1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid transformation of global socioeconomic development and the increasing frequency of extreme climatic disasters have severely compromised the livelihood stability of impoverished and vulnerable groups, particularly agro-herders [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In the context of sustainable development, resilience has attracted increasing attention because it integrates the multi-dimensional capabilities of agro-herders to cope with external challenges, and international anti-poverty programs have prioritized supporting rural households in building resilience to multiple shocks [

5,

6]. Grassland ecosystems, covering approximately 40% of the global terrestrial area and serving as one of the world’s most critical carbon sinks while supplying 30−50% of global livestock products [

7,

8], currently face severe threats from persistent degradation driven by climate change and socioeconomic activities. The crisis in the living environment underscores the necessity of investigating the resilience of herder households and their influencing mechanisms to promote their sustainable livelihoods [

9].

Grasslands are China’s largest terrestrial ecosystems. In the early 21st century, China launched the Grazing Withdrawal Project (GWP) to curb the increasingly severe trend of grassland degradation, which involved a variety of measures, including grazing prohibition, livestock–grass balance, artificial grassland management, ecological migration, and subsidies [

10,

11]. Ensuring the livelihood and welfare of herders is crucial for the sustainable protection of grasslands. Extensive studies revealed that, in the early stages, the interruption of grazing plans and insufficient grain subsidies led to a dilemma for many herders, resulting in numerous violations of regulations and poor policy implementation outcomes [

12]. It was not until 2011, when subsidies were changed to cash and their standards were continuously increased, that herders’ subjective well-being and policy satisfaction began to rise [

13,

14]. However, it remains uncertain whether current policies can sustainably consolidate these achievements in the face of future shocks such as rising living costs and sudden emergencies; a resilience lens is therefore needed to examine the viability of sustained well-being protection and its underlying issues. We aim to answer the following three questions: How does the GWP affect the resilience and subjective well-being of herders? Does the GWP enhance herders’ resilience, thereby improving their subjective well-being? How should the GWP be optimized to enhance herders’ resilience and promote their subjective well-being? However, existing literature has paid limited attention to the impact of the GWP on herders’ resilience [

15,

16], leaving the mechanisms through which such policy interventions affect household resilience and well-being poorly understood.

The Tibetan Plateau is a global research hotspot for grassland degradation [

17], and Maduo County, located in the heart of the Tibetan Plateau, is the birthplace of the Yellow River and holds exceptional ecological significance. With 77% of its land area located within the Sanjiangyuan National Park and all utilizable grasslands included in the scope of the GWP, selecting this county as the study area enables us to examine the mechanisms for enhancing herders’ resilience and well-being in ecologically fragile regions under stringent policy restrictions. We construct a composite index of household economic resilience and apply multiple linear regression to assess the effects of the GWP on both economic resilience and subjective well-being among herder households. Furthermore, a mediation analysis is conducted to test whether economic resilience serves as a transmission mechanism linking the GWP to improved well-being. This approach provides a nuanced understanding of the pathways through which conservation policies enhance herders’ welfare, thereby offering insights for the design of targeted and effective socio-ecological policies. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the analytical framework, study area, data sources, and methodology.

Section 3 presents the empirical results,

Section 4 provides a comprehensive discussion, and

Section 5 concludes the study by summarizing key findings and outlining policy implications.

2. Literature Review and Analytical Framework

The concept of resilience, originating in physics and engineering as a material’s capacity to absorb external forces and return to its original state after deformation [

18], emphasizes not only a system’s ability to withstand shocks but also its capacity to adapt and transform [

2,

19]. Reggiani et al. argue that resilience serves as a key explanatory factor for differential responses to shocks across systems [

20]. Economic resilience, applicable to various economic entities such as individuals, families, and countries, constitutes a key dimension of resilience theory [

21,

22,

23]. Household economic resilience focuses on the ability to avoid returning to poverty at the economic level when facing external challenges [

2,

24], including capabilities in various aspects, such as adaptation, recovery, learning, and innovation [

16,

25]. Households with higher economic resilience usually have stronger risk resistance, adaptability, and livelihood sustainability [

26]. With China’s nationwide eradication of absolute poverty in 2020 and the subsequent shift in policy focus from poverty alleviation to fostering endogenous drivers, enhancing economic resilience has become critical to consolidating poverty reduction achievements in rural areas [

27]. There are usually three ways to measure economic resilience. The first is to calculate the probability of an individual achieving a benchmark welfare level over a certain period [

23]; The second involves using single indicators, such as income [

28], changes in income [

21,

22,

23], and crop yields [

29]; The third is to measure through the construction of an index system, although no unified standard has been established thus far [

16,

25]. High resilience implies the ability to rapidly restore function and supply chains during crises by mobilizing internal and external resources, typically encompassing three core capacities: resistance capacity, recovery capacity, and reorganization capacity [

2,

30,

31], and this framework is also applicable for evaluating the economic resilience of herder households in the context of the GWP.

In recent years, international consensus has increasingly recognized economic growth as a means toward sustainable development, with human well-being constituting its ultimate end [

32]. Subjective well-being refers to an individual’s overall evaluation of their quality of life based on their own criteria, which is grounded in objective conditions and encompasses personal values and spiritual pursuits, thus gaining scholarly traction [

32,

33,

34]. Existing studies indicate that household resilience positively influences subjective well-being [

35]. The households with high economic resilience adjust development pathways more effectively to buffer shocks, thereby maintaining stable welfare improvements amid uncertainty [

36]. Key mechanisms underpinning this stability include income and consumption smoothing, strengthened intra-household social and material support, as well as improved self-esteem and sense of achievement among members [

2,

37]. However, there is a scarcity of current studies focusing on the economic resilience of pastoral areas and linking it with subjective well-being, and the impact of policies on both has not been fully considered.

The GWP, as a comprehensive government-led project, has been found to significantly impact herders’ grazing behaviors, livelihood strategies, and sources of income [

38,

39,

40], thereby affecting herders’ resilience in various ways [

1]. The combined implementation of grazing prohibition, ecological migration, and subsidies has led some herders to settle in towns, shifting their income sources from traditional animal husbandry to government subsidies and wage labor in various industries [

41]. Measures such as livestock–grass balance, fencing and livestock shed construction, and the establishment of livestock cooperatives have, to some extent, promoted the efficiency and benefits of livestock management [

42]. In national park areas, the ecological inspector policy has also provided part-time jobs for herders. Currently, the overall income level of herders in the project area has improved [

41], and their project satisfaction and life satisfaction are at a moderate or above level [

13,

43,

44]. Studies in the Sanjiangyuan area have found that the level of livelihood resilience among herders varies across different regions [

15,

40], with those engaging in diversified livelihoods, participating in joint grazing among multiple households, and using new energy sources showing stronger resilience [

40]. Natural factors such as rising temperatures and reduced precipitation can weaken resilience, but cash subsidies can serve as a key factor to enhance resilience and mitigate the negative impacts of climate [

1,

24]. In addition, supportive measures such as improved infrastructure, expanded credit channels, and information sharing have also shown positive effects in enhancing resilience [

15]. To elucidate the mechanisms shaping economic resilience of herder households and their relationship with subjective well-being in specially protected pastoral regions such as Sanjiangyuan, and to identify key influencing variables, this study develops an analytical framework based on a synthesis of existing literature. As shown in

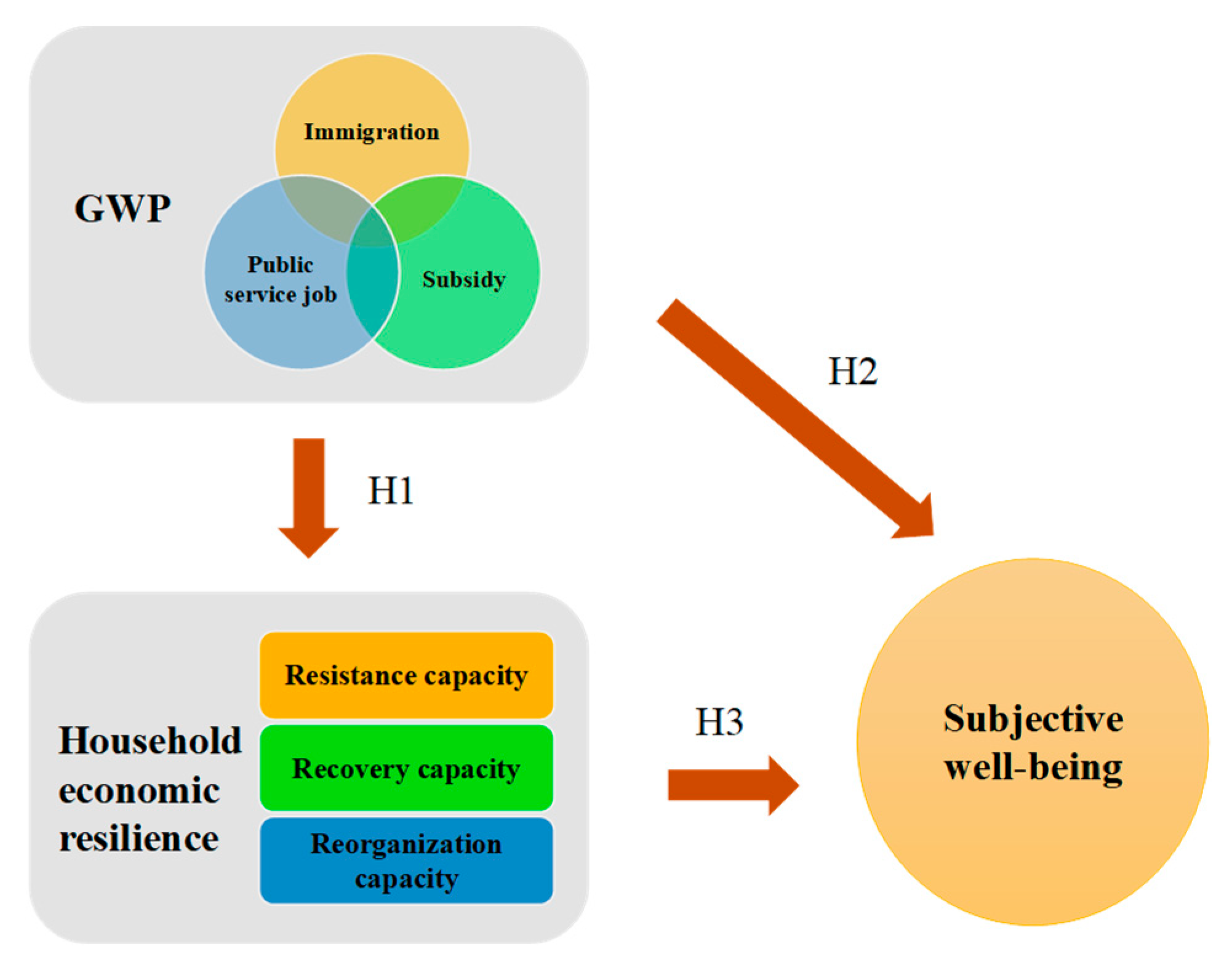

Figure 1, the framework positions the GWP as the independent variable, subjective well-being as the dependent variable, and household economic resilience as the mediating variable, positing that the GWP influences herders’ subjective well-being both directly and indirectly through this mediating mechanism. The study further proposes the following three hypotheses:

H1: The GWP has a significant positive effect on household economic resilience.

H2: The GWP has a significant positive effect on herders’ subjective well-being.

H3: Household economic resilience mediates the relationship between the GWP and subjective well-being.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview of GWP in the Sanjiangyuan Area

By the early 21st century, severe grassland degradation had occurred in China, displacing many herders as “ecological refugees”. In response, China launched the GWP and designated Sanjiangyuan region as one of the first pilot zones for grazing prohibition. As a pioneering reform in pastoral management without precedent, the measures of GWP have been continuously adjusted based on operational feedback (See

Table 1). Core interventions include grazing bans, ecological relocation, grassland-livestock balance systems, construction of enclosed sheds and pens, and degraded black-soil beach rehabilitation. Additionally, as a nationally prioritized protected area, the region has seen its conservation status elevated from a provincial nature reserve to a national park since 2000. While ecological protection efforts have been continuously strengthened, grazing restrictions imposed on local herders have also intensified.

3.2. Profile of Research Area

Situated in the northeastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (96°50′−99°20′ E, 33°50′−35°40′ N) at an average elevation exceeding 4200 m, Maduo County features gentle topography and numerous rivers and lakes, serving as the headwater of the Yellow River (see

Figure 2). It spans approximately 25,300 km

2 and administers four townships: Machali, Huashixia, Huanghe, and Zhalinghu. By the end of 2023, the resident population was 14,870, over 90% of whom were Tibetan. Benefiting from abundant water and pasture resources, in the early 1980s, Maduo recorded the highest per capita net income among herders nationwide for three consecutive years through extensive expansion of animal husbandry. Subsequently, severe ecological degradation caused by overgrazing and mining, exacerbated by stringent conservation restrictions, led to the stagnation of pastoral development, ultimately resulting in its designation as a nationally recognized poverty-stricken county in 2011.

The most impactful policy measures on the Maduo include grazing restrictions, resettlement programs, ecological compensation, the eco-guardian system, etc. Approximately 84.66% of the county’s utilizable grassland falls under conservation measures, with grazing bans and grassland-livestock balance systems covering 74.22% and 25.78% of this area, respectively. Two large-scale relocations have occurred: first, an ecological migration from 2004 to 2007 transferred about 2022 herders (≈25% of the population then) to collective villages; second, a poverty-alleviation relocation initiated in 2016 resettled 4473 herders (over one-third of the population then) around the county seat. Against the backdrop of a growing population, the allocation of grassland ecological subsidies has shifted from a land area-based model to a per capita system, currently amounting to approximately CNY 9000 per person per year. Other forms of subsidies include support for vulnerable groups (CNY 5600/year for individuals under 16 or over 55), fuel subsidies (CNY 2000/year), pensions, and subsistence allowances. Additionally, 3142 ecological inspector positions have been created, providing an annual income of CNY 21,600 per family. Overall, policy-driven subsidies have become a major component of herder households’ annual income. In 2019, Maduo County achieved full poverty alleviation under targeted national strategies. By 2023, per capita disposable income of rural residents reached CNY 11,738, a 7.0% year-on-year increase.

3.3. Data Sources

Field surveys were conducted in July and August of 2021−2023. In the first year, the research focused on understanding the socio-economic conditions and the implementation status of the GWP in Maduo County. Preliminary communications were established with government departments and a small number of herders. In the second year, formal survey work was conducted using the stratified random sampling and participatory questionnaire survey method to understand the herders’ livelihood status, subjective well-being, and evaluation of GWP. In the third year, supplementary policy documents related to the project were collected to enhance contextual and analytical depth. The study covered major resettlement villages and herder settlements (see

Figure 2), as well as mobile herders dispersed across summer grazing areas. To comprehensively capture populations affected by the GWP, the research also included two villages that were relocated but still under the jurisdiction of Maduo County: Guoluo New Village in Tongde County (relocated from the Huanghe Township in 2006) and Heyuan New Village in Maqin County (relocated from Zhalinghu Township in 2004).

A stratified random sampling approach was employed, covering 283 herders’ households across Maduo’s four townships, with 266 valid questionnaires retained. The sample distribution was 36.09% from Huanghe Township, 31.20% from Zhalinghu Township, 20.30% from Machali Town, and 12.41% from Huashixia Town. Additional methods included government seminars, field visits to project sites, and interviews with key grassroots staff, generating nearly 30,000 words of qualitative records. The sample was gender-balanced (55% male, 45% female). Among the respondents, approximately 82% were household heads aged 20−60, of whom 76.7% had received no formal schooling. Average household size was 3.85 members, and 62.93% of the surveyed households experienced expenditures exceeding incomes.

3.4. Variable Selection

The variables selected for this study are presented in

Table 2, consisting of four main components: the dependent variable, control variables, explanatory variables, and the mediating variable. The dependent variable is the subjective well-being of herders. Control variables include basic characteristics at both the individual and household levels. Explanatory variables comprise key policy measures and policy implementation variables. The mediating variable is the household economic resilience of herders under the GWP.

3.4.1. Dependent Variable

Subjective well-being, as defined by the OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being (2013), comprises three core dimensions: life evaluation, affective experience, and eudaimonic well-being [

45]. Psychologists often treat subjective well-being as an umbrella term capturing how individuals perceive their lives. Measurement typically relies on self-reporting through (1) a single-item life satisfaction question, (2) a weighted composite score of satisfaction across life domains, or (3) multi-dimensional scales [

46,

47]. This study employed a single-item measure to assess subjective well-being. Participants were asked to rate their overall subjective well-being on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very unhappy) to 5 (very happy), with higher scores indicating greater levels of well-being.

3.4.2. Control Variables

Subjective well-being is influenced by numerous factors, including individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education, health, marital status, income), living conditions (e.g., housing, food security, transportation), and socio-cultural elements (e.g., religion, cultural norms), all of which have demonstrated significant correlations in various studies [

48,

49,

50]. Given the context of Maduo County, we selected three individual-level variables (gender, age, occupation) and three household-level variables (labor force ratio, highest education level in the household, per capita health status) as control variables.

3.4.3. Explanatory Variables

The grassland conservation program employs a mix of policy instruments to regulate herders’ land-use behaviors, including coercive measures (e.g., grazing bans, livestock reduction, resettlement), incentive-based tools (e.g., forage subsidies, grassland awards), and supply-side interventions (e.g., artificial pasture construction, degraded grassland restoration). While this regulatory network aims to steer behaviors toward policy goals, it simultaneously disrupts livelihood foundations, income sources, social roles, and networks, and often opportunistic adaptation strategies from affected households. As the headwater of the Yellow River and an early pilot zone for the GWP, Maduo’s experience highlighted the pronounced impacts of resettlement, cash subsidies, and public welfare employment on herders’ livelihoods [

41]. Thus, this study selected three policy measure variables (subsidy adequacy, resettlement distance, effectiveness of employment support) and two policy implementation variables (awareness of policy communication, availability of emergency support) as explanatory variables.

3.4.4. Mediating Variable

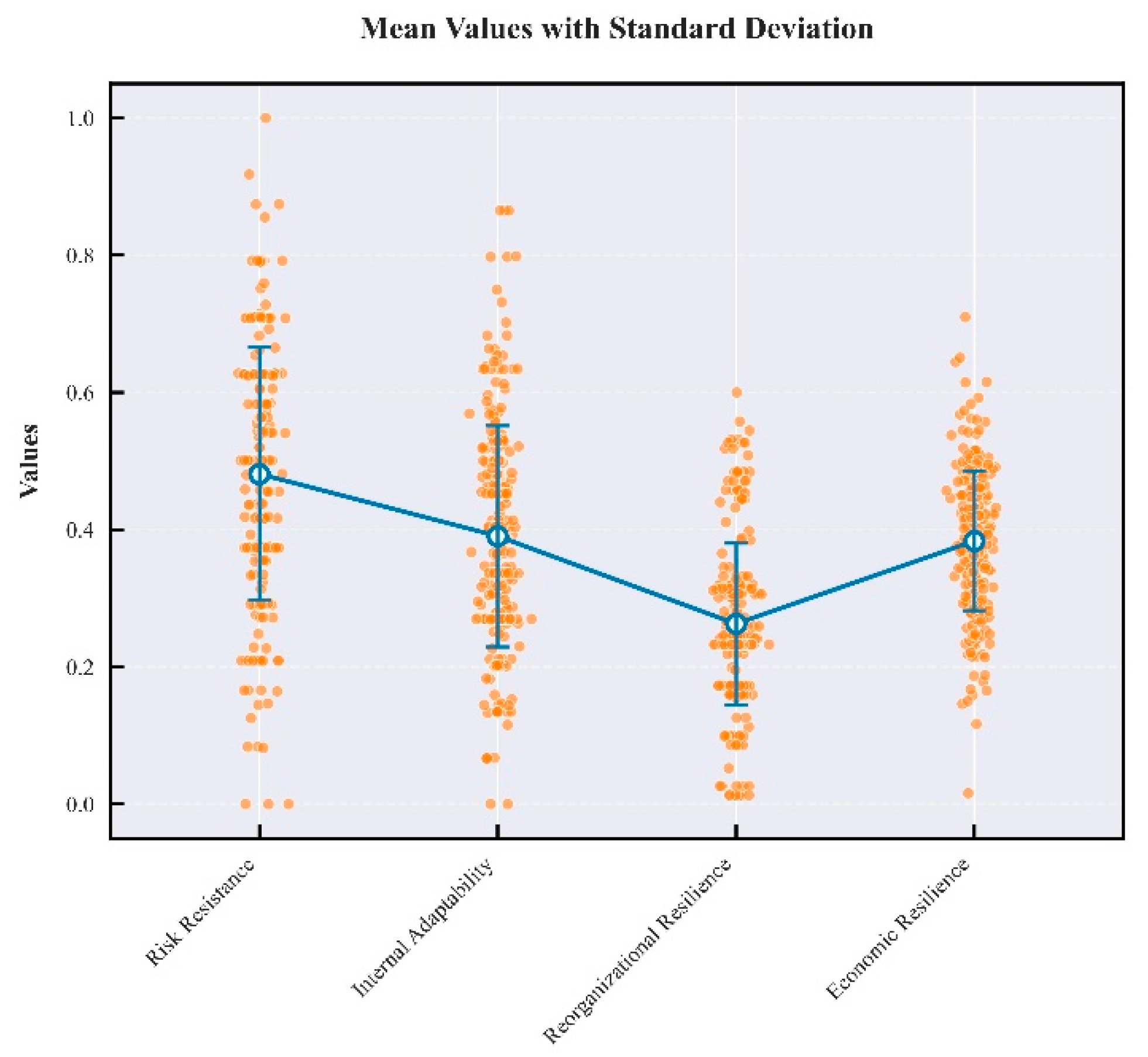

Taking the resilience framework and local situation into account, we constructed a household economic resilience index with three dimensions: resistance capacity, recovery capacity, and reorganization capacity. Resistance capacity reflects a household’s economic capacity to withstand shocks in the context of GWP, measured by changes in annual income, relative living standards, and income-expenditure balance. Recovery capacity captures the ability to recover quickly from economic distress, assessed through income stability, expenditure–income ratio, number of available helpers, and access to credit. Reorganization capacity reflects the ability to perceive development opportunities and self-development, evaluated via market accessibility, development willingness, potential livelihood channels, and long-term planning. Indicators were normalized using the Min–Max Normalization Method, and weights were assigned via the Entropy Weighting Method. The composite economic resilience index and its three-dimensional sub-indices were calculated accordingly. Detailed indicators are presented in

Table 3.

3.5. Research Methods

3.5.1. Mediation Effect Model

Following the approach of Wen [

51] and using SPSS Statistics 26 (International Business Machines Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), a three-step regression analysis, utilizing multiple linear regression modeling, was employed to examine the mediating role of household economic resilience. The analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26 (International Business Machines Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). (International Business Machines Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). This approach investigates how support policies under the GWP influence subjective well-being through economic resilience. The modeling procedure is as follows:

where

represents the subjective well-being of herder

i;

represents the mediating variable, household economic resilience;

denotes the core explanatory policy variables;

includes individual and household characteristics;

and

are the intercept;

,

,

,

, and

are parameters to be estimated; and

is the error term. Equation (1) specifies the impact of policy variables on subjective well-being as the baseline regression model. Equations (2) and (3) construct the model for examining the mediating effect of economic resilience. If

,

, and

are statistically significant, while

becomes non-significant, full mediation is indicated. If all four coefficients (

,

,

and

) are significant but the magnitude of

decreases relative to

, partial mediation is indicated.

3.5.2. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

The coupling coordination degree model is widely employed to assess the synergistic development between different systems. In this study, it is adopted to evaluate the coordination level among the three dimensions of household economic resilience. The formulas are specified as follows:

where

C denotes the coupling degree, reflecting the intensity of interaction and interdependence among the three capacities.

,

and

represent risk resistance, inherent adaptability, and reorganization capacity, respectively.

CD indicates the coupling coordination degree, quantifying the level of benign synergy among these dimensions. A higher

CD value implies greater consistency and harmonization in the public value delivered by the GWP. Given the equal importance of each capacity, the coefficients

are all set to 1/3. The

C is classified into ten progressive levels from 0 to 1, ranging from “extremely uncoordinated” (0.000–0.099) to “premium coordination” (0.900–1.000), following the widely accepted decile partitioning scheme [

52].

5. Discussion

Households in Maduo County exhibited notably low economic resilience (0.384), particularly in reorganization capacity, which was consistent with the findings of Zhao et al. in their study of Tongren County and Gonghe County [

15]. Grassland ecological subsidies, as stable and predictable income, can effectively compensate for income losses due to grazing restrictions, ensuring livelihood stability and enhancing risk resistance [

1,

53]. However, our study indicates that such long-term subsidies have no positive impact on reorganization capacity. Path dependence theory suggests that once a policy regime is established, it creates an incentive structure that discourages behavioral change. If passive subsidy income is financially more secure than active market participation, it may systematically hinder reorganization efforts. Our surveys indicated that most herders’ households lacked long-term planning and access to potential livelihood channels, which may result from a combination of remote location, limited employment opportunities, and existing policy incentives. As one interviewee noted, “Finding a job voluntarily may lead to losing disqualification for minimum living allowance.” Nonetheless, this approach inadvertently reduces incentives for market engagement, technological adoption, and skill acquisition, ultimately undermining the long-term development ability of households. This aligns with Sen’s concept of “capability deprivation,” which emphasizes that providing commodities (such as cash) does not necessarily expand real freedoms (such as the capacity to choose alternative livelihoods) [

54].

In other project areas outside protected areas, although the government’s intention in providing subsidies is to reduce herders’ dependence on grasslands and promote livelihood transformation, many herders still choose to continue livestock breeding even when the subsidies have increased to become the most important source of household income [

55]. Therefore, reform to the current subsidy system should be placed on the agenda [

1]. Drawing on the experience of Western countries, future improvements should be made from multiple perspectives, such as strengthening the supervision policy system, increasing investment in scientific research and technology development, calculating differentiated subsidy standards, and developing market-based subsidy mechanisms [

39,

55,

56].

Despite relatively low resilience levels, herders in Maduo County reported comparatively high subjective well-being. This phenomenon is similar to the findings from surveys in pastoral areas in Southwest China [

16,

37], indicating that herders’ subjective well-being has become decoupled from their endogenous development capabilities. Results from regression and mediation analyses indicated that household economic resilience exerted a significant positive effect on herders’ subjective well-being, but it only partially mediated the impact of relevant policies. The sense of security engendered by well-designed subsidies and accessible emergency assistance continued to be a significant source of herders’ subjective well-being in Sanjiangyuan region. Relying solely on subjective well-being as an indicator of policy success is therefore incomplete and potentially misleading, as high levels of reported well-being may conceal underlying vulnerabilities in household livelihood structure.

Studies conducted in other pastoral regions impacted by the GWP have shown that herders with large-scale grasslands have rented additional grassland and increased supplemental feeding, while herders with small-scale grasslands have transferred their grassland use rights and shifted their livelihoods toward off-farm employment. In contrast, herders with small-scale grasslands seeking alternative livelihood options have derived fewer benefits from the GWP [

53,

57]. In the Sanjiangyuan National Park region, most herders have faced grazing bans and passive relocations, making the pursuit of alternative livelihoods an inevitable choice for long-term development. While China’s poverty alleviation initiatives have successfully eradicated absolute poverty, addressing issues of “relative poverty” and “developmental disparity” remains particularly challenging in ecologically vulnerable regions such as the Tibetan Plateau. Although there are government-led skill training activities and public welfare positions set up during the implementation of GWP, the limited reorganization capacity observed in this study indicates that such training initiatives have yielded suboptimal outcomes, largely due to their disconnection from viable economic opportunities within the local market [

58]. Therefore, we propose a policy shift from “protective support” toward “promotive support”. First, investment across the entire value chain of pastoral products—such as organic yak dairy, meat, and hides—as well as culturally and ecologically informed tourism, should be leveraged based on the region’s unique ecological and cultural assets. Such place-based development can generate locally adapted employment opportunities and retain benefits within the community. Second, given the significant positive correlation between the highest educational attainment within a household and reorganization capacity and the limited uptake of new skills among older herders, intergenerational investment in formal education represents the most effective long-term strategy. Enhancing human capital among the younger generation can enable their participation in a diversified economy beyond traditional pastoralism, offering a promising pathway to break the cycle of dependency. Finally, we advocate for conditional and transformative subsidy mechanisms. Subsidies could be partially linked to participation in skills certification programs, eco-friendly pastoral practices, or community conservation initiatives. This approach would gradually shift the incentive structure from passive receipt to active contribution and capability acquisition.

6. Conclusions

Based on 266 household surveys in Maduo County, this study examines the impact of the GWP on herders’ economic resilience and subjective well-being and identifies the mediating role of economic resilience in well-being improvement. Key findings include the following: (1) Herders in Maduo County exhibited relatively high subjective well-being, alongside low household economic resilience, with reorganization capacity identified as the critical bottleneck within the economic resilience framework. (2) Both subsidy adequacy and emergency support exerted a dominant positive effect on resilience and subjective well-being. Specifically, subsidies exerted the strongest influence on risk resistance, whereas investment in education significantly enhanced households’ reorganization capacity. (3) Economic resilience had a significant positive impact on herders’ well-being, partially mediating the relationship between policy variables and subjective well-being, while cash subsidy and emergency support remained the primary drivers of subjective well-being. These results underscore the importance of sustained fiscal transfers in ensuring well-being but also highlight collective deficiencies in reorganization capacity. To address these challenges, developing localized industries grounded in unique regional resources, strengthening investment in education, and transitioning toward a more sustainable “capacity-building” support system represent promising strategies to break the current impasse.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. As our analysis relies exclusively on cross-sectional data, it cannot capture the dynamic evolution of herders’ resilience across different periods. Future research should employ longitudinal tracking and multi-phase comparisons to identify temporal changes in household economic resilience. It is also critical to assess resilience levels under subsidy-free scenarios and explore diversified policy support systems that better align with contemporary developmental challenges.