Abstract

Pastoralist sedentarization has accelerated globally since the late 20th century, driven by climate change, government policies, and economic transitions. In Inner Mongolia, China, this process advanced under 1950s socialist initiatives and the 1980s Grassland Household Contract Policy (GHCP), which allocated land use rights to individual households. This study examines the 1960–2020 transition from seasonal nomadism to settled pastoralism in a Gacha, emphasizing changes in grazing strategies and water access. Migration distances declined from about 55 km in the 1960s to 4 km in the 1980s, with sedentarization becoming permanent after the GHCP. Grazing practices shifted toward fixed facilities and supplementary feed, while water use moved to deep wells and storage tanks, increasing both costs and groundwater risks. These transformations modestly improved productivity but heightened social vulnerability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Sedentarization of Pastoralists Worldwide

Over 40% of the Earth’s land surface is classified as drylands []. These areas are unsuitable for agriculture, making pastoralism the main source of livelihood. Pastoralism supports stable production with minimal environmental impact under fragile ecological conditions [,]. Since the late 20th century, however, the sedentarization of pastoralists has accelerated globally [] (p. 75). Sedentarization refers to the transition from a settled life, or from low to high residential stability [] (p. 95). It is not necessarily an irreversible process [] (p. 6). Multiple factors drive sedentarization, including climate change, state policies, and economic shifts, often interacting in complex ways []. These dynamics vary greatly across countries and regions.

In East Africa, sedentarization has been driven by agricultural expansion, resource development, recurring droughts, and political factors. In Kenya, this process is particularly associated with population pressure, diminished access to natural resources, and conflict [,]. In the Sahel, government-led agricultural policies since the late twentieth century have further accelerated the transition to a sedentary lifestyle []. In West Asia, especially in Iran, sedentarization has been influenced by a move toward farming, the loss of grazing lands due to conflicts, and the erosion of pastoral livelihoods caused by poverty. In some cases, wealthier pastoralists have relocated to urban areas [] (p. 11).

In Asia, the sedentarization of pastoralists was frequently driven by state policies and external influences, including interventions by NGOs [] (p. 2). This top-down approach was a hallmark of 20th-century sedentarization processes [] (p. 30), with the Soviet Union and China often cited as prominent examples [,,].

1.2. Sedentarization of Pastoralists in Inner Mongolia

1.2.1. Socioeconomic Context

Compared with African pastoral societies, Inner Mongolia’s pastoral society is relatively politically stable, with no tribal conflicts or civil wars. Pastoral sedentarization, similar to Soviet collectivization in Central Asia, was implemented through state-imposed settlement policies, closely tied to the construction of national identity and state consciousness [,]. Sedentarization was framed as a state-driven “modernization” effort and was part of the broader “socialist construction” [] (p. 666), []. In the Soviet Union, nomadic production and pastoral elites were seen as threats to state ideology and were targeted for exclusion [] (p. 75). In Inner Mongolia, pastoralism was considered a backward production system compared to agriculture, with nomadism seen as underdeveloped [] (p. 182), ref. [] (p. 190), ref. [] (p. 80). Ideologically, nomadism and sedentarism were contrasted as backward versus advanced, with nomadism being viewed as an obstacle to the development of pastoral production [].

The sedentarization policies in Inner Mongolia, aimed at transforming pastoral production, encompassed the construction of fixed livestock shelters, enclosures, wells, breed improvement, commercialization, and the active use of hay and feed [] (p. 124). These policies were institutionalized during the People’s Commune period (1958–1983) and through the Grassland Household Contract Policy (GHCP) introduced after the reform era [] (p. 69). The People’s Commune period, modeled after the Soviet collectivization system, established a socialist framework with collective ownership of production, under which pastoral production and livelihoods were managed collectively [] (p. 27). In 1983, as part of the reform and opening-up policies, the GHCP was introduced, allowing pastoralists to manage pastures and livestock individually under a contract system. This transition from collective to individual management led to the dismantling of the communes and the management of pastures and livestock at the household level. Pasture use certificates were issued with a 30-year contract period [] (p. 69).

Thus, the sedentarization of pastoralists was driven not only by changes in lifestyle and production systems but also by broader goals related to state-building and ideological creation.

1.2.2. Transition Toward Sedentarization

During the People’s Commune period, the sedentarization of pastoralists was largely driven by agricultural policies that promoted the influx of settlers and the expansion of farmland. Cultivation was primarily conducted in areas with abundant water resources, which were also the most valuable pastures for pastoralists. Migrant farmers from other regions were relocated to these areas, where new villages were established [,,,,,,,]. This development is considered a form of sedentarization based on the communal land system of the People’s Commune era [].

A study reconstructing long-term seasonal migration patterns found that in the 1960s, pastoralists practiced a “summer–winter migration pattern” involving about 60 km of movement. In the 1970s, the construction of permanent facilities under the People’s Commune system led to a “fixed spring camp pattern,” reducing migration to around 30 km [,] (p. 77). This marked the beginning of sedentarization, which was further accelerated by the 1977 dzud, when rapid shelter construction and the use of hay and feed for overwintering became widespread [,] (p. 267). Dzud is a Mongolian term for a severe winter disaster caused by extreme cold and snow, often following a summer drought, with the two frequently occurring in sequence.

A key factor in the sedentarization of pastoralists was the introduction of the GHCP which allocated pasture use rights to individual households through long-term contracts, effectively establishing a system of individualized management rather than private ownership [] (p. 36). Following the dismantling of the People’s Commune system, collective land ownership ended [] (p. 48). Pastoralists began fencing their allotted land to manage and protect it [], which limited access by others and also restricted their own herds from grazing on neighboring land [] (p. 31). As a result, traditional seasonal grazing practices and mobility were no longer feasible, leading to widespread sedentarization [] (p. 8). Additionally, the expansion of infrastructure and changes in land use and tenure systems contributed to the erosion of customary practices related to pastoral strategies and water access [] (p. 10).

1.3. Re-Evaluation of Nomadism

The privatization of pastures around the world, and particularly in China, is theoretically justified by Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons” [] (p. 722), ref. [] (p. 353), ref. [] (p. 105). According to Hardin’s theory, pastoralists, driven by the goal of maximizing their profits, increase the number of their livestock without regard for the degradation of shared pastures. This results in the “tragedy” of land deterioration []. To prevent this tragedy, regulatory measures through either the privatization or nationalization of pastures are considered necessary. In particular, privatization of land is regarded as the key solution to environmental degradation, as it enables planned and long-term use [] (p. 1244).

However, subsequent research has shown that the “tragedy of the commons” occurs only under specific conditions and cannot be universally applied. Ellis and Swift, along with Westoby and colleagues, introduced the concept of non-equilibrium models in their studies of pastoralism in East Africa, highlighting that traditional equilibrium models fail to account for climatic variability and spatial heterogeneity in arid regions [] (p. 322). They classified natural ecosystems into equilibrium and non-equilibrium models. In arid areas, where rainfall is highly variable and ecosystems are constantly in a state of non-equilibrium, the concept of carrying capacity based on assumptions of equilibrium is difficult to apply. Therefore, they argue that sustainable pasture use requires adaptive management and flexibility based on mobility [,]. In equilibrium models, the idea is that herbivores and vegetation exist in a stable balance, where the amount of vegetation is mainly controlled by how much the animals graze [] (p. 357). However, in reality, grazing intensity fluctuates according to rainfall, making it inappropriate to assume a fixed environmental carrying capacity. Accumulated research has shown that Hardin’s concept of the “tragedy of the commons” was framed within the equilibrium model, prompting reconsideration of its general applicability and scope [,,,]. Pastoral production, under the fragile grassland ecosystems, has been shown to maintain high stability while minimizing environmental impact []. Therefore, in arid regions, pastoral systems that are based on seasonal migration are being re-evaluated as potential solutions to contemporary environmental challenges, and sedentarization policies are increasingly being reconsidered [] (p. 30). In Africa as well, many sedentarization projects have failed, leading to increasing recognition of the importance of communal pasture management, mobility-based flexibility, and adaptive pastoral strategies based on herd diversity [,].

Research on the Tibetan Plateau shows four main benefits of communal pasture use with seasonal migration [] (p. 135). Individual fencing is costly, whereas collective management provides greater economic benefits and facilitates livestock monitoring and fair resource access. It also allows flexible responses to climate variability and extreme weather. Overall, these findings suggest that, for environmental protection and sustainable pasture use, communal management with seasonal migration is more effective than sedentarization.

This study aims to clarify the long-term transition from seasonal nomadic pastoralism to settled pastoralism through detailed case studies. It investigates how pastoral strategies and access to water resources—originally developed under nomadic practices—have been restructured during the process of sedentarization and how pastoralists have adapted to these changes. Unlike previous research that focuses on the “outcomes” of sedentarization or presumes it inherently improves resilience, this study highlights the “process” itself, emphasizing changes in seasonal migration patterns, the impact of institutional factors, and the evolving nature of pastoral strategies and water access.

Drawing on equilibrium and non-equilibrium theory, adopts a multidimensional approach that integrates geographical and anthropological perspectives. By combining GIS-based spatial analysis, oral histories—here referring to in-depth life-history accounts from key pastoralist households—and semi-structured interviews, and satellite-derived groundwater data, it establishes an empirical and interdisciplinary framework bridging the natural and social sciences. These findings address a critical gap in the literature on pastoral systems in Asian drylands—particularly regarding water resources—enhancing understanding of pastoralist livelihoods and providing valuable insights for policy and future research.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

This study examines the process of sedentarization among pastoralists in Bayantal Gacha (hereafter Area A), located in Bayan Uul Sum, Sunid Left Banner, Xilingol League, Inner Mongolia. Sunid Left Banner consists of three towns and two sums, with 49 gacha as the lowest administrative units. The term Bayantal is Mongolian for “rich grassland.”

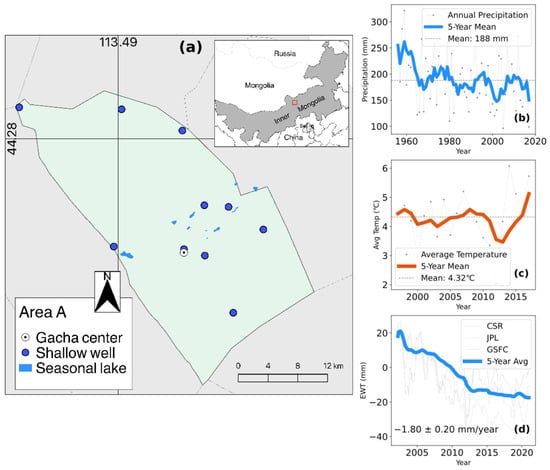

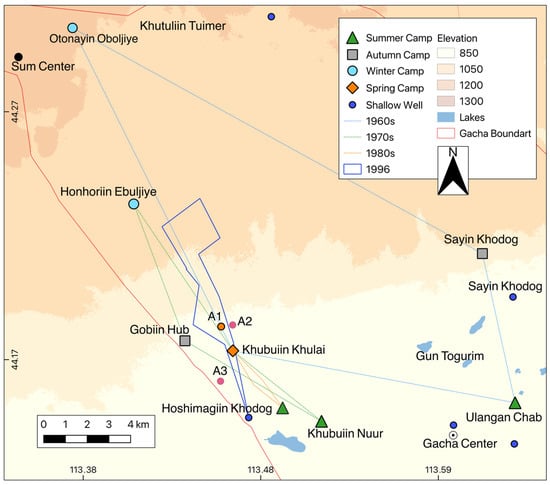

Area A is located approximately 30 km northeast of Mandalt Town, the administrative center of Sunid Left Banner, in central Inner Mongolia (Figure 1a). The dominant landscapes are arid grasslands and desert steppe. The average annual precipitation is 188 mm, while the average annual evaporation reaches ~1600 mm, yielding an aridity index of 0.12; thus, Area A is classified as an arid region []. Since 1956, when meteorological recording began, annual precipitation has steadily declined, with a more pronounced decrease since the 2000s (Figure 1b). Extreme droughts have become more frequent, notably in 2005 (96.3 mm) and 2017 (98.9 mm). Significant shifts in rainfall patterns have also been observed, with the rainy season now starting later, moving from April–May to June–July, shortening the growing season for pasture grasses []. The average annual temperature is 4.32 °C, and under global warming, it has shown a steady increase (Figure 1c).

Water resources in Area A are limited. Pastoralists rely on shallow wells and seasonal lakes, while deep wells, which have increased under government projects since the 2000s, are also utilized. The area contains ten shallow wells, six of which are concentrated in the central region, along with several seasonal lakes (Figure 1a). Shallow wells, generally available for communal use, tap aquifers approximately 2 m below the surface, mainly along dry riverbeds. Deep wells access aquifers several hundred meters underground, reaching 40 wells by 2021. Furthermore, terrestrial water storage (TWS) shows a declining trend, with an average annual decrease in −1.80 ± 0.22 mm, particularly pronounced between 2000 and 2011 (Figure 1d). This trend is consistent with changes in water storage observed in other arid regions, such as Africa [,].

Area A was selected for its representativeness of the arid steppe in central Inner Mongolia, the availability of long-term meteorological records from Mandalt Town, and its limited water resources, which highlight issues of access under sedentarization. Its shift from collectivization to the GHCP further offers longitudinal insights into pastoral adaptation.

Figure 1.

(a) Locations of shallow wells and seasonal lakes in Area A. Shallow wells and seasonal lakes were identified using Google Maps and QGIS 3.16.8-Hannover, with their boundaries mapped as polygons. Data accuracy was verified with local pastoralists; (b) Annual precipitation trend in Area A from 1956 to 2017; (c) Annual average temperature trends in Area A from 1997 to 2017. Area A is about 30 km from Mandalt Town, so precipitation and temperature data were obtained from the Mandalt Meteorological Station; (d) Changes in TWS in Area A from April 2002 to January 2021.based on GRACE Mascon data from CSR (0.25° × 0.25°, RL06 v02), GSFC (0.5° × 0.5°, RL06 v02), and JPL (0.5° × 0.5°, RL06 v03, CRI-filtered). To represent TWS changes, it is recommended to use the average of these three datasets []. Statistical analyses and trend calculations were performed using Python 3.11.4, with visualizations centered on Area A (44.294751° N, 113.461631° E). The figures represent 5-year averages.

Sunit Left Banner covers a total area of 34,251.7 km2 [] (p. 5) and had a population of 33,643 in 2020 [] (p. 108). Animal husbandry is the main livelihood, while agriculture is limited to water-rich areas and practiced on a small scale. Since the 2000s, government-led mining development has expanded rapidly []. Area A spans 70,000 hectares and comprises 128 households with a population of 408, of which 87.7% are Mongols and 12.2% are Han Chinese. The average pasture area per household is 546.9 hectares. Area A holds 25,000 small livestock and 5585 large livestock, totaling 30,585 Sheep Standard Units (SSU), or an average of 239 SSU per household. Agriculture is not practiced in Area A. Data not otherwise referenced are based on the author’s field survey.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

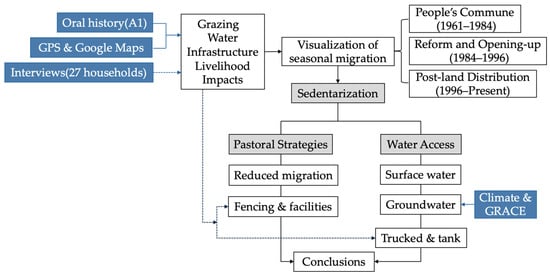

This study aimed to elucidate the sedentarization process of pastoralists. Seasonal campsite locations from 1960 to 2020 were reconstructed for the representative household A1 (Household No. 1) using oral histories and GPS mapping. The analysis focused on changes in pastoral strategies and access to water resources associated with sedentarization. To examine water resource access, climatic data and GRACE-based groundwater data were also incorporated. To complement and validate the case study of Household A1, semi-structured interviews were conducted with an additional 27 households (Figure 2), and secondary sources [] were consulted as needed.

Figure 2.

Analytical framework of the study (solid lines indicate primary flows; dashed lines indicate supplementary or derived relationships).

The 28 households, including Household A1, represented approximately 21.8% of the total population of Area A. Households were selected based on accessibility and stratified by age group. For analytical clarity, each household was assigned a unique number from 1 to 28 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic information of 28 households in Area A.

In reconstructing seasonal campsites, priority was given to spatial distribution and temporal changes rather than specific seasonal migration routes, as Area A is relatively flat and lacks prominent topographical constraints such as valleys or ridges. The location of each campsite was recorded on-site using GPS, and environmental information including campsite names and origins, surrounding vegetation, water sources, and terrain was also collected.

To facilitate interpretation, the sedentarization process was divided into three phases, each reflecting major policy shifts and socio-political contexts: People’s Commune period (1961–1984), Reform and Opening-up period (1984–1996), and Post-land Distribution period (1996–present) (Figure 2).

The structured questionnaire was organized around four key aspects:

- (1)

- Process of Sedentarization: Changes in housing types, the construction history of fixed facilities, and household assessments of sedentarization.

- (2)

- Household Economic: Income and expenditure structures, presence of loans, dependence on hay and fodder, and economic changes resulting from sedentarization.

- (3)

- Water access: Historical changes in water use, current water use patterns, distance to water sources, year of well construction, and detailed records of water purchase and transport practices for representative households.

- (4)

- Pastoral strategies: Changes in and current patterns of pasture use, shifts in livestock composition and their causes, the extent and causes of pasture degradation, and household perceptions and evaluations of environmental policies, including grazing bans, grass-livestock balance policies, and subsidy systems.

Although the questionnaire addressed a wide range of topics related to sedentarization, detailed analyses of household economy and water access are presented in separate publications. Field surveys were conducted in August 2012, August 2014, March and June 2019, and March 2021.

2.2.2. Geographic Data and Visualization

To elucidate the spatial distribution and temporal changes in seasonal campsites, GPS coordinates collected during field surveys were processed in QGIS and mapped onto a topographic base map with a 30 m resolution.

The boundaries of pastoral lands were determined and verified using Google Maps, and the locations of enclosures were confirmed and delineated as polygons in QGIS. Likewise, the positions and areas of shallow wells and seasonal lakes were identified with Google Maps and digitized as polygons. To ensure data reliability, all spatial data were cross-checked with local pastoralists. Furthermore, historical context and naming information for the wells and lakes were systematically documented.

Changes in TWS were assessed using GRACE Mascon datasets produced by CSR, JPL, and GSFC. These datasets comprise regularized monthly gravity field measurements that facilitate the direct estimation of TWS variations, presented as EWH (Figure 1). The study period spans April 2002 to June 2017 for GRACE, and June 2018 to January 2021 for GRACE-FO. Statistical analyses and trend estimations were performed using Python, and for time series visualizations, the center of Area A was designated as the geographic reference point.

2.2.3. Overview of the Informant

The majority of livestock raised by the 28 herding households are sheep, followed by goats. Cattle are raised by 21 households, horses by 13, and camels by 4. The average pasture area per household is 767.33 hectares. Ownership of horses and camels is concentrated in a limited number of households. The average livestock density is 0.86 animals per hectare. Ten households (35.7%) have access to shallow wells, whereas 18 households (64.2%) use deep wells. Seven households (25%) have access to both shallow and deep wells. Additionally, 7 households (25%) do not have wells on their allocated pastureland and therefore fetch and transport water for use (Table 1).

Mr. A1 is a herder from Area A, born in 1945 and currently in his 70s. From the 1980s to the 1990s, he served as deputy leader (gacha) and accountant, making him well-informed about the affairs of Area A. Mr. A1’s current family consists of himself (born 1945), his wife (born 1947), his eldest son (born 1974), his eldest daughter (born 1975) with her spouse and children, and his second son (born 1981) with his spouse and children. Currently, the household includes Mr. A1 and his wife, their eldest son, and the family of the eldest daughter, while the second son’s family resides in Mandalt Town, the administrative center of Sunit Left Banner.

The A1 family is now fully settled. They have built fixed houses within their allocated pastureland and graze their livestock on this land. They do not share their pastureland with other households. The total pasture area allocated to Mr. A1, his wife, eldest son, eldest daughter, and second son is 886.7 hectares. As of 2019, Mr. A1 and his wife owned 230 small livestock (190 sheep and 40 goats) and 20 large livestock (16 cattle and 4 camels). Combined with the livestock owned by the eldest son and eldest daughter, the totals amount to approximately 400 small livestock, 60 cattle, and 10 camels (Table 1). The cattle consist of improved breeds, kept for both milk and meat production.

3. Results

3.1. Seasonal Migration During the People’s Commune Period (1961–1984)

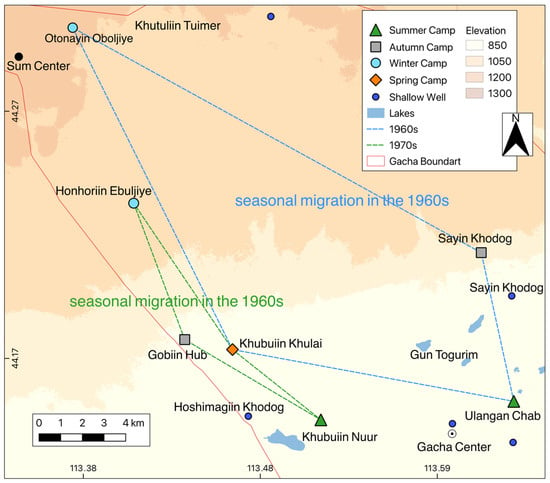

Mr. A1’s memories of pastoral life date back to around 1961, during the People’s Commune period. At that time, the People’s Commune was known as Yihe Barigada, and the production team was called Bag Barigada. The production team corresponds to what is now referred to as a gacha. Figure 3 reconstructs the locations of seasonal camps for each year in the 1960s based on Mr. A1’s recollections. In 1961, Mr. A1 was 16 years old. At that time, his family consisted of five members: his parents, older brother, himself, and younger sister.

Figure 3.

Annual seasonal migration in the 1960s and 1970s (locations were verified with A1 during field visits, and GPS coordinates were recorded for each campsite; data visualization was performed using QGIS).

During the People’s Commune period, Mr. A1’s parents’ household had about 500 sheep. In combination with the livestock of the other households in the hot ail, the total number of sheep amounted to around 1000. The hot ail, a unit commonly translated as “camp group” and regarded as a basic social organizational unit [] (p. 22), was composed of four households, including that of Mr. A1’s parents. In Inner Mongolia, this unit is commonly called a hot. Within Mr. A1’s parents hot ail, there was also a household responsible for managing about 80 heads of cattle. Small livestock within the hot ail were collectively pooled and grazed in rotation by each household. This collective system was implemented to efficiently reduce labor. Moreover, although only a limited number of privately owned livestock were permitted in Area A, Mr. A1’s parents’ household privately kept about 10 sheep and 2 to 3 heads of cattle.

A significant shift occurred in the seasonal migration patterns of Mr. A1’s parents’ household during the People’s Commune period. The following analysis delineates these changes into two distinct phases.

3.1.1. Seasonal Migration in the 1960s

In the 1960s, the parents of Household A1 undertook five to six seasonal migrations per year, moving their livestock to campsites appropriate for each season (Figure 3). The straight-line distance of each migration was about 55 km, yielding an annual migration range of 50–60 km comparable to that of pastoralists around Xilinhot during the same period. However, the migration patterns differed: pastoralists around Xilinhot generally followed nearly linear routes. This type of migration is characterized as a “summer–winter round trip pattern” [] (p. 78). The summer camp was located at Ulangan Chab, approximately 2 to 3 km east of the current gacha center in Area A. Ulangan Chab means “Red Valley” in Mongolian. The site is also referred to as San Qin. The name San Qin derives from three Han Chinese men with the surname Qin who arrived from southern China in the late 1950s to produce felt for yurts. In the early 1960s, episodes of heavy rain and flooding submerged their homes. The area subsequently became known by this name.

Situated approximately 2 km northwest of the summer camp is a cluster of lakes known as Gun Togurim, which translates as “deep lake” in Mongolian (Figure 3). The surrounding area is characterized by rich vegetation and expansive wetlands. The availability of wells and lakes provided abundant water resources, making the site particularly well-suited for summer grazing. As Mr. A1 recalled, “At that time, around 10,000 head of livestock came daily to drink water at the lakes. More than half of the gacha’s livestock were probably grazing around here.” In addition to these lakes, a well called Sayin Khodog, meaning “good well” in Mongolian, is located about 3 km northwest of the summer camp. Another well, commonly referred to as the gacha well, is situated at the center of the gacha (Figure 3). All of these wells were actively utilized during the summer months. Notably, the summer camp’s elevation is the lowest among the four campsites, at approximately 850 m. Households typically relocated five to six times annually, with two to three of these moves occurring during the summer season.

The autumn camp is located at Sayin Khodog well, about 3 km northwest of the summer camp (Figure 3). The A1 parents’ household typically relocated from the summer camp to the autumn camp in early September. As with the summer camp, access to water sources was a crucial factor influencing both migration routes and the timing of seasonal movements. The name of the autumn camp is derived from its main water source, Sayin Khodog well. According to A1, the autumn camp was not merely a temporary campsite but also served not only as a temporary stopover but also as a strategic base to prepare for the transition to the winter camp. The elevation is approximately 1100 m, slightly higher than the summer camp. Migration from the autumn camp to the winter camp generally took place in late November. As the winter camp was located at a considerable distance from wells, herders depended primarily on snow as their principal water source during this period. According to A1, “At that time, the timing of the move from the autumn camp to the winter camp depended on when the snow would fall.” Ideally, a snow accumulation of approximately 10 cm was considered necessary to initiate the move. Comparable practices have been documented among pastoralists in Mongolia, where the onset of snowfall frequently determines the timing of migration to winter camps [] (p. 37). The absence of snowfall could lead to a pastoral disaster known as black dzud, in which livestock are unable to access both drinking water and forage [], [] (p. 8). Snow thus fulfills a dual function in winter pastoralism: it supplies meltwater for livestock consumption and shields dry grass from wind erosion, thereby preserving essential fodder [] (p. 11).

The winter camp was located in Otonayin Oboljiye, approximately 20 km northwest of the autumn camp at Sayin Khudug (Figure 3). Otuna refers to a wild animal that inhabits rich grasslands, and Oboljiye means winter camp in Mongolian. On occasion, the family utilized an alternative winter camp situated about 3 km east, known as Khutuliin Tuimer, meaning “hill fire,” due to its tendency to be prone to wildfires. This secondary site was located in a hilly region with abundant vegetation and, among all seasonal camps, had the highest elevation at approximately 1270 m (Figure 3). While pastures lacking water sources were not used outside the snowy season, winter snowfall provided a vital drinking source for livestock, making such otherwise waterless pastures usable during this period.

In spring, the household moved to Khubuiin Khulai, located about 16–17 km southeast of the winter camp (Figure 3), which means “rich valley” in Mongolian. Positioned in a depression, this pastureland was notable for its abundance of Achnatherum splendens (locally known as deres), with the tall grasses retaining warmth and making it particularly suitable for grazing young livestock. The spring camp was typically established in early March. About 4–5 km southeast, Khubuiin Nuur, a lake used as a water source for livestock, is situated nearby. Roughly 2 km south of the camp is a well known in the area, Hoshimagiin Khodog, which was dug in the 1930s and financed by selling 70 horses. It is renowned for its high water quality and abundant supply. During the severe drought of 1966, when other lakes dried up, it supplied water to approximately 20,000 head of large livestock each day. As of March 2021, over 20 herding households continued to use the well. The elevation of the spring camp was approximately 850 m, the same as the summer camp (Figure 3).

During the severe droughts and dzud in the 1960s, otor movements were undertaken. Otor refers to the movement of herders alone or with minimal company with their livestock, which differs from the regular seasonal migrations that closely follow the four seasons []. The otor routes taken by A1’s parents’ household covered a wide area reaching north to the Mongolian national border, south to the southern regions of Sunit Left Banner, and sometimes even crossing into Chakhar. They also traveled eastward to places as far as Ujumchin, over 600 km away, and Hulunbuir League, more than 1000 km from their home area. Among these, the most significant otor for Mr. A1 was the journey undertaken during the 1963 drought, which particularly devastated area A. In response to the drought, and coordinated by the People’s Commune, A1’s parents’ household, under the coordination of the People’s Commune, took a portion of the livestock they were responsible for and set out on an otor. They passed through Abag Banner and East Ujumchin Banner, eventually reaching Hulunbuir League. The migration lasted several months, and the round-trip distance was about 2000 km. Some households reportedly remained in Abag Banner. Mr. A1 was the only member of his family to return to area A in 1964, the year following the drought, while his parents and older brother returned to area A with the livestock the following year, in 1965. The entire roundtrip otor therefore spanned approximately two and a half years. Another drought occurred in 1966, prompting A1’s parents and older brother’s household to again set out on an otor to East Ujumchin Banner, but they returned the following year, in 1967. Mr. A1 did not participate in this second otor.

3.1.2. Migration in the 1970s

In 1966, the Cultural Revolution began across Inner Mongolia. From 1966 to 1973, Mr. A1’s life diverged from that of most pastoralists, as he was temporarily assigned to various types of labor, including serving as a secretary for the People’s Commune, which disrupted his herding activities.

In 1973, A1’s parents constructed their first permanent livestock shelter at the spring camp. This was part of a new agricultural policy known as the “Learn from Dazhai” campaign, which had been promoted in Area A since the spring of 1972. In Inner Mongolia, a regional conference titled “Learn from Dazhai in Agriculture” was held in November 1971, and a political campaign under the same slogan was launched in Area A in April 1972 [] (p. 58). Dazhai is a village located in Zhai Township, Xiyang County, Shanxi Province, China, and the campaign emphasized self-reliance and infrastructural improvements to boost agricultural and livestock production. As a result of this campaign, permanent shelters and mud enclosures began to be constructed across Area A, particularly at winter and spring camps, beginning in 1973.

In 1974, Mr. A1 got married. His wife was also a herder from the same people’s commune. Together with his wife’s parents, they formed a two-household hot ail and were put in charge of managing 800 sheep and goats belonging to the commune. For A1’s family, this number, along with the newborn animals added each spring, represented the maximum they could realistically manage.

Compared to the 1960s, the length of A1’s annual seasonal migration became shorter (Figure 3), and the number of seasonal moves decreased to four or five times per year. This change was mainly due to a shift from grazing across the entire gacha area to grazing within smaller units called dogailan. A dogailan is a subunit of the gacha and means “group” in Mongolian. At that time, Area A was divided into 5 such groups, and herders were required to graze their livestock within their designated group. Regarding this system, Mr. A1 remarked that such division was likely implemented for administrative convenience rather than considering the actual conditions and interests of the herders.

In summer, since seasonal movements were then conducted within the group unit, Mr. A1’s family set up their camp about 3 km east of Khoshimogiin Khodog well. To the southwest of this summer camp lies Khubiin Nuur Lake (Figure 3), which served as the primary water source for their livestock. Because the migration distance had become shorter, selecting the exact campsite area often required negotiation with other herding families, and choices were made based on the circumstances at the time.

In autumn, they camped at a place called Gobiin Hub, about 8 km northwest of the summer camp. The name means “a small hill in the Gobi” in Mongolian. About 5 km southeast of this autumn camp lies Khoshimogiin Khodog well, which the A1 family had used in the spring.

In winter, they moved to a place called Honhoriin Ebuljiye, located 4 to 5 km northwest of the autumn camp (Figure 3). The name means “winter camp in the valley” in Mongolian. As in previous decades, they primarily relied on snowmelt for water during both autumn and winter.

In spring, as in the 1960s, the A1 family set up their camp at Khubuiin Khulai. As previously mentioned, a permanent livestock shelter was constructed by the People’s Commune at this spring camp during the Cultural Revolution in 1973. About 4 km southeast of the spring camp lies Khubiin Nuur Lake, and approximately 2 km further south is the Khoshimogiin Khodog well (Figure 3).

Since 1974, the A1 family’s total annual migration distance had decreased to around 15 km. The distance between seasonal camps decreased from 55 km in the 1960s to about one-quarter of that. Along with this reduction, their migration pattern shifted from a rectangular route connecting various camps to an almost linear movement (Figure 3). Regarding access to water resources during this period, as in the 1960s, lake water was mainly used in summer, whereas shallow wells were used in other seasons. Since land distribution and pasture fencing had not yet progressed, the family could move their livestock flexibly to make optimal use of available water resources.

In 1977, a severe dzud struck, forcing all of Area A’s residents to evacuate to Khongor Sum, located near the Mongolian border and approximately 200 km north of Sunid Left Banner. Of the 15,682 small livestock in the area, approximately 1400 were lost, along with about 600 out of 1931 cattle and 1600 out of 2509 horses [] (p. 112). Despite this, the damage in Area A was relatively low compared to other parts of Sunid Left Banner, largely due to the continued practice of otor.

In the summer of 1978, the A1 family returned from their otor site in Khongor Sum. Beginning in 1979, under the direction of the People’s Commune, the A1 family was consolidated with two other households to form a new hot ail, which was collectively responsible for managing about 1000 small livestock and 70 cattle.

The otor in 1977 was confined within Sunid Left Banner, with shorter migration distances compared to the long-distance otor of the 1960s. Following the dzud, the People’s Commune focused on constructing permanent facilities at winter and spring camps. Two trucks were allocated to Area A for transporting stone materials, leading to the construction of new stone livestock shelters. The A1 family built a shelter and corral at their spring camp, to be shared among the three households in the hot ail.

Thus, the dzud countermeasures sped up the process of establishing fixed spring camps, though this did not immediately reduce the range of seasonal migration. Additionally, the sedentarization observed in the 1960s and 70s was not linked to rapid population growth or increased livestock numbers during that period. By the late 1970s, approximately 150 migrants from southern China had settled in Area A, the majority of whom were employed as pastoral workers under the People’s Commune.

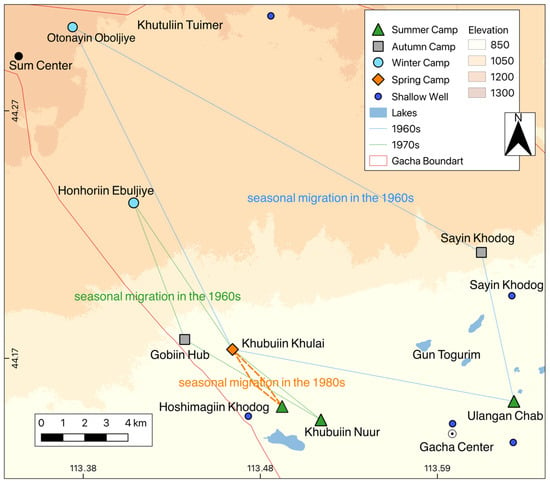

3.2. Migration After the Reform and Opening-Up (1984–1996)

The Reform and Opening-Up policy began in 1978. As part of this, the GHCP was introduced in 1984. In Area A, the Bayanuul People’s Commune was restructured and renamed Bayanuul Sum in 1983, and production teams were reorganized into gacha units. In 1984, livestock was distributed to individual households, and the People’s Commune was dissolved. At that time, A1’s household had five members and received 112 sheep, 17 goats, and 13 cattle [] (p. 82). They also privately owned 5 additional cattle. As mentioned earlier, horses and camels were mainly given to three or four households within the gacha. The hot ail is herding style remained consistent with practices from the 1960s and 70s, with the three households continuing to herd their small livestock together.

In 1984, pastureland was allocated based on the area traditionally used by each hot ail, and herding within the hot ail allocated range was encouraged. However, no fencing was installed to create enclosures. As a result, the seasonal migration distance for Household A became even shorter than in the 1970s. The total annual migration distance decreased to about 4 km, about one-quarter of the 15 km reported in the 1970s. Accordingly, the frequency of seasonal migration per year dropped from 5 or 6 times in the 1960s and 1970s to generally just 2 or 3 times.

Specifically, in summer, a camp was set up approximately 1–2 km north of Lake Hubin Nuur to ensure access to water resources (Figure 4). Livestock were freely grazed, and access to water resources remained flexible for large livestock in particular, as before.

Figure 4.

Annual seasonal migration in the 1980s (locations were verified with A1 during field visits, and GPS coordinates were recorded for each campsite; data visualization was performed using QGIS).

In autumn, it was sometimes the case that only the livestock were moved, without establishing a new camp. In these instances, the family typically stayed at the spring camp.

Since the winter camp used in the 1970s was allocated to another hot ail, the family began overwintering at the spring camp as well. The shrinking of the grazing range also made it more practical to spend the winter at the spring camp, where permanent livestock shelters had been constructed. Water was obtained from the Khoshmogiin Khodog well.

Although a dzud occurred in 1989, no otor migration was carried out. Nevertheless, the scale of damage was less severe compared to 1977. The household managed to get through the winter by feeding hay to the livestock at the spring camp. The hay was procured from within the gacha or from the central part of the banner, and at that time, hay could reportedly be obtained free of charge within the gacha.

3.3. Sedentarization After Land Distribution (1996–Present)

3.3.1. Grazing Within Distributed Grazing Lands

In 1996, grazing land was formally allocated to individual households. In Area A, 5% of the total land area was designated as communal land for use by the entire gacha, while the remaining land was divided such that 70% was distributed equally based on the number of household members and 30% was allocated according to the number of livestock owned by each household.

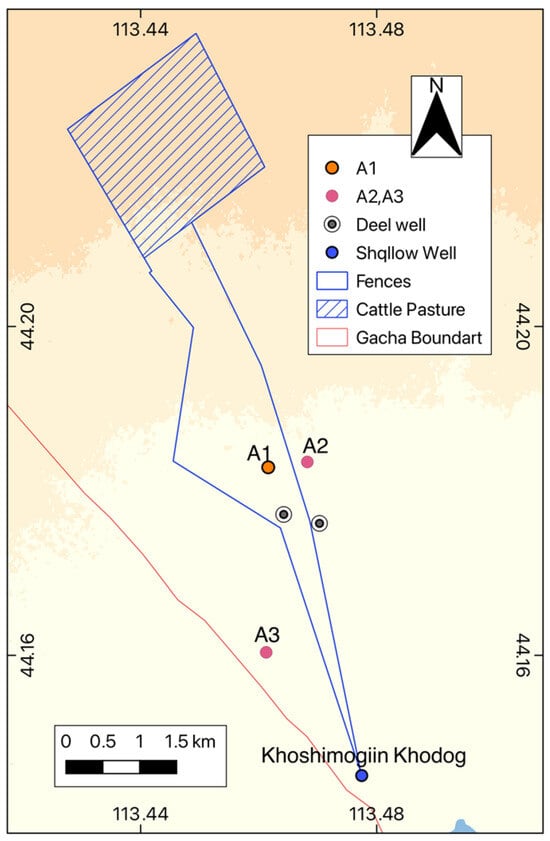

The distribution of land among the three households in the hot ail was as follows: Household A1 received 886.7 hectares, A2 received 540 hectares, and A3 received 1074.6 hectares. However, in the case of Household A2, approximately one-third of its land (267 hectares) was missing from the allocation due to errors in measurement during the distribution process. As of the time of the survey in March 2021, this issue remained unresolved despite ongoing discussions between the relevant banner authorities and the gacha chief. According to the surveyed households, such problems were widespread throughout Area A and were viewed as extremely difficult to address. The pasture allocated to Household A1 was around the spring camp pasture they had previously used.

Household A2 was allocated pastureland about 400 m east of its previous spring camp, while Household A3 received land approximately 2.5 km southwest of A1’s former spring camp (Figure 5). As a result, the original hot ail was effectively dissolved. To ensure continued access to the Khoshimogiin Khodog well, located approximately 4 km to the southeast, Household A1 was allocated a long, narrow, north–south-oriented parcel of land. From 1996, A1 divided this pasture into two main sections: the northwestern portion was used as winter grazing land, while the area stretching from the residence to the shallow well was used for grazing from spring through autumn (Figure 5). Additionally, the Khubiin Nuur area and the summer campsite used during the 1980s were reassigned to other herding households.

Figure 5.

Grazing land by household since 1996 (Rangeland boundaries were delineated using QGIS and Google Maps and subsequently verified with A1).

3.3.2. Fencing of Allocated Land

After the land was allocated in 1996, no fences were initially installed, which allowed continued mobility of livestock and access to Khubiin Nuur. However, from around 2002 onward, the enclosure of pastureland gradually increased, and grazing within individually allocated parcels became the standard practice.

In 2002, Household A1 enclosed a 40-hectare plot located about 3.5 km northwest of their home, which was at the time considered the best grazing area, and began using it primarily as winter pasture. Within this enclosure, cattle were grazed from the first snowfall in November until May, while sheep and goats grazed from late November until the birthing season in March. From late May through October, grazing shifted to a narrow strip of land near the residence. As a result, pasture use essentially followed a “seasonal division of pastures” with specific areas reserved for different periods of the year. Furthermore, only moving their livestock during summer and winter represents a modified form of seasonal migration. By this time, Household A1’s grazing range had decreased to about one-third of the area they used during the hot ail period of the 1980s.

Due to the advancement of pastureland enclosure, Household A1 could no longer move their livestock to Lake Khubiin Nuur and was forced to rely on a shallow well year-round. The Khoshimogiin Khodog well, located approximately 4 km southeast of their residence and originally dug in the 1930s (Figure 6), was shared by up to 20 herding households, requiring coordination of access times, which placed a substantial burden on the household, especially during the summer months. Furthermore, after 2000, prolonged droughts led to a significant decline in shallow well volumes, closely reflecting the observed TWS variations (Figure 1d). In response, Household A1 installed a 1200-yuan water storage tank (1 yuan ≈ US$0.14) behind their livestock shelter in 2004, funded entirely by the household, to store transported water for sheep and goats and stabilize their supply during summer. Larger livestock continued to rely on the Khoshimogiin Khodog well. Between 2004 and the successful drilling of a deep well in 2014, the household had to transport water daily during the summer months, which placed considerable strain on their resources.

Figure 6.

Current grazing land and fences of household A1 (locations and boundaries of the wells and settlements were identified using Google Maps and QGIS and subsequently verified with A1).

In 2014, with support from a local government project, Household A1 had a deep well drilled approximately 500 m from their residence (Figure 6). The total cost was 30,000 yuan, of which A1 contributed 10,000 yuan. The deep well is 55 m deep, and the water is of high quality and suitable for human consumption. It significantly eased water supply for livestock. In the same year, a water storage tank was installed on the former winter pasture, also with government support. The tank cost 18,000 yuan, with A1 paying 6000 yuan, and this enabled use of the distant former winter pasture even during summer. As of 2021, Household A1 reserved the elongated pasture between their settlement and the shallow well exclusively for small livestock (sheep and goats), while the former winter pasture to the northwest was used for large livestock (cattle, horses, and camels). The storage tank provided water for large livestock, which was transported every 2–3 days in summer and once every 40–50 days in winter due to snowfall.

The drilling of the deep well and the installation of the water tank, both carried out after the land distribution, transformed A1’s pasture utilization from the previous “seasonal division of pastures” to a more settlement-centered system of “pasture allocation by livestock type” In other words, the pastoral system, which had previously relied on livestock mobility, shifted toward a model in which different zones were designated for different types of livestock, and each type was managed within its own exclusive pasture area (Figure 6). Also, because improved dual-purpose cattle (for both milk and meat) are sensitive to cold, they can no longer use snow in winter [] (p. 9).

During the author’s field visit in June 2019, enclosures were actively being constructed in the area extending from the former winter pasture in the northwest to the deep well. According to Mr. A1, livestock from the neighboring Household A2 often entered A1’s pasture, while A1’s animals sometimes wandered beyond their boundaries, frequently causing disputes between the households. Mrs. A1 noted that the installation of fences provided a greater sense of security. By July 2019, Household A1 had installed fences around all of their pastures, marking a significant shift from traditional land use patterns.

From a pastoralist perspective, the erection of fences is contentious because it restricts livestock mobility, increases the cost and complexity of pasture management, and may exacerbate disputes when animals enter neighboring enclosures. Nevertheless, this change can be considered an inevitable consequence of formal land redistribution, and the source of conflict lies not in the fences themselves but in the land redistribution process.

Thus, the establishment of fencing associated with land distribution has altered pastoralists’ access to water resources, thereby necessitating a reorganization of water use and grazing strategies. Moreover, households without wells on their allocated land are forced to transport water from external sources year-round as fencing restrictions intensify, a burden that is likely to grow more severe over time. Among the 28 households surveyed in Area A, 7 households (25%) did not own either deep or shallow wells within their pastureland. Of the remaining 21 households, 10 (35.7% of the total) had access to both deep and shallow wells, while 18 (64.2%) possessed deep wells. These findings highlight not only the unequal distribution of water resources but also the substantial economic and labor burdens imposed on affected households by water transportation [].

3.3.3. Construction of Fixed Facilities

As pastoralists settled, the construction of fixed infrastructure, including livestock barns and houses, accelerated rapidly, a trend evident in Area A. Since the 1996 pasture distribution, Household A1 systematically expanded facilities over nearly two decades, including livestock sheds, enclosures, and permanent dwellings. In 1999, three years after land distribution, A1 built their first brick livestock shed (80 m2) with a tiled roof and a stone enclosure (300 m2) for small livestock, at a total cost of 18,000 yuan—roughly equivalent to 45 sheep or 9 cattle at the time. In 2002, they added a second shed (100 m2), an additional enclosure (200 m2), and hay/feed storage (100 m2), partially funded by a local government project. The total cost was 36,000 yuan (A1: 10,000 yuan; government subsidy: 26,000 yuan). These sheds are mainly used during winter and spring birthing seasons. In 2011, with additional government support, A1 constructed a new permanent dwelling, a single-story brick house with a tiled roof and a floor area of 40 m2, at a total cost of 60,000 yuan (A1: 28,000 yuan; government subsidy: 32,000 yuan). This dwelling facilitated a more sedentary lifestyle by allowing the storage of goods, installation of a generator, and the use of both floor and steam-based heating systems.

Despite these infrastructure improvements, Household A1 still resides in a ger. As Mr. A1 explained, “We are accustomed to the ger and do not wish to move into the fixed house. It is easy to enter and exit, warm in winter, and cool in summer.” An additional ger on the eastern side of the homestead serves as a kitchen for dairy processing and meal preparation. In 2014, without government support, A1 constructed a brick livestock shed and enclosure on their winter pasture for crossbred cattle raised for both milk and meat, at a cost of 40,000 yuan. These crossbred cattle are more sensitive to cold, requiring additional feed, water, and a more robust shelter to maintain their health during harsh winters. In 2016, a garage was added to the west side of the fixed house to store a motorcycle, a four-wheel-drive vehicle, and a small truck. Despite the increasing frequency of droughts since the 2000s, A1 has ceased practicing otor and adapted by feeding all livestock with stored hay and fodder.

A similar situation to that observed in A1 household’s fixed facility construction was found among the other 27 households. In terms of fixed livestock barns, with one exception, all households have constructed barns, with 14 households having built a second barn and 3 households having built a third. Regarding the timing of construction, 4 barns were built before 1984 (during the People’s Commune period), and 9 barns were built between 1984 and 1996, representing an increase of about 2.2 times. Following the land distribution in 1996, 31 new barns were constructed, with 14 households building a second barn and 3 households building a third (Table A2) [] (p. 114). Regarding fixed houses, only 2 were constructed during the People’s Commune period (No. 2 and No. 6, both in 1982). Between 1984 and 1996, following the distribution of livestock, 10 fixed houses were built. After household-based land distribution in 1996, 19 new fixed houses were constructed. Among these, No. 9 and No. 21 each built a second fixed house. As of the survey, three households (No. 13, No. 19, and No. 20) had not yet built fixed houses and were still residing in gers (Table A3) [] (p. 114). It is evident that the construction of livestock barns and fixed houses by pastoralists is closely linked to the distribution of pastureland. Notably, the surge in barn construction following the 1996 land distribution is particularly significant [] (p. 113). This transformation is a direct result of the sedentarization policy, which gained momentum after the 1996 land distribution when the government intensified its encouragement of sedentarization through project-based support. Furthermore, this trend suggests that pastoralists tend to prioritize the construction of livestock barns over fixed houses, likely to safeguard their herds from disasters such as dzud.

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in Pastoral Strategies

Previous studies have noted that during the People’s Commune period, the expansion of fixed facilities contributed to the reduction in seasonal migration [,,]. In particular, the dzud of 1977 accelerated the construction of such facilities and has often been regarded as the true beginning of sedentarization []. However, in Area A, the development of fixed facilities did not directly lead to reduced mobility. Rather, the reduction in household A1’s migration distance was primarily attributable to institutional factors, such as the promotion of grazing at the dogailan level during the Cultural Revolution of the 1970s and the implementation of land distribution policies at the hot ail level under the GHCP in the early 1980s. The introduction of household-based land distribution in 1996 further advanced pasture enclosure, making sedentarization decisive. Since the 2000s, government-supported construction of permanent houses, barns, and fences has consolidated this process, rendering sedentarization irreversible. During this period, household A1’s migration distance steadily decreased from approximately 55 km in the 1960s, to 15 km in the 1970s, and to about 4 km between winter and summer camps in the 1980s, ultimately culminating in complete sedentarization after 1996 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Periodic stages of sedentarization.

With sedentarization, the development of fixed infrastructure advanced in tandem with changes in livestock species and management practices. Notably, the introduction of improved dual-purpose cattle, which are less adapted to arid environments, necessitated controlled feeding and management practices distinct from traditional pastoral grazing []. Sheep herding also became increasingly management-dependent, resulting in greater reliance on hay and purchased feed (Table 2). Patterns of pasture use shifted from “seasonal division of pastures” to “allocation by livestock type” As highlighted in previous studies, these transformations have been linked to rising livestock production costs [], land degradation [,,], livestock commodification [,,], increased financial risks [,], impoverishment [], and heightened social vulnerability [].

Shifts have also taken place in strategies for coping with natural disasters. Traditionally, pastoralists responded to extreme weather events, such as droughts or dzud, by undertaking long-distance movements with their herds (otor). In the 1960s, household A1 frequently practiced such migrations. However, following sedentarization from the 1980s onward, long-distance movements declined, and the principal strategy shifted to maintaining livestock with hay and supplementary feed (Table 2). While this method can improve short-term survival, it may reduce the long-term flexibility to respond to extreme weather events, thereby increasing vulnerability to environmental change [,].

In contrast, in relatively wetter or riverine regions where irrigated agriculture is feasible such as Ordos [,], Horqin [], Ulanchab [], and Ejina [,] sedentarization was primarily driven by agricultural development policies. These policies, along with the influx of external populations, promoted the expansion of cultivated land and the establishment of villages [,,,,,,,]. A mixed production system integrating agriculture and pastoralism subsequently emerged [,]. Therefore, the sedentarization process in the arid Area A exhibits distinct characteristics compared with those observed in other regions.

In household A1, despite the construction of a permanent house, the couple continued to reside in their ger, with the house serving mainly auxiliary purposes such as storage. This case demonstrates that, even with the sedentarization of pastoral production, gers remain the preferred dwelling owing to their climatic suitability and congruence with traditional lifestyles. In other words, government-supported construction of permanent houses does not necessarily align with pastoralists’ preferences or traditional ways of life, potentially leading to a mismatch. Among the 28 households surveyed, only three (10.7%) had a positive perception of sedentarization, while 25 households (89.2%) had a negative perception. Furthermore, 21 households (75%) continue to use gers (Table A3) [] (p. 114). These findings underscore the importance of recognizing that pastoralists frequently maintain critical perspectives toward sedentarization policies.

However, sedentarization also provides several benefits for pastoralists. First, it can improve living conditions. Although household A1 continues to reside in a traditional ger, younger generations may be more inclined to adopt a settled lifestyle, gaining access to better housing and a more stable living environment. Indeed, in Area A, there is a tendency for younger pastoralists in particular to purchase apartments in towns (Table A3) [] (p. 114). Second, the land distribution system offers a minimum livelihood guarantee. Under the collective land use system, poorer pastoralists may be marginalized due to competition for resources.

4.2. Changes in Water Access

A defining characteristic of arid regions is the temporal and spatial unevenness of water resources []. The case of household A1 illustrates that during the People’s Commune period (1960s–1980s), seasonal migration allowed for flexible combinations of lake water, snowmelt, and shallow wells to address this uneven distribution (Table 2). Such transhumant strategies formed a crucial basis for the resilience of pastoralism in arid zones, as corroborated by previous studies [,]. However, after land distribution and pasture enclosure from the 2000s onward, household A1 lost access to lake water and became increasingly dependent on shallow wells. Consequently, issues such as prolonged waiting times for water arose in summer. In other words, sedentarization has reduced flexibility in resource use, exacerbating water-related inequality and vulnerability []. This trend mirrors findings from arid regions in Africa, where sedentarization has likewise been linked to increased risk [,,].

To overcome these constraints, household A1, with support from government projects, installed a deep well at their settled homestead and a water storage tank at their former winter pasture, thereby establishing a water transport system. Consequently, their water use shifted from reliance on shallow wells to a system centered on deep wells and storage tanks (Table 2). The following section summarizes the effects of this transformation under two main points.

First, deep wells and water storage tanks have enhanced short-term convenience by reducing the labor required to move livestock to water sources, thereby alleviating the workload. However, these advantages are accompanied by substantial economic and labor costs. Even with subsidies, drilling deep wells entails significant household expenses, and the initial investment is considerable []. Additional ongoing costs arise from pump failures or water quality deterioration, which may affect the health of both livestock and people []. Likewise, reliance on storage tanks necessitates water transport, sustaining both labor and financial burdens. Thus, while deep wells and tanks increase “convenience” they also introduce “new vulnerabilities” marking a fundamental shift from traditional transhumant strategies.

Second, the use of deep wells directly affects inter-household inequalities and the sustainability of groundwater resources. Among the 28 households surveyed, seven (25%) lacked wells and faced severe water insecurity (Table 1). In contrast, 18 households (64.2%) with deep wells were able to generate economic benefits through water sales []. Additionally, reliance on deep wells entails the risk of groundwater depletion []. In Area A, groundwater levels have declined rapidly since 2000 (Figure 1d). This situation exemplifies the “invisible” resource degradation associated with the so-called “well myth” [] (p. 194).

Although this study provides valuable insights into the sedentarization process through the case of Household A1, its findings are subject to certain limitations and uncertainties. Because the analysis focuses on a single household, the results may not fully capture the diversity of pastoralist experiences across Inner Mongolia. Furthermore, uncertainties remain regarding the interpretation and generalization of the findings, as they are influenced by temporal fluctuations in environmental conditions and the subjective nature of oral histories. To enhance the generalizability and robustness of future research, larger sample sizes and cross-regional comparisons should be undertaken. In addition, the complex interactions among social, cultural, economic, and environmental factors necessitate integrated, interdisciplinary approaches.

Based on the findings of this study, a key policy implication is that, in areas where nomadic pastoralism still persists, land use changes should be carefully evaluated for their potential impact on water access and pastoral management costs. Institutional mechanisms should also be established to support the continuity of mobile pastoralism while respecting local social and cultural contexts.

5. Conclusions

The sedentarization of Area A was primarily driven by policy interventions, which fundamentally reshaped both pastoral practices and access to water resources. These findings demonstrate that sedentarization does not inherently improve pastoral livelihoods; rather, it is a complex process that can introduce new vulnerabilities and elevate exposure to diverse risks.

During the People’s Commune period, collective land distribution systems, such as the dogailan and hot ail, reduced Household A1’s seasonal migration range. As mobility contracted, spring camps began to include fixed facilities. After the dissolution of the commune system, the introduction of the GHCP and the transition to household-based land distribution further accelerated the sedentarization process. As a result, Household A1’s pastoral strategy shifted from flexible mobility to a “seasonal division of pastures” and subsequently to a “pasture allocation by livestock type”, decreasing herd movement adaptability and intensifying dependence on supplementary fodder.

With sedentarization, the household shifted from relying on natural sources such as lake water and snowmelt to using shallow wells, deep wells, and water storage tanks. Although these changes temporarily stabilized the water supply, they also generated new challenges, notably increased labor, higher costs, and the looming threat of groundwater depletion. The decline in TWS further intensified these pressures, highlighting the long-term difficulties of achieving sustainable water use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.B.; Methodology, U.B.; K.K.; Validation, U.B.; K.K.; Investigation, U.B.; Data curation, U.B.; Writing—original draft, U.B.; Writing—review & editing, U.B.; K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This field research was supported by the 2020 Scholarship for International Students (April 2020–March 2021) from the Heiwa Nakajima Foundation and the 2021–2023 Scholarship (April 2021–March 2024) from the Rotary Yoneyama Memorial Foundation. We gratefully acknowledge the generous support provided by these organizations and all those involved. Additionally, this field research was conducted with the support of the research project Sedentarization of Pastoralists under Environmental Change (2020–2021) and Human-Livestock Relationships under Environmental Changes (2022–2024), Graduate School of Humanities and Studies on Public Affairs, Chiba University. This work was also supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 18H03608.

Data Availability Statement

The interview data are not publicly available due to privacy issues.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to Atsushi Yoshida, Associate Feifan Zhou, Shingo Odani, and other faculty members of the Department of Eurasian Languages and Cultures, Graduate School of Humanities, Chiba University, for their valuable guidance and insightful comments provided through lectures and seminars during the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GHCP | Grassland Household Contract Policy |

| TWS | Terrestrial Water Storage |

| EWH | Equivalent Water Height |

| GRACE | Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment |

| CSR | Center for Space Research |

| JPL | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| GSFC | Goddard Space Flight Center |

| SSU | Sheep Standard Units |

| HH Age | Household Head Age |

| HH Size | Household Size |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Household Survey Question.

Table A1.

Household Survey Question.

| Part 1. Process of Sedentarization 1.1 Household Head Information: Name, age, gender, ethnicity, occupation (pastoralist/other), place of origin (native/migrant: year and reason) 1.2 Changes in Residential Type: Ger / fixed house / urban residence (year built, size, funding source) 1.3 Fixed Facilities: Livestock barn, feed storage, bathhouse, etc. (year built, size, funding source) 1.4 Overall Evaluation: Perceived livelihood changes; advantages and disadvantages (cultural, economic, environmental) 1.5 Future Outlook: Preferred pastoral production model; intention to continue pastoralism or move to an urban area | Part 2. Household Economic Conditions 2.1 Family Composition: Total number of members, elderly (aged 60+), children, students 2.2 Sources of Income: Livestock sales, wool and leather, pasture lease, hay sales, salary income, environmental subsidy programs, others 2.3 Expenditures: Pastoral expenses, Living expenses 2.4 Borrowing: Source (bank/private), amount, and purpose 2.5 Economic Changes: Shifts in income and expenditure structure and stability after sedentarization |

| Part 3. Water Access Conditions 3.1 Well Availability: With well: type (shallow/deep), distance, year constructed, funding source, capacity, water transport, water sales; Without well: water transport (frequency, distance, quantity, cost, supplying household); Other sources: river or lake (perennial/seasonal), changes in water volume 3.2 Changes in Water Use: Comparison with the past (improved/deteriorated); social and environmental factors 3.3 Coping Strategies: Well drilling, water purchase, leasing, or other measures | Part 4. Pastoral Strategies 4.1 Livestock Changes: Number and composition by species (from People’s Commune period to present) 4.2 Pasture Use: Total area, type (mountain / sandy / grassland), and fencing history 4.3 Pasture Condition: Comparison with the People’s Commune period (improved / unchanged / deteriorated) 4.4 Causes of Degradation: Sedentarization, decreased precipitation, fencing, hay cutting, mining development, pasture leasing, others 4.5 Vegetation Changes: Evaluation of major vegetation increases or decreases and their causes 4.6 Policy Evaluation: Awareness and perceived effects of grass–livestock balance policy, grazing bans, subsidy programs, and ecological migration |

Table A2.

Number of barns for 28 households in Area A (modified from [], p. 114).

Table A2.

Number of barns for 28 households in Area A (modified from [], p. 114).

| No. | Construction Period | Area (m2) | Cost (Yuan) | Government Subsidy (Yuan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1982 | 40 | People’s Commune | 0 |

| 8 | 1982/2000 | 50/80 | People’s Commune/20,000 | 0 |

| 10 | 1982/2000/2005 | 30/80/60 | Commune/20,000/8000 | 0 |

| 5 | 1983/2003/2011 | 40/60/60 | Commune/20,000/30,000 | 5000/22,000 |

| 2 | 1988/1994 | 60/80 | 800/6000 | 0 |

| 4 | 1988/2001 | 60/60 | 2000/26,000 | Second 16,000 |

| 18 | 1991/1993 | 30/60 | 800/10,000 | 0 |

| 17 | 1991/2012 | 140/60 | 9000/30,000 | Second 22,000 |

| 3 | 1992/2009 | 30/130 | 1000/60,000 | 0 |

| 26 | 1993/2012 | 60/80 | 1000/30,000 | Second 22,000 |

| 11 | 1994/2000/2004 | 80/80 | Total 70,000 | 0 |

| 9 | 1996/2001 | 80/40 | 8000/5000 | 0 |

| 16 | 1996/2007 | 140/60 | 8000/15,000 | 0 |

| 15 | 1997/2002 | 40/100 | 10,000/13,000 | 0 |

| 1(A1) | 1999/2002 | 60/60 | 18,000/26,000 | Second 16,000 |

| 27 | 1999/2011 | 100/80 | 3000/30,000 | Second 22,000 |

| 22 | 2000 | 60 | 15,000 | 0 |

| 14 | 2002 | 80 | 20,000 | 0 |

| 19 | 2004 | 80 | 8000 | 12,000 |

| 23 | 2006 | 60 | 6000 | 0 |

| 7 | 2006 | 80 | 20,000 | 18,000 |

| 28 | 2009 | 60 | 16,000 | 0 |

| 21 | 2009/2010 | 60/50 | 3000 | 7000 |

| 13 | 2010 | 80 | 8500 | 0 |

| 12 | 2011 | 60 | 30,000 | 22,000 |

| 24 | 2011/2014 | 40/80 | 15,000/14,000 | 0 |

| 25 | 2012 | 60 | 30,000 | 22,000 |

| 20 | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table A3.

Number of fixed houses for 28 households in Area A (modified from [], p. 114).

Table A3.

Number of fixed houses for 28 households in Area A (modified from [], p. 114).

| No. | Construction Period | Area (m2) | Cost (Yuan) | Government Subsidy (Yuan) | Government Center | Ger | Perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1982/1995 | 60/60 | 3000/20,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 2 | 1982/2010 | 40/60 | People’s Commune/55,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 17 | 1985/2014 | 60/40 | 6000/61,800 | Second 46,800 | Rental | ○ | × |

| 8 | 1989 | 60 | 5000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 4 | 1989 | 40 | 8000 | 0 | No | × | × |

| 11 | 1991 | 60 | 30,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 26 | 1992 | 60 | 20,000 | 0 | Apartment | × | ○ |

| 23 | 1992/1995 | 50/60 | 15,000 | 0 | Apartment | × | ○ |

| 3 | 1992/2014 | 60/40 | 20,000/61,800 | Second 46,800 | Unknown | ○ | × |

| 28 | 1993 | 60 | 9000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 10 | 1993/2012 | 60/50 | 15,000/50,000 | 0 | No | × | × |

| 18 | 1995 | 60 | 20,000 | 0 | Rental | ○ | × |

| 22 | 2000 | 60 | 25,000 | 0 | No | × | × |

| 9 | 2000/2013 | 60/40 | 20,000/40,000 | 0 | × | ○ | × |

| 15 | 2001 | 50 | 30,000 | 0 | Apartment | ○ | × |

| 5 | 2010 | 30 | 15,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 25 | 2010 | 60 | 85,000 | 45,000 | Rental | ○ | × |

| 21 | 2010/2014 | 40/40 | 6000/61,800 | Second 46,800 | Borrowed | ○ | × |

| 24 | 2011 | 40 | 50,000 | 0 | Borrowed | × | ○ |

| 12 | 2012 | 40 | 55,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 14 | 2013 | 60 | 60,000 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 7 | 2013 | 40 | 0 | 52,000 | No | ○ | × |

| 27 | 2013 | 40 | 0 | 40,000 | Borrowed | ○ | × |

| 16 | 2014 | 70 | 90,000 | 46,800 | Single-Story | × | × |

| 1(A1) | 2014 | 40 | 61,800 | 46,800 | No | ○ | × |

| 13 | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | ○ | × |

| 19 | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | Borrowed | ○ | × |

| 20 | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | Borrowed | ○ | × |

Note: ○ = Yes, × = No. ‘Ger’ = use of traditional tent; ‘Perception’ = positive view of sedentarization.

References

- Piemontese, L.; Terzi, S.; Di Baldassarre, G. Over-Reliance on Water Infrastructure Can Hinder Climate Resilience in Pastoral Drylands. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konagaya, Y. Changes in Seasonal Migration among the Mongols in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China: A Case Study of Xilinhot City. In Migration of Ethnic Groups and Dynamics of Culture; Tsukada, S., Ed.; Fukyosha: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 69–106. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, C.; Sneath, D. The End of Nomadism? Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA. 1999. Available online: https://www.dukeupress.edu/the-end-of-nomadism (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Behnke, R. Reconfiguring Property Rights and Land Use. In Prospects for Pastoralism in Kazakstan and Turkmenistan: From State Farms to Private Flocks; Kerven, C., Ed.; Routledge Curzon: London, UK, 2003; pp. 75–107. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203987476-10 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Salzman, P.C. When Nomads Settle: Processes of Sedentarization as Adaptation and Response; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Available online: https://archive.org/details/whennomadssettle0000unse/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Roth, E.A.; Fratkin, E.M. Introduction: The Social, Health, and Economic Consequences of Pastoral Sedentarization in Marsabit District, Northern Kenya. In As pastoralists Settle: Social, Health, and Economic Consequences of the Pastoral Sedentarization in Marsabit District, Kenya (Studies in Human Ecology and Adaptation); Fratkin, E.M., Roth, E.A., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratkin, E. Pastoralism: Governance and Development Issues. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1997, 26, 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagi, Y. The Nature and Life of the Desert; Chijin Shobo: Osaka, Japan, 1990. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.D. Merging local and regional analysis of land-use change; the case of livestock in the Sahel. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1999, 89, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeya, K. Introduction: Studies of Sedentarization. Senri Ethnol. Stud. 2017, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, K. Changes in the Number of Camels in Mongolia and China: 1961–2019. In Studies on Central Asian Pastoral Societies 3: Environmental Adaptation and Pastoralism; Imamura, K., Ed.; Department of Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Contemporary Social Studies, Nagoya Gakuin University: Nagoya, Japan, 2021; pp. 29–43. Available online: https://k-imamura.com/PSCA/asia/houkoku22 (accessed on 6 October 2025). (In Japanese)

- Humphrey, C. Marx Went Away—But Karl Stayed Behind; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, T. Development Policies and Their Ideologies under the Socialist Regime: From the Perspective of “Modernization”. In Environmental History of Central Eurasia, Vol. 3: Turbulent Modern and Contemporary Times; Watanabe, M., Ed.; Rinsen Shoten: Kyoto, Japan, 2012; pp. 23–76. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.M. The barbed walls of China: A contemporary grassland drama. J. Asian Stud. 1996, 55, 665–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneath, D. Changing Inner Mongolia: Pastoral Mongolian Society and the Chinese State; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konagaya, Y. Livestock Management among the Mongols in the Process of Sedentarization: A Case Study from Xilinhot City. In Ethnic Groups and the Economy in Contemporary China; Sasaki, N., Ed.; Sekai Shisosha: Kyoto, Japan, 2001; pp. 185–207. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, J. Mobility and Settlement in Pastoralism: From the Perspective of Traditional Mongolian Pastoralism. In Tohoku Asia Research Center Series 6: Mongolian Studies Collection; Tohoku Asia Research Center: Sendai, Japan, 2002; pp. 81–97. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y. Discussion on Grassland Desertification and Nomadism. Chin. J. Grassl. China 2011, 2, 1–5. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Q. Interpreting the Grassland Dilemma: Understanding Issues in the Use and Management of Arid and Semi-Arid Grasslands; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, K. Contemporary Transformations of Pastoralists in Inner Mongolia Under “Post-Socialist Policies” and Conditions of “Desertification”: Case Studies of Agriculturalists in Ordos and Nomads in the Gobi Region; Afro-Eurasian Inland Arid Zone Civilization Studies Series 1; Comparative Humanities Laboratory, Graduate School of Letters, Nagoya University: Nagoya, Japan, 2012. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Konagaya, Y. Diversification of Pastoral Management among the Mongols in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China: Management Strategies after Rangeland Distribution. Senri Ethnol. Rep. 2001, 20, 15–45. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Seyin. The Transformation of Mongolian Nomadic Society; Inner Mongolia People’s Publishing House: Hohhot, China, 1998. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Grassland Communities Under Environmental Pressure: A Survey of Six Gacha Villages in Inner Mongolia; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Grassland Drought under Institutional Change: The Effects of Sedentarization, Grassland Fragmentation, and Marketization in Pastoral Areas. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2013, 30, 18–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Burensaiyin, B. Afro-Eurasian Inner Dryland Civilization Studies Series 6. Traces of Sedentarization and Intensification in Eastern Inner Mongolia; Comparative Humanities Research Center, Graduate School of Letters, Nagoya University: Nagoya, Japan, 2013. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]