Integrating Farmers into Contract Farming in Peripheral Rural Areas in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Debate Around Contract Farming

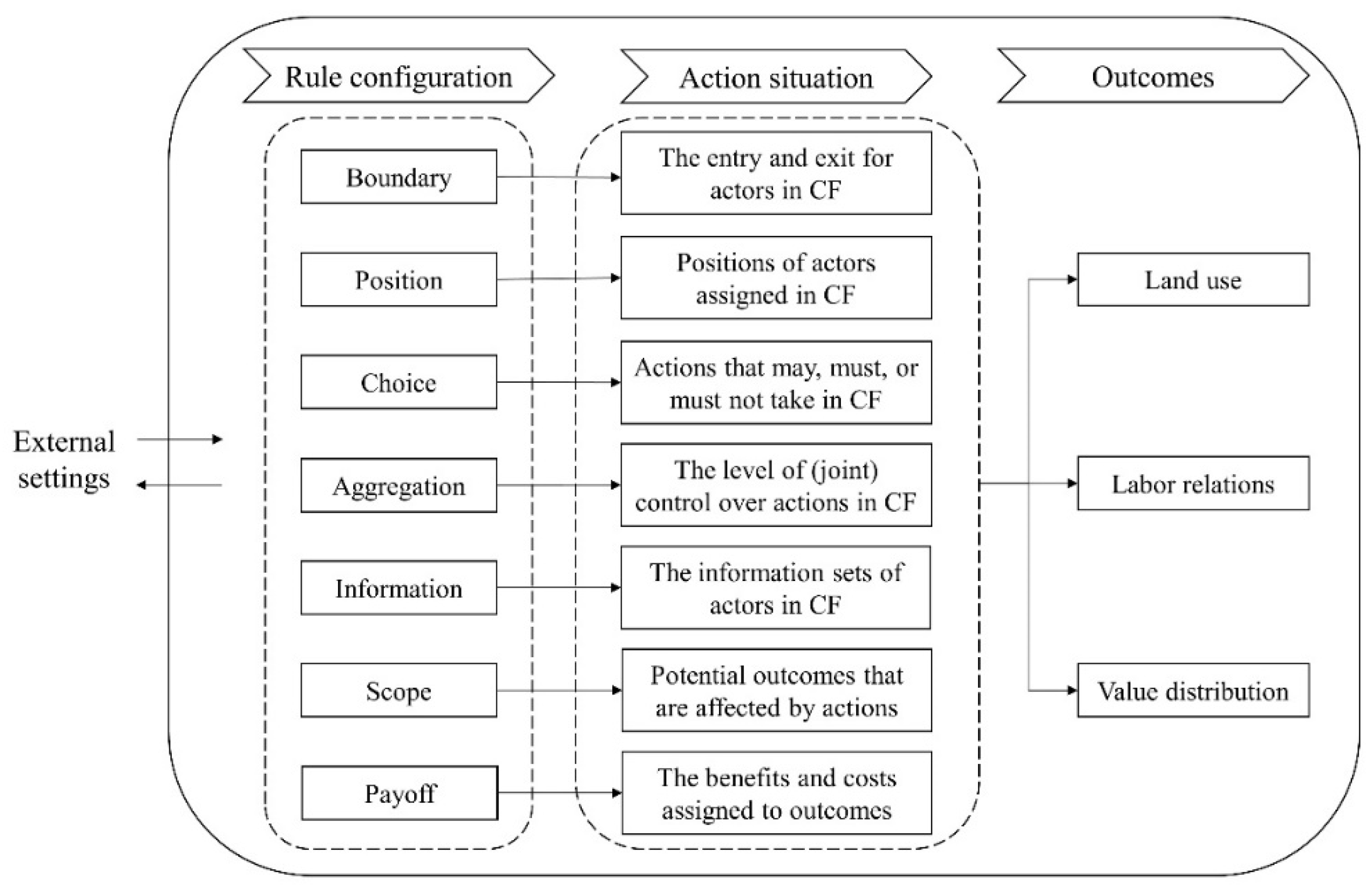

2.2. Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) Framework

3. Methods

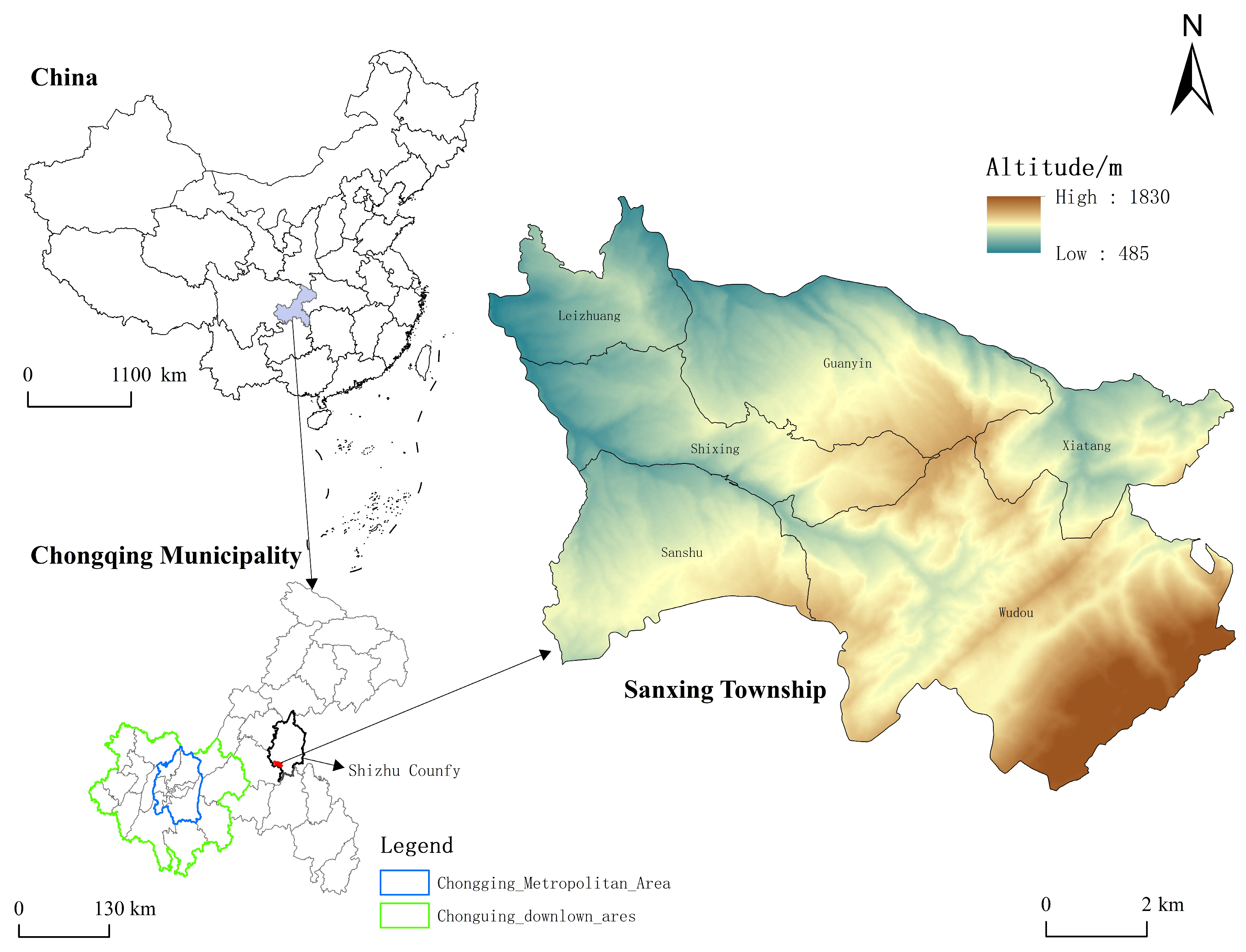

3.1. Case Selection

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3. Operationalization of IAD Framework

4. Results

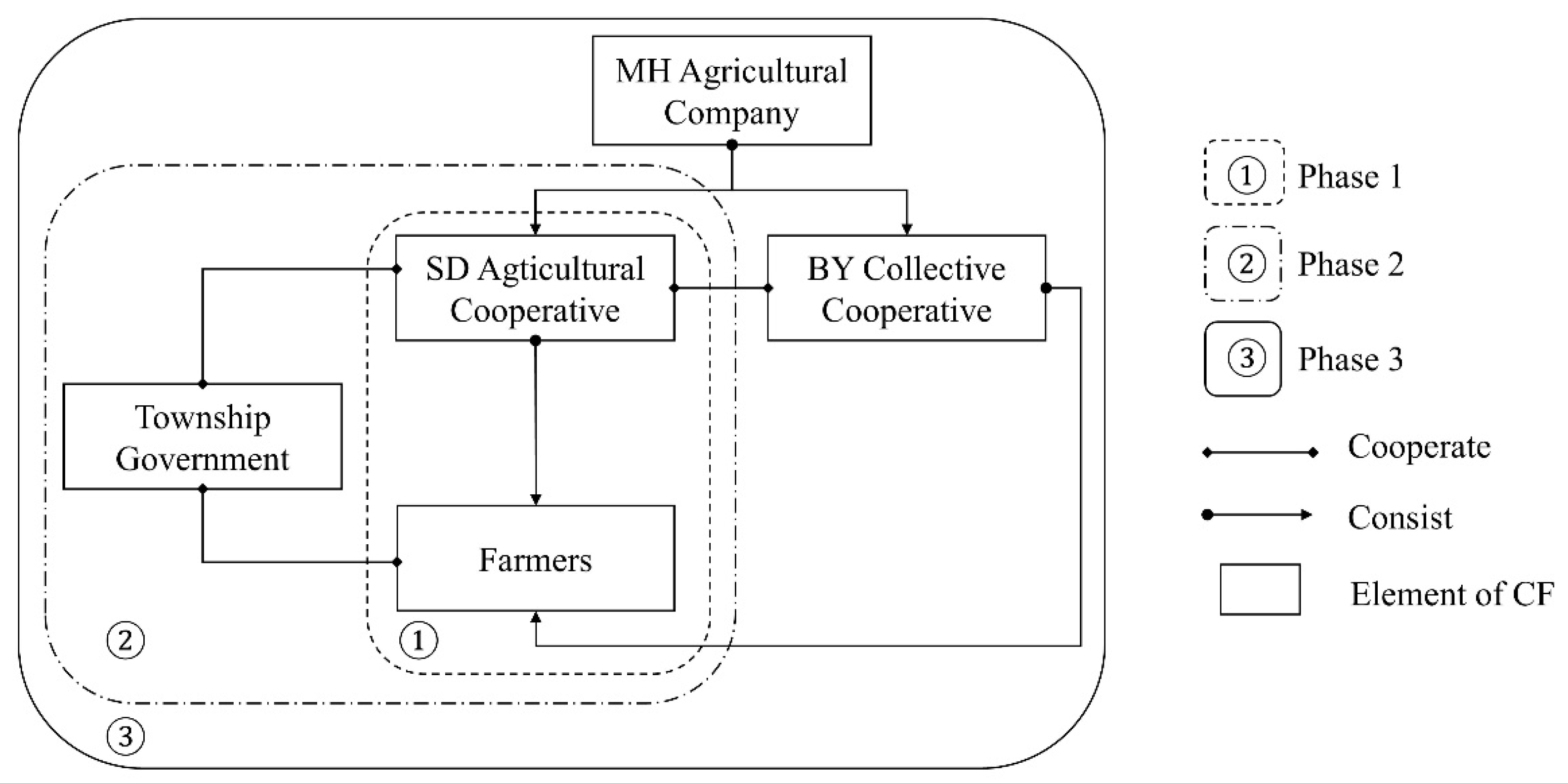

4.1. Evolution of Contract Farming in Sanxing

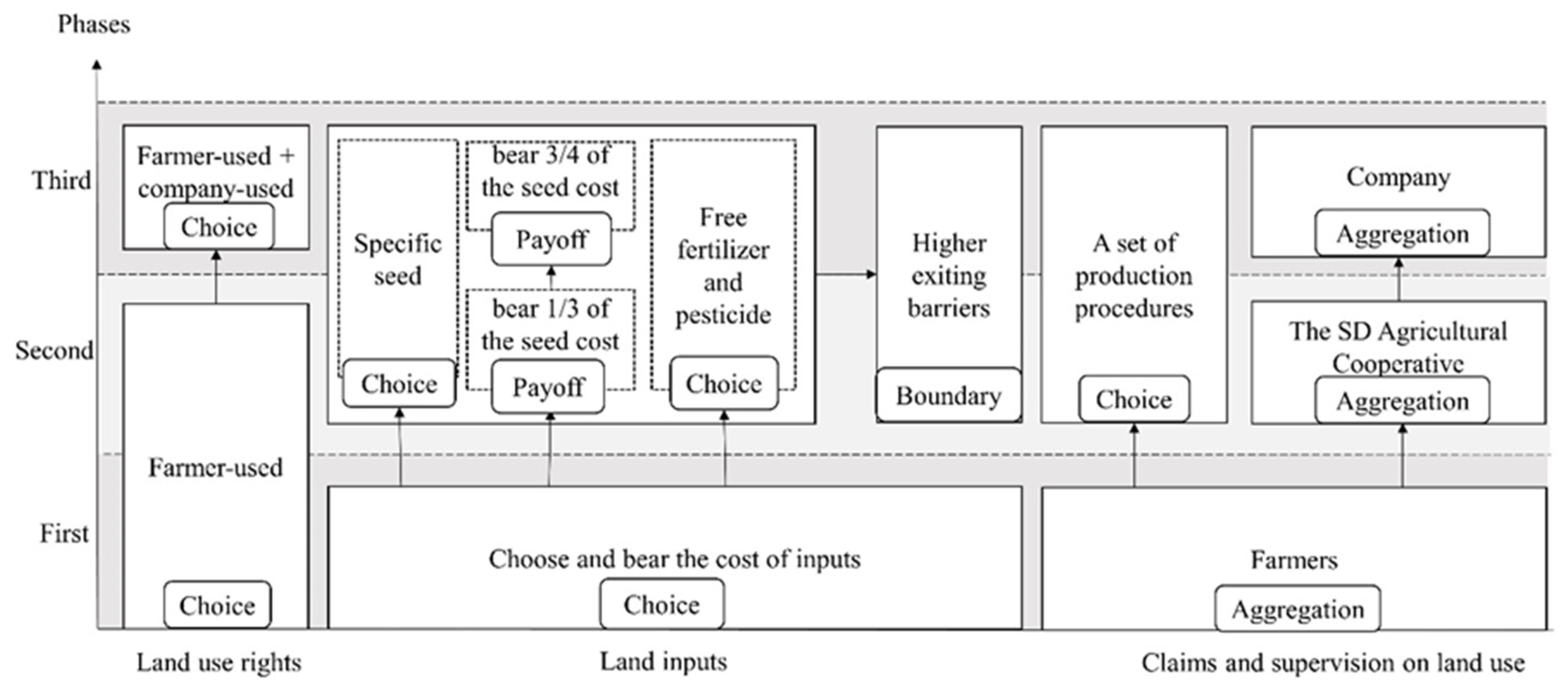

4.2. The Changes in the Rule Configuration of CF in Sanxing Township

4.2.1. Enhanced Land Control

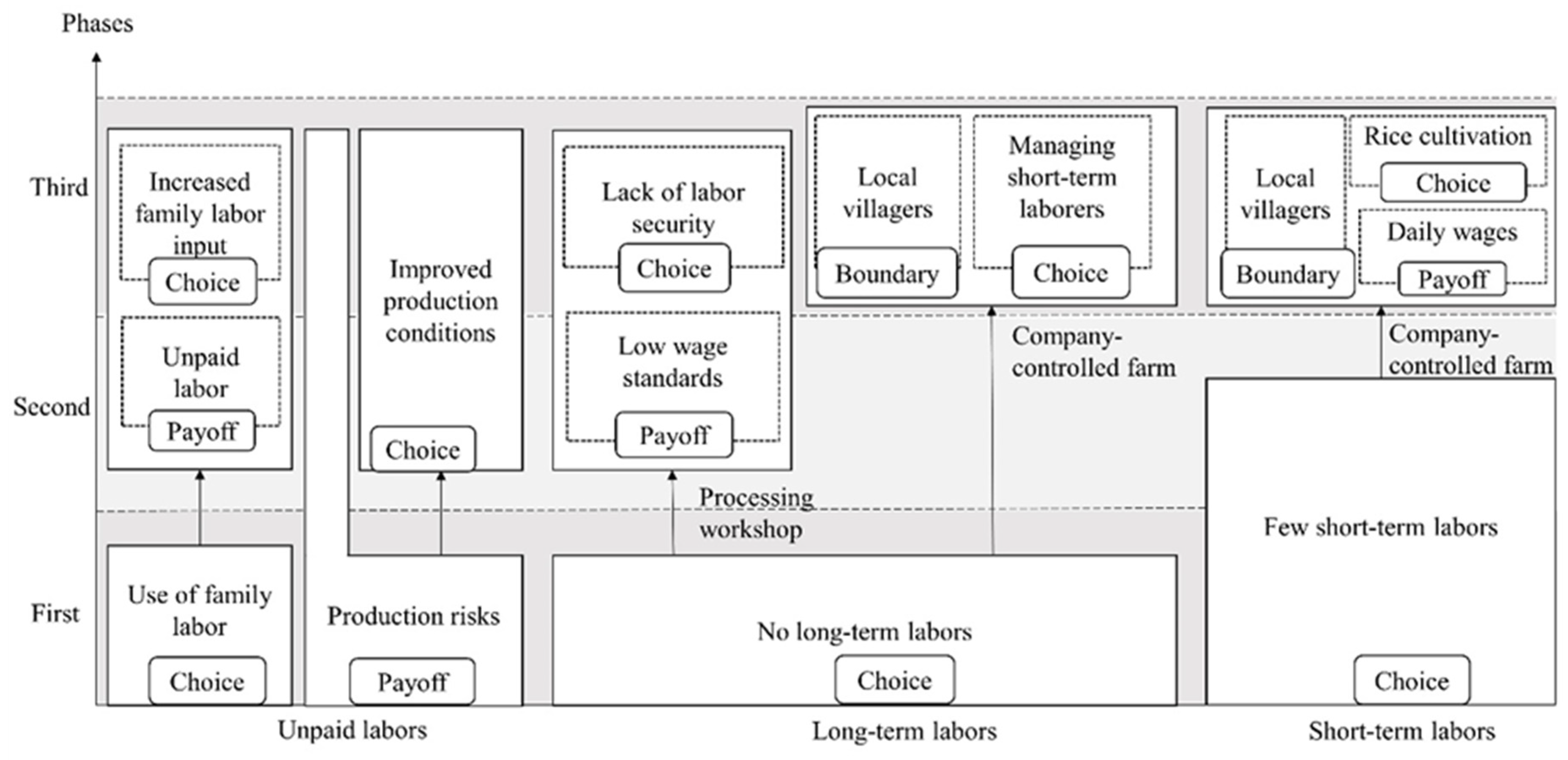

4.2.2. Diversified Labor Regimes

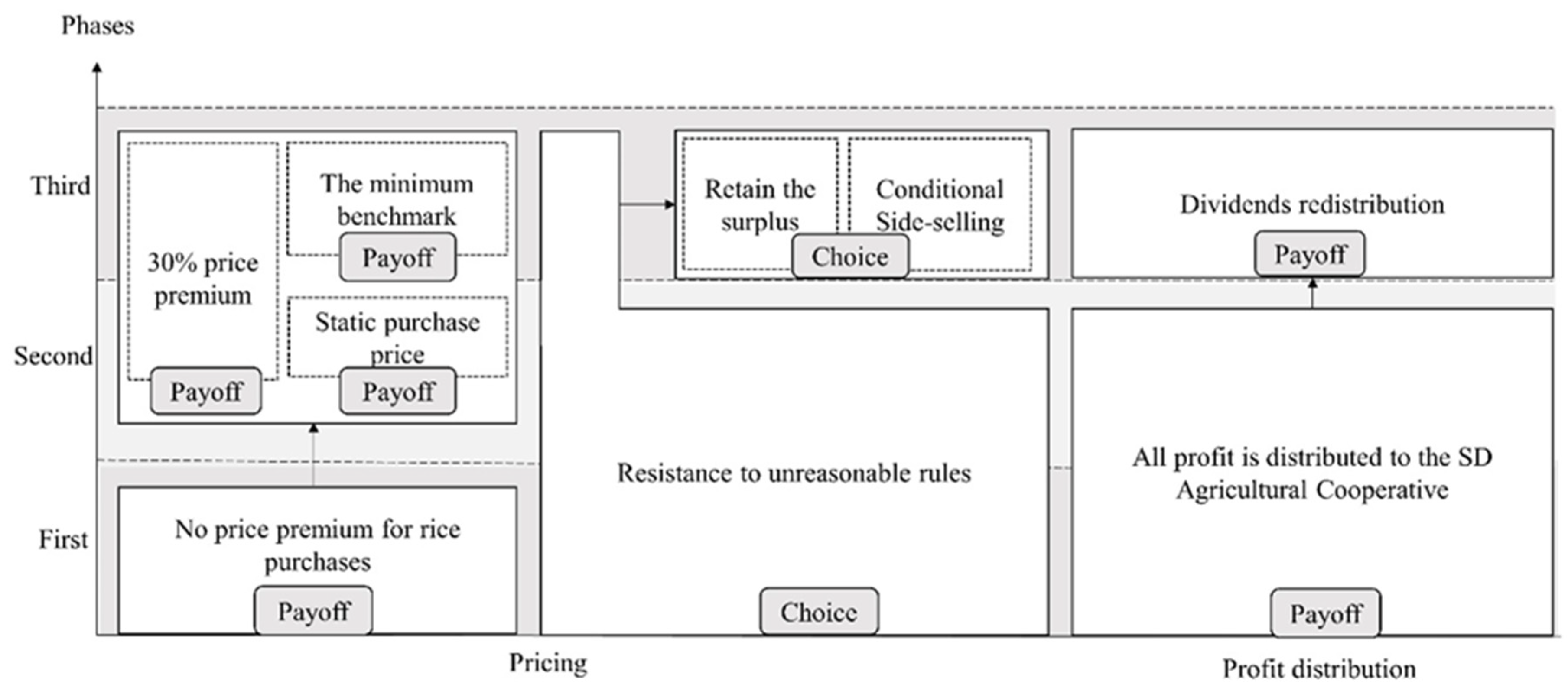

4.2.3. Changing Income Increase

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | 1 mu ≈ 0.067 ha. |

References

- Gatto, M.; Wollni, M.; Asnawi, R.; Qaim, M. Oil Palm Boom, Contract Farming, and Rural Economic Development: Village-Level Evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 2017, 95, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, M.; Vande Velde, K. Contract-Farming in Staple Food Chains: The Case of Rice in Benin. World Dev. 2017, 95, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C.; Lambrecht, I.; Kufoalor, D.S. Limitations of Contract Farming as a Pro-Poor Strategy: The Case of Maize Outgrower Schemes in Upper West Ghana. World Dev. 2018, 102, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, H.A.; de Mey, Y.; Thoron, S.; Demont, M. Inclusiveness of Contract Farming along the Vertical Coordination Continuum: Evidence from the Vietnamese Rice Sector. Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Gerber, J.-D.; Amacker, M.; Haller, T. Who Gains from Contract Farming? Dependencies, Power Relations, and Institutional Change. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 1435–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Pultrone, C. Guiding Principles for Responsible Contract Farming Operations. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i2858e (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; Tsikata, D. Plantations, Outgrowers and Commercial Farming in Africa: Agricultural Commercialisation and Implications for Agrarian Change. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F. As You Sow, So Shall You Reap: The Welfare Impacts of Contract Farming. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1418–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrimali, R. Accumulation by Dispossession or Accumulation without Dispossession: The Case of Contract Farming in India. Hum. Geogr. 2016, 9, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, G.; Vellema, W.; Desiere, S.; Weituschat, S.; D’Haese, M. Contract Farming for Improving Smallholder Incomes: What Can We Learn from Effectiveness Studies? World Dev. 2018, 104, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Vicol, M.; Pol, G. Living under Value Chains: The New Distributive Contract and Arguments about Unequal Bargaining Power. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F. The Political Economy of Contract Farming in China’s Agrarian Transition. J. Agrar. Change 2012, 12, 460–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Mavedzenge, B.; Murimbarimba, F.; Sukume, C. Tobacco, Contract Farming, and Agrarian Change in Zimbabwe. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isager, L.; Fold, N.; Mwakibete, A. Land and Contract Farming: Changes in the Distribution and Meanings of Land in Kilombero, Tanzania. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C. Contract Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Survey of Approaches, Debates and Issues. J. Agrar. Change 2012, 12, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas, A. Land, Development and Contract Farming on the Guatemalan Oil Palm Frontier. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, L.A.; Bonanno, A.M.; Foster, L.C.; Cotula, L. “Inclusive Business” in Agriculture: Evidence from the Evolution of Agricultural Value Chains. World Dev. 2020, 134, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazwi, F.; Chambati, W.; Mudimu, G.T. Tobacco Contract Farming in Zimbabwe: Power Dynamics, Accumulation Trajectories, Land Use Patterns and Livelihoods. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2020, 38, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahati, I.; Martiniello, G.; Abebe, G.K. The Implications of Sugarcane Contract Farming on Land Rights, Labor, and Food Security in the Bunyoro Sub-Region, Uganda. Land Use Policy 2022, 122, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M. Dragon Head Enterprises and the State of Agribusiness in China. J. Agrar. Change 2017, 17, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivramkrishna, S.; Jyotishi, A. Monopsonistic Exploitation in Contract Farming: Articulating a Strategy for Grower Cooperation. J. Int. Dev. 2008, 20, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gereffi, G. Global Value Chains in a Post-Washington Consensus World. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2014, 21, 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N. Collective Action in China’s Recent Collective Forestry Property Rights Reform. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Land Grabbing by Villagers? Insights from Intimate Land Grabbing in the Rise of Industrial Tree Plantation Sector in Guangxi, China. Geoforum 2018, 96, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Long, J.; Zhuo, W. Clan Networks, Spatial Selection, and Farmland Transfer Contracts: Evidence from China. Land 2023, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Liang, Y.; Fuller, A. Tracing Agricultural Land Transfer in China: Some Legal and Policy Issues. Land 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Delgado, M.S. The Transition to Modern Agriculture: Contract Farming in Developing Economies. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Martin, F.; He, X.; Zhen, H.; Pan, X. The Changing Role of Local Government in Organic Agriculture Development in Wanzai County, China. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Can. D Etudes Du Dev. 2019, 40, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Zeng, H. Producing Industrial Pigs in Southwestern China: The Rise of Contract Farming as a Coevolutionary Process. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiao, C. How Agricultural Contracting Services Are Reshaping Small-Scale Household Farming in China. J. Peasant. Stud. 2023, 51, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, Y. Livelihood Resilience and the Generative Mechanism of Rural Households out of Poverty: An Empirical Analysis from Lankao County, Henan Province, China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, X. How Do Farmers Realize Their Rights on the Collective Land in Rural China? An Explanatory Framework for Deconstructing the Subject of Collective Land Ownership. Land 2023, 12, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Kesteloot, C. The Interaction between Local State and Village Collective in China’s Market-Oriented Land Reform: A Case Study in Pidu, Sichuan. J. Peasant. Stud. 2025, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyapong, A.Y. How and Why Large Scale Agricultural Land Investments Do Not Create Long-Term Employment Benefits: A Critique of the ‘State’ of Labour Regulations in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.; Wijaya, H. What Kind of Labour Regime Is Contract Farming? Contracting and Sharecropping in Java Compared. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, P.D.; Watts, M. Living Under Contract: Contract Farming and Agrarian Transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-299-14064-9. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. Contracting Out Solutions: Political Economy of Contract Farming in the Indian Punjab. World Dev. 2002, 30, 1621–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väth, S.J.; Gobien, S.; Kirk, M. Socio-Economic Well-Being, Contract Farming and Property Rights: Evidence from Ghana. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, N.L.; Lund, C. New Frontiers of Land Control: Introduction. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, G. Bitter Sugarification: Sugar Frontier and Contract Farming in Uganda. Globalizations 2021, 18, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural Land System Reforms in China: History, Issues, Measures and Prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key Issues of Land Use in China and Implications for Policy Making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, C.D. ‘Control Grabbing’ and Small-Scale Agricultural Intensification: Emerging Patterns of State-Facilitated ‘Agricultural Investment’ in Rwanda. J. Peasant Stud. 2014, 41, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicol, M. Is Contract Farming an Inclusive Alternative to Land Grabbing? The Case of Potato Contract Farming in Maharashtra, India. Geoforum 2017, 85, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiniello, G.; Owor, A.; Bahati, I.; Branch, A. The Fragmented Politics of Sugarcane Contract Farming in Uganda. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M., Jr.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘from Below’. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiyuan, C. Land Outsourcing and Labour Contracting: Labour Management in China’s Capitalist Farms. J. Agrar. Change 2020, 20, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubb, A. The Value Components of Contract Farming in Contemporary Capitalism. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 722–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Can Capitalist Farms Defeat Family Farms? The Dynamics of Capitalist Accumulation in Shrimp Aquaculture in South China. J. Agrar. Change 2015, 15, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicol, M.; Fold, N.; Hambloch, C.; Narayanan, S.; Pérez Niño, H. Twenty-Five Years of Living Under Contract: Contract Farming and Agrarian Change in the Developing World. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest Zhang, Q.; Donaldson, J.A. From Peasants to Farmers: Peasant Differentiation, Labor Regimes, and Land-Rights Institutions in China’s Agrarian Transition. Polit. Soc. 2010, 38, 458–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F.; Schoneveld, G. Oil Palm Contract Farming in Brazil: Labour Constraints and Inclusivity Challenges. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambloch, C. Contract Farming and Everyday Acts of Resistance: Oil Palm Contract Farmers in the Philippines. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebbin, A.; Hassler, M. Farmers’ Producer Companies in India: A New Concept for Collective Action? Environ. Plan A 2012, 44, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isager, L.; Fold, N.; Nsindagi, T. The Post-Privatization Role of Out-Growers’ Associations in Rural Capital Accumulation: Contract Farming of Sugar Cane in Kilombero, Tanzania. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Yuan, P. Rural Cooperative in China. Chin. Econ. 2014, 47, 32–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.F.; Donaldson, J.A. Farmers’ Cooperatives in China: A Typology of Fraud and Failure. China J. 2017, 78, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairong, Y.; Yiyuan, C. Agrarian Capitalization without Capitalism? Capitalist Dynamics from Above and Below in China. J. Agrar. Change 2015, 15, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-39734-6. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, M.C.; Della Giusta, M.; Kambhampati, U.S. Formal and Informal Institutions and Development. World Dev. 2010, 38, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yao, Y. Informal Institutions, Collective Action, and Public Investment in Rural China. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 109, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.Y.; Beaudreau, A.H.; Saas, E.M.; Carothers, C. Engaging Formal and Informal Institutions for Stewardship of Rockfish Fisheries in the Gulf of Alaska. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, O.; Nier, S.; Tamásy, C. Re-Configuring Rural Economies–The Interplay of Institutions in Three Agri-Food Production Systems. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 92, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, Y. Fragmented Peri-Urbanisation Led by Autonomous Village Development under Informal Institution in High-Density Regions: The Case of Nanhai, China. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, H.; Glückler, J. Institutional Change in Economic Geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.K. How to Make Forest Governance Reform Real? Formal and Informal Institutions during Implementation of the Forest Rights Act 2006 in India. Environ. Dev. 2022, 43, 100729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G.M. What Are Institutions? J. Econ. Issues 2006, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, F. Analysing Decentralised Natural Resource Governance: Proposition for a “Politicised” Institutional Analysis and Development Framework. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.D. An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekola, O.; Krigsholm, P.; Riekkinen, K. Adapted Institutional Analysis and Development Framework for Understanding Customary Land Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa–A Case Study from Nigeria. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4008-3173-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Do Institutions for Collective Action Evolve? J. Bioeconomics 2014, 16, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, R.; Chiodo, E.; Fantini, A. Tourism Transition in Peripheral Rural Areas: Theories, Issues and Strategies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 68, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J. Families and Local Opportunities in Rural Peripheries: Intersections between Resources, Ambitions and the Residential Environment. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 66, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latocha-Wites, A.; Kajdanek, K.; Sikorski, D.; Tomczak, P.; Szmytkie, R.; Miodońska, P. Global Forces and Local Responses–A “Hot-Spots” Model of Rural Revival in a Peripheral Region in the Central-Eastern European Context. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.R.; Shumway, J.M. Sampling Our World. Res. Methods Geogr. A Crit. Introd. 2010, 6, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive Sampling: Complex or Simple? Research Case Examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, S.M.; Carrington, J.M.; Badger, T.A. Two Strategies for Qualitative Content Analysis: An Intramethod Approach to Triangulation. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natow, R.S. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Studies Employing Elite Interviews. Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miani, A.M.; Karami Dehkordi, M.; Siamian, N.; Lassois, L.; Tan, R.; Azadi, H. Toward Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Approach: Application of Grounded Theory in Ghazni Province, Afghanistan. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 154, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Zhou, T.; Qu, Y. Do Decaying Rural Communities Have an Incentive to Maintain Large-Scale Farming? A Comparative Analysis of Farming Systems for Peri-Urban Agriculture in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 136590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Determining Growers’ Participation in Contract Farming in Punjab. Econ. Polit. Weekly 2016, 51, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Bloem, J.R. Does Contract Farming Improve Welfare? A Review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, H.H. The Problem of Low Contract Compliance Rate in Grain Transactions in China. China Int. J. 2013, 11, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R. Cashing in or Driving Development? Cross-Border Traders and Maize Contract Farming in Northeast Laos. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélair, J. Farmland Investments in Tanzania: The Impact of Protected Domestic Markets and Patronage Relations. World Dev. 2021, 139, 105298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcmichael, P. Value-Chain Agriculture and Debt Relations: Contradictory Outcomes. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. State Power and Village Cadres in Contemporary China: The Case of Rural Land Transfer in Shandong Province. J. Contemp. China 2015, 24, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; O’Brien, K.J.; Zhang, L. How Grassroots Cadres Broker Land Taking in Urbanizing China. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mou, Y. The Paradigm Shift in the Disciplining of Village Cadres in China: From Mao to Xi. China Q. 2021, 248, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up Initiatives and Revival in the Face of Rural Decline: Case Studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Rogers, S. Networking Shangnan’s Tea: Socio-Economic Relations, Commodities and Agrarian Change in Rural China. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 1405–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Ye, J.; Wang, C. Embedding the Poor into the Industrial System: What We Can Learn from Poverty Alleviation through Industrial Development in China. J. Peasant Stud. 2023, 50, 2750–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Informants | Interview Outline | Quantity | Code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government officials | General social–economic status of the township Rural and agricultural development policies Implementation of rice CF Political support for the development of rice CF Potential conflict in rice CF Land use change in the township | 3 interviews | G01–G03 |

| Managers of the SD cooperatives | Development of cooperatives Upstream and downstream activities of rice CF Land and labor in rice CF Capital input from various sources Restrictions on the development of rice CF Profit distribution mechanism of rice CF | 2 interviews | M01–M02 |

| Village cadres | Overview of village agricultural development Overview of villagers’ participation in rice CF Supervision on land and labor use in rice CF Profit distribution mechanism of rice CF Use of village collective income Potential conflicts in rice CF and solutions | 2 interviews | V01–V02 |

| Workers involved in rice CF | Perceptions towards rice CF Work description Changes in livelihood activities and income structure | 3 interviews | W01–W03 |

| Contract farmers | Individual attributes Perceptions towards rice CF Changes in land use and labor arrangements Changes in livelihood activities and income structure Violation of contracts | 16 interviews | C01–C16 |

| Rule Type | Definition | Indicators of Rule Change | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boundary | Who is allowed or excluded from participating in CF, and under what conditions? | Introduction of new land thresholds or minimum landholding requirements; Restrictions based on gender, age, or rural household registration status; Minimum required duration of participation for contract farmers; Conditions for exiting contract farming arrangements; | Semi-structured interviews with farmers, managers of the SD cooperatives, and village cadres; Analysis of secondary data, such as the statistics of rice growers participating in CF in Sanxing and CF contract terms. |

| Position | Who holds which positions, and what authority do those positions entail? | The emergence of new actors; Shifting roles of actors; Reallocation of authority or responsibilities; | Semi-structured interviews with various actors to explore their roles and positions within CF; Participant observation on the authority and responsibilities assigned to different actors; Comparison of various actors’ narratives, such as contract farmers vs. managers |

| Choice | What actions may, must, or must not be taken regarding activities in CF? | Shifts in autonomy over land use; Introduction of labor requirements; Changing contract obligations over production or delivery; More prescriptive production guidelines and external supervision; | Semi-structured interviews with a range of actors to explore their perceived autonomy over land and labor use; Analysis of secondary data, especially restrictions or obligations imposed on contract farmers in contract texts; Participant observation on production practices and supervision activities; |

| Aggregation | How are collective decisions made, and whose preferences matter? | Changes in actors who hold authority over key decisions; Inclusion or exclusion of different actors in decision-making; Changes in which preferences are prioritized in decision-making; Formalization of decision-making processes; | Semi-structured interviews with key actors about decision-making processes; Participant observation on formal or informal decision-making meetings; Analysis of second-hand data, such as meeting records; Comparison of various narratives, such as interviews from contract farmers vs. the text of official documents; |

| Information | Who has access to information and who controls its flow? | Reduction or increase in information asymmetries; Formation of new communication channels; Changes in transparency or secrecy of information; | Semi-structured interviews with key actors on the disclosure and dissemination of information; Analysis of secondary data, such as formal or informal notices and brochures of rice CF; Participant observation on relevant information platforms or social media; |

| Scope | What are the formal or expected outcomes from the CF? | economic and social outcomes of CF; Broadening/narrowing of expected benefits of CF; Introduction of new risks or benefits compared to traditional rice production; | Semi-structured interviews with key actors concerning the shifts in expected and actual benefits Analysis of second-hand data, such as work reports of the Sanxing government; Comparison of various actors, such as contract farmers vs. normal farmers; |

| Payoff Rules | How are benefits, risks, and costs distributed among actors? | The shift in production risk; Changes in the mechanism of redistribution; Hidden financial penalty or side Payments; | Semi-structured interviews with key actors concerning the redistribution mechanism and their actual Income; Analysis of second-hand data, such as contract terms on pricing, penalties, and bonuses, and statistics of public Funds; |

| Village | Land Area Involved (mu) | Number of Farmers Involved | Size of Land Plots (mu) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leizhuang | 874 | 165 | 1–35 |

| Shixing | 621 | 171 | 0.5–15 |

| Guanyin | 303 | 106 | 0.5–5 |

| Sanshu | 281 | 68 | 1–10 |

| Wudou | 157 | 43 | 0.5–20 |

| Xiatang | 195 | 46 | 0.5–7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Busck, A.G.; Kristensen, S.B.P. Integrating Farmers into Contract Farming in Peripheral Rural Areas in China. Land 2025, 14, 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050976

Zhang J, Busck AG, Kristensen SBP. Integrating Farmers into Contract Farming in Peripheral Rural Areas in China. Land. 2025; 14(5):976. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050976

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jingyu, Anne Gravsholt Busck, and Søren Bech Pilgaard Kristensen. 2025. "Integrating Farmers into Contract Farming in Peripheral Rural Areas in China" Land 14, no. 5: 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050976

APA StyleZhang, J., Busck, A. G., & Kristensen, S. B. P. (2025). Integrating Farmers into Contract Farming in Peripheral Rural Areas in China. Land, 14(5), 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050976