The Evolution of Plot Morphology and Design Strategies in Built Heritage Renewal in Central Shanghai from the Perspective of Sharing Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

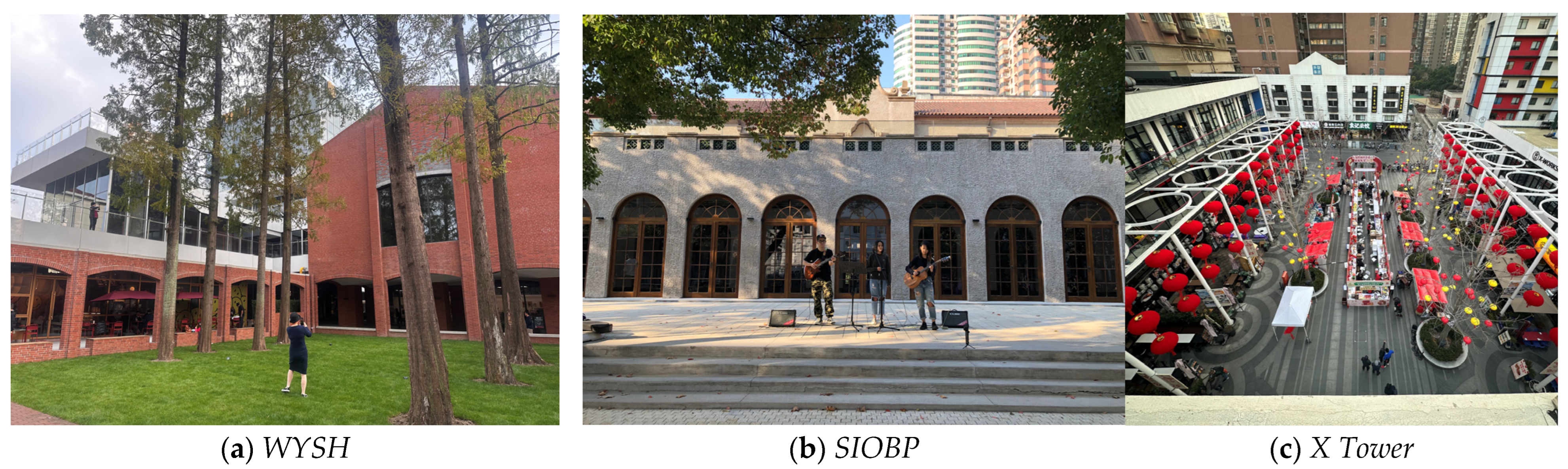

2.1. The Sharing Economy and the Sharing City

2.2. Trends and Features of Built Heritage Renewal: From Creative Park Model to a More Sharing Appraoch

2.3. Plot Morphology Evolution and Renewal Methods

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study and Criteria for Selection

3.2. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Morphological Analysis Results

4.2. Case-Specific Analysis Results

5. Discussion

5.1. From the Sharing Economy to the Sharing City

5.2. New Features in the Evolution of Plot Morphology: Three Types of Boundary Change Bring About an Increase in the Street Frontage Index and the Emergence of POPS

5.3. “Sharing by Transfer” and “Architecture for the Other”

6. Conclusions

- The evolution of renewal strategies: Functional planning is no longer exclusively centered on a singular economic gain but rather prioritizes a multifaceted value proposition. The combination of online and offline components, coupled with the exploration of traffic and sharing, progressively impacts conventional functional positioning.

- Modification of Plot and Architectural Morphology: Previously enclosed sites have been changed through intentional design strategies into more open physical layouts that provide new activity zones and spatial images. The physical removal of borders has broken vertical constraints and improved space accessibility.

- Changes in Spatial Utilization: Areas accommodating a wider spectrum of users and emphasizing service for others have become more common. Architectural spaces are being used more frequently through several modalities—such as allocated use, borrowed use, and co-use—to accommodate a greater number of individuals, therefore creating an innovative route for renewal based on transfer for the advantage of others.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In May 2017, Shanghai proposed for the first time that there should be “readable buildings, walkable neighborhoods, and a city with warmth”. The phrase “readable buildings”, with its literary quality and profound respect for the city’s history, resonated widely and sparked considerable public interest. |

| 2 | Shanghai has officially issued the “Implementation Measures for Urban Renewal in Shanghai” (Shanghai Government Document No. 20, 2015) and introduced a series of supporting documents, thereby formally and systematically regulating urban renewal work. |

| 3 | On May 9, 2002, the Ministry of Land and Resources issued the Provisions on the Assignment of State-owned Land Use Rights through Bidding, Auction, and Listing (Decree No. 11), which came into effect on 1 July 2002. This decree fully established a system for the transfer of land use rights for operational purposes through bidding, auction, or listing and clearly stipulated that all types of operational land—such as those for commercial, tourism, entertainment, and commodity housing purposes—must be assigned through one of these market-based methods. |

| 4 | WYSH, short for Wuyi Shanghai, is located in Changning District, Shanghai, between Wuyi Road and Zhaohua Road. It brings together old garden villas and a number of historic buildings predominantly showcasing Spanish, English country, and Art Deco styles. It is one of the urban renewal initiatives in Changning District. |

| 5 | The Shanghai Municipal Government issued the “Opinions on Promoting Saving and Intensive Utilisation of Industrial Land and Accelerating the Development of Modern Service Industry” (Hufuban [2008] No. 37), which puts forward the policy of the three principles of unchanged property owner, unchanged building structure and unchanged land use nature. The policy is often referred to as the “Three No Change” policy. |

| 6 | Since 2014, Shanghai’s land planning authorities have issued a series of documents, including (1) Implementation Measures for Revitalizing Stock Industrial Land in Shanghai (Trial) (Hufuban [2014] No. 25); (2) Shanghai Urban Renewal Implementation Measures (Hufufa [2015] No. 20). |

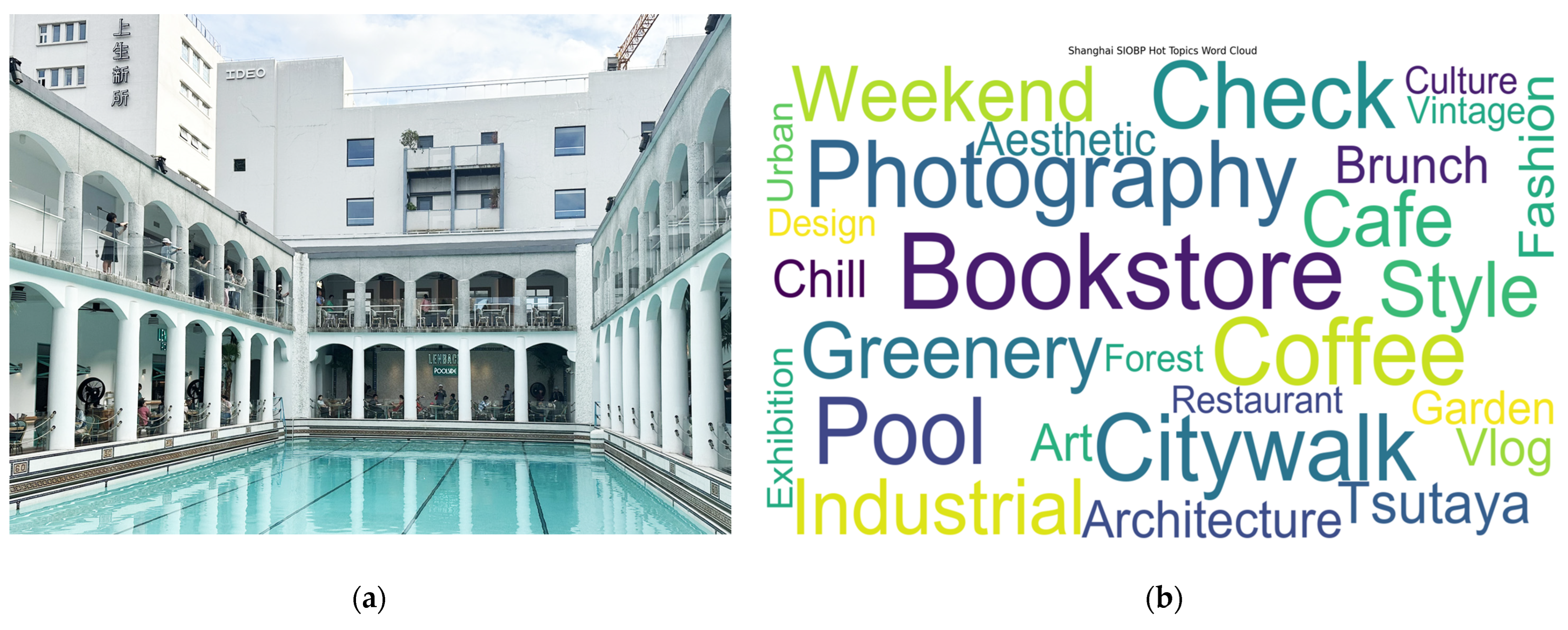

| 7 | SIOBP, short for Shanghai Institute of Biological Products and also known as Columbia Circle, is an urban renewal project located at 1262 Yan’an West Road. It includes Sunke Villa, Columbia Country Club, Navy Club with its attached swimming pool, and several industrial buildings. The property rights are retained by the Shanghai Biological Products Research Institute, while the land use has transitioned from educational and research purposes to a combination of commercial, office, and community service uses, altering the usage rights of the parcel. |

| 8 | Tianditu is the public version of the national geographic information public service platform led by the National Administration of Surveying, Mapping, and Geoinformation. It is an important part of “Digital China” and aims to provide authoritative, reliable, and unified geographic information services to the public, enterprises, professional departments, and government agencies. Website: https://www.tianditu.gov.cn/ (accessed on 20 April 2025). |

| 9 | Attractive or interesting enough to be suitable for photographing and posting on the social media service Instagram. Cambridge English Dictionary. |

| 10 | Since April 2023, the “Half Suzhou River” public welfare market at X Tower provides free venue space for monthly community activities, featuring public welfare stalls and a “circular marketplace” for household item reuse. Based on the interview with the architects, developers, property managers, and residents. |

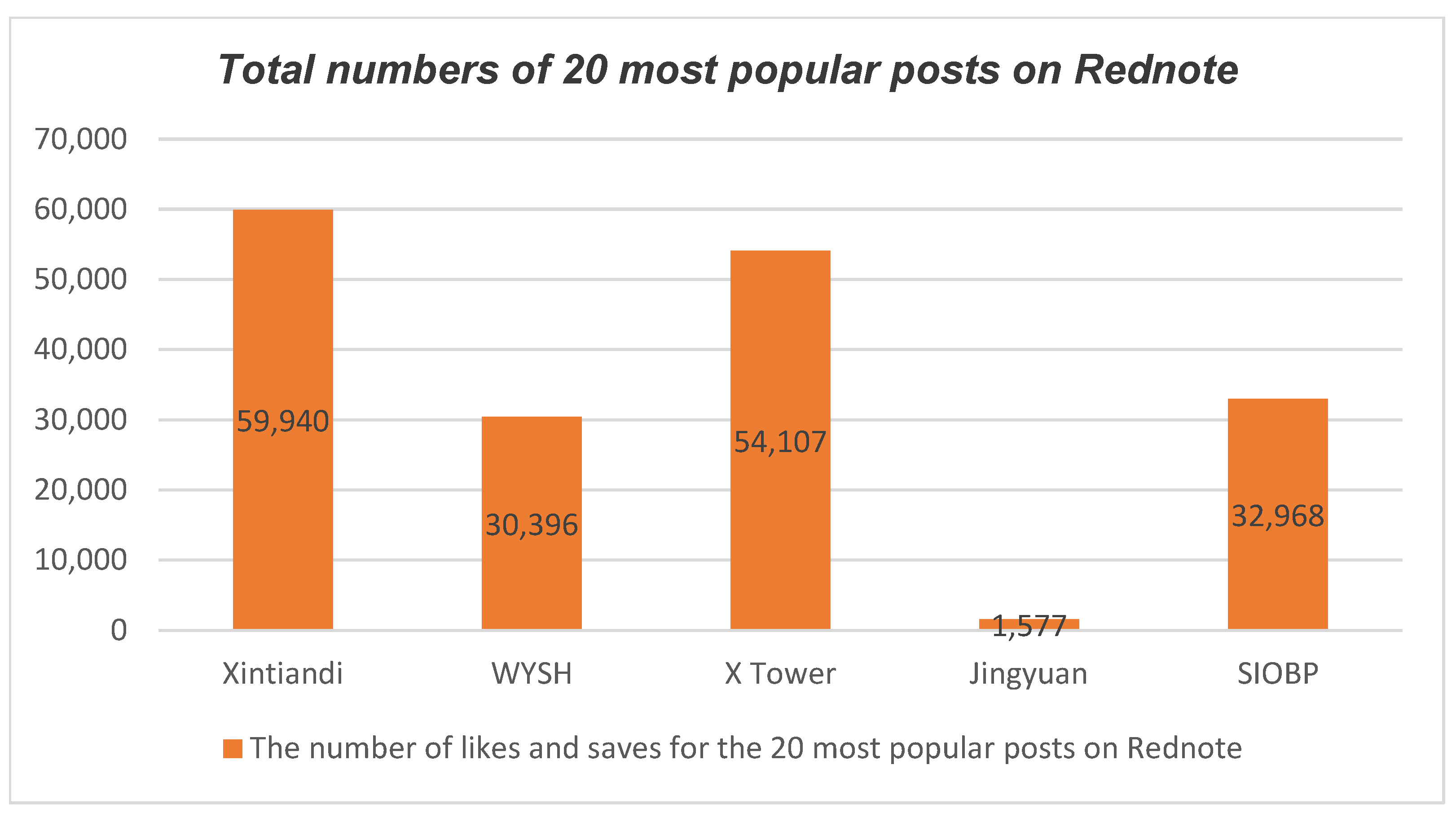

| 11 | Founded in 2013, Rednote is not merely a content-sharing app but has gradually evolved into a lifestyle platform centered around content-based social interaction. It has significantly shaped young people’s consumer perceptions, aesthetic standards, and modes of social expression, becoming a quintessential example of a new-generation “discursive space”. |

| 12 | Based on the structured interviews with the developers, designers, and merchants of WYSH. Different positions on issues related to governance models and co-management. |

References

- Rey-Pérez, J.; Díaz-Borrego, J.; Fernández Muñoz, C.; de la Fuente Peñalver, A. The Definition of the Heritage Status of Modern Residential Architecture from a Multi-Scalar and Perceptual Approach. A Heritage Perspective in the Case Study of the Neighbourhood of El Plantinar in Seville (Spain). Land 2022, 11, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Lee, J. Modern Industrial Heritage as Cultural Mediation in Urban Regeneration: A Case Study of Gunsan, Korea, and Taipei, Taiwan. Land 2023, 12, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhzoumi, J.; Al-Harithy, H.; Bazzi, M. Contextualizing UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape Approach: A Framework for Identifying Modern Heritage in Post-Blast Beirut. Land 2024, 13, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, M. Exploring a Low-Carbon Oriented Strategy for Urban Renewal: From “Demolition, Redevelopment and Preservation” to “Preservation, Transformation and Demolition”. World Archit. 2022, 8, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Križnik, B. Local Responses to Market-Driven Urban Development in Global Cities. Teor. Praksa 2014, 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Zang, T.; Xing, J.; Ikebe, K. Spatial Distribution of Urban Heritage and Landscape Approach to Urban Contextual Continuity: The Case of Suzhou. Land 2023, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, M.; Chen, Y.-F.; Zhai, Z.; Du, J. Investigating the Critical Issues in the Conservation of Heritage Building: The Case of China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigyasu, R. The Intangible Dimension of Urban Heritage. In Reconnecting the City; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, W.; Mu, J.; Cheng, X. Optimizing Supply Chain Financial Strategies Based on Data Elements in the China’s Retail Industry: Towards Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, J.; Dou, Q.; Fu, F.; Shi, Y. Digital Footprint as a Public Participatory Tool: Identifying and Assessing Industrial Heritage Landscape through User-Generated Content on Social Media. Land 2024, 13, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, F. Property-Led Redevelopment in Post-Reform China: A Case Study of Xintiandi Redevelopment Project in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Sharing: Table 1. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.; Agyeman, J. Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780262329705. [Google Scholar]

- Chris, W.; Lai, L.W.-C. Property Rights, Planning and Markets: Managing Spontaneous Cities; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, S.K.; Lehner, M. Defining the Sharing Economy for Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barile, S.; Ciasullo, M.V.; Iandolo, F.; Landi, G.C. The City Role in the Sharing Economy: Toward an Integrated Framework of Practices and Governance Models. Cities 2021, 119, 103409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasze, G.; Webster, C.; Frantz, K. Private Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 9781134294466. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.T.; Kong, H.; Wu, R.; Sui, D.Z. Ridesourcing, the Sharing Economy, and the Future of Cities. Cities 2018, 76, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B.; Muñoz, P. Sharing Cities and Sustainable Consumption and Production: Towards an Integrated Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Z. ‘Sharing’ as a Critical Framework for Waterfront Heritage Regeneration: A Case Study of Suzhou Creek, Shanghai. Land 2024, 13, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, X. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Community Public Open Space Renewal: A Case Study of the Ruijin Community, Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Ding, Y.; Shang, L.; Wang, D.; Cao, X.; Wang, S.; Bonatz, N.; Wang, L. Sustainability-Oriented Urban Renewal and Low-Impact Development Applications in China: Case Study of Yangpu District, Shanghai. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2018, 4, 05017006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Leung, H.H. Exploring Participatory Microregeneration as Sustainable Renewal of Built Heritage Community: Two Case Studies in Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xiong, Q.; Huang, G.; Du, B.; Feng, H. How to Share Benefits of Old Community Renewal Project in China? An Improved Shapley Value Approach. Habitat. Int. 2022, 126, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Jia, R.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Najafi, A.; Attard, M. Big-Data-Driven Approach and Scalable Analysis on Environmental Sustainability of Shared Micromobility from Trip to City Level Analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 115, 105803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Cao, K.; Kwan, M.P.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, Q. Measuring the Age-Friendliness of Streets’ Walking Environment Using Multi-Source Big Data: A Case Study in Shanghai, China. Cities 2024, 148, 104829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S. Artists and Shanghai’s Culture-Led Urban Regeneration. Cities 2016, 56, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. “Art in Capital”: Shaping Distinctiveness in a Culture-Led Urban Regeneration Project in Red Town, Shanghai. Cities 2009, 26, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conzen, M.P. Thinking About Urban Form: Papers on Urban Morphology, 1932–1998; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J.W.R. British Urban Morphology: The Conzenian Tradition. Urban Morphol. 2001, 5, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickert, C.; Karssenberg, H. Street-Level Architecture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781003041887. [Google Scholar]

- Felson, M.; Spaeth, J.L. Community Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A Routine Activity Approach. Am. Behav. Sci. 1978, 21, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; HarperBusiness: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M. Sharing Economy: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Why Not Share Rather than Own? Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2007, 611, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantiou, I.; Marton, A.; Tuunainen, V.K. Four-Models-of-Sharing-Economy-Platforms. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ranchordás, S.; Goanta, C. The New City Regulators: Platform and Public Values in Smart and Sharing Cities. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2020, 36, 105375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Designing Resilient and Sustainable Communities. In Social Ecology in the Digital Age; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 265–317. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vergara, J.I.; Ginieis, M.; Papaoikonomou, E. The Emergence of the Sharing City: A Systematic Literature Review to Understand the Notion of the Sharing City and Explore Future Research Paths. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. The “Entrepreneurial State” in “Creative Industry Cluster” Development in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2010, 32, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Martínez, P. From Verifiable Authenticity to Verisimilar Interventions: Xintiandi, Fuxing SOHO, and the Alternatives to Built Heritage Conservation in Shanghai. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yin, D.; Zhu, H. Urban Regeneration and Emotional Politics of Place in Liede Village, Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 103, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Shen, Z.; Lau, S.S.Y. Sustainability Issues in the Industrial Heritage Adaptive Reuse: Rethinking Culture-Led Urban Regeneration through Chinese Case Studies. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Fu, X.; Han, Q.; Huang, R.; Zhuang, T. Research on the Collaborative Governance of Urban Regeneration Based on a Bayesian Network: The Case of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Duan, J. What They Talk about When They Talk about Urban Regeneration: Understanding the Concept ‘Urban Regeneration’ in PRD, China. Cities 2022, 130, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdini, G. Is the Incipient Chinese Civil Society Playing a Role in Regenerating Historic Urban Areas? Evidence from Nanjing, Suzhou and Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Li, B.; Shen, G.; Zhou, L. Ally, Deterrence, or Leverage in the Tripartite Game? The Effects of Indirect Stakeholders in Historic Urban Regeneration. Cities 2024, 149, 104931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarepour Sohi, S.; Banihashemi, S.; Sheikhkhoshkar, M.; Abdollahi Roshan, P. From Data to Design: Social Network Insights for Urban Design and Regeneration. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 1377–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Burgess, G.; Sielker, F. Political Mobilisation and Institutional Layering in Urban Regeneration: Transformation of Land Redevelopment Governance in China. Cities 2023, 141, 104508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hartog, H. Shanghai’s Regenerated Industrial Waterfronts: Urban Lab for Sustainability Transitions? Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Jian, I.Y.; Chan, E.H.W.; Chen, W. Cultural Regeneration and Neighborhood Image from the Aesthetic Perspective: Case of Heritage Conservation Areas in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2022, 129, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Ho, D.C.W.; Lai, L.W.C.; Chau, K.W. Public Preferences for Government Supply of Public Open Space: A Neo-Institutional Economic and Lifecycle Governance Perspective. Cities 2023, 141, 104463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, T. Regeneration towards Suitability: A Decision-Making Framework for Determining Urban Regeneration Mode and Strategies. Habitat Int. 2023, 138, 102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolici, R.; Leali, G.; Mirandola, S. Reusing Built Heritage. Design for the Sharing Economy. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Yang, R.; Yang, X. Evaluation of Architectural Perception in Urban Industrial Heritage Buildings Based on Eye Tracking Technology. Hum. Factors Archit. Sustain. Urban Plan. Infrastruct. 2024, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, S.; Cheng, A. Industrial Heritage and Urban Renewal: A Quantitative Study and Optimization Strategies for Chengdu East Suburb Memory. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1537211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favargiotti, S. Renewed Landscapes: Obsolete Airfields as Landscape Reserves for Adaptive Reuse. J. Landsc. Archit. 2018, 13, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, P.; Sirel, A. Adaptive Reuse as a Tool for Sustainability: Tate Modern and Bilgi University Cases. Proc. Int. Conf. Contemp. Aff. Archit. Urban.-ICCAUA 2022, 5, 554–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. Russell Thomas The Redevelopment and Repurposing of Historic Gas Sites. In Economic History of the European Energy Industry; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 145–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kip, M.; Oevermann, H. Neighbourhood Revitalisation and Heritage Conservation through Adaptive Reuse: Assessing Instruments for Commoning. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 13, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. Aspects of Urban Form. Urban Morphol. 2009, 13, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. Plots, Property and Behaviour. Urban Morphol. 2018, 22, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümtürk, O.; Karakiewicz, J.; de Haan, F.J. Measuring the Impact of Plot Types on Physical Change: A Diachronic Analysis of Urban Form Evolution in New York, Melbourne and Barcelona. Cities 2024, 154, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E. Synthesis, Landscapes and Sustainable Cities. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267821 (accessed on 20 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Scheer, B.C.; Ferdelman, D. Inner-City Destruction and Survival: The Case of Over-the-Rhine, Cincinnat. Urban Morphol. 2001, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, B.C. The Epistemology of Urban Morphology. Urban Morphol. 2016, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Davies, S.N.G.; Chau, K.W.; Ching, K.S.T.; Chua, M.H.; Leung, H.F.; Lorne, F.T. The Determination of the “True” Property Boundary in Planned Development: A Coasian Analysis. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2018, 61, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C. Property Rights and the Public Realm: Gates, Green Belts, and Gemeinschaft. Environ. Plan B Plan Des. 2002, 29, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, E.; Marcus, L.; Berghauser Pont, M.; Stavroulaki, I.; Bolin, D. Structure of Plot Systems and Economic Activity in Cities: Linking Plot Types to Retail and Food Services in London, Amsterdam and Stockholm. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Combining the Historico-Geographical and Configurational Approaches to Urban Morphology: The Historical Transformations of Ludlow, UK and Chinatown, Singapore. Urban Morphol. 2020, 25, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Insights from Historical Institutionalism: The Institution and Evolution of Shanghai’s Urban Renewal. Urban Plan. Forum 2024, 04, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, D. Deciphering Built Form Complexity of Chinese Cities through Plot Recognition: A Case Study of Nanjing, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Tong, M. The Transformation of the Lilong Form: A Morphological Study on Changing Boundaries. Urban Des. Int. 2022, 29, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonesu, M. Learning from Each Other: Citizen Participatory Community Design in the United States and Japan, and the Role of the Architect; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brisudová, L.; Klapka, P. “It Should Be Treated in a Better Way”—Perceived Topovacancy in the Participative Urban Planning. Cities 2023, 141, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y. Towards a Sharing Architecture. Archit. J. 2017, 12, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bertacchini, E.; Frontuto, V. Economic Valuation of Industrial Heritage: A Choice Experiment on Shanghai Baosteel Industrial Site. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Time | Features | Cases Examined |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st: Tender, Auction, and Listing Policy | 2002–Present |

| Shanghai Xintiandi (pre-sharing economy) and WYSH4 (post-sharing economy) |

| 2nd: “Three No Change” Policy | 2008–Present |

| Jingyuan Fashion Creative Center (pre-sharing economy) and X Tower project (post-sharing economy) |

| 3rd: Rights-Holder-Led Policy | 2014–Present |

| First and second stages of SIOBP7 project (spanning pre-and post-sharing economy periods) |

| Cases | Policy Framework | Physical Boundary Change | Ownership Boundary Change | Activity Boundary Change | Street Frontage Index Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xintiandi | Land Tender, Auction and Listing | Partial transformation | Complete redefinition | Significant expansion | Moderate (commercial pathway) |

| WYSH | Significant expansion | Diversified | Significant expansion | High (2.5× increase) | |

| Jingyuan | Three No-change | Minimal change | Unchanged | Minimal change | Minimal (semi-closed system) |

| X Tower | Modified to face city | Unchanged | Extended toward community | Substantial (city square, waterfront) | |

| SIOBP Phase 1 | Rights-Holder-Led | Expansion | Unchanged | Expansion | Moderate (multiple entrances) |

| SIOBP Phase 2 | Complete transformation | Complete transformation | Complete transformation | High (permeable network) |

| Project Name | Retail Rent | Office Rent | Business Mode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xintiandi | 20–25 RMB/m2/Day | / | High-end business, consumer seating |

| WYSH | 7–7.5 RMB/m2/Day | Not disclosed to any third parties | Commercial integration of community-oriented offices, light dining mixed with trendy consumption, and provision of public spaces. |

| Jingyuan | / | 4–4.5 RMB/m2/Day | Decentralized leasing, park-style office |

| X Tower | 10–15 RMB/m2/Day | 4.5–7 RMB/m2/Day | Individual tenants combine community commerce, flexibly partitioning office spaces. |

| SIOBP I&II | 11 RMB/m2/Day | 7–9 RMB/m2/Day | Primarily commercial, with some multi-story sections for office space. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhu, Y. The Evolution of Plot Morphology and Design Strategies in Built Heritage Renewal in Central Shanghai from the Perspective of Sharing Cities. Land 2025, 14, 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050959

Li Z, Liu M, Zhu Y. The Evolution of Plot Morphology and Design Strategies in Built Heritage Renewal in Central Shanghai from the Perspective of Sharing Cities. Land. 2025; 14(5):959. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050959

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhenyu, Mengxun Liu, and Yichen Zhu. 2025. "The Evolution of Plot Morphology and Design Strategies in Built Heritage Renewal in Central Shanghai from the Perspective of Sharing Cities" Land 14, no. 5: 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050959

APA StyleLi, Z., Liu, M., & Zhu, Y. (2025). The Evolution of Plot Morphology and Design Strategies in Built Heritage Renewal in Central Shanghai from the Perspective of Sharing Cities. Land, 14(5), 959. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050959