Adaptive Urban Housing in Historic Landscapes: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Resilient Heritage in Damascus

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What tools can effectively evaluate interventions to ensure that historic cores remain livable, resilient, and culturally vibrant amid twenty-first-century challenges?

- How can a multi-criteria evaluation framework be constructed to assess adaptability and sustainability in historic urban housing?

- What indicators, measurement approaches, and weighting methods best capture the diverse requirements of heritage housing in evolving urban contexts?

2. Materials and Methods

- Historical Documents: Urban and architectural plans, municipal documents, and archives that involve the development of housing in Damascus.

- Visual and Spatial Documentation: Each case study involved gathering detailed data and visual documentation that showcase the intersection of past and present of the housing designs of historical and contemporary housing designs (especially in the case studies portfolio, p23).

- Comparative Analysis: Data from the three case studies were systematically contrasted to identify patterns and differences in how housing maintains or loses cultural identity across historical periods.

- Synthesis and Framework Development: Findings were integrated to create a comprehensive evaluation framework that aligns historical heritage with modern urban necessities through the AUG (Architectural, Urban, Green) compass.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Urban Futures and Adaptability

3.2. The Proactivity

- Spatial flexibility (open floor plans that can be reconfigured for different uses, multi-functional spaces that serve various purposes throughout the day or over time, rooms with ambiguous purposes that allow occupant choice through ambiguity) [13]: successful adaptable housing considers the integration of soft flexibility through spatial generosity and a loose-fit layout, and hard flexibility through moveable partitions and modular systems [14].

- Future-ready designs that include integrating tech advancements that address evolving needs (like smart homes, connectivity and the Internet of things, renewable energy systems, and accessibility features that can be activated when necessary). This can result in enhancing resilience. Moreover, allowing for thoughtful implementation of adaptive strategies in any urban setting including heritage contexts, where sensitive retrofitting requires methods that are reversible, modular, and non-intrusive.

3.3. Futures Studies Applications in Urban Planning

- Densification: This involves the construction, renovation, modification, or addition of buildings within the urban context, utilizing smart solutions to address the existing urban fabric.

- Neighborhood Benefits: This includes the variety of mixed functions and social diversity that can be achieved. A successful functional blend creates adaptable environments that support multi-generational housing models [4], ready to accommodate ever-changing lifestyles and living conditions, while encouraging social connectivity (positive interaction) and shared areas.

- New Forms of Living: A variety of new living spaces that add to the city’s vibrancy. Ring insists that these living environments must be adaptable to accommodate the evolving needs of residents over time, highlighting neutrality and diversity. Sustainable, affordable housing solutions are essential for forming high-quality residential communities.

- Costs: All the previous factors cannot happen without economic strategies that are aimed at reducing expenses to ensure affordability. The main cost factors are construction, compactness, standards, and minimization.

- Special Solutions: Ring shows innovative and unique approaches and rethought arrangements in her exhibition and book about future urban living, where projects from the International Urban Living Workshop and from the Self-Made City publication are presented [4]. Solutions like integrated living concepts that combine housing with workspaces, other shared amenities, and green infrastructure were promoted to support and ensure sustainable and socially inclusive urban living [4].

3.4. Adaptive Heritage Conservation in Urban Contexts

3.5. Evaluation Methodologies in Historic Landscape Management

4. The AUG Evaluation Framework

- Architectural: This includes the Urban Form and Typology Layer—establishing a cohesive relationship between density, housing typologies, compactness, and adaptability to enhance efficiency and spatial quality.

- Urban: Adaptive Open space and Future-Oriented Strategies Layer—implementing flexible, hybrid, and community-driven housing models that accommodate shifting social, economic, and technological conditions.

- Green: This includes the Sustainable Layer—integrating climate-responsive, energy-efficient, and resource-conscious design solutions within compact urban developments.

4.1. Theoretical Rationale for Three-Dimensional Division

- Urban Layer operationalizes LAND’s research [5] and Lynch’s theory [3] principles of urban vitality, measuring how individual housing projects contribute to neighborhood-scale social, economic, and spatial vibrancy—recognizing that building quality alone cannot create urban resilience without community integration.

- Green Layer integrates climate resilience standards from the UN-Habitat’s sustainability goals [29], measuring energy efficiency, thermal comfort, water management, and biodiversity—essential for long-term housing viability in contexts of climate change and resource scarcity.

- Maximizing density (Urban optimization) while neglecting adaptability or environmental performance (producing Pruitt–Igoe-like failures [32]).

- Maximizing energy efficiency (Green optimization) while neglecting social integration or heritage authenticity.

- Maximizing architectural or heritage features (Architectural optimization) while ignoring community contribution or sustainability.

4.2. Statistical Tool Validation and Calibration of the 18-Criteria Structure

5. Case Study: Damascus Urban Housing Development and Framework Application

5.1. Historical Context and Urban Evolution

- Traditional housing (until the late 19th century).

- Transitional period housing (French mandate period until independence 1920–1946).

- Modern period housing (from independence 1946 until the present day).

5.1.1. Traditional Housing

- Architectural Heritage Typologies and Patterns:

5.1.2. Housing During the Transitional Period

5.1.3. Modern Housing

- Contemporary Challenges and Pressures:

5.2. Application of Adaptive Housing Principles

6. Results

6.1. Beit Nizam—Traditional Courtyard

6.2. Villa Shoura—Transitional Period Housing

6.3. Tijara Towers—Modern Period Housing

6.4. Comparative Findings and Theoretical Implications

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Habitat for Humanity. Housing and the Sustainable Development Goals: The Transformational Impact of Housing; Habitat for Humanity: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; p. 5. Available online: https://www.habitat.org/sites/default/files/documents/Housing-and-Sustainable-Development-Goals.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- UNESCO World Heritage Conservation. Ancient City of Damascus. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/20/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Lynch, K. Chapter 1, The Image of the Environment in the Book: The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960; pp. 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, K. Urban Living: Strategies for the Future; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2017; p. 5. ISBN 978-3-86859-331-0. [Google Scholar]

- LAND Research Lab. The World’s First Sustainable District—Milano Porta Nuova; LAND: Milan, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www.landsrl.com/en/the-worlds-first-sustainable-district-milano-porta-nuova/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Beisi, J. Housing or Adaptable People? Experience in Switzerland gives a new answer to the questions of housing adaptability. Arch. Behav. 1995, 11, 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Adaptable and Universal Housing. Randwick City, 2013. In Randwick Comprehensive Development Control Plan; Adaptable and Universal Housing: London, UK, 2013. Available online: https://www.randwick.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/13740/Adaptable-and-Universal-Housing-and-Boarding-Houses.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Tarpio, J.; Huuhka, S. Residents’ views on adaptable housing: A virtual reality-based study. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Till, J. Flexible Housing: Opportunities and Limits. Archit. Res. Q. 2005, 9, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.; Optimal Living Therapy. Livable Housing Homes That Are Designed to Meet the Changing Needs of Occupants Over Their Lifetime. Available online: https://optimaltherapy.com.au/livable-housing/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Pelsmakers, S.; Warwick, E. Housing adaptability: New research, emerging practices and challenges. Build. Cities 2022, 3, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R., III; Austin, S. Adaptable Architecture: Theory and Practice. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2017, 35, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabeneck, A.; Sheppard, D.; Town, P. Housing Flexibility/Adaptability. In Architectural Design No. 2; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, Z.; Raheem, A.A. Adaptability and Modularity in Housing: A Case Study of Raines Court and Next21; Kulliyyah of Architecture & Environmental Design, International Islamic University Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2012; pp. 369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, P.; Moffatt, S. Assessing Buildings for Adaptability; IEA Annex 31 Energy-Related Environmental Impact of Buildings; Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chénier, S. Accessibility Standards Canada Releases New Standard to Help Build Adaptable Homes That Work for Everyone, Gatineau, Québec. 2025. Available online: https://accessible.canada.ca/news/accessibility-standards-canada-releases-new-standard-help-build-adaptable-homes-work-everyone (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Wood, L. Equipping Our Homes for the Future. 2025. Available online: https://www.housinglin.org.uk/blogs/Equipping-Our-Homes-for-the-Future/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. In Proceedings of the Adopted by the General Conference at its 36th Session Paris, Paris, France, 10 November 2011; Available online: https://www.whitr-ap.org/historicurbanlandscape/themes/196/userfiles/download/2014/3/31/3ptdwdsom3eihfb.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Sowinska-Heim, J. Adaptive Reuse of Architectural Heritage and Its Role in the Post-Disaster Reconstruction of Urban Identity: Post-Communist Łódź. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Huang, L.; Mao, Y.; Mustafa, M.; Isa, M. Bridging conservation and modernity: Evaluation of functional priorities for architectural heritage adaptation in China. Build. Res. Inf 2025, 53, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO; World Heritage Convention. New Life for Historic Cities: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach Explained; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/news/documents/news-1026-1.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Zambrano, J.R. Adaptive Reuse as a Strategy for Preserving Urban Heritage, Urban Design Lab. 2025. Available online: https://urbandesignlab.in/adaptive-reuse-as-a-strategy-for-preserving-urban-heritage/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hoyos, C.M. Resilience In Heritage Conservation And Heritage Tourism; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2015; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/147245443.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- UN-Habitat. Considerations for a Housing Sector Recovery Framework in Syria; Urban Recovery Framework: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; p. 74. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/09/housing.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- ICOMOS. Guidance on Heritage Impact Assessments for Cultural World Heritage Properties, A Publication of the International Council on Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011; Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/2018-07/icomos_guidance_on_heritage_impact_assessments_for_cultural_world_heritage_properties.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mondiale, F.P. Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA). 2018. Available online: https://www.firenzepatrimoniomondiale.it/en/progetti/heritage-impact-assessment-hia-2/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Maselli, G.; Cucco, P.; Nesticò, A.; Ribera, F. Historical heritage–Multi Criteria Decision Method (H-MCDM) to Prioritize Intervention Strategies for the Adaptive Reuse of Valuable Architectural Assets. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Habashi, S.; Alaa, E.; Al-Behiery, A. A Value-Based HBIM Framework for Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings: A Case Study of Bayt Yakan. J. Eng. Res. 2024, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sustainability Compass and the Global Goals, Compass Education. Available online: https://compasseducation.org/compass-sdgs/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Chapter 1: Intervention Strategies. In Adaptive Reuse of the Built Heritage Concepts and Cases of an Emerging Discipline, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C.; Caracelli, V.J.; Graham, W.F. Toward a Conceptual Framework for Mixed-Method Evaluation Designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 1989, 11, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackie, D. The Failed Promise of Pruitt-Igoe. 2022. Available online: https://unseenstlouis.substack.com/p/the-failed-promise-of-pruitt-igoe (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Six Sigma, Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). All You Need to Know, April, 2024, Six Sigma. Available online: https://www.6sigma.us/six-sigma-in-focus/multi-criteria-decision-analysis-mcda/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mayer, D.G.; Butler, D.G. Statistical validation. Ecol. Model. 1993, 68, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandakji, L. Design Transformations of Residential Architecture in The Syrian Cities Since the Independence Till Now: Case Study Aleppo City. Ph.D Dissertation, Aleppo University, Aleppo, Syria, 2013; p. 4. (In Arabic). [Google Scholar]

- Almuhanna, S. Damascus: City of the Future; Damascus University: Damascus, Syria, 2018; pp. 8–10. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, E.; Sibly, M.; Hakmi, M.; Land, P. Chapter: The Courtyard Houses of Syria. In Courtyard Housing: Past Present, and Future; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2006; pp. 19–305. [Google Scholar]

- Kassab, A.; Al, F. Towards Socially Active Residential Environment in contemporary residential Architecture. Tishreen Univ. J. Res. Sci. Stud. Eng. Sci. Ser. 2013, 35, 1–20. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Syria, Once Upon A Time. The Citizen Bureau, 2015. Available online: https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/newsdetail/index/1/6060/syria-once-upon-a-time (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Samir, A. Urban Development of Damascus 1860–1960. Maaber. Available online: http://www.maaber.org/issue_march17/lookout4.htm (accessed on 23 September 2025). (In Arabic).

- Albadwan, G. Contempory Architecture in Syria Between Theory and Reality-The case of Damascus. AL-Furat J. Res. Sci. Stud. 2010, 2, 242–271. (In Arabic) [Google Scholar]

- Al, M. Neighborhood Guide in Damascus. Imtilak, September 2025. Available online: https://www.imtilak.sy/en/articles/almalki-damascus-neighborhood-guide (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Shahin, I. The Morphology of Prospective Housing. Ph.D Dissertation, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria, 2017; 48p. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzi, M.; The Right to Slums in Defence of “Building Violations” in Syria. Aljumhuriya. 2023. Available online: https://aljumhuriya.net/en/2023/12/01/the-right-to-slums/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Nizam House Restoration, Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme. 2011. Available online: https://www.archnet.org/sites/6417 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ama, S.; Villa, S. The Archive of Modern Architecture in Syria. 2025. Available online: https://www.amasyria.com/en/villa-shoura/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Hala, A. A Residential Villa Model at the Beginning of the Second Half of the Twentieth Century (Villa Chora). Master’s Thesis, Damascus University and Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| ARCHITECTURAL LAYER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAIN CRITERIA | Code | Sub-Criteria | Measurement Method | Scoring Basis |

| A1. COMPACTNESS | A1.1 | Site Coverage Ratio | Percentage of site covered by building footprint (heritage integration) | Optimal range for density and open space |

| A1.2 | Floor Area Ratio (FAR) | Total floor area divided by site area | Achieving desired density without overbuilding | |

| A1.3 | Building Footprint Efficiency | Ratio of usable internal area to external wall area | Minimizing external surface area for heat loss/gain | |

| A1.4 | Verticality/Horizontal Spread | Average building height vs. site area (heritage-sensitive) | Balancing density with urban form and context | |

| A2. SHARED SPACES | A2.1 | Proportion of Shared Area | Percentage of total building area dedicated to shared spaces | Providing adequate communal facilities |

| A2.2 | Accessibility of Shared Spaces | Proximity and ease of access to shared spaces for all residents | Design for inclusivity and convenience | |

| A2.3 | Diversity of Shared Functions | Number and variety of functions supported by shared spaces (e.g., laundry, co-working) | Meeting diverse resident needs | |

| A2.4 | Management and Maintenance Plan | Presence and clarity of a plan for shared space upkeep | Ensuring long-term usability and quality | |

| A3. NEW FORMS OF LIVING | A3.1 | Adaptability for Multi-Generational Living | Design features supporting cohabitation of different age groups | Flexibility for family structures |

| A3.2 | Integration of Live–Work Spaces | Provision for home offices or small business integration | Supporting evolving work patterns | |

| A3.3 | Support for Community Interaction | Design elements encouraging informal social interaction | Fostering a sense of community | |

| A3.4 | Technological Integration Readiness | Infrastructure for smart home technology and future upgrades | Future-proofing the living environment | |

| A4. FLEXIBILITY | A4.1 | Spatial Reconfigurability | Ease and cost of reconfiguring internal layouts (e.g., movable walls, modular units) | Adaptability to changing needs |

| A4.2 | Functional Transformation | Capacity for spaces to serve multiple functions over time | Versatility of design | |

| A4.3 | Structural Modifiability | Design allowing for future vertical or horizontal expansion/contraction | Long-term structural resilience | |

| A4.4 | Material and System Interchangeability | Use of standardized or easily replaceable components | Ease of maintenance and upgrade | |

| A5. IDENTITY AND HERITAGE AUTHENTICITY | A5.1 | Contextual Responsiveness and Heritage Character | Degree to which design reflects and enhances local culture, history, traditions, and unique features of the area | Harmonious integration, and heritage fabric integration |

| A5.2 | Distinctive Architectural Features, Material and Architectural Palette | Presence of unique design elements contributing to a sense of place, use of materials and styles in the local context | Creating memorable and recognizable forms, visual coherence, and heritage integration | |

| A5.3 | Resident Personalization Potential | Opportunities for residents to customize their living spaces | Fostering individual expression | |

| A5.4 | Public Perception and Appreciation | Community feedback and aesthetic appeal to the broader public | Positive social impact | |

| A6. FUNCTIONALITY AND ACCESS | A6.1 | Universal Design Principles | Adherence to principles ensuring accessibility for all users, regardless of ability | Inclusivity |

| A6.2 | Efficiency of Circulation | Clarity and directness of pathways within the building | Ease of movement | |

| A6.3 | Access to Essential Services | Proximity to public transport, shops, schools | Convenience and reduced reliance on private vehicles | |

| A6.4 | Safety Privacy and Security Measures | Implementation of design features and systems for resident safety | Crime prevention and sense of security | |

| URBAN LAYER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAIN CRITERIA | Code | Sub-Criteria | Measurement Method | Scoring Basis |

| U1. OPEN SPACES | U1.1 | Quantity of Open Space | Percentage of sites dedicated to open space | Providing ample green and recreational areas |

| U1.2 | Quality of Open Space | Design, landscaping, and amenities of open spaces | Usability, aesthetics, and ecological value | |

| U1.3 | Accessibility and attraction of Open Space | Ease of access for residents and public | Connectivity and inclusivity | |

| U1.4 | Integration with Urban Fabric | How well open spaces connect with surrounding streets, buildings, and public areas | Seamless urban integration | |

| U2. MIXED USE | U2.1 | Diversity of Functions | Number and variety of residential, commercial, and public uses within the development | Creating vibrant, self-sufficient communities |

| U2.2 | Integration of Uses | How well different uses are blended vertically and horizontally | Minimizing segregation and maximizing synergy | |

| U2.3 | Activity Throughout the Day | Presence of activity across different times of day due to mixed uses | Fostering lively and safe environments | |

| U2.4 | Economic Viability of Mixed Use | Balance of uses supporting economic sustainability and local employment | Contributing to local economy | |

| U3. VARIATION IN CONTEXT | U3.1 | Architectural diversity, and Respect for Urban Grain | How new development relates to the scale, rhythm, and pattern of surrounding buildings | Harmonious integration with heritage fabric |

| U3.2 | Multiple Living Units with Different Densities and Capacities | Implementing various living units for various users and residents | Multi-sized units, with different types and forms | |

| U3.3 | Adaptability and Harmony to Site Topography | How well the design responds to natural contours and features of the site | Sensitive site planning | |

| U3.4 | Multi-generational Living Units | Cohabitation of different age groups, with contemporary lifestyle adaptation | Departure from conventional typologies | |

| U4. DENSIFICATION AND HUMAN SCALE | U4.1 | Density Achieved | Dwelling units per hectare/acre | Optimal density for sustainability without overcrowding |

| U4.2 | Pedestrian Experience/Eye level city | Design of streets, sidewalks, and public spaces to prioritize pedestrian comfort and safety | Walkability and human-centric design | |

| U4.3 | Building Height and Massing | How building heights and massing relate to the human scale and surrounding context | Avoiding overwhelming structures | |

| U4.4 | Permeability and Connectivity | Number of connections and pathways through the site, allowing easy movement | Fostering a permeable urban environment | |

| U5. WALKABILITY | U5.1 | Pedestrian Network Quality | Condition, width, and safety of sidewalks and pedestrian paths | Creating a pleasant walking experience |

| U5.2 | Proximity to Amenities | Average walking distance to daily necessities (e.g., groceries, transit, parks) | Reducing reliance on cars | |

| U5.3 | Streetscape Design | Presence of street trees, benches, lighting, and other elements enhancing pedestrian comfort | Creating inviting public spaces | |

| U5.4 | Traffic-Calming Measures | Implementation of design strategies to reduce vehicle speed and volume | Prioritizing pedestrian safety | |

| U6. NEIGHBORHOOD BENEFITS | U6.1 | Local Economic Contribution | Creation of local jobs, support for small businesses, and increased property values | Positive economic impact |

| U6.2 | Social Cohesion and Interaction | Design elements fostering social interaction and community building | Promoting a strong sense of community | |

| U6.3 | Access to Public Useful Services from the Neighborhood | Proximity and quality of access to schools, healthcare, and emergency services | Supporting community wellbeing | |

| U6.4 | Surrounding Environmental Improvement | Contribution to local environmental quality (e.g., reduced pollution, increased biodiversity) | Ecological benefits | |

| GREEN LAYER | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAIN CRITERIA | Code | Sub-Criteria | Measurement Method | Scoring Basis |

| G1. DAYLIGHT | G1.1 | Daylight Autonomy | Percentage of occupied hours when daylight alone meets illumination requirements | Maximizing natural light use |

| G1.2 | Glare Control | Effectiveness of shading devices and window placement in preventing glare | Visual comfort | |

| G1.3 | View Quality | Access to outdoor views from interior spaces | Connection to nature and visual relief | |

| G1.4 | Uniformity of Daylight and Its Factor | Even distribution of daylight throughout interior spaces | Minimizing dark spots and over-lit areas | |

| G2. WIND AND AIR QUALITY | G2.1 | Natural Ventilation Potential | Design features supporting passive cooling and fresh air circulation | Reducing reliance on mechanical systems |

| G2.2 | Cross-Ventilation Effectiveness | Design allowing for efficient air movement across spaces | Maximizing air changes | |

| G2.3 | Indoor Air Pollutant Control | Use of low-VOC materials and effective filtration systems | Promoting healthy indoor environments | |

| G2.4 | Outdoor Air Quality Impact and Wind Protection | Design strategies to mitigate exposure to outdoor pollutants and improve local air quality | Responsible urban planning | |

| G3. ENERGY EFFICIENCY | G3.1 | Building Envelope Performance | Insulation levels, window U-values, and air tightness | Minimizing heat transfer |

| G3.2 | Renewable Energy Integration | On-site generation of renewable energy (e.g., solar panels, wind turbines) | Reducing reliance on fossil fuels | |

| G3.3 | Efficient HVAC Systems | Use of high-efficiency heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems | Minimizing energy consumption | |

| G3.4 | Smart Energy Management | Implementation of building management systems and smart controls for energy optimization | Intelligent energy use | |

| G4. COSTS AND AFFORDABILITY | G4.1 | Initial Construction Cost | Per square meter cost of construction | Cost-effectiveness and budget adherence |

| G4.2 | Lifecycle Cost Analysis | Long-term operational and maintenance costs | Overall economic sustainability | |

| G4.3 | Affordability for Target Demographics | Housing prices/rents relative to local income levels | Meeting affordability goals | |

| G4.4 | Financial Incentives and Subsidies | Utilization programs or financial aid for sustainable features | Leveraging available support | |

| G5. BIOPHILIA AND BIODIVERSITY | G5.1 | Connection to Nature within Buildings | Integration of natural elements, views, and patterns indoors | Fostering human–nature connection |

| G5.2 | Access to Green Spaces | Proximity and quality of access to parks, gardens, and natural landscapes | Promoting outdoor engagement | |

| G5.3 | Use of Natural Materials | Incorporation of natural, non-toxic, and sustainably sourced materials | Environmental responsibility | |

| G5.4 | Biodiversity Enhancement | Design features supporting local flora and fauna (e.g., green roofs, native planting) | Ecological contribution | |

| G6. SPECIAL SOLUTIONS | G6.1 | Innovative Site Management and Efficient Use of Resources | Implementation of systems for rainwater collection and greywater recycling, and provision for efficient waste segregation, composting, and recycling | Water conservation and waste reduction |

| G6.2 | Innovative Design Systems | Out-of-the-box thinking and new intelligent design systems, and solutions. | Creative problem-solving and innovation | |

| G6.3 | Resilience to Climate Change | Design strategies to withstand extreme weather events and future climate impacts | Long-term adaptability | |

| G6.4 | Innovative Technologies/Materials | Adoption of cutting-edge solutions for sustainability and performance | Pioneering sustainable practices | |

| Name: | 1. Beit Nizam (Traditional Period) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Figures: Source: [45] |  |  |  | ||||||

| Location: | Old City of Damascus, Suq al-Maydani district, Damascus, Syria | ||||||||

| Architect: | N/A | ||||||||

| Date: | 18th–19th century—1760 | ||||||||

| Typology: | Traditional Courtyard House | ||||||||

| Area: | Floor area: | 950 m2 | Plot area: | 1400 m2 | |||||

| Number of units: | 1 Unit—10 rooms (can be shared and rented by room) | ||||||||

| Variation in units: | Traditional Single Family | ||||||||

| Density: | FAR | ≈0.68 | UPH | 9 | low | ||||

| Height: | ≈10 m | ||||||||

| Context: | Tight urban fabric within the historic Suq al-Maydani, adjacent to narrow market alleys. | ||||||||

| Materials | Local limestone and basalt masonry, carved cedar wood “Mashrabiya” screens, gypsum plaster, traditional tile flooring. | ||||||||

| Description: | One of the most luxurious Damascene palaces in the Shaghour district of Damascus, in the Minaret of Sham neighborhood, this is named after the Nizam family, the last to inhabit and restore it in the early twentieth century. In the mid-nineteenth century, the house served as the headquarters of the British consul in Syria. Beit Nizam embodies the classic Damascene courtyard house, with inward-facing rooms organized around a shaded courtyard that moderates microclimate and fosters privacy. Thick masonry walls and “Mashrabiya” regulate light and airflow, while carved wood and tile details reflect local craftsmanship. Its adaptable layout allows for discreet integration of modern services (HVAC, lighting) without altering heritage fabric. Central courtyard with fountain basin, raised iwan seating, mashrabiya for privacy and ventilation, solid exterior walls facing narrow streets. | ||||||||

| Affordability: | Built through traditions, self-built, affordable in that moment of time, high maintenance. | ||||||||

| AUG framework radar chart analyzation [author]: |  | ||||||||

| Score in points: | 210/360 [A 70/120—U 60/120—G 80/120] | ||||||||

| Results: | From the AUG framework evaluation, Beit Nizam scored 210 out of 360 points (58%), indicating a moderate performance baseline. The house exhibits strong identity, spatial quality, and environmental performance. However, it falls short in several areas critical for meeting contemporary resilience standards. Its rigid traditional layout limits adaptability to contemporary living patterns, particularly regarding flexible workspaces, multi-generational households, and technological infrastructure. Despite these limitations, Beit Nizam demonstrates that heritage architecture can achieve strong environmental performance through climate-responsive design principles developed over centuries. The courtyard typology, passive cooling strategies, and natural ventilation systems remain highly effective in Damascus’s climatic context. However, the house performs poorly on contemporary urban housing criteria, including density, mixed-use programming, and social contribution. Its low-density, single-family occupancy model is incompatible with current urban housing demands, highlighting the challenge of adapting palatial heritage structures to meet modern residential needs. In conclusion, Beit Nizam exemplifies both the strengths and limitations of traditional Damascene palatial architecture, offering valuable insights for balancing heritage authenticity with the functional and urban demands of modern adaptive reuse. The evaluation reveals that while traditional typologies excel in environmental and cultural dimensions, significant interventions are required to address urban density and contemporary functional flexibility. | ||||||||

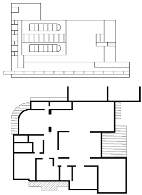

| Name: | 2. Villa Shoura (Transitional Period) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Figures: [Author] |  source: [46] |  |  source: [41] | ||||||

| Location: | Abu Rummaneh, Damascus, Syria | ||||||||

| Architect: | Nazir Shoura, Mounib Dardari | ||||||||

| Date: | 1945 | ||||||||

| Typology: | Urban Residential Villa | ||||||||

| Area: | Floor area: | 600 m2 | Plot area: | 1200 m2 | |||||

| Number of units: | 3 | ||||||||

| Variation in units: | 50–150 m2 studios, multibedroom, and town houses | ||||||||

| Density: | FAR | ≈0.5 | UPH | 8 | low | ||||

| Height: | ≈10 m | ||||||||

| Context: | Urban Core, low rise neighborhood | ||||||||

| Materials | The facades are notably devoid of ornamentation, but all of the original iron window grills are painted crimson, matching the facades which were covered in crimson-colored concrete spray, with accents in a lighter-colored plaster. However, due to the peeling and cracking of the plaster over time, some brickwork in the northern façade got exposed. | ||||||||

| Description: | The building mass is simple: an extruded rectangle with rounded corners penetrated by the stairwell in the middle of the main facade. The building has only three floors: a basement, a ground floor, and a first floor. It can be accessed through the main entrance on the northeastern side. Both the ground and first floors accommodate single apartments that span the entire floor with almost identical plans. Each apartment is equipped with two entrances: a main one that opens onto a lobby that leads to the office, the first living room, and the dining room; and a secondary entrance that opens up to a more private area of the house which includes the bedrooms, along with the service area that contains the bathroom and the kitchen. Additionally, each apartment features two mezzanines, 2.1 m high, the first located above the service area that can be accessed through a staircase in the lobby, and the second located above a portion of the office and its balcony. The building was frequently connected with the “Bauhaus” architectural style, owing to its distinguishing features and high-quality craftsmanship, which included some of the furniture and ironwork in the apartments (such as the internal stair rail), all created by the architect himself. | ||||||||

| Affordability: | A family built and owned the private apartment for higher income when built. | ||||||||

| AUG framework radar chart analyzation [author]: |  | ||||||||

| Score in points: | 150/360 [A 55/120—U 50/120—G 45/120] | ||||||||

| Results: | Villa Shoura achieving 150/360 (42%) score positions it as a transitional bridge between typologies. It achieves moderate architectural refinement and urban integration yet reveals that mid-century modernism—without environmental upgrade and minimal mixed-use programming—cannot meet contemporary resilience standards. It represents a design-conscious modernist approach that prioritizes craftsmanship and space over pure efficiency and density. It achieves moderate architectural performance through space organization and cultural attention to domestic life at that era—but still falls short of contemporary standards for flexibility compactness and shared amenities. It shows that good design models do not automatically create urban vitality. The building demonstrates that architectural refinement alone cannot overcome limited programmatic diversity and community contribution. It severely lacks both internal shared courtyards and shared-roof open space and minimal ground-floor programming that could activate street-level neighborhood interaction. Inadequate insulation, single-glazed windows, and an uninsulated roof adds to poor thermal performance, with limited ventilation control. Mid-century modernism proves insufficient for contemporary demands. The concrete construction with limited lifecycle planning or material reuse consideration adds to the high embodied carbon with minimal green infrastructure. The building’s Bauhaus with local authenticity provides cultural assets for heritage reactivation, making it uniquely suited to become a demonstration project for how modernist heritage can contribute to vibrant, sustainable urban futures when thoughtfully adapted. | ||||||||

| Name: | 3. Tijara Residential Towers (Modern Period) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Figures: [Author] |  source [41] source [41] | |||||||

| Location: | Mmdouh Zarkeli, Mhd Reyad Bastata | |||||||

| Architect: | Nazir Shoura, Mounib Dardari | |||||||

| Date: | 1974 | |||||||

| Typology: | Urban Residential Villa | |||||||

| Area: | Floor area: | ≈7000 m2 | Plot area: | 1200 m2 | ||||

| Number of units: | 44 | |||||||

| Variation in units: | 50–150 m2 studios, multibedroom, and town houses | |||||||

| Density: | FAR | ≈1 | UPH | 44 | Moderate | |||

| Height: | 12 floors ≈ 40 m | |||||||

| Context: | Urban-core, high-rise neighborhood, around the Salam Park in Tijara, far from the shopping streets. Its characteristics are represented by typical late 20th century residential blocks, including buildings from the 1960s that reflect the landmarks of the era and form the identity of the area belonging to the modernist period in the West. The current function is purely residential, with few services compared to other areas. | |||||||

| Materials | The building was constructed with soviet construction techniques and was predominantly built using concrete systems combined with Hourdi blocks and reinforced concrete frames. The exterior walls were typically covered with dark brown or beige cement-based plaster (often called “roughcast”). The plaster frequently deteriorated due to poor application, inadequate weather protection, and minimal maintenance, leading to widespread staining, cracking, and water infiltration | |||||||

| Description: | A detached, 11-story, residential tower. The apartments are uniform in size and designed in a shape known as a whirlwind. These towers achieve dense development, with all residents enjoying good views of the gardens and all spaces well-lit but not receiving equal daylight. The facility connects existing spaces within the urban fabric and harmoniously integrates them. Its aim was to provide a quantitative solution to densification within the urban center and a reform of high-density urban environments. The lack of flexible layout made residents adjust the exterior facades to a certain extent, by closing off balconies to increase private space. A high number of apartments are available at reasonable prices, with good natural light and ventilation. | |||||||

| Affordability: | Used to be an affordable solution before the Syrian crisis. | |||||||

| AUG framework radar chart analyzation [author]: |  | |||||||

| Score in points: | 125/360 [A 45/120—U 35/120—G 45/120] | |||||||

| Results: | This tower exemplifies the failure of socialist-influenced modernist housing design by achieving 125/360 points (35%), representing critical underperformance across all dimensions. It achieves its narrow objective of providing affordable housing density but fails dramatically on adaptability, community contribution, and environmental sustainability by prioritizing density and construction efficiency over human adaptability and livable space quality. The widespread unauthorized balcony enclosures are evidence that residents found the design inadequate for their needs. Rigid, inflexible layout as the standardized plan cannot accommodate diverse household needs—single occupants, multi-generational families, home offices, or flexible workspaces. It has monotonous, repetitive architecture with minimal spatial variation, utilitarian aesthetic lacking cultural identity or contextual integration, and in the urban layer, this model severely lacks mixed-use programming with minimal neighborhood benefits, and low social vibrancy. One of the positive attributes is the extended ground floor public open space. Weak contextual integration: modern tower form contrasts sharply with historic urban fabric without meaningful dialog. Despite its 11-story height, the tower achieves a floor area ratio (FAR) of only 1.0, indicating underutilization of site potential and inefficient density optimization compared to contemporary urban standards (typical mid-rise mixed-use development targets FAR 3–4). The 29% urban score reveals the fundamental inadequacy of tower-only development models for creating vibrant urban neighborhoods. Modern housing towers often become isolated enclaves rather than integrated community assets. The absence of active renewable systems, insulation, and water management makes the tower unsustainable for contemporary climate demands. | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomajian, H.; Gyergyák, J. Adaptive Urban Housing in Historic Landscapes: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Resilient Heritage in Damascus. Land 2025, 14, 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112217

Tomajian H, Gyergyák J. Adaptive Urban Housing in Historic Landscapes: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Resilient Heritage in Damascus. Land. 2025; 14(11):2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112217

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomajian, Haik, and János Gyergyák. 2025. "Adaptive Urban Housing in Historic Landscapes: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Resilient Heritage in Damascus" Land 14, no. 11: 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112217

APA StyleTomajian, H., & Gyergyák, J. (2025). Adaptive Urban Housing in Historic Landscapes: A Multi-Criteria Framework for Resilient Heritage in Damascus. Land, 14(11), 2217. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112217