Carbon Emission Patterns and Carbon Balance Zoning of Land Use in Xiamen City Based on Urban Functional Zoning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Research Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Date Source

- (1)

- Administrative boundary data: The national-scale administrative division vector data of China, which serves as the geographic base map, along with the specific municipal and district boundaries of Xiamen City, were both obtained from the China Administrative Division Database (2024 Edition), publicly available from the National Platform for Common Geospatial Information Services (Tianditu) at https://cloudcenter.tianditu.gov.cn/administrativeDivision (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- (2)

- All economic, demographic, and energy consumption per unit of , and data are derived from the Statistical Yearbook of Xiamen Special Economic Zone [32].

- (3)

- The NPP/VIIRS nighttime light data, with a spatial resolution of 500 m, can be freely downloaded from the website of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States [34].

- (4)

- The land use type data, with a spatial resolution of 30 m, is obtained from the team of Professor Huang Xin at Wuhan University (Figure 2). It is derived from satellite imagery through calculated input features and trained classification samples. These data are openly and freely available at https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/13/3907/2021/essd-13-3907-2021-discussion.html (accessed on 10 October 2024) [35].

- (5)

- The Xiamen POI data, known for their timeliness and high spatial accuracy [36], can be freely obtained from the AutoNavi (Amap) platform (https://lbs.amap.com/, accessed on 10 October 2024, accessed on 8 October 2024).

- (6)

- The Xiamen road network data, which includes roads of different grades, is available for free download from the open-source website OpenStreetMap (OSM) (https://openmaptiles.org/languages/zh/, accessed on 8 October 2024).

- (7)

- Remote sensing imagery data of Xiamen can be acquired through the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. Summer and winter remote sensing images of Xiamen were selected, filtered for cloud cover, and processed for cloud removal. Median compositing was then applied to generate quarterly representative images with a spatial resolution of 10 m × 10 m (Figure 3).

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Calculation Method of Land Use Carbon Emissions

- (1)

- Direct Carbon Emission Estimation [38]

- (2)

- Indirect Carbon Emission Estimation [48]

2.3.2. Spatialization Method for

- (1)

- Selection and Calculation of Nighttime Light Indices

- (2)

- Error Correction

2.3.3. Methodology for Functional Zoning

- (1)

- Functional Zone Classification

- (2)

- Delineation Method for Urban Functional Zones

2.3.4. Spatial Autocorrelation

- (1)

- Global Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

- (2)

- Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

2.3.5. Ecological Support Coefficient of Carbon Emissions (ESC)

3. Foundational Results and Preliminary Analysis

3.1. Spatialization Modeling

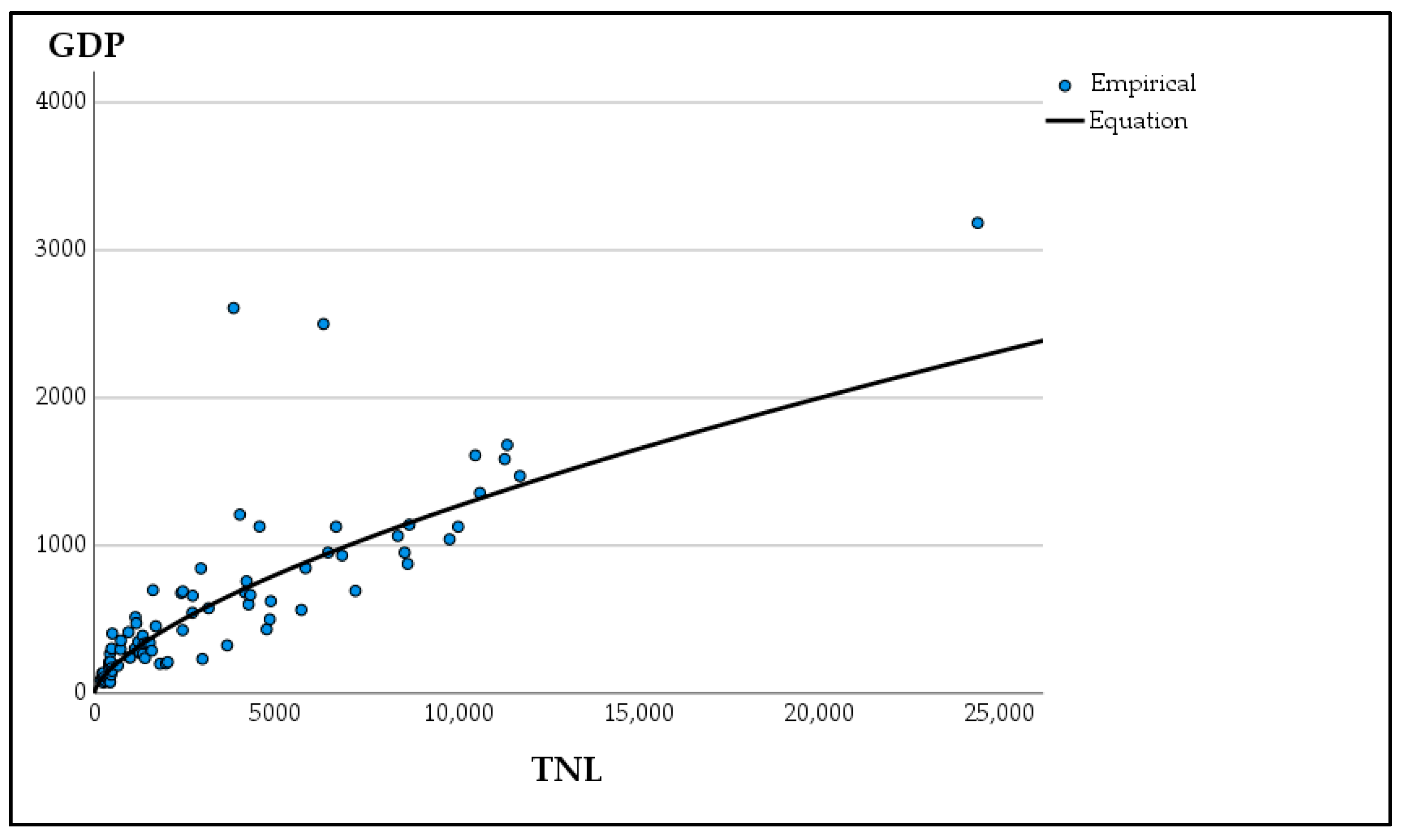

3.1.1. Selection of Spatialization Modeling Approaches

- (1)

- Temporal Series Modeling

- (2)

- Spatial Series Modeling

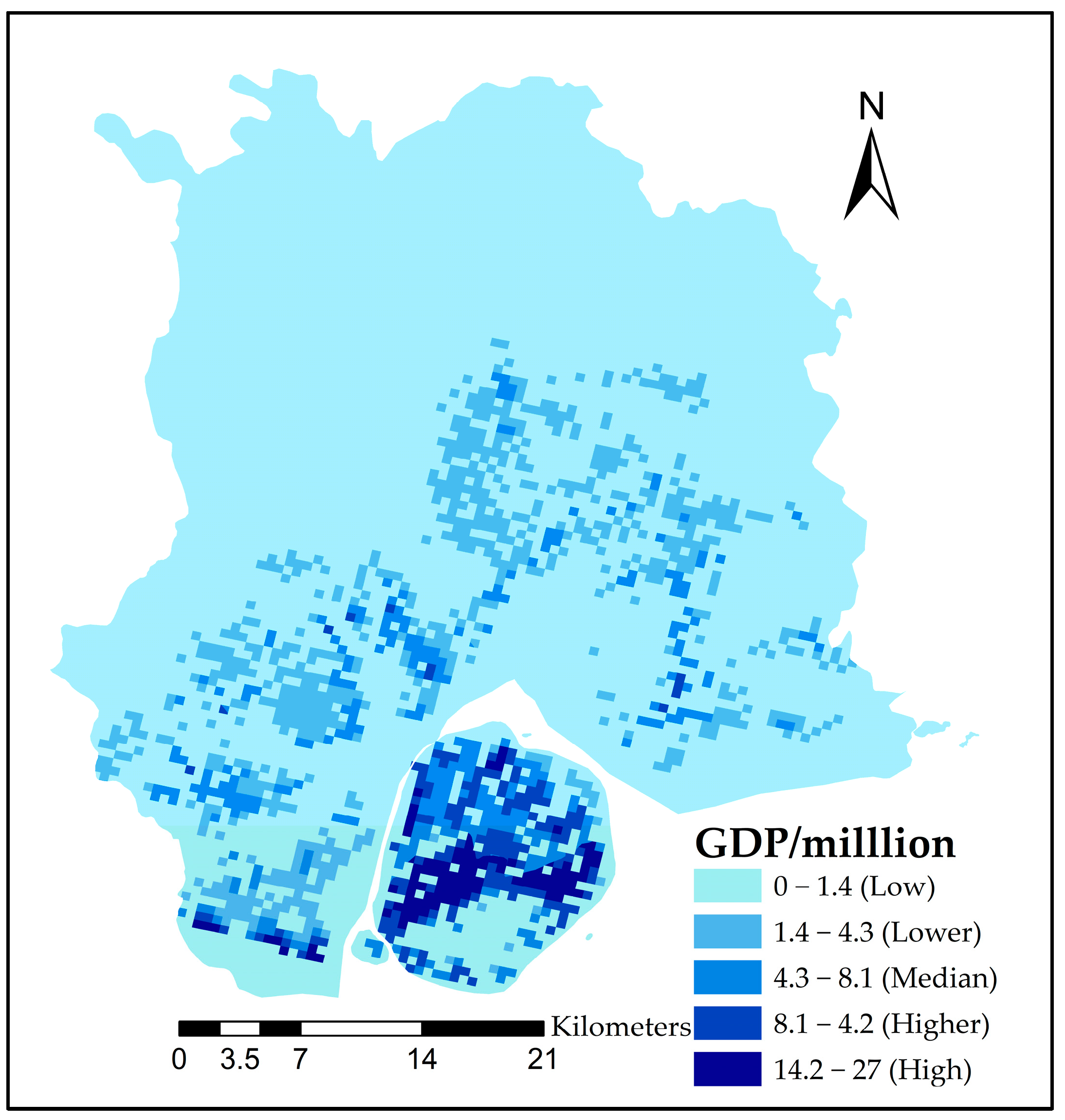

3.1.2. Spatialization Results

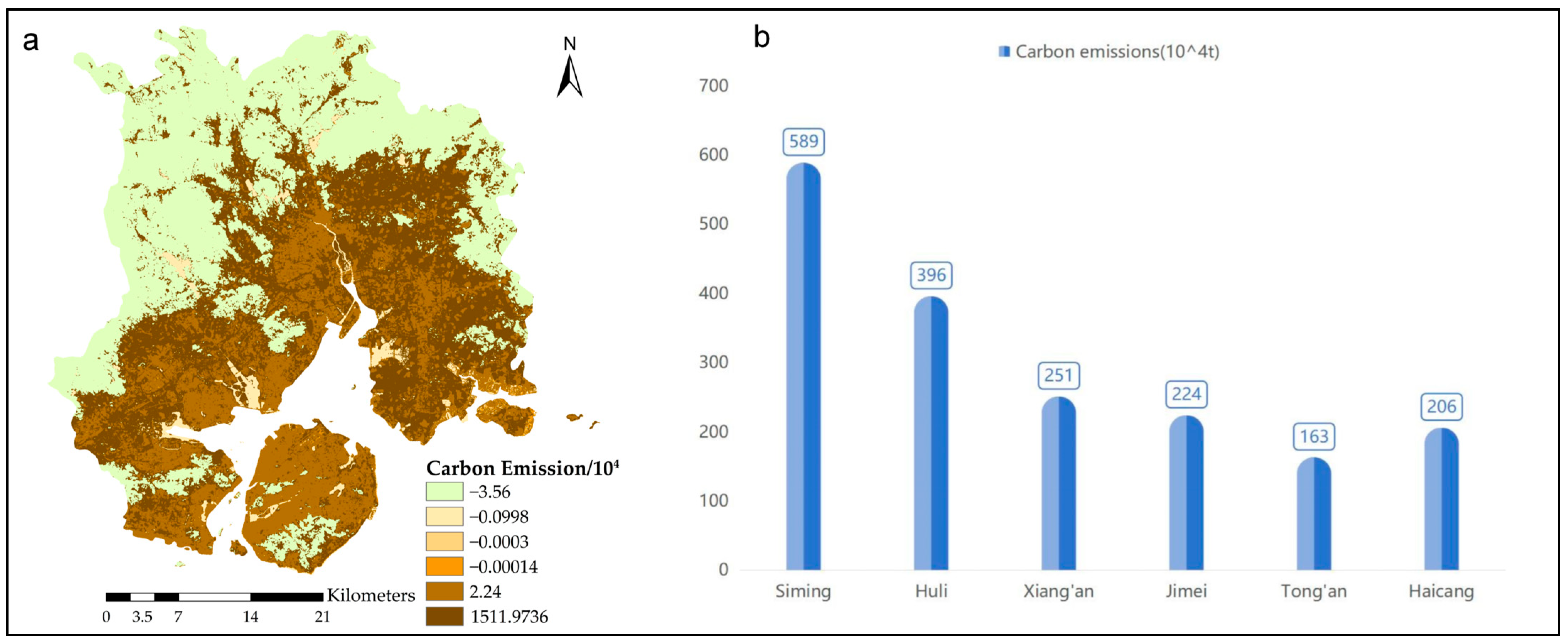

3.2. Carbon Emissions Results

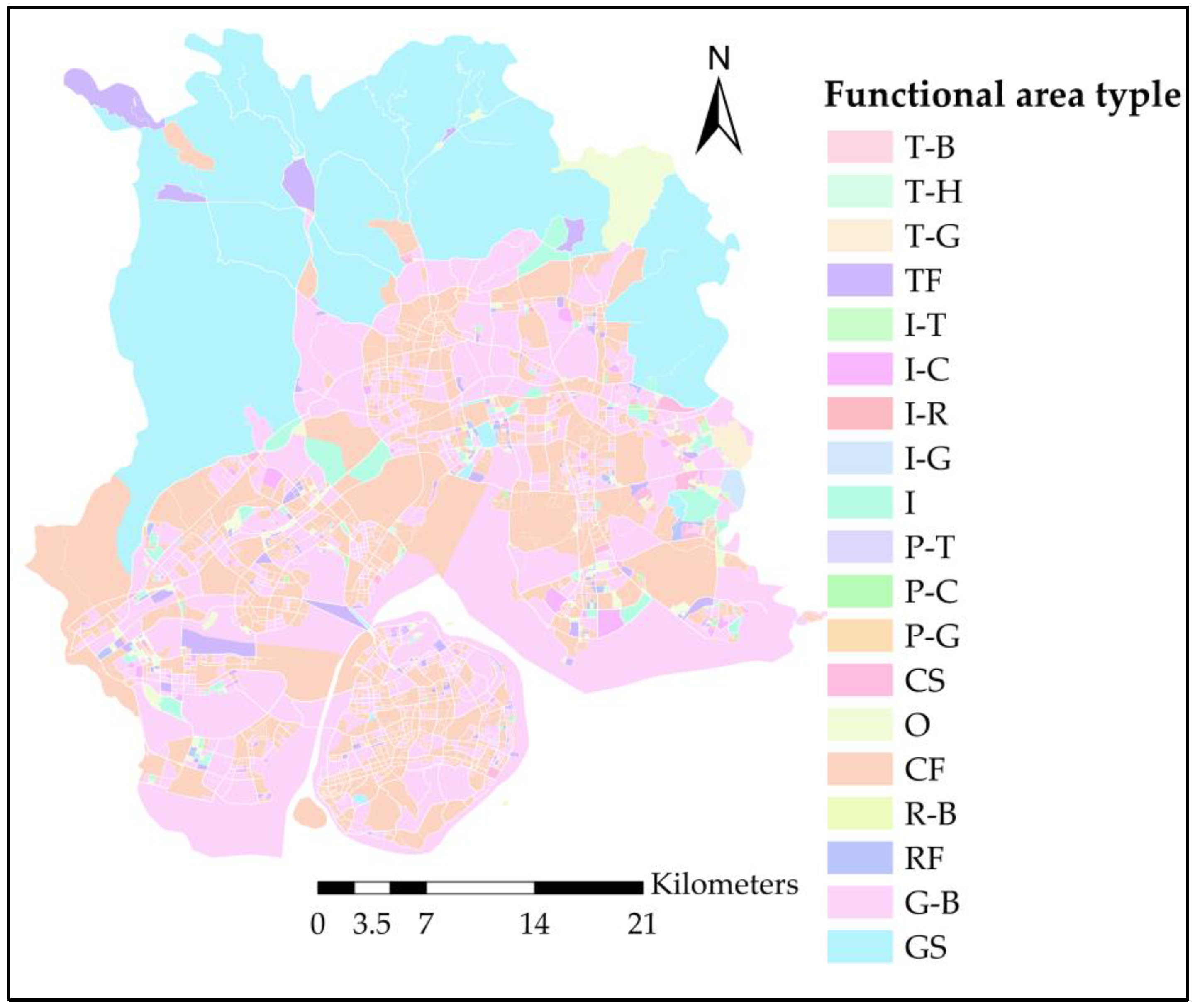

3.3. Functional Zone Classification Results

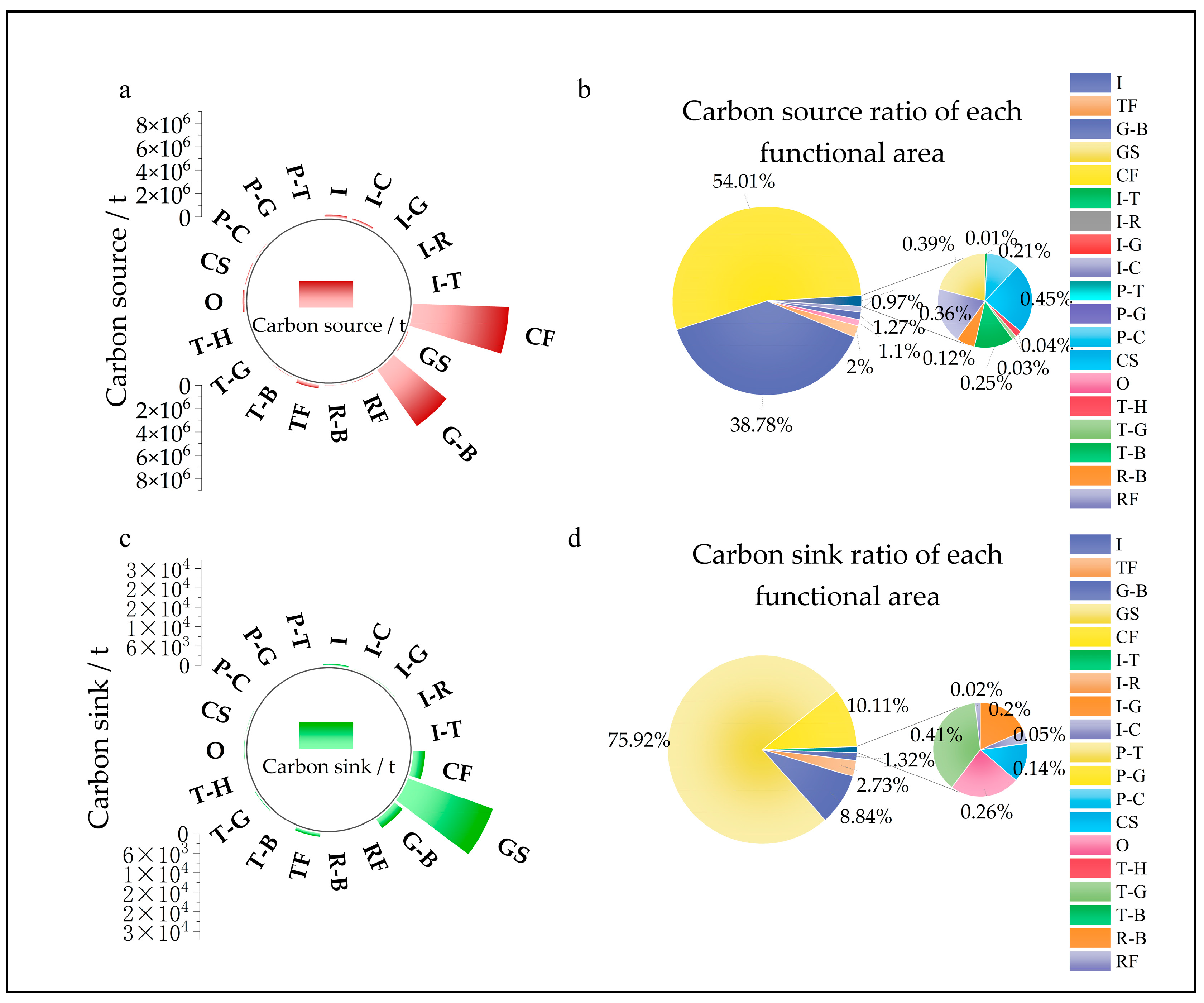

4. Spatial Pattern Characteristics of Carbon Sources and Sinks in Xiamen City

4.1. Overall Carbon Emission Patterns Based on Administrative and Functional Zoning

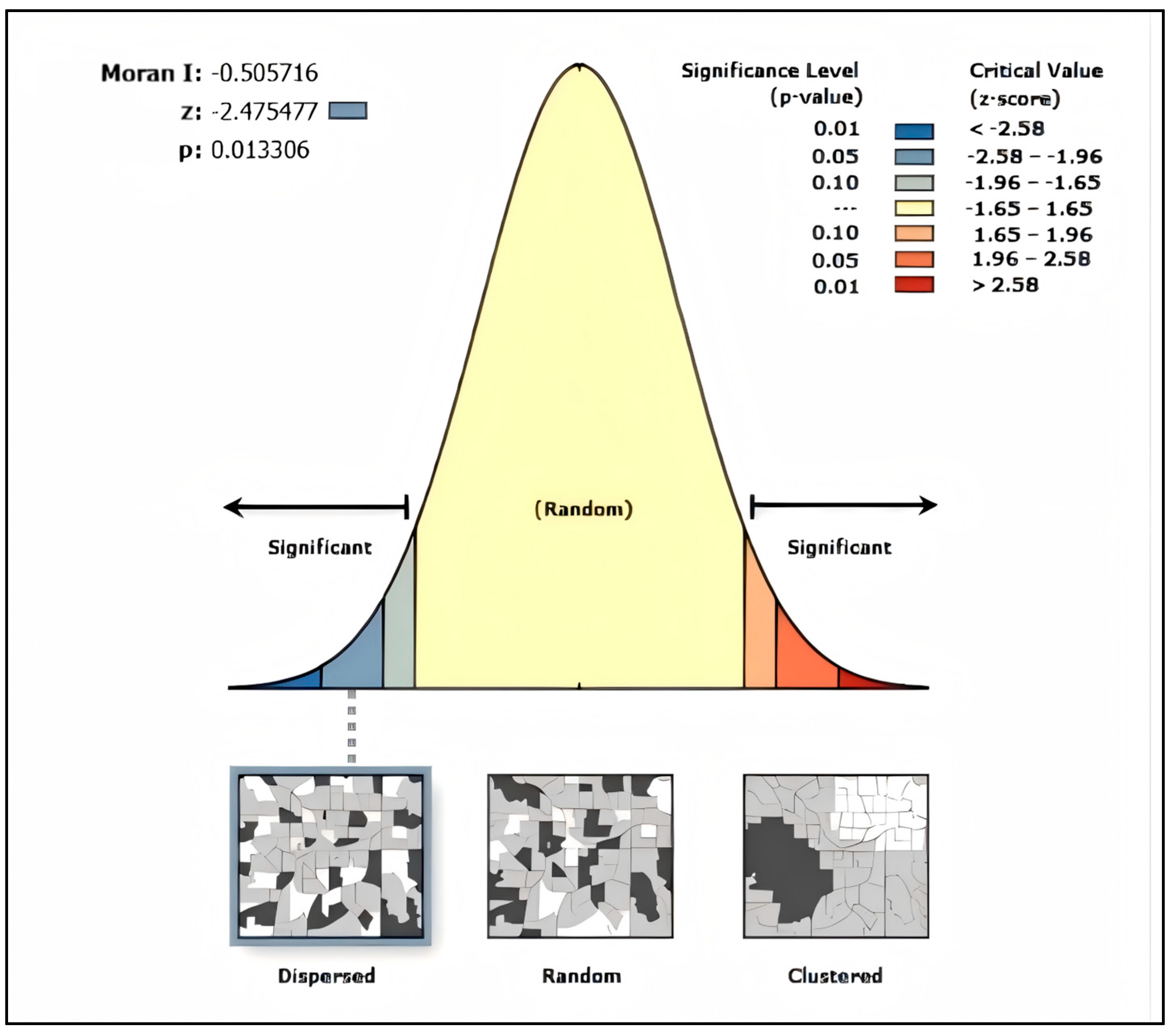

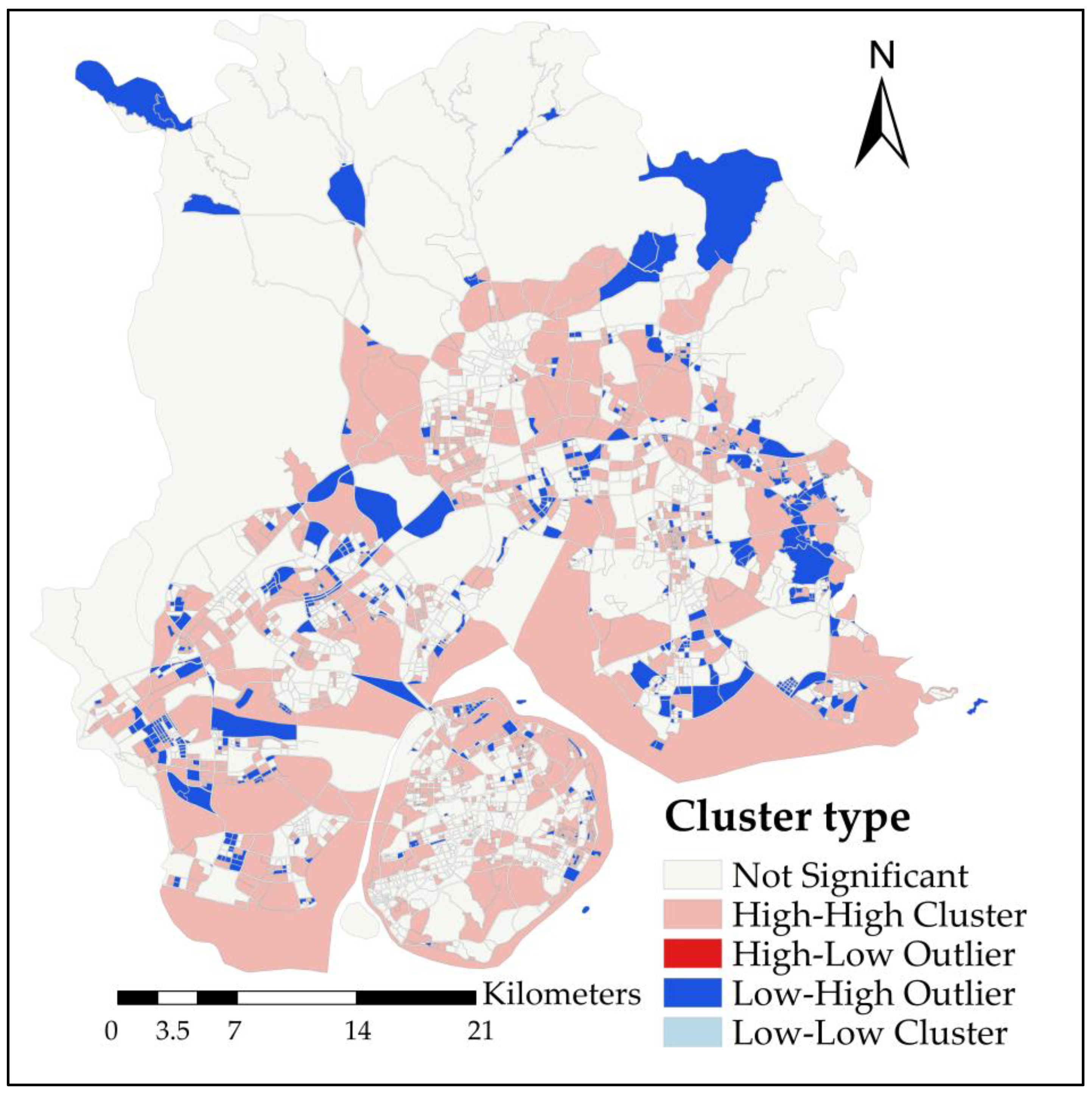

4.2. Spatial Correlation Pattern of Carbon Emissions in Xiamen City

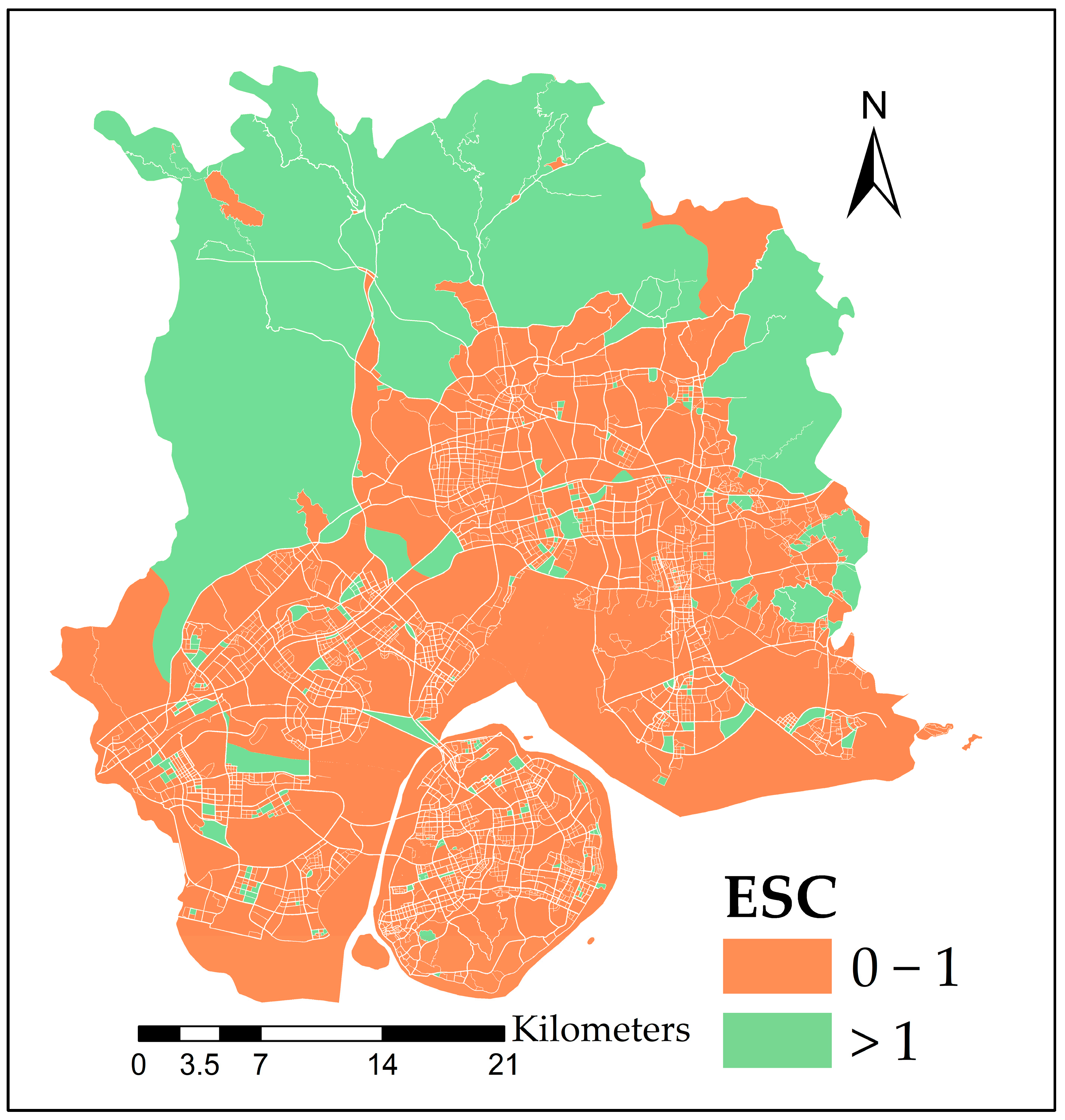

4.3. Carbon Ecological Support Coefficient Pattern of Xiamen’s Functional Zones

5. Carbon Balance Zoning and Low-Carbon Development Suggestions for Xiamen City

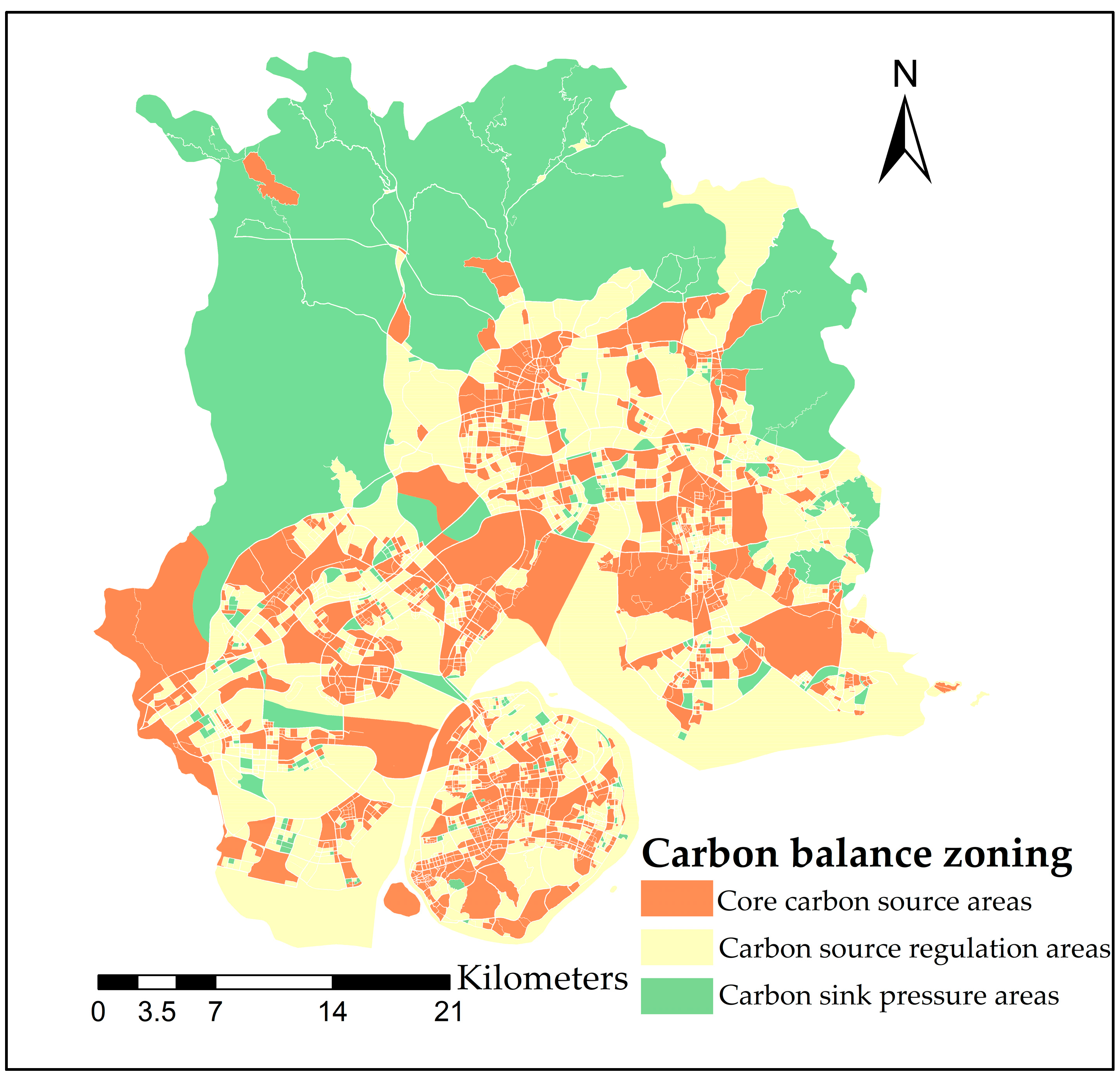

5.1. Demarcation of Carbon Balance Zones

5.1.1. Basis for Carbon Balance Zone Demarcation

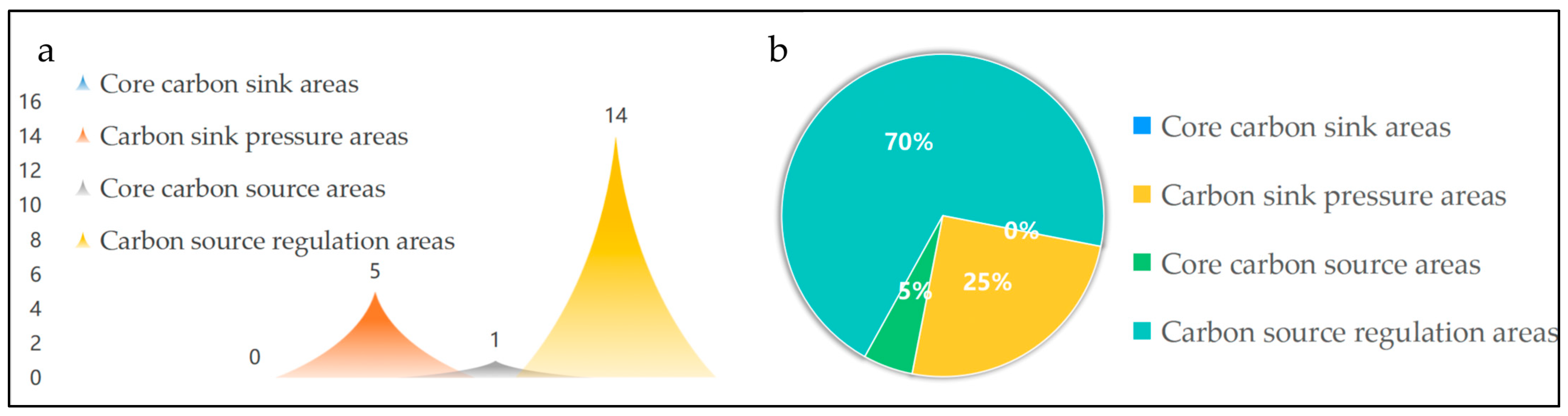

5.1.2. Results of Carbon Balance Zone Demarcation

5.2. Characteristics of Carbon Balance Zones and Low-Carbon Development Recommendations

- (1)

- Core Carbon Sink Zones

- (2)

- Carbon Sink Pressure Zones

- (3)

- Carbon Source Regulation Zones

- (4)

- Core Carbon Source Zones

6. Discussion

6.1. Spatial Heterogeneity of Carbon Sources and Sinks

6.2. Impact of Urban Functional Zoning on Carbon Balance

6.3. Methodological Considerations for Urban Carbon Emission Calculation

7. Conclusions

7.1. Principal Findings

- (1)

- Spatial Pattern: Carbon emissions in Xiamen show pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with higher concentrations in the south and lower in the north, while carbon sinks exhibit the opposite tendency. Total carbon emissions reached 15.3 million tonnes, far exceeding the carbon absorption of 36,900 tonnes, reflecting a severe carbon imbalance.

- (2)

- Role of Functional Zoning: Urban functional zoning significantly influences the carbon balance. Commercial, industrial, and transportation zones serve as core carbon source spaces, while green space functional zones contribute 73% of total carbon sequestration. Mixed functional zones show relatively lower emission intensity, suggesting the carbon-reducing potential of mixed land use.

- (3)

- Methodological Approach: Using as a proxy for energy consumption and combining it with nighttime light data, this study effectively spatialized carbon emissions at the micro-scale. This approach offers a practical solution to the scarcity of fine-grained energy statistics.

- (4)

- Spatial Correlation and Zoning: Spatial autocorrelation analysis reveals a significant negative spatial autocorrelation in carbon emissions, presenting a heterogeneous and fragmented pattern rather than clustered distributions. Carbon balance zoning indicates that carbon source regulation zones dominate (70% of the area), with fragmented governance posing challenges to systematic emission reduction.

7.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- (1)

- Incomplete carbon accounting framework: The current system, based primarily on energy consumption, does not fully align with the internationally recognized IPCC inventory, as it omits non-energy emission sources such as industrial processes and waste treatment. While this simplification supports the core objective of spatial simulation, it may result in an underestimation of emissions in specific industrial clusters, affecting the comprehensiveness of the total emission assessment. Future studies should develop a more integrated accounting framework that incorporates energy activities, industrial processes, and waste management to establish a more complete urban carbon emission inventory.

- (2)

- Uncertainty from base geographic data precision: The reliance on crowdsourced data (e.g., OpenStreetMap) to delineate analytical units introduces heterogeneity in geometric accuracy and attribute completeness, particularly in newly developed or remote areas, which may affect the precision of functional zone boundaries. Moreover, residual errors from coordinate system registration of multi-source data are non-negligible in micro-scale analysis. Subsequent research could strengthen the data foundation by incorporating higher-precision base geographic data (e.g., official survey data) or employing cross-validation with multi-source datasets to enhance the accuracy of micro-scale carbon accounting.

- (3)

- Insufficient localization of key model parameters: Although the emission coefficients used in this study were drawn from the existing literature with consideration of regional applicability, they do not fully capture subtle influences from local factors such as Xiamen’s energy structure, industrial technology efficiency, and natural conditions on carbon flux rates. Therefore, developing a more region-specific emission factor library through field monitoring, material balance calculations, or cross validation with local energy statistics represents an essential direction for improving the accuracy of model simulations in future research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, R.Q.; Zhang, S.; Huang, X.J.; Qin, Y.C.; Liu, Y.; Ding, M.; Jiao, S. Spatial variation of carbon budget and carbon balance zoning of Central Plains Economic Region at county-level. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2014, 69, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Gong, W. Effects of land use and cover change (LUCC) on terrestrial carbon stocks in China between 2000 and 2018. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Raza, S.A.; Ozturk, I.; Afshan, S. The dynamic relationship of renewable and nonrenewable energy consumption with carbon emission: A global study with the application of heterogeneous panel estimations. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Shao, Q. Decomposing the decoupling of CO2 emissions and economic growth in China’s iron and steel industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Bi, J.; Yan, J. State-of-the-art in low carbon community. Int. J. Energy A Clean Environ. 2018, 19, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Carbon emission efficiency and low-carbon optimization in Shanxi Province under “Dual Carbon” background. Energies 2022, 15, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Global carbon budget. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4811–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachelet, D.; Neilson, R.P.; Lenihan, J.M.; Drapek, R.J. Climate change effects on vegetation distribution and carbon budget in the United States. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 164–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enting, I.G.; Rayner, P.J.; Ciais, P. Carbon cycle uncertainty in regional carbon cycle assessment and processes (RECCAP). Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 2889–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, P.; Scholes, R.J.; Boyle, E.E.A.; Canadell, J.; Canfield, D.; Elser, J.; Gruber, N.; Hibbard, K.; Högberg, P.; Linder, S.; et al. The global carbon cycle: A test of our knowledge of earth as a system. Science 2000, 290, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Ye, C.S.; Xiao, W.; Peng, J.C. Spatial correlation and carbon compensation zoning of land use carbon budget in the middle reaches of Yangtze River. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2024, 33, 1474–1488. Available online: https://yangtzebasin.whlib.ac.cn/CN/10.11870/cjlyzyyhj202407009 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Lan, H.; Xia, F.; Xie, Y. A new framework for making carbon compensation standards considering regional differences at different scales in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Gao, Z.; Tian, L.; Fu, M. What drives urban carbon emission efficiency?–Spatial analysis based on nighttime light data. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Meng, X.; Liang, H.; Cao, Z.; Dong, L.; Huang, C. An improved nightlight-based method for modeling urban CO2 emissions. Environ. Model. Softw. 2018, 107, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Liang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Qu, S.; Xu, M.; Yang, Z. China high resolution emission database (CHRED) with point emission sources, gridded emission data, and supplementary socioeconomic data. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ma, H.; Ozturk, I.; Ahmad, M.I. Examining the carbon emissions and climate impacts on main agricultural crops production and land use: Updated evidence from Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 868–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; López Gutiérrez, J.S.; Esteban, M.D.; Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Garay-Rondero, C.L. A framework for accurate carbon footprint calculation in seaports: Methodology proposal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Guo, D.; Ji, J.; Zuo, H.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Y. How to calculate CO2 emissions and emission reduction effectiveness of underground logistics systems using the life cycle assessment. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 145, 104832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, F.; Liu, W.; Twumasi-Ankrah, M.J. Analysis of urban carbon balance based on land use dynamics in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, L.; Piketty, T. Carbon and Inequality: From Kyoto to Paris Trends in the Global Inequality of Carbon Emissions (1998–2013) & Prospects for An Equitable Adaptation Fund World Inequality Lab. 2015. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02655266 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Marbuah, G.; Gren, M.; Tirkaso, W.T. Social capital, economic development and carbon emissions: Empirical evidence from counties in Sweden. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, R.A.; Castanho, A. Annual emissions of carbon from land use, land-use change, and forestry 1850–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2022, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z. Carbon dioxide emission driving factors analysis and policy implications of Chinese cities: Combining geographically weighted regression with two-step cluster. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 684, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Zhai, C.X.; Liu, C.Y.; Chen, Z.Y. Analysis of spatiotemporal differences and influencing factors of land use carbon emissions in Ningxia. Huan Jing Ke Xue Huanjing Kexue 2024, 45, 5049–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, G.; Luo, Y.; Huang, F.; Niu, Y.; Lei, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, W. Spatial characteristics of carbon emissions and carbon neutralization strategies for Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Urban Plann. Forum. 2022, 27, e16596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.H.; Huang, S.L.; Huang, P.J. Can spatial planning really mitigate carbon dioxide emissions in urban areas? A case study in Taipei, Taiwan. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, H. Spatial functional division, infrastructure and carbon emissions: Evidence from China. Energy 2022, 256, 124551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, F. Carbon emission accounting and spatial distribution of industrial entities in Beijing—Combining nighttime light data and urban functional areas. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Ecology and Environment. Demonstration and Leadership to Form a Green and Low-Carbon “Xiamen Model”. 2024. Available online: https://sthjj.xm.gov.cn/ztzl/ggcx/202408/t20240823_2886359.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Ecology and Environment. Fujian Xiamen: Pollution Reduction and Carbon Reduction Through Collaborative Innovation to Promote Green and Low-Carbon Development. 2024. Available online: https://sthjt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/hbyw/202412/t20241202_6587100.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Shi, L.; Xiang, X.; Zhu, W.; Gao, L. Standardization of the evaluation index system for low-carbon cities in China: A case study of Xiamen. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Xiamen Special Economic Zone Yearbook—2023. Available online: https://tjj.xm.gov.cn/tjnj/publish/2023/2023.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhang, Y.R. Methods and suggestions for low-carbon city construction in Xiamen under the dual carbon goals. Low Carbon World 2025, 15, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Wu, J. An extended time-series (2000–2018) of global NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light data from a cross-sensor calibration. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2020, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. 30 m annual land cover and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.M.; Zhang, L. Short-term travel behavior prediction with GPS, land use, and point of interest data. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 123, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuai, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Xie, F.; Zhao, R.; Li, J. Multiangle land use-linked carbon balance examination in Nanjing City, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 84, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, M.N.; Fang, R.Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q.P.; Wang, Q. Spatial-temporal characteristics of carbon emissions from land use change in Yellow River Delta region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Xi, F.M.; Yin, Y.; Bing, L.F.; Wang, J.Y.; Ma, M.J.; Zhang, W.F. Accounting and drivers of carbon emission from cultivated land utilization in Northeast China. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 32, 3865–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, X.J.; Zhen, F. Effects of land use patterns on carbon emission in Jiangsu Province. Trans. CSAE 2008, 24 (Suppl. S2), 102–107. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/QK200802515904 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Yan, X.H.; Zhong, Y.X.; Bo, L.; Tao, Y.W. The effects of land use changes on carbon emission C: Take Chongqing as an example. J. Chongqing Norm. Univ. 2012, 29, 38–42. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=2yANmoQUOTPMZcidAeY5uCeC4yNAsDt5Ee4sjt1wn6CUq5nubn_g5zurpoYPciksfBh9X6KVlLkokbG464_Ht5SivKWOPusWNsuYir5Qq5O63OmNYDnixEiusxkZSY5dT2RLwNfaBSOMzpNT0LimFSZTPsb1FshE&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Shi, H.; Mu, X.M.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, M.Q. Effects of different land use patterns on carbon emission in Guangyuan city of Sichuan province. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2012, 32, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.P.; Zhang, Y.X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.J. The research of carbon emission and carbon sequestration potential of forest vegetation in China. For. Resour. Manag. 2021, 2021, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Guo, Z.; Piao, S.; Chen, A. Terrestrial vegetation carbon sinks in China, 1981–2000. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2007, 50, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Shao, Q.Q.; Deng, X.Z. Temporal and spatial patterns of carbon sequestration services for primary terrestrial ecosystems in China between 1990 and 2030. Ecol. Front. 2016, 36, 3891–3902. Available online: https://www.ecologica.cn/stxb/ch/html/2016/13/stxb201411012141.htm (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lai, L.; Huang, X.J.; Zhang, X.L. Study on strategic environment impact assessment in land use planning. China Land Sci. 2003, 17, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.Z.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.X.; Peng, J.Y. Decoupling and spatiotemporal change of carbon emissions at the county level in China. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, D.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Han, S. Spatio-temporal dynamic evolution of carbon emissions from land use change in Guangdong Province, China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Q.; Huang, X.J. Carbon emission and carbon footprint of different land use types based on energy consumption of Jiangsu Province. Geogr. Res. 2010, 29, 1639–1649. Available online: https://www.dlyj.ac.cn/EN/10.11821/yj2010090010 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Peng, W.F.; Zhou, J.M.; Xu, X.L.; Luo, H.L.; Zhao, J.F.; Yang, C.J. Effect of land use changes on the temporal and spatial patterns of carbon emissions and carbon footprints in the Sichuan Province of Western China, from 1990 to 2010. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2016, 36, 7244–7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, M.; Cheng, S.; Hou, W.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y. Global 1 km× 1 km gridded revised real gross domestic product and electricity consumption during 1992–2019 based on calibrated nighttime light data. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Guo, Z.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z. GDP spatialization in Ningbo City based on NPP/VIIRS night-time light and auxiliary data using random forest regression. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhuo, L.; Shi, P.J.; Toshiaki, I. The study on urbanization process in China based on DMSP/OLS data: Development of a light index for urbanization level estimation. J. Remote Sens. Beijing 2003, 7, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, L.; Shi, P.; Chen, J. Application of compound night light index derived from DMSP/OLS data to urbanization analysis in China in the 1990s. ACTA Geogr. Sin. Chin. Ed. 2003, 58, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wei, A.X.; Mi, X.N.; Sun, G.T. An approach of GDP spatialization in Hebei province using NPP-VIIRS nighttime light data. J. Xinyang Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 29, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wu, Z.; Dai, Z. Identification and analysis of urban functional areas based on multi-source data. Surv. Mapp. Eng. 2023, 32, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, C. Research on urban functional area recognition integrating OSM road network and POI data. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 36, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Li, B. Extracting hierarchical landmarks from urban POI data. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 15, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Guo, N.; Gao, X.; Wu, F. How carbon emission reduction is going to affect urban resilience. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 372, 133737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, Q.; Ye, Y.; Shi, Z.; Liu, J.; Ding, Q.; Li, X. Analyzing spatial patterns of urban carbon metabolism and its response to change of urban size: A case of the Yangtze River Delta, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 104, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, J.; Sun, D.; Zhang, R.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J. Fine allocation of sectoral carbon emissions at block scale and contribution of functional zones. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 78, 102293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Linlin, X.; Weining, X. Analyzing spatial patterns of urban carbon metabolism: A case study in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Shi, Y.; Ren, C.; Yoshida, T.; Yamagata, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhou, N. The need for urban form data in spatial modeling of urban carbon emissions in China: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sharifi, A.; Yang, P.; Borjigin, H.; Murakami, D.; Yamagata, Y. Mapping building carbon emissions within local climate zones in Shanghai. Energy Procedia 2018, 152, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Type | Carbon Emission Factor (tC/hm2) | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cultivated land | 0.461 | Zhou Siyu [39] |

| Forest land | −0.613 | Li Ying [40], Xiao Hongyan [41] et al. |

| Grassland | −0.021 | Shi Hongxin [42], Yin Jingping [43] et al. |

| Water areas | −0.252 | Fang Jingyun [44], Huang Lin [45] et al. |

| Unused land | −0.005 | Lai Li [46], Zhang He [47] et al. |

| Functional Group | Specific Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic Function | Transportation Facilities Service | Railway stations, airports, bus terminals. |

| Business Function Service | Shopping Service | Retail stores, shopping malls, supermarkets. |

| Accommodation Service | Hotels, lodges, guesthouses. | |

| Sports and Leisure Service | Gyms, stadiums, cinemas, entertainment venues. | |

| Financial and Insurance Services | Banks, insurance companies, financial institutions. | |

| Catering Service | Restaurants, cafes, food and beverage outlets. | |

| Service for Life | Facilities supporting daily needs (e.g., maintenance, repairs). | |

| Public Management and Public Service Function | Medical Insurance Service | Hospitals, clinics, pharmacies. |

| Public Facility Service | Water, power, and sanitation utilities. | |

| Science, Education, and Cultural Service | Schools, museums, libraries, research institutes. | |

| Residence Function | Commercial Residence | Buildings combining residential and commercial functions. |

| Industrial Function | Incorporated Business | Corporate offices, business parks, headquarters. |

| Green Space and Square Function | Tourist Attraction | Sites of natural, cultural, or historical significance for visitors. |

| Type | Public Awareness | Type | Public Awareness | Type | Public Awareness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business-residential Property | 0.0100 | Shopping Services | 0.8146 | Accommodation Services | 0.5562 |

| Food and Beverage Services | 0.5562 | Financial Services | 0.3057 | Corporations | 0.3057 |

| Lifestyle Services | 0.3057 | Sports and Leisure | 0.5010 | Healthcare | 0.5069 |

| Government Agencies | 0.3550 | Science, Education, and Culture | 0.6706 | Transportation Facilities | 1.0000 |

| Equation | I | TNL | ||||

| R2 | Significance | R2 | Significance | R2 | Significance | |

| Linear | 0.373 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.007 | 0.691 | <0.001 |

| Logarithmic | 0.383 | <0.001 | 0.199 | <0.001 | 0.561 | <0.001 |

| Inverse function | 0.307 | <0.001 | 0.242 | <0.001 | 0.287 | <0.001 |

| Quadratic function | 0.389 | <0.001 | 0.117 | 0.007 | 0.692 | <0.001 |

| Cube function | 0.392 | <0.001 | 0.139 | 0.008 | 0.706 | <0.001 |

| Composite function | 0.411 | <0.001 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.602 | <0.001 |

| Power function | 0.467 | <0.001 | 0.330 | <0.001 | 0.801 | <0.001 |

| S function | 0.410 | <0.001 | 0.205 | <0.001 | 0.613 | <0.001 |

| Growth function | 0.411 | <0.001 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.602 | <0.001 |

| Logistic | 0.411 | <0.001 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.602 | <0.001 |

| Equation | S | CNLI | ||||

| Linear | 0.120 | 0.138 | 0.120 | 0.334 | ||

| Inverse function | 0.209 | 0.004 | 0.209 | <0.001 | ||

| Quadratic function | 0.026 | 0.160 | 0.026 | 0.034 | ||

| Cube function | 0.029 | 0.164 | 0.029 | 0.506 | ||

| Composite function | 0.035 | 0.303 | 0.035 | 0.090 | ||

| S function | 0.188 | 0.006 | 0.188 | <0.001 | ||

| Growth function | 0.035 | 0.303 | 0.035 | 0.090 | ||

| Logistic | 0.035 | 0.303 | 0.035 | 0.090 | ||

| ESC | Functional Zone Categories |

|---|---|

| 0–1 | I-T, I-R, P-T, P-G, R-B, T-B, T-H, P-C, G-B, RF, CF, O, CS |

| >1 | I, TF, T-G, I-G, GS |

| Carbon Balance Zone | Classification Criteria | Functional Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Core Carbon Sink Zone | ESC ≥ 1 and LL-type clustering | Regional core carbon sink nodes require strict protection of ecological spaces, prohibition of high carbon emission industries, and enhancement of carbon sink stability. |

| Carbon Sink Pressure Zone | ESC ≥ 1 and LH-type/HL-type/non-significant clustering | Carbon sink capacity compressed by peripheral high emissions or spatial isolation necessitates the establishment of ecological barriers and restrictions on new carbon emissions. |

| Core Carbon Source Area | ESC < 1 and HH-type clustering | High-intensity carbon emission agglomeration areas must implement mandatory emission reduction measures and promote deep low-carbon transformation of industrial structures. |

| Carbon Source Regulation Zone | ESC < 1 and LH-type/LL-type/HL-type/non-significant clustering | Dispersed carbon sources or transitional areas should gradually reduce carbon emission intensity through energy efficiency improvements and energy substitution. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Zhou, C.; Lin, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, C. Carbon Emission Patterns and Carbon Balance Zoning of Land Use in Xiamen City Based on Urban Functional Zoning. Land 2025, 14, 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112197

Wang Y, Wang H, Sun J, Zhou C, Lin X, Liu S, Wang C. Carbon Emission Patterns and Carbon Balance Zoning of Land Use in Xiamen City Based on Urban Functional Zoning. Land. 2025; 14(11):2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112197

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuhang, Haowei Wang, Jianhua Sun, Chenxin Zhou, Xiaofeng Lin, Shanhong Liu, and Cuiping Wang. 2025. "Carbon Emission Patterns and Carbon Balance Zoning of Land Use in Xiamen City Based on Urban Functional Zoning" Land 14, no. 11: 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112197

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, H., Sun, J., Zhou, C., Lin, X., Liu, S., & Wang, C. (2025). Carbon Emission Patterns and Carbon Balance Zoning of Land Use in Xiamen City Based on Urban Functional Zoning. Land, 14(11), 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112197