Abstract

For decades, in historical research, archeological vestiges have been linked with geomancy and cults of the mythical ancestors of a group of the population. This is particularly true in Eastern Asia and especially in China, Korea, and Japan. A fundamental problem of Japanese archeology is that few of the remnants were realized in stone. One of the most important parts of archeological sciences is the study of Necropolises or ancient interments. From the 1970s onwards, in the relatively “new” and promising land of Hokkaido, cemeteries were built with the concept of landscape in mind; this is also due to the lavish vegetation features of this northernmost island of Japan. In the case of the Takino cemetery on the plains of Sapporo, Hokkaido, whose construction began in 1982, solemnity and religiousness were incorporated by producing exact stone replicas of famous funerary landmarks from antiquity as such materials were inexistent in the Nipponese Isles. This trend to grant eternity included traditional Buddhist funereal monuments like the Stupa, Seokguram grotto, and Kamakura sites, but at a certain and exuberant point, under the influence of Isamu Noguchi, it reached Stonehenge in England and the Moai from Easter Island in Polynesia (being after all located in a remote isle of the Pacific Ocean). In this article we will outline such process of generation and overall conception, analyzing the inclusion and architectural assembly of the different compounds and the recent and extraordinary additions projected and built by the celebrity architect Tadao Ando. We expect, in this manner, to facilitate the comprehension of the significance of venerable landscape sublimated through archeology for the Nipponese modern civilization.

1. Introduction: The Fascination of an Unknown Island

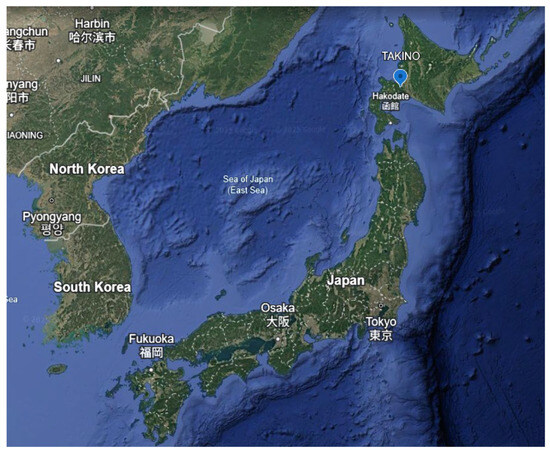

For a variety of reasons, the Japanese archipelago cannot be considered an utterly ancient hinterland [1]. Even from a geological point of view, its variegated igneous nature, still active, seems to eschew extreme antiquity [2,3]. The northernmost of the four large islands, Hokkaido 北海道, passes as even newer from an anthropological point of view [4], as it was only inhabited by aboriginals called Ainu (i.e., people) [5], who remained anchored on the verge of the Bronze Age, until well beyond the 19th century (Figure 1). The main foundational texts of the Japanese civilization, like the Kojiki [6], 古事記, strive to convey the grandiosity attributed to immemorial times. Nevertheless, the anvil of history, by virtue of Chinese sources, endorsed with recent genetic analyses, has revealed that the now prevailing Yamato people only harks back from the 3rd century C.E. at the most [7,8]. The Ainu aboriginals or their ancestors termed Emishi 蝦夷, commonly a synonym of barbarian, suggest a much older pre-existence on these isles, a fact often disregarded or diminished by partisan historians [9].

Figure 1.

Map of Japan with Takino near Sapporo in Hokkaido.

It is generally accepted that the tumulus or ceremonial mound is the preferred construction on the land or soil erected by many civilizations [10], and particularly by the peoples of East Asia, with the paramount examples of Korean geomantic tumuli and Japanese Kofun 古墳. These generally consist of a set of tombs of ancient rulers in which the terracotta statuettes, named haniwa 埴輪, were deposited [11,12]. The kofun echoed Indian stupa, although it is not a tomb and later gave way to the stupa’s rebirth in variegated forms such as the Tahoto 多宝塔 or the hall of many treasures [13]. Such artificial hills were completely absent from Hokkaido’s landscape as the Ainu had other forms of religious worship more centred on living nature and not related to man-made constructions. Moreover, Japanese archeology faces the important issue that, as construction in stone was rare, very few remnants can be spotted by traditional excavation techniques. Therefore, for designers of ceremonial spaces at all epochs, it was imperative to imbue a sense of antiquity and, moreover, of eternity to the places where the ancestors and the deceased were revered, by performing volumetric alterations to the land [13,14], as we can read in Horace’s Ode 3.30 [15].

Consider in a parallel with Christendom, the verses of 1808 by William Blake: “And did de Countenance Divine/Shine forth upon our clouded hills?/And was Jerusalem builded here/Among these dark Satanic Mills” [16]. These outlandish lines certainly evoke the concept by virtue of which, even on the heathen lands of England, the erection of a sacred monument, particularly a funereal one, seems to have demanded a hallowed although natural precinct much in the image of the seven hills of Rome or other orographic formations [17].

Only ten years later, in 1818, Percy Shelley wrote about the huge statues of Ramses II at Abu Simbel: “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:/Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”/No thing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away [18,19].

Thus, clearly confirming the inspirational power of archeological vestiges on human memory and behaviour as an invariant for the erection of sacred sites and hierothesions [20].

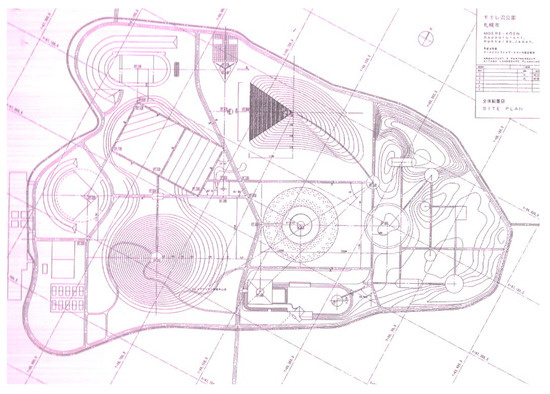

In the case of the Sapporo area, the first precedent, which inaugurated this trend for Japanese architectural design, seems to appear in the Moerenuma Park (Figure 2) in the northern zone of the city and more specifically the scenic work known as Play Mountain [21].

Figure 2.

General plan of the Moerenuma Park designed by Isamu Noguchi.

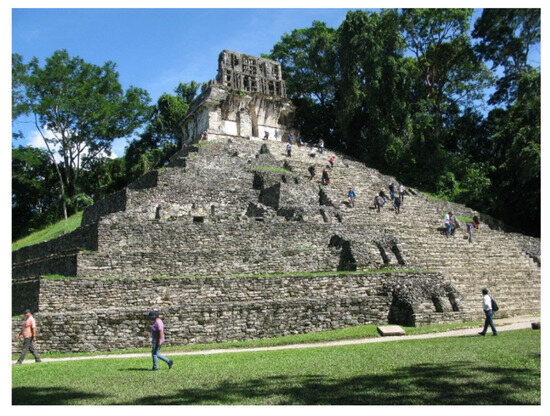

In it, the Japanese-American sculptor and landscape artist Isamu Noguchi takes advantage of the verdant features of Hokkaido to recreate the striking imagery of Maya-like pyramids, as Kukulkan at Chichen Itza or Palenque [21,22] (Figure 3). We need to bear in mind that Noguchi lived for some time in Mexico where the precedent of pre-Hispanic cultures, brought to him by artist acquaintances among which ranks Frida Kahlo, exerted an indubitable attraction if not a pervasive influence [23]. At the so-called Play Mountain, by means of bare stripes of stone superposed on the sloped turf, he creates the vision that the full potency of an ancient pyramid lies covered under thick vegetation (Figure 4), to the point that the visitors, which can occasionally be seen on its summit, play the role of acting as king-priests of a forsaken temple [24] (Figure 5).

Figure 3.

The pyramid of Palenque. Mexico. Source: author.

Figure 4.

Play Mountain at Moerenuma by Isamu Noguchi. Source: Author.

Figure 5.

Detail of the play Mountain with stripes resembling ancient stones. Source: Author.

From an ecological point of view, such pervasive creation is only natural if we realize that, as previously mentioned, grass is more abundant in Japan [25] than stone ashlars are.

To prove the previous statement, let us quote a famous haiku by Basho on the lost capital of Hiraizumi: The Summer grass leaves/Ruins of the Dream/of the Warriors of Old (Trans. by author). 夏草や兵どもが夢の跡. It denotes that the only remnants of a once proud capital are the ephemeral leaves of the summer.

In compounds like the Karesansui 枯山水 (stone miniature landscape) or at Katsura detached palace, ashlars are considered almost as venerable relics [20,21]. The dictum of the artist Joseph Beuys comes instantly to our minds at this point: “It is to us only, to imbue life to the stones so that they do not lie around, scattered as carcasses.” [26].

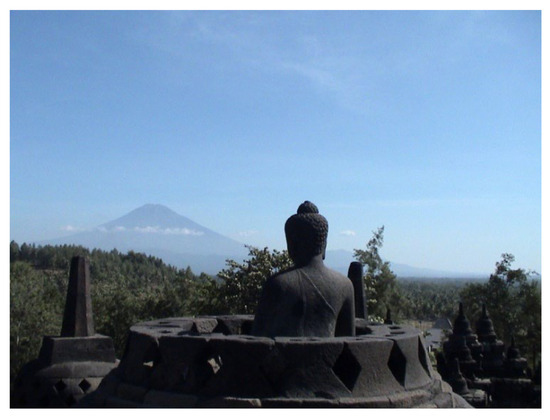

After a fashion, this square mound echoes a distant pyramidal landmark of south Java, the celebrated Temple of Borobudur near Yogyakarta (Indonesia) [27] to which we will refer later on (Figure 6). Comparatively, there are fewer stone monuments on the southern hemisphere than on the northern one, perhaps due to a sparser distribution of the land masses.

Figure 6.

View of the Borobudur Temple in JYogyakarta.

All in all considered, by acting in this seductive manner, Noguchi is able to incorporate important aspects of the aesthetics of Shintoism by revering nature as something supernatural and, at the same time, to beckon the essence of Zen Buddhism that pervades Nipponese idiosyncrasy [28], signalling the misty way of the occult and letting human imagination perform the task of accomplishing what cannot be entirely revealed or uttered [29].

Previously, he had pronounced a direct reflection onto Buddhist liturgy in his celebrated piece “Black Slide Mantra”, a kind of helical toboggan for children cum carven steps. The playground, sculpted in polished sable stone [30], is located at Odori Park in central Sapporo (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Black slide mantra. Odori Park. Sapporo.

These references are clearly supplying the Japanese fields and cities with stone monuments of an imaginary archeology stemming from a culture that, in a sense, never was. However, it could have been this way if the crucible of History would have forged the events otherwise. Slowly but surely these new forms are enriching their idealized past for the future generations and so the creations have received wide acclaim everywhere [27].

It was chiefly thorugh such powerful design examples in mind and with an eye on Buddhist rites, that the planning of the Takino funereal park was to take a start in the 1980s.

2. Materials and Methods

In the first place we need to remind that Takino is not just a cemetery tucked in the outskirts of a town in the sense of Europe or the US, but rather and as the name Rei-en 霊園 suggests, a place of pilgrimage, in which we ascend to a veritable “Sanctuary of Souls”. The departed are not merely buried and swiftly forgotten, instead they are comforted, accompanied, and ever-present in the pristine manner inherent to the Japanese ideas of afterlife and netherworld [31].

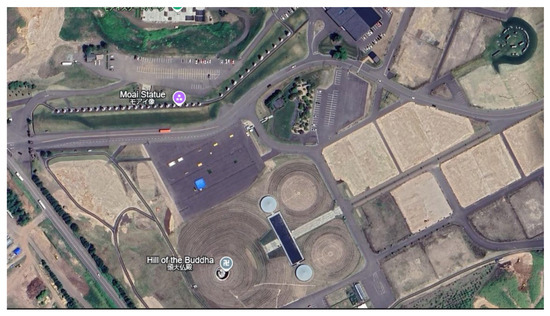

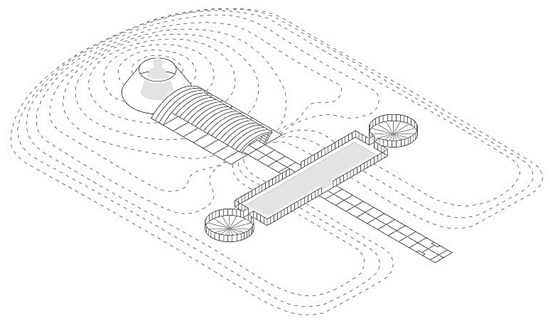

That said, in the general plan and from an architectural perspective, we can distinguish three main compounds around which the whole landscape sequence orbits (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

General plan of the Takino Cemetery.

Relating to the sculpture of Buddha, the Stonehenge circle, and the Moai alignment, the methodology will consist of a thorough and systematic analysis of the origin, implications, and interplay of these three elements in order to improve the archeological complex and be able to assess the new realizations that have taken place at Takino, especially since 2017.

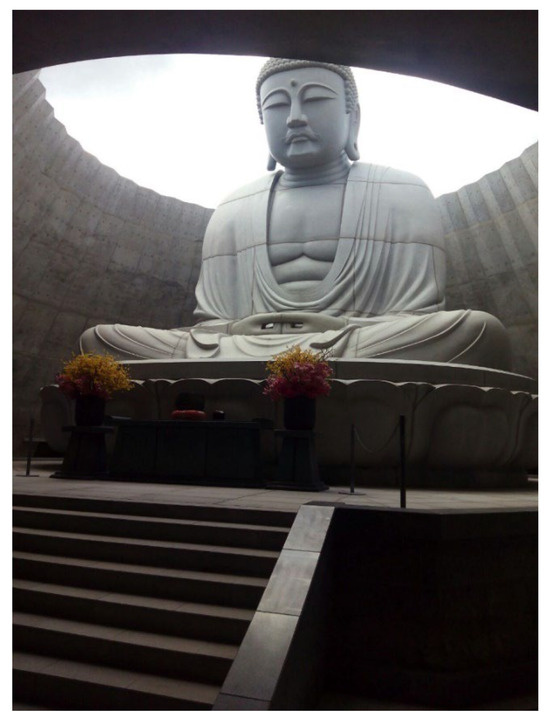

2.1. The Giant Buddha Statue

As explained previously, the Daibutsu is situated in the first place. This Buddha modelled after the Kamakura statue, is completely central to the precinct of the cemetery (Figure 9), secluded by a hill, and from 2017 onwards it is preceded by a sizeable rectangular pond (in black in Figure 8) that impedes direct entrance trough the passageway and towards the massive sculpture weighting 1.500 tons and rising to a height of 13.5 m [29].

Figure 9.

The Daibutsu statue at the Takino cemetery in its original configuration.

The imposing figure is flanked by two symmetrical mounds, which, in this way, define an important avenue leading directly to the giant statue. We must hereby stress that the sculpture is not directly perceptible from the entrance gates to the funereal park.

We need to outline that, in Japan, traditionally the Buddha image is not exposed to the outside but rather accommodated in a grand temple of timber frame as in Todai-ji at Nara. The only exception is the Kamakara Daibutsu and this is likely due to the arson that once occurred in the hosting precinct; it was of such magnitude that the high priests of the time decided to leave the bronze statue alone without reconstructing the precedent temple [32].

In addition, stone is not the preferred material for statures of the Buddha; instead we find mostly wood or gilded bronze in some special cases. This fact builds on the scarcity of permanent remnants in Japanese archeology as already stated. In the case of Takino, to settle these problems of conservation, it was planned that the sculpture would be composed of resistant granite stone and after careful polishing, left open to the visitors among the gentle slopes of the selected area of 800 hectares (See Figure 9, above). To house it in a modern construction would have been inviable.

However, soon enough, the towering image exerted an equal spiritual burden on the believers and by-passers. The stone Buddha was considered too solemn, imposing or even melancholic. The gloomy and cold weather of this area might have played a role for such ominous perception [33].

In this respect, we can find an important transitional case of an adumbrated but not actually visible Buddha at the Byodoin (Temple of Peace) of the town called Uji. The whole precinct is an example of Amitabha Buddhism in which the pilgrimage destination to be reached was the paradise of the West. The travellers were forced to accede to the complex by the river Uji and not by the current entrance from the narrow winding streets inside the town. It is remarkable that the name Uji in Japanese 宇治 means the Kingdom of Heaven or the Heavenly Paradise [32].

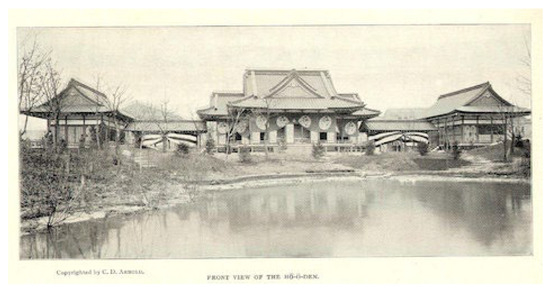

The central hall is called Hôôden 鳳凰殿, the Palace of the Emperor Phoenix. It is in fact crowned by two symmetric phoenixes, which, when nested over a temple, auspicated the flow of spiritual and material perfection for the entire realm. Their mere presence suggested a breeze of harmonious sounds echoed by the peculiar wind instrument called Shô. The Hôôden was considered an emblem of Japan to the point of being reproduced life-size as a Japanese Pavilion for the Chicago World-Fair of 1893 (Figure 10). The person in charge of that pavilion was the celebrated artist and writer Okakura Kakuzo, the author of The Book of Tea, written solely in English in 1906 [33].

Figure 10.

A postcard showing the front of Hôôden in Chicago (no longer extant).

The relevant feature of this temple for the case of Takino is that the lattice work and oval opening of the main gates allowed to contemplate from the outside the countenance of the Buddha without need to penetrate inside the temple (Figure 11 and Figure 12). These elaborate process of visualization of a deity or religious image is called darshan in Sanskrit दर्शन.

Figure 11.

View of the lattice of the Main Gates at the Hôôden in Uji.

Figure 12.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the main hall of the Buddha with the elliptic opening to see the Holy Visage without entering the precinct. Uji.

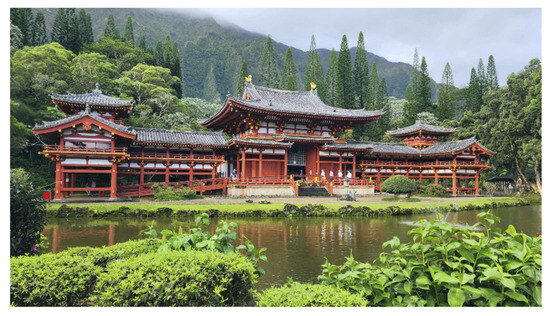

The Byôdôin scenography and iconography are so meaningful that they have been reconstructed in places far away from Japan as in Oahu, Hawaii (US). In this careful reproduction, the access and view from a body of water are duly respected; it was dedicated in 1968 in memory of the Japanese Immigration (Figure 13) [34]. Besides the Buddha, historic characters like George Washington are revered in the surroundings under the category of kami (deity).

Figure 13.

The Byôdôin at Oahu, Hawaii. Valley of the Temples.

For esoteric theology matters, the hidden Buddha or Hibutsu 秘仏 is an invariant of East Asian religions. Since the historical Buddha Shakyamuni ascended to Heavens after entering paranirvana 涅槃 (nehan in Japanese), it cannot be manifest or appear frequently in the earthen world. Those who could possibly be summoned are the bosatsu, impersonations of the Buddha who voluntarily elected to remain in this world in order to help human beings attain nirvana in their turn [35]. For that reason, it is rare in Japan to find a statue of the Buddha exposed to the outdoors and some of the images in the temples can be regarded only on special occasions, every fifty or even one hundred years. Even the shadow of the Buddha is considered a good omen and this belief has been incorporated into a common expression of everyday Japanese language [36].

A somewhat extreme case of the former attitude is to be found at the previously referred temple of Borobudur in the outskirts of Yogyakarta Indonesia [20]; in the third level of the pyramid we would find a retinue of curious bell-shaped stupas, providing some spiritual ring to believers (Figure 6 and Figure 14). The stupas, the first Buddhist monuments, are hollow in this case, and just through rhomboid apertures we can surmise a finely carved Buddha statue kept within. It is somewhat astounding that the original builders had to take such effort to create the sculptures (Figure 15) only to subtract them later from open view as they are perpetually put to rest behind heavy stone blocks.

Figure 14.

The bell-shaped stupas on the third level of Borobudur.

Figure 15.

A damaged stupa reveals the hidden Buddha, which could only be descried from the loopholes of the stone envelope. Candi Borobudur. Yogyakarta. Source: author.

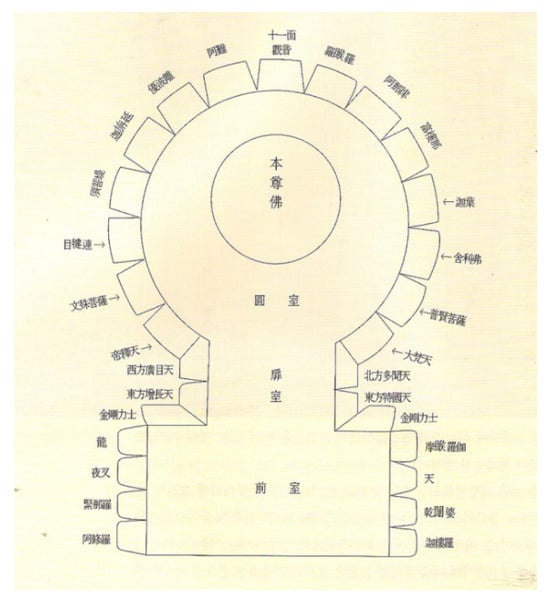

A less remote example of a covered Buddha is located at Gyeongju in Korea. The hill of Seokguram where it was erected, has been a consistent source of attraction for the local people and foreign travellers as well. The seemingly nondescript artificial cave indicated a novel concept of space [37] for Asia that was subsequently forsaken for centuries, until incidentally rediscovered by the Japanese, because it was mainly built in stone and since then is experiencing a revival to the point of having been declared as a World Heritage site (Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18).

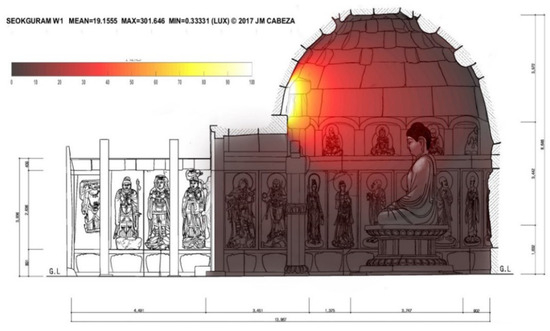

Figure 16.

Plan of Seokguram showing (in Chinese characters) the many different guardians and protective figures (four kings and arahats) that surround the Buddha in carved reliefs.

Figure 17.

Sectional view of the grotto including simulation of lighting levels by a circular opening no longer extant.

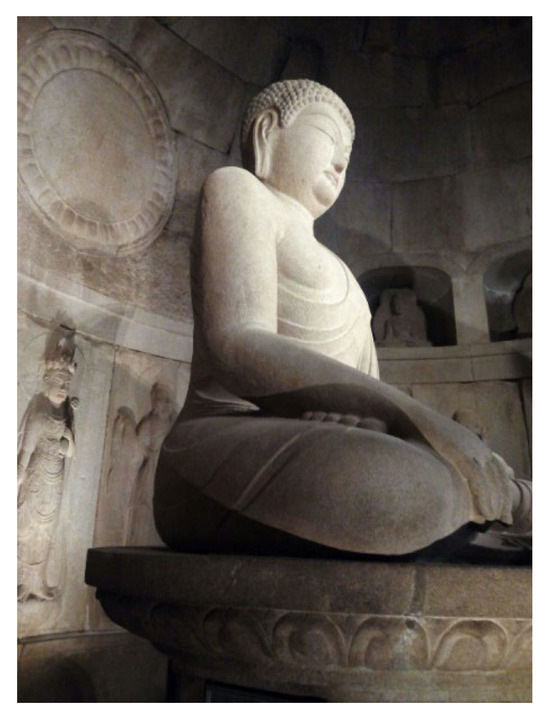

Figure 18.

A view of inner harmony at the adytum of Seokguram.

Its main features are as described in the manuscript of Ko Yusoep [34]:

This great statue, beginning as a bloodless, passionless lump of granite, has been endowed with a strong pulse, breath, divinity, gentleness and dignity. When unveiled, the joy was surely not limited to the sculptor, but extended throughout Silla and echoed towards the cosmos

And in the book of Joon-Sik Choi [34] we can read these impressions:

You cannot help but wonder how on earth it was possible to carve such a soft and flowing appearance out of granite, a rock that is so hard that it is considered the most difficult stone to sculpt… Isn’t it enough for the best works of art simply to exist?

The Seokguram enclave links with a cherished Buddhist tradition of hypogeal compounds [35,36] that goes back in time to thousands of years and originated mainly in India [17] in coenobiums known as chaitya. The climate of the Indian plateau and the geologic characteristics of its soil favoured the introduction of this peculiar system of construction [8] intended for religious or spiritual communities.

The tumuli that formed the stupa, as we said, the original Buddhist monument [15], subtly evolved to house inner space. It began by nominal diggings on the surface of the rock cliffs to serve as mere storage and shelter, until gradually becoming sumptuous hypogeal temples devoted to the Buddha and its grand ceremonies. The main reasons for such a procedure were both climatic and spiritual: the imperious necessity of building a covered space to conduct religious ceremonies or to offer prayers when the storms of monsoon weather prevented holy mission or any kind of outdoor activities for monks and disciples alike [7]. Such spaces also reduced the probabilities of incidental stamping or crashing onto swarms of insects that thrived in the damp of the stormy season. In the same manner, in Korea, the Seokguram cave, a celebrated Buddhist precinct (Figure 17), emerged from the antecedent of ritual tumuli [9].

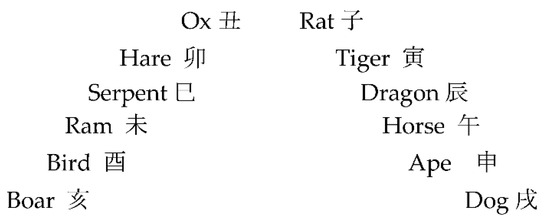

Being a form of revolution, the tumulus or the stupa beckon a cosmic order that is revealed and displayed through its external features, aspects that were taken as a prototype in Japan, Korea, and China [15,16]. The tumuli had at the beginning a Daoist essence as we will see, that was slowly adopted and incorporated in Buddhism. The same happened in Japanese temples with Shintoism. Domes consisting of masses of stones have been used in Korea since ancient times to create a sort of ceremonial mound. Often, they are covered with vegetation, mosses, and grass. The first tumuli had no inner space, but they implied a geomantic meaning as a sort of altars that required to be encircled for rituals [9]. At a later stage, such Feng Shui of the land was made explicit by the designated sequence of images of the twelve astral beings which compose the Eastern Zodiac. These entities regulated the seasons and also the time within the day (Figure 19 and Figure 20).

Figure 19.

Tumulus of Hwangnam-ri. Gyeongju (Korea).

Figure 20.

The cosmological group disposition of the twelve animals found at diverse tumuli in Korea. The hour of the rodent coincides with midnight (north), and the hour of the horse stands for midday (southwards). The order segues from right to left and top to bottom in each inclined column, the duration of each hour was deemed 120 min, double of the current modern hour. The special Chinese characters for every entity are given.

The said astral creatures, provided with common animal heads on a human-like torso, appeared on the base of the tumuli at regular intervals from the solar directions [9], starting with the horse 午 (Wu in Chinese), which roughly translates as Meridian or Noon. This astral horse is aligned with due south as it signals midday (Figure 20). The normal sequence of the beings, clarified by the authors is Rodent (24 h), Ox (2 h), Tiger (4 h), Hare (6 h), Dragon (8 h) Serpent (10 h), Horse (12 h), Ram (14 h), Ape (16 h), Bird (18 h), Dog (20 h), and Boar (22 h). It is interesting to remark that unlike Japan or China, in Korea, the entrance to the tumuli has a deviation of five to ten degrees from the solar south–north axis.

In Japan, the twelve beings are frequently presided by four major entities, which include the dusk war of turtle and serpent to the north, the turquoise dragon to the east, the vermillion phoenix to the south, and the white tiger facing west. Mostly, the four Guardian Kings as they are called, appear on the inside of the tumulus or statue concerned, and, sometimes, they are formed outside of the building as in the famous temple of Shitenno-ji in Osaka [38].

We have delved on the tumuli since the first known large-scale Buddhist monument was the stupa स्तूप, and especially the Stupa of Sanchi (India), which is basically a mound with some relics inside it but never a tomb. Images of the Buddha were rare 2400 years ago and not technically feasible, as the first ones were made around 250 B.C. by Indo-Bactrian sculptors descending from Alexander’s lasting Hellenistic influence on the area.

The tumulus is connected with the stupa in some subtle ways, particularly in Korea, where the mounds evolved to the point of being hollowed (remarkably without any knowledge of vaulting techniques) and harbour a sizeable statue, which was a constant source of inspiration not only in this country but in Japan, as it was discovered by Nipponese engineers. In this manner, the Seokguram Buddha is entirely covered but it is still visible from the outside through a glass panel (we cannot know about the view in the past).

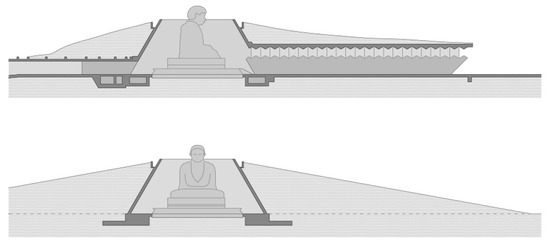

In the case of Takino, the Buddha statue was at first conceived to stay in the outside, but since this was resented by the public, there was a decision to cover it partially, leaving only the head perceptible as in other temples of Japan and especially the Byodoin (Figure 10 and Figure 11). This was particularly the project decision recognized by the team of the architect Tadao Ando, because the idea of holding the Buddha inside of some sort of makeshift modern building was rapidly discarded as unfeasible and impractical. In addition, it was still desirable to maintain a panoramic vision of such elaborate and magnificent statue, and it was spiritually necessary that the Buddha could grant a direct and unfiltered blessing over the land of the pilgrims that the hallowed presence encompassed.

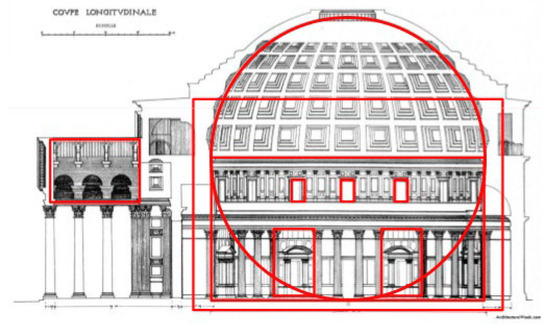

The method of partial concealment of the statue had to be one fundamentally based on the creation of sustainable landmasses, resembling nature in all aspects, as is the truncated volcano (another famous symbol). The tumulus or forested mound comes then as a natural solution since it was also used for the entombments of ancient emperors of Japan in the historic period known as Kofun Jidai (Era of the Mounds). A conventional building with a façade, windows, pediments, or roofs, would not have served the purpose (being abhorrent among other things), and certainly could not rival with the Stonehenge circle of fathomless antiquity. In fact, both elements evoke proto-historical moments of history related to caves and megaliths, but to become an actual shrine an obscure cave is not enough; it must the sublimated by the light much in the same way as the Roman Pantheon does [39]. Such is both the wish and abstract style of architect Tadao Ando. The former discussion explains why the Takino Buddha cannot be just covered, it can only be framed or better “preserved”.

Regarding the reaction of the authorities and the public, it has been thoroughly positive, because Japan is typically defined as a culture of shadows [40] where ambiguity and relativity are always preferred to stark contrast or straightforward expression. An illustrating example is the fact that the western method of chiaroschuro is substituted in Japanese art by “notan”, literally “thick and thin” lines [41]. So far, we have described the historic evolution of design intentions for the section of the Buddha statue at Takino. Surprisingly, this superb sculpture was completed with the alignments of Stonehenge and similarly at the main side of the complex by a lengthy retinue of 42 Moai statues similar to those erected on Easter Island. Let us present both archeological milestones in the following chapters.

2.2. The Stonehenge Ring

Although much older in historical apparition, henges can compare to the tumuli described beforehand in the sense that they are both megalithic rings that suggest rituals of circumambulation usually following the solar cycles and cosmic rituals.

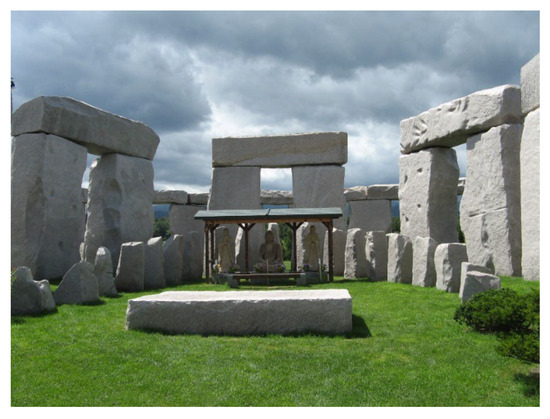

It might seem contradictory to display a reproduction of an ancient British stone circle in the design of the park, in coexistence with the Great Buddha; the reasons for that are variegated (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

Stonehenge in Salisbury, England.

The mere existence of different replicas of Stonehenge can be understood under the mind frame of the megalithic structure as a universal symbol of pre-historic monumental attitude in Europe [42]. We need to remind also that these kinds of megaliths often linked to Celtic culture marked the Western edge or Finis Terrae of the ancient world (in Britanny, England, and Ireland). Their Maltese counterparts marked the Southern Edge in turn. The fact that we can find many references to Stonehenge in both pop culture and different replicas of the landmark, either for recreational use or for engineering and research purposes can point to two issues: one resides in the vestiges of eurocentrism along history and taking into account culture, with its historicity being more amply represented through media. The other can be understood from a more pragmatic stance. As widely known monuments, they attract tourism to other regions away from the original site, offering a closer or even more affordable version of the monument and an extra to the simple enjoyment of nature [43]. It is, after all, a question of re-naturalizing culture and re-culturing nature [44].

Customarily, in Japan, a Buddhist temple is completed or connected by virtue of syncretism with a Shinto sanctuary. This also happens in China and Korea with the singularity that instead of Shinto we might have a Daoist precinct or a Muist element. Some argue that the Shinto religion is a unique Nipponese evolution of Daoism [45].

Nevertheless, at a funeral necropolis, it would be inauspicious to bring in or invoke the kami or spirits of the Shinto, which eventually represent the everlasting life-forces of nature and favour transmigration or transformation, thus in perennial conflict with death conceived as cessation.

Shintoism is the traditional religion of Japan and the only one endorsed by the Imperial Household after the Meiji Restoration of 1868. One of its main postulates is remote antiquity (real or feigned). In an island recently inhabited by the Japanese as Hokkaido were, it has often been controversial to enforce the “Way of the Gods” [35].

The most representative element of Shinto shrines is the Torii 鳥居. Such element can be defined as an elaborate wooden lintel painted in vermillion (Figure 22). The Torii exerts the complex function of beckoning and attracting the Sun, which is the paramount deity of the Shinto’s numerous pantheon (Amaterasu 天) and, therefore, an adequate symbol of Japan. This is reinforced by the ever-present sacred rope on display, called shimenawa しめ縄, with its zigzag paper fleece, representing sunrays, which decorates and blesses [46] the Torii or its annexed structures as the case may be [47]. Even the character of the word is formed with “bird” in the sense of the vermillion phoenix discussed at the Byodoin chapter. The underlying metaphor is that the sun would perch on the Torii much in the fashion the birds do.

Figure 22.

The famous Torii of the ocean shrine of Miyajima.

The insular nature of Japan as an edge of the world, opposed to the great continent of China, has suffered on occasion the comparison with the British Isles. After all, both island nations retain the system of a religious ruler unlike France and China in which the celestial-line of predestined monarchs was abruptly ended after violent revolutions [48], whilst in Japan the dynastic line was just restored in the 19th century.

The designers of the Takino park dared to imagine that lintels of recycled stone from the sculpture of the Buddha could be converted into a circular Torii, an open tumulus of sorts that would coincide with a Stonehenge-like profile, suitably fitting their purposes of attracting the public less prone to the Buddhist faith and evocate at the same time primitive beliefs of cosmic and archeological resonance in an intriguing or derelict location (Figure 23) [49].

Figure 23.

Stonehenge reproduction at Takino cemetery.

By invoking an improbable proto-historic past, perhaps inadvertently, the promoters of Takino created a unique opportunity of beholding an extraordinary landmark as pristine as in the same day of its erection, with no foreseeable problems of preservation unlike its Britannic counterpart. To the minds of the authors, the debate on authenticity and originality is somehow skipped since the original monument had no inscriptions, art, or reliefs of any sort. As we know, granite is an igneous rock as abundant in Japan as it is in England [19,43].

In this manner, intellectual curiosity for ancient monuments is completely satisfied in an idyllic surrounding and is hardly perturbed by the discrete interments of funeral ashes enshrined under the enge. Nature is most conveniently re-cultured [50]. It is interesting to remark that the orientation of the stone-blocks was somewhat altered (Figure 24 and Figure 25), as in the replica, shattered fragments of the lintels were not left to scatter on the ground. This has shifted the possible original solar or cosmic alignments although this extreme has not been fully demonstrated [51]. We should also notice that Stonehenge’s replica does not face the central axis formed by the Buddha statue but ends in a parallel path to that axis (See Figure 7).

Figure 24.

Plan of Takino’s Stonehenge replica. Due north is upside.

Figure 25.

Plan of the original Stonehenge monument. It is slightly tilted with respect to Figure 23.

At a given moment, the stone circle incorporated a sheltered altar (Figure 26) with three Buddha figures. This element was later removed as it produced mixed interpretations. Under the circle there is a glazed locked chamber accessible through stairs, which contains the ashes of the departed in some 400 air-tight metal niches. The number of urns can be expanded to a certain extent. Also, the sculpture of the Buddha was previously in direct visual connection with the stone circle. In the new configuration after 2017, this is no longer possible (Figure 9 and Figure 27), wherein the importance of the Stonehenge circle is strengthened and counterpoints the whole picture.

Figure 26.

The Stonehenge replica with a former Buddhist altar.

Figure 27.

The Stonehenge replica with the Buddha before the 2017 renovation.

2.3. The Moai Alignment

The third important nexus of the Takino complex is the row of 42 Moai. Moai are probably one of the most notorious remnants of the Rapa Nui People as well as the most recognizable icon of Easter Island. The standard Moai can be briefly defined as a colossal humanoid figure carved from the ashes of the Rano Raraku crater or any other volcanic material, with an oversized and elongated head composed of simplified and geometric lines [43].

Their bodies are minimalist, with arms resting at the sides or on the stomach. The legs are frequently imperceptible, although they suggest a crouched position (Figure 28). The torso rests on a ceremonial platform called ahu, which cannot be trodden under any circumstances, which replaces the lower limbs of the bodies. This sacred platform has not been respected at Takino cemetery, which could then be considered a sort of mockery of the original figures (Figure 29). The Moai could be detailed at times by a red crown or hat called Pukao and two rounded eyes made of coral or white conch.

Figure 28.

Ahu Akivi. Easter Island. Source: Author.

Figure 29.

The row of Moai at Takino cemetery. Source: Author.

Although the true meaning of the Moai is still under discussion, we are certain that they were a central piece of Rapa Nui society and are usually linked to the religious life of the islanders, often being understood as a representation of their deities or ancestors [44].

The Rapa Nui disappeared into the ashes of time, but their enigmatic giants can be compared to a variety of religious practices that exhibit similarities in numerous locations of Polynesia, the Lapita area of influence, and East Asia. We can name, in this group, the Tiki idols, the Filipino Anitos, and the Korean Dol Hareubang from Jeju Island, a territory where shamanism is still practiced today.

Korean shamanism, also known as Musok (무속/巫俗) or Mukyo (무교/巫敎), has demonstrated unparalleled adaptability and has managed to integrate into contemporary society, crossing boundaries even beyond the Han Republic. The Dol Hareubang (“stone grandfather” in Jeju dialect) became an emblematic figure of the Korean pop culture but is also a valuable part of the Jejuan own identity, a friendly and merry character who can be found on souvenirs shops or bagatelles, but who is also related to ancient beliefs that are still alive [44].

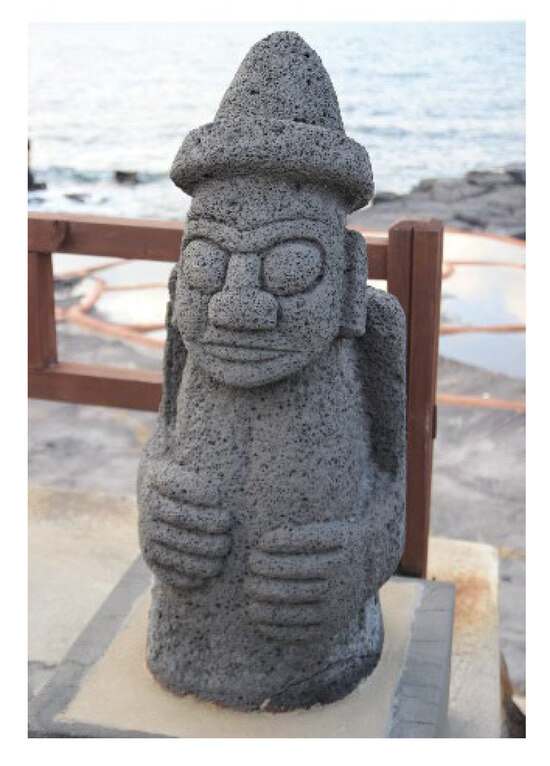

The Dol Hareubang (돌하르방/偶石木) bear substantial similarities to the Moai, although these are smaller (about the size of an adult or child, but this can vary) and maintain slightly more realistic proportions. The grandfathers are sculpted into the porous basaltic rock of Jeju Island, and their contour and facial features are substantially rounder and caricatured than those of the Moai, with large eyes and a flat, bulbous nose. The headpiece is now integrated into their heads, whose headdress has become a bowler hat, giving them a silhouette oftentimes described as phallic, thus associating the stone idols of Jeju with fertility (Figure 30).

Figure 30.

Miniature reproduction of the old man or grandfather of Jeju Island.

The arms typically rest on the tummy. Some Koreans identify this gesture with abundance or pregnancy, and it is said that touching the nose of a Dol Hareubang helps women have offspring, being Jeju Island one of the biggest tourist attractions for newlyweds on the peninsula. They feature integrated feet or bases, which were especially useful as they used to rest at thresholds or crossroads as guardian deities, in an analogous manner to which Haechi, protector and mascot of Seoul, did in mainland Korea [45].

The stone grandparents of Jeju Island are deeply connected with the local shamanism and are also referred as Beoksu Meori, “totem head” (벅수머리/法首). According to the Jeju tradition, the Dol Hareubangs serve as receptacles for the spirits, “grandfather” becoming synonymous with “ancestor”.

Other analogous characteristics can be observed in antique megalithic sculptures of pre-Columbian America, such as the Olmec art or more clearly the Colombian stone idols of San Agustin, the “Andean Easter Island” [48]. These discoveries seemed to reinforce earlier theories of pre-Columbian transoceanic contact, such as those formulated by anthropologist Paul Rivet or Thor Heyerdahl which were later discarded by evidence based on genetic tests [48]. Another archeological site outisde the Pacific where huge stone heads have been identified is the hierothesion of Antiochus I at Nemrut Dağı (Turkey), originally the statues belonged to seated gods but the heads were removed at some point [46], and now they bear a curious resemblance with Atama Daibutsu of Takino as only the head of the Buddha is visible over the hill. Although other authors may consider these coincidences as superficial or extravagant, the Moai mark the Eastern Edges of the World, something by which the Japanese archipelago is commonly identified (land of the rising sun). Theretofore, ancestral spirituality of the Pacific seems to permeate and symbolically connect, through archeological vestiges, places like Jeju, Easter Island and Takino Cemetery, at least for the imagery of the people.

Turning back to the general plan of Takino, the Buddha was situated between two symmetrical mounds, which define an important axis leading directly to the giant statue. The Stonehenge compound is at the end of another axis running parallel to the Buddha’s axis. Whereas the line of the Moai is segmented [52] and does not follow any of the principal directions related to the Buddha mound or Stonehenge’s circle. They seem to pass as wraiths encompassing the said landmarks.

Apart from the three main elements analyzed, other milestones were considered for the design of Takino cemetery, among them the archaeological ruins of Tiwanaku (Bolivia) and Machu Picchu (Peru), Angkor Thom (Cambodia) and different kinds of pyramids. However, they were deemed unrecognizable or not sufficiently related with funereal culture and were consequently discarded [53].

3. Results

The former discussion on the three distinctive elements of Takino funereal park leads us to the situation in which the original design needed significant alterations, and these were mainly performed by a thoughtful intervention of architect Tadao Ando [54].

Ando had designed and constructed several Buddhist temples in the past, especially in the island of Awaji, although he is better known in the West for his projects of christian chapels (Mt. Rokko and Hotel Alpha in Tomamu).

It is said that working on the construction or embellishment of a Buddhist temple or shrine may provide atonement for even the gravest sin and in any case it is considered a powerful boon towards indivual afterlife or reincarnation [55]. There are withheld rumours that due to his advanced age, the architect desired to be granted with these spiritual benefits and so accepted the controversial commission. Unfortunately, these confidential matters remain beyond the sphere of public domain, since personal religion is hardly ever discussed in the media in Japan. Be that as is may, this fact should not dissuade us to perform a thorough description the main intentions of the realized project in what they relate to the core of Japanese culture.

The first one could be perhaps something often forgotten but very important for Buddhism, while it is not directly visual, the power of thurification.

Aroma or perfume have in themselves the capacity of converting people to the true faith without being seen, which is why incense it is used consistently at all Buddhist temples. But in the sacred literature, we find examples of mountains or hills called incense burner, fragrant or perfumed; this was achieved in the past by the predominat vegetation joined to favourable breezes [56].

Ando pursued the creation of one of such fragrant hills on the selected spot. To that aim, he resorted to lavenders. They are not native to the island of Hokkaido but have become fashionable after some exports from Provence and given the availability of cultivable land on this region.

To ensure a persistent fragance, he employed an artifical plantation of 150,000 lavenders at regular intervals on the hemispherical hollow hill that he was to create to surround the Buddha.

When the plants are in full bloom, in this case by the end of June, they give the scent of the typical violet or purple flowers, which is quite unusual especially for the Japanese landscape. This strategy has become a dominant feature of the landmark (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Tadao Ando, Hill of the Buddha (2017), with Buddha’s forehead emerging from a field of lavender shrubs.

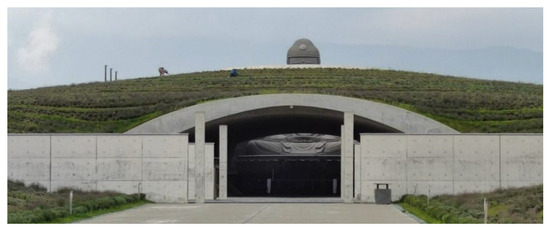

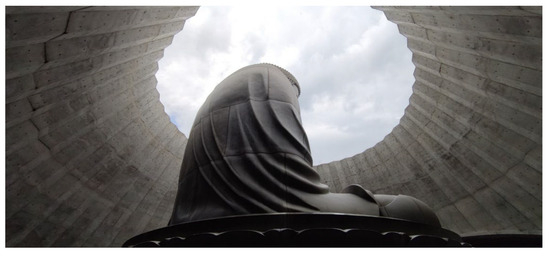

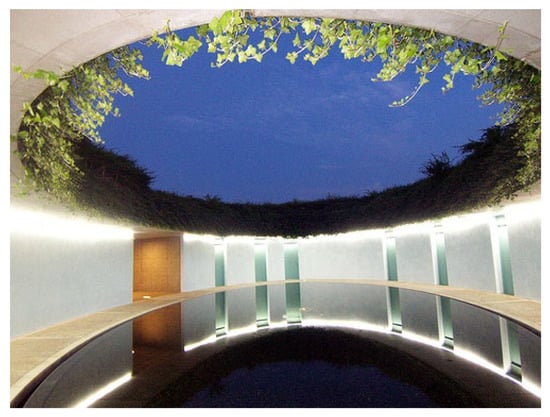

In a second important movement, Ando decides that beholding just the forehead of the Buddha is suitable for the visitors of the cemetery much in the same way as in the formerly described temple of Byodoin; therefore, he would create a kind of truncated dome, open to the sky, like the conical interior of a volcano, from which only the head will emerge. The dome, which encloses the statue had already been used at Seokguram (see above) and other rock-hewn monasteries in India and Sri Lanka (Figure 32 and Figure 33), but in that case it was mostly devoid of light.

Figure 32.

Tadao Ando, front view of the hill of the Buddha from the entrance arcosolium.

Figure 33.

Side view of the new realization with the head protruding.

The intervention of Tadao Ando subtly alterates the topography of the site until the body of the statue is no longer visible [57]. Still, the people desirous to pray or pay homage to the Great Buddha have accesended to the this inner massive chamber, which is conical in shape, by an elaborate passageway through the newly created hill. Such corridor is conceived as a half cylindrical tunnel but reinforced with concrete folded plates on the inner vault.

The passageway is frontal to the sculpture, which has been rotated and relocated for the new project. However, progression to it is not straighforward because of the hidden mechanisms that the architect has devised (Figure 34).

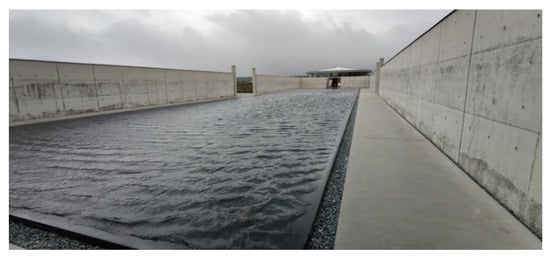

Figure 34.

Sectional scheme of the Buddha Hill.

In the new project, we arrive to a ceremonial pond, which cuts the main axis and forces the visitor to take a pronounced detour around it, almost a circumambulation. The basin’s surface is concave and prevents water splashes regardless of the wind condition, which can be steady around this area [58]. The floor of the stank is made of black marble and that gives the water a swarthy appearance, which, added to the myriad of ripples that form in the agitated surface, resembles the mythological Styx river, which the deceased were forced to ferry on Charon’s boat in order to disembark on the Hades (Figure 35).

Figure 35.

Side view of the black pool with aisles and concrete walls.

Thus, we are confronted with an eerie entrance to the underworld of the necropolis. A recreation of sorts of Kyoto’s karesansui precincts, in this occasion not through a vital albeit inorganic garden but with a sullen and lifeless courtyard, it is as Hölderlin described in his famous verse [59]: “the Walls stay speechless and cold”.

For the device of the oblong basin, it is coupled with a panelled concrete wall of reduced height. Lofty enough to impede the view from the outside while at the same time beckoning the grey sky to a stifled threnody.

With the so-created chicane of the lateral aisles of the pool, which reminds us of the sinuous corridor entrances of Egyptian temples in the ideas of Giedion and Le Corbusier [60], Tadao Ando forces us all but to crouch to regard the dark flow of water, and our gaze inevitably meets the reflection of the obscure cloudy sky on the grey diffuse walls and the liquid surface. We instantly known that we are close to being admitted to the presence of something supernatural.

At this point, we could agree with the Italian artist Edoardo Persico, who, praising the racing course at the roof of Fiat Automobile factory of Torino, wrote: “Under the skies and before God only the pond (track) is free” [61].

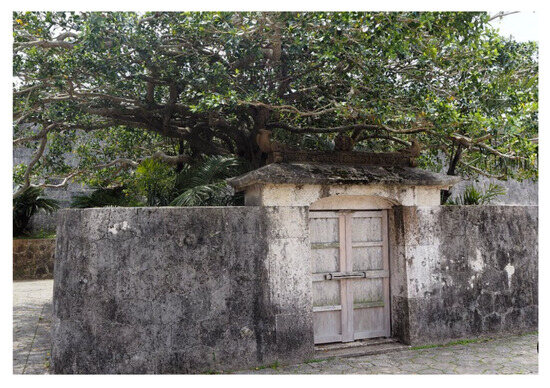

The extraordinary feature of low-height dense and opaque walls produces a secluded space, which is present at some Zen gardens and yards throughout Japan, although it is perhaps more clearly represented in the Suimui Utaki Garden Temple, at the entrance of Shurijo Palace in Naha (Okinawa, Rikyu Islands). It is known that when the king of the Rikyus visited a temple or shrine outside the Shurijo, he would open the gates and offer prayers at this diminutive shrine, and the priestesses would perform exquisite ceremonies (Figure 36). The plants within the rare masonry wall are banyan trees and Japanese laurels [62].

Figure 36.

The Suimui Utaki garden temple. Shurijo (Okinawa).

After traversing the black pool (Figure 37), we get through the vaulted arcosolium (an arch under which interments are performed), a sort of tunnel 40 metres long at the end of which stands the surmised body of the statue, and a whitish marble light shines at the extreme [63]. Nonetheless, only when we enter the chamber that is open to the sky are we allowed to contemplate the long-sought hallowed face (Figure 38).

Figure 37.

Side cylindrical pavillion at the extreme of the black pool.

Figure 38.

The Great Buddha inside an open conical dome.

Finally, we have reached the sacred hall or garbagriha in Sanksrit terms. The space in which the deity manifests and where enlightment should take place for those who keep a pure vision (Figure 39). This huge conical space is somehow otherworldly, to walk around an inclined cone wall of huge dimensions is by no means comfortable but then we realize of the small chapels that surround the great Buddha; in them, different bosatsu (boddhisattva) and arahats (distinguished disciples) are worshipped. It is again a sublimated space in which the physical body must be transformed into a spirit, only at that moment we raise our heads and look to the zenith, from the Arabic word “semt” سَمْت, which means the path.

Figure 39.

Zenithal vision of the conical dome.

4. Discussion

Founded on the previous results, the authors can demonstrate a tendency in Buddhist religious architecture, which reveals specific structures colligated to a sort of all-pervading cosmic harmony. This pertains to a well-rooted Asian tradition that should be increasingly recognizable in the years to come. In the authors’ theory, such designs based on archeology show a clear direction for the recreating spaces of spirituality in Eastern Asia [63].

For instance, as we have just seen in the hill of the Buddha at Takino, in fact a concrete shell, with pleated or folded panes, the protruding head of the Buddha is now oriented to the northwest, exactly the sunrise position of the summer solstice, known in Japanese as Geshi 夏至.

In this magnificent roofless structure, Tadao Ando is able to reconcile his main two design paradigms and interests. The first one is the sunlit volume revolving around a centre that he exemplifies in the Roman Pantheon (Figure 40). He has frequently pointed out that such space cannot exist in nature, but it is naturalized by the due course of the sun and the seasons. That is the conceptual reason why the Buddha statue cannot be completely covered for instance with a glass dome, let alone technical hindrances, as it would have prevented climatic events from happening.

Figure 40.

Roman Pantheon. Scheme of proportions that reveals the perfect sphere enclosed by its structure.

The second one, reinforcing the first, would be a yearning for total integration with nature and specifically with wind and water, the ingredients that enhance the growth of vegetation and the well-known fundaments of Feng Shui 風水. For instance, with the plantation of blossoming violet lavenders, the architect is capable to ensure a distinctive colour in the project for each one of the four seasons in accordance with the Daoist tetralogies, similar to Heidegger’s Geviert (or the Fourfold, earth, sky, mortals, and immortals) [64], for winter it would be the white in the snow, in spring the lush green of the new leaves, fragrant purple flowers of lavender to the summer, and finally red brown for the fall.

A thorough cosmic reconstruction of the Universe is performed in this open dome shrine. The philosophical ideas underlying Buddhist order, such as the concept of Garan 伽藍are sustained. This term originally meant a monastery yard but evolved to signify the harmonic realm created by the Buddha known as Konpon Daitô 根本大塔 [64,65] or axis mundi. The secluded space conceived for the Buddha along with his entourage, radiate and resonate in unison as a celestial harp through the land (Figure 41).

Figure 41.

Perspective Scheme of the Buddha Hill and the traverse black pond.

But we must be advised that reducing or concealing the importance of the Buddha, with the hill operation described, also implies increasing the effect of the other heathen temples and statues, particularly the reconstruction of Stonehenge. There seems to be only a slight connection between them although we believe that deep inside they both honour the ancestral Japanese tradition of Mukaebi 迎え火.

Mukaebi, roughly translates as the welcome back fire. In ancient Japan, the ashes of respected ancestors and especially of young children were not interred in communal cemeteries, instead they were deposited near the threshold or entrance fence of a household. By treading over the cinders, the parents pined for the rebirth of their departed infants, especially in the wombs of fertile wives. Such ceremony has been maintained to our days and is performed each year to initiate the Obon season in July or August, depending on the region [66]. When the embers of the homecoming ritual fire are extinguished and turn to ashes they are buried near the small entrance garden conducing to a house and all the members of the family need to walk once over them, pleading for eternity.

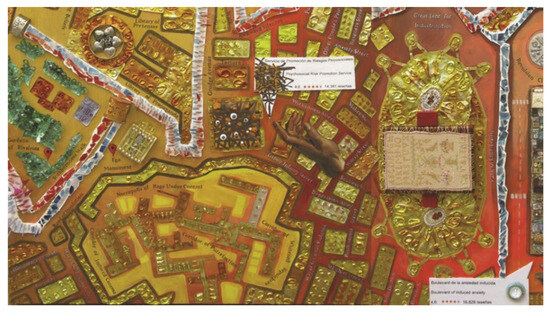

In Takino, all the cinders, by the thousand, are deposited near the entrance and in the circular pavilions of the shrine of the great Buddha or the threshold of the Stonehenge in special sealed chambers; therefore, such ancestral ritual is re-enacted almost inadvertently every single time a visitor enters the said monuments [32,67,68]. The notable work of Ando with deft organization of an underground sustainable architecture has inspired other artists and colleagues inside and out of Japan to explore the concepts of hypogeal spaces like a catacomb or necropolis. Some of them are James Turrell (Figure 42 and Figure 43) and Inmaculada Rodriguez Cunill (Figure 44). In the Naoshima art garden, Turrell has collaborated with Tadao Ando [69] to produce elliptical voids intended to contemplate the lights from the sun and the sky combined, especially at twilight. One of them has derived into a hotel for visitors (Figure 42).

Figure 42.

James Turrell and Tadao Ando. Eco-Hotel at Naoshima.

Figure 43.

James Turrell. Second Wind. Vejer de la Frontera. Spain.

Figure 44.

Excerpt from the “Wolf Pack City” showing the Necropolis of rage under control. Some of the wings of the building suggest broken swastikas. Work by artist I. Rodriguez Cunill (2021).

In Spain, Turrell’s work at the Montenmedio Hacienda (Figure 43), a natural open-air space of international resonance (supported by the contemporary art museum CARS), shows echoes of the cases examined above. The concealment of the central motif and its occasional appearance thanks to the solar cycle, point to an asceticism that characterizes most of Turrell’s work [70,71].

On the other hand, the work known as Wolf Pack City (Figure 44) uses light through recycled materials that reflect luminous flux as if they were gold or silver (but they are not—it is actually refuse) and keeps the remains of despondent citizens through the names of those who could not achieve peace. Far from being a space to rest (it may seem so by the denomination of “necropolis”, by the apparent noble materials, etc.) it is rather a space of rage, where we find a “corridor of the putrefaction” of the bodies, or a “corridor of the whitened sepulchres” (alluding to the biblical phrase of Christ). Such peculiar necropolis represents the utmost extreme from a space of tranquillity and transcendence. It is more of a scream of anguish than the silence conveyed by the halls of the Buddha discussed previously. The darkness of the catacombs is replaced by the (false) ostentation of the materials that conduce to light through reflection [72]. Although we might be critical with the eventual commercial use of one of the short symmetric cylindrical pavilions at the side of the entrance pond (Figure 45), in the end we recognize that Tadao Ando’s formidable proposal evolves in the following sense: at first just intends to conceal by stealth the towering Buddha, which was found intimidating by the visitors. Later he arrives to a very keen solution of surrounding the statue with an artificial hill and an inner dormant volcano. Finally, upon the so-created cone, once it erupts, flowers of Mandala will rain as specified in the Lotus Sutra 雨曼陀羅華. To perfect the metaphor, these flowers should have been wysterias (Fuji 藤) but resulting impractical at this place, he has substituted them with more resistant lavenders [73,74]. It is a regal echo of mount Fuji (富士山) and a suitable crown for the Majesty of Death, whose virtue solely is to be allowed immortality.

Figure 45.

Side view of the black pool with short cylindrical pavilion for part of the funeral urns.

5. Conclusions

With these results and discussion, we have brought to the surface how, in a somewhat remote region of Japan, imagined archeological vestiges have been put to work to create an attractive park, privately owned, and managed, which serves as an expansive green area and at the same time satisfies the afterlife aspirations of the community, although with a considerable cost. An artificial earthen shell that generates an open dome shrine has been executed. The renovated complex is provided with ceremonial access and other facilities intended for religious services. The intervention completed by Tadao Ando is successful as much as it is able to colligate purposes of architectural excellence with religious and teleological yearnings. The power of archeology to provide significance to funereal monuments that are in this way transformed into necropolises and cities of the dead is remarkable, and it can even revalorize the land use. For instance, we know that Varanasi in India is a city to die in, to avoid reincarnation and the tiresome wheel of samsara. Still, we may wonder if the transition from life to death is operated smoothly in the cities in which we inhabit or rather is the other way round. At any rate, it is an enigmatic process that has inspired contemporary artists like Noguchi, Mishima, Turrell, and Rodriguez-Cunill.

The latest realizations at Takino introduce a new dimension of Buddhism ascetics, probably inaugurated by the Ajanta Caves in India, that is, the hidden grotto or monastery. In this manuscript we have detailed how the evolution from the ceremonial tumuli to the Buddhist chaitya must have been a strenuous process involving years of planning and painstaking labour.

It was raised when the adepts of the Buddha, especially of the Lesser Vehicle prevailing branches, at the times of monsoon weather for instance, could not reach out of their monasteries to preach or collect alms and, therefore, decided to work in the underground to spruce their halls of prayer and meditation. The tradition of showing the face of the Buddha unlike the adytum of Indian temples or the concealed Buddha represents the transition from Hinayana or esoteric Buddhism to the more social religiosity of the Mahayana, which prevails now in Japan and Korea and at a former time in China. In Japan, it appeared earliest at the Byôdoin Temple discussed in the article.

A revealing example of how this transition has operated in some cosmological aspects of the project of the Hill, is that the original position of the Buddha at Takino, which was faced as usual to the south, has turned to face the northwest to mark the sunrise on the summer solstice.

At the time of completing the Hill of the Buddha project, the promoters of Takino Park faced another key decision as if to give a new entity and reinforced interest to the Stonehenge ring by having veiled the importance of the Buddha.

There was, in Japan, a historic period referred to as Sakoku 鎖国, or the “enchained country”, in which no one was permitted outside the archipelago for any reason, and that included the Japanese inhabitants themselves. Such extreme insularity has resulted to our minds in a necessity of marking the edges of the world with monuments, and in this way establish a bond with other isles no matter how remote. This would explain why the Moai from Ester Island and the Stonehenge circle have been brought forth to the collective imaginary at this cemetery in Sapporo.

The insight that the authors propose after studying in deep Takino funereal park is that invoking archeology provides us with a powerful and effective tool to establish a surefooted path of creation towards a more serene landscape architecture, which, in turn, renews the much desired link between human constructions, culture and nature or, in other words, an alternate road to endurance through sustainability. The answer that it offers to the eternal question of how are we to live is as such: be boundless like the Sky and the four Directions, sustain all the creatures in your love.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.-L. and I.R.-C.; methodology, J.C.-L.; software, C.P.-B. and M.G.-V.; formal analysis, M.G.-V. and C.P.-B.; investigation, J.C.-L. and I.R.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.-L. and I.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, V.M.-S.; visualization, M.G.-V.; supervision J.C.-L. and I.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

J. Cabeza-Lainez wants to praise the creative genius of Mishima Yukio. The forgotten sons are remembered. Many thanks to Mattarena Tuki from Hangaroa and Antonio Rodríguez de las Heras for his kind help. I. R.-C. wishes to pay homage to Eva Guill-Walls, also recognizes Maria Luisa Rodriguez Cunill and Antonio Maestre Cernadas. V. Marquet-Saget expresses deep gratitude towards his grandfather, affectionately called ‘Boby’, who first introduced him to the wonders of architecture. César Puchol wants to thank Andrea Kalff and her family for offering sustenance in Hawaiian travels. Miguel Gutierrez-Villarubia would like to thank Iulia Sanchez Martin for contributing with photographs and exploration of Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hudson, M.J. Ruins of Identity. Ethno-Genesis in the Japanese Islands; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1999; ISBN 0824821564. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.-S. Gyeongju, the Heart of Korean Culture: A UNESCO World Heritage; Hanul Publishing Group: Paju, Republic of Korea, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Umesao, T. An Ecological View of History. Japanese Civilization in the World Context; Trans Pacific Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2003; ISBN 9781876843892. [Google Scholar]

- Umesao, T.; Befu, H.; Kreiner, J. Japanese Civilization in the Modern World: Life and Society; Senri Ethnological Studies: Osaka, Japan, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Umesao, T.; Jennison, R. Japan as Viewed from an Eco-Historical Perspective. Rev. Jpn. Cult. Soc. 1986, 1, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Watsuji, T. Climate and Culture: A Philosophical Study; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.-J. Smiles of the Baby Buddha: Appreciating the Cultural Heritage of Kyongju; Changbi Publishers, Inc.: Paju-si, Republic of Korea, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzichristodoulou, M.; Jefferies, J.; Zerihan, R. (Eds.) Interfaces of Performance; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero-Andujar, F.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Comparative, geometric and structural analysis of the Sokkuram Temple at Kyongju (Korea). In Proceedings of the Second National Symposium on Cultural Heritage of Korea, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 11 November–3 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza Lainez, J.M. La Visión y La Voz: Arte, Ciudad y Cultura En Asia Oriental; UCOPress Ediciones Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olcina Cantos, J.; Martin Vide, J. Influencia del Clima en la Historia; Cuadernos de Historia; Arco Libros—La Muralla, S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza Lainez, J.M. Desde Sri Lanka hasta Japón: Ideas acerca de la evolución del Stupa. In La investigación sobre Asia Pacífico en España; San Ginés Aguilar, P., Ed.; Colección Española de Investigación sobre Asia Pacífico 1; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2007; pp. 553–570. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero Andujar, F.; Rodriguez-Cunill, I.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.M. The Problem of Lighting in Underground Domes, Vaults, and Tunnel-Like Structures of Antiquity; An Application to the Sustainability of Prominent Asian Heritage (India, Korea, China). Sustainability 2019, 11, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, G.L. Ritual Poetry and the Politics of Death in Early Japan; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Cunill, I.; Gutierrez-Villarrubia, M.; Salguero-Andujar, F.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Sustainability in Early Modern China through the Evolution of the Jesuit Accommodation Method. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, M. The Pearly Gates of CyberSpace; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L. Hermeneutics of Sacred Architecture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; 2 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, W. Milton a Poem, Copy B Object 2; Eaves, M., Essick, R.N., Viscomi, J., Eds.; The William Blake Archive; British National Library: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuie, M. The Summer House; Kindle ed.; Libros del Asteroide: Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bollnow, O. Human Space; Hyphen Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, J.C.; Boyd, M.J. From Stonehenge to Mycenae: The Challenges of Archaeological Interpretation; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Pearson, M. Stonehenge: A Brief History; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ramswamy, S.G. Design and Construction of Concrete Shell Roofs; CBS Publishers & Distributors: New Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Darvill, T.; Marshall, P.; Pearson, M.P.; Wainwright, G. Stonehenge Remodelled. Antiquity 2012, 86, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, A.A.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.; Xu, Y. Unknown Suns: László Hudec, Antonin Raymond and the Rising of a Modern Architecture for Eastern Asia. Buildings 2022, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, R. The Making of Stonehenge; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. Stonehenge; Harvard University Press: Boston, MS, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleal, R.M.J.; Walker, K.E.; Montague, R. Stonehenge in Its Landscape: Twentieth Century Excavations; Archaeological Report 10; English Heritage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J.M.; Salguero-Andújar, F.; Rodríguez-Cunill, I. Prevention of Hazards Induced by a Radiation Fireball through Computational Geometry and Parametric Design. Mathematics 2022, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Millán, P.M.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. HBIM Methodology to Achieve a Balance between Protection and Habitability: The Case Study of the Monastery of Santa Clara in Belalcazar, Spain. Buildings 2022, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, L.; Martzloff, J.C.; Baldini, J.; Dhombres, J. História Das Ciências Matemáticas: Portugal e o Oriente—History of Mathematical Sciences: Portugal and East Asia; Fundação Oriente: Lisboa, Portugal, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson, J.H. Korea: A Religious History; RoutledgeCurzon: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 0-7007-1605-X. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, A.; Sokol, A.K. Another Kyoto; Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0141988337. [Google Scholar]

- Bunko, T. Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library); Publications—Tōyō Bunko. Ser. B; The Toyo Bunko: Tokyo, Japan, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Salguero-Andújar, F.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.-M. New Computational Geometry Methods Applied to Solve Complex Problems of Radiative Transfer. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J.M.; Pulido-Arcas, J.A. New configuration factors for curved surfaces. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2013, 117, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J.M.; Xu, Y. Empire, Science and Geometry at the origins of early modern architecture. Symmetry Cult. Sci. 2020, 31, 321–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganoff, I. Berechnung Von Kugelschalen Über Rechteckigem Grundriss: Mit Berechnungsdiagrammen; Mitteilungen aus dem Institut für Massivbau Hannover; Werner: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. Innovative Tool to Determine Radiative Heat Transfer Inside Spherical Segments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doganoff, I.; Hoffmann, C.; Rühle, H. Shell and Fold Structure Roofs out of Precast, Pre-Stressed Reinforced Concrete Elements; Bulletin of the International Association for Shell Structures: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, H. The Column Analogy: Analysis of Elastic Arches and Frames. Available online: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/5207 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Cabeza-Lainez, J.M. Las bóvedas de cerámica armada en la obra de Eladio Dieste. Análisis y posibilidades de adaptación a las condiciones constructivas españolas. In Actas del Tercer Congreso Nacional de Historia de la Construcción; Santiago, H., Ed.; CEHOPU: Madrid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. Architectural characteristics of different configurations based on new geometric determinations for the conoid. Buildings 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, C. Dome Architecture in Ancient Asian Art and Seokguram Grotto: In comparison with Western Dome Constructions. Korean J. Art Hist. 2022, 313, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessi, U. Religious Diversity in Japan. In Religious Diversity in Asia; Borup, J., Fibiger, M.Q., Kühle, L., Eds.; BRILL. ProQuest Ebook Central: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 48–66. ISBN 9789004415812. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P. An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History and Practices, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0521676748. [Google Scholar]

- Uchio, T.; Harrison, B. Japanese and Easter Island—Ecotourism and the Relationship with Local Residents. Jpn. J. Policy Cult. 2024, 32, 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lipo, C.P.; Hunt, T.L.; Haoa, S.R. The ‘walking’ megalithic statues (moai) of Easter Island. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 2859–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Seokguram Grotto and Bulguksa Temple. UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/736/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Puchol, C.; Chon, S.-S. Overseas propagation of Korean Shamanism through Diaspora movement and the linage ‘New York Musok’”, 실천민속학연구 제40호. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002877487 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Zucker, P. Ruins. An Aesthetic Hybrid. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1961, 20, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipo, C.P.; Hunt, T.L. Mapping prehistoric statue roads on Easter Island. Antiquity 2005, 79, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. Finding the Exact Radiative Field of Triangular Sources: Application for More Effective Shading Devices and Windows. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, C.; Wilhelm, J.L. An environmental aesthetic approach to ruins: The situativity, relationality and emergence of experiences in a derelict sanatorium. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2024, 26, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Cunill, I.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.; Lopez-Cabrales, M.d.M. Art and the City Fiction in Japanese American Internment Camps: Sequels for Resiliency. Arts 2023, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. A New Principle for Building Simulation of Radiative Heat Transfer in the Presence of Spherical Surfaces. Buildings 2023, 13, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero-Andújar, F.; Prat-Hurtado, F.; Rodriguez-Cunill, I.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Architectural Significance of the Seokguram Buddhist Grotto in Gyeongju (Korea). Buildings 2022, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cunill, M.I. Algunas precisiones en torno al marco en la obra transitable. Bol. Arte 2018, 551–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. New Geometric Theorems Derived from Integral Equations Applied to Radiative Transfer in Spherical Sectors and Circular Segments. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, J.G. La rama dorada: Magia y religión; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2021; ISBN 9786071606464. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Villarrubia, M.; Cabeza Lainez, J. La majestad de la muerte. In Postrimerías, Valdés Leal desde la Facultad de Bellas Artes de Sevilla; Infante del Rosal, F., Arjonilla Alvarez, M., Bilbao Peña, D., Eds.; Colección Catálogos, n.° 1; Editorial Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2022; ISBN 9788447224043. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, L. The Mythology in Our Language. Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough. HAU Books: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781912808403. [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, Y. The Temple of Dawn; Shinchosa: Tokyo, Japan, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmunsen, C. Wittgenstein and Buddhism; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 9781349031306. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H. 明朝帝王陵 (增订版) [Mausoleum of the Emperor of the Ming Dinasty Ming (Revised Edition)]; Xueyuan Editorial: Beijing, China, 2013; ISBN 9787507742718. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. 中华文明史视角下的陵墓考古 (Archaeology of the mausoleum from the perspective of the History of Chinese Civilization). People’s Trib. 2021, 32, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada-García, S.; Valero-Flores, P.; Mendoza-Alvarez, D.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Cognitive Accessibility in Rural Heritage: A New Proposal for the Archaeological Landscape of Castulo. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.Y. Smaller is Better. Japan’s Mastery of the Miniature; Kodansha USA Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mengke (s.f. [c. 300 a.C.]). 孟子·告子章句上 (Mencius Gaozi, Chapter 1).

- Wang, Z.; Guo, W.; Zuo, X. 明十三陵整体空间营造手法探讨 (Dissertation on general techniques of spatial construction of the Ming Tomb). In Space Governance for High-quality Development, Proceedings of the Annual National Planning Conference of China (ANPCC), Chengdu, China, 25–30 September 2021; Urban Planning Society of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- You, W.B. 中国 “儒、道、佛” 生死伦理观比较 (Comparison of the Ethics of Destiny between Chinese philosophy of confucianism, daoism and buddhism). 中国医学伦理学 Chin. Med. Ethics 2008, 21, 116–117+125. [Google Scholar]

- Xunzi (s.f. [3rd Century b.C.]. 《禮 論》 (Theory of the Rites).

- Peña-García, A.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Daylighting of road tunnels through external ground-based light-pipes and complex reflective geometry. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cunill, M.I. Medio ambiente, videoinstalaciones y otras propuestas artísticas audiovisuales. In Medios de Comunicación y Medio Ambiente; Gutiérrez-SanMiguel, B., Ed.; University of Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2002; Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=294636 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).