Spatial Correlation Network Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Land Use in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Evolution of Cultivated Land Protection Policies and Practices in China

3.2. Formation Mechanism of the SCN of NGLU

- (1)

- Nodes, the fundamental units of the network, refer to spatial management units such as plots, administrative villages, townships, or counties within the cultivated land system;

- (2)

- Edges, representing spatial correlations between nodes, include capital flows, technology diffusion, labor migration, material transfer, and information exchange;

- (3)

- Weight and direction, which quantify the strength and direction of correlations, such as the intensity of non-grain driving forces or the spatial reach of impacts.

- (1)

- (2)

- Industrial chain pressure and spatial contagion. Industrial transformation in core areas creates chain pressure. spreading market demand and price signals along the supply chain. This factor, combined with the imitation of micro-level decisions under the influence of information and social networks, leads to the spatial clustering of NGLU along in geographically adjacent areas, economic radiation belts, and infrastructure corridors [35,36].

- (3)

- Spillover effects and network reshaping. NGLU generates ecological, economic, and regional-level spillover effects, the intensity of which depends on node centrality. Concurrently, management entities and multi-agent governance can reshape the network structure through policy interventions, market tools, and engineering measures, thereby influencing the spatial spread of NGLU [37,38].

3.3. Measurement of NGLU

- (1)

- The planting structure index, which is measured via the ratio of the grain planting area to the total crop planting area [39].

- (2)

- The land transfer index, which is measured via the ratio of the proportion of the transferred cultivated land area used for non-grain planting to the total transferred cultivated land area [40].

- (3)

- The land use type index, determined via the remote sensing interpretation of cultivated land converted to non-grain uses (e.g., garden land and forest land). However, this approach is constrained by limited accuracy [41].

3.4. Kernel Density Estimation

3.5. SCN Analysis

3.5.1. Modified Gravity Model

3.5.2. Social Network Analysis

- (1)

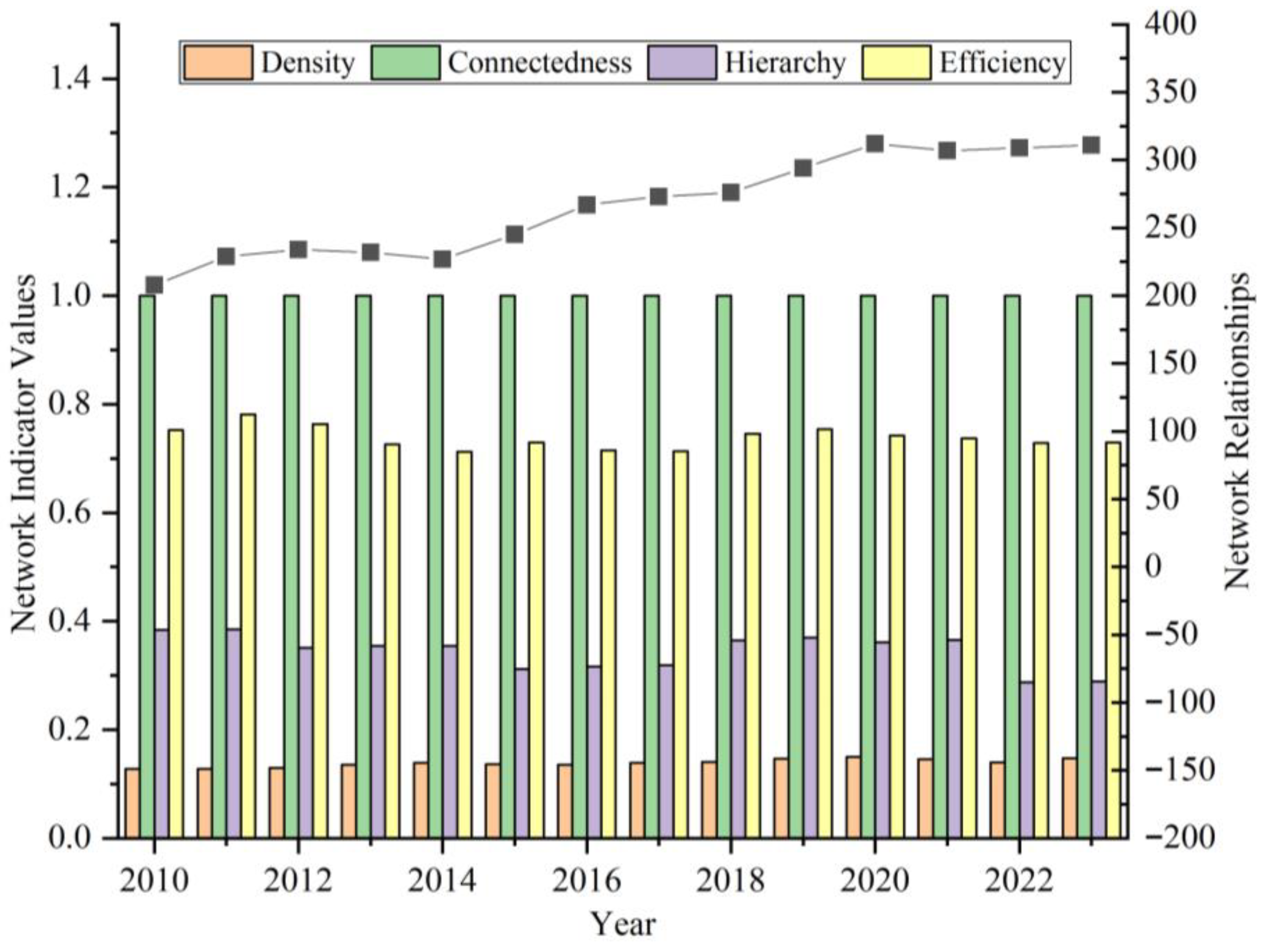

- Overall network characteristics. Overall network characteristics include network density, network correlation, network hierarchy, and network efficiency. Among them, network density measures the closeness of the non-grain spatial correlation of new cultivated land in each unit. The degree of network correlation reveals the extent of direct or indirect reachability between each unit. Network hierarchy reflects the degree of asymmetric reachability between nodes. Network efficiency evaluates the redundancy of correlation pathways within the network. The calculation formulas of these measures are as follows:where D, C, H, E represent network density, network correlation degree, network grade degree, and network efficiency, respectively; N is the number of nodes (members) in the SCN; L is the number of actual relationships between nodes; V is the number of unreachable node pairs in the network; K is the number of symmetric reachable node pairs in the network; and M is the number of redundant pathways in the network.

- (2)

- Individual network characteristics. Individual network characteristics include degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality. Among them, degree centrality measures the number of direct path connections that a node has with other nodes in the network. Closeness centrality characterizes the sum of the shortest distances between a node and all other nodes in the network. Betweenness centrality reflects the extent to which a node acts as a “bridge” on the shortest paths connecting other pairs of nodes. The calculation formulas are as follows:where DC, CC and BC are degree centrality, closeness centrality and betweenness centrality, respectively; N is the number of nodes directly associated with a given node in the network; dij is the shortest distance between city i and city j; gjk is the number of shortest pathways between city i and city k; gjk (i) is the number of shortest pathways between city i and city k that pass through city i; bjk (i) is the probability that city i lies on the shortest path between city i and city k, where j ≠ k ≠ i and j < k.

3.6. Quadratic Assignment Procedure

- (1)

- Geographical proximity (Distance): According to the first law of geography [45], spatial distance affects the cost of production factor flows and the efficiency of information transmission. Neighboring areas are more likely to imitate or compete with cultivated land use decisions implemented elsewhere. As such, geographical proximity was represented via a binary adjacency matrix, where 1 indicated a shared administrative boundary and 0 indicated the lack of such a boundary.

- (2)

- Cultivated land protection policy differences (Finance): Variations in local government regulation intensity regarding cultivated land protection may generate policy gradient effects [46]. To reflect this issue, this study used the proportion of fiscal expenditure on agriculture, forestry, and water affairs relative to total fiscal expenditure. The difference matrix was expressed via the absolute difference in the fiscal expenditure ratio between any two cities, representing the degree of difference in the investment intensity of different city governments regarding farmland protection.

- (3)

- Economic gradient difference (Econ): Regional disparities in economic development act as a key driver of cross-regional transmission of non-grain production [47]. High-gradient downstream regions may induce cultivated land use transformation in mid- and upstream areas through mechanisms such as capital outflow and demand pull. Per capita GDP was therefore used to quantify the inter-regional economic disparity. The difference matrix was expressed via the absolute difference in per capita GDP between any two cities, quantifying the gap in economic development level between cities and providing the key potential energy driving the cross-regional flow of factors.

- (4)

- Agricultural comparative benefit difference (Struct): NGLU essentially reflects profit-seeking behavior [48]. This study measured this factor via the ratio of net income per hectare from cash crops to that from grain crops, reflecting the relative incentives driving planting structure adjustment. The difference matrix was expressed via the absolute difference in income ratio between any two cities, reflecting the different levels of economic incentive intensity faced by farmers in different regions and acting as the spatial embodiment of micro-decision-making motivation.

- (5)

- Non-agricultural employment opportunity difference (Labor): The shift in rural labor to non-agricultural sectors directly influences cultivated land use intensity [49]. This was measured via the non-agricultural employment rate of the rural resident population, characterizing the weakening effect of labor loss on grain production. The difference matrix was expressed via the absolute difference in the non-agricultural employment rate between any two cities, characterizing the spatial heterogeneity of rural labor transfer pressure and directly affecting the input cost of the agricultural labor force.

- (6)

- Factor mobility intensity (Mobility): The cross-regional flow of capital and technology mediates the spatial correlation of non-grain production [50]. This was measured via the sum of the average municipal agricultural fixed asset investment (in CNY 10,000) and the average number of agricultural technology cooperation patents. The difference matrix was expressed via the absolute difference between any two cities on the composite index, which comprehensively reflects the availability differences in capital and technology, two key factors of production, between different cities.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Pattern Characteristics of NGLU

4.2. Analysis of KDE Results

4.3. The Form and Characteristics of the SCN of NGLU

4.3.1. SCN Form of NGLU

4.3.2. Analysis of the Overall Network Characteristics

4.3.3. Characteristic Analysis of Node Centrality

- (1)

- Degree centrality

- (2)

- Closeness centrality

- (3)

- Betweenness centrality

4.4. Analysis of Driving Factors of the SCN of NGLU

- (1)

- Geographical proximity. The regression coefficient for distance remained significantly positive across all years, indicating that inter-provincial geographical distance was a key factor in network formation.

- (2)

- Cultivated land protection policy implementation differences. The regression coefficients for policy implementation differences were consistently significantly negative. This implied that wider disparities in government agricultural financial support were positively correlated with the stronger spatial spillover of non-grain production. Conversely, more consistent policy implementation weakened the acquisition capacity of non-grain resources, thereby reducing spatial spillover effects.

- (3)

- Economic gradient. As its regression coefficient remained positive across all years, economic gradient disparity positively impacted on spatial correlations. This difference was found to drive NGLU through capital flows seeking profit, market demand traction, and industrial gradient transfer, jointly driving NGLU, implying that economic stratification reinforced spatial spillovers.

- (4)

- Agricultural comparative benefits. Its positive regression coefficients suggested that when the inter-regional income advantage of cash crops expanded, capital flowed from low-benefit to high-benefit areas. This capital reallocation, supported by economies of scale, accelerated the conversion of cultivated land toward non-grain use.

- (5)

- Non-agricultural employment opportunities. Differences in non-agricultural employment showed a significantly positive but fluctuating impact. The driving mechanism involved labor force loss, which accelerated land supply release and promoted large-scale capital integration. In areas with greater non-agricultural employment, cultivated land abandonment pressure increased, attracting capital from low-employment areas and driving the transition from small-scale grain production to large-scale cash crop cultivation.

- (6)

- Factor mobility. Factor mobility intensity also had a consistently significantly positive effect. The coupling of capital and technology promoted the large-scale transformation of cultivated land and strengthened spatial correlations. Enhanced regional factor interaction accelerated non-grain expansion through a dual mechanism: capital injection facilitated large-scale land circulation, while technology diffusion improved economic crop production efficiency.

5. Discussion

5.1. Overall Research Value

5.2. Comparison of Research Findings with Existing Studies

- (1)

- “Control Poles” (High-Degree Centrality): Cities such as Yingtan and Wuhan act as dominant sources of non-grain influence, exerting control through capital accumulation and policy arbitrage. This concept extends beyond simply being a “hotspot” to describe a node’s active role in driving the network.

- (2)

- “Bridging Hubs” (High-Betweenness Centrality): Cities including Changsha are identified as critical intermediaries. This finding is pivotal, as it reveals that the spatial correlation of NGLU is not a seamless surface but channeled through specific strategic conduits. These hubs amplify and direct the flow of risk, explaining why certain regions become gateways for non-grain expansion.

- (3)

- “Protective Marginalization” (Low-Closeness Centrality): The identification of cities such as Ganzi and Bozhou as marginalized nodes highlights an unintended consequence of protection policies. This concept provides a network-based explanation for the vulnerability of protected areas, which, while shielded from direct conversion pressure, may suffer from economic stagnation due to their exclusion from factor flow networks.

5.3. Comparison of Research Methods with Existing Studies

5.4. Policy Implications and Recommendations

5.4.1. Implementing “Axial Control” to Block Gradient Risk Transmission

5.4.2. Executing “Node Classification” Governance Based on Network Functions

5.4.3. Providing “Edge Support” to Enhance Network Stability

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- The spatiotemporal evolution of NGLU exhibited a clear trend of increasing risk and spatial polarization. Kernel density estimation revealed a shift from a “single peak with right skewness” to a “multi-peak coexistence” pattern, indicating a transition from point-based outbreaks to gradient transmission, primarily driven by economic disparities.

- (2)

- The SCN of NGLU became increasingly interconnected and hierarchical, with significant functional differentiation among nodes. The centrality distribution exhibited an east-led pattern with key breakthroughs in central and western regions, highly consistent with regional development gradients.

- (3)

- The formation and evolution of the SCN were shaped by multiple factors. Geographical proximity, economic gradient differences, disparities in agricultural comparative benefits, variations in non-agricultural employment opportunities, and the intensity of factor mobility all positively contributed to spatial spillovers. In contrast, differences in the implementation of cultivated land protection policies exerted a significant inhibitory effect.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cities | Number | Cities | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai | 1 | Xianning | 66 |

| Yancheng | 2 | Huangshi | 67 |

| Huaian | 3 | Suizhou | 68 |

| Zhenjiang | 4 | Shennongjia Forestry District | 69 |

| Yangzhou | 5 | Shaoyang | 70 |

| Xuzhou | 6 | Yueyang | 71 |

| Wuxi | 7 | Changde | 72 |

| Nanjing | 8 | Zhangjiajie | 73 |

| Suqian | 9 | Huaihua | 74 |

| Taizhou | 10 | Changsha | 75 |

| Lianyungang | 11 | Loudi | 76 |

| Nantong | 12 | Zhuzhou | 77 |

| Suzhou | 13 | Xiangtan | 78 |

| Changzhou | 14 | Hengyang | 79 |

| Zhoushan | 15 | Xiangxi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture | 80 |

| Quzhou | 16 | Chenzhou | 81 |

| Jinhua | 17 | Yongzhou | 82 |

| Shaoxing | 18 | Yiyang | 83 |

| Hangzhou | 19 | Chongqing | 84 |

| Lishui | 20 | Guang’an | 85 |

| Taizhou | 21 | Panzhihua | 86 |

| Huzhou | 22 | Yibin | 87 |

| Jiaxing | 23 | Zigong | 88 |

| Wenzhou | 24 | Ya’an | 89 |

| Ningbo | 25 | Deyang | 90 |

| Xuancheng | 26 | Dazhou | 91 |

| Huaibei | 27 | Luzhou | 92 |

| Tongling | 28 | Leshan | 93 |

| Bozhou | 29 | Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture | 94 |

| Huainan | 30 | Meishan | 95 |

| Chizhou | 31 | Nanchong | 96 |

| Maanshan | 32 | Chengdu | 97 |

| Anqing | 33 | Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 98 |

| Huangshan | 34 | Neijiang | 99 |

| Chuzhou | 35 | Aba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture | 100 |

| Wuhu | 36 | Ziyang | 101 |

| Lu’an | 37 | Guangyuan | 102 |

| Bengbu | 38 | Bazhong | 103 |

| Fuyang | 39 | Mianyang | 104 |

| Suzhou | 40 | Suining | 105 |

| Hefei | 41 | Liupanshui | 106 |

| Jingdezhen | 42 | Guiyang | 107 |

| Pingxiang | 43 | Anshun | 108 |

| Nanchang | 44 | Qiannan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture | 109 |

| Yingtan | 45 | Zunyi | 110 |

| Ganzhou | 46 | Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture | 111 |

| Jiujiang | 47 | Qianxinan Buyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture | 112 |

| Xinyu | 48 | Tongren | 113 |

| Ji’an | 49 | Bijie | 114 |

| Yichun | 50 | Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture | 115 |

| Fuzhou | 51 | Deqen Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 116 |

| Shangrao | 52 | Honghe Hani and Yi Autonomous Prefecture | 117 |

| Ezhou | 53 | Kunming | 118 |

| Jingmen | 54 | Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture | 119 |

| Xiaogan | 55 | Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture | 120 |

| Shiyan | 56 | Pu’er | 121 |

| Tianmen | 57 | Lijiang | 122 |

| Qianjiang | 58 | Lincang | 123 |

| Xiantao | 59 | Yuxi | 124 |

| Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture | 60 | Wenshan Zhuang and Miao Autonomous Prefecture | 125 |

| Yichang | 61 | Qujing | 126 |

| Xiangyang | 62 | Zhaotong | 127 |

| Jingzhou | 63 | Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture | 128 |

| Huanggang | 64 | Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture | 129 |

| Wuhan | 65 | Baoshan | 130 |

| NGR | Distance | Finance | Econ | Struct | Labor | Mobility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGR | 1.0000 *** | data | data | ||||

| Distance | 0.0921 ** | 1.0000 *** | data | data | |||

| Finance | 0.0374 * | −0.0152 | 1.0000 *** | ||||

| Econ | 0.0652 * | 0.2563 | −0.0013 | 1.0000 *** | |||

| Struct | 0.1637 ** | 0.3418 | 0.1045 | 0.0851 | 1.0000 *** | ||

| Labor | −0.3485 *** | 0.1445 | 0.2478 | 0.0412 | 0.1325 | 1.0000 *** | |

| Mobility | 0.2736 *** | 0.0423 | −0.0357 | 0.1584 | 0.1602 | 0.0871 | 1.0000 *** |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Distance | 3.77 | 0.265359 |

| Finance | 3.27 | 0.305442 |

| Econ | 3.05 | 0.328331 |

| Struct | 2.68 | 0.373522 |

| Labor | 1.78 | 0.562524 |

| Mobility | 1.61 | 0.621065 |

| Parameter Scenario | Network Density Range | Core Node Stability | QAP Coefficient Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic parameters | 0.127–0.147 | Benchmark | Benchmark |

| No economic weight | 0.115–0.132 | 8/10 Consistent | 5/6 variable symbols are consistent |

| Strong economic weight | 0.142–0.161 | 9/10 Consistent | 6/6 variable symbols are consistent |

| High threshold (20%) | 0.085–0.102 | 7/10 Consistent | 4/6 variable symbols are consistent |

References

- Jin, W.; He, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, X. Geospatial lnnovation Breakthroughs: A Study on the Impact of Talent Birthplace Diversity and Multidimensional Proximity. Trop. Geogr. 2025, 45, 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen, P.; Guillaume, J.H.A.; Taka, M.; D’Odorico, P.; Siebert, S.; Puma, M.J.; Jalava, M.; Kummu, M. Local food crop production can fulfil demand for less than one-third of the population. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security—A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.Y.; Wu, X.Q.; Dong, G.H. Spatial Pattern and Influencing Factors of Non-grain Cultivated Land in the Three River Basin (Yunnan Section). Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2024, 60, 893–904. [Google Scholar]

- Karina, W.; Richard, F.; Mark, R.; Martin, H. Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lv, W.B.; Xu, Z.J.; Qi, Q.Q.; Jia, M.X.; Wang, J.K.; Li, T.L. Spatial Association Networks and Factors Influencing Ecological Security in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Fu, M.Y. Degree of non-grain production of cultivated land and its impact on grain production in China: Analysis of 2481 county-level units. Land Use Policy 2025, 155, 107586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.K.; Luo, Z.J. Spatial differentiation and associated factors of non-grain cultivated land in mineral grain composite area considering scale effects. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- Chardon, V.; Herrault, P.A.; Staentzel, C.; Skupinski, G.; Finance, O.; Wantzen, K.M.; Schmitt, L. Using transition matrices to assess the spatio-temporal land cover and ecotone changes in fluvial landscapes from historical planimetric data. Earth Surface Processes Landforms. 2022, 47, 2647–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L. Impact of cropland use changes based on non-agriculturalization, non-grainization and abandonment on grain potential production in Northeast China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Q.; Ma, L. Impact of non-grain utilization of cultivated land on the technical efficiency of grain production and regional differences in major grain-consuming areas: A case study of Guangdong Province. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sonderegger, G.; Oberlack, C.; Llopis, J.C.; Verburg, P.H.; Heinimann, A. Telecoupling visualizations through a network lens: A systematic review. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.D.A.; Franks, D.W.; Brent, L.J.N.; Weiss, M.N. Accuracy and power analysis of social networks built from count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2021, 13, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartenberg, A.C.; Moanga, D.; Butsic, V. Identifying drivers of change and predicting future land-use impacts in established farmlands. J. Land Use. Sci. 2022, 17, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.; Sen, J.; Goswami, R.; Nag, P.K. Community Adaptation to Heat stress—Social Network Analysis. Clim. Risk Manag. 2024, 44, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, W.B. Accounting for the Logic and Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Comprehensive Value of Cultivated Land around Big Cities: Empirical Evidence Based on 35 Counties in the Hefei Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wu, M.; Ha, M. A county—Level estimation of renewable surface water and groundwater availability associated with potential large—Scale bioenergy feedstock production scenarios in the United States. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 606–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, R.A.; Morales, P.A.; Sanleandro, M.P. Prevalence, causes, and consequences of agricultural land abandonment: A case study in the Region of Murcia, Spain. Catena 2024, 24, 1108071. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, R.; Maiguma, K.; Yata, A.; Sano, C. Rebuilding Social Capital through Osekkai Conferences in Rural Communities: A Social Network Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.N.; Ge, X.P.; Liu, G.J.; Chen, F. Spatial Differentiation of Non-Grain Production on Cultivated Land and Its Driving Factors in Coastal China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaguno-Munitxa, M.; Bou-Zeid, E. The environmental neighborhoods of cities and their spatial extent. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 74034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Meng, F.; Yu, Z.N.; Tan, Y.Z. Spatial-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of farmland expansion in different agricultural regions of Heilongjiang Province, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.Y.; Li, Y.L.; Yang, X.C.; Guo, R.Z.; Liang, M.; Li, X. Identification of intercity ecological synergy regions and measurement of the corresponding policy network structure: A network analysis perspective. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2024, 245, 105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Yao, G.L.; Herzberger, A.; da Silva, R.F.B.; Song, Q.; Hovis, C.; Liu, J. Land-Use Changes in Distant Places: Implementation of a Telecoupled Agent-Based Model. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2020, 23, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.B.; Jiang, B.; Chen, M.K.; Bai, Y.; Yang, G.S. Strengthening the effectiveness of nature reserves in representing ecosystem services: The Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, S.A.; Keith, E.S.; Jerry, M.; Phillip, K.; Kelly, M.S. The spatial distribution of potential natural infrastructure practices in the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River Basin. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wen, Z. Review and challenges of policies of environmental protection and sustainable development in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zou, C.; Lin, N.; Qiu, J.; Pei, W.; Yang, Y.; Bao, X.; Zhang, Z. The ecological conservation redline program: A new model for improving China’s protected area network. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 131, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengnan, M.A.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Y. Construction of legal system of China’s farmland protection under the coexistence of multiple objectives: Historical logic, practical problems and optimization paths. Asian Agric. Res. 2023, 15, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China; National Development and Reform Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, R.; Liu, D.S. Spatial and Spectral Translation of Landsat 8 to Sentinel-2 Using Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, D.W.; Weiss, M.N.; Silk, M.J.; Perryman, R.J.Y.; Croft, D.P. Calculating effect sizes in animal social network analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 12, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, H.J.; Dong, H.J.; Cao, Z.J.; Zhan, R.X. Spatial association characteristics and evolutionary mechanisms of water pollution in China: A network structure dependence perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 177, 113769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.S.; Li, C.X.; Liu, J.X.; Lian, H.X.; Yamaka, W. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Spatial Association Network of Food Security Level in China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.Y.; Li, M.D.; Liu, Y.T. Study on spatial correlation network and influencing factors of environmental efficiency of major cities in Yellow River Basin. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Yu, L.H. Evaluation of marine ecological civilization construction and its spatial correlation network in China’s coastal provinces from the perspective of land-sea coordination. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1504771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shupryt, M.P.; Studinski, J.M. Spatial correlation of macroinvertebrate assemblages in streams and the implications for bioassessment programs. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Fischer, A.P.; Ager, A. A social-ecological network approach for understanding wildfire risk governance. Global Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 2019, 54, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Ke, X.L. Factors influencing farmers’ behavioral decision-making on “non-grain production” of cultivated land based on the theory of planned behavior. J. China Agric. Univ. 2023, 28, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Zhou, M.M.; He, Y.; Zhu, C.M.; Li, Y.J.; Xia, P.P. Optimizing cultivated land under non-grain expansion in rural China: Unveiling the spatial dynamics of trade-offs and synergies among ecosystem services. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 1040–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.J.; Li, H.P.; Geng, J.W.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zhu, C.H. Breaking the Boundary between Permanent Capital Farmland and Arable Land in China: Understanding State and Drivers of Permanent Capital Farmland Non-Grain Production in a Rapid Urbanizing County. Land 2024, 13, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Chen, Y.L.; Lin, J.P.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zhu, C.H. Analysis of the spatial differentiation and driving force of arable land abandonment and non-grain in the hilly mountainous areas of Gannan. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Fang, G.; Qi, C.; Gu, Y.M. Research on the Spatial Correlation Network and Driving Mechanism of Agricultural Green Development in China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, M.; Christiane, F. Hurdle-QAP models overcome dependency and sparsity in scientific collaboration count networks. J. Math. Sociol. 2024, 48, 100–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C.; Liu, Y.Q.; Wang, J.Y. Revealing the process and mechanism of non-grain production of cropland in rapidly urbanized Deqing County of China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 123948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.L.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Chen, Q.R. Does Cultivated Land Fragmentation Promote “Non-grain” Utilization of Cultivated Land: Based on a Micro Survey of Farmers in the Hilly and Mountainous Areas of Fujian. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.J.; Li, S.F.; Wu, D.F.; Song, J.; Lin, T.; Gao, Z.Y. Analysis of Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Production of Cropland in Mountainous Areas at the Plot Scale—A Case Study of Lechang City. Foods 2024, 13, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Z.; Zhang, F.R.; Li, J.; Xie, Z.; Chang, Y.Y. Unraveling patterns, causes, and nature-based remediation strategy for non-grain production on farmland in hilly regions. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, K.N.; Kaburu, S.S.K.; Marty, P.R.; Beisner, B.A.; Bliss-Moreau, E.; Arlet, M.E.; Ruppert, N.; Ismail, A.; Sah, S.A.M.; Mohan, L.; et al. Implementing social network analysis to understand the socioecology of wildlife co-occurrence and joint interactions with humans in anthropogenic environments. J. Anim. Ecol. 2021, 90, 2819–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhtoumi, Y.; Aragon, U.N.; Lark, J.T. Opportunities for water quality improvements in a Mississippi River Basin watershed: Hotspots for agricultural conservation practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 126797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Uddin, S.M.; Shah, M.J. Agrarian transformation and rural community food security in the lower Gangetic basin: A household survey dataset. Data Brief 2024, 57, 111014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.B.; Zhang, A.L.; Xiong, Y.F. Spatial differences of urban land use ecological efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt and its interactive spillover effects with industrial structure upgrading. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Liu, J.N.; Chang, Y.Y. Spatial Pattern Differentiation of Non-grain Cultivated Land and lts Driving Factors in China. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.D.; Weng, A.H. Spatial correlation network and its formation mechanism of urban water utilization efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 2353–2373. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Wang, Z.P.; Su, K.C.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, X.X.; Lin, A.W. Understanding the impact of cultivated land-use changes on China’s grain production potential and policy implications: A perspective of non-agriculturalization, non-grainization, and marginalization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 436, 140647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, X.Q. Understanding the structural imbalance in non-grain land utilization: Insights from China’s arable land policy. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 181, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhu, Y.L.; Ma, L.; Zhao, J.H. The battle of crops: Unveiling the shift from grain to non-grain use of farmland in China? Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2262752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.G.; Zhang, W.C.; Zhang, R.Q.; Zhao, Z.T.; Kong, X.B. Environmental effects and spatial inequalities of paddy field utilization are increasing in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.J.; Chen, M.Q. The status-quo and improvement path for the implementation of cultivated land protection policy in China. China Land Sci. 2020, 34, 32–37+47. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Qian, K.; Lin, L.; Wang, K.; Guan, T.; Gan, M.Y. Identifying the driving forces of non-grain production expansion in rural China and its implications for policies on cultivated land protection. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.Y.; Wu, P. Does Proximity Enhance Compliance? Investigating the Geographical Distance Decay in Vertical Supervision of Non-Grain Cultivation on China’s Arable Land? Land 2025, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Policy/Event | Content and Implications |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Plan for a New 100-Billion-Kilogram Increase in Grain Production Capacity (2009–2020) | Introduced grain production functional zones in major producing regions; shifted policy focus from quantity preservation to functional zoning. |

| 2012 | Ecological Civilization Construction Strategy (18th CPC National Congress) | Cultivated land protection extended to ecological functions; initiated ecological red line pilot in the YREB; reinforced ‘returning farmland to forest’ on sloping land |

| 2014 | Guiding Opinions on Relying on the Golden Waterway to Promote the Development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt | Accelerated industrial park construction along the river, intensifying non-agricultural pressure on cultivated land; rural land contract rights registration indirectly promoted land transfer and non-grain production. |

| 2016 | Outline of the Yangtze River Economic Belt Development + National delineation of functional zones. | Industrial expansion restricted by ‘joint protection’ policy; leisure agriculture, orchards, and sightseeing farmland expanded; delineation of food production functional zones initiated across the country |

| 2017 | State Council Guiding Opinions on Establishing Functional Areas for Grain Production and Protected Areas for Important Agricultural Products Production ([2017] No. 24) | Required provinces in the YREB to complete delineation of the “two areas” and strengthen protection of functional areas for grain production. |

| 2018 | Rural Revitalization Strategy (first year) | Intensified conflicts over cultivated land use due to rural industrial diversification (e.g., tension between grain production and poverty alleviation in Jianli, a county-level city of southern Hubei Province). |

| 2020 | State Council General Office ‘s Opinions on Preventing the Non-Grain Land Use and Stabilizing Food Production ([2020] No. 44) | First nationwide policy document raising requirements for addressing non-grain conversion; remediation plans issued by provinces, e.g., Hubei Province in February 2021. |

| 2022 | Circular on Issues Regarding the Strict Control of Cultivated Land Use ([2021] No. 166 of the Ministry of Natural Resources) | The requirement to maintain an annual “balance between the diversion and supplementation of cultivated land” through strict controls on its conversion to other agricultural uses is well-suited to China’s realities and consistent with international norms. |

| 2023 to present | Food Security Law of the People’s Republic of China (Draft) | Preventing the diversion of farmland to non-grain uses, establishing an incentive-based mechanism for cultivated land protection, and imposing strict controls on changes in cultivated land use. |

| Variable | 2010 | 2014 | 2018 | 2022 | 2023 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | 0.2853 *** (0.680) | 0.2583 *** (0.744) | 0.2950 *** (0.684) | 0.1894 *** (0.551) | 0.2846 *** (0.753) | 0.2011 *** (0.681) |

| Finance | −0.2425 *** (0.996) | −0.3295 *** (1.000) | −0.1410 ** (0.962) | −0.1167 * (0.941) | −0.1533 ** (0.797) | −0.2188 *** (0.994) |

| Econ | 0.1385 *** (0.902) | 0.1479 *** (0.388) | 0.1260 * (0.932) | 0.1032 ** (0.021) | 0.1679 *** (0.150) | 0.2217 ** (0.985) |

| Struct | 0.1173 ** (0.024) | 0.1520 *** (0.002) | 0.1291 *** (0.003) | 0.1423 *** (0.047) | 0.1751 *** (0.078) | 0.1188 ** (0.016) |

| Labor | 0.2225 *** (0.992) | 0.1708 ** (0.982) | 0.1033 * (0.924) | 0.3249 *** (0.968) | 0.2522 *** (0.772) | 0.1631 ** (0.968) |

| Mobility | 0.2337 ** (0.976) | 0.2187 *** (0.993) | 0.3001 *** (1.000) | 0.3147 *** (0.997) | 0.1723 *** (0.818) | 0.2407 ** (0.972) |

| R2 | 0.115 | 0.163 | 0.122 | 0.116 | 0.258 | 0.177 |

| Adj-R2 | 0.111 | 0.159 | 0.117 | 0.112 | 0.256 | 0.172 |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Observation | 980 | 980 | 980 | 980 | 980 | 980 |

| Permutation | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 | 6000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Ye, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M. Spatial Correlation Network Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Land Use in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2025, 14, 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112149

Wang B, Ye Q, Li L, Liu W, Wang Y, Ma M. Spatial Correlation Network Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Land Use in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land. 2025; 14(11):2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112149

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bingyi, Qiong Ye, Long Li, Wangbing Liu, Yuchun Wang, and Ming Ma. 2025. "Spatial Correlation Network Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Land Use in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China" Land 14, no. 11: 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112149

APA StyleWang, B., Ye, Q., Li, L., Liu, W., Wang, Y., & Ma, M. (2025). Spatial Correlation Network Characteristics and Driving Mechanisms of Non-Grain Land Use in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land, 14(11), 2149. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14112149