3. Results

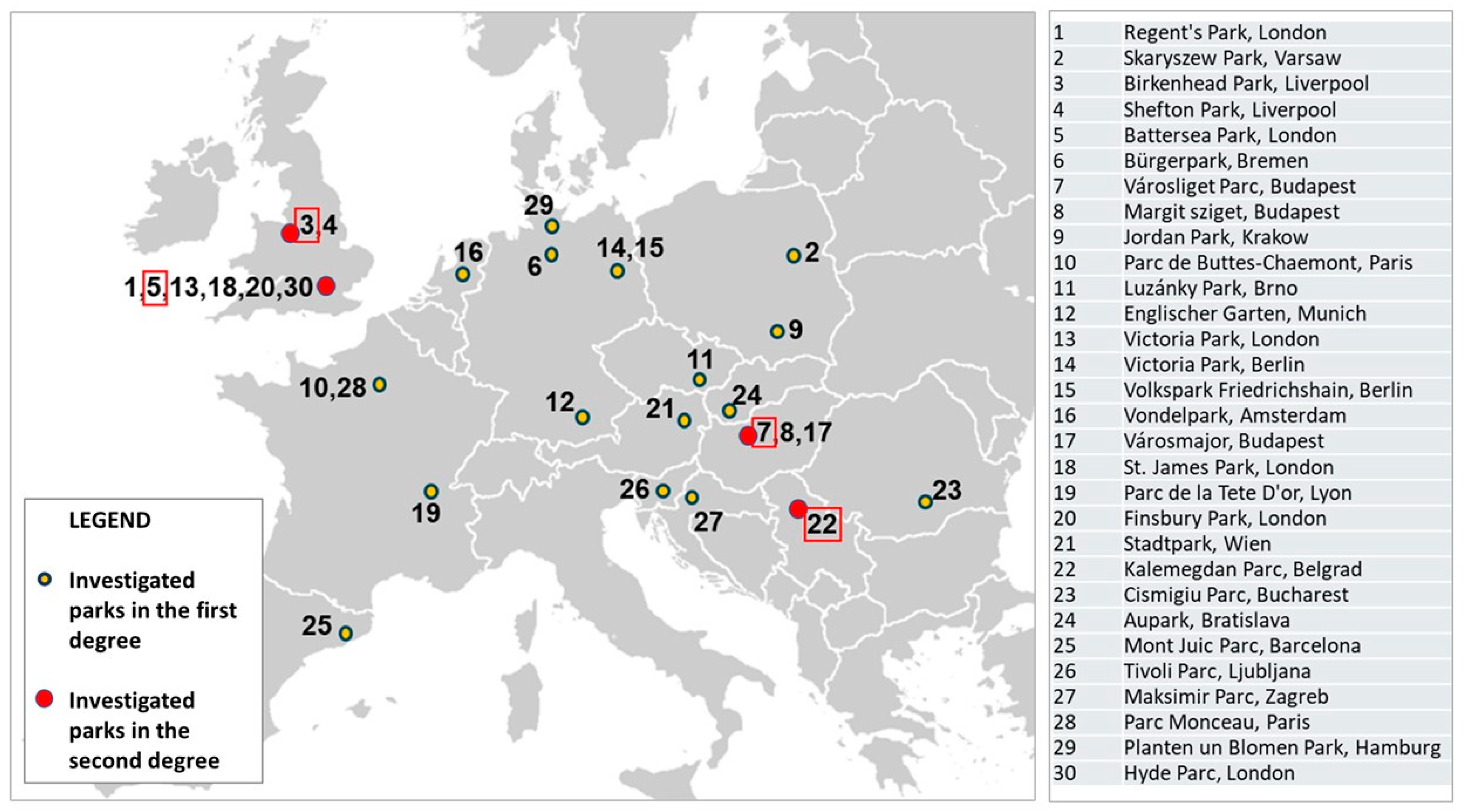

In the first step of the research, we conducted an indirect investigation based on comparison of old and current maps, designs, descriptions, articles and the documentation of the actual conditions of 30 European parks through the involvement of 24 landscape architecture students from different countries, enrolled in the international Master of Landscape Architecture and Garden Art Program at MATE University, Hungary. In this indirect investigation, we included well-known urban parks from 15 different European countries, collecting and analyzing similar basic data regarding each location: the name and size of the park, the urban context, the design period/data and the designer, the structure, main functions, features, plant use and compositional principles of the parks.

More detailed research has been conducted at the second level in the case of four selected urban parks: Birkenhead Park from Liverpool (UK), Battersea Park from London (UK), Városliget Park from Budapest (HU) and Kalemegdan Park from Belgrade (SRB).

From this basic survey, we selected four parks for a deeper investigation due to their basic characteristics. We considered both qualitative and quantitative selection criteria, which were the following:

- I.

There was enough available archival materials and current data in order to evaluate their historical character, development and current conditions;

- II.

They were representative of Western European and Eastern Europe parks in equivalent proportion;

- III.

They were considered representative as historical urban public parks both in their origin country and in the European context;

- IV.

They were established in the first part or middle of the 19th century (the typical time period when public parks started to be opened);

- V.

They have an area over 50 ha;

- VI.

It was possible to have on-site research access during the research period (

Figure 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Design Analysis of the Selected Parks

Social needs, economic growth and climate change undoubtedly affect the function, form and use of public parks. Historical functions of public parks have largely remained, but new functions have also emerged and, consequently, new types of uses and users. Functions as part of the landscape as a natural system become more explicit and extended [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The issue of public health plays a major role in the functioning of public parks [

15]. Not only the parks maintain their traditional role of ‘lungs’ of the city, but this becomes even more important due to the rising air pollution and urban heat island effect [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Water surfaces, fountains and flowing water have a mitigating effect on the urban climate, a principle already practiced in the design of historical gardens [

23]. Social aspects, accessibility, integration, community involvement and democratic use are more and more highlighted in the functional re-evaluation of historical public parks [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

During the research at the selected four locations, our investigation and analysis highlighted functions, main design elements and artistic composition, space structure and canopy coverage, plant composition, visual connections and water and road systems at each location.

As the space limitations of this article do not allow us to present a detailed history of all four selected parks, we will focus on the comparative analyses carried out according to the criteria described above.

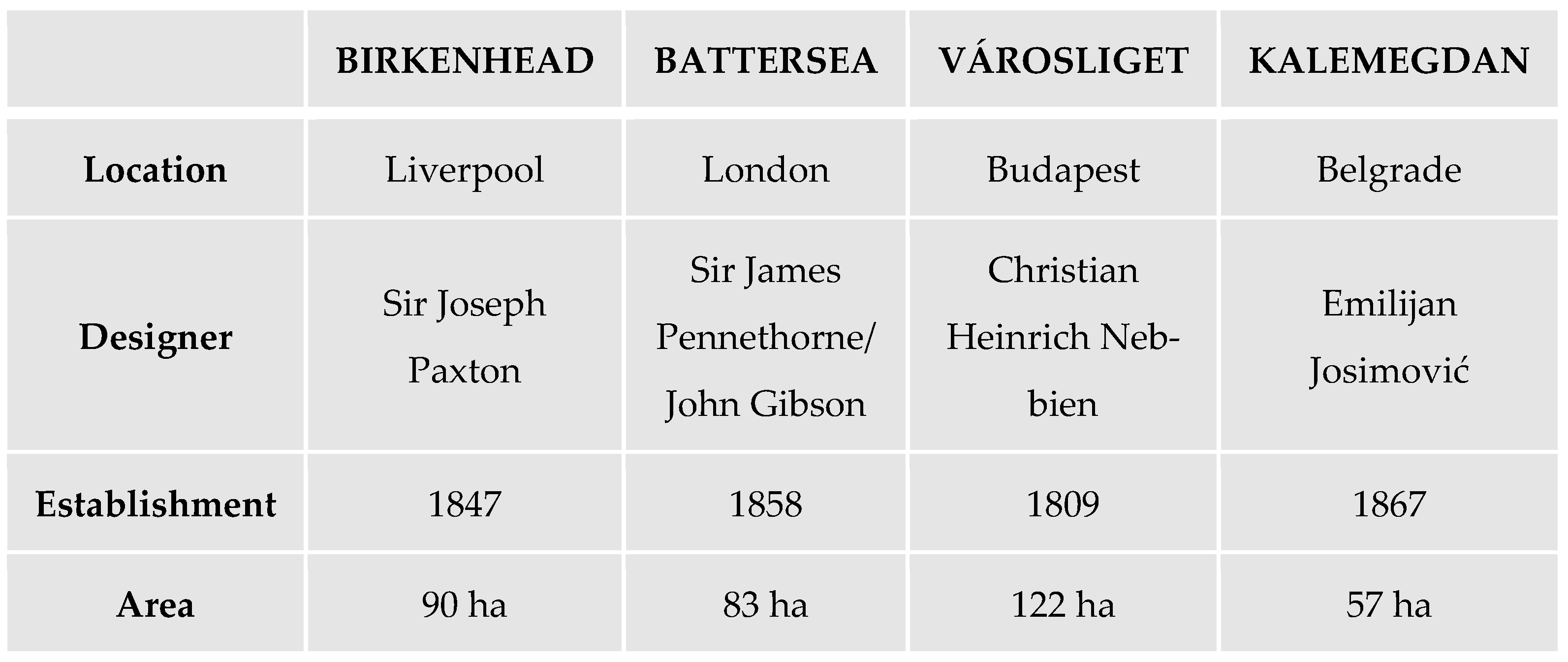

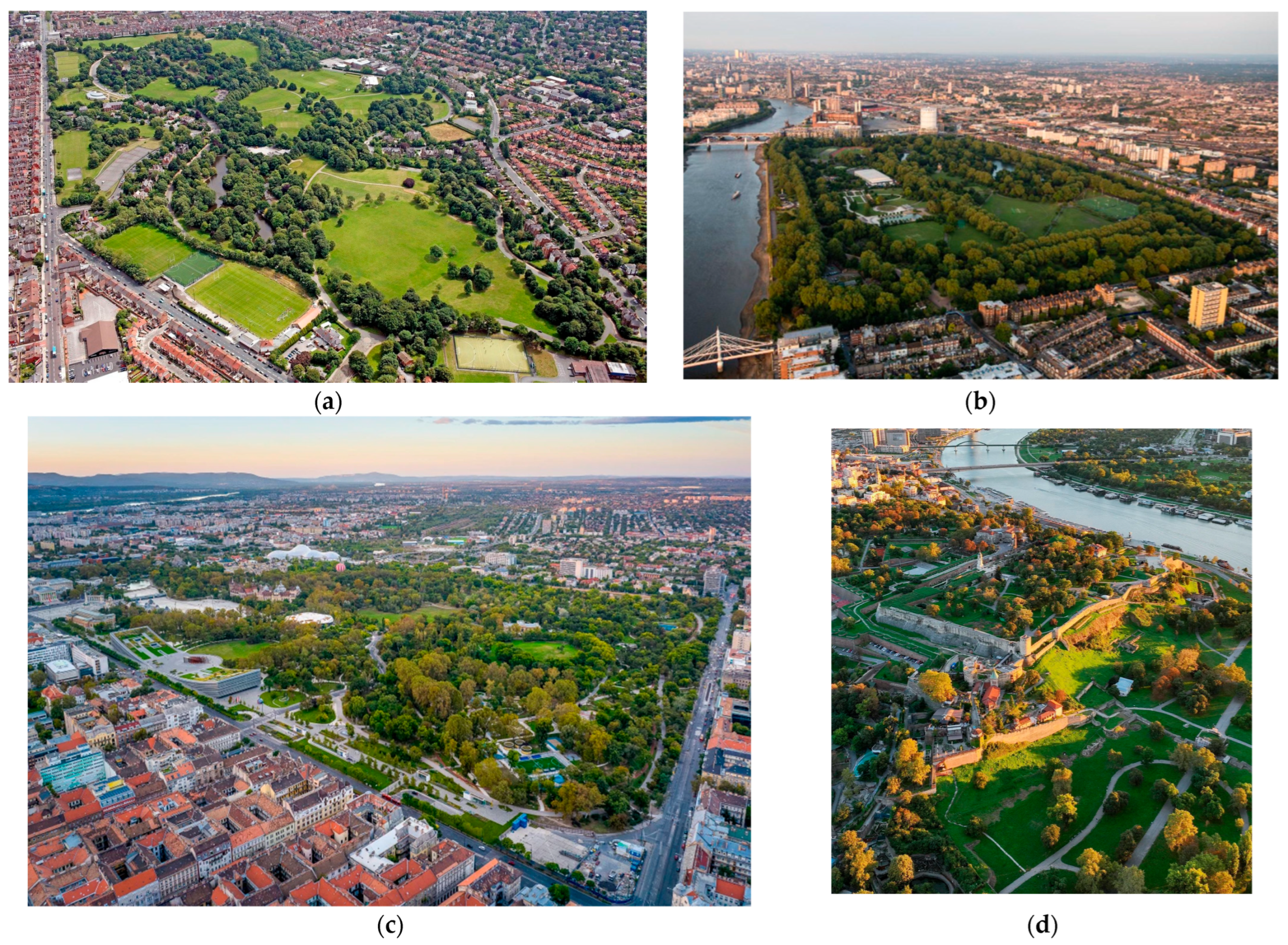

The basic parameters and a general bird’s-eye view of each park are presented in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

4.2. Functional Analysis

The following four designated parks are analyzed both in terms of their individual functions within each park and as part of a larger complex, contributing to broader goals and serving various social and other purposes.

- a.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool, UK

Designed by Joseph Paxton and opened in 1847, Birkenhead Park set a significant precedent in urban landscape architecture. Originally, the park was created to encourage passive recreation, such as walking, sitting, and picnicking, reflecting the 19th-century ideals of public health, social order, and moral improvement (

Figure 4). Remarkably, Birkenhead Park has remained largely true to its original design, with only minor changes to its layout and function. Its picturesque landscape continues to charm visitors, supported by the careful preservation of historic buildings and architectural features. By the late 19th century, the park’s role expanded to include active recreational spaces such as cricket grounds, football pitches, and an archery lawn, evolving into a multifunctional public landscape (

Figure 5). This flexibility was especially evident during World War II, when parts of the park were repurposed as allotments to support food production [

29,

30,

31].

- b.

Battersea Park, London, UK

Established in 1858 along the banks of the River Thames, Battersea Park reflected a Victorian vision of civic improvement, public health and social reform. The site, formerly a marshy common associated with stagnant water, taverns and gambling, was transformed into a green and healthy environment as part of a wider public park movement aimed at improving urban living conditions [

32]. Its global function was to provide rest, fresh air and moral uplift to the working classes, offering relief from the overcrowded and polluted city environment [

29]. The original design by landscape architect James Pennethorne followed the Victorian park typology and featured winding paths, carriage rides, ornamental gardens, and an artificial lake. In its early years, Battersea Park was primarily a space for passive leisure and ornamental recreation, such as boating, strolling and attending concerts at the central bandstand (

Figure 6). Over time, the park adapted to changing urban needs. After its transfer to the Metropolitan Board of Works, new functions were introduced, including tennis courts, bowling greens and athletics facilities, reflecting growing interest in organized sport [

33]. During both World Wars, the park served military and civil purposes. A major functional shift occurred during the 1951 Festival of Britain, when the Pleasure Gardens brought in fairgrounds, exhibitions and cafés, expanding the park’s role in leisure and entertainment. Today, Battersea Park is a multifunctional public space with significant ecological value and a wide range of activities including sports, art, tourism and cultural events (

Figure 7).

- c.

Városliget Park, Budapest, HUN

The designer of Városliget Park was Heinrich Nebbien, a renowned landscape architect who won the commission in a competition in 1813. The park’s construction works began in 1817 and were personally supervised by the designer [

35]. Városliget is a very popular park thanks to the variety of activities and attractions it offers. It serves many functions related to the social life of city residents and tourists, including walking, leisure, education, gastronomy, and active recreation. The park was originally designed following the principles of landscape style parks, focusing mainly on walking and leisure [

34] (

Figure 8). Over time it developed into a multifunctional space. Moreover, the City Park was supposed to provide Budapest with a large amount of green space that helps the city adapt to and even mitigate climate change. The main function of the park was to purify the air, provide a valuable area for water infiltration and retention, which is rare in the city center, and reduce the urban heat island effect. The recreational functions of the park have changed over time, reflecting the development of public spaces in Europe as well as shifting trends and the needs of residents. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the park offered a much wider range of recreational opportunities (

Figure 9) compared to its original design. New infrastructure and architectural features were built, along with temporary structures for the Millennium Exhibition. As a result, the park began to provide new attractions, including an ice rink in winter and a boating pond in summer, a circus, restaurants and cafés, a zoo and a museum. In later years, these elements were further developed, and new ones were created, such as permanent buildings replacing the temporary exhibition structures, new museums and a botanical garden [

35].

- d.

Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, SRB

With the gradual loss of Kalemegdan’s military relevance in the second half of the 19th century, Emilijan Josimović, Belgrade’s first urban planner, introduced a visionary urban concept in his 1867 regulatory plan, proposing the transformation of the former military base to a publicly accessible green area. Within this framework, Kalemegdan was conceived as a vital component of a “green belt” surrounding the historical city core, designed to promote public health and urban esthetics [

36]. Kalemegdan’s transformation began with the initial development of the Upper Kalemegdan in the late 19th century. Over time, the park expanded to include Lower Kalemegdan, the Inner Fortress, and Lower Town, gradually shaping Kalemegdan we know today. This evolution reflected not only spatial growth but also a shift in function. Park was initially developed as a landscape style park, primarily intended for walking, relaxation and passive leisure, in line with the design trends of the time (

Figure 10). However, over the years, its role has evolved to meet the increasing demands of modern urban life, and the park gradually expanded its functions to include spaces for sports, tourism, cultural events and ecological benefits. The ecological role of Kalemegdan is particularly important, as it serves as the primary green space for both the city center and the surrounding residential areas. Kalemegdan’s elevated position and open exposure to prevailing winds help reduce air pollution, while its rich vegetation supports temperature regulation and ecological balance [

37]. It functions as both a historic symbol and a modern facility, home to the Military Museum, Belgrade Zoo, observatory, numerous monuments, and cultural institutions (

Figure 11).

4.3. Compositional Analysis

- a.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool, UK

Birkenhead Park’s layout, architectural language and landscape design reflect the English Picturesque design. This landscape technique aimed to evoke natural beauty while carefully guiding user movement and visual experience [

42]. The park exemplifies this tradition through its deliberate modification of topography, views and planting, all crafted to promote an immersive visual and spatial experience. The park composition is characterized by a flowing, undulating terrain with strategically placed artificial mounds and valleys, particularly around the lakes, which were excavated to create sculptural landforms [

30]. Key design elements of the park’s layout include the following:

- I.

Curvilinear carriage drives and footpaths, avoiding axial geometry.

- II.

Short-range views and carefully framed vistas.

- III.

Higher-intensity planting around water features to enhance visual drama.

- IV.

Tree screening along the edges of the park, reinforcing a “green oasis” effect and concealing nearby urban fabric.

The intention of this design was to simulate the esthetic of the English countryside while providing the urban public a space for passive recreation. Paxton’s vision extended beyond planting and path systems to a collection of architectural features placed as visual anchors and focal points. The most iconic structures include The Grand Entrance, Swiss Bridge and Boat House, Park Lodges, etc. The pastoral ideal was expressed through extensive lawns, meandering lakes, layered vegetation and varied tree species. Birkenhead Park is framed by a residential belt of villas and terraces, many of which were designed to harmonize with the park’s appearance. Like many historic parks, Birkenhead Park has had to adapt to the pressures of globalization, rising urban populations, and evolving public expectations. No longer serving solely as a place for passive recreation, it has transformed into a multifunctional space.

- b.

Battersea Park, London, UK

Similar to Birkenhead Park, Battersea Park reflects the English picturesque style through its deliberate interplay of scenic planting, curved paths, and focal points. Irregularly shaped water bodies, especially the boating lake, provide scenic contrast to the open lawns and heavily planted tree clusters. The use of exotic plantations across different zones of the park demonstrates Victorian horticultural ambitions, while functionally separated areas for sport, leisure, and strolling reflect the period’s approach to organizing recreation in a structured yet naturalistic setting. The park’s architectural elements are distributed across the landscape as visual points, many of which have survived in altered or restored forms. At its entrances, original gate lodges once anchored each access point: Sun Gate Lodge, West Lodge, Rosary Lodge and Chelsea Lodge, although the last one was destroyed by fire. These structures reflect the formal thresholds of Victorian parks. One of the park’s earliest structures, the rifle yard, located near the northwest gate, dates back to the park’s initial construction and currently houses the park’s offices. In the park’s center lies the Victorian bandstand, situated at a key junction of paths. This placement was intentional: in the nineteenth century, the bandstand served as both a programmatic centerpiece and a social gathering point, reflecting the Victorian ideal of cultural enrichment through public leisure. A notable example of Victorian engineering within the park is the Grade II listed Pump House, built in 1861 to supply water to the lake and to the adjacent cascades, a dramatic artificial rock formation in the northern section of the boating lake [

43]. Fundamentally, key design elements of Battersea Park’s include the following:

- I.

Curving path network and circular nodes.

- II.

Irregularly shaped lake and water features, including the boating lake and cascades.

- III.

Exotic plantings.

- IV.

Densely planted tree clusters.

- V.

Functionally separated areas designated for walking, sports, events and rest.

- VI.

Architectural features such as lodges, the bandstand, Pump House and bridges.

While deeply rooted in Victorian values, Battersea Park has also embraced twentieth-century layers of meaning, as several important sculptures by twentieth-century artists are placed across the park. One of the most significant additions is the Peace Pagoda, a Buddhist stupa built in 1985, representing a cross-cultural call for global peace. Today, the park has adapted to the modern expectations of urban parks and serves as multifunctional spaces, offering a children’s zoo, a sports arena, all-weather pitches, a boating lake, and various event venues.

- c.

Városliget Park, Budapest, HUN

The City Park in Budapest, originally known as Stadtwäldchen in German, was the world’s first public park established by a city on its own territory and from its own resources for the free use of its citizens, with the designer selected through a public competition announced in 1813. The winning entry, designed by Heinrich Nebbien, is significant not only because it was the first of its kind in the world, but also because the City Park, as designed, is one of the most beautiful public gardens of its time [

44].

According to Nebbien, the essence and foundation of a landscape garden is “the free, pure form of nature, born from the most intimate connection between economic and esthetic aspirations. (…) These two aspirations [in the case of the garden] are so closely intertwined that their results come about simultaneously and together, each arising from the other everywhere, and consequently manifesting themselves as the Beautiful as Useful and the Useful as Beautiful.” [

35]. The design of the Pest People’s Garden was also born out of the professional and creative conviction that beauty and usefulness reinforce each other.

In terms of spatial composition, Nebbien considered classical garden design and picturesque gardens to be the defining sources of landscape gardening, viewing the subsequent sentimentalism as a mistake. The landscape architecture plan for the City Park, the “Ungarns Folks-Garten”, is therefore characterized by classical principles: the long, transparent, freely formed spatial structure, the proportions, floor plans, and connections of the individual spaces, the design of the walls, the paths running along the edges, offering a comprehensive perspective of the whole, the enclosed patches of forest, the bouquet-like groups of trees formed from a few species, dividing the spaces—all these are the characteristic of the romantic transcription of the classicist picturesque garden.

Nebbien describes the separate spaces as painted images, suggesting that he intends to create paintings. The richness of design is represented by the following:

- I.

Various building features: buildings, the classicist gate, the restaurant, the amphitheater, the dance hall, the manor house.

- II.

Asymmetrical, freely formed layout, loose spatial structure, tucked away between the walls of the space and the plantings, avoiding any exposed position.

- III.

A regular circular central element, the Körönd, designed as a walking and carriage area.

- IV.

Water mirror with a space-organizing effect.

- V.

In the axis of the City Park Avenue, behind the entrance gate to the park, there is a triple road system built around a circular lawn. Pedestrians strolled along the inner lane, carriages along the middle lane, and horsemen along the outer lane, each on a different surface, framed by a tree-lined avenue on the outer edge. [

45].

Much of the original spatial structure and functions have been preserved to this day, in a more or less modified form.

- d.

Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, SRB

Kalemegdan Park was initially designed in the landscape style, in line with the prevailing trends of its time, but over the years it has developed into a space characterized by a mixture of styles shaped by historical layers, urban growth and changing public needs. In the beginning, park consisted solely of Upper Kalemegdan, but today park includes Lower Kalemegdan, the Inner Fortress, and the Lower Town. In its early development, the park’s main design elements focused on the organization of pedestrian paths and the planting of trees, reflecting the landscape style trends of the time. These early interventions emphasized circulation and visual connectivity, with pathways leading visitors toward monuments, fountains, and viewpoints overlooking the Danube and Sava rivers. Resting areas were strategically positioned along the promenades to encourage leisure and enhance the experience of movement through the park [

36,

46]. In its earliest form, Kalemegdan Park featured only landscape elements such as pedestrian paths, tree plantings, monuments, and fountains. However, as the park expanded and evolved into a multifunctional urban space, particularly with the development of Lower Kalemegdan, its character began to shift. New functions were introduced to accommodate broader public interests, including recreation, tourism and family activities. Lower Kalemegdan underwent the most visible transformation, especially with the addition of the Belgrade Zoo and an amusement park. As the park expanded, the integration of the fortress’s historical walls, gates, towers and bridges became central to its identity. These features are preserved not only as cultural and historical landmarks but are also incorporated into the spatial logic of the park itself. However, over time, the following have consistently emerged as key elements of the design:

- I.

Curved and organic paths in Upper Kalemegdan, designed in the landscape garden style of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- II.

Main axial routes that connect major features.

- III.

Connections and stairways across steep terrain and level changes.

- IV.

Terraces, cliffs and elevated viewpoints.

- V.

Historical walls, gates, towers and bridges fully integrated into the park’s spatial logic.

- VI.

Tree-lined promenades.

4.4. Spatial Structure and Tree Canopy Coverage Analysis

- a.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool, UK

Originally, the park featured lawns, gently curving paths, ornamental lakes, and framed vistas, complemented by strategic tree planting to enhance sightlines and provide spatial definition without overwhelming the landscape. In the early stage, tree canopy coverage was relatively sparse, in line with Paxton’s design intent. The openness allowed for public gatherings, promenading, and uninterrupted visual connections across the park’s terrain. Trees were carefully placed to frame views of key architectural elements, such as the Grand Entrance, Swiss Bridge and Boathouse, without dominating the visual or physical structure of the landscape.

By 2025, the spatial experience of Birkenhead Park has evolved significantly through the natural maturation of its vegetation. The tree canopy has become denser and more widespread; areas once defined by openness are now partially enclosed by mature tree growth. This increased canopy coverage has restructured how space is perceived. However, it is not only vegetation that has reshaped the spatial structure. Over time, the function and usage of the park have diversified, leading to the introduction of modern recreational infrastructure. Spaces have been changed to accommodate contemporary needs, including playgrounds, sports courts, fitness areas, cafés, visitor facilities and event spaces. This evolution in use has introduced a multi-zoned spatial pattern, where traditional scenic and passive-use areas now coexist with dynamic, activity-oriented zones.

- b.

Battersea Park, London, UK

The spatial structure of Battersea Park reflects a balance between formal design and organic flow, shaped by its Victorian origins and evolving urban context. The park was laid out with a clear internal hierarchy: wide tree-lined avenues and axial paths define major movement routes, while smaller curved secondary paths create a contrasting sense of intimacy and discovery.

This layered arrangement allows for seamless transitions between separated areas, open lawns, secluded woodland areas, and riverfront promenades. The design used the park’s flat terrain to establish long sightlines, often ending in architectural or horticultural features. Today, these traditional spatial layers are joined by clearly zoned areas for modern facilities, including children’s playgrounds, cafés, sports courts and event spaces, reflecting contemporary urban needs.

Tree canopy coverage has played a defining role in shaping both the esthetic and ecological qualities of this spatial experience. In its original design, tree planting was formal and strategic: avenues were defined by rows of trees, and ornamental species were concentrated in designated gardens. Open lawns and recreation grounds were intentionally left unshaded, preserving visual openness and supporting active use. Over time, however, the tree canopy has matured and expanded significantly, resulting in broader shaded areas. This growth has softened the park’s formal geometry, especially along meandering paths and near the water bodies, creating a different character.

- c.

Városliget park, Budapest, HUN

Nowadays Városliget’s spatial structure is characterized by a strong central compositional axis, extending from Heroes’ Square into the heart of the park. This axis acts as a formal spine, anchoring the park to the urban grid and establishing a clear directional logic. The rest of the park unfolds with a contrasting informal structure, a mix of curved paths, open lawns, and wooded areas that surround the central alignment. Initially, the park’s vegetation was relatively sparse, characterized by simple (single-species) groupings of trees and open lawn areas. Early maps reveal these elements as the core structural components, with limited diversity in plant forms and a focus on open green spaces. The tree canopy coverage has expanded and matured over time, changing the original intent of the design. The evolving spatial structure and canopy coverage of Városliget are the product of changing social values and environmental needs, reflecting a broader European trend towards making multifunctional spaces.

- d.

Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, SRB

Developed around the historical Belgrade Fortress, Kalemegdan Park has undergone substantial transformation since its formal landscaping in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Kalemegdan’s spatial structure is defined by its multi-level topography and fortified setting, which organize the park into a clearly articulated, three-level system. These levels are spatially and visually distinct, creating a hierarchical structure that guides movement and use. The topography plays a critical role, offering elevated viewpoints and structuring circulation along sloped paths, terraces, and stairways. The combination of its evolving landscape design, military legacy, strategic position, and varied elevation makes Kalemegdan a structurally complex park, where spatial orientation and terrain transitions are integral to the overall experience. As the oldest public park in Belgrade, Kalemegdan has preserved a notable portion of its original structure and vegetation. Many trees date back to the period between the two World Wars. While their age adds historic value, some now require replacement, not only because of their reduced visual appeal but also due to their diminished ecological function [

37].

Summing up, the primary changes in the park’s spatial structure can be observed through the transformation of its roads and pathways, water features, and tree canopy, as illustrated in

Figure 12.

4.5. Visual Connection Analysis

- a.

Birkenhead Park, UK

Birkenhead Park features a carefully made arrangement of views, open spaces and architectural landmarks. Key buildings, such as the park’s lodge, the main entrance and the pavilion, are carefully situated to frame vistas that guide the visitor’s journey through the open space. Panoramic views across the lake and toward the pavilion remain crucial visual assets. Over time, as trees matured and the canopy expanded, some of these views became partially blocked or less visible. The park’s management plan acknowledges this change and emphasizes the need to balance maintaining historic sightlines with supporting natural growth.

- b.

Battersea Park, UK

The River Thames serves as one of the most significant visual connections within Battersea Park, with numerous landscaped areas, elevated viewpoints and pathways oriented to frame the river’s presence. The Boating Lake pathways were carefully designed to guide visitors along scenic routes, allowing them to experience a sequence of vistas where the water was beautifully framed by green lawns, trees and plantings that enhanced the picturesque quality of the landscape. The Grand Vista and the fountain lake with statues serve as focal points within the park, thoughtfully positioned to draw attention. The Battersea Power Station, a listed building located near the park, dominates the eastern skyline and creates a visual landmark when viewed from the bowling green, offering a strong visual connection between the park and its urban surroundings. While many primary axes remain clearly defined, the denser and more expansive tree cover has softened some of the original long-distance views, creating a more enclosed and intimate atmosphere in parts of the park (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14).

- c.

Városliget Park, HUN

When the Park first opened, its spatial composition was defined by a single primary visual axis that stretched across the park. The relatively sparse tree coverage at that time allowed for long, uninterrupted sightlines connecting key landmarks. As the park evolved over the following century, the introduction of new building elements created multiple observation points, enabling complex, multi-layered views across different planes within the park. Today, the park’s dense and mature vegetation has significantly altered these sightlines. While the original long-distance views have largely been obscured, a notable exception remains—the bridge overlooking the pond still offers one of the few remaining distant vistas. Elsewhere, views are predominantly restricted, giving visitors a more enclosed and intimate spatial experience. This transition from expansive to more contained visual corridors reflects both the natural growth of the park’s canopy and a shift in landscape design priorities (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

- d.

Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, SRB

The axes in Kalemegdan can be divided into two types: those that lead to monuments or other important structures within the park and those that serve as panoramic viewpoints of Belgrade. Given the park’s varied terrain and elevated position, these sightlines are a defining characteristic and a key asset of the park, offering visitors astonishing views of the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers. Some axes, such as the one leading to the Monument of Gratitude to France, have remained largely unchanged over time, preserving their original narrative. However, some sightlines have been altered or partially obscured by the natural growth and maturation of the tree canopy. While the overall framework of the axes remains intact, the evolving vegetation has transformed the way these views are experienced (

Figure 17).

4.6. Road and Water System Analysis

- a.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool, UK

The water features, including lakes, streams and ornamental bridges, were strategically incorporated to add esthetic value, regulate water flow, and provide habitats for wildlife. These elements also contributed to the park’s environmental sustainability and public health by controlling water flow, enhancing air quality, and providing wildlife habitats. Unlike parks situated along major rivers, Birkenhead Park’s water system operates independently of large external waterways. It relies on local drainage and water retention strategies to maintain its lakes and streams.

Birkenhead Park’s road system combines broad, formal avenues with winding, naturalistic paths to guide visitors through varied landscapes and key landmarks. The main routes provide clear sightlines and easy navigation, while smaller paths encourage exploration. Designed for pedestrians and carriages, the network reflects Victorian ideals of accessibility and social inclusion.

- b.

Battersea Park, London, UK

Battersea Park’s waterworks are a distinctive feature of its 19th-century landscape design; the park’s prominent water feature is an irregularly shaped lake, a characteristic element typical of Victorian landscape style parks. Grade II listed Pump House was the central point for park’s water management. Originally built in a fine classical style using stock brick with rusticated quoins, the Pump House housed a coal-fired steam engine designed to supply water to the boating lake and the ornamental cascades [

43]. These cascades, situated north of the boating lake, are an artificial rock structure made to mimic natural rock formations. The cascades and the lake were linked through a water system fed by the Pump House, which drew water from a reservoir to maintain the flow. After falling into disrepair following the war, the Pump House was restored between 1988 and 1992 and repurposed as an art gallery, preserving its historic significance. The waterworks contribute not only to the park’s visual appeal but also to the micro-climate that supports the renowned Sub-Tropical Garden, enabling the cultivation of exotic plants like palms, tree ferns and bananas.

The park is divided into four quarters by two main axes: an east–west avenue and a straight north–south path. These intersect at a central circular space, creating a focal point within the park. The north–south axis extends to terminate in semi-circular paths and spaces, providing graceful transitions within the landscape. The entrances to the park are strategically positioned at each of its four corners, with an additional main entrance located at the end of the north–south axis, ensuring easy access and flow of visitors. The road system is characterized by wavy lines.

- c.

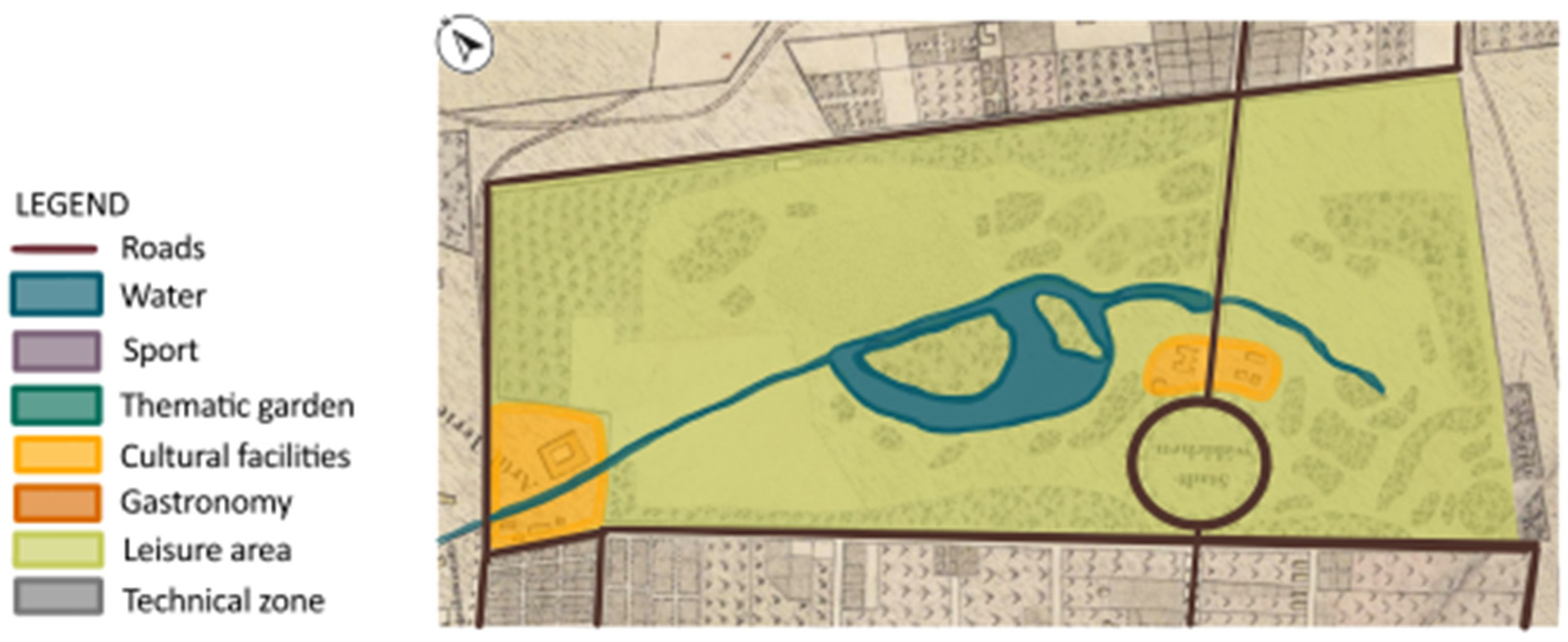

Városliget Park, Budapest, HUN

Water features have played a key role in shaping Városliget since its creation in the early 19th century. Originally, the park included a large pond with two islands connected by a canal system that added both beauty and function to the landscape. This water system was designed not only for esthetic purposes but also to support recreational activities. In summer, the pond was used for boating, while in winter, when it froze over, it became a popular ice-skating area. Over time, some parts of the water system, such as the canal, were removed, but the pond itself largely remained. Additional water elements were added throughout the park, including fountains and smaller ponds, enhancing the park’s appeal and providing cooling effects during hot weather. The water bodies also help support local wildlife and contribute to the park’s ecosystem.

Over the course of two centuries, the road system in Városliget has undergone significant changes in both its development and character. Initially, the road network was poorly developed and exhibited a predominantly geometric and formal layout. However, by the early twentieth century, the park experienced substantial growth, marked by a more intricate system of pedestrian paths that connected the increasingly complex park structures and architecture.

- d.

Kalemegdan Park, Belgrade, SRB

In the 19th century, Belgrade’s waterscape, including areas like Kalemegdan, played a key role in the city’s urban development and public health. The first modern water supply system was built on the foundations of earlier Roman, Ottoman and Austrian waterworks, channeling water to the fortress and surrounding areas [

46]. Due to its topography and the presence of tunnels beneath the park, Kalemegdan does not feature many water installations. It mainly contains drainage channels, some fountains, and small water features. Historically, the fortress relied on cisterns and wells for its water supply. The park’s steep slope promotes natural drainage, reducing water stagnation and supporting healthy soil conditions for the vegetation [

37].

The road and path network in Kalemegdan Park reflects its military origins and later adaptation into a public space. The current circulation structure is defined by a hierarchy of paths and promenades, designed to balance accessibility, strategic views, and recreational use. Axial and radial pathways were laid out during the park’s transformation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [

36]. These formal promenades offer direct visual access to key monuments, viewpoints, and the fortress. The Upper Kalemegdan promenade serves as the main circulation route, connecting the entrance near Knez Mihailova Street to the Belgrade Fortress plateau. Secondary, curvilinear paths in the lower areas and slopes follow the natural topography, offering informal, leisurely routes toward the Sava and Danube rivers.

4.7. Vegetation

Several authors describe contemporary trends in plant use in detail in comprehensive works [

29,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Comparing these with the field surveys conducted related to the present study and other available surveys of the current situation of the parks reveal similarities and differences in the historical and current plant use at the sites studied.

- a.

Birkenhead Park, Liverpool, UK

The planting scheme included a wide variety of native and exotic tree species, carefully positioned to demonstrate botanical richness and serve an educational purpose. Artificial mounds created from lake excavations shaped the undulating terrain of the park and helped it to resist the prevailing winds, while also supporting plant growth and visual interest [

30].

- b.

Battersea Park, London, UK

The park’s layout features broad avenues lined with trees as well as more informal woodland areas and flower beds. The park’s canopy coverage from the construction reveals a significant transformation, including over 4000 trees, many of which follow the original Victorian landscaping plan.

- c.

Városliget Park, Budapest, HUN

Many trees were planted during the park’s initial development in the early nineteenth century and have matured into a dense canopy that defines the park’s character. Currently, 7105 tree specimens compose the canopy of Városliget. There are 297 trees older than 130 years, including 53 trees older than 180 years [

56].

- d.

KalemegdanPark, Belgrade, SRB

The park’s green system was planned during its transformation from a military site into a public space in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with additional planting phases occurring between the two World Wars and after World War II [

37]. A large number of mature trees can be considered major park features, many of which have surpassed a century in age. The tree composition includes both native and introduced ornamental species, reflecting the horticultural trends of the 19th century in urban park design.

In summary, it can be observed that the current composition of tree species in the parks (

Figure 18) has developed through similar processes. In each park, native tree species such as English oak (

Quercus robur), European beech (

Fagus sylvatica), poplar (

Populus sp.), silver birch (

Betula pendula) and silver lime (

Tilia tomentosa) are present. A significant number of ornamental species typical of the landscape garden period, such as London plane (

Platanus x hispanica), European ash (

Fraxinus excelsior), bald cypress (

Taxodium distichum) and Japanese pagoda tree (

Styphnolobium japonicum), are also represented. In addition, numerous evergreen taxa can be found, including black pine (

Pinus nigra), Scots pine (

Pinus sylvestris), Himalayan (

Cedrus deodara) and Atlas cedar. (

Cedrus atlantica).

5. Conclusions

The protection and renewal of historic urban parks is a professional task that poses ongoing challenges. Due to their historical significance, their maintenance and renewal must be based on traditional values.

This study shows that historical urban public parks established in the 19th century still play an important recreational, urban structural and ecological role. They form the basic elements of urban green infrastructure, while also providing opportunities for active recreation for the population and serving as venues for social and cultural life. Their current central location in the urban structure is largely due to the time of their creation, as since the 19th century, cities have grown around these parks, further emphasizing their importance in the life of the settlements.

This analysis intended to highlight and to evaluate the relevant basic design elements of the parks which define their historical characteristics and have been preserved to this day.

From a functional point of view, all of the parks have been dynamically enriched since their creation: in addition to their traditional functions (to provide rest, fresh air, moral uplift to the working classes, the possibility for the aristocracy to be represented, relief from the overcrowded and polluted urban environment, etc.), numerous new functions (sports, arts, play, cultural events, catering) have also appeared over the decades. The new functions have mostly been well integrated with the old ones in the parks. The most relevant developments in this direction can be observed in the cases of Kalemegdan Park (Belgrade) and Városliget Park (Budapest). In the first case, the extension of the park area with the integration of the former fortress area contributed essentially to the enrichment of functions; in the case of Városliget, the partial transformation of the park into a cultural district of the Hungarian capital had a significant influence toward the functional development.

Functional development has also partly influenced structural changes in the parks, affecting their main compositional elements, such as spatial structure and visual connections. Nevertheless, it can be said that in all four parks, the structural design corresponding to the original concept is still recognizable today in all four parks. The original composition has been preserved almost entirely in the case of Birkenhead and Battersea parks. Due to the urban developments from the end 19th century, the main entrance of Városliget Park in Budapest has been moved compared to where it was initially. Despite this transformation, the original structure has been mainly preserved; only the main flows and some functions have been changed. Kalemegdan Park presents—through its already mentioned extension—the biggest changes from compositional point of view as well, still preserving some of its original compositional aspects.

The transformation of visual connections can be interpreted in close connection with the development of plant material. Over the centuries, as a result of aging, spreading and expanding plant populations, all four sites studied have experienced significantly higher canopy cover (15–25%) than originally planned. The leveling of the plant population and the strengthening of the shrub layer have resulted in a stronger separation of individual functions and a further reduction in visual connections.

Although these parks are located in different regions of Europe, there is a high degree of overlap in the main tree species planted. Certain tree species—such as linden (Tilia cordata), oak (Quercus robur), plane tree (Platanus x hybrida), birch (Betula pendula), horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum), ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and even certain coniferous species (Pinus strobus)—have been present in large numbers in almost all locations in the past and now, suggesting that these species have defined the image and atmosphere of parks for centuries.

The results prove that, in light of increasingly intense urbanization processes, new environmental challenges (climate change, loss of biodiversity) and the demands for a healthy and livable urban environment, the fundamental characteristics of historic public parks can still be preserved as far as possible, as they are imprints of an era, an artist, and a social message, and their cultural and historical significance is invaluable.