Abstract

REDD+ is a global mechanism that reduces greenhouse gas emissions by preventing deforestation and forest degradation, enhancing forest carbon stocks, and promoting sustainable forest management in developing countries. It plays a crucial role for developing countries in achieving climate targets under the Paris Agreement and can be implemented at the project, subnational, and national levels. Subnational REDD+ offers several advantages over project-level, such as reduced risk of overestimating emissions and enhanced management of leakage. However, the comprehensive opportunities and challenges of subnational REDD+ have not been extensively investigated in the literature. This paper aims to undertake a thorough review of subnational REDD+, highlighting its potential and the obstacles it faces. This systematic review synthesizes the existing literature on subnational REDD+ implementation, analyzing 54 peer-reviewed articles published between 2005 and 2024. The review identified three key factors for the effective implementation of subnational REDD+: financial, social, and institutional factors. Within these three factors, both opportunities and challenges were discussed, drawing on case studies and synthesizing practical implications. Our findings demonstrate that successful subnational REDD+ initiatives require integrated approaches that address the causal relationships between financing mechanisms, governance structures, and stakeholder engagement. The discussion further explores these interdependencies, revealing how constraints in one dimension create cascading effects across others. This study provides empirical insights and actionable recommendations for policymakers and project developers engaged in climate change mitigation efforts.

1. Introduction

Tropical forests continue to face substantial threats despite global efforts to reduce deforestation. Recent years have seen a modest decline in global deforestation rates, yet tropical forests remain heavily vulnerable, accounting for over 90% of total forest loss [1]. The emissions from tropical deforestation are significant, representing approximately half of total net emissions from the Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use (AFOLU) sector [2]. Beyond the direct human-induced deforestation, tropical forests still face many climate-related disturbances, such as forest fires, disease outbreaks, and severe weather events, creating a complex challenge for forest conservation efforts.

To address this problem, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+) emerged as a pivotal climate change mitigation strategy within the UNFCCC. REDD+ gained further prominence in Article 5 of the Paris Agreement, where Parties affirmed their commitment to implement REDD+ activities as an integral element of global climate commitment [3]. The “+” in REDD+ signifies additional activities beyond the avoided deforestation and degradation, encompassing the conservation of forest carbon stocks, sustainable forest management, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks [4].

The REDD+ activities have been implemented at multiple scales, including national, subnational, and project levels. According to UNFCCC Decision 1/CP.16, the primary objective of REDD+ is for national governments to implement activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by decreasing human pressure on forests at the national level. As an interim measure, it also recognizes subnational implementation reflecting national circumstances, capacities, and capabilities of each developing country and the level of support received [5]. In particular, establishing forest reference emission levels and/or forest reference levels (FREL/FRL) and a national forest monitoring system (NFMS) at subnational scales can work as a stepping stone to reach national-scale REDD+ implementation [6].

Early REDD+ efforts primarily focused on project-level implementation, with over 700 projects globally by 2022 [7]. Although these projects have achieved various degrees of success in generating carbon credits and financial returns, they have also exposed the limitations, including high risk of leakage [8], overestimation of carbon emission reductions and the credibility of baselines [9,10], limited participation of local people [11], and so on. In response to these limitations, there has been growing interest in subnational or jurisdictional approaches to REDD+ implementation.

Subnational REDD+ refers to programs implemented at the scale of administrative units such as states, provinces, or districts, integrating forest conservation efforts with broader sustainable development planning [12]. This approach aims to bridge the gap between localized projects and national-level policy frameworks, offering potential advantages in addressing leakage, ensuring policy coherence, and achieving economies of scale [13]. Voluntary carbon markets (VCM) also provide important pathways and learning opportunities at the national and subnational levels [6]. Voluntary carbon standards, exemplified by Verra’s Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) and Architecture for REDD+ Transactions—The REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard (ART-TREES), have started to provide detailed methodologies, especially for jurisdictional REDD+ [14,15]. These frameworks can facilitate establishing robust accounting methods and ensure marketability through the generation of high-quality credits.

Despite the increasing attention to subnational REDD+, the existing literature has primarily focused on technical aspects of implementation, particularly related to monitoring systems and reference level establishment [16,17]. Some research has examined governance challenges in specific jurisdictions and evaluated early-stage subnational initiatives across various countries [18,19,20]. However, a significant gap exists in synthesizing knowledge across diverse contexts to understand the comprehensive opportunities and challenges of subnational REDD+ implementation.

Previous reviews about REDD+ have largely concentrated on isolated domains such as finance or community aspects. Bayrak et al. [21] reviewed the REDD+ impact on forest-dependent communities, focusing on four dimensions, which are institutional, environmental, socio-cultural, and livelihoods. Morita and Matsumoto [22] identified and evaluated the financial challenges of REDD+ both within the UNFCCC and outside the UNFCCC framework, while analyzing their governance. The existing literature has yet to address holistic analyses that integrate multiple dimensions of subnational REDD+. Moreover, there remains a significant research gap regarding scale-specific analyses of REDD+.

To systematically address the complex nature of subnational REDD+ implementation, this review adopts a structured analytical framework. Also, it aims to identify both challenges and opportunities regarding the various aspects. In this context, research objectives are (1) define and clarify the concepts of subnational and jurisdictional REDD+, (2) identify the key elements of implementing subnational REDD+, and (3) review the opportunities and challenges from subnational REDD+.

2. Materials and Methods

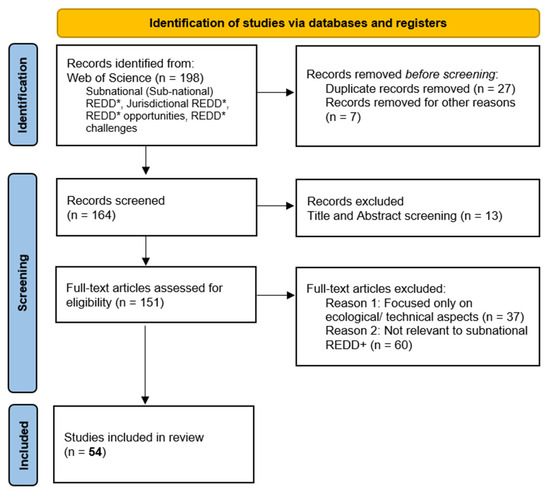

This study employed a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify the key elements of subnational REDD+ and examine their opportunities and challenges (Figure 1). To this end, literature published between 2005, when REDD was first introduced at COP11, through January 2024 was searched in the Web of Science Core Collection databases using keywords such as “subnational REDD*”, “sub-national REDD*”, “REDD* challenges”, “REDD* opportunities”, and “jurisdictional REDD*”.

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review process based on PRISMA 2020.

The search yielded a total of 198 articles. Following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for literature selection, a two-stage screening process was conducted by two independent reviewers. In the first stage, the reviewers screened the abstracts to identify studies that aligned with the research objectives. In the second stage, the reviewers conducted a full-text review of the potentially eligible studies, of which 54 were selected as relevant to the study’s objectives. The selected literature comprised peer-reviewed academic articles and reports that addressed REDD+ implementation at the subnational or jurisdictional level. Our review focused primarily on English-language publications, as some relevant literature in other languages from non-Anglophone REDD+ implementing countries may not be represented.

Data extraction and analysis employed qualitative content analysis, examining and categorizing key challenges and opportunities. Based on the analysis, strategic approaches to overcome these challenges and leverage the opportunities of subnational REDD+ implementation were proposed. This study aims to provide a systematic understanding of the complexities of subnational REDD+ implementation and offer information for effective design and implementation.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Subnational REDD+

3.1.1. Defining Subnational and Jurisdictional Approaches

Despite the absence of official UNFCCC definitions for the terms “subnational” and “jurisdictional”, these terms are often used interchangeably in the literature. The debate around the scale has been discussed across numerous countries [6]. This section aims to establish precise definitions for these terms, thereby providing a foundation for the interpretation of REDD+ at various scales.

In UNFCCC decisions, subnational approaches are regarded as interim measures toward national-scale REDD+ implementation. It would be allowed for developing countries to establish subnational forest reference emission levels and/or forest reference levels according to the national circumstances. These subnational approaches are considered demonstration activities or strategic tools to support achieving national REDD+ [6]. The UN-REDD Programme provides two interpretations of the term “subnational”. First, it can refer to administrative units, such as federal states, provinces, or districts, that are smaller than the national level but are larger than individual projects. Also, it can describe ecological regions, such as the Amazon biome [23,24]. These interpretations reflect the different and diversified governance structures and ecological conditions across countries, providing flexibility for developing countries to adapt REDD+ to their different contexts.

The term “jurisdictional” refers to programs implemented at subnational and/or country-wide scales, covering over several million hectares and administered by governments as part of broader national and sectoral policies. In other words, jurisdictional approaches can incorporate both subnational and national jurisdictions. The FCPF Carbon Fund, for instance, supports Emission Reduction (ER) programs implemented at a jurisdictional scale, which is defined as a geographic area comprising one or more administrative units [25]. Jurisdictional approaches are recognized for their potential to generate high-quality and high-integrity carbon credits that comply with UNFCCC decisions. However, a lack of clear guidelines regarding jurisdictional approaches exists. Further refinement of the jurisdictional approach is necessary to effectively connect projects, subnational levels, and ultimately national levels. Within the UNFCCC framework, it is crucial to establish precise guidelines for consistent quantification, monitoring, and equitable distribution of benefits across various levels [26].

Additionally, some leading carbon standards have established specific criteria regarding the jurisdictional/subnational scale. For example, ART-TREES accepts subnational areas no more than one administrative level below the national level and requires a minimum area of 2.5 million hectares. Similarly, the JNR stipulates that the lowest eligible jurisdictional level is the second administrative level below the national level. These criteria ensure that subnational and jurisdictional approaches align with larger-scale jurisdictional and national strategies.

For consistency, this paper adopts the term “subnational” to refer to administrative units below the national level, while recognizing the overlapping usage of terminology in the literature.

3.1.2. Current Status of Subnational REDD+ Implementation

Subnational REDD+ is increasingly recognized as an essential framework for implementing scalable and robust carbon initiatives. To facilitate its implementation, several prominent carbon standards provide structured methodologies and eligibility criteria, including Verra’s JNR, ART-TREES, and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) Carbon Fund.

As of December 2024, a total of 43 jurisdictional programs have been registered in each of the following registries: 24 programs in ART-TREES [27], 4 programs in JNR [28], and 15 programs in FCPF CF [29]. The regional distribution spans 29 countries, highlighting a global commitment to jurisdictional-level forest carbon initiatives. Specifically, 12 countries in America, 10 countries in Africa, and 5 countries in Asia have actively participated in developing jurisdictional programs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Regional distribution of programs.

Across all countries, these REDD+ programs average 13.45 million hectares in size, ranging from 1.7 million to 84.1 million hectares. Most projects are structured at the level of local administrative areas, though national-level projects are also underway in Costa Rica, Guyana, Ecuador, Papua New Guinea, Gabon, Ethiopia, Uganda, and the Dominican Republic under the FCPF. The majority of project developers are government entities responsible for forestry and environmental management. While few programs have yet produced final emission reduction results due to their relatively early implementation stages, they will contribute meaningful progress toward national REDD+ targets and climate goals.

3.2. Conceptual Framework: Opportunities and Challenges for Subnational REDD+

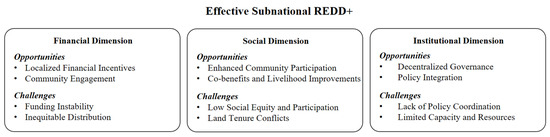

The subsequent section offers a comprehensive analysis of key elements of subnational REDD+ based on a systematic review of the core literature published since 2005. Through this initial review, we identified three critical elements: (1) financial; (2) social; and (3) institutional dimensions. Based on the key elements, we conducted a thorough review of the opportunities and challenges for subnational REDD+. They served as a robust framework for analyzing the opportunities and challenges associated with subnational REDD+.

3.2.1. Financial Dimension

Financial stability plays a crucial role in determining both the feasibility and sustainability of successful REDD+ implementation. Funding for REDD+ comes from bilateral and multilateral agreements, as well as public, private, international, and domestic resources [22]. These diverse funding sources hold considerable potential to enhance the effectiveness of REDD+ at the subnational level, but they also present significant challenges that can impede progress if not adequately managed.

Based on this review, the financial opportunities of implementing subnational REDD+ include providing localized incentives and attracting local participation and private investments. Nevertheless, several challenges persist, such as instability and unpredictability of funding flows, inequities in benefit distribution, and the heavy reliance on external funding.

Financial Opportunities

One of the main opportunities for subnational REDD+ lies in designing financial incentives suitable for local economic conditions and environmental priorities. Localized financial management aligns funding structures with the specific community needs, ensuring that resources are used effectively. A study of Brazil’s Acre region provides a valuable example demonstrating the importance of prioritizing cost-effective carbon reduction initiatives to maximize financial efficiency. Such strategic resource allocation enables policymakers to achieve significant environmental benefits even with constrained funding [30]. This flexibility in localized financial management can provide another advantage by attracting private investment at the subnational level. It reduces financial risk and encourages participation from investors who may prefer subnational and project-level involvement over national plans [31]. The financial mechanisms adapted to specific regional contexts become not only more appealing for diverse funding sources but also more effective in spending the budget, ultimately creating sustainable long-term financing for forest conservation efforts.

Furthermore, establishing a performance insurance mechanism represents a promising solution at the subnational level, particularly in contexts where performance risks and limited financial capacity constrain REDD+ implementation [32]. Such mechanisms can help mitigate jurisdictional performance risks, encouraging jurisdictions to pursue more ambitious emission reduction targets. Additionally, by reducing financial uncertainty, performance insurance can enhance private sector engagement and catalyze increased investment in jurisdictional REDD+ programs. This approach is further strengthened through the development of performance buffers, which facilitate credit supply and contribute to the long-term sustainability of large-scale forest conservation and climate mitigation initiatives.

In addition to localized financing, another important financial opportunity is incentivizing community engagement through well-structured benefit-sharing mechanisms. When implemented effectively, benefit-sharing frameworks provide fair compensation to local and indigenous peoples for their contributions, fostering equity and strengthening support for REDD+ initiatives [33]. Structured mechanisms enhance community engagement and empowerment, ensuring that revenues from carbon credits or other ecosystem services are directed toward local communities. Empirical evidence indicates that community participation plays a pivotal role in protecting forest resources, engaging in intensive fire monitoring, and managing livestock or rotational grazing. To improve the efficacy of REDD+, community forest units aligned with local forest management goals merit consideration [34]. The function of subnational institutions holds significant importance in determining the capacity of community-based forest user groups to address both domestic forestry requirements and global carbon demand.

Among various means to induce community participation, direct distribution to local beneficiaries can be the most effective, efficient, and equitable. However, to materialize it, local institutions and communities should have the capacity to handle the potential risks, supported by a well-established safeguard system [35]. Financial instruments have been demonstrated to positively influence not only local communities but also private sector engagement in forest-based emission reduction activities. The case of Indonesia highlights the use of formal and informal fiscal instruments and various incentive methods at multiple jurisdictional levels. It is imperative for governments to implement a mixed approach that combines different financial instruments to meet stated objectives while addressing the demands of stakeholders [36].

Financial Challenges

A substantial challenge in the implementation of REDD+ is the lack of stability and reliability of funding. Globally, a significant number of REDD+ initiatives heavily depend on external funding sources, which are prone to unpredictability and inconsistency [37]. Variability in funding flows can disrupt REDD+ activities and jeopardize long-term forest conservation goals. Research indicates that many organizations involved in REDD+ covered costs not fully accounted for by project budgets, with subnational governments bearing significant financial burdens during the planning phases of REDD+ [38]. A critical factor contributing to this instability is the failure of developed countries to meet initial financial commitments for REDD+ and to provide sufficient funding to ensure the full and effective implementation of REDD+ for their recipients [37]. Ensuring sustainable and stable funding is crucial not only for implementing REDD+ activities but also for maintaining consistent livelihoods for local communities participating in the initiatives, fostering their engagement, and establishing secure land tenure [39].

A further challenge lies in the equitable distribution of REDD+ benefits. Disparities often emerge between the parties burdened with the financial obligations of forest conservation and those who benefit from the resultant outcomes. These imbalances have the potential to give rise to conflicts and result in a decline in local support for REDD+ [40]. To address these inequities, the establishment of robust governance structures is required. However, studies have identified deficiencies in governance capabilities, including insufficient tools for communication between governments and communities, weak institutional capacity within government agencies, and limited mechanisms to ensure proper benefit distribution. Moreover, research by [41] highlights that countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and Nepal possess technical expertise, financial support, and national-level operational institutions for REDD+ implementation, but frequently lack the institutional governance capacity necessary to implement effective benefit-sharing mechanisms. Addressing these gaps is imperative to ensure the success of REDD+ initiatives in achieving their intended outcomes.

3.2.2. Social Dimension

REDD+ initiatives have been developed to incorporate safeguards that protect the rights and interests of local communities and indigenous peoples, aiming to minimize any adverse environmental, social, or economic impacts arising from REDD+ activities. The seven core elements of REDD+ safeguards include respecting community rights and knowledge, obtaining their active participation and consent, and establishing governance frameworks that ensure the involvement of all relevant stakeholders. These safeguards emphasize not only climate change mitigation efforts but also the welfare of local communities and the responsible implementation of REDD+ [42]. While this subnational REDD+ can give opportunities to enhance community participation and contribute to their social co-benefit and livelihood, challenges such as low social equity, limited participation, and conflicts over land and resources still exist.

Social Opportunities

At the subnational level, REDD+ offers enhanced opportunities to engage communities more effectively in planning and decision-making processes, fostering responsibility and accountability toward REDD+ objectives. It is imperative, therefore, to establish avenues for local participation, and it can serve as a key determinant of long-term success [43]. For instance, in Brazil’s Acre region, a technical advisory committee led by indigenous representatives has been institutionalized, granting the committee decision-making authority over benefit-sharing and ensuring that local perspectives are integrated into policy processes. Similarly, Peru has established platforms for coordination and dialogue between the government and indigenous groups, including formal REDD+ meetings and representative organizations [44].

Particularly, incorporating indigenous knowledge into the design of policies and incentives is beneficial, as it ensures that the needs of local communities are met. This approach has been demonstrated to promote sustainability and enhance outcomes [45]. Moreover, providing local stakeholders with direct platforms to articulate their perspectives during decision-making processes fosters inclusivity and ensures that REDD+ activities respect and integrate traditional practices [46]. However, challenges persist in ensuring that the participation of indigenous peoples and communities is effectively reflected in policy outcomes. In Mexico, for example, state-level REDD+ committees exist but often lack mandatory influence in decision-making processes, resulting in unidirectional information flows rather than genuine consultation [47].

Beyond participation, the implementation of subnational REDD+ has demonstrated strong potential to generate social co-benefits, particularly in improved livelihoods, enhanced social stability, and increased access to resources for local communities [43]. For instance, programs in Brazil have provided financial incentives to support local livelihoods, guaranteed land tenure, and developed education and capacity-building initiatives to enhance resource management skills. In Tanzania, conditional incentives have successfully motivated local participation in REDD+ and improved land-use practices. These social co-benefits contribute to economic stability, poverty alleviation, and overall community well-being [48]. Furthermore, REDD+ initiatives have also demonstrated their potential to improve community members’ quality of life through job creation, support for sustainable agricultural practices, and infrastructure development [49].

A notable example, supported by the Amazon Fund, demonstrates how farmers and livestock producers in a specific region of Brazil have experienced significant benefits from diverse sources. These include increased production of key commodities such as honey and milk, and the enhancement of local livelihoods. Among these benefits are the securing of land tenure, registration in Brazil’s Environmental Rural Registry (CAR), and acquisition of land title certificates [50].

Social Challenges

Despite its potential, the implementation of subnational REDD+ faces several challenges, particularly regarding equity and the effective participation of local organizations. In some cases, communities perceive themselves as experimental subjects under controlled initiatives, pointing to top-down rules, meaningless plans, and exclusion from decision-making processes [51]. Additionally, insufficient attention to gender equality and women’s rights has been identified as a gap in REDD+ projects. This oversight can adversely affect women’s quality of life in participating communities, underscoring the need to integrate gender considerations into initiative design and empower women through active participation in decision-making [52].

To ensure informed and voluntary participation in REDD+ activities, the concept of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) has been introduced. However, implementation gaps remain. For instance, in Vietnam, discrepancies between promised and delivered financial benefits have eroded community trust and participation, creating economic difficulties for local residents who depend on forest-based livelihoods [53]. Such situations risk exacerbating poverty if economic benefits fail to offset income losses from reduced forest use. To address these issues, REDD+ programs must manage community expectations realistically, improve economic compensation mechanisms, and ensure livelihood security through a comprehensive approach.

In addition to participation-related concerns, conflicts over land and resource rights represent another major social barrier to effective REDD+ implementation. Although securing land tenure is a fundamental requirement for REDD+ implementation, empirical evidence suggests that initial REDD+ initiatives have made limited progress in addressing tenure instability. Existing stakeholders in land-use decision-making—including central governments, corporations, and others—frequently assume a leading role in these processes and have been identified as a primary cause of land tenure insecurity. To address this issue, it is imperative to strengthen collective efforts from civil society [33,54].

In countries like Brazil and Indonesia, challenges such as the absence of formal ownership and weak documentation have been noted. Brazil, however, has introduced institutional measures to address these issues, including formalizing ownership of illegally occupied public land and establishing a system to register rural property information. These steps have improved tenure clarity, promoted compliance with forest laws, and facilitated REDD+ implementation while providing communities with secure land ownership [55].

3.2.3. Institutional Dimension

REDD+ necessitates the establishment of foundational structures for implementation, comprising national strategies and action plans, robust monitoring systems, and safeguards. Transparent and accountable implementation and reporting require strong governance structures that promote collaboration between government institutions and stakeholders. Aligning the institutional framework with international and national policies is critical for contributing to global emission reduction goals through REDD+ initiatives.

Institutional Opportunities

Subnational REDD+ offers prospects to enhance local governance by decentralizing responsibilities and empowering local governments. By providing resources and capacity-building opportunities, subnational REDD+ can improve the functionality of local governments and achieve effective decentralization. Strengthened governance at the local level enables active participation in REDD+ activities and fosters more efficacious forest resource management through community involvement [18,46,56].

A notable example of decentralization is evident in Brazil. Its federal system allocates authority and responsibilities between the national government and states, allowing states to legislate on environmental issues as long as they do not conflict with federal laws. This autonomy empowers states to design and implement REDD+ policies specific to their local demands and circumstances, establishing the legal frameworks necessary for effective implementation. Research indicates that state government perspectives, trust in economic incentives, and awareness of the REDD+ carbon market significantly influence the selection and motivation for REDD+ initiatives. According to [57], Brazil’s decentralized governance structure enables subnational governments to take a leading role in climate action, while simultaneously facilitating collaboration with local and transnational actors. Furthermore, recent studies highlight the significance of localized approaches to tackling deforestation, emphasizing the need to account for the diversity of local conditions, such as agricultural practices, land use, and drivers of deforestation, rather than imposing uniform targets or expectations across jurisdictions [58,59]. Subnational REDD+ offers a more localized understanding of deforestation factors, enabling effective and targeted interventions.

The extent of authority held by sub-national governments varies across countries. For instance, countries such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and Peru have subnational governmental institutions with various powers to directly carry out activities aimed at reducing deforestation [60]. While differences exist between countries, there is also variation in the level of authority granted to subnational governments within a single country. In the case of Indonesia, the assessment of emission reduction levels was conducted at the subnational government levels, including the province, district, and village. The study found that emission reductions were more substantial at the provincial level compared to the district level. This observation suggests that leveraging the provincial level of governance could be a more effective approach when pursuing substantial outcomes in the context of REDD+ implementation [61]. The active involvement of subnational governments in REDD+ implementation not only leads to enhanced emission reductions but also facilitates the integration of climate change mitigation and adaptation policies [62].

Subnational REDD+ not only enhances local governance but also serves as a vehicle for integrating REDD+ with existing regional policies and development plans. This integration improves policy coherence and creates synergies for more sustainable land use [63,64]. For instance, the integration of REDD+ with agricultural policies can concurrently encourage forest conservation and sustainable farming practices, achieving environmental and development goals. A prominent example is Ghana’s Cocoa Forest REDD+ Program, which seeks to mitigate deforestation linked to cocoa production by incorporating climate-smart cocoa practices into forest management strategies. This integrated approach fosters collaboration between the agricultural and forestry sectors [65]. A similar approach can be observed in the linkage of subnational REDD+ with zero-deforestation supply chain policies, strategically aligning corporate practices with initiatives such as the European Union Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR) [66,67]. By sourcing products from jurisdictions implementing REDD+ programs and utilizing government monitoring systems, corporations can effectively reduce costs while addressing deforestation concerns. Moreover, sustained support for local communities can resolve land conflicts and build partnerships between corporations and Indigenous peoples or local stakeholders [66].

The implementation of REDD+ has the potential to generate additional benefits through its integration with existing community forest institutions, thereby revitalizing local forest management systems. In developing countries with well-developed community forest policies, REDD+ can be strategically employed to enhance local livelihoods, achieve forest-related objectives, and address international carbon demand by leveraging existing local governance and institutional framework [34]. Strategic policy integration can optimize budget efficiency and effectively accelerate the achievement of global climate targets.

Institutional Challenges

Despite its potential, subnational REDD+ is confronted with challenges related to coordination across governance levels and maintaining policy coherence. The involvement of various institutions and actors often gives rise to vertical misalignment between national and local governments and horizontal conflicts among sectors, such as forestry and agriculture. These challenges have the potential to undermine the overall effectiveness of REDD+ implementation [56]. For instance, Mexico has encountered difficulties in achieving vertical policy coordination between national and local governments and horizontal alignment across sectors [68]. To address these issues, it is essential to establish clearly defined objectives and conduct a thorough analysis of potential impacts on diverse stakeholder groups are essential at both the national and local levels.

The level of decentralization varies by country, and in developing countries, complicated laws and regulations often lack consistency across policy departments or governance levels, leading to ambiguity. The challenges posed by inadequate administrative capacity and lax law enforcement further impede the efficacy of governance processes [69]. Even in Brazil, where subnational REDD+ is most representative and actively implemented, challenges arise. These challenges have been identified as key issues, including the lack of REDD+ plans at the subnational level, limited transparency, and insufficient representation of traditional and indigenous communities [70]. Additionally, the existence of discrepancies in the understanding of responsibilities and transformation between subnational and national entities, in conjunction with inadequate communication, is identified as a significant contributing factor to the impediment of policy coherence [71].

While aligning policies is essential, the success of subnational REDD+ also depends on the institutional strength of local governments. Subnational governments tend to lack the institutional capacity and resources necessary for the effective implementation and management of REDD+. These challenges encompass a lack of technical expertise, financial resources, and administrative capabilities, as well as inadequate coordination between different levels of government [56,72,73,74]. In Vietnam, lower-tier local governments have been found to have limited authority and to lack the material and human resources necessary for effective implementation. Also, land use planning is centrally managed, which restricts decision-making power at the local level [56]. Political changes, policy shifts, and radical institutional reforms create additional obstacles to sustained REDD+ implementation. Political instability and leadership transitions disrupted progress on REDD+ initiatives, underscoring the need for stable governance frameworks [75].

Weak local governance poses a substantial threat to the long-term sustainability of projects, and existing indigenous organizations face challenges due to a lack of the capacity and resources necessary to manage climate funds. Moreover, the absence of adequate funding and explicit accountability assigned to local administrations following the decentralization exacerbates existing challenges, including unstable land tenure issues, diminished interaction with the central government, and pervasive corruption. A comprehensive analysis of conflicts of interest at various levels is imperative to identify and address these challenges. Existing local governance structures must be supplemented to establish both vertical and horizontal connections with the central government and communities [76,77].

4. Discussion

4.1. Conceptual Distinction and Implementation Status

A comparison of the subnational and jurisdictional approaches reveals notable distinctions in their application. While both approaches operate at scales between national frameworks and local projects, the subnational approach typically focuses on defined administrative units or ecological regions. In contrast, the jurisdictional approach may encompass broader governance structures at various levels. Despite these conceptual differences, both approaches have been implemented across various countries using multiple carbon standards such as ART-TREES and JNR. Despite its numerous advantages over smaller-scale REDD+ projects, subnational REDD+ is a more complex undertaking, considering a broad range of factors. This complexity is demonstrated by the current prevalence of project-level activities over subnational ones.

4.2. Interdependencies Between REDD+ Dimensions

Our analysis identified interactions among financial, social, and institutional dimensions and discussed critical interdependencies that determine the effective, efficient, and equal implementation of subnational REDD+ (Figure 2). Understanding these relationships is essential for developing integrated approaches that address challenges effectively.

Figure 2.

A summary of opportunities and challenges of subnational REDD+.

Financial stability significantly influences both social and institutional dimensions. Consistent funding enhances community engagement, promotes equitable benefit-sharing, and strengthens local institutional capacity. Additionally, a robust institutional framework is a prerequisite for equitable finance allocation and stakeholder participation. Successful implementation requires positive reinforcement across all dimensions, where well-established institutional arrangements improve financial management, subsequently enhancing social outcomes.

When institutional capacity is deficient, financial resources become inefficiently distributed while social safeguards fail to be properly implemented. It aligns with Loft et al. [78], who demonstrated that capable local governments can significantly enhance transparency and effectiveness in the finance allocation and distribution. Similarly, Wong et al. [79] found that institutional capacity deficits directly impeded financial sustainability in jurisdictional programs. When subnational governments fail to manage funds effectively, international donors and investors hesitate to provide long-term commitments, creating a cycle where institutional limitations perpetuate financial instability. Strengthening institutional frameworks is therefore essential for improving financial governance and fostering equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms. The findings highlight the intrinsic connection between social participation and benefit-sharing. In cases from Vietnam, inequitable distribution of financial benefits to local stakeholders diminished community trust and participation, ultimately undermining program effectiveness [80]. Indeed, the effectiveness of benefit-sharing mechanisms depends significantly on social legitimacy among local communities [81]. Consequently, effective benefit-sharing mechanisms require meaningful community participation through an equitable process to ensure legitimacy and sustainability [82].

Enhanced social participation not only increases community acceptance of financial mechanisms but also improves overall REDD+ program efficiency and equity. Social legitimacy thus represents a critical factor in long-term REDD+ initiative success. The relationship between institutional structures and social participation creates significant feedback loops influencing REDD+ outcomes. Effective decentralization enhances community engagement by providing accessible participation platforms. Strengthened community involvement subsequently improves institutional accountability [83]. However, as demonstrated in Mexico and Indonesia [84,85], policy incoherence between national and subnational levels can disrupt these positive feedback loops. When policies across governance levels are misaligned, they generate uncertainty, undermining both financial management and social engagement, which ultimately delays climate change adaptation efforts [86,87]. Our findings suggest a more dynamic, bidirectional relationship between institutional structures and community participation, as evidenced by the previous case that early community involvement in institutional design significantly enhanced program legitimacy and effectiveness in Brazil’s jurisdictional initiatives [88].

This integrated analysis underscores the necessity of a holistic approach to subnational REDD+ implementation. Financial, social, and institutional factors should not be treated as isolated components but addressed as interconnected elements within a broader framework. Developing adaptive, context-specific strategies that account for these interdependencies is critical for enhancing long-term REDD+ program effectiveness.

4.3. Policy Implications and Future Research Directions

To secure financial stability, a blended approach that combines sustained international financial support with private sector investment is essential. Discussions on introducing blended finance in forest carbon projects, including REDD+, have continued [22,89], highlighting how government and international organizations can offer risk-reducing points about the investment while the private sector can gain financial returns [90]. While leveraging public funds to attract private investment, it can simultaneously promote sustainable forest management and equitable benefit sharing [91]. For effective and equal utilization of the finance, a robust financial system should be designed to directly reward conservation performance and guarantee that local communities receive tangible benefits. As a pragmatic measure, the integration of domestic financial instruments can be contemplated [78]. Also, the establishment of a transparent benefit-sharing system is crucial to ensure the allocation of both monetary and non-monetary benefits.

To enhance social dimensions, institutionalized foundations that enable participation from multiple stakeholders are necessary, such as advisory committees and meetings with decision-making authority [92,93]. Furthermore, gender equality and women’s empowerment should be integrated into decision-making processes to ensure inclusive and equitable policy implementation [94]. In particular, to address land ownership issues, which represent the most frequent conflicts with local residents, tenure security initiatives that formalize land rights as the foundation for REDD+ implementation must be established [33]. The continuous and active participation of indigenous peoples and local communities is the most crucial factor in enhancing project sustainability, which in turn contributes to the objective of reducing deforestation.

Institutionally, subnational REDD+ initiatives can strengthen local government capacity through decentralization, enabling the development and implementation of forest conservation policies tailored to local conditions [95,96]. To optimize the benefits of decentralized systems, clearly defining the roles and responsibilities between central and local governments is crucial. This requires comprehensive capacity-building efforts for subnational government, including technical, administrative, and governance capabilities. Moreover, ensuring policy coherence contributes to preventing administrative redundancies and utilizing limited budgets efficiently [97,98]. Integrating REDD+ strategies with existing national and local agricultural and forestry policies is crucial for enhancing implementation transparency and consistency.

Our study offers valuable insights into subnational REDD+ implementation; however, several limitations should be considered. First, our analysis relies primarily on published academic literature, potentially overlooking insights from gray literature and practitioner experiences. Second, the financial, social, and institutional opportunities and challenges identified in this paper are not exclusively characteristic of subnational REDD+ but may also emerge in projects or national-level implementations. Given that subnational approaches often function as a strategic demonstration for national-scale expansion, more diverse analyses are required. To design and implement subnational REDD+ effectively, it is essential to thoroughly examine the specific challenges faced by each country and to develop appropriate response strategies. Moreover, well-structured subnational initiatives can positively influence the success of national-level REDD+ implementations.

5. Conclusions

This study synthesizes the existing literature on subnational REDD+ implementation by identifying key opportunities and challenges across financial, social, and institutional dimensions. A systematic review reveals that these three dimensions are deeply interconnected and significantly influence the effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of REDD+ implementation. The conceptual framework presented emphasizes that challenges in one dimension can hinder progress in others, whereas strategic interventions have the potential to create positive cascading effects across multiple dimensions.

Our analysis offers several important insights for understanding subnational REDD+: First, subnational REDD+ presents distinct advantages by linking local implementation with national frameworks. This positioning allows for interventions that are more tailored to local contexts than national approaches while offering greater coordination potential than project-level initiatives. However, this intermediary position also creates governance challenges, particularly concerning vertical and horizontal policy coordination. Second, financial sustainability is heavily dependent on institutional structures that ensure transparency, accountability, and equitable benefit-sharing. When these structures are weak, financial instability persists regardless of funding mechanisms. Conversely, well-established institutional arrangements can align stakeholder incentives and enable the efficient use of limited resources to achieve meaningful outcomes. Finally, meaningful community participation is not merely a social safeguard but a fundamental determinant of program effectiveness. Our analysis indicates that subnational initiatives with institutionalized participation mechanisms consistently demonstrate stronger performance in terms of financial efficiency and institutional legitimacy.

Considering the interdependence among financial, social, and institutional dimensions, designing and implementing these initiatives with an integrated approach can generate substantial benefits for the climate, forests, and local communities. Moving forward, policymakers should adopt an integrated strategy that recognizes these interdependencies while remaining sensitive to local contexts. Through strategic design and implementation, subnational REDD+ can serve as an effective bridge between local actions and national frameworks, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and equitable forest governance and advancing the global zero-deforestation goal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.J. and J.K.; methodology, Y.J.; investigation, Y.J.; data curation, Y.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.J.; writing—review and editing, Y.J. and J.K.; visualization, Y.J.; supervision, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea Forest Service.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. FRA 2020 Remote Sensing Survey; FAO Forestry Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; No. 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD Programme. REDD+ Academy Learning Journal; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Decision 1/CP.16: The Cancun Agreements: Outcome of the Work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Long-Term Cooperative Action Under the Convention; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, D.; Scriven, J.; Jonckheere, I.; Laughlin, J.; Todd, K. Toward REDD plus Implementation. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmadja, S.K.M.; Alusiola, R.; Barboza, I.; Sartika, L.; Theresia, V.; Simonet, G. The International Database on REDD+ Projects and Programs Linking Economics, Carbon and Communities (ID-RECCO)—Project Tables, V.5.0. Available online: https://www.reddprojectsdatabase.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Streck, C. REDD plus and leakage: Debunking myths and promoting integrated solutions. Clim. Policy 2021, 21, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.A.; Börner, J.; Sills, E.O.; Kontoleon, A. Overstated carbon emission reductions from voluntary REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24188–24194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenfield, P. Revealed: More than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows. Guardian 2023, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A.; Martius, C.; De Sy, V.; Duchelle, A.E.; Larson, A.M.; Thuy, P.T. Transforming REDD; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Climate focus. The Why and How of Subnational REDD+; Climate Focus: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvera. A Comprehensive Guide to Jurisdictional REDD+; Sylvera: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Secretariat, A. The REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard (TREES), Version 2.0; TREES: Arlington, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Verra. JNR Program Guide, v4.1; Verra: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; updated 19 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, A.B.; Duchelle, A.E.; Angelsen, A.; Avitabile, V.; De Sy, V.; Herold, M.; Joseph, S.; de Sassi, C.; Sills, E.O.; Sunderlin, W.D.; et al. Comparing methods for assessing the effectiveness of subnational REDD plus initiatives. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 074007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, F.; Asner, G.P.; Joseph, S. Advancing reference emission levels in subnational and national REDD+ initiatives: A CLASlite approach. Carbon Balance Manag. 2015, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, A.; Larson, A.M.; Duchelle, A.E.; Myers, R.; Tovar, J.G. Multilevel governance challenges in transitioning towards a national approach for REDD plus: Evidence from 23 subnational REDD plus initiatives. Int. J. Commons 2015, 9, 909–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, W.; Stickler, C.; Duchelle, A.E.; Seymour, F.; Nepstad, D.; Bahar, N.H.; Rodriguez-Ward, D. Jurisdictional Approaches to REDD+ and Low Emissions Development: Progress and Prospects; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Ekaputri, A.D.; Sills, E.O.; Duchelle, A.E.; Kweka, D.; Diprose, R.; Doggart, N.; Ball, S.; Lima, R.; Enright, A. The Challenge of Establishing REDD+ on the Ground: Insights from 23 Subnational Initiatives in Six Countries; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014; Volume 104. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak, M.M.; Marafa, L.M. Ten Years of REDD plus: A Critical Review of the Impact of REDD plus on Forest-Dependent Communities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, K.; Matsumoto, K. Challenges and lessons learned for REDD+ finance and its governance. Carbon Balance Manag 2023, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-REDD Programme. REDD+ Key Terms Glossary; Technical Resource Series 3; UN-REDD Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, D.; Todd, K.; Scriven, J.; Guay, B.; Hugel, B. Towards a Common Understanding of REDD+ Under the UNFCCC; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Annual Report 2024; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R.; Hargita, Y.; Günter, S. Insights from the ground level? A content analysis review of multi-national REDD+ studies since 2010. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 66, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ART Architecture for REDD+ Transactions. ART Registry. Available online: https://artredd.org/art-registry/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Verra. Verra Registry. Available online: https://registry.verra.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Bank, W. Carbon Assets Tracking System. Available online: https://cats.worldbank.org/?tab=AboutCats (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Palmer, C.; Taschini, L.; Laing, T. Getting more ‘carbon bang’ for your ‘buck’ in Acre State, Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, L.; Dutschke, M.; Streck, C.; Porrúa, M.E. Creating incentives for avoiding further deforestation: The nested approach. Clim. Policy 2009, 9, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.K.; Golub, A.; Lubowski, R. Performance insurance for jurisdictional REDD plus: Unlocking finance and increasing ambition in large-scale carbon crediting systems. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1062551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; de Sassi, C.; Sills, E.O.; Duchelle, A.E.; Larson, A.M.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Awono, A.; Kweka, D.L.; Huynh, T.B. Creating an appropriate tenure foundation for REDD plus: The record to date and prospects for the future. World Dev. 2018, 106, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.P.; Shyamsundar, P.; Nepal, M.; Pattanayak, S.K.; Karky, B.S. Costs, cobenefits, and community responses to REDD plus: A case study from Nepal. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyudi, R.; Marjaka, W.; Silangen, C.; Fajar, M.; Dharmawan, I.W.S.; Mariamah. Effectiveness, efficiency, and equity in jurisdictional REDD+ benefit distribution mechanisms: Insights from Jambi province, Indonesia. Trees For. People 2024, 18, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T.; Sarker, T.; Muttaqin, Z.; Nurfatriani, F.; Salminah, M.; Maraseni, T. The role of fiscal instruments in encouraging the private sector and smallholders to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation: Evidence from Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodoin, S.; Mason-Case, S. What difference does CBDR make? A socio-legal analysis of the role of differentiation in the transnational legal process for REDD+. Transnatl. Environ. Law 2016, 5, 255–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, C.; Sills, E.; Aryani, R.; Ekaputri, A.D.; Evinke, M.F. Beyond opportunity costs: Who bears the implementation costs of reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation? Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2018, 23, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Atmadja, S.S.; Chervier, C.; Komalasari, M.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Sills, E.O. Can REDD+ succeed? Occurrence and influence of various combinations of interventions in subnational initiatives. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2024, 84, 102777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, R.; Moutinho, P. Challenges of Sharing REDD plus Benefits in the Amazon Region. Forests 2020, 11, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, T.; Corbera, E. Incentivizing REDD plus: How developing countries are laying the groundwork for benefit-sharing. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 63, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchelle, A.E.; Jagger, P. Operationalizing REDD+ Safeguards; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wunder, S.; Duchelle, A.E.; Sassi, C.D.; Sills, E.O.; Simonet, G.; Sunderlin, W.D. REDD+ in Theory and Practice: How Lessons From Local Projects Can Inform Jurisdictional Approaches. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiano, M.; Stickler, C.; David, O. How Can Jurisdictional Approaches to Sustainability Protect and Enhance the Rights and Livelihoods of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities? Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, M.; Hoelle, J.; Medeiros, M.; Tavares, A. Forest Policy Innovation at the Subnational Scale: Insights from Acre, Brazil. Conserv. Soc. 2023, 21, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidone, F. Investigating forest governance through environmental discourses: An Amazonian case study. J. Sustain. For. 2023, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.A.; Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; Ceballos, G.C.O.; Binnqüist, C.L.; Cerdán, C.R. Mixed Effectiveness of REDD plus Subnational Initiatives after 10 Years of Interventions on the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Forests 2020, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poffenberger, M. Restoring and Conserving Khasi Forests: A Community-Based REDD Strategy from Northeast India. Forests 2015, 6, 4477–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallemore, C.T.; Prasti, H.R.D.; Moeliono, M. Discursive barriers and cross-scale forest governance in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.; Cisneros, E.; Börner, J.; Pfaff, A.; Costa, M.; Rajdo, R. Evaluating REDD plus at subnational level: Amazon fund impacts in Alta Floresta, Brazil. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 116, 102178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.J.P.; Hyldmo, H.D.; Prasti, H.R.D.; Ford, R.M.; Larson, A.M.; Keenan, R.J. Guinea pig or pioneer: Translating global environmental objectives through to local actions in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia’s REDD plus pilot province. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2017, 42, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.M.; Solis, D.; Duchene, A.E.; Atmadja, S.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Dokken, T.; Komalasari, M. Gender lessons for climate initiatives: A comparative study of REDD plus impacts on subjective wellbeing. World Dev. 2018, 108, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P.; Thi Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, D.V.; Tran, N.H.; Le, H.V.T.; Nghiem, T.P.; Thi Vu, H.D. Using REDD+ policy to facilitate climate adaptation at the local level: Synergies and challenges in Vietnam. Forests 2016, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Larson, A.M.; Barletti, J.P.S. Land and Carbon Tenure; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.D.; Sills, E.O.; Duchelle, A.E.; Ekaputri, A.D.; Kweka, D.; Toniolo, M.A.; Ball, S.; Doggart, N.; Pratama, C.D.; Padilla, J.T.; et al. REDD plus at a critical juncture: Assessing the limits of polycentric governance for achieving climate change mitigation. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert-Amico, A.; Larson, A.M. Forestry Decentralization in the Context of Global Carbon Priorities: New Challenges for Subnational Governments. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueiros, C.; Jodoin, S.; McDermott, C.L. Jurisdictional approaches to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in Brazil: Why do states adopt jurisdictional policies? Land Use Policy 2023, 127, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.; Piketty, M.-G.; Poccard-Chapuis, R.; Brito, B.; Pacheco, P.; Garcia, E.; Duchelle, A.E.; Drigo, I.; Peçanha, J.C. Lessons for jurisdictional approaches from municipal-level initiatives to halt deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, C.; Gobbi, B.; de Waroux, Y.L.; Piquer-Rodríguez, M.; Butsic, V.; Lambin, E.F. Decentralized Land Use Zoning Reduces Large-scale Deforestation in a Major Agricultural Frontier. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 136, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, J.; Amarjargal, O. Authority of second-tier governments to reduce deforestation in 30 tropical countries. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2020, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Irawan, S.; Widiastomo, T.; Tacconi, L.; Watts, J.D.; Steni, B. Exploring the design of jurisdictional REDD plus: The case of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, P.T.; Moeliono, M.; Locatelli, B.; Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Mardiah, S. Integration of Adaptation and Mitigation in Climate Change and Forest Policies in Indonesia and Vietnam. Forests 2014, 5, 2016–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Streck, C.; Peskett, L.; Brown, J.; Luttrell, C. What is the right scale for REDD? National, Subnational and Nested Approaches. In Moving Ahead with REDD: Issues, Options and Implications; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Costenbader, J. REDD+ Benefit Sharing: A Comparative Assessment of Three National Policy Approaches; Forest Carbon Partnership Facility and UN-REDD Programme: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.undp.org/publications/redd-benefit-sharing-comparative-assessment-three-national-policy-approaches (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- van Der Haar, S.; Gallagher, E.; Schoneveld, G.; Slingerland, M.; Leeuwis, C. Climate-smart cocoa in forest landscapes: Lessons from institutional innovations in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Miller, D. Zero Deforestation Zones: The Case for Linking Deforestation-Free Supply Chain Initiatives and Jurisdictional REDD. J. Sustain. For. 2015, 34, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.; Benzeev, R. The role of zero-deforestation commitments in protecting and enhancing rural livelihoods. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 32, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špirić, J.; Ramírez, M.I. Policy Integration for REDD+: Insights from Mexico. Forests 2021, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer Velasco, R.; Kothke, M.; Lippe, M.; Gunter, S. Scale and context dependency of deforestation drivers: Insights from spatial econometrics in the tropics. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seca, A.I.; Pereira, H.D.; Miziara, F. Challenges for the implementation of the jurisdictional REDD+ in the Brazilian state of Amazonas. Rev. Bras. De Cienc. Ambient. 2024, 59, e1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenteras, D.; Gonzalez-Delgado, T.M.; Gonzalez-Trujillo, J.D.; Meza-Elizalde, M.C. Local stakeholder perceptions of forest degradation: Keys to sustainable tropical forest management. Ambio 2023, 52, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepstad, D.; Ardila, J.P.; Stickler, C.; Barrionuevo, M.D.; Bezerra, T.; Vargas, R.; Rojas, G. Adaptive management of jurisdictional REDD plus programs: A methodology illustrated for Ecuador. Carbon Manag. 2021, 12, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collen, W.; Krause, T.; Mundaca, L.; Nicholas, K.A. Building local institutions for national conservation programs: Lessons for developing Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD plus) programs. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woulfe, S. Deciphering Lessons from the Ashes: Saving the Amazon. Nat. Resour. J. 2022, 62, 257–315. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, M.S.R.; Correia, J. A political ecology of jurisdictional REDD+: Investigating social-environmentalism, climate change mitigation, and environmental (in) justice in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Political Ecol. 2022, 29, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ward, D.; Larson, A.M.; Ruesta, H.G. Top-down, bottom-up and sideways: The multilayered complexities of multi-level actors shaping forest governance and REDD+ arrangements in Madre de Dios, Peru. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuits, E.; Cronkleton, P. Indigenous tenure security and local participation in climate mitigation programs: Exploring the institutional gaps of REDD plus implementation in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Policy Gov. 2020, 30, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loft, L.; Gebara, M.F.; Wong, G.Y. The Experience of Ecological Fiscal Transfers: Lessons for REDD+ Benefit Sharing; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2016; Volume 154. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, G.Y.; Luttrell, C.; Loft, L.; Yang, A.; Pham, T.T.; Naito, D.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; Brockhaus, M. Narratives in REDD plus benefit sharing: Examining evidence within and beyond the forest sector. Clim. Policy 2019, 19, 1038–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Moeliono, M.; Brockhaus, M.; Le, D.N.; Wong, G.Y.; Le, T.M. Local Preferences and Strategies for Effective, Efficient, and Equitable Distribution of PES Revenues in Vietnam: Lessons for REDD. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchelle, A.E.; de Sassi, C.; Jagger, P.; Cromberg, M.; Larson, A.M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Atmadja, S.S.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Pratama, C.D. Balancing carrots and sticks in REDD plus: Implications for social safeguards. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, C.; Loft, L.; Gebara, M.F.; Kweka, D.; Brockhaus, M.; Angelsen, A.; Sunderlin, W.D. Who should benefit from REDD+? Rationales and realities. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Angelsen, A. Using Community Forest Management to Achieve REDD+ Goals; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Trench, T.; Larson, A.M.; Libert Amico, A.; Ravikumar, A. Analyzing Multilevel Governance in Mexico: Lessons for REDD+ from a Study of Land-Use Change and Benefit Sharing in Chiapas and Yucatán; CIFOR: Bogor, Indonesia, 2018; Volume 236. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Bushley, B.; Babon, A.; Gebara, M.F.; Kengoum, F.; Pham, T.T.; Rantala, S.; Moeliono, M.; Dwisatrio, B.; et al. Coordination and cross-sectoral integration in REDD plus: Experiences from seven countries. Clim. Dev. 2016, 8, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranabhat, S.; Ghate, R.; Bhatta, L.D.; Agrawal, N.K.; Tankha, S. Policy Coherence and Interplay between Climate Change Adaptation Policies and the Forestry Sector in Nepal. Env. Manag. 2018, 61, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.K.; Quinn, C.H.; Dougill, A.J. Policy coherence and interplay between Zambia’s forest, energy, agricultural and climate change policies and multilateral environmental agreements. Int. Environ. Agreem.-Politics Law Econ. 2014, 14, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Gallemore, C.T.; Brockhaus, M.; Fatorelli, L.; Muharrom, E. How institutions and beliefs affect environmental discourse: Evidence from an eight-country survey on REDD+. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 45, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.K.; Kwak, D.; Choi, G.; Moon, J. Opportunities and challenges of converging technology and blended finance for REDD plus implementation. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 6, 1154917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, J.; Pinzon, A.; Stabile, M.C.C.; Pirker, J.; Bauch, S.; Iribarrem, A.; Sammon, P.; Llerena, C.A.; Alves, L.M.; Orihuela, C.E.; et al. Why ‘blended finance’ could help transitions to sustainable landscapes: Lessons from the Unlocking Forest Finance project. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhantumbo, I.; Hou Jones, X.; Silayo, D.; Falcão, M. REDD+ and the Private Sector: Tapping into Domestic Markets; IIED: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Awono, A.; Somorin, O.A.; Atyi, R.E.; Levang, P. Tenure and participation in local REDD plus projects: Insights from southern Cameroon. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 35, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, N.S.; Vedeld, P.O.; Khatri, D.B. Prospects and challenges of tenure and forest governance reform in the context of REDD plus initiatives in Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, P.T.; Duyen, T.N.L.; Ngoc, N.N.K.; Tien, N.D. Mainstreaming gender in REDD+ policies and projects in 17 countries. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, F. Decentralization and REDD plus in Brazil. Forests 2011, 2, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, T.A.P. Indigenous community benefits from a de-centralized approach to REDD plus in Brazil. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtzebach, Z.; Casse, T.; Meilby, H.; Nielsen, M.R.; Milhoj, A. REDD plus policy design and policy learning: The emergence of an integrated landscape approach in Vietnam. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 101, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelli, F.; Nielsen, T.D.; Dubber, W. Seeing the forest for the trees: Identifying discursive convergence and dominance in complex REDD+ governance. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).