Abstract

The global energy transition is expected to require three to twenty times more land areas than fossil fuel-based power generation, making the availability of suitable land for the global energy transition a key challenge. Based on different types of energy resources, this study designs a telecoupling multi-regional input–output (MRIO) model to analyze cross-border electricity-driven embodied land appropriation patterns. The results show that the land footprint associated with renewable energy is substantially lower than that associated with conventional power generation. However, the growth rate of this footprint is 2.18 times higher than that of conventional electricity generation. China and Germany are identified as key export markets for wind- and solar- driven embodied land. The share of electricity-driven embodied land from China to the United States, Japan, and Germany declined, whereas the embodied land flowing to countries including South Korea, India, and Singapore increased. Embodied land-exporting nations face trilemma issues related to environmental degradation chain reactions, resource consumption threshold lines, and social distribution tensions, which may significantly affect decarbonization progresses. By integrating renewable power infrastructures and land use occupation, this analytical framework is expected to advance the understanding of energy–land nexus dynamics, providing theoretical foundations for cross-system governance in the implementation of carbon neutrality.

1. Introduction

Countries worldwide are undergoing an energy transition owing to climate deterioration and rising energy demand. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), electricity generation is the largest source of global CO2 emissions [1], yet it is simultaneously leading the shift to net-zero by accelerating the deployment of photovoltaic, wind, and other renewables [2,3,4]. While existing studies have extensively compared conventional and renewable energy generation [5,6,7], this transition introduces critical environmental pressures [8], particularly land pressures. Renewable energy requires 10 to 20 times more areas than fossil fuels to produce the same amount of electricity [9,10,11,12]. As countries continue to decarbonize, conflicts over arable land will intensify. Renewable infrastructures, such as wind and solar installations, impact soil quality [13] and biodiversity [14]. These problems position land resource pressures as an urgent multidisciplinary challenge, requiring systematic analysis to reconcile climate goals with ecological and socioeconomic sustainability [15]. In addition, the power production of photovoltaics (PV) has increased rapidly, with greater renewable land competition anticipated in the coming decades [16]. To address this issue, existing studies also evaluated the photovoltaic potential of different land types to identify suitable land for renewable energy production [17,18].

To date, life cycle assessment (LCA) [19,20,21] and multi-regional input–output (MRIO) analysis have been widely used to evaluate land use impacts [22]. However, LCA lacks uniform evaluation standards, while MRIO exhibits limited specificity regarding the electricity sector. In LCA studies, existing research indicates that hydropower achieves the highest land use density under static–indirect calculations, followed by wind and solar [6]. However, dynamic direct methods rank biomass second [23], whereas dynamic indirect approaches rank it first [24]. Introduced by Leontief [25], input–output analysis (IOA) has been extensively applied to assess ecological and environmental impacts within global supply chains, including energy [26], carbon [27], and land use [28]. Within specific sectors such as electricity, IOA quantifies resource consumption [29], environmental [30], economic impacts [31,32,33], and employment effects [34,35]. The MRIO has been widely employed to evaluate the embodied land use of all nations by identifying direct and indirect land occupation associated with global goods and services [24].

Existing MRIO-based literature includes time-series analyses of China’s land resources [36,37] and investigations into global land flows that reveal allocation imbalances [38,39]. Further studies mainly integrated embodied land use with international trade [37,40,41], embedded disparities in domestic trade [42], and multi-scale land use in domestic trade [43]. Concurrently, the driving factors of embodied land use are critically essential at different scales. Economic, technological, and institutional conditions have been identified as the primary drivers of European agricultural land use [44]. By examining natural and human factors, China’s 31,275 rural towns were analyzed using multiple data sources [45]. By building an ecological inventory and network, 13 cities in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region of China were analyzed, revealing inter-city land flows and resource distribution inequality [46].

Telecoupling analysis contains three paradigms, i.e., intracoupling, pericoupling, and telecoupling. Liu et al. [47] examined the telecoupling of socioeconomic and ecological systems between nations through the flow of goods, resources, and information, and telecoupling transcends traditional geographical constraints. This paradigm shift has established telecoupling as a crucial tool for addressing sustainability challenges in the context of globalization. Recent methodological innovations also integrated telecoupling with multi-regional input-output modeling, which decoded agricultural cropland displacement via trade networks [48,49]. Besides, Kosai et al. [50] evaluated transnational land disturbances triggered by the telecoupling effects of manufacturing for specific products. This approach enhances the understanding of issues such as biodiversity conservation [51], water security [52], and energy transitions [53], while also advancing newer disciplines, including carbon leakage through embodied emissions [54], labor market restructuring within global value chains [55], and food system transformations [56]. Notably, the growing scholarly application of telecoupling theory to trade-off phenomena across multiple domains has accelerated the progress of systemic sustainability assessments.

Building on the telecoupling method, Xiong et al. [57] integrated the World Input–Output Database (WIOD) tables to quantitatively examine nations’ contributions to economic-environmental flows in metal trade and their variation across positions within contemporary global value chains (GVCs). Oberlack [58] used telecoupling to further advance the sustainable analyses of land governance in interrelated systems. López-Hoffman [59] applied telecoupling theory to calculate dependencies of migratory species providing services at widely separated sites, showing examples of telecoupled dynamics. Focusing specifically on the power sector, the telecoupling method anticipated would help build a systematic sustainability assessment framework.

Existing research has extensively investigated land occupation within national electricity sectors, however, a more pressing inquiry emerges under globalization: First, this study proposed a tele-connecting framework to integrate electricity-driven land use with mutil-regional input-output modeling; second, this study analyzed the power sector’s land appropriation and exhibited geospatial imbalances; third, this study identified the primary sources of electricity-driven embodied land flows by type. To address these interconnected issues, this study integrates multi-regional input-output modeling with telecoupling theory to track embodied land appropriations across transnational electricity systems, elucidating how territorial displacements and responsibility asymmetries manifest in international trade.

In this context, by integrating the telecoupling framework with the MRIO approach, this study examines the embodied land use associated with electricity generation across nations, which elucidates the transnational flows of electricity-driven embodied land appropriation and enables the systematic allocation of responsibility for land resource utilization. The study proceeds as follows: Section 2 details the telecoupling-MRIO methodology and data sources. Section 3 presents findings on electricity-driven embodied land use, its global flows, and sectoral sources. Section 4 discusses policy implications and governance strategies. Section 5 draws concluding remarks.

2. Methods and Data Sources

By combining telecoupling theory with multi-regional input–output analysis, this study explores the interaction between electricity-driven natural systems and socio-economic systems between geographically distant countries. The telecoupling method identifies the sending and receiving systems, while MRIO quantifies the global flow of goods and the embodied transfer of land resources. These flows manifest as internal couplings within national boundaries, while international trade extends these interactions to neighboring countries and non-neighboring countries.

2.1. Telecoupling Mechanisms in Electricity–Land System Interactions

This study examines the concept of telecoupling and demonstrates how it improves the understanding of land use changes linked to electricity systems in a globalized world. The development of global supply chains has led to a spatial disconnect between the location where electricity is generated and where its land footprint is ultimately consumed. Identifying and promoting sustainable, equitable land use practices while phasing out unsustainable ones has thus become a complex challenge. By integrating land use changes with sustainability issues related to electricity, this study systematically examines the relevance of telecoupling research against the backdrop of rapid energy transition. This study reflects on several pressing issues in contemporary land use change and proposes a future agenda for advancing the understanding of sustainable land use change through interdisciplinary research.

Telecoupling theory conceptualizes reciprocal socio-ecological interactions across spatially disconnected systems, especially in the power sector. Globalization has spatialized this path, causing traded goods to carry ecological footprints rooted in both the production sites and manifested at the consumption end. At the national level, the production system exhibits dual resource dependency, which relies directly on socioeconomic inputs such as labor and capital, as well as ecological assets such as water and land; however, it also accounts for indirect ecological costs embodied within supply chains, such as the electricity embodied in finished products. Industrial electricity demand drives power generation, which directly consumes land and coal resources. These ecological burdens are transmitted stepwise along the power supply chains, ultimately settling in the end products and forming a cross-system transmission path, from land to electricity to goods.

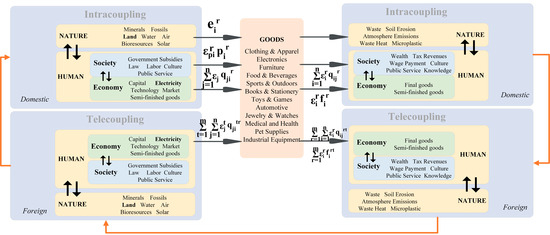

Through the integration of telecoupling theory and multi-regional input–output modeling, this study developed an energy-land nexus system framework within global trade networks, as illustrated in Figure 1. By mapping the pathway from land occupation through electricity to commodities, this study identifies the mutual influences between natural and human systems within a country and the remote impacts of natural and human systems across different countries. This nested systems perspective transcends the conventional single-system paradigm, offering a novel diagnostic tool for understanding emergent behaviors in global socio-ecological systems.

Figure 1.

The telecoupling mechanism for global electricity-driven embodied land flows.

2.2. Multi-Regional Input–Output Modeling

To overcome the methodological limitations of traditional electricity-driven land occupation assessments, this study employed a multi-regional input–output model to quantify the embodied land use of power generation systems by energy type across different countries. Here, embodied refers to the electricity-driven land resources embodied in internationally traded commodities, that is, the land resources consumed for power generation to produce goods, which ultimately become an intrinsic component of the commodities themselves through global trade circulation. By integrating land use intensity coefficients (ha/GWh), this study established systematic linkages between electricity generation and territorial appropriation. To avoid double-counting electricity flows, our analysis focused exclusively on source-level generation data from the power sector, thereby limiting input–output computations to electricity-specific transactions within the MRIO framework.

The computation of embodied electricity-driven land use proceeds through sequential analytical stages. First, direct land occupation attributable to power generation is derived by multiplying national electricity output (GWh) by energy-specific land use intensity coefficients (ha/GWh). This is followed by the systematic incorporation of these territorial metrics into a multiregional input–output framework to trace land appropriation embodied in transnational electricity flows. The calculation of the direct land area for different energy sources is as follows:

where L denotes direct land occupation (ha); P represents national electricity generation by energy type (GWh); I signifies energy-specific land use intensity coefficients (ha/GWh). For specific values, please refer to Table 1. The computation yields 189 countries and economies, and the columns correspond to different energy categories, including coal, gas, wind, and solar.

To calculate the embodied land area, the input–output method was adopted, modeling the global economy as a network comprising m regions and n sectors. This approach balances resource and energy inflows and outflows. The balance of embodied land flows through sector i in region r can be expressed as follows:

where is the onsite land resources usage by sector i in region r; is the primary inputs denoted by the society into sector i in region r; is the intermediate inputs from sector j into sector i in region r; is the sectoral output of sector i in region r; denotes the goods or services produced by sector i in region s as intermediate inputs into sector j in region t; represents the goods or services that are produced by sector i in region r as household consumption, consumption of non-profit institutions serving households or government consumption in region t; represents the goods or services that are produced by sector i in region r as the rest of final demand in region t; represents the embodied land use intensity of primary inputs of sector i in region r; represents the embodied land use intensity of goods or services produced by sector i in region r; represents the embodied land use intensity of goods or services produced by sector j in region t.

Given that each term in Equation (2) represents interactions across multiple countries and sectors, we express these multidimensional relationships in the matrix form presented in Equation (3) as follows:

where ; ; is the diagonal matrix for P; ; ; ; ; is the diagonal matrix for O.

The relationship between final demand and primary inputs in the input–output table can be represented by the socio-economic matrix [60,61]:

The matrix form of the equation above can be written as follows:

where Psum is the aggregated number of primary inputs; FR represents the 1 column matrix for the rest of final demand. Solving Equations (2) and (4) yields:

To account for nations’ divergent roles in global trade networks, embodied land in final demand was quantified using dedicated formulations.

2.3. Data Sources

Building upon the method outlined above, analyzing the global flows of embodied land resources from 2000 to 2020 requires three critical datasets: national electricity generation data for different energy sources, electricity-land intensity coefficients across power generation technologies, and global multi-regional input–output (MRIO) datasets. The first two datasets are detailed in the subsequent section, followed by a description of the MRIO database in the next subsection. Global trade data were obtained from the Eora MRIO database [62] that tracks resource use and environmental impacts throughout international supply chains. International trade data in the Eora database is widely used to analyze embodied carbon emissions, land use, and other environmental impacts, enabling cross-border quantitative analysis. The International Energy Agency (IEA) database provides extensive data on global energy production, consumption, and trade, covering various energy sources, such as electricity, oil, and natural gas [2]. This study utilized IEA data related to coal, gas, wind, and solar power generation across 189 countries and economies. To analyze the evolution of electricity-driven land use, data from 2000 to 2020 are examined in five-year intervals. The correlation between generation capacity and land area was calculated to assess each nation’s direct land requirements for power generation. After reviewing previous studies, any outliers or implausible data, such as data on wind power that solely accounted for the turbine area, were eliminated. The median of the remaining data was employed to estimate density. The final outcomes align with those reported by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) [9]. All the statistical computations were performed using MATLAB (Version R2020b).

Table 1.

The density of electricity–land coefficients.

Table 1.

The density of electricity–land coefficients.

| Energy | Intensity Coefficient (ha/GWh) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Coal | 0.05 | [5,7,63,64] |

| Gas | 0.06 | [5,6,7,63] |

| Wind | 0.13 | [6,24,63,65] |

| PV | 0.17 | [5,6,7,24,44,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] |

3. Results

3.1. Direct and Embodied Electricity-Driven Land Use

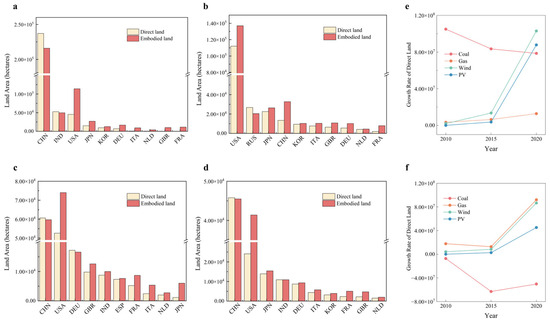

Figure 2 compares the direct and embodied land footprints of four energy generation systems, i.e., coal, natural gas, wind, and solar resources. Contrary to conventional assumptions, fossil fuel systems exhibit a larger total direct land occupation than renewables, with coal occupying 4.58 × 105 hectares compared to solar occupying 1.49 × 105 hectares. This phenomenon stems from the fact that fossil fuels account for a much higher share of global electricity generation than renewable energy, with fossil fuels accounting for 35.14% while renewables account for only 3.06%. Although fossil energy has a lower land-use efficiency per unit of energy produced, it accounts for the vast majority of global energy demand, thereby increasing the total land footprint.

Figure 2.

Direct and embodied land use in the top ten countries by direct land occupation area. a-d show land use for coal (a), natural gas (b), wind (c), and solar (d) power generation. (e,f) show the growth rates of direct land occupation in China and the United States, respectively.

For coal power, China occupies the largest land area for power generation, with direct land use of 2.43 × 105 hectares surpassing embodied land use of 2.23 × 105 hectares, highlighting its significant role as a global embodied land provider for the power sector. India exhibited a similar role, with direct and embodied land use areas of 5.26 × 104 and 4.96 × 104 hectares for the power sector, respectively. The United States shows the most significant disparity, with direct electricity-driven land use being 6.82 × 104 hectares less than embodied land use (1.14 × 105 hectares), indicating a greater reliance on foreign land. A similar pattern was observed in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Norway. Although Japan and South Korea rely on global supply chains, with electricity-driven embodied land use areas of 2.69 × 104 and 1.27 × 104 hectares, respectively, these countries primarily depend on domestic land resources, with direct land use areas of 1.49 × 104 and 9.59 × 103 hectares, respectively. While North American and European countries rely more heavily on global supply chains to meet embodied land use related to coal power, developed East Asian economies show less dependency on global supply chain. Meanwhile, developing Asian nations largely supply the embodied land resources.

Figure 2b analyzes the natural gas power systems, revealing distinct regional variations in land use patterns. The United States led in both direct and embodied land footprints of 1.12 × 105 hectares and 1.37 × 105 hectares. Russia followed with the second-highest direct land use of 2.67 × 104 hectares, whereas China ranked second in embodied land use of 3.73 × 104 hectares. Among the top ten countries, all rely on global supply chains to meet the embodied land use of gas power generation, with Russia being the sole exception. With natural gas reserves representing approximately 19.9% of the global total, Russia contributes 2.04 × 104 hectares of embodied land use to the international supply chain. Regarding wind power and solar power, China leads in direct land use, with 6.09 × 104 hectares for wind and 4.69 × 104 hectares for solar. Additionally, China accounted for the highest embodied land use for solar power at 4.68 × 104 hectares, whereas the United States led in wind power, totaling 7.40 × 104 hectares. Notably, the United States demonstrates the most significant difference between direct and embodied land use for both wind and solar power, with direct land use being 2.14 × 104 and 1.72 × 104 hectares lower than embodied land use for wind and solar, respectively.

The growth rates of electricity-related direct land areas were analyzed for China, the largest exporter of embodied land, and the United States, the largest importer of embodied land. In China, the growth rate of coal-related direct land occupation showed a declining trend, decreasing from 1.05 × 108 hectares/yr in 2010 to 7.86 × 107 hectares/yr in 2020. The growth rate of natural gas-related direct land use demonstrated a relatively moderate increase, rising from 3.42 × 106 hectares/yr in 2010 to 1.28 × 107 hectares/yr in 2020. In contrast, the growth rates of direct land occupation for wind and solar power increased significantly after 2015, jumping directly from 1.35 × 107 hectares/yr and 3.72 × 106 hectares/yr to 1.03 × 108 hectares/yr and 8.78 × 107 hectares/yr, respectively. Meanwhile, the United States experienced negative growth in direct land occupation for coal power, improving from −7.19 × 106 hectares/yr in 2010 to −5.03 × 107 hectares/yr in 2020. The growth rates of direct land use for the other three types of power generation all showed upward trends, with wind and solar power reaching 8.66 × 107 hectares/yr and 4.53 × 107 hectares/yr, respectively, by 2020. This divergence reflects asymmetrical policy commitments to renewable industrialization under the respective decarbonization roadmaps.

3.2. Electricity-Driven Land Embodied in Imports and Exports

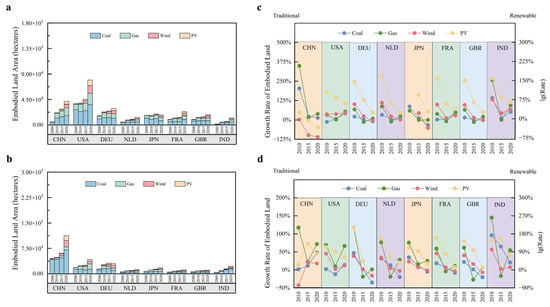

Figure 3 presents the trend of electricity-related land occupation embodied in trade from 2000 to 2020. Embodied land flows associated with electricity grew at a compound annual rate, driven by increasing global grid integration, and the land-use share of traditional thermal power contracted persistently. Meanwhile, renewable energy systems showed yearly steady growth in embodied land use, indicating that renewable power generation has matured within standardized sustainability protocols.

Figure 3.

Embodied import and export land areas of the top eight countries in total embodied land trade (2000–2020). (a,c) show the changes in embodied land imports for four electricity generation types, while (b,d) show the changes in embodied land exports.

From Figure 3a, an annual increase in embodied land imports was observed in several countries. Japan was the exception, with its embodied land use declining from 1.92 × 104 hectares in 2015 to 1.60 × 104 hectares in 2020. Between 2000 and 2010, China’s electricity-related embodied land imports grew from 1.67 × 104 hectares in 2000 to 2.17 × 104 hectares in 2010. Over the same period, India’s area more than doubled, rising from 1.81 × 103 to 5.18 × 103 hectares. From 2015 to 2020, the United States and France nearly doubled their import values, reaching 7.94 × 104 and 2.32 × 104 hectares, respectively. These trends indicate a general increase in the demand for land embodied in imports, with notable fluctuations in between. Among exporting countries, Germany experienced a slight decrease in the total embodied land area, from 3.11 × 104 hectares in 2015 to 3.06 × 104 hectares in 2020, while the other seven countries recorded annual increases. India’s embodied land exports more than doubled between 2000 and 2010, rising from 4.37 × 103 to 9.38 × 103 hectares. From 2015 to 2020, both China and the United States significantly increased their embodied land exports, reaching 1.32 × 105 hectares (an increase of 85.35%) and 4.21 × 104 hectares (an increase of 66.27%), respectively.

The share of embodied land use associated with coal and natural gas power declined in most countries’ trade except the United States and Japan. In the United States, the embodied land exports for natural gas rose from 26.99% in 2000 to 36.60% in 2020. In Japan, the share increased slightly from 36.26% to 36.77%. Embodied land use for wind and solar power generally increased across most regions except for Japan as an exception. Between 2000 and 2020, Japan’s embodied land use for wind power fell from 20.21% to 14.34%, and for solar from 12.92% to 11.69%. China’s embodied land use of coal power was 39.72%, while the United States had a larger share of 45.24%. Globally, coal accounted for about 32% of embodied land exports. In 2020, coal made up 62.20% of China’s and 63.29% of India’s embodied land use, down from 92.12% and 82.61% in 2000, respectively.

The growth rates of embodied land areas for different electricity generation types across countries over time were analyzed, as shown in Figure 3c,d. For imports, the growth rates of embodied land areas slowed over time in most countries, with slight rebounds in 2020, except for the United States and Japan. China and India experienced the most significant slowdowns in the growth rates of embodied land use from traditional energy sources. In China, the share of land use embodied in coal-fired power relative to total domestic electricity generation decreased from 2.03 times the 2010 level to just 0.13 times by 2020. Over the same period, India’s ratio declined from 1.42 to 0.52 times. Solar power related embodied land use growth rates declined more significantly than wind power. In France and India, the growth rate of wind-related embodied land rebounded in 2020, rising from 1.08 times and 1.66 times to 1.35 times and 2.30 times, respectively. The growth rate of wind power’s embodied land use in the United States increased steadily from 1.52 times in 2010 to 1.72 times in 2020, while that of solar power plummeted from 11.46 to 3.87 times. In Japan, the growth rates for wind and solar power related embodied land increased from −75.65% and 95.75% in 2010 to 1.67 and 8.67 times in 2015, fell again to 44.06% and 1.91 times in 2020.

Except for China and India, the growth rates of electricity-driven embodied land exports declined over time, though a slight rebound occurred in 2020 (Figure 3d). Germany’s solar-related embodied land exports exhibited the most significant change, declining from 130.89 times in 2010 to 0.52 times in 2020. In both China and India, the growth rates of solar-related embodied land use initially increased, followed by a subsequent decline. In China, the growth rate of electricity-driven embodied land increased from 1.83 times in 2010 to 20.14 times in 2015, before falling to 6.35 times in 2020. In India, the growth rate of embodied land increased from 30.98 times to 36.09 times, then dropped to 5.40 times. India saw the sharpest decline in the growth rate of wind related embodied land exports, falling from 10.38 times in 2010 to 1.38 times in 2020. These shifts in the growth rates of embodied land imports and exports reflect a broader transition toward a more stable phase of development in both conventional and renewable energy generation.

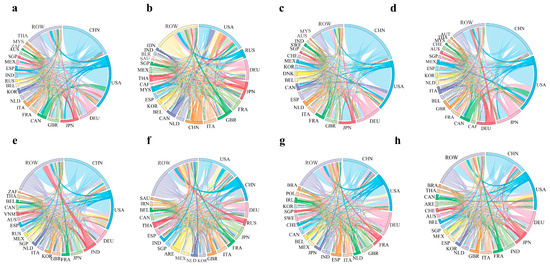

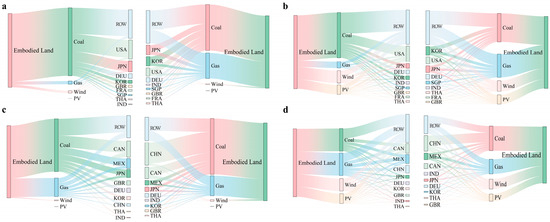

3.3. Electricity-Driven Land Embodied in Trade Flows

Land areas of the top countries embodied in total trade during 2000 and 2020. Figure 4 reveals a structural asymmetry in global embodied land flows during this period. China accounted for 22.50% of total electricity-driven embodied land exports, with 22.58% from traditional energy and 22.31% from renewables. Meanwhile, the United States absorbed 15.83% of global embodied land imports, comprising 15.90% from traditional sources and 15.65% from renewables. From 2000 to 2020, the top two coal-related embodied land exporters shifted from China and the United States to China and India (Figure 4a,e). China’s share of coal power related embodied land exports dropped from 37.40% in 2000 to 31.73% in 2020. In 2020, China exported 5.26 × 103 hectares of coal-related embodied land to the United States and 1.18 × 103 hectares to Japan. India exported 7.48 × 102 hectares to the United States and 1.93 × 102 hectares to China. Compared to 2000, the embodied land flowing from China to the United States fell by 1.33 × 103 hectares, and to Japan by 1.25 × 103 hectares. In 2020, the largest embodied land importers shifted: Japan and the United States were replaced by China and the United States. During 2000 and 2020, the United States’ share of global coal-related embodied land imports decreased from 32.96% to 23.75%, while China’s share reached 10.18% in 2020. In 2020, China was the primary source of the United States’ embodied land imports, followed by Mexico with 9.25 × 102 hectares. China’s primary sources were Japan with 5.01 × 102 hectares and the United States with 4.85 × 102 hectares.

Figure 4.

Flow of embodied land for different types of electricity across countries in 2000 and 2020. (a–d) show the embodied land trade for coal power (a), natural gas power (b), wind power (c), and PV power (d) in 2000, while (e–h) depict the embodied land trade for the four electricity generation types in 2020.

For natural gas, the United States and China consistently ranked as the largest exporters of embodied land from 2000 to 2020 (see Figure 4b,f). The United States’ share of global embodied land exports increased from 9.09% in 2000 to 10.42% in 2020, while China’s share changed from 8.53% to 8.71%. Notably, in both 2000 and 2020, the United States and Japan were the primary destinations for China’s natural gas-related embodied land. Specifically, in 2000, China exported 5.23 × 102 hectares of embodied land to the United States and 1.92 × 102 hectares to Japan. By 2020, the embodied land flowing to the United States increased to 8.94 × 102 hectares, while the flow to Japan decreased to 1.85 × 102 hectares. In contrast, the leading destinations for the United States’ embodied land exports shifted from Japan and Mexico in 2000 to China and Canada in 2020. In that year, the United States exported 4.90 × 102 hectares to Canada and 4.09 × 102 hectares to China. Furthermore, the largest importers of embodied land shifted from the United States and Japan in 2000 to the United States and China in 2020. Throughout the period, China and Japan have consistently been the main sources of embodied land for the United States. In addition to the United States, China also imported 3.74 × 102 hectares of embodied land from Japan in 2020.

In 2020, China and Germany were the largest exporters of embodied land for both wind and solar power (see Figure 4g,h), with exports of 4.18 × 103 hectares and 2.62 × 103 hectares of wind power, and 3.22 × 103 hectares and 1.51 × 103 hectares of solar power, respectively. The United States and China were the primary importers. The United States imported 4.32 × 103 hectares from wind power and 3.27 × 103 hectares from solar power. China imported 1.62 × 103 hectares of wind-related embodied land and 1.33 × 103 hectares of solar-related embodied land, which was less than half of the United States imports. China exported 1.45 × 103 hectares from wind power and 1.11× 103 hectares from solar power to the United States, along with 3.24 × 102 hectares from wind and 2.47 × 102 hectares from solar to Japan. Germany sent 3.15 × 102 hectares from wind power and 1.81 × 102 hectares from solar power to the United States. Germany also sent 2.88 × 102 hectares of wind- and 1.67 × 102 hectares solar-related land exports to China. The United States imported 5.36 × 102 hectares of wind power and 3.54 × 102 hectares of solar power related land from Mexico. Meanwhile, China received 3.24 × 102 hectares of wind power and 2.47 × 102 hectares of solar power related land from Japan.

From Figure 4, China remained the leading exporter of renewable energy driven land use since 2000. By 2020, Germany had also emerged as a major exporter. Conversely, the United States and Japan have primarily acted as importers. Specifically, Japan emerged as the second-largest exporter of embodied land for solar power, exporting 2.92 hectares in 2000, following China. In that same year, China led with exports of 11.60 hectares of embodied land related to solar power and 5.22 × 102 hectares of embodied land related to wind power. Additionally, Japan, rather than China, was the largest importer of embodied land for both wind and solar energy, alongside the United States. Japan imported 1.20 × 102 hectares of wind related embodied land and 2.81 hectares of solar related embodied land, while the United States imported 3.99 × 102 hectares of wind-related and 10.51 hectares of solar-related embodied land.

As shown in Figure 5, China’s imports and exports of coal related embodied land declined substantially between 2000 and 2020. During the same period, the share of wind and solar power in embodied land trade increased markedly (Figure 5a,b). In both 2000 and 2020, the primary destinations for China’s embodied land use in the electricity sector were the United States, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. The proportion to the United States remained relatively stable, decreasing slightly from 25.77% to 21.21%, Japan’s share falling from 14.86% to 6.47%, Germany’s share decreasing from 6.42% to 5.40%, and South Korea’s share increasing from 4.22% to 5.21%. Except for South Korea, the proportions of flow to India, Singapore, and Thailand all increased. India showed the largest gain, rising by 3.24%, not including the share attributed to the Rest of the World.

Figure 5.

Sources and sinks of embodied land use in China and the United States. (a,b) represent the sources and sinks of embodied land use in China for the years 2000 and 2020, respectively; (c,d) show the sources and sinks of embodied land use in the United States for the years 2000 and 2020, respectively.

Between 2000 and 2020, China’s electricity-driven embodied land flows underwent a significant restructuring, with import dependencies increasingly shifting toward emerging economies in Asia. Trade linkages to India, Singapore, and Thailand are intensified, coinciding with Belt and Road energy infrastructure investments. Conversely, the proportion of land occupation embodied in trade between China and the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom has declined. This reflects China’s weakening dependence on Western imports after 2010, as well as its strategic decoupling in key mineral supply chains. The main sources of embodied land use related to electricity for China were Japan, South Korea, the United States, and Germany. Japan’s share decreased by 3.96%, from 13.42% to 9.46%; South Korea’s share slightly declined from 12.84% to 12.26%; the United States’ share dropped from 11.27% to 9.59%, and Germany’s share increased by 0.48%, from 6.38% to 6.86%. The proportion of embodied land use related to electricity imported from Singapore saw the largest increase, rising by 1.93%.

In 2000, the primary destinations for the United States’ embodied land use were Canada (22.30%), Mexico (13.77%), Japan (11.29%), and the United Kingdom (6.21%). By 2020, the major destinations had shifted to Canada (14.09%), Mexico (13.53%), China (11.64%), and Japan (4.66%). Aside from China, exports of embodied land to India and Thailand also increased, by 1.56% and 0.12%, respectively. In terms of imports, the main sources of the United States’ embodied land use in 2000 were China (29.30%), Canada (14.67%), Mexico (5.98%), and Japan (5.80%). By 2020, India (5.25%) had surpassed Japan (4.29%) to become the fourth-largest source of embodied land use for the United States. Over these two decades, the share of embodied land use imported from India, Mexico, and Thailand to the United States increased, with Mexico showing the largest increase, rising by 5.81%.

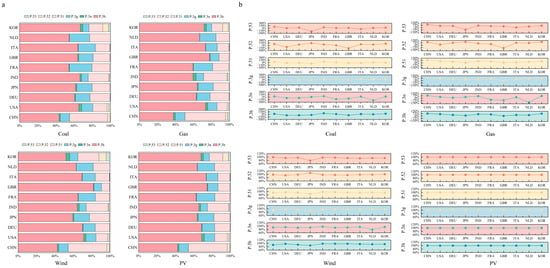

3.4. Sectoral Structures of Electricity-Driven Land Use Changes

This study further investigates the sectoral structures of electricity-driven embodied land use from production and consumption perspectives. The results, as shown in Figure 6, reveal that, regardless of the country, the primary sources are household final consumption, government final consumption, and gross fixed capital formation. From Figure 6a, for coal-fired power, the household final consumption is the leading contributor to embodied land use in coal power across all countries, accounting for more than 43.37%. South Korea stands out with the highest impact, where household final consumption reached 66.91%. In France and Italy, government final consumption was the second-largest source, accounting for 24.82% and 18.98%, respectively. This indicates that the public sector plays a key role in electricity-driven embodied land use, likely due to government-led demand for public projects and services. In other countries, gross fixed capital formation was the second major source, with contributions exceeding 15.29%. The influence of other factors in these countries generally remained below 11.03%.

Figure 6.

Sectoral structures of electricity-driven embodied land use. (a) presents embodied land use from the consumption perspective; (b) shows the relative differences across consumption-based sectors between 2000 and 2020. Abbreviations P.3h to P.53 sequentially represent Household final consumption, Non-profit institutions serving households, Government final consumption, Gross fixed capital formation, Changes in inventories, and Acquisitions less disposals of valuables.

For natural gas related embodied land, the situation is similar to that of coal power. However, in China, gross fixed capital formation emerges as the primary source, accounting for 44.88%, followed by household final consumption at 37.76%. This indicates that, in China, capital investments in infrastructure and related sectors were significant contributors to embodied land use for gas-fired power generation. In the Netherlands, government final consumption was the second-largest source (18.06%), while in Italy, gross fixed capital formation takes this position (13.25%).

For wind and solar related embodied land use, household final consumption remained the largest contributing factor in all countries, followed by gross fixed capital formation, except in France and the Netherlands. Notably, in the countries other than China, household final consumption exhibtated a significantly greater impact than other factors, accounting for more than 52.11%, which underscores its dominant role. In China, household final consumption and gross fixed capital formation contributed almost equally, each accounting for around 40%. This suggests that while household consumption was the primary source of embodied land use in electricity generation in most countries, in China, both household consumption and capital investment played equally significant roles. This distinction highlights the more balanced influence of infrastructure development and individual consumption patterns on the embodied land use associated with China’s energy production.

Figure 6b illustrates the changes in impact across final demand categories from 2000 to 2020. For coal power related embodied land use, China, India, and South Korea were the only countries to experience consistent positive growth across all sectors, while other countries showed negative growth in various sectors. In the United States and the United Kingdom, all sectors saw negative growth except for acquisitions less disposals of valuables, which grew by 11.68% and 18.48%, respectively. In France and the Netherlands, all sectors experienced positive growth except for non-profit households, which declined to −0.20 and −0.94 times, respectively. In Germany, the household final consumption (−51.16%), non-profit households (−52.11%), and the gross fixed capital formation (−7.58%) all showed negative growth. In Japan, only non-profit households (4.28%) and changes in inventories (1.38 times) experienced growth. In Italy, gross fixed capital formation decreased by 16.80%, and acquisitions less disposals of valuables fell by 47.37%, while the other sectors saw positive growth.

The situation for the traditional and renewable driven embodied land use differs significantly. For natural gas related embodied land use, only a few countries experience sector-specific negative growth. Notably, non-profit households in France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands declined by 46.08%, 63.08%, and −0.30 times, respectively. Additionally, the changes in inventories in Germany (−86.62%) and acquisitions less disposals of valuables in Japan (−66.27%) also decreased. Meanwhile, China showed the largest growth across nearly all sectors, except for changes in inventories. For wind and solar power related embodied land, the outlook is more optimistic, with over 80% growth in all six sectors across the ten countries.

4. Discussion and Policy Implications

This study examines changes in both direct and embodied land use associated with traditional and renewable electricity generation from 2000 to 2020, incorporating cross-country comparisons of the electricity-driven embodied land use. Between 2010 and 2020, the embodied land flows associated with wind and solar power grew more rapidly than those associated with fossil fuel driven energy systems. The land footprint of renewable energy increased by approximately 90%, three times the rate of that of traditional energy systems. Regarding national contributions, China supplied 2.03 × 104 hectares of coal power related embodied land and 1.15 × 102 hectares of wind power related embodied land for the final consumption in other countries. India provided 3.05 × 103 hectares of embodied land linked to coal power. Conversely, the United States relied on international supply chains for 2.14 × 104 hectares of wind power and 1.72 × 104 hectares of solar power related embodied land to satisfy its consumption demand. China and Germany dominated wind and solar power related land exports, accounting for 32.42% of the global share. Meanwhile, China and India together accounted for 28.50% of the coal power related land transfers. Simultaneously, Germany solidified its role as Europe’s renewable land-export hub, commanding 12.65% of wind and 10.16% of solar power related land transfers, a regional complement to China’s global ascendancy. Additionally, China’s South–South trade captured emerging markets through targeted exports to India, Singapore and Thailand.

Based on the findings above, it is conclusively established that a global phenomenon exists, whereby land resource consumption driven by domestic demand is transferred to other countries through trade channels. This externalization of resource pressures has significantly adverse effects on both source and recipient countries. For recipient countries, land resource demands driven by foreign final consumption may trigger a series of cascading crises in natural and socioeconomic systems. Specifically, to meet land demands embodied in export trade, these countries may face increased desertification, biodiversity loss, soil erosion, and large-scale encroachment on farmland. Consequently, they are likely to experience environmental governance costs, increased food security risks, and potentially aggravated social conflicts and governance challenges. For source countries, although the short-term transfer of resource pressures reduces domestic ecological burdens, the long-term reliance on external resource supplies leads to dependence on the stability of land resource provision from other nations to meet their final demand, creating strategic vulnerabilities. Such dependency not only entails the risks of supply chain disruption but may also undermine national resource sovereignty, thereby affecting long-term ecological security and economic resilience.

The transfer of land resource consumption worldwide is driven by multidimensional and systemic factors. Generally, environmental costs arising from resource extraction and environmental pollution are not fully internalized in commodity prices, resulting in uncompensated ecological losses in countries exporting embodied land resources. Many bilateral trade agreements and international investment frameworks prioritize market accesses and economic gains over binding cross-border environmental accountability, indirectly exacerbating the resource pressure spillover. Moreover, existing international regimes lack clear transboundary mechanisms for holding accountable the countries that consume resources, making it difficult to assign compensation or remediation responsibilities to these countries for ecological damage abroad. The narrow emphasis of the current international sustainability agenda on carbon reduction also drove a rapid shift toward renewable energy sources, without adequate consideration of the electricity-driven embodied land use implications. This oversight has intensified the environmental pressure on resource-supplying countries. At the national level, consuming countries obscure the full land footprint embodied in imported goods, making it difficult for consumers and businesses to recognize the impact of their consumption on ecosystems abroad. Additionally, technologies for enhancing resource efficiency remain either underdeveloped or cost prohibitive in some countries. Consequently, continued reliance on the embodied land in imported goods may appear economically rational in the short term.

Addressing the challenges of the energy–land nexus system requires integrated, multi-scalar governance frameworks that explicitly rectify the externalization of land pressures embodied in the global supply chains. It is essential to establish transparent transboundary accounting of embodied land flows and compensatory mechanisms, whereby importing countries provide financial remediation to exporting nations for habitat degradation and agricultural displacement caused by renewable material extraction. International institutions need to harmonize the mandatory ecological redlines for renewable energy projects to prevent deforestation and farmland conversion, ensuring that energy transitions do not undermine global food security or biodiversity conservation. At the regional level, developed economies should promote technological justice through cooperative ventures, such as donor-financed high-efficiency photovoltaic installations and grid modernization in land-vulnerable countries. Such partnerships can overcome technological barriers and reduce asymmetrical burdens on resource-supplying areas. Governments need to accelerate the research, development, and deployment of land-sparing technologies, such as perovskite solar panels, agrivoltaics, and offshore wind clusters. These technologies can drastically decouple renewable energy generation from terrestrial land use. Policies could also incentivize circular design in solar and wind infrastructure to reduce the primary material demand and slow the rate of resource extraction. This integrated governance paradigm not only advances the sustainable management of telecoupled socio-ecological systems but also directly addresses the inequitable socio-environmental costs imposed on developing economies under current energy transition pathways.

5. Conclusions

This study integrated the telecoupling theory with multi-regional analysis to map global electricity-driven land appropriation. To our knowledge, this represents systematic comparisons of the growth rates and transnational flows of embodied land occupation driven by different energy sources, overcoming the limitations of LCA’s inconsistent metrics and MRIO’s lack of sector-specific embodied land flow analysis. Key findings reveal that embodied land use for renewable energy, 56.33% lower than that of conventional sources, grew 2.18 times faster, signaling impending land demand thresholds. China has emerged as the nexus of energy–land telecoupling, supplying 20.81% of global wind and solar land exports and 31.75% of coal-related flows, with its South–South trade share tripling since 2000. Final consumption and capital formation accounted for 82.92% of the transnational land transfers, highlighting the embedded ecological liabilities of economic growth models. While wind and solar resource heterogeneity introduce spatial variability in land coefficients, the framework identifies critical pressure points, and land-exporting regions face compounded stresses. This study had two primary limitations. First, the analysis focused on representative conventional and renewable energy sources, omitting other critical sources such as hydropower and nuclear generation, which exhibit distinct land use patterns. Second, spatial variations in geographical contexts, natural resource endowments, and technological capacities across countries are largely disregarded. Future research could leverage the land use impacts of the energy transition by utilizing more granular electricity–land intensity coefficients at both the national and municipal levels. By integrating renewable power infrastructures and land use occupation, the analytical framework developed in this study aims to advance the understanding of energy–land nexus dynamics, providing a theoretical foundation for cross-system governance in the pursuit of carbon neutrality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and M.H.; methodology, X.L., M.Y.G. and C.L.; formal analysis, X.L.; visualization, X.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., Y.L., and Y.F.; writing—review and editing, M.H.; supervision, M.H., Z.L. and G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (grant no. 22CJY020).

Data Availability Statement

The electricity generation data from 2000 to 2020 for 189 countries/economies worldwide were sourced from the International Energy Agency (IEA) database https://www.iea.org/ (accessed on 19 August 2025), and the trade data for countries around the world from 2000 to 2020 were obtained from the Eora database https://worldmrio.com/eora26/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- Matos, D.; Lassio, J.G.; Garcia, K.C.; Raupp, I.; Medeiros, A.M.; Abreu, J.L.S.; Guimarães, A.P.C. Carbon footprint of electricity transmission: Insights from a Brazilian case study. Carbon Footpr. 2025, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Roadmap for Moving to a Low Carbon Economy in 2050. 2011. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0112:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EIA. International Energy Outlook 2019; Energy Information Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Evans, A.; Strezov, V.; Evans, T. Comparing the sustainability parameters of renewable, nuclear and fossil fuel electricity generation technologies. In Proceedings of the 21st World Energy Congress (WEC) 2010, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16 September 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, L. The Footprint of Energy: Land Use of US Electricity Production; STRATA: Sydney, Australia, 2017; pp. 1–25. Available online: https://www.strata.org/pdf/2017/footprints-full (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Lovering, J.; Swain, M.; Blomqvist, L.; Hernandez, R.R. Land-use intensity of electricity production and tomorrow’s energy landscape. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Qing, Z.; Yu, Z.; Haoran, L.; Qifan, Y.; Rui, Z.; Zhoujian, A. Performance response analysis and optimization for integrated renewable energy systems using biomass and heat pumps: A multi-objective approach. Carbon Neutrality 2024, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Energy and Land Use. Available online: https://www.unccd.int/resources/publications/energy-and-land-use (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Walston, L.J.; Mishra, S.K.; Hartmann, H.M.; Hlohowskyj, I.; McCall, J.; Macknick, J. Examining the potential for agricultural benefits from pollinator habitat at solar facilities in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7566–7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffacker, M.K.; Allen, M.F.; Hernandez, R.R. Land-Sparing opportunities for solar energy development in agricultural landscapes: A case study of the Great Central Valley, CA, United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 14472–14482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruitwagen, L.; Story, K.T.; Friedrich, J.; Byers, L.; Skillman, S.; Hepburn, C. A global inventory of photovoltaic solar energy generating units. Nature 2021, 598, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Guo, M.; Zou, P.; Wu, W.; Zhou, X. Effects of photovoltaic panels on soil temperature and moisture in desert areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 17506–17518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grodsky, S.M.; Hernandez, R.R. Reduced ecosystem services of desert plants from ground-mounted solar energy development. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirwa, P.W.; Musokwa, M.; Mwale, S.E.; Handavu, F.; Nyamadzawo, G. Agroforestry systems for mitigating climate change and reducing Carbon Footprints of land-use systems in Southern Africa. Carbon Footpr. 2023, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chao, Q.; Zhao, L.; Chang, R. Assessment of wind and photovoltaic power potential in China. Carbon Neutrality 2022, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Luo, Y.; Xu, S. Deep learning method for evaluating photovoltaic potential of urban land-use: A case study of Wuhan, China. Appl. Energy 2020, 283, 116329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, E.; Adami, J.; Peluchetti, A.; Mahecha Zambrano, J. Photovoltaic potential estimation of natural and architectural sensitive land areas to balance heritage protection and energy production. Energy Build. 2023, 290, 113107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, V.; Mukhopadhyay, K. Macro-economic impacts of renewable energy transition in India: An input-output LCA approach. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, E.; Gibon, T.; Bouman, E.; Arvesen, A.; Suh, S.; Heath, G.; Bergesen, J.; Ramírez, A.; Vega-Coloma, M.; Shi, L. Integrated life-cycle assessment of electricity-supply scenarios confirms global environmental benefit of low-carbon technologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 112, 6277–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hienuki, S.; Hondo, H. Employment Life Cycle Analysis of Geothermal Power Generation Using an Extended Input-Output Model. Nihon Enerugi Gakkaishi/J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2013, 92, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miao, Z.; Huo, D.; Li, Y. A review of multi-factor footprints: A bibliometric perspective. Carbon Footpr. 2025, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rej, S.; Nag, B. Land and clean energy trade-off: Estimating India’s future land requirement to fulfil INDC commitment. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2021, 15, 1104–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fthenakis, V.M.; Kim, H.C. Land use and electricity generation: A life-cycle analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontief, W. Quantitative input and output relations in the economic systems of the United States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1936, 18, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.H.; Chen, B.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, D.; Hu, C. Coal use for world economy: Provision and transfer network by multi-region input-output analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Chen, G.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A. Mercury emissions by Beijing’s fossil energy consumption: Based on environmentally extended input–output analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubacek, K.; Sun, L. A scenario analysis of China’s land use and land cover change: Incorporating biophysical information into input-output modeling. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2001, 12, 367–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, K.; Hubacek, K.; Siu, Y.L.; Li, X. The energy and water nexus in Chinese electricity production: A hybrid life cycle analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardones, C. Economic, environmental, and social assessment of the replacement of coal-fired thermoelectric plants for solar and wind energy in Chile. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 411, 137343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.; García, A.S.; Moreno, B.; Díaz, G. Small-scale renewable power technologies are an alternative to reach a sustainable economic growth: Evidence from Spain. Energy 2018, 167, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faturay, F.; Vunnava, G.; Lenzen, M.; Singh, S. Using a new USA multi-region input output (MRIO) model for assessing economic and energy impacts of wind energy expansion in USA. Appl. Energy 2019, 261, 114141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K. Economic Analysis of Introducing Renewable Energy in a Remote Island: A Case Study of Tsushima Island, Japan. USAEE Working Paper No. 21-508. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3880819 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zhang, S.; Yu, Y.; Kharrazi, A.; Ma, T. How would sustainable transformations in the electricity sector of megacities impact employment levels? A case study of Beijing. Energy 2023, 270, 126862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerer, D.; Pratson, L. Employment trends in the U.S. electricity sector, 2008–2012. Energy Policy 2015, 82, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.Q.; Han, M.Y. Virtual land use change in China 2002-2010: Internal transition and trade imbalance. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Jiang, L.; Shen, G.Q.P. Embodied pasture land use change in China 2000-2015: From the perspective of globalization. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzettel, J.; Hertwich, E.G.; Peters, G.P.; Steen-Olsen, K.; Galli, A. Affluence drives the global displacement of land use. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Feng, K.; Hubacek, K. Tele-connecting local consumption to global land use. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Han, M.Y.; Peng, K.; Zhou, S.L.; Shao, L.; Wu, X.F.; Wei, W.D.; Liu, S.Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.S.; et al. Global land-water nexus: Agricultural land and freshwater use embodied in worldwide supply chains. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.D.; Guo, J.L.; Han, M.Y.; Chen, G.Q. An overview of arable land use for the world economy: From source to sink via the global supply chain. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Shen, G.Q.; Chen, Z.M.; Yu, R. Embodied cultivated land use in China 1987–2007. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 47, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.Y.; Chen, G.Q.; Dunford, M. Land use balance for urban economy: A multiscale and multi-type perspective. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, J.; de Groot, H.L.; Rietveld, P.; Verburg, P.H. Manifestations and underlying drivers of agricultural land use change in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Land use change and driving factors in rural China during the period 1995–2015. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Yang, X.; Han, Z.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Xie, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, B.; Fath, B.; Wang, Y. Urban sector land use metabolism reveals inequalities across cities and inverse virtual land flows. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.G. Leveraging the metacoupling framework for sustainability science and global sustainable development. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Wu, J.L.; Li, C.H.; Jia, Y.X.; Xia, X.H. Tele-connection of global agricultural land network: Incorporating complex network approach with multi-regional input-output analysis. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Bai, Y.P.; Hu, Y.C.; Deng, X.Z.; Weng, C.Y.; Shu, J.Y.; Wang, C. Tele-connecting local consumption to cultivated land use and hidden drivers in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosai, S.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Matsubae, K.; Yamasue, E. Multi-regional land disturbances induced by mineral use in a product-based approach: A case study of gasoline, hybrid, battery electric and fuel cell vehicle production in Japan. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 178, 106093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Gou, X.H.; Xue, B.; Xu, J.; Wei, Y.X.; Ma, W.J. Measuring the cross-border spillover effects and telecoupling processes of ecosystem services in Western China. Environ. Res. 2023, 239, 117291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Huang, K.; Yu, Y.J.; Qu, S.; Xu, M. Telecoupling China’s city-level water withdrawal with distant consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 4332–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.L.; Tan, Y.; Li, C.B.; Cao, Y.J.; Liu, J.G.; Schweizer, P.J.; Shi, H.Q.; Zhou, B.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.L. Energy sustainability under the framework of telecoupling. Energy 2016, 106, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.P.; Wang, Y.W.; Xuan, X.; Weng, C.Y.; Huang, X.K.; Deng, X.Z. Tele-connections, driving forces and scenario simulation of agricultural land, water use and carbon emissions in China’s trade. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 203, 107433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yang, J.L.; Feng, C.Y.; Li, Y.Z. The employment impacts of fossil fuel trade across cities in China: A telecoupling perspective. Energy 2024, 307, 132751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, H.; Rueda, X.; Mahanti, A. Transforming governance in telecoupled food systems. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Millington, J.D.; Xu, W. Trade in the telecoupling framework: Evidence from the metals industry. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlack, C.; Boillat, S.; Brönnimann, S.; Gerber, J.-D.; Heinimann, A.; Speranza, C.I.; Messerli, P.; Rist, S.; Wiesmann, U. Polycentric governance in telecoupled resourcesystems. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hoffman, L.; Diffendorfer, J.; Wiederholt, R.; Bagstad, K.J.; Thogmartin, W.E.; McCracken, G.; Medellin, R.L.; Russell, A.; Semmens, D.J. Operationalizing the telecoupling framework for migratory species using the spatial subsidies approach to examine ecosystem services provided by Mexican free-tailed bats. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.A.; Robinson, S. Data, linkages and models: US national income and product accounts in the framework of a social accounting matrix. Econ. Syst. Res. 1991, 3, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stone, R. A system of social matrices. Rev. Income Wealth 1973, 19, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World MRIO Database. Available online: https://worldmrio.com (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Katsaprakakis, D.A. A review of the environmental and human impacts from wind parks: A case study for the Prefecture of Lasithi, Crete. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2850–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denholm, P.; Hand, M.; Jackson, M.; Ong, S. Land Use Requirements of Modern Wind Power Plants in the United States; National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2009.

- Wu, X.; Shao, L.; Chen, G.; Han, M.; Chi, Y.; Yang, Q.; Alhodaly, M.; Wakeel, M. Unveiling land footprint of solar power: A pilot solar tower project in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, L. The influence of photovoltaic and nuclear energy sources on the use of land in the Czech Republic. Agric. Econ. 2022, 68, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A. Whose land is it anyway? Energy futures & land use in India. Energy Policy 2017, 110, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanseverino, E.R.; Cellura, M.; Luu, L.Q.; Cusenza, M.A.; Nguyen Quang, N.; Nguyen, N.H. Life-Cycle Land-Use Requirement for PV in Vietnam. Energies 2021, 14, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Távora, J.; Cortinhal, M.J.; Meireles, M. Land use intensity and land occupation of utility-scale photovoltaic power plants in continental Portugal. In Proceedings of the 37th European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference and Exhibition, Lisbon, Portugal, 7–11 September 2020; pp. 1975–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Planning renewable energy in rural areas: Impacts on occupation and land use. Energy 2018, 155, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvert, K.E. Measuring and modelling the land-use intensity and land requirements of utility-scale photovoltaic systems in the Canadian province of Ontario. Can. Geogr./Géogr. Can. 2018, 62, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Gouveia, J.P.; Lourenço, P.; Seixas, J. Interplay between the potential of photovoltaic systems and agricultural land use. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).