1. Introduction

What visual features make cities more distinctive and recognizable? The mystery above is central to sustaining urban identity and therefore ensuring the long-term socio-environmental sustainability of urban life. Cities are significant to urban identity and the sustainability of the social environment because they act as major catalysts in shaping cultural narratives, lived experiences, and communal spaces. In this context, socio-environmental sustainability refers to the capacity of urban environments to support not only ecological stability but also socially resilient communities. It encompasses elements such as cultural continuity, social cohesion, equitable access to shared spaces, and residents’ long-term sense of belonging—factors that are directly influenced by the distinctiveness and recognizability of the urban landscape [

1,

2]. Urban characteristics—ranging from architectural elements and historic landmarks to the design of public spaces and participatory planning practices—collectively influence community attachment, social cohesion, and inclusive urban governance [

3,

4,

5]. However, increasing globalization introduces tensions between standardized, efficiency-driven urban design and the preservation of culturally specific architectural forms. This trend has led to growing urban homogenization, where modern developments often neglect regional identities and local traditions, weakening both urban identity and socio-environmental resilience [

6,

7].

Streets play a central role in shaping urban identity and sustaining socio-environmental well-being. As critical public spaces, they host daily social interactions and connect individual experience to the collective image of the city. Human-centered street design—characterized by generous sidewalks, shaded corridors, and visually coherent façades—encourages walking, social encounters, and inclusive urban life [

8]. Empirical studies confirm that distinctive and well-designed streets enhance community engagement, safety, and attachment while preserving local character and environmental quality [

9]. Placemaking strategies that reclaim streets as communal realms reinforce both urban identity and resilience, underscoring the street’s role as a vital link between perception, culture, and sustainability.

Environmental judgments, such as distinguishing one street from other similar ones are usually fast. Human brains are always collecting information from environment, predicting and planning actions. Cognitive theories have shifted from a stimuli-and-response view, where behavior is seen as a simple reaction to individual environmental stimuli, to a predictive mode that rapidly collect environmental information, and make judgement or plan potential actions [

10]. Such cognitive judgements, such as deciding whether a certain image was taken on a street or not, are made very quickly, usually within a couple of seconds or even less, and may not always come with explicit explanations [

11]. Therefore, knowing what information has been paid attention to during the short time window when human beings are making fast decisions becomes crucial.

More recently objective methods such as eye-tracking and machine learning help revealing the fast judgment process, examining the functional roles of visual mechanisms in street recognition. These methods have provided significant insights into how specific visual features, such as building designs and signage, impact navigation and perceived urban identity [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Eye-tracking, in particular, has proven valuable for objectively assessing visual attention and processing strategies, providing detailed data on how visual information is integrated during scene recognition tasks [

16,

17].

At the cognitive and perceptual level, the human visual system processes complex scenes by extracting information across different spatial frequencies. Spatial frequency is defined by the frequency of transitions between light and dark areas over space, reflecting the level of visual detail [

18]. Studies in cognitive and neuroscience have demonstrated that neurons in the visual cortex selectively respond to specific spatial frequencies, facilitating the extraction of both global and local features from scenes [

19,

20]. Low spatial frequencies (LSF) generally convey global scene characteristics such as broad shapes and general layouts, whereas high spatial frequencies (HSF) capture finer details including edges, textures, and specific structural elements. Early studies by Lamb and Yund [

21] emphasized the complementary roles of global and local information in recognizing complex, hierarchically structured environments. Similarly, Berman et al. [

22] connected scene naturalness perception to low-level visual features, highlighting their fundamental role in cognitive processing.

In the context of this study, low-level visual features are perceptual attributes processed at early stages of visual analysis, before object-level or semantic interpretation. They typically include spatial frequency, luminance and contrast gradients, edges and contours, texture patterns, and color [

23,

24]. These features provide the foundational information that allows rapid extraction of a scene’s overall layout or “gist,” even when fine details or semantic cues are absent [

25]. In urban street images, low spatial frequencies (LSF) capture broad structural layout, such as the arrangement of buildings, street width and depth, skyline silhouettes, and major massing relationships. High spatial frequencies (HSF) encode fine architectural details, including façades, signage, window frames, and decorative elements [

24]. Texture or orientation distributions reflect surface patterns on buildings or pavements, contributing to the material character of the street, while color highlights contrasting façades, shopfronts, street furniture, sky, or greenery, aiding rapid differentiation of streets before conscious identification of landmarks [

23]. In this paper, we focus primarily on LSF, HSF, and color as the key low-level visual features, representing complementary dimensions of perceptual information: global structure versus local detail, and chromatic information.

In addition to their fundamental role in visual cognition, low-level visual features also shape how people perceive and evaluate urban streets. Studies show that images containing naturalistic spatial frequency patterns are generally preferred and can enhance perceptions of naturalness within urban environments [

16,

26]. Urban settings that incorporate low-level visual properties resembling natural patterns—such as façade textures or vegetation—are often perceived more positively, with natural elements like trees and plants being associated with enhanced feelings of safety, liveliness, and beauty [

27].

Color, another key low-level feature, also significantly influences people’s emotional and cognitive impressions of urban streets. Bright colors can enhance perceived vibrancy and playfulness, while excessively low brightness may reduce attractiveness and safety [

28]. At the same time, high color saturation may increase the perception of boredom, and very low brightness can diminish the perceived vitality of urban environments [

29]. In addition, color similarity and balance contribute positively to street evaluation, even though color compatibility does not necessarily influence perceptions of wealth or safety [

30].

Despite extensive research on spatial frequencies in object and face recognition, the role of spatial frequency information in street recognition remains relatively underexplored. Urban streets, as complex visual stimuli, provide an ideal context to examine how spatial frequencies contribute to visual recognition, ranging from large-scale elements like building facades and road layouts to finer details like signage and architectural ornamentation. Previous studies suggest that LSF is crucial for grasping the overall layout of streets, while HSF is essential for identifying specific architectural details [

31,

32]. Recent studies have further emphasized the significance of visual cues, including spatial frequencies, in landscape perception and urban space renewal [

33].

In parallel, the rapid recognition of scenes (scene gist) relies heavily on low-level visual features, particularly spatial frequencies and color, to quickly convey the overall meaning and context of an environment [

34,

35]. Studies have demonstrated that humans can accurately extract gist information within milliseconds, enabling efficient categorization and recognition of environments [

36,

37]. Color specifically enhances rapid recognition and memory retention of scenes, though its impact varies depending on the context, being especially beneficial in natural environments [

38,

39]. Among these low-level features, spatial frequencies are fundamental, as the visual system relies on processing patterns of orientation and frequency across the scene to rapidly extract its global structure and layout [

40]. Beyond color and spatial frequency, luminance contrast is another critical element, where higher contrast between objects and the background significantly improves detection and recognition performance [

41].

Nonetheless, few studies have systematically investigated how these low-level visual properties influence the recognition of specific urban streets. Given the importance of street distinctiveness in fostering place identity and supporting socio-environmental sustainability, understanding the perceptual mechanisms underlying rapid street recognition is crucial. This study aims to address this gap by systematically manipulating key visual features in controlled visual stimuli, utilizing Huaihai Road in Shanghai, China, as a representative case. Moreover, as trees constitute a typical feature of urban streets, prior research has suggested that natural foliage attracts fewer visual fixations [

42]. Therefore, this study also investigates the influence of the presence or absence of trees on street recognition.

Based on these considerations, the study addresses the following research questions:

1. How do low-level visual properties (spatial frequencies and color) influence recognition accuracy in rapid street identification?

2. How do low-level visual properties shape participants’ viewing strategies during rapid street recognition?

3. What fixation patterns emerge when participants recognize a specific street under different visual conditions?

4. How does the presence of trees influence recognition accuracy and viewing behavior in rapid street identification?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 51 participants were initially screened for their suitability for eye-tracking experiments. Based on the criterion that the gaze sample percentage must be at least 50% [

43], 48 participants were selected. Three participants were later excluded due to missing eye-tracking data for certain images (each with an average rate of missing samples ≥5%). The final sample included 45 participants (23 university students and 22 local community residents).

The sample size of this study was based on the effect sizes of existing studies on rapid scene recognition. As reported in a prior study [

44], the impact of low spatial frequency visual features on scene recognition revealed a large effect size of 1.47 (minimal sample size = 9, calculated in G*Power 3.1 using an a priori scenario). To enable meaningful eye-tracking analysis, we also considered studies examining fixation behavior during low-frequency scene processing [

16], which reported an effect size of 1.13 (minimal sample size = 14). Therefore, we decided on a sample size of 51 participants, to ensure sufficient power for both behavioral and eye-tracking analyses. The larger sample size also helped to mitigate data variability associated with eye-tracking recordings and ensured more robust estimates of visual processing during rapid scene recognition.

Participants were recruited via university and community channels, including flyers, emails, and direct outreach to student and resident groups. All participants were fully informed of the experimental objectives and provided written informed consent, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji University (no. tjdxsr011), ensuring compliance with internationally recognized ethical standards for research on human subjects.

The participants ranged in age from 21 to 62 years (M = 34.36, SD = 12.88), ensuring a wide age distribution to facilitate a generalizable understanding of how different age groups process visual stimuli in urban street environments. The sample comprised 22 males and 23 females, resulting in a gender ratio of 0.96:1 (male to female).

Participants’ myopia was controlled to ensure that refractive errors in both eyes did not exceed 600 diopters. This criterion was established to minimize variability in visual acuity, which could otherwise influence the processing of fine visual details [

45].

To reflect a diverse cross-section of backgrounds, half of the participants were university students, and the other half were community residents of Shanghai, representing a variety of professions such as office workers, educators, and retirees. This diversity was intentional, as it accounted for potential differences in street recognition and visual processing, possibly influenced by varying degrees of familiarity with urban environments. Efforts were also made to balance long-term residents with recent arrivals to control for any biases related to familiarity with Huaihai Road. Participants were compensated either with monetary payments or participation credits (for students), with compensation standardized across both groups to maintain consistent motivation levels.

2.2. Stimuli

To systematically explore the effects of low-level visual features on street recognition, this study utilized a carefully selected and manipulated set of visual stimuli. Huaihai Road was chosen as the primary study site due to its status as a quintessential tree-lined commercial street and a landmark urban symbol reflecting Shanghai’s distinct character. Located within a designated historic-cultural conservation area, Huaihai Road holds significant heritage value, making its recognition patterns particularly relevant for future conservation and enhancement efforts.

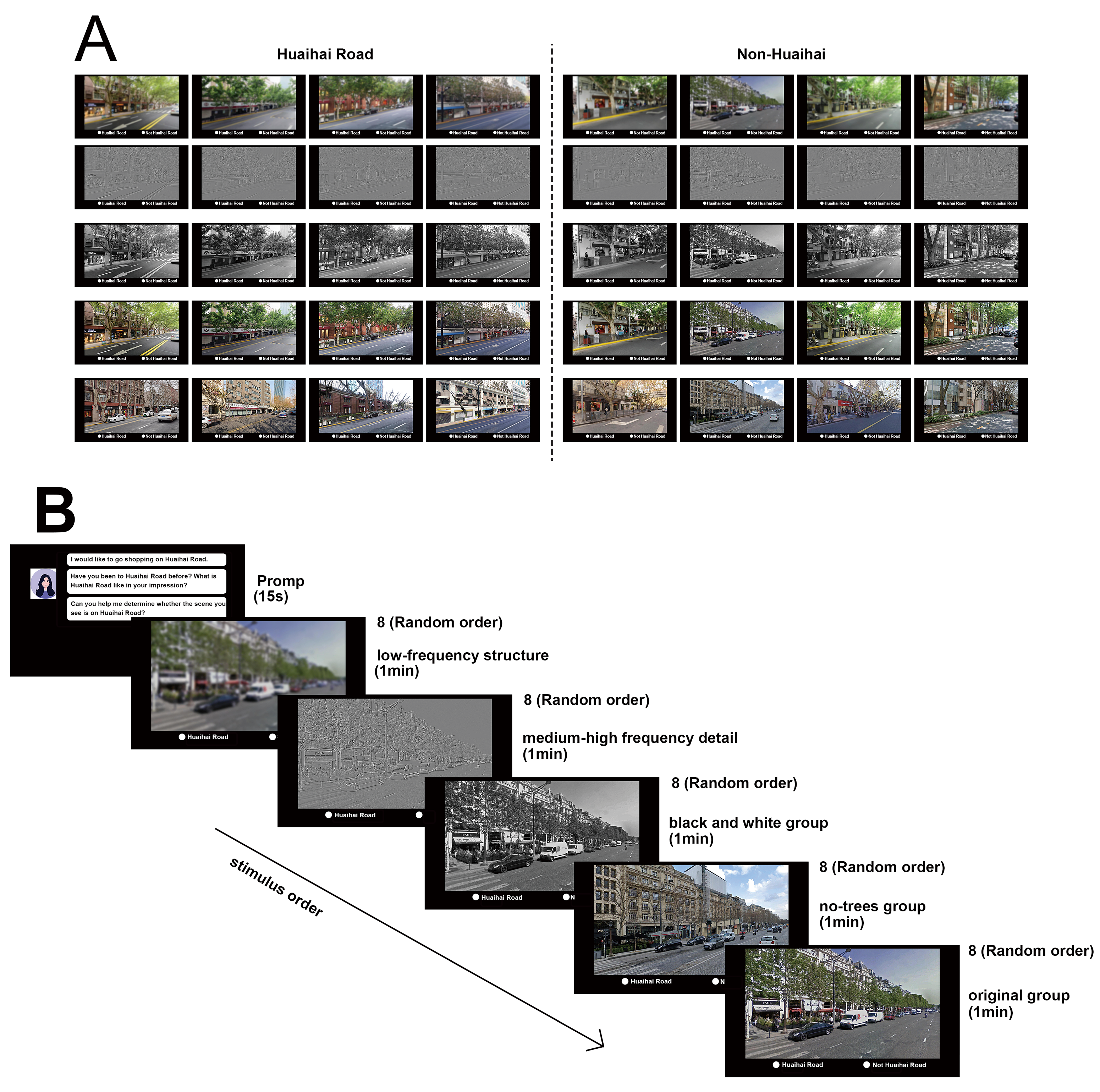

To control for the influence of different architectural styles, comparator streetscapes were selected based on morphological and contextual similarities. Through background analysis, four non-Huaihai Road environments were chosen: the Champs-Élysées in France, Omotesando in Japan, Shaanxi South Road, and Fuxing Middle Road in Shanghai. These streets are all representative of the classic French-style tree-lined commercial boulevards, where pedestrian activity serves as the primary driver of urban vitality. They share similar economic models, with retail landscapes dominated by cafés, high-end boutiques, and fashion-forward establishments. Architecturally, contemporary and stylish designs are prominent features. To ensure visual comparability, all selected streetscapes are two-way, four-lane thoroughfares. A total of eight street scenes were chosen—four from Huaihai Road and four from non-Huaihai Road environments. This selection aims to balance familiar and unfamiliar streetscapes and eliminate the influence of differing styles on recognition.

The visual stimuli were sourced from Baidu Street View and Google Street View to ensure consistency in perspective and content, with Shanghai streets from Baidu and French and Japanese streets from Google. All street view samples were captured from a pedestrian perspective, emphasizing the full view of the street façade with a consistent vanishing point, ensuring controlled variables like angle and visibility to minimize their impact on street recognition performance. All images were processed in PNG format to maintain image clarity and prevent the introduction of compression artifacts.

To investigate the role of spatial frequency and color in street recognition, the images were systematically manipulated into four distinct experimental conditions: original group (unmodified images served as the control condition, presenting the streets as they appeared in real life with all visual elements intact); low-frequency group (images were processed using a Gaussian filter (σ = 15) in Adobe Photoshop CC 2019, which effectively removed mid-to-high frequency details, such as signage, building textures, and ground patterns. This manipulation was intended to assess how global, low-frequency information affects recognition when fine details are absent); mid-to-high-frequency group (the opposite manipulation was applied by removing low-frequency information while enhancing the edges and finer details such as signage and architectural elements. This allowed the experiment to explore how detailed features contribute to recognition when broader structural information is minimized); black-and-white group (to isolate the effect of color, the images were converted to grayscale using Adobe Photoshop, leaving only luminance information to investigate the role of color in street recognition).

To examine the role of trees in street recognition, the same set of street scenes was obtained under two seasonal conditions. The original images were obtained in the summer months (July–October), when trees were in full foliage, representing the natural condition of the streetscape. The no-trees images were obtained in the winter months (January–March), when the same streets were presented without leaves on the trees, effectively removing the visual element of trees while preserving the structural and architectural characteristics of the streets. This manipulation was designed to evaluate whether the absence of trees influences recognition accuracy and viewing strategies, without altering other critical features of the streetscape. To minimize potential confounding variables, the images in both conditions were carefully matched in terms of lighting, perspective, and weather conditions.

Each image was calibrated for brightness and contrast using Photoshop’s automatic contrast and color leveling functions to ensure visual consistency across conditions. A histogram analysis was conducted on each image to confirm uniform brightness levels, ensuring that lighting differences would not confound the results.

The stimuli were presented on a DELL display screen with a resolution of 1600 × 1280 pixels (see

Figure 1). Participants’ eye movements were recorded using an SMI REDn desktop eye tracker (SensoMotoric Instruments GmbH, Teltow, Germany), with a sampling rate of 60 Hz and a spatial accuracy of approximately 0.25°. This device provided high precision in capturing the fine details of participants’ gaze behavior, such as fixation duration, blink frequency, and gaze paths.

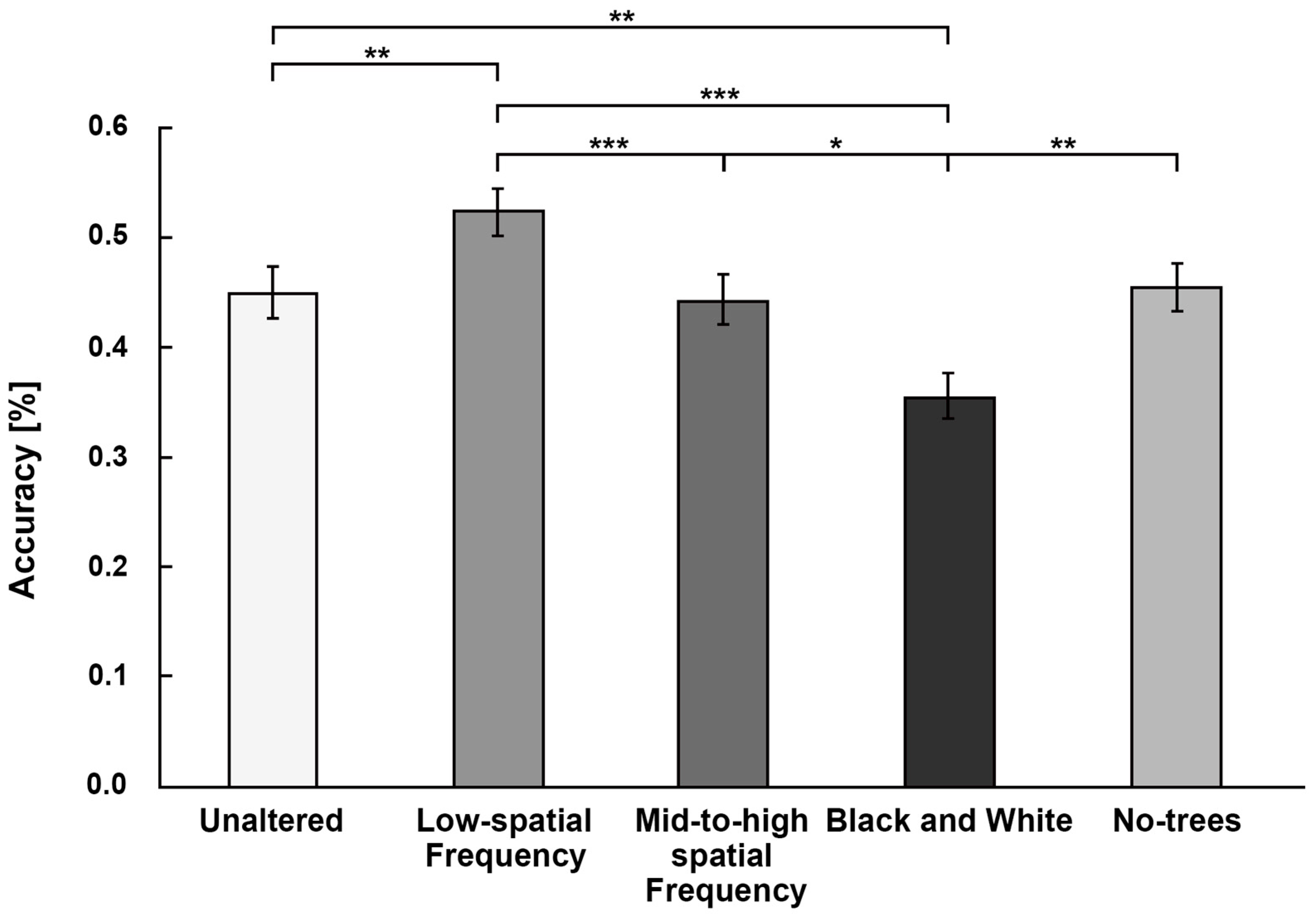

2.3. Procedure

The experiment was structured to systematically explore how low-level visual features influence street recognition, with a particular emphasis on Huaihai Road. Participants were seated in front of a DELL display screen (1600 × 1280 pixels, 120 Hz; Dell Inc., Round Rock, TX, USA), where they viewed the manipulated visual stimuli while their gaze behavior was recorded using the SMI-redN desktop eye tracker. Before the main experiment began, participants underwent a calibration procedure using a 9-point calibration grid to ensure precise recording of their eye movements. Calibration was repeated as necessary to achieve accuracy within 0.5 degrees of visual angle.

Participants were introduced to the study with a brief explanation of the task. They were instructed to determine whether the street shown in each image was Huaihai Road or another location. The experiment employed a 2 (Huaihai Road, other streets) × 5 (type of image) factorial design (see

Figure 2). Participants viewed images from two categories—Huaihai Road or non-Huaihai Road—under four different manipulation conditions: original images, low-frequency images, mid-to-high-frequency images, black-and-white images, and no-trees images.

To simulate a real-world recognition scenario, participants were instructed as follows: “Imagine you’re helping someone navigate Huaihai Road. I will show you images, and you need to determine whether the image is of Huaihai Road or another street.” No strict time limit was imposed for each image, but participants were encouraged to make their decisions within one minute per group of images to maintain attention and avoid fatigue. The viewing time for each image was self-paced, allowing the eye-tracking system to capture natural gaze behavior without the imposition of artificial time constraints.

The images were presented in a randomized sequence to prevent order effects from influencing the results. Participants viewed five groups of images (one group per manipulation condition) in randomized orders within each group, ensuring that learning effects were minimized.

During the experiment, the eye-tracking system recorded fixation points along with their corresponding timestamps, allowing the analysis of key metrics such as fixation duration, blink frequency, and gaze paths. These metrics were used to analyze how participants processed the manipulated images and whether the changes in spatial frequencies and color impacted their ability to recognize Huaihai Road. In addition to the eye-tracking data, participants were asked to provide an oral response for each image, indicating whether they believed it depicted Huaihai Road. Reaction times were also recorded, though these were not emphasized as a primary measure due to the self-paced nature of the task.

2.4. Analysis

The data analysis was conducted through a multi-step process to examine the influence of low-level visual features on street recognition. Both accuracy measures and eye-tracking metrics were utilized to provide a comprehensive understanding of how different image manipulations impacted recognition performance and visual behavior.

To analyze the impact of different visual conditions on participants’ street recognition performance, ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) was used to examine the effects of manipulated visual conditions (original, low-frequency, mid-to-high-frequency, black-and-white images, and no-trees images) on recognition accuracy. Recognition accuracy was defined as the percentage of correct identifications of the location depicted in each image across all participants.

To determine whether different visual conditions influenced recognition accuracy by affecting participants’ gaze behavior, several key eye-tracking metrics were analyzed: fixation duration (the length of time participants focused on specific areas), fixation count (the total number of fixations during image viewing), and blink frequency (as an indicator of cognitive load). ANOVA was conducted to analyze these metrics and identify significant differences in gaze behavior across the various image conditions. Post hoc comparisons were also performed to pinpoint specific differences between the image conditions.

Eye-tracking data were processed and visualized using specialized MATLAB codes (MATLAB R2023a), including EyeMMV [

39] and the Toolbox for Scanpath Modeling and Classification with Hidden Markov Models (SMAC with HMM) [

40,

41]. The EyeMMV software was used to generate heat maps, providing visual representations of the spatial distribution of participants’ gaze fixations across different image types. These heat maps provided a spatial distribution of where participants focused their attention. To analyze the temporal dynamics of eye movements, Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) were employed, offering insights into how gaze transitions occurred between various regions of interest (ROIs). This method enabled a detailed examination of the sequences of gaze shifts, helping to understand how participants navigated the visual information presented in each image. The heat maps generated by EyeMMV software provided visual representations of the distribution of fixations across images, while the HMM analysis modeled the gaze transitions between dynamically defined ROIs. The ROIs were not predefined but were generated based on actual fixation patterns observed during the experiment. This dynamic ROI generation enabled a more accurate reflection of participants’ natural gaze behavior. Together, these methods provided a detailed understanding of how visual information was processed and how different low-level visual features influenced street recognition.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Recognition Accuracy

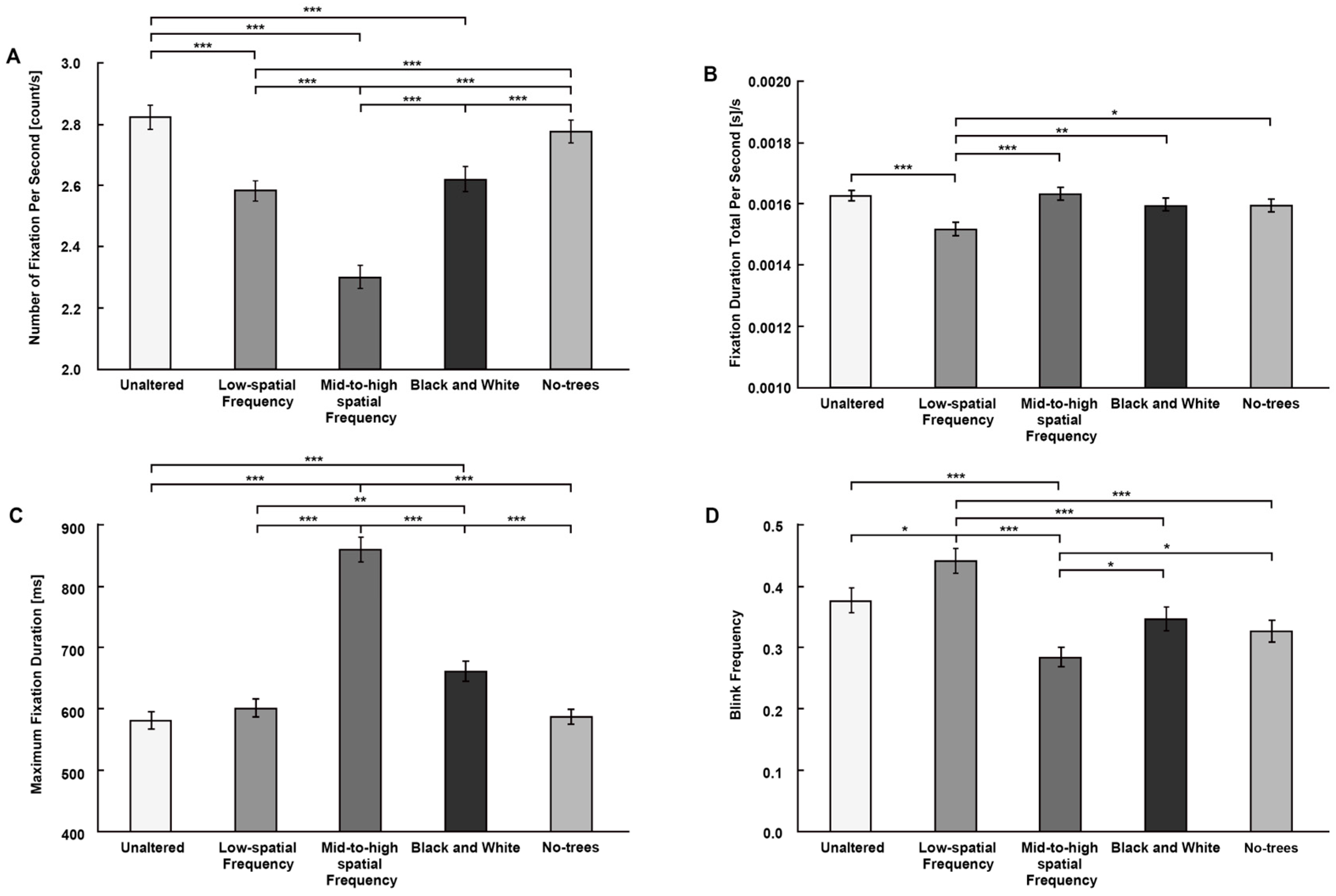

In this study, we examined how manipulating spatial frequencies, color and tree presence affected participants’ ability to correctly identify Huaihai Road. The results revealed significant differences in recognition accuracy across the five manipulated image conditions, offering valuable insights into the role of spatial frequencies and color in rapid street recognition tasks.

The ANOVA analysis results indicated a significant main effect of image manipulation on recognition accuracy (F(4, 220) = 8.416,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.133). As shown in

Figure 3, spatial frequency and color changes notably impacted participants’ ability to recognize Huaihai Road. Post hoc tests using the LSD correction further clarified the influence of individual visual features on recognition accuracy. Images with low spatial frequencies, which preserve coarse, global information about the street scene, significantly improved recognition accuracy compared to the original images (mean difference = −0.097, 95% CI [−0.163, −0.032];

p = 0.004). In contrast, images processed to contain only mid-to-high spatial frequencies (removing broad structural information while isolating fine details such as edges and textures) did not significantly affect recognition accuracy compared to the unaltered images (

p > 0.05). The removal of color from the images significantly reduced recognition accuracy (mean difference = 0.094, 95% CI [0.029, 0.160];

p = 0.005), reinforcing the importance of color in the rapid identification of streets. The presence or absence of trees did not produce a significant effect on recognition accuracy (

p > 0.05), suggesting that the trees did not obscure key visual information necessary for recognition.

Meanwhile, we also found that participants who were more familiar with Huaihai Road demonstrated higher recognition accuracy. To examine whether familiarity influenced participants’ ability to recognize the street based on its visual features, we conducted a one-way ANOVA with recognition accuracy as the dependent variable and participant group (Shanghai residents vs. non-residents) as the independent factor. The results showed a significant effect of group on recognition performance, indicating that Shanghai residents achieved higher accuracy than non-residents (F(1, 223) = 5.24, p = 0.023, η2 = 0.023).

Overall,

Figure 3 shows that low-spatial-frequency images enhanced recognition accuracy, whereas black-and-white images reduced it, and tree removal had little effect. Furthermore, participants familiar with Huaihai Road generally performed better. These findings set the stage for examining how such image manipulations affected participants’ viewing strategies in the next section.

3.2. Effects on Viewing Strategy

3.2.1. Number of Fixations

Fixation is defined as the act of pausing the gaze on a specific area of the visual field to process information, and the number of fixations serves as a measure of visual search complexity [

46]. A higher number of fixations typically indicates greater cognitive effort in comprehending visual stimuli. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant impact of image manipulations on the number of fixations (F(4, 1795) = 37.395,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.043). All image types, except the no-trees condition, led to a significant reduction in the number of fixations compared to the original images (

Figure 4A). Specifically, low-spatial frequency images resulted in a 0.190 reduction in fixation count per second (95% CI [0.091, 0.288];

p < 0.001); mid-to-high spatial frequency images showed a more pronounced reduction, with a 0.541 decrease (95% CI [0.442, 0.640];

p < 0.001); black-and-white images elicited a 0.198 reduction in fixation count (95% CI [0.099, 0.297];

p < 0.001). In contrast, the presence or absence of trees did not significantly influence fixation counts (

p > 0.05).

3.2.2. Fixation Duration

Fixation duration refers to the length of time the gaze remains stationary on an area of interest, providing insights into the cognitive processing required [

47]. Longer fixation durations indicate that more cognitive effort is needed to process the visual stimuli at that point.

ANOVA results indicated a significant effect of image manipulation on total fixation duration per second (F(4, 1795) = 4.628,

p = 0.001, η

2 = 0.010). Fixation duration for low-spatial-frequency images was significantly lower than for the original images (mean difference = 0.00008, 95% CI [0.0004, 0.0001];

p < 0.001), suggesting that the absence of mid-to-high spatial frequency details allowed participants to process the remaining visual information more quickly (

Figure 4B). No other conditions showed significant differences (

p > 0.05).

ANOVA results indicated a significant effect of image manipulation on maximum fixation duration (F(4, 1795) = 52.209, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.106). mid-to-high spatial frequency images and black-and-white images significantly increased maximum fixation duration compared to the original images (mid-to-high spatial frequency: mean difference = −279.627, 95% CI [−324.608, −234.646]; p < 0.001; black-and-white: mean difference = −80.908, 95% CI [−125.890, −35.927]; p < 0.001). In contrast, low-spatial-frequency images and the no-trees condition did not significantly affect maximum fixation duration (p > 0.05).

3.2.3. Blink Frequency

Blink frequency, which refers to the number of times participants blink per minute, is often used as an indirect measure of cognitive load; higher blink rates are associated with increased mental effort [

48]. In this study (

Figure 4D), ANOVA revealed a significant effect of image manipulations on blink frequency (F(4, 1759) = 9.854,

p < 0.001, η

2 = 0.021).

Low-frequency images led to a significant increase in blink frequency compared to the original images (mean difference = −0.069, 95% CI [−0.118, −0.020]; p = 0.006), indicating reduced cognitive load. The removal of mid-to-high-frequency information appeared to ease information processing, as participants relied more on global scene structure. Conversely, mid-to-high spatial frequency images resulted in a notable decrease in blink frequency (mean difference = 0.084, 95% CI [0.035, 0.133]; p < 0.001), suggesting that participants faced a higher cognitive load when forced to rely on detailed, mid-to-high-frequency information.

3.3. Contributing Factors on Fixation Patterns

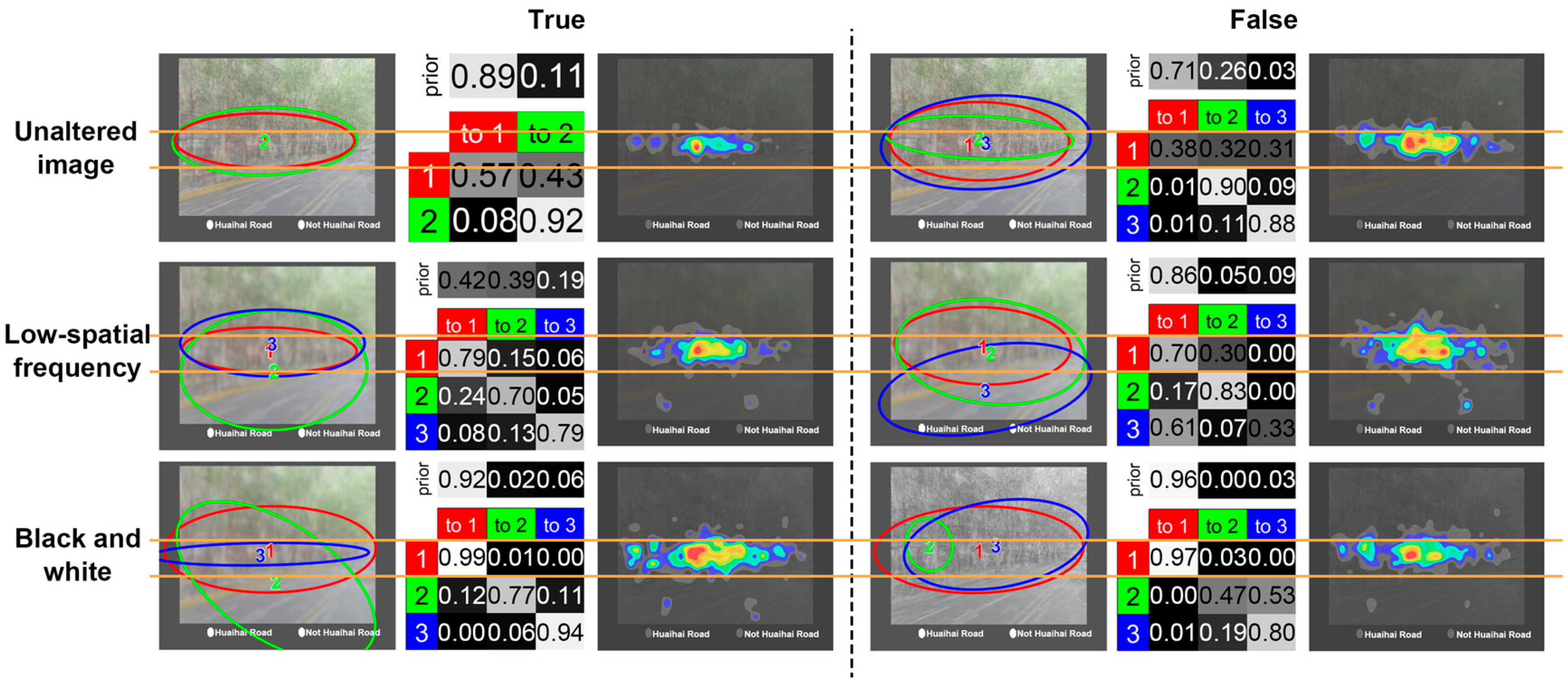

The analysis of fixation behavior provides insight into how low-level visual features—specifically spatial frequency and color—affect attention allocation during street recognition [

49]. Considering the results of the accuracy analysis, we focused on two manipulated conditions—low-frequency and black-and-white images—and compared them to the original images to assess how these features influence fixation patterns.

To analyze gaze transitions across key spatial elements (e.g., storefronts, facades, signage), we applied Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM) [

50], which allowed us to model dynamic eye movement sequences and identify how visual input guided attention across predefined regions of interest (ROIs). The results revealed distinct attentional patterns across image types, particularly in the location of initial fixations and the progression of gaze through the scene. These are illustrated in

Figure 5, which presents heat maps and transition probabilities among the red, green, and blue ROIs. The accompanying table reports the prior probabilities for each ROI (i.e., the likelihood that the first fixation falls within each region) and the transition probabilities between them.

This study adopted a validated, data-driven approach to defining regions of interest (ROIs) in the scan path analysis, using the open-source SMAC with HMM toolbox [

50,

51]. In this framework, ROIs are represented as hidden states in a hidden Markov model (HMM), each modeled by a two-dimensional Gaussian distribution defined by its centroid and spatial spread. The optimal number of states is determined automatically via variational Bayesian inference [

52], and all model parameters (including state transitions, emissions, and priors) are learned directly from raw gaze data through maximum likelihood estimation. This unsupervised procedure ensures that ROI extraction is independent of subsequent classification. The original method was validated across two independent datasets with static images and dynamic videos, with robust cross-dataset generalization confirmed via leave-one-out testing, establishing the reliability of this modeling approach.

For the original, unmodified images, participants’ fixations were primarily concentrated in the first-floor storefront area, especially among those who correctly recognized the scene. The ROI marked in red, representing the most likely initial fixation region, captured 89% of first fixations in correct identifications. In contrast, incorrect recognitions were associated with more dispersed patterns; the probability of first fixations landing in the red ROI dropped to 71%, and gaze was more likely to shift toward second-floor facades and signage.

Fixations in the low-frequency condition also clustered within the first-floor area, showing a distribution similar to that of the original images. To quantify this, we calculated the proportion of fixations within the first-floor region relative to total fixations for each image. A one-way ANOVA revealed a significant group effect, F(2, 21) = 3.490, p = 0.049, η2 = 0.250. However, post hoc analysis (LSD) showed no significant difference between the low-frequency and original conditions (p = 0.064), suggesting that low-frequency information did not substantially disrupt attention to diagnostic spatial regions.

ROI analysis and heat maps further confirmed this result. Both correct and incorrect identifications in the low-frequency condition showed sustained fixations within the red ROI, with 79% and 70% of fixations, respectively, remaining in this area. This indicates that low-frequency visual input effectively guided and maintained attention on the first-floor storefronts, a region critical for street recognition.

In contrast, black-and-white images produced notably more dispersed fixation patterns. Compared to the original condition, fixation concentration within the first-floor area significantly declined (mean difference = 12.383, 95% CI [2.051, 22.550]; p = 0.020), indicating that the absence of color altered the spatial distribution of attention. ROI and heat map analyses showed that gaze shifted toward higher facades, signage, and peripheral elements. For incorrect identifications, only 60% of fixations remained in the red ROI. These patterns suggest that removing color and mid-to-high-frequency details impaired holistic scene processing and reduced attention to key spatial cues.

4. Discussion

This study explored the impact of low-level visual features, particularly spatial frequencies, color and tree presence, on rapid recognition of urban streets, using Huaihai Road as a case study. The findings provide valuable insights into the cognitive processes underlying scene recognition, with significant implications for fostering place identity and promoting the socio-environmental sustainability of urban design.

4.1. Role of Low-Level Visual Features in Street Recognition

The findings demonstrate that low-level visual features play a critical role in street recognition, influencing both recognition accuracy and visual search strategies. Specifically, the removal of mid-to-high spatial frequencies enhanced recognition accuracy, whereas the removal of color information significantly impaired performance. These results suggest that coarse, low-frequency visual cues are essential for rapidly identifying streets, and color provides critical information for differentiating complex street scenes. These patterns, however, should be interpreted with caution. The observed improvement in recognition associated with the removal of mid- to high-frequency information was modest in magnitude and thus represents preliminary evidence rather than a definitive effect. It is possible that reducing fine-grained detail simply lessened visual competition in our specific stimulus set, and broader image samples will be necessary to confirm the generality of this tendency.

The improvement in recognition accuracy associated with low-frequency information may be attributed to the brain’s reliance on global structural cues during rapid scene categorization. The removal of mid-to-high spatial frequencies appears to reduce visual distractors, allowing participants to focus on essential elements such as building facades and storefronts. This interpretation aligns with previous studies indicating that low spatial frequency information supports global scene layout perception and facilitates rapid perceptual grouping [

53,

54,

55].

In contrast, color provides critical visual cues for distinguishing specific urban elements. The significant decrease in accuracy when color was removed supports its integral role in scene classification and object recognition, as demonstrated in previous studies [

34,

38]. Color appears to enhance scene recognition and memory, particularly by accentuating functionally important or semantically meaningful regions.

Eye-tracking data further illuminate these perceptual mechanisms. The removal of mid-to-high spatial frequencies reduced both the number of fixations and fixation duration, suggesting increased efficiency in visual information processing. This finding supports previous research indicating that global, low-frequency information simplifies visual search and directs attention toward informative spatial areas [

55]. In contrast, removing color increased fixation durations, indicating greater cognitive effort required in processing visual information without chromatic cues [

48].

Further fixation pattern analyses provided insights into attentional allocation. Under low-frequency conditions, participants consistently directed their gaze toward diagnostic regions, notably first-floor storefront areas. Both ROI analysis and heatmap visualizations confirmed that, even without fine-grained details, participants effectively identified and maintained attention on structurally informative areas critical for recognition. In contrast, black-and-white images produced dispersed gaze distributions, with fewer fixations concentrated in storefront regions. The absence of color diminished participants’ ability to prioritize meaningful spatial regions, likely contributing to reduced recognition accuracy.

Our findings also provide a clearer perspective on how low-level visual information contributes to the rapid recognition of urban streets. The improved recognition performance after removing mid-to-high spatial frequencies suggests that some commercial streets may contain excessive fine-grained details—such as dense signage, textures, and decorative elements—that interfere with the extraction of global visual structure. In this context, our results indicate that clear overall forms and coherent color patterns help observers grasp the essential structure of a street within a very short time window, whereas overly intricate surface details may offer limited contribution to rapid identification. These insights highlight how the arrangement of broad visual components can shape the perceptual distinctiveness of streets in early visual processing.

4.2. Presence of Trees Affects Street Recognition

This study also investigated whether the presence of trees, a recurring natural element in urban streetscapes, affects street recognition. The removal of trees led to no significant effect on recognition accuracy or overall gaze metrics. This finding suggests that although trees are visually prominent, they may not serve as critical cues for identifying familiar streets when key features such as storefronts and signage remain visible. More broadly, when considered alongside the findings on low-level visual features, the results indicate that the distinct recognition of a street is not driven by isolated urban elements but rather by complex and holistic visual information. Thus, further decision makers should be cautious when planning the urban landscape: trees and other elements alone are not ‘short cuts’ to replicate a certain streetscape. Nevertheless, we note that our dataset did not reveal a positive contribution of trees to rapid street identification. This null effect may relate to participants’ tendency to allocate attention primarily to ground-floor features—such as storefronts and building edges—during brief recognition, thereby reducing the perceptual weight of vegetation in this task. As this interpretation is constrained by our sample characteristics, future research with more varied streetscapes and seasonal conditions is needed to determine the robustness of this pattern.

These findings partially contrast with prior studies suggesting that greenery enhances the legibility and appeal of urban environments [

56]. In our study, trees may have had limited diagnostic value and did not obscure essential visual information, which may explain the minimal behavioral impact observed. Overall, the results highlight the central role of diagnostic visual features—particularly spatial frequency content and color—in guiding attention and supporting rapid street recognition. These insights have practical implications for both urban design and the development of visual recognition systems.

Regarding the non-significant effect of trees, our interpretation is more cautious. Although trees did not improve rapid street recognition in our task, this does not mean that natural elements are unimportant in urban environments. It is possible that trees influence how people experience and remember a street over longer periods rather than how quickly they identify it in a brief visual exposure. This perspective emphasizes the need to consider different temporal and cognitive processes when evaluating urban elements and to distinguish between features that support instant perceptual identification and those that shape broader experiential qualities.

4.3. Implications for Future Urban Planning

The current study extends prior work on visual scene recognition by empirically examining the diagnostic value of spatial frequency and color in realistic urban environments. While previous studies have identified low-frequency information and color as important cues [

34,

54], our use of image manipulation combined with eye-tracking provided a more precise view of how these features influence both attention allocation and recognition performance. These designs, in general, would further validate the importance of incorporating the eye-tracking data to further understand the visual perception in realistic problems.

These findings offer practical guidance for urban designers. Emphasizing global structural cues such as building layouts, facades, and storefronts may enhance street recognizability and help sustain local identity in increasingly homogeneous urban environments [

57]. Moreover, the deliberate use of color in architecture, signage, and street furniture can strengthen the visual identity of streets and reinforce residents’ sense of place. Although natural elements such as trees contribute esthetic and ecological value, our results suggest that they complement rather than compete with key spatial cues when integrated thoughtfully into design. By applying these insights, urban planners can create streetscapes that are not only visually distinctive and legible but also socially cohesive and environmentally sustainable, thereby reinforcing the perceptual and cultural foundations of place identity.

In addition to the above points, our findings on the diagnostic roles of spatial frequency and color also provide more concrete design directions for practitioners. First, emphasizing clear street silhouettes and coherent building forms can improve global recognizability, especially when supported by deliberate color application. Prior studies show that color not only shapes the emotional perception of urban spaces but also enhances the distinctiveness of local architectural character [

58]. Cities such as Brașov demonstrate how carefully coordinated building colors can strengthen visual harmony and reinforce place identity within historic contexts [

59], while color systems developed for Tibetan-inhabited areas show how culturally rooted palettes can preserve local distinctiveness in contemporary planning [

60].

Second, design attention at the ground-floor level is particularly crucial for street identity. Transparent façades, active frontages, and pedestrian-oriented layouts have been shown to enhance street vitality and improve the legibility of the urban environment [

61,

62]. These strategies create visually engaging edges that complement the global structural cues highlighted in our findings.

Finally, from a policy perspective, balancing detail and simplicity may be achieved through clear yet flexible design codes. Frameworks similar to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in the UK illustrate how overarching design principles can guide color, form, and ground-floor standards while still allowing local authorities to adapt guidelines to cultural and contextual needs [

63]. Such an approach can help translate perceptual insights into actionable urban design practices.

4.4. Limitations of the Current Study

Several limitations should be noted. Firstly, the study focused primarily on Huaihai Road and a limited set of comparator streets, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. However, the selection of these streets, which share similar historical backgrounds and abundant image resources, allowed robust experimental design. Secondly, static photographs do not fully capture dynamic aspects of real-world street perception, although they facilitate controlled manipulations of visual features. Future studies could incorporate dynamic stimuli or virtual reality environments to simulate natural viewing conditions more accurately. Lastly, although our 1:1 recruitment of Shanghai residents and non-residents helps reduce familiarity-related bias, recognition performance may still reflect prior experience in addition to low-level visual cues.