1. Introduction

The sustainable management of properties inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, including the Studenica Monastery, is a multifaceted endeavour that integrates the protection of the site’s outstanding universal value [

1] with sustainable development objectives. This approach facilitates the long-term planning, organisation, and evaluation of activities, both within the protected property and in its wider environment, in accordance with the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention [

2]. The effective protection and preservation of cultural heritage is contingent upon the management of the entire territory/region as an integral component of planning and conservation strategies [

3].

The concept of cultural heritage has been expanded to encompass intangible values and the wider landscape context, thus establishing a strategic framework for the sustainable development and protection of the area surrounding the Studenica Monastery. A fundamental element of this strategy is the acknowledgement of the monastery’s profound spiritual and historical resilience, which serves as the nucleus of a distinctive cultural landscape. The network of sacred sites that has developed around Studenica over the centuries is evidence of this resilience and contributes to the survival and adaptation of local communities in their natural environment [

4]. Spatial planning constitutes a pivotal instrument for the safeguarding and administration of World Heritage sites, thereby facilitating the integration of heritage conservation objectives with broader development policies. The development of the Special Purpose Spatial Plan for the Studenica Monastery represents a significant instrument for the implementation of a sustainable development and management strategy for this cultural landscape, in conjunction with the Management Plan for the Studenica Monastery.

This paper proposes a model for the sustainable management of the cultural landscape of the Studenica Monastery, analysing spiritual resilience as a key component leading to the interconnection and interdependence of natural, cultural–historical, and spiritual values.

The introduction provides a comprehensive overview of the theoretical concept of “spiritual resilience”, elucidating its role and significance within the context of the UNESCO site of the Studenica Monastery. The section on materials and methods demonstrates the interdisciplinary approach, encompassing spatial, historical, ecological, and ethnographic analyses, GIS modelling, and field research. The results demonstrate that the network of sacred sites and living spiritual traditions have facilitated the preservation of identity and ecological balance despite complex, centuries-long historical challenges. The discussion highlights the importance of spatial planning and the implementation of the Special Purpose Spatial Plan and the Management Plan for the UNESCO site, the strengthening of the local community, and the development of sustainable tourism to address the identified issues of depopulation and infrastructural limitations, with guidelines for future research arising from the recognised scope of such a study. The research posits that the monastery, in its capacity as a spiritual institution and cultural centre, functions as a nexus for the resilient and sustainable management of cultural landscapes, proffering universal models of harmony among humans, nature, spirituality, and tradition. The present study employs a research approach that underscores spirituality as a pivotal element in the comprehensive conservation of both cultural and natural heritage. This encompasses locations that may not be included in the World Heritage List or subject to its conservation policies.

Theoretical Framework: The Concept of Spiritual Resilience

Strategic documents, including the European Landscape Convention and UNESCO categories of cultural landscapes, have redefined heritage as a dynamic whole, where natural, cultural, and spiritual elements intertwine. This novel approach has facilitated the recognition of the landscape surrounding the Studenica Monastery as a living system, the identity of which is derived from millennia of interaction between human beings and their environment.

The evolution of the concept of cultural heritage since the late 20th century has marked a shift in focus from exclusively architectural and material aspects to a broader and integrated understanding, encompassing natural, historical, spiritual, social, and intangible values. These are recognised as an inseparable part of shared cultural identity and the sustainable development of communities. The 1972 Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage provided clear definitions of the criteria, according to which groups of buildings, by virtue of their architecture and their integration into the landscape, represent outstanding universal value from the historical, artistic, or scientific point of view (Article 1, paragraph 2). However, the concept of cultural landscape as a specific and extended category of heritage was adopted by the World Heritage Committee in 1992 and confirmed in the revision of the Operational Guidelines (paragraphs 36 to 42). According to the Convention, the term “cultural landscape” is defined as “the variety of expressions of the interaction between culture and nature that have shaped the environment over time, resulting in the landscapes of today” (paragraph 37). This concept has been institutionally expanded and reinforced by the European Landscape Convention, which defines landscapes as dynamic assemblages shaped by the interaction between nature and human activities [

5]. The Convention underscores the necessity for a holistic approach to management by integrating environmental, economic, and social policies. Conventions such as the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [

6] and the Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society [

7] have further expanded the concept of cultural heritage, encompassing the practices, rituals, and collective memories of communities. Having underscored the pivotal role of communities and humans in the preservation of cultural heritage, these conventions have consequently laid the foundation for intricate environmental research and led to the enhancement of conservation policies for natural, cultural, and spiritual heritage. The intricacies of theoretical and practical approaches are reflected in the consideration of the concept of the environment, encompassing both the cultural and natural aspects of heritage. This dualistic perspective is particularly evident in the study of the cultural landscape, encompassing its aesthetic and ethical values [

8].

It is evident that, as a consequence of this trajectory, a plethora of declarations and charters have come to the fore, addressing the intricate issues associated with the preservation and management of cultural heritage. Two documents that are of particular significance for the purposes of this present paper are the Quebec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of Place, which represents a synergy between material (buildings, sites, landscapes, streets, objects) and intangible elements (memories, narratives, written documents, rituals, festivals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colours, odours, etc.) [

9], and the Charter on Cultural Routes, which defines cultural routes as dynamic systems that link material and intangible elements through historical, natural, and cultural aspects, enabling sustainable development through the protection, presentation, and promotion of routes as integral entities [

10]. That paradigm shift in the interpretation of heritage signifies a transition from a static and unchanging remnant of the past to a “living” and dynamic cultural heritage. This cultural heritage must not be a mere integral part of the context in which it exists but must also actively reflect, interpret, and adapt to the values, needs, and challenges of the time in which it lives, thereby ensuring its relevance to contemporary society and its sustainable development. That shift in perspective signifies a paradigm shift in the interpretation of heritage, marking its transition from a static and unchanging remnant of the past to a living and dynamic cultural heritage. It is evident that by engaging in active reflection, interpretation, and adaptation to contemporary values and challenges, heritage maintains its relevance within society and supports sustainable development. This transition has been demonstrated to engender sustainable cultural tourism, as investment in place branding has been shown to assist in the preservation and promotion of both tangible and intangible heritage [

11]. Cultural routes integrate the value of natural and cultural heritage and consider their environmental, economic, and tourist potentials, establishing the integrity of different forms of heritage.

The Florence Declaration is a seminal text that emphasised the importance of integrating the management of cultural and natural heritage. It placed people at the centre of the heritage debate so that landscapes contribute to community identity, the quality of life, and sustainable development [

12]. This document has established the foundations for the integrated management of cultural and natural heritage, emphasising the importance of involving local communities and their practices in the conservation process. This transformation of cultural heritage from a static remnant of the past into a living entity that actively contributes to contemporary society, reflects its values, and adapts to the challenges of the present and the future is pivotal.

In this context, the concept of resilience has emerged as pivotal in comprehending landscapes as adaptive systems capable of withstanding demographic or economic shifts without compromising their intrinsic character, provided that critical thresholds triggering structural change are not exceeded. This approach, defined as “the ability of a system to maintain its function in the face of shocks” [

13], requires the monitoring of key indicators of adaptability, flexible planning, and the incorporation of local knowledge into management processes [

14]. This understanding of resilience as a unifying concept serves to integrate traditional conservation practices with contemporary challenges, thereby transforming landscapes into living systems capable of sustainable evolution [

15].

The incorporation of resilience thinking into urban planning and design has been a concept in existence for over two decades. It relates to harmful influences and hazards in cities, with the objective of measuring the capacity of systems (objects or individuals) to survive disruptions by maintaining acceptable levels of functionality and returning to pre-disruption levels of functioning in a timely manner [

16]. The concept of resilience, borrowed from the study of ecology, particularly the concepts of sustainability and the adaptability of living systems, has been applied in architectural and urban scientific, theoretical, and applied practices through engineering resilience, ecological resilience, and adaptive resilience [

17]. The concept of engineering resilience is centred on themes pertaining to architecture, construction, infrastructure, and urban design, with a primary focus on the capacity of physically constructed structures to resist and minimise vulnerability in the face of disasters and adverse environmental impacts [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Adaptive resilience, also termed community resilience, is defined as the capacity of a community to manage current and emerging threats by developing the ability to adapt to changing threats and challenges over time [

22]. This approach underscores the pivotal role of public participation and capacity building in both urban and rural areas, which represent socio-ecological systems where individuals are intricately interconnected [

23,

24].

The concept of ecological resilience, in contrast, signifies a substantially more dynamic and flexible approach to the resilience of a spatial environment. It is predicated on the promotion of construction, human influences, and activities within a natural system up to the limits that will not threaten the balance of that system [

25]. The concept of ecological resilience emerged in the 1970s and has been the source from which the concept of resilience has been transferred to other disciplines [

26]. Consequently, the terms “ecological resilience” and “environmental resilience” are often used interchangeably to denote the capacity of living natural systems to absorb changes, reorganise, and recover from disruptions, ultimately reverting to a stable state [

27]. This approach is underpinned by an environmental perspective, emphasising the interplay of natural, cultural, and spiritual elements in shaping the sacred landscape surrounding the Studenica Monastery. This landscape, imbued with its historical significance, serves as a testament to the concept of environmental resilience, underscoring the capacity for adaptation and renewal within complex systems.

The introduction of the term “spiritual resilience” is predicated on research into the impact of religious experiences and beliefs on natural landscapes, the topographical transmission of the sacred dimension through sacred monuments, and the responses of human communities to environments filled with religious meaning. The conceptualisation of those meanings in spatial dimensions has been explored through the theoretical framework of “sacred space”, which does not delineate a clear distinction between ritual spaces and sacred places, both of which are pertinent to the study of religious materiality in landscapes [

28,

29]. The introduction of the concept of “hierotopy” by Lidov has attempted to define this field of research more precisely [

30,

31], opening up many scientific debates. The study of the functions of sacred places and their role in religious and social experience is further complicated by different interpretations of the terms “sacred”, “sacral”, “place”, “location”, and “space”, which are often used as synonyms [

32].

The absence of universally accepted terms at the anthropological and sociological level has resulted in the definition of certain places as “sacred”, which are linked to a wider spatial context and distinguished from “sacral” or “ritual spaces”, being based on terms used in legal documents on the protection of cultural heritage. The term “sacred place” denotes the embodiment of a dimension of sacredness associated with a specific locale, thereby conferring upon it a character that is unique and recognisable to the community, as evidenced by manifest facts. Furthermore, it implies the recognition by people of the inherent sacredness of a place, often expressed through natural features. Consequently, sacred places that are part of the landscape form networks of sacred places, and the resilience of those sacred places as an internal process arising from their existence is referred to as spiritual resilience.

This research explores spiritual resilience as a key factor in identifying the sacred network that constitutes the cultural landscape. The purpose of this study is to determine how and to what extent the concept of spiritual resilience, as embodied by the network of sacred sites, intangible practices, and the sustainable use of natural resources, contributes to and ensures the conservation and sustainable management of the cultural landscape of the Studenica Monastery as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

2. Studenica Monastery: The Hub of the Cultural Landscape

The identification of the cultural landscape around the Studenica Monastery is based on its historical and spiritual resilience—the ability to build and maintain a functional network of sacred buildings and rural settlements in a preserved natural environment, despite difficult historical circumstances. The cultural, historical, and spiritual significance of the monastery is reflected in the spatial formation in which the identity of the Serbian people has been built.

The monastery complex of Studenica, founded by Stefan Nemanja in the late 12th century, functioned as the centre of spiritual and political life in medieval Serbia. The monastery is situated on a hill overlooking the Studenica River and is bordered by the slopes of the Čemerno and Radočelo mountains. The authentic circular urban–architectural whole is dominated by the Church of the Virgin (1183–1196), with a narthex and chapel (13th century) in the centre of the complex. The architectural and artistic synthesis of Romanesque (external decoration) and Byzantine (layout, interior decoration, and frescoes) influences is evident in its design [

33] (

Figure 1).

The Church of the Virgin was constructed as the burial church of its founder, Stefan-Simeon Nemanja (1165/66–1199), who, according to tradition, was tonsured in the Studenica Monastery after relinquishing power to his son. He subsequently led a monastic life as Simeon at the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos, where he passed away. The spiritual–political significance of this event is reflected in the proclamation and transfer of his “miraculous relics” to Studenica, which contributed to the establishment and subsequent spread of the cult of Saint Simeon and the founding of the holy dynasty of Nemanjić. The youngest son of Nemanja, Rastko-Sava Nemanjić (1175–1236), established a political–ideological matrix based on the triad of ruler–monk–saint, thereby ensuring Studenica’s outstanding spiritual and historical significance and its role as a special place in all subsequent centuries [

34].

In addition to the Church of the Virgin, the complex includes several smaller temples. The Church of St Nicholas, dating back to the 13th century, and the archaeological remains of the Church of St John, also from the 13th century, are notable examples of smaller single-nave churches within the complex. The construction of another significant ecclesiastical edifice, dedicated to St Joachim and St Anne, which is popularly referred to as the King’s Church (1313/14), was overseen by Stefan Uroš II Milutin, a prominent member of the holy dynasty and the Serbian king of the Nemanjić dynasty, who would subsequently be canonised [

35]. The church’s frescoes are widely regarded as a pinnacle of Serbian medieval mural painting. Excavations of the monastery buildings have revealed a chapel dedicated to St Demetrius [

36].

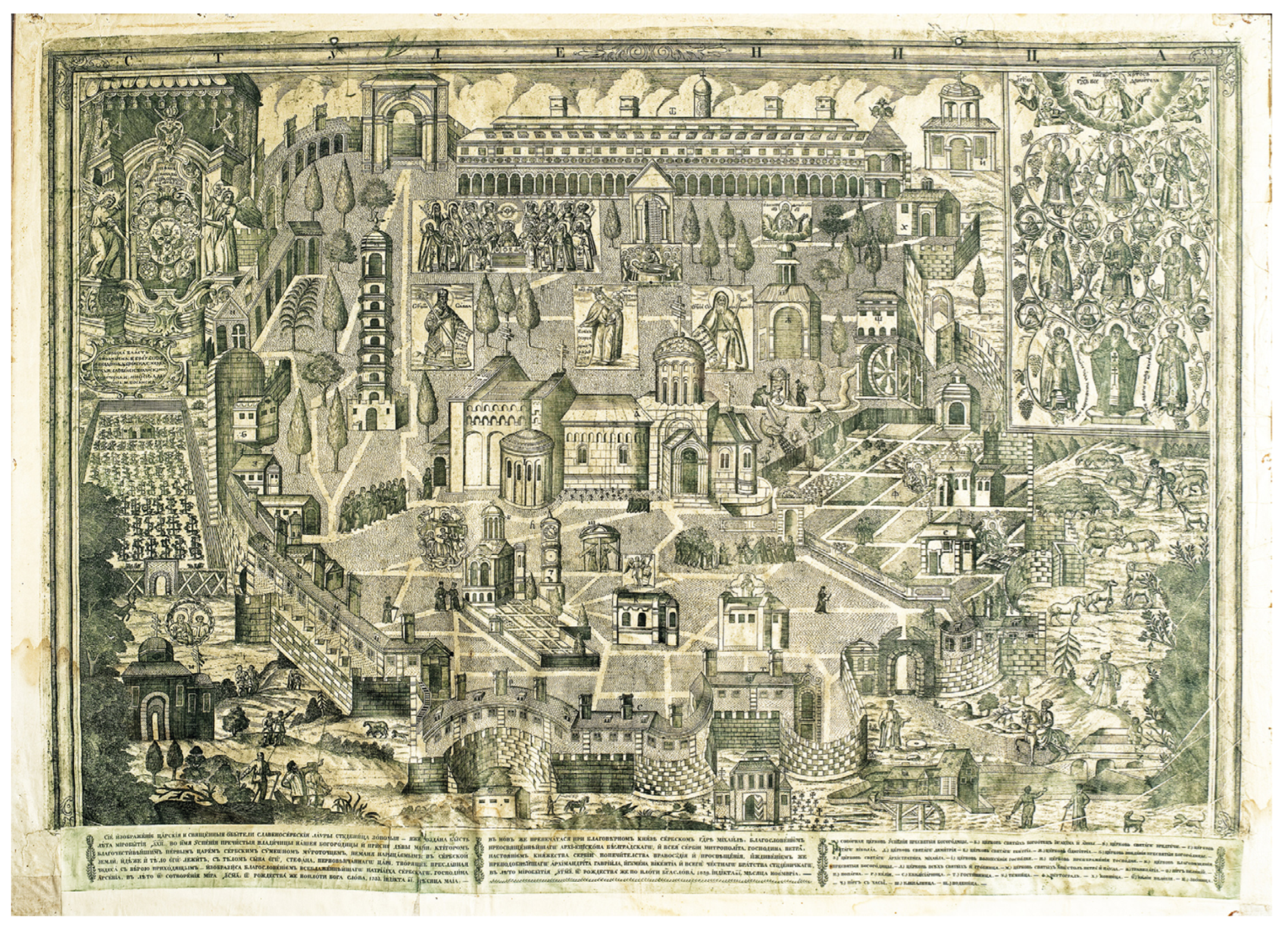

The copper engraving, which was made in 1733 and which depicts the Studenica Monastery, has been well preserved [

37]. The monastery is represented in the engraving as a complex architectural whole. This idealised architectural whole includes not only the Church of the Virgin but also thirteen smaller active temples. These include the churches that are preserved to this day. The concentration of churches around the Church of the Virgin in the Studenica complex symbolises the strong Orthodox faith and the religious–political programme of medieval Serbia under the Nemanjić dynasty. These churches, functioning as satellites around the central temple, attest to the continuity of religious practice and materiality that endured even following the Ottoman conquests at the close of the 14th century. Despite the resilience of Studenica during the Ottoman period, the medieval structures of monastic life and worship continued to suffer until the beginning of the 19th century. That period saw significant damage to the Church of the Virgin in one of the most serious fires and devastations and a brief interruption to liturgical life [

38]. Following the emancipation of Serbia from Ottoman domination in 1833, the monastery underwent significant restoration, with the initial works on the Church of the Virgin commencing in 1839 [

39]. The monastery’s monastic community has maintained continuous existence for nearly 840 years, despite facing formidable historical challenges. This exceptional resilience and the continuity of spiritual life serve to underscore the monastery’s status as a preeminent exemplar of Serbia’s medieval heritage, thereby testifying to its seminal role in shaping the national and religious identity of the Serbian people.

2.1. Protection, Conservation, and Management

The Studenica Monastery was placed under state protection in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War in 1947, and in 1979, following years of scientific research and conservation work, it was declared a cultural monument of outstanding value [

40] (

Figure 2).

In 1986, the monastery was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, thereby confirming its outstanding value. The inscription was made according to the criteria (i, ii, iv, vi) [

41], with particular emphasis on its medieval values from the time of the Nemanjić dynasty. The authenticity of the architectural–urban composition of the monastery, the artistic and aesthetic values of its architecture and sculpture, the frescoes in the Church of the Virgin, and especially the frescoes in the Church of St Joachim and St Anne are all elements that contribute to its World Heritage status. Following its inscription on the World Heritage List, the immediate surroundings and natural environment of the monastery were defined, forming a buffer zone [

42,

43].

A particular emphasis is placed on the fourth criterion in the evaluation of the Studenica Monastery, which is of paramount importance to this study. Its exceptional value is recognised by its unique “example of a monastery of the Serbian Orthodox Church”, which developed and preserved structures “from the 13th to the 18th centuries”, as well as its “exceptionally significant surroundings” with hermitages, churches, and quarries. The incorporation of this medieval monastery into the framework of the Convention has progressively heightened the awareness of its cultural, historical, and religious continuity, thereby prompting more intensive research into the broader environs of the Studenica Monastery [

42,

44].

In the wider natural landscape, shaped by historical routes, traditional communities, and the hydrological system of the Studenica River, a unique cultural landscape with an extraordinary sacred topography, deeply rooted in the cultural heritage of the Studenica Monastery, has been identified [

45]. This area falls within the geographical confines of the Golija–Studenica Biosphere Reserve, a component of the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves (MAB) [

46], as well as the Golija Nature Park [

47].

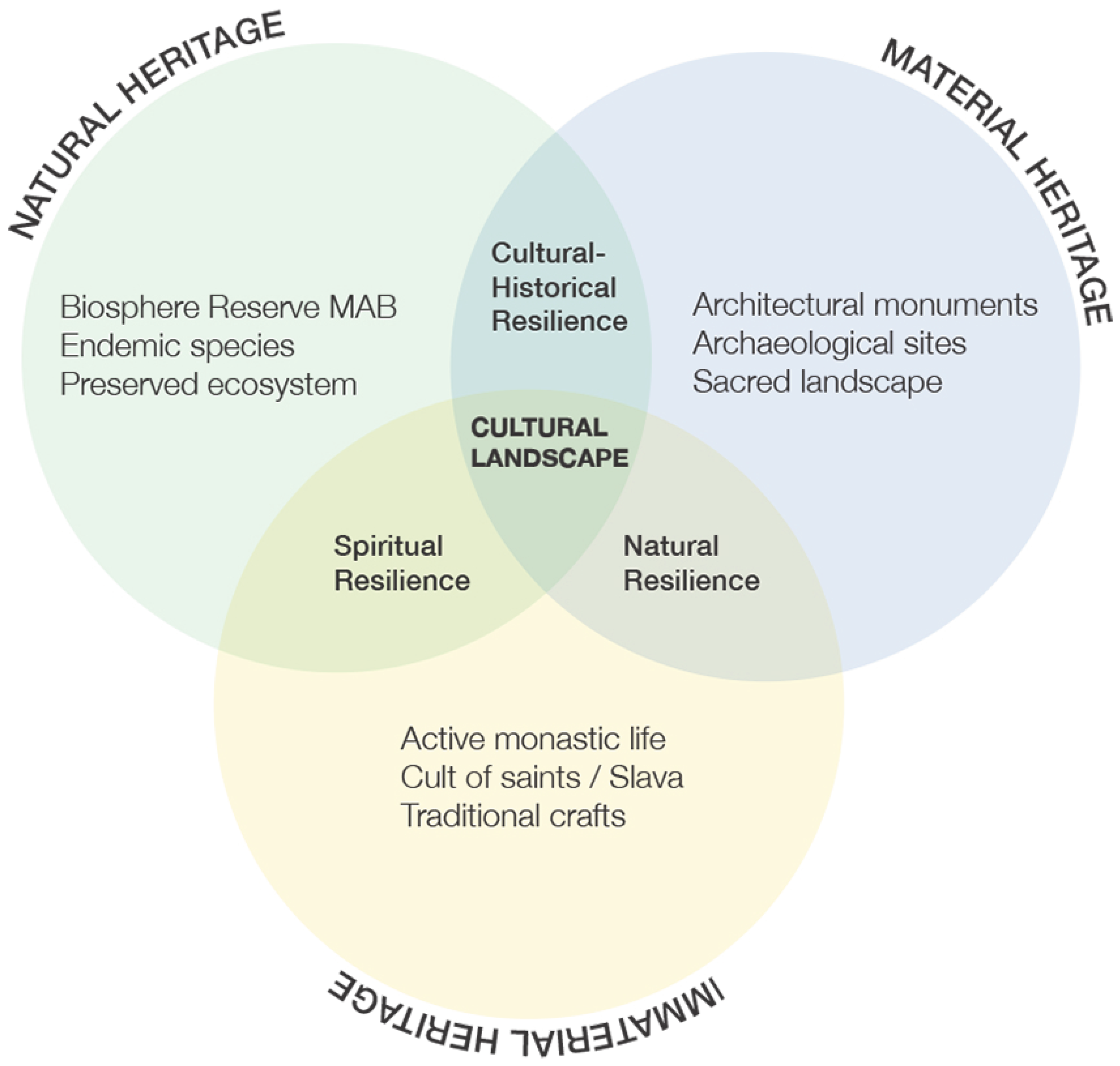

The synergy between the Studenica Monastery and the spatial network of medieval sacred monuments, united by their cultural–historical and spiritual values, the continuity of human communities, and the sustainable use of natural resources, is a key factor that has ensured the resilience of this area over the centuries. The monastery’s profound spiritual resilience has been instrumental in its ability to adapt to historical and social changes while maintaining its indigenous identity and preserving ecological balance. This adaptation has been crucial in establishing the Studenica Monastery Cultural Landscape and developing a strategic model for sustainable management. The Studenica Monastery and its network of cultural and historical heritage represent a system of resilience, adaptation, and survival, as evidenced by numerous historical challenges over the centuries.

In the course of the development of the Special Purpose Spatial Plan for Studenica and the Management Plan for the Studenica Monastery, the cultural landscape was identified as an integral system of material, immaterial, cultural, natural, and spiritual values, the identity of which results from the dynamic interaction of its natural, cultural, and spiritual features [

48].

2.2. The Aesthetic Level of the Cultural Landscape

The aesthetic level of the cultural landscape from an environmental perspective integrates influences from the natural, built, and social environments, which are interrelated [

49]. This results in the resilience of the wider environment of the Studenica Monastery, which operates at several levels: the technical level (physical elements: sacred buildings, designed landscapes, infrastructure), the social level (the adaptability of individuals and populations to survive in a given space), the economic level (the capacity of the local economy to reorganise and innovate), and the management level (the capacity of relevant institutions to implement plans, regulations, and policies for protection and conservation).

The environmentalist aesthetic approach contributes to a multifaceted understanding of the sacred landscape as a subset of the cultural landscape. The integration of elements of cultural heritage, including but not limited to architecture and artistic creations, in conjunction with the natural environment (which may be considered “natural forms of heritage”) has been demonstrated to affect the senses, thereby combining with social, spiritual, and cognitive components of subjective aesthetic experience [

49] (pp. 92–93).

This concept encompasses a synaesthetic experience of the environment, as defined by Berleant. The environment is defined as a comprehensive perceptual system, incorporating factors such as space, mass, volume, time, movement, colour, light, smell, sound, tactility, kinaesthesia, pattern, order, and meaning [

50]. It is imperative to underscore that, in acknowledging the significance of World Heritage cultural landscapes, their visual attributes are but one facet of considerable importance. Rather, they are intrinsically linked to meanings that may be related to complex social, cultural, and economic systems or processes or associations [

51].

In the wider area encompassing the Studenica Monastery, there is evidence of a centuries-long resilience in the aesthetic–sacred experience. That finding indicates that the locale has effectively maintained its aesthetic and spiritual value over the centuries, manifesting in a multisensory encounter with the sacred landscape. That aesthetic experience melds the sensory experience of the environment (comprising historical, cultural, and natural components) with our subjective understanding of cultural and historical narratives. According to Saito’s theory, aesthetic appreciation is inherently linked to the aesthetic object [

52,

53], signifying that our perception of this space is inextricably tied to the objects that constitute it, such as the monastery and the natural surroundings. It is imperative to acknowledge the significance of intangible aspects, including beliefs, myths, customs, and folklore, in shaping our subjective knowledge and experience of this space [

54].

2.3. Objective and Hypothesis

The primary purpose of the present investigation is to emphasise the significance of the concept of spiritual resilience, which refers to the capacity of sacred places to withstand historical and social transformations by virtue of the network of sacred buildings, unaltered religious practices, and the authentic utilisation of natural resources over the course of centuries. This concept of resilience is closely associated with the aesthetic quality of the cultural landscape, which integrates influences from the natural, built, and social environments, thereby contributing to the resilience of the broader environment of the Studenica Monastery.

The aesthetic level of the cultural landscape, which incorporates a synaesthetic experience of the environment, contributes to a multifaceted understanding of the sacred landscape as a subset of the cultural landscape. The integration of elements of cultural heritage, including but not limited to architecture and artistic creations, in conjunction with the natural environment, has been demonstrated to affect the senses and combines with social, spiritual, and cognitive components of the subjective aesthetic experience.

The purpose of this paper is to introduce and explore, both theoretically and practically, the concept of spiritual resilience as a key aspect of cultural heritage conservation, using the example of the sacred network that has developed and endured thanks to the Studenica Monastery. The research shows that spiritual resilience—as a dynamic process linking material heritage (architecture, art), immaterial practices (monastic life, liturgy, traditional customs), and a sustainable use of natural resources—enables the long-term adaptation, identity preservation, and stability of the cultural landscape despite historical challenges. By analysing the network of sacred sites around Studenica, the study highlights that spiritual resilience is not only an internal strength of the community but also a mechanism that enables sustainable spatial management, biodiversity conservation, and the transmission of cultural values, thus establishing a model applicable to other UNESCO sites worldwide.

The study emphasises the universal importance of sacred places as key points that enable the historical, spiritual, and natural resilience of the area. By examining the case study of the Studenica Monastery and its associated sacred monuments, this study demonstrates how the synergy between spiritual practices, cultural heritage, and the sustainable utilisation of natural resources contributes to the preservation of a communal identity and ecological equilibrium over time. The practical implementation of the model for spatial planning and the management of the Studenica Monastery constitutes a valuable real-world application of the aforementioned concept.

3. Materials and Methods

The present paper investigates the role of the Studenica Monastery in the formation of a unique cultural landscape, characterised by a network of sacred buildings. The designation of World Heritage Site has prompted a comprehensive examination of the broader area of influence through the identification of natural, cultural, and spiritual features. The concept of spiritual resilience, manifesting as a network of churches integrated into the natural environment, has facilitated the development of an integrated model for the sustainable management of the Studenica Monastery landscape.

3.1. Natural Features

The area’s predominant geographical feature is the watershed of the mountainous Studenica River, which is situated in southwestern Serbia, demarcating the transitional zone between the Stari Vlah plateau and the Ibar Valley. It extends between 20°16′–20°38′ east longitude and 43°16′–43°35′ north latitude, originating on the northern slopes of Golija Mountain at an altitude of approximately 1615 metres. The Studenica watershed, being the longest left tributary of the Ibar River, covers an area of 582 km

2, with a river length of 60.5 km, a stream development coefficient of 1.97, a river network density of 1302 m/km

2, and a total tributary length of 225.3 km. The water richness of the relatively small Studenica River watershed amounts to 230 × 10

6 m

3. The river’s substantial arc traverses the mountainous expanse of the Radočelo and Čemerno mountains, distinguished by a striking gorge that has been sculpted through the landscape by erosion. The left bank of the Studenica River is fed by the Brusnica, Bradulicka, Grajićka, and Savošnica rivers, while the right bank is fed by the Samokovska, Izubra, Sklapljavec, Brebina, and Kraljska rivers [

55].

The area’s geological heritage is exemplified by unusual and attractive relief forms with numerous water features, including springs, mountain streams, and marsh lakes. Among these features, the picturesque area of the Izubra tributary of the Studenica River is particularly noteworthy, as it comprises three waterfalls with a total height of 20 metres. The Radočelo area (42°35′ N, 21°45′ E) is notable for its complex geodiversity, characterised by the predominance of metamorphic rocks (greenish-black serpentinite schists with a layer thickness of 0.5–3 m), magmatic intrusions (Paleozoic granitoids), and sedimentary formations (marbles with a fine-grained texture of less than 2 mm). The mountain massif is part of the Hercynian orogenic belts, with pronounced karst processes on the plateau. On the eastern and northeastern flanks of Radočelo, there is a marble belt that is economically viable (density 2.6–2.8 g/cm

3, compressive strength 80–110 MPa), with the settlements of Vrh, Dolac, and Brezova and their outlying settlements [

56]. Over time, stone quarrying settlements have formed on the trace of the rock massif, in hard-to-reach places, which today help orient marble deposits. The aforementioned hamlets are stone quarrying settlements, where the tradition of stone extraction and processing has been present for centuries (

Table 1). The finest varieties of fine-grained marble are extracted from the Godovićki quarries, which are located in the northeastern part of Krivača (elevation 1280–1380 m a.s.l.) and contain deposits in Draškovački Valley. The following active quarries have limited exploitation: Godovićki Quarry, Stari Quarry, and Sečin Quarry [

57].

The historical significance of these sites has been confirmed through archaeological investigations of marble exploitation. The relief forms, rock masses, and soil composition encountered at the site selected for the construction of the monastery likely exerted a primary influence on the selection of the area and location as well as on the architectural concept of shaping and building the monastic settlement, especially the Church of the Virgin [

36] (p. 31). Historical sources corroborate the selection of an unoccupied site for the construction of the monastery and the Church of the Virgin in Studenica during the 12th century [

58].

The utilisation of Studenica marble for the architectural stone, plastic, and ornamental decoration of churches was a recurring feature in the endowments bestowed by Serbian kings during the medieval period [

59,

60]. The continuous utilisation of Studenica marble since the Middle Ages attests to the reliability of the resource and the durability of its exploitation while also underscoring the necessity for its conservation.

The climatic characteristics are determined by the geographical position, the diversity of the relief, the altitude, the vegetation, and the direction of the Studenica River Valley, which influence the diversity of the climate identified through three climatic regions: a valley with continental, transitional, and mountainous zones, where subhumid climates prevail. The average annual temperature ranges from 5.1 to 9.5 °C, while extreme temperatures range from −20 to 38 °C, and the average annual precipitation is between 550 and 650 mm [

55] (pp. 81–83).

The biodiversity of this area is preserved within the Golija–Studenica Biosphere Reserve, an internationally recognised nature reserve since 2001 under the UNESCO MAB programme, covering an area of 54,302 ha [

46]. The designation for access to the aforementioned biosphere reserve network was based on the fulfilment of stringent criteria, encompassing protected areas, ecosystems, and species, varying degrees of human intervention, the implementation of sustainable development principles, the achievement of a balance between the sustainable utilisation of natural potential and the protection of biodiversity, and research, education, and the exchange of information in the domain of environmental protection [

61]. A salient characteristic of this region is the prevalence of forest cover. Spruce, pine, and beech trees are present at higher elevations, while beech forests are predominant in lower areas, with some regions exhibiting characteristics of primeval forests. Amongst the preserved natural rarities, the refugial habitats of Heldreich’s maple (

Acer heldreichii) [

62], a relict and endemic woody species, are of particular note. Local endemics include

Pancicia Serbica and

Thimus adamovicii. Meadows and pastures are mosaically distributed across the area and, depending on the elevation, have a hilly, submontane, and mountainous character, with 15 meadow phytocenoses documented [

63].

The floristic biodiversity of this area comprises about 900 taxa of plant life (729 species of vascular fungi, 40 species of moss, 117 species and varieties of algae). The Golija mountain massif, renowned for its high biological diversity, is home to 45 bird species classified as natural rarities as well as 22 species of indigenous mammals and domestic animals and plant cultures [

64].

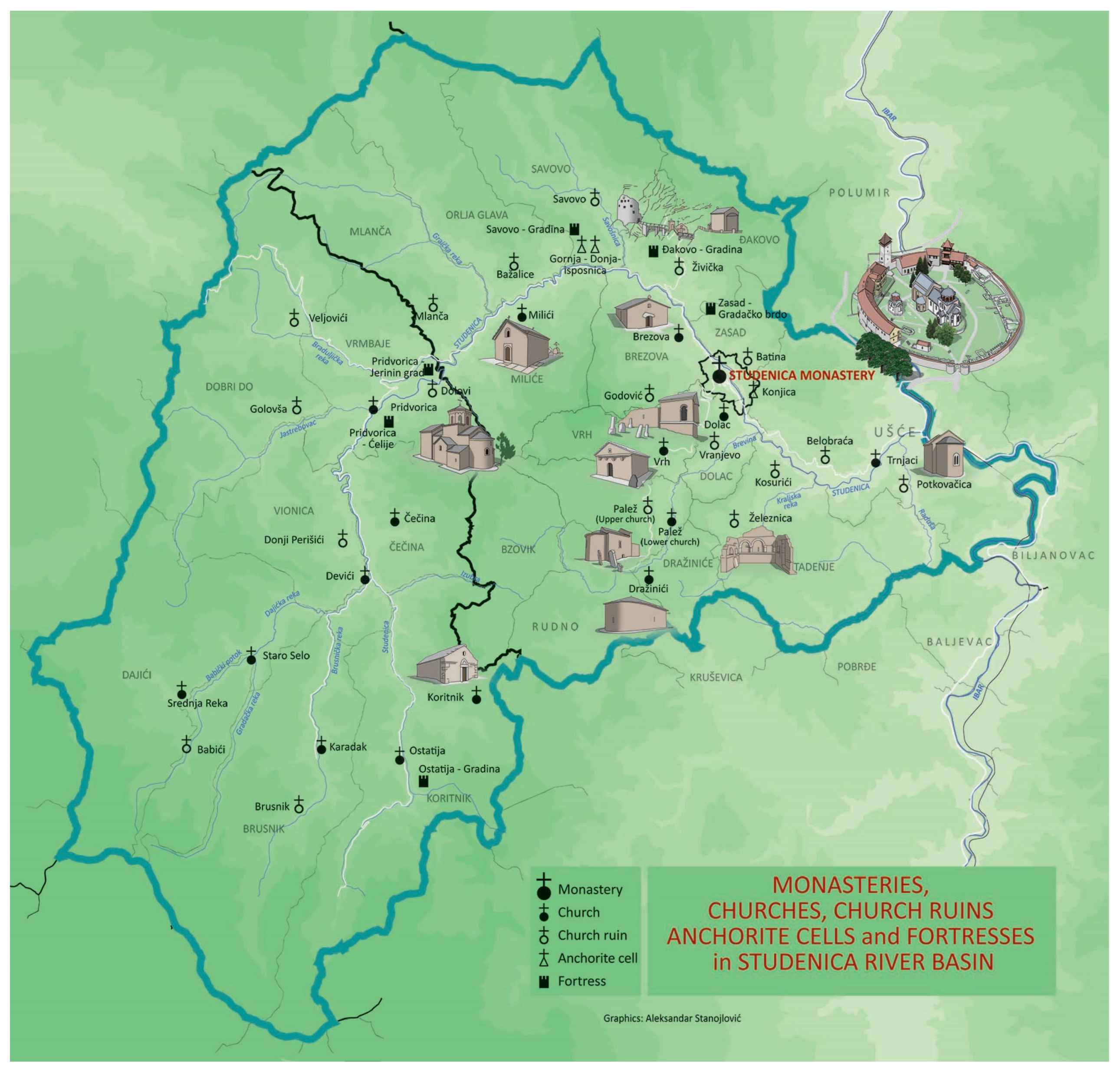

The entire area is characterised by rural settlements of a dispersed type. The population is tied to the rural area, using natural resources through ancient stone quarrying crafts, traditional forms of land cultivation, livestock breeding, and forestry. In recent decades, there has been an increase in the popularity of rural tourism. Recent research has revealed that no land-use changes have been observed since the designation of the biosphere reserve [

65] (

Figure 3). The designation of the biosphere reserve, in conjunction with the broader natural environment encompassing the Studenica Monastery, presents a plethora of opportunities for the advancement of local communities through alternative forms of tourism and organic agriculture and livestock farming. These activities, when coupled with the preservation of natural ecosystems, have the potential to foster a sustainable economic development within the local community.

3.2. Cultural and Historical Features

The area surrounding the Studenica River has seen significant development in the local environment, with the presence of the Studenica Monastery acting as a catalyst for this growth. The monastery has been a prominent spiritual, cultural, and economic centre for many years, and the material evidence of this can be seen in the area to this day. This evolution is evident in the formation of rural settlements, the presence of numerous churches, and the preservation or visibility of architectural remains. The area is distinguished by unique marble tombstones in old cemeteries, remnants of medieval fortifications, and buildings of vernacular architecture. Notably, the marble and schist quarries have played a pivotal role in shaping the sacred and profane architecture of the region, underscoring the area’s rich natural resource base. It is challenging to identify a location where traces of medieval ecclesiastical architecture or tombstones crafted from the renowned Rodočelo marble are absent. There are several quarry sites, with the largest and most productive being the Godovićki Quarry, the Stari Quarry, and the Sečin Quarry. It is hypothesised that the Church of the Virgin was constructed using the largest quantity of marble extracted from these locations [

56]. The close proximity of marble quarries in the vicinity of the Studenica Monastery stands as a testament to the symbiotic relationship between humanity and the natural environment. The relief forms, rock masses, and soil composition encountered at the site selected for the monastery’s construction exerted a significant influence on the selection of the area and location as well as on the architectural concept of shaping and building the monastic settlement, particularly the Church of the Virgin [

36] (p. 101).

The stone quarrying craft is a characteristic feature of many villages in the vicinity. The tradition of stone extraction in this area can be traced back centuries. From ancient times, the area has been renowned for the production of marble tombstones, which were exported to distant regions in caravans. That craft has been meticulously transmitted through successive generations, with numerous families being distinguished by their expertise in stone quarrying [

66]. In the vicinity of the Studenica Monastery, there is a significant concentration of single-nave rural churches, whose construction continuity can be traced from the 13th to the late 17th century. These churches are distinguished by their antiquity as well as their architectural, painting, and ambient characteristics. The medieval monasteries, hermitages, and churches that have been preserved stand as a testament to the historical continuity and spirituality of the Serbian people [

57]. The area surrounding the monastery, in particular, boasts a unique combination of natural beauty, centuries-old human creations, and living traditions.

The environs of the Studenica Monastery, in particular, stand out as a remarkable amalgamation of natural beauty, millennial human creations, and living traditions. In addition to ancient settlements and cemeteries, churches and hermitages, remnants of fortifications and quarries, and preserved traces of vernacular architecture contribute to the richness of this area.

3.3. The Process of Valorising Cultural Heritage

From the first researchers of medieval antiquities in the 19th century to the present, the process of valuing cultural heritage in this area has continued [

67]. The preserved churches in the vicinity of the Studenica Monastery were designated as immovable cultural goods following the establishment of institutions dedicated to the protection of cultural monuments in the aftermath of World War II (

Table 2). Traditional reconnaissance of the area identified other sacred buildings in the form of archaeological traces. Research and conservation work were conducted at several locations, contributing to the increased significance and renewed liturgical function of those sites [

68].

The overview of the cultural–historical monuments in this area highlights the richness of the cultural heritage by type and significance. A special emphasis is placed on monasteries, hermitages, churches, and cemeteries, which form a strong network of sacred places (

Table 3). In order to gain a more profound understanding of their role, in addition to the Studenica Monastery, three typologies of sacred architecture were selected.

3.3.1. Hermitages: Spirit of the Place and Spirituality

From the early establishment of Christian monastic communities in the East, various forms of monastic life developed alongside organised settlements of monk communities—coenobitic communities to smaller communities structured for higher individual forms of asceticism. Such households consisted of anchoritic cells formed in the surroundings of the parent monastery in so-called deserts [

69]. The Studenica Monastery also had such habitats in its environs.

The Hermitage of St Sava, located on a natural concave plateau near the edge of a steep cliff, about ten kilometres from Studenica Monastery in the village of Savovo, represents a mystical place directly connected with the influence of the monastery. The location of this hermitage, formed on a natural plateau, is determined by a series of geomorphological, spatial, and microclimatic characteristics. Access to the hermitage is via a footpath from the village of Savovo, where another Lower Hermitage is also located, as well as from the western side from the village of Bažala.

The hermitage is situated in a mountainous region, in the rock itself, several hundred metres above the Studenica River. It is a response to the demands of desert asceticism, seeking the highest ascetic ideal (

Figure 4). According to tradition, the construction of the Hermitage of St Sava is attributed to the youngest son of Stefan Nemanja, Prince Rastko, a monk, ascetic, and Serbian enlightener, and later a saint, St Sava, who is regarded as one of the most significant figures in medieval Serbian history [

70]. Upon his arrival as a monk from Mount Athos (Greece) to Studenica in 1208, Sava sought to “transfer every model of Mount Athos to his homeland through coenobitic monasteries, hegumenates, and sketes” [

71].

In harmony with the encountered natural morphology of a distinctly picturesque character, significant sun exposure, a depression following the terrain configuration, southeast orientation, and limited spatial possibilities, a vertically dominant dwelling and contemplation tower was positioned. In symbolic representation of the contact between earth and heaven, a multi-storey isichastirion similar to the holy mountain was formed above a natural water spring, covered by a rocky plateau [

72]. In the immediate vicinity, on another natural extension, a small single-nave church dedicated to St George was constructed, painted in the 16th century. Collectively, these architectural elements, inclusive of two caves, coalesce to create a unified spatial entity that is both functionally and symbolically coherent. This exceptional architectural achievement, with its pronounced integration into the natural landscape, reflects the extraordinary skill of the builders in creating a particularly ascetic habitat and in expressing the spirit of the place through “a synthesis of physical and spiritual elements that give meaning, value, emotion, and mystery to the place” [

9].

3.3.2. Sacred Network of Churches Around the Studenica Monastery

The present study sets out to explore the origin, development, and functioning of the Studenica Monastery through religious, cultural, and artistic practices. The analysis will demonstrate how the supernatural, divine dimension was realised in a dynamic relationship with the surrounding landscape. The numerous churches that emerged within the monastic complex represent a unique example of the “City of God on Earth”, situated in an untouched natural environment, which, over time, was settled, and villages were marked by local places of worship. The most renowned of these is the copper engraving of 1733, which portrays a vista of the monastery as a “city” that, in addition to the central Church of the Virgin, comprises a network of 13 smaller churches, of which a number have been preserved to the present day (

Figure 5). The urban structure of the monastery is complemented by a cemetery, gardens, and landscape sequences that depict genre scenes of monastic life as well as the everyday life of laypeople outside the walls.

The entire monastic settlement is under the protection of representations of the Virgin, St Simeon, and St Sava and saints from the Nemanjić dynasty. The copper engraving visualises the concept of continuity between the heavenly and earthly vision of an imaginary “kingdom”, thereby underscoring the significance of Studenica throughout the centuries [

37].

This idealised representation demonstrates that the Studenica Monastery played a pivotal role in preserving Christian identity, particularly evident in the construction of rural churches in its environs. These churches, by virtue of their architectural characteristics, bear a resemblance to the smaller churches within the monastic complex, such as the Church of St Nicholas and St John. The churches were constructed as single-nave churches, with bases featuring attached arches that support the vault, covered with double-pitched roofs made of stone slabs, without domes—a common feature of Eastern Christianity. The interiors of these churches were painted, and the artistic value of the wall paintings can still be seen today in the Church of St Nicholas in Palež (14th century), the Church of the Virgin in Vrh (17th century), the Church of St Alexius (17th century), and in the churches of the Studenica hermitages (

Figure 6).

The exterior appearance of these churches is characterised by the use of broken and dressed stone, often including secondarily used marble tombstones. Examples of entrance portals and altar windows crafted from Studenica marble include those found in the Church of St Nicholas in Ušće, dating back to the 14th century, and the Church of the Virgin in Dolac, dating back to the 13th or 15th century [

57].

The artistic output of the monastery declined during the Ottoman occupation of Serbia (15th–19th centuries) due to the suffering it endured, yet the continuity of monastic life was never completely interrupted. In the surrounding villages, whose inhabitants were often tied to the monastery’s economy, churches were constructed without visible Christian symbols, thereby testifying to the resilience and survival of the Christian population. Despite the impediments imposed on artistic creation, the resilience of the artistic community, both the clergy and laity, ensured the continuity of artistic expression as a testament to their spiritual and national survival [

73].

With great sacrifice and perseverance, less affluent patrons and groups of donors constructed modest rural churches in rural landscapes. In the Studenica region, temples were restored and painted soon after the temporary Turkish conquests in the 15th century, especially during the 16th and 17th centuries [

66]. Despite the destruction of these edifices, the churchyards themselves continued to be regarded as sites of spiritual and memorial significance (

Figure 7).

Despite significant material losses, the spiritual strength and sense of obligation to preserve the Studenica Monastery remained unwavering. The practice of liturgical life continued in the local churches, while major religious holidays were celebrated at the Studenica Monastery.

3.4. Spiritual Features

Throughout the Eastern Orthodox world, monasteries became nurseries of spirituality. In founding the Monastery of Studenica and building the Church of the Holy Mother of God, dedicated to the Virgin Evergetis, Stefan Nemanja was guided by the idea of symbolically repeating the Old Testament pattern of building a sanctuary. Just as the Ark of the Covenant was placed in the Tabernacle of Testimony, the dedication of the church to the Virgin, who in theological writings was metaphorically equated with the Ark of the Covenant, was intended to indicate a place of divine presence and to present the temple as a “new tabernacle” [

74].

A significant moment in the history of the monastery was the arrival of the body of Simeon Nemanja from the Hilandar Monastery on Mount Athos and its placement in a tomb from which myrrh flowed. The cult of St Simeon the Myrrh-bearing developed around the tomb, which ensured the monastery’s status as a “holy seat” of the highest rank. The tomb of St Simeon became the most important place of pilgrimage, where the faithful and the sick came to be healed. In memory of the ascetic, a feast day of Saint Simeon was established, and in the 14th century, a miraculous vine emerged from his tomb, according to a historical inscription on a pilaster (1482/1483) [

75]. The tomb of the founder of the dynasty and of the saint made possible a religious experience that could only be experienced in situ, in a geographically recognisable place firmly linked to the land. Other members of the Nemanjić dynasty were also buried in the church, including his wife Ana, tonsured as Anastasija, whose tomb carried important ideological messages [

76]

Stefan the First-Crowned (later monk Simon and the Saint King), a son of Stefan Nemanja and Ana-Anastasija, was the first crowned king of the Nemanjić dynasty. At first, he was buried in the monastery of Studenica, but later, his relics were transferred to his foundation, the monastery of Žiča (13th century), where they reached the ritual peak of their cult. After that, the relics were transferred again to the Sopoćani Monastery (13th century), which has a long history of translations aimed at protecting them and strengthening their spiritual significance.

During the Ottoman rule, the cult of the Saint King did not fade. According to historical sources, his “undisturbed” relics were kept in Sopoćani until the end of the 17th century, when they were transferred to the monastery of Crna Reka (1687) and from there to Studenica (1704). During the 18th century, the coffin with the relics followed the Serbian people into exile during the wars but returned to the Studenica Monastery in times of peace, where it remains today and represents the most valuable relics of the Studenica Monastery [

77].

The historical narrative about the third son of Stefan Nemanja, Prince Rastko, who was tonsured in Hilandar as a young man and received the name Sava, presents him as the architect of the complex concept of the sacred foundation of the medieval Serbian state and the realisation of the ideal of the holy Nemanjić dynasty. As the first Serbian archbishop and still celebrated as the enlightener of the Serbian people, St Sava is the author of the Typikon—a monastic constitution that still regulates life in the Studenica Monastery [

58]. This constitution also regulated the functioning of the monastery hospital, which influenced the creation of “monastic traditions” about healings, St Sava as a physician, and other folk traditions in which hagiographic, historiographic, and mythopoetic threads of written and oral tradition intertwine.

The complex structure of traditions about Saint Sava survives thanks to the basic identity matrix and deep cultural memory of the Serbian people. These traditions are reflected in the belief in the healing power of water and the tradition of pilgrimage to the springs of Sava, which is a special heritage of the Studenica complex [

78]. In the vicinity of the monastery, there are several springs bearing the name of Sava. A number of toponyms in the area are linked to his name: the village of Savovo, the Savošnica River, the Sava Cliff, the Sava Spring near the Lower Hermitage, the Sava Spring in the Upper Hermitage, and the Sava Spring next to the monastery complex. The belief in the healing power of water and the traditions of miraculous cures and healings create a unique toponymy of the Sava springs throughout Serbia.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Studenica Monastery became a model for the construction and painting of other monasteries. St Simeon and St Sava became symbols of the Serbian Church and monasticism and advocates of the Serbian people, especially emphasised after the Ottoman conquests. On the copper engravings of the Church of the Holy Mother of God from the 18th century, the figures of St Simeon and St Sava are depicted as protectors.

In the Studenica Monastery, a year-round spiritual calendar was established with celebrations of the seven most important saints: St Sava, abbot of the Studenica Monastery and the first Serbian archbishop (27 January/14 January according to the Julian calendar); St Simeon the Myrrh-spinner, founder and monk of the Studenica Monastery (26 February/13 February according to the Julian calendar); St Anastasia (4 July/21 June according to the Julian calendar); the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the feast of St Catherine, and the feast of St Anne: The Assumption of the Most Holy Mother of God—the Great Lady (28 August/15 August according to the Julian calendar); the feast of Saint Joachim and Saint Anne, the Righteous Saints (22 September/9 September according to the Julian calendar); the feast of Saint Simon the Monk (7 October/24 September according to the Julian calendar); and the feast of Saint Milutin, the Founder of the King’s Church (12 November/30 October according to the Julian calendar) [

45].

The celebration of the family patron saint, Slava, is a unique Serbian custom that integrates spiritual, social, and traditional aspects of life. The celebration is linked to the day of the saint who is the protector of the family or the church. Different saints serve as patrons of families, and families celebrate their identity and spiritual connection with the saint [

79]. Slava is regarded as the most significant annual celebration for Orthodox Christian adherents, ranking immediately after Easter and Christmas. It is a distinctive illustration of the endurance of the intangible religious culture of the Serbian people, which has persisted from the Middle Ages to the present day. Across the country, Serbian families observe this sacred day, which serves not only as a testament to their religious convictions but also as a confirmation of the profound significance accorded to the cult of ancestors, the identity of each family, and the collective identity of the Orthodox community. It is celebrated in the home of the head of the family, the oldest male member, and is traditionally passed down from father to son after the father’s death. This holiday exemplifies an exceptional manifestation of social and spiritual resilience, preserved by Serbian families and communities (

Figure 8).

The feast of Slava was included in the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014, confirming its importance for humanity. The rituals include the preparation of symbolic elements, such as the Slava cake decorated with Christian symbols and boiled wheat for commemoration, consecrated wine to be poured over the cut cross-shaped cake, and incense to perform a bloodless ritual sacrifice [

80]. It is a living document of Serbian spirituality, linking the past with the present. This custom has been preserved in its authentic form to this day, which is why it has been included in the UNESCO list.

In addition to spiritual celebrations, the cultural calendar of the monastery includes decades of cultural manifestations—art colonies, choir festivals, and other artistic programmes, which manifest a number of the immaterial values of the Studenica Monastery.

The wider area around the Studenica Monastery represents a unique sacred space, where natural, cultural, and spiritual values have been preserved in their authenticity and recognised by UNESCO. The natural landscape, enriched with medieval architectural monuments, is complemented by a rich spiritual heritage, including traditional spiritual celebrations and traditions. Although the Studenica Monastery, with its authentic monastic way of life, preserved from the Middle Ages to the present day, is not included in the Register of Intangible Heritage, the celebration of Slava, which is an important part of spiritual life in Serbia, has been included in the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Cultural values, such as preserved monasteries, hermitages, and churches, contribute to the preservation of a vibrant cultural and spiritual identity. Each of these areas, individually and through interaction, has contributed to the identification of this region as an exceptionally significant cultural/sacred landscape, whose unified interactive protection and controlled development are envisaged through the instruments of spatial planning and sustainable development (Spatial Plan for Special Purposes of the Studenica Monastery and Management Plan).

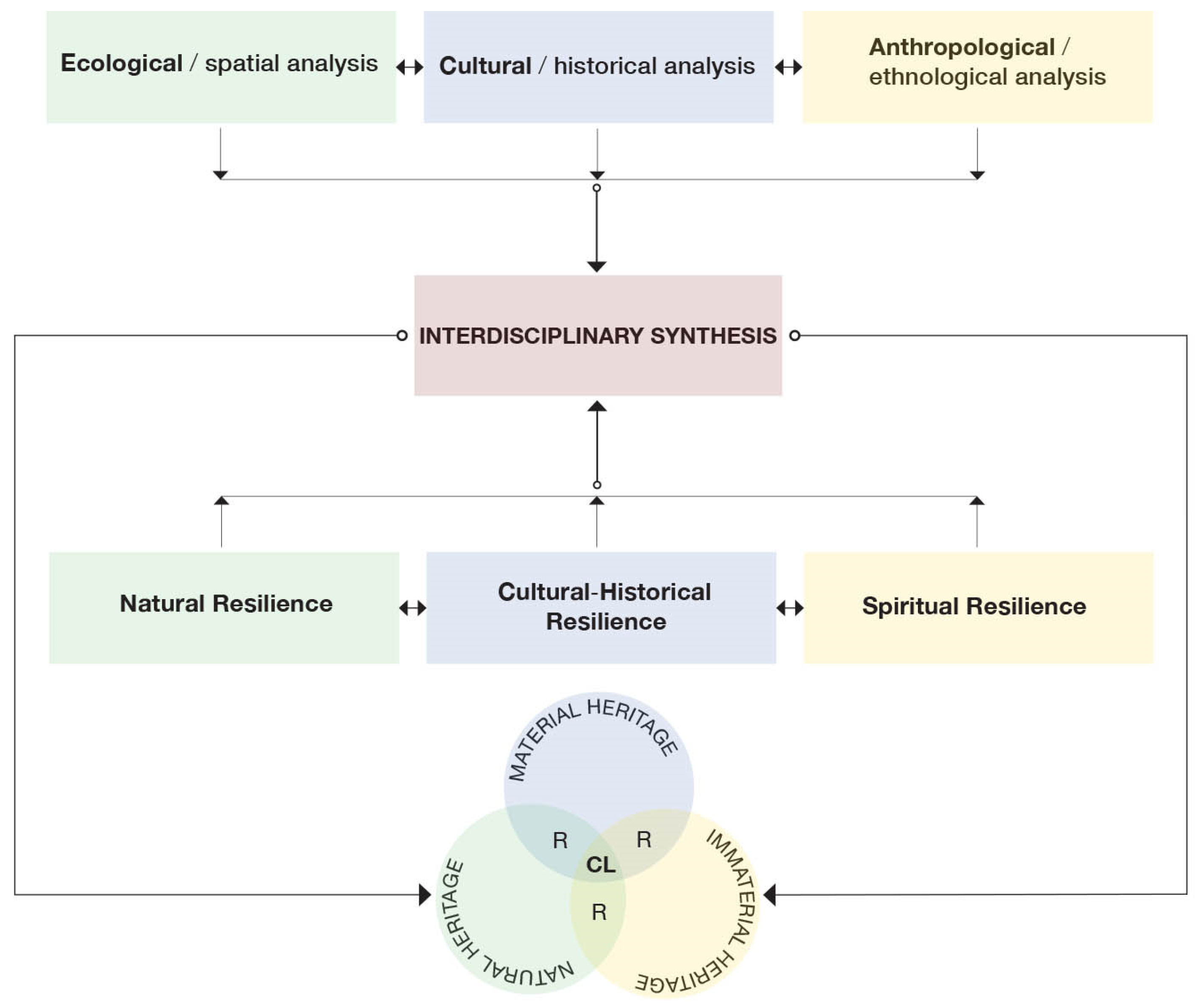

3.5. Interdisciplinary Methodological Approach and the Resilience Scope of the Sacred Landscape

The methodological framework for the study of the cultural/sacred landscape of the Studenica Monastery and the creation of a model for its protection and management, integrated into the spatial planning policy, has been defined through several phases and methods, combining interdisciplinary approaches: empirical research based on interdisciplinary analytical methods that examine the indicators of resilience that influence the synergy of natural, cultural, and spiritual heritage elements that make up the sacred landscape of the Studenica Monastery and its wider environment.

The research methodology is oriented towards an integrative approach that combines natural, cultural, and spiritual aspects in the formation of the sacred landscape around the Studenica Monastery. It has been carried out through a multi-stage methodological approach that includes a tripartite matrix: ecological/spatial analysis, cultural–historical analysis, and anthropological–ethnological analysis. This approach allows for an interdisciplinary synthesis that leads to the identification and understanding of the resilience of this area, where the dimension of spirituality is structurally unifying, allowing for the preservation of the authenticity and universal values of the area.

In the first phase of the research, the method of deduction was applied in order to identify, valorise, compare, and analytically systematise the concept of cultural landscape in the context of the international conventions, recommendations, and policies of UNESCO. This involved analysing the content of available theoretical material and field data. Based on the identification of key aspects that define the Studenica Monastery as a cultural, political, and spiritual centre from the 12th century, the aspects considered are related to the location of the monastery in an untouched natural environment, which influenced the development of human settlements in the vicinity, the valorisation, and the inscription of the monastery on the UNESCO World Heritage List and is a key factor in setting the conceptual framework for the research.

The evaluation of the definition of cultural landscape and the guidelines for the management of a World Heritage Site (according to the UNESCO conventions), as well as a review of key documents and theoretical frameworks that have changed and shaped the approach to cultural heritage over the past decades, provided the basis for the subsequent steps.

Focusing on the Studenica Monastery as the focal point of the area, the second phase of the research was based on the study and collection of data on relevant features of the natural environment (analysis of the state of the Studenica River, autochthonous beech and fir forests, pastures, meadows), cultural–historical features (valorisation of the sacred heritage, construction techniques, artistic styles), and spiritual practices (liturgical rituals, cult of saints, celebrations) that constitute the intangible heritage. Field reconnaissance and spatial analysis were carried out, including GIS viewshed analysis to map visual connections between the monastery and the network of sacred sites as well as overlapping cultural and natural zones (UNESCO World Heritage and the Golija–Studenica Biosphere Reserve).

The cultural–historical analysis included the study of medieval sources, hagiographic texts, and biographies, while the anthropological–ethnological source-based research included interviews with monks, local residents, and craftsmen. Hermeneutic and generic methods, based on the synthesis of data from ecology, historiography, art, and architecture, enabled an interdisciplinary approach that led to the third phase of research—the analysis of resilience indicators through the synergy of natural, cultural, and spiritual factors—and the interdisciplinary synthesis of the results (

Figure 9).

In the fourth and final phase, the synthesis of the results obtained provided a spatial and legal framework for implementing the protection and resilient and sustainable management of the sacred landscape around the Studenica Monastery. The formation of a conceptual matrix for analysing the synergy of natural, cultural, and spiritual heritage as inseparable elements led to the hypothesis: the Studenica Monastery, through its cultural–historical and spiritual values, influenced the formation of a medieval network of sacred places based on community continuity and the sustainable use of natural resources, ensuring the resilience of the area over the centuries, which enabled the recognition of this heritage through the category of cultural landscape.

A structural synthesis was carried out, revealing the natural resilience of the area as well as the impact of historical and social changes that have achieved historical resilience, highlighting in particular the link through spiritual resilience, which has contributed to the preservation of authenticity, integrity, identity, and ecological balance. Based on the results, the fourth phase of the study reaffirmed the spatial, architectural, spiritual, and cultural values of the Studenica Monastery, defined the boundaries of the cultural landscape, and subsequently developed a spatial plan for the Special Protection Area, creating a legal framework for protection, conservation, and sustainable management.

This study explores the possibilities for further change and development, recognising the limitations of the tripartite model of natural, socio-cultural, and anthropological resilience. The concluding notes present, in a concise form, new and important facts discovered during the research, which can be integrated into broader scientific fields, opening up possibilities for further exploration by new generations of researchers in an effort to preserve heritage in its entirety.

4. Results

4.1. Establishing the Cultural Landscape Through a Resilience Approach

The resilience-based approach to defining cultural landscapes emphasises the dynamic interaction between natural features, cultural heritage, and living traditions, demonstrating the ability of the area to adapt while retaining its essential character through centuries of change [

81]. It recognises deep cultural roots that permeate material and intangible meanings related to identity, social relationships, and the sense of sacred places. These deep connections make the landscape resilient to change, which is not necessarily negative. The challenge is to recognise the evolutionary nature of cultural landscapes [

2], where changes over time have contributed to the creation of the landscape in the synergy between people and their environment, shaped by sacred places.

The study of resilience indicators (natural, cultural–historical, and spiritual resilience indicators) revealed a balanced and adaptive context that led to the conservation of natural, ecological, cultural, and essential spiritual values.

4.1.1. Indicators of Natural Resilience in the Studenica Monastery Area

The natural factors recognised as crucial for the conservation of transitional values include geological stability, preserved biodiversity, and the hydrological system, which form the “backbone” of the ecological balance. The preservation of marble deposits and the study of their structure have revealed high values of marble strength (80–110 MPa) and density (2.6–2.8 g/cm

3), indicating that the rock masses are stable in the long term. This fact, together with their historical importance, ensures a limited and sustainable exploitation of the resource without environmental degradation. The hydrological system, characterised by a high density of river networks (1302 m/km

2) and annual runoff (230 × 10

6 m

3), ensures continuous water levels, while gorges (e.g., Radočela) protect the river flow from anthropogenic influences. In addition, the presence of relict species (

Acer heldreichii) and 15 meadow phytocenoses indicate the conservation of the ecosystem, while the great diversity of birds (45 species) and mammals (22 species) is key to adaptation to climate change. The absence of overexploitation of land (according to the UNESCO inscription) indicates a successful synthesis of conservation and economically sustainable development, with growth in rural tourism. An important aspect for future conservation is institutional support: the UNESCO and MAB Biosphere Reserve statuses ensure global standards, while the Management Plan prevents the excessive and inappropriate exploitation of water, forest ecosystems, and other natural resources, as well as stable land use, which has a positive impact on climate change [

82] (

Table 4).

4.1.2. Indicators of Cultural–Historical Resilience in the Studenica Monastery Area

Cultural–historical resilience refers to the ability of communities to adapt and evolve in the face of historical circumstances, drawing on the invaluable nature of cultural heritage embodied in sacred architecture and the continuity of traditions and historical experiences. The importance of cultural and historical factors in shaping resilience is evident. The most important aspects of cultural–historical resilience are recognised through collective memory and identity, where communities draw strength from their history and cultural identity narratives. The transmission of knowledge and traditions from one generation to the next enables the use of cultural heritage to ensure that communities overcome challenges in difficult historical circumstances. In such circumstances, the ability to respond to uncertainty develops, with faith and the religious context of the environment enabling adaptation and the management of change throughout history. This approach to resilience goes beyond individual coping mechanisms and emphasises the significant role of religious practices and the role of sacred places in promoting the resilience of the whole community, where religious and cultural practices have adapted to historical circumstances and enabled the survival of Christian communities.

The results show the existence of a network of 14 preserved churches, including those of the Studenica Monastery, which testify to the ability to preserve and maintain sacred buildings over centuries, despite centuries of Ottoman rule, wars, and natural influences, indicating a high degree of architectural resilience. In addition, stone-carving settlements (Vrh, Dolac, Brezova) use marble from the same quarries as medieval builders, demonstrating adaptation to resource constraints. Marble from Studenica was used for the decoration of churches and for the production of marble tombstones; today, it is used in a limited but continuous way for the production of tombstones and for the restoration of medieval monuments. Socio-economic adaptation can also be seen in the emergence of rural tourism, which supports the local economy, and stone carving, which maintains indigenous crafts. The existence of local laws for the protection of the cultural heritage, in particular the UNESCO status, ensures the protection and implementation of the conservation of the cultural landscape, preserving the values of this area (

Table 5).

The area’s resilience is based on the synergy of natural, cultural, and spiritual factors. This matrix can serve as a model for assessing the resilience of other sacred areas with similar characteristics.

4.1.3. Indicators of Spiritual Resilience in the Studenica Monastery Area

Indicators of spiritual resilience in the Studenica Monastery area show exceptional vitality and the continuity of spiritual practices and beliefs. The centuries-old devotion to the cults of saints, especially St Simeon, St Sava, and St Stefan the First-Crowned, indicates a deep-rooted Orthodox spirituality. The presence of relics and mortal remains reinforces the sacred significance of the site and has attracted pilgrims for centuries. The variety of pilgrimage destinations, including the tombs of saints and their relics, water sources, and hermitages, testifies to a rich sacred topography. Numerous toponyms associated with St Sava indicate a deep integration of spirituality into the physical landscape. The continuity of liturgical and preserved monastic life, based on the Studenica Typikon, shows the resilience of spiritual practices despite numerous historical challenges. The inclusion of the Slava festival in the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage confirms the universal significance of local spiritual traditions, which are particularly present in this region. Regular cultural manifestations with spiritual themes, such as art colonies and choral festivals, as well as the realisation of the Digital Studenica project [

83], demonstrate the ability of spiritual culture to adapt to the modern context while preserving its essential values (

Table 6).

These indicators together indicate the area’s exceptional spiritual resilience, manifested in the continuity of practices, the adaptability of traditions, and the deep integration of spirituality into the physical and cultural landscape. The area’s resilience is based on the synergy of natural, cultural, and spiritual factors. This matrix can serve as a model for assessing the resilience of other sacred areas with similar characteristics.

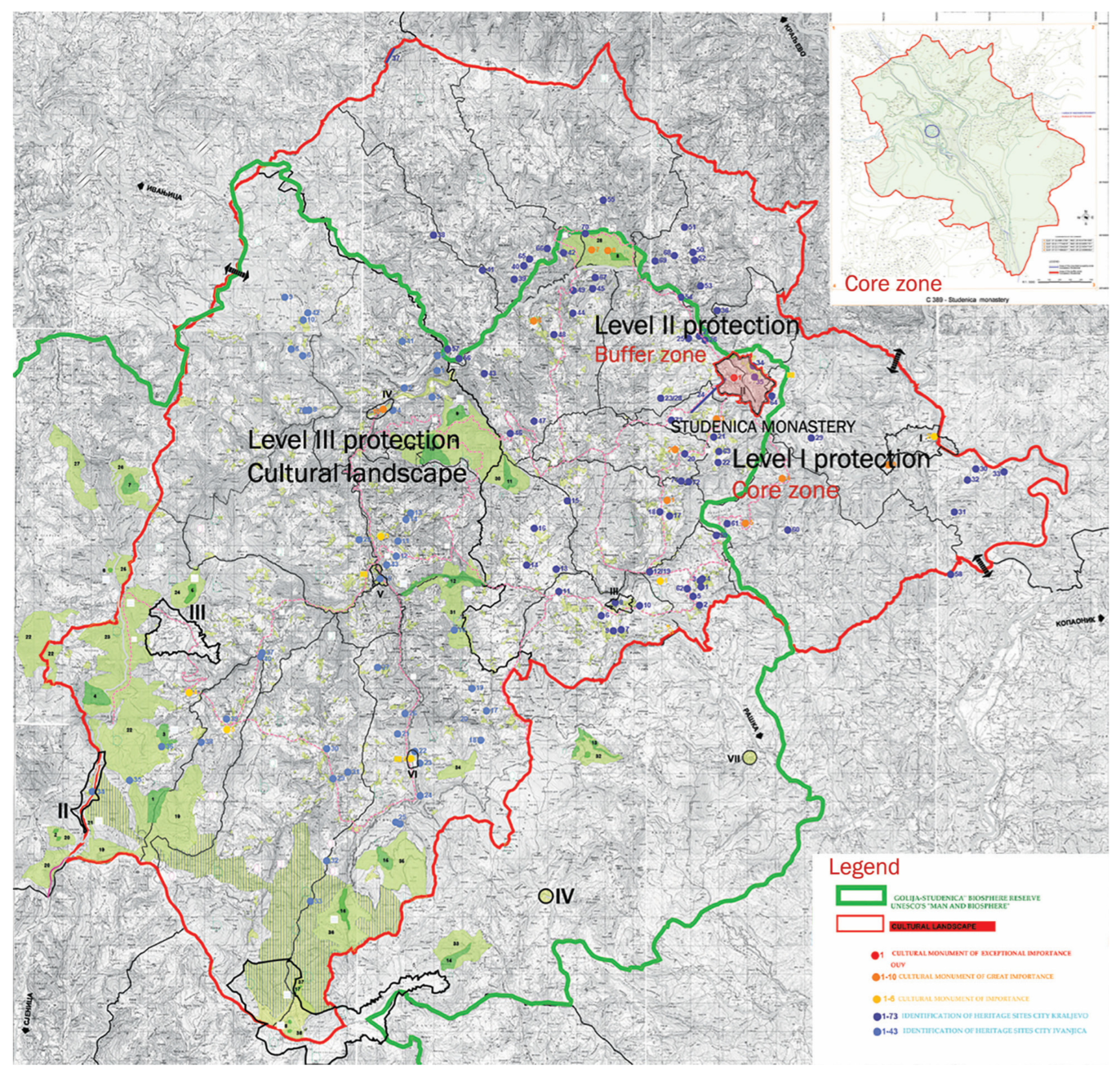

4.2. The Special Purpose Spatial Plan for the Studenica Monastery: Protection, Conservation, and Management of the Cultural Landscape

The Special Purpose Spatial Plan for the Studenica Monastery is the result of a comprehensive study that integrates research, analysis, and evaluation of the historical environment surrounding the monastery, including the nearby rural settlements. The identified sacred topography, through a network of sacred sites, led to the delineation of the cultural landscape boundaries covering 609 km

2, placing the concept of cultural landscapes at the heart of spatial planning policy [

63].

The Spatial Plan has been prepared in accordance with the United Nations International Guidelines for Urban and Spatial Planning [

84], which focus on a proactive and strategically coordinated approach to spatial development that ensures sustainable growth [

85]. This approach makes it possible to balance the demands of development with the need to protect the environment and cultural heritage [

86,

87]. The plan optimises the use of the area’s sacred, cultural, and natural features within the framework of a cultural landscape, emphasising sustainable development and the management of dynamic spatial change. The Spatial Plan proposes an integrated approach to the conservation and protection of the rich cultural and historical heritage. The identification and establishment of the cultural landscape as both an outcome and a means of ensuring the synergy of these values leads to the enhancement of the interactions between cultural, spiritual, and natural heritage [

88] (

Figure 10).

The analyses confirm that the cultural/sacred landscape of the Studenica Monastery belongs to the category of “organically developed landscapes”, shaped by historical, social, economic, and religious needs. The Spatial Plan covers the cadastral municipalities of Kraljevo (e.g., Bzovik, Brezova, Rudno) and Ivanjica (e.g., Brusnik, Vionica) and identifies “joint works of nature and man” [

2].

This concept reflects visual and aesthetic integrity achieved through harmony between cultural heritage and the natural environment, historical continuity linked to medieval traditions, and an enduring commitment to preserving national identity despite historical challenges [

89].

The visual integrity of the area covered by the Spatial Plan is defined by landscape features of exceptional value, characterised by the integration of cultural and historical monuments with the natural, topographical, compositional, visual, and landscape characteristics of the area, which must be protected and preserved. Therefore, the viewshed analysis carried out in QGIS used the Digital Terrain Model (DTM) of the area as the primary data source, defining visual points and vectorising contour lines with 2 m intervals [

87]. The result of the analysis is a map of visible and non-visible zones from key visual points. This map allowed an assessment of visibility and views both from the monastery complex itself and towards the Studenica Monastery [

90].

These analyses make it possible to predict the effectiveness of the Spatial Plan in regulating strategic urban planning decisions, identifying threats of urbanisation, mitigating the effects of development, and creating guidelines for the analysis of landscape characteristics and landscape protection (

Figure 11).

The Special Purpose Spatial Plan for the Studenica Monastery implements three levels of protection [

89]:

Strict construction controls

Biodiversity conservation

Scientific research and education

Regulated development policy

Monitoring, recreation, eco-religious tourism

Scientific research and education

The Spatial Plan establishes mechanisms for the enhancement of landscape features, ensuring infrastructure access to cultural assets, revitalising settlements, and actively integrating cultural routes into the tourism infrastructure within the area’s distinctive sacred topography [

89].

The area around Studenica Monastery adopts the concept of sacred landscapes as hubs of resilience by integrating cultural, natural, and spiritual heritage into sustainable development frameworks, in line with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 [

91]. This approach emphasises the protection and sustainable use of cultural landscapes while promoting resilience through traditional knowledge and religious practices. The implementation of policies and instruments aimed at affirming the cultural landscape of the Studenica Monastery has promoted new synergies between nature conservation and sustainable development.

The results of creating appropriate policies and instruments to affirm the cultural landscape have led to the establishment of new relationships between conservation and sustainable development as well as a visible strengthening of active links between the community and its natural and cultural environment. The recognition of the inextricable link between cultural, spiritual, and natural heritage through the cultural landscape model is increasingly contributing to the understanding and appreciation of spaces, not only around other Serbian medieval monasteries but also in areas such as the cultural landscape of Bač and its surroundings, which has been nominated for inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List [

92].

In addition to the legal framework and the Special Purpose Spatial Plan for the Studenica Monastery, which define specific areas for the management of the cultural landscape, a Management Plan for the Studenica Monastery (2020) has been developed [

93]. This Spatial Plan outlines strategic directions for the conservation, use, and management of the cultural/sacred landscape defined in the Spatial Plan, drawing on the protection of institutional and civil cooperation built up over decades of work to protect the cultural and natural heritage. Recognised roles, specific responsibilities, and communication channels between stakeholders have been crucial in creating the management scheme and organisational framework (

Figure 12).