Drivers of Public Welfare Land Ratios for Regional Development in China: A Central–Local Interaction Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Central–Local Relations in Land Expropriation

2.1. The Game Between Central and Grassroots Governments in Policy Implementation

2.2. Local Government Choices and Goal Achievement in Land Expropriation

2.3. Policy Experiment Improvement Mechanism Under Central–Local Interaction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

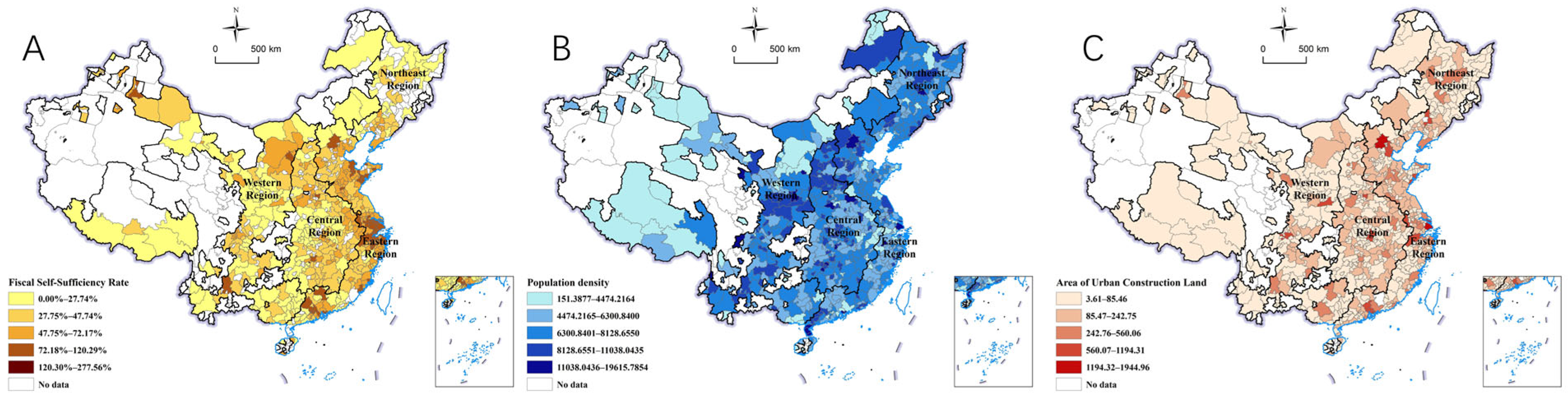

3.2. Variable Selection

- (1)

- Dependent variables

- (2)

- Explanatory variables

3.3. Research Model

4. Results

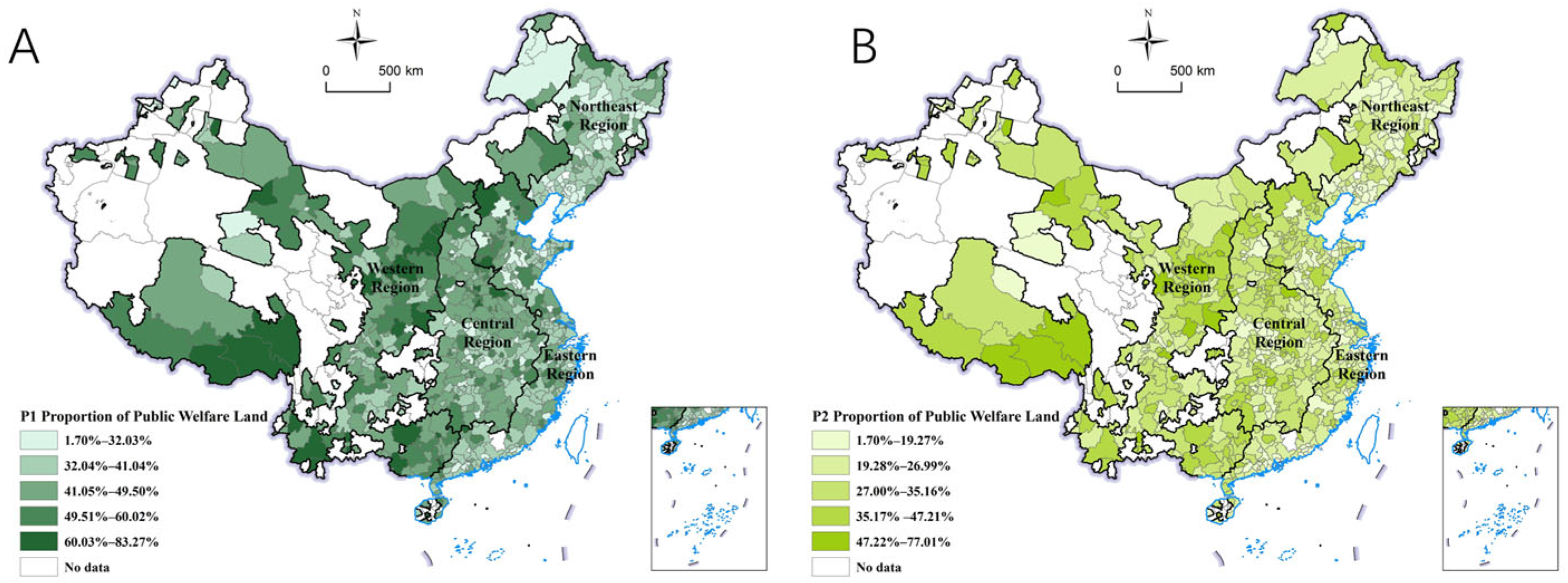

4.1. Spatial and Temporal Variations in the Proportion of Public Welfare Land

4.2. Factors Affecting the Proportion of Public Welfare Land at Different Scales

4.3. Factors Influencing the Proportion of Public Welfare Land in Different Regions

4.4. Testing for Multicollinearity Among Explanatory Variables

5. Discussion

5.1. Regional Economic Development and Public Welfare Land Allocation

5.2. Administrative Hierarchy and Governance Mechanisms

5.3. Fiscal Capacity and Strategic Behavior of Local Governments

5.4. The Role of Provincial Governments as Policy Intermediaries

5.5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Schutter, O. How not to think of land-grabbing: Three critiques of large-scale investments in farmland. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Feder, G. Land registration, governance, and development: Evidence and implications for policy. World Bank. Res. Obs. 2009, 24, 233–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50137-2011; Code for Classification of Urban Land Use and Planning Standards of Development Land. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Cai, M. Land for welfare in China. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.C.; Yi, F. Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geogr. 2011, 32, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Wong, S.; Liu, S. Institutions, property taxation and local government finance in China. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 847–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, F.; Webster, C. Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1919–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Feng, C.; Tao, R. Local “land finance” in China’s urban expansion: Challenges and solutions. China World Econ. 2008, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. Who owns China’s land? Policies, property rights and deliberate institutional ambiguity. China Q. 2001, 166, 394–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yao, S. A scientific thought about urbanization progress in China. Human. Geogr. 2007, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Chan, R.C. On ‘Land Finance’ in urban China: Theory and practice. Habitat. Int. 2018, 75, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Su, F.; Liu, M.; Cao, G. Land leasing and local public finance in China’s regional development: Evidence from prefecture-level cities. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2217–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, P.; Shi, X.; Gao, J.; Feng, S.; Qu, F. Demystifying the key for intoxicating land finance in China: An empirical study through the lens of government expenditure. Land Use Policy 2019, 85, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, J.; Niu, Y. Role of foreign direct investment and fiscal decentralization on urban haze pollution in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 305, 114287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, C.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, X. Fiscal incentive, political incentive, and strategic interaction of illegal land use by local governments. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wu, Y.; Choguill, C.L.; Luo, J.; Yu, X. Reflections on TOD in China: From land finance to inclusive growth. J. Urban Manag. 2024, 13, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Niu, Y.; Lichtenberg, E. Spending preferences of local officials with off-budget land revenues of Chinese cities. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 31, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.-N.; Huang, J.-T.; Chiang, T.-F. Empirical study of the local government deficit, land finance and real estate markets in China. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 32, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, H. Effects of land urbanization and land finance on carbon emissions: A panel data analysis for Chinese provinces. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.T.; Zhang, J.T. Study on the Urban Land Expansion in the Urbanization of China. Mod. Urban. Res. 2011, 26, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, F. Housing wealth and fertility: Evidence from China. J. Popul. Econ. 2023, 36, 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Heerink, N.; Yu, L. Real estate boom and resource misallocation in manufacturing industries: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Ji, A.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Ni, A.; Lu, W. Policy implications of the transit metropolis project: A quasi-natural experiment from China. Transp. Policy 2025, 162, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. From Economic Policy to Social Policy: Explanation of the Institutional Changes in Land Acquisition. China Land. Sci. 2021, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. Legal and political practices in China’s central–local dynamics. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 14, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, L.; Friedmann, J. Restructuring urban governance: Community construction in contemporary China. City 2008, 12, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lu, X.; Liu, Q.; Chang, C.; Qu, L. The effects of land transfer marketization on the urban land use efficiency: An empirical study based on 285 cities in China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R. On the reform and construction of the property right system of natural resources assets. China Land. Sci. 2021, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, L. Centrifugal Empire: Central-Local Relations in China; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.P. Central–Local relations in an era of fiscal decline: The paradox of fiscal decentralization in post-Mao China. China Q. 1991, 128, 691–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, Z.; Tucker, S.; Hassan, G.M. Heterogeneous productivity stabilizes public good contributions under certainty, uncertainty and ambiguity. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2024, 110, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Ali, S.; Dong, K.; Li, R.Y.M. How does fiscal decentralization affect CO2 emissions? The roles of institutions and human capital. Energy Econ. 2021, 94, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryson, P.J.; Cornia, G.C. Slovakia’s surge: The new system’s impact on fiscal decentralisation. Post-Communist Econ. 2006, 18, 437–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.B.; Treisman, D. Did government decentralization cause China’s economic miracle? World Polit. 2006, 58, 505–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F.; Bidegain, G.; Monestier, F.; Rodríguez, R.P. A Natural Experiment in Political Decentralization: Local Institutions and Citizens’ Political Engagement in Uruguay. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 2015, 57, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, S. From Local Experiments to National Policy: The Origins of China’s Distinctive Policy Process. In Red Swan: How Unorthodox Policy-Making Facilitated China’s Rise; The Chinese University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2018; Volume 59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Feng, S.Y.; Qu, F.T. Reform of rural collective property rights system: Theoretical explanation and case evidence. Manag. World 2021, 37, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.M. Bureaucratic Politics and Chinese Foreign Policy-making. Chin. J. Int. Polit. 2016, 9, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Coate, S. Centralized versus decentralized provision of local public goods: A political economy approach. J. Public Econ. 2003, 87, 2611–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. Hierarchies and Bureaucracies: On the Role of Collusion in Organizations. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1986, 2, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Wang, Q.R.; Tan, R. Rural Land Policy Reform Pilot under the New Urbanization Strategy; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X. Can land market development suppress illegal land use in China? Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.L. Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land. Use Policy 2022, 112, 104412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development. J. Econ. Lit. 2011, 49, 1076–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.J.; Qi, H. The Effect of Local Government’s Monopoly of Primary Land Market on the Formation and Dynamic Change of Land Finance: Empirical Evidence from the Establishment of Land Reserve System. China Land. Sci. 2019, 33, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.M.; Hu, H.W.; Zhou, T.X. Priority Tasks Driven, Fiscal Revenue Growth and China’s Rural Construction Land Marketization. China Land. Sci. 2023, 37, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.Y.; Wang, Z.F.; Zhang, W.F. The exhaustion of China’s “land-driven development” mode: An analysis based on threshold regression. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Nath, N.; Murayama, A.; Manabe, R. Transit-oriented development with urban sprawl? Four phases of urban growth and policy intervention in Tokyo. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Ma, W. Government intervention in city development of China: A tool of land supply. Land. Use Policy 2009, 26, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, W. The urbanization efficiency in Chengdu City: An estimation based on a three-stage DEA model. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2017, 101, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R. China’s Land Security Review; Gold Wall Press/Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.; Yi, Z.; Tiantian, C. Land remise income and remise price during China’s transitional period from the perspective of fiscal decentralization and economic assessment. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.D.; Yan, Y.F.; Cao, Y.M.; Cui, Y.; Chang, I.S.; Wu, J. Marine ecological security shelter in China: Concept, policy framework, mechanism and implementation obstacles. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Yigiter, A.; Xu, H.Y.; Berman, A.E.; Chen, J. Early detection of change patterns in COVID-19 incidence and the implementation of public health policies: A multi-national study. Public Health Pract. 2021, 2, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.M. Policy Sciences; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lampton, D.M. Chinese-Politics-the Bargaining Treadmill. Issues Stud. 1987, 23, 11–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.S.; Zhou, X.Y. Issue Attribute and Knowledge Production of Policy Experimentation: The Case Study Based on the Reform of Urban Land-use Rights. Manag. World 2022, 38, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB50180-2018; Standard for Urban Residential Area Planning and Design. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Huang, Y.S. Central-local relations in China during the reform era: The economic and institutional dimensions. World Dev. 1996, 24, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.D.; Liao, F.H.; Huang, Z.J. Administrative hierarchy and urban land expansion in transitional China. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.H.F.; Wei, Y.D. Dynamics, space, and regional inequality in provincial China: A case study of Guangdong province. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wei, Y.D. Economic Transition, Urban Hierarchy, and Service Industry Growth in China. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Ge 2018, 109, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.F.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, Z.J. Fiscal decentralization, political centralization, and land urbanization in China. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L. Why do local officials bet on the strong? Drawing lessons from China’s village redevelopment program. China J. 2015, 74, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Proportion of Public Welfare Land in Urban Built-Up Areas in 2012 | Proportion of Public Welfare Land in Urban Built-Up Areas in 2019 | Change Situation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥4 hm2 | <4 hm2 | ≥4 hm2 | <4 hm2 | ≥4 hm2 | <4 hm2 | |

| National Average | 38.5% | 26.5% | 41.21% | 25.21% | 2.69% | 1.37% |

| Eastern Region | 35.6% | 23.9% | 39.60% | 23.66% | 3.99% | 0.29% |

| Western Region | 43.3% | 31.0% | 44.93% | 28.23% | 1.54% | 2.84% |

| Central Region | 42.1% | 30.4% | 43.52% | 27.54% | 1.38% | 2.92% |

| Northeast Region | 35.8% | 24.1% | 35.59% | 21.12% | −0.26% | 3.01% |

| Variable Name | Coef. (≥4 hm2) | p > |t| (≥4 hm2) | Coef. (<4 hm2) | p > |t| (<4 hm2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population density | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | <0.001 | |

| Land expropriation for the current year | −0.073 | 0.192 | 0.003 | 0.654 | |

| Expansion in the past five years | 0.037 | 0.043 | 0.019 | 0.254 | |

| City region | Eastern region | 0.080 | <0.001 | 0.060 | <0.001 |

| Western region | 0.079 | <0.001 | 0.066 | <0.001 | |

| Central region | 0.124 | <0.001 | 0.103 | <0.001 | |

| City size | Type II small city | 0.119 | 0.002 | 0.108 | 0.003 |

| Type I small city | 0.081 | 0.031 | 0.081 | 0.02 | |

| Medium-sized city | 0.059 | 0.111 | 0.046 | 0.18 | |

| Type II large city | 0.047 | 0.197 | 0.035 | 0.297 | |

| Super city | −0.015 | 0.673 | −0.017 | 0.607 | |

| Mega city | −0.047 | 0.452 | −0.062 | 0.28 | |

| City administrative level | Prefecture-level city | 0.036 | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.003 |

| Provincial capital | 0.076 | 0.025 | 0.064 | 0.043 | |

| Separately listed city | 0.052 | 0.351 | 0.026 | 0.612 | |

| Municipality | 0.059 | 0.496 | 0.072 | 0.369 | |

| Parcel Area City Level | County-Level City | Prefecture-Level City | Provincial Capital | Separately Listed City | Municipality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥4 ha | 43.73% | 48.83% | 42.95% | 36.42% | 39.54% |

| <4 ha | 28.25% | 32.27% | 26.35% | 18.78% | 24.67% |

| City | City Type | Per Capita Disposable Income/CNY | Land Finance Dependency | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guangzhou | Super city | 68,304 | 68,304 | 107% | 107% |

| Hangzhou | Mega city | 61,879 | 52,531 | 140% | 117% |

| Wuhan | Mega city | 50,362 | 113% | ||

| Xi’an | Mega city | 35,783 | 107% | ||

| Nanjing | Mega city | 60,606 | 107% | ||

| Wenzhou | Large city | 54,025 | 43,922.4 | 179% | 147% |

| Kunming | Large city | 48,018 | 163% | ||

| Fuzhou | Large city | 40,477 | 153% | ||

| Taiyuan | Large city | 35,473 | 126% | ||

| Hefei | Large city | 41,619 | 116% | ||

| Influencing Factors Region | Northeastern | Eastern Region | Central Region | Western Region | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | p > |t| | Coef. | p > |t| | Coef. | p > |t| | Coef. | p > |t| | ||

| Population density | 0.000 | 0.171 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.000 | <0.001 | 0.000 | 0.707 | |

| Land expropriation ratio for the year 2019 | 0.505 | 0.199 | −0.232 | 0.047 | −0.135 | 0.068 | 0.005 | 0.517 | |

| Expansion ratio of built-up areas in the past five years | 0.085 | 0.190 | −0.050 | 0.218 | 0.039 | 0.186 | 0.090 | 0.007 | |

| Fiscal self-sufficiency rate | 0.052 | 0.653 | 0.015 | 0.696 | 0.021 | 0.492 | −0.163 | 0.043 | |

| Urban scale | Super city | - | - | −0.059 | 0.460 | - | −0.047 | 0.686 | |

| Mega city | 0.014 | 0.897 | 0.006 | 0.918 | −0.055 | 0.509 | −0.089 | 0.336 | |

| Type II large city | 0.018 | 0.908 | 0.082 | 0.089 | −0.054 | 0.455 | 0.024 | 0.741 | |

| Medium-sized city | 0.036 | 0.806 | 0.079 | 0.110 | −0.041 | 0.552 | 0.058 | 0.461 | |

| Type I small city | 0.045 | 0.757 | 0.101 | 0.050 | −0.067 | 0.294 | 0.105 | 0.184 | |

| Type II small city | 0.081 | 0.569 | 0.155 | 0.005 | −0.044 | 0.495 | 0.160 | 0.050 | |

| Administrative level | Municipality | - | 0.040 | 0.724 | - | 0.143 | 0.350 | ||

| Provincial capital | 0.089 | 0.420 | 0.078 | 0.166 | - | 0.116 | 0.036 | ||

| Separately listed city | - | 0.064 | 0.352 | - | - | ||||

| Prefecture-level city | 0.040 | 0.235 | 0.017 | 0.442 | 0.009 | 0.739 | 0.068 | <0.001 | |

| Variables | Density | Size | Region | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | 1.000 | |||

| Size | −0.037 | 1.000 | ||

| Region | −0.112 | −0.049 | 1.000 | |

| Level | 0.052 | 0.024 | 0.051 | 1.000 |

| Self | −0.070 | 0.051 | −0.286 *** | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dai, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Qi, X. Drivers of Public Welfare Land Ratios for Regional Development in China: A Central–Local Interaction Perspective. Land 2025, 14, 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061208

Dai J, Wang Q, Zhou X, Qi X. Drivers of Public Welfare Land Ratios for Regional Development in China: A Central–Local Interaction Perspective. Land. 2025; 14(6):1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061208

Chicago/Turabian StyleDai, Jin, Qingbin Wang, Xiongwei Zhou, and Xinxian Qi. 2025. "Drivers of Public Welfare Land Ratios for Regional Development in China: A Central–Local Interaction Perspective" Land 14, no. 6: 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061208

APA StyleDai, J., Wang, Q., Zhou, X., & Qi, X. (2025). Drivers of Public Welfare Land Ratios for Regional Development in China: A Central–Local Interaction Perspective. Land, 14(6), 1208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14061208