Abstract

While extensive research has examined the contribution of urban parks to well-being, empirical evidence on the role of cultural attributes in historical urban parks and their impact on visitors’ well-being remains limited. This study explores the impact of physical characteristics of historical urban parks on well-being from the perspective of human settlement environment. Quantitative data were collected from 11 urban parks in Wuhan, China, combining online crowdsourcing for physical characteristic assessments and questionnaire surveys for psychological evaluations. Machine learning techniques, spatial analysis, and statistical methods including multistep regression and Bootstrap sampling were employed to test our hypotheses. Our results demonstrate that objective physical features—including park area, green coverage rate, green space shape index, and the proportion of heritage landmarks—positively influence well-being, whereas road density exhibits a negative association. Cultural perception and place attachment serve as significant mediators between physical characteristics and well-being outcomes, with the proportion of heritage landmarks influencing well-being through a dual mediation path. Additionally, we found interaction effects between physical and psychological factors, with education level moderating the relationship between cultural perception and well-being. These findings advance environmental psychology theory by elucidating how historical elements foster unique pathways to well-being, distinct from those offered by conventional green spaces. Our research provides evidence-based guidance for historical urban park design and renovation in the context of urban renewal, where balancing preservation and modernization presents significant challenges.

1. Introduction

China’s urban landscape has undergone profound transformation due to rapid urbanization, with the urbanization rate reaching 67% in 2024, signaling a pivotal shift toward urban regeneration [1]. This transition underscores the urgent need to optimize limited urban spaces for enhancing residents’ well-being—a priority widely recognized by policymakers and researchers [2,3,4].

As critical components of urban green infrastructure, urban parks serve as vital interfaces connecting citizens with nature. They fulfill multifaceted roles, including enhancing environmental quality, fostering social interaction, and promoting public health via recreational activities [5,6]. The diverse elements within parks—including vegetation, pathways, and recreational facilities—have been demonstrated to reduce psychological stress and enhance residents’ well-being [7].

Although extensive research has explored the environmental and social benefits of urban parks, the cultural dimensions of historical parks remain understudied. Unlike conventional parks, historical urban parks are characterized by rich cultural heritage and deep-rooted community ties, fostering unique socio-cultural attributes shaped by generational public engagement [8]. Current research in this field has predominantly focused on heritage conservation and cultural value assessment, with limited attention to public perception and utilization patterns [9]. These parks not only provide tangible links to cultural heritage [10] but also foster cultural identity and strengthen place attachment.

According to environmental perception theory, individuals’ interpretation of their surroundings varies significantly depending on cognitive, economic, and environmental factors [11,12]. While personal perceptions of historical parks’ cultural attributes may differ, research indicates the existence of shared cognitive patterns across diverse cultural backgrounds [13,14], particularly in environmental familiarity and attitudes.

Place attachment, a concept rooted in environmental psychology, represents the emotional bond between individuals and specific locations [15]. This attachment comprises place dependence and place identity [16,17,18], influenced by physical characteristics, attractiveness, and user engagement [19,20]. Recent studies have identified place attachment as a crucial mediator in understanding how environmental features contribute to user well-being [21,22].

Individual well-being is shaped by both personal factors (age, income, and health) and environmental characteristics (public services, transportation, and natural facilities) [7]. Despite established correlations between place attachment and well-being [23,24], current research tends to focus separately on either park functions [25,26] or theoretical well-being frameworks. This disciplinary segregation has created a knowledge gap regarding the mechanisms through which historical parks’ physical characteristics influence resident well-being [7,27,28,29].

To bridge this gap, we integrate crowdsourced geospatial data with questionnaire surveys to empirically analyze 11 historical parks in Wuhan’s high-density urban context. Using park physical characteristics, cultural perception, and place attachment as independent variables with subjective well-being as the dependent variable, we aim to make three key theoretical contributions: (1) establishing an integrated framework connecting physical environment, cultural meaning, and psychological outcomes in historic park contexts; (2) quantifying the mediating effects of cultural perception and place attachment; (3) identifying optimal design interventions for different demographic groups. Specifically, we investigate the following:

- Which physical characteristics of historical parks positively impact well-being;

- Through what mechanisms these parks contribute to well-being;

- How historical parks can be enhanced to improve perceived well-being.

While the relationship between parks and well-being has been established (Kim et al., 2018) [7], our study’s unique contribution lies in its focus on historical parks’ cultural attributes and innovative methodological approach combining diverse data sources.

1.1. The Relationship Between Historical Parks and Well-Being

Global urbanization continues to accelerate at an unprecedented rate. According to the United Nations’ 2018 World Urbanization Prospects, 55% of the world’s population currently resides in urban areas, with projections indicating an increase to 68% by 2050. This rapid urbanization has heightened scholarly and public interest in urban parks as critical contributors to residents’ well-being [7]. Urban planners and researchers increasingly recognize the significant role of urban parks in enhancing residents’ happiness and subjective well-being [5,25].

Historical parks offer multidimensional benefits through two primary mechanisms. First, as green spaces, they provide urban residents with valuable opportunities for nature interaction, which has been consistently associated with reduced psychological stress and improved mental health outcomes [30,31,32,33]. Second, as public spaces, they facilitate physical activity, social interaction, and recreational engagement. These combined functions enhance the esthetic quality of urban environments and residents’ quality of life, thereby promoting both physical and psychological well-being [34].

Beyond these general benefits, historical parks possess distinctive cultural attributes that differentiate them from conventional urban parks. Their material elements—including historical architecture, cultural relics, and heritage landscapes—foster stronger spiritual identity and place attachment among urban residents compared to newly constructed environments lacking historical significance [35,36]. Attention Restoration Theory (ART) [37] posits that historical features, through their extensibility and soft fascination, effectively mitigate directed attention fatigue in urban populations. Environmental esthetics research has demonstrated a consistent preference for historical sites and heritage features [38,39], as these preserved characteristics establish tangible connections with the past and embody collective cultural traditions [40]. This temporal dimension renders historical parks more conducive to developing local attachment than their modern counterparts [41,42]. Furthermore, studies have indicated that the formation of such attachment demonstrates significant correlations with age and life experiences [43,44], a phenomenon that can also be explained through the lens of cultural capital theory [45].

Wang (2021) proposed that historical parks influence residents’ place dependence through four dimensions: intellectual attachment (cognitive connection to historical knowledge), autobiographical attachment (personal memories associated with the space), life dependence (integration into daily routines), and nostalgic attachment (emotional connection to perceived historical continuity) [46]. Empirical evidence from heritage sites, such as Hoi An, Vietnam, demonstrates that cultural heritage significantly enhances residents’ feelings of pride, honor, and subjective well-being [47].

Based on this theoretical and empirical foundation, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1.

The distinctive characteristics of historical urban parks positively impact visitors’ well-being.

1.2. The Relationship Between Place Attachment and Well-Being

Place attachment is commonly defined as the emotional and cognitive bond between an individual and a specific place [48]. This multidimensional construct manifests through two primary, interrelated dimensions. First, place dependence emerges when a place effectively satisfies people’s functional needs, leading to increased reliance on that environment [49]. This dimension is fundamentally grounded in the physical characteristics and visual conditions of the place [19] and represents the functional aspect of place attachment [50]. Second, place identity constitutes another critical dimension, representing the congruence between individual self-concept and place-based symbolic meanings [51]. These dimensions elucidate key determinants of place attachment, such as place image [19], visitor engagement [52], user experience, and personal beliefs [53]. Notably, the physical attributes of a place offer particular advantages for practical application, as they are relatively straightforward to measure and modify. Interventions targeting size, typology, building height, and esthetic elements can effectively enhance place attachment [54].

Empirical studies consistently demonstrate significant associations between place attachment and psychological well-being. Studies demonstrate that person–place relationships substantially influence residents’ perceived well-being [55], while identification with and dependence on local environments enhance individuals’ sense of belonging, purpose, and meaning in life [56]. Place attachment strengthens emotional connections with the surrounding environment, consequently improving subjective well-being [57]. Indeed, place attachment has emerged as a significant predictor of neighborhood satisfaction and happiness [4].

It is important to acknowledge the potential bidirectionality in this relationship. Some scholars suggest that psychological factors such as happiness or satisfaction may more strongly predict place attachment than geographical or demographic variables [16]. These psychological factors may also mediate relationships between experiential elements and place attachment [16]. Consequently, research has identified a reciprocal feedback mechanism wherein well-being influences place attachment, which subsequently enhances well-being [54,55,56,57].

In applied contexts, particularly park management, improving environmental quality and enhancing residents’ perceived well-being represent primary objectives [58,59,60]. Therefore, while acknowledging the potential bidirectional relationship, the present study focuses specifically on the influence of place attachment on well-being rather than the reverse effect. Based on the theoretical framework outlined above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2.

Place attachment to historical urban parks positively influences well-being.

H3.

The characteristics of historical urban parks positively influence well-being through the mediating effect of place attachment.

1.3. The Relationship Between Cultural Perception and Well-Being

Perception encompasses the process through which the human body receives external stimuli via sensory organs, converts these stimuli into neural signals, and transmits them to the brain for processing and interpretation [61]. In environmental science, cultural perception denotes individuals’ cognitive interpretation of cultural and environmental elements [62]. Studies demonstrate that place attachment correlates with historical understanding, suggesting cultural perception is integral to place identity formation [42,63,64,65,66]. Furthermore, place attachment can motivate protective behaviors toward valued buildings or historical sites that might otherwise face demolition during urban development [31], thereby preserving the material foundations that support cultural perception.

Qualitative research has identified potential mechanisms underlying these relationships, suggesting that historical elements possess two emotionally significant attributes: restoration potential and visual impact [46]. Within historical parks, features such as ancient architecture, heritage trees, scenic designations, and interpretive texts directly communicate historical and cultural narratives to visitors through visual channels. Asian cultures tend to emphasize contextual participation, with greater attention to holistic environmental elements in cultural perception [31]. This perceptual tendency aligns closely with the cultural perception processes evident in Chinese historical parks. Based on these theoretical foundations, we propose the following hypotheses:

H4.

Cultural perception in historical urban parks positively influences well-being.

H5.

The characteristics of historical urban parks positively influence well-being through the mediating effect of cultural perception.

H6.

Cultural perception in historical urban parks positively influences well-being through the mediating effect of place attachment.

H7.

The characteristics of historical urban parks positively influence well-being through the sequential mediating effects of cultural perception and place attachment.

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of Research Subjects

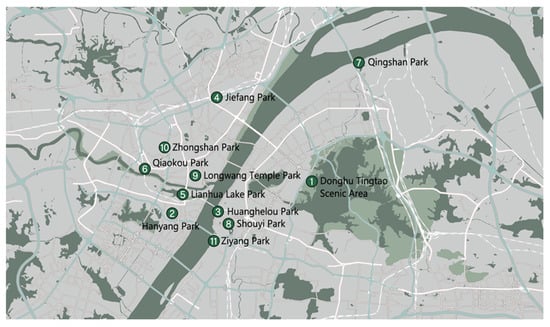

According to the definition established by ICOMOS-IFLA and existing research [67], historical urban parks in China typically refer to public parks constructed over 50 years ago that incorporate partially restored classical gardens. As a representative historical and cultural city in the Yangtze River basin, Wuhan’s park system exhibits three distinctive characteristics: (1) temporally spanning different historical layers from the Ming–Qing period to the early founding of the People’s Republic (1368–1960); (2) spatially distributed across all seven central urban districts, reflecting the unique “Two Rivers and Four Banks” geographical pattern; (3) culturally encompassing three major typologies: imperial gardens, commercial port parks, and industrial heritage parks. Based on these criteria, this study selected 11 parks as the research sample after comprehensive consideration of construction history (pre-1960), regional representativeness (at least one park per administrative district), and size (≥1 hectare) (Table 1, Figure 1). It should be specially noted that although Huanghelou Park (No. 3) underwent renovation in 1985, its core value as one of the “Three Great Towers of South China” and its architectural craftsmanship strictly adhere to the records in the Qing Dynasty’s “Huanghelou Chronicles”, serving as an anchor point along Wuhan’s “Historical and Cultural Axis” with irreplaceable research significance.

Table 1.

Details of Wuhan’s historical urban parks.

Figure 1.

Distribution map of Wuhan’s historical urban parks.

2.2. Objective Indicators of the Park

Based on the physical feature framework of parks developed by previous scholars on well-being [14,68,69] and combined with the characteristics of historical urban parks themselves, to more comprehensively display the differential characteristics between different parks, we introduced a total of nine objective variables at three levels: space structure, infrastructure, and historical features. The data were mainly obtained through local land use data, machine learning techniques, and Baidu Map public data. The space structural characteristics mainly outline the land area and complex shape of the parks; the infrastructure features aim to quantify and statistically analyze their roads, greenery, and entrances and exits; the most distinctive historical features are reflected in two sets of variables, namely, the proportion of ancient building area and the proportion of heritage landmarks (Table 2).

Table 2.

Details of Objective Indicators.

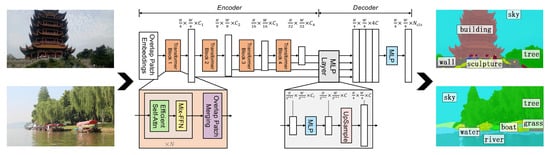

The data regarding green space shape index, green viewing rate, and color richness in space structural features were obtained through semantic segmentation and feature extraction of image data using the SegFormer-B5 model through machine learning (Figure 2). Compared to other models, SegFormer B5 is a simple, effective semantic segmentation method that considers accuracy and robustness. It achieved a highly efficient and advantageous 51.0% average intersection to union ratio [65].

Figure 2.

Segmentation schematic diagram based on SegFormer-B5.

For the training process, we utilized the standard ADE20K dataset configuration with 20,210 images for training and an additional 2000 images as the validation set to assess model accuracy. Training was terminated when the accuracy exceeded 80%. The initial learning rate was set to 0.00006 with a “poly” LR scheduler using a default factor of 1.0. Following Xie E et al. (2021)’s methodology [65], we deliberately avoided commonly used techniques such as OHEM, auxiliary loss, or class-balanced loss. To verify reliability, we conducted random sampling of 155 test images for manual label verification, achieving segmentation accuracy exceeding 80% for all key elements (trees, shrubs, lawns, buildings, sky, etc.), thereby confirming the robustness of our results [66].

Finally, a training model was used to perform semantic segmentation on 599 shared images of residents from 11 historical parks on Baidu Maps, obtaining data on three variables: green space shape index, green view rate, and color richness.

2.3. Composition and Distribution of Questionnaires

2.3.1. Scale Development and Questionnaire Composition

The measurement instruments for cultural perception and place attachment were adapted from established scales with demonstrated reliability in previous studies [46,70,71,72]. To ensure psychometric robustness in our specific context, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and reliability tests on the adapted scales.

For cultural perception, the two-dimensional structure (understanding and identification) showed good fit indices (CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.921, and RMSEA = 0.042) with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89 for understanding, and α = 0.91 for identification). The scale incorporated historically relevant descriptors to enhance content validity.

The place attachment scale, building on Williams et al.’s (1992) [73] framework, demonstrated strong discriminant validity between place dependence (α = 0.88) and place identity (α = 0.90) factors (HTMT = 0.71). CFA results confirmed the hypothesized two-factor structure (χ2/df = 2.13, SRMR = 0.038).

Well-being measures adopted from prior studies [74,75,76] maintained excellent reliability (α = 0.93) across the three proposed dimensions (individual, environmental, and social). Table 3 presents the finalized measurement framework with standardized factor loadings (all >0.7) and composite reliability scores (all >0.8).

Table 3.

Composition and indicators of variables.

2.3.2. Details and Distribution of Questionnaire

Based on the aforementioned indicators, this study developed a structured questionnaire consisting of four sections. The first section collected respondents’ demographic information, including gender, age, educational level, occupation, and frequency of park usage. The remaining three sections respectively addressed the measurement indicators for cultural perception, place attachment, and well-being. Each section included 6–8 items (21 total), rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). These scores provided the quantitative basis for analysis.

This study conducted questionnaire distribution and collection in 11 historical urban parks from 16 November to 3 December 2023. Following the park sequence shown in Table 1, three survey teams worked simultaneously each week to cover 3–4 parks per week, completing the entire data collection process within three weeks. The distribution dates of the questionnaires were selected during sunny weather, with a moderate temperature and suitable conditions for outdoor activities. The locations for distributing questionnaires mainly included park entrances and exits, important landscape sites, and points along the main visitor routes to ensure that the participants had visited most or all of the parks’ features. A total of 368 valid questionnaires were collected. All participants were informed of the research purpose, procedures, and data usage prior to completing the questionnaire, and their participation was voluntary. They retained the right to withdraw at any time, and all data were anonymized. The study strictly adhered to privacy protection protocols, with personally identifiable information removed from the questionnaire data to ensure participant confidentiality.

2.4. Analysis Methods

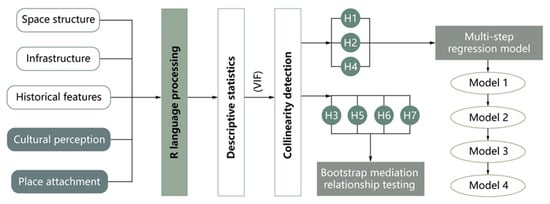

In this study, the data analysis was performed using R language. Firstly, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis on visitor data to understand the distribution of variables such as gender, age group, education, and occupation, and conducted preliminary statistical analysis on the overall data. Subsequently, we conducted collinearity detection, using variance inflation factor (VIF) to evaluate multicollinearity between variables to ensure the robustness of the model.

Next, we constructed multiple linear regression models, gradually introducing demographic characteristics, objective physical attributes of parks, cultural perception, place attachment, and comprehensive interaction variables to explore the impact of these factors on visitors’ perception of well-being in historical urban parks. In addition, we calculated the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values for each model to evaluate its superiority and inferiority.

To further explore the impact mechanism of well-being, we conducted a mediation effect analysis. We used the Bootstrap method to test mediation relationships. We constructed a mediation model and a dependent variable model, conducted Bootstrap sampling on 1000 samples using the mediation package, and calculated the point estimate (B) of the mediation effect and the 95% confidence interval of the percentile method to evaluate the significance of the effect (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Technical roadmap.

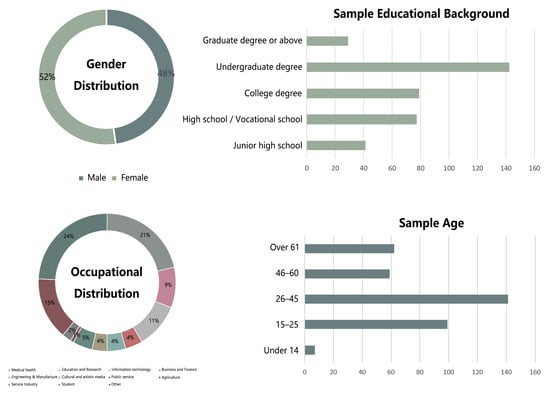

2.4.1. Sample Demographic Information

Figure 4 presents the demographic information of the study sample. Among the participants, the distribution of males and females was relatively similar, with males accounting for 48% and females accounting for 52%. Regarding age distribution, young adults and middle-aged people (i.e., aged 26–45) accounted for the largest proportion, followed by young people aged 15–25. Meanwhile, participants were generally relatively well educated, with more than half having attained an undergraduate degree or higher. Regarding occupational distribution, the healthcare industry and other industries (or retirees) accounted for the largest proportion.

Figure 4.

Sample demographic information.

2.4.2. Collinearity Detection of the Model

Before conducting multiple regression analysis, collinearity detection is an indispensable step, ensuring the stability and interpretability of model results. In this study, we used the variance inflation factor (VIF) in R language to evaluate the degree of collinearity between independent variables. Following detailed analysis, we found that the addition of machine learning-based color richness and green view rate in the previously constructed indicator system resulted in VIF values exceeding the standard value by 10, which did not meet the conditions for further regression analysis; therefore, they were excluded. After further optimization, the VIF values of all other independent variables did not exceed the threshold of 10, and the tolerance values were all greater than 0.1, indicating that there was no serious multicollinearity problem among the independent variables [4,77]. This discovery provides strong support for our subsequent regression analysis as it proves that the regression coefficients in the model are robust and reliable. Based on these reliable regression coefficients, we were able to more accurately interpret how the independent variable affects the happiness of historical urban parks, thereby ensuring the explanatory power and credibility of this study (Table 4).

Table 4.

Collinearity diagnosis for the predictors.

2.4.3. Analysis of Correlation

This study analyzed the impact of different variables on the well-being of historical urban parks through a multistep regression method. Conducting multistep regression according to different categories was conducive to clearly determining the direct correlation between each category and well-being. In Model 1, four demographic variables were first introduced: gender, age group, educational background, and occupation. In Model 2, seven physical characteristic variables related to parks were further introduced, including park area, green space shape index, and green coverage rate, among others. Model 3 incorporated cultural perception and place attachment factors to analyze their association with well-being. In Model 4, we not only included basic demographic variables, park feature variables, and perception variables, but also introduced several interaction variables to further explore the impact of the interactions between these variables on well-being, making the correlation analysis more scientific.

2.4.4. Analysis of Mediating Effects

The analysis of mediating effects is a key step in exploring the pathways through which the physical characteristics of parks affect well-being. Specifically, we constructed a mediation model and a dependent variable model and conducted Bootstrap sampling on 1000 samples to estimate the significance of the mediation effect. We analyzed the indirect effects of variables such as cultural perception, green space shape index, proportion of heritage landmarks, and green coverage rate on well-being. For example, we explored the impact of cultural perception on well-being through place attachment, the impact of green space shape index on well-being through place attachment, the impact of proportion of heritage landmarks on well-being through cultural perception, and the impact of green coverage rate on happiness through place attachment. In addition, we constructed a more complex model to analyze the impact of the proportion of heritage landmarks on well-being through the dual mediating effect of cultural perception and place attachment. In these analyses, we controlled for variables such as gender, age group, education, and occupation, to ensure the robustness of the results.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Correlation Analysis

Table 5 presents the results of the multistep regression correlation analysis. The results of Model 1, which mainly involved demographic analysis, showed that the R2 (Multiple R-squared) value was 0.05722, meaning that the model explains 5.7% of the variance in well-being; this indicates that demographic variables have limited contribution in explaining well-being. We did not initially formulate hypotheses regarding the relationship between demographic characteristics and well-being. But it is worth noting that in this model, the age group (β = 0.136, p < 0.001, not mixed) has a significant positive impact on well-being, indicating that older visitors may feel happier in historical urban parks than younger visitors.

Table 5.

Modeling the effects of predictors on well-being.

The R2 value of Model 2 increased to 9.3%, demonstrating a certain degree of improvement from 5.7% in Model 1. The AIC value also decreased, indicating that the introduction of objective physical quantities in the park enhanced the explanatory power of the model. The results provide empirical evidence supporting our general hypothesis in H1 that parks’ physical characteristics positively influence well-being, though we had not specified directional predictions for individual variables a priori. It is worth noting that park area (β = 1.628 × 10−6, p < 0.001, not mixed), green coverage rate (β = 1.294, p < 0.001, not mixed), green space shape index (β = 0.7833, p = 0.0451, not mixed), and proportion of heritage landmarks (β = 2.577, p < 0.001, not mixed) had significant positive impacts on well-being. However, the findings regarding road density (β = −2.977, p < 0.001, not mixed) contradict our initial hypothesis in H1, revealing an unexpected negative association between path density and perceived well-being.

H2 and H4 hypothesized a direct positive effect of place attachment on well-being, and this hypothesis was confirmed in Model 3, which added the variables of cultural perception and place attachment to Model 2. The results indicated that cultural perception (β = 0.103, p < 0.016, not mixed) and place attachment (β = 0.526, p < 0.001, not mixed) had highly significant positive impacts on well-being. The R2 value of the model increased significantly to 0.518, while the AIC value further decreased to 542.605, demonstrating higher explanatory power and fit.

In Model 4, we introduced four sets of interaction variables to further explore the impact of interactions between different variables on the well-being of visitors to historical urban parks. Among them, regarding the proportion of ancient building area * cultural perception (β = 5.018, p = 0.011, not mixed), green coverage rate * place attachment (β = 0.404, p = 0.034, not mixed), the two interaction variables were found to have a significant positive impact on well-being. Meanwhile, educational background * cultural perception (β = −0.068, p = 0.017, not mixed) was significantly negatively correlated with well-being.

During the stepwise regression analysis process, each model gradually improved and reduced its AIC value, indicating continuous improvement in the model’s fit and explanatory power. The specific regression coefficients and significance levels are detailed in Table 5.

3.2. Results of Mediating Effect Analysis

The mediation hypotheses (H3, H5–H7) proposed in the preceding sections all examine the mediating roles of cultural perception and place attachment between park physical characteristics and perceived well-being. Specifically, H3 posits that park physical characteristics positively influence well-being through the mediating effect of place attachment; H5 hypothesizes that park physical characteristics enhance well-being through cultural perception mediation; H6 proposes that cultural perception improves well-being via place attachment mediation; while H7 postulates that park physical characteristics affect well-being through a two-step mediation process involving both cultural perception and place attachment.

Through four sets of mediation analyses (M1-M4, see Table 6 for results), we found that while the mediation effects in M1 and M4 were statistically significant (thereby confirming hypotheses H6 and H7), those in M2 and M3 were non-significant (thus providing insufficient support for H3 and H5).

Table 6.

Mediating effect analysis.

In M1, the average impact of “cultural perception” transmitted through the mediating variable “place attachment” on “well-being” was 0.340. The estimated value of the prop mediated effect was 0.799, indicating that 79.66% of the impact of cultural perception on well-being was achieved through the mediating variable of place attachment, thus proving that place attachment plays a key mediating role between cultural perception and well-being.

In the two-step mediation effect model M4, the proportion of heritage landmarks was found to have a significant positive impact on place attachment through cultural perception. In the second step, cultural perception was found to have a positive impact on well-being through place attachment mediation, indicating that the proportion of heritage landmarks had a significant positive impact on well-being through cultural perception and place attachment mediation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Demographic, Environmental, and Psychological Factor

This study systematically examined the comprehensive impact mechanisms of demographic characteristics, physical environmental features, psychological cognitive factors, and their interactions on visitors’ well-being in historical urban parks through a stepwise regression model. The findings reveal multi-level influencing characteristics that require in-depth interpretation combining empirical data with theoretical frameworks.

Regarding demographic factors, the results show that while the overall impact of demographic characteristics on well-being did not reach statistical significance, age emerged as a prominent influencing factor. Specifically, elderly visitors experienced significantly higher levels of well-being in historical urban park environments compared to younger groups. This finding corroborates with the research conclusions of Lai et al. (2023) [43] and Lucchesi et al. [44], who similarly observed that elderly frequent park users exhibit stronger well-being. Further analysis suggests this phenomenon can be explained through cultural capital theory [45]: on one hand, the “embodied cultural capital” accumulated by the elderly through long-term life experience enhances their ability to decode historical symbols; on the other hand, frequent park use behavior [43] promotes the formation of stable behavioral patterns, which are transformed into emotional well-being through the mediating variable of place attachment. Lucchesi et al. (2021) [44] further indicate significant differences in sensitivity to well-being influencing factors across age groups, reflecting the evolving characteristics of intergenerational cultural cognition patterns.

In the dimension of environmental physical characteristics, the study obtained several important findings. First, the introduction of park physical feature variables in the second stage significantly improved the model’s overall explanatory power. This finding aligns with research by Mouratidis et al. (2022) [4] and Yuan et al. (2018) [33], who both confirmed the positive impact of green space characteristics on well-being. Specifically, this study found significant positive correlations between park area, green coverage rate, and well-being, consistent with existing research conclusions. More importantly, the study made important expansions in indicator dimensions: it revealed for the first time the positive association between green space shape index and well-being, which can be explained by Attention Restoration Theory [37]—complex green space boundary morphology promotes cognitive recovery by providing “soft fascination.” Meanwhile, heritage landmark proportion also showed significant positive influence, embodying where material carriers strengthen cultural identity by activating collective memory. Notably, road density showed significant negative impact, supporting that excessive road density damages the “being away” dimension of environmental experience, thereby reducing well-being.

At the psychological mechanism level, the study revealed the chain mediating effect of cultural perception and place attachment. Data analysis showed that cultural perception constructs cognitive frameworks through symbolic decoding, while place attachment completes the transformation from cognition to emotion. Particularly noteworthy are the interaction analysis results: in high-proportion heritage building environments, visitors with stronger cultural identification exhibited greater well-being; in areas with abundant greenery, visitors with stronger place attachment had better experiences. These findings provide an important basis for the differentiated design of historical parks.

However, the study also discovered an anomaly worthy of in-depth exploration: education level showed significant negative moderating effect on the cultural perception pathway. This indicates that when education level and cultural perception increase simultaneously, their combined effect on well-being shows negative moderation characteristics. This phenomenon can be partially explained through highly educated groups developing more critical cultural interpretation patterns, and this “reading at a distance” approach potentially weakening the emotional mechanism of obtaining well-being through cultural resonance. This finding provides a new theoretical perspective for understanding park experience differences among social groups.

4.2. Mediating Role of Place Attachment and Cultural Perception

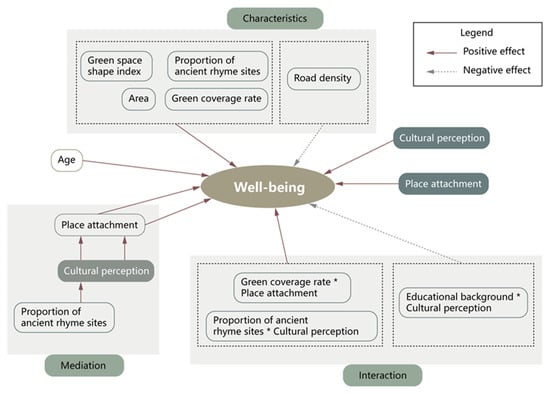

At the level of mediating effects, this article proposes four mediating relationship hypotheses, H3, H5–7, based on the previous research framework mentioned earlier. The results indicated that cultural perception mediated by place attachment has a significant positive impact on well-being. This suggests that place attachment plays an important mediating role between cultural perception and well-being, which is consistent with previous studies of the mediating role of place attachment [55,56,57]. In addition, this indicates that in the use of historical urban parks, the cultural perception and formation of visitors play a crucial role in the park’s place dependence and place identity. On the other hand, the proportion of heritage landmarks has a positive impact on well-being through the two-step mediating effect of cultural perception and place attachment. This can also indicate that the proportion of heritage landmarks in historical urban parks can directly affect visitors’ perception of historical and cultural information, and further affect their identification and dependence on places, ultimately affecting their subjective well-being. The discovery of these two mediating roles provides a powerful entry point for enabling in-depth understanding of the mechanism by which historical elements in parks affect visitors’ well-being. However, the mediating pathways hypothesized in H3 and H5 were not found to be statistically significant. Figure 5 comprehensively presents the path results of interactions among various factors. Regarding the mediating effects, place attachment emerges as the most crucial mediating factor, exerting the strongest influence in the pathways transmitting well-being effects.

Figure 5.

Conclusion of relationships between variables. * Indicates the interaction between two variables.

4.3. Research Limitations and Prospects

This study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, while encompassing 11 historical urban parks, the sample size was constrained to 368 valid questionnaires due to limited research resources. Second, the single-city (Wuhan) focus, though representative, precludes cross-regional comparisons and fails to account for seasonal usage patterns. Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, and the selected park feature indicators may have omitted potentially significant variables. Future research should expand both sample sizes and physical characteristic categories, incorporating longitudinal tracking and multi-regional comparisons, with particular attention to the following: (1) long-term effects of park renovations, (2) digital enhancement of historical elements to improve cultural perception, and (3) mechanism variations across different cultural and geographical contexts.

In the future, with the help of the above physical characteristics, urban planners can implement more targeted updates and renovations of historical urban parks. Firstly, at the level of green space, they can focus on improving the green coverage rate, greening quality level, and green space openness of parks, thereby providing more activity space for visitors. Meanwhile, they should focus on renovating or adding heritage landmarks, highlighting the historical and cultural characteristics of the park and the local space, enhancing visitor perception, and ultimately enhancing overall subjective well-being. Secondly, based on differences in subjective well-being among individuals of different ages and educational backgrounds, cultural sites with understanding gradients should be set up for different groups in park renovation design to enhance overall cultural perception. While highlighting cultural experiences, the renovation of historical urban parks should also take into account distinctive functional features, such as providing for a variety of activities, to encourage visitors to develop place dependence and enhance their overall well-being through intermediary effects.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated how physical characteristics of historical urban parks influence well-being from the perspective of human settlement environment. Using machine learning techniques, spatial analysis, and statistical methods including multistep regression models and Bootstrap sampling, we analyzed data from network crowdsourcing and questionnaires to test our seven hypotheses (H1–7). Our findings reveal several significant relationships between park characteristics and well-being. First, objective physical features including park area, green coverage rate, green space shape index, and proportion of heritage landmarks positively influence visitors’ well-being, while road density shows a negative impact. Second, we identified important psychological mechanisms: cultural perception and place attachment serve as significant mediators between physical characteristics and well-being outcomes. Notably, the proportion of heritage landmarks influences well-being through a dual mediation path of cultural perception and place attachment. Additionally, we found interaction effects between physical and psychological factors, with education level moderating the relationship between cultural perception and well-being.

These findings hold global relevance for cities experiencing similar urbanization pressures. The identified mechanisms—particularly the dual mediation path through cultural perception and place attachment—offer transferable insights for preserving historical green spaces in diverse cultural contexts, from European heritage gardens to colonial-era parks in developing nations. Our methodology demonstrates how machine learning and spatial analysis can be adapted to assess cultural ecosystem services in different urban heritage settings.

The interaction effects between education level and cultural perception suggest universal tensions in balancing cultural preservation with modernization, a challenge facing historical parks from Paris to Tokyo. This underscores the need for culturally-sensitive design approaches that respect local heritage while accommodating evolving urban populations. These findings contribute to environmental psychology theory by demonstrating how historical elements in urban parks create unique pathways to well-being beyond those offered by conventional green spaces. Our research extends the understanding of place attachment in historical contexts and clarifies the psychological mechanisms connecting physical environment to subjective well-being. For urban planners and park managers, our results provide evidence-based guidance for historical urban park design and renovation. Specifically, maintaining appropriate green coverage, preserving heritage landmarks, limiting excessive pathway development, and enhancing elements that promote cultural connection can maximize well-being benefits. These considerations are particularly relevant in urban renewal contexts where balancing preservation and modernization presents challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.; methodology, Y.W. and Y.C.; software, X.W. and Y.W.; validation, C.S. and F.D.; formal analysis, C.S.; investigation, X.W. and Y.C.; resources, C.S. and F.D.; data curation, X.W. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, C.S. and Y.W.; visualization, X.W. and Y.W.; supervision, F.D. and X.C.; project administration, F.D. and X.C.; funding acquisition, C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 52408063, Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province grant number 2023AFB139 and China Association of Higher Education Higher Education Science Research Planning Project grant number 23MY0406.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhang, Y. Microlevel Evaluation of Land Use Efficiency in an Urban Renewal Context: The Case of Shenzhen, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2024, 150, 5023043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonne, C.; Adair, L.; Adlakha, D.; Anguelovski, I.; Belesova, K.; Berger, M.; Brelsford, C.; Dadvand, P.; Dimitrova, A.; Giles-Corti, B.; et al. Defining paths to healthy sustainable urban development 3. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, H.; Schmidt, A.J.; Wehling, H. Exploring wellbeing in human settlements A spatial planning perspective. Habitat Int. 2019, 87, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Yannakou, A. What makes cities live? Determinants of neighborhood satisfaction and neighborhood happiness in different contexts. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou Sideris, A.; Levy Storms, L.; Chen, L.; Brozen, M. Parks for an Aging Population: Needs and Preferences of Low Income Senior in Los Angeles. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2016, 82, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The relationship between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Jin, J. Does happiness data say urban parks are worth it? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 178, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreija, K. Historical gardens and parks: Challenges of development in the context of relevant regulations, definitions and termination. Moksl. Liet. Ateitis/Sci. Future Lith. 2012, 4, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulou, A.; Klados, A.; Malesios, C. Historical Public Parks: Investigating Contemporary Visitor Needs two thousand and twenty. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.C.; Barreiros, J.P. Are underwater archaeological parks good for fishes? Symbiotic relation between cultural heritage preservation and marine conservation in the Azores. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2018, 21, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Guo, Y.; Han, X. The relationship research between restorative perception, local attachment and environmental responsible behavior of urban park recreationists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothencz, G.; Blaschke, T. Urban parks: Visitors’ perceptions versus spatial indicators. Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotolo, F.; Rapuano, M.; Masullo, M.; Maffei, L.; Ruggiero, G.; Iachini, T. Well-being and multisensory urban parks at different ages: The role of interoception and audiovisual perception. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, S.; Van de Voorde, T. Which environmental features contribute to positive and negative perceptions of urban parks? A cross cultural comparison using online reviews and Natural Language Processing methods. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 218, 104307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A.; Budruk, M.; Schneider, I.E.; Stanis, S.A.W. Predicting place attachment among walkers in the urban context: The role of dogs, motivations, satisfaction, past experience and setting development. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well being on place attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, H.; Kurz, T.; Veneklaas, E.; Ramalho, C.E. Putting down roots: Relationships between urban forests and residents’ place attachment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 95, 128287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, T.; Yi, C.; Zhang, K. Effects and functional mechanisms of serious leisure on environmentally responsible behavior of mountain hikers: Mediating effect of place attachments and destination attractiveness. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 45, 100709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Ryan, C. Antecedents of Tourists’ Loyalty to Mauritius: The Role and Influence of Destination Image, Place Attachment, Personal Involvement, and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2011, 51, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, J. Antecedents and sequences of place attachment: A comparison of Chinese and Western urban tours in Hangzhou, China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Yasunaga, A.; Oka, K.; Nakaya, T.; Nagai, Y.; McCormack, G.R. Place attachment and walking behaviour: Mediation by perceived neighbourhood walkability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 235, 104767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Q. The formation process of tour attachment to a destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100828. [Google Scholar]

- Maricchiolo, F.; Mosca, O.; Paolini, D.; Fornara, F. The mediating role of place attachment dimensions in the relationship between local social identity and well being. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 645648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajala, K.; Sorice, M.G. Sense of place on the range: Landowner place meanings, place attachment, and well-being in the Southern Great Plains. Rangelands 2022, 44, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Vanos, J.; Kenny, N.; Lenzholzer, S. Designing urban parks that ameliorate the effects of climate change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.; Saberi-Pirooz, R.; Piri, K.; Abdoli, A.; Ahmadzadeh, F. Urban parks affect soil macroinvertebrate communities: The case of Tehran, Iran. J. Environ. Manag 2025, 373, 123871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.; Popham, F. Greenspace, urban and health: Relationships in England. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Jones, J.; Kaplan, S. The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Shahni, T.J. Greenspace and wellbeing in Tehran: A relationship conditional on a neighborhood’s crime rate? Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, T.; Clayton, S.; Neary, D.; Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: Mapping review of courses and causal paths. Health Place 2012, 18, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Hanlon, B. Urban green space, respiratory health and rising temperatures: An examination of the complex relationship between green space and adult asthma across racialized neighborhoods in Los Angeles County. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 258, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakınlar, N.; Akpınar, A. How perceived sensory dimensions of urban green spaces are associated with adults’ perceived restoration, stress, and mental health? Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Shin, K.; Managi, S. Subjective Well being and Environmental Quality: The Impact of Air Pollution and Green Coverage in China. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 153, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, L.E.; Lim, F.K.; Carrasco, L.R. The relationship between natural park usage and happiness does not hold in a tropical city state. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madgin, R.; Webb, D.; Ruiz, P.; Snelson, T. Resistance relocation and reconceptualization authentication: The experimental and emotional values of the Southbank Undercroft, London, UK. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Landscape character assessment, perception surveys of stakeholders and SWOT analysis: A holistic approach to historical public park management. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D. Back to nature? Attention restoration theory and the restorative effects of nature contact in prison. Health Place 2019, 57, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P. Perceived sensory dimensions: An evidence-based approach to greenspace aesthetics. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 126989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.C. How are old places different from new places? A psychological investment of the correlation between patina, spontaneous fantasies, and place attachment. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, K.; Karakida, K.; Iwachido, Y.; Mori, T.; Okuro, T. The designation of a historical site to maintain plant diversity in the Tokyo metropolitan region. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 84, 127919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Pitas, N.A.; Cho, S.J.; Yoon, H. The moderating effect of place attachment on visitors’ trust and support for recreational fees in national parks. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 98, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deal, B. Parks, Green Space, and Happiness: A Spatially Specific Sentiment Analysis Using Microblocks in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchesi, S.T.; Larranaga, A.M.; Ochoa, J.A.A.; Samios, A.A.B.; Cybis, H.B.B. The role of security and walkability in subjective well-being: A multigroup analysis among different age cohorts. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, E.; Johnson, B. Overview of cultural capital theory’s current impact and potential utility in academic libraries. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2023, 49, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Mapping Urban Residents’ Place Attachment to Historical Environments: A Case Study of Edinburgh. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, T.D.T.; Brown, G.; Kim, A.K.J. Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: The case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A partition organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W.; Jackna, T. The co creation/place attachment nexus. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F. Destination marketing and visitor experiences: The development of a conceptual framework. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 653–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hu, Z.; He, J.; Zou, X.; Morrison, A.M. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of tourist place attachment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, in press. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1447677025000270?via%3Dihub (accessed on 15 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jeong, C. Distinctive roles of tour eudaimonic and hedonic experiences on satisfactions and place attachment: Combined use of SEM and necessary condition analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A. Size and type of places, geographic region, satisfaction with life, age, sex and place attachment. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 47, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Fukushi, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Watanabe, R. The missing angles: Nature’s contributions to human well being through place attachment and social capital. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, N.G. Geographies of wellbeing and place attachment: Reviewing urban rural migrants. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 78, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, L.; Hu, Y. Cultural involvement and attributes towards tourism: Examining serial media effects of residents’ spiritual wellbeing and place attachment. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severcan, Y.C.; Torun, A.O.; Defeyter, M.A.; Bingol, H.; Akin, I.Z. Associations of children’s mental wellbeing and the urban form characteristics of their everyday places. Cities 2025, 160, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.; Campelo, A. The four Rs of place branding. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. The experienced psychological benefits of place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmholtz, H.V. Handbuch der Physiologischen Optik; Leopold Voss: Leipzig, Germany, 1867; pp. 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Z.; Luo, J.; Feng, Y.; Gao, J. Analysis of Cultural Perception of Tianjin Beining Park Based on Network Review Data. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 30, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak, A.; Bilewicz, M.; Lewicka, M. The merit of teaching local history: Increased place attachment enhancement civil engagement and social trust. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and effective design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Tan, W.; Wang, R.; Wendy, Y.C. From quantity to quality: Effects of urban greenness on life satisfaction and social inequality. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 238, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Document on Historical Urban Public Parks; ICOMOS: Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Azcárraga, C.A.; Diaz, D.; Zambrano, L. Characteristics of urban parks and their relationship to user well being. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Shao, G.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, P. Insights into cities’ experiences of cultural ecosystem services in urban green spaces based on social media analytics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 244, 10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van Dijk, T.; Tang, J.; Berg, A.E.v.D. Green space attachment and health: A comparative study in two urban neighborhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14342–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Brown, G.; Weber, D. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, W.; Lu, T. Landscape characteristics of university campus in relation to aesthetic quality and recycling preference. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 66, 127389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the community methodology: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Lei. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue space: The importance of water for preference, effect, and restoration rates of natural and build scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Balvanera, P.; Benessaiah, K.; Turner, N. Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L. Factor composition and differential analysis of recreational happiness in urban residential parks: A case study of Hangzhou. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 33, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.M. A cautionary rules of thumb for variance impact factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).