Abstract

Rural public cultural spaces serve as vital venues for information exchange, interpersonal interaction, and cultural and leisure activities in rural communities. Since the Rural Revitalization Strategy was proposed in 2017, the planning and provision of rural public cultural spaces have attracted increasing attention in China. However, many such spaces remain underutilized, accompanied by low levels of user satisfaction among villagers. A key reason for this is the mismatch between standardized spatial configurations and villagers’ dynamic functional needs. Drawing on Hertzberger’s theory of spatial polyvalence, this study proposes a framework to evaluate spatial flexibility in rural public cultural spaces. The framework introduces quantitative indicators and computational methods across two dimensions: “competence”, referring to a space’s potential to accommodate multiple functions, and “performance”, reflecting the efficiency of functional transformation during actual use. Employing the proposed method, this study conducts a case analysis of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center in Shanghai to evaluate its spatial characteristics and actual usage. The evaluation reveals two key issues at the overall level: (1) many residual spaces remain undesigned and lack strategies to support spontaneous use; (2) the spatial layout shows rigid public–private divisions, with little adaptability. At the room level, spaces such as the elevator, hairdressing room, party secretary’s office, and health center are functionally rigid and underutilized. Drawing on exemplary cases, this study proposes several key strategies such as (1) optimizing and innovatively activating residual spaces, (2) integrating multifunctional programs, and (3) improving spatial inclusiveness.

1. Introduction

Rural public cultural spaces, as important community-level sites that support local residents’ communication and cultural activities [1], while embodying distinctive characteristics of rural culture, exert a significant influence on villagers’ cultural and spiritual lives [2]. Given the unique socio-economic conditions and the production and living patterns of rural residents, these spaces exhibit notable characteristics of locality and spontaneity in terms of type, function, site selection, planning, and operation. Since the implementation of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy in 2017 [3], governments at all levels have driven the construction of rural public cultural facilities, advancing the modernization and standardization of rural infrastructure. As the planning, design, and operation of these facilities often adopt or replicate the concepts and models of urban public facilities without fully accounting for the unique environmental characteristics and the needs of the resident of the villages, issues such as spatial homogenization, functional redundancy, and urbanization tendencies have emerged. Such a replication-based approach contradicts some fundamental theoretical and methodological principles, e.g., for sustainable rural development, it is essential to highlight and build upon the distinctive characteristics of village construction [4] rather than to simply copy external approaches and models; some methods originally developed for urban contexts, still require critical validation regarding their applicability to rural environments [5]. Consequently, a widespread mismatch between planned functions and actual usage has become evident [6].

Previous studies have examined various aspects of rural public cultural spaces, including types and characteristics [7], their roles for villagers [8,9], stakeholder collaboration and community participation [10], generational and gender-based differences in user satisfaction [11], current status and development trends [12,13], spatial pattern and evolution mechanisms [14,15], and sense of place [16]. Focusing on spatial evaluation, Micek and Staszewska [17] proposed a framework that quantifies users’ subjective spatial perceptions across eight dimensions, including functionality, practicality, and reliability. They used bipolar adjective pairs and a five-point scale, offering a structured approach for evaluating and visualizing spatial quality. Zheng et al. [18] developed a spatial vitality evaluation model for suburban rural public spaces by integrating GPS trajectory tracking and cognitive mapping to analyze behavioral patterns of both the residents and tourists in the Shecun Community, Nanjing. Liu and Wang [19] introduced a siting analysis method for rural public cultural spaces using a path-clustering algorithm and validated it through a case study in Yumin Township, Yushu City, Jilin Province. Their approach offers a replicable framework for optimizing cultural space layout in rural areas. Fu and Hou [20] drew upon the dimensional system of scene theory to construct an analytical framework for rural public cultural spaces in China, encompassing three layers: physical space, activity space, and institutional space.

However, current research on rural public cultural spaces rarely addresses the issue of spatial flexibility from a fine-grained, design-operational perspective, and instead tends to remain at a broad conceptual or strategic level. This gap has, in part, contributed to a mismatch between planning intentions, spatial design, and the actual use of such spaces. More specifically, this study attempts to address two interrelated key problems: (1) At the methodological level, user needs for rural public cultural spaces have become increasingly diverse and fluid. However, spatial flexibility remains an underexplored and under-quantified dimension in both the evaluation and design methodologies of such spaces, often resulting in functional obsolescence and inefficiencies; (2) at the practical level, mainstream planning practices continue to rely on predefined, fixed-function zoning schemes for rural public cultural spaces, with little potential to support adaptive and flexible uses.

Accordingly, establishing an indicator system to evaluate the spatial flexibility of rural public rural spaces has become an urgent research priority. In this context, this study addresses two core research questions: (1) What are the key dimensions for evaluating the flexibility of rural public cultural spaces? This involves selecting an appropriate theoretical perspective and constructing an evaluation indicator system that reflects the specific characteristics of such spaces. (2) How can this evaluation be implemented from an empirical and practice-oriented perspective? This includes case selection, operational procedures, and critical reflection.

This study develops a spatial flexibility evaluation framework for rural public cultural spaces, drawing upon Herman Hertzberger’s theory of polyvalence. The framework is structured around two primary dimensions, competence and performance, encompassing seven sub-dimensions, i.e., structural adaptability, spatial order, collectivity, place-ness, stimulation, public–private relationship, and in-between spaces. An empirical study was conducted using the proposed framework to assess the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center in Shanghai, which serves as a representative case within the district-wide Wojia Neighborhood Center initiative led by the Jiading District Government. Recognized as one of China’s 2024 National Exemplary Rural Public Service Cases, the Wojia Neighborhood Center program aims to enhance grassroots governance and service delivery through integrated planning and full-lifecycle spatial strategies. The Xiangyang case is also notable for its cross-regional connectivity, serving residents from both Shanghai and adjacent Kunshan in Jiangsu Province. The findings identify deficiencies in both the design and actual use of space, leading to recommendations for improvement.

The contributions of this study are twofold:

- Theoretical contribution: This research introduces the theory of polyvalence to systematically develop a flexibility evaluation framework for rural public cultural spaces. It addresses a critical gap in the current literature, which lacks systematic and quantitative methods for assessing multifunctional adaptability and usage flexibility in such contexts. The proposed framework offers a new perspective for understanding spatial potential and functional performance, while also extending the applicability of polyvalence theory to rural public cultural spaces.

- Practical contribution: This study applies quantitative indicators and computational methods to empirically evaluate the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center in Shanghai. The findings reveal typical issues such as uniform spatial structure, rigid functional allocation, and underutilized residual spaces. Based on these insights, the study proposes spatial optimization strategies that respond to the dynamic needs of rural residents. The results provide scientific support for the planning, design, and operation of not only the Xiangyang Villag project, but also similar rural public cultural spaces in surrounding areas.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 reviews the development of polyvalence theory, its core concepts, and its applications in spatial design. Section 3 details the proposed evaluation framework for spatial flexibility in rural public cultural spaces, including the specific indicator system and the computational methods. Section 4 presents the case study, including the research background, data collection methods, and analysis of evaluation results. Section 5 discusses spatial optimization strategies informed by the findings, addressing both overall and individual spatial flexibility, and reflecting on the strengths of the proposed framework. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions, reflecting on the study’s limitations, and outlining directions for future research.

2. Review of the Theoretical Development and Applications of Polyvalence Theory

In the early 20th century, Ferdinand de Saussure introduced linguistic structuralism, later extended by Claude Lévi-Strauss to structural anthropology, where he emphasized the relationship between collective forms and individual expression [21,22]. This structuralist thinking influenced architecture. After World War II, functionalism in architecture proved increasingly inadequate in addressing evolving social needs [23]. At the 1959 CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne) conference in Otterlo, a new generation of architects criticized rigid functionalist doctrines, advocating for socially responsive design. Between 1959 and 1967, Herman Hertzberger served as secretary of the editorial board of Forum’s journal, and this experience influenced his architectural thinking and laid the conceptual foundation for his theory of polyvalence [24].

Hertzberger’s polyvalence theory integrates theoretical perspectives from multiple disciplines. Drawing from linguistics, he adopts the concepts of “competence” and “performance” and applies them to architectural form and individual expression. Influenced by structuralism, he emphasizes the coherence and systemic nature of architecture [25]. The architectural principles of Aldo van Eyck—such as the holistic view, intermediary theory, and the concept of “appropriate scale”—also profoundly shaped Hertzberger’s theoretical framework. Additionally, Dutch cultural traditions and the Montessori method have contributed sociological and educational perspectives to the development of polyvalence theory [26].

The core principle of polyvalence theory can be summarized as follows: architecture should have the capacity to accommodate multiple modes of use and habitation, while maintaining its intrinsic characteristics. Hertzberger defines this capacity as “polyvalence”, referring to a spatial configuration that “without changing itself can be used for every purpose and which, with minimal flexibility, allows an optimal solution”, as cited by Merino del Río and Grijalba Bengoetxea [27]. Such a form not only adapts to functional variations but also encourages individual expression and interpretation. Specifically, this theory emphasizes the following key aspects:

- Architectural coherence and systemic organization, viewing architecture as a whole.

- The role of architecture in fostering individual expression.

- The social dimension of space, advocating that architecture should facilitate human interaction.

- The necessity for architecture to be adaptive and inclusive, capable of accommodating diverse uses.

A key distinction between polyvalence theory and traditional functionalist architecture lies in its ability to respond to unforeseen circumstances [28]. Hertzberger argues that space should possess the potential to stimulate individual expression and be characterized rather than neutral [25]. This character emerges from user needs, leading to variations in how different individuals utilize the same space.

Polyvalence theory has been applied to the design and analysis of various spatial typologies. Liu et al. [29] explored the strategies for sustainable renewal of rural public spaces from the perspective of spatial polyvalence. Through a case study of Zhujialin Village, they proposed three renewal strategies: boundary dissolution, flexible reservation, and functional integration. Ring explored the conceptual integration of polyvalence and adaptability, proposing the notion of polyvalent adaptation to address spatial and temporal uncertainties in the context of climate change [30]. He subsequently applied this theoretical framework to climate-resilient infrastructure and adaptive urban systems [31]. Drawing on case studies, including the Artificial Oases system in Saharan Africa, the Arctic Food Network in Nunavut, Canada, and the New Meadowlands project in New Jersey, the study demonstrates how strategically conceived spatial infrastructure can perform across temporal horizons—sustaining daily functions, providing emergency resilience, and supporting long-term urban adaptation. Sun et al. [32] investigated the polyvalence characteristics of farmhouse functional spaces in the Hexi Corridor region. Through field surveys, they found that local farmhouses exhibit gradual functional substitution, dynamic multi-functional integration, and spatial interface ambiguity due to factors such as the interweaving of living and production functions, climatic constraints, and the social division of labor. Although the aforementioned studies have widely applied polyvalence theory to the design and analysis of various architectural space types, they remain primarily focused on design strategies and specific project-level applications. Few have addressed the issue from a quantitative evaluation perspective by systematically constructing a framework to assess spatial flexibility. This gap has limited the broader application of polyvalence theory in evaluating spatial adaptability and functional potential. On the one hand, this study explores feasible pathways for applying polyvalence theory to the development of evaluation indicators, thereby extending its theoretical application within spatial assessment frameworks; on the other hand, it aims to provide a structured approach for systematically reviewing and planning the actual use of rural public cultural spaces, offering theoretical support for their planning, governance, and sustainable renewal.

Given the flexible and evolving ways in which rural residents use public cultural spaces—characterized by seasonal variation and context-specific needs—this study adopts Herman Hertzberger’s theory of polyvalence as the theoretical foundation for evaluating spatial flexibility. Unlike functionalist or typology-based approaches, which emphasize predefined uses and static spatial configurations, polyvalence theory highlights spatial openness, adaptability, and user participation. This perspective is particularly relevant to rural contexts, where residents’ needs often transcend rigid spatial definitions, and public cultural facilities are expected to accommodate diverse, dynamic, and evolving functions.

Compared to existing rural spatial evaluation models—such as Micek and Staszewska’s evaluation framework [17], Zheng et al.’s vitality analysis based on behavioral trajectories [18], and Fu and Hou’s scene theory-based typology [20]—polyvalence theory shifts the focus from spatial outcomes to spatial potential. It emphasizes the capacity of space to support multiple, coexisting, and temporally dynamic uses. This makes it especially suitable for evaluating the flexibility of rural public cultural spaces, which must respond to both institutional programming and community-driven adaptation. By applying this theoretical lens, the study proposes a spatial flexibility evaluation framework.

3. Framework for Evaluating the Flexibility of Rural Public Cultural Spaces

Based on Hertzberger’s polyvalence theory and contextualized with the specific conditions of Chinese rural public cultural spaces, this study develops a framework for evaluating spatial flexibility. The framework is structured around two core dimensions: competence and performance. The competence dimension examines the potential of rural public cultural spaces to accommodate diverse functions, while the performance dimension evaluates how these spaces facilitate villagers’ individual expression and social interaction in actual use.

3.1. Evaluation of the Competence of Rural Public Cultural Spaces

The competence of a space is evaluated through four key indicators: structural adaptability, spatial order, collectivity, and place-ness.

- Structural Adaptability. This indicator evaluates the flexibility of the foundational structural design, emphasizing modularity and adaptability. It examines the potential for structural units to be reconfigured, combined, or disassembled to accommodate diverse functions and evolving spatial demands. The modular design of the underlying structure serves as the spatial framework, ensuring long-term adaptability for future functional modifications and expansions.

- Spatial Order. This indicator evaluates the systematic and coherent relationships between the overall and individual components of rural public cultural spaces. It focuses on the coordination of spatial elements in terms of design language (e.g., form, material, and color) and functional alignment. Key considerations include the integration of exterior and interior environments, as well as the consistency between overall functional planning and localized functional areas. Establishing spatial order enhances the adaptability of rural public cultural spaces to localized changes, ensuring spatial resilience.

- Collectivity. This indicator evaluates the capacity of a space to support public functions. It is specifically reflected in the proportion of collective spaces and accessibility. Rural public cultural spaces should be designed with highly open and accessible collective areas to accommodate diverse uses by different groups at different times.

- Place-ness. This indicator evaluates the appropriate articulation of spatial characteristics, emphasizing that a space should possess distinct features and a clear identity, without overly restricting specific functions. Such flexibility allows rural residents to interpret and adapt the space according to their needs. A well-balanced design of place-ness encourages diversity and spontaneity in spatial use. Additionally, the historical memory and cultural symbolism embedded in the space strengthen residents’ sense of belonging, foster spontaneous use and community co-creation, and ultimately enhance the flexibility of spatial utilization.

3.2. Evaluation of the Performance of Rural Public Cultural Spaces

The performance of rural public cultural spaces is evaluated based on three key indicators: stimulation, public–private relationship, and in-between spaces.

- Stimulation. This indicator evaluates the capacity of rural public cultural spaces to stimulate spontaneous use by villagers. It is evaluated based on two key aspects: spatial function division (whether the space incorporates areas designated for villagers’ spontaneous use) and utilization of residual spaces (whether villagers can participate in the design and use of these spaces).

- Public–Private Relationship. This indicator evaluates the spatial configuration of publicness and privateness in design. It is examined on two levels: functional and formal. Functionally, it evaluates whether the spatial layout accommodates varying degrees of public and private use based on the actual needs of rural residents. Formally, it considers whether design elements—such as partition materials and enclosure strategies—effectively balance openness and privacy.

- In-Between Spaces. Hertzberger defines in-between spaces as transitional areas situated between public and private spaces, helping to mitigate rigid distinctions between the two. The evaluation of this indicator involves two key aspects. First, it evaluates whether appropriately designed buffer zones or transitional spaces exist between public and private areas. Second, it examines the functional adaptability of these spaces, allowing for expanded uses or spontaneous engagement by villagers. For instance, beyond serving as a buffer between public and private spaces, corridors may also support social interactions or serve as resting areas.

3.3. Formulation of the Flexibility Evaluation Framework

Based on the aforementioned indicators, corresponding quantitative methods were developed to formulate a flexibility evaluation framework for rural public cultural spaces, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Framework for evaluating the flexibility of rural public cultural spaces.

4. Case Application

To assess whether the proposed flexibility evaluation framework can provide new perspectives, insights, and guidance for the design and decision-making processes in the renewal of rural public cultural spaces, an empirical analysis is conducted using the Xiangyang Village Wojia Neighborhood Center in Jiading District, Shanghai, China, as a case study.

4.1. Background

Xiangyang Village is located at the northwest gateway of Shanghai, adjacent to Huaqiao Town in Jiangsu Province. It is bordered to the east, west, and south by the Shanghai International Automobile City and Huaqiao International Business City, with Jiabei Country Park to the north (as shown in Figure 1). The village covers an area of 2.12 square kilometers and consists of 10 village groups, with 333 households and a registered population of 1350. In 2016, Xiangyang Village began its participation in the Construction of Beautiful Villages program. The village was included in the first batch of Shanghai Rural Revitalization Demonstration Villages in 2018 and has received the “Shanghai Civilized Village” title for five consecutive years.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Xiangyang Village (illustrated by the authors). In the inset map on the right, Chinese place names are shown alongside their English equivalents for clarity and cross-linguistic reference.

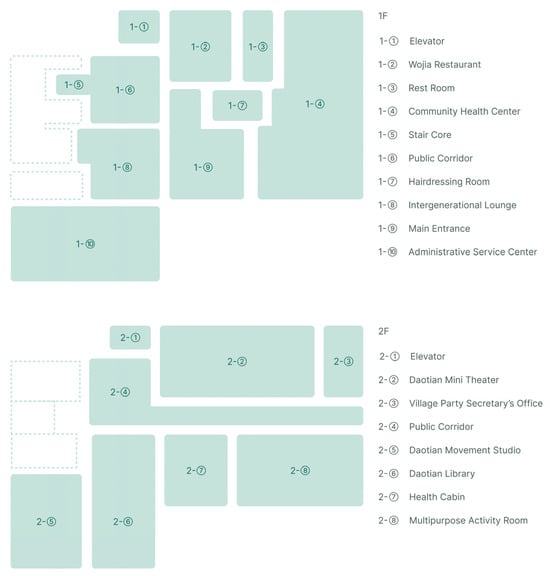

The Xiangyang Village Wojia Neighborhood Center building was completed in December 2022, with a total construction area of 1060 square meters. It includes various functional spaces, such as an administrative service center, a library, a small theater, and a community health center (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Xiangyang Village Wojia Neighborhood Center (photographed by the authors). In the upper subfigure, the Chinese text on the left side denotes the center’s name, which corresponds to the English translation: “Wojia Neighborhood Center and Party-Masses Service Center, Xiangyang Village, Anting Town”.

The selected case of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center is not an isolated or standalone project, but rather a representative example of the Wojia Neighborhood Center system-wide initiative led by the Jiading District Government in Shanghai. This government-led program adopts an integrated approach to planning, design, and operation, aiming to enhance grassroots governance and public service delivery through comprehensive lifecycle planning, full spatial coverage, and services tailored to all age groups [33]. The initiative was recognized as one of China’s 2024 National Exemplary Rural Public Service Cases (25 projects selected nationwide) and remains the only project from Shanghai to receive this distinction [34]. As of December 2024, Jiading District had completed 62 Wojia Neighborhood Centers, including 21 in rural villages. The program offers an innovative response to challenges in rural public service provision and spatial function allocation, providing valuable references for the development of rural public service systems and the improvement of rural living conditions [35]. As a concrete manifestation of this model, the Xiangyang Village case reflects—at least in part—the design, implementation, and operational logic of rural public cultural and service spaces in the Yangtze River Delta region, and thus carries significant research and demonstration value. Moreover, Xiangyang Village is located at the administrative boundary between Shanghai and Kunshan City in Jiangsu Province. Since its opening in early 2023, the neighborhood center has served not only local villagers but has also attracted residents from Huaqiao Town in Kunshan, fostering cross-regional community interaction and emotional connection [36].

4.2. Data Collection

To support the indicator-based evaluation of spatial flexibility, this study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining questionnaire surveys, semi-structured interviews, on-site measurements, and observational documentation, as follows: (1) The first round of semi-structured interviews explored user experience, spatial adaptability, activity types, and stakeholder roles. Administrators provided information on demographic characteristics, space utilization, activity planning, functional positioning, and governance mechanisms. Residents reflected on participation patterns, spatial preferences, satisfaction levels, and suggestions for improvement. These findings offer contextual insights into the use and management of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center from both institutional and user perspectives. (2) The questionnaire focused on rural residents’ hierarchical functional needs and satisfaction levels regarding public cultural spaces. Respondents were asked to rate the importance of specific spatial functions across five categories—cultural display and education (e.g., exhibition hall, reading room), community gathering and interaction (e.g., assembly hall, leisure areas), recreation and sports (e.g., dance studio, AR-enabled cultural experiences), commerce and information (e.g., local product markets, bulletin boards), and religious and cultural activities (e.g., festival venues, ceremonial spaces). Ratings were collected using a 5-point Likert scale to capture priority differences among functional elements and to inform space planning. (3) The second round of semi-structured interviews aimed to supplement or validate the information required for calculating the indicators listed in Table 1.

These empirical methods were implemented across three field visits. To enhance data reliability, the survey instruments were reviewed by professionals; interviews were conducted with diverse stakeholders (including village officials, elderly residents, and neighborhood center staff); and triangulation was achieved through the integration of observational records and expert validation throughout the evaluation process.

The first field survey was conducted on 4 February 2024. The first round of semi-structured interviews was conducted (see Table A1 for the interview guide). The interviewees included a deputy secretary of the village party branch (responsible for organization and publicity) and a permanent resident (approximately 80 years old). Detailed interview data are presented in Table A1. Additionally, the study incorporated spatial design proposals provided by the neighborhood center, along with on-site photographic documentation, to systematically document the spatial layout and interior configuration. These data serve as the basis for subsequent evaluation indicator calculations and spatial analysis.

The second field survey was conducted on 15 July 2024. A structured questionnaire was administered to 19 rural residents. Comprehensive information on the questionnaire design, respondent demographics, and survey data is provided in Table A2.

The third field survey, conducted on 21 September 2024, built upon the previous two surveys to systematically collect data corresponding to the indicators outlined in Table 1. First, a laser rangefinder was used to manually measure the length and width of each space across both floors of the neighborhood center (as shown in Figure 3). Second, the second round of semi-structured interviews was conducted with four participants, including two local residents and two neighborhood center staff members. In addition, two professional environmental designers participated in reviewing and confirming the values assigned to selected indicators through expert discussion.

Figure 3.

Layout of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (drawn by the authors).

To illustrate the quantitative evaluation process outlined in Table 1, Room 1-8 of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (depicted in Figure 4) serves as a representative example. This room is a composite space comprising the Wojia Lounge, which facilitates everyday communication, and the Growth Corner, designed for children. (1) Modular Level (F1.1.1): As shown in the upper section of Figure 3, the first floor contains ten functionally usable spaces. Among these, Rooms 1-6, 1-2, and 1-9 share a similar structural module as that used in Room 1-8. Consequently, the value of F1.1.1 for Room 1-8 is 0.400 (4/10). (2) Structural Support (F1.1.2): This indicator assesses how well the spatial structure meets the functional needs of rural residents, based on the five functional categories listed in Table A2, i.e., Cultural Display and Education, Community Gathering and Social Interaction, Recreation and Sports, Commerce and Information, and Religious and Cultural Activities. Given that the structure of Room 1-8 supports all five functions, F1.1.2 is scored at 1.000 (5/5). (3) Functional Consistency (F1.2.1): The adjacent spaces to Room 1-8 are Rooms 1-10, 1-9, and 1-6. Room 1-10 is fully enclosed, with no direct interaction, while Rooms 1-9 and 1-6 are transitional spaces with no fixed functions, posing no conflict with the function of Room 1-8. Thus, is rated 1.000. Additionally, the neighborhood center’s overall mission is to provide “all-age, community-serving” spaces (as detailed in Section 4.1). Spaces conflicting with this mission have reduced scores for ; for instance, Room 1-1 lacks inclusive design features for older or disabled individuals, and is rated 0.500. In contrast, Room 1-8 aligns with the center’s mission, earning a score of 1.000. Therefore, F1.2.1 is calculated to be 1.000. (4) Formal Consistency (F1.2.2): As depicted in Figure 2, the building features a modern design style with gray and brown tones. Room 1-8 maintains formal consistency with this aesthetic, resulting in a score of 1.000 for F1.2.2. (5) Collective Space (F1.3.1): Room 1-8 has a semi-open layout, with furnishings and spatial organization designed to support social interaction and group activities. Therefore, F1.3.1 is scored at 1.000. (6) Accessibility of Collective Space (F1.3.2): As Room 1-8 is a collective space, it is directly accessible and receives a score of 1.000. For illustrative purposes, Room 1-1 (elevator) is also evaluated. Room 1-1 does not support collective use; the nearest collective space is Room 1-2 (Wojia Restaurant), which is 1.875 m away. Assuming an average walking speed of 1 m/s, the minimum value of is 1.875. Given that is 10 (the longest distance from Room 2-3 to Room 2-8) and is 0 (collective rooms themselves), the accessibility score for Room 1-1 is 0.813. (7) Place-Making (F1.4.1): Room 1-8 avoids rigid functional zoning, offering flexible furniture for intergenerational interaction. Compared to standardized spaces like Rooms 1-10 or 1-4, Room 1-8 enhances spatial openness and cross-generational engagement, thus receiving a score of 1.000. (8) Cultural Memory (F1.4.2): Room 1-8 includes a wall-mounted shelving unit displaying everyday items and cultural ornaments. Chinese knots and themed posters on the walls represent elements of Chinese cultural identity. However, the space lacks representation of local rural memory, resulting in a score of 0.500. (9) Spontaneity of Individual Spaces (F2.1.1): Room 1-8 is semi-open and accessible to residents, earning a score of 1.000. (10) Spontaneity of Residual Spaces (F2.1.2): Although residual spaces exist within Room 1-8, they lack shelving or interactive features for community use. Thus, F2.1.2 is scored at 0.000. (11) Functional Aspects of Public–Private Relationship (F2.2.1): Room 1-8 is a public collective space and does not support private functions, resulting in a score of 0.000. (12) Formal Aspects of Public–Private Relationship (F2.2.2): The space lacks flexible partitions or movable enclosures to facilitate transitions between public and private uses, resulting in a score of 0.000. (13) Existence of Buffer Spaces (F2.3.1): Room 1-8 is connected to Rooms 1-6 and 1-9 through semi-open designs, serving as transitional zones. Thus, F2.3.1 is rated 1.000. (14) Functionality of Buffer Spaces (F2.3.2): The buffer spaces between Room 1-8 and adjacent rooms contain plants, bulletin boards, and shelving units, supporting informal use and access to community information, resulting in a score of 1.000.

Figure 4.

Image of Room 1-8: Intergenerational Lounge (photographed by the authors). On the central wall, the Chinese texts convey the following: the upper right displays the room name “Neighborhood Reception Lounge”; the lower right presents a slogan, “Co-build a Beautiful Xiangyang, Share a Happy Homeland”; and the left side features the “Xiangyang Covenant,” which advocates seven core values, including family harmony, respect for the elderly, and care for the young.

4.3. Results

The flexibility evaluation results for individual spaces of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center are presented in Table 2. The flexibility evaluation of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center is calculated based on the following formula:

where n represents the total number of individual spaces, denotes the area of the -th space, and represents the total area of individual spaces. The calculation results are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Flexibility for individual spaces of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center.

Table 3.

Flexibility for the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center.

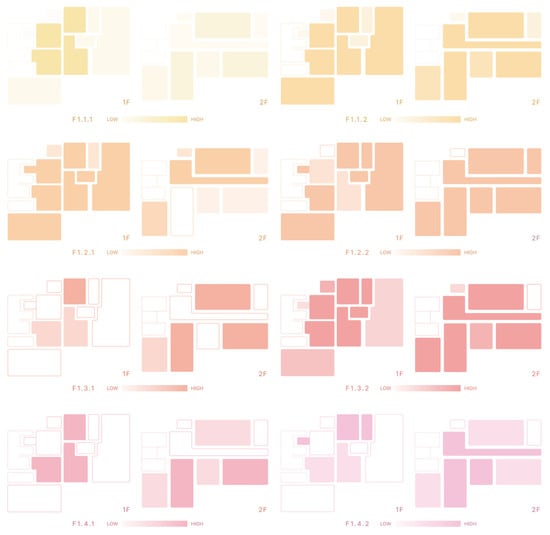

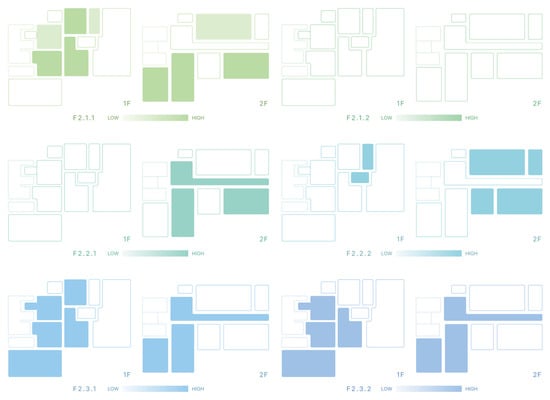

First, the layout of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (as shown in Figure 3) was used as the base map, and the scores for each evaluation dimension were visualized to facilitate a detailed analysis. The competence (F1) evaluation consists of four aspects, as illustrated in Figure 5:

Figure 5.

Competence evaluation results for the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (illustrated by the authors).

- Structural Adaptability (F1.1). The modular level (F1.1.1) of the neighborhood center scored 0.289, which is below the average threshold of 0.500, indicating a low level of modularity among interior spaces. Among the first-floor spaces, Rooms 1-2, 1-6, 1-8, and 1-9 exhibit structural similarity, allowing for functional transformation; however, they account for only 40% (4/10) of the total first-floor spaces. The structural support (F1.1.2) score is 0.898 (above 0.75), suggesting that the current spatial structure effectively supports the existing cultural activities and functional needs of rural multiple stakeholders. Specifically, ten spaces (1-2, 1-4, 1-6, 1-8, 1-9, 1-10, 2-2, 2-4, 2-6, and 2-8) achieved the highest score of 1.000, meaning that 55.6% (10/18) of the spaces are well-suited for community cultural activities.

- Spatial Order (F1.2). The functional consistency (F1.2.1) score of 0.743 indicates that most spaces maintain functional alignment with their adjacent spaces and the overall functional planning of the neighborhood center. On the first floor, eight spaces (80%, 8/10) exhibit full functional consistency, while on the second floor, three spaces (37.5%, 3/8) fully align with the functional consistency. Regarding formal consistency (F1.2.2), the overall score is 0.917. Except for Rooms 1-1, 1-6, 1-9, and 2-1, all other spaces achieved the highest score of 1.000, indicating a strong formal design consistency across the neighborhood center.

- Collectivity (F1.3). The collective space index (F1.3.1) scored 0.459, indicating that some spaces can support collective activities, though not comprehensively. On the first floor, only one space (1-2) fully supports collective activities, while two spaces (1-8 and 1-9) partially support them. On the second floor, three spaces (2-2, 2-6, and 2-8) fully support collective activities, with one space (2-5) partially supporting them. This distribution highlights differences in collective space allocation between floors. Regarding accessibility of collective spaces (F1.3.2), the overall score is 0.877, indicating that most individual spaces have relatively good accessibility to collective spaces. However, Rooms 2-3, 1-5, and 2-1 have low accessibility scores (<0.4), suggesting limited connectivity to collective areas.

- Place-ness (F1.4). For place-making (F1.4.1), the overall score of 0.491 (close to 0.5) suggests a moderate level of spatial identity and place-based quality. Comparatively, Rooms 1-2, 1-8, 1-9, 2-6, and 2-8 exhibit a stronger sense of place, each scoring 1.000. The cultural memory dimension (F1.4.2) has a score of 0.520, indicating that the cultural expression within the neighborhood center is relatively limited. Higher scores (1.000) were observed in Rooms 1-2, 1-3, and 1-5 on the first floor, and 2-4, 2-6, and 2-7 on the second floor, suggesting that these spaces effectively incorporate rural cultural elements in their interior design. In contrast, Rooms 1-1, 1-4, 1-6, 1-7, 1-10, 2-1, and 2-3 scored 0.000, indicating weak cultural integration and expression.

The performance (F2) evaluation consists of three aspects, as illustrated in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Performance evaluation results for the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (illustrated by the authors).

- Stimulation (F2.1). The spontaneity of individual spaces (F2.1.1) has an overall score of 0.518, indicating that while the spaces allow for a certain degree of spontaneous uses by residents, some areas remain restricted. Specifically, Rooms 1-2, 1-8, 1-9, 2-5, 2-6, and 2-8 achieved a maximum score of 1.000, reflecting a high level of autonomy in resident usage. In contrast, the spontaneity of residual spaces (F2.1.2) scored extremely low (0.000), suggesting that in the current layout of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center, either residual spaces were not considered in the design, or they have not been made accessible for spontaneous use by rural residents.

- Public–Private Relationship (F2.2). The functional aspect of public–private transition (F2.2.1) has an overall score of 0.295, indicating that the transition between public and private functions is poorly supported across most spaces. Among them, only Rooms 2-4, 2-6, and 2-8 fully support public–private conversion, with a score of 1.000. Similarly, the formal aspect of public–private transition (F2.2.2) exhibits an overall score of 0.355, reflecting that the interior design of most spaces does not effectively support the transition between public and private functions. Notably, Rooms 1-3, 1-7, 2-2, 2-3, 2-7, and 2-8 scored 1.000, indicating a higher degree of public–private adaptability in their interior design.

- In-Between Spaces (F2.3). The existence of buffer spaces (F2.3.1) has an overall score of 0.530, suggesting that while some transitional buffer zones have been incorporated into the neighborhood center, their overall prevalence remains limited. The functionality of buffer spaces (F2.3.2) scored 0.482, which is slightly lower than the existence score of 0.530, indicating that some buffer spaces remain underutilized in practice.

Next, an analysis was conducted based on the flexibility scores of individual spaces.

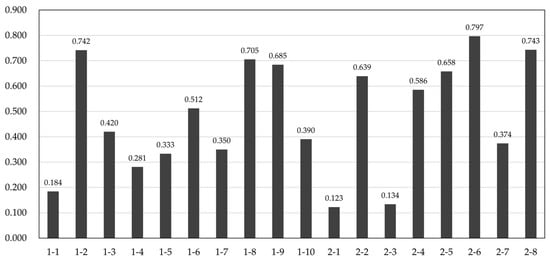

To determine the relative importance of each evaluation indicator, this study employed the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). A structured pairwise comparison questionnaire was developed based on the standard 9-point scale and completed by six domain experts, including two senior design researchers, two practitioners experienced in public space renewal projects, and two grassroots-level civil servants. For each pairwise comparison, individual responses were converted into numerical values and aggregated using the geometric mean method (GMM) to construct group-level judgment matrices at all hierarchical levels.

The relative weights of indicators were then calculated following standard AHP procedures: each aggregated matrix was column-normalized, and the priority vector was derived by averaging the rows. The consistency of expert judgments was evaluated using the consistency ratio (CR). All CR values were below 0.05, indicating a high degree of internal consistency across the matrices. The complete set of weights is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Weight distribution of evaluation indicators, based on AHP.

Based on the weights presented in Table 4, weighted average scores of the 14 indicators were calculated for each spatial unit, and the results are visualized in the form of a bar chart, as shown in Figure 7. Among all spaces, Room 2-6 achieved the highest average flexibility score (0.797), followed by Room 2-8 (0.743), Room 1-2 (0.742), and Room 1-8 (0.705). Conversely, Room 2-1 received the lowest evaluation (0.123), followed by Room 2-3 (0.134). Room 1-1 ranked third lowest, with a score of 0.184.

Figure 7.

Weighted average flexibility scores of individual spaces in the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (illustrated by the authors).

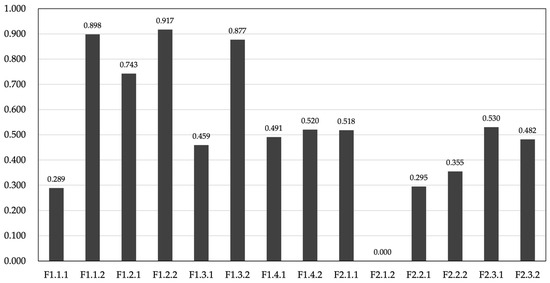

Finally, regarding overall spatial flexibility (as shown in Figure 8), F1.2.2 received the highest score of 0.917, followed by F1.1.2 (0.898), F1.3.1 (0.877), and F1.2.1 (0.743). The dimensions with the lowest scores include F2.1.2 (0.000), F1.1.1 (0.289), F2.2.1 (0.295), and F2.2.2 (0.355), all of which are below 0.4. Meanwhile, F1.3.1 (0.459), F2.3.2 (0.482), F1.4.1 (0.491), F2.1.1 (0.518), F1.4.2 (0.520), and F2.3.1 (0.530) demonstrate moderate performance, with scores ranging between 0.45 and 0.55.

Figure 8.

Overall flexibility scores of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center (illustrated by the authors).

5. Discussion

Based on the previous analysis results, this section discusses the spatial flexibility evaluation and optimization strategies of the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center, focusing on two key aspects: optimization for overall spatial flexibility and strategies for improving the flexibility of individual spaces.

5.1. Strategies for Enhancing the Overall Spatial Flexibility of the Neighborhood Center

According to the evaluation results shown in Figure 8, the two most pressing issues in the Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center that require urgent improvement are the spontaneous utilization of residual spaces (F2.1.2 = 0.000) and the flexible transition between public and private spaces (F2.2.1 = 0.295; F2.2.2 = 0.355).

- Optimization of Residual Space Utilization. Survey findings and evaluation results indicate that residual spaces within the neighborhood center are insufficiently designed, leading to underutilization or inefficient use. In rural public cultural spaces, however, such residual areas hold significant potential as sites for participatory design, everyday appropriation, and localized maintenance. Drawing on the theoretical perspectives of temporary urbanism and everyday urbanism, Zhou et al. [37] underscore the significance of flexible, small-scale, and user-oriented interventions in reactivating residual spaces. They argue that transforming “temporary” spatial interventions into “everyday” practices allows for the integration of adaptive renewal strategies as part of daily life, thereby supporting the construction of a sustainable spatial order. Residual spaces can be strategically repurposed into multifunctional micro-sites such as cultural display corners that showcase rural heritage, social nodes that foster community engagement, or creative platforms that support spontaneous expression. For example, in the case of the median gardens in the Wallingford and Capitol Hill neighborhoods of Seattle, USA, residents proactively cultivate and plant garden strips. These greening efforts enhance social interaction, strengthen residents’ sense of belonging, enable personal expression, and reinforce neighborhood cohesion [38]. In the Cat’s Sky City concept bookstore in Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China, a residual space was creatively adapted into a Mail to Future corner—a participatory micro-space that invites users to express future aspirations (see Figure 9). Thus, effectively utilizing residual spaces requires transforming them into emotionally engaging and socially interactive environments that contribute to the construction of local identity and collective participation. In addition, according to the study by Eissa et al. [39], the design and implementation of interventions in residual spaces should be informed by a comprehensive understanding of the interrelationships among their physical, social, and mental dimensions, as well as the dynamic evolution of these dimensions. Such an approach enables planners and designers to emulate the adaptive qualities of spaces organically shaped through informal appropriation processes. This approach can also be integrated with the principles of co-design in design studies, which emphasize the sharing of knowledge about both the design process and content among actors from diverse disciplinary backgrounds [40].

Figure 9. The Mail to Future corner in the Cat’s Sky City concept bookstore, Xuzhou City (photographed by the authors). In the left subfigure, the Chinese text above the entrance denotes the name of the bookstore, “Cat’s Sky City.” In the right subfigure, the vertical row of Chinese characters on the right indicates the months from January to July. The wall text on the left introduces the concept of “Mail to Future,” a participatory installation inviting users to write postcards scheduled for future delivery. Participants can select a delivery time and write to themselves or others. The text also provides details on estimated delivery times and pricing.

Figure 9. The Mail to Future corner in the Cat’s Sky City concept bookstore, Xuzhou City (photographed by the authors). In the left subfigure, the Chinese text above the entrance denotes the name of the bookstore, “Cat’s Sky City.” In the right subfigure, the vertical row of Chinese characters on the right indicates the months from January to July. The wall text on the left introduces the concept of “Mail to Future,” a participatory installation inviting users to write postcards scheduled for future delivery. Participants can select a delivery time and write to themselves or others. The text also provides details on estimated delivery times and pricing. - Flexible Transition between Public and Private Spaces. The current spatial configuration of the neighborhood center rigidly separates public and private spaces, with corresponding interior design elements reinforcing this division. However, in rural public cultural spaces, such an architectural approach of strictly delineating public and private spaces may not be suitable for highly flexible spatial demands. As previously discussed, rural public cultural spaces must not only cater to the diverse needs of rural stakeholders but also adapt to the dynamic evolution of rural industries. Drawing on Appleton’s prospect-refuge theory [41], which highlights the human preference for environments that balance openness (prospect) with shelter (refuge), we argue that flexible transitions between public and private spaces are essential for promoting spatial comfort, perceived safety, and behavioral adaptability. From a design perspective, adaptive public–private spatial strategies are recommended, including: (1) Flexible partitions that can be adjusted to modulate spatial openness or enclosure based on usage needs. For example, Raydoor, a New York-based interior partition company, emphasizes that “artful room division can help bring different areas of the space to life by facilitating both privacy and community” [42]. Their large-scale sliding wall systems are designed to blend seamlessly into the environment when retracted and to serve as both functional dividers and visual focal points when deployed (available online: https://vimeo.com/831702343, accessed on 22 May 2025). (2) Visual guidance techniques to subtly define spatial boundaries. For instance, the IBM workplace uses glass curtain walls in enclosed offices, meeting rooms, and collaborative zones to enhance spatial transparency and extend lines of sight, thereby improving user experience [43]. (3) Modular, movable furniture that enables rapid reconfiguration and repurposing of spaces. The Steelcase Flex Personal Spaces collection supports a broad range of spatial configurations and flexible transitions between work environments, with varying degrees of openness. This is achieved through two key elements—desks (offered in 90- and 120-degree configurations) and privacy wraps [44]. Furthermore, while structural retrofitting of the neighborhood center may be constrained due to its existing physical framework, digital service interventions can provide an alternative pathway for enhancing functional adaptability. Embedding modular digital service units into various spatial nodes can enable functional reconfiguration without altering the physical architecture, thereby mitigating structural rigidity and expanding spatial flexibility.

5.2. Strategies for Improving the Flexibility of Individual Spaces

Further analysis reveals that low-flexibility individual spaces typically exhibit two main characteristics: small spatial areas or rigid functional definitions. To address these issues, the following optimization strategies are proposed:

- Elevator spaces (Rooms 1-1 and 2-1) should transition from a basic infrastructure to an inclusive and interactive site. Currently, the elevator space in the neighborhood center serves only as a vertical transportation facility, without sufficient consideration of user experience and cultural value. Its flexibility can be enhanced through two key strategies: First, enhancing inclusivity by improving accessibility for individuals with mobility impairments, visual impairments, and elderly users by optimizing universal design features and wayfinding systems. In addition, the implementation of age-appropriate renovations of facilities such as elevators should realize shared benefits from the perspective of stakeholders [45]. Second, strengthening cultural and social engagement by utilizing elevator spaces for cultural-themed designs, aesthetic enhancements, and interactive installations, such as community display walls or participatory feedback panels, to enrich rural residents’ engagement within rural cultural spaces. As Parker et al. [46] point out, areas where people naturally pause or wait—such as near cafeteria lines or elevators—are effective locations for deploying public interactive displays (PIDs), as they are prone to opportunistic interactions. Such PIDs can foster increased social engagement within communities, including spontaneous discussions and peer-to-peer assistance.

- The hairdressing room (Room 1-7) should expand its multifunctional uses. At present, the hairdressing room is predominantly used for haircuts at specific times, remaining vacant for extended periods due to its rigid function and space constraints imposed by barbering equipment. However, given its location between the Wojia restaurant and the rest room, it holds significant potential for functional integration and flexible utilization. A feasible approach is to adopt a hybrid function model, drawing inspiration from the “barbershop + bar” concept seen in Shiquan Street, Gusu District, Suzhou City (Figure 10). This strategy resonates with hybrid-adaptive reuse [47], which emphasizes the coexistence of temporal and functional layers within a single space. By converting a service-oriented space into a socially engaging environment during off-hours, and by embedding modular and symbolic design elements, the intervention not only expands spatial utility but also cultivates cultural continuity and community belonging. Potential transformations include (1) repurposing the space into a community tea lounge during non-service hours, (2) leveraging the mirrored surfaces to create a rural handicraft display area or interactive photography space, and (3) utilizing reconfigurable furniture to enhance spatial adaptability and maximize utilization rates.

Figure 10. A “barbershop + bar” hybrid concept on Shiquan Street, Gusu District, Suzhou City (photographed by the authors).

Figure 10. A “barbershop + bar” hybrid concept on Shiquan Street, Gusu District, Suzhou City (photographed by the authors). - The village party secretary’s office (Room 2-3) should break boundaries and enhance openness. In the traditional rural governance system, the village party secretary’s office is typically a closed administrative workspace. However, field research reveals that Xiangyang Village hosts a Party–Masses Service Center at a separate site, which serves to facilitate daily governance and the delivery of public services at the village level. Therefore, this space should transition towards openness, multifunctionality, and shared use. For example, rural coworking represents a noteworthy direction in spatial utilization. In Europe, rural coworking initiatives have received funding support from regional development agencies, and they are recognized for their potential to retain—and even attract—talent, while also strengthening local collaborative networks [48]. Bosworth et al. [49] argue that rural coworking spaces can serve as remote network bridges connecting urban centers and enterprises, while also integrating rural economies into emerging networked systems. Furthermore, they emphasize that rural coworking spaces should enhance their place-based distinctiveness by providing services to more marginalized groups, and by ensuring the provision of essential facilities and network brokerage demanded by rural co-workers. Possible strategies include (1) adopting a flat office model, similar to co-working spaces in tech enterprises, to increase spatial flexibility; (2) incorporating adjustable work zones to accommodate administrative tasks, community meetings, and resident discussions; and (3) redesigning the office as a rural innovation hub, fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange.

- The community health center (Room 1-4) should strengthen functional integration with the neighborhood center. Currently, the community health center operates independently from the neighborhood center, adhering to a conventional community hospital model. Despite being housed in the neighborhood center, the community health center remains functionally and spatially isolated with the neighborhood center (even having separate entrances), lacking effective interaction. However, as a key rural healthcare and wellness facility, the health center should extend beyond medical services to integrate more community-based health initiatives, forming a stronger synergy with the neighborhood center. Through a systematic review, Haldane et al. [50] found that community involvement contributes positively to health, particularly when supported by strong organizational and community processes. Proposed enhancements include (1) expanding community health services, such as health lectures, wellness workshops, and physical activity programs; (2) designing open-access health interaction zones to promote preventive care and wellness awareness; and (3) redefining spatial connectivity by relocating or reconfiguring non-essential enclosed spaces, thereby strengthening integration with the neighborhood center and reducing spatial fragmentation.

5.3. Reflections on the Proposed Evaluation Framework in Comparison with Existing Approaches to Rural Public Cultural Space Assessment

A comparative review of existing evaluation frameworks for rural public cultural spaces highlights the unique contributions of this study. Fu and Hou [20], drawing on scene theory, proposed an analytical framework consisting of three primary dimensions—physical space, activity space, and institutional space—comprising fifteen secondary dimensions. Among these, the “physical space” category directly relates to spatial design and use, encompassing space type, facilities and equipment, spatial distance, service coverage, and pedestrian flow. Micek and Staszewska [17] proposed a semantic differential method-based evaluation system consisting of eight primary dimensions (functionality, practicality, reliability, durability, safety, legibility, aesthetics, and sensitivity) and 40 subdimensions to qualitatively assess 63 urban and 22 rural public spaces in Poland. Kang [51] developed a satisfaction index model for neighborhood cultural service facilities in Jiading District, Shanghai, with variables related to facility construction, operational management, and overall satisfaction. Meng et al. [52] proposed a quantitative evaluation framework to assess the quality of public spaces in traditional villages by integrating panoramic imagery with deep learning techniques. Using four national-level traditional villages in the Fangshan District, Beijing, as case studies, they extracted spatial features across natural, artificial, spatial, and cultural dimensions. They applied AHP and CRITIC (criteria importance through intercriteria correlation) to determine indicator weights, and employed the TOPSIS (techniques for order preference by similarity to an ideal solution) method to generate quality scores. Qin [53], using a case study in Ankang City, constructed an evaluation system for rural community public cultural service quality, with spatial design-related indicators including hygiene, infrastructure completeness, equipment maintenance, and nighttime lighting availability. Li et al. [54] proposed a sustainability evaluation framework for rural public spaces based on POI (point of interest) data and landscape preference surveys, applying the VEISD (village evaluation indicators for sustainable development) entropy model within a life circle spatial structure. Using the Anyi village cluster in Nanchang as a case study, they demonstrated how explicit–implicit space interactions influence spatial evolution and validated their method through the spatial adjustment of key nodes such as Luotian Village’s Ancient Camphor Tree Square.

In conjunction with the case study presented in this paper, the strengths and unique contributions of the proposed framework can be further clarified at the structural level.

(1) In terms of evaluation granularity, prior frameworks primarily adopt macro- or meso-level perspectives, typically treating the public cultural space as the fundamental unit of analysis. They often overlook a detailed evaluation of internal functional divisions and constituent spatial elements. The proposed framework addresses this gap by conducting fine-grained evaluations at the micro-scale, focusing on spatial subdivisions and architectural components within public cultural facilities.

(2) In terms of evaluative focus, although many studies emphasize the importance of user participation, perceived accessibility, and multifunctional use, few explore how spatial design can effectively support flexibility and adaptability. This study contributes by establishing a systematic framework for assessing spatial flexibility in rural public cultural spaces.

Furthermore, this framework holds theoretical and practical relevance for current practices in rural land planning and grassroots governance in China. At the planning level, it provides an evaluative mechanism to support village-level land use planning and spatial resource allocation. Under the national Rural Revitalization Strategy, optimizing the configuration and use of public cultural facilities (e.g., village administrative centers, cultural halls, rural theaters) has become a critical component of effective land management. High vacancy rates and low utilization of such facilities restrict the efficiency of rural land use and compromise public service delivery.

From a governance perspective, the demand for flexibility in rural public cultural spaces is rooted in the temporal rhythms, social interaction patterns, and governance logics unique to Chinese rural society. Rural residents exhibit dynamic, seasonal, and event-driven spatial behaviors. For example, activities differ significantly between farming and non-farming seasons, and cultural expectations associated with festivals and life events (e.g., weddings and funerals) further diversify spatial needs. These contextual dynamics require that spatial design and functional programming offer high levels of adaptability and responsiveness.

Additionally, rural social interaction in China is often structured around “renyuan” (personal ties) and “diyuan” (local kinship ties), reinforcing the importance of cultural spaces as emotional and social anchors. Flexible public cultural spaces help foster community interaction, collective memory, and shared identity, contributing to stronger social cohesion. At the same time, rural governance systems face constraints in regards to resource availability and administrative capacity. Spatial flexibility can enhance the utilization efficiency of existing infrastructure, alleviating mismatches between supply and demand.

In summary, the spatial flexibility evaluation framework proposed in this study not only responds to the policy imperatives of precision land allocation and high-quality rural public service provision but also aligns with the socio-cultural fabric and governance realities of rural China. It offers both scientific support for grassroots decision making in spatial planning and facility upgrades, along with methodological guidance for improving rural land-use efficiency and innovating rural governance practices.

6. Conclusions

The evaluation and design of rural public cultural spaces are often modeled after the form and functional standards of urban public cultural spaces, adopting a top-down planning and allocation approach. However, this method fails to align with the localized and dynamic needs of rural residents, leading to a discrepancy between spatial design and actual usage patterns. This study proposes a flexibility evaluation framework for rural public cultural spaces, aiming to assess the adaptability of these spaces under different usage scenarios and their capacity to stimulate personal expression and social interaction among rural residents. Using the Shanghai Xiangyang Village Neighborhood Center as a case study, this study critically reflects on design strategies for rural public cultural spaces and proposes the following recommendations. First, it proposes mitigating rigid functional zoning. Particularly for infrastructure-related spaces, the design process should fully consider the actual needs and usage patterns of rural residents. Through multi-functional and adaptive space utilization, greater spatial inclusivity and adaptability can be achieved. Second, this research suggests enhancing spatial interactivity through innovative design. Incorporating innovative elements in both spatial design and operational management can increase opportunities for resident–space interaction, facilitate social engagement among rural residents, and encourage participatory involvement in micro-renovations and the operational management of public cultural spaces. This participatory approach not only improves space utilization efficiency but also strengthens residents’ sense of community belonging.

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations remain. First, this study presents a preliminary empirical validation based on a single, representative case of a rural public cultural space. While this case offers initial support for the applicability of the proposed evaluation framework, future research will broaden the empirical scope by examining a more diverse set of rural public cultural spaces across cities in the Yangtze River Delta region, incorporating variations in geographic, social, and functional contexts. Cross-case comparative analysis and practical implementation feedback will be used to further test and refine the framework’s generalizability and robustness. As emphasized in Ref. [55], the evaluation of community service facilities constitutes a complex systematic challenge that spans multiple scales, integrates interdisciplinary knowledge, and involves a wide range of stakeholder interests. Accordingly, future work will also engage a broader range of stakeholders—including experts in urban–rural planning, architectural design, and rural governance, as well as space managers and users—to collaboratively optimize the framework. This participatory process aims to strengthen its practical relevance and policy utility. Second, this study faced challenges in data collection and the potential for AI-driven evaluation. Due to the fragmented nature of rural public cultural space data, the current study relies, to some extent, on the subjective judgment of researchers for specific indicators. As government-led standardized data collection practices for rural public cultural spaces advance, alongside the rapid development of image and text processing technologies, future studies should explore intelligent computational methods for evaluating the proposed flexibility framework. For example, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can be employed to perform fine-grained analyses of interior design images of rural public cultural spaces, extracting features related to spatial layout, functional utilization, and other key evaluation criteria. Large language models (LLMs) can be leveraged to conduct natural dialogues with rural residents via AI agents, uncovering latent needs, usage patterns, and satisfaction levels regarding public cultural spaces. By integrating intelligent data analytics, the proposed flexibility evaluation system can be further refined to enhance objectivity and scalability, ultimately providing scientific support for rural cultural spatial planning, architectural design, and policy making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., H.G. and M.H.; methodology, C.L., H.G. and M.H.; validation, H.G. and M.H.; formal analysis, H.G. and M.H.; investigation, H.G.; resources, C.L.; data curation, H.G. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., H.G. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, C.L., H.G. and M.H.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52308032.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CIAM | Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne |

| AHP | analytic hierarchy process |

| GMM | geometric mean method |

| CR | consistency ratio |

| PIDs | public interactive displays |

| CRITIC | criteria importance through intercriteria correlation |

| TOPSIS | techniques for order preference by similarity to an ideal solution |

| POI | point of interest |

| VEISD | village evaluation indicators for sustainable development |

| CNNs | convolutional neural networks |

| LLMs | large language models |

| NGOs | non-governmental organizations |

| ECADI | East China Architectural Design and Research Institute |

| AR | augmented reality |

| ICH | intangible cultural heritage |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

The semi-structured interview guide and interview data from the first field survey are presented in Table A1.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide and data summary of the first field survey.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide and data summary of the first field survey.

| Type | Interviewee | Questions/Data |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-Structured Interview Guide | Rural Administrators | Q1: Please describe the demographic structure of the village, including age distribution, education levels, and primary sources of livelihood. Q2: What types of public cultural activities are currently organized in the village? Which spaces are commonly used for these activities? Q3: What is the intended role or functional positioning of rural public cultural spaces? Q4: Who are the key stakeholders involved in the planning, management, and use of rural public cultural spaces? Q5: How satisfied are villagers with the current configuration and operation of public cultural spaces? |

| Village Residents | Q1: Please provide basic personal information, such as age, occupation, household composition, and leisure preferences. Q2: How frequently do you participate in public cultural activities? What types of activities do you prefer? Q3: In which spaces do you typically engage in cultural activities? How frequently do you use each space? Q4: Are you satisfied with the current types and characteristics of available cultural activities and spaces? What improvements or additions would you like to see? | |

| Semi-Structured Interview Data | Deputy Secretary of the Village Party Branch | 1. Demographic Structure and Livelihoods: The village population is primarily composed of older adults, with most women over the age of 50 and men over 60. Educational attainment is mainly at the junior high school or junior college level. Primary sources of income include pensions and part-time employment such as security and cleaning work. Some are re-employed by their previous employers. 2. Types and Sources of Public Cultural Activities: Core activities include weekly film screenings, square dance rehearsals, and weekly handicraft workshops. Resources are secured through collaborations with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), hospitals, and adult education institutions. Government-assigned activities are relatively infrequent, occurring three or four times per year. 3. Publicity and Feedback Mechanisms: Activities are primarily communicated through WeChat groups and informal word-of-mouth. Feedback is gathered via daily interactions, monthly community discussions (each involving representatives from one of the village’s ten residential groups), and direct phone calls from residents. 4. Cultural Activities Planning Process: Activities are co-developed with partner organizations through annual or mid-year coordination. The village provides venues, while partners deliver services. Timing and frequency are mutually agreed upon and adjusted based on continuous feedback. 5. Space Utilization and Adaptability: The Wojia Neighborhood Center functions as the main venue, incorporating spaces such as a dance studio, reading room, and small theater. 6. Resident Participation and Co-Creation: Villagers independently organize cultural groups such as dance teams and Chinese national music ensembles. During the neighborhood center’s design phase, villagers were consulted regarding specific spatial needs (e.g., installation of dance poles, mahjong tables, traditional hairdressing stations). 7. Informal Cultural Spaces and Local Heritage: A community cultural and recreational space was developed through a collaboration with a Taiwanese company. The site functions as a small public square. A 300-year-old ginkgo tree is designated as a historical landmark and marked with interpretive signage, although no formal cultural space has been developed around it. |

| Permanent Resident (elderly female, approximately 80 years old) | 1. Economic and Personal Background: Relies on pension income; resides with her son; previously recognized as a “March 8th Red-Banner Pacesetter.” 2. Activity Participation and Satisfaction: Participates occasionally, mainly in mahjong activities; rates the quality of public life 9 or 10 out of 10. Age-related impairments (e.g., vision, hearing) influence participation. 3. Spatial Use and Awareness: Engages in activities at the neighborhood center; learns about events via digital bulletin boards. Participated in activities such as sewing, smartphone tutorials, and seasonal square dancing. 4. Feedback and Influence: Villagers were involved in design consultations for the neighborhood center, which was designed by the East China Architectural Design and Research Institute (ECADI). Engineers provided architectural drawings to local residents, after which village representatives, Party members, and senior residents convened to collectively vote on the preferred schemes. However, many villagers encountered difficulties interpreting the drawings, which limited the extent of their engagement in the decision-making process. 5. Digital Technology Use: Regularly uses a smartphone; has no experience with voice-based AI systems. Information about community services—such as barbershop operating hours—is typically displayed on a large digital screen at the entrance of the neighborhood center. |

Appendix A.2

The questionnaire design and corresponding data from the second field survey are presented in Table A2. The results of the second field survey reveal significant variation in the perceived importance of different functional elements within rural public cultural spaces. Among all items, the most highly rated elements are Marketplace for Local Products and Souvenirs (mean (M) = 4.579, standard deviation (SD) = 0.607) and Children’s Educational and Recreational Facilities (M = 4.526, SD = 1.073). The high mean scores, coupled with relatively low standard deviations, indicate strong consensus among respondents regarding the value of spaces that support local economic activity and child-centered engagement. Other top-rated elements include Leisure and Entertainment Areas (M = 4.474) and Film Screening Rooms (M = 4.263), reflecting a strong demand for recreational and cultural consumption functions. Conversely, elements with moderate importance ratings include Reading Rooms (M = 3.526), Community Assembly Halls (M = 3.737), and Smart Systems for Science and Moral Education (M = 3.105). These indicate a general recognition of their value but suggest less immediate relevance or effectiveness in practice. Notably, Spaces for Worship and Religious Ceremonies (M = 2.526), Music Rehearsal Rooms (M = 2.737), and Party-Building Facilities (M = 3.000) received the lowest average scores. These results highlight a critical need to prioritize child-friendly, leisure-oriented, and economically supportive spaces in rural public cultural infrastructure, while reconsidering or adapting the role of spaces with lower perceived value to better reflect evolving rural lifestyles and preferences.

Table A2.

Structured questionnaire design and corresponding data of the second field survey.

Table A2.

Structured questionnaire design and corresponding data of the second field survey.

| Structured Questionnaire Design | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Section | Content | |

| 1 | Basic Information | Age; Gender; Education Level; Occupation. | |

| 2 | Evaluation of Functional Elements | Respondents were asked to rate the importance of each functional element below on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not Important at All, 5 = Very Important). | |

| 2.1 | Cultural Display and Education | Village Exhibition Hall; Film Screening Room; Reading Room; Rural Night School; Smart Systems for Science and Moral Education. | |

| 2.2 | Community Gathering and Social Interaction | Community Assembly Hall; Casual Chat Areas; Leisure and Entertainment (e.g., chess and cards). | |

| 2.3 | Recreation and Sports | Indoor Sports Facilities; Dance Studio; Music Rehearsal Room; Children’s Educational and Recreational Facilities; Interactive Cultural Projects (e.g., augmented reality (AR)-enabled intangible cultural heritage (ICH) experience). | |

| 2.4 | Commerce and Information | Marketplace for Local Products and Souvenirs; Village Affairs Bulletin Board; Party-Building Facilities. | |

| 2.5 | Religious and Cultural Activities | Worship and Religious Ceremonies; Spaces for Hosting Cultural, Artistic, and Academic Events; Holiday Performances; Event Venues for Weddings, Funerals, and Festivals. | |

| Questionnaire Data | |||

| 1. Basic Information | |||

| No. | Demographic Indicator | Summary Result | |

| 1.1 | Total Number of Respondents | 19 | |

| 1.2 | Age | Mean = 54.684; Standard Deviation = 16.740 | |

| 1.3 | Gender | Male: 8 (42.1%); Female: 11 (57.9%) | |

| 1.4 | Educational Attainment | Illiterate: 2 (10.5%); Primary School: 5 (26.3%); Junior High School: 3 (15.8%); High School: 1 (5.3%); Technical Secondary School: 1 (5.3%); Undergraduate: 6 (31.6%); Graduate: 1 (5.3%) | |

| 1.5 | Respondent Role | Rural administrators: 3 (15.8%); Villagers: 16 (84.2%) | |

| 2. Evaluation of Functional Elements | |||

| No. | Activity Element | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 2.1.1 | Village Exhibition Hall | 3.474 | 1.219 |

| 2.1.2 | Film Screening Room | 4.263 | 0.933 |

| 2.1.3 | Reading Room | 3.526 | 1.349 |

| 2.1.4 | Rural Night School | 3.368 | 1.383 |

| 2.1.5 | Smart Systems for Science and Moral Education | 3.105 | 1.487 |

| 2.2.1 | Community Assembly Hall | 3.737 | 1.195 |

| 2.2.2 | Casual Chat Areas | 3.895 | 1.329 |

| 2.2.3 | Leisure and Entertainment | 4.474 | 1.020 |

| 2.3.1 | Indoor Sports Facilities | 3.579 | 1.610 |

| 2.3.2 | Dance Studio | 3.474 | 1.389 |

| 2.3.3 | Music Rehearsal Room | 2.737 | 1.327 |

| 2.3.4 | Children‘s Educational and Recreational Facilities | 4.526 | 1.073 |

| 2.3.5 | Interactive Cultural Projects | 4.105 | 1.150 |

| 2.4.1 | Marketplace for Local Products and Souvenirs | 4.579 | 0.607 |