1. Introduction

Social stability is a prerequisite for sustained economic and social development, and disputes among farmers are a significant factor affecting stability in rural areas. When village conflicts are appropriately managed, they can be resolved before escalation; conversely, poorly addressed disputes may lead to farmer petitions, mass incidents, or repeated legal cases, posing a significant threat to rural social stability. Currently, disputes among Chinese farmers exhibit the following salient characteristics. First, most conflicts occur within villages. Second, land-related disputes account for the highest proportion [

1]. As the fundamental resource underpinning farmers’ livelihoods and development, land in traditional rural societies carries not only economic attributes but also substantial social and emotional significance. Rights over land—including its use, location, and boundaries—directly impact farmers’ wealth and social status, affecting critical life domains such as education and marriage. However, in many rural areas of China, land boundaries have become increasingly ambiguous over time, ownership is often complex, and contracted land certificates often fail to match actual plots. Recent village consolidations and reorganizations have further compounded these legacy issues, contributing to frequent boundary disputes [

2]. Moreover, farmers’ strong emotional attachment to their land makes it difficult for them to relinquish land management rights, even amid rising income or shifts in occupational structures. This intertwined economic and emotional “land complex,” when coupled with resource constraints and heightened conflict intensity, increases the likelihood that unresolved civil disputes will escalate into criminal cases [

3].

Research on land rights certification has predominantly focused on its economic implications, emphasizing outcomes such as farmer investment, factor allocation, and agricultural output. Enhanced security and tradability of land rights are widely considered key mechanisms through which agricultural land rights certification and registration promote farmer investment [

4]. As a crucial measure to strengthen land property rights, certification effectively facilitates land transfers [

5]; reduces resource misallocation; and advances contiguous, large-scale farming operations [

6]. Simultaneously, land rights confirmation encourages labor mobility [

7] by removing distortions in individuals’ occupational choices between agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, thereby significantly boosting agricultural productivity [

8]. By increasing investments in both physical and human capital, land rights confirmation also serves as a vital tool for poverty alleviation and provides strong incentives for entrepreneurial activities among farmers [

9,

10].

At the social level, land rights confirmation contributes to gender equality and social stability. Empirical evidence indicates that women face greater disadvantages in land distribution. By enabling women to acquire and control land, land rights confirmation strengthens their bargaining power in household resource allocation, providing an important pathway for development through women’s empowerment [

11]. Nevertheless, some studies also indicate that while China’s Rural Land Contract Law has enhanced land property rights security, it has, to some extent, exacerbated gender disparities in non-agricultural employment [

12]. Ambiguous land property rights are a major source of conflict among farmers. International evidence underscores that clear property rights can reduce the incentives for violent behavior, thereby lowering the incidence of disputes. For instance, Mexico’s land property rights reform demonstrates that well-defined property rights diminish the benefits of violent actions [

13]. Furthermore, studies in Bangladesh and Ethiopia show that households with registered land parcels experience fewer unresolved disputes, and land tenure security programs significantly reduce the probability of conflicts arising from land boundary issues [

14,

15,

16]. Stable land tenure thus lowers the likelihood of conflicts between households and mitigates the negative impacts on families [

17]. Regarding the effects of China’s agricultural land tenure confirmation on village-level disputes, no definitive conclusions have yet been reached. Some studies indicate that the new round of land tenure confirmation has substantially reduced the probability of conflicts between villagers and local committees, enhancing farmers’ trust in both central and village-level authorities [

18,

19]. Zhang et al. [

20] further found that land rights confirmation reduces the incidence of village crime. Clear land rights diminish conflicts over land among ordinary farmers, thereby fostering mutual assistance [

21]. Conversely, Qu et al. [

22] observed that land rights confirmation has sometimes brought historical issues to the fore, triggering new conflicts and disputes.

Property rights economics posits that resource scarcity inevitably generates conflicts of interest among individuals, which can be resolved through clearly defined property rights. Beyond providing incentives that influence economic behavior, property rights delineate the principal actors in economic activities, thereby shaping the distribution of social wealth [

23]. As stated, “Those with permanent property have steadfast hearts; those without permanent property have no steadfast hearts. Without steadfast hearts, they will indulge in extravagance and depravity, sparing no vice.” Therefore, clearly defined and secure land property rights not only are fundamental to farmers’ economic security but also serve as a crucial foundation for promoting rural social stability. Thus, a rigorous examination of how secure rural land property rights affect rural conflicts holds both significant theoretical value and practical significance for mitigating disputes, advancing rural governance, and promoting comprehensive rural revitalization.

The marginal contributions of this study are primarily reflected in the following aspects: (i) By exploiting the policy shock associated with the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation, it examines the impact of agricultural land property rights reform on rural social conflicts and disputes, thereby enriching the literature on the social effects of such reforms. (ii) From the perspective of rural disputes and conflicts, it explores the mechanisms through which secure agricultural land property rights affect rural conflicts and disputes, offering deeper insights into issues of rural social governance. (iii) It examines the heterogeneity of the reform’s impact on rural conflicts across villages with differing levels of clan influence, income disparities, and suburban status, thereby enhancing our understanding of policy outcomes and providing empirical evidence for the optimization of related policies.

2. Policy Context and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Policy Context

China’s rural land institutions have undergone several rounds of reform aimed at unleashing productive forces, promoting agricultural development, and maintaining social stability. The early 1980s marked the institutional breakthrough of the Household Contract Responsibility System, which separated collective land ownership from household contracting rights and dramatically increased agricultural productivity. To ensure long-term stability, a second round of land contracting was initiated in 1993, extending the contracting period for another 30 years. This laid the foundation for the confirmation, registration, and certification of land rights, later codified in the Rural Land Contract Law (2002) and reinforced by the Property Law (2007). These reforms gradually clarified the legal status of rural land rights and strengthened the security of household contracting arrangements.

Following the abolition of agricultural taxes in 2006, rapid industrialization and urbanization fueled large-scale labor migration from rural areas, accelerating labor specialization and diversification. This process also intensified the transfer of contracted management rights, yet the limited accuracy of existing registries often created disputes over plot sizes and boundaries. These challenges highlight the urgency of strengthening land rights confirmation. In response, the central government gradually advanced a new round of land contracting rights reforms. Beginning with small-scale village-level trials in 2009, the initiative was quickly scaled up through multi-ministerial pilot programs, eventually extending to a national scope within just a few years. The 2013 Central Rural Work Conference marked a critical turning point, when the leadership explicitly underscored the need to complete land rights registration and certification nationwide to secure farmers’ contracting rights. Subsequent years saw this reform move from county-level pilots to province-wide implementation, accompanied by a steady institutionalization of registration and certification procedures. By the mid-2010s, the establishment of a unified and reliable land contracting rights registration system had become a cornerstone of China’s rural land governance, aiming not only to stabilize land tenure but also to safeguard farmers’ economic security and facilitate rural revitalization.

The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation in China represents a large-scale land titling program aimed at enhancing land tenure security. It was not intended to establish a new contracting system, but rather to consolidate and refine existing arrangements. Building on the second-round land contracts and registry records, the reform sought to clarify plot boundaries, secure farmers’ usufruct rights, and institutionalize property rights protection through registration and certification. By September 2020, the program had been implemented in nearly all counties nationwide, covering more than 200 million farm households. In addition to strengthening tenure security, the reform resolved hundreds of thousands of land-related disputes and addressed longstanding historical problems, thereby reinforcing the institutional foundation of rural stability and governance.

Compared with previous rounds of property rights reforms, the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation is unique in the following five respects: First, it is characterized by strong government leadership and top-down implementation, ensuring comprehensive and effective policy enforcement. Second, land parcel boundaries are defined with greater precision. The reform mandates the full implementation of the “four household-level requirements”—contracted land parcels, area, contracts, and certificates—using advanced technologies like drones and BeiDou satellites to clearly delineate farmers’ land boundaries. Standardized procedures, including data collection, base map creation, field surveys, office processing, public notice, signature confirmation, and certification review, have resolved long-standing issues such as inaccurate land parcels, unclear boundaries, imprecise areas, and ambiguous ownership. Third, legal safeguards for land ownership rights have been reinforced. The establishment of a comprehensive registration and certification system has both constrained village collectives and enhanced farmers’ property rights protection, thereby encouraging greater participation in land transfers and enabling the use of land management rights as collateral. Fourth, land rights information has been digitized and archived, with an information application platform created to facilitate verification, transactions, and integration with the unified real estate registration system. Finally, the process is institutionally rigorous and relatively lengthy. This round of confirmation is managed at the county and township levels, typically requiring one and a half years to complete all procedures from mobilization, surveying project bidding, and field investigations to final registration, certification, and data integration [

24].

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Property rights economics distinguishes between the allocation of property rights and their enforcement, emphasizing that both clear entitlements and the ability of rights holders to exercise their property rights are equally important. A well-functioning property rights system operates along two dimensions. It requires governments to clearly define and enforce property rights, reducing violations by market participants, thereby lowering transaction risks and costs. The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation strengthens property rights at the definition level by granting farmers exclusive, contract-based claims to land while also stabilizing expectations. At the enforcement level, the precise delineation and registration of parcels provide a concrete basis for resolving disputes in the context of land transfers or expropriations. Empirical evidence supports this mechanism, showing that clear land rights reduce the likelihood of boundary disputes among farmers and mitigate the adverse impacts of conflicts on households [

15,

16]. Stable land property rights not only lower the likelihood of conflicts between households but also mitigate the damage conflicts inflict on families [

17]. Based on this, Hypothesis 1 is proposed.

H1: The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps reduce conflicts and disputes within villages, thereby promoting rural social stability.

Unstable farmland contracting rights undermine marginal land productivity and decrease agricultural operating income [

25]. By enhancing security, land property rights reforms incentivize farmers to invest in physical and human capital, thereby fostering income growth and poverty reduction, and even alleviating intergenerational poverty [

9,

26]. As a central component of such reforms, the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation is expected to improve farmers’ income and welfare by increasing agricultural productivity and total output while reallocating labor from agriculture to non-agricultural sectors [

27,

28]. Land rights confirmation increases farmers’ likelihood of remaining engaged in farming and stimulates their willingness for long-term investment [

29]. This encourages land improvements, the adoption of modern cultivation techniques, and the purchase of agricultural machinery, thereby raising per-unit land output and agricultural operating income. However, it is difficult to increase farmers’ income through indirect channels [

30]. As the saying goes, “When granaries are full, people know propriety.” Poverty often breeds crime and disputes [

31]. Therefore, by improving agricultural operating income, the new round of land rights confirmation can reduce village-level disputes.

Richard Thaler’s endowment effect theory argues that individuals assign a higher value to an asset once they own it compared with when they do not [

32]. Accordingly, land rights confirmation strengthens farmers’ endowment effect, elevating their perceived and actual valuation of land, thereby driving up land rent levels [

33]. This effect is reinforced not only by economic logic but also by Chinese farmers’ unique emotional attachment to their land. By strengthening property rights over farmland, land rights confirmation increases village land rental rates [

5]. Higher land rents directly raise farmers’ income, promote fairer distribution of land transfer profits, and reduce conflicts among contracting parties. When rental levels converge with farmers’ perceived land value, their satisfaction improves, thereby decreasing disputes over contract execution. In addition, higher land rents incentivize broader participation in land transfers, increasing land utilization efficiency and reducing ownership disputes caused by long-term idleness due to ambiguous land boundaries. The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps raise land rents, thereby enhancing farmers’ bargaining power and leading to fewer village disputes. Based on this, Hypotheses 2 and 3 are proposed.

H2: The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps increase farmers’ agricultural operating income, thereby reducing rural conflicts and disputes.

H3: The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps increase land rents, thereby enhancing farmers’ bargaining power and reducing conflicts and disputes arising from this.

The primary function of property rights systems is to protect citizens from government and elite predation, providing the security of expectations necessary for investment and economic activity [

34]. Under China’s current Household Contract Responsibility System, the state occupies a dominant role in land property rights arrangements. However, ambiguous land tenure relationships diminish farmers’ perceived security, often leading to property rights violations and land disputes [

35,

36]. Amid a constrained supply of state-owned land, the urbanization process entails expropriation of rural land, particularly when agricultural property rights are poorly demarcated. According to the current

Land Administration Law (revised in 2019), “the state may lawfully expropriate or requisition land for public interest purposes and provide compensation,” and “the state implements a system of paid use for state-owned land.” Under these provisions, expropriated farmland shifts from collective to state ownership, enabling the government to transfer land use rights on a paid basis [

23]. This process generates asymmetric incentives, whereby government actors may pursue profit-seeking behavior. Farmers involved in land transactions frequently experience disputes that, in some cases, escalate into severe confrontations or even criminal incidents. Such disputes aggravate uncertainty over land tenure, erode agricultural productivity, and pose substantial risks to social stability [

37]. The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation has strengthened the security and enforceability of property rights, reduced the scope for arbitrary government land expropriation, safeguarded farmers’ rights and interests, and consequently reduced disputes. Based on this, Hypothesis 4 is proposed.

H4: The new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps reduce the area of land expropriated by the government, decrease property rights infringements, and thereby reduce the occurrence of village conflicts and disputes.

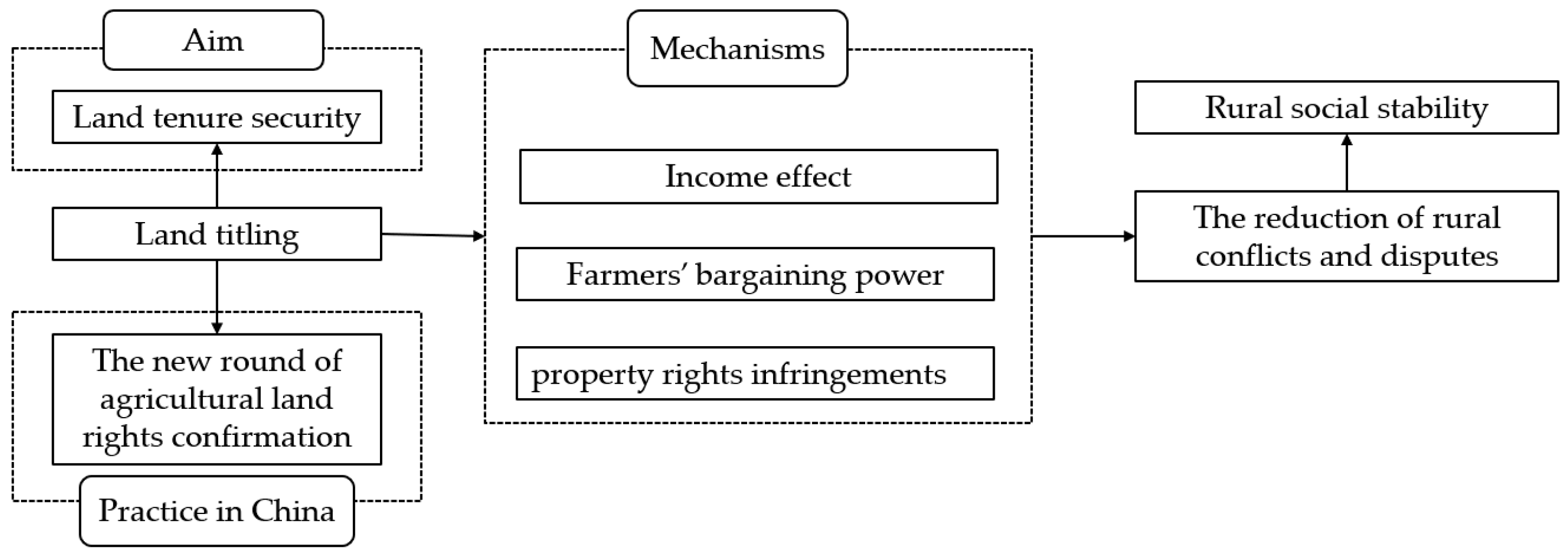

Drawing on the literature on property rights and rural conflicts and disputes, we construct a theoretical framework to clarify how the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation affects rural social stability (

Figure 1).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

To construct the core explanatory variable, this study manually collected and coded the initial year of the new round of rural land rights confirmation from official county (district) government websites. A county (district) was coded as 1 in the year when government documents, work reports, or press releases indicated the commencement of confirmation, registration, and certification of rural land contract management rights, and 0 in all prior years. We treat the initial timing of villages in the same way as the initial timing of their affiliated counties.

Other data used in this article are sourced from the National Fixed-Point Survey (NFPS) conducted by the Research Center for Rural Economy (RCRE) of the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs since 1986. The NFPS follows a nationally representative sample of over 20,000 registered households in 375 sample villages across all 31 of China’s mainland provinces. The NFPS villages were selected for representativeness based on region, income, cropping pattern, population, and non-farm activity. Within each village, 50–100 households are randomly chosen to participate in an annual survey. Respondent households are required to keep detailed diaries of income, expenditures, and labor activities, which are collected monthly by resident enumerators. This rigorous design ensures high-quality data and minimizes reporting and measurement errors. For comparability, our analysis uses data from 2013 to 2021.

The NFPS is composed of three complementary sub-surveys: a village survey, a household survey, and an individual (household member) survey. The village survey, completed by local officials, collects information on local socio-economic conditions. The household survey, administered to household heads, records detailed data on agricultural production at the crop level, including inputs and outputs. The individual survey, also completed by household heads, provides information on labor allocation, as well as demographic and socio-economic characteristics of household members.

Since our purpose is to analyze the effects of land titling on rural disputes, we adopt the following procedures to acquire a sample of villages from rural China. First, we drop villages from the pilot reform regions (Sichuan Province) [

24], which equates to 2 villages in the sample. Second, we drop villages located in municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing), as their industrial structures are relatively disengaged from primary-sector activities, which may bias the analysis. Third, we identify the location of each village based on its province and village IDs and then match it with the timing of the new round of land titling.

3.2. Definition of Variables

1. Dependent variable: The number of civil disputes. In the benchmark regression analysis, this study employs the number of civil disputes occurring within a village during the year as a proxy for the explained variable,

rural conflicts and disputes. This approach differs from the methodology employed by Zhang et al. [

20], who utilized indicators such as whether a village experienced criminal incidents, the number of offenders, and crime rates. The distinction reflects the fact that most rural conflicts and disputes manifest as civil disputes, with fewer escalating into criminal cases. Accordingly, the number of civil disputes provides a more accurate measure of conflict intensity. To mitigate heteroskedasticity and potential estimation biases arising from extreme values, the variable

number of civil disputes occurring within the year is log-transformed in the empirical analysis.

2. Core explanatory variable: Land titling. Building on the policy shock provided by the new round of rural land rights certification, this study constructs the core explanatory variable to capture the causal impact of land titling. Specifically, for 2013–2021, villages that implemented the registration and certification of rural land contract management rights are coded as 1, forming the treatment group, while villages that did not implement these procedures are coded as 0, constituting the control group. This coding approach leverages the staggered rollout of the policy across villages, enabling a quasi-natural experimental design to identify the effects of secure land tenure on rural conflicts and disputes.

3. Control variables. To isolate the effect of the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation on rural conflicts, this study includes village-level controls covering demographic, economic, and geographic factors. Demographic characteristics include labor force educational attainment (proportion with high school education or above), proportion of male residents, and share of religious adherents [

38]. Religious affiliation (including Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions) reflects additional sources of potential conflict. Village economic characteristics encompass the average cultivated land area per household, internet access rate, and proportion of impoverished households. Internet access is a key indicator of village informatization, fundamentally enhancing rural communities’ capacity to obtain timely information on policy updates, legal procedures, and market conditions. In the context of land rights confirmation, improved internet connectivity enables villagers to access official announcements on certification processes, clarify property rights regulations, and obtain transparent information disclosed by government agencies. Enhanced information accessibility facilitates more informed decision-making and reduces information asymmetries that often underlie misunderstandings and disputes over land boundaries and ownership claims [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Moreover, internet access allows villagers to independently verify land-related information and engage more effectively with formal grievance mechanisms, thereby mitigating conflicts stemming from incomplete or distorted information [

43,

44]. Geographic characteristics primarily refer to distance to major highways and water scarcity conditions, the latter serving as a proxy for drought and limited water availability. Water availability is one of the most critical determinants of agricultural income, directly influencing crop yields, farming intensity, and household economic stability. In water-scarce villages, agricultural productivity and income levels tend to be significantly lower and more volatile, which can intensify economic pressures on rural households [

45]. These economic stresses may heighten sensitivities over land allocation and usage rights, thereby increasing the likelihood of land-related disputes. Exceptionally dry weather conditions intensify competition for water resources, potentially triggering small-scale social conflicts [

46]. By controlling for water scarcity, we capture a fundamental source of variation in agricultural income that may independently affect dispute propensity, allowing for a more precise estimation of the effects of land rights confirmation on social stability.

4. Mechanism variables. To investigate the pathways through which the new round of rural land rights confirmation affects rural conflicts and disputes, this study constructs three mechanism variables, which are incorporated into regression models. (i) Income effect. This study uses the household’s agricultural operating income in the year of land rights confirmation to measure potential increases in household income resulting from enhanced land tenure security. Including this variable can determine whether income gains mediate the policy’s effect on reducing disputes. (ii) Farmers’ bargaining power. This is proxied by the average land rental income of all households within a village, reflecting village-level land rents and households’ relative bargaining capacity in the land market. This variable captures the extent to which strengthened property rights enhance farmers’ leverage in land transactions, thereby potentially mitigating conflicts. (iii) Property rights infringement. This study uses the ratio of government-acquired land area to total cultivated land area in the village to measure the extent of land expropriation, serving as a proxy variable for property rights infringement. Incorporating this variable can determine whether reducing expropriation and related infringements is a key mechanism through which land rights confirmation reduces rural disputes.

Variable definitions and descriptive statistics are presented in

Table 1.

3.3. Descriptive Overview

We present descriptive statistics and visualizations of key variables over time. Specifically, we examine the temporal patterns of both the outcome variable and core explanatory indicators across the study period. These figures illustrate both the baseline levels and the evolving trajectories of village-level disputes and policy implementation, offering preliminary insights into potential policy effects. The descriptive trends also contextualize the empirical strategy by highlighting variations in exposure timing and outcome dynamics prior to formal modeling.

1. Temporal Patterns of Disputes and Land Titling Implementation.

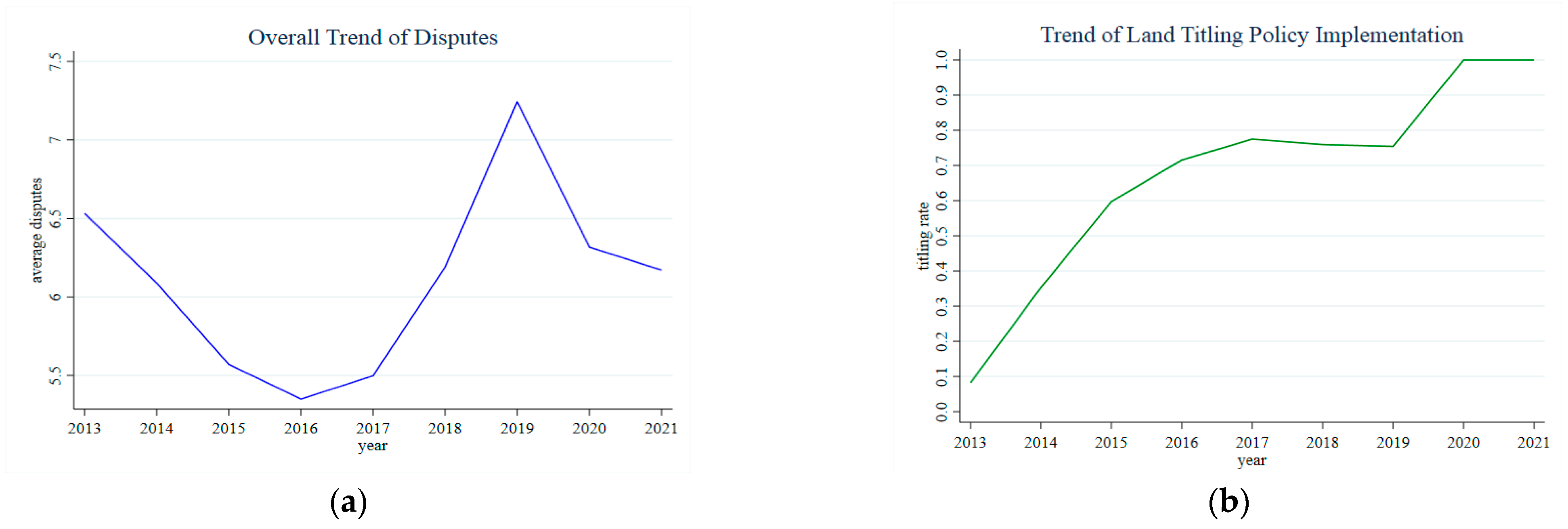

Figure 2 depicts temporal trends for the primary outcome and treatment variables.

Figure 2a illustrates the average number of village-level civil disputes from 2013 to 2021, exhibiting a non-linear pattern: a decline until 2016, followed by a sharp increase in 2019, and then a gradual decrease thereafter.

Figure 2b presents the cumulative implementation rate of the land titling policy, which rose over time and reached full coverage by 2020. Notably, the period of rising dispute levels—particularly between 2017 and 2019—coincides with slower policy expansion. This temporal alignment suggests that delays or uneven progress in policy implementation may have contributed to heightened social tensions, thereby providing preliminary motivation for the identification strategy developed in the following sections.

2. Comparative Trends in Rural Civil Disputes: Treatment vs. Control Group.

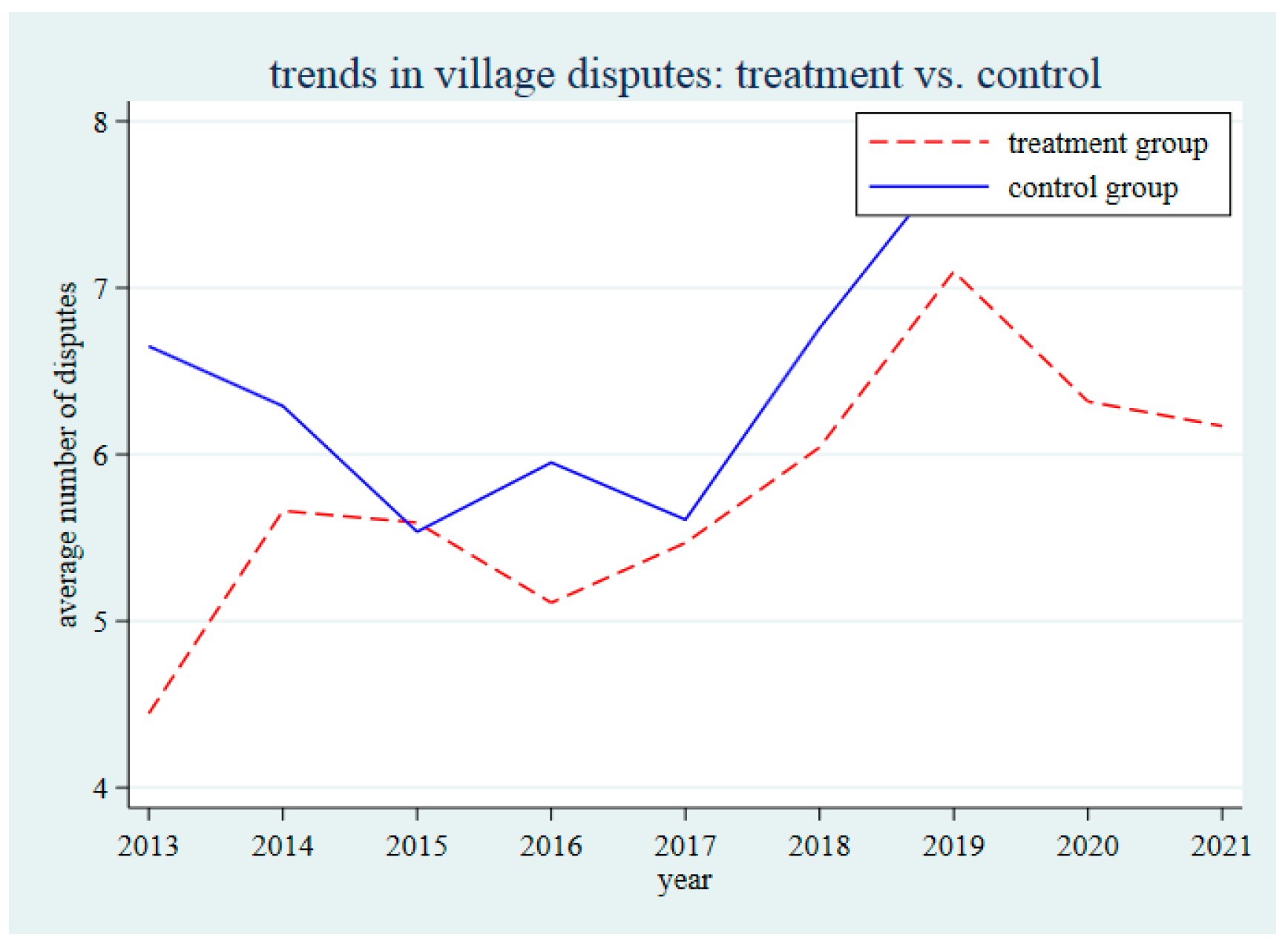

Figure 3 presents the descriptive trends in the average number of rural civil disputes for villages that have completed land titling (treatment group) and those that have not yet completed titling (control group) in each year from 2013 to 2021. Under the staggered DID framework, villages enter the treatment status in different years as the policy is gradually rolled out, resulting in a dynamic composition for the treatment group over time. Since all villages had completed land tenure confirmation by 2020, no control group exists beyond that year. Throughout the observation period, the control group generally exhibits more disputes than the treatment group, especially in the later years. This descriptive evidence provides an intuitive overview of the evolving differences between treated and untreated villages during the policy rollout process. While not intended as a causal test, this offers useful context and preliminary support for the subsequent staggered DID analysis.

3.4. Modeling

Given that the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation is being implemented through a phased, pilot-first approach, this study employs a staggered difference-in-differences (DID) model to identify its impact on rural conflicts and disputes. The specific model specification is as follows:

In Equation (1), i and t denote village and year, respectively. The dependent variable, disputeit, represents the number of dispute cases in village i during year t, serving as a measure of rural conflicts. The core explanatory variable, titlingit, denotes the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation. controlit is a set of control variables that may influence disputes, encompassing various village-level characteristics. μi is the village-level fixed effect, controlling for village-level heterogeneity that does not change over time. λt denotes the time fixed effect. εit represents the random disturbance term. Clustered standard errors are used at the village level during model estimation. β1 is the core coefficient of interest in this study, reflecting the average treatment effect of the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation on rural conflicts and disputes.

To investigate the specific pathway by which land titling impacts rural disputes, this study employs the methodology proposed by Jiang [

47]. The model for testing the specific mechanism is outlined as follows:

where

Mit denotes the mechanism variable, and

titlingit represents the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation, consistent with Equation (1).

controlit is a vector of control variables, and

μi denotes the household- or village-level fixed effect, depending on the data used for each mechanism, controlling for household- or village-level heterogeneity that does not change over time.

λt denotes the time fixed effect.

εit represents the random disturbance term.

Mit is measured by three distinct indicators: household agricultural operating income, farmers’ bargaining power, and property rights infringements. For the first mechanism, household-level control variables are included to account for heterogeneity in socio-economic characteristics. For the second and third mechanisms, the empirical specification and control variables are consistent with the baseline regression, using village-level data to capture village-level heterogeneity.

3.5. Diagnostic Tests

To assess the robustness and reliability of the staggered DID estimates, we implement a series of diagnostic tests, including the parallel trend test and placebo tests.

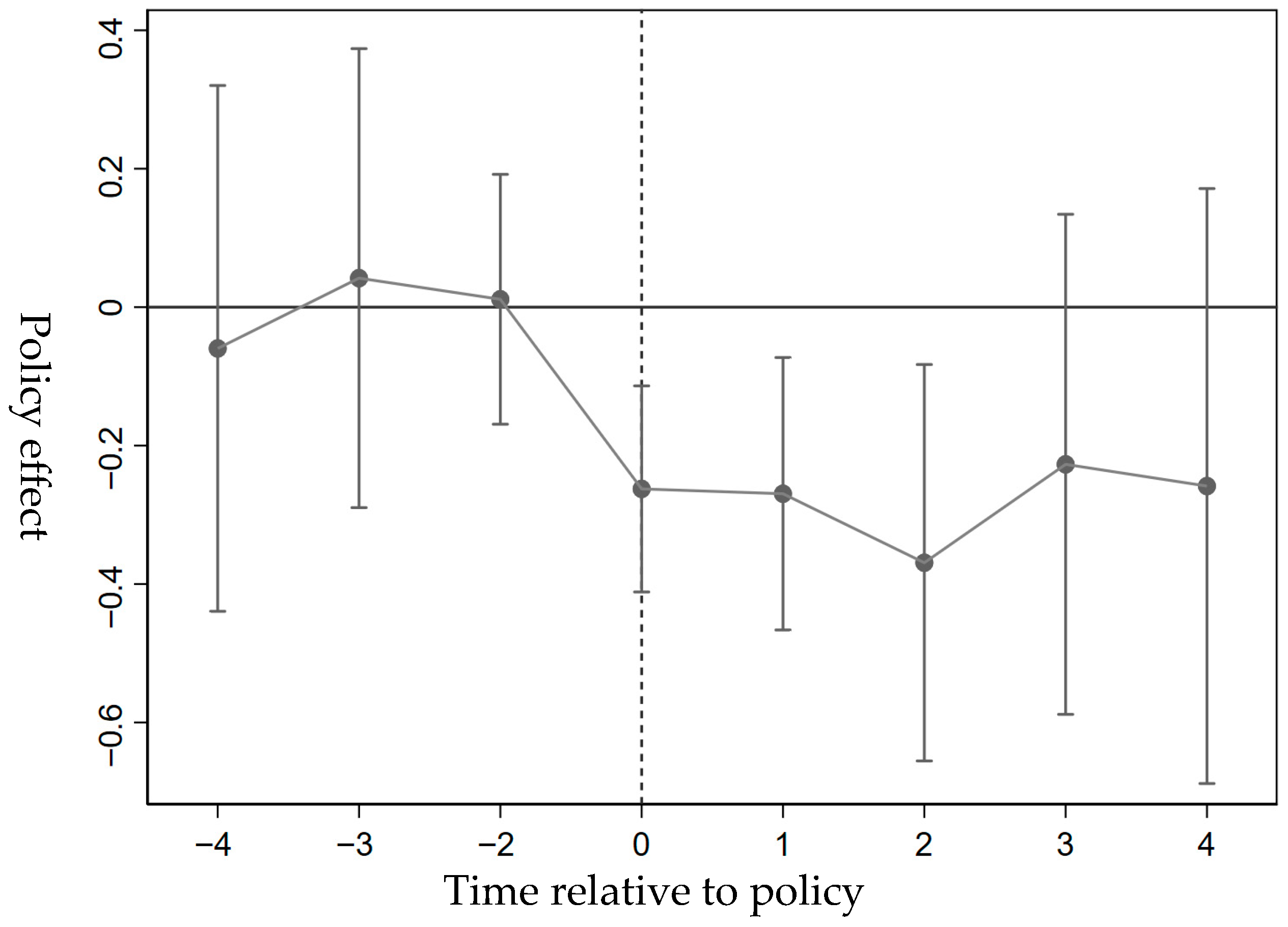

1. Parallel Trend Test. Following the event–study approach used by Beck et al. [

48], we estimate the following specification by interacting leads and lags in the treatment variable with year dummies:

where

k = −1 (one year prior to the policy of land titling) serves as the omitted reference period. The coefficient

βk captures the dynamic effects of the policy relative to this baseline year. The 95% confidence intervals for the pre-treatment periods include zero, indicating no statistically significant differences between treated and control villages prior to the policy. This supports the parallel trend assumption underlying the staggered DID estimation.

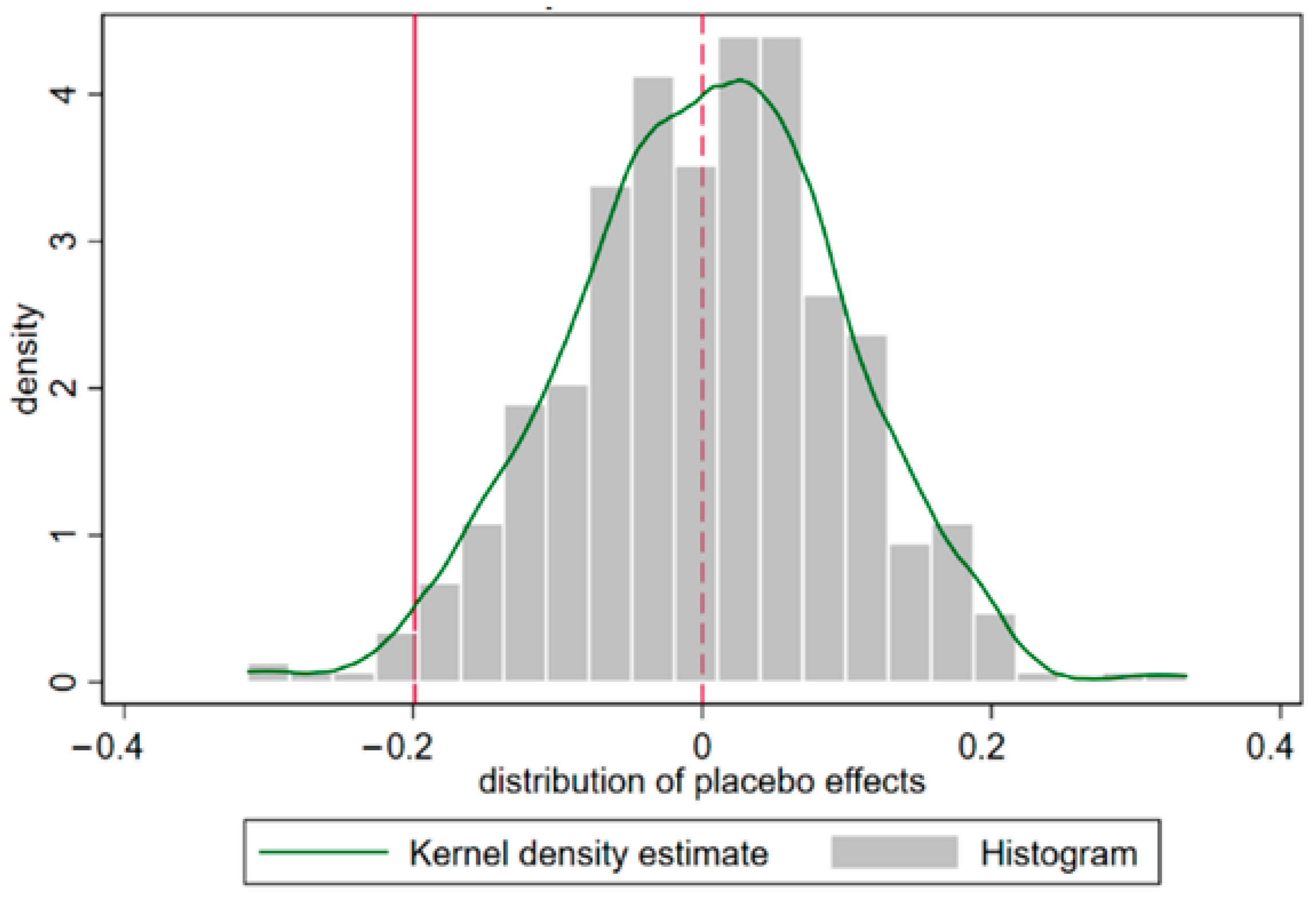

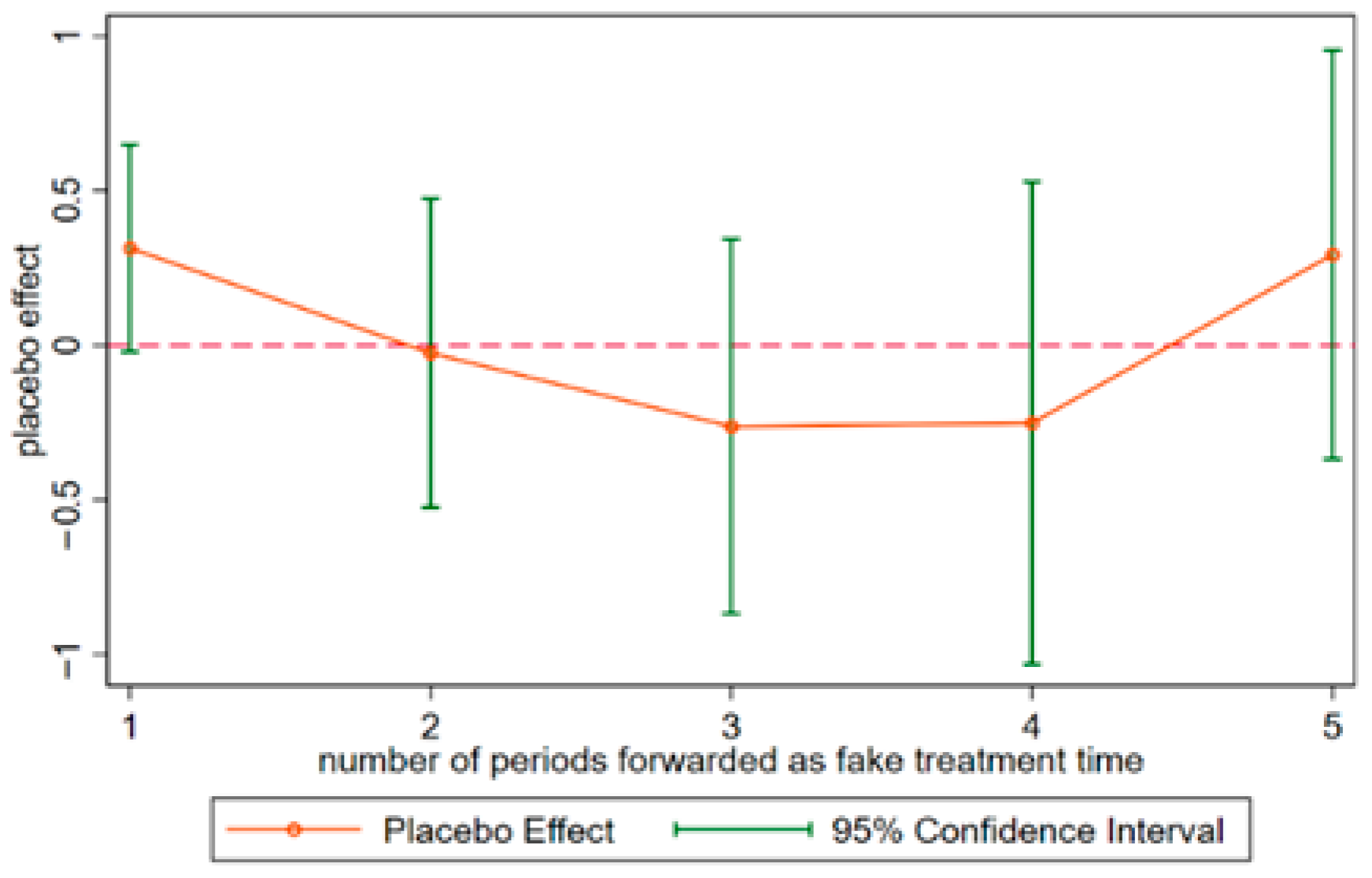

2. Placebo Tests. We perform placebo tests to rule out the possibility that the estimated effects are influenced by spurious correlations or time-varying confounders rather than the policy itself, following Chen et al. [

49]. First, we conduct a placebo test using the pseudo-treatment group approach. Several are randomly drawn without replacement from the sample as “pseudo-treatment units”, and a DID estimation is performed to obtain placebo effect estimates. This procedure is repeated 500 times to generate the distribution of placebo effects. If the true treatment effect is zero, the estimated effect should not appear extreme relative to this distribution. Right-tailed, left-tailed, and two-tailed

p-values are then calculated. A

p-value below 0.05 allows us to reject the null hypothesis of the zero-treatment effect, indicating that the estimated effect is statistically significant. Second, we adopt a time placebo test, in which a fictitious policy implementation date is assigned to a pre-treatment period. Estimating the DID model using this fake treatment time allows us to test whether significant effects would arise in the absence of actual policy interventions. Statistically insignificant placebo estimates provide evidence that the baseline results are not contaminated by pre-existing trends. Finally, we also implement a mixed placebo test. In this process, several are randomly drawn without replacement from the sample as “pseudo-treatment units”, and a common “pseudo-treatment time” is randomly assigned for the DID estimation, yielding a placebo effect estimate. This process is repeated 500 times to generate the distribution of placebo effects. The subsequent steps for the combined placebo test are identical to those of the pseudo-treatment group approach.

5. Discussion

Land titling is not only a key instrument for agricultural productivity and resource allocation but also plays a critical role in maintaining rural social stability. This study investigated the role of land titling for rural stability. Our findings are an important reference for countries with many rural conflicts and disputes.

The empirical findings of this study demonstrate that the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation significantly reduces rural conflicts and disputes. This effect primarily operates through three channels. First, land titling enhances household agricultural operating income, strengthening the economic foundation of farmers and thereby alleviating conflicts and disputes. Second, clarified land rights improve land rents, thereby enhancing farmers’ bargaining power in negotiations, contract agreements, and land use arrangements, which helps prevent and resolve potential conflicts and disputes. Third, the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation reduces property rights infringements, such as unauthorized land occupation or contract violations, directly lowering the likelihood of conflicts and disputes.

The impact of the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation varies across village contexts. In villages with balanced clan power, clarified land rights can effectively mediate internal power dynamics, reducing disputes stemming from intra-clan tensions. In villages with larger income disparities, the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation helps protect the rights of lower-income households, mitigating social tensions. The effect is also more pronounced in non-suburban villages, likely due to weaker urban–rural economic linkages and greater local governance autonomy, which can more fully realize the benefits of clarified property rights.

These findings are consistent with prior studies highlighting the link between secure land tenure and social stability while providing new empirical evidence through a quasi-natural experimental design. Unlike previous research primarily based on cross-sectional surveys or qualitative analysis, this study employs panel data from the new round of land titling, allowing for more robust identification of causal relationships. Moreover, the analysis of heterogeneous effects sheds light on how local social structures and economic conditions modulate the effectiveness of land reform.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study employs panel data from the National Fixed-Point Survey (NFPS) conducted by the Research Center for Rural Economy (RCRE) of the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, covering 2013–2021. It also utilizes a staggered DID model to empirically examine how the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation affects rural conflicts and disputes, as well as the underlying mechanisms driving these effects. The main findings are as follows:

First, the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation significantly reduces the incidence of rural conflicts and disputes. These findings support H1. The results remain significant after a series of robustness checks. Second, the effect operates through increased household agricultural operating income, enhanced farmers’ bargaining power, and reduced property rights infringements. These findings support H2, H3, and H4. Third, the impact is more pronounced in villages with balanced clan power, greater income disparities, and non-suburban locations. These findings demonstrate that secure and well-defined land tenure is pivotal for sustaining rural social stability.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This study leaves several questions for subsequent studies to address. First, it does not provide an in-depth analysis of the specific mechanisms by which the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation influences different types of rural disputes. Future research could explore these pathways using qualitative or mixed-methods approaches. Second, the evidence is derived from China. Comparative studies across countries with varying land policies and economic development levels would help generalize the findings.

6.3. Policy Implications

To maximize the social stabilizing effects of the new round of agricultural land rights confirmation, several key pieces of advice should be considered:

(i) It is important to continuously consolidate and translate the achievements of agricultural land rights confirmation. Efforts should focus on securing farmers’ land contract rights, stabilizing expectations, and strengthening the practical application of confirmed rights. A unified electronic land information system should be developed to ensure transparent and up-to-date records, aligned with the national real estate registration system. This will facilitate land transfer, mortgages, and management. As the second round of land contracts approaches expiration, contract extensions should proceed prudently, respecting historical arrangements and maintaining stable contracting relationships.

(ii) Land rights confirmation should be linked with local socio-economic development and rural governance. Heterogeneity tests indicate that the stabilizing effect of the new round of land confirmation is stronger in villages with balanced clan influence, larger income gaps, and non-peri-urban locations. Beyond property rights, confirmation is an important tool for enhancing local governance capacity. Confirmed land rights should be integrated into village-level mediation systems, prompting a diversified dispute resolution framework based on law, supported by self-governance, and complemented by moral guidance. In areas with strong clan influence or acute distributional conflicts, mechanisms such as collective land shares and dividend distribution can expand reform benefits, reduce potential conflicts, and maintain social stability.