Geotourism Based on Geoheritage as a Basis for the Sustainable Development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

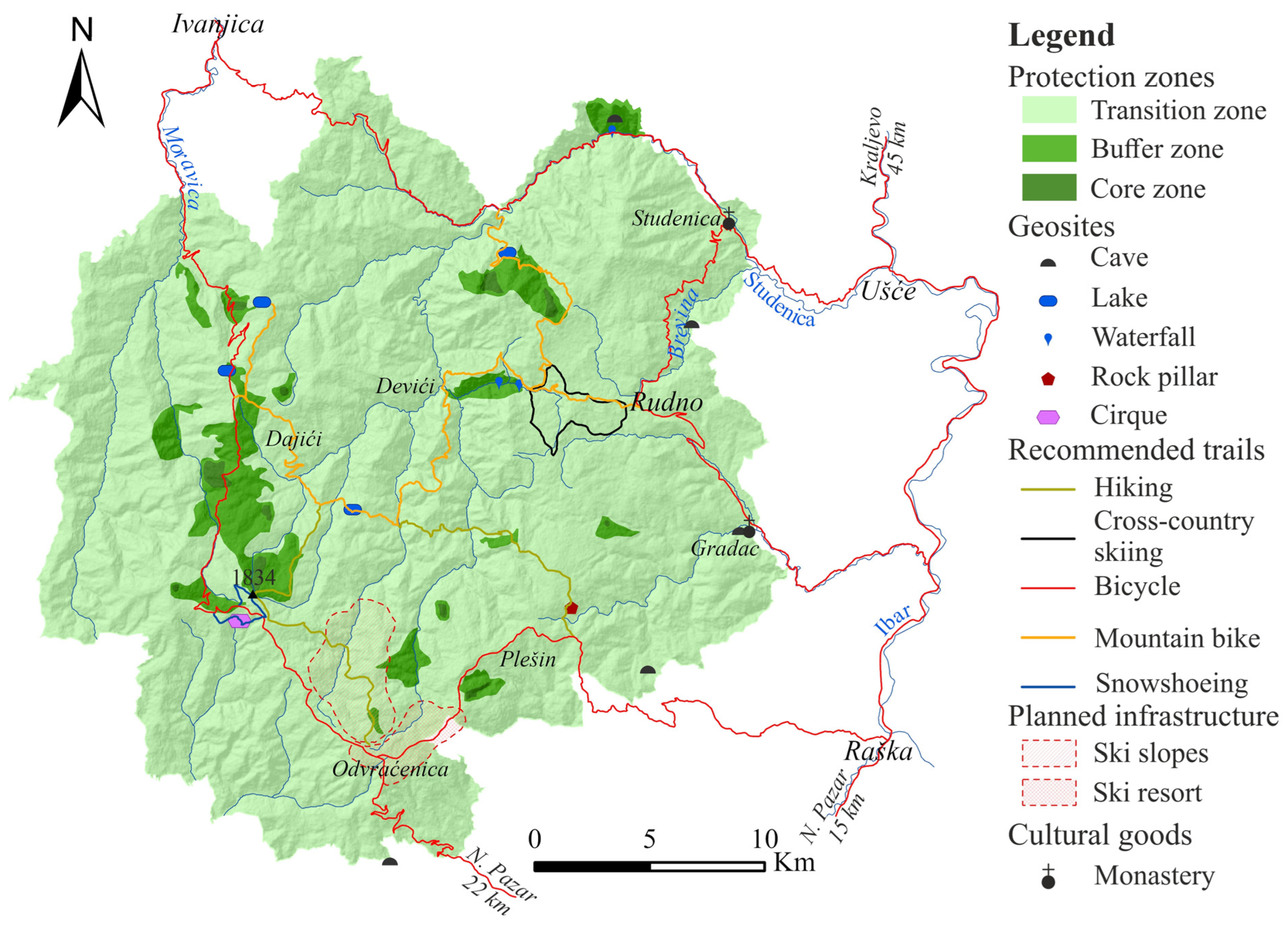

2. Study Area

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Višnić, T.; Milica, B. Geoheritage sites in the function of geotourism development in the Republic of Serbia. In Proceedings of the Synthesis-International Scientific Conference of IT and Business-Related Research, Belgrade, Serbia, 16 April 2015; pp. 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadry, B.N. Fundamentals of Geotourism: With Special Emphasis on Iran; SAMT Organization Publishers: Tehran, Iran, 2009; p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K.; Newsome, D. The scope and nature of geotourism. In Geotourism; Dowling, R.K., Newsome, D., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 512. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Developing the paradigm. Proc. Geologists’ Assoc. 2008, 119, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.E.; Barron, H.F. The role of geodiversity in delivering ecosystem services and benefits in Scotland. Scott. J. Geol. 2013, 49, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamata, D.; Mijović, D. (Eds.) The Inventory of Serbian Geoheritage Sites; Institute of Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2005; p. 21. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Djurović, P.; Mijović, D. Geoheritage of Serbia-Representative of its total geodiversity. Collect. Pap.-Fac. Geogr. Univ. Belgrade 2006, 54, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N.; Pavić, D. Canyons as potential geotourism attractions of Serbia—Comparative analysis of Lazar and Uvac canyons by using M-GAMmodel. Acta Geotur. 2014, 5, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N. Canyons and gorges as potential geotourism destinations in Serbia: Comparative analysis from two perspectives—General geotourists’ and pure geotourists’. Open Geosci. 2015, 7, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N. Geoheritage and geotourism potential of the Homolje area (eastern Serbia). Acta Geotur. 2017, 8, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N. Assessing the speleotourism potential together with archaeological and palaeontological heritage in Risovača Cave (Central Serbia). Acta Geotur. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Antić, A.; Tomić, N.; Marković, S. Karst geoheritage and geotourism potential in the Pek River lower basin (eastern Serbia). Geogr. Pannonica 2019, 23, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, S.A.; Nikolić, D.; Trnavac Bogdanović, D.; Carević, I. Assessment of karst geomorphosites on Kučaj and Beljanica mountains as a resource for the development of karst-based geopark. Acta Carsologica 2020, 49, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, M.; Tomić, N.; Radivojević, A.R.; Marković, S.B. Assessing the Geotourism Potential of the Niš City Area (Southeast Serbia). Geoheritage 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloš Marjanović, M.; Radivojević, A.R.; Antić, A.; Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G.; Lazarević, J.; Marković, R.S.; Tomić, N.; Langović Milićević, A.; Langović, Z.; et al. Geotourism and geoethics as support for rural development in the Knjaževac municipality, Serbia. Open Geosci. 2022, 14, 794–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belij, M.; Djurdjić, S.; Stojković, S. The Evaluation of Geoheritage for Geotourism Development: Case Study on the Potential Geopark Djerdap. Collect. Pap.-Fac. Geogr. Univ. Belgrade 2018, 66, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Marković, S.B.; Antić, A.; Tešić, D. Exploring the potential for geotourism development in the Danube region of Serbia. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2020, 8, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, M.D.; Lukić, D.; Radovanović, M.M.; Blešić, I.; Gajić, T.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Syromiatnikova, J.A.; Miljković, Ð.; Kovačić, S.; Kostić, M. How Can Tufa Deposits Contribute to the Geotourism Offer? The Outcomes from the First UNESCO Global Geopark in Serbia. Land 2023, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telbisz, T.; Ćalić, J.; Kovačević-Majkić, J.; Milanović, R.; Brankov, J.; Micić, J. Karst Geoheritage of Tara National Park (Serbia) and Its Geotouristic Potential. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, S.; Antić, A. Speleological approach for geotourism development in Zlatibor county (West Serbia). Turizam 2019, 23, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Stojsavljević, R. Spatial Planning and Sustainable Tourism—A Case Study of Golija Mountain (Serbia). Eur. Res. 2013, 65, 2918–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, S.; Gavrilović, L.; Đurović, P. Geodiversity and geoheritage: New approach to the interpretation of the terms. Bull. Serbian Geogr. Soc. 2010, 90, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujičić-Tešić, L. Geonasleđe Golije i Peštera (Geoheritage of Golija and Pešter). Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Mining and Geology, University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia, 2017; p. 179, (Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, S.A.; Carević, I.; Batoćanin, N.; Trnavac Bogdanović, D.; Bogdanović, N.; Tomić, D. Identification and Recording of Geoheritage Sites in the Area of the Golija Nature Park—Speleological Geoheritage (Project Report); Faculty of Geography, University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022; p. 22. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, S.A.; Langović, M.; Batoćanin, N.; Trnavac Bogdanović, D.; Bogdanović, N.; Tomić, D. Identification and Recording of Geoheritage Sites in the Area of the Golija Nature Park—Geomorphological and Hydrological Geoheritage (Project Report in Serbian); Faculty of Geography, University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022; p. 20. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Uredba o Zaštiti Parka Prirode Golija (Regulation on the Protection of the Golija Nature Park); No: 45/2001 i 47/2009; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade. Available online: https://golija-studenica.srbijasume.rs/pdf/UredbaGolija.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Mojsilović, S.; Baklaić, D.; Đoković, I. Tumač za List Sjenica K 34-29 (Interpreter for Geological Map Sjenica K 34-29); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1973; p. 71, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, M.; Pavlović, Z.; Klisić, M.; Malešević, M.; Stefanović, M.; Marković, O.; Trifunović, S. Tumač za List Vrnjci K 34-18 (Interpreter for Geological Map Vrnjci K 34-18); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1973; p. 71, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Vasović, M. Geography of Studenica River Basin; Društvo Umetnika Stari Grad: Beograd, Serbia, 1996; p. 228, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Urošev, M. Golijska Moravica Basin—Hydrological Analysis, Special ed.; Geographic Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA: Belgrade, Serbia, 2007; Volume 69, p. 123, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Luković, M. Phisical-geographical characteristics of the Biosphere Reserve “Golija-Studenica”. In Biosphere Reserve Golija-Studenica—Nature Park Golija; Zagorac, D., Šekler, D., Eds.; Srbijašume: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miljanović, D. Stanje životne sredine na području Parka prirode “Golija”(Environmental status in Nature Park “Golija”). Bull. Serbian Geogr. Soc. 2005, 85, 249–264, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, M.; Pavlović, Z.; Klisić, M.; Brković, T.; Malešević, M.; Trifunović, S. Geološka Karta 1:100.000, List Vrnjci (Geological Map 1:100.000, Sheet Vrnjci); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, M.; Pavlović, Z.; Klisić, M.; Brković, T.; Malešević, M.; Trifunović, S. Geološka Karta 1:100.000, List Novi Pazar (Geological Map 1:100.000, Sheet Novi Pazar); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Brković, T.; Malešević, M.; Urošević, M.; Trifunović, S.; Radovanović, Z. Geološka Karta 1:100.000, List Ivanjica (Geological Map 1:100.000, Sheet Ivanjica); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mojsilović, S.; Đoković, I.; Baklaić, D.; Rakić, B. Geološka Karta 1:100.000, List Sjenica (Geological Map 1:100.000, Sheet Sjenica); Savezni Geološki Zavod: Beograd, Serbia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Milanović, A.; Milovanović, B. A review of climate features of Golija Mountain in the function of space evaluation. Collect. Pap.-Fac. Geogr. Univ. Belgrade 2010, 58, 29–46, (Summary in English). [Google Scholar]

- CORINE Land Cover Page. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover/clc2018 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention Page. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/389/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Marinčić, S.; Ilić, M.; Nešić, D.; Kličković, M.; Savovski, B.; Šehovac, E.; Sarić, N. Identification and Recording of Geoheritage Objects in the Golija Nature Park—Project Report; Institute of Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2019; p. 56. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D.; Caetano Alves, M.I. Geomorphosite assessment in Montesinho Natural Park. Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waele, J.; Di Gregorio, F.; Gasmi, N.; Melis, M.T.; Talbi, M. Geomorphosites of Touzer region (South-west Tunisia). Ital. J. Quat. Sci. 2005, 18, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Vujičić, M.D.; Vasiljević, D.A.; Marković, S.B.; Hose, T.A.; Lukić, T.; Hadžić, O.; Janićević, S. Preliminary geosite assessment model (GAM) and its application on Fruška Gora Mountain, potential geotourism destination of Serbia. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2011, 51, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košanin, N. Dajićko Jezero-Hidrobiološka Studija (Dajić Lake-Hydrobiological Study); Glasnik Srpske Kraljevske Akademije Nauka: Beograd, Serbia, 1908; p. 50. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Cvijić, J. Tragovi starih glečera u Srbiji (Traces of old glaciers in Serbia). Glas. Srp. Geogr. Društva 1914, 3–4, 211–212. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ršumović, R. Reljef Sliva Golijske Moravice (Relief of the Golije Moravica Basin), Special ed.; Geographic Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA: Belgrade, Serbia, 1960; Volume 16, p. 128, (Summary in French). [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović, D. Glacijalni reljef Srbije (Glacial relief of Serbia). Bull. Serbian Geogr. Soc. 1976, 56, 9–19, (Summary in French). [Google Scholar]

- Tešić, Ž.; Gigov, A.; Bogdanović, M.; Milić, Č. Tresave Srbije (Bogs of Serbia). J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijic” SASA 1979, 31, 64, (Summary in French). [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilović, D.; Menković, L.; Belij, S. Objekti geomorfološkog nasleđa (Geomorphological geoheritage sites). In The Inventory of Serbian Geoheritage Sites; Karamata, D., Mijović, D., Eds.; Institute of Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2005; pp. 8–12. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Park Prirode Golija—Predlog za Stavljanje Pod Zaštitu Prirode (Golija Nature Park-Proposal for Environmental Protection); Institute of Nature Conservation of Serbia: Belgrade. Available online: https://www.ekologija.gov.rs/sites/default/files/inline-files/PP%20Golija.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Karajović, S.; Jarić, Z.; Folić, N.; Derić, B.; Miljanović, D.; Nenekovič, M. Prostorni Plan Područja Posebne Namene Parka Prirode “Golija” (Spatial Plan of Special Purpose Area of the Nature Park “Golija”); The Agency for Spatial and Urban Planning of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2004; p. 52. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Čižmar, S. Master Plan Razvoja Turizma na Goliji sa Poslovnim Planom (Master Plan for the Development of Tourism in Golija with a Business Plan); Hotvat HTL Zagreb, Ministarstvo Ekonomije i Regionalnog Razvoja: Beograd, Serbia, 2007; p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Prostorni Plan Područja Posebne Namene Parka Prirode “Golija” (Spatial Plan of Special Purpose Area of the Nature Park “Golija”). Centar za Planiranje Urbanog Razvoja. 2009. Available online: https://media.ivanjica.gov.rs/2019/03/PPPPN-PP-Golija_Sluzbeni-glasnik-RS-br.16-2009.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Nikolić, S. Golija—Ekološko Turistička Studija sa Programskom Osnovom (Golija—Ecological and Turismological Study); Serbean Geographical Society: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014; p. 176, (Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Pantić, M.; Čolić, N.; Milijić, S. Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserve (Serbia) as a Driver of Change. Eco.mont–J. Prot. Mt. Areas Res. Manag. 2021, 13, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, N.B.; Milinčić, U.; Stanjačević, A.; Milinčić, M. Can Winter Tourism Be Truly Sustainable in Natural Protected. J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2019, 69, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Global Geoparks Network. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001500/150007e.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Dowling, R. Geotourism and Geoparks—A Tool for Geoconservation and Rural Development in Vulnerable environments: A Case Study from Iceland. Geoheritage 2014, 6, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection. List of Potential Areas for the Establishment of Geoparks in the Republic of Srbija (Report). 2017. Available online: https://www.ekologija.gov.rs/lat/saopstenja/sektor-za-zastitu-prirode-i-klimatske-promene/geoparkovi (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. Geoheritage and Geotourism. In Geoheritage and Geoconservation: The Challenges; Brilha, J., Reynard, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Basi Arjana, I.W.; Eenawati, N.M.; Atsatawa, I.K. Geotourism products industry element: A community approach. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Joint Conference on Science and Technology (IJCST), Bali, Indonesia, 18–19 October 2018; Volume 953, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto de Carvalho, C.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts—Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šambronská, K.; Matušíková, D.; Šenková, A.; Kormaníková, E. Geotourism and its sustainable products in destination management. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanić Jovanović, S. Educational role of excursion tourism. Tur. Posl. 2015, 15, 125–133, (Abstract in English). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.T.; Sanchez, J.E.O.; Lopez, E.R.A. Educational tourism. A theoretical review of the phenomenon. J. Adm. Sci. 2022, 4, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Habibi, H.; Ruban, D.A.; Ermolaev, V.A. Educational Potential of Geoheritage: Textbook Localities from the Zagros and the Greater Caucasus. Heritage 2023, 6, 5981–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigna, A.A.; Forti, P. Caves: The most important geotouristic feature in the world. Tour. Karst Areas 2013, 6, 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cigna, A.A. Tourism and show caves. Z. Geomorphol. 2016, 60, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tičar, J.; Tomić, N.; Breg Valjavec, M.; Zorn, M.; Marković, S.B.; Gavrilov, M.B. Speleotourism in Slovenia: Balancing between mass tourism and geoheritage protection. Open Geosci. 2018, 10, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, N.; Antić, A.; Marković, S.B.; Đorđević, T.; Zorn, M.; Breg Valjavec, M. Exploring the Potential for Speleotourism Developmentin Eastern Serbia. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. Applying the values of geoethics for sustainable speleotourism development. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A. Speleological Geoheritage and Speleotourism: Inventory and Tourist Evaluation of Show Caves in Serbia. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2022; p. 249, (Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, A. Spelotourism in Serbia—Condition and development perspectives. Collect. Pap.-Fac. Geogr. Univ. Belgrade 2006, 56, 183–194, (Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Panizza, V.; Mennella, M. Sassari Assessing geomorphosites used for rock climbing. The example of Monteleone Rocca Doria (Sardinia, Italy). Geogr. Helv. 2007, 62, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciascai, O.R.; Dezsi, S.; Rus, K.A. Cycling Tourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications, Multiple Impacts, Vulnerabilities, and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S.; Ostojić, M.; Popović, I. Golijska jezera—neiskorišćeni turistički potencijal (Golija Lakes—Untapped Tourist Potential). In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference Science and Higher Education in Function of Sustainable Development, Užice, Serbia, 5 October 2012; pp. 1–6. (In Serbian). [Google Scholar]

- Senese, A.; Pelfini, M.; Maragno, D.; Bollati, I.M.; Fugazza, D.; Vaghi, L.; Federici, M.; Grimaldi, L.; Belotti, P.; Lauri, P.; et al. The Role of E-Bike in Discovering Geodiversity and Geoheritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowshoeing Guide. Available online: https://snowshoeing.rs/wp-content/uploads/snowshoeing-guide.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

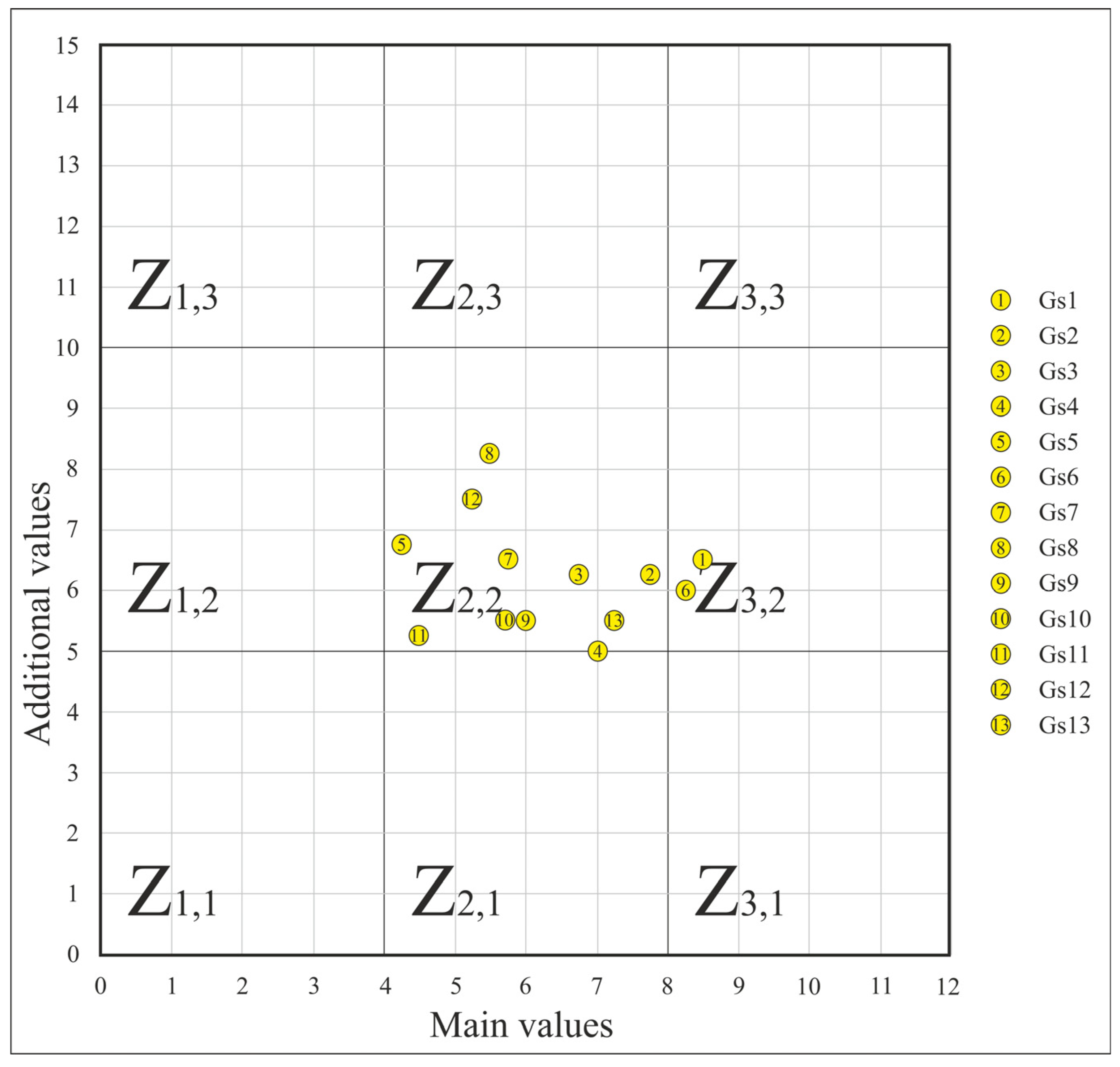

| Geosite Label | Main Values | Additional Values | Field | GAM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSE + VSA + VPr | Σ | VFn + VTr | Σ | |||

| Gs1 | 2.00 + 3.25 + 3.25 | 8.50 | 3.25 + 3.25 | 6.50 | Z3,2 | 15.00 |

| Gs2 | 2.00 + 3.00 + 2.75 | 7.75 | 3.00 + 3.25 | 6.25 | Z2,2 | 14.00 |

| Gs3 | 1.75 + 2.50 + 2.50 | 6.75 | 3.25 + 3.00 | 6.25 | Z2,2 | 13.00 |

| Gs4 | 2.00 + 2.75 + 2.25 | 7.00 | 2.25 + 2.75 | 5.00 | Z2,2 | 12.00 |

| Gs5 | 1.25 + 0.75 + 2.25 | 4.25 | 3.50 + 3.25 | 6.75 | Z2,2 | 11.00 |

| Gs6 | 2.50 + 2.75 + 3.00 | 8.25 | 2.25 + 3.75 | 6.00 | Z3,2 | 14.25 |

| Gs7 | 1.00 + 2.00 + 2.75 | 5.75 | 2.75 + 3.75 | 6.50 | Z2,2 | 12.25 |

| Gs8 | 2.00 + 1.00 + 2.50 | 5.50 | 3.50 + 4.75 | 8.25 | Z2,2 | 13.75 |

| Gs9 | 1.50 + 2.00 + 2.50 | 6.00 | 2.25 + 3.25 | 5.50 | Z2,2 | 11.50 |

| Gs10 | 1.50 + 1.75 + 2.50 | 5.75 | 2.00 + 3.50 | 5.50 | Z2,2 | 11.25 |

| Gs11 | 1.50 + 0.50 + 2.50 | 4.50 | 2.00 + 3.25 | 5.25 | Z2,2 | 9.75 |

| Gs12 | 1.75 + 1.50 + 2.00 | 5.25 | 2.75 + 4.75 | 7.50 | Z2,2 | 12.75 |

| Gs13 | 1.75 + 2.75 + 2.75 | 7.25 | 2.75 + 2.75 | 5.50 | Z2,2 | 12.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrović, A.S.; Carević, I.; Trnavac Bogdanović, D.; Langović, M.; Batoćanin, N.; Petronijević, J. Geotourism Based on Geoheritage as a Basis for the Sustainable Development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia. Land 2025, 14, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040835

Petrović AS, Carević I, Trnavac Bogdanović D, Langović M, Batoćanin N, Petronijević J. Geotourism Based on Geoheritage as a Basis for the Sustainable Development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia. Land. 2025; 14(4):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040835

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrović, Aleksandar S., Ivana Carević, Dušica Trnavac Bogdanović, Marko Langović, Natalija Batoćanin, and Jovan Petronijević. 2025. "Geotourism Based on Geoheritage as a Basis for the Sustainable Development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia" Land 14, no. 4: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040835

APA StylePetrović, A. S., Carević, I., Trnavac Bogdanović, D., Langović, M., Batoćanin, N., & Petronijević, J. (2025). Geotourism Based on Geoheritage as a Basis for the Sustainable Development of the Golija Nature Park, Southwest Serbia. Land, 14(4), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040835