Resisting Racism and Marginalization: Migrant Women’s Agency in Urban Transformation in Los Pajaritos Neighbourhood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context, Methods, and Tools

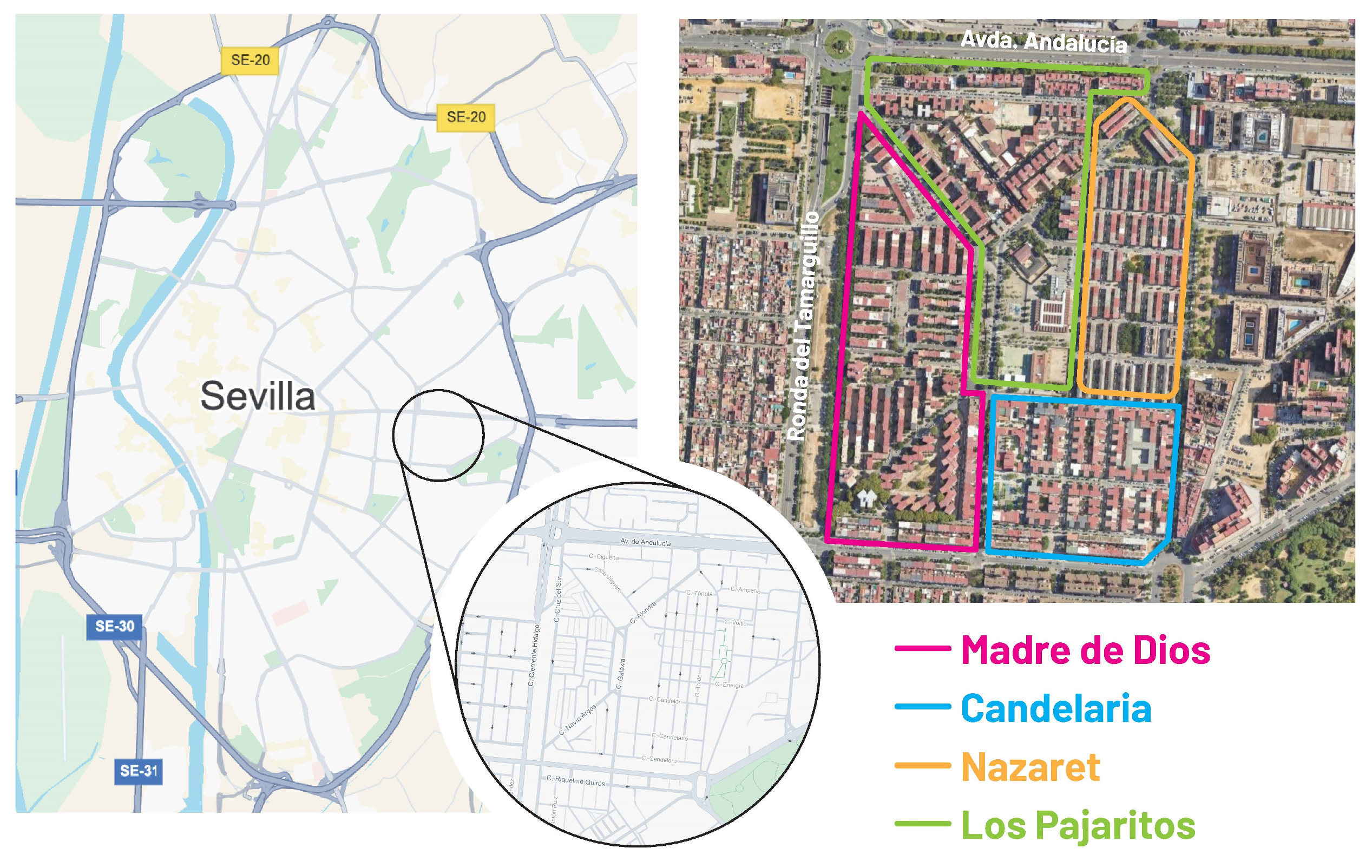

2.1. Case Study: The Neighbourhood of Los Pajaritos

2.2. Research Approach

2.3. Methodological Tools

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Territorial Reconfiguration in Transnational Migration

I started out by renting a room, because that was all I could manage at the time. And of course, I wasn’t alone there were at least six of us in the apartment. I paid 250 euros for that room. It was very basic, and we all had to share the kitchen and the bathroom. It wasn’t easy, but when you first arrive, you just adapt to whatever you find.Peony (28 January 2025 interview)

The little girl I left in Peru when she was one year and fifteen days old came here when she was seven, because I didn’t get my legal status until after six and a half years of being here, so then I brought her. And of course, today she is already thirty-three years old, time really flies, doesn’t it? She got married and moved to Edinburgh. My granddaughter was born there, in Edinburgh, Scotland. However, even though she was born there, she dances Peruvian folk dance as if she had been born in Peru.Daisy (16 October 2024 interview)

3.2. Labour Precariousness and the Role of Remittances in the Transnational Economy

I don’t even earn the minimum wage, and I can only go out every 15 days. I don’t get paid for holidays, vacations, nothing […] I can’t take this anymore. I’ve already gotten sick, I have severe sleep problems, and it’s because of the stress […] We are aware, we know our rights, but one swallow alone does not make a summer.Lavender (10 December 2024 interview)

That was one of the reasons I started organizing excursions. Even if it was just a round trip, people came back completely different, with a totally changed mindset. At first, I did it as a favour for friends, and then it turned into a business. It was a bus with fifty-five people, each with their own life, their own reason for going, but almost everyone shared the same need—to get out. Even if we left on Sunday morning and returned at night, at least they got to go out.Daisy (23 October 2024 interview)

On Saturdays and Sundays, I work, and I am supporting my mother and my siblings. I built a big house where the five of us live […] I also bought a very large car so that my father and mother can go for rides. In other words, these things they have because I work here […] But what rewards me after all these years, all this suffering, is that I gave my siblings an education. My sister has a degree in nursing, my brother is a doctor, and the other brother did a master’s in physical education and is working at a school. Look, they are very good students because they knew that I worked hard here.Rose (22 October 2024 interview)

3.3. Solidarity Strategies in Migratory Contexts

Look, in my house we are from three countries: Honduras, Colombia, and Nicaragua, and we get along well. Each one makes their own food, their own special dishes, and if one doesn’t have something, they give it to the other. I always try to help because one has been through so much… I am the kind of person who says: if I have a loaf of bread, I’ll split it in half and give it to that person, because I know what it’s like to be hungry […] So, it’s something we bring with us, values that your family teaches you, right? My mom always told me: never give from what’s left over, but from what you have. So, that’s how I am.Lily (26 November 2024 interview)

They have barbecues, and all the countries come together there, even the Spaniards or those who are married to Spanish people. We gather, eat grilled meat, play music, everyone is happy, and it’s all about coexistence. In Los Pajaritos, it happens a lot in the small square, on the stairs, which is very well known.Lily (5 December 2024 interview)

I’ve always liked everything that has to do with the social side of things, so that’s why I started volunteering at the parish, helping people and families in need. I organize events, activities for children, those kinds of things that fulfill me.Tulip (22 October 2024 interview)

3.4. Intercultural Encounters and Hybridization Processes

At the centre, you meet people from different places, whether South America or Central America. Through everyday things like food, you discover cultures you hadn’t encountered before. For example, I didn’t know what people from Paraguay ate. Here, I’ve felt welcomed. It’s like a second home, where you stop feeling like a stranger.Dahlia (13 December 2024 interview)

I am from the jungle, from the Peruvian Amazon, and I’m going to talk about a specific date that is celebrated in my land, which is June 24th, the Feast of San Juan. Every year at my house, I celebrate San Juan, with the typical food. I remember that once, when there was the Peru activity, I’m not sure if it was in 2010 or 2012, I made about 50 “Juanes” to take to the gathering we had. People didn’t even know what it was, but they liked it so much, thanks to that they got to know it. The food from the jungle is a kind of… it’s wrapped in a tamale, but it has rice, egg, and strawberry in it.Camellia (5 February 2025 interview)

There have also been many couples here. I mean, there are many Latinos married to Spaniards, and practically there is already that fusion. And the children born here are Spanish, but they don’t lose their culture. It’s important. We take care of everything. We are teaching the children, even though they were born here, not to lose their roots, the culture of their country, their parents’ roots.Sunflower (24 November 2024 interview)

3.5. Migrant Agency as a Driver of Social Change

A man insulted me on the bus: ‘Go back to your country.’ I said: ‘I’m already in my country. The land doesn’t belong to anyone, it belongs to everyone. What are you talking about?’ I’ve worked, I’ve paid social security, probably more than many Spanish people.Orchid (18 February 2025 interview)

And sometimes you tell your friends, “Don’t be silly, don’t let yourself be treated that way, look, act, act.” It’s not that they’re afraid to speak. Don’t be afraid to speak, it’s because you already feel brave, right? Because you know nothing will happen, that really nothing will happen, but many times they stay quiet because they say, “No, if I speak, I’m scared, and they’ll say at my job that I harmed myself.Daffodil (19 November 2024 interview)

I’ve been very active on social media lately because, as they say, I’m an influencer [Laughs]. I’m really not, but I give a lot of advice to the young women who come here, telling them that even if they don’t have papers, they should take courses, not shut themselves in at home, and see the world out there. Because when you’re at home, you have everything, food, a house, and when those things are gone, or they kick you out, or the lady passes away, or whatever happens, you face a reality where there is no work, and if you don’t have any courses, they won’t take you… I really like doing that, and on social media, I do TikTok. I have friends from Mexico, Guatemala, and they follow me.Rose (5 November 2024 interview)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Boeck, F. Death and the city. Necrological notes from Kinshasa. In Global Urbanism: Knowledge, Power and the City; Lancione, M., McFarlane, C., Eds.; Routledge: Lundon, UK, 2021; pp. 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Ciudades Rebeldes. Del Derecho De La Ciudad a La Revolución Urbana; Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Simone, A. Cities of the Global South. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2020, 46, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quillian, L. Segregation and poverty concentration: The role of three segregations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 77, 354–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuse, P.; Van Kempen, R. (Eds.) Globalizing Cities: A New Spatial Order; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy; Belknap Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. Planet of Slums; Verso Books: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso Books: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, A.D.; Mair, C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Montero, R.; Sianes, A. Relatar la vida para resignificar el territorio. La reconstrucción histórica del barrio Guadalquivir. Rev. EURE-Rev. Estud. Urbano Reg. 2024, 50, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyero, J.; Bourgois, P.; Scheper-Hughes, N. (Eds.) Violence at the Urban Margins; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arango, J. Después del gran boom: La inmigración en la bisagra del cambio. In La Inmigración En Tiempos De Crisis: Anuario De La Inmigración En España; Aja, E., Arango, J., Oliver, J., Eds.; Fundación CIDOB: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Held, D.; McGrew, A.; Goldblatt, D.; Perraton, J. Transformaciones Globales: Política, Economía y Cultura; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; p. 648. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, C. Globalización, género y migraciones. Polis Rev. Latinoam. 2008, 7, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eseverri Mayer, C. La vida en los suburbios: Experiencia de los jóvenes de origen inmigrante en un barrio desfavorecido. In La Hora De La Integración; Aja, E., Arango, J., Oliver, J., Eds.; Fundación CIDOB: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; pp. 286–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lora-Tamayo D’OCón, G. Inmigración Extranjera en la Comunidad de Madrid. Informe 2006–2007; Delegación Diocesana de Migraciones (ASTI): Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pessar, P.; Mahler, S. Gender and transnational migration. In Transnational Migration: Comparative Perspectives; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Tovar, C.A. Materialización del derecho a la ciudad. Bitácora Urbano-Territ. 2020, 30, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The Communist Manifesto: New Introduction; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rogaly, B.; Qureshi, K. Diversity, urban space and the right to the provincial city. Identities 2013, 20, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Neira, Y. Teoría Transnacional: Revisitando la Comunidad de los Antropólogos. Política Y Cultura 2005, 23, 181–194. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-77422005000100011 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Purkis, S. Invisible borders of the city for the migrant women from Turkey: Gendered use of urban space and place making in Cinisello/Milan. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2019, 20, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duany, J. Reconstructing racial identity. Lat. Am. Perspect. 1998, 25, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonhomme, M. Racismo en barrios multiculturales en Chile: Precariedad habitacional y convivencia en contexto migratorio. Bitácora Urbano-Territ. 2021, 31, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barañano, M.; Marchetti, S. Perspectivas sobre género, migraciones transnacionales y trabajo: Rearticulaciones del trabajo de reproducción social y de cuidados en la Europa del Sur. Investig. Feministas. 2016, 27, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrusán Murillo, I. Servicio doméstico y actividad de cuidados en el hogar: La encrucijada desde lo privado y lo público. Lex. Social Rev. Derechos Soc. 2019, 9, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Guzmán, H.; Smith, R.; Grosfoguel, R. (Eds.) Migration, Transnationalization, and Race in a Changing New York; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001; pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar Parrenas, R. Transgressing the nation-state: The partial citizenship and ‘Imagined (Global) Community’ of migrant Filipina domestic workers. Signs 2001, 26, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D.S.; Denton, N.A. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Hernández, P.A.; Alcaide Lozano, V. Mujeres inmigrantes latinoamericanas: Procesos de agencia en contextos de vulnerabilidad. Papers Rev. Sociol. 2021, 106, 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdal, M.B. Theorizing interactions of migrant transnationalism and integration through a multiscalar approach. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2020, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvey, R. Geographies of gender and migration: Spatializing social difference. Int. Migr. Rev. 2006, 40, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, S.; Miller, M.J. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, P.; Glick-Schiller, N. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004, 38, 1002–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteros Obelar, A. Acción política y mujeres migrantes: Desafíos y oportunidades en contextos de exclusión. Estud. Soc. Latinoam 2017, 18, 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, H. La Condición Humana, 2nd ed.; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, S. Feminist theory, embodiment, and the docile agent: Some reflections on the Egyptian Islamic revival. Cult. Anthropol. 2001, 16, 202–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, España. Indicadores Urbanos. 2024. Available online: https://datos.gob.es/es/catalogo?tags_es=Indicadores+Urbanos (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Ayuntamiento de Sevilla. Diagnóstico de Zonas con Necesidades de Transformación Social. 2016. Available online: https://www.sevilla.org/servicios/servicios-sociales/publicaciones/diagnostico-zonas-necesidades-transformacion-social.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- García Márquez, J.M.; Martínez López, F. Arquitectura y vivienda en la periferia de Sevilla durante el franquismo: Los grupos de promoción oficial. Boletín Del Inst. Andal. Del Patrimonio Histórico 2015, 84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Observatorio de Desigualdad de Andalucía. V Informe del Observatorio de Desigualdad de Andalucía. 2023. Available online: https://observatoriodesigualdadandalucia.org/recursos/v-informe-del-observatorio-desigualdad-andalucia-2023 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Maya-Jariego, I.; González-Tinoco, E.; Muñoz-Alvis, A. Frecuentar lugares de barrios colindantes incide en el sentido psicológico de comunidad: Estudio de caso en la ciudad de Sevilla (España). Apunt. Psicol. 2023, 41, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A. Rethinking scale as a geographical category: From analysis to practice. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 32, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B. Multi-scalar ethnography: An approach for critical engagement with migration and social change. Ethnography 2013, 14, 282–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlar, A.; Glick Schiller, N. A multiscalar perspective on cities and migration. A Comment on the Symposium. Sociologica 2015, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Basic and Advanced Focus Groups; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R.S. Doing Focus Groups, 2nd ed; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarotti, F. Las historias de vida como método. Converg. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2007, 14, 15–40. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2968599 (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- López-Montero, R.; García-Navarro, C.; Delgado-Baena, A.; Vela-Jiménez, R.; Sianes, A. Life stories: Unraveling the academic configuration of a multifaceted and multidisciplinary field of knowledge. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 960666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, T.A. Discourse and Knowledge: A Sociocognitive Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, T. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Faist, T. Transnationalization in international migration: Implications for the study of citizenship and culture. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2000, 23, 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hondagneu-Sotelo, P. Doméstica: Immigrant Workers Cleaning and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barrial, C. La Trinchera Doméstica: Historias Del Trabajo En El Hogar; Levanta Fuego: Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Liu, C.Y. Migrant entrepreneurship, social networks, and economic resilience: Evidence from urban areas. J. Urban. Econ. 2019, 111, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malerba, F.; Ferreira, C. Transnational entrepreneurship: The role of networks and innovation in migrant business success. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diner, H. Erin’s Daughters in America: Irish Immigrant Women in the Nineteenth Century; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. Globalization from Below: The rise of Transnational Communities; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. Global cities and diasporic networks: Microsites in global civil society. In Global Civil Society 2002; Anheier, H., Glasius, M., Kaldor, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, P. Transnational migration: Taking stock and future directions. Glob. Netw. 2001, 1, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, F.; Rishbeth, C. Conviviality by design: The socio-spatial qualities of spaces of intercultural urban encounters. Urban. Des. Int. 2020, 25, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.; Iveson, K.; Leitner, H.; Preston, V. Planning in the multicultural city: Celebrating diversity or reinforcing difference? Prog. Plann. 2014, 92, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Ortiz, M.L. Identidad cultural y territorio: Una reflexión en torno a las comunidades trasnacionales entre México y Estados Unidos. Región Y Soc. 1998, 9, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosaldo, R. Reimaginando las comunidades nacionales. In Decadencia Y Auge De Las Identidades. Cultura Nacional, Identidad Cultural Y Modernización; Valenzuela, M., Ed.; El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Programa Cultural de las Fronteras: Tijuana, Mexico, 1992; pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogía del Oprimido; Siglo XXI: Yucatán, Mexico, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre Vidal, P. Las redes de apoyo entre mujeres y su papel en el proceso migratorio. Enseñanza E Investig. En Psicol. 2024, 6, 193–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, A.; Boix, M. Los géneros de la red: Los ciberfeminismos. In The Role of Humanity in the Information Age. A Latin Perspective; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2002; pp. 25–45. [Google Scholar]

| Participants * | Country of Origin | Age | Years in the Destination Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rose | Ecuador | 55 | 26 |

| Lily | Nicaragua | 43 | 19 |

| Daffodil | Colombia | 57 | 7 |

| Giselle | Colombia | 58 | 2 |

| Tulip | Colombia | 45 | 2 |

| Orchid | Morocco | 37 | 16 |

| Sunflower | Peru | 61 | 34 |

| Peony | Nicaragua | 36 | 6 |

| Lavender | Nicaragua | 43 | 3 |

| Daisy | Peru | 54 | 32 |

| Camellia | Peru | 55 | 16 |

| Territory and Mobility | Economy | Networks and Communication | Interculturality | Agency and Transformation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-spatial Production | Labour Precariousness in the Care Sector | Solidarity and Resistance Networks | Intercultural Processes | Processes of Collective Awareness |

| Territorial Reconfiguration | Entrepreneurship and Subsistence Strategies | Participation and Collective Organization | Persistence and Transformation of Cultural Practices | Agents of Change and Social Justice |

| Remittances and Transnational Livelihood | Mestizaje and New Social Imaginaries | New Technologies and Migrant Agency |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Montero, R.; Sianes, A. Resisting Racism and Marginalization: Migrant Women’s Agency in Urban Transformation in Los Pajaritos Neighbourhood. Land 2025, 14, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050950

López-Montero R, Sianes A. Resisting Racism and Marginalization: Migrant Women’s Agency in Urban Transformation in Los Pajaritos Neighbourhood. Land. 2025; 14(5):950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050950

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Montero, Rocío, and Antonio Sianes. 2025. "Resisting Racism and Marginalization: Migrant Women’s Agency in Urban Transformation in Los Pajaritos Neighbourhood" Land 14, no. 5: 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050950

APA StyleLópez-Montero, R., & Sianes, A. (2025). Resisting Racism and Marginalization: Migrant Women’s Agency in Urban Transformation in Los Pajaritos Neighbourhood. Land, 14(5), 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14050950