Abstract

China’s ongoing urbanization, expanding land transfer, has reshaped rural land use and generational consumption patterns. Using three waves of China Family Panel Studies data, this study applies a two-way fixed effect model to examine the impact of farmland transfer-out on generational consumption structure and explores the mediating role of household income, the moderating role of non-agricultural income share, and regional and income heterogeneity. Findings show the following: (1) Farmland transfer-out significantly increases subsistence, developmental, and hedonic consumption among middle-aged and young farmers, with the greatest rise in hedonic consumption. For elderly farmers, only subsistence consumption increases, and to a lesser extent. (2) Among middle-aged and young farmers, transfer-out raises household income, boosting all consumption types; a higher share of non-farm income further strengthens subsistence and hedonic consumption. For elderly farmers, while income increases, a higher non-farm income share weakens the income effect on subsistence consumption. (3) Regionally, land transfer-out significantly boosts subsistence and hedonic consumption in the eastern region for younger farmers, and all three types—especially subsistence—in the central and western regions. Elderly farmers in the east also see a rise in subsistence consumption. (4) An income heterogeneity analysis shows stronger effects for low-income younger farmers and high-income elderly farmers. Based on these findings, this study proposes targeted policies to promote farmland transfer-out, offering insights for optimizing land use and enhancing rural consumption, with implications for other countries’ land management.

1. Introduction

Amid ongoing socioeconomic transformation, rural areas in China are experiencing significant structural changes. Land transfer, as a core initiative of rural reform, aims to optimize the allocation of land resources and stimulate rural development [1]. The Chinese government has continued to advance land system reforms under the policy framework of “Three Rights Separation”, clarifying the division of ownership, contractual rights, and management rights [2]. This policy grants farmers greater flexibility in land disposal rights, aiming to unlock the productive potential of land through market-oriented transfers. Simultaneously, rural land transfer can significantly influence farmers’ consumption behavior, thereby contributing to poverty alleviation and the commercialization of rural markets. However, China’s consumption expenditure as a share of GDP remains relatively low compared to international standards: it stands at approximately 55%, which is below the averages of high-income countries (around 80%), middle-income countries (about 74%), and even low-income countries (around 68%). The figure is even lower in rural areas, indicating the substantial untapped consumption potential in these regions. Therefore, fostering a virtuous cycle between land transfer and consumption growth has emerged as a key pathway for promoting endogenous economic development in rural China.

Against the backdrop of ongoing improvements in land transfer systems, as of 2023, the total area of transferred rural land in China exceeded 680 million mu, with per capita disposable income for rural residents reaching 21,691 yuan per year, and per capita consumption expenditure at 18,175 yuan per year [3]. In contrast, Japan has a much higher proportion of transferred farmland relative to its total agricultural land, with a high degree of land consolidation [4]. As early as 2013, the annual per capita income of Japanese farmers had reached 490,000 yuan, far exceeding that of national civil servants [5]. Japan’s policy design places great emphasis on intergenerational succession and resource allocation between elderly and young farmers, effectively safeguarding farmers’ rights and interests [6,7]. In contrast, China’s land transfer policy implementation still faces several challenges, including significant disparities among demographic groups, regional imbalances, non-standardized transfer contracts, and the insufficient protection of farmers’ rights, highlighting the urgent need for more detailed policy design and strengthened regulatory oversight [8].

Against this background, intergenerational differences have become a critical dimension in examining the impact of land transfer on household consumption. Due to differences in resource endowments, risk preferences, and life cycle stages [9], middle-aged and young farmers and elderly farmers respond differently to land transfer. This divergence is not only a matter of social equity in rural areas but also directly affects the sustainability of rural revitalization. Ignoring generational differences in needs may cause policy benefits to be concentrated in specific groups, thereby exacerbating internal inequalities within rural society. Therefore, analyzing the intergenerational effects of land transfer is not only a scientific imperative for improving current policy design but also a practical foundation for achieving the goal of common prosperity.

Building on this foundation, the present study investigates the impact of farmland transfer-out on household consumption structure from an intergenerational perspective, utilizing three waves of panel data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). First, this study proposes core hypotheses based on life course theory and the permanent income hypothesis, and it develops an analytical framework to explain how farmland transfer-out influences household consumption patterns. Second, it applies a two-way fixed effect model to estimate the relationships, examining the mediating role of total household income and the moderating effect of non-farm income share, while also addressing heterogeneity across regions and income groups. Finally, policy recommendations are provided in light of the empirical results. The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) It deepens the understanding of how farmland transfer-out influences farmers’ consumption behavior, addressing the lack of intergenerational analysis in the existing literature and providing theoretical support for more targeted land transfer policies. (2) It investigates how household income structure affects consumption patterns, revealing that increasing the share of non-farm income and strengthening economic resilience among farmers can promote more sustainable consumption models, thereby contributing to long-term and stable rural economic growth. (3) This study aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and it may serve as a valuable reference for land transfer planning in other countries.

2. Literature Review

Since 2014, the Chinese government has implemented the “Three Rights Separation” reform, which separates ownership rights, contractual rights, and management rights of rural land. Under this framework, ownership remains with the rural collective, contractual rights belong to the household, and management rights can be transferred to actual operators [2]. The reform aims to activate the rural land transfer market and improve the efficiency of land resource allocation [10]. Since then, issues surrounding land transfer have attracted widespread attention from both academics and policymakers [11,12,13]. Farmland transfer-out refers to the process by which farmers transfer their contracted land use rights to other operators through leasing, assignment, or other means. Studies have shown that this process alters farmers’ production methods, income sources, and lifestyle priorities, thereby affecting their income levels [14], ways of life [15], and consumption behavior [16].

Unlike China, most countries around the world adopt a land privatization system in rural areas, where land can be traded through sale or lease, forming active rural land sales and rental markets [17]. However, due to high transaction costs, credit risks, and restrictions from legal and family factors, land transfers through sales remain relatively limited in many countries [18]. Many countries actively promote land leasing. For example, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have established unique short-term land lease systems [19]; Sweden practices both whole-farm leasing and partial (accompanied) leasing [20]; Scotland, through legislation, allows for multiple forms of agricultural leases and supports long-term land leasing [17]. Studies have shown that land leasing provides incentives for regional development, improves agricultural efficiency, productivity, and environmental sustainability [20], and enables both lessors and lessees to gain additional income [21]. Therefore, whether it is land transfer in China or land leasing in other countries, the core objective is to facilitate the efficient transfer of land use rights from less efficient to more efficient producers, thereby optimizing land resource utilization, increasing income for both parties, and improving living standards [16].

Chinese scholars have conducted extensive research on the impact of farmland transfer-out on farmers’ consumption behavior and its underlying mechanisms. Studies have found that farmland transfer-out can promote higher consumption levels [22], upgrade the consumption structure [23], and increase consumption diversity [15]. In terms of consumption levels, farmland transfer-out significantly raises per capita consumption, per capita durable goods consumption, and total household consumption. Key mechanisms driving this improvement include the following: changes in natural capital, adjustments in livelihood strategies [24], increased income levels, reduced income risk [25], and higher levels and costs of land transfer [26]. Regarding consumption structure, farmland transfer-out significantly contributes to the optimization of the household consumption structure [23]. Among these, the income effect caused by capital changes and shifts in livelihood patterns [27] plays a mediating role [28]. As for consumption diversity, farmland transfer-out increases property income for farmers and enhances the consumption environment through labor mobility, thereby promoting greater consumption variety [16]. In addition, studies from other countries have also demonstrated a potential link between land transfer-out and household consumption. For example, in South Africa, transferring out farmland has been shown to improve farmers’ consumption levels [29]. Researchers comparing Indonesian farmers who exited agriculture while retaining land ownership and entered the non-agricultural sector found that the latter significantly enhanced consumption and farmer well-being [30]. In Thailand, crop diversification had a negative impact on per capita consumption, while labor diversification contributed to increased consumption [31]. In Vietnam, the land certification program activated the land rental market, thereby raising consumption expenditures among rural households [32]. These findings suggest that the relationship between farmland transfer-out and farmers’ consumption is a critical issue of concern in many countries.

However, existing studies often neglect household-level heterogeneity, particularly intergenerational differences, when examining the relationship between farmland transfer-out and farmers’ consumption behavior. Due to differences in life cycle stages [33] and income structures values, the extent and mechanisms by which farmland transfer-out affects consumption behavior may vary significantly across age groups. As a result, changes in consumption structure may exhibit distinct intergenerational patterns. This study therefore investigates the impact of farmland transfer-out on the household consumption structure of middle-aged and young farmers versus elderly farmers, from the perspective of intergenerational differences. It further analyzes the mediating role of total household income and examines whether the share of non-farm income moderates the effect of household income on various types of consumption. Based on the empirical results, this study presents key conclusions and offers policy recommendations.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Fundamental Assumptions

3.1. Basic Hypotheses

According to life course theory, life is a dynamic process closely intertwined with social change, and each stage is profoundly influenced by specific socio-cultural, institutional, structural, and environmental factors [34]. The different life trajectories of middle-aged and young individuals versus elderly individuals influence their consumption perceptions. For middle-aged and young farmers, after transferring out their farmland, the released labor force enters the non-agricultural job market, leading to a short-term income increase that improves their basic living conditions. Non-farm income tends to be more stable than farming income, thereby reducing survival risks and prompting households to prioritize meeting essential needs. At the same time, non-farm income provides capital for human capital investment, and middle-aged and young farmers are more inclined to invest their land transfer income into education, skills training, or entrepreneurial activities to achieve long-term income growth [35]. Additionally, through non-agricultural employment, middle-aged and young individuals are exposed to urban consumption culture and begin integrating into urban lifestyles. The combination of income growth and mental accounting effects drives an increase in hedonic consumption. In contrast, for elderly farmers, transferring out their land weakens their sense of land-based security, and they face very limited opportunities for non-agricultural employment [36]. Their income mainly relies on pension benefits [37], unstable land rent, or support from children. To cope with uncertainty, elderly individuals tend to prioritize basic living needs. Moreover, due to their entrenched traditional consumption habits [38], shrinking social networks, and limited demand for cultural, entertainment, or educational activities, land transfer-out does not significantly impact their developmental or hedonic consumption. Based on this, this study proposes the following two hypotheses:

H1:

Farmland transfer-out increases subsistence, developmental, and hedonic consumption among middle-aged and young farmers.

H2:

Farmland transfer-out increases subsistence consumption among elderly farmers but has no significant impact on developmental or hedonic consumption.

According to Friedman’s Permanent Income Hypothesis, residents’ consumption depends on permanent income, which refers to the average income expected over the long term [39]. After farmland transfer-out, most middle-aged and young farmers begin working in non-agricultural sectors or seek employment in cities, and livelihood diversification increases non-agricultural income and total household income [40,41]. This income growth provides farmers with more disposable funds, and the non-farm wage income is perceived by middle-aged and young farmers as long-term and stable, which raises their expected income over the coming years. As a result, they tend to increase spending across all three consumption categories. In contrast, for elderly farmers, the rental income from farmland transfer-out directly increases household income, but it is unstable and does not improve their long-term income expectations. Therefore, the additional income is primarily used to meet basic living needs. Based on this, the following two hypotheses are proposed:

H3:

Farmland transfer-out can increase middle-aged and young farmers’ total household income, thereby enhancing their subsistence, developmental, and hedonic consumption.

H4:

Farmland transfer-out can increase elderly farmers’ total household income, thereby enhancing their subsistence consumption.

An increase in the proportion of non-farm income indicates that middle-aged and young farmers are more actively engaged in non-agricultural employment, which typically provides higher and more stable sources of income, thereby promoting an overall improvement in their consumption levels. For every 1% increase in the share of non-farm employment, rural household consumption upgrading increases by an average of 7% [42], suggesting that a higher proportion of non-farm income plays a positive moderating role in the consumption behavior of middle-aged and young farmers. In contrast, for elderly farmers, an increase in the proportion of non-farm income implies a decrease in the share of agricultural income within their income structure. Non-farm income often carries higher uncertainty for the elderly. Therefore, although the increase in total household income after farmland transfer-out may promote the growth of subsistence consumption, a higher proportion of non-farm income may weaken this growth effect. In other words, when the proportion of non-farm income is low, the increase in household income has a stronger impact on elderly farmers’ consumption expenditure. However, as the proportion of non-farm income rises, the instability of income makes the effect of increased household income on consumption less significant. Based on this, this study proposes the following two hypotheses:

H5:

The proportion of non-farm income positively moderates the effect of total household income on subsistence, developmental, and hedonic consumption among middle-aged and young farmers.

H6:

The proportion of non-farm income negatively moderates the effect of total household income on subsistence consumption among elderly farmers.

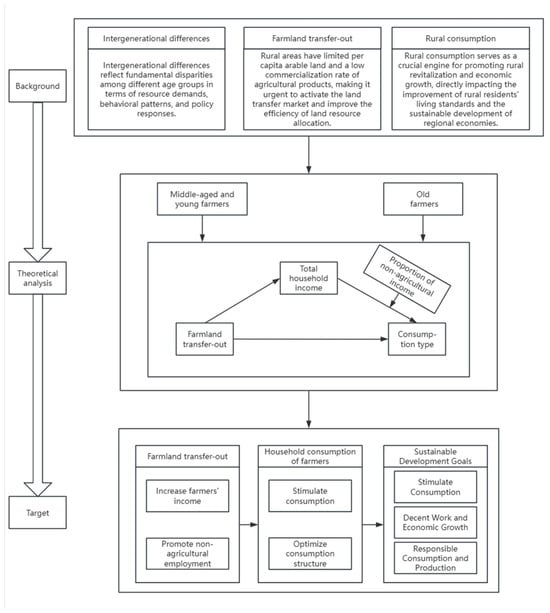

3.2. Analytical Framework

Against the backdrop of rural land system reform, investigating the impact of farmland transfer-out on the consumption structure of farmers across generations holds significant theoretical and practical value for advancing regional sustainable development. This research topic aligns closely with several United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 1: No Poverty, SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth, and SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. First, farmland transfer-out directly increases the income of elderly farmers and facilitates the transition of middle-aged and young farmers into non-agricultural sectors. These effects contribute to improving the living standards of low-income populations and advancing SDG 1 (No Poverty). Secondly, rental income from land transfer or re-employment income enhances household economic resilience, facilitates the movement of rural labor toward more productive and higher-income sectors, and supports inclusive economic growth and full employment, as emphasized in SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth). Finally, the significant differences in consumption concepts and behaviors across generations mean that farmland transfer-out induces adjustments in consumption structure, which can guide the green transformation of rural consumption patterns and the cultivation of sustainable consumption practices, thus contributing to the realization of SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). Based on life course theory and the permanent income hypothesis, this study constructs an analytical framework to explore the evolving characteristics of consumption structure across generations in the context of farmland transfer-out and its potential contribution to achieving multi-dimensional sustainable development goals (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Analytical framework diagram.

4. Model Specification and Indicator Construction

4.1. Model Construction

First, this paper applied a two-way fixed effect model to examine the impact of land transfer behavior among middle-aged and young farmers versus elderly farmers on three types of household consumption: subsistence consumption, developmental consumption, and hedonic consumption. The basic model is as follows:

Consumptioni,t = α0 + α1land-outi,t + α2Controli,t + μi + γt + εi,t

Next, a mediating variable—total household income—was introduced to test its mediating effect via stepwise regression. The model formulas are as follows:

Finci,t = α0+α1land-outi,t + α2Controli,t + μi + γt + εi,t

Consumptioni,t = α0 + α1Finci,t + α2land-outi,t + α3Controli,t + μi + γt + εi,t

Finally, the proportion of non-farm income was introduced as a moderating variable to test its moderating effect on the relationship between total household income and different types of consumption. The model is specified as follows:

where Consumptioni,t represents the dependent variables: the logarithms of subsistence consumption, developmental consumption, and hedonic consumption. Land-outi,t is the core explanatory variable: farmland transfer. Controli,t includes control variables selected for this study. Nonfarm-incomei,t denotes the proportion of non-farm income. Finci,t denotes annual household income. I and t represent individual and time, respectively. α0 is the intercept; α1 and α2 are regression coefficients; and μi, γt, εi,t represent individual fixed effects, time fixed effects, and the random error term, respectively.

Consumptioni,t = α0 + α1land-outi,t + α2non-farm incomei,t + α3Finci,t + α3non-farm incomei,t × Finci,t + α4Controli,t + μi + γt + εi,t

4.2. Data Source

The data used in this study were derived from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), administered by the Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS) at Peking University. As a nationally representative and authoritative micro-level longitudinal database, CFPS covers 25 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in China. It systematically collects comprehensive information on demographics, socioeconomic status, and intergenerational relationships through structured instruments such as the adult questionnaire and household economic questionnaire, ensuring high reliability and academic credibility.

This study integrates data from the 2018, 2020, and 2022 waves of CFPS, focusing on core variables from the adult and household economic questionnaires. To effectively identify intergenerational differences, the following criteria were established based on stratified sampling principles: (1) According to the working-age definition, household heads aged 18–60 are classified as middle-aged and young farmers, while those over 60 are classified as elderly farmers. (2) Through a multi-stage data cleaning process, household head identity was matched with questionnaire data, and observations with missing key variables were removed. After rigorous screening, a total of 3516 valid household samples were obtained—2484 middle-aged and young farmer households (70.65%) and 1032 elderly farmer households (29.35%). This sample structure not only maintains the national representativeness of the original survey but also meets the data requirements for intergenerational comparative research.

4.3. Variable Construction

Dependent Variable: Types of Consumption. Referring to the calculation methods of previous scholars [43] and based on the characteristics of the target population in this study, household consumption expenditure is classified into three types: subsistence consumption, developmental consumption, and hedonic consumption. Specifically, household spending on food, clothing, and housing is categorized as subsistence consumption; spending on transportation, communication, education and training, and cultural activities (such as purchasing books, newspapers, and magazines) is classified as developmental consumption; and spending on durable goods, healthcare, travel, and other items is treated as hedonic consumption [44]. The expenditure values for each consumption type were calculated based on the corresponding survey questions, and, then, logarithmic transformation was applied.

Core Explanatory Variable: Farmland Transfer-Out: Based on the relevant CFPS questions on farmland transfer-out: “In the past 12 months, has your household transferred out any collectively allocated farmland?” If the answer is “Yes”, it indicates that a farmland transfer-out has occurred and the variable is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned 0.

Control Variables: Drawing on previous research [23], this study mainly selects individual and household characteristic variables of the household head as control variables. For individual characteristics, the gender and age of the household head were included; for household economic characteristics, land assets, household size, and cash savings were selected. Additionally, considering China’s vast territory and the significant differences in economic levels and arable land across provinces, province is included as a control variable to account for regional disparities. The detailed descriptions of these variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions and calculation methods of variables.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Baseline Regression Model

This study utilizes Stata18 software to perform two-way fixed effects regressions based on the specified models, separately for the middle-aged and young group and the elderly group. The analysis aims to evaluate the impact of farmland transfer-out on various types of household consumption. The baseline regression results are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline regression results.

For the middle-aged and young group, farmland transfer-out has a significant positive impact on all three types of consumption: subsistence, developmental, and hedonic. Specifically, the regression coefficients of farmland transfer-out on each consumption type are 0.340 for subsistence consumption, 0.145 for developmental consumption, and 0.394 for hedonic consumption. These results indicate that farmland transfer-out significantly promotes all three types of consumption among middle-aged and young farmers. Moreover, the strongest effect was observed for hedonic consumption, followed by subsistence, and the weakest for developmental consumption, thus supporting Hypothesis H1. Regarding control variables, after farmland transfer-out, female middle-aged and young farmers tend to reduce hedonic consumption compared to their male counterparts. The household head’s age has a significantly negative effect on all three types of consumption, indicating that older individuals tend to spend less. Land assets are positively associated with developmental and hedonic consumption. Household size is positively associated with all consumption categories. Cash savings significantly increase all types of consumption, indicating that financial asset accumulation helps boost consumption. Additionally, province has a negative effect on subsistence and hedonic consumption, implying that regional differences lead to significant variations in consumption structure after farmland transfer-out among middle-aged and young farmers.

For the elderly group, the impact of farmland transfer-out on consumption is less significant compared to the middle-aged and young group. Specifically, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption is 0.194, which is significant at the 5% level, indicating a notable positive impact. For developmental consumption, the coefficient is −0.028 and not significant, suggesting that farmland transfer-out has no clear influence on spending related to education, culture, or enjoyment. For hedonic consumption, the coefficient is 0.065 and also not significant, indicating no substantial impact. These results indicate that elderly households rely more on stable sources of livelihood, and the economic returns from farmland transfer-out mainly increase their spending on necessities, thereby supporting Hypothesis H2. As for control variables in the elderly group, after farmland transfer-out, elderly female farmers tend to reduce developmental consumption compared to males. The age of the household head has no significant effect on any consumption category. Land assets are positively associated only with developmental consumption. Household size has a significant positive effect on all three types of consumption, indicating that larger households demand more in terms of consumption. Similarly, cash savings significantly increase consumption across all categories, underscoring the role of financial asset accumulation in boosting household expenditure. Lastly, farmland transfer-out significantly affects only developmental consumption among elderly farmers across different provinces.

5.2. Analysis of Mediating and Moderating Effects

5.2.1. Analysis of Mediating and Moderating Effects for Middle-Aged and Young Farmers

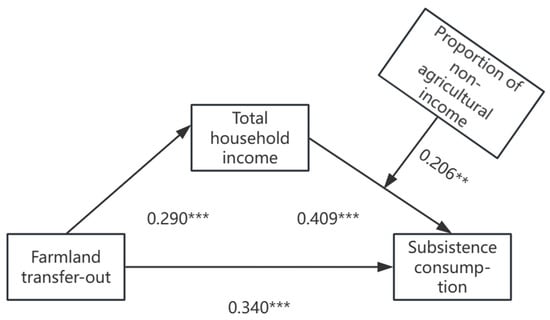

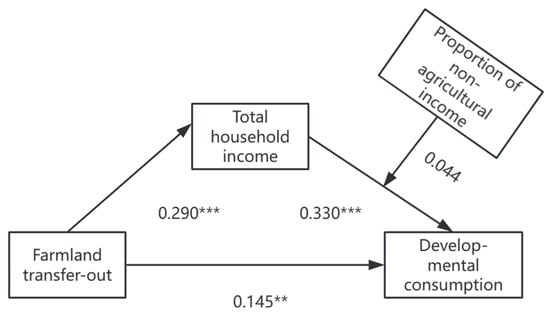

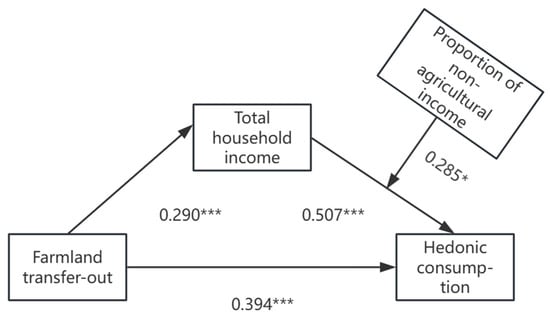

This section employs stepwise regression to examine the mechanisms through which farmland transfer-out affects the three types of consumption among the middle-aged and young group. It focuses on whether total household income functions as a mediating variable and whether the proportion of non-farm income serves as a moderating factor.

- (1)

- Mediating Effect of Total Household Income

As shown in Table 3, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on total household income is 0.290, which is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that farmland transfer-out substantially increases household income among middle-aged and young farmers.

Table 3.

Mediating effect of total household income for the middle-aged and young group.

The coefficients of total household income on the three types of consumption are as follows: 0.409 for subsistence consumption, 0.330 for developmental consumption, and 0.507 for hedonic consumption—all significant at the 1% level.

These results suggest that higher household income significantly promotes all types of consumption. Based on the magnitude of the coefficients, the effect is strongest for hedonic consumption, followed by subsistence, and weakest for developmental consumption, supporting Hypothesis H3.

The analysis of the mediating effect of total household income for the middle-aged and young group is presented in Table 3.

- (2)

- Moderating Effect of the Proportion of Non-Farm Income

A significance test was conducted on the interaction term between total household income and the proportion of non-farm income for the middle-aged and young group. The regression coefficients for the interaction term on subsistence consumption, developmental consumption, and hedonic consumption are 0.206, 0.044, and 0.285, respectively.

These results indicate that a higher proportion of non-farm income significantly enhances the positive effect of household income on subsistence consumption and hedonic consumption, while it has no significant moderating effect on developmental consumption.

In other words, the higher the proportion of non-farm income in a middle-aged and young household, the marginal impact of household income on subsistence and hedonic consumption becomes more pronounced, while the increase in developmental consumption remains relatively unchanged. These findings partly support Hypothesis H5.

The analysis of the moderating effect of the proportion of non-farm income for the middle-aged and young group is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Moderating Effect of the proportion of non-farm income for the middle-aged and young group.

The mechanisms through which farmland transfer-out affects the three types of consumption among middle-aged and young farmers are illustrated in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Mechanism of the impact of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption in the middle-aged and young group. Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of the impact of farmland transfer-out on developmental consumption in the middle-aged and young group. Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of the impact of farmland transfer-out on hedonic consumption in the middle-aged and young group. Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.2.2. Analysis of Mediating and Moderating Effects Among Elderly Farmers

This section presents an empirical analysis to explore the mechanism through which farmland transfer-out affects subsistence consumption among the elderly group, as well as the moderating effect of non-farm income.

- (1)

- Mediating Effect of Total Household Income

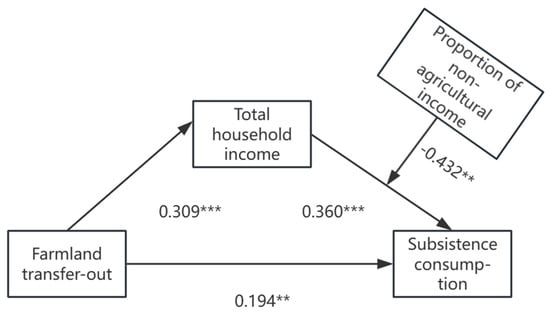

The results indicate that the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on total household income is 0.309, which is statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that farmland transfer-out can significantly increase household income. The regression coefficient of total household income on subsistence consumption is 0.360, also significant at the 1% level, suggesting that increases in household income significantly promote subsistence consumption—meaning that income growth enables farmers to increase their spending on basic living needs. These findings support Hypothesis H4.

The analysis of the mediating effect of total household income for the elderly group is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mediating effect of total household income for the elderly group.

- (2)

- Moderating Effect of the Proportion of Non-Farm Income

A significance test was conducted on the interaction term between total household income and the proportion of non-farm income for the elderly group. The resulting regression coefficient is −0.432, indicating that a higher proportion of non-farm income weakens the positive effect of household income on subsistence consumption. In other words, in households with a higher share of non-farm income, the capacity of rising income to promote spending on basic living needs becomes less pronounced.

Therefore, this moderating effect is not significant, but it confirms the validity of Hypothesis H6.

The analysis of the moderating effect of the proportion of non-farm income for the elderly group is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moderating effect of the proportion of non-farm income for the elderly group.

The mechanism through which farmland transfer-out affects subsistence consumption among elderly farmers is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Mechanism of the impact of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption in the elderly group. Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.3.1. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

- (1)

- Regional Heterogeneity Analysis for the Middle-Aged and Young Group

This section conducts region-specific regression analyses to examine whether the effects of farmland transfer-out on different types of consumption among middle-aged and young farmers vary between the eastern and central-western regions.

In the eastern region, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption is 0.269, significant at the 5% level, indicating that, after transferring out farmland, middle-aged and young farmers in the eastern region tend to increase their spending on basic living needs such as food and housing.

In the central-western region, the regression coefficient is 0.396, significant at the 1% level, and notably higher than that of the eastern region. This suggests that middle-aged and young farmers in the central-western region are more likely to allocate the additional income from farmland transfer toward meeting basic survival needs compared to their eastern counterparts.

As for developmental consumption, in the eastern region, the regression coefficient is 0.038 and not statistically significant, indicating that, in this more economically developed region, farmland transfer-out does not significantly affect spending on education, training, or cultural activities among middle-aged and young farmers.

In contrast, in the central-western region, the regression coefficient is 0.255 and statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that farmers in these areas are more inclined to use income from land transfer for developmental consumption.

Regarding hedonic consumption, in the eastern region, the regression coefficient in the eastern region is 0.565 and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating a strong tendency for middle-aged and young farmers to increase discretionary spending after farmland transfer-out.

In the central-western region, the coefficient is 0.242, significant at the 5% level, although notably lower than that in the eastern region. This indicates that, while farmers in the central-western region also increase hedonic consumption, the tendency is less pronounced. Compared to the east, middle-aged and young farmers in the central-western region are more inclined to allocate land transfer income toward subsistence or developmental needs rather than discretionary or luxury consumption.

In summary, farmland transfer-out has a stronger impact on subsistence and developmental consumption in the central-western region, whereas, in the eastern region, it more significantly promotes hedonic consumption among middle-aged and young farmers.

The results of the regional heterogeneity analysis for this group are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Regional heterogeneity analysis for the middle-aged and young group.

- (2)

- Regional Heterogeneity Analysis for the Elderly Group

This section conducts region-specific regression analyses to examine whether the effects of farmland transfer-out on different types of consumption among elderly farmers differ between the eastern and central-western regions.

In the eastern region, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption is 0.261 and statistically significant at the 5% level, indicating that elderly farmers tend to increase their spending on basic living needs after transferring out their land.

In contrast, in the central-western region, the regression coefficient is 0.060 and not statistically significant, suggesting that farmland transfer-out does not have a significant impact on subsistence consumption among elderly farmers in this region.

The results of the regional heterogeneity analysis for the elderly group are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Regional heterogeneity analysis for the elderly group.

5.3.2. Income-Based Heterogeneity Analysis

- (1)

- Income Heterogeneity Analysis for Middle-Aged and Young Farmers

For subsistence consumption, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out among the low-income group is 0.339 and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that farmland transfer-out significantly increases basic living expenditures for low-income middle-aged and young farmers. In the high-income group, the coefficient is 0.255, also significant at the 1% level, though the effect is less pronounced than in the low-income group.

For developmental consumption, the regression coefficients for the low-income and high-income groups are 0.067 and 0.050, respectively, neither of which pass the significance test. However, in the full sample of middle-aged and young farmers, farmland transfer-out significantly increases developmental consumption at the 5% level. This discrepancy may be related to how income levels are categorized.

For hedonic consumption, in the low-income group, the regression coefficient in the low-income group is 0.343 and statistically significant at the 5% level, suggesting that, after meeting basic needs, farmland transfer-out enables low-income middle-aged and young farmers to increase spending on non-essential goods. In the high-income group, the coefficient is 0.280, also significant at the 5% level, but the effect is slightly weaker than that in the low-income group.

Overall, among middle-aged and young farmers, the effect of farmland transfer-out on subsistence and hedonic consumption is more pronounced in low-income households than in high-income households.

The results of the income heterogeneity analysis for the middle-aged and young group are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Income heterogeneity analysis for the middle-aged and young group.

- (2)

- Income Heterogeneity Analysis for Elderly Farmers

Among the low-income group, the regression coefficient of farmland transfer-out on subsistence consumption is 0.005 and not statistically significant, indicating that farmland transfer-out does not significantly increase basic living expenditures for low-income elderly farmers.

In contrast, among the high-income group, the regression coefficient is 0.233 and statistically significant at the 5% level, suggesting that farmland transfer-out can significantly promote basic consumption among high-income elderly farmers.

The results of the income heterogeneity analysis for the elderly group are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Income heterogeneity analysis for the elderly group.

5.4. Discussion

This study finds that farmland transfer-out increases the disposable income of middle-aged and young farmers, thereby promoting greater expenditure on basic living needs, education and training, as well as non-essential consumption. This, in turn, contributes to the optimization of their overall consumption structure. In contrast, for elderly farmers, the rental income from farmland transfer-out improves basic livelihood security to some extent but does not lead to increased spending in other categories of consumption.

5.4.1. Discussion on Middle-Aged and Young Farmers

The impact of farmland transfer-out on the consumption structure of middle-aged and young farmers reflects that they not only receive rental income from land transfer but also have the opportunity to shift to non-agricultural industries or urban employment. This diversification of income sources leads to increased consumption expenditure [45]. Moreover, after engaging in non-agricultural work, their consumption concepts tend to change under the influence of the surrounding environment. As a result, with rising income, they are more willing to improve their quality of life and increase non-essential consumption, thereby contributing to an optimized consumption structure [46].

The results of regional heterogeneity show that, in the eastern region, where the consumption base is already high [47], the additional income from farmland transfer has a limited impact on basic living needs for middle-aged and young farmers. In addition, due to the region’s high level of economic development, education, and abundant opportunities [48], the promotion effect of land transfer on developmental consumption is not significant. However, the impact on hedonic consumption is quite strong. In contrast, middle-aged and young farmers in the central and western regions can significantly improve their basic living conditions with the extra income from land transfer and are more willing to use the income for developmental consumption to enhance their opportunities for personal advancement. However, they spend relatively less on non-essential consumption.

The results of income heterogeneity suggest that low-income middle-aged and young farmers tend to rely more on income from land, and land transfer can directly improve their economic conditions, thereby increasing their spending on basic needs. Since this group starts from a low consumption base, the income from land transfer has a more noticeable effect on hedonic consumption. In contrast, high-income groups already have a strong economic foundation, so the marginal effect of additional income from land transfer is relatively weak. The improvement in subsistence consumption is limited, and, due to their lower consumption elasticity, the impact of land transfer on hedonic consumption is less significant than that for low-income middle-aged and young farmers.

5.4.2. Discussion on Elderly Farmers

Farmland transfer-out increases rental income for elderly farmers. However, due to limited non-agricultural employment opportunities in rural areas [49] and the lack of a comprehensive pension system [50], their income mainly relies on land rent, pension benefits, and support from their children. In the face of economic uncertainty, they tend to prioritize meeting basic living needs, leading to an increase in subsistence consumption. Nevertheless, the elderly tend to have conservative consumption habits, limited social networks, declining physical function, and low demand for developmental consumption such as education or entrepreneurship. Additionally, there is no significant increase in hedonic consumption like leisure or travel [51]. As a result, although their basic livelihood security improves, their consumption structure remains unchanged, still focused primarily on essential needs.

The regional heterogeneity analysis indicates that, in the eastern region, where land transfer yields are higher, elderly farmers can use rental income to improve their basic living conditions. Moreover, with a relatively well-established social security system in the east, elderly farmers have more confidence in their future economic stability and are thus more willing to spend rather than save. In contrast, in the central and western regions, the returns from land transfer are lower and have not led to significant economic improvements. Combined with more conservative consumption attitudes among the elderly in these areas, they are more likely to save or allocate funds to their children rather than increase their own consumption. The relatively weaker medical and elderly care systems in these regions may exacerbate concerns about future financial insecurity, discouraging significant increases in consumption.

The income-based heterogeneity results reveal that low-income elderly groups tend to have a strong saving preference, opting to reserve additional income to address future uncertainties rather than using it for current consumption. In contrast, high-income elderly households possess a greater sense of financial security and are more comfortable using land rental income for daily spending. Furthermore, due to their stronger purchasing power, high-income elderly households are more willing to allocate additional income toward improving their basic consumption levels.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Based on the above analysis, this study reaches the following four main conclusions:

(1) Farmland transfer-out significantly increases consumption expenditures among middle-aged and young farmers across subsistence, developmental, and hedonic categories, with the strongest impact observed in hedonic consumption, followed by subsistence and developmental consumption. In contrast, although elderly farmers also experience an increase in subsistence consumption, the magnitude of this effect is smaller than that for the younger group, and no significant changes are observed in their developmental or hedonic consumption. (2) Among middle-aged and young farmers, farmland transfer-out promotes increased spending across all three types of consumption by raising total household income. Furthermore, a higher proportion of non-farm income strengthens this effect—particularly for subsistence and hedonic consumption. For elderly farmers, farmland transfer-out similarly enhances subsistence consumption through increased household income; however, a higher proportion of non-farm income attenuates this effect. (3) In the eastern region, farmland transfer-out significantly promotes subsistence and hedonic consumption among middle-aged and young farmers. In contrast, in the central and western regions, it exerts a significant positive effect across all three consumption categories. The impact on subsistence consumption is notably stronger in the central-western regions, while the effect on hedonic consumption is more pronounced in the east. Among elderly farmers, farmland transfer-out results in a significant increase in subsistence consumption only in the eastern region. (4) For middle-aged and young farmers, the impact of farmland transfer-out on consumption structure is more significant for low-income groups. In contrast, among elderly farmers, the influence is stronger for high-income groups.

Based on these findings, this study proposes the following policy recommendations to promote the development of rural land transfer market and guide rural populations toward a more rational and optimized consumption structure:

Middle-Aged and Young Farmers: Promoting Consumption Upgrading and Income Diversification. To encourage middle-aged and young farmers to participate in land transfer, enhanced support should be provided for their transition to non-agricultural employment. In the central and western regions, it is recommended to establish “Rural Revitalization Skills Training Centers” [52], focusing on the development of skills in e-commerce, logistics, and modern agricultural technologies. These centers should align training with local industrial demands to improve non-farm employability among this demographic group. Additionally, subsidies can be offered to farmers who participate in training programs to reduce learning costs and boost participation enthusiasm. Through these measures, middle-aged and young farmers will be better equipped to meet the demands of local industries, expand non-agricultural employment opportunities, and increase their income levels. In the eastern region, initiatives such as “Integrating Land Transfer with Cultural Tourism” can be promoted. Middle-aged and young farmers should be encouraged to use income from land transfer to develop rural tourism and homestay-based economies. To support such entrepreneurial activities, the government can provide low-interest loans and tax incentives to lower the barriers to starting a business and encourage innovative ventures among these farmers [53]. This model not only diversifies the income sources of middle-aged and young farmers but also stimulates hedonic consumption, thereby contributing to the upgrading of rural consumption structures.

Elderly Farmers: Strengthening Social Security and Risk Buffering. To encourage elderly farmers to participate in land transfer, relevant support and security systems should be improved. Elderly farmers should be allowed to sign short-term, renewable land transfer contracts, while retaining the right to reclaim their land at any time. This flexible contract design helps reduce psychological insecurity, alleviating concerns about land loss and boosting their willingness to participate. At the same time, the social security system for the elderly—especially healthcare coverage—should be further enhanced [54] to increase their sense of security and promote consumption structure upgrading.

Through the targeted design of policies tailored to different demographic groups, it is possible to both promote the orderly transfer of rural land and achieve increases in household income and consumption upgrading, thereby contributing to the deep implementation of the rural revitalization strategy.

7. Limitations and Future Work

This study conducts a micro-level empirical analysis using three waves of CFPS panel data to examine how farmland transfer-out affects household consumption structures among middle-aged and young farmers and elderly farmers from an intergenerational perspective. The findings offer valuable insights for improving farmland transfer policies. However, several limitations still remain. First, although CFPS data cover a wide range of regions nationwide, remote areas or special populations may not be fully represented, potentially limiting the generalizability of the results in less developed regions. Second, this study focuses only on the income effect as the mechanism through which farmland transfer-out influences consumption structure, without accounting for non-economic factors such as cultural or psychological influences. Lastly, this research is based on a nationwide empirical study, and it does not explore region-specific dynamics, resulting in a lack of regional targeting.

Future research can consider the following directions:

- (1)

- Incorporating more regionally diverse data, particularly from underdeveloped areas, to enhance the robustness and representativeness of the findings.

- (2)

- Expanding the analytical perspective to incorporate more non-economic factors—such as cultural and psychological influences—to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between farmland transfer-out and consumption structure.

- (3)

- Conducting in-depth interviews or fieldwork to explore region-specific impacts of farmland transfer-out on household consumption structures.

Author Contributions

Material preparation, review and editing of the writing, and data analysis were performed by J.X. and S.C. contributed to the study conception and design. Review and editing of the writing were performed by K.Z. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research Project of the National Foundation of Social Science of China: Community Governance and Post-Relocation Support in Cross District Resettlement [grant numbers 21 and ZD183]; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: Research On The Mechanism And Policy Response of Climate Migration Under Climate Change Risks [grant number: B240207112]; and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: Study on the Coordinated Development of Sustainable Liveli-hood and Ecological Protection of Relocated Farmers (grant number: B240207032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The local Ethics Committee of Hohai University approved this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fei, R.; Lin, Z.; Chunga, J. How land transfer affects agricultural land use efficiency: Evidence from China’s agricultural sector. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liang, Y.; Fuller, A. Tracing Agricultural Land Transfer in China: Some Legal and Policy Issues. Land 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Income and Consumption Expenditures of Residents in 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Hu, X.; Liu, X. The Land Problem in the Modernization of Smallholder Farming in East Asia—A Case Study of Japan. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 38, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China News Network. Annual Income of Japanese Farmers Reaches 490,000 Yuan, Far Higher Than That of Government Officials. People’s Daily Online. 2013. Available online: http://finance.people.com.cn/n/2013/0509/c153180-21417863.html (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Wang, X.; Xia, Y. The Policy Background, Experience, and Implications of Japan’s “New Farmers” Program for China. World Agric. 2021, 11, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Y. The Institutional Framework, Effects, and Implications of Farmland Consolidation in Japan. Econ. Syst. Reform 2019, 05, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, S. Innovating the Rural Land System for Chinese-Style Modernization and Promoting Common Prosperity for Farmers and Rural Areas: Theoretical Logic, Practical Experience, and Reform Consensus. Issues Agric. Econ. 2024, 08, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Hao, K.; Wu, W. An Analysis of the Factors Influencing Willingness to Withdraw from Rural Homestead Land from an Intergenerational Perspective—Empirical Evidence Based on 1177 Questionnaires in the Guanzhong Region of Shaanxi Province. J. Northwest Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 53, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X. Market-Oriented Development of Farmland Transfer under the Background of “Three Rights Separation”: Recent Developments, Driving Mechanisms, and Policy Recommendations. Issues Agric. Econ. 2025, 02, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Yang, R.; Wang, L.; Wu, B. Rural Land Transfer and the Transformation of Agricultural Production Models in China. Manag. World 2024, 40, 76–90, 106. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Halder, P.; Zhang, X.; Qu, M. Analyzing the deviation between farmers’ Land transfer intention and behavior in China’s impoverished mountainous Area:A Logistic-ISM model approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Chi, G. Does market-oriented land conveyance affect regional economic resilience? A spatial and mediation analysis based on 287 Chinese cities. Land Use Policy 2025, 150, 107457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, Y. How Does Land Transfer Affect Farmers’ Income Growth?—From the Perspective of Economies of Scale and Factor Allocation. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2021, 05, 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Gui, H. An Analysis of the Economic and Social Consequences of Large-Scale Farmland Transfer—Based on a Case Study of Lincun Village in Southern Anhui. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 10, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Cui, X.; Pan, L.; Wang, Y. Land Transfer and Rural Household Consumption Diversity:Promoting or Inhibiting? Land 2023, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; McCarry, R. The case for long-term land leasing: A review of the empirical literature. Land 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; McCarry, R. Investigating the Factors Influencing the Intention to Adopt Long-Term Land Leasing in Northern Ireland. Land 2023, 12, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Davis, J.; Hutchinson, G.; Donnellan, T.; Patton, M. Modelling regional environmental efficiency differentials of dairy farms on the island of Ireland. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 95, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastfelt, A.; Zhang, Q. Keeping agriculture alive next to the city—The functions of the land tenure regime nearby Gothenburg, Sweden. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Liang, X.; Xing, S.; Huang, L.; Xie, F. Does Land Lease Affect the Multidimensional Poverty Alleviation? The Evidence from Jiangxi, China. Land 2023, 12, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhu, K. Can Land Transfer-Out Improve Farmers’ Consumption? Consum. Econ. 2021, 37, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, H.; Xu, G.; Yu, H. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Farmland Transfer on the Consumption Structure of Rural Residents—Based on CFPS Data. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2022, 08, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Deng, D.; Shen, Y.; Fan, Q. Social Capital, Farmland Transfer, and the Expansion of Farmers’ Consumption. South. Econ. 2020, 08, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, M. Pathways to Sustainable Rural Development under the New “Dual Circulation” Development Pattern. Beijing Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ding, H. A Study on the Heterogeneous Impact of Land Transfer on Farmers’ Consumption. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 15, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mat, S.H.C.; Jalil, A.Z.A.; Harun, M. Does Non-Farm Income Improve the Poverty and Income Inequality Among Agricultural Household in Rural Kedah? Procedia Econ. Financ. 2021, 1, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Hong, M.; Zheng, L. Has Farmland Transfer Promoted the Optimization of Farmers’ Consumption Structure?—Empirical Evidence from CFPS 2018. J. Institutional Econ. Res. 2024, 1, 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Keswell, M.; Carter, M.R. Poverty and land redistribution. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeis, F.R.; Dartanto, T.; Moeis, J.P.; Ikhsan, M. A longitudinal study of agriculture households in Indonesia: The effect of land and labor mobility on welfare and poverty dynamics. World Dev. Perspect. 2020, 20, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.L.; Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U. Shocks, household consumption, and livelihood diversification: A comparative evidence from panel data in rural Thailand and Vietnam. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 3223–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, N.; Ha, L.V.; Klump, R. Property rights and consumption volatility: Evidence from a land reform in Vietnam. World Dev. 2015, 71, 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Huang, Y. A Study on Farmers’ Farmland Abandonment Behavior from an Intergenerational Perspective—Based on 293 Household Survey Questionnaires in Xingguo County, Jiangxi Province. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Sun, Y. Youth Development from a Life Course Perspective: Theories, Issues, and Reform Pathways. Youth Explor. 2024, 05, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wu, H. Non-Farm Income, Land Transfer, and Farmers’ Productive Agricultural Investment. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M. Aging in Rural China: Key Impacts, Coping Strategies, and Policy Development. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 22, 8–21. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Ning, K.; Zhong, F.; Ji, Y. The New Rural Pension Scheme and Farmland Transfer: Can Institutional Pensions Replace Land-Based Pensions?—From the Perspective of Household Demographics and Mobility Constraints. Manag. World 2018, 34, 86–97, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tao, T. Does Early-Life Poverty Experience Reduce Consumption Well-Being in Old Age? Popul. J. 2025, 47, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. A Theory of the Consumption Function; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J. Farmland Transfer, Livelihood Strategies, and Farmers’ Income—An Empirical Study Based on Six Provinces and Cities in Western China. Rural Econ. 2020, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- McCord, P.F.; Cox, M.; Schmitt-Harsh, M.; Evans, T. Crop diversification as a smallholder livelihood strategy within semi-arid agricultural systems near Mount Kenya. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, Q. The Impact of Non-Farm Employment on Rural Residents’ Consumption Upgrading—An Examination of the Mediating Effect of Social Capital. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 18, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X. The Impact of Population Aging and Income Inequality on Consumption Structure—From the Perspective of Three Types of Consumption. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 01, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Pan, Y.; Huang, Y. The Consumption Structure and Influencing Factors of Consumption Upgrading among the Elderly in China. Popul. Res. 2020, 44, 60–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R. Non-agricultural Employment and Rural Households Consumption. World Sci. Res. J. 2022, 8, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P.; Fen, J. Consumer behavior of rural migrant workers in urban China. Cities 2020, 11, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Wang, J.; Tian, M. Rural Social Security, Precautionary Savings, and the Upgrading of Rural Residents’ Consumption Structure in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X. Educational Inequalities Due to Regional Differences in China, Exemplified by Yunnan and Guangdong Provinces: An Analysis Based on Socio-economic, Cultural Context and Policy Factors. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2024, 49, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J. Work histories of older adults in China: Social heterogeneity and the pace of de-standardisation. Adv. Life Course Res. 2021, 48, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P. The Current Situation of Population Aging in China and the Development of the Social Security System. Soc. Secur. Rev. 2023, 7, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, G.; Jin, C.; Wu, W. Too old to spend? Understanding the consumption of the elderly in China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 88, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xie, G.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Y. A Case Study on How Rural E-Commerce Startups Promote Rural Resilience under the Background of Rural Revitalization. J. Jiangxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2023, 05, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, Y. Integrating Agriculture and Tourism to Promote Common Prosperity in Chinese-Style Modernization—From the Perspective of Urban-Rural Integrated Development. J. Shanxi Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 48, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Jin, Q.; Song, Z.; Song, C. The Impact of Social Security Participation on Farmers’ Land Transfer-Out Behavior—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Endogenous Switching Probit Model. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 46, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).