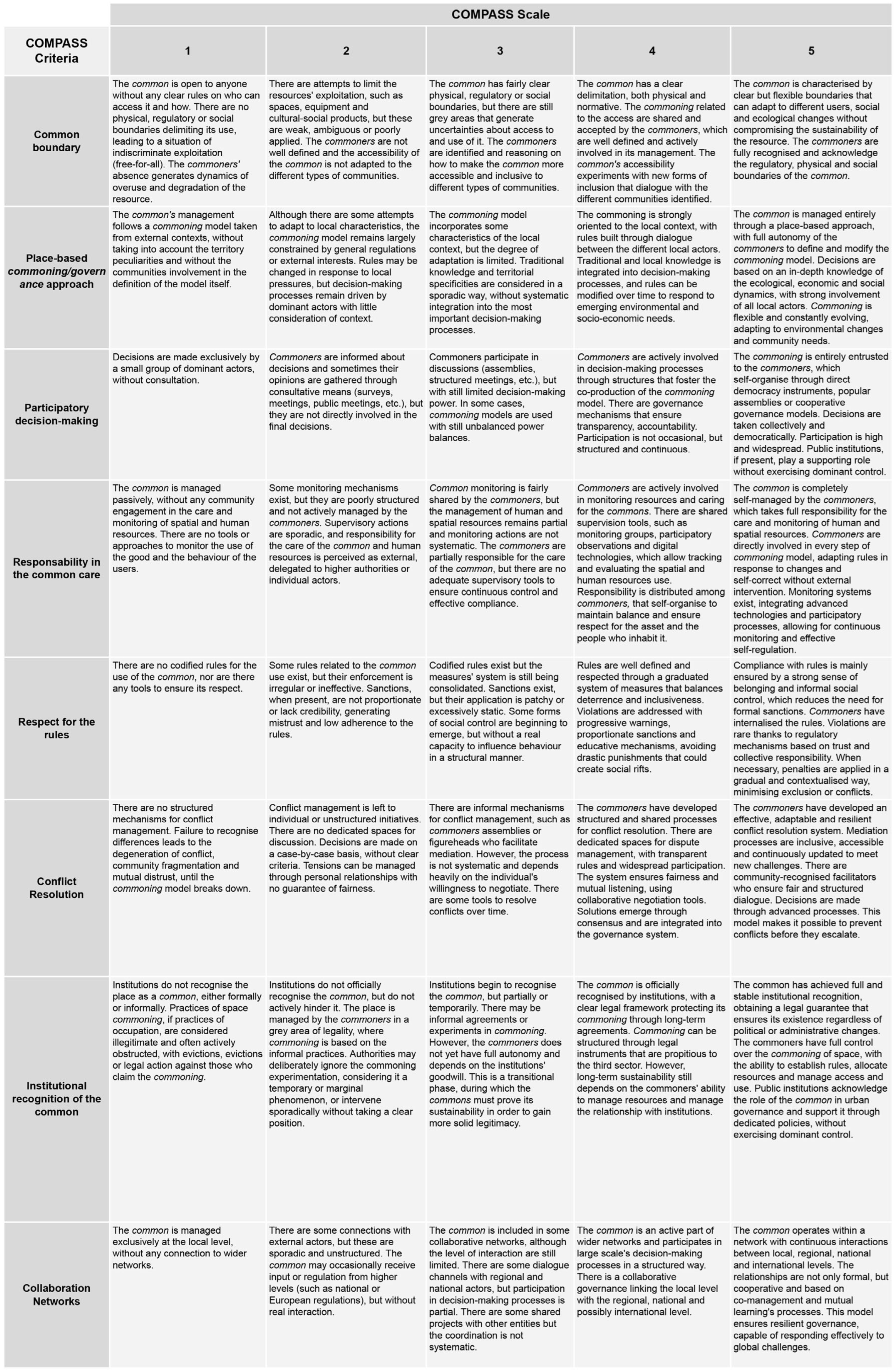

In this regard, the evaluation criteria system is outlined below.

The first criterion (C1) is defined as “Common Boundary”. It aims to assess the level of definition of the socio-spatial boundaries that regulate the permeability of the good to different communities.

The second criterion (C2) is a “Place-based governance approach”. It measures the management model’s ability to adapt to the territory’s specificities, characteristics, and economic and social dynamics.

The third criterion (C3) aims to analyse the level of participation of the communities inhabiting the territories in decision-making processes related to the direction of the good and is, in this sense, defined as “Participatory decision-making.” This criterion includes, for example, the level of community participation in decision-making processes (e.g., drafting rules and governance models).

Criterion C4, “Responsibility in the common care,” measures the level of community involvement in the collaborative care of the space through monitoring tools and shared responsibility approaches.

Next, the fifth criterion, C5, “Respect for the rules,” addresses the need to measure the capacity to encourage and manage rule compliance by providing regulatory approaches and tools.

Another aspect the framework considers is the ability to accommodate, mediate, and resolve conflicts informally and collectively, through criterion C6, “Conflict resolution”.

Regarding the degree of recognition by local authorities, C7, “Instrumental recognition of the commons”, aims to identify the level of recognition and legitimisation of the good by institutions.

Finally, concerning the relationships that can be built between the good and other resources in a network, C8, “Collaboration networks,” focuses on the intensity of relationships built within broader networks (regional, national, European, etc.) for the sharing of practices, themes, and approaches.

Each criterion is associated with a judgment using a 5-point Likert scale, where each increasing numerical value corresponds to a progressive degree of maturity of the good in moving towards its actual common dimension. Each value between 1 and 5 is associated with an appropriate semantic judgment, developed from the literature review, to assign a specific qualitative meaning to each numerical value, interpreting it descriptively to facilitate and clarify the evaluation (

Figure 4).

The detailed description of each value on the Likert scale represents more rigorously the different interpretations that a governance of an urban common good can take, intentionally or unintentionally, and the path of transition to a connotation that can be properly defined as common.

In cases where the framework is used simultaneously across multiple case studies being compared, as in this research, it is methodologically advisable to proceed in two phases: an initial stage of assigning individual evaluations, followed by a focus group involving representatives from the different case studies. The focus group, that is recognised as a remarkable tool to analyse the collective construction of meaning through stakeholder interaction [

38,

39,

40,

41], serves several purposes:

To understand the reasons behind individual evaluations and, where necessary, to revise the judgments expressed;

To identify and explore the factors that lead to convergence or divergence across the various criteria in the five case studies;

To share any critical issues related to the COMPASS tool to support and guide future research developments.

The assessment process of the different case studies under comparison can be summarised in a radar chart [

42] to visually compare the various governance structures of the analysed cases and their level of transition from economic goods to urban commons.

The radar chart [

42], characterised by its polygonal structure and equidistant radial axes, enables the simultaneous comparison of data across multiple dimensions. The data are normalised on a common scale, in this case from 1 to 5, and each urban commons practice is represented by a line connecting the points on the various axes, corresponding to the criteria for which the scores were assigned.

The resulting polygonal shapes describe the profile of each practice and reveal specific insights into the governance of urban spaces: broader and more regular shapes indicate more balanced governance. At the same time, significant distortions suggest imbalances or specialisation in certain aspects.

This final visual diagram not only reveals key information about individual spaces, highlighting points of similarity and divergence but also offers broader reflections on the governance of common goods and the situated nature of collective resource management.

The COMPASS framework is, in fact, still under development, and for this reason, it aims to draw on the various reflections emerging from its different contexts of application. The goal is to develop the framework in terms of its structure, terminology, and the set of criteria being analysed.

4. Case Study Analysis

To test and validate the framework described above, five active practices defining five processes of transition of economic goods into commons were identified. These case studies, which have emerged from a variety of processes of urban regeneration and social innovation in Campania region, in Italy, were selected for two reasons:

The ability of these practices to describe the articulated and complex compendium that constitutes the variety of commons;

The knowledge of the practices by the research team that has followed them over time.

Concerning the first point, it could be said that very different evolutionary processes characterise these practices. In particular, they include the following:

- −

iMorticelli, a process of culture-based adaptive reuse of a historical-artistic heritage;

- −

Forum Lab, a process of youth-led reactivation of a cultural asset;

- −

Schifa Lab, a process of direct declaration as a common made up by the local municipality;

- −

Ciro Colonna Center—CUBO, a process of association-based regeneration of a public building;

- −

Lido Pola Bene Comune, a process of informal re-appropriation and consequent recognition as a common good.

This description outlines the co-presence of bottom-up (iMorticelli, Lido Pola Bene Comune, Ciro Colonna Center), hybrid/horizontal (Forum Lab) and top-down (Schifa Lab) processes. This is closely related to the coexistence of endogenous and exogenous approaches [

33]. Examples include the case of “iMorticelli”, where an endogenous approach can be recognised, and the case of “Lido Pola Bene Comune”, where the exogenous approach constitutes a pivotal element of the asset recognition process.

In addition, the selected assets are located in four different territorial contexts and include: the metropolitan City of Naples (an industrial district and a residential district), the medium city of Salerno and two case studies fall within the territories identified as Inner Areas within the SNAI 2021–2027: Anacapri and Atena Lucana village.

From a typological and dimensional point of view, the assets taken into consideration include the following: two religious buildings (500 sq.m. and 50 sq.m.), a historic private dwelling (400 sq.m.), a former school (1000 sq.m. approx.), and a former bathing establishment (800 sq.m.).

The processes of institutional recognition of the commons also reached different milestones in those contexts. In some cases, this recognition has taken place explicitly (Lido Pola Bene Comune, Schifa Lab), in others it is subject to more nuanced, partial or temporary definitions (Forum Lab, iMorticelli), and in others it has not yet taken place. Finally, these practices are characterised by heterogeneous management/governance models, coordinated by managing bodies of different types (association, council, local authority, informal community, etc.) and varying degrees of responsibility for the asset. Among the common elements, however, emerges the ownership regime.

The municipality currently owns five assets, either through purchase or acquisition.

Table 2 constitutes a synthetic abacus of the selected cases.

The case studies briefly describe how they evolved into a commoning space, their governance structure and their space allocation.

The Ciro Colonna Centre, or CUBO, is an urban hub of social innovation, aggregation and redemption for young people in the eastern area of Naples. The centre was inaugurated in 2019 in a former school and was established to address the high NEET rate, which reaches 31% in Ponticelli [

43]. The centre has become a symbol of resilience against organised crime. Recovered from abandonment through the efforts of organisations such as “Maestri di Strada”, the centre has become a focal place, addressing educational disparities through creative workshops and research projects, fostering active citizenship, and repurposing spaces innovatively. The municipality owns the building, but it has been rented by the association “Maestri di Strada” and others, transforming it into a pivot of local inclusion. The facility boasts a variety of amenities, including a theatre, a recording studio, sports areas, a climbing wall, a social kitchen, a cafeteria, and dedicated spaces for family and individual therapy. Common rules have been established to foster coexistence between the different stakeholders living in the centre, enabling it to provide essential services to the residents of the neighbourhood and the community at large. International researchers have previously examined the CUBO as a model for urban regeneration and community well-being. Although not officially designated as a

common good, the centre meets the criteria for such a designation. The temporary association, the current manager, is transitioning towards the Participation Foundation model, ensuring the permanent protection of the space so that it can continue to serve as a sanctuary for those in need.

In Anacapri, the St. Michael Cloister—a public, underused cultural asset—houses the Forum Lab: a space whose innovative use is fostering a

youth-led regeneration process of the entire building, made by a young community aggregated around the Anacapri Youth Forum (AYF). This process, which began informally with the assignment of a deposit in 2013, was accelerated by the launch of the ‘Forum Lab’ project (D. No. 147/2022), which saw the space transformed into a free coworking space, co-managed under the AYF coordination. This enabled the experiment of co-management of the space through a collaborative digital calendar and a shared team, aiming at a process of re-appropriation made by the young community, which currently takes care of the lab. The process is supported by the local authority, through economic resources, and also fostered by the institutional framework in which Youth Forums (YFs) fit, at the regional [

44] and the European level [

45], making it possible to imagine how YFs can promote an underused public spaces regeneration through their reuse and how these places—if networked—can be an infrastructure of social and urban regeneration. Anacapri’s local authority recently confirmed its support with the D. No. 39/2025, renewing the free concession to the AYF until 2027, through a ‘disciplinary of use’. In 2023, a co-assessment process—developed in an action-research process—saw the engagement of stakeholders to define new scenarios for the whole cloister [

46]. Finally, other parts of the property are undergoing a process of re-appropriation by the youth community and through funding opportunities (D. No. 70/2025) that suggest an active transition from an underused public space to a recognised

common.

The former 16th-century baptistery of the “iMorticelli Cultural Center and Community Hub” is located at the northern gate of Salerno’s historic centre. Since 1980, the good has been slowly decommissioned, turning over to municipal ownership. A culturally-based urban regeneration process initiated by the Blam collective in 2018, through a framework agreement with the Department of Architecture of the University of Naples Federico II and the city of Salerno, activated an adaptive reuse of the former church through a creative living lab approach [

47]. As a result, new uses for the site have been established, involving resident and temporary communities in site-specific co-production practices. Today, it has been transformed into a Community Point, a hybrid space where a neighbourhood concierge, cultural hub and social cafeteria can be found. This space is open during the week and results from a collaboration between cultural operators and local citizens, offering a diverse cultural programme. The Blam Social Promotion Association oversees the property, which manages it through a partially biennial free loan agreement with the Salerno Municipality (which provides free rent, but payment of utilities). This arrangement is defined in the framework of a call for proposals funded by the Ministry of Culture and won by Blam. The association can self-finance the management and socio-cultural activities of the space through participation in calls for tenders and the social cafeteria.

In the context of Bagnoli, a neighbourhood of the city of Naples, the community of “Lido Pola Bene Comune” is constituted by numerous civil actors. Historically, it operated as a bathing establishment from the 1960s to the 1990s, and it was subsequently abandoned. Since 2013, it has been occupied by the informal collective Bancarotta 2.0 to prevent its privatisation. The local authority formally declared the site as common with the D.n°446/2016 and subsequent regulatory acts to recognise its significance. This designation enables the asset safeguarding through both civic and collective usage, entrusting its administration to the community through a participatory self-government model. This model is characterised by a “Declaration of use” and the “Prendi Spazio” Management Assembly. The Lido Pola Bene Comune is a prominent proponent of cultural activities, leveraging various economic and non-economic resources. These resources have been found by establishing collaborative networks, empowering the community to access national and European funding opportunities. This assertion is evidenced by the Po.L.A.R.S. project of 2021, which sought to establish an experimental research centre addressing marine and urban environmental concerns [

48], and by the LP2 project, which led to the establishment of a permanent Urban Living Lab dedicated to research activities that are now supported by the PS-U-GO project, which was developed within the framework of an Erasmus+ collaboration with the Department of Architecture of University of Naples Federico II and CNR IRISS.

The building of the multipurpose center Schifa Lab is located in the historic centre of Atena Lucana, in the province of Salerno, in the highest part of the old town centre. Over the years, after being included in the real estate of the Municipality of Atena Lucana, it has become the main headquarters of the local associations, which, in 2021, contributed to the drafting of the Archivio Atena project [

49], which was the winner of the notice—published by the Ministry of Culture—concerning investment 2.1: “Attractiveness of historic villages”, under Component 3—Culture 4.0 (M1C3) and Measure 2 “Regeneration of small cultural sites, cultural, religious and rural heritage”, included in Mission 1 (PNRR)—

Digitisation, innovation, competitiveness and culture. Declared “common good” by Resolution No. 9/2022, the building will become a multifunctional centre [

50]. The Archivio Atena project envisaged its functionalization by creating a digitalisation centre, a multifunctional hall, coworking spaces, an audio recording studio, a press centre and an exhibition hall currently under construction. Some work has already been completed to remove architectural barriers to make this space more accessible. The Schifa Lab will always be home to local associations and the nascent community cooperative.

As described above, the five cases represent five very varied examples of transition from an economic good to a common good and, because of this, their selection is particularly significant in the testing and validation of an evaluation framework capable of taking into account the multiple specificities related to these practices and and their different capacity to become an urban common in specific contexts. Considering this, the application of the COMPASS framework was implemented by organising and carrying out five focus groups, one for each of the selected assets, to activate the dialogue between the research team and the managers and activists to co-assess the degree of progress towards urban commoning and enable a shared reflection on the evolution of the specific collaborative decision-making process and the level of awareness of commoners, promoters and participants.

The managers of the selected case studies participated in assessing their own “level of governance” by applying the COMPASS methodological framework in two stages. The meetings were held virtually during March 2025. During the first phase, each manager was required to conduct an individual evaluation and could consult their team if necessary. The second phase consisted of a two-hour focus group, during which the case study managers shared the results of their assessments. Analysing one criterion at a time, each manager presented their specific interpretation and explained the rationale behind the rating they had assigned, often supporting their account with examples. When there were no significant discrepancies in the interpretation of a criterion across the different cases, the group proceeded to the next. Otherwise, an in-depth discussion was held to better understand the various motivations or interpretations of the framework—whether these arose from the participants’ differing backgrounds and experiences, or from ambiguous language within the framework itself.

5. Results and Discussions

The following section outlines the results of the research presented in this paper, combining findings and discussions related to the case studies evaluation and their broader implications. The reflections that emerged during the co-assessment process through the focus groups [

38,

39,

40,

41] led to terminological refinements within the framework, particularly in cases where the language used for certain criteria was perceived as ambiguous or insufficiently aligned with the practices of urban commons. These lexical adjustments were aimed at enhancing clarity and reducing interpretive ambiguity, ensuring that the criteria more accurately reflected the stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences. In this sense, the criteria themselves gained meaning through the dialogical interaction with stakeholders, who contributed to grounding abstract concepts in concrete local practices.

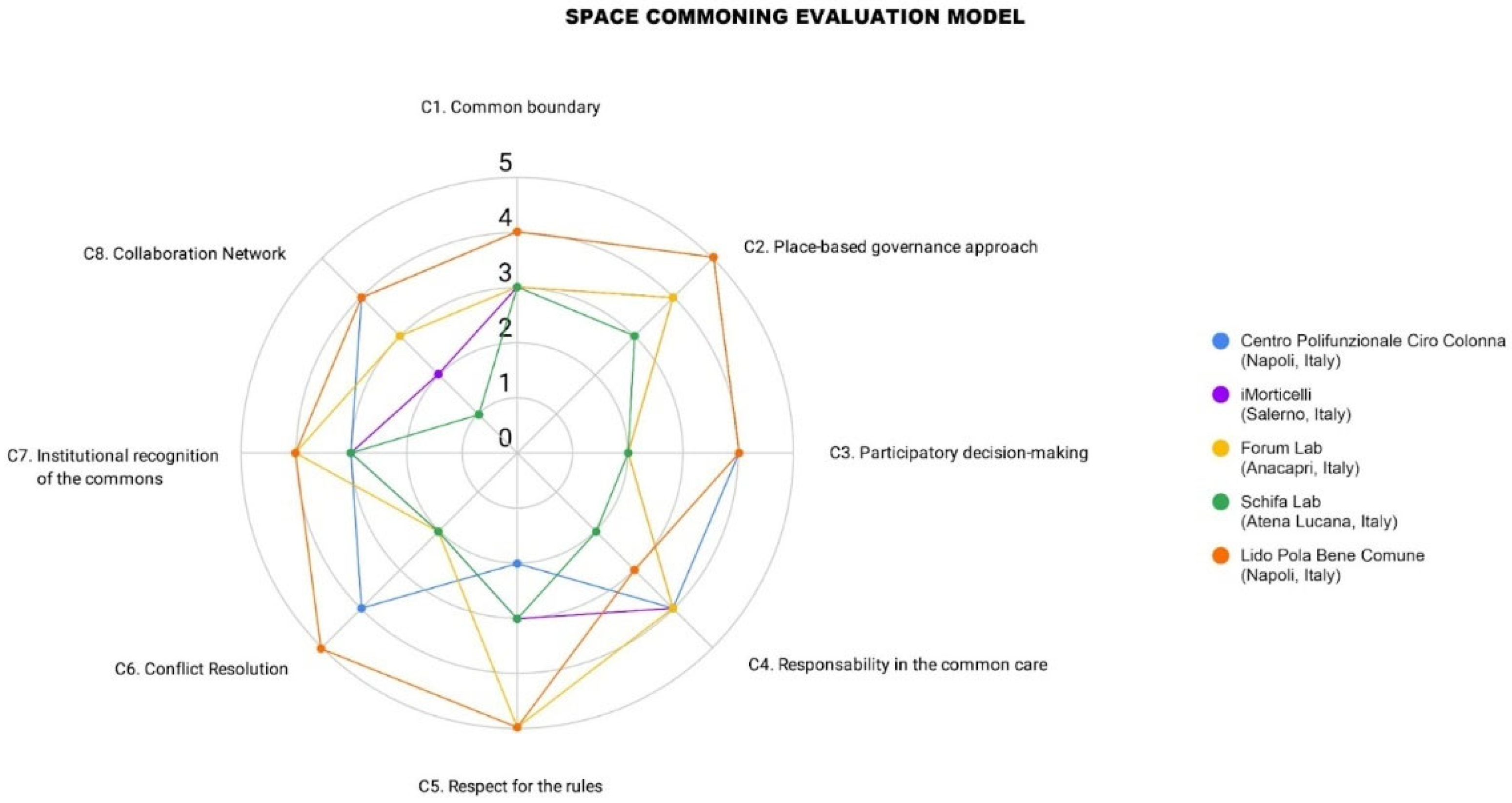

The results obtained, summarised using the Likert scale, were visualised in a radar chart (

Figure 5) [

42] with the aim of more clearly identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the governance of each commons, on the one hand, and, on the other, of visualising, through comparison, the convergences and divergences among the different governance models adopted by the case studies.

The analysis conducted in this study addresses the first research question by highlighting that urban commons, such as those examined, are characterised by shared specific features, albeit applying different approaches and governance systems.

The Lido Pola is a civic-use common in the metropolitan area of Naples since 2016, whose governance appears to be more balanced in respect to others, employing tools and approaches that align closely with the examined literature on urban common goods. Through deliberative approaches and assembly-based instruments such as “Prendi Spazio”, along with the involvement of multiple actors at various scales and levels, Lido Pola manages conflict resolution and adherence to shared rules using a place-based governance approach. In this way, Lido Pola, reaffirming the political role it has developed over time, supports the diverse communities that find in this space opportunities for participation in both place management and the economies that emerge from it. However, there are currently no adequate supervisory tools to ensure continuous oversight and effective protection of the space’s resources, where different needs and communities sometimes compromise its accessibility. Examples include the improper use of adjacent areas, which, during the evening opening of nearby venues, are turned into illegal parking spaces, or the presence of homeless individuals who often take refuge in the semi-basement areas, exacerbating the pre-existing state of urban decay.

The Forum Lab of Anacapri is a highly recognised space by institutions, as it is a public facility granted free of charge to the local youth council. The territorial context contributes to a strong sense of belonging and informal social control, reducing the need for formal sanctions. From key management to the preservation of material assets and the care of its users, the mechanisms of self-organization rely on mutual knowledge among town residents, values of trust, and shared responsibility in defining the few rules that guide the use of the space. Due to the limited presence of social conflicts, the space has not developed collective discussion tools, and decisions are made collectively on a case-by-case basis without guarantees of fairness. At the same time, the various communities within the Forum Lab still have limited decision-making power concerning the primary governance structure of the space, and responsibility for its protection remains in the hands of the dominant actor—in this case, the Anacapri Youth Forum.

The Ciro Colonna Multifunctional Center, a former public school in the Ponticelli district of Naples, is not formally recognised as a commons under the city’s regulations. However, since 2016, it has provided a safe space where families and young people from the neighborhood can engage in recreational, educational, and skill-building activities to shape their future. Located in a highly marginalised area affected by crime, this building offers not only a home but often also employment opportunities to various groups of people who become part of the associations managing it through a Temporary Association of Purpose (ATS). After years of difficult coexistence, the centre now hosts a wide range of activities, thanks to a management statute established only a few years ago. Unlike many other urban commons, the Ciro Colonna Center is a public space managed by private entities that pay a rental fee, yet they claim ownership of the space daily by handling both routine and extraordinary maintenance—from mowing the grass to installing temporary structures. This is made possible by a strong local community committed to its role and determined to protect this hub for neighborhood residents. The formalization of a purpose-driven association for the building has enabled the organization of monthly coordination meetings to manage it with careful and shared planning, facilitating conflict resolution without the need for sanctions. The collaborative spirit aligns with the goals of the participating associations, aiming to give voice to the community in assembly deliberations. Despite the existence of a statute, the co-management of the space remains precarious, often influenced by the quantity and quality of activities taking place in the center. However, the large indoor and outdoor spaces encourage a variety of uses, allowing users to gather or engage separately within its multifunctional setting. Today, the Ciro Colonna Center stands as a unique example of grassroots urban regeneration, where the efforts of citizens and associations have created an exemplary model, both physically and organizationally. It has attracted researchers from around the world eager to study this community. Currently, the centre is part of a broad network of organizations and research institutions, thanks to the educational and cultural projects hosted within its premises.

The iMorticelli Cultural Center and Community Hub, as a public space entrusted to an association through a partially free temporary loan agreement, has a governance structure that differs from the previously mentioned commons. The participatory process through which the adaptive reuse of this space has gradually consolidated the association’s management and shaped its current hybrid use makes its governance highly place-based, capable of adapting to the specific territorial, economic, and social dynamics. For this reason, in addition to the nature of the space as part of the historical and artistic heritage, there is a high level of community responsibility in the collaborative care of the space. This is supported by various monitoring and shared responsibility tools, some formal and others more informal. Key elements include the caretakers, who act as co-managers and points of contact for the surrounding communities, an internal regulation that guides collaborations, a value manifesto co-written in participatory workshops with the community, and a general sense of care and respect among those who frequent the space. At the same time, due to regulatory frameworks that assign responsibility for the space to a single association and coordination strategies aimed at ensuring the center’s economic self-sufficiency, the co-management models in place still reflect imbalanced power dynamics. Additionally, conflict resolution is left to individual or unstructured initiatives, rather than being addressed through formal mechanisms.

Finally, Schifa Lab has the most contracted polygon among the case studies analysed, as it represents a top-down establishment of an urban common good, promoted by the municipality of Atena Lucana. The refunctionalization work and the removal of architectural barriers, carried out through the Archivio Atena project, prevented access to the building for more than a year, temporarily halting the various activities previously hosted within it. For this reason, the level of community participation in decision-making processes is currently low, and the responsibility for the care of the common good and its human resources is perceived as external, largely delegated to higher authorities or individual actors. Due to its reduced and uncertain use, there are currently no dedicated spaces for collective decision-making, and the common good is primarily managed at a local level. However, despite this, some connections with broader institutional networks remain active.

In response to the first research question, it appears that this is largely influenced by the context in which their institutional recognition occurred. From the comparison of the five analysed cases, several key insights emerge. Notably, the two urban commons that have been institutionally recognised as such—Lido Pola and Schifa Lab—are at opposite stages in the transition process from economic goods to common goods. Lido Pola emerged from strongly politicised community struggles, while Schifa Lab was established through the forward-thinking initiative of a municipal administration. On one hand, Lido Pola and the Ciro Colonna Multifunctional Center operate with high levels of informality, fostering enabling processes for communities by enhancing skills and aspirations, but not in economic terms. On the other hand, while iMorticelli also focuses on aspirations, capabilities, and community empowerment, it actively initiates economic processes to make the space and the people managing it financially independent. However, this comes at the expense of a more participatory governance model. Additionally, the unique context of Anacapri, where Forum Lab is located, along with the specificity of its project and target audience, allows for highly streamlined self-organization processes that would be difficult to replicate in urban environments with different population dynamics.

Finally, addressing the second research question, some general considerations emerged from the comparison regarding the evaluation of the criteria defined in the framework. This study examined how local contextual variables shape the practical implementation of governance models for urban commons in the absence of specific regulatory frameworks. Through a comparative analysis of diverse case studies, the research identified key criteria and explored how these are influenced by legal status, spatial configurations, and levels of community engagement.

In doing so, the findings highlight the complexity and adaptability of governance arrangements, revealing how effective models often emerge through informal, context-sensitive practices rather than predefined institutional structures. In particular, the specific characteristics of each urban space can strongly influence the governance model. The presence of heritage-protected properties (such as iMorticelli), spaces that are only partially managed within a larger building (like the cloister of Forum Lab), or partially accessible properties (such as Lido Pola) can result in different levels of responsibility in their management.

Although the literature defines commoners as “groups involved in the management, preservation, and decision-making related to the commons” [

50], this definition is not always sufficient to represent the diverse communities that, to varying degrees, participate (or not) in managing a transitioning urban common good. If management is still structured at the institutional level, assigning responsibility to a single entity and adopting a highly centralised governance approach, this does not necessarily exclude informal attempts at co-governance. In some cases, local communities initiate participatory processes, which, despite being constrained by bureaucratic agreements with the institution, foster shared responsibility or enable the growth of the project, even if this occurs in an uncodified manner that experiments with new forms of social organisation [

23]. In these cases, participants might not be formally considered commoners but still strongly influence the governance model through their involvement, whether occasional, sporadic, continuous, or as volunteers and co-managers.

In this regard, particularly about the third criterion, “Participatory decision-making,” the overarching legal framework governing the space plays a significant role. In the case of a declared common good with civic use (such as Lido Pola), governance naturally adopts a higher degree of informality. Here, responsibility is shared among those involved in managing the space but is also acknowledged and supported by public administration, which assumes key responsibilities. This setup facilitates and encourages governance-sharing processes. Conversely, when the management arrangement is still dictated from above, as in the case of iMorticelli’s partially free-use loan agreement or the cloister’s assignment to the Anacapri Youth Forum (Forum Lab), governance structures tend to be more rigid, with less shared decision-making power.

In this context, the economic dimension also plays a critical role, potentially limiting shared governance processes when economic exchanges become more structured. A shift toward a more stable and income-generating structure can benefit those managing the space professionally, but may come at the expense of informal community participation.

Finally, regarding the criterion “Respect for the rules”, both territorial and spatial conditions have a significant impact on the ability to encourage and regulate compliance. In more informal spaces, particularly in contexts where social ties are built on recognition and trust, the community is more likely to internalise norms naturally. In such cases, rule violations are rare, as self-regulation mechanisms are based on mutual trust and collective responsibility.

6. Conclusions

The growing interest in the commons model reflects the crisis of dominant paradigms, exacerbated by market pressures on the most vulnerable social classes, along with the intensification of liberal development phenomena such as globalization, inequality, and environmental emergencies. In a context where growth and competition continue to reinforce individualism and hyper-competitiveness, limiting spaces for care, creativity, and solidarity, the issue of collective resource management becomes increasingly central.

Starting with Hardin [

31] and later Ostrom [

3], the debate on shared management of common goods has expanded perspectives and opportunities, overcoming the public-private dichotomy, even in urban settings and for non-natural resources. In Italy, legal scholars Rodotà [

15] and Grossi [

13] promoted a legal framework that redefined property ownership around its social function and the recognition of collective management. This approach was later expanded through the formal recognition of civic use rights, a tool for governing urban commons, also known as “emerging commons”.

The complexity of this debate, which navigates between legal issues, property rights, access criteria, and governance, is further heightened in a country like Italy, where the regulatory framework is fragmented between regional and municipal levels. At the same time, a growing civic mobilisation is actively promoting the recovery and enhancement of shared urban spaces, involving third sector organisations, informal communities, and local administrations, often with the support of philanthropic actors.

Within this context, this research aims to shed light on the distinctive characteristics of urban commons, focusing particularly on governance dimensions. It does so by defining an initial set of criteria capable of assessing the commoning stage of a resource as its transition from an economic asset to an urban common good.

Based on a literature review, the COMmoning Places ASSessment Framework (COMPASS) was developed—a set of evaluation criteria designed to compare the governance models of five case studies in Campania, Southern Italy. These include both formally recognised commons and spaces not officially designated as such: iMorticelli in Salerno; Lido Pola Bene Comune and Centro Polifunzionale Ciro Colonna in Naples; Forum Lab in Anacapri; Schifa Lab in Atena Lucana. The comparative analysis revealed convergences and divergences in governance models, as well as the strengths and limitations of the proposed framework, offering key insights to guide the next phases of the research.

Specifically, it emerges that the size and complexity of the territorial context can significantly influence the level of formality or informality in the management of the commons. This is equally affected by the regulatory framework that dictates the reuse of the commons and the entity managing it, whether a formal association or an informal community, such as those structured around civic use rights. At the same time, the formalization of a governance model can have contrasting effects: while a rigid structure ensures stability and control over the process, it may also reduce participation in key decision-making.

An additional element that emerged, although not explicitly investigated in this phase of the research, concerns the economic dimension. Preliminary observations suggest that models oriented towards financial autonomy may impose barriers to widespread participation, whereas more collectively managed and inclusive spaces often facilitate stronger community engagement, albeit with greater ambiguity around financial sustainability and transparency. This insight points to a critical area for future investigation: a more in-depth analysis of the “economic performance–sustainability” criterion, aimed at exploring possible correlations between governance models and economic frameworks, and at understanding how different configurations support or constrain the long-term viability of commons-based initiatives.

Finally, the COMPASS framework has proven to be a valuable investigative and reflective tool—even in its concise form—for exploring governance dynamics across diverse urban commons. Importantly, the framework is not designed for the objective comparison of case studies, but rather to serve as a scientific device to examine governance arrangements and to stimulate reflection both within organisations and across contexts, including comparative analyses involving different territorial or regulatory settings.

The criteria employed—derived from Ostrom’s principles as reinterpreted by Wall [

25]—served as a foundation for constructing the initial evaluation matrix, which may be further expanded or adapted in the future. However, it is essential to acknowledge that any evaluation or decision-making process must remain context-sensitive. While the methodology can inform different stages of assessment, each case requires a tailored approach, based on the specificity of the decision-making problem, the governance structure involved, and the characteristics of the community and space.

To refine the data collected and enhance the robustness of the process, two development strategies could be pursued: expanding and refining the evaluation criteria into more detailed quantitative and qualitative indicators; engaging multiple stakeholders—operating at different levels of commons management and development—in a multi-actor assessment approach that incorporates a plurality of perspectives, especially in evaluating the transformative processes leading to the recognition and consolidation of urban commons.