Linking Ecosystem Services, Cultural Identity, and Subjective Wellbeing in an Emergent Cultural Landscape of the Galápagos Islands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

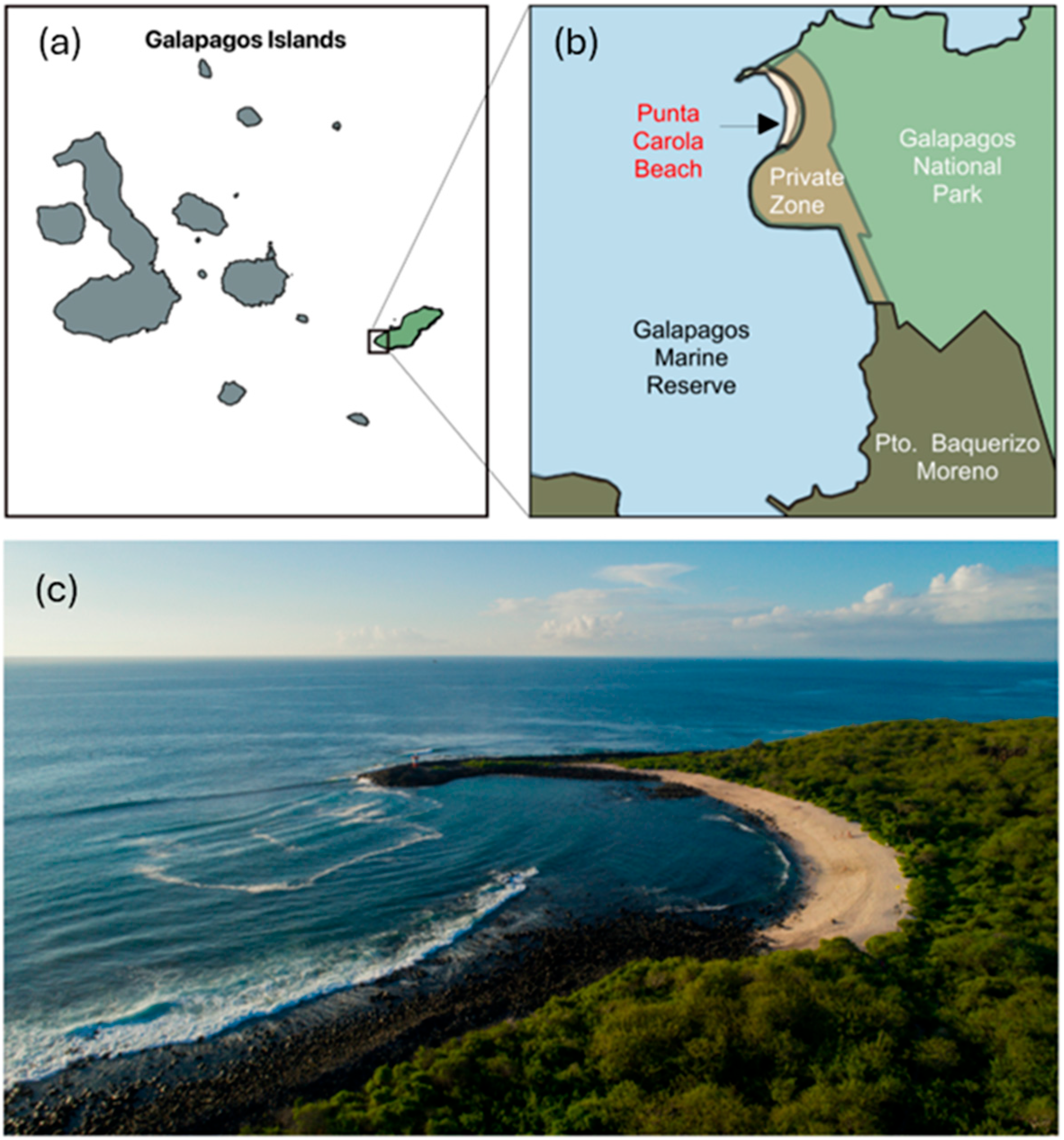

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Methods

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

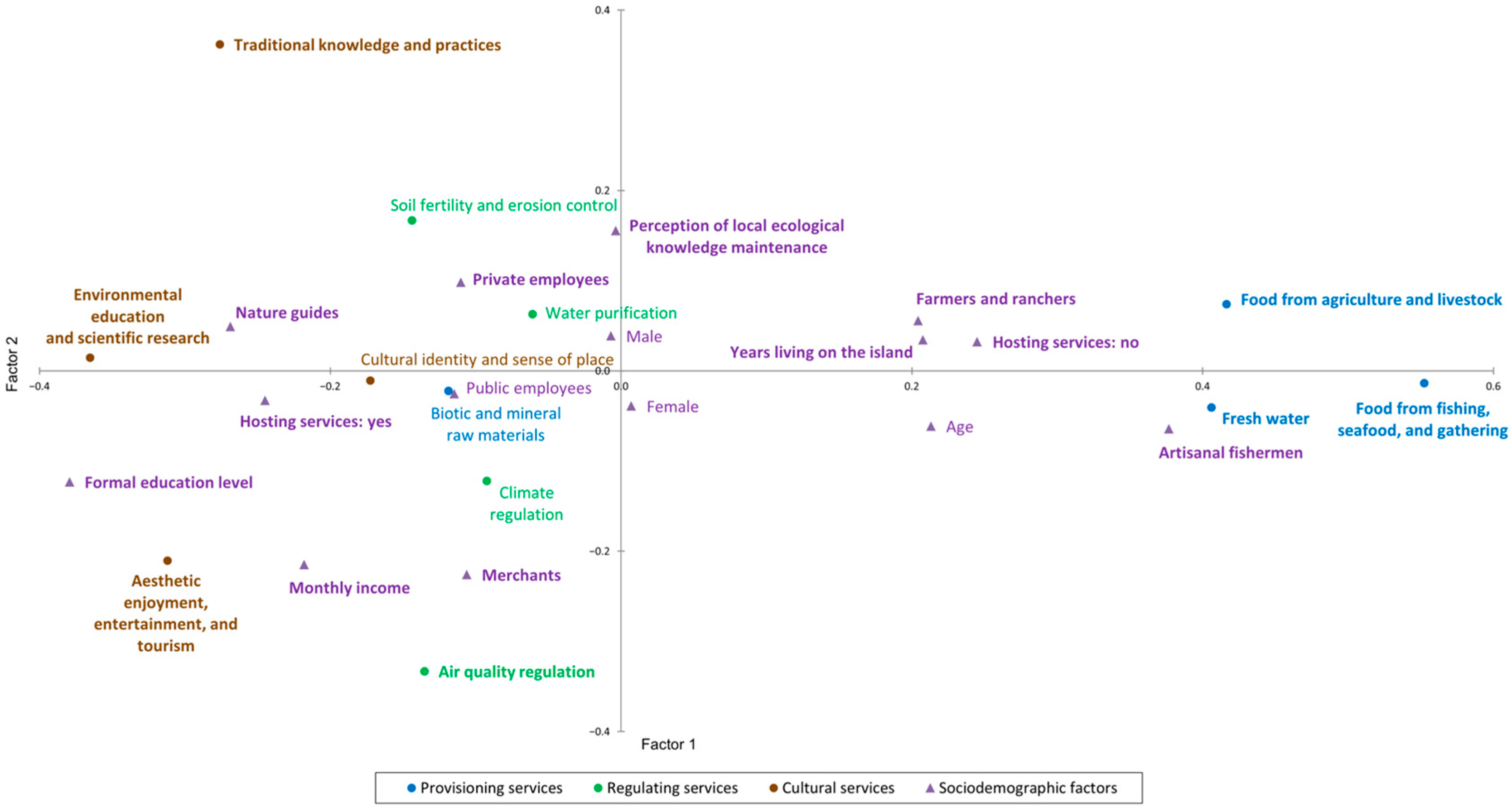

3.1. Factors Influencing Life Satisfaction

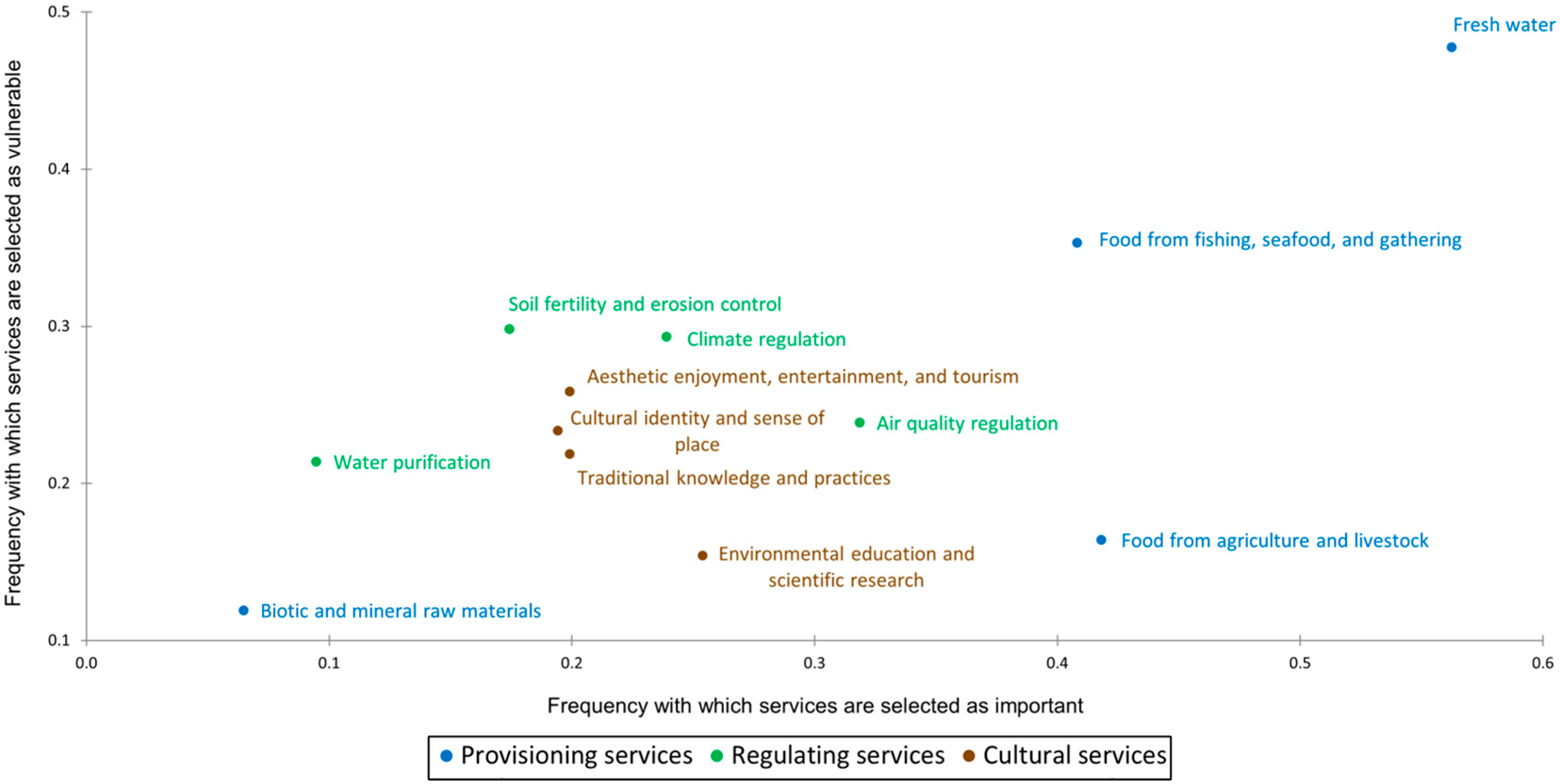

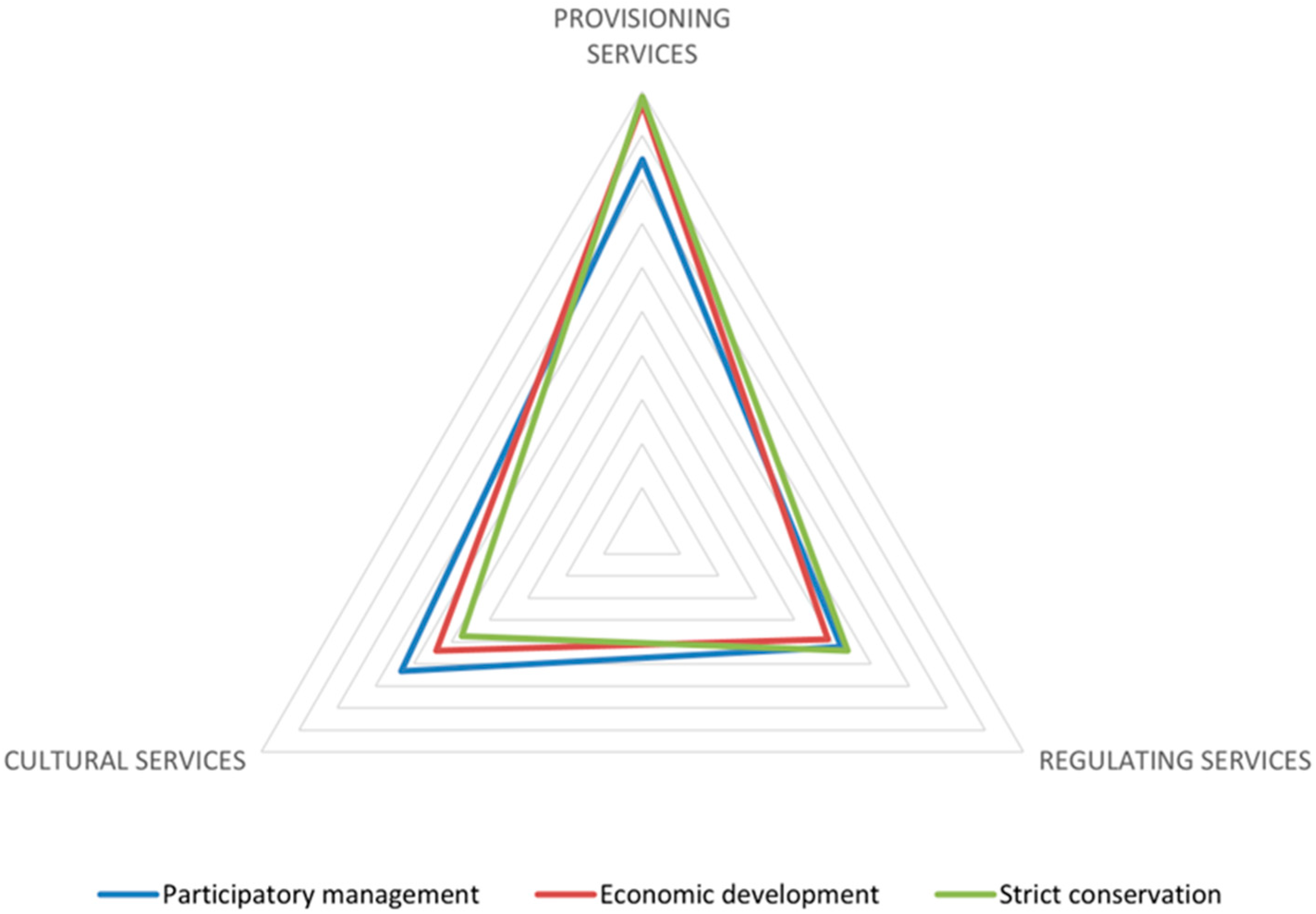

3.2. Perception of Ecosystem Services

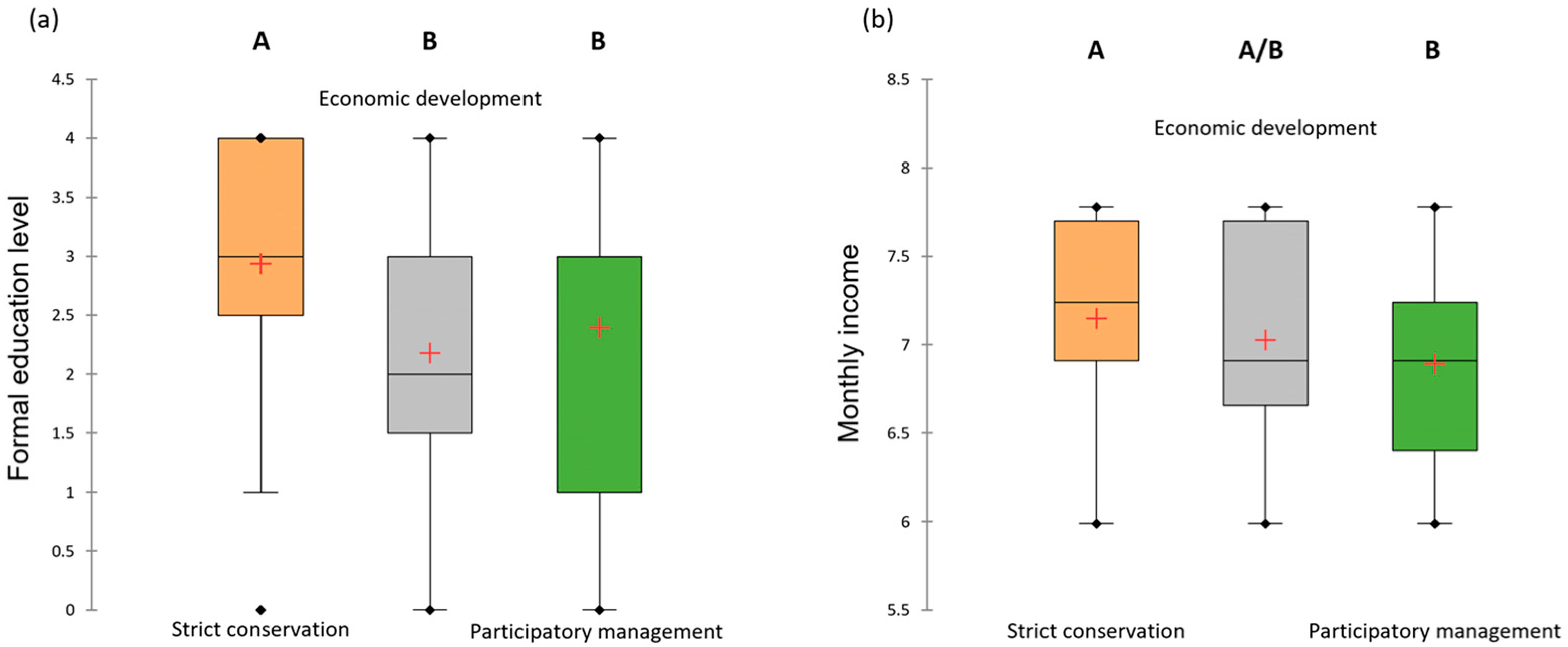

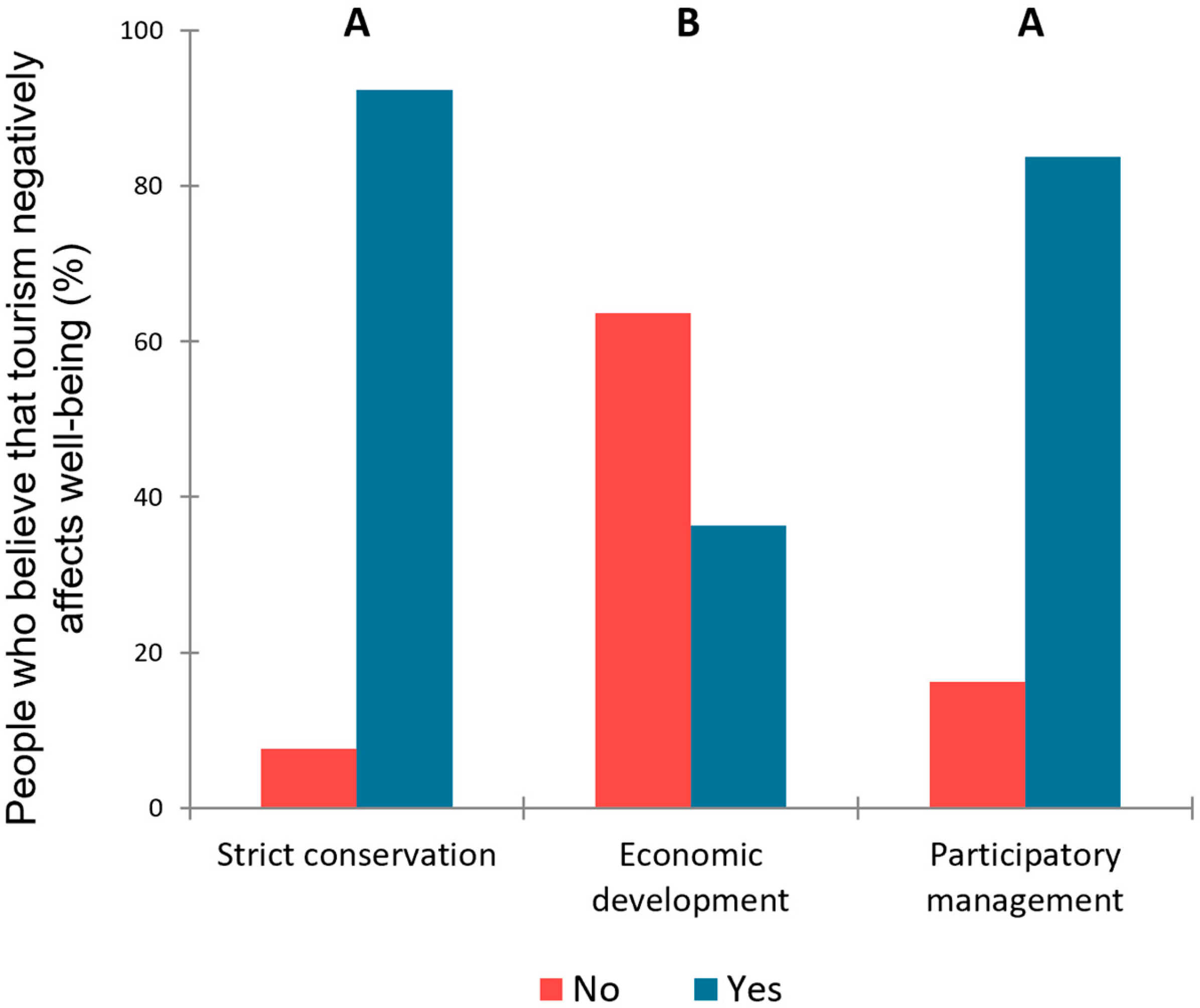

3.3. Management and Conservation Strategies for Punta Carola

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Do you live in Galápagos? Yes/No

- How many years have you been living on the island?

- Where were you born?

- How old are you?

- What is your sex? Female/Male

- Which is the highest education level that you have reached

- ▪

- Illiterate

- ▪

- Basic studies/Primary studies

- ▪

- Secondary studies

- ▪

- Technologies/Undergraduate studies

- ▪

- Higher education

- Currently, what is your professional status or your main source of income?

- ▪

- Artisanal fishing

- ▪

- Agriculture/Livestock raising

- ▪

- Public employee

- ▪

- Private employee.

- ▪

- Business and market

- ▪

- Nature guide

- In which of these intervals does your monthly income fall?

- ▪

- Less than $400

- ▪

- Between $400–$800

- ▪

- Between $800–$1200

- ▪

- Between $1200–$1600

- ▪

- Between $2000–$2400

- ▪

- More than $2400

- Do you or your family provide any accommodation facilities (hotel, hostel, etc.) for tourists? Yes/No

- Do you believe that the increase in tourism activities and the presence of a hotel complex in the Punta Carola area could negatively affect your well-being and that of your family? Yes/No

- On a scale from 0 to 5, how much do you think nature contributes to your quality of life?

- Which of the following 12 benefits provided by nature would you say are the 3 most important for your well-being and quality of life?

- ▪

- Food from agriculture and livestock

- ▪

- Food from fishing, seafood, and gathering

- ▪

- Fresh water

- ▪

- Biotic and mineral raw materials

- ▪

- Climate regulation

- ▪

- Air quality regulation

- ▪

- Water purification

- ▪

- Soil fertility and erosion control

- ▪

- Environmental education and scientific research

- ▪

- Aesthetic enjoyment, recreation, and tourism

- ▪

- Traditional knowledge and practices

- ▪

- Cultural identity and sense of place

- And which of these would you say are the 3 that are in more danger of disappearing or degrading in the following years (the most vulnerable ones)?

- Do you think ancestral stories and knowledge about nature from your parents and grandparents are still present in your life?

- ▪

- Yes, completely

- ▪

- Yes, although some has been lost

- ▪

- Yes, although much has been lost

- ▪

- No

- On a scale from 0 to 5, how would you rate your satisfaction with your life?

- Which of the following management strategies would you prefer for Punta Carola?

- ▪

- The local community and institutions work together for the sustainability of Punta Carola. They develop a comprehensive participatory management plan for the area that respects the ecosystem’s dynamics and biodiversity. Sustainable local tourism is promoted, and the community is educated about the importance of conserving nature.

- ▪

- Urban development is allowed in Punta Carola. Economic gains from construction and tourism increase, but ecological degradation and damage to biodiversity also rise.

- ▪

- Punta Carola is declared part of the National System of Protected Areas of Ecuador. Construction is prohibited, access is limited, and tourism is controlled. Regulation by the State preserves biodiversity and the ecosystem’s ecological integrity.

References

- López-Santiago, C.A.; Aguado, M.; González Nóvoa, J.A.; Bidegain, I. Evaluación sociocultural del paisaje, una necesidad para la planificación y gestión sostenible de los sistemas socioecológicos. In Claves para la Gestión Humana de los Sistemas Naturales; Cerda, C.J., Palacios-Agundez, J.M., Eds.; Ocho Libros Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2019; pp. 105–137. Available online: https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/720046 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C.; Colding, J. (Eds.) Linking Social and Ecological Systems: Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Raymond, C. The relationship between place attachment and landscape values: Toward mapping place attachment. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, J.M.L. El Ecuador y los Paisajes Culturales en la Gestión del Territorio. Cad. Naui 2023, 12, 148–174. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.A.; Montes, C.; Rodríguez, J.; Tapia, W. Rethinking the Galapagos Islands as a complex social-ecological system: Implications for conservation and management. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. Landscape and meaning: Context for a global discourse on cultural landscapes values. In Managing Cultural Landscapes; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mughal, M.A.Z. Landscape, space, and time: Navigating the cultural landscape through socio-spatial and socio-temporal organization in rural Pakistan. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 6175–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, K. Landscape geographies: Interdisciplinary landscape research and a new framework to apply landscape as method. Landsc. Res. 2025, 50, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, R.Z. Protecting rural cultural landscapes: Finding value in the countryside. Landsc. J. 1983, 2, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reke, A.; Ruskule, A.; Lees, L.; Kotta, J.; Veidemane, K.; Kõivupuu, A.; Herkül, K.; Aps, R.; Jänes, H.; Barboza, F.R. Linking coastal cultural ecosystem services to human well-being and leisure preferences: Insights from the Baltic Sea region. Ecosyst. People 2025, 21, 2530103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Fargione, J.; Chapin, F.S., III; Tilman, D. Biodiversity loss threatens human well-being. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbano, D.V.; Meredith, T.C. Effects of tourism growth in a UNESCO World Heritage Site: Resource-based livelihood diversification in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1270–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, A.; Jiménez-Uzcátegui, G.; Bosker, T. The effects of climate change on wildlife biodiversity of the Galapagos Islands. Clim. Change Ecol. 2021, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.S.; Porter, A.; Muñoz-Pérez, J.P.; Alarcón-Ruales, D.; Galloway, T.S.; Godley, B.J.; Santillo, D.; Vagg, J.; Lewis, C. Plastic contamination of a Galapagos Island (Ecuador) and the relative risks to native marine species. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensted-Smith, R. (Ed.) A Biodiversity Vision for the Galapagos Islands; Charles Darwin Foundation and World Wildlife Fund: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2002; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Robert-Bensted-Smith/publication/358445842_A_biodiversity_vision_for_the_Galapagos_Islands_Charles_Darwin_Foundation_and_World_Wildlife_Fund_Ed_R_Bensted-Smith/links/6202eda0c2d279745e7629ec/A-biodiversity-vision-for-the-Galapagos-Islands-Charles-Darwin-Foundation-and-World-Wildlife-Fund-Ed-R-Bensted-Smith.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Schmidt, K.; Walz, A.; Martín-López, B.; Sachse, L. Testing socio-cultural valuation methods of ecosystem services to explain land use preferences. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Santiago, C.A.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Martín-López, B.; Plieninger, T.; González Martín, E.; González, J.A. Using visual stimuli to explore the social perceptions of ecosystem services in cultural landscapes: The case of transhumance in Mediterranean Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; García-Llorente, M.; Palomo, I.; Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Amo, D.G.D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Palacios-Agundez, I.; Willaarts, B.; et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidegain, I.; Cerda, C.; Catalán, E.; Tironi, A.; López-Santiago, C. Social preferences for ecosystem services in a biodiversity hotspot in South America. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0215715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, E.; García-Llorente, M.; Pataki, G.; Martín-López, B.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Non-monetary techniques for the valuation of ecosystem services. In OpenNESS Ecosystem Services Reference Book; Potschin, M., Jax, K., Eds.; EC FP7 Grant Agreement no. 308428; 2016; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://connectingnature.oppla.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/sp-non-monetary-valuation.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Aguado, M.; González, J.A.; Bellott, K.S.; López-Santiago, C.; Montes, C. Exploring subjective well-being and ecosystem services perception along a rural–urban gradient in the high Andes of Ecuador. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 34, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; Dijks, S.; Oteros-Rozas, E.; Bieling, C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy 2013, 33, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menatti, L.; Da Rocha, A.C. Landscape and health: Connecting psychology, aesthetics, and philosophy through the concept of affordance. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C. The role of multi-functionality in social preferences toward semi-arid rural landscapes: An ecosystem service approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 19–20, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaček, K.; Tran, D.; Landau, A.; Sanz, T.; Thiri, M.A.; Navas, G.; Del Bene, D.; Liu, J.; Walter, M.; Lopez, A.; et al. “We are protectors, not protestors”: Global impacts of extractivism on human–nature bonds. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1789–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, D.M. Factors influencing the island-mass effect of the Galápagos Archipelago. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkinger, J.; Gordillo, L.; Montero-Serra, I.; Murillo, J.C.; Guevara, N.; Hirschfeld, M.; Fietz, K.; Rubianes, F.; Dan, M. Urban life of Galapagos sea lions (Zalophus wollebaeki) on San Cristobal Island, Ecuador: Colony trends and threats. J. Sea Res. 2015, 105, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikelski, M.; Nelson, K. Conservation of Galápagos marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). Iguana 2004, 11, 190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). Perfil Territorial. Provincia Galápagos, Cantón San Cristóbal: Resultados del Censo de Población y Vivienda 2022 [Tablero Interactivo]; INEC: Quito, Ecuador, 2022; Available online: https://cubos.inec.gob.ec/AppCensoEcuador/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Lucero, R.; Mera, M. Impacto del Turismo en el Desarrollo Económico Sostenible de la Isla San Cristóbal, Galápagos. Maest. Soc. 2024, 21, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo, J.G.; Kendrick, A.W. Isla San Cristóbal. Not. Galápagos 1989, 48, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Torres, G.F.; Benítez, F.L.; Rueda, D.; Sevilla, C.; Mena, C.F. A methodology for mapping native and invasive vegetation coverage in archipelagos: An example from the Galápagos Islands. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2018, 42, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mons, S.; Rodríguez, N.L. The complex socio-ecological landscape in Latin America: Transdisciplinary knowledge production to address diversity. Eur. Rev. Lat. Am. Caribb. Stud. 2023, 115, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M.; Murphy, S.A. Happiness is in our nature: Exploring nature relatedness as a contributor to subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. Nature relatedness and subjective well-being. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- MacKerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness is greater in natural environments. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.E.; Rojo Negrete, I.A.; Torres-Gómez, M.; Alfonso, A.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F. Social-ecological Systems and Human Well-Being. In Social-ecological Systems of Latin America: Complexities and Challenges; Delgado, L., Marín, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Seikh, S.; Pandey, R. Nexus between indigenous ecological knowledge and ecosystem services: A socio-ecological analysis for sustainable ecosystem management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 61561–61578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, K.; Chaterjee, D. Perception of subjective well-being of the Lodha Tribe in West Bengal. Contemp. Voice Dalit 2025, 17, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: A call to action. BioScience 2002, 52, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Babigumira, R.; Pyhälä, A.; Wunder, S.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Angelsen, A. Subjective wellbeing and income: Empirical patterns in the rural developing world. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarik, Z. The Relationship Between Education and Happiness: Findings from the North Central and Northeast Regions; North Central Regional Center for Rural Development: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Grau-Satorras, M.; Kalla, J.; Demps, K.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; García, C.; Reyes-García, V. Contribution of natural and economic capital to subjective well-being: Empirical evidence from a small-scale society in Kodagu (Karnataka), India. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 127, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarter, J.; Gavin, M.C. Perceptions of the value of traditional ecological knowledge to formal school curricula: Opportunities and challenges from Malekula Island, Vanuatu. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2011, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Mingorría, S.; Reyes-García, V.; Calvet, L.; Montes, C. Traditional ecological knowledge trends in the transition to a market economy: Empirical study in the Doñana natural areas. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Corbera, E.; Reyes-García, V. Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Crumley, C.L.; Svedin, U. Biocultural refugia: Combating the erosion of diversity in landscapes of food production. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Tang, H.; Lu, Y. Exploring subjective well-being and ecosystem services perception in the agro-pastoral ecotone of northern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. Social capital, income and subjective well-being: Evidence in rural China. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, C.J.; Howell, R.T.; Schwabe, K.A. Does wealth enhance life satisfaction for people who are materially deprived? Exploring the association among the Orang Asli of Peninsular Malaysia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 76, 499–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masferrer-Dodas, E.; Rico-Garcia, L.; Huanca, T.; TAPS Bolivian Study Team; Reyes-García, V. Consumption of market goods and wellbeing in small-scale societies: An empirical test among the Tsimane’ in the Bolivian Amazon. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 84, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Xie, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, D.; Wu, H.; Li, S. Perceived Importance and Bundles of Ecosystem Services in the Yangtze River Middle Reaches Megalopolis, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 739876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellowe, K.E.; Leslie, H.M. Ecosystem service lens reveals diverse community values of small-scale fisheries. Ambio 2021, 50, 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Shaw, M.R.; Cameron, D.R.; Underwood, E.C.; Daily, G.C. Conservation planning for ecosystem services. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, T.; Fischer, J.; Câmpeanu, C.; Milcu, A.I.; Hanspach, J.; Fazey, I. The importance of ecosystem services for rural inhabitants in a changing cultural landscape in Romania. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temesgen, H.; Wu, W. Farmers’ value assessment of sociocultural and ecological ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, M.; Riebl, R.; Haensel, M.; Schmitt, T.M.; Steinbauer, M.J.; Landwehr, T.; Fricke, U.; Redlich, S.; Koellner, T. Perceptions of ecosystem services: Comparing socio-cultural and environmental influences. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.P.; Bastos, R.P. Perceiving the invisible: Formal education affects the perception of ecosystem services provided by native areas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 40, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Arzuaga, I.; Madariaga, I.; Onaindia, M. Perception, demand and user contribution to ecosystem services in the Bilbao Metropolitan Greenbelt. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 129, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorda-Capdevila, D.; Rodríguez-Labajos, B. An ecosystem service approach to understand conflicts on river flows: Local views on the Ter River (Catalonia). Sustain. Sci. 2015, 10, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.J.; Vaughn, C.C.; Julian, J.P.; García-Llorente, M. Social demand for ecosystem services and implications for watershed management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2016, 52, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.E.; Zizumbo, V.L.; Chaisatit, N. La gobernanza ambiental: El estudio del capital social en las Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Territorios 2019, 40, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, G. Ante las metas 2030 del convenio de biodiversidad. ¿Es la gobernanza de las áreas protegidas una alternativa a la gobernanza política tradicional? Rev. Univ. Geogr. 2021, 30, 111–144. [Google Scholar]

- Munévar-Quintero, C.; Valencia-Hernández, J.G.; Hernández-Gómez, N.; Aguirre-Fajardo, A.M.; Ramírez-Ríos, M. Gobernanza participativa en la conformación del Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas de la ecorregión Eje Cafetero, Colombia. Jurídicas 2023, 20, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Martín-López, B.; López-Santiago, C.; Montes, C. Participatory scenario planning for protected areas management under the ecosystem services framework: The Doñana social-ecological system in southwestern Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Montes, C.; Martin-Lopez, B.; González, J.A.; Garcia-Llorente, M.; Alcorlo, P.; Mora, M.R.G. Incorporating the social–ecological approach in protected areas in the Anthropocene. BioScience 2014, 64, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos (DPNG). Plan Institucional DPNG 2021–2025; Dirección del Parque Nacional Galápagos: Puerto Ayora, Ecuador, 2021; Available online: https://www.galapagos.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Plan_institucional_dpng_2021-2025-final.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Cortés-Capano, G.; Hanley, N.; Sheremet, O.; Hausmann, A.; Toivonen, T.; Garibotto-Carton, G.; Soutullo, A.; Di Minin, E. Assessing landowners’ preferences to inform voluntary private land conservation: The role of non-monetary incentives. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.L.; Wang, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Sriarkarin, S. Evaluating the public’s preferences toward sustainable planning under climate and land use change in forest parks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, R.K.; Hamilton, R.J. A cultural landscape approach to community-based conservation in Solomon Islands. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, T.; van der Horst, D.; Schleyer, C.; Bieling, C. Sustaining ecosystem services in cultural landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarlucea, L. Patrimonio cultural y turismo en una ciudad patrimonio mundial: Encuentros (y desencuentros) en Colonia del Sacramento, Uruguay. In Gestión del Patrimonio: Paisajes Culturales y Participación Ciudadana; Galceran, C., Giordano, F., Eds.; Comisión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación, Intendencia de Río Negro, Universidad CLAEH: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018; pp. 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Djabarouti, J.; Ren, Y. Cultural convergence in heritage landscape conservation: A comparative study of Chinese and English traditions. Arts Commun. 2024, 2, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba-Hernández, L. Participación ciudadana para la conservación de los paisajes culturales de la UNESCO en América Latina: Crítica descolonial para el tránsito entre la teoría y la práctica. In Gestión del Patrimonio: Paisajes Culturales y Participación Ciudadana; Galceran, C., Giordano, F., Eds.; Comisión del Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación, Intendencia de Río Negro, Universidad CLAEH: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

| Explanatory Variables | Coefficient | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.102 | 0.416 | 0.678 |

| Nature contribution to wellbeing | 0.595 | 11.029 | <0.0001 |

| Perception of LEK maintenance | 0.055 | 4.554 | <0.0001 |

| Monthly income | 0.082 | 3.002 | 0.003 |

| Education level | −0.041 | −2.898 | 0.004 |

| R2 | 0.446 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.425 | ||

| AIC | −711.840 | ||

| F | 22.161 | ||

| P | <0.0001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quijozaca, J.A.; Aguado, M.; González, J.A. Linking Ecosystem Services, Cultural Identity, and Subjective Wellbeing in an Emergent Cultural Landscape of the Galápagos Islands. Land 2025, 14, 2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112208

Quijozaca JA, Aguado M, González JA. Linking Ecosystem Services, Cultural Identity, and Subjective Wellbeing in an Emergent Cultural Landscape of the Galápagos Islands. Land. 2025; 14(11):2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112208

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuijozaca, Jenny A., Mateo Aguado, and José A. González. 2025. "Linking Ecosystem Services, Cultural Identity, and Subjective Wellbeing in an Emergent Cultural Landscape of the Galápagos Islands" Land 14, no. 11: 2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112208

APA StyleQuijozaca, J. A., Aguado, M., & González, J. A. (2025). Linking Ecosystem Services, Cultural Identity, and Subjective Wellbeing in an Emergent Cultural Landscape of the Galápagos Islands. Land, 14(11), 2208. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112208