Abstract

While informal settlements have been extensively studied in the Global South, their counterparts in the Global North remain under-researched, despite their critical role in shaping urban morphology. This paper introduces “Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping”, a framework designed to uncover micro-morphological knowledge through the lived spatial experiences of marginalized residents. By examining the epistemological question “whose morphology?”, this study critiques conventional urban morphological methods, which often disregard spatial practices embedded in the everyday lives of marginalized communities. Focusing on a marginalized lilong settlement in downtown Shanghai, this research work integrates critical cartography with ethnographic fieldwork to develop a micro-morphological mapping process centered on resident narratives. This process, structured around the phases of finding, inscription, and simplification, demonstrates how residents’ daily practices actively shape and reconfigure their built environment. This study offers an alternative perspective to understand the dynamic processes of urban renewal in informal settlements and emphasizes the dialectical relationship between resident-driven spatial practices and the transformation of the urban form. By broadening urban morphology’s methodological framework, this research provides insights into how resident-driven mapping can inform localized regeneration strategies. The findings highlight the potential for marginalized communities to shape urban regeneration policies, advocating for inclusive, resident-centered development.

1. Introduction

In the spring of 2016, as part of my doctoral research, my supervisor guided me to an atypical lilong building near People’s Square in downtown Shanghai. While the exterior of the building appeared indistinguishable from the surrounding modern structures, its interior unveiled a complex spatial configuration that highlighted unique socio-spatial relationships. Windows acted as gateways to terraces, residents’ reclining chairs stretched across corridors, and at the end of the hallway, a bathroom was separated only by a curtain. Traditional urban analyses, which often rely on urban planning and regulation, fail to capture the complex and nuanced realities of this Shanghai lilong community’s living conditions. Instead, this lilong community fluctuates at multiple intermediate and extreme positions that defy the “status quo of urban studies [1]”.

This seemingly ordinary building exemplifies the lilong housing form, constructed between the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Shanghai’s foreign concessions, born from the collision of Chinese vernacular traditions and colonial modernity, reflecting hybrid spatial practices common to cities of the Global South [2,3]. Like informal settlements in Lagos or Mumbai, lilongs emerged as adaptive responses to socio-economic marginalization and transnational power asymmetries, yet they also subverted Eurocentric urban norms by embedding communal lifeworlds into rigid spatial frameworks [4]. This tension between colonial imposition and local agency aligns with the Global South’s broader struggles to negotiate modernity on its own terms [5].

The Global South is a concept that highlights urban practices and conditions historically marginalized in mainstream urban theory. These conditions include extreme informality [6], distinct social relations [7,8], the absence of institutional governance [9], and lingering post-colonial legacies [10]. While these conditions are often associated with cities in the Global South, they can also be observed in cities of the Global North [11]. For example, hybrid spaces shaped by colonial encounters and grassroots adaptations appear in Shanghai’s lilongs, emerging forms of civic participation and activism are evident in Seoul [12], and informal street markets thrive in London [13]. In this sense, the Global South signals new and dissident forms of urban governance, manifesting through both formal and informal actions and structures [14]. This opens up the possibility to explore how findings, theories, and practices from specific case studies can be employed, expanded, or evaluated across diverse urban contexts, regardless of geographic location [15].

Morphological research can be viewed as a tool—a “prosthesis”—that extends human vision and memory [16], enabling the detection, naming, and description of spatial patterns and forms. It also serves to correct the simplifications introduced by unilateral globalization which have been disseminated from colonizers to the colonized [17].

Typomorphologists such as Muratori, Caniggia, and Conzen have studied the role of building types, plots, streets, and blocks in the evolution of the urban form through successive iterations [18,19,20] Within this tradition, buildings, plots, streets, and blocks are identified as core morphological elements that combine to produce the urban fabric. While this approach has advanced our understanding of formal urban structures, it struggles to address the dynamic, informal practices prevalent in Global South cities, where socio-political precarity necessitates fluid, adaptive spatial uses.

Scholarly efforts in urban morphology have increasingly sought to address the discipline’s historical blind spots, particularly its limited engagement with the dynamic socio-spatial practices of the Global South. Dovey and King introduced the concept of “informal typology” in Dharavi [21], but their approach frames informality as a “problem”, overlooking the residents’ dynamic use of materials and spaces for flexible, adaptive purposes. Building on Italian School insights, Oliveira emphasizes residents’ incremental adaptations that gradually transform the urban fabric [22]; however, these Eurocentric frameworks struggle to account for contexts like Shanghai’s lilongs, where socio-spatial fluidity—such as curtains demarcating bathrooms or corridors being repurposed as communal terraces—defies formal typological categories. Recent efforts to provincialize these paradigms show promise: Duarte Cardoso, for example, adapts morphological analysis to Amazonian socio-environmental repair [17], though her regional-scale focus leaves micro-scale improvisations understudied. Meanwhile, Bianchi employs ethnography to document informal practices in European historic neighborhoods [23], yet her rich empirical work stops short of theorizing how such agency operates in Southern contexts marked by structural precarity.

These studies collectively reveal a critical gap: while urban morphology has broadened its empirical scope, its epistemological roots in Northern planning traditions limit its ability to interpret Southern urbanisms as constitutive logics rather than deviations [4]. The lilong serves as a clear example of this challenge, with its socio-spatial fluidity—such as the blurring of private/public boundaries and the incremental repurposing of corridors—calling for methodologies that move beyond Conzenian typology and the formal/informal binary. To address this, urban morphology could incorporate temporal analysis and ethnographic mapping [8], while also provincializing Northern theoretical assumptions. Such an approach would not negate existing frameworks but rather extend their analytical reach, enabling the discipline to engage more fully with the micro-political realities of Southern cities.

In this context, this paper focuses on the enduring ontological question of “whose morphology?” and seeks to re-examine the epistemological and methodological foundations of urban morphology through the lens of a “Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping” approach. Since the late 20th century, Western cartography has turned its attention to the “lived spaces” of “the other”, aiming to transcend traditional cartographic conventions by representing spaces shaped by lived experiences [24,25,26]. This emerging methodology not only strives to articulate local needs but also transforms cartography into a strategic tool for local actors to express and resolve spatial relationships. Margaret’s work on embedding narrative techniques directly into the visual variables of cartographic language [27] demonstrated significant success in depicting experiential spaces. However, it has yet to be widely applied or integrated into the production of morphological knowledge.

To effectively map resident-centered micro-morphologies and the micro-governance mechanisms they engender, traditional morphological approaches must undergo critical revision. Informed by Henri Lefebvre’s critique of everyday life, there exists a significant opportunity to integrate and advance both critical cartography and micro-urban morphology, particularly in relation to the everyday spatial practices of marginalized communities. For instance, in Shanghai’s lilong communities, residents frequently repurpose corridors and balconies for informal activities, such as creating shared spaces for relaxation or communal cooking. While these adaptations are not formally recognized in urban planning, they exemplify a form of micro-governance, where residents actively negotiate space usage through everyday interactions. In doing so, they establish flexible spatial boundaries that challenge the formal regulations governing public housing usage. Two key pathways for innovation in this domain are (1) narrative homology, which emphasizes “place” narratives centered on residents as active agents, and (2) knowledge interconnectivity, which connects local morphological knowledge embedded in daily practices. This paper proposes a resident-focused micro-morphological analytical framework, employing narrative-based analysis of spatial discourses from individual interviews to construct cartographies that represent local spatial realities.

This paper introduces an innovative resident-centered micro-morphological research methodology and demonstrates its relevance and applicability through a case study of Shanghai’s lilong neighborhoods. By utilizing narrative mapping, this study uncovers residents’ everyday practices and the spatial morphologies embedded within these practices, offering new methodological pathways for generating localized morphological knowledge. The second section reviews the existing literature on everyday practices, critical cartography, and micro-morphological studies, focusing on the core questions of “whose morphology?” and “how should morphological analysis be conducted?”. It emphasizes the need to integrate residents’ lived experiences and subjective perspectives into urban morphological research, advocating for a resident-centered analytical framework. The third section outlines the methodology itself, detailing the processes of finding, inscription, and simplification that structure the research framework. This section also demonstrates the applicability of this approach through a case study of Shanghai’s lilongs, exploring how the spatial characteristics of these historically marginalized housing forms are shaped and reshaped by everyday practices. It examines how individual residents influence the dynamic construction of lilong micro-morphologies, either facilitating or constraining these transformations through their daily interactions. The Xiangsheng Building, a lilong apartment complex in central Shanghai, is used as the core case study to illustrate the practical application of the methodology. The fourth section presents the findings from the core case study, focusing on how the processes of finding, inscription, and simplification inform the analysis of everyday practices and their spatial manifestations. The fifth section offers a conclusion, summarizing the three key steps in resident-centered morphological research (finding, inscription, and simplification) and emphasizing the role of critical cartographic narrative as a vital analytical tool. It reinterprets residents’ everyday practices, shedding light on the micro-morphological knowledge and mechanisms of urban renewal embedded in these practices. Finally, the discussion section addresses the advantages and limitations of this approach, reflecting on its broader contributions to the field of urban studies, particularly in the context of informal and adaptive urban environments.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

2.1. Everyday Practices in Shaping Urban Morphology

Henri Lefebvre, Guy Debord, and Michel de Certeau identified everyday life as a crucial arena of modern culture and society [28]. In Lefebvre’s three-volume Critique of Everyday Life, he argues that capitalism dominates the cultural and social world, necessitating an examination of alienation that views everyday life as a significant terrain of struggle [29]. Research into new or dissident forms of urban governance, through formal and informal actions and structures, highlights aspects historically neglected in urban theory and practice [14]. This focus is particularly relevant in areas characterized by extreme informality [6] and distinct social relations [8,30] in both the Global South and North.

McFarlane argue that everyday life constitutes a “set of processes with distinct geographies and rhythms [31]”, often characterized by their informality and invisibility in traditional urban studies, which shape the urban landscape and offer insights into the social dynamics and rhythms that govern urban life. Research within the emergent strand of Southern urbanism temporally emphasizes “the mundane” [32] and “ordinary/ordinariness” [33] in contrast to the spectacular, and spatially emphasizes “street-level” and “close-focus explorations”, focusing on micro-scale experiences, offering spatial and temporal approaches in research of everyday practices. Research emphasizes the importance of acknowledging daily routines and mundane concerns in urban environments [28]. These “everyday spaces” emerge naturally from daily practices, rather than being designed by architects or planners. They represent zones of social transition and offer potential for new social arrangements and forms of imagination. This approach also emphasizes everyday methods through bottom-up, process-oriented research which has a specific focus on the micro scale.

Related detailed examinations capture the lived experiences of residents and reject the given properties or meanings of materiality (such as pipes or grates), instead emphasizing “material configurations” that drive daily life [34,35]. Reflecting on subjectivity and constructing strategies that defy the official establishment, through incorporating various agencies and the importance of materiality into analyses [36], scholars address the complex “lifeworlds” and “lived vitalities” of urban spaces, resulting in a new type of urban morphology that can inform urban policy and city planning [37].

Although some [8,11,38] express concern that reducing studies of everyday life to local, micro, and descriptive methods risks falling into the trap of infinite particularism and increasing obscurity [37], Lefebvre provides a “third way” by examining the details of everyday life and their interrelation with structural dynamics [39] and through thinking about how everyday practices in specific places have significant scalar reverberations and theoretical significance. This leads to the introduction of multiple or alternative narratives of cities and city-making [38], offering insights that move seamlessly between the particular and the generalizable [37], avoiding both particularism and structural abstraction.

This article follows the third way of Lefebvre by focusing on everyday research and engaging with theories and practices of urban morphology to raise the question of resident-centered morphological research, aiming to balance ethnographic narratives of urban residents with macro-urban morphological processes.

2.2. Mapping the Residents’ Everyday Practices

Everyday space is not pre-given; it is formed by bodies, relationships, affects, forces, and conflicts—elements that are often non-represented, silenced, or oppressed [40]. These aspects remain hidden behind the shapes, esthetics, scales, or programs of traditional maps. Critical cartography seeks to reveal these overlooked elements and bring visibility to the displacements and affections that are typically suppressed in conventional mapping practices [41].

A major critique of traditional Western cartography, originating in the 1600s in Europe, is its anonymous generation and guise of scientific objectivity, despite being deeply political [42,43,44,45]. Critical cartography, emphasizing that all maps are authored and interpreted differently, reflects subjective perspectives [41] and is often supported by community residents, other development activists, artists, and new media innovators [46], thus challenging Western cartographic conventions. It reshapes maps using alternative methods—such as color, perspective, and audio—to highlight the subjectivity inherent in map-making [24]. Some cartographers enhance map symbols through techniques like color coding for emotional structure and tilted angles for viewpoint representation. Scholars categorize mapping strategies into drift [47], layering [48], game-board [49], and rhizome [50] strategies. Multi-layered structures in maps, including sound, text, and sketch layers, encode narratives and perceptions [51]. Additionally, emerging technologies enable the mapping of personal experience trajectories on digital maps using GPS and video. For example, Marie Cieri uses GPS technology to map personal travel trajectories on digital maps, overlaying these paths with historical texts, memories, and visual data to showcase an individual’s experiences and identity in specific spaces [52].

These evolving approaches to cartography challenge traditional notions of space by emphasizing subjectivity and layered narratives. Henri Lefebvre’s concept of “representations of space” provides a theoretical foundation for understanding how places, people, actions, and things intersect in the production of cartographies [15,53]. This involves processes of gathering, reworking, assembling, relating, revealing, sifting, and speculating [54] to uncover realities that would otherwise remain unseen. Margaret proposed narrative-focused experiential mapping, viewing place as a “narrative-like synthesis”, existing in a tension between being both centered and de-centered [55], encoding each day with its own narrative palette to express a sense of place [27]. Víctor focuses on mapping dissident spatial practices, using bodies, occupations, and affections to uncover usually invisible relationships between informal micro-activities and formal public spaces. These cartographic practices are linked to “ethnographic drawing” [13], as observing and drawing urban spaces from users’ perspectives rather than those of architects or planners. This approach empowers marginalized groups by giving them a voice in shaping the built environment and challenging the dominance of elitist structures of power [15].

Emphasizing subjective perspectives, combined with ethnographic drawing strategies and various visualization techniques, provides opportunities to recognize the significance of local knowledge and everyday spatial practices, far beyond relying solely on official data and physical housing surveys.

2.3. The Micro-Morphological Research on Everyday Control, Use, and Activity Practices

Research on urban morphology increasingly focuses on micro-urban morphology, broadening the scope to encompass daily practices and spatial redevelopment at the micro scale [56,57,58,59,60,61]. A fundamental role of urban morphology is to identify the repeating patterns in urban structures [20,62,63]. In this context, the term “room” is broadly interpreted as “any void formed by structures”, thereby conceptualizing a building as a specific arrangement of various room types [64]. Consequently, a building type is defined as the class of all buildings that share the same room types, quantities, and spatial arrangements.

Alterations in everyday practices intrinsically change the “typological diversity” of buildings, affecting room usage patterns and spatial arrangements through both formal and informal processes [65,66,67,68]. These changes significantly influence the formation and transformation of urban morphology. Such changes may occur through individual residents’ daily practices or through large-scale, collective adjustments by state or city institutions. The latter can transform urban models by altering everyday life within buildings rather than through physical deconstruction and reconstruction; notable examples include the communal reconstruction of Bologna and Chinese cities in the 1960s, as well as the socialist housing transformations in China during the 1950s.

Everyday practices, often more economical and less durable, lead to both formal and informal changes in property rights, building layouts, usage patterns, and resident relations, interacting with dominant modes of production, legal frameworks, and guidance systems. Formal elements of urban space are those that conform to legally recognized and institutionalized norms, including building layouts, land use patterns, and property rights, which are regulated by urban planning policies and official legal frameworks. On the other hand, informal elements refer to the adaptive, everyday practices of residents that often fall outside the scope of formal regulations. Consequently, property is not univocal; urban morphology should be identified as a physical form, a unit of land use, and a unit of control [69,70]. Several authors have highlighted the ambiguity and complex relationships between property, control, use, and form in their studies of urban form [66,71,72,73]. Alexander argues that the built environment is better understood as a network of overlapping sets, where “sets” refer to categories or systems describing different dimensions of urban space, such as formal property rights, informal spatial uses, and social control mechanisms [74]. In overlapping sets, a given element can be a member of two or more sets simultaneously, and identifying aspects does not deny overlaps but rather articulates them.

Building on Kropf’s concepts of control, use, and activity, this paper identifies two types of relationships between humans and physical forms, extending the notion of buildings beyond the plot-scale typically examined in existing studies [70,72,75,76]. While foundational studies by Muratori, Caniggia, and Conzen established rigorous methodologies for analyzing the urban fabric through buildings, plots, and streets [8,62], their analytical frameworks—even when incorporating bottom-up processes as in Oliveira’s adaptation of Italian School insights—remain constrained by Northern epistemological lenses [22].This limitation manifests in two key aspects: (1) an overreliance on technical documentation (cadastral maps, typological classifications, etc.) that privileges researcher-defined categories over voices and spatial practices of residents [31,35,77,78] and (2) the persistent formal/informal binary that misrepresents adaptive reuse as deviations rather than constitutive logics [4].

Addressing this gap, this paper introduces the concept of resident-centered morphology, exploring ethnographic approaches to capture the characteristics of everyday practices of control, use, and activity. Recognizing residents’ everyday practices as authentic data sources, this dynamic process involves multiple residents’ perspectives and encompasses interactions among hierarchical practices, from individual neighbors to the community of a single building. This highlights the necessity for urban planning policies that are adaptable and sensitive to the evolving needs and practices of urban inhabitants.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

To address the complex and often obscured socio-spatial relationships and regeneration challenges inherent in lilong housing, this study established a Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping methodology, utilizing narrative as a foundational structure. An ethnographic research approach was employed, integrating critical cartography with micro-morphological analysis to delineate a methodological framework for the finding, inscription, and simplification of everyday practices within marginalized communities. These stages—finding, inscribing, and simplifying—are inherently iterative, characterized by overlap, recursion, and mutual reinforcement.

Step 1: Finding. The finding process was approached as a collaborative effort between residents and the author, using various interview methods to explore key topics such as residents’ identities, their knowledge of the building’s history, and their everyday practices. Iterative cooperation between residents and researchers allowed for the continuous refinement of data, uncovering narratives that closely reflect the residents’ lived experiences, thereby providing critical insights into their morphological perspectives.

Step 2: Inscription. Narrative structures were inscribed onto maps within a critical cartography framework, consistent with Latour’s concept of “inscription” [79]. This process traced individual everyday practices, mapping experiential spaces that transcend purely physical spatial representation. Key decisions included whether to map individuals or groups, choose single maps or atlases, and use traditional or innovative formats, all while resolving contradictions between multiple discourses and the mismatch between experiential and physical spaces.

Step 3: Simplification. The simplification of narrative structures into morphological analysis enhanced “readability” [80] and proposed a resident-centered micro-urban morphology. Applying Kropf’s “control-use” morphological framework [57] enabled the recognition of spaces governed by residents, the identification of overlapping control and usage units, and the re-examination of the complex spatial rights and relationships embedded in everyday practices. The challenge lay in creating morphological analysis maps that were both detailed and coherent, effectively synthesizing localized knowledge of spatial rights shaped by daily practices of control and use. By better understanding the narrative-like qualities that capture specific relational structures between people and places [55], a deeper understanding of place was achieved.

3.2. The Lilong Housing Morphology in Downtown Shanghai

3.2.1. Marginalized Lilong Housing Residential Dwellings in the Center of Shanghai

Emerging as a defining residential typology, lilong houses originated from late 19th-century colonial encounters, constructed through both formal concession planning and informal rural encroachments. These neighborhoods arose to house displaced populations—foreign settlers, Taiping Rebellion refugees, and economic migrants drawn to Shanghai’s burgeoning capitalism [81]. Architecturally, they materialized a trans-cultural synthesis: British rowhouse layouts were reimagined through Jiangnan courtyard craftsmanship, creating a hybrid form that spatially encoded colonial power dynamics and local adaptation strategies [81].

Initially peripheral settlements, lilong districts gained urban centrality through Shanghai’s 20th-century spatial expansion [58]. This geographical paradox intensified their socio-economic liminality. During the concession era, lilong compounds epitomized Shanghai’s identity as a “migrant city” [82], transitioning from single-family dwellings to high-density tenements where individual rooms housed entire families. Post-1990s economic reforms accelerated this transformation: original residents relocated to modern apartments, while vacated units became subdivided rentals for low-income migrants. By 2017, central lilong neighborhoods accommodated over 800,000 residents at extreme densities (avg. 9 m2/person), sustaining their characterization as “villages within the city” [83,84].

3.2.2. Formal and Informal Everyday Practices Change Lilong Housing Morphology

The historical formalization and transformation of lilong houses have resulted in a complex socio-spatial morphology characterized by layered, overlapping, and conflicting everyday practices. During the concession period, lilong houses were initially owned by single, above-middle-class families. However, the influx of rural immigrants and declining owner incomes during wartime led to room-by-room sales, resulting in multiple owners, fragmented management, and the informal construction and use of public spaces of lilong houses [85]. During the planned economy period, the state’s expropriation and redistribution of lilong properties, granting each family a room along with shared kitchen and bathroom facilities, transformed lilong houses into organized communal living spaces through everyday control, usage, and activities. In the socialist market economy period, the State-owned housing system allowed residents to sublet, transfer, and lease their rooms indefinitely. Some residents purchased adjacent rooms, disrupting the one-room-per-family arrangement and informally occupying public spaces, thereby breaking previously homogeneous control and usage patterns.

The development and evolution of lilong compounds demonstrate that everyday practices have consistently played a crucial role in shaping these spaces, resulting in significant micro-morphological transformations over time and continuing to influence the micro-urban morphology of lilong houses today. The socio-spatial relationships within lilong buildings are complex, chaotic, and fragile, yet they are an essential part of Shanghai’s urban culture. As Amos Rapoport stated, “A house is a human fact… clearly showing the relationship between form and lifestyle” [86]. Scholars have long recognized that the everyday “marketplace” (市井) form of Shanghai’s lilongs represents their fundamental characteristics, exploring their societal form through narratives of residents’ daily lives. Existing research primarily focuses on well-known heritage buildings and significant individuals, while studies on non-heritage-listed lilong buildings and the everyday practices of their residents are scarce.

3.2.3. Micro-Morphology of Lilong Residents and Urban Regeneration Challenges

The complex control and usage rights associated with lilong buildings pose significant challenges for Shanghai’s urban regeneration efforts. Traditional strategies, such as large-scale demolitions and comprehensive preservation, often necessitate the complete relocation of residents. This process not only risks the destruction of lilongs’ living heritage but also exacerbates urban social segregation and displaces low-income rural migrants [87]. Public housing residents, who receive government compensation rather than profits, often face protracted and costly redevelopment negotiations. These negotiations are further complicated by rising land value in central Shanghai. Additionally, the high-density occupancy and informal practices of residents accelerate the deterioration of both public facilities and lilong buildings. This situation places a significant maintenance burden on the government, which is further complicated by an emphasis on social benefits and low rental income, obstructing daily maintenance, preservation, and regeneration efforts. Since 2015, Shanghai has adopted micro-renewal strategies focused on residents’ daily needs and reorganizing resources at the micro scale [87,88]. However, these studies remain predominantly case-based and lack a comprehensive methodology recognizing the micro-morphology of residents’ practices, limiting their effectiveness.

3.3. Application of the Resident-Centered Morphology: A Case Study of the Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Complex

3.3.1. Case Selection

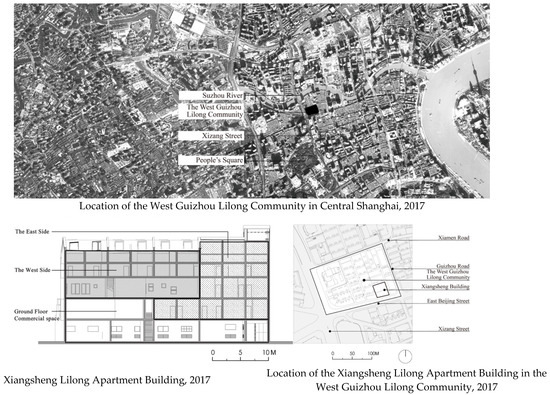

This paper introduces an innovative resident-centered micro-morphological research methodology, applied to the Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Building in Shanghai. Located in the West Guizhou Community of the East Nanjing Street subdistrict in Huangpu District, the Xiangsheng Building represents an atypical example of the lilong typology (Figure 1). Situated less than a kilometer from the commercial center at People’s Square, the West Guizhou Community stands out for its stark differences in population density, per capita residential area, income levels, and rent compared to neighboring areas, underscoring its marginal status within the city.

Figure 1.

Location of the Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Building in West Guizhou Lilong Community in Central Shanghai, 2017. Source: Authors.

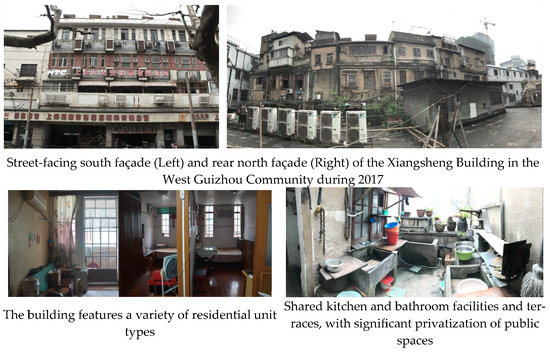

What makes the Xiangsheng Building particularly significant is its intergenerational mix of long-term residents whose everyday practices intersect with those of newer, often lower-income inhabitants. This creates a complex social fabric that reflects broader trends found in other lilong communities. Given these characteristics, the Xiangsheng Building provides a particularly rich context for exploring the relationship between residents’ spatial practices and the physical environment (Figure 2). Its ongoing transformation, both physically and socially, allows for an in-depth investigation of how marginal residents adapt to and shape their living spaces.

Figure 2.

Façade and interior of the marginal Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Building in Central Shanghai. Source: Authors.

Unlike traditional lilong housing, the building was originally designed in the concession period as a hybrid between an office building and residential spaces, with a floorplan modeled after commercial buildings. Despite its initial design, over time, it has undergone a transformation similar to that of traditional lilong buildings, evolving into a residential space where each room functions as a self-contained unit, with shared kitchen and bathroom facilities. This historical adaptation mirrors the transformation of other lilong buildings, making it a relevant case study despite its atypical origins.

3.3.2. Method

This study explores the resident-centered morphology of the Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Building through three core processes: “finding”, “inscription”, and “simplification”. Conducted between 2017 and 2018, the research involved in-depth interviews with all 34 residents, resulting in 34 maps documenting their everyday spatial practices. These maps illustrate how different social groups perceive and inhabit space, offering insights into the morphology and dynamics of marginalized apartment forms.

The research team consisted of my Ph.D. supervisor (Professor Ming Tong), myself (a Ph.D. student during the research period), five Master’s students, and two professional architects from the TM Studio architecture firm.

During the fieldwork, we adopted an open and flexible interview approach, treating the study as a collaborative effort between residents and researchers. Through iterative data collection and verification, we uncovered contradictions and ambiguities, gradually revealing the distinct aspects of each resident’s life and addressing the central question: “Whose Xiangsheng Building?”. Initial background information was gathered through a basic questionnaire.

Data collection involved note-taking, with occasional audio recordings. Interviews were conducted in teams of two to three, allowing for role adjustments as needed. After each interview, the team promptly reviewed the notes for accuracy, and weekly meetings with supervisors were held to assess progress and refine methods, ensuring a dynamic and methodologically robust process.

The interviews focused on themes such as residents’ identity, subjective perceptions, and daily practices. This flexible approach shaped the format, location, and content of each session. As the interviews progressed, a variety of dynamic conversational techniques were employed. In-depth Interviews: A total of 34 semi-structured interviews, covering 100% of the households, were conducted in residents’ homes, each lasting 60–90 min. Neighborhood Discussions: These discussions were usually initiated by the residents themselves during interviews with long-term residents. Two or three familiar neighbors would often join the conversation, contributing additional insights into daily life. Design Charrettes: My mentor team, which also leads micro-renewal practices in the community, held workshops with the neighborhood committee nearly every month. Each workshop included 3–5 resident representatives, some from the Xiangsheng Building, providing information about the building’s history and development.

In addition to interviews, we utilized several archival materials, including historical aerial photographs (1937, 1948, 1976, 2015, 2017) to track spatial transformations and incremental encroachments, architectural surveys documenting informal modifications to the building, and policy archives (2017) that documented residential usage rights and room allocations.

This combination of fieldwork and archival research provided a comprehensive understanding of the spatial dynamics and the evolving social fabric of the Xiangsheng Lilong Apartment Building.

The research team’s dual role as interviewers and participants in the community’s redevelopment project brought both advantages and challenges. Their involvement made residents more willing to participate, as many saw the interviews as part of the redevelopment process’s preliminary research. However, this also led to distortions, with some residents fabricating historical narratives about the building’s original design, claiming it should be restored to a “historic” state, a claim later disproven through digital reconstructions. This dual role also encouraged residents to share their concerns, offering valuable insights into their views on urban changes and spatial agency. For example, second-generation residents and tenants expressed anxiety about losing ownership. One resident noted, “My siblings and I are co-owners of this public housing unit. Since my situation is worse, I’ve been allowed to live here. If the renovation improves the space, my siblings will return to claim it, and I don’t want that”.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Finding Stage: Everyday Narratives Regarding “Finding” Through the Collaboration of Cartographers and Residents

The micro-morphology of Xiangsheng Building is shaped by two main groups of residents: public housing residents and tenants. Public housing residents are divided into first-generation residents, who moved in before 1949 during the concession period through purchase or lease, and second-generation residents, who were allocated housing between 1950 and 1994 under the public housing distribution system. Tenants who moved in after 1994, when lilong public housing was permitted to be rented out by public housing residents, can be categorized into three groups: transient tenants with short-term stays, kinship tenants renting through family connections, and subletting tenants who function as sublandlords. The choice of interview locations highlights differing perceptions of public and private spaces (Table 1): first-generation residents are comfortable in both, second-generation residents balance public and private spaces, and tenants rely more on the security of their units, reflecting a weaker connection to communal areas.

Table 1.

Interview formats preferred by different resident groups.

The everyday practices of public housing residents within Xiangsheng Building exhibit a pattern governed by relatively stable rules: dwelling units are fixed as communal facilities belonging to individuals, and daily pathways are predetermined. First-generation residents, having the longest tenure and the most extensive architectural knowledge, generally hold a strong sense of ownership. However, interviews reveal distinctions between former owners and tenants despite their equal public housing rights after the socialist housing reform. For instance, Resident A, whose family historically owned both interior and exterior units, continues to occupy the side corridor as family property, disregarding the needs of the tenant of a former exterior unit, Resident B, illustrating the persistence of pre-revolution landlord–tenant relationships in shaping current spatial practice. Second-generation residents’ everyday practices are shaped by assumed usage rights within communal living spaces and a tradition of sharing public areas. Gradually, the communal stoves and sinks in the shared kitchen were increasingly treated as personal property, fragmenting once-collective spaces into private zones. In contrast to the first generation of residents, second-generation residents engage with each other on more equal terms, treating historical information as casual conversation during leisure moments without sparking conflict or cognitive dissonance among neighbors.

The everyday practices of tenants within the Xiangsheng Building are typically restricted to their residences, stairwells, and corridors within the building, primarily conforming to external demands from other public housing residents. Due to the transient nature of their living situation and frequent mobility, most tenants perceive their residence as temporary, lacking a sense of community and belonging. They show minimal interest in the building’s history and prioritize concerns over potential rent increases tied to future renovation plans. Tenants generally exhibit limited ownership or engagement with public spaces, viewing their apartments as the primary secure and stable areas. This behavior is reinforced by public housing residents who have installed private kitchen and bathroom facilities within their units to increase rental prices, reducing tenants’ need to use communal facilities. Tenants who lack these amenities often rely on their landlord’s private communal kitchen and bathroom, sometimes facing verbal restrictions from public housing residents. For example, a second-generation resident was observed telling tenants “Could you please not cook at the same time as us? You could cook earlier or later; it’s very crowded. I’ll have to discuss this with your landlord. It’s inconvenient for us”. Interactions between tenants and public housing residents occur more frequently and amicably on the east side of the third floor of the Xiangsheng Building, while communication in other areas remains limited.

4.2. Results of the Inscription Stage: Simultaneous Mapping of Individual Experiential Narratives and Comprehensive Non-Experiential Space

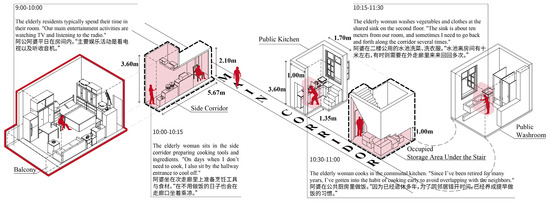

Despite the continuous nature of everyday life, individual experiences collected from interviews present a fragmented narrative, predominantly centered on a few repetitive, fixed activities. A three-dimensional cartographic approach was used to visualize these daily practices, highlighting activities such as cooking and laundry as key components in shaping residents’ cognitive mapping of their immediate environment and informing their sense of place (Figure 3). Spaces that residents identify as central to their daily routines are mapped with distinct colors and detailed features, while areas of less personal significance are left unshaded, blank, or outlined with minimal linework. The contrast between spaces shaped by residents’ daily routines and those left unformed provides key insights into how individual practices shape spatial perceptions, while the cartographic approach illustrates how these personal activities influence the configuration of residential units and the building’s form, enhancing the understanding of lived experience within a localized context.

Figure 3.

Narrative mapping of the everyday practices of the “Grandpa” who placed his reclining chair across the corridor, as mentioned in the Introduction, within the Xiangsheng Building. Source: Authors.

In the Xiangsheng Building, the daily trajectories of both first- and second-generation public housing residents are marked by stability, involving fixed living spaces spanning one or more public housing rooms, shared facilities, varying degrees of control over communal areas, and consistent daily pathways. Tenants’ daily trajectories are marked by fluidity and transience, typically limited to a single room (excluding subletting tenants who may control multiple rooms) and focused on entry and exit pathways, with varying usage of communal kitchens and bathrooms, and occasional restrictions on public space access imposed by public housing residents.

The detailed examination of residents’ daily lives and neighborhood dynamics revealed significant discrepancies in how individuals perceive their relationships with one another. A resident who holds a prominent position in one person’s cognitive map may be of little importance in another’s. To address this complexity, a narrative layer was introduced, incorporating first-person accounts through textual symbols, thus capturing conflicting information between residents and providing everyone with a distinct narrative voice. The integration of direct statements and experiential details enriched the maps, shifting from a detached “he is there” perspective to a more intimate “I am here” view, fostering a deeper personal engagement with the residents through the cartographic representation.

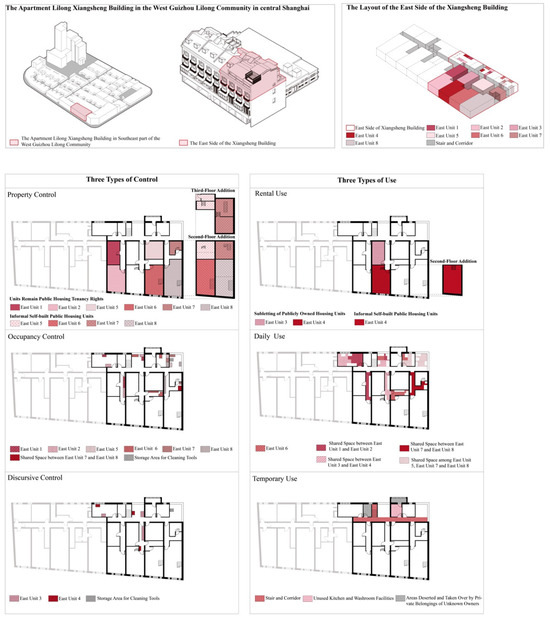

4.3. Results of the Simplification Stage: Microscopic Urban Morphological Analysis from the Perspective of Resident Dynamics

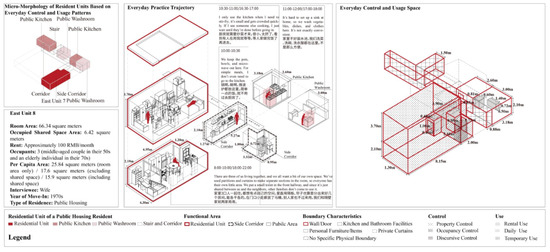

This study simplifies the cartographic representation to highlight residents’ everyday control, usage patterns, and spatial interactions within the lilong building’s floor plan. The author mapped these patterns under the category of “Residents’ Everyday Control and Usage Patterns” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Residents’ everyday control and usage patterns: example of the east part of the fourth floor of the Xiangsheng Building. Source: Authors.

“Control” in this context includes property control, occupancy control, and discursive control (Figure 4). Property control refers to ownership rights, such as selling, leasing, modifying, and using space. Occupancy control involves the use of non-owned spaces, such as public areas like kitchens or corridors, limiting access for others. Discursive control arises in public spaces where informal rules are set by residents, often targeting tenants. These forms of control frequently coexist, as seen with an elderly resident who holds property control over their room while asserting occupancy control over a corridor with a reclining chair. “Usage” refers to human activities and spatial functions, identified in three types in the Xiangsheng Building: rental use, daily use, and temporary use (Figure 4). Rental use is governed by formal contracts, giving tenants rights to lilong residential units and shared facilities, often restricted by owners or neighbors. Daily use refers to informal, non-contractual activities in units or public areas, tolerated by neighbors but subject to withdrawal. Temporary use includes non-obstructive, irregular activities like resting on the terrace or chatting with neighbors.

Through a micro-morphological analysis of residents’ everyday control and usage patterns, a resident-centered unit morphology is developed, grounded in these daily practices. The author developed a series of maps to represent individual resident units, beginning with data collection and information gathering, progressing to vivid narratives of daily life, and culminating in standardized 3D architectural drawings, all presented in Figure 5 as an example. The resident-centered unit morphology plans are shown separately in Figure 6 as an example. The use of standardized 3D drawings is essential because many residents exhibit highly segmented control over public spaces, such as shared corridors. For instance, two households might share a storage space on the same wall, with one occupying the lower shelves and the other using the upper shelves. Therefore, mapping individual resident units requires integrating both spatial data and three-dimensional representations.

Figure 5.

Micro-morphological analysis of resident units based on everyday control and usage patterns: example from the fourth floor, east unit 8 of the Xiangsheng Building. Source: Authors.

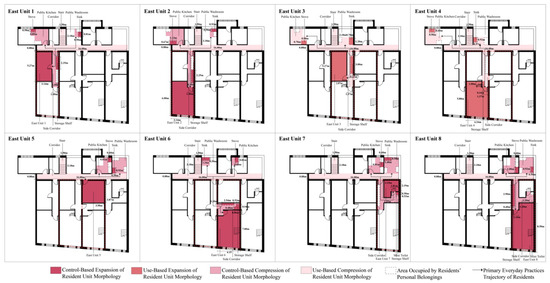

Figure 6.

Resident-centered unit morphology based on everyday control and usage: example from the fourth floor, east wing of the Xiangsheng Building. Source: Authors.

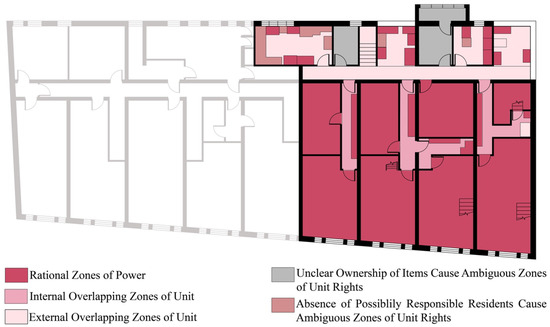

By further examining the overlapping relationships of control and usage within this lilong building, zones of rational rights distribution, overlapping rights, and ambiguous rights can be identified, illustrating the complex spatial and social dynamics embedded in these units, as shown in Figure 7 as an example. Zones of rational rights distribution include residential units and public spaces without disputes. Overlapping rights zones are either internal—where multiple property owners, such as siblings, share ownership of a room, complicating regeneration due to differing opinions—or external, where residents share spaces like corridors, enforce access through verbal rules, and install shared facilities for exclusive use, occasionally permitting close neighbors. Zones of ambiguous rights typically appear in public areas used for furniture storage or underutilized spaces like kitchens and bathrooms. These areas result from misaligned information, as seen in conflicting accounts about a stone-walled area on the fourth floor, unclear ownership of items in cluttered spaces, and the absence of responsible residents, leading to neglected areas that no one manages.

Figure 7.

Rational zones of power distribution, overlapping zones of unit rights, and ambiguous zones of unit rights in the Xiangsheng Building. Source: Authors.

5. Conclusions

The socio-spatial fluidity of marginalized urban neighborhoods demands methodologies that bridge lived experiences with morphological analysis. Through a case study of a peripheral lilong house in central Shanghai, this paper foregrounds everyday spaces—domains shaped organically by residents’ practices rather than formal design—as critical sites for resisting established spatial orders and generating micro-urban landscapes. This paper demonstrates how residents’ everyday practices reshape urban form and governance. By synthesizing Lefebvrian epistemology, narrative cartography, and rights-based typologies, this study advances three core contributions to urban morphology:

Adoption of Lefebvre’s Third Way: By emphasizing everyday research and engaging with urban morphology theories, this paper provokes an epistemological reflection on “whose morphology”, shifting the focus from perspectives centered on researchers and technologists to prioritizing residents’ everyday practices as legitimate morphological knowledge and cartographic context.

Introduction of Ethnographic Methods: By employing an ethnographic approach, this paper introduces the Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping method as a critical cartographic technique that reconfigures the methodology of morphological analysis. This shift moves from conventional Western cartographic language—defined by visual variables and grammar that convey homogeneous and modern spaces—to an alternative methodological framework informed by residents’ experiential knowledge, thereby establishing the resident-centered unit morphology based on everyday control and usage.

Investigation of the Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping Method: Central to this investigation is the development and application of the Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping method, a three-stage methodology (finding, inscription, and simplification) that integrates ethnographic research, critical cartography, and micro-morphological analysis to decode marginalized communities’ spatial practices.

Rights-Based Micro-Urban Morphology: Through examining the overlapping relationships of control and usage, this paper identifies zones of rational rights distribution, overlapping rights, and ambiguous rights, investigates the transformative potential of integrating everyday practices with the Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping method to enhance the revitalization and governance of historical neighborhoods, and emphasizes the dynamic interplay between residents’ everyday experiences and urban regeneration efforts to foster participatory governance frameworks that promote inclusive, context-sensitive strategies honoring the historical and cultural fabric of these communities.

The Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping method not only uncovers hidden socio-spatial dynamics but also repositions urban morphology as a discipline capable of engaging with Southern urbanisms on their own terms. Its application in a Shanghai lilong demonstrates how marginalized communities reshape cities through micro-practices, offering a model to integrate grassroots agency into global urban theory and inclusive governance frameworks.

6. Discussion

Since our initial in-depth investigation of the lilong compound in central Shanghai uncovered a marked divergence between residents’ property rights and their actual usage patterns, this paper stresses the need to critique and expand traditional urban morphology—typically focused on property rights and physical form—to encompass a more comprehensive understanding of the spatial realities shaped by residents’ everyday “control” and “use”, with the aim of revealing the informal and often invisible micro-morphologies that define living spaces within lilong communities. Our fieldwork conceptualizes the everyday practices of residents as a form of morphological agency, emphasizing that in the continuous reconstruction of public and private boundaries, individuals do not entirely dismiss the physical forms of urban structures or the normative usage orders established by state entities. Instead, residents’ everyday practices, shaped by institutional changes, neighborhood agreements, and individual actions, engage in the ongoing subdivision and reconfiguration of existing forms, resulting in a micro-institutional framework of morphological operations.

Utilizing the Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping method, we spatialize these data, using them as a tool to find, inscribe, and simplify the everyday practices of residents. This advancement in micro-morphological research enriches our theoretical frameworks and discussions. Furthermore, these micro-institutions of morphological operations diverge from formal regulations; rather, they represent a fabric of novel spaces defined by everyday practices. Although often fragmented and challenging to systematize, they can also serve as entry points and foundational micro-institutions for resident engagement in urban regeneration and governance.

A significant challenge encountered in this study was conducting in-depth interviews with all residents while maintaining a consistent level of detail. Although our research on Shanghai’s lilong neighborhoods benefited from the enthusiastic participation of residents—who often perceived our interviews as part of a pre-renovation assessment led by my supervisor’s team—discrepancies remained in both the quantity and quality of the information gathered. Certain interviews resulted in vague, contradictory, or exaggerated responses. Consequently, this research should not be interpreted solely as an ethnographic narrative or mapping of local residents, but rather as a collaborative “finding” process involving residents, the author, and the reader.

Undoubtedly, the transformation from physical landscapes to map representations involves a process of reduction, selection, consolidation, distortion, and exaggeration [79,89]. This process inevitably imprints the map with the intentions and knowledge of both the cartographer and the narrator. The map presented in this study features two perspectives: a close-up view, where residents detail their daily practices, resulting in small-scale, three-dimensional spatial mappings, and a broader analytical perspective from my objective cartographic approach, which encompasses large-scale representations of both three-dimensional and two-dimensional spaces. The maps produced for this project are based not on verbatim recordings of all resident interviews but rather on selectively chosen phrases that capture the essence of their everyday practices, along with the differentiated spaces I chose to highlight. The spatial morphologies and narratives are only broadly outlined by discourse and remain incomplete. Readers are required to draw upon their own experiences and interpretations to contextualize and understand the everyday practices within these homes.

Moreover, compared to studies of marginalized neighborhoods in Chinese and other cities, research on “the everyday” has become a central focus in Southern urban studies, which, rather than being defined by latitude, emphasizes areas marked by extreme informality [80] and distinctive social relations [8,30]. The everyday practice approach offers a vital framework for analyzing new or dissident forms of urban governance, expressed through both formal and informal actions and structures [14]. Extensive studies of marginalized neighborhoods within Global North cities that exhibit Southern characteristics—such as diachronic socio-spatial structures shaped by institutional changes or rapidly evolving socio-spatial structures resulting from specific industrial developments—offer valuable case studies. Employing micro-morphological approaches, such as Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping, within these studies enables a deeper understanding of the spatial dynamics shaped by everyday practices, facilitating the development of interventions that are both adapted to local conditions and responsive to the intricacies of urban socio-spatial regeneration and governance.

Future research should broaden its diachronic exploration and analysis to encompass not only individual practices but also factors such as neighborhood collaboration, community governance, and urban institutional frameworks. This expansion would enhance the development of Resident-Centered Narrative Mapping and micro-morphological studies across diverse urban scales and temporal contexts. Such research may include an investigation of how multi-layered everyday practices contribute to the continuous transformation of urban morphology.

To conclude, we argue that the details of everyday life evolve and endure with a seemingly consistent and unremarkable rhythm, and while this daily existence appears both lasting and quietly impactful, its sustained continuity holds the potential to trigger swift, widespread, and significant urban transformations. As the renowned Shanghai writer Wang Anyi captures in her reflection on the century-long transformation of the city, “Each day is filled with the simple essentials of life, lived with quiet diligence and without grand ambitions, yet upon looking back, it has quietly transformed into a legend” [90]. However, the individual everyday practices are often limited and fragile, resulting in a micro, fragmented, and vulnerable spatial realm of everyday life that can be irreversibly erased, highlighting the necessity for such spaces to be “discovered”, thoughtfully preserved, and adapted within the context of urban development.

Funding

The project is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3805503).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely appreciates the invaluable guidance and insightful comments provided by doctoral supervisor Ming Tong and D.G. Shane. Special thanks also to T. Hou and Y. Cao for their support in preparing the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oldfield, S. Critical Urbanism. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Slumdog cities: Rethinking subaltern urbanism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miraftab, F. Insurgent planning: Situating radical planning in the Global South. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.J.Z.; Kain, J.H.; Oloko, M.; Scheinsohn, M.; Stenberg, J.; Zapata, P. Residents’ collective strategies of resistance in Global South cities’ informal settlements: Space, scale and knowledge. Cities 2022, 125, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.; Rao, V. Counting the uncountable: Revisiting urban majorities. Public Cult. 2021, 33, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.M. People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg. Public Cult. 2004, 16, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabin, A. Grounding Southern City Theory in Time and Place. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, F.L.; Hernández, F. (Eds.) Spatial Concepts for Decolonizing the Americas; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Wordling the South: Toward a Post-Colonial Urban Theory. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, U. Emerging Post-Political City in Seoul. In Post-Politics and Civil Society in Asian Cities; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, V. London’s street markets: The shifting interiors of informal architecture. Lond. J. 2020, 45, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. The Post-Political City. In Urban Politics Now: Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neoliberal City; BAVO, Ed.; NAI Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Ciborro, V.; Medina, A. Invisible networks: Counter-cartographies of dissident spatial practices in La Jota Street, Quito. Cities 2023, 140, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte Cardoso, A.C. Morphological analysis as a tool for socio-environmental reparation: Contributions from the Amazon context. Urban Morphol. 2024, 28, 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi, G.; Maffei, G.; Vaccaro, P. Saverio Muratori and the Italian school of planning typology. Urban Morphol. 2002, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniggia, G.; Maffei, G. Architectural Composition and Building Typology; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis; Institute of British Geographers: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; King, R. Forms of informality: Morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V. Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, A. Beyond the plan: Informal urbanism and everyday spatial practices in historic neighborhoods. J. Urban Des. 2020, 25, 589–607. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, J. The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique, Invention. In Mappings; Cosgrove, D., Ed.; Reaktion: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kanarinka, F.A. Art-machines, body-ovens and maprecipes: Entries for a psychogeographic dictionary. Cartogr. Perspect. 2006, 53, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, K.D. Landscape Mapping and Symbolic Form: Drawing as a Creative Medium in Cultural Geography. In Cultural Turns/Geographical Turns: Perspectives on Cultural Geography; Naylor, S., Ryan, J., Cook, I., Crouch, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Margaret, W.P. Framing the Days: Place and Narrative in Cartography. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2008, 35, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cobarrubias, S.; Pickles, J. Spacing Movements: The Turn to Cartographies and Mapping Practices in Contemporary Social Movements. In The Spatial Turn: Interdisciplinary Perspectives; Warf, E.B., Arias, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Holston, J. Insurgent citizenship in an era of global urban peripheries. City Soc. 2009, 21, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A.M. The Missing People. In The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, C.; Desai, R.; Graham, S. Informal urban sanitation: Everyday life, poverty, and comparison. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2014, 104, 989–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barac, M. Place resists: Grounding African urban order in an age of global change. Soc. Dyn. 2011, 37, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M. Constructing ordinary places: Place-making in urban informal settlements in Mexico. Prog. Plan. 2014, 94, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, J. Incremental infrastructures: Material improvisation and social collaboration across post-colonial Accra. Urban Geogr. 2014, 35, 788–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirolia, L.R.; Suraya, S. Towards a Multi-Scalar Reading of Informality in Delft, South Africa: Weaving the ‘Everyday’ with Wider Structural Tracings. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A.; Cirolia, L.R. Politics/matter: Governing Cape Town’s informal settlements. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 274–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, E. Grasping the unknowable: Coming to terms with African urbanisms. Soc. Dyn. 2011, 37, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J. Cities Beyond Compare? Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. Critique of Everday Life; Verso: London, UK, 1991; p. 95. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N.; Dewsbury, J.D. Dead geographies—And how to make them live. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2000, 18, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.; Cano-Ciborro, V. Cartographies of everyday conflicts in public spaces. Informal micro-activities on formal infrastructure. Carapungo Entry Park, Quito. Rev. INVI 2022, 37, 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A. Critical cartography 2.0: From ‘participatory mapping’ to authored visualizations of power and people. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 142, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygier, J.; Crampton, J.W. An introduction to critical cartography. ACME Int. E J. Crit. Geogr. 2006, 4, 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pickles, J. A History of Spaces: Cartographic Reason, Mapping and the Geo-Coded World; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D. The Power of Maps; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; d’Auria, V. Popular cartography: Collaboratively mapping the territorial practices of/with the urban margin in Mumbai. City 2023, 27, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debord, G. Discourse on the Passions of Love: Psychogeographic Descents of Drifting and Localisation of Ambient Unities. In Psychogeographic Guide of Paris; Bauhaus Imaginiste, Ed.; Permild & Rosengreen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R.; Man, B. S,M,L,XL; Monacelli Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bunschoten, R. Proto-Urban Conditions and Urban Change. In Beyond the Revolution: The Architecture of Eastern Europe: Architectural Design Profile 119; Toy, T., Ed.; London Architectural Design: London, UK, 1996; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia; Massumi, B., Translator; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cieri, M. Between being and looking: Queer tourism promotion and lesbian social space in Greater Philadelphia. ACME 2003, 2, 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, M.P. Affecting geospatial technologies: Toward a feminist politics of emotion. Prof. Geogr. 2007, 59, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H.; Enders, M.J. Reflections on the politics of space. Antipode 1976, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, J. The agency of mapping: Speculation, critique and invention. In The Map Reader; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Entrikin, J.N. The Betweenness of Place: Towards a Geography of Modernity; Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Larkham, P.J.; Jones, A.N. The Changing Suburban Landscape in Post-War England. In Urban Landscapes: International Perspectives; Whitehand, J.W.R., Larkham, P.J., Eds.; Routicdge: London, UK, 1992; pp. 227–265. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Morton, N.J.; Carr, C.M.H. Urban Morphogenesis at the Microscale: How Houses Change. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1999, 26, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Gu, K.; Conzen, M.P.; Whitehand, S.M. The typological process and the morphological period: A cross–cultural assessment. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 512–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Tong, M. The transformation of the lilong form: A morphological study on changing boundaries. Urban Des Int 2024, 29, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisa, E. The longevity of Persian urban form: Maywood from late antiquity to the fifteenth century. Urban Morphol. 2015, 9, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Stefano, B. Morphology as the Study of City Form and Layering. In Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Bandarin, F., van Oers, R., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Moudon, A.V. Urban Morphology as an emerging interdisciplinary field. Urban Morphol. 1997, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, B.C. The epistemology of urban morphology. Urban Morphol. 2015, 20, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. Ambiguity in the definition of built form. Urban Morphol. 2013, 18, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijs, V.O. Urbanizing villages: Informal morphologies in Shenzhen’s urban periphery. J. Urban Des. 2018, 23, 732–748. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K.; van Oostrum, M.; Chatterjee, I.; Shafique, T. Towards a morphogenesis of informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijs, V.O. Appropriating public space: Transformations of public life and loose parts in urban villages. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemak. Urban Sustain. 2022, 15, 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- Çalışkan, F.; Mashhoodi, R. Typological diversity and morphological continuity in the modern residential fabric: The case of Ankara, Turkey. Habitat Int. 2023, 104, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. Aspects of urban form. Urban Morphol. 2009, 13, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K.S. Plots, property and behaviour. Urban Morphol. 2018, 22, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Good City Form; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City; Ockman, J., Ghirardo, D., Eds.; Walden, B.V.d.G., Translator; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, B. The Evolution of Urban Form: Typology for Planners and Architects; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A city is not a tree. Archit. Forum 1965, 122, 58–62 (Part I), 58–62 (Part II). [Google Scholar]

- Scheer, B. Toward a minimalist definition of the plot. Urban Morphol. 2018, 22, 162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Scardigno, N. Landscape as Forma Mentis: Interpreting the Integral Dimension of the Anthropic Space. Mongolia; Franco Agneli Edizioni: Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lemanski, C. Everyday human (in) security: Rescaling for the Southern city. Secur. Dialogue 2012, 43, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sletto, B.; Palmer, J. The liminality of open space and rhythms of the everyday in Jallah Town, Monrovia, Liberia. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2360–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together. In Knowledge and Society: Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present; Kuklick, H., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, UK, 1986; Part 6; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- James, C.S. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, Z. Lilong Architecture; Shanghai Social Science and Technology Literature Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1987; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. The Historical Transformation of Shikumen and Shanghai Identity in Mass Media. J. Univ. 2004, 4, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H. Beyond the Neon Lights—Everyday Shanghai in the Early Twentieth Century; Shanxi People’s Publishing House: Taiyuan, China, 2018; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, J. Back and Forth: Ontological Analysis on the Regeneration of Lilong in Shanghai. Hous. Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W. The Conservation and Regeneration of Shanghai Lilong; Shanghai Scientific and Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. House Form and Culture; Yang, S., Ed.; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. The Idea and Path of Establishing the Mechanism of Preserving the Urban Living Heritage: Shanghai’s Experience and Challenges in Historic Townscape Preservation. Urban Plan. Forum 2021, 06, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Li, K.; Wang, H. Spatial Revolution: Reflections on the Renovation of 0.8 Shikumen Residence. Archit. J. 2014, 2, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Tong, M. Urban Micro-Renewal: From Network to Nodes, and From Nodes to Network. Archit. J. 2020, 10, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A. The Song of Everlasting Sorrow: A Novel of Shanghai; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).