Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland)

Abstract

1. Introduction

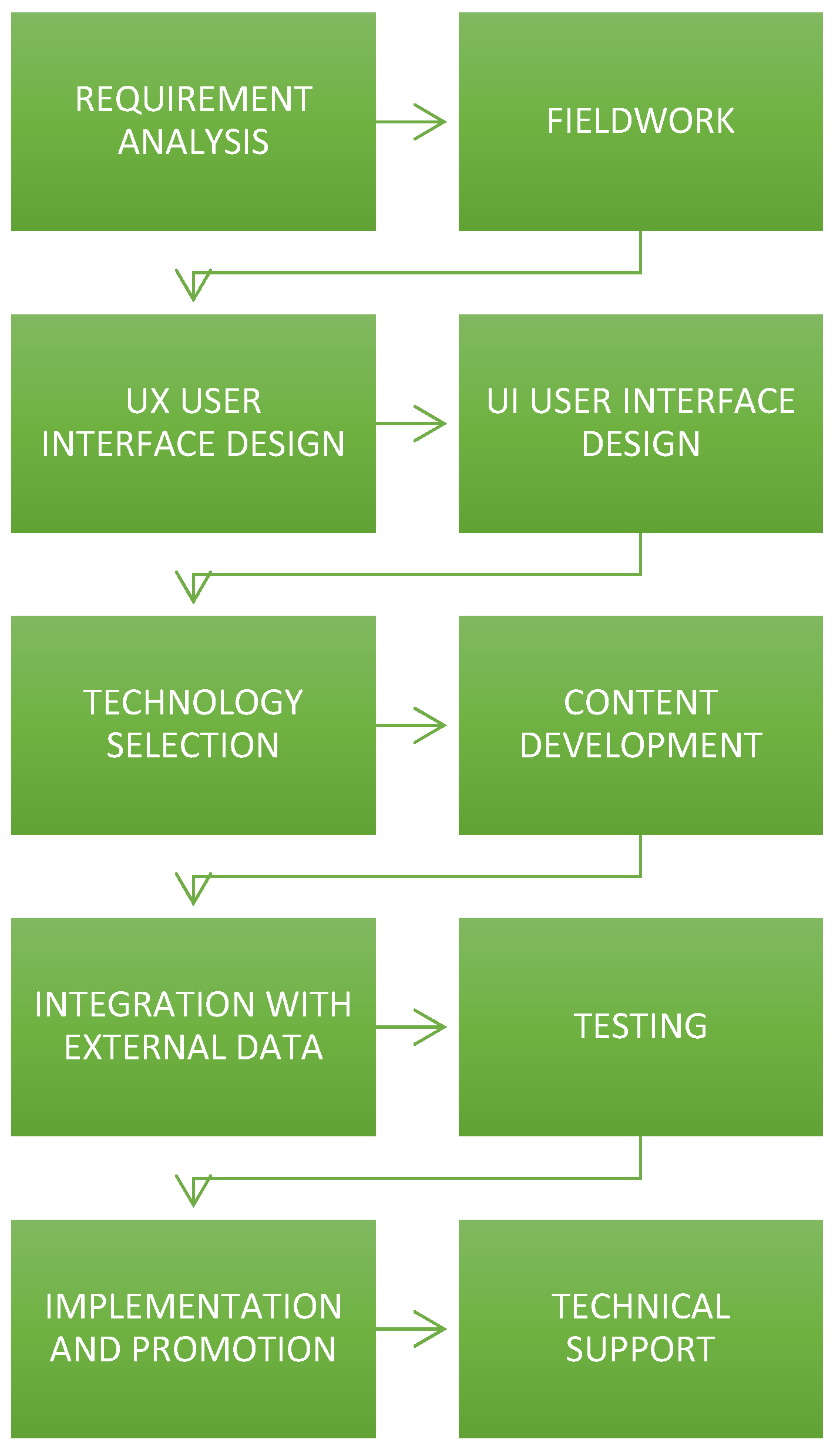

2. Materials and Methods

- Operating system and application availability

- User interface

- Functionality

3. Results

3.1. Internet Survey

3.2. Characteristics and Evaluation of Existing Applications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dowling, R.S. Geotourism’s Global Growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. 3G’s for modern geotourism. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R. The scope and nature of geotourism. In Geotourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Global Geoparks Network. Available online: https://www.visitgeoparks.org/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Zouros, N. The European Geoparks Network. Episodes 2004, 27, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Farsani, N.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C. Geotourism and geoparks as novel strategies for socio-economic development in rural areas. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 13, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.-L. Geotourism—Examining Tools for Sustainable development. Geosciences 2021, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouros, N.; Valiakos, I. Geoparks management and assessment. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2010, 43, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, S. The role of mobile technology in tourism: Patents, articles, news, and mobile tour app reviews. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcic, J.; Komsic, J.; Markovic, S. Mobile technologies and applications towards smart tourism—State of the art. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 82–103. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, B. A convergence of mobile device application use and smart tourism: A comparison of Korean and Non-Korean smart tourists. J. Internet Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manczak, I.; Bajak, M. Turystyczne aplikacje mobilne—Ocena funkcjonalności oprogramowania VisitMalopolska. Turyzm/Tourism 2021, 31, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Duan, L. The concept of smart tourism in the context of tourism information services. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Molokáč, M.; Kornecká, E.; Pavolová, H.; Bakalár, T.; Jesenský, M. Online Marketing of European Geoparks as a Landscape Promotion Tool. Land 2023, 12, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassoulas, C.; Nikolakakis, E.S. Digital Tools to Serve Geotourism and Sustainable Development at Psiloritis UNESCO Global Geopark in COVID Times and Beyond. Geosciences 2022, 12, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsiharjo, A.R.; Urfan, F.; Ruhimat, M.; Setiawan, I.; Logayah, D.S. Mobile GIS app for guiding geopark at UNESCO Global Geopark Ciletuh Palabuhanratu, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 683, 012109. [Google Scholar]

- Insani, N.; Narmaditya, B.S.; Habibi, M.M.; Majid, Z.; A’rachman, F.R. Mobile GIS Application for Supporting Edutourism at UNESCO Global Geopark Batur Bali, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1039, 012043. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmawati, D.; Alpiana; Adiansyah, J.S. The Effectivity of Virtual Tour as an Alternative of Ecotourism Method: A Case Study of Tambora National Geopark, Indonesia. Adv. Eng. Res. 2023, 203, 282–285. [Google Scholar]

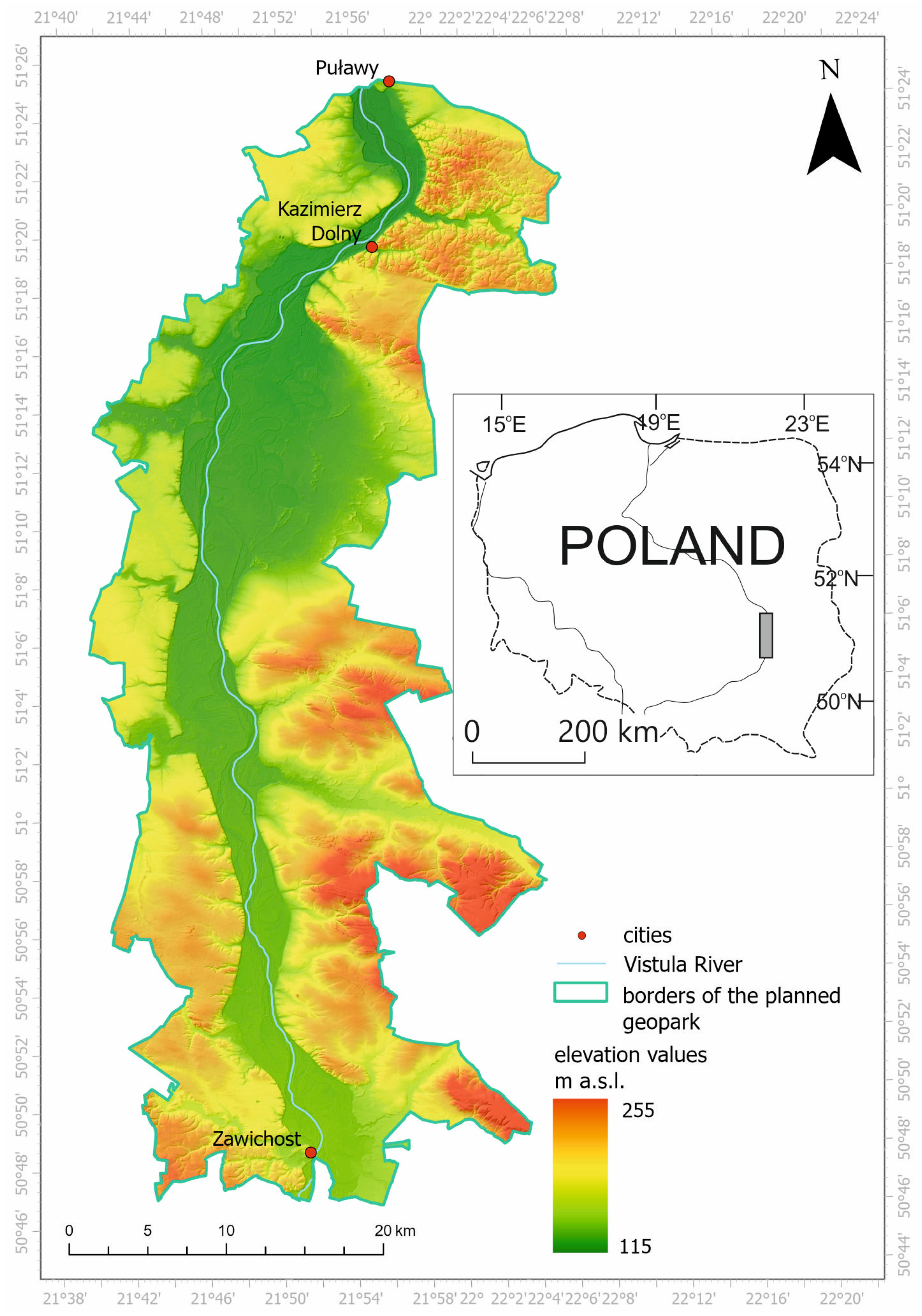

- Harasimiuk, M.; Domonik, A.; Machalski, M.; Pinińska, J.; Warowna, J.; Szymkowiak, A. Małopolski Przełom Wisły—Projekt geoparku. Przegląd Geol. 2011, 59, 405–416. [Google Scholar]

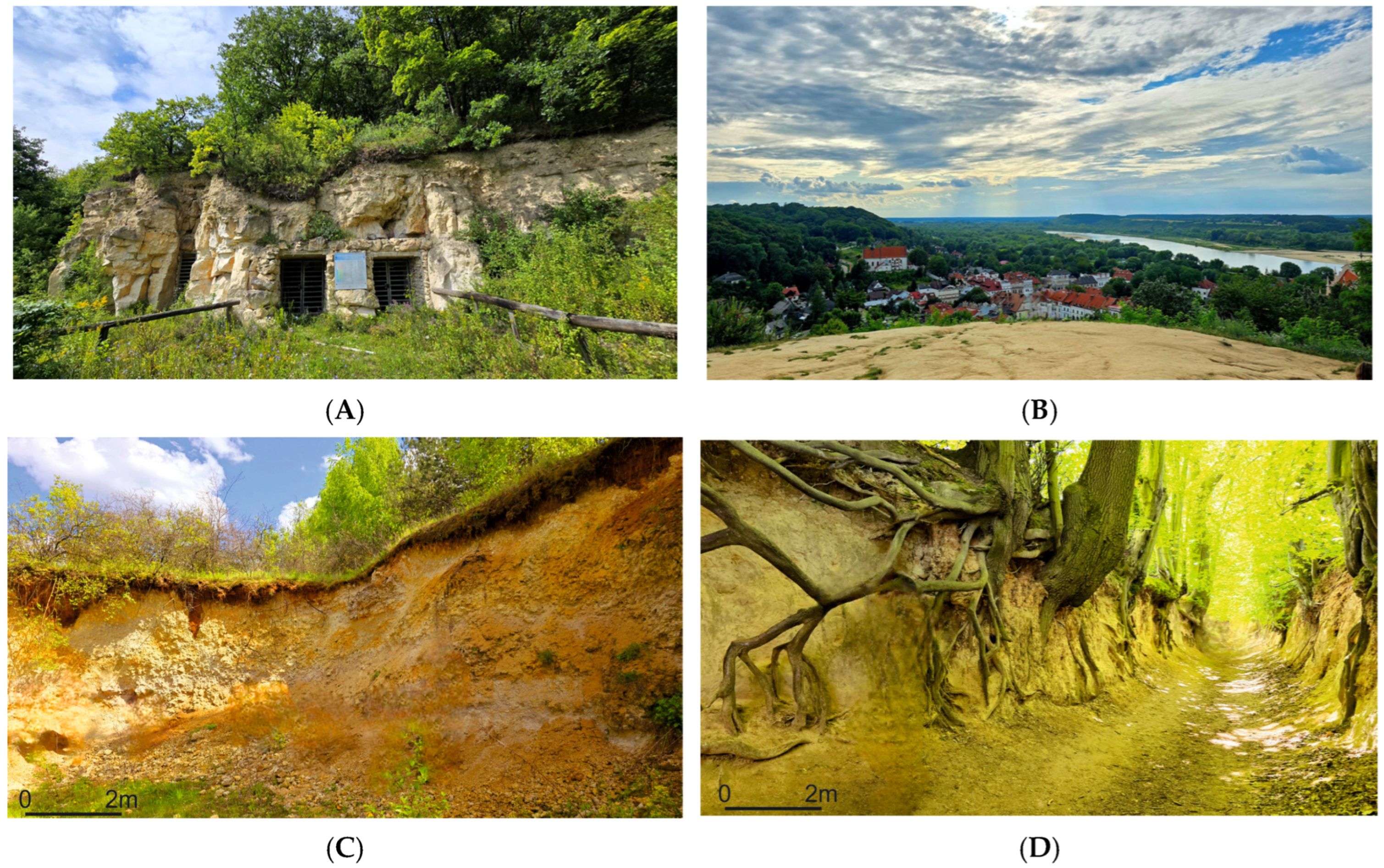

- Zgłobicki, W.; Kołodyńska-Gawrysiak, R.; Gawrysiak, L. Gully erosion as a natural hazard: The educational role of geotourism. Nat. Hazards 2015, 79, 159–181. [Google Scholar]

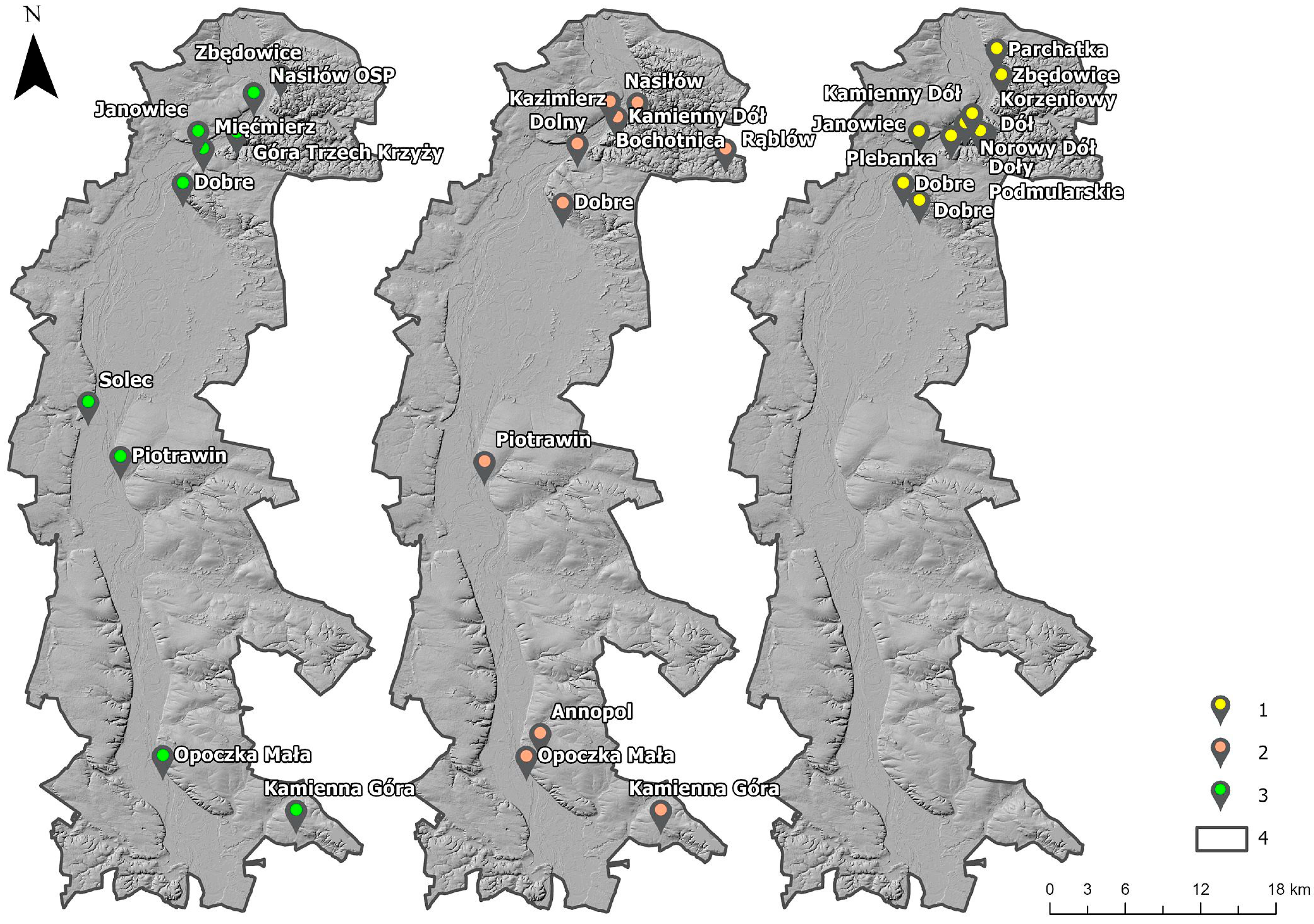

- Warowna, J.; Zgłobicki, W.; Gajek, G.; Telecka, M.; Kołodyńska-Gawrysiak, R.; Zieliński, P. Geomorphosite assessment in the proposed Geopark Vistula River Gap (E Poland). Quaest. Geogr. 2014, 33, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Gajek, G.; Zgłobicki, W. Ocena możliwości wykorzystania punktów widokowych projektowanego Geoparku Małopolski Przełom Wisły w edukacji geomorfologicznej i geoturystyce. Landf. Anal. 2021, 40, 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gajek, G.; Zgłobicki, W.; Kołodyńska-Gawrysiak, R. Geoeducational Value of Quarries Located Within the Małopolska Vistula River Gap (E Poland). Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, B.; Mazurek-Kusiak, A. Rola dóbr kulturowych i przyrodniczych w rozwoju turystyki w gminie Kazimierz Dolny. Zesz. Probl. Postępów Nauk Rol. 2009, 542, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J.; de Carvalho, C.N.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgłobicki, W.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B. Geomorphological heritage as a tourist attraction. A case study in Lubelskie Province, SE Poland. Geoheritage 2013, 5, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syroka, K. Projekt Wirtualnego „Kazimierskiego Szlaku Geoturystycznego”. Master’s Thesis, UMCS, Lublin, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cagara, M. Ocena Natężenia Oraz Uwarunkowań Sezonowego Zróżnicowania Natężenia Weekendowego Ruchu Turystycznego W okolicy Kazimierza Dolnego w Świetle Badań Terenowych Oraz Analiz GIS. Master’s Thesis, UMCS, Lublin, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Papińska-Kacperek, J. E-tourism services in Polish tourists’ opinions. Probl. Manag. 21st Century 2013, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska-Legwand, A. Wykorzystanie technologii informacyjno-komunikacyjnych w ostępie do informacji i usług turystycznych w świetle wyników badań przeprowadzonych wśród polskich turystów w województwie małopolskim. Turyzm/Tourism 2019, 29, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota, N. Lokalizacyjna aplikacja mobilna jako narzędzie badań ruchu turystycznego miasta w długim okresie. Stud. Oeconomica Posnaniensia 2014, 2, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Promoting and interpreting geoheritage at the local level—Bottom-up approach in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes, Sudetes, SW Poland. Geoheritage 2019, 11, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Functionality | Not Useful | Not Very Useful | Useful | Very Useful |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactive maps of the region (e.g., routes and trails, points of interest) | 1 | 3 | 37 | 80 |

| Database of interesting sites | 1 | 6 | 43 | 71 |

| Changing the map background | 1 | 36 | 52 | 32 |

| Adding sites to favorites | 3 | 19 | 68 | 31 |

| Site search | 0 | 7 | 59 | 55 |

| Filtering sites | 4 | 8 | 63 | 46 |

| Ability to add your sites/photos | 18 | 33 | 50 | 20 |

| Finding sites with augmented reality technology | 23 | 43 | 43 | 12 |

| 3D model of the area | 13 | 42 | 52 | 14 |

| Ability to measure distances on a map | 10 | 10 | 62 | 39 |

| QR code scanning | 20 | 23 | 57 | 21 |

| Playing with other users | 43 | 46 | 24 | 8 |

| Application Availability | User Interface | Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| “Geopark Zary” (Geopark Muskau Arc) (Germany, Poland) | ||

| Android, On-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | Map (Google Maps), Touristic routes (Google Maps), Change map background, Filter sites, Search for sites. A collection of sites with information about them |

| Øhavet Geopark (Denmark) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Complicated navigation Lots of windows | Map (Google Maps), Adding sites to favorites, Touristic routes (Google Maps), Tourist routes—maps, Change of map background, Collection of sites with information about them |

| Geopark Vestjylland (Denmark) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Complicated navigation Lots of windows | Adding sites to favorites, Tourist routes (Google Maps), Tourist routes—maps, Changing the map background, Collection of sites with information about them, Map (Google Maps) |

| Terras de Cavaleiros Geopark (Portugal) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line, off-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | Adding sites to favorites, Finding AR sites, Changing the map background, Collection of sites with information about them, Ability to add your sites/photos, Hiking routes (Google Maps), Map (Google Maps) |

| Cliffs of Fundy Geopark (Canada) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | A collection of sites with information about them, Hiking routes (Google Maps), Map (Google Maps) |

| Geopark Karawanken (Austria, Slovenia) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus Lots of windows | Tourist routes (Google Maps), Tourist routes—maps, Collection of sites with information about them, Interesting facts/questions, Code scanning, Map (Mapbox) |

| Geopark Magma (Norway) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | Tourist routes (Google Maps), Collection of sites with information about them, Playing with others, Map (Google Maps) |

| Fire & Ice Geopark (not a global geopark) (Canada) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | Tourist routes (Google Maps), Collection of sites with information about them, Map (Google Maps) |

| Waitaki Whitestone Geopark (New Zealand) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line, off-line | Easy navigation Non-intuitive menus | Collection of routes with information, Adding routes to favorites, Map (Mapbox) |

| Geopark Lyd (Denmark) (not a global geopark) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line, off-line | Easy navigation Non-intuitive menus | Touristic routes (Google Maps), Collection of routes with information, Adding routes to favorites, Map (Mapbox) |

| Nisyros Geopark (Greece) (not a global geopark) | ||

| Android, IOS, On-line, off-line | Easy navigation Intuitive menus | Tourist routes—maps, Collection of sites with information about them, Adding sites to favorites, Map (own) |

| Name of Application | Information About the Geopark | Other Attractions | Geosites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geopark Zary | A brief description of the history of the geopark | Cultural and historical buildings, Swimming pools, Tourist information | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Øhavet Geopark | A brief description of the history of the creation of the geopark | Biking trails, Canoeing, Mountain biking trails, Listening to audio information, Drinking water sites, Diving sites, Geology sites, Fishing grounds, Picnic sites, Treasure hunting sites, Playgrounds, Lodging sites, Camping sites, Toilets | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Geopark Vestjylland | A brief description of the history of the creation of the geopark Facts about the geopark Information about UNESCO Global Geoparks. Information on other Danish geoparks | Shelters, Museums, Biking points, Historical buildings, Biking trails, Canoeing, Horseback riding trails, Shelters, Campgrounds | Expanded description of a site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Terras de Cavaleiros Geopark | Current news regarding geopark and events | Stores, Aquaparks, Boat trips, River beaches, Accommodation, Restaurants, Cultural and religious monuments | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Cliffs of Fundy | A brief description of the history of the creation of the geopark | Museums, Ocean Research Center | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Geopark Guide | Facts about the geopark Description of the research carried out in the geopark. A brief description of geopark history | Museums, Viewpoints, Mountain climbing points, Information points | Interactive element on the map |

| Magma | Facts about the geopark A brief description of the history of the creation of the geopark | Accommodation, Campsites Information outlets, Museums Restaurants | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Fire & Ice Geopark | A brief description of the geopark history. Facts about the geopark | Museums, Cultural sites | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Waitaki Whitestone Geopark | Long description of the geopark. Current news regarding geopark and events | No information available | Brief description of the site with photos and route, Interactive element on the map |

| Geopark Lyd | A brief description of the geopark history | No information available | Brief description of the site with photos and route |

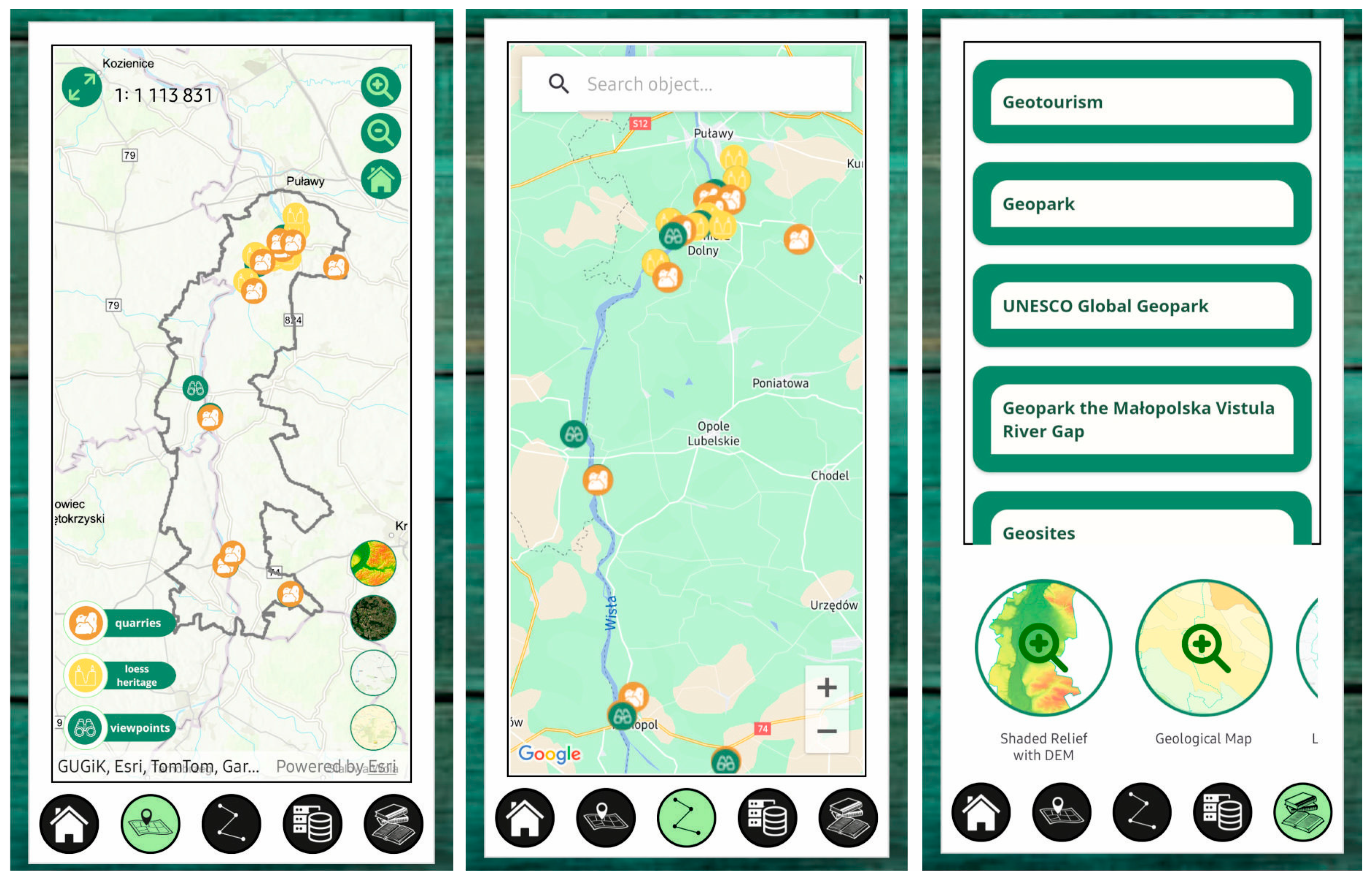

| Functionality | Content |

|---|---|

| Availability on Android | Description of selected geosites |

| Online and offline access | Geological and geomorphological maps |

| Intuitive menus | Description of the history of the proposed geopark |

| Interactive map of facilities | Original photos and graphic elements |

| Map of tourist routes | Glossary of basic geotourism terms |

| Collection of tourist facilities | |

| Changing the map background | |

| Change the language to English and Polish | |

| Filtering sites in a collection | |

| Searching for sites in a collection |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kneć, A.; Zgłobicki, W. Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland). Land 2025, 14, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040676

Kneć A, Zgłobicki W. Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland). Land. 2025; 14(4):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040676

Chicago/Turabian StyleKneć, Agata, and Wojciech Zgłobicki. 2025. "Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland)" Land 14, no. 4: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040676

APA StyleKneć, A., & Zgłobicki, W. (2025). Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland). Land, 14(4), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040676