1. Introduction

Because of the accelerated process of urban concentration, the most developed countries are currently undergoing a process of demographic change characterized by low birth rates, high ageing, and constant migratory movements, resulting in a demographic emptying of rural areas [

1]. This phenomenon is not entirely new, although it has acquired unprecedented magnitudes due to the progressive increase in life expectancy and the reduction in fertility rates, among other factors [

2]. This poses a major challenge due to a substantial transformation of the traditional patterns of population dynamics, as they affect the demographic structure itself. These trends have led to a progressive ageing process, intensified in rural areas due to migratory movements. This circumstance generates profound changes that have repercussions in various areas, such as the economy, health, society, and politics.

Some studies suggest that, under certain circumstances, population ageing does not necessarily limit economic growth, but can boost it, due to the number of economically secure elderly people [

3]. For this, an efficient pension system must be in place [

4]. This is ultimately the silver economy [

5], which can be defined as the economic opportunities arising from public and private spending related to population ageing and the specific needs of people over 50 years of age. Thus, the silver economy comprises a large part of the general consumption economy, but with considerable differences in priorities and spending patterns [

6]. In this sense, it can contribute significantly to the sustainable development of many countries, as shown by some studies [

7]. It has also been seen as a social as well as an economic concept and has emerged as a response to the gradual ageing of society [

8].

Other researchers argue that the increase in life expectancy has positive effects on productivity, due to the expected increases in the educational levels of workers, which will serve to balance the possible decline in the labor force [

9]. Meanwhile, the reduction in fertility has a negative impact [

10,

11]. In turn, ageing, the parameter around which the research conducted revolves, can promote long-term economic growth. This effect depends on the relative relationship between changes in fertility and mortality [

12].

Gone are the days when the main problem on a global scale was to avoid reaching 20 billion inhabitants. Now, once this enormous growth and the apocalyptic scenario that it predicted have been discarded, other challenges arise. They are related to the demographic characteristics that will define the 21st century. Presumably there will be a decline in births, along with the stabilization of the size and the ageing of the world’s population. These facts go beyond the most developed countries, affecting areas such as Asia, Latin America, and even Africa [

13]. The economic consequences of demographic ageing have been profusely discussed in the literature, frequently concluding on the strong impact it will have on the expenditure of National Health Systems [

14,

15].

While it is true that the world population continues to grow, its pace has slowed because of declining fertility [

16]. With its decline, the world population is ageing at an unprecedented rate while the number of smaller households is increasing. International migration has also increased since the beginning of this century. On the other hand, the world population is also urbanizing due to increasing internal rural–urban migration [

17].

There are, therefore, numerous intertwined problems that affect several demographic parameters. Given the difficulty of studying them together and the fact that ageing is both a cause and a consequence of the serious alteration of other demographic parameters, the axis around which the present research revolves was chosen.

Taking these issues into account, this study proposes to show the territorial distribution in Andalucía and Extremadura, two autonomous communities in Spain. The study focuses on the ageing index and the dependency ratio, which are used to detect the enormous variability of both variables. However, they also allow us to intuit some kind of non-random pattern. For this reason, spatial statistical techniques are used, which seek to detect patterns using neighborhood criteria. They are also used to detect anomalous behavior.

In line with this, the central hypothesis of this study proposes the existence of territories in which both ageing and the demographic dependency ratio for the population over 64 years of age reach homogeneous values. In addition, they form territorial groupings when facing their own territorial structure, conditioned by having different economic dynamics, communication routes, etc. All this is manifested by having ageing indexes or dependency ratios that vary with respect to their surroundings (H1). At the same time, it is proposed that not all the municipalities that make up these areas have a similar behavior, with there being possible atypical cases. In these cases, some municipalities may differ from those closest to them, showing that it is necessary to deepen our knowledge of them by means of another type of analysis (H2). Finally, the advantages of using spatial analysis techniques as opposed to other types of analysis are discussed (H3).

To accept or reject these hypotheses, the specific objectives are the calculation of the ageing indexes (SO1); the calculation of the demographic dependency ratio (SO2); the detection of local patterns through the application of Hot Spot Analysis (SO3) and outliers (SO4).

2. Depopulation and Ageing

The concern about depopulation and demographic ageing is constant in the European Union. It has concerned many researchers and has involved administrations at different levels. More than a decade ago, the European Commission itself promoted the inclusion of both topics in the Cooperation Program of the VII Framework Program (2007–2013) [

18]. It also promoted research through other scientific initiatives such as the creation of the European Research Area in the Ageing 2 network [

19] or with FUTURAGE research program design projects [

20], among other outstanding initiatives that have been maintained over time [

21].

Efforts to deal with depopulation and ageing have multiplied since the first decade of this century. In general terms, the demographic decline of inland areas is a phenomenon that has reached significant dimensions in many European countries and around the world. Europe has not been immune to these processes of demographic regression. In fact, studies show that depopulation has mainly affected Eastern and Southern Europe. Specifically, eight countries (Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine) experienced annual population declines between 2011 and 2020. Three other countries (Albania, Lithuania, and Portugal) had only one or two years without population loss. The most affected were Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, and Romania, with steady population declines due to natural causes and migration. Moreover, similar patterns of depopulation and age structures were observed in NUTS 3 units within these countries and in neighboring regions [

22]. Italy is also no stranger to this regressive trend, as this phenomenon affects about 60% of the Italian territory, especially southern Italy, which has been living for too many years in conditions of persistent emergency [

23]. Something similar is happening in Spain.

The selective migration of young and highly qualified people from remote rural areas causes significant demographic, economic, and social problems in the region of origin, to the benefit of the receiving regions. It also generates other collateral effects such as the degradation of the region of origin as an environment conducive to innovation and entrepreneurship. These migratory flows can have lasting repercussions, affecting age structures and, therefore, birth and death rates [

24].

It is the result of two independent processes: on the one hand, a gradual effect derived from the increase in life expectancy, and on the other, a cohort effect that develops more rapidly and less permanently. In addition, the spatial movements of the population increase the effect due to fluctuations in the size of age groups.

Spain’s rural areas have experienced unprecedented depopulation, albeit with varying degrees of intensity. Although its incidence is notably more pronounced in the northern half of Spain compared to the southern half, there are specific areas in the south that have suffered a particularly severe demographic decline [

25].

Ageing is a phenomenon of profound social significance. It has important repercussions, which gives rise to a wide variety of analyses, such as those focused on obtaining indicators and studying the structure of the population [

26].

Both depopulation and ageing have relevant economic consequences, especially for pension systems [

27] and health and care systems

However, the territorial dimension has been less addressed by the literature, even if it refers to one of its main causes, ageing. While most studies focus on the economic consequences of ageing and low fertility, territorial variability, especially at the level of administrative units below NUTS 3, has been largely neglected. This lack of attention to regional differences is relevant, given that solutions to demographic challenges must be adapted to the specific realities of each territory [

28]. Therefore, the response to this phenomenon will depend on the conditions of each place. This is why it is interesting to identify specific areas with similar characteristics. That fact justifies the inclusion of neighborhood criteria in the analysis of the phenomenon.

The literature emphasizes the changes and opportunities offered by the current demographic reality [

29]. There is a major concern about the impact of demographic changes on socioeconomic development. This is due to the mismatch between rapid population growth and the socioeconomic security of individuals. It follows that population growth acquires the status of a social problem [

30]. Europe has considered its demographic future by analyzing the main determinants of population, as well as its dimensions and challenges [

31,

32,

33]. Despite this, economic concerns occupy a prominent place [

34], although some importance is also attached to the impact of migration [

35,

36,

37].

In the Spanish context, the demographic challenge is particularly significant. Spain is among the countries with the lowest birth rates in the world, with an index of 6.61‰ in 2023, and with a downward trend according to official statistics [

38]. This decline is mainly explained by the reduction in the average number of children per woman, which currently stands at 1.12. Consequently, the overall fertility rate in the country has fallen to 30.24‰, although with significant differences between the Spanish and foreign populations. In 2023, the fertility rate of Spanish women stood at 28.08‰, while that of foreign women reached 39.75‰ [

39].

At the same time, the ageing of the population has intensified, especially because Spain is among the countries with the highest life expectancy. The ageing index, which in 2024 reached 142.35%, has experienced a remarkable growth compared to the value of 106.4% recorded in 2001 [

40]. This phenomenon, together with low birth rates, configures a demographic challenge for the country, since an increasingly ageing population with fewer young people poses far-reaching economic and social problems.

However, the analysis at the national level does not adequately reflect regional disparities in terms of demographic problems. Rural areas face these phenomena with greater intensity than urban areas, which has led to a growing depopulation of these territories. This process began in the decade of the 1950s and continues to be a persistent problem today. It has given rise to what is known as “empty Spain”, due to the enormous depopulation that part of the country has suffered over the last few decades. Therefore, it is necessary to reorient public policies to reverse or mitigate this population loss [

41]. In contrast, large cities, avid for labor and well provided with services and infrastructure, have managed to partially mitigate this problem by attracting migrant populations. In addition, tourism is playing a key role in reconfiguring the demographic dynamics of some regions [

42,

43].

One of the most striking aspects of demographic change is the increase in life expectancy. In 2004, life expectancy at birth was 77.0 years for men and 83.6 years for women. In contrast, in 2022, these figures rose to 80.4 years for men and 85.7 years for women [

44]. By 2035, life expectancy is expected to reach 83.2 years for men and 87.7 years for women [

45]. This increase in longevity has considerable economic and social implications, especially in terms of the demand for health services, pensions, and long-term care, placing additional pressure on social welfare systems.

The impact of demographic change is significant, not only for the population structure but also for the economy and social welfare. In fact, it presents a serious challenge for society and, by extension, for its social and healthcare system [

46,

47]. Among the main consequences are a decrease in the working-age population, an increase in the demand for social and health services, a reduced capacity for economic growth, and the unsustainability of pension systems. These factors pose a risk to the stability of the welfare state, which has generated growing concern among policymakers and demographic experts.

The growing concern about demographic issues, especially in rural Europe, has been accompanied, and in some cases preceded, by the publication of national population strategies [

48]. In this context, the VI Conference of Autonomous Presidents of Spain, held in 2017, stressed the need to address the demographic challenge as an issue of high relevance for the country. As a result of this conference, the National Strategy against the Demographic Challenge was drawn up, which focuses on three priority areas. These are territorial depopulation, population ageing, and the effects of the floating population. According to this strategy, 63% of Spanish municipalities have experienced a loss of population so far in the 21st century, with a figure that reaches 90% in municipalities with less than 1000 inhabitants [

49,

50].

The demographic challenge has gained significant media coverage and has become consolidated in the public consciousness as a very serious problem. According to various studies, 85.6% of the Spanish population considers the demographic challenge to be very serious (37%) or quite serious (48.6%). In relation to depopulation, 88.5% of society perceives it as a serious problem. As for ageing, 77.8% of the population considers this phenomenon to be a very serious problem [

51].

It is a complex phenomenon in Spain, which poses significant challenges for the population structure and the sustainability of the economic and social system. Given the enormous complexity and territorial disparity in terms of demographic patterns, it is essential to carry out a specific study that can address the demographic problem in a disaggregated manner. In this case, we propose adopting the main indicators of ageing used by the literature or, at least, the most significant ones [

52].

Although ageing is one of the key problems posed by the demographic challenge at any scale, it should not be forgotten that other problems derive from it that have a clear social component. These are ageism and intergenerational relations, factors that affect social welfare and favor social cohesion. The first is conceived as prejudice or discrimination against people because of their age [

53,

54], as referred to by numerous authors [

55] who go so far as to integrate the study of ageing [

56]. The second implies that interactions occur between individuals of different age groups, which are essential for social cohesion, as they promote mutual understanding, respect, and support between generations [

57,

58].

The usual treatment of the collected data is by various statistical analyses [

59]. However, a convergence of spatial demography, agent-based modeling, and geodemography is observed in the literature, adding nuances to population dynamics. Advances such as spatial clustering, gravity models, geostatistical analysis, and cellular automata models enrich the understanding of migration patterns and population distribution [

60]. In fact, the use of tools such as Hot Spot, Cluster, and Outlier Analyses is increasingly reflected in the literature presenting demographic studies of various kinds. In some cases, they seek patterns or causes that explain rural depopulation [

61,

62], and in others, the creation of spatial models [

63].

4. Results

Both the process of population ageing and the demographic dependency ratio of people over 64 years of age can be represented in the territory. However, the individualized view of each of the municipalities that make up the study area (1173) does not allow us to draw clear conclusions or patterns of behavior in large areas. In fact, when the basic statistical parameters are analyzed, the average of the ageing index is 2.915, with a minimum value of 0.356 and a maximum of 79.

Its grouping in intervals shows that only 2 municipalities have a low ageing index (≤0.5) while 114 have a moderate one (0.501 to 1.000). The rest of the municipalities reach an index higher than 1, so it is considered high, exceeding the value of 5 in 133 cases. These values reflect the fact that the population is ageing, since in 1057 of the 1173 municipalities in the study area (90.11%), there is at least one person over 64 years of age for every person under 15 (

Table 5).

On the other hand, high ageing affects even the cities themselves, although there is a certain tendency for the more populated municipalities to have lower indices. This is corroborated by the Pearson coefficient, which is −0.102, showing the negative nature of the relationship; it is not very significant, but is representative considering the size of the sample. Something similar happens when the correlation between ageing and population variation between 2011 and 2022 is analyzed by means of this same coefficient, which is −0.072. However, if the demographic variation between 1981 and 2022 is considered, it is −0.123.

The territorial analysis shows that few municipalities reach a low or moderate ageing index (shades of green) (

Figure 4). They coincide with the coast and with the surroundings of the main cities. In addition, there are some specific areas dedicated to intensive agriculture and requiring significant labor, such as Talayuela and its surroundings (province of Cáceres), where significant sized foreign populations are brought together. The same happens in El Ejido and its surroundings (province of Almería), although with a much more pronounced character.

The analysis of the demographic dependency ratio for the population over 64 years of age evidences a notable variability in terms of its records. However, when considering the population between 15 and 64 years of age as a normalization factor, 956 municipalities present low ratios (≤0.5), compared to 182 that have a moderate ratio (0.501–0.750) and 35 with a high value (>0.750) (

Table 6).

These data highlight the future increase in these ratios, where the category of moderate RDD will gradually acquire the profile of high. This means that there is one person over 64 years of age for every person between 15 and 64 years of age. These are small municipalities, located in the province of Cáceres. Specifically, they are La Garganta (363 inh.), Carrascalejo (233 inh.), Casares de la Hurdes (374 inh.), Pescueza (125 inh.), and Campillo de Deleitosa (81 inh.). In addition to these, there are another 30 municipalities, also located in the province of Cáceres and some in the province of Almería. All this is a clear indication of the problem of ageing in very specific places in the study area.

The territorial distribution offers a very clear perspective of the areas with the highest demographic dependency ratios, especially when analyzing the sections that will have problems soon. These are the areas where the ratio exceeds 0.501, which will enter the category classified as moderate. These areas cover a large part of the province of Cáceres, the west of the province of Badajoz, and the north of the province of Córdoba, in addition to an important strip concentrated in the east of the provinces of Jaén, Granada, and Almería (

Figure 5).

The analysis of the ageing index and the demographic dependency ratio suggests the existence of areas with common behaviors. However, given the distribution in municipalities and the variability of the indices, common patterns are not always observed that allow us to detect clusters or, conversely, outliers. For this reason, we opted for the application of spatial statistical techniques, by means of which it is possible to go beyond individualized data.

The results obtained for each of the municipalities are included as

Supplementary Material. This contains information on the population volume, the ageing index, the demographic dependency ratio of people over 64 years of age, and the categories identified with Optimized Hot Spot Analysis and Optimized Outlier Analysis for each variable.

4.1. Optimized Hot Spot Analysis

4.1.1. Ageing Index

The technique applied on the ageing index considers the 1173 municipalities, on which it evaluates the minimum value (0.3561), the maximum (79.0000), the average (2.9149), and the standard deviation (3.7509). These values show a clear variability, despite which the aim is to define hot and cold spots. These involve the grouping of nearby municipalities with similar ageing rates. Furthermore, in the search for optimization, 10 outlier municipalities are excluded because of their locations. They are therefore discarded for the calculation of the ideal bandwidth. This results in a total of 396 municipalities are statistically significant. Moreover, with this distance, only 0.9% of the entities had fewer than eight neighboring nuclei (

Table 7).

The search for general patterns that can be used to detect hot or cold spots on the ageing index allows us to extract, in a generic way, several areas of interest.

The territorial distribution (

Figure 6) shows that the hot spots include a large part of the province of Cáceres, another considerable area in the province of Almería, and a small group in the province of Badajoz. In total, 252 municipalities are hot spots, characterized by high ageing rates, as are their neighbors. In fact, 200 municipalities are classified as hot spots with a 99% confidence level, another 30 municipalities are classified as hot spots with a 95% confidence level, and in the remaining 22, the confidence level drops to 90%.

In these hot spots, the ageing index is variable, with a minimum of 0.68 in Pechina (Almería) and a maximum of 79, calculated for Gargüera (Cáceres). These are usually sparsely populated municipalities, except for the cities of Cáceres (95,456 inhabitants), Plasencia (39,247 inhabitants), and Coria (12,308 inhabitants), although the confidence level of the most populated city is 90%.

On the other hand, cold spots are equally interesting, since they refer to groupings of municipalities that have lower ageing rates in common with their neighbors than the rest. In fact, there are two large nuclei that make up cold spots. On the one hand, there is the city of Seville and its nearest metropolitan area. On the other hand, there is the city of Granada, also surrounded by its nearest metropolitan belt. In both cases, the confidence level is 99%, although around these cores, it drops to 95%. In addition to Seville (681,998 inhabitants) and Granada (228,682 inhabitants), these clusters also include Dos Hermanas (137,561 inhabitants), Alcalá de Guadaira (75,917 inhabitants), and other municipalities such as Mairena de Aljarafe, La Rinconada, Los Palacios y Villafranca, Coria del Río, etc., already below the threshold of 50,000 inhabitants. Although these are the main cities, it should be mentioned that these cold spots are also composed of smaller towns such as Agrón, Dúdar, Castilleja del Campo, and Ventas de Huelma, with fewer than 1000 inhabitants.

In addition, there are other cold clusters, with a confidence level of 90%, in the city of Huelva and its surroundings, such as Aljaraque, Bollullos Par del Condado, Aljaraque, and San Juan del Puerto. Another one also appears in the surroundings of Cordoba, in this case, integrated by the municipalities of Puente Genil, Moriles, Santaella, and Aguilar de la Frontera. Finally, there is one more in the province of Malaga, specifically, municipalities such as Cártama, Alhaurín de la Torre, and Fuente de Piedra.

4.1.2. Demographic Dependency Ratio

When Optimized Hot Spot Analysis is applied on the DDR variable, it considers the 1173 municipalities to calculate the minimum value (0.0993), the maximum (1.4062), the average (0.3846), and the standard deviation (0.1566). These values show a clear variability in the set of municipalities. Despite this, the technique used attempts to define hot and cold spots. Likewise, it excludes 10 outlier municipalities, which are discarded to calculate the ideal bandwidth. This is set, as in the previous case, at 32.686 m, making a total of 701 municipalities statistically significant (

Table 8). Furthermore, with this distance, only 0.9% of the entities had fewer than eight neighboring nuclei.

The search for general patterns that can be used to detect hot or cold spots on the demographic dependency ratio allows us to locate, in a generic way, several areas of interest (

Figure 7).

The territorial distribution of the hot spots highlights most of the province of Cáceres, the region of La Serena, in the province of Badajoz, and the north of the province of Córdoba, as well as a considerable part of the province of Almería. These areas comprise a total of 319 municipalities, characterized by a high demographic dependency ratio, as well as their neighboring centers. In fact, 274 municipalities are classified as hot spots with a 99% confidence level, another 28 municipalities are classified as hot spots with a 95% confidence level, and in the remaining 17, the confidence level drops to 90%.

In these municipalities, the demographic dependency ratio reaches high values, although they oscillate. The maximum values are reached in small municipalities in the province of Cáceres, such as Campillo de Deleitosa, Pescueza, Casares de Hurdes, Carrascalejo, and La Garganta. In all of them, proportion 1 is exceeded, that is, there is one person over 64 years of age for every person between 15 and 64 years of age. These are small villages, with a population of fewer than 1000 inhabitants. Also included in this large block of hot spots are cities such as Cáceres, Plasencia, Baza, and Huércal-Overa, whose populations range from 95,456 for the former to 20,093 for the latter. It should also be considered that Cáceres has a confidence level of 90%. In some cities, ageing is also beginning to be important because they are not attractive to immigrants, normally young people, which could compensate in some way for the ageing of the resident population.

The cold spots also have an interesting distribution, since they are characterized by lower demographic dependency ratios and their preferred area of distribution corresponds to the main cities and their area of economic influence. In this sense, clusters in the provinces of Huelva, Seville, Cadiz, Granada, and even Cordoba and Jaen stand out. Nevertheless, the level of confidence to consider them as cold spots is variable.

These areas defined as cold spots occupy 382 municipalities in total, although the group with 99% confidence is made up of 223, the group with 95% confidence is made up of 109, and 50 have 90% confidence. From this, we can deduce the importance and significance of the cold spots with the highest level of confidence, where the demographic dependency ratio is 0.26. This important area is home to 3,782,734 people, forming the most dynamic zone from a demographic and economic point of view. It includes the cities of Seville, Malaga, Cordoba, Almeria, Marbella, Algeciras, Cadiz, and Jaen, all of which have more than 100,000 inhabitants.

4.2. Optimized Outlier Analysis

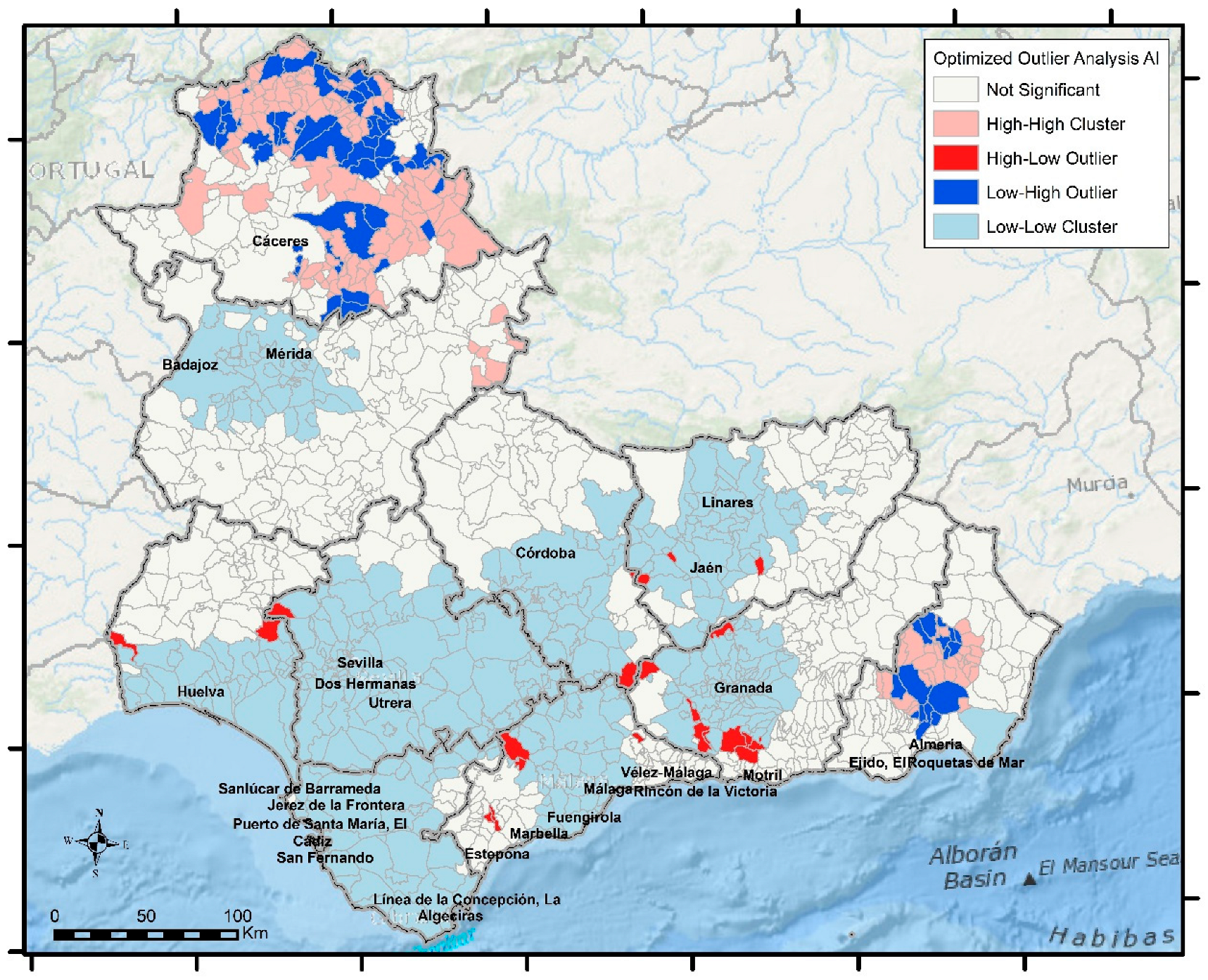

4.2.1. Ageing Index

The analysis of the ageing index performed with the Optimized Outlier technique qualifies the results obtained by the Hot Spot technique. In this case, it is essential to recognize that no significant pattern is found in 530 municipalities. On the other hand, it is relevant when we turn to the clusters where ageing is high or low for the surrounding set of municipalities, that is, for groups HH and LL, either because of their high or, conversely, low ageing index. In addition, it is essential to consider the outliers, which are municipalities that stand out for having a behavior in the analyzed variable that is different from that of their surroundings. These are the HL and LW groupings, depending on whether they have a high index compared to their neighbors or a low index compared to their surroundings.

Considering the above, there are 88 anomalous municipalities, of which 22 are considered positive outliers (HL) and 66 negatives (LH), as shown in

Table 9.

The territorial distribution of the outliers introduces interesting novelties on the behavior of the ageing index (

Figure 8). In this sense, 66 municipalities stand out in which the index obtained is lower than that of their surroundings (LH). They occupy specific areas within the provinces of Cáceres and Almería, characterized by their more favorable economic dynamics. Among them are Plasencia, Coria, Miajadas, Trujillo, and Moraleja in the province of Cáceres, and Macael, Tabernas, Gádor, and Fines in the province of Almería. Of all of them, Plasencia is the largest city (39,247 inhabitants), followed by Coria (12,308). The rest of the municipalities have a significantly lower population; in fact, many do not even reach 1000 inhabitants. The average value reached by the ageing index in this group of outliers is 2, while its neighbors exceed the value of 7.5.

Another 22 municipalities are in the opposite situation, precisely those that are characterized by having a higher ageing index than their neighbors (HL). They are located mainly in the provinces of Granada and Malaga and, less significantly, in the provinces of Jaen, Cordoba, Huelva, and Seville. They are small municipalities, with a population of fewer than 5000 inhabitants. In fact, most of these municipalities have fewer than 1000 inhabitants, although there are some with a larger population, such as Iznájar (4002 inhabitants) and Alganirejo (2436). In this group of municipalities, the average ageing index is 4.14, well above the LL group (1.4), in which it would be integrated as an anomaly.

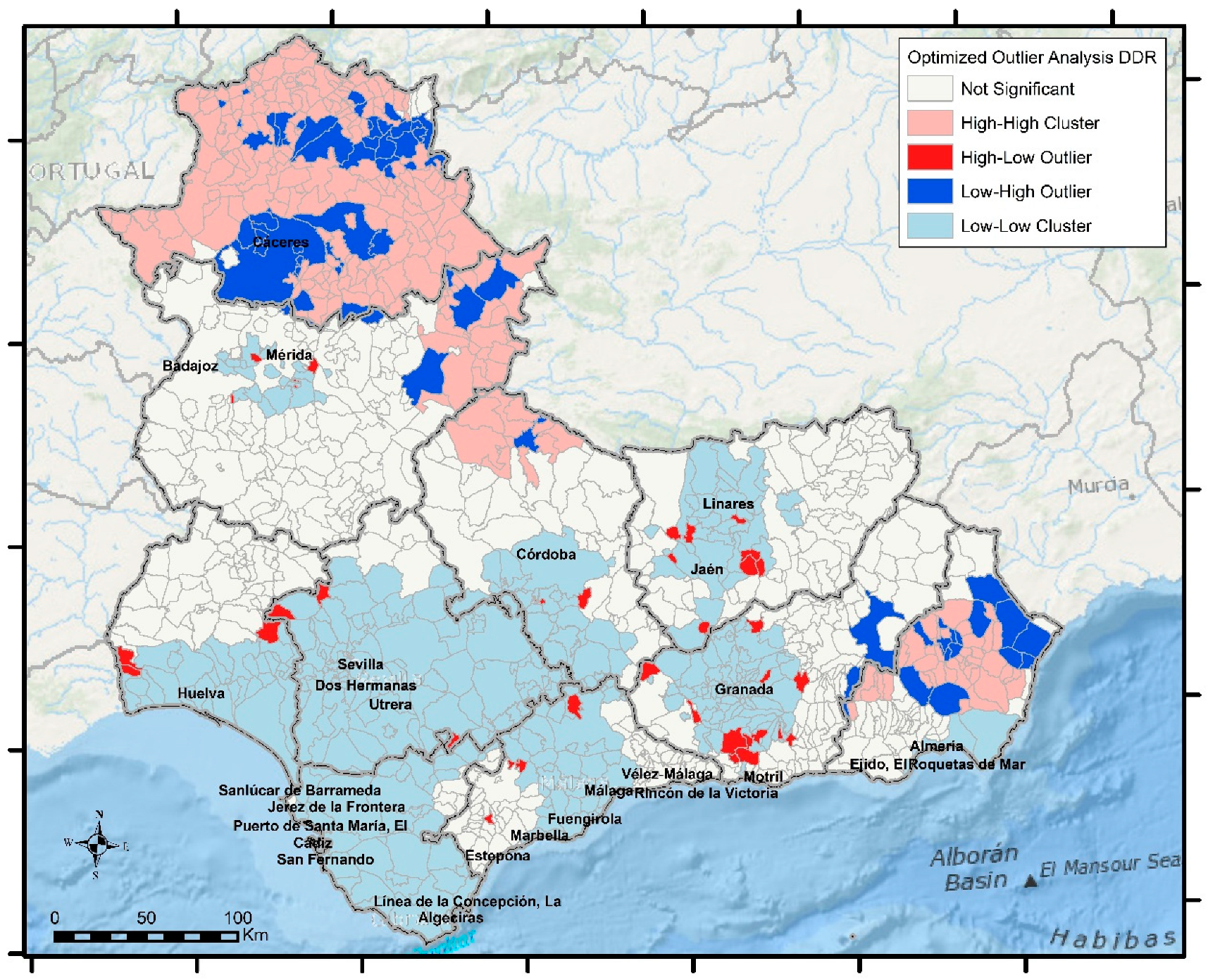

4.2.2. Demographic Dependency Ratio

The results obtained for the demographic dependency ratio using the Optimized Outlier technique qualify the results achieved using the Hot Spot Analysis. In this case, there are 466 municipalities where no significant pattern is found, but it is relevant when resorting to clusters where ageing is high or low for the surrounding municipalities—that is, for clusters HH and LL, or in the case of outliers (HL and LH).

Considering the above, there are 99 anomalous municipalities, of which 36 are considered positive outliers (HL) and 63 negative outliers (LH) (

Table 10 and

Figure 9).

The values grouped with similarities in RDD among neighbors characterize a good portion of the municipalities. In fact, there are 248 with high values and surrounded by neighbors with equally significant values (HH), although they only contain 212,465 inhabitants, from which we can deduce their small size. Meanwhile, 360 are characterized precisely by the opposite (LL), although altogether they have 6,754,123 inhabitants. Nevertheless, what is really striking about this technique is the analysis of outliers.

The atypical municipalities characterized by a demographic dependency ratio lower than that of the surrounding municipalities (LH) number 63. The average ageing ratio is 0.31, compared to 0.58 in the surrounding areas. Its territorial distribution affects the provinces of Cáceres and Almería, in line with the HH groupings, although some municipalities are also detected in the provinces of Badajoz, Córdoba, and Granada. They are mostly small towns located in areas with a positive economic dynamic, although there are also some larger cities such as Cáceres, Plasencia, Baza, and Huércal-Overa.

The HL group stands out for having higher demographic dependency ratios than those of the surrounding area. They affect parts of the provinces of Granada, Jaen, Malaga, Seville, Cordoba, and Huelva, as well as the province of Badajoz. There is only one large city in this group, Cadiz (113,066 inhabitants), since the rest are small towns, many of them with fewer than 1000 inhabitants. In them, the demographic dependency ratio reaches an average value of 0.46, but with maxima that exceed the value of 0.6 in the municipalities of El Madroño, Lugros, and Faraján. However, the minimum ratios are reached in Cádiz, El Ronquillo, and Molina, with values below 0.4.

5. Discussion

Demographic changes have a major impact [

81]. As a result, they have become a serious problem for many regions. The challenges posed by population ageing are considerable, as are the resulting health, economic, and social consequences [

82]. To try to reduce its impact, the State, the family, and the market need to take action to meet the needs of the older population [

83,

84]. For this reason, many countries are trying to introduce some changes in addressing what they call “the demographic challenge”.

Depopulation is closely related to changes in vegetative growth in developed countries and to the continuing decline in the birth rate. It is also modified by the lack of “compensation” derived from migratory flows, both international and national.

In this context, demographic ageing is a recurrent theme in Europe and there is increasing talk of depopulation [

85]. However, these processes are not explained by specific crises but are the result of two centuries of a structural situation associated with modern economic growth, which has certainly been aggravated by certain episodes [

86].

The consequences of demographic decline are a territorial problem, not exclusively demographic. Although it mainly affects rural areas, there are differences due to the very functionality of rural areas, their economic development, accessibility, etc. [

87].

Depopulation affects all scales, from the global to the national or lower order, such as regions or municipalities. Rural decline is an inevitable process as society evolves from an agrarian to an urban industrial economy and, finally, to a knowledge economy [

88].

In European countries, numerous territories have experienced and continue to experience depopulation, caused by a deficit of births relative to deaths, negative net migration, or both. This demographic decline is a multicausal process, in which natural deficits and negative net migration rates operate as factors of depopulation in most cases [

89]. Simultaneously, many of these territories face the process of population ageing, resulting from a decrease in the birth rate and a prolonged increase in longevity. The processes of depopulation and population ageing are closely interrelated [

90].

In the Spanish context, social and territorial cohesion policies have been intensified to combat depopulation in rural areas. In addition to rural development policies, various social and fiscal policies have been implemented. Specific measures have been applied in the autonomous communities’ personal income tax brackets, such as deductions for birth, adoption, and childcare expenses. This section focuses on the instruments designed to address the demographic challenge and the fight against rural depopulation, as well as on the governance system established for their management [

91].

Despite this, demographic behavior is very unequal in the country, although it is true that a certain rural gap can be detected because of depopulation [

92].

In some autonomous communities bordering the study area, such as Castilla-La Mancha and Castilla y León, significant depopulation phenomena can be observed. To mitigate these phenomena, actions have been proposed that prioritize the areas most affected by this process, with Castilla-La Mancha being one of the pioneer regions in this decision-making process. Among the programmed measures, the Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) stands out, which, implemented through the European Structural and Investment Funds, proposes priority areas for action in Castilla-La Mancha [

93].

Despite all efforts, some studies show that rural areas with greater demographic challenges continue to show regressive behavior. In contrast, municipalities with more than 2000 inhabitants have improved the imbalance of the settlement system in provinces such as Alava (Spain). In addition, an increase in ageing and a gender mismatch in adult ages due to the shortage of women have been observed [

94].

On the other hand, ageing has become so important that countries are working to understand the profile of the elderly, since it affects basic services such as health and social care, economic issues, pension systems, etc.

Studies on demographic, health, economic, social, and other indicators, as reflected in Spain, have proliferated. These studies investigate demographic problems in an attempt to answer numerous questions, including how many elderly people live in Spain; will the ageing process continue in the future; how many years can they expect to live and how many in good health; what diseases do they suffer from; what are the main causes of death; do they have sufficient economic resources; or even how many are below the poverty line [

95]. In addition, new concepts are emerging because of ageing and longer life expectancy, such as the fourth age, considered from the age of 80 years [

96,

97], or the silver economy [

98,

99], whose role as a response to the demographic challenge is being questioned in some countries [

100,

101].

Ageing, together with the intense depopulation of the country’s interior [

50], represents a real challenge for demography, as can be seen from the national strategy to meet the demographic challenge [

49]. A real State policy is needed to tackle the problem across the territories [

101], to which the European Union also contributes through the Next-Generation funds [

102].

Governance has become a solid framework for designing and implementing public policies, creating a new institutional culture. Coordination between actors and institutions, integration of policies and sectors, network participation and cooperation, and the ability to adapt to change are essential. Territorial governance, especially through the LEADER program, is a good example of how this approach is applied in rural areas. However, each rural territory advances at its own pace and faces challenges in achieving effective territorial governance [

103].

The solutions are complex in a society like today’s, in which the urban population is more important than the rural population, because the urban center offers better employment options, as well as numerous services, both basic and others related to leisure and recreation. This causes cities and their immediate surroundings to follow a more favorable demographic dynamic, with higher birth rates and lower ageing rates. Likewise, there is a need for access to services, which are normally concentrated in urban centers, so a polycentric system that can redistribute them and make them accessible to the rural population is proposed [

104].

This circumstance affects the role played by the territory in demographic contexts, since the interior of the country does not always follow the same trend. There are similarities, certainly, but also notable territorial differences [

105,

106]. Moreover, recent studies show that a combined analysis of demographic and economic trends reveals how some of them are retracing the declining course of the past. Others appear to remain mired in a dynamic of stagnation or decline [

107].

The autonomous communities of Andalusia and Extremadura follow similar patterns to those described for the country, where ageing is beginning to be problematic in some areas. This fact is clearly observed when analyzing two indicators frequently used in the literature, the ageing index and the demographic dependency ratio. In fact, although the Andalusian population continues to grow in overall figures, a large part of the Andalusian territory is characterized by the loss of inhabitants. In this sense, from a spatial point of view, there are notable differences between the growth areas (coastline, urban agglomerations) and the rest of the territory (interior, mountainous areas), characterized by a process of provoked demographic depletion [

108].

However, the treatment of the data and their cartographic representation, although they show unequal demographic behavior in the territory, do not allow us to extract homogeneous zones in which the two parameters analyzed present common characteristics. For that reason, this study resorts to a geostatistical analysis. It stresses the importance of territorial character and, above all, neighborhood relations, which allow us to extract areas with homogeneous or atypical behavior to be used as a reference in more in-depth studies. These techniques have been used with some profusion in a multitude of studies with clear territorial implications. They make it easier to move from a global analysis to a local or even individual analysis, thus affecting measures of spatial segregation [

109,

110].

Demographic research involves the study of demographic processes and outcomes that take place in the territory. For this reason, the territorial component must be directly included in the calculations of many demographic variables, improving the understanding of the distribution of the population and its demographic characteristics. In fact, in 2007, the concept of spatial demography emerged, because of the significant progress of Geographic Information Systems and the inclusion of spatial statistical tools among their advanced functionalities [

111,

112].

In line with these trends, this research has been considered as going beyond the mere cartographic representation of two parameters linked to the ageing of the population. For this purpose, mapping cluster tools, included in ArcGIS software, such as Hot Spot Analysis and Outlier Analysis, are used. Both allow the measurement of these clusters, which facilitates the identification of homogeneous behaviors with the former and particularities with the latter. From this, we can deduce the holistic conception of the research. While the Hot Spot technique identifies generic territorial patterns related to the variables analyzed, Outlier Analysis seeks to identify anomalous behavior. The combination of both techniques improves the understanding of the ageing index and the demographic dependency ratio for all the municipalities in the study area. Naturally, these results should serve as a basis for more in-depth studies analyzing the causes and consequences of these behaviors. Their main usefulness revolves around the detection of nearby areas with similar characteristics, alluding to the very nature of neighborliness.

The results offered by both techniques support the central hypothesis of this study, which defended the existence of relatively homogeneous areas where the parameters linked to ageing reach relatively homogeneous values. This makes it possible to concentrate efforts in specific areas, as was proposed in the community of Castilla-La Mancha (H1). They also certify that some cases are detected in which the behavior of certain municipalities is contrary to that of the area in which they are located. These anomalous cases should inspire specific studies in the field to investigate their causes (H2). This spatial conceptualization of ageing corroborates that the application of geospatial analysis techniques allows for the discovery of behavioral patterns and, at the same time, makes it possible to detect anomalous behavior with respect to the variables analyzed. It follows that their use makes it possible to go beyond quantitative analyses by incorporating the distance criterion in the algorithms used (H3).

The importance of these territorial analyses is reinforced because the spatial distribution of ageing has been of concern to numerous authors for decades [

113]. Now, technical advances allow us to delve much more deeply into the territorial distribution of this process. Nevertheless, it is common to find studies on Andalusia [

114] and Extremadura [

115] that corroborate the gradual ageing process and the demographic crisis in rural areas [

116].

Both hypotheses are in line with the results obtained by other authors who analyze the situation in Spain, where they conclude that ageing shows continuities, discontinuities, and contrasts, which are the result of the unequal incidence that both the evolution of natural mobility and, above all, migratory dynamics have had on past demographic structures [

117,

118].

Ageing, as the main result of many of these structural changes, is compromising the demographic present of many Spanish municipalities, determining the viability of a large part of the Spanish territory, which is irremediably doomed to depopulation and demographic collapse. The reverse side of this situation is played out in the environments of many cities, the islands, or the coastal strips of the country, which have seen their demographic structures revitalized thanks to the continuous reception of young populations [

117].

Although the existence of a strong ageing process in rural areas has been demonstrated, the phenomenon also affects most of the territory analyzed. Despite this, the differences are key, since the cities and their immediate surroundings can attract new residents through migratory processes and the demographic emptying of young people from areas where rurality is evident.

The applicability of the results should serve as a basis for competent administrations in demographic matters to articulate measures specifically oriented to the hot spots that have been detected in the ageing index and in the ratio of demographic dependence. At the same time, the location of outliers should be subject to a specific analysis, especially if they have lower values in both variables than those characteristic of the area in which they are inserted.

Despite the fulfillment of the objectives and the corroboration of the initial hypotheses, there are certain limitations. These include the following. On the one hand, the unit of analysis chosen, the municipality, encompasses differences since the entire population is assigned to it. This is not always the case, since there are cases where in the same municipality, there are different population centers, in addition to a population distributed among isolated buildings, which make up the dispersed population. Together with this limitation introduced by the deficiency of the source used, despite its official nature, it is possible to highlight another, such as the exclusive treatment of two demographic parameters linked to ageing, leaving aside others such as birth rate, mortality, natural growth, or migrations themselves, in addition to the gradual depopulation. This leads us to plan continued research with approaches—like the use of multivariate techniques such as Grouping Analysis—to accommodate these parameters. On the other hand, it must be recognized that the use of spatial statistical techniques, despite their long history in the scientific literature, is not without its problems. However, their use is fully justified according to the first law of Geography, when it states that although everything is related to everything, things close to each other are more related than things far away [

119]. On that topic, it is important to note that spatial dependence is determined by a notion of relative location, in which the effect of distance is emphasized. When the notion of space is extended beyond the strict sense of Euclidean space, including political, economic, and social space, spatial dependence becomes a recurrent phenomenon in the applied study of social sciences. In line with this, the two techniques used resort to the criterion of Euclidean and non-real distance, in addition to having a unidimensional character and considering a single variable.

The precise limitations of this study are centered on two aspects. The first is related to the territorial units of analysis. Our research deals with municipalities, and when it comes to using population centers, it will be necessary to resort to other types of information. However, it lacks the sufficient level of detail to calculate the ageing index and the demographic dependency ratio. In that sense, a more detailed analysis involving the capitals of the municipalities, the smaller local entities, and even the population residing in scattered areas should be undertaken. The second limitation is the use of spatial statistical tools, which involve the conceptualization of the distance relationship assuming a two-dimensional Euclidean space. This implies that the neighborhood criterion takes as a reference the shortest distance between municipalities, instead of the real distance or, more precisely, the travel time.

Considering these limitations, we intend to continue this study from two different perspectives. The first is focused on the use of the main parameters that make up the demographic challenge, resorting to the integration of mapping clusters with spatial restrictions, in such a way that the neighborhood criterion is also integrated into the variables analyzed. The second is oriented to the elaboration of spatial segregation indexes, with infra-municipal units of analysis, such as census sections.

6. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study on the demographic challenge in Extremadura and Andalusia warn about the complexity and variability of population dynamics in these regions. By applying advanced spatial analysis techniques, a more detailed understanding of ageing and demographic dependence has been obtained.

This study concludes with the seriousness of the ageing and depopulation problems affecting these regions. Through an innovative methodological approach, which combines advanced spatial analysis tools and key demographic parameters, it has been possible to identify patterns and trends that require urgent attention.

In addition to this general conclusion, other more specific conclusions are obtained, among which the following stand out.

At the technical level, the effectiveness of using spatial statistical techniques to analyze behavior is demonstrated, which include the neighborhood criterion as a key element for discovering hidden patterns. These are not always visible if we opt for the cartographic representation of the variables used. In that sense, this study corroborates that these tools are decisive in identifying critical areas where demographic problems are more accentuated. Thus, Optimized Hot Spot Analysis detects “hot spots” that show high value in the ageing index and, therefore, require urgent action. It also discovers “cold spots” characterized by the opposite. In contrast, Optimized Outlier Analysis identifies outliers, which can provide crucial information about municipalities that, despite being in areas with a problematic demographic environment, exhibit a population behavior that contrasts with the general behavior, suggesting the need for an analysis adapted to their peculiarities.

On the other hand, the results indicate that a significant number of municipalities, especially those with smaller populations, have a high rate of ageing. This circumstance threatens the demographic viability of some municipalities and, in addition, has repercussions for the sustainability of their economic and social systems. It is imperative, therefore, that public policies focus on these critical areas, implementing strategies that stimulate population revitalization and improve the quality of life of residents. They are freely accessible and form part of the

Supplementary Material accompanying this research.

It is essential that the relevant administrations use these findings to formulate specific measures targeting the “hot spots” identified in the analysis. This includes creating attractive incentives for young people and improving infrastructure in rural areas, as well as investing in essential services that promote a dignified and fulfilling life for all inhabitants, regardless of their age.

In addition, this study underscores that the demographic issue is multifaceted and intertwined with the rest of the demographic factors. Therefore, it is suggested that future research integrates a more holistic approach, considering the interrelationship between these elements. Such an approach will allow us to not only to better understand the demographic present but also develop solutions that fit the needs of each locality.

In conclusion, this analysis not only provides a clear diagnosis of the current situation in Extremadura and Andalusia but also offers a set of valuable tools and a clear direction for future actions. The implementation of integrated and adaptive policies is presented as the key to effectively addressing demographic challenges. With a coordinated approach that prioritizes the needs of the population, a more balanced and sustainable future can be envisioned for these regions, where both the young and the old can continue to contribute to the social and economic fabric of their communities.