1. Introduction

The energy consumption of European households accounts for 27% of final energy consumption and nearly 19% of gross energy consumption [

1]. According to the latest available data from [

2], as of 2021, most energy was used for heating (64.4%), hot water (11.5%), and cooking (6%). The primary source of final energy consumption is natural gas (33.5%), followed by electricity (24.6%) and then renewable energy sources (21.2%). Given the still significant contribution of fossil fuels, the building sector and buildings play a crucial role in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, representing 35% of the EU’s energy-related emissions. The continuous increase in global energy demand, historically met through the intensive use of fossil fuels, has led to significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, driving climate change and environmental degradation. As highlighted by [

3], this model of energy consumption is no longer sustainable and poses serious risks to economic development, health systems, and ecological balance. Consequently, the search for alternative, low-carbon energy solutions has become an urgent priority at both national and international levels. In this context, energy efficiency interventions in the building sector represent a crucial strategy for reducing energy consumption, mitigating emissions, and advancing toward climate neutrality targets.

The IPCC has highlighted that energy efficiency measures in buildings can be essential for significantly reducing GHG emissions at more competitive costs compared to other sectors that require intervention [

4]. In this context, the IPCC states that pathways consistent with the 1.5 °C policy require that building-related GHG emissions be reduced by 80–90% by 2050, that new buildings do not use fossil fuels and be nearly zero-energy by 2020, and that in OECD countries, the rate of energy retrofitting of existing buildings reaches at least 5% annually [

5]. Experts argue that building improvements—such as more effective insulation, decarbonized heating and cooling systems, condensing boilers, the adoption of carbon-neutral technologies, and renewable heating systems—can reduce energy demand and associated GHG emissions by up to 80% [

6].

In this framework, Europe’s proposed actions are strategic, starting with NextGenerationEU and continuing with the Fit for 55 package aimed at achieving EU climate neutrality by 2050. These initiatives promote, among other actions, investments in the energy retrofitting of residential buildings, especially in countries where the housing stock is among the oldest, such as in Southern Europe [

7,

8]. For instance, in Italy, over 65% of residential buildings are more than 45 years old and were constructed before Law No. 373 of 1976, the first legislation providing guidelines on energy savings [

9]. Buildings from that period do not incorporate thermal insulation measures and are therefore considered obsolete from an energy efficiency standpoint. This broader context emphasizes the urgent need to focus on the aging residential stock, particularly the vulnerabilities in social housing, where issues like structural obsolescence, underinvestment, and social fragility come together most severely.

Motivations

Social housing in Italy represents approximately 4% of the national housing stock (COM(2019) 150 final) [

10] and is often in comparable or poorer condition than other segments of the residential sector. This share is significantly lower than in countries such as the Netherlands, Austria, and Denmark, where social housing accounts for between 19% and 32% of the total housing stock [

11]. According to [

12], social housing is defined as affordable rental accommodation regulated by the state and allocated based on the specific needs of individuals or families. Its primary purpose is to improve the living standards of low-income groups and working-class individuals. Many of those buildings in Italy are now over 40 to 50 years old and were constructed with minimal standards, leading to significant maintenance needs without adequate investment. In some geographical areas, families face severe energy poverty, making it challenging to meet their energy needs, including maintaining adequate thermal comfort. This situation is worsened by low incomes, high energy prices, and the poor energy performance of their homes.

Energy poverty, defined as the lack of access to adequate energy services for heating, cooling, lighting, and other essential needs, is a widespread issue across all European countries. According to the latest data from 2022, approximately 40 million Europeans, or 9.3% of the EU population, were unable to heat their homes adequately. This represents a significant increase from 2021, when 6.9% of the population faced the same challenge [

13] (Energy poverty is defined by the European Union as “a household’s lack of access to essential energy services, where such services provide basic levels and decent standards of living and health, including adequate heating, hot water, cooling, lighting, and energy to power appliances, in the relevant national context, existing national social policy and other relevant national policies, caused by a combination of factors, including at least non-affordability, insufficient disposable income, high energy expenditure and poor energy efficiency of homes” (“Directive (EU) 2023/1791 on energy efficiency”, 2023)). Those most affected by energy poverty typically include lower-income groups, families with children, individuals with disabilities, the elderly, and women, particularly single mothers. In this context, social housing presents unique opportunities to tackle energy efficiency and promote social inclusion, potentially leading to economies of scale and reduced social and financial costs for residents. The Italian National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC) acknowledges energy poverty as a critical challenge within the broader context of the ecological transition. The plan sets a goal to reduce the incidence of energy poverty to between 7% and 8% of Italian households by 2030, compared to the 8.6% recorded in 2016, equivalent to approximately 2.2 million families [

14].

Implementing a forward-thinking strategy for enhancing building energy efficiency could yield numerous benefits. These include improving living conditions, decarbonizing the energy system, enhancing public health, and achieving the objectives of the EU Green Deal for ecological transition.

According to the Housing Europe Observatory [

15], half of Italy’s housing stock falls within energy classes F and G, indicating high levels of energy inefficiency. This structural weakness stands in contrast to the proactive approaches adopted by some European countries, which expanded their social housing sectors as part of their responses to economic crisis. For example, France’s significant post-2008 investment resulted in the construction of over 130,000 new social housing units in 2010. By comparison, Italy has experienced persistent underinvestment, bureaucratic delays, and limited modernization efforts in its housing sector [

11]. In an effort to address these problems, Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) has allocated EUR 13.95 billion to finance the energy and seismic retrofitting of residential buildings, including social housing. The plan aims to promote deep renovations and transform the national housing stock into nearly zero-energy buildings.

This paper adopts a qualitative policy analysis based on secondary data sources to critically assess the effectiveness of Italy’s recent policies and economic instruments in enhancing energy performance in the residential sector, including consideration of social housing. The objective is to explore the intersection between energy efficiency measures and social equity, offering insights into how future interventions can better support an inclusive ecological transition. This study argues that while Italy’s recent building renovation policies have significantly advanced environmental goals and economic growth, their limited social targeting has undermined their potential to alleviate energy poverty, highlighting the need for more inclusive and equity-centered approaches to energy transition.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses the regulatory and policy context of residential energy efficiency in Europe and Italy.

Section 3 outlines the research design, data sources, and presents an analysis and critical assessment of the Superbonus 110% and the National Recovery and Resilience Plan.

Section 4 examines the relationship between energy poverty and social housing. The final section concludes with key findings, policy implications, and recommendations to promote a more inclusive ecological transition.

2. Policy Context and Literature Review

Housing plays a central role in our lives. The quality of living spaces, their location, and the technical and structural conditions all directly influence our health and personal well-being [

16]. Additionally, the costs associated with managing and maintaining a home significantly impact household income. According to data elaborated by EU statistics on income and living conditions in collaboration with the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat), a family spends an average of EUR 320 per month on housing, compared to a net monthly income (excluding imputed items) of EUR 2734 in the previous calendar year [

17].

Effective energy performance and quality are crucial for managing both local and global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. On a macroeconomic level, financial transactions related to home purchases, the economic activity generated by the construction sector, and real estate valuations are essential for maintaining national economic stability and ensuring high levels of employment [

18,

19].

In recent years, severe economic and health crises have significantly impacted the real estate sector. The 2008 financial crisis triggered a prolonged recession both nationally and internationally, while the COVID-19 pandemic changed housing demand and people’s experiences of their homes. More recently, the Russia–Ukraine war has resulted in unexpected spikes in fossil fuel prices, which have heavily affected household budgets and accelerated efforts to improve residential energy efficiency. Additionally, rising inflation rates, market distortions caused by incentive and subsidy policies, and increasing construction costs have driven up interest rates, marking the end of an era of exceptionally low mortgage and financing costs [

20].

Within this context of accumulating and interlinked disruptions, Ref. [

21] offer a systematic investigation of polycrisis and its systemic impacts on the global housing market. Employing a thematic analysis of over 200 scholarly sources, their study identifies economic shocks, political instability, environmental disasters, technological disruptions, and social fragmentation as key drivers. Furthermore, the research delineates the differentiated effects on market regulators (e.g., governments, insurers, financial institutions) and participants (e.g., developers, contractors, tenants) across various geographies, and critically examines strategic responses including regulatory tightening, financial restructuring, environmental risk mitigation, and the promotion of resilience among stakeholders.

The European decarbonization agenda and the increasing awareness of the need to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, in line with international commitments, have underscored the vital role of the residential sector in achieving net-zero emissions by the middle of the century. Ref. [

22] show that without stringent climate policies and proactive retrofitting measures, the European residential sector risks significant delays in decarbonization, with scenarios lacking ambition leading to persistent natural gas reliance and slower CO

2 reductions; in contrast, early action combined with subsidies and cross-country collaboration yields up to 18% greater energy savings and enables near-zero emissions by 2040. The European Union’s (EU) commitment is demonstrated through various policies, regulations, and multilateral agreements that influence the transition to a low-carbon society. The primary document outlining this commitment is the European Green Deal, which serves as the EU’s sustainability strategy [

23]. The European Commission aims to make Europe the first carbon-neutral continent and a global leader in climate action. Below, key policies and directives will illustrate this ecological transition.

Among the major energy policies of the European Union, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) 2002/91/EC was a groundbreaking regulation [

24] (see

Table A1 in

Appendix A). It required Member States to reduce energy demand in the building sector and implement strategies to enhance energy efficiency. The directive introduced a methodology for calculating the energy performance of buildings, established minimum energy efficiency requirements for new constructions, and implemented energy certification systems as well as inspection procedures for technical systems. The directive primarily focused on newly constructed and existing residential buildings.

In 2010, Directive 2010/31/EU replaced the 2002 directive [

25], expanding its scope and strengthening energy efficiency measures. This directive introduced stricter performance requirements and emphasized the need to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions beyond the goals set by the 20-20-20 strategy. A significant provision was that all new buildings constructed from 2020 onward must be classified as nearly zero-energy buildings (nZEBs), which are primarily powered by renewable energy sources.

The 2018 revision, Directive 2018/844/EU [

26], aimed to create a highly efficient and decarbonized building stock across the European Union by 2050, targeting a reduction in CO

2 emissions of 80–95% compared to 1990 levels. As part of the Clean Energy for All Europeans Package (2018), the EU established a goal of reducing energy consumption by 32.5% by 2030 [

27]. In 2019, the European Commission introduced the Green Deal, which committed to a legally binding target of a 55% reduction in CO

2 emissions by 2030, with the aim of achieving 100% carbon neutrality by 2050 [

27]. To support these goals, the Fit for 55 package was approved in 2021, introducing 12 initiatives designed to reduce emissions and reshape Europe’s energy policies.

In 2020, the European Commission introduced the Renovation Wave Strategy (SWD (2020) 550 final) [

28] with the goal of doubling the annual renovation rate for both residential and non-residential buildings by 2030. The strategy focuses on promoting deep energy renovations and identifies key barriers to energy retrofitting. It sets forth shared objectives, including implementing stronger energy performance standards for public and private buildings, which will include mandatory minimum standards and increased financial incentives for renovations. Additionally, it seeks to establish targeted financing mechanisms, such as Renovate and Power Up, within the NextGenerationEU framework, which will be implemented through national recovery plans. The strategy also aims to strengthen technical and training support to improve the capacity for implementing energy efficiency projects and to expand markets for sustainable construction materials and services; and to promote the European Bauhaus initiative, launched in 2022, which is intended to foster local solutions for the ecological and digital transitions.

In 2023, the European Union adopted Directive 2023/1791, which replaces Directive 2012/27/EU and establishes the “Energy Efficiency First” principle [

13]. This directive recognizes energy efficiency as a crucial factor for societal well-being, health, and security of supply, while also promoting the integration of energy systems and achieving climate neutrality. EU Member States are required to ensure a minimum reduction of 11.7% in energy consumption by 2030, based on projections from 2020. The directive also addresses the issue of energy poverty by mandating that cost–benefit analyses take into account broader social, health, economic, and climate-related impacts. For buildings, it introduces a mandatory annual renovation rate of 3% for publicly owned properties.

Italy has integrated energy and climate policies at the national level through the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC), originally established in 2020 and revised in 2024 [

14]. Aligned with the Climate Decree and Green New Deal investments outlined in the 2020 Budget Law, the PNIEC sets out Italy’s 2030 targets for energy efficiency, renewable energy, and CO

2 emission reduction. Among its priorities, the plan includes a dedicated program to improve energy efficiency in social housing as a strategy to combat energy poverty. To meet these objectives, the PNIEC calls for the expansion and reinforcement of existing measures, emphasizing targeted interventions for vulnerable households. Key actions include improving the energy performance of residential buildings, promoting the use of high-performance technologies such as heat pumps and building automation and control systems (BACS), and increasing the integration of renewable energy sources at both the household and community level.

The Superbonus is a tax incentive that has had a significant impact on energy retrofitting projects introduced in 2020, as previously introduced. In 2022, the tax deduction rates were adjusted based on the type of intervention, with percentages ranging from 50% to 90%. The highest rate of 90% specifically applies to the Facade Bonus (Bonus Facciate), which was introduced in 2021 with a 90% deduction. However, this rate was later reduced to 60% by the 2022 Budget Law. Over time, the Superbonus has experienced multiple modifications and extensions, beginning with the 2022 Budget Law, followed by Decree Law No. 176/2022, and then the 2023 Budget Law [

29]. As of now, discussions are ongoing regarding a potential partial extension to protect projects that are already underway or the establishment of a dedicated fund to finance expenses for ongoing construction sites, particularly benefiting low- to middle-income households.

The eligible properties for the Superbonus include condominiums, single-family houses, and independent residential units within multi-family buildings, as long as they have at least one separate entrance from the outside. The use designation must be residential for single-family houses and functionally independent residential units.

In July 2021, Italy approved the PNRR, which is funded through NextGenerationEU. The plan is designed to boost economic recovery and promote sustainable development in the aftermath of the pandemic.

The following section presents the research materials and methods, with a specific focus on the available data related to the implementation and early impacts of the PNRR and the Superbonus 110% in Italy.

3. Research Materials and Methods

This study utilizes a qualitative research design focused on policy to investigate the implementation of energy efficiency measures in Italy’s residential sector, with a particular lens on social housing where applicable. The analysis is based on a descriptive and interpretive approach, drawing from secondary data sources such as legislative texts, policy frameworks, technical reports, and institutional datasets.

The research critically evaluates key tools like the Superbonus 110% and the PNRR in the context of the European Green Deal and Italy’s national recovery strategy. It examines how these measures align with European Union climate objectives and assesses their potential to simultaneously promote ecological transition and social equity.

Rather than seeking to establish causal relationships, the study aims to map key policy developments, highlight structural and strategic gaps (such as incomplete implementation in social housing, administrative and bureaucratic complexity, short-term focus versus long-term transformation, weak monitoring, etc.), and derive insights relevant to policy-making. It places particular emphasis on analyzing the disparity between policy intentions and real-world outcomes, particularly concerning the distributional effects among various social groups.

Finally, the research pays special attention to how Italy’s initiatives align with broader European objectives, specifically the European Green Deal and the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC). This analysis aims to enhance understanding of their potential to foster a fair and sustainable energy transition within the residential building sector.

3.1. Data Sources and Analytical Framework

The study is based on secondary data from various institutional, governmental, and academic sources, including Openpolis, OpenPNRR, the Ministry of the Environment and Energy Security (MASE), Enea, and the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat), as detailed in the subsequent sections. Key data inputs include official reports on energy efficiency interventions, open data, recent studies and assessments from leading European and national organizations, and peer-reviewed academic literature that analyzes energy poverty, social housing, and energy transition measures.

The analytical framework combines both descriptive and interpretative approaches. The descriptive analysis outlines the main characteristics of Italy’s building sector, the design features of policy instruments, and the scale of investments made. The interpretative analysis critically evaluates the alignment between policy intentions and outcomes, focusing on their environmental, economic, and social impacts.

By integrating these data sources and analytical tools, the research aims to provide a comprehensive and thorough understanding of how current policy instruments address the interconnected challenges of climate transition and social inclusion within Italy’s residential sector.

3.2. Case Analysis: The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)

Mission 2 of the PNRR focuses on ecological transition and allocated EUR 69.9 billion, which includes EUR 24.12 billion specifically for energy efficiency and building safety investments. Within this allocation, EUR 18.51 billion has been earmarked for refinancing the Superbonus scheme, EUR 13.95 billion directly from the PNRR under the “Energy Efficiency and Building Retrofitting” component, and an additional EUR 4.56 billion from complementary national funds [

30]. Included within the “Energy Efficiency and Building Retrofitting” component is the initiative titled “Social Housing—Innovative Plan for Housing Quality (PinQuA)—High-Impact Strategic Interventions Across the National Territory”, which has received dedicated funding of EUR 2.8 billion. The goal of the investment is to construct new public residential housing facilities aimed at alleviating housing difficulties. This initiative will mainly focus on existing public assets and the redevelopment of degraded areas, with a strong emphasis on green innovation and sustainability. The investment is structured around two areas of intervention, which will be implemented without using any new land: redevelopment and expansion of social housing, including the restructuring and regeneration of urban quality, improving accessibility and safety, mitigating housing shortages, enhancing environmental quality, and utilizing innovative models and tools for management, social inclusion, and urban well-being. At the time of writing, the effective spending of PNRR funds is around 13% of the total available funds for social housing investments [

31].

Data from [

32] confirm these financial allocations, highlighting the crucial role of energy efficiency policies in helping Italy achieve its climate objectives.

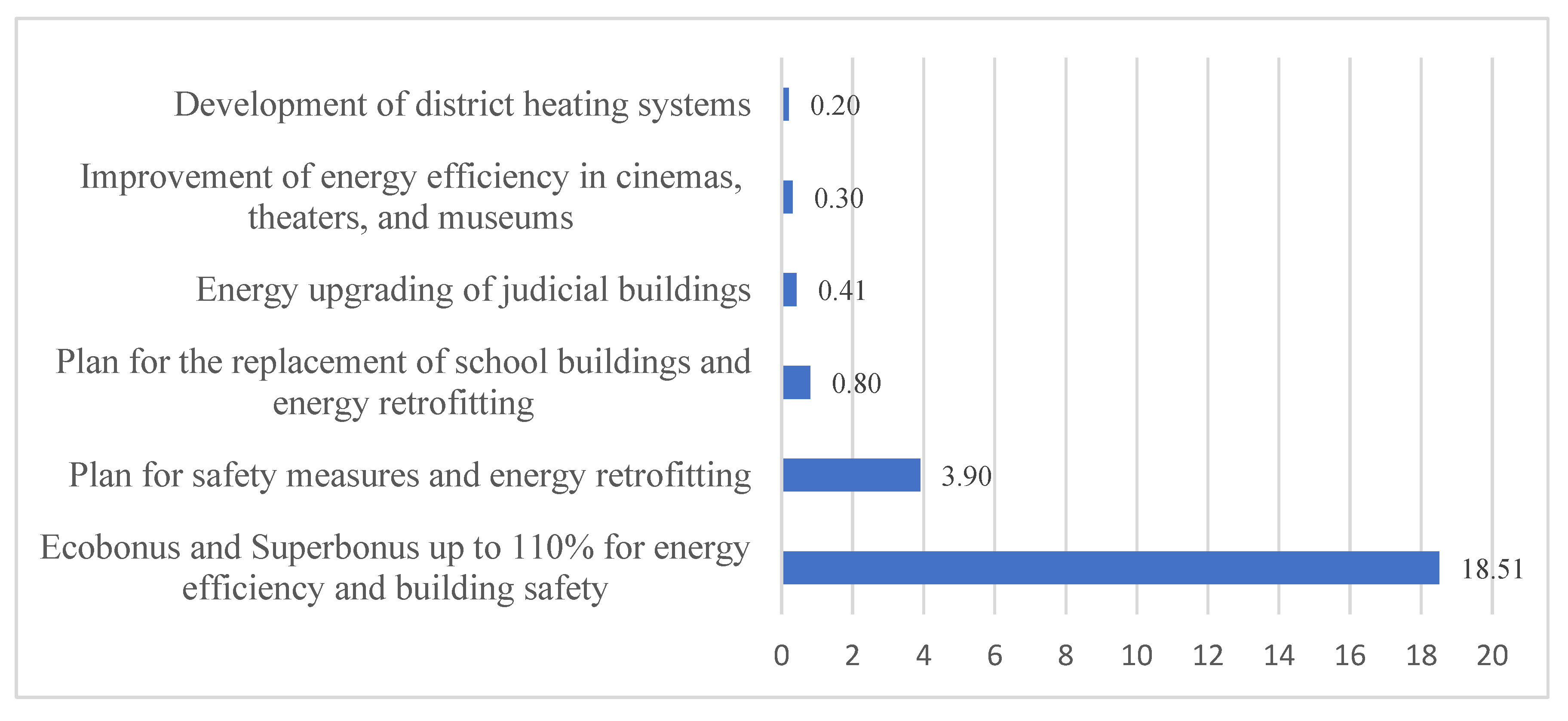

Figure 1 shows a breakdown of investments related to energy efficiency measures.

A critical analysis of the PNRR fund allocation reveals a significant concentration of resources toward private residential interventions, with EUR 18.51 billion dedicated to the Superbonus 110%, compared to marginal investments in public infrastructure sectors such as schools, judicial buildings, and district heating systems.

3.3. Case Analysis: The Superbonus Measures

In 2020, Italy introduced the Superbonus 110%, a tax deduction aimed at encouraging energy efficiency upgrades and seismic improvements. This initiative complemented existing tax credits for the Ecobonus and home renovations. The eligible properties for the Superbonus include condominiums, single-family houses, and independent residential units within multi-family buildings, as long as they have at least one separate entrance from the outside. The use designation must be residential for single-family houses and functionally independent residential units.

In Italy, there are approximately 12.42 million residential buildings, encompassing a total surface area of over 3 billion square meters. Of the roughly 35 million dwellings, more than 25 million are currently occupied. And as already written in the Introduction, over 60% of this building stock is over 45 years old [

14].

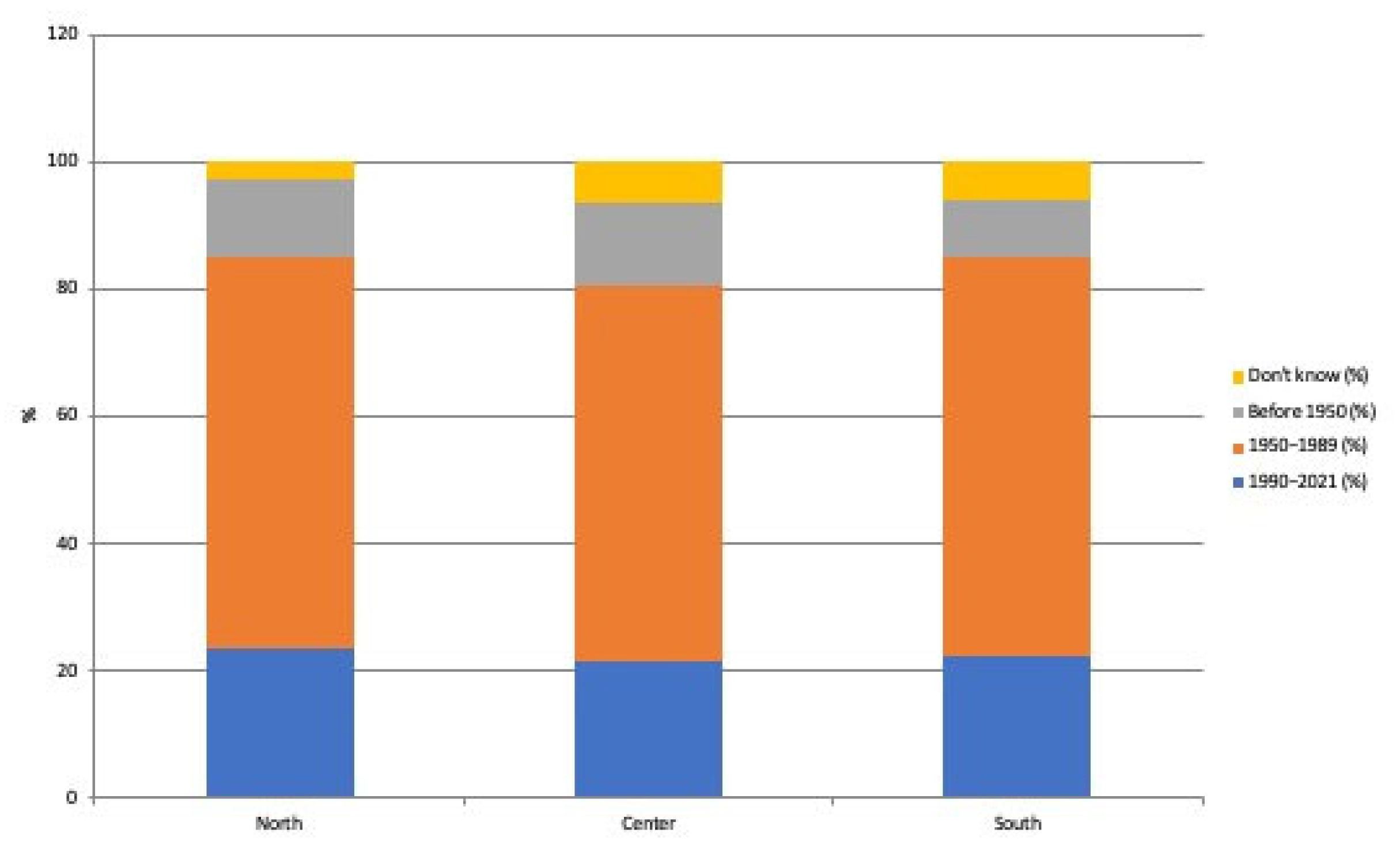

Figure 2 shows the distribution of housing stock in Italy by construction period across the three main macro-regions: North, Center, and South. It indicates that the majority of residential buildings were built between 1950 and 1989, a period marked by post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth. This timeframe accounts for over half of the housing stock in all three regions, highlighting the aging nature of Italy’s built environment and the importance of renovation policies. Additionally, the figure reinforces the idea that Italy’s housing stock is primarily old throughout all regions, with only minimal regional variation. The uniformity of post-war buildings across these macro-regions suggests that national coordination of policy tools aimed at improving energy efficiency and housing renewal is essential, particularly in addressing the specific challenges posed by mid-twentieth-century constructions.

According to a recent report by [

33], approximately 498,000 buildings (around 4 percent of the total residential stock) have taken advantage of the Superbonus, with 95.7% of the projects completed. The total expenditure amounts to EUR 113.93 billion. The overall investments for these projects are approximately EUR 120.8 billion, of which EUR 119.05 billion is eligible for tax deductions. Across Europe, energy incentives are evolving, but none have yet matched the scale of Italy’s original Superbonus 110%.

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of Superbonus-related investments by building category.

Examining

Figure 3, it is clear that the majority of interventions were performed on single-family buildings (49%) and independent housing units (27%). Condominium buildings accounted for 24% of total interventions; however, in terms of investment value, interventions in condominiums represented 67% of total investments.

3.4. Energy Poverty and Social Housing

Energy resources are vital for maintaining good health and a proper standard of living. In 2016, the European Union established the Energy Poverty Observatory to study, analyze, and monitor the challenges European citizens face in accessing energy. This initiative also aims to raise political awareness of the issue.

A recent study conducted in Italy [

34], found that approximately 14% of households reported being unable to adequately heat their homes, nearly double the European average of 7.3%. This figure reflects a combination of factors: inefficient buildings, outdated heating systems, regional disparities, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities. The issue disproportionately affects households in southern regions, renters, and single-parent families, especially those living in public or substandard housing. The situation has further deteriorated in recent years due to overlapping crises. The COVID-19 pandemic led to widespread income losses, while geopolitical tensions, especially Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, triggered dramatic spikes in gas and electricity prices [

35]. These shocks have intensified the burden on already struggling households, turning energy access into a daily struggle and placing additional stress on public welfare systems.

Energy poverty is more than an economic problem; it is a multidimensional issue with serious consequences for physical and mental health, social cohesion, and environmental justice. Inadequate heating and poor indoor air quality are linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, which in turn increase public health costs and reduce quality of life [

36]. Children living in cold, damp homes face greater risks of developmental delays and educational setbacks, creating long-term cycles of disadvantage [

37].

In this context, social housing plays a crucial role. As mentioned earlier, much of Italy’s public housing stock, built during the post-war era, is often energy-inefficient and poorly maintained. Without targeted investment, residents in these buildings remain caught in energy-poor conditions, facing higher bills for lower comfort and diminished well-being.

Retrofitting social housing presents a strategic opportunity not only to improve energy performance and reduce emissions but also to address structural inequality and foster inclusive urban regeneration. Ref. [

38] examine the effectiveness and fairness of Italy’s energy transition policies in addressing energy poverty by using the Capability Approach (CA) as both a normative and analytical framework. The authors highlight the significance of “conversion factors”, which include personal, social, and institutional conditions that affect an individual’s ability to transform available resources (such as incentives) into tangible improvements in well-being. When policies overlook these factors, they risk creating exclusion and injustice. The article critiques Italy’s current policies for being more compensation-based—offering one-size-fits-all benefits—rather than empowerment-focused. It suggests the need for more integrated, socially inclusive, and bottom-up policy designs. This approach should include data-driven monitoring, enhanced local support systems, and democratic participation in shaping energy practices.

Recent debates on social equity and sustainable urban development increasingly emphasize the critical role of urban mobility [

39]. The quality and availability of services play a crucial role in shaping individuals’ standards of living [

40]. Ensuring access to affordable and efficient public transportation is essential for reinforcing the social impacts of energy retrofitting initiatives, particularly within the social housing sector.

In general, there are three types of measures aimed at reducing energy vulnerability: those that increase household income through financial support, those that regulate or subsidize energy costs through social tariffs and bonuses, and those that improve energy efficiency, such as the Superbonus program [

41]. Energy efficiency measures tackle the fundamental causes of energy poverty and provide long-term benefits. This makes them preferable to short-term solutions, such as temporary subsidies for energy expenses or price caps on energy rates [

42,

43]. Long-term measures not only address energy vulnerability but also contribute to economic growth. They reduce a country’s reliance on external energy sources, increase property values, and help mitigate the effects of climate change by lowering energy consumption and CO

2 emissions.

Efforts to improve energy efficiency and reduce energy poverty should focus on both energy consumption and production. These efforts include retrofitting buildings for better energy use, replacing outdated appliances and technology, and enhancing energy distribution and production systems to support the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. By achieving higher energy efficiency, we can ultimately lower energy prices as a result of decreased demand and reduced need for significant investments in expanding energy infrastructure. To promote investments in energy efficiency, it is also important to address the knowledge gap and overcome technological barriers that may prevent various stakeholders from taking action. Ref. [

44] emphasize the need for strengthened capacity-building initiatives and targeted awareness campaigns. These efforts are crucial for increasing understanding, reducing technological obstacles to energy retrofitting, and building trust in energy-saving measures.

4. Discussion of the Economic, Environmental, and Social Impacts of Italy’s Policy Framework: Lessons Learned and Future Directions

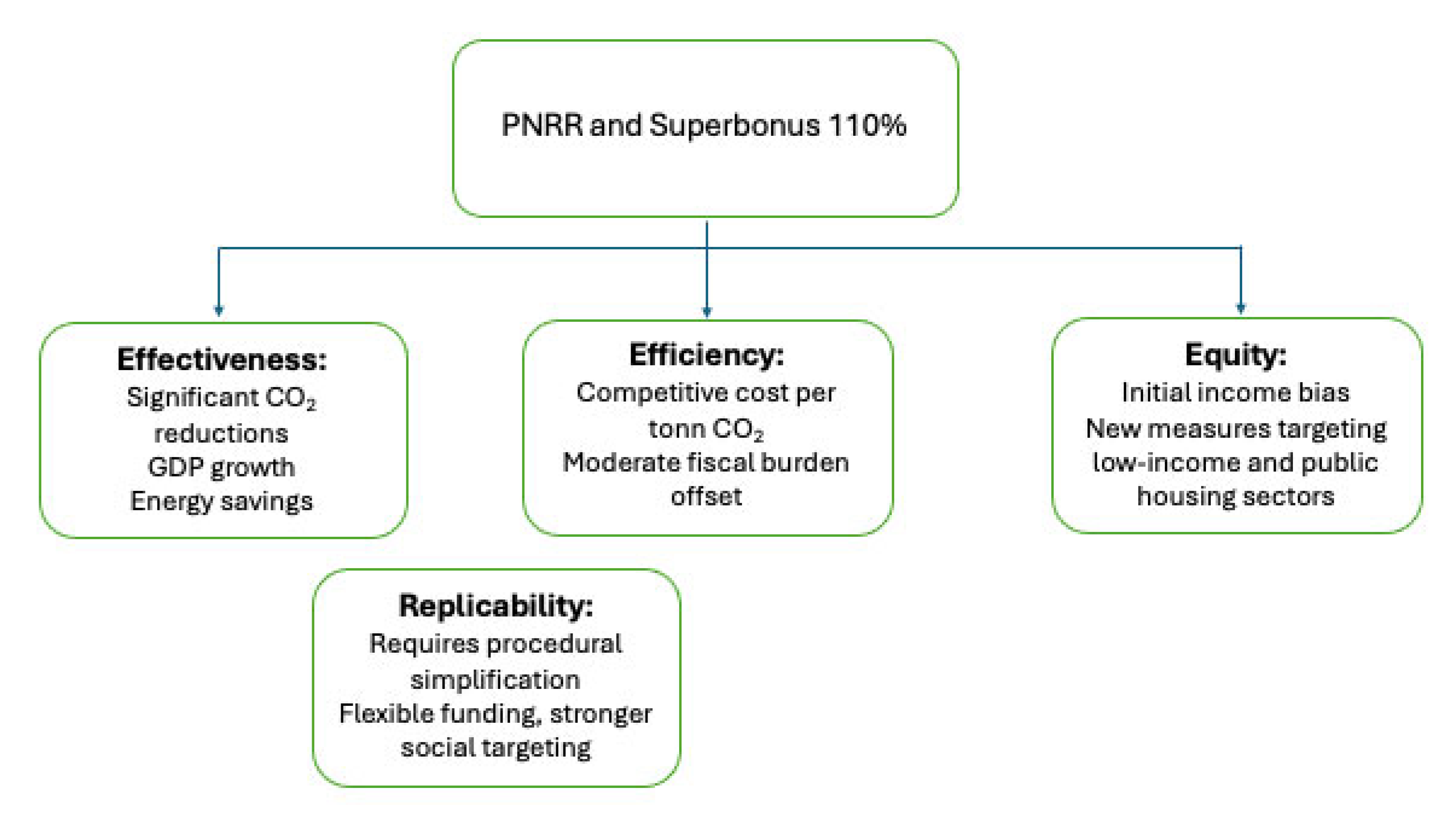

This section critically examines the main impacts of Italy’s recent policy interventions in the residential energy sector, with a particular focus on instruments such as the PNRR and the Superbonus 110%, assessed against established policy evaluation criteria, including effectiveness, efficiency, equity, and replicability.

The PNRR funding distribution, as highlighted in

Figure 1 of

Section 3.2, reveals a strategic misalignment with the broader goals of social inclusion and systemic energy transformation. Vulnerable populations, particularly those reliant on public housing and collective facilities, have received comparatively limited support, thereby constraining the measures’ potential to address structural inequalities and alleviate energy poverty. A more balanced and socially targeted investment strategy would have been better aligned with the objectives of an inclusive ecological transition, as articulated in the European Green Deal and Italy’s National Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC).

The real impact of this policy initiative will only become fully apparent over time, particularly with regard to its capacity to contribute meaningfully to the dual objectives of ecological transition and social equity. On the environmental front, its effectiveness will be measured by the extent to which it enables sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, promotes the widespread adoption of energy-efficient technologies, and accelerates the decarbonization of the residential building sector. From a social perspective, its success will hinge on the degree to which it addresses structural inequalities by improving the living conditions of disadvantaged populations, enhancing the energy performance of social housing, and reducing disparities in access to affordable and sustainable energy services.

Moreover, the long-term success of the initiative will depend not only on financial allocations and technical interventions but also on the ability to streamline administrative procedures and eliminate bureaucratic barriers that often prevent vulnerable households from accessing available support. Ensuring that these groups are effectively reached and empowered to participate in the transition will be critical for maximizing the initiative’s inclusive potential and avoiding the risk of reinforcing existing patterns of exclusion.

At the time of writing, there is limited data available to reliably quantify the full environmental impacts achieved through the Superbonus initiative in Italy, and it remains premature to comprehensively assess the long-term outcomes of the policy. Nevertheless, preliminary estimates from major organizations associated with the building sector provide useful indications of its performance. Available data suggest that the Superbonus has contributed to a reduction of approximately 1.42 million tonnes of CO

2 emissions, a notable result considering that buildings account for around 40 percent of total emissions, with peaks reaching up to 70 percent in large cities. From a cost-effectiveness perspective, the investment associated with the Superbonus corresponds to approximately EUR 59 per tonne of CO

2 avoided, a figure that compares favorably to EUR 95 per tonne in the industrial sector, although slightly less competitive than EUR 52 per tonne in the transport sector [

45]. Furthermore, according to [

46] (2023), the building incentives introduced in recent years have generated savings of nearly 2 billion cubic meters of natural gas, resulting in an additional reduction of approximately 400,000 tonnes of CO

2 emissions. These savings are equivalent to two-thirds of the domestic gas consumption reductions targeted by the emergency measures adopted in August 2022, including a shortened heating season and reduced indoor heating hours. Overall, these findings suggest that renovation incentives have been relatively effective and efficient in advancing environmental goals and strengthening national energy security. Moreover, the results indicate the potential replicability of such incentive-based programs, provided they are accompanied by streamlined administrative procedures, equitable access mechanisms, and a clear alignment with broader decarbonization strategies. It is important to note that this evaluation refers to early-stage impacts, given the limited time since implementation and the availability of only partial data. A schematic summary of the main assessment results is presented in

Figure 4.

In economic terms, the various Superbonus incentives have had a positive impact on Italy’s macroeconomic performance; however, it is essential to consider their financial and fiscal implications for the national budget. An estimate provided by [

47] provides valuable insights. According to their assessment, Superbonus incentives contributed 0.7% to GDP in 2021 and 1.5% in 2022, leading to the creation of 222,000 direct jobs in 2021 and over 600,000 jobs in 2022. Furthermore, expenditures related to the Superbonus accounted for 50% of total residential investments in 2022–2023, excluding property transfer costs, and the direct economic output generated by these investments contributed to 73% of overall residential investments. Between 2020 and March 2023, the fiscal revenue generated from Superbonus interventions totaled EUR 32.4 billion. This effectively reduced the net burden on the state—due to lost tax revenues from deductions—from EUR 97.9 billion to EUR 65.4 billion. However, evaluating the economic impact of the Superbonus on key macroeconomic indicators is highly sensitive to the specific assumptions made. For instance, a study conducted by [

48], presented to the Senate Committee on Finance and Treasury on 16 April 2024, showed that between 2021 and 2024, the Superbonus program led to a 40.2% increase in private construction investment in Central and Northern Italy, while investment in Southern Italy grew by 37.1%.

Svimez’s estimates suggest that this initiative resulted in a cumulative GDP increase of 3.8 percentage points in Central and Northern Italy and 2.9 percentage points in the South, with a national average of 3.6 percentage points. The positive impact on GDP in Southern Italy was notable, contributing to approximately one-quarter of the total growth observed from 2021 to 2024 in that region, which amounted to an overall increase of 11.7%. In contrast, in Central and Northern Italy, the Superbonus played an even more significant role, accounting for 28% of the total growth during the same period, which reached 13.4%.

The tax deductions for energy efficiency improvements in residential buildings also extend to public housing. These improvements are crucial for reducing energy consumption and addressing energy poverty. According to the most recent report by [

33], the national public housing stock comprises approximately 478,000 public residential units and an additional 161,000 publicly owned residential buildings. Notably, an estimated 60% of this building stock is significantly outdated, resulting in substantial inefficiencies in energy performance. Ref. [

49] wrote that approximately 55% of residential properties, based on Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) issued from the end of 2015 to the end of 2022, fall into the lowest energy classes (F and G), highlighting a widespread issue of poor energy efficiency in the housing sector.

According to [

50] (2014), 44% of households living in these buildings have an average annual income below EUR 10,000. This signifies a vulnerable segment of the population that faces the risk of energy poverty and lacks adequate resources for maintenance and renovation, particularly in the current environment characterized by high energy prices and rising inflation rates. Ref. [

51] observe that households currently residing in public housing across Italy tend to share relatively homogeneous characteristics. The typical tenant profile consists of single- or two-person households, where the reference person is over the age of 65, and has been living in the same public housing (ERP) unit for over a decade. This socio-demographic profile closely aligns with the one identified by [

52] as being at higher risk of absolute and/or relative poverty. According to the most recent ISTAT data, 23.1% of the Italian population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2024, an increase from 22.8% in 2023, amounting to approximately 13.5 million individuals. This classification includes those experiencing at least one of the following conditions: income poverty, severe material and social deprivation, or very low work intensity.

Originally, the Superbonus 110% program was established to assist low-income citizens by allowing them to transfer their tax credits to third parties. This initiative was intended to help them improve their homes both structurally and in terms of energy efficiency. However, in reality, the primary beneficiaries of this program were individuals with higher disposable incomes. A press release from [

45] in February 2023 revealed that 25% of Superbonus beneficiaries had a family income exceeding the national average (over EUR 3,000 per month), and 23% owned a second home. Nonetheless, there were 1.7 million individuals with low to middle incomes who could have benefited from this measure. Among these beneficiaries, 28% were employees, 15% lived in municipalities with populations between 40,000 and 100,000 inhabitants, and 25% owned apartments.

In December 2024, the Italian Revenue Agency announced that taxpayers with an income of up to EUR 15,000 (calculated based on the household equivalence scale) will be eligible to receive a financial contribution for the expenses incurred between 1 January and 31 October 2024. The measure applies to construction interventions that have achieved at least 60% progress by 31 December 2023. The measure specifically aims to support individuals and households who encountered difficulties accessing the Superbonus program or completing the necessary procedures within the restricted operational timeframe. An article published in Il Sole 24 Ore on 2 June 2023 noted that at the beginning of the year, 1344 public housing projects had been contracted but had not yet begun, totaling just under EUR two billion. These public housing projects represent a critical area for intervention to address economic, energy, and environmental challenges while ensuring a fair distribution of public resources. By focusing on these buildings, we can effectively tackle the dual challenges of environmental sustainability and social equity.

The implications of this government initiative are multifaceted. Socially, it provides much-needed relief to lower-income households, helping to bridge the gap between policy intent and actual accessibility. Many such families were previously excluded due to bureaucratic complexity, upfront financial barriers, or limited availability of technical support [

53]. By ensuring full reimbursement under these conditions, the measure promotes a more equitable distribution of public resources and strengthens the social dimension of Italy’s energy transition.

Economically, the initiative may stimulate local construction sectors, particularly in areas with a high prevalence of energy-inefficient housing. It could also contribute to job creation in retrofitting, project management, and energy services, particularly if paired with complementary training programs. Environmentally, accelerating progress on partially completed projects ensures that previously initiated energy efficiency interventions are not left unfinished, thus avoiding resource waste and securing the expected emissions reductions. From a policy perspective, the measure also highlights the importance of flexible, adaptive mechanisms that can address implementation bottlenecks and ensure that well-intentioned incentives do not exacerbate social inequalities.

By systematically applying these criteria, the section highlights the successes, limitations, and unintended consequences of the current framework, offering lessons for future policy design. Special attention is given to how these measures could be adapted or scaled to better align with the broader vision of an inclusive and sustainable ecological transition outlined in the European Green Deal.

5. Conclusions

This article examines the key policies, measures, and tools aimed at enhancing the quality and energy efficiency of residential buildings in Italy. It emphasizes the significant benefits of these initiatives on social and economic well-being, as well as important environmental outcomes, such as reducing energy consumption and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. The article pays special attention to public housing and the challenges faced by its residents, who are often economically, socially, and energetically vulnerable. Supporting interventions in public housing yields multiple benefits, including promoting social equity and justice, fostering innovation in energy retrofitting, revitalizing entire neighborhoods, improving urban environments, and creating a renewed sense of community in disadvantaged areas, often located on the outskirts of cities. Moreover, integrating building renovation programs with sustainable urban mobility strategies can help prevent spatial segregation, enhance access to employment and essential services, and contribute to the broader goals of creating inclusive and sustainable cities.

The Superbonus 110% initiative, although imperfect in its design and implementation, serves as a pioneering example of a large-scale, incentive-driven energy retrofitting policy. No other European country has sought to mobilize such a substantial amount of private investment for residential energy efficiency through mechanisms that offer full or surplus cost recovery. This proactive approach provides important lessons for future ecological transition strategies across Europe, especially in relation to the European Green Deal and national climate neutrality plans. Italy’s experience illustrates the power of accessible incentives to encourage investment. When financial barriers are minimized or removed, renovation rates can significantly increase, particularly in traditionally resistant sectors like residential buildings. However, this experience also highlights the risks of poorly targeted incentives, which can exacerbate inequalities if vulnerable populations encounter hidden administrative, informational, or liquidity barriers. Furthermore, Italy’s case underscores the importance of administrative capacity. Large-scale incentive programs require streamlined bureaucratic processes, stable regulatory frameworks, and effective monitoring systems to prevent issues such as fraud, delays, and uneven implementation across different regions. Neglecting these factors can undermine financial sustainability and erode public trust.

Finally, the Italian experience emphasizes the need to balance short-term economic stimulus with long-term social and environmental goals. Retrofit policy design should focus not only on the volume and speed of interventions but also on achieving deep renovations, alleviating energy poverty, promoting urban regeneration, and ensuring a just transition. Overall, the availability of financial incentives and subsidies remains one of the primary barriers to implementing energy efficiency measures, followed closely by regulatory, technical, and political obstacles. Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring a fair distribution of resources and effectively tackling the dual environmental and social issues related to energy efficiency in public housing.

A distinctive contribution of this study is its explicit connection between energy efficiency measures and the fight against energy poverty, promoting a more integrated and socially just model of ecological transition. Unlike conventional energy policies that prioritize emissions reductions or economic efficiency in isolation, this approach recognizes that social inclusion and environmental sustainability must be pursued simultaneously for the transition to be equitable and lasting. Despite the funding allocated through the PNRR and various bonus schemes, the results have often been disappointing. A significant portion of these funds has been directed toward more affluent individuals who have access to other financing options and can afford the upfront costs of renovations. Additionally, issues related to non-residential buildings and unmonitored projects have sometimes led to distorted activities at the state’s expense. The concurrent occurrence of major global crises, including the pandemic and the Russia–Ukraine war, has further exacerbated these challenges by driving up energy prices and distorting the market due to increased demand for construction materials and energy-efficient upgrades.

The paper highlights that policies designed without adequate attention to distributional effects risk reinforcing existing social inequalities, as more affluent households are better positioned to access incentives. In contrast, a justice-centered framework for ecological transition would prioritize interventions for vulnerable groups, such as public housing residents, low-income families, and energy-poor households, ensuring that energy savings, improved living conditions, and lower utility costs are distributed more equitably. This perspective aligns with emerging European policy frameworks, particularly the European Green Deal mechanism, which emphasizes that no region, community, or individual should be left behind on the path toward climate neutrality.