Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Science and Technology Studies: Multilevel Perspective, Actor–Network Theory, and Relational STS

2.2. Common-Pool Resources and Polycentric Governance Approaches

2.3. Social Acceptance Theory

2.4. Neo-Institutionalist Approach

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Relationships Between RECs and the Italian Energy Markets

Benetutti has never been under the wings of Enel since energy was born; so, we are talking about since the early 1900s, Benetutti has always been an energy community in this sense, that is to say, we have our entire proprietary network, so from the distribution network, remote meters, low voltage, medium voltage, we also do what we currently say is everything that is also related to the front office with the citizen user. In the sense that we also invoice electricity, exactly as a distributor does in the rest of the country.(Benetutti co-municipal official)

4.1.1. Role of Public Incentives

We had the need, due to the type of people living in the slums, to imagine energy communities that were explicitly capable of combating energy poverty. Hence the idea of creating solidarity energy communities, i.e., energy communities that are capable of mutualizing energy according to social algorithms between the nodes that promote energy communities. So, we began a research project that involved, above all, exclusively in the first phase of the journey the ITAE institute of the CNR. With them, we built this algorithm and this sort of energy hub for community management, which we are now experimenting with in Fondo Saccà, and which in the coming months will be scaled up and replicated in other parts of Sicily where the Community Foundation has its own funds and, therefore, where it develops its actions (…).

Energy, along with water, is the only good whose unit cost is undifferentiated from the income level and social and health needs of the people who use it. This lack of progressivity in the costs of essential common goods was one of the issues we wanted to address. For this reason, the energy community that we imagined and built originally needed strong action that would allow us to design and test an engineering framework and a hub management algorithm. This algorithm could allow the mutualization of energy and take into account the social needs, the health needs, and the economic needs, hence also the income level and wealth of the people who use it.

The sense of the energy community becomes first and foremost a tool to waste as little as possible the energy that is produced in a distributed manner among the homes that belong to the energy community, so the first direct objective is social. Then, the engineering hub that we created is the experimental algorithm that we built for the management of the energy community. This meets the objectives of equality, of greater progressive equality, and therefore allows progressivity in the use and tariffs of the mutualized energy that meet the criteria of equality and furthers the fight against inequality.(former secretary general of the MeSSINa Foundation)

We want to understand first, because the association can also say “we are earning EUR 1000, so let’s have the assembly and decide that EUR 500 be divided among the members and EUR 500 be spent on putting in the devices (smart meters, etc.)”. Since they (the companies, etc.) all rightly make business plans for their assets/companies and say “3% of what the REC gets with the incentives goes to us”. So, no, I mean, not yet. We want to wait for that.(Mayor of Ferla)

Our goal was not to have an economic return. Our objective was to gain a little visibility, to bring the community together. This is something that hasn’t happened for years, and to bring benefits to the town, which for many years has been neglected by the municipal administration. And not only by them, but also by us, who had become a little complacent; the town had aged a little, and not everyone was so keen on fighting or bringing innovations. Instead, this project seemed to us to be just the right thing to build work or projects around. For example, one of our goals was to restore the paths, even the military mule tracks that had gone a little bit into disrepair, because then no one was willing or had the desire. There are not many of us, but about ten of us are always there, and we do some of this work.(member/promoter of the REC of Riccomassimo)

However, the economic benefit is already there for the inhabitants of Riccomassimo, as they are members of the consortium cooperative of Storo (CEDIS), which already has its own production and gives discounts, lightening the bill, let’s say. Probably, there is less need for savings in our area. Because with the discounts, for example, that we gave in 2021, we were able to maintain the prices at the same level as in 2020, which had already been discounted by us. So, the economic part was not the objective. The idea, as she said, is to leave what will be the incentive income and reinvest it in the area. We, as a consortium, did not want to be part of the association precisely to leave the community free, as it should be, to decide on the guidelines and projects to be enhanced and put in place.(representative of CEDIS)

4.1.2. Role of Promoters

We did a lot of work on waste and went from percentages that were derisory to ones that are now hovering around 75–80%, but still it took years… Then, we started to save money. The nice thing I always say is that when you start doing this activity, which is to save money, then you generate ethical profit and economic profit. Ethical profit if you do the recycling, if you do the energy community, you take a step that is ethical, but it is also economic. This thing if you give it back to the citizens… I always say: “One good practice leads to another, you never stop”. You do one first, you generate savings, you can invest a small amount in doing another one.(Mayor of Ferla)

The first core group (of REC and social cohousing members) consists of those people who are part of and have been supported by the district through other projects, i.e., those people for whom the Fondo Saccà houses were built. They are some of the beneficiaries of the “Light is Freedom” project.(social worker/mediator)

4.2. Organizational and Participatory Forms: Similarities and Differences

- i.

- Large private energy companies such as Enel X. They operate in the national market with a commercial focus and are interested in the possibilities of expansion in the renewable energy market as an opportunity to diversify their product portfolio.

- ii.

- Third sector organizations such as cooperatives, associations, foundations such as Legambiente, ènostra, historical energy cooperatives, Solidarity & Energy ESCo, etc. They are based on a mutualistic vocation, aiming at social inclusion, environmental protection, and sustainable development of the local context.

The energy community is not something to reduce bills. It is a project that should somehow create social cohesion, thus creating an organism that perhaps comes into being with that purpose, but then ideally comes together for other things. I see it this way: the natural outlet of an energy community could be the community cooperative. Particularly in small towns, where there is a risk of depopulation and the ongoing phenomenon of impoverishment of services, it may be possible to meet other needs in a different way […] So, the idea is to create a community, especially after this pandemic that has in any case isolated and somewhat destroyed those bonds and habits that had been there before. Then, there is the environmental component. With these interventions, we save about 26 tons of CO2 per year, and it is certainly a drop in the ocean compared to what should be done. However, if each municipality had such a small energy community, multiplying it by the number of municipalities, the environmental benefits would still have quite an impact. So, the environmental component is also something that can be conveyed in a more direct way. If citizens are involved in this kind of projects, maybe they will be more careful about their consumption habits, about littering in the streets, a whole series of things that fit well with the basic idea.(Mayor of Ussaramanna)

The energy community of Naples East might seem like something abstract; on the contrary, it is something very concrete. It is something that intersects social justice and environmental justice, that is, the two main cornerstones on which Fondazione Famiglia di Maria is based, together with educating the community with regard to our daily actions.(President of Fondazione Famiglia di Maria)

It is a very empathic process, especially at the beginning. So, you try to catch the other person starting from trust coordinates that then become in the relationship very reciprocal. Gradually, the person takes you as a reference point, as a person, let’s say, also competent with respect to what their demands are because they realize that competence is something that is built in the relationship.(mediator of Fondazione MeSSInA)

You start from a basis of trust built in the first part of the Capacity project2; therefore, it becomes much easier to explain the logic. Also, because in this case, for these people, they will not be producer nodes; they will be beneficiary nodes.(President of Fondazione MeSSInA)

The mayor is a guy who cares about our small town, he always tries to do new things, useful things, above all. Let’s say, they helped us, they also helped us with the activities. He is a competent person, someone who deserves to be recognized.(Ussaramanna REC user)

This helps a lot. If there is no trust in the institutions, people do not participate, so personal knowledge did most of the work.(vice-president of the Ussaramanna REC)

We are lucky to have built a relationship of trust with the municipality over the years. That is the basis of the energy community. […] We have been lucky in the work done over the years that has allowed us to get people to say yes, to participate. […] The phase of awareness-raising of the engagement of the creation of trust, which is not something you do with a snap of your fingers.(Mayor of Ferla)

There were, in short, a series of favourable elements: the relationship with the bank […]; the fact that we then responded 100% on the potential of being able to create an energy community […] The fact that we are all local companies is also a winning point: local banks dissolved through takeovers by large groups in Sicily; Systemia, in any case, is an example of Sicilian “excellence”. This formula works well.(company owner—Acate REC)

The economic benefit is already there for the inhabitants of Riccomassimo, as they are members of the consortium cooperative of Storo, which already has its own production and gives discounts in the electricity bill. So, there is probably less need for savings in our area. […] The economic part was not the goal. The idea is to leave what will be the incentive revenue and reinvest it in the area. We, as a consortium, did not want to be part of the association precisely to leave the community free, as it should be, to decide on the guidelines and projects to be enhanced and put in place. […] Having followed us as the Storo Electricity Consortium, the aspects of application, of collection, of the relationship with GSE, even if formally in the name of the association, of the energy community configuration, we support as far as the practical part of data entry is concerned. Having, as an electricity consortium, a relationship of trust with the citizens and the community, we basically do it ourselves. We didn’t have to transfer all the knowledge of the electricity sector, which may be a bit challenging, but we took it on ourselves. It’s because we are on the ground, practically everyone knows each other personally, and then we try to operate to the members’ advantage, certainly not our own.(representative of CEDIS)

I say that if someone else had proposed this project to us, I don’t think it would have gone through.(vice-president of Association “La Buona Fonte”, REC of Riccomassimo)

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Challenges

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Gestore del Sistema Energetico (GSE) is the authority also responsible for calculating both the incentives and the reimbursement for energy not self-consumed by renewable energy plants and sold to the grid. |

| 2 | Capacity project is an urban regeneration and socioeconomic inclusion intervention led by the Municipality of Messina and the MeSSInA Foundation (https://fdcmessina.org/riqualificazione-urbana/capacity/, accessed on 30 October 2024). |

References

- Scheidel, A.; Sorman, A.H. Energy transitions and the global land rush: Ultimate drivers and persistent consequences. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenneti, K.; Day, R.; Golubehiko, O. Spatial justice and the land politics of renewables: Dispossessing vulnerable communities through solar energy mega-projects. Geoforum 2016, 76, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, H.S.; Boer, R. Battle over the sun: Resistance, tension, and divergence in enabling rooftop solar adoption in Indonesia. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 71, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantál, B.; Frolova, M.; Liñán-Chacón, J. Conceptualizing the patterns of land use conflicts in wind energy development: Towards a typology and implications for practice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 95, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S. Triggering resistance: Contesting the injustices of solar park development in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 86, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Devine-Wright, P. Community renewable energy: What should it mean? Energy Policy 2008, 36, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteman, M.; Wiering, M.; Helderman, J.K. The institutional space of community initiatives for renewable energy: A comparative case study of the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2014, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judson, E.; Fitch-Roy, O.; Pownall, T.; Bray, R.; Poulter, H.; Soutar, I.; Lowes, R.; Connor, P.M.; Britton, J.; Woodman, B.; et al. The centre cannot (always) hold: Examining pathways towards energy system de-centralisation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 118, 109499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R.; Feenstra, M. Do renewable energy communities deliver energy justice? Exploring insights from 71 European cases. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J.; Cantoni, R. Energy transitions from the cradle to the grave: A meta-theoretical framework integrating responsible innovation, social practices, and energy justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulecki, K. Conceptualizing energy democracy. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulecki, K.; Overland, I. Energy democracy as a process, an outcome and a goal: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldpausch-Parker, A.M.; Endres, D.; Peterson, T.R.; Gomez, S.L. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Energy Democracy, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A. To what extent can community energy mitigate energy poverty in Germany? Front. Public Health 2022, 4, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreno-Rodriguez, A.; P Ramallo-Gonzàlez, A.; Chinchilla-Sànchez, M.; Molina-Garcíac, A. Community energy solutions for addressing energy poverty: A local case study in Spain. Energy Build. 2023, 296, 113418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, C.; Guilherme, P.L.; Esther, M.G.; Swantje, G.; Stephen, H.; Lars, H. Regulatory challenges and opportunities for collective renewable energy prosumers in the EU. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, A.; D’Angola, A. Review of Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Scope, Progress, Challenges, and Recommendations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouicer, A.; Meeus, L. The EU Clean Energy Package, European University Institute (EUI) Technical Report; European University Institute: Florence, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wolsink, M. Social acceptance revisited: Gaps, questionable trends, and an auspicious perspective. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 46, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, M.; Di Nucci, M.R.; Caldera, M.; De Luca, E. Mainstreaming community energy: Is the renewable energy directive a driver for renewable energy communities in Germany and Italy? Sustainability 2022, 14, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarpani, E.; Piselli, C.; Fabiani, C.; Pigliautile, I.; Kingma, E.J.; Pioppi, B.; Pisello, A.L. Energy Communities Implementation in the European Union: Case Studies from Pioneer and Laggard Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vidovich, L.; Tricarico, L.; Zulianello, M. Community Energy Map. Una Ricognizione delle Prime Esperienze di Comunità Energetiche Rinnovabili; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, M.; Maggio, G.; D’Aleo, E.; Nicita, A. Three case studies to explore relevant features of emerging energy communities in Italy. Renew. Energy 2023, 210, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, M. Participatory practices in energy transition in Italy. For a co-productive, situated and relational analysis. Fuori Luogo 2022, 13, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, N.; Carrosio, G. Understanding the Energy Transition; Civil Society, Territory and Inequality in Italy, Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cilio, D.; Zulianello, M.; Rollo, A.; Angelucci, V. Promotion and Governance of Renewable Energy Communities: Models, implications, and critical issues. Cult. Della Sostenibilità 2024, 33, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, M. Community energies in South Tyrol: The current situation between favourable historical and institutional factors and the critical relations with the market. Cult. Della Sostenibilità 2024, 33, 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Farinella, D.; Cucinotta, G.; D’Aleo, E. Energy communities in Southern Italy: Paths for sustainable socio-territorial development? Cult. Della Sostenibilità 2024, 1, 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Park, J.J.; Smith, A. A thousand flowers blooming? An examination of community energy in the UK. Energy Policy 2013, 61, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social acceptance of renewable energy innovation: An introduction to the concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioba, A.; Giannakopoulou, A.; Struthers, D.; Stamos, A.; Dewitte, S.; Fróes, I. Identifying key barriers to joining an energy community using AHP. Energy 2024, 299, 131478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. Community action for sustainable housing: Building a low-carbon future. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7624–7633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Gotchev, B. When Energy Policy Meets Community: Rethinking Risk Perceptions of renewable Energy in Germany and the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóci, G.; Vasileiadou, E. Let’s do it ourselves” Individual motivations for investing in renewables at community level. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Devine-Wright, P.; Hunter, S.; High, H.; Evans, B. Trust and community: Exploring the meanings, contexts and dynamics of community renewable energy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2655–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasch, J.; van der Grijp, N.M.; Petrovics, D.; Palm, J.; Bocken, N.; Darby, S.J.; Barnes, J.; Hansen, P.; Kamin, T.; Golob, U.; et al. New clean energy communities in polycentric settings: Four avenues for future research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waal, E.; van der Windt, H.J.; van Oost, E.C.J. How Local Energy Initiatives Develop Technological Innovations: Growing an Actor Network. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauwens, T.; Defourny, J. Social capital and mutual versus public benefit: The case of renewable energy cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, G. Energia democratica: Esperienze di partecipazione. Aggiorn. Soc. 2017, 2, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Coletta, G.; Pellegrino, L. Optimal design of energy communities in the Italian regulatory framework. In Proceedings of the AEIT International Annual Conference, Milan, Italy, 4–8 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abba, I.; Minuto, F.D.; Lanzini, A. Feasibility analysis of a multi-family house energy community in Italy. Smart Innov. Syst. Technol. 2021, 178, 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- Cielo, A.; Margiaria, P.; Lazzeroni, P.; Mariuzzo, I.; Repetto, M. Renewable Energy Communities business models under the 2020 Italian regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pizzo, A.; Montesano, G.; Papa, C.; Artipoli, M.; Di Napoli, M. Italian energy communities from a DSO’s perspective. In Energy Communities: Customer-Centered, Market-Driven, Welfare-Enhancing; Löbbe, S., Sioshansi, F., Robinson, D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- Zatti, M.; Moncecchi, M.; Gabba, M.; Chiesa, A.; Bovera, F.; Merlo, M. Energy communities optimization in the Italian framework. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, M.L.; Ippolito, M.G.; Sanseverino, E.R.; Sciumè, G.; Vasile, A. Energy self-consumers and renewable energy communities in Italy: New actors of the electric power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignani, A.; Gozzellino, M.; Sciullo, A.; Padovan, D. Community cooperative: A new legal form for enhancing social capital for the development of renewable energy communities in Italy. Energies 2021, 14, 7029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglia, F.; Marrasso, E.; Samanta, S.; Sasso, M. Addressing energy poverty in the energy community: Assessment of energy, environmental, economic, and social benefits for an Italian residential case study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vidovich, L.; Tricarico, L.; Zulianello, M. How can we frame the energy communities’ organisational models? Insights from the “Research Community Energy Map” in the Italian context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrosio, G.; De Vidovich, L. Transizione ecologica e comunità energetiche nel policentrismo territoriale. In L’altra Faccia Della Luna; Monaco, F., Tortorella, W., Eds.; Rubbettino: Soveria-Mannelli, Italy, 2022; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S.; Foxon, T.J.; Bolton, R. Financing the civic energy sector: How financial institutions affect ownership models in Germany and the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 12, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Minervini, D.; Scotti, I. Understanding energy commons. Polycentricity, translation and intermediation. Rass. Ital. Di Sociol. 2018, 2, 343–369. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N.; Cittati, V.M. Combining the multilevel perspective and socio-technical imaginaries in the study of community energy. Energies 2022, 15, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielig, M.; Kacperski, C.; Kutzner, F.; Klingert, S. Evidence behind the narrative: Critically reviewing the social impact of energy communities in Europe. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 94, 102859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölsgens, R.; Lübke, S.; Hasselkuß, M. Social innovations in the German energy transition: An attempt to use the heuristics of the multi-level perspective of transitions to analyze the diffusion process of social innovations. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. On actor-network theory. A few clarifications plus more than a few complications. Soz. Welt 1996, 47, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. On recalling ANT. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 47, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Technology is society made durable. In A Sociology of Monsters: Essays on Power, Technology and Domination; Law, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Callon, M. Don’t Throw the Baby Out with the Bath School! A reply to Collins and Yearley. In Science as Practice and Culture; Pickering, A., Ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M. Some elements of a sociology of translation: Domestication of the scallops and the fishermen of the St Brieuc Bay. In Power, Action and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge? Law, J., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; pp. 196–223. [Google Scholar]

- van der Schoor, T.; van Lente, H.; Scholtens, B.; Peine, A. Challenging obduracy: How local communities transform the energy system. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Bellamy, R.; Pallett, H.; Hargreaves, T. A systemic approach to mapping participation with low-carbon energy transitions. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Pallett, H.; Hargreaves, T. Ecologies of participation in socio-technical change: The case of energy system transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 42, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Kearnes, M. (Eds.) Remaking Participation: Science, Environment and Emergent Publics; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chilvers, J.; Longhurst, N. Participation in Transition(s): Reconceiving Public Engagements in Energy Transitions as Co-Produced, Emergent and Diverse. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. A General Framework for Analyzing Sustainability of Socio-Ecological Systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A.; Huitema, D.; Schoenefeld, J.; van Asselt, H.; Forster, J. Governing Climate Change Polycentrically. Setting the Scene. In Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? Jordan, A., Huitema, D., van Asselt, H., Forster, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens, T.; Devine-Wright, P. Positive energies? An empirical study of community energy participation and attitudes to renewable energy. Energy Policy 2018, 118, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Haxeltine, A. Growing grassroots innovations: Exploring the role of community-based initiatives in governing sustainable energy transitions. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2012, 30, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, A.; Sijm, J.; Faaij, A. A systemic approach to analyze integrated energy system modeling tools: A review of national models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, G.R. Polycentricity and Adaptive Governance. In Proceedings of the 15th biannual International Conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons, Edmonton Canada, 25–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. Fashion in organizing. In Global Ideas: How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in the Global Economy; Czarniawska, B., Sevón, G., Eds.; Liber/CBS: Malmö, Sweden; Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Trigilia, C. Why the Italian Mezzogiorno did not Achieve a Sustainable Growth. Social Capital and Political Constraints. Cambio 2012, 2, 137–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Musolino, M.; Viganò, F. A model of urban and socio-technical participation. Between deliberative democracy and strong governance. The case of the city of Messina. Land 2023, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, M. “Non abito a Maregrosso”: Stigmatizzazione territoriale in una baraccopoli post terremoto”. Cambio 2021, 11, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball sampling. Sociol. Res. Methods 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Giulietti, M. Competition in electricity markets: International experience and the case of Italy. Util. Policy 2005, 13, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanico, F. Concentration in the European electricity industry: The internal market as solution? Energy Policy 2007, 35, 5064–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovcis, D.; Huitema, D.; Jordan, A. Polycentric energy governance: Under what conditions do energy communities scale? Environ. Policy Gov. 2022, 32, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terna. Dati Statistici Sull’energia Elettrica in Italia 2022; SISTAN: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Terna. Rapporto Mensile Sul Sistema Elettrico Dicembre 2023; SISTAN: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, N.; Osti, G. Does civil society matter? Challenges and strategies of grassroots initiatives in Italy’s energy transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudka, A.; Moratal, N.; Bauwens, T. A typology of community-based energy citizenship: An analysis of the ownership structure and institutional logics of 164 energy communities in France. Energy Policy 2023, 178, 113588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Nested externalities and polycentric institutions: Must we wait for global solutions to climate change before taking actions at other scales? Econ. Theory 2012, 49, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondazione di Comunità di Messina. Sviluppo è Coesione e Libertà. Il Caso del Distretto Sociale Evoluto di Messina; Parco Horcynus Orca; Effegieffe: Messina, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, L.; Giunta, G.; Giunta, M.; Marino, D.; Giunta, A. Urban Regeneration through Integrated Strategies to Tackle Inequalities and Ecological Transition: An Experimental Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Hansen, P.; Kamin, T.; Golob, U.; Musolino, M.; Nicita, A. Energy communities as demand-side innovators? Assessing the potential of European cases to reduce demand and foster flexibility. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 93, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medved, P.; Golob, U.; Kamin, T. Learning and diffusion of knowledge in clean energy communities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2023, 46, 100701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J. Public participation and energy system transformations. In Routledge Handbook of Energy Democracy; Feldpaush-Parker, A.M., Endres, D., Rai Peterson Stephanie, T., Gomez, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, B.; Dunphy, N.; Gaffney, C.; Revez, A.; Mullally, G.; O’Connor, P. Citizen or consumer? Reconsidering energy citizenship. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2020, 22, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law 28 February 2020, n. 8. Available online: https://climatepolicydatabase.org/policies/law-28-february-2020-n-8-italy-2020 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Hargreaves, T.; Hielscher, S.; Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delicado, A.; Iglesias, R.; Ghislanzoni, M.; Truninger, M.; Pereira, C.; Roque, R.; Sá Couto, J.; Macca, G.; de Benedictis, C.; Ferreira, V.; et al. WP5 Report: Renewable Energy Communities in Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece; Planning and Engagement Arenas for Renewable Energy Landscapes—Pearls; H2020-MSCA-Rise-2017—778039. Available online: https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/bitstream/10451/64958/1/ICS_ADelicado_MTruninger_RRoque_VFerreira_AHorta_WP5.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

| Criterion | Description |

|---|---|

| Territorial marginality | Selection of RECs located in Southern rural or urban areas affected by economic and social marginalization. |

| Small experimental initiatives | Experimental RECs started after the first national law (No. 8/2020), which imposed a connection to the secondary transformation cabin and did not allow an increase in the size of the community. |

| Localization in urban vs. rural areas | Selection of cases in both rural and urban settings. |

| Kind of promoters | Selection of different cases depending on the type of promoters: mainly municipalities, but also private foundations. |

| Prevalent membership status | Selection of RECs made up of citizen users only; mixed users (citizens and businesses); businesses only. |

|

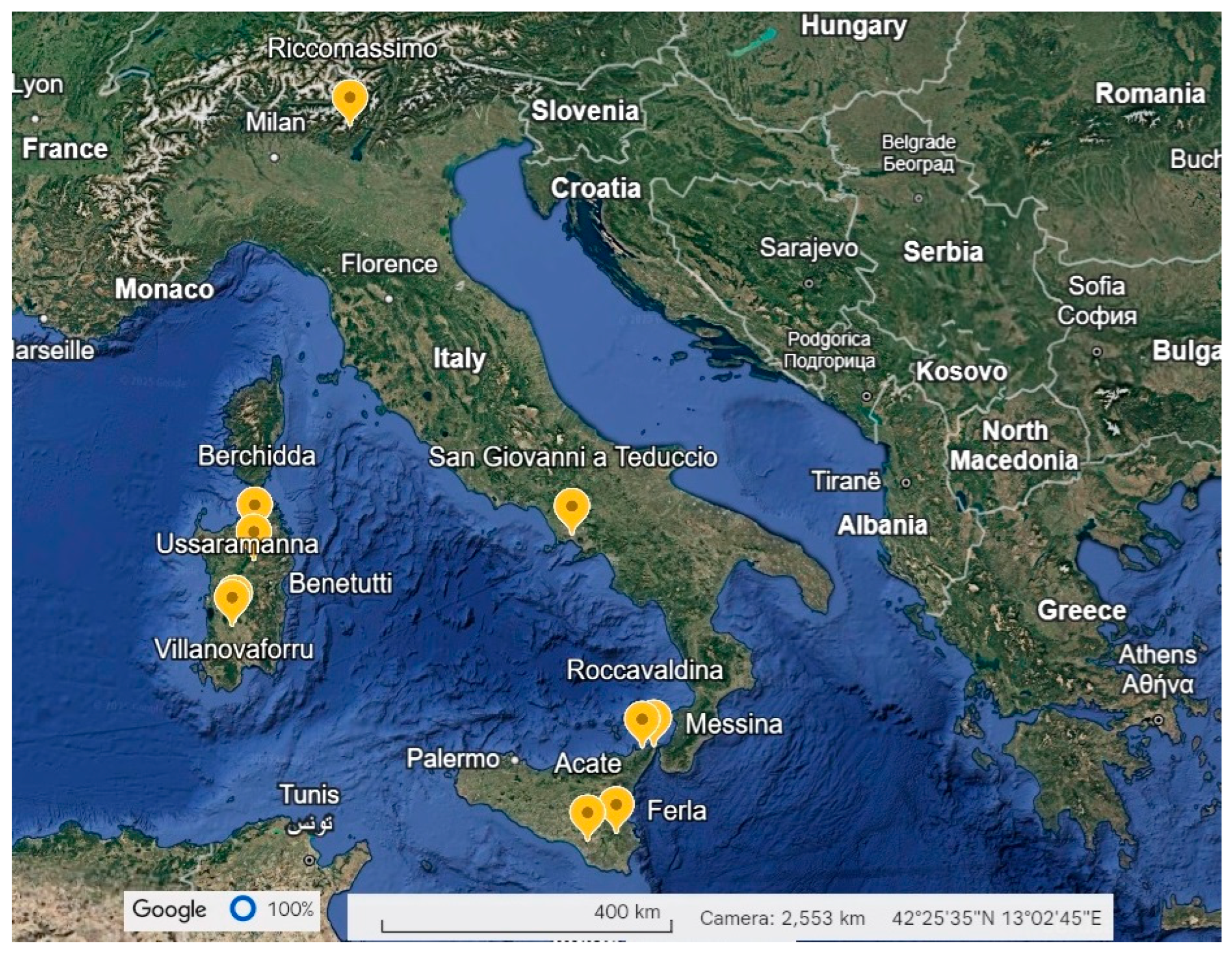

| Region | REC Name, Place, Area | Inhabitants | REC Members | Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sicily | Fondo Saccà (Messina), urban | 250 (222.329) | 4 families | 8 (including 4 REC members) |

| Roccavaldina (Messina), rural | 982 | 70 families (provisional) | 121 questionaries (TSR® participatory method) | |

| Ferla (Syracuse), rural/urban | 2305 | 5 families 2 enterprises | 6 (including 2 REC members) | |

| Acate (Ragusa), rural | 11,182 | 3 agricultural enterprises (part of the same family) | 4 (including 2 REC members) | |

| Sardinia | Villanovaforru (Cagliari), rural | 636 | 45 families 2 enterprises | 8 (including 2 REC members) |

| Ussaramanna (Cagliari), rural | 512 | 60 families 3 commercial enterprises | 14 (including 2 REC members) | |

| Berchidda (Sassari), rural | 2668 | About 30 (provisional) | 4 | |

| Benetutti (Sassari), rural | 1737 | To be determined | 4 | |

| Trentino–Alto Adige | Ricomassimo (Storo–Trento), rural | 4511 | 30 families | 14 (including 7 REC members) |

| Campania | Naples East (San Giovanni a Teduccio–Napoli), urban | 23,839 | 20 families (expected in coming years: 40) | 4 |

| REC Name | Legal Form | Technical Actors | Technology and Power | Ownership of the Plants | Ownership of the Local Grid | Investors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fondo Saccà | Association | Solidarity & Energy ESCo (technical project) CNR ITAE (for storage and social algorithm) Enel X (supplier) | PV, storage, social algorithm, smart meters: 20 kW | Fondazione MeSSInA | Natural monopoly | Fondazione MeSSInA (NGO) Solidarity & Energy ESCo |

| Roccavaldina | To be determined | Solidarity & Energy ESCo CNR ITAE (for storage and social algorithm) Enel X (supplier) | PV, storage, social algorithm: 120 kW | Fondazione MeSSInA | Natural monopoly | Fondazione MeSSInA (NGO) Solidarity & Energy ESCo |

| Ferla | Association | Municipality (technical project) | PV: 20 kW | Municipality | Natural monopoly | Municipality |

| Acate | Association | Systemia srl (technical project) | PV: 200 kW | Local companies | Natural monopoly | Local bank |

| Villanovaforru | Association | ènostra (technical project/supplier) | PV, storage, smart meters: 44.3 kW | Municipality | Natural monopoly | Municipality |

| Ussaramanna | Association | ènostra (technical project/supplier) | PV, storage, smart meters: 11 kW (municipality), 40 + 20 kW (CAS) | Municipality | Natural monopoly | Municipality |

| Berchidda | To be determined (community cooperative) | Department of Engineering, Energy4com (technical project) Municipality (supplier) | PV, smart grid, smart community: 20–25 kW | Municipality (that is also a local energy supplier) | Municipality | Municipality |

| Benetutti | To be determined (association) | Department of Engineering, Energy4com (technical project) Municipality (supplier) | PV: to be determined | Municipality (that is also a local energy supplier) | Municipality | Municipality |

| Riccomassimo | Association | CEDIS (technical project/supplier) | PV: 17 kW | REC | CEDIS (historical energy cooperative) | CEDIS |

| Naples East | Association | 3E company (technical partner) | PV, storage: 55 kW (PV) + 10 kW (storage) | Fondazione Famiglia di Maria (NGO) | Natural monopoly | Fondazione con il Sud (NGO) Public incentives |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musolino, M.; Farinella, D. Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy. Land 2025, 14, 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030603

Musolino M, Farinella D. Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy. Land. 2025; 14(3):603. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030603

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusolino, Monica, and Domenica Farinella. 2025. "Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy" Land 14, no. 3: 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030603

APA StyleMusolino, M., & Farinella, D. (2025). Renewable Energy Communities as Examples of Civic and Citizen-Led Practices: A Comparative Analysis from Italy. Land, 14(3), 603. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14030603