1. Introduction

Megaprojects have been enduring symbols of political ambition, economic power, and technological advancement throughout history. Monumental developments have shaped civilizations for millennia, from the Pyramids of Egypt and the Great Wall of China to the vast network of Roman city frontiers, each reflecting the strategic, cultural, and engineering prowess of its era. However, the term ‘megaproject’ gained prominence in the modern era, following landmark billion-dollar initiatives such as the Manhattan Project and the Apollo Program, both of which exemplified the fusion of innovation, strategic power, and national prestige. Megaprojects are broadly defined as large-scale, complex investments that often exceed several hundred million dollars, require years to develop and construct, involve multiple public and private stakeholders, and significantly reshape their regions [

1,

2]. While these projects often have profound geographic and economic impacts on large populations, cost remains a primary identifier, set at a minimum of 0.01% of a country’s Gross Domestic Product. Recent studies increasingly emphasize complexity as the defining characteristic of a megaproject, highlighting the intricate interplay of technical, financial, political, and socio-environmental factors. This complexity arises from the scale of coordination required among multiple stakeholders, the integration of advanced technologies, regulatory and geopolitical challenges, and the long-term uncertainties associated with economic, environmental, and societal impacts [

3].

Megaprojects are powerful agents of transformation, reshaping landscapes rapidly, intentionally, and profoundly through large-scale interventions that are both highly visible and far-reaching. Their execution often necessitates the coordinated deployment of capital and state authority, driving infrastructural and economic change on an unprecedented scale [

4]. Often embodying a form of ‘creative destruction’, these projects not only transform physical landscapes, rivers, ecosystems, and urban environments but also displace communities, disrupt social fabrics, and redefine cultural and historical spaces. The consequences of these transformations extend beyond immediate material changes, triggering complex socio-political, economic, and environmental repercussions that persist long after project completion [

5]. Beyond their sheer scale, megaprojects are also defined by a web of highly interlinked complexities that span political, financial, social, and organizational aspects. Their complexities stem from the interplay of competing interests, bureaucratic entanglements, and the challenges of securing and managing large-scale funding, often involving a mix of public and private investment. Political maneuvering, regulatory hurdles, and shifting policy landscapes further complicate decision-making. The governance of these projects demands the coordination of diverse stakeholders, ranging from government agencies and multinational corporations to local communities and advocacy groups. Additionally, megaprojects must navigate evolving environmental regulations, technological uncertainties, and socioeconomic disruptions, making their execution a highly uncertain and financially risky process [

6].

As for urban development, megaprojects represent large-scale capital investments that potentially transform cities through infrastructure expansion, transportation networks, economic revitalization, and urban regeneration. These projects serve as strategic instruments of urban planning, reshaping spatial and economic landscapes while addressing long-term economic growth and political objectives. Their implementation, however, involves navigating complex regulatory frameworks, stakeholder negotiations, and socio-environmental considerations, making them both catalysts for progress and sources of urban controversy. Mega urban development projects are often marked by cost overruns, benefit shortfalls, and serve as focal points for media attention, driven by global or extra-urban ambitions [

7]. Examples include new cities, Olympic games’ venues, skyscrapers, aerospace stations, waterfront developments, theme parks, high-speed rail lines, airports, seaports, continental motorways, dams, and bridges. In China, large-scale projects such as the Shanghai World Expo (

Figure 1), the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macao Bridge (

Figure 2), and the Beijing Olympics have demonstrated the country’s capacity for urban and infrastructural expansion. In North America, Denver’s international airport (USA), Canada’s Confederation Bridge, and the Apollo Program (USA) showcase the region’s advancements in aviation, transportation, and space exploration [

8,

9]. Similarly, Europe has invested heavily in transportation megaprojects, including the UK Channel Tunnel Rail Link and France’s high-speed rail networks in Marseille and Paris. Across Asia, key megaprojects include Thailand’s Second Stage Expressway, Indonesia’s Suramadu Bridge and its national kerosene-to-LPG conversion initiative, Malaysia’s Bakun Hydroelectric Dam, as well as Vietnam’s EPC oil and gas project, all contributing to regional connectivity and energy security. Africa has also witnessed significant megaprojects, such as South Africa’s Cornubia urban development, the FIFA World Cup (2010), and Ghana’s Volta River Project, each addressing critical infrastructure and socio-economic needs. Additionally, South America’s Rio 2016 Olympic Games exemplified the role of global sporting events as catalysts for urban transformation [

1,

8,

10]. These megaprojects, spanning multiple continents, underscore the scale and ambition of modern infrastructure and development efforts, often serving as benchmarks for economic and technological progress.

This study is theoretically grounded and offers a critical–reflective analysis of how megaprojects in the Arab Gulf function symbolically and politically, rather than as subjects of technical post-occupancy evaluation. Focusing on official narratives and secondary sources, the research explores how urban futures are imagined, narrated, and instrumentalized through two iconic cases: Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, UAE, and The Line in NEOM, Saudi Arabia. It interrogates the role of these megaprojects as instruments of nation-branding, techno-futurism, and post-oil economic repositioning. Instead of assessing technical implementation, the study foregrounds how political and economic imperatives are translated into urban imaginaries, as reflected in planning documents, media campaigns, architectural renderings, and national strategies. These discourses are not merely descriptive; they are performative acts that mobilize capital, legitimize governance choices, and shape public perception long before physical realization. This paper positions itself as a foundational contribution that will inform and complement future field-based research, particularly as The Line advances toward physical implementation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a qualitative, comparative case study methodology to critically investigate the political, economic, and spatial logics of urban megaprojects in the Arab Gulf. The case study approach is particularly relevant for analyzing complex, real-world phenomena where multiple variables interact, allowing for in-depth exploration of underlying motivations, institutional frameworks, and projected outcomes [

13]. The study focuses on two emblematic developments: Masdar City (Abu Dhabi, UAE) and The Line (NEOM, Saudi Arabia). These cases were selected based on their symbolic value, high-profile positioning in national visions [

14,

15], and shared aspirations toward ecological and technological urbanism. The comparative analytical approach of this study enables structured yet flexible exploration of megaproject dynamics across different stages of implementation. Masdar City and The Line are at markedly different stages of development. Masdar has progressed to partial implementation since its inception in 2006, whereas The Line remains largely conceptual, with construction in early stages and limited public access. Given this temporal asymmetry, the study relies exclusively on secondary sources, including official project documentation, government policy reports, press releases, investor briefings, news articles, and scholarly literature. It deliberately avoids a conventional empirical evaluation of built outcomes, which would risk analytical imbalance. Moreover, access constraints, such as limited availability of operational performance data, non-disclosure protocols, and restricted field site access, have precluded systematic fieldwork or stakeholder interviews for either project. The study deliberately avoids a conventional empirical evaluation of built outcomes, which would risk analytical imbalance. Instead, it adopts a discursive–comparative framework, focusing on the intentions, narratives, and ideological constructs embedded in each project’s public and official representations.

2.1. Data Collection and Source Transparency

The analysis draws on a curated dataset composed of primary and secondary sources from 2006 to 2024. These include the following:

- -

Official government documents and strategy papers (e.g., UAE Vision 2021 [

14], Saudi Vision 2030 [

15], NEOM Investment Fund [

16], Masdar Urban Design Guidelines [

17]);

- -

Planning reports and environmental assessments as publicly available;

- -

News articles from regional and international media outlets (e.g., Gulf News, The National, Al Arabiya, Bloomberg, Reuters), selected based on relevance and credibility;

- -

Publicly available digital platforms and archives, including promotional websites and official YouTube channels of Masdar and NEOM;

- -

Academic literature on Gulf urbanism, megaproject politics, and sustainability;

- -

Visual and cartographic media, such as master plans, rendered imagery, conceptual maps, and site photographs.

Sources were selected based on the following inclusion criteria:

- -

Direct relevance to governance, planning, technological, economic, or socio-environmental dimensions of each project;

- -

Credibility and origin (i.e., from official, academic, or major media institutions);

- -

Temporal distribution across key milestones in each project’s timeline.

Sources were eliminated based on the following exclusion criteria:

- -

Redundant or purely promotional materials lacking analytical depth or contextual data;

- -

Sources not publicly accessible or unverifiable.

2.2. Analytical Strategy

The study employs critical discourse analysis (CDA) to interpret how each megaproject is framed in strategic narratives, investor rhetoric, and state communication. It particularly focuses on how technological optimism, ecological claims, and post-oil economic futures are constructed and legitimized through discourse. The analysis is grounded in critical urbanism theory, drawing on the work of David Harvey (2003) [

18], Neil Brenner (2004) [

19], and contemporary scholarship on speculative urbanism (Flyvbjerg, 2014 [

1]; Datta, 2015 [

20]). These lenses help reveal underlying power asymmetries, governance tensions, and the strategic use of megaprojects as tools of statecraft and geopolitical branding.

The comparative framework is organized along five analytical dimensions:

Primary Goals of Development.

Governance and Institutional Framework.

Spatial Morphology and Design Logics.

Current State of Development.

The Socioeconomic and Political Context.

By situating Masdar City and The Line within broader debates on megaproject urbanism, the study interrogates their claims to innovation, sustainability, and socio-economic transformation. While The Line remains under construction and largely speculative, its planning logic and projected outcomes are analyzed based on available design frameworks, public statements, and emerging development updates. Overall, this methodological approach allows for a grounded, multi-scalar analysis of how megaprojects in the Gulf region operate as strategic tools for post-oil economic diversification and geopolitical rebranding, while also revealing the socio-spatial tensions and governance challenges that accompany such ambitions.

Access to field sites and project stakeholders is currently limited, particularly in the case of The Line, where physical access is restricted and much of the project remains in the design or planning phase. While limited on-site observation is possible at Masdar City, most existing studies have relied on secondary sources and policy documents, given the constraints on access and the scarcity of publicly available operational performance data. As a result, this study does not incorporate interviews or ethnographic observation. Instead, it mitigates this limitation by focusing on the discursive and symbolic dimensions of megaproject development, in line with established approaches in the urban megaproject literature [

21,

22].

3. Results: Masdar and The Line City Megaprojects

Masdar City in Abu Dhabi and The Line in NEOM, Saudi Arabia, represent two of the most ambitious megaprojects in the Gulf region, each embodying a bold vision for sustainable, technologically advanced urban development. Positioned as experimental models for future cities, both projects seek to redefine the relationship between urbanization, environmental sustainability, and digital integration. Beyond their architectural and infrastructural ambitions, they have garnered significant global attention, reinforcing their host nation’s strategic positioning in discussions on sustainability, innovation, and economic diversification. However, their trajectories differ significantly. Masdar City (

Figure 3) [

23], launched in 2006, has encountered substantial implementation challenges, including financial constraints and difficulties in realizing its original master plan [

24,

25,

26]. In contrast, The Line (

Figure 4), which broke ground in 2021, remains in its early stages, with its feasibility and long-term viability yet to be tested [

27]. This study critically examines these two projects through a comparative analysis of their goals, design principles, socio-political underpinnings, economic feasibility, and broader implications for sustainable urban development.

Before analyzing Masdar City and The Line, the study situates these case studies within the broader landscape of megaprojects currently planned or underway across the Arab region, particularly within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, which aim to reconfigure the region’s global economic influence and strategic positioning. These projects span various sectors and scales and are integral to broader efforts to diversify economies, strengthen international competitiveness, and establish the region as a hub for investment, innovation, and global engagement. Megaprojects have long played a pivotal role in the economic and infrastructural development of the Arab region. Since the oil boom of the 1970s, governments have leveraged large-scale infrastructure investments as a primary strategy for financial expansion and modernization. Initially, these projects focused on foundational infrastructure to support and enhance oil production, thereby facilitating the rapid industrialization of Gulf economies. Over time, however, the scope of megaprojects has expanded significantly, evolving from oil-centric infrastructure to ambitious urban, economic, and cultural developments aimed at reshaping the region’s global economic footprint [

28,

29]. The following is a concise typology of megaprojects in the Arab region and explores the underlying motivations driving their development.

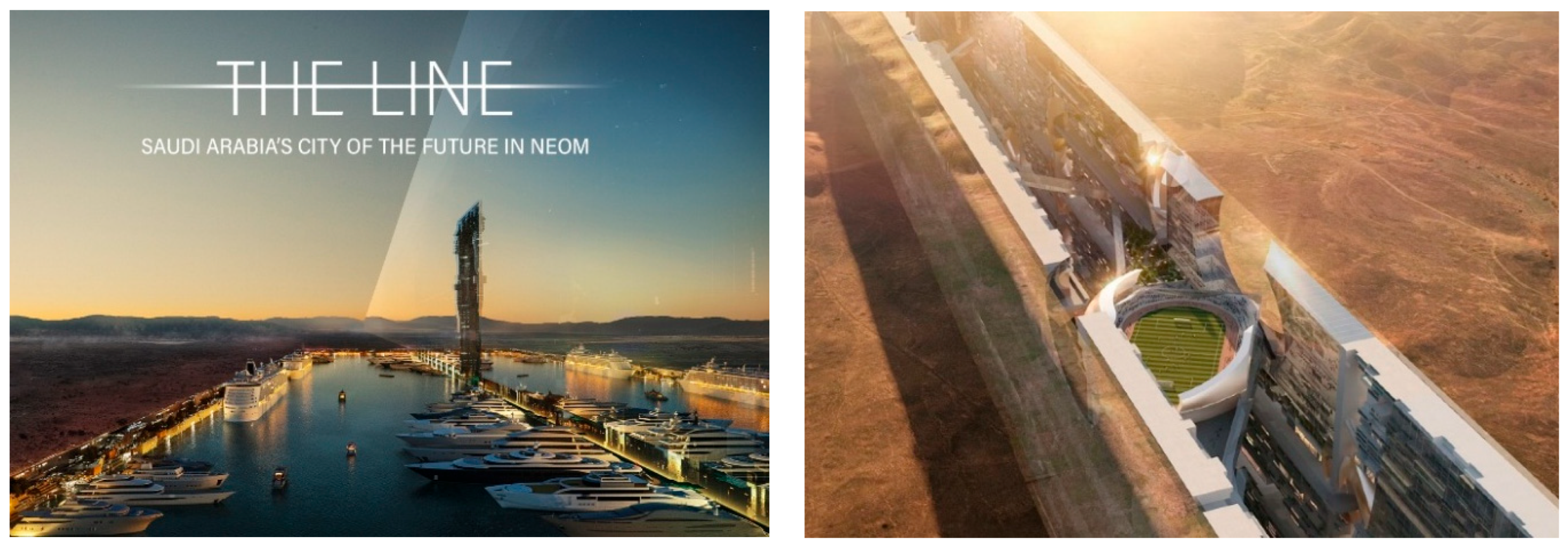

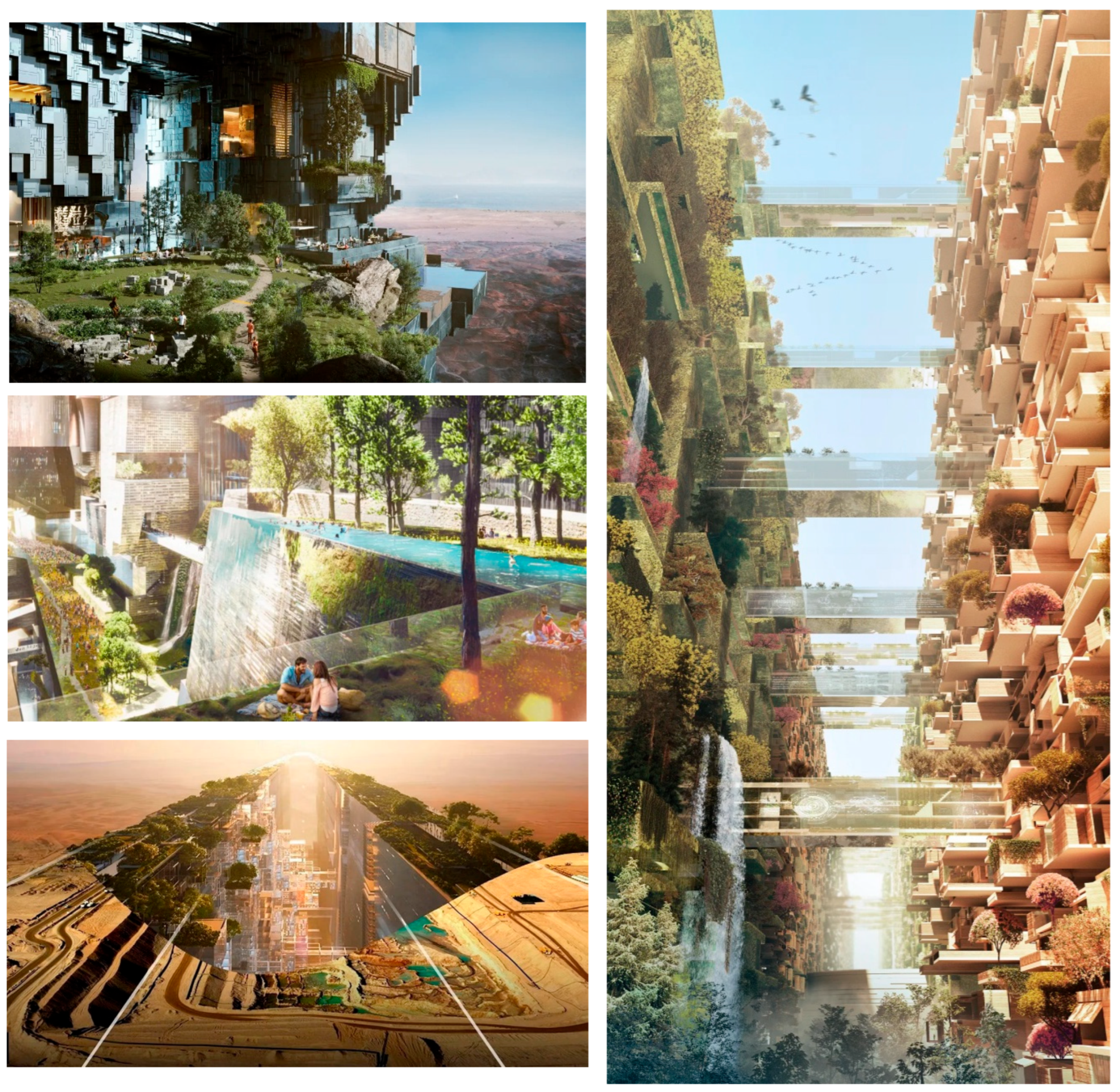

Figure 4.

The Line Conceptual Development Images [

30].

Figure 4.

The Line Conceptual Development Images [

30].

3.1. Diverse Typologies of Contemporary Megaprojects in the Arab Region

The latest wave of megaprojects in the Arab world signifies a strategic shift towards economic diversification and enhanced global competitiveness, encompassing various sectors and objectives. While Egypt’s New Administrative Capital stands out as a notable exception, most large-scale developments are concentrated in the Gulf states, leveraging substantial oil revenues and responding to evolving cultural and social dynamics. These projects reflect a broader ambition to redefine urban landscapes, attract foreign investment, and establish the region as a global leader in innovation, sustainability, and high-tech urbanism. The following account offers a concise typological overview of megaprojects in the Arab region, drawing primarily on a range of interdisciplinary sources [

14,

15,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

3.1.1. New Cities and Urban Developments

Among the most ambitious megaprojects in the Arab region are entirely new urban developments designed to serve as catalysts for economic diversification and technological innovation. NEOM, envisioned as a net-zero carbon city, seeks to attract foreign investment in renewable energy and smart infrastructure, reinforcing Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 objectives of reducing dependence on fossil fuels and redefining the Kingdom’s global image. Similarly, economic cities such as King Abdullah Economic City in Saudi Arabia, Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, and Kuwait’s Silk City are designed as high-tech hubs, integrating cutting-edge sustainability practices and advanced industries to drive long-term economic transformation.

3.1.2. Urban Redevelopment and Cultural Heritage Projects

Large-scale urban regeneration initiatives across the Arab region aim to integrate modern urbanism with cultural heritage while redefining national and global identities. In Saudi Arabia, the New Murabba district in Riyadh, anchored by the monumental Mukaab skyscraper (

Figure 5) [

15], and the Diriyah Development Project exemplify efforts to blend contemporary architecture with historical preservation (

Figure 6) [

15]. Similarly, Abu Dhabi’s Reem and Saadiyat Islands, along with Dubai’s iconic skyscraper developments, have played a pivotal role in reshaping the United Arab Emirates’ global positioning as a hub for innovation, luxury urban living, and cultural tourism (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) [

42,

43].

3.1.3. Tourism and Entertainment Destinations

Tourism and Entertainment Destinations: Saudi Arabia’s flagship tourism megaprojects, such as The Rig, the world’s first offshore adventure tourism destination, Qiddiya motor sports and cultural destinations, and the Red Sea Project, a luxury eco-tourism initiative, underscore the Kingdom’s commitment to positioning itself as a premier global tourism hub. These developments emphasize sustainability, high-end hospitality, and immersive experiences, leveraging the region’s diverse natural landscapes to attract international visitors and investors. Similarly, the United Arab Emirates pioneered this wave of tourism-driven megaprojects with iconic developments such as Palm Jumeirah, the world’s largest artificial island; Burj Khalifa, the tallest skyscraper globally; and Dubai Town Square, an expansive urban entertainment and residential district. These projects have redefined the Gulf’s global identity as a destination for innovation, luxury, and tourism.

3.1.4. Industrial and Economic Zones

Strategic economic hubs such as Jubail, Yanbu, and King Abdullah Economic City (KAEC) in Saudi Arabia, along with Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, are central to the region’s efforts to establish itself as a global leader in advanced industries, sustainable technologies, and international commerce. These megaprojects are key drivers of trade, logistics, manufacturing, and business innovation, facilitating economic diversification and fostering a competitive, knowledge-based economy. By integrating cutting-edge infrastructure and sector-specific clusters, they attract foreign investment and promote growth in petrochemicals, renewable energy, high-tech manufacturing, and entrepreneurship, reinforcing the region’s long-term economic resilience and global market positioning.

3.1.5. Infrastructure and Transportation Networks

Gulf countries invest heavily in modern transportation infrastructure to enhance urban mobility, regional connectivity, and economic integration. The Riyadh and Dammam Metro projects and the Haramain High-Speed Railway in Saudi Arabia aim to reduce congestion, provide sustainable public transit solutions, and transform travel within and between cities. Similarly, the Etihad Rail Network in the UAE is set to revolutionize freight and passenger transport across the Emirates. Qatar’s Doha Metro and Kuwait’s planned Metro Project reflect parallel commitments to urban mobility. These large-scale projects address growing transportation demands, align with broader sustainability goals, and support economic diversification strategies across the Gulf region.

3.1.6. Global Mega-Events

Large-scale international events serve as potent catalysts for infrastructure development, urban expansion, and enhanced global positioning. The Dubai Expo 2020 and Qatar FIFA World Cup 2022 showcased the Gulf region’s capacity to host world-class events, driving transportation, hospitality, and urban infrastructure investments. Building on this momentum, Saudi’s bid to host the FIFA World Cup 2034 is spurring the development of stadiums, smart cities, and large-scale tourism infrastructure. These events enhance regional connectivity, attract foreign investment, and reinforce the Gulf nations’ strategic efforts to project themselves as dynamic global hubs for culture, sports, and innovation.

3.2. Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, UAE

Masdar City embodies an integrated approach to sustainability, economic diversification, and technological advancement. Through its commitment to renewable energy, knowledge-based industries, and urban sustainability, the project provides a blueprint for future cities seeking to balance growth with environmental responsibility. While the initiative has faced challenges in achieving its original zero-carbon vision, it remains a pivotal experiment in sustainable urbanization. As Masdar City continues to evolve, its innovative approach will potentially inspire the development of future smart cities, contributing to the broader global discourse on sustainable urban planning and climate resilience.

3.2.1. Primary Goals of Masdar City Development

Masdar City was conceived as a multifaceted strategic initiative to establish Abu Dhabi as a global leader in renewable energy and sustainable urbanism. Anchored in the UAE Vision 2050, it aims to promote clean energy research, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and contribute to a diversified, post-oil economy [

44,

45,

46]. Through this endeavor, Abu Dhabi seeks to elevate its international standing in the global transition to low-carbon development while stimulating investment in green technologies and creating employment opportunities in emerging sectors. Masdar City is designed to be more than a symbolic commitment—it functions as a living laboratory for sustainable technologies such as solar and wind energy, sustainable water management, and smart urban infrastructure. It cultivates a knowledge-based economy by attracting global research institutions and firms, particularly through the presence of the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology (now part of Khalifa University), the world’s first graduate-level university dedicated to sustainability research [

47,

48]. The project also aspires to serve as a replicable model for sustainable urban development, initially envisioned as a zero-carbon, zero-waste, car-free city aligned with the One Planet Living framework. Although some of its more ambitious goals have since been revised, Masdar City continues to prioritize energy-efficient building systems, integrated public transport, and environmentally responsive urban design. By incorporating passive cooling, shaded walkways, and compact, walkable neighborhoods, it addresses the challenges of livability in arid climates while minimizing ecological impact [

49,

50]. The city’s strategic alignment with global sustainability agendas, such as the Paris Agreement and the UN Sustainable Development Goals, further underscores its role in advancing climate mitigation and resilience [

51,

52]. As a soft power asset, Masdar City enhances the UAE’s international image as a forward-thinking, environmentally responsible nation. It embodies a holistic approach that combines environmental stewardship, economic modernization, and global influence, positioning the UAE at the forefront of future-oriented sustainable development [

30,

53,

54].

3.2.2. Governance and Institutional Framework of Masdar City

Masdar City was conceived and developed under the leadership of Mubadala Development Company, a sovereign wealth fund operating on behalf of the Abu Dhabi government. Its governance structure is emblematic of a centralized and technocratic model, coordinated primarily through the Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council with support from the UAE Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure. Key planning regulations were implemented via Estidama, a locally developed sustainability rating framework that not only standardized construction practices but also positioned Masdar as a global environmental exemplar aligned with national strategic goals [

1,

55,

56]. The governance model, however, was marked by limited stakeholder inclusivity. Decision-making was concentrated within a small network of state-backed planners, international consultants, and sustainability experts. Local municipalities, civil society actors, and residents were largely excluded from shaping planning priorities, implementation processes, or spatial outcomes. This closed-loop approach prioritized elite coordination and expert consensus, minimizing political friction but also curtailing democratic accountability and participatory oversight. Complementary policy instruments, such as land grants, tax exemptions for renewable energy firms, and investment incentives managed by Mubadala, further reinforced this top-down model. Stakeholder involvement remained confined to global consultancy firms, international academic institutions, and government-linked entities, reflecting a governance framework designed to advance strategic objectives rather than foster inclusive urban development [

1,

14,

55,

56].

Beyond its global image, Masdar serves as a domestic tool for political legitimacy. Within the UAE’s centralized governance model, the city demonstrates visionary leadership and institutional capacity to address complex global challenges. The swift execution of Masdar is facilitated by a top-down governance structure that enables efficient decision-making but limits public participation. The absence of meaningful civic engagement in Masdar’s urban development raises critical concerns about inclusivity, accountability, and transparency particularly within centralized, hereditary political systems [

45,

47,

57,

58].

3.2.3. Spatial Morphology and Design Logics of Masdar City

Masdar City’s spatial morphology is rooted in ecological sustainability, combining traditional Middle Eastern design elements with cutting-edge innovations to respond effectively to the arid climate of Abu Dhabi. The city adopts a high-density, low-rise structure to minimize urban sprawl and reduce energy consumption, drawing inspiration from historical Arab cities [

59]. Traditional passive cooling strategies, such as narrow, shaded streets and green linear corridors, are employed to mitigate heat, enhance natural ventilation, and improve outdoor thermal comfort. These spatial configurations channel cool air while expelling hot air, aligning with both environmental responsiveness and cultural heritage. Masdar departs from rigid zoning practices by implementing a mixed-use development strategy, blending residential, commercial, industrial, and recreational spaces to foster integrated and vibrant urban life [

45,

57,

58,

60,

61]. A central planning tenet is walkability, supported by sustainable transport solutions including Personal Rapid Transport (PRT) pods and electric buses, which significantly reduce reliance on fossil-fuel-powered vehicles. Urban growth is planned to maintain a balance between energy infrastructure and livable space, consistent with the One Planet Living framework [

62,

63]. Social and cultural inclusivity is fostered through communal spaces and mixed-use neighborhoods, echoing the diversity and cohesion of traditional Arab cities [

64,

65]. Passive design principles enhance building orientation, airflow, and heat management, complemented by the integration of smart technologies to conserve energy and water and recycle waste. Building performance is regulated through the Pearl Rating System, established by Abu Dhabi’s former Urban Planning Council, which ensures adherence to strict sustainability standards [

47,

66,

67]. Collectively, these strategies create an ecologically balanced urban environment that promotes human well-being while preserving natural resources.

Architecturally, Masdar City blends vernacular design sensibilities with technological innovation to create a sustainable and culturally grounded built environment. Passive cooling strategies such as shaded courtyards, wind towers, and high-performance facades, minimize dependence on mechanical systems while enhancing occupant comfort. Building forms are oriented to optimize natural daylight while controlling solar heat gain, balancing illumination with thermal efficiency [

68]. Smart systems regulate indoor environments, and green construction materials, including recycled steel and low VOC paints, reduce the ecological footprint. Architecture adopts modular, flexible construction methods to enable adaptive reuse and long-term scalability. A hierarchical approach to sustainability is employed: reducing energy demand through passive treatments, followed by the application of efficient building envelopes and the integration of renewable energy systems [

48,

51,

69,

70]. Through this multifaceted approach, Masdar’s architecture embodies a synthesis of tradition and innovation, advancing the city’s overarching goals of sustainability and resilience [

24,

54,

55,

56,

71]. As an eco-city, it aligns with the broader sustainable city framework through its emphasis on resource efficiency, low carbon emissions, renewable energy, and advanced waste and water management systems. While primarily designed for environmental performance, Masdar also exhibits smart city features, such as digital infrastructure, data-driven energy optimization, and AI-enabled services, that enhance urban functionality [

72]. Additionally, its compact urban morphology, shaded pathways, and communal spaces are inspired by traditional Arab cities, demonstrating how cultural heritage can be reinterpreted through contemporary sustainability practices.

3.2.4. Current State of Development and Metrics of Masdar City

Masdar was initially envisioned as a 6-square-kilometer carbon-neutral urban district (

Figure 3 and

Figure 9). However, as of 2024, only around 400,000 square meters, approximately 7% of the planned area, has been developed, with full completion now projected for 2030 [

73]. The city’s master plan allocates 280 hectares for core urban functions, including residential, institutional, and commercial uses, and an additional 71 hectares for renewable energy and utility infrastructure. This includes 33,000 solar panels, wind turbines, and greywater and blackwater recycling systems, contributing to the city’s goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and minimizing resource consumption [

37,

74]. Flagship buildings within the city illustrate its commitment to energy and water efficiency. For example, the Siemens Middle East Headquarters, completed in 2014, achieved LEED Platinum certification and consumes up to 51% less electricity and 54% less potable water than comparable buildings in the region [

75,

76]. Similarly, the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, a collaboration with MIT, was among the first completed structures and serves as a testbed for energy-efficient design and real-time monitoring of building performance [

24,

54].

Recent development has focused on high-performance, mixed-use districts. Masdar City Square (MC

2) spans 29,000 square meters and is anchored by a new net-zero energy headquarters for the Masdar company itself, alongside six buildings targeting LEED Platinum and Gold certifications. Originally scheduled for completion in 2024, the timeline has been extended to mid-2025 [

73]. Another signature project, The Link, is a 30,000 m

2 transit-oriented mixed-use hub that will connect different city zones and integrate commercial, residential, and public spaces. The development is also expected to open in 2025, reinforcing Masdar’s shift from a purely showcase development to an operational urban ecosystem [

74,

77]. Despite slower-than-anticipated progress, Masdar City has achieved substantial milestones in green building performance, urban livability, and renewable energy integration. Nevertheless, the city has been critiqued for its piecemeal growth, limited residential uptake, and reliance on symbolic architecture rather than large-scale socio-economic transformation [

55,

78].

Figure 9.

Vernacular and smart developments of Masdar City, UAE [

23,

26,

79].

Figure 9.

Vernacular and smart developments of Masdar City, UAE [

23,

26,

79].

3.2.5. The Socioeconomic and Political Context of Masdar City: A Critical Examination

Masdar City’s sociopolitical foundations are deeply tied to the UAE’s global ambitions, domestic governance structures, economic diversification strategies, and social fabric. While often celebrated as a groundbreaking sustainability initiative, the project’s underlying motivations extend well beyond environmental concerns. Masdar serves as a strategic instrument for geopolitical influence, political legitimation, and economic transformation, exemplifying the multifaceted role of flagship urban megaprojects in the Gulf. As such, it stands not only as an ambitious experiment in ecological urbanism but also as a revealing case study at the nexus of sustainability, politics, and power in the 21st century Arab world [

45,

48,

54,

56,

58,

71]. One of the key sociopolitical drivers behind Masdar is the UAE’s pursuit of global recognition and soft power. By constructing a high-tech eco-city that hosts international research institutions, global firms, and sustainability conferences, Abu Dhabi projects itself as a forward-thinking leader in climate action and technological innovation. Masdar is part of a broader strategy that includes Expo 2020 and massive investments in renewable energy, efforts aimed at shaping international opinion and showcasing the UAE’s progressive image. However, critics argue that this branding effort may constitute a form of “greenwashing,” masking the environmental contradictions of extravagant infrastructural growth [

46,

50,

52,

53,

69].

Economically, Masdar City plays a pivotal role in Abu Dhabi’s effort to diversify away from oil dependency and build a knowledge-based economy. It aims to attract foreign investment and foster green-sector employment through clean technology and renewable energy industries. Anchored by institutions like the Masdar Institute (now Khalifa University) and partnerships with global firms such as Siemens and IRENA, the city embodies the intersection of economic ambition and environmental innovation. Nonetheless, the prioritization of high-value industries and elite knowledge economies has raised concerns about affordability and access, revealing tensions between profitability and inclusive sustainability [

24,

51,

67,

70].

Socially, Masdar has faced criticism for creating a technologically advanced yet socially exclusive enclave. Designed primarily for professionals and specialists, the city offers limited affordable housing and lacks mechanisms for broader demographic inclusion. Within the UAE’s unique socio-political context, characterized by a citizen minority and a vast expatriate workforce, this exclusivity underscores the difficulty of achieving socially sustainable urbanism. The project’s heavy focus on techno-economic metrics often sidelines cultural, participatory, and equity concerns fundamental to sustainable development [

46,

51,

57,

69,

71].

Aside from these limitations, Masdar City has gained international recognition as a testbed for sustainable urban innovation. Acting as a “living laboratory,” the city enables the testing of advanced technologies such as photovoltaic systems, concentrated solar power (CSP), AI-integrated infrastructure, and energy-efficient urban design. These initiatives align with the UAE’s goal of sourcing 50% of its energy from clean sources by 2050. The research outputs of the Masdar Institute, particularly in fields like desalination, energy storage, and green mobility, position the city as a prototype for urban energy transition and climate adaptation. However, the city’s reliance on state-led investment, slow population growth, and limited replicability in less centralized contexts reveal its inherent constraints as a model for global urban sustainability [

25,

50,

80,

81].

Despite its global branding as a sustainable urban prototype, Masdar City reflects deeper contradictions in its social, economic, and ecological dimensions. While projected as a post-oil, knowledge-based city that champions renewable energy and technological innovation, the development operates within a broader paradigm of exclusionary urbanism that is common among Gulf megaprojects. The socioeconomic structure of Masdar City reproduces the stratified labor regime characteristic of the Gulf region. The project’s high-tech image is supported by a large population of low-wage migrant workers, whose labor in construction, maintenance, and services remains largely invisible in official narratives. These workers, who form the majority of the UAE’s labor force, are often employed under precarious conditions, with limited access to mobility or benefits [

54,

82]. The city’s employment ecosystem remains bifurcated: while institutions like the Masdar Institute generate opportunities for highly skilled professionals, especially expatriates, low-income workers are confined to marginal roles with few prospects for advancement [

83].

Masdar’s residential infrastructure further reflects this stratified hierarchy. Designed according to international green building standards, the housing stock is energy-efficient and technologically advanced, but also expensive and limited in quantity. This model caters to middle- and upper-income knowledge workers while excluding low- and even average-income populations from living within the development. As a result, service and construction workers typically commute from distant, affordable zones, entrenching spatial divisions and undermining the city’s purported walkability and compactness [

55]. Masdar thus contributes to what scholars have termed “eco-enclave urbanism”: developments that meet high environmental benchmarks yet remain socially exclusive [

78].

Although Masdar City did not require mass expropriation, being constructed on previously undeveloped desert land, it indirectly contributes to urban fragmentation in Abu Dhabi. By concentrating resources, policy attention, and infrastructure investments within a self-contained urban district, Masdar perpetuates a dual-track model of development: one that showcases sustainability for global audiences while neglecting the housing and service needs of the broader urban population [

54]. This mirrors wider trends in Gulf urbanism, where elite, high-profile developments often exist in isolation from traditional neighborhoods and public housing sectors. Masdar City reveals how sustainability can be selectively applied within megaproject frameworks, serving as a branding tool while bypassing concerns of labor justice, housing affordability, and ecological balance. The project’s symbolic alignment with global environmental goals masks its embeddedness in systems of labor exclusion, socio-spatial segregation, and ecological disruption.

3.3. The Line City, Neom, Saudi Arabia

NEOM is a flagship urban development initiative launched in 2017 by the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as a central component of KSA Vision 2030. Located in the northwestern region of Saudi Arabia along the Red Sea, NEOM derives its name from the Greek prefix neo (new) and the Arabic word mustaqbal (future), symbolizing a vision for a new future [

27,

33]. Envisioned as a global model for sustainable, technologically integrated urbanism, NEOM aspires to transcend conventional paradigms of city-making by functioning as a living laboratory for innovation, renewable energy, and human-centered design. At the heart of NEOM is The Line, a linear city devoid of cars and emissions, designed to accommodate nine million residents. Structured vertically and composed of three distinct layers, pedestrian, service, and transportation. The Line emphasizes proximity, walkability, and AI-enhanced cognitive infrastructure [

27,

84]. Alongside sub-projects such as ‘Oxagon,’ ‘Trojena,’ and ‘Sindalah,’ NEOM represents an experimental model for autonomous governance, innovative technologies, and economic liberalization. While its aspirations are emblematic of a post-oil, knowledge-based economy, NEOM also faces critical scrutiny. Questions concerning its ecological impact, socio-political implications, economic viability, and the resettlement of local communities remain subjects of ongoing debate [

85]. Nonetheless, NEOM stands as one of the most ambitious and contested urban projects of the 21st century, poised at the intersection of futurism, geopolitics, and sustainability. The following discussion critically examines the Line City through a comparative analysis of its goals, design principles, socio-political underpinnings, economic feasibility, and broader implications for sustainable urban development.

3.3.1. Primary Goals of The Line City Development

The Line City represents an unprecedented experiment in reimagining urban form, sustainability, and national development within the framework of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Its primary objectives include establishing a technologically advanced and environmentally sustainable urban environment that addresses global urbanization challenges while contributing to the country’s economic diversification [

27,

84,

86,

87]. Drawing upon early theoretical frameworks of linear urbanism by Friedman, Archigram, and Soleri [

88,

89,

90,

91], The Line proposes a radical departure from traditional car-centric city models. With its compact, vertically layered skyscraper configuration, stretching 170 km long and only 200 m wide, the city redefines spatial organization and urban morphology. It integrates high-speed transit, walkable enclosures, and renewable energy systems into a mirror-encased, climate-adaptive structure that preserves 95% of the surrounding environment. The vertical zoning system, pedestrian life on the surface, services below, and residences above, minimizes land use while maximizing spatial efficiency, ecological integrity, and livability [

34,

85,

92,

93].

At its core, The Line emphasizes human-centered design and smart technological integration to improve the quality of life for residents. Inspired by the “five-minute city” concept, it ensures that essential services such as healthcare, education, and employment are within walking distance, eliminating the need for automobiles and streets. This pedestrian-first design [

94], promotes well-being, inclusivity, and social cohesion through biophilic design, green corridors, and vertically integrated public spaces. Technological innovation is equally central: the city operates as a digitally native, AI-driven ecosystem equipped with real-time environmental monitoring, predictive energy management, autonomous mobility, and adaptive public services. Leveraging the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data analytics, The Line offers a proactive, responsive urban system that adapts to shifting demands while reducing human intervention in routine functions [

72]. These innovations collectively position the project as a model for smart, resilient, and regenerative cities of the future.

Strategically, The Line plays a vital role in Saudi Arabia’s national transformation by catalyzing post-oil economic diversification. By attracting top-tier talent and international investment across high-tech sectors, such as artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and renewable energy, it aims to foster a dynamic ecosystem of innovation, entrepreneurship, and sustainable growth. The project not only enhances national productivity but also reinforces Saudi Arabia’s global positioning as a forward-thinking hub of sustainable development. By transforming abstract concepts into lived spatial and social realities, the city offers invaluable empirical insight into the scalability and resilience of utopian urban models [

93]. As both a global prototype and a living laboratory, The Line contributes significantly to the evolution of urban theory and practice in the 21st century, aligning ecological stewardship with experimental urbanism and national policy goals.

3.3.2. Governance and Institutional Framework of The Line in Neom

The Line represents a radical experiment in urban governance, characterized by a centralized, corporatized, and highly autonomous administrative model. It is overseen by the NEOM Company, a fully state-owned enterprise under the direct authority of the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF), which operates through the Royal Court. This grants NEOM extraordinary political and operational autonomy, enabling it to function outside the Kingdom’s conventional legal and regulatory frameworks [

95,

96]. Positioned as a “charter city,” NEOM is envisioned to operate under its own set of laws, including distinct immigration systems, economic policies, judicial authority, and land use regulations, all designed to enhance global competitiveness and attract foreign direct investment [

97]. These governance arrangements mirror strategies common in special economic zones but are significantly more expansive, applying to the entire NEOM territory. This includes provisions for full foreign ownership, tax exemptions, and labor deregulation [

98].

Despite its futuristic aspirations, NEOM’s governance model remains opaque. Reports suggest that strategic planning is largely conducted by elite international consultants such as McKinsey & Company and the Boston Consulting Group, in collaboration with royal advisors and high-level state actors, with minimal involvement from local municipalities or public stakeholders [

99]. This top-down, technocratic approach has provoked concerns about the exclusion of local citizenry and rights-based participation, especially in light of reports concerning the resettlement of Indigenous populations [

100]. Rather than mediating stakeholder interests, NEOM’s institutional framework appears to pre-empt potential contestation through legal and regulatory secessionism. The project exemplifies what scholars describe as “territorial reconfiguration,” wherein sovereign space is redefined to facilitate investment, experimentation, and rapid implementation, often at the expense of public transparency and accountability. In this context, governance is less about participatory practices and more about technocratic execution and symbolic statecraft, positioning the state simultaneously as regulator, developer, and global entrepreneur [

101].

3.3.3. Spatial Morphology and Design Logics of The Line in Neom (Figure 10)

The Line reconceptualizes historical linear city concepts through the lens of ecological urbanism, technological advancement, and human-centered design. Inspired by more than 150 years of urban theory, from Arturo Soria y Mata’s Ciudad Lineal (1892) to Nikolay Milyutin’s Soviet-era proposals [

102], The Line’s geometry aims at maximizing accessibility, concentrating infrastructure, and preserving 95% of the natural environment. This vision materializes in a 170 km long, 200 m wide, and 500 m high urban corridor, offering a contemporary alternative to the polycentric and sprawling models that have dominated recent urban development. Rather than expanding outward, The Line’s compact width and high-rise elevation conserves surrounding ecosystems while embedding renewable energy systems, solar, wind, and green hydrogen, to pursue net-zero carbon emissions [

65]. Its regenerative approach goes beyond sustainability by aiming to restore ecological cycles through circular resource flows and biophilic design principles. These strategies draw from ecological design thinking [

103,

104,

105] to shape an urban form that is not only environmentally restorative but also fosters a deep sense of connection between people and nature. Mobility within The Line reflects the logic of high-density, linear urbanism and multimodal accessibility. At the ground level, pedestrian-priority environments place essential services, residential, educational, healthcare, and commercial, within a five-minute walk, in line with walkability research [

106,

107,

108]. Drawing on space syntax theory [

109], the city enhances spatial legibility and promotes social interaction through compact, well-connected layouts. A vertically layered mobility system, featuring pedestrian routes at grade, autonomous transit and logistics networks below, and high-speed vertical circulation above, supports functional separation and efficient movement. This reorganization aligns with the ideals of post-automobile urbanism and advances mobility equity, measured not only in horizontal distance but also in vertical access, service frequency, and network integration [

110,

111].

Figure 10.

The Line spatial morphology and design logics: development and media images [

112].

Figure 10.

The Line spatial morphology and design logics: development and media images [

112].

The project synthesizes theoretical contributions from Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, 1935 [

102], Kenzo Tange’s Tokyo Bay Plan, 1960 [

102], and Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York, 1978 [

102], embedding verticality as a central organizing structure. The Line’s urban morphology also draws from the adaptable visions of Kurokawa’s Metabolism, 1977 [

102], and aligns with the compact city models of sustainable urbanism. The resulting spatial configuration dissolves traditional street hierarchies, creates new forms of spatial interaction, and introduces a “zero-gravity” logic where gravity is no longer a constraint but a design variable. Central to the functioning of The Line is its techno-integrated infrastructure, which transforms the city into a responsive, cybernetic environment. Data-driven systems, including digital twins, IoT networks, and predict ive AI, are embedded into city operations to manage transportation, energy, water, and waste in real-time [

113]. Through interoperable platforms, these technologies integrate across domains to form an intelligent urban ecosystem. At the human scale, technologies such as digital identity, personalized service delivery, and participatory e-governance foster inclusivity and civic engagement, operationalizing the “Responsive City” model [

114,

115,

116]. This shift toward computational urbanism redefines planning and governance as continuous, feedback-rich processes.

The Line’s longitudinal form and modular urban structure are designed to promote equitable access to social infrastructure, such as schools, healthcare, parks, and transit, echoing the principles of the ‘15-min city,’ albeit reinterpreted within a linear spatial framework [

117]. Car-free zones, layered mobility, and pedestrian-prioritized environments mitigate transport-related exclusion while promoting active, safe movement. The design adheres to Net Zero principles [

31], incorporating traffic-calmed zones and universal accessibility to create a spatially just and health-promoting urban environment. Architecturally, The Line functions as a megastructure that integrates infrastructure, architecture, and urban space into a single morphological entity. The mirrored glass façades, which both reflect the desert landscape and reduce solar heat gain, are emblematic of a dual esthetic-environmental logic [

118]. It aligns with passive solar design strategies aimed at minimizing thermal loads while visually minimizing the city’s footprint [

85,

119]. This strategy merges high-performance envelope design with cultural symbolism, echoing the modernist vocabulary while adapting it to the technological and climatic conditions of desert urbanism [

120,

121,

122].

3.3.4. Current State of Development and Structural Envelope Technologies of The Line

The Line construction has progressed primarily through the development of its first major phase, the “Hidden Marina.” This 2.4 km segment is designed to accommodate around 300,000 residents and includes residential, commercial, hospitality, and recreational facilities, all encapsulated within a mirror-clad façade [

123,

124]. Satellite imagery and drone footage confirm that significant groundwork and structural preparations are underway, although full-scale vertical construction is expected to begin in late 2025 [

125,

126]. The next significant milestone is the commencement of vertical construction, scheduled for late 2025. This phase is crucial for realizing The Line’s vision of a vertically integrated, car-free urban environment. However, the project faces ongoing scrutiny regarding environmental impacts, social implications, and financial sustainability, which may influence its trajectory in the coming years. The project’s scope has been scaled back considerably, with revised expectations now focusing on completing this initial section by 2030. Full realization of the 170 km linear city has been postponed to 2045, reflecting challenges related to project financing, fluctuating oil revenues, and hesitancy from global investors [

127].

The Line’s structural envelope features self-shading projections, vertical fins, and recessed facades to control solar gain and reduce reliance on mechanical cooling [

85,

128]. Ventilation strategies such as stack effects, wind catchers, and oriented voids improve airflow and reduce indoor temperatures. These techniques create thermally comfortable microclimates, demonstrating how bioclimatic design principles can be contextually applied to desert megastructures [

86,

129,

130]. The Line’s complex design ambitions are enabled by advanced construction technologies [

131], parametric design tools, and algorithmic engines that generate data-responsive urban planning and component fabrication [

132]. The “One Building, One Detail” concept emphasizes mass customization over mass production, achievable through robotic fabrication and file-to-factory workflows [

34]. Building Information Modeling (BIM), AI, and AR integrate into the construction process to optimize sequencing, quality control, and predictive maintenance [

133]. These systems not only increase construction precision but also reinforce the vision of urbanism as a computational, generative, and performance-based discipline [

134].

3.3.5. The Socioeconomic and Political Context of The Line: A Critical Examination

The Line is framed as a revolutionary urban experiment prioritizing human well-being, social equity, and environmental sustainability. NEOM’s official discourse promises “equal access to views, services, and transport,” alongside “hyper-connected communities” governed by “progressive laws” [

112]. It envisions a post-oil, human-centered society of “safe and happy living, work, and leisure” [

27,

87,

118]. However, such visionary rhetoric masks underlying contradictions between utopian ideals and top-down execution. Megaprojects driven by centralized authorities often relocate local populations and reproduce spatial inequalities under the guise of innovation [

1]. In The Line’s case, reports of resettlement highlight this disconnect between projected futures and existing cultural realities. The project is also embedded in a broader modernization agenda under Vision 2030, aligning urban development with national ambitions of economic diversification and global visibility. Though marketed as inclusive, the vision consolidates state power over urban form and social life [

86]. The planned use of ubiquitous surveillance and AI-driven governance raises serious concerns about privacy, autonomy, and algorithmic control [

115,

135]. As Lefebvre [

136] indicates, space is socially produced, and The Line’s linear, technologically deterministic design risks reducing urban life to a homogenized, tightly controlled system. This conforms to Harvey’s notion of a “spatial fix”, which is a spatial solution to capitalist crises of legitimacy and accumulation [

137]. While promising a human-centric paradigm, The Line reveals sociopolitical tensions between innovation and authority. Despite its egalitarian rhetoric, The Line’s appeal to a global creative elite raises issues of exclusivity and stratification. By privileging access to highly skilled professionals and global investors, it risks becoming an enclave for the cosmopolitan elite, sidelining broader segments of the Saudi population and marginalized communities [

87]. Roy [

138] describes such zones as “territories of exception,” exempt from national regulatory norms and designed to attract capital and talent. This calls into question the project’s claims of inclusivity and justice, particularly in the absence of mechanisms for affordable housing, diverse household representation, and protection for vulnerable groups [

86,

118]. Without civic engagement and respect for cultural diversity, The Line may replicate the very social injustices it seeks to overcome [

139].

At the core of The Line is a technological infrastructure powered by pervasive data collection, algorithmic governance, and ambient intelligence systems [

118,

140]. This “cognitive city” concept relies on constant behavioral monitoring, with Joseph Bradley, CEO of Neom Tech & Digital Company, declaring that trust and data sharing are prerequisites for value creation [

141]. Foucault’s “panopticon” [

142] and Deleuze’s “society of control” [

143] provide useful frameworks for understanding how data-driven governance can internalize surveillance and modulate freedom. Sadowski [

144] warns that smart urbanism often prioritizes optimization over participation, risking detachment from place and community [

114,

140]. The Line is a top-down, state-led project shaped by high modernist principles and centralized planning [

145]. Unlike cities that evolve organically, The Line is preconfigured for efficiency, surveillance, and performance. In contrast, informal settlements like Hong Kong’s Kowloon Walled City (KWC) embodied adaptive, self-organized urbanism with vernacular resilience and social cohesion [

86,

146]. Scholars such as Jacobs [

147] and Holston [

148] argue that urban vitality stems from diversity, flexibility, and participatory governance, qualities often suppressed in deterministic planning models.

Nonetheless, The Line presents a radical rethinking of urban morphology and governance. It integrates vertical density, modular growth, and AI-enhanced infrastructure to form a continuous linear city that challenges polycentric and concentric models [

86,

92,

149,

150]. The project functions as a real-world testing ground for experimental urban theories aimed at climate resilience, regenerative development, and techno-ecological integration. Its construction in a harsh desert region represents an ambitious logistical and infrastructural challenge, requiring innovations in prefabrication, environmental engineering, and supply chain coordination [

1]. The Line reflects the Gulf’s tradition of state-led, performative urbanism [

83], projecting national ambition and technological prowess. It exemplifies “extreme urbanism” in marginal geographies and aligns with Swyngedouw’s concept of “socio-ecological experimentation,” turning urban space into a laboratory of technical performance and symbolic power [

118,

151]. It also aligns with post-carbon urbanism, seeking compact, walkable environments powered by renewable energy and AI-managed services [

152].

The Line’s five-minute city concept, absence of cars, and embedded digital infrastructure mirror regenerative urbanism ideals, aiming to produce, not merely consume, energy and knowledge [

104,

153]. Moreover, The Line embodies the “technologization of urbanism” where cities are conceptualized as cyber-physical systems [

72,

116,

154]. The ambition to integrate autonomous mobility, predictive logistics, and AI-powered household robotics within a vertically layered urban form pushes the boundaries of smart city experimentation [

85,

87]. However, this raises concerns about resettlement, privacy, and human–machine interaction [

155]. The Line’s use of digital twin technology positions it at the frontier of simulation-driven planning, enabling planners to model resilience and behavioral patterns before physical implementation [

92,

115]. This anticipatory approach draws from “design fiction” and “urban prototyping,” allowing for iterative testing of sustainability and livability metrics [

156,

157]. The Line becomes a platform for theorizing the urban through ecological, computational, and ethical frameworks. Yet, critics argue that The Line’s prescriptive and technocratic design may fail to accommodate urban life’s inherent unpredictability and diversity. Centralized control and lack of grassroots engagement could lead to sterile environments devoid of social vitality. As Lefebvre [

136] noted, the production of space is a lived, contested process, not merely a technical exercise. The success of The Line depends not only on technological innovation but on fostering civic inclusivity, adaptability, and spatial justice [

158,

159]. Its function as an urban laboratory must be accompanied by critical inquiry into governance, power, and the long-term implications of algorithmically mediated life [

160]. The Line stands as a bold experiment, an emblem of techno-urban ambition, but also a site of unresolved tensions between innovation and individual autonomy.

4. Discussion: A Comparative Analytical Framework for Masdar and The Line

Despite their differences in scale, form, and operational models, Masdar and The Line projects share a visionary ambition to pioneer sustainable and technologically integrated urbanism in the Gulf Region. They represent flagship urban megaproject experiments and reflect a broader regional commitment to post-oil economic diversification through sustainability, innovation, and advanced infrastructure. Their contrasting spatial strategies, Masdar’s compact, courtyard-based urbanism versus The Line’s linear vertical configuration, offer a rich basis for examining the operational interpretation of ecological ideals. The technological ambitions of each development differ temporally and conceptually: Masdar embodies an early 21st-century smart eco-city model, while The Line represents a next-generation megaproject that integrates artificial intelligence, robotics, and renewable energy systems on a massive scale. This divergence allows for a critical assessment of evolving smart city paradigms in the Gulf.

Notably, both projects are championed by centralized state-dominated planning structures with limited civic participation, raising important questions about the role of governments in shaping future cities. Masdar has faced criticism for falling short of its ambitious goals in terms of occupancy and scalability, whereas The Line remains speculative, though it projects a transformative impact. By comparing their goals, planning and design principles, development typologies, sociopolitical contexts, and implementation challenges, the study contributes to a critical understanding of emerging Gulf urbanism. The chasm between these two megaproject developments reflects contrasting approaches to environmental stewardship and urban innovation and exposes evolving narratives of nation-building, economic diversification, and global competitiveness in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Sustainability in both projects is framed not merely as a design challenge but as a vehicle for ideological expression and geopolitical branding. The following discussion and comparison tables analytically underline the key comparative themes between Masdar and The Line.

4.1. Comparative Analysis Between the Primary Goals—Masdar and The Line (Table 1)

Masdar City creates a feasible, scalable model of sustainability aligned with existing urban development patterns. It emphasizes incremental innovation, renewable energy research, and integration with the existing urban fabric. The Line, by contrast, represents a radical reimagination of urbanism, an ambitious “blank slate” venture that seeks to redefine boundaries through speculative, vertical, and linear design. Masdar’s compact, pedestrian-oriented morphology is rooted in Arab-Islamic urban traditions and passive environmental strategies. It optimizes traditional paradigms. In contrast, The Line proposes an ultra-linear, vertically stratified megastructure that eliminates conventional sprawl, concentrating nine million people into a narrow corridor. This contrast underscores a deep ideological divergence: Masdar experiments within known limits, while The Line reinvents the very idea of urban space. Masdar is a platform for clean-tech research and commercialization, with technology serving its sustainable goals. The Line, however, is an AI-driven ecosystem where digital infrastructure defines governance and experience. Masdar emphasizes human-scaled, ecologically comfortable environments using passive cooling and walkability. The Line offers a hyper-engineered vision of wellness through digital optimization, biophilic design, and vertical zoning. At a policy level, Masdar aligns with the UAE’s soft power and diversification strategy via applied sustainability. The Line, meanwhile, functions as a transformative symbol of Saudi Vision 2030, projecting a bold new identity for the post-oil era. While Masdar reveals the friction between vision and real-world implementation, The Line, still largely conceptual, remains untested and symbolic, a manifesto for future urbanism.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of primary goals—Masdar versus The Line.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of primary goals—Masdar versus The Line.

| Dimension | Masdar City (Abu Dhabi, UAE) | The Line (NEOM, Saudi Arabia) |

|---|

| Core Urban Vision | Pragmatic, compact, low-carbon model city | Radical, vertical, linear smart city with speculative density |

| Design Typology | Traditional-inspired, pedestrian-scaled, mixed-use | Ultra-linear, mirrored façade, vertically layered megastructure |

| Sustainability Goals | Zero-carbon ambition (revised), renewable energy integration | Net-zero carbon, preserve 95% of nature, carbon neutrality by design |

| Technological Role | Enabler of clean-tech innovation and academic research | Embedded, AI-driven, fully automated digital environment |

| Human-Centered Design | Passive design, social interaction, walkability, ecological comfort | “Five-minute city,” sensory optimization, wellness via digital and biophilic design |

| Economic Agenda | Post-oil diversification via clean energy industries and research hubs | Vision 2030 transformation into a global tech-industrial powerhouse |

| Urban Implementation | Phased, partial realization with visible constraints | Yet to be tested; currently speculative with uncertain feasibility |

| Scale and Density | Medium-density, low-rise mixed-use development | High-density, 9 million people in 200 m-wide, 170 km-long linear volume |

| Environmental Strategy | Solar, wind, greywater systems, walkability, passive cooling | Full renewable reliance, mirrored cladding, desert preservation |

| Governance and Ideology | State-led innovation within regulatory frameworks | Top-down, technocratic logic emphasizing control and optimization |

| Urban Theoretical Lineage | New Urbanism, Eco-urbanism, Bioclimatic Design | Linear cities (Hilberseimer, Soleri), Archigram, Cybernetic Urbanism |

| Symbolic Role | Model city for global climate diplomacy | Iconic symbol of Saudi Arabia’s future identity and post-oil ambition |

4.2. Comparative Analysis: Governance and Institutional Framework—Masdar and The Line (Table 2)

The governance models of Masdar City in Abu Dhabi and The Line in NEOM, Saudi Arabia, represent two emblematic but divergent manifestations of state-led megaproject urbanism in the Gulf region. Both projects are rooted in centralized, technocratic planning paradigms that prioritize elite coordination, global branding, and rapid implementation. However, they differ in institutional scope, legal experimentation, stakeholder inclusivity, and geopolitical ambition. Masdar City was conceived under the authority of Mubadala Development Company, a sovereign wealth entity aligned with the Abu Dhabi government. Its planning was coordinated with the Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council and implemented through frameworks such as Estidama, which served both regulatory and symbolic purposes. While Estidama institutionalized sustainable construction practices, the project’s governance remained insular. Participation was largely limited to state-affiliated entities, international consultants, foreign academic partners, sidelining local municipalities and residents. The governance model favored technocratic consensus over participatory engagement, reinforcing Masdar’s position as an environmental showcase rather than a socially embedded urban space. In contrast, The Line exemplifies a more radical form of governance secessionism. Administered by the NEOM Company under the direct auspices of the Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) and the Royal Court, The Line is designed to operate under a semi-sovereign legal regime, distinct from the broader Saudi state. This “charter city” framework envisions its own immigration laws, judicial system, and economic codes, marking a profound institutional divergence from conventional governance models in the region. While this autonomy facilitates accelerated implementation and investor confidence, it raises serious concerns about transparency, civic rights, and territorial justice, especially in light of land expropriation affecting communities such as the Huwaitat tribe.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis: governance frameworks of Masdar City versus The Line.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis: governance frameworks of Masdar City versus The Line.

| Dimension | Masdar City (Abu Dhabi) | The Line (NEOM, Saudi Arabia) |

|---|

| Legal Framework | Operates within UAE legal system; uses Estidama as local regulatory innovation | Charter city with semi-sovereign laws (judiciary, immigration, land use, taxation) |

| Governance Model | Centralized, technocratic, expert-driven | Centralized, corporatized, experimental |

| Stakeholder Inclusion | Limited; dominated by state-affiliated experts, foreign consultants, academic institutions | Extremely limited; largely opaque and elite-driven; minimal local participation |

| Public Participation | Minimal; no formal mechanisms for resident or civil society engagement | Absent; governance by royal decree and elite consultancy |

| Symbolic Role | Environmental and technological flagship for sustainability | Visionary hyper-urbanism, geopolitical futurism, post-oil rebranding |

| Resettlement or Land Controversy | None (developed on uninhabited land) | Yes (the resettlement of the locals) |

| Legal Innovation | Estidama for sustainability ratings within national planning framework | Regulatory secessionism: own laws, courts, economic policies |

| Implementation Strategy | Strategic alignment with national visions

(UAE Vision 2021) | Full integration with Vision 2030 and national transformation strategy |

| Accountability Mechanisms | Weak; little democratic oversight | Non-existent; direct royal oversight with no independent review mechanisms |

| Role of the State | Regulator and strategic investor | Regulator, developer, judiciary, and sovereign authority |

What unites both projects is their strategic function as instruments of nation-branding and economic diversification, designed to signal state capacity, attract global capital, and reposition Gulf cities within post-oil geopolitical narratives. Yet, whereas Masdar City illustrates sustainability through managerialism, The Line advances a vision of sovereignty through innovation and exceptionality. This distinction is not merely rhetorical; it is embedded in the governance structures, legal exceptions, and spatial consequences of each project. Ultimately, both initiatives reflect the evolving ambitions of Gulf monarchies to consolidate state power through urban experimentation, albeit through different institutional mechanisms and degrees of legal innovation. Their governance frameworks foreground an emerging urban condition in the Gulf: one where technopolitical ambition overrides participatory legitimacy, and where the state acts not only as regulator, but also as entrepreneur, image-maker, and global competitor.

4.3. Comparative Analysis: Spatial Morphology and Design Logics—Masdar Versus The Line (Table 3)

Masdar City reflects a climate-responsive, context-sensitive planning model rooted in traditional Middle Eastern urbanism. It favors passive design, mixed-use neighborhoods, and vernacular spatial forms. The Line, by contrast, disrupts horizontal urbanism through vertical modularity and linear form, aiming for spatial equity and environmental regeneration via a single megastructure. Masdar integrates moderate technology to enhance walkability and ecological balance, while The Line is designed as a car-free, multimodal city with cybernetic infrastructure. Masdar grows incrementally with respect to its ecological context; The Line applies a predetermined, large-scale linear extension without local heritage references. This contrast illustrates a divide between contextual adaptation and theoretical experimentation. Architecturally, Masdar City embraces a vernacular-modern hybrid that is adaptive, modest in scale, and embedded in cultural and climatic realities. It employs passive strategies such as wind towers and shaded courtyards to ensure thermal comfort with minimal mechanical intervention. Materials are resource-efficient, and design is modular and scalable. In contrast, The Line envisions a futuristic megastructure inspired by metabolist and arcological theories. Its mirrored façade and vertical integration represent a departure from site-specific design. Sustainability is achieved through high-tech systems and universal modularity rather than passive adaptation. While Masdar’s architecture emphasizes incremental change and cultural continuity, The Line prioritizes technological orchestration and symbolic form. The epistemological divide between Masdar’s environmentalism and The Line’s techno-urbanism defines their respective architectural philosophies.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis: spatial morphology and design logic, Masdar versus The Line.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis: spatial morphology and design logic, Masdar versus The Line.

| Category | Masdar City | The Line |

|---|

| Urban Form | Compact, high-density, low-rise, inspired by traditional Arab cities, courtyard-based, human-scaled | Linear megastructure integrating infrastructure and architecture, ultra-high-density, vertically stratified. |

| Social-Spatial Logic | Emphasizes human scale, social inclusivity through urban porosity | Prioritizes efficiency and equal access through vertical hierarchy |

| Typological Framework | Plural: eco-city, sustainable city, smart city, traditional Arab city | Singular: linear megastructure integrating infrastructure and architecture |

| Cultural Reference | Strong vernacular influence from Arab-Islamic cities | Minimalist esthetic; abstracted modernist references |

| Spatial Equity | Socially inclusive design with traditional urban values and communal spaces | Equitable access engineered via modularity, universal design, and service distribution |

| Growth Model | Controlled expansion respecting ecological limits | Predefined, large-scale linear extension with fixed cross-sectional profile |

| Ecological and Environmental Strategies | One Planet Living framework. Zero carbon, passive cooling, natural ventilation, wind towers, shading, natural ventilation | Net-zero carbon, regenerative systems, biophilic integration, 95% land conservation. Mirrored facades for solar reflectivity; high-tech climate control |

| Architectural Philosophy | Vernacular-modern synthesis; passive-first, adaptive design | Visionary megastructure; techno-centric and vertically integrated |