1. Introduction

Urban Green Spaces (UGS), such as parks, urban forests, gardens, and green corridors, are a critical element of sustainable urban development, as they offer a range of environmental, social, and health benefits to city dwellers [

1,

2,

3]. UGS contribute to reducing temperatures through heat absorption, improving air quality, reducing noise, supporting biodiversity, and enhance the physical and mental well-being of urban residents [

1,

4,

5]. In the context of rapid urbanization, the equitable distribution and accessibility of green spaces have become central to discussions on environmental justice and sustainable urban development [

6].

Despite their benefits, UGS are not distributed equitably within cities, and often reflect or reinforce existing socio-spatial inequalities [

7,

8,

9]. The debate on environmental justice in urban space has emerged as one of the key scientific and political issues of the 21st century, especially in the light of climate change, urbanization, and increasing social inequality. Equitable distribution and access to urban green spaces are now recognized indicators of social and environmental well-being [

10,

11].

The term “green justice” refers to equal access to quality green spaces, regardless of social status, age, or other demographic characteristics [

11]. Studies have shown that socially vulnerable groups, such as low-income populations, children, and the elderly, are often underserved, as they live in areas with limited or difficult access to green spaces [

12,

13].

Traditional urban planning has often ignored the social dimension of green space distribution, focusing only on the total green area or the presence of parks. However, recent studies support a multifactorial approach, which takes into account not only spatial distribution, but also social need and accessibility [

14].

This “green inequality” has emerged as a critical challenge for urban planners and policymakers seeking to promote inclusive, equitable, and sustainable cities [

15,

16]. Thus, in recent years, there has been growing interest in assessing the distribution and accessibility of urban green space using social criteria, with the aim of identifying inequalities related to the location, population density, and socio-demographic characteristics of residents. To capture these inequalities, scholars have developed multidimensional frameworks that assess green equity along three main dimensions: availability, accessibility, and need [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Availability primarily refers to the amount of green space in a given urban area, often expressed through metrics such as green space per inhabitant or the percentage of green space per administrative unit. These indicators offer a first-level approximation of how much green space is available to city dwellers [

18].

Accessibility concerns the proximity and ease with which people can reach green spaces [

21]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that every citizen should live within 300 m (5 minutes’ walk) of accessible green spaces [

2], but this target remains unmet in many urban settings. The quality of walking infrastructure, physical barriers (such as highways or railways), and entry restrictions can significantly influence perceived and actual access. Inequalities within neighborhoods are particularly significant in large cities, where average accessibility can mask strong internal inequalities. Geospatial analyses using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) technologies have enabled detailed assessments of walking access, allowing for a more accurate assessment of the equity of green spaces [

22,

23,

24].

The need dimension relates to demographic and social characteristics that indicate increased demand for or dependence on green spaces, particularly among vulnerable populations. Common indicators include population density, the proportion of children, and the proportion of elderly residents, groups that are more likely to benefit from nearby green spaces for recreation, socialization, and health [

17,

25]. High-density urban areas typically experience increased demand for public green spaces, but often suffer from lower provision, exacerbating inequality [

26]. Children and the elderly are particularly vulnerable to local accessibility due to limited mobility and specific health needs [

25]. Incorporating demographic indicators into spatial assessments is therefore crucial for understanding who is most deprived of green space.

Recent efforts in green justice research have focused on mapping the intersection of sociodemographic vulnerability and spatial green deficits through composite indicators and vulnerability indices [

22,

27]. Thus, the measurement of green inequality has evolved from simple indicators of green cover to complex models that combine geospatial, social, and access data. The combination of these dimensions is considered essential for understanding environmental (in)equality in the urban fabric.

In Europe, the European Commission has highlighted the importance of green infrastructure through strategies such as the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 [

28], which calls for “bringing nature back into our lives” and improving access to green spaces, especially in urban environments. Similarly, the European Environment Agency (EEA) has highlighted the need for spatially explicit assessments of green space provision, particularly in light of increasing socio-economic inequalities and urban density [

29].

Comparisons between European cities have revealed clear geographical trends in the distribution of UGS. Northern and Central European cities tend to have higher overall green coverage and more equitable access, compared to Mediterranean and Eastern European cities, which exhibit high inequalities, low green density, and fragmented spaces [

29]. These differences are not only geographical but also institutional, as they are linked to the presence or absence of long-term urban planning and green strategies. However, the comparative assessment of “green justice” at the intra-city level between European cities remains limited [

30], mainly due to the lack of harmonized data and multifactor measurement tools.

In this context, this study aims to develop and implement a composite Urban Green Equity Index (UGEI) in 26 European capitals. This index is based on three main axes, (a) the availability of green spaces, (b) their accessibility, and (c) social need, as expressed by population density and the composition of vulnerable age groups. Through the UGEI, the research aspires to capture the multidimensional spatial inequalities in urban green spaces in a holistic way, contributing to the empirical documentation of environmental (in)equality in European urban space. This research provides the first harmonized and comparative assessment of urban green space inequalities across European capitals. By systematically mapping spatial inequalities in the distribution of green spaces, this study contributes to the growing literature on environmental justice in urban Europe and offers actionable insights for local government policies, promoting just green transitions.

2. Materials and Methods

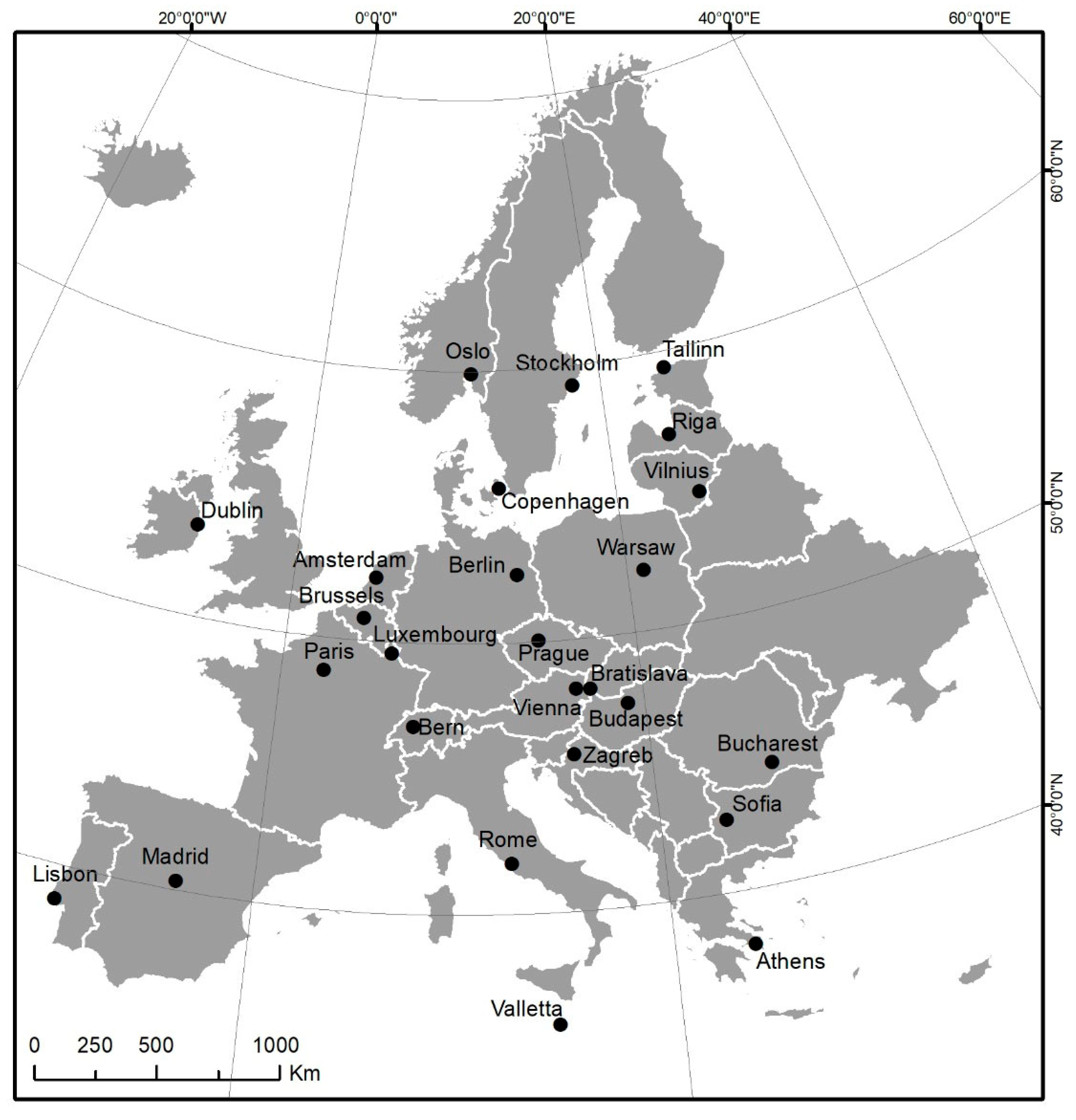

This study focuses on 26 European capitals (

Figure 1) (Amsterdam, Athens, Berlin, Bern, Bratislava, Brussels, Bucharest, Budapest, Copenhagen, Dublin, Lisbon, Luxembourg, Madrid, Oslo, Paris, Prague, Riga, Rome, Sofia, Stockholm, Tallinn, Valletta, Vienna, Vilnius, Warsaw, and Zagreb), for which urban green equity is examined through the construction of the composite index UGEI.

The selection of cities was based solely on the availability of harmonized and comparable data in the datasets used. The aim was to achieve the widest possible geographical coverage of Europe, rather than limiting the study to European Union member states.

The UGEI is a composite indicator that captures the spatial distribution of green space availability, accessibility, and population-based need, enabling an integrated assessment of UGS justice.

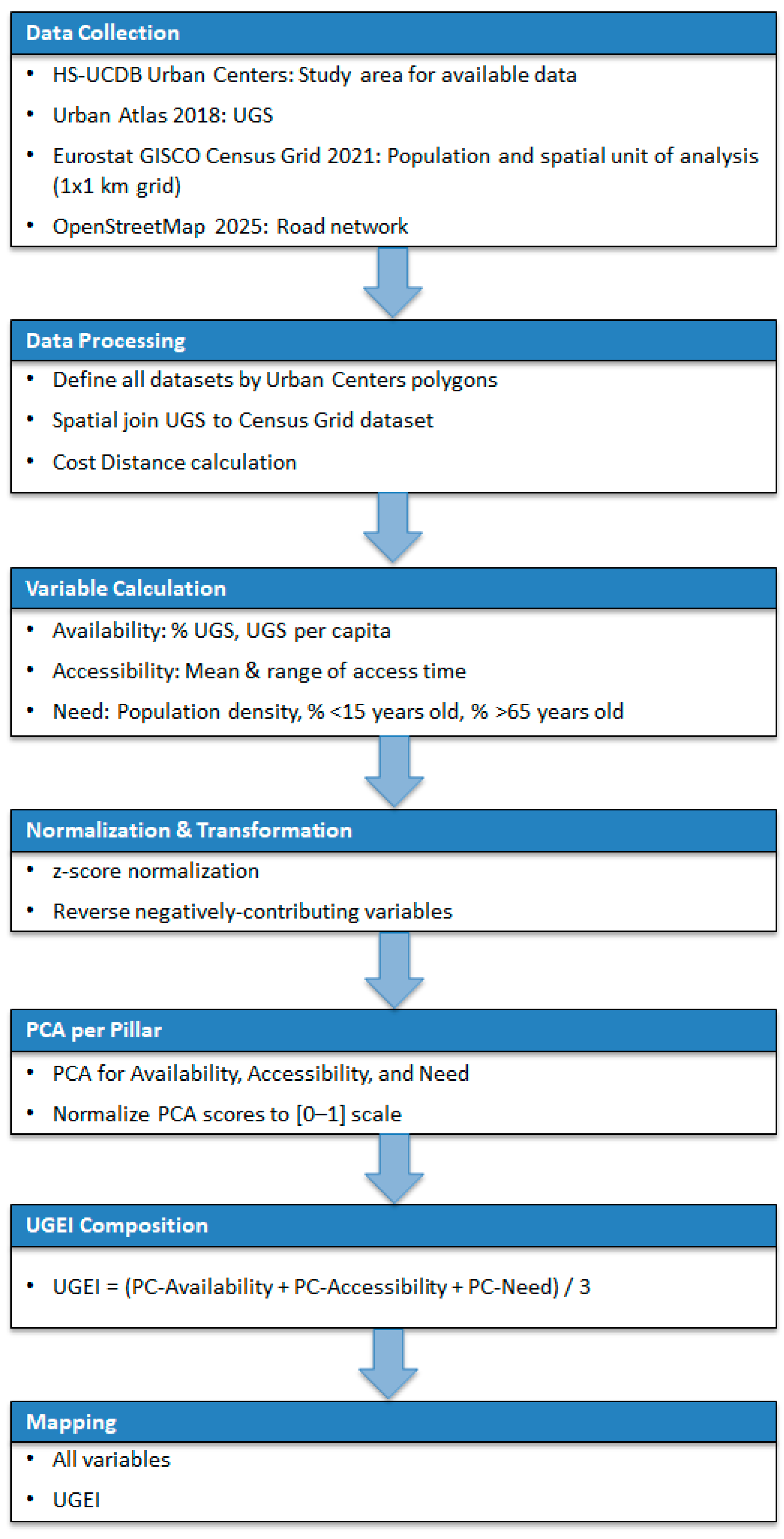

The UGEI was based on the synthesis of seven individual variables to assess the three thematic pillars of green justice (

Table 1), and the methodological framework for its calculation is presented in

Figure 2.

2.1. Data Sources and Description

The geographical delimitation of the analysis for each city was based on the set of “Urban Centres” as defined in the Global Human Settlement Database—Urban Centre Database (GHS-UCDB), developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) within the framework of the Copernicus Emergency Management Service [

31]. This dataset provides polygonal spatial entities representing the main urban formations of cities. The resulting area was used as a spatial filter to exclude all other data used in the subsequent analysis.

The Urban Atlas 2018 dataset [

32] was used to estimate the UGS. From the set of categories, the thematic classes corresponding to “Green Urban Areas” and “Forests” were extracted, which represent the coverage of greenery found in urban areas.

To represent population characteristics, the census grid geospatial dataset of Eurostat GISCO (Geographic Information System of the Commission) was used, which is a polygon-based grid of 1 × 1 km covering the whole of Europe [

33]. Each polygon contains information on the total number of inhabitants, as well as specific population groups such as children under 15 and elderly people over 65. The spatial data of this dataset (1 × 1 km grid) also constituted the spatial unit of analysis for this study.

In addition to the Urban Atlas, data from OpenStreetMap (OSM) were used to calculate accessibility to UGS. Linear data on the road network were extracted from OSM and used to estimate the travel time from each cell of the population grid to the nearest UGS area.

2.2. Spatial Analysis and UGEI Construction

All of the above data were transformed into the ETRS89-LAEA (EPSG:3035) reference system to ensure spatial compatibility and accuracy in the calculation of distances and areas.

The UGS area per capita was calculated by dividing the total UGS area within each grid polygon by the population of the polygon, while the percentage coverage of UGS (as a percentage of the total area of the polygon) was also calculated.

The calculation of the access time to the nearest UGS was based on pedestrian traffic on the road network, as in densely built-up urban environments, free direct access to green spaces is obstructed by natural and artificial barriers, such as buildings, fences, and private property. Therefore, the use of the road network provides a more realistic representation of accessibility as experienced by pedestrians.

The analysis focuses exclusively on pedestrian access, and an average walking speed of 4.8 km per hour was selected, a value widely used in the literature in relevant walkability studies [

34,

35]. This speed corresponds to the average walking speed of adults without mobility problems and is often used in spatial models of isochrone analyses.

The Cost Distance algorithm was used to estimate access time, which calculates the minimum cumulative “cost” (in this case, time) required to travel from any point on the surface to the nearest UGS. The spatial analysis of the cost surface was set at 1 m in order to accurately reflect the complexity of the urban fabric and the variation in distance on a small scale. The calculation included not only UGSs within the boundaries of urban centers, but also those located in neighboring areas outside urban boundaries, in order to realistically reflect residents’ accessibility. In practice, city residents often have the opportunity to visit nearby green spaces that lie beyond the administrative or theoretically defined boundaries of the city. This ensured that the analysis captured residents’ actual choices in relation to available UGS.

The analysis was applied to the entire area of urban centers for each capital, creating a continuous map of access time in minutes on the road network. Next, the average access time within each population grid and the access time range (the difference between the maximum and minimum values within the same polygon) were calculated as an indication of intra-spatial inequality within the grid, in order to record the unequal distribution of access among residents living in the same spatial context.

Finally, the total population density, the percentage of children under 15, and the percentage of elderly people over 65 per population grid were calculated. These variables highlight the social need for access to green spaces, both in terms of overall population concentration and the presence of vulnerable demographic groups.

The values of all variables were normalized using the z-score statistical transformation. In order to maintain a consistent direction in the calculation of the index, variables that are negatively related to the concept of equality in green spaces, i.e., those where an increase implies a deterioration (such as distance, population density, or the percentage of vulnerable groups), were inverted. The exception was variables that already express a positive contribution, such as UGS per capita and the UGS percentage.

Subsequently, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed for each pillar with the aim of condensing multiple variables into a single axis that explains the maximum possible variance. For each pillar, only the first principal component that satisfied the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue > 1) was retained. The values of the principal components were further normalized to the scale [0, 1] to make them comparable across pillars. To ensure that the resulting components were not affected by multicollinearity, a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis was conducted on the three principal components. The final composite UGEI was calculated as the average of the three normalized principal components corresponding to the pillars of availability, accessibility, and need.

For the UGEI, as for most variables, the average was also calculated, both at the city level and at the overall level, as a summary descriptive value, with the aim of facilitating the interpretation of the results and the comparison of values both within and among cities. An exception was the UGS per capita variable, for which the median was used as the central value due to the strong asymmetry in the value distribution.

Finally, all variables, as well as the composite UGEI, were mapped, allowing for a visual reading of spatial inequalities in access to urban green space both at the city level and within individual urban areas.

Spatial data analysis and mapping were performed using ArcMap 10.4 software, while PCA was performed using GeoDa 1.16.0.12.

3. Results

PCA was applied separately for the three pillars of the index, aiming to condense the respective variables into a single axis per pillar. In all pillars, only the component with an eigenvalue greater than 1 (Kaiser criterion) was retained, which captures the basic dimension of each theme and was used to calculate the composite UGEI (

Table 2). For the availability pillar, the first component (eigenvalue = 1.221) explains 61% of the total variance and is characterized by an equal contribution of the variables % UGS and UGS per capita (loadings 0.707). In the accessibility pillar, the first component (eigenvalue = 1.692) explains 84.6% of the variance, with equal contributions from the mean and range of access time (loadings 0.707). Finally, for the need pillar, the first component (eigenvalue = 1.498, 49.9% variance) is mainly determined by the population under 15 years old (−0.705) and the population over 65 years (0.674), while the population density shows only a weak loading on this component (0.221).

The VIF analysis that was conducted on the three principal components revealed that all VIF values were below 1.2, confirming the absence of excessive collinearity among the final indicators.

The mapping of UGEI and its variables indicates significant differences both among the cities and within them. The thematic maps present the conditions regarding the availability and accessibility of urban greenery, as well as the composition of the population, allowing for a comparative evaluation.

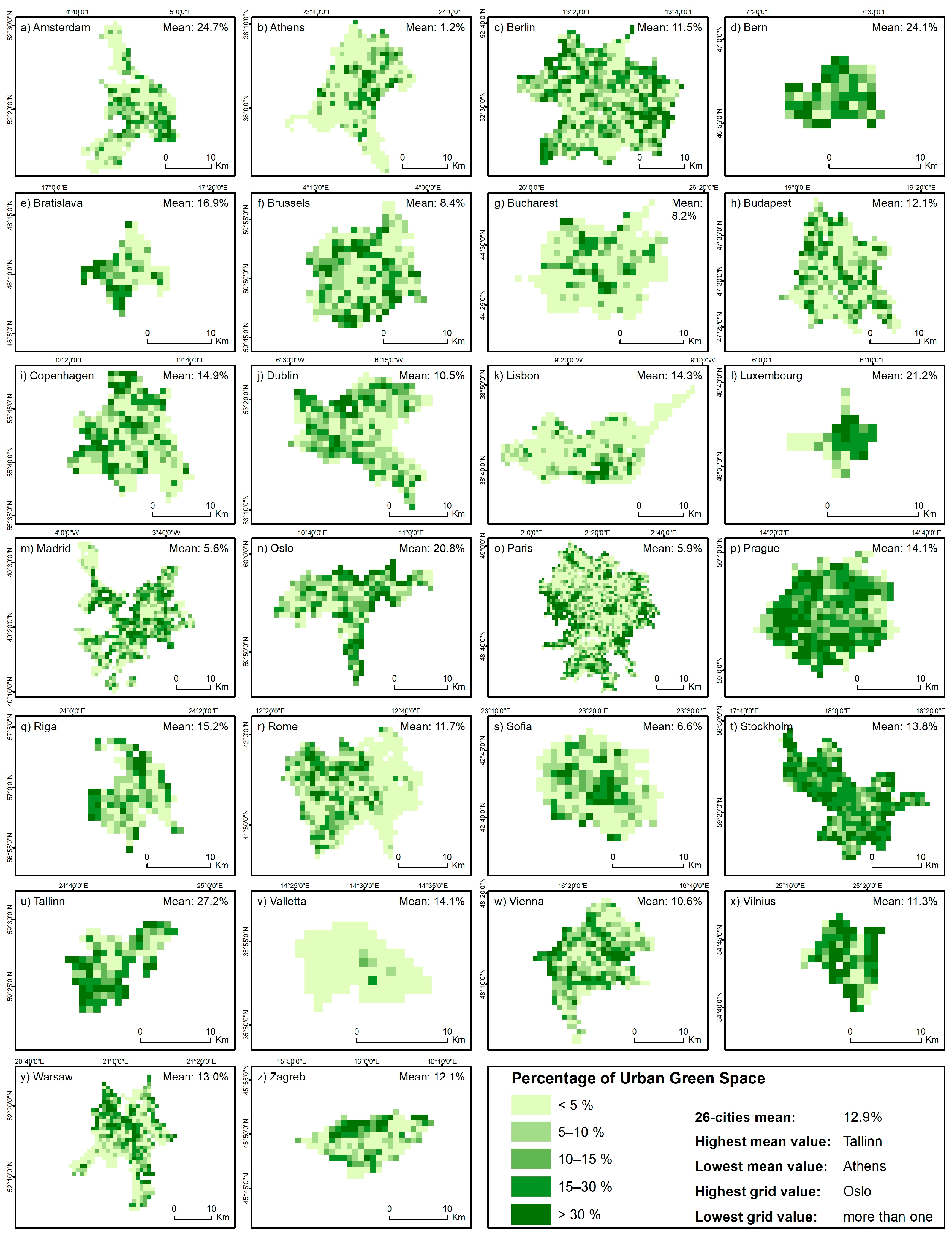

The distribution of the percentage of urban green space shows a marked spatial imbalance (

Figure 3). The highest average value is recorded in Tallinn with 27.2%, followed by Amsterdam (24.7%) and Bern (24.1%), where there are contiguous areas with extensive UGS coverage. In contrast, the lowest average values are found in Athens (1.2%), Madrid (5.6%), and Paris (5.9%), which have either fragmented green spaces or areas almost lacking any UGS. Some cities, such as Bucharest, Paris, and Sofia, are characterized by a mosaic of variations, with areas of low and medium coverage coexisting without a clear spatial trend.

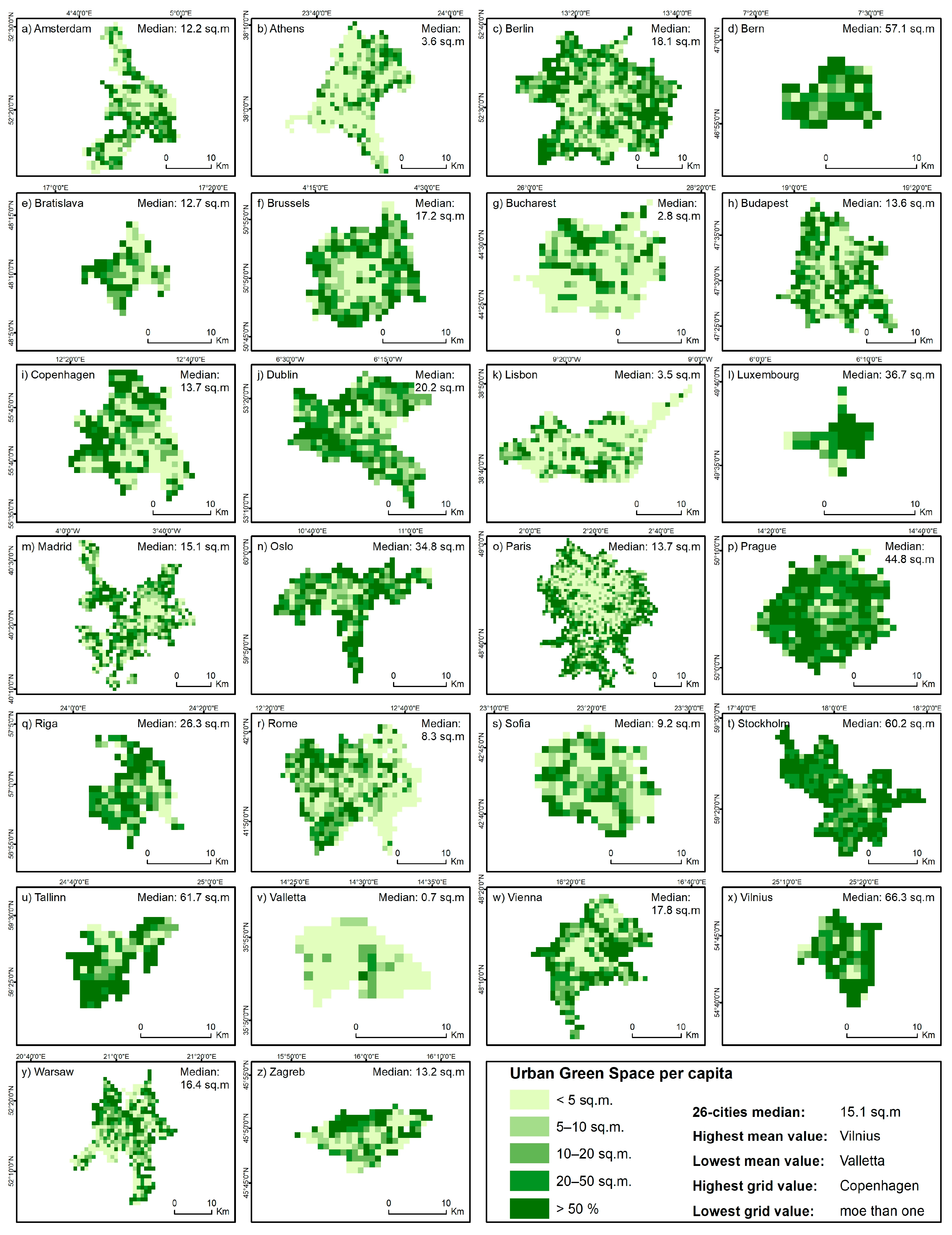

The UGS per capita reveals even more pronounced intra-urban and inter-city disparities (

Figure 4). The average levels of the variable range from just 0.7 sq.m. per capita in Valletta to 66.3 sq.m. in Vilnius, demonstrating a difference of almost 95 times between the two extremes of the variable. High levels are also recorded in Tallinn (61.7 sq.m.) and Stockholm (60.2 sq.m.), while in cities such as Bucharest (2.8 sq.m.), Lisbon (3.5 sq.m.) and Athens (3.6 sq.m.), the values remain extremely low. The average UGS per capita level for the 26 cities is 15.1 sq.m., with several European capitals falling below this threshold. At the intra-urban level, it is observed that in many cases, even cities with a relatively satisfactory overall UGS presence have areas with very low values per capita. The maps clearly show local phenomena of overconcentration of green space in areas with low population density, but also urban areas with minimal green space and high residential density. The gradation is pronounced in cities such as Berlin, Paris, Rome, and others, where areas with very low and very high values coexist.

In terms of mean access time to UGS, the results show that in several cities, the majority of the population has access within less than 5 min, especially in cities with dense and evenly distributed green spaces such as Stockholm, Prague, and Vilnius (

Figure 5). In contrast, the highest mean access times are found in Valletta (9.2 min), Bucharest (7.9 min), Lisbon (7.8 min), and Rome (7.6 min), indicating greater distances between residents and the nearest UGS. The maps reveal that cities with high access values often exhibit patterns of regional isolation, with areas on the outskirts of urban centers being at a significant disadvantage in terms of proximity to green spaces. This phenomenon is more pronounced in cities with a dense central built-up area and a sparser presence of UGS on the outskirts, such as Rome, Vienna, and Athens.

While the mean access time provides a general overview for each population grid polygon, it fails to reflect potential intra-grid variability, which may lead to the calculation of deceptively low mean times. In several cases, residents of the same area may be significantly closer to or further away from the nearest UGS, highlighting the need for further investigation of intra-spatial differentiation.

The range of access time per grid provides indications of internal homogeneity or inequality of access to green spaces. In several cities, there are grids where residents have almost equal access (low range), which is mainly found in Northern European cities (

Figure 6). In contrast, in cities such as Rome, Valletta, Bucharest, and Lisbon, there are extensive areas with a high range of access time, revealing intense intra-spatial differentiation even on a small scale.

The maps of the need pillar variables highlight the population patterns of European capitals, focusing on population density and the presence of vulnerable age groups. The average population density for all 26 cities is 5598 residents/sq.km., but the differences between cities are significant and often extensive (

Figure 7). Cities such as Paris, Madrid, and Athens, with values in areas exceeding 15,000 residents/sq.km., have average densities 40–80% higher than the overall average, indicating particularly densely populated urban areas. In contrast, in some cities, such as Bern, Luxembourg, and Valletta, values are at least 30% below the average, reflecting more diffuse or sparse settlement patterns within urban centers. The majority of cities fall within a range of ±25% of the average value, revealing the existence of some strong upward or downward deviations that affect the overall distribution.

Figure 7 illustrates these differences, as in many cities the built-up center has a high population concentration compared to the peripheral areas, which are characterized by sparser settlement and lower built-up density.

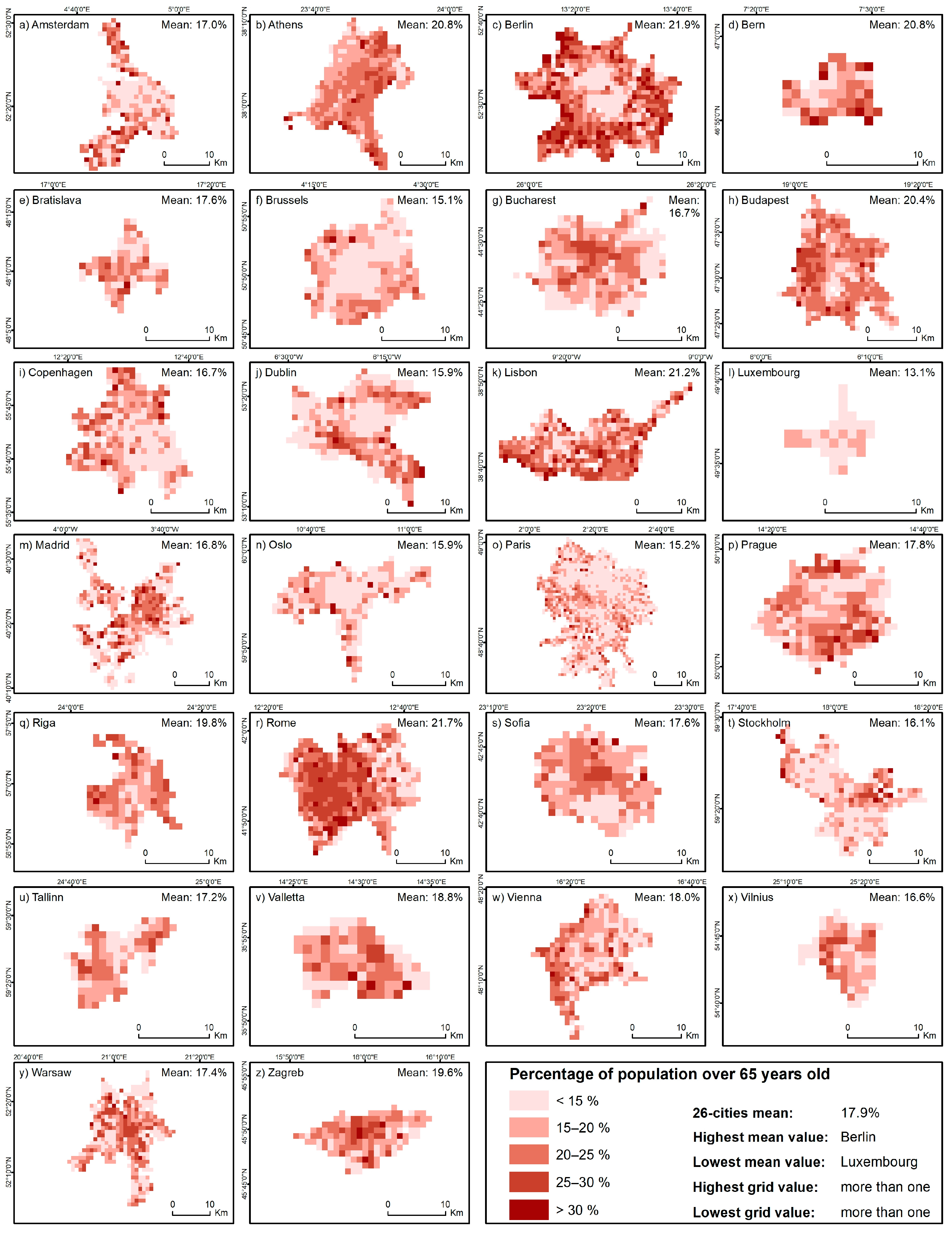

While population density shows local concentrations of high intensity, particularly in the central parts of several cities, the spatial distribution of age groups appears more stable and less polarized compared to variables related to urban greenery (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). The mean percentage of children under 15 for all cities is 16.3%, with the highest mean values observed in Paris (19.8%), Brussels (19%), Stockholm (18.6%), and Oslo (9.7%) (

Figure 8). In contrast, lower percentages of children are found in Valletta (13.2%), Rome (13.5%), Budapest (13.6%), and Berlin (13.9%), cities with a relatively older population profile. For the elderly (65+ years) group, most urban centers range between 16–22%, with slightly higher mean values in Berlin (21.9%), Rome (21.7%), and Lisbon (21.2%), which have higher proportions of elderly people in the urban population compared to other cities (

Figure 9). Although there are no extreme spatial concentrations in the age groups, there are local variations within cities. Higher percentages of children are found in peripheral areas of cities such as Bucharest, Prague, Madrid, and Warsaw, while older people appear to be more concentrated in areas of lower density or more sparsely built, such as areas of Amsterdam, Bern, and Lisbon.

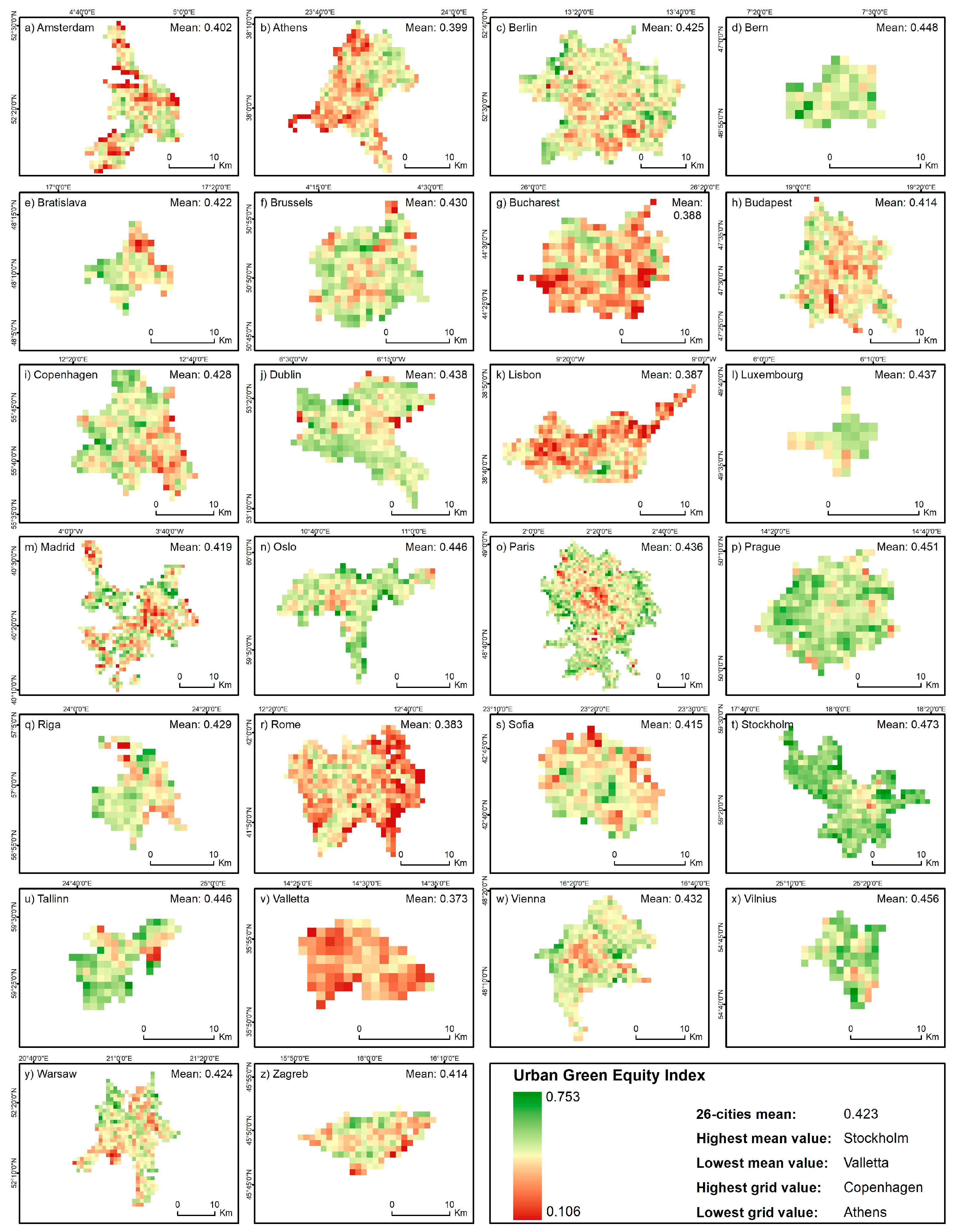

The composite UGEI, as shown in

Figure 10, summarizes the three dimensions of equity in urban greenery: availability, accessibility, and need. The average value of the index for European cities is 0.423, with most Northern European cities above the average and most Southern cities below it. Higher average values are observed in Stockholm (0.473), Vilnius (0.456), Prague (0.451), Bern (0.448), and Oslo and Tallinn (0.446). These cities have larger contiguous areas with relatively high levels of equity, which indicates both high availability and accessibility of UGS in areas with increased social need. In contrast, lower values of the index are recorded in Valletta (0.373), Rome (0.383), Lisbon (0.387), Bucharest (0.388), and Athens (0.399). These cities are characterized by marked spatial inequality, with large areas having low index values and urban green spaces often being fragmented, limited, or poorly accessible.

4. Discussion

This study approaches spatial justice in UGS through the development and application of the composite index UGEI in 26 European capitals, seeking to quantify the multidimensional concept of environmental equity based on three fundamental axes: availability, accessibility, and social need.

The choice of a multifactorial tool is in line with the current methodological shift towards incorporating more than one index to capture the relationship between population and green infrastructure, as the use of one-dimensional measurements has proven insufficient for understanding environmental (in)equality in urban areas [

36]. The design of the UGEI is consistent with other composite indices evaluating UGS inequalities, according to which equitable access to urban green space should be assessed through the triad of availability, physical accessibility, and social need [

17,

18,

19,

20]. The incorporation of demographic parameters, such as age composition (children, elderly), reflects the importance of a “need-driven” approach to green network design [

9,

29], as has been argued in studies linking access to green spaces with public health and environmental sustainability indicators [

20,

37,

38]. This emphasis on demographic vulnerability is reflected in the structure of the need component, as the PCA showed that the proportions of younger and elderly residents were the variables most strongly associated with this axis, whereas population density contributed only weakly.

The analysis in this study reveals marked inequalities in the availability, access, and sociodemographic distribution of UGS, both at the transnational and intra-urban levels, confirming and reinforcing findings from international research on the unequal geographical and sociodemographic distribution of environmental goods in cities. Recent studies on urban greening also highlight that such disparities persist in European and global cities, demonstrating that such inequalities constitute a persistent and geographically widespread feature of contemporary urban environments [

39,

40,

41].

The spatial pattern of UGEI appears to result from the interaction of all parameters, which makes even the most complex forms of urban inequality visible. This observation is consistent with studies indicating that a quantitative increase in urban greenery does not automatically imply social justice [

8,

11,

42,

43].

The spatial comparison indicates a clear geographical trend, with northern and Scandinavian cities scoring higher overall, in contrast to southern and Mediterranean cities, which score lower on the UGΕI index. Cities in southern Europe have lower levels of both availability and accessibility to urban green spaces, while in many cases there are large disparities even within the same urban area.

This trend is consistent with recent findings in the international literature, which report a systematic distinction between cities in Northern and Southern Europe regarding UGS. Studies investigating UGS in European cities [

44,

45,

46] document that in cities in Mediterranean countries, green spaces are often concentrated in a few large hubs or peripheral areas, while they are often characterized by lower green space indicators, higher building density, and greater intra-urban variations. In contrast, cities in Northern Europe tend to have more polycentric urban green networks, with strong neighborhood-level connectivity and greater proximity to daily travel [

44,

47].

Similarly, recent findings by the European Environment Agency [

29] confirm that cities in Northern and Western Europe tend to have more total green space compared to cities in Southern and Eastern Europe, while socially vulnerable groups often lack access to quality UGS, even in cities with relatively high levels of overall coverage. The results of the present study consistently follow the above patterns, indicating that geographical location remains a determining factor in spatial inequalities in urban green space.

The poor performance of cities such as Athens, Rome, and Bucharest in terms of the availability and accessibility of urban green space is attributed to historical patterns of unregulated and unplanned urbanization, where priority was given to building development over the protection of public space. The lack of coherent urban planning, the deregulation of spatial planning, and the absence of an institutional framework for green spaces have led to the degradation of environmental infrastructure over time.

On the contrary, cities such as Stockholm and Tallinn confirm that urban planning strategies focused on equal access to green spaces, such as the regional planning of green infrastructure in Sweden or the “green corridors” policy in Estonia, significantly enhance social and environmental cohesion. Recent research shows that green planning at the local level, when it incorporates social and demographic criteria, contributes significantly to reducing environmental inequalities [

7,

48].

However, even in cities with high overall levels of green space, recent research has shown that intra-urban variations may still exist. Studies examining cities in northern Europe, such as Copenhagen, Oslo, and Riga, have identified spatial differences in the distribution and accessibility of green spaces, with some areas showing lower availability or poorer exposure conditions than more privileged neighborhoods [

15,

49,

50]. These findings are consistent with the results of the present study, according to which high overall UGEI values at the city level do not necessarily imply the elimination of local inequalities in the urban fabric. Based on the literature, UGS are often concentrated in areas with low population density and higher socioeconomic characteristics, leaving vulnerable neighborhoods without adequate access [

30]. Recent work has shown that socially disadvantaged communities consistently experience poorer access to high-quality green spaces, even within green-rich cities [

12,

51]. The need for targeted interventions in socially vulnerable areas is therefore particularly urgent.

However, the study has certain limitations that must be acknowledged in order to interpret the findings correctly. First, the analysis is based on land use data (Urban Atlas 2018) and 1 × 1 km polygon-based grid data, which offer unified coverage and comparability but may not capture small-scale variations, especially in densely populated areas with intense micro-spatial complexity. Furthermore, the use of the road network access time calculation method assumes homogeneous pedestrian mobility and does not take into account obstacles such as steep slopes, high crime areas, or socially “invisible” boundaries, which affect the actual use of green spaces. In addition, the use of a uniform average walking speed (4.8 km/h) may not fully reflect the differences between age groups or groups with different mobility levels. Although this value is widely used in international literature for walkability and accessibility studies, the lack of available, harmonized data for different population categories, as well as the absence of information on mobility conditions and related pedestrian infrastructure for people with limited mobility, does not allow for the application of distinct speeds in a comparative analysis between cities.

Furthermore, the analysis focuses on pedestrian access to static points (nearest UGS) rather than on the overall quality or functionality of green spaces, which also determine their use and importance. These qualities, such as safety, equipment, esthetics, biodiversity, or cultural content, could not be incorporated into the index due to a lack of harmonized data at the European level, even though the literature recognizes them as determining factors for the sustainability of UGS [

20].

Another important assumption of the study is the equation of social need with age composition and population density. Although these parameters are widely accepted indicators of vulnerability, they do not cover other critical social variables, such as income, ethnic composition, or the existence of disabilities, which are often associated with reduced access to green spaces [

29,

52]. The inclusion of such parameters would enhance the social robustness of the index and provide a more comprehensive understanding of urban inequality.

Finally, there is a temporal inconsistency between the datasets used in the analysis, as they come from different European data providers and correspond to the most recent versions available for each type of data. Although this implies a small time gap, ranging up to approximately seven years (2018–2025), the complete temporal alignment of all variables at the European scale is challenging to achieve. However, given that green spaces and road networks usually remain relatively stable over such short time periods in urban environments, these temporal discrepancies are not expected to substantially affect the overall spatial patterns or the comparative results of the analysis.

Despite the limitations, this study contributes to the empirical and comparative documentation of inequalities in urban greenery in Europe, offering a valuable pan-European picture of green urban justice at the level of capital cities. The development of the composite UGEI allows for the simultaneous capture of availability, accessibility, and need, offering a more holistic understanding of environmental equity compared to one-dimensional indices that focus exclusively on green coverage or proximity.

Furthermore, the use of spatially high-resolution data (1 × 1 km) and the incorporation of social vulnerability parameters, such as age composition and density, enhance the ability to target areas with an increased need for green interventions.

The application of a uniform methodology to geographically and institutionally diverse cities provides a powerful tool for comparative assessment, which is particularly useful for both urban policymakers and the scientific community examining issues of environmental justice and sustainable urban planning. This study advances beyond existing literature by offering a comparative, empirically grounded, and integrated assessment of green equity in European capitals. The combined analysis of the three dimensions of the UGEI, availability, accessibility, and social need, allows for the identification of complex spatial patterns that often remain invisible in one-dimensional approaches. Beyond its contribution to the scientific documentation of inequalities, the study provides operational guidance for policy-making.

The study’s findings are particularly relevant for urban policy. The systematic measurement of the three dimensions of green justice makes the UGEI a useful tool for identifying priorities and documenting targeted interventions. Based on the data collected and analyzed, certain operational guidelines for policy-making emerge: (a) prioritizing areas with low accessibility or high social vulnerability for increasing green space, (b) incorporating socioeconomic and demographic indicators into the spatial planning process, and (c) using the UGEI indicator as a tool for monitoring and evaluating progress towards more equitable and sustainable cities. This systematic approach can support policymakers and city administrations in developing evidence-based green transition strategies in the European context.

Overall, this study highlights the importance of a holistic, socially sensitive, and quantitatively grounded approach to urban greenery assessment, in line with the new generation of research shifting from general surface area measurement to multifactorial environmental justice assessment.

5. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study are based directly on the patterns identified through the spatial results of the UGEI analysis. The mapping results indicated consistent geographical variations and intra-urban inequalities, which form the empirical basis for the study’s broader findings on environmental inequalities. In summary, the study highlighted the multidimensional inequalities of availability, accessibility, and population need for UGS in 26 European capitals, confirming, within the European context, that the quantitative increase in green space does not automatically ensure environmental justice. The composite UGEI allowed a more holistic approach to the phenomenon, providing the possibility for comparative assessment and identification of areas of high need, while underlining the value of integrating social and demographic variables into urban planning.

However, to further deepen the understanding of green inequality, future research could incorporate additional socioeconomic indicators, such as income, ethnic composition, education level, or housing conditions, as well as qualitative characteristics of green spaces (e.g., safety, esthetics, maintenance). Future developments of the index could also integrate functional or ecological attributes through remotely sensed indicators, such as vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) or tree canopy cover, along with survey-based data on user experience and perceptions at the city level. Such extensions would allow a more comprehensive assessment of urban green space equity, linking spatial accessibility with the quality and usability of green areas. Furthermore, the use of longitudinal data and the study of the impacts of green interventions could contribute to the understanding of processes of environmental (in)equality and the dynamics of “green gentrification”. In this context, temporal analyses based on successive Urban Atlas releases or other comparable datasets could deepen knowledge of how green space equity evolves over time in European cities.

These research directions could expand the empirical framework developed in this paper and enhance understanding of how spatial and social structures influence green equity in European cities. Finally, the strengthening of participatory processes in the planning and evaluation of urban green spaces can be a crucial step towards creating cities that are not only sustainable but also more socially just.