Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Supply–Demand Matching of Rural Social Values: A Case Study of Yangzhong City, Jiangsu Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

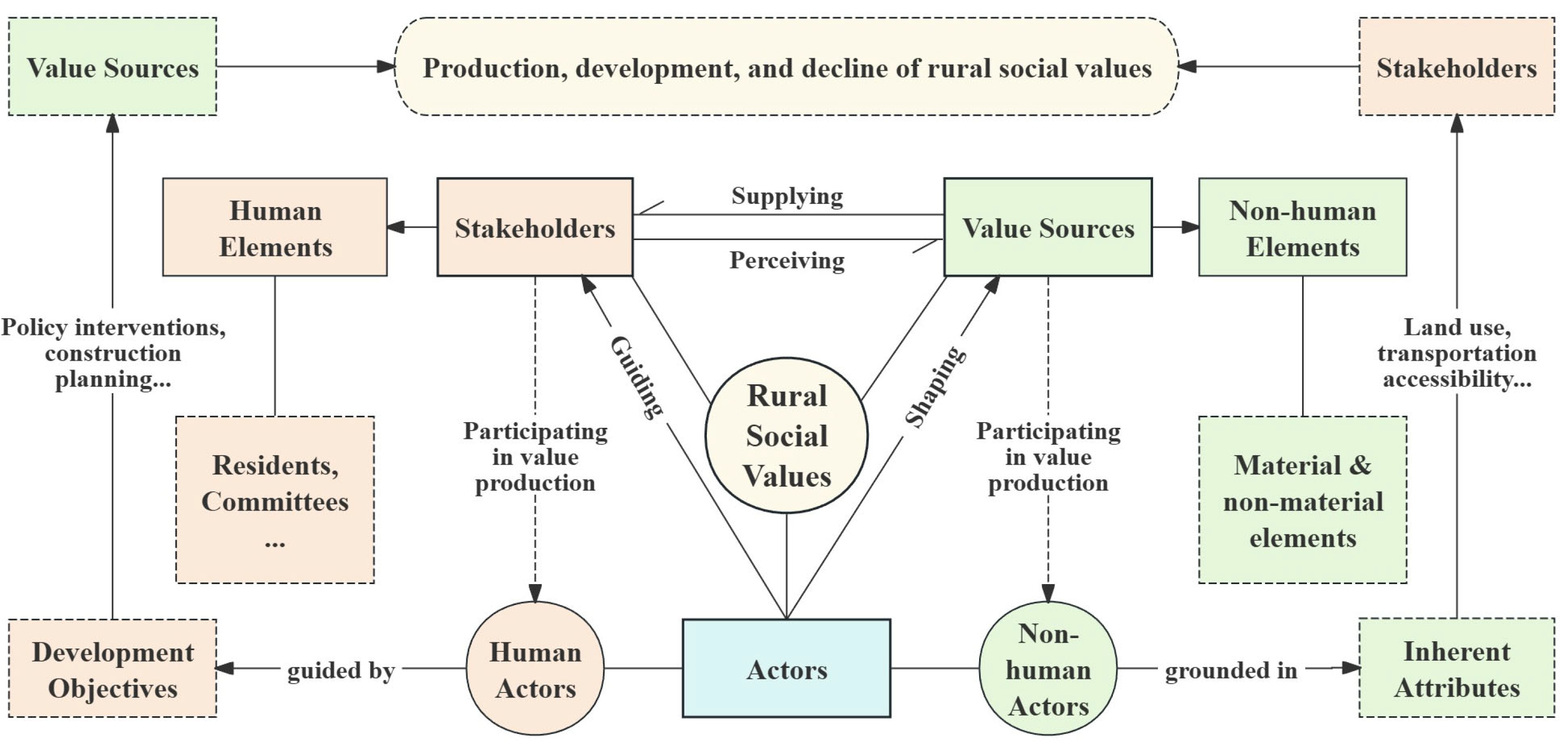

2.1. Theoretical Framework Construction

2.1.1. The Connotation and Formation Logic of RSV

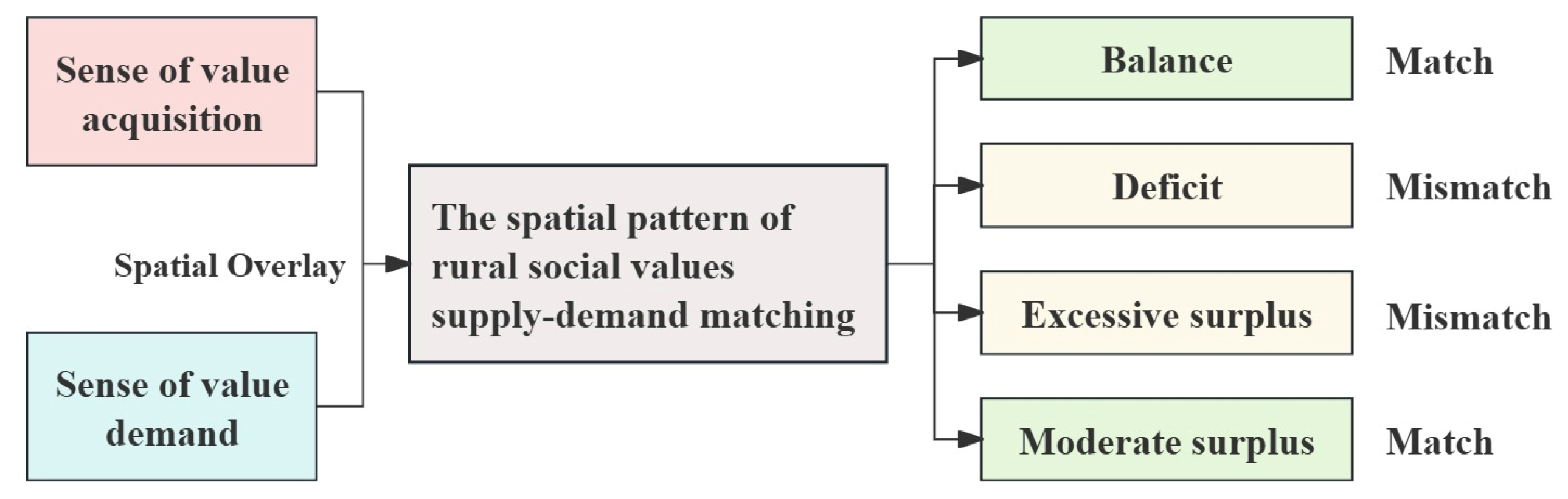

2.1.2. The Spatial Pattern of RSV Supply–Demand Matching

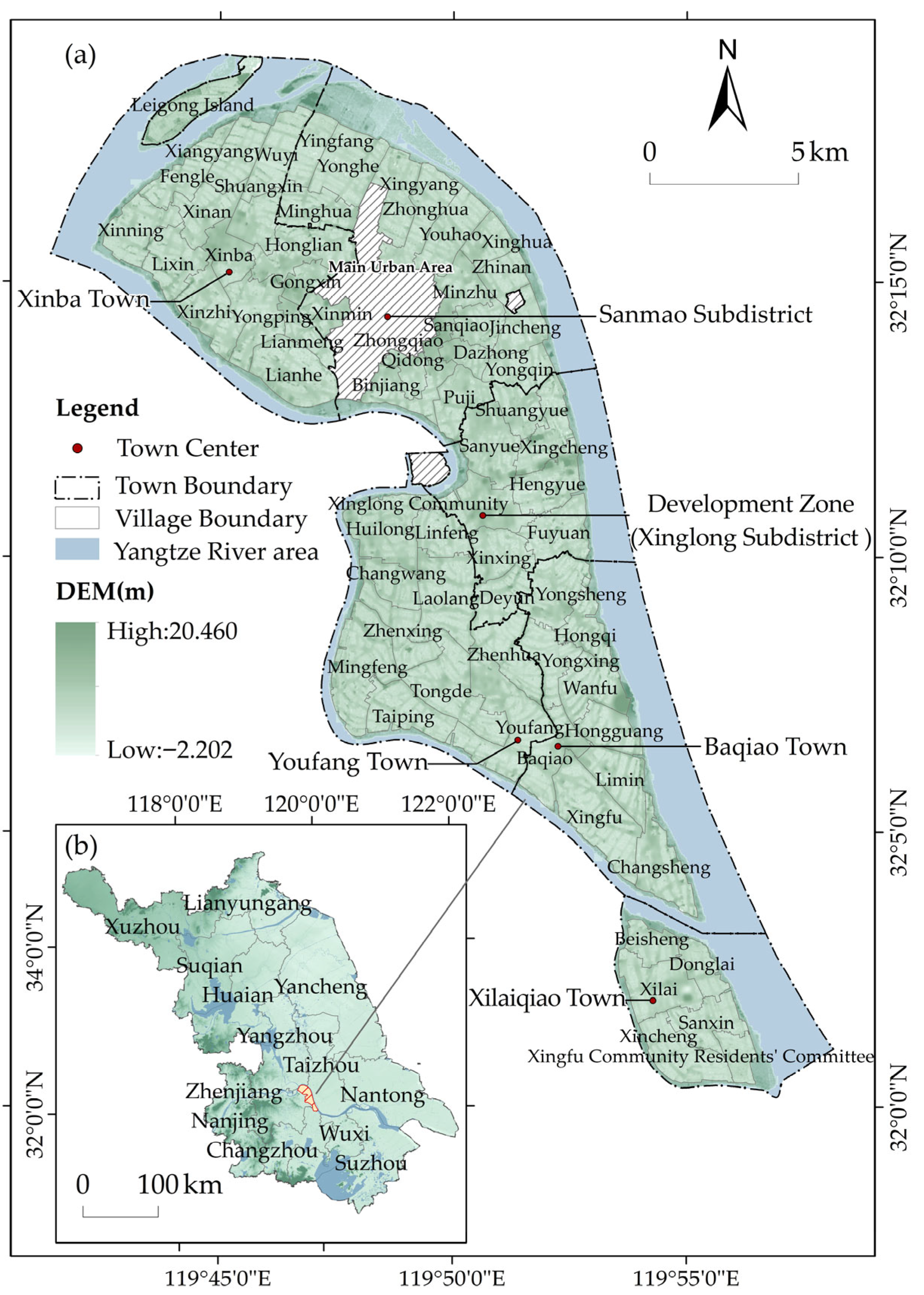

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Classification and Assessment System of RSV

2.3.2. Assessment Methods for RSV Supply and Demand

2.3.3. Analytical Methods for Spatial Characteristics of Supply–Demand Matching

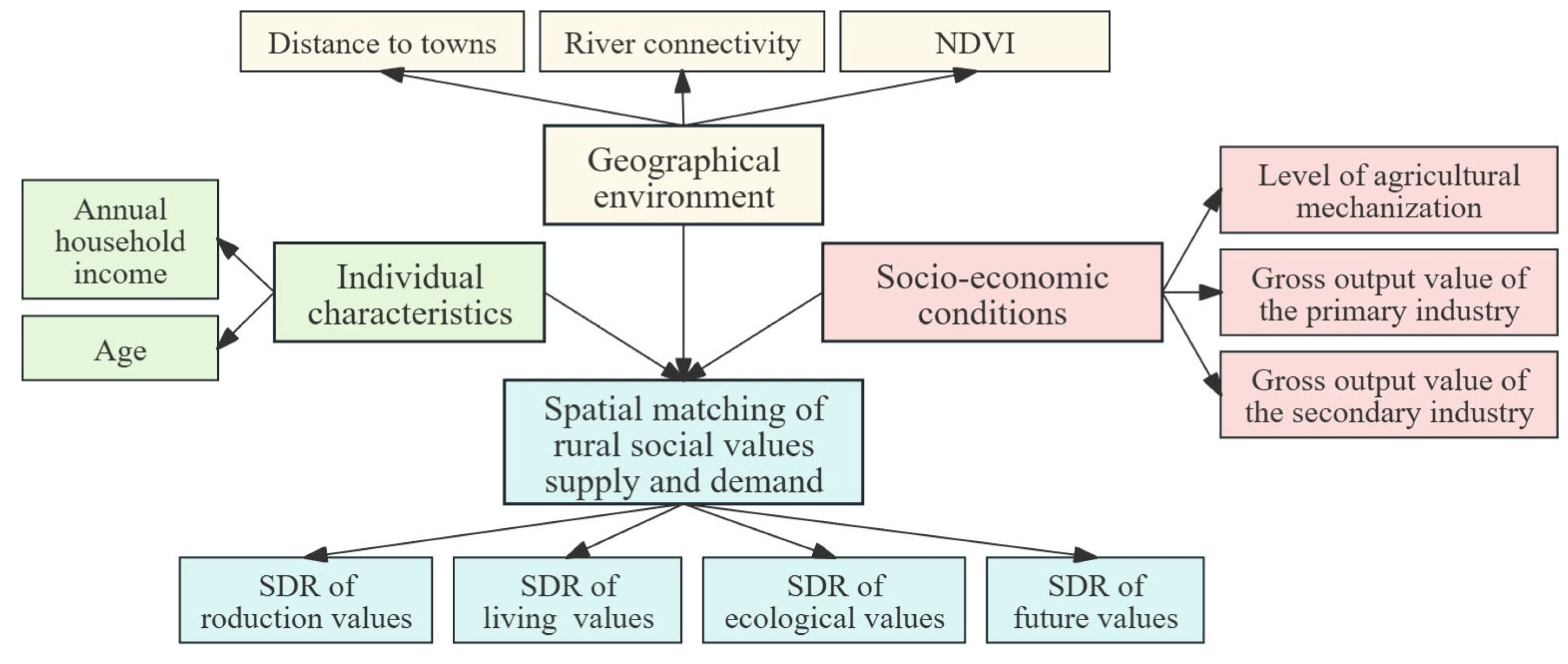

2.3.4. Analytical Methods for Influencing Factors of Spatial Supply–Demand Matching

2.4. Data Sources and Processing

2.4.1. Survey Data

2.4.2. Geographical Environment Data

2.4.3. Socio-Economic Data

2.5. Analytical Workflow

- (1)

- Analysis of RSV Supply and Demand Spatial Characteristics: Using the SolVES model, the SI and DI of each perceptual indicator were quantified at the raster scale (10 m × 10 m). These values were then aggregated stepwise using the equal-weight averaging method to derive the raster-scale SI and DI for both Level-2 and Level-1 values. Subsequently, the Zonal Statistics tool in ArcGIS was employed to calculate the supply and demand levels for both Level-2 and Level-1 values within each administrative village, thereby revealing their spatial differentiation characteristics.

- (2)

- Analysis of the Spatial Characteristics of RSV Supply–Demand Matching: Based on the village-scale supply and demand assessment results, the SDR was calculated to classify the matching type for each value category in every village. This process helped elucidate the overall spatial pattern and differentiation rules of RSV supply–demand matching.

- (3)

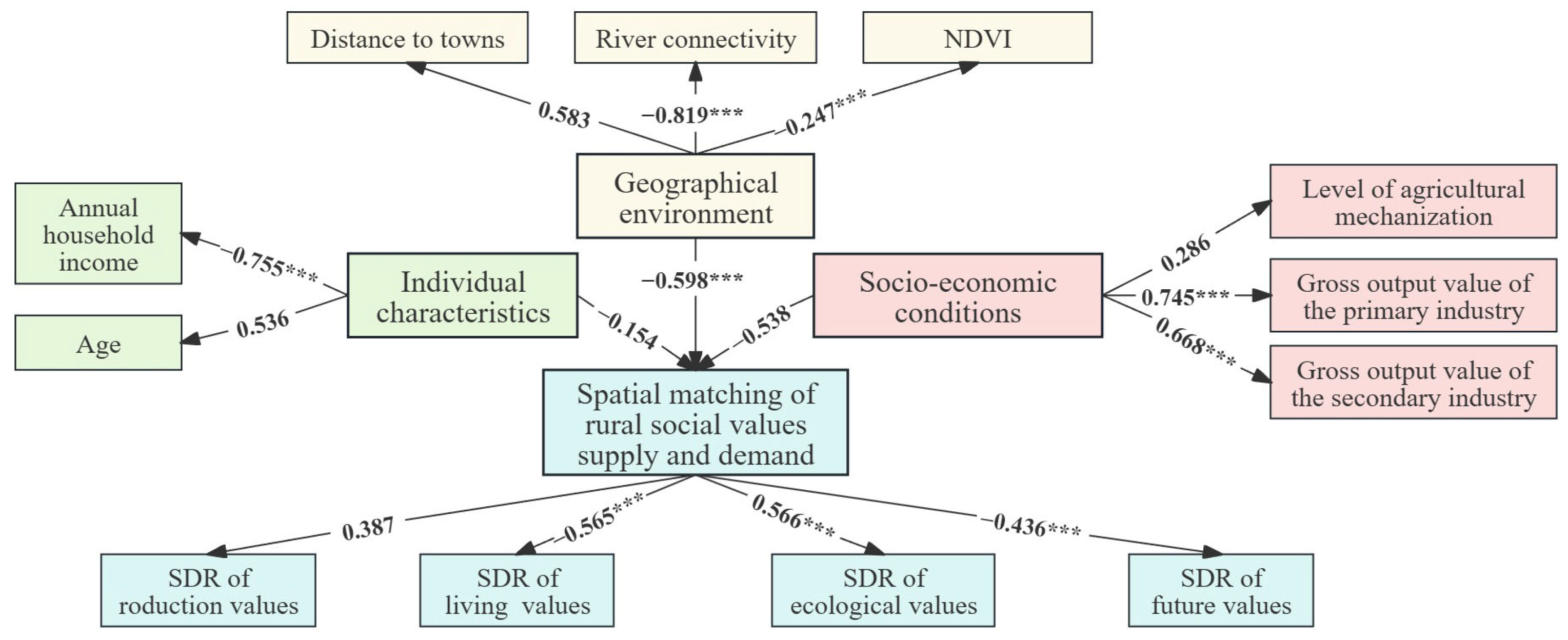

- Identifying the Influencing Mechanism of RSV Supply–Demand Matching: Using the SDR of the four Level-1 values as the dependent variable and individual characteristics, socio-economic conditions, and geographical environment as independent variables, a structural equation model (SEM) was constructed. Through model fitting and hypothesis testing, the key factors influencing the spatial matching of RSV supply and demand, along with their action paths and effect strengths, were identified (Figure 5).

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Characteristics of RSV Supply and Demand

3.1.1. Spatial Characteristics of RSV Supply

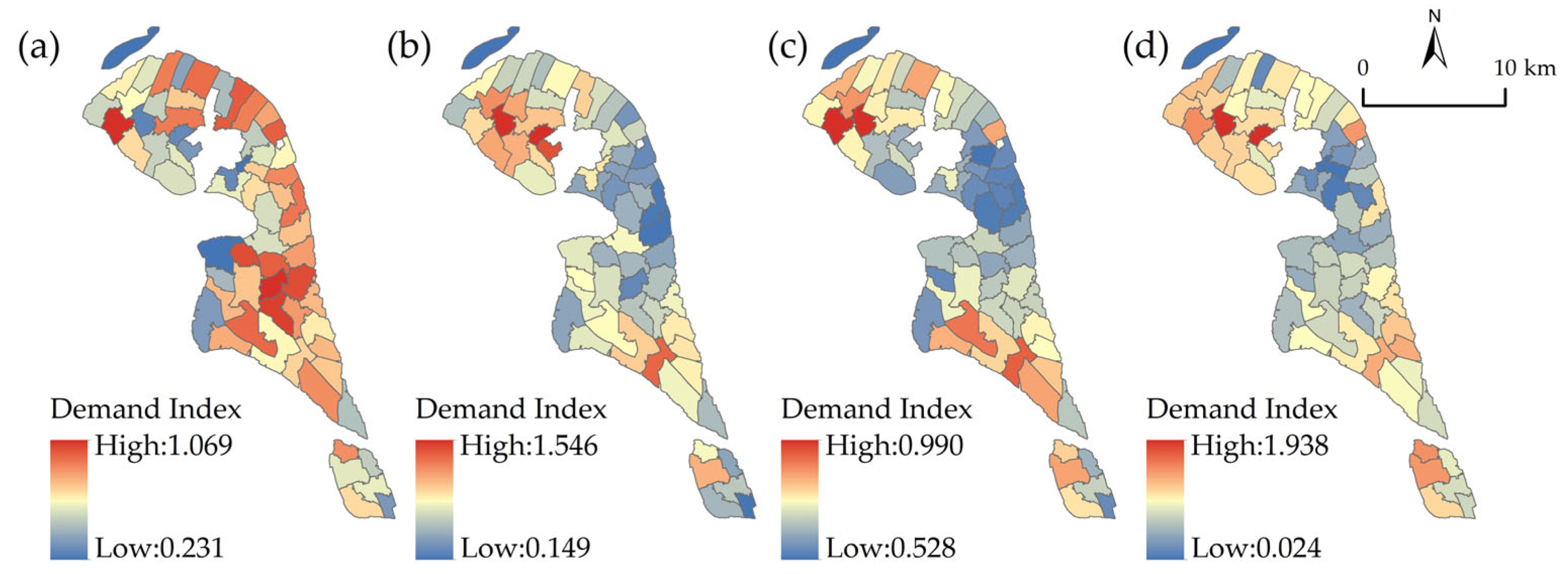

3.1.2. Spatial Characteristics of RSV Demand

3.2. Spatial Characteristics of RSV Supply–Demand Matching

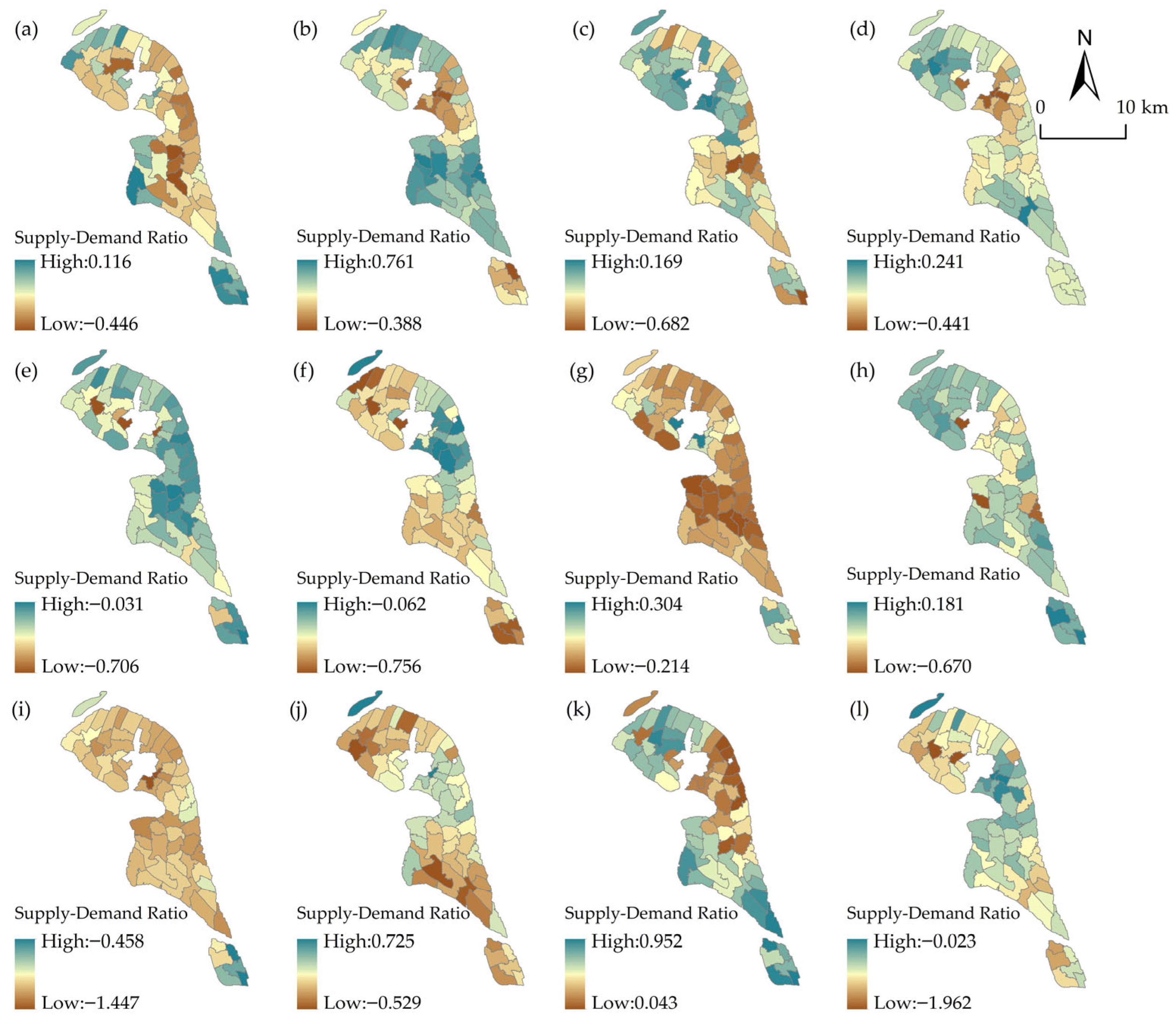

3.2.1. Spatial Characteristics of Supply–Demand Matching for Level-2 Values

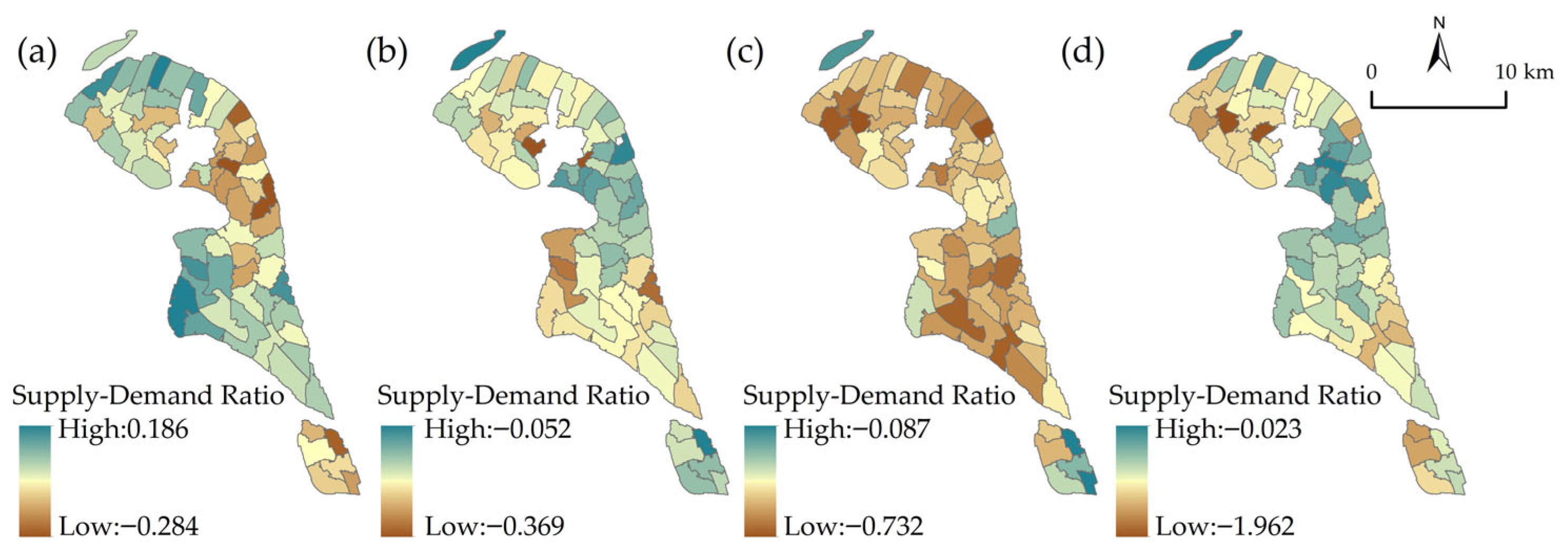

3.2.2. Spatial Characteristics of Supply–Demand Matching for Level-1 Values

3.3. Influencing Factors of RSV Supply–Demand Matching

4. Discussion

4.1. Causes of the Spatial Characteristics of RSV Supply, Demand, and Supply–Demand Matching

4.2. Mechanisms of RSV Spatial Supply–Demand Matching and Alleviation of the Identity Crisis

5. Conclusions

- RSV supply exhibits a composite spatial pattern characterized by “ecological baseline constraints” and “urban–rural boundary differentiation”. The supply of Ecological Value is primarily determined by natural conditions, while the supply of Production and Living Values forms a complementary distribution along the urban–rural boundary, reflecting the reality of functional competition for land. The supply of Future Value remains generally weak throughout the study area.

- The RSV demand pattern is shaped by both collective functional expectations and the actual level of supply. Public expectations for maintaining production functions in traditional agricultural zones, willingness to protect ecological functions along the Yangtze River, and recognition of the leading role of towns constitute the foundation of the RSV demand spatial pattern. Moreover, when both the quantity and quality of RSV supply in a specific location reach a certain threshold, that area can transform into a stable demand hotspot.

- RSV supply–demand matching displays a complex situation characterized by the coexistence of universal deficits, structural surpluses, and regional misalignments. Ecological Value faces a universal supply shortage, Agricultural Experience Value exhibits localized supply surplus in peri-urban areas, and the spatial misalignment between Production and Living Values reveals the trade-offs in decision-making during rural functional transitions.

- Geographical environment and socio-economic conditions are key factors influencing village-level RSV supply–demand matching. The geographical environment demonstrates a significant negative effect. Socio-economic conditions show no significant net effect due to their dual role in enhancing supply while simultaneously stimulating demand. The influence of micro-level individual characteristics is overshadowed by the overall village environment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Li, N. Analysis on the coupling development path of economy and ecological environment under the rural revitalization strategy. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2020, 29, 11702–11709. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.L.; Wang, W.L.; Fahad, S. Spatial and temporal characteristics of rural livability and its influencing factors: Implications for the development of rural revitalization strategy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 49162–49179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Cao, X.Z. Village Evaluation and Classification Guidance of a County in Southeast Gansu Based on the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Land 2022, 11, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.L.; Dou, H.J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C. Classification and path of rural revitalization from the perspective of rural multi-value: A case study of Chongqing municipality. Resour. Sci. 2023, 45, 450–463. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.P.; Wu, W.J.; Zhang, C.Q.; Xie, Y.B.; Lv, J.E.; Ahmad, S.; Cui, Z.R. The impact of social exclusion and identity on migrant workers’ willingness to return to their hometown: Micro-empirical evidence from rural China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Zhou, Y.K. Transfer of urban benefit: A theoretical proposition of rural revitalization. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.C.; Yang, Q.Y.; Yan, Y.; Yang, R.H.; Wang, D.; Zhou, L.L.; Zhang, B.L. Type characteristics, evolutionary stage and impact effects of rural spatial commodification. Econ. Geogr. 2024, 44, 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G.H.; Yang, Q.Y. The spatial production of rural settlements as rural homestays in the context of rural revitalization: Evidence from a rural tourism experiment in a Chinese village. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Ma, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Johnson, L. The lost countryside: Spatial production of rural culture in Tangwan village in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.F.; Yang, C.X.; Liu, Y.; Xin, G.X.; Chen, R.R. Evaluating the effect of comprehensive land consolidation on spatial reconstruction of rural production, living, and ecological spaces. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 168, 112785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.B. Spatial evolution and spatial production of traditional villages from “backward poverty villages” to “ecologically well-off villages”: Experiences from the hinterland of national nature reserves in China. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 1100–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, J.M.; Wang, J. Evolutionary process and mechanism of population hollowing out in rural villages in the farming-pastoral ecotone of Northern China: A case study of Yanchi county, Ningxia. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.K.; Xie, B.M.; Zhang, Z.F.; Guo, H. Rural multifunction in Shanghai suburbs: Evaluation and spatial characteristics based on villages. Habitat Int. 2019, 92, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.R.; Wang, Q.Y.; Cheong, K.C. Urban-Rural Construction Land Replacement for More Sustainable Land Use and Regional Development in China: Policies and Practices. Land 2019, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisaputri, G.; Khan, A.; Cameranesi, M.; Ungar, M. Rural Resilience and Mobility: A Scoping Review. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2023, 18, 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, A.S.; Nilsson, B. “For the good of the village”: Volunteer initiatives and rural resilience. J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 102, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, C.L.; Findlay, C. A review of rural transformation studies: Definition, measurement, and indicators. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 3568–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Demographic shifts and agricultural production efficiency in the context of urban-rural transformation: Complex networks and geographic differences. Glob. Food Secur.-Agric. Policy Econ. Environ. 2025, 45, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J. Rural sustainable development paths in the view of ecological civilization. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 46, 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, Z.C.; Dong, G.P.; Yu, Z.L.; Liu, K. Identifying the supply-demand mismatches of ecorecreation services to optimize sustainable land use management: A case study in the Fenghe River watershed, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Fang, B.; Zhang, H.J.; Wang, Y.R.; Wang, C.J.; Wei, S.Y. The formation mechanism for the provision pattern of rural social value based on the actor-network theory. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 2477–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.L.; Tu, S.S.; Ge, D.Z.; Li, T.T.; Liu, Y.S. The allocation and management of critical resources in rural China under restructuring: Problems and prospects. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioana-Toroimac, G.; Stoica, C.; Moroșanu, G.A.; Sandor, I.A.; Constantin, D.M. Assessing the role of actors in river restoration: A network perspective. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, D.Z.; Lu, Y.Q. A strategy of the rural governance for territorial spatial planning in China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1349–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Z.C.; Liu, K.; Gao, X.; Wang, Z.D. Regional spatial management based on supply-demand risk of ecosystem services-A case study of the Fenghe River watershed. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.J.; Sun, X.; Zheng, H.; Zhu, P.; Wu, W.B.; Yang, P.; Tang, H.J. Optimizing the ecosystem service flow of grain provision across metacoupling systems will improve transmission efficiency. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 172, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangzhong Municipal People’s Government. Available online: https://www.yz.gov.cn/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Gang, H. A critical-holistic approach to the place-specific geographies of inhabited river islands on the rural-urban fringe of inland China. Shima-Int. J. Res. Into Isl. Cult. 2020, 14, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.S.; Qi, C.F.; Xue, B.; Yang, Z.Q. Measuring urban-rural integration through the lenses of sustainability and social equity: Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2025, 165, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.L. On integrated urban and rural development. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Sun, Q.; Zou, L.L. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving mechanism of rural production-living-ecological space in Pingtan islands, China. Habitat Int. 2023, 137, 102833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Xu, S.; Guo, F.Y.; Xu, L.; Yin, S. Spatial differentiation and influencing factors of rural-area multi-functionality in Hebei province based on a spatial econometric model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 773259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.S.; Nguyen, T.D.; Francois, J.R.; Ojha, S. Rural sustainability methods, drivers, and outcomes: A systematic review. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1226–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fang, B.; Yin, R.M.; Rong, H.F. Spatial-temporal change and collaboration/trade-off relationship of “production-living-ecological” functions in county area of Jiangsu province. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 2363–2377. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.C.; Zhang, B.Z.; Ye, S.N.; Grigoryan, S.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Hu, Y.K. Spatial Pattern and Coordination Relationship of Production-Living-Ecological Space Function and Residents’ Behavior Flow in Rural-Urban Fringe Areas. Land 2024, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrouse, B.C.; Semmens, D.J. Social Values for Ecosystem Services, Version 2.0 (SolVES 2.0): Documentation and User Manual. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1023/contents/OF12-1023.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Zhang, Z.C.; Zhang, H.J.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.R.; Liu, K. Evaluation of Social Values for Ecosystem Services in Urban Riverfront Space Based on the SolVES Model: A Case Study of the Fenghe River, Xi’an, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, K.; Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.N.; Li, X.Q.; Gu, C. Assessment of the social value of ecosystem services based on SolVES model and visitor’s preference: A case study of Taibai Mountain National Forest Park. Chin. J. Ecol. 2017, 36, 3564–3573. [Google Scholar]

- Swets, J.A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 1988, 240, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.Y.; Xiang, J.Y.; Tao, Y.; Tong, C.F.; Che, Y. Mapping the social values for ecosystem services in urban green spaces: Integrating a visitor-employed photography method into SolVES. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.J. Development of ecosystem services evaluation models: Research progress. Chin. J. Ecol. 2013, 32, 3360–3367. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, B.; Lyu, Y.P.; Yang, K.; Che, Y. Assessment of the social values of ecosystem services based on SolVES model: A case study of Wusong Paotaiwan Wetland Forest Park. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 27, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Qin, K.; Tian, T. Assessment and analysis of social values of cultural ecosystem services based on the solves model in the Guanzhong-Tianshui Economic Region. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 3673–3681. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Y.H.; Liu, C.J.; Chen, Y.; Lai, L.Y. Decision research on rural residents’ clean energy applied behavior based on a SEM model. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.H.; Liu, J.; Su, H.X.; Liao, N.Y.; Chen, M.Y. Farmers’ dependency index of ecosystem services and influencing factors in nature reserves based on the Structural Equation Model with formative indicators. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 7417–7430. [Google Scholar]

- Yetim, N.; Yetim, U. Sense of Community and Individual Well-Being: A Research on Fulfillment of Needs and Social Capital in the Turkish Community. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 115, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.B.; Zhai, T.L.; Bi, Q.S.; Chang, M.Y.; Li, L.; Ma, Z.Y.; Li, Y.C. Ecological management zoning in the Yellow River Basin based on hierarchy of needs theory and ecosystem services supply and demand. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2024, 44, 6513–6526. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L. Research on constructing the mechanisms of matching supply and demand of rural public services from the perspective of supply-demand balance theory. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2023, 55, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.H. Rural regional system and rural revitalization strategy in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2019, 74, 2511–2528. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Reed, P.; Raymond, C.M. Mapping place values: 10 lessons from two decades of public participation GIS empirical research. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 116, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrouse, B.C.; Clement, J.M.; Semmens, D.J. A GIS application for assessing, mapping, and quantifying the social values of ecosystem services. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riper, C.J.V.; Kyle, G.T.; Sutton, S.G.; Barnes, M.; Sherrouse, B.C. Mapping outdoor recreationists’ perceived social values for ecosystem services at Hinchinbrook Island National Park, Australia. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K. Assessing and mapping recreationists’ perceived social values for ecosystem services in the Qinling Mountains, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 39, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Tangarife, C.; de la Barrera, F.; Salazar, A.; Inostroza, L. Monitoring the effects of land cover change on the supply of ecosystem services in an urban region: A study of Santiago-Valparaíso, Chile. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucioki, M.; Sowerwine, J.; Sarna-Wojcicki, D.; Lake, F.K.; Bourque, S. Conceptualizing Indigenous Cultural Ecosystem Services (ICES) and Benefits under Changing Climate Conditions in the Klamath River Basin and Their Implications for Land Management and Governance. J. Ethnobiol. 2021, 41, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.Q.; Xu, L.H.; Ma, Q.W.; Shi, Y.J.; Feng, M.; Lu, Z.W.; Wu, Y.Q. Evaluation of the level of park space service based on the residential area demand. Urban Frestry Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.J.; Kou, J.T. Research on the Resilience Evaluation of Rural Ecological Landscapes in the Context of Desertification Prevention and Control: A Case Study of Yueyaquan Village in Gansu Province. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 577–590. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.W.; Zhou, C.; Richardson-Barlow, C. Towards Stringent Ecological Protection and Sustainable Spatial Planning: Institutional Grammar Analysis of China’s Urban-Rural Land Use Policy Regulations. Land 2025, 14, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhao, R. Factors influencing the risk of returning to poverty and the mechanism of action in rocky desertification ecological fragile area. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 222–232. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Lin, L.; Xu, Q.; Hu, C.X.; Zhou, M.M.; Liu, J.H.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, K. Farmland Zoning Integrating Agricultural Multi-Functional Supply, Demand and Relationships: A Case Study of the Hangzhou Metropolitan Area, China. Land 2021, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Carmona, N.; Hart, A.K.; DeClerck, F.A.J.; Harvey, C.A.; Milder, J.C. Integrated landscape management for agriculture, rural livelihoods, and ecosystem conservation: An assessment of experience from Latin America and the Caribbean. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 129, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level-1 Values | Level-2 Values | Perceptual Indicators | Indicator Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production Value | Livelihood Security Value | Perception of Food Security | Perception of the stability of land output and agricultural product supply |

| Resource Utilization Value | Perception of Land Efficacy | Perception of farmland quality and utilization efficiency | |

| Sense of Gain from Resource Development | Perception of fairness in benefit distribution from agricultural land and mineral resource development | ||

| Agricultural Experience Value | Sense of Participation in Agro-processing | Sense of achievement from participating in the extension of the agricultural industry chain | |

| Perception of Agricultural Economic Returns | Satisfaction with market returns from agricultural products | ||

| Living Value | Residential Experience Value | Perception of Housing Comfort | Perception of housing quality and environmental adaptation |

| Perception of Facility Convenience | Perception of accessibility to infrastructure (e.g., transportation, water conservancy) and public services (e.g., education, healthcare, elderly care) | ||

| Employment Value | Perception of Employment Opportunities | Perception of the availability of local employment opportunities | |

| Cultural Identity Value | Perception of traditional Inheritance | Perception of the degree of traditional cultural inheritance | |

| Enjoyment of Cultural Tourism Experiences | Evaluation of rural cultural tourism development and satisfaction with related activities | ||

| Therapeutic Value | Perception of Environmental Comfort | Perception of the comfort level of the rural humanistic and natural environment | |

| Experience of Physical and Mental Restoration | Perception of the therapeutic effects of the rural environment on physical and mental health | ||

| Education Value | Sense of Gain in Education Opportunities | Perception of access to education (including basic education, production skills training, and nature appreciation) | |

| Ecological Value | Ecosystem Regulation Value | Perception of Climate Regulation | Perception of the climate regulation effects provided by the countryside |

| Perception of Hydrological Security | Perception of flood control and drought resistance capabilities | ||

| Ecosystem Provision Value | Perception of Water Purity | Perception of the water quality purity in rivers, lakes, etc. | |

| Recognition of Eco-friendly Food | Perception of the ecological attributes of agricultural products | ||

| Ecosystem Support Value | Appreciation of Ecological Landscapes | Esthetic pleasure derived from natural landscapes | |

| Perception of Species Richness | Awareness level of biodiversity | ||

| Future Value | Future Value | Contemporary Identity | Identification with contemporary rural production and living modes |

| Questionnaire Module | Data Types |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | Gender, age, education level, annual household income, occupation, place of residence |

| Supply Perception | RSV supply level perception scores, spatial locations of value sources |

| Demand Preference | RSV demand preference importance scores, spatial locations of demand points |

| Characteristic | Category | Number of Respondents | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 192 | 50.39 |

| Female | 189 | 49.61 | |

| Age | Under 20 | 62 | 16.27 |

| 20–29 | 77 | 20.21 | |

| 30–39 | 59 | 15.49 | |

| 40–49 | 22 | 5.77 | |

| 50–59 | 62 | 16.27 | |

| 60 and above | 99 | 25.98 | |

| Education Level | Below high school | 152 | 39.90 |

| High school | 82 | 21.52 | |

| Associate degree | 45 | 11.81 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 80 | 21.00 | |

| Graduate degree | 22 | 5.77 | |

| Annual Household Income (CNY) | Under 10,000 | 29 | 7.61 |

| 10,000–49,999 | 38 | 9.97 | |

| 50,000–99,999 | 54 | 14.17 | |

| 100,000–149,999 | 110 | 28.87 | |

| 150,000–199,999 | 83 | 21.78 | |

| 200,000 and above | 67 | 17.59 | |

| Place of Residence | Yangzhong urban area | 63 | 16.54 |

| Yangzhong rural area | 278 | 72.97 | |

| Other areas in Jiangsu | 25 | 6.56 | |

| Outside Jiangsu | 15 | 3.94 |

| Data Category | Data Type | Source and Processing Description |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative Boundaries | Vector | Extracted from 2020 Land Use Data of Yangzhong City |

| Land Use | Raster (10 m) | Original vector data sourced from the Yangzhong Natural Resources Department (2020), converted to raster using ArcGIS 10.2 |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | Raster (10 m) | 91 Weitu Assistant (Enterprise Edition) (2021) |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | Raster (30 m) | National Science and Technology Resource Sharing Service Platform (2022) http://www.nesdc.org.cn/sdo/detail?id=60f68d757e28174f0e7d8d49 (accessed on 12 August 2025) |

| Transportation Network | Vector | Open Street Map (2025) |

| Fit Index | x2 | DF | x2/DF | IFI | GFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion | / | / | <5 | >0.9 | >0.9 | >0.9 | <0.08 |

| Measured Value | 60.919 | 37.000 | 1.646 | 0.973 | 0.966 | 0.972 | 0.048 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Fang, B.; Fan, T.; Wang, Y. Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Supply–Demand Matching of Rural Social Values: A Case Study of Yangzhong City, Jiangsu Province. Land 2025, 14, 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122367

Zhang Z, Fang B, Fan T, Wang Y. Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Supply–Demand Matching of Rural Social Values: A Case Study of Yangzhong City, Jiangsu Province. Land. 2025; 14(12):2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122367

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhicheng, Bin Fang, Tongtong Fan, and Yirong Wang. 2025. "Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Supply–Demand Matching of Rural Social Values: A Case Study of Yangzhong City, Jiangsu Province" Land 14, no. 12: 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122367

APA StyleZhang, Z., Fang, B., Fan, T., & Wang, Y. (2025). Spatial Characteristics and Influencing Factors in Supply–Demand Matching of Rural Social Values: A Case Study of Yangzhong City, Jiangsu Province. Land, 14(12), 2367. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14122367