1. Introduction

Urban safety, considered one of the main challenges for contemporary cities, is one of the main problems identified in the central district of Madrid [

1]. This district is one of the most representative and densely populated areas of the city. With about 5.2 km

2 and more than 149,000 inhabitants, it has a high demographic concentration and a remarkable social, cultural and economic heterogeneity. According to the 2024 census, 40% of its residents were born outside Spain, with neighbourhoods such as Sol and Lavapiés where immigrants represent up to 50% and 43.5% of the population, respectively. This diversity is manifested both in community habits and in the configuration of public space.

Along with these aspects, the advance of gentrification and the intensive tourist use of housing have transformed the social fabric, generating population displacements and changes in urban dynamics. The displacement of traditional residents by new owners with greater purchasing power, together with the high population turnover derived from short-term tourist rentals—especially through platforms such as Airbnb—has significantly modified the dynamics of use and appropriation of urban space.

This area has one of the highest crime rates in the capital, 37% of the total crimes reported in the city, according to the most recent data from the City Council and the Ministry of the Interior [

2]. Insecurity directly affects the quality of life of those who live in the district, limiting the use of public space and negatively impacting small businesses and hospitality. The most frequent crimes are drug trafficking, theft, violent robberies and sexual assaults, configuring an urban scenario where the feeling of an insufficient police presence increases the perception of risk and lack of protection in the neighbourhood.

In this context, the central problem raised by this research lies in the lack of effective mechanisms to assess urban safety from a subjective and experiential perspective. The challenge is to integrate qualitative and quantitative methodologies to build tools that promote inclusive urban planning, sensitive to differences, and aimed at improving the perception of security from a cross-cutting approach to gender and spatial justice.

The relationship between public space planning and security in the contemporary city is today one of the axes that underpin urban intervention policies, both in the provision of new environments and in the rehabilitation and recovery of those considered unsafe [

3]. Recent academic production, underlining the importance of the design of public space in the prevention of urban crime, directly links urban security with the subjective perception to inhabit public space without fear [

4] and identifies, for the same environment, a greater sense of insecurity in women [

5]. However, traditional methodologies that address urban crime prevention from the design of the environment have prioritized a daytime, functionalist and standardized vision of the city [

6]. For this reason, the urban space at night demands a more in-depth study, both in theory and in practice. This omission creates an analytical and project gap that is particularly significant when considering the experiences of women and other vulnerable groups [

7]. In this scenario, the nocturnal city, a territory yet to be explored in contemporary urbanism, can be perceived as a threatening environment for women, limiting their way of moving, moving around and interacting with the city [

8].

Therefore, the research defines as a priority figure of analysis a user who travels and uses the city intensively and polyfunctionally throughout the day—for work, training, leisure or care reasons—and who faces, in a structural way, specific risks associated with symbolic and physical violence in public space. This profile makes it possible to make more visible the interaction between urban design, social organization of time and perception of insecurity, particularly during night hours or in urban contexts with low formal and informal surveillance.

This research, framed in the Master’s Degree in Urban Design and Sustainable Mobility of the Universidad Europea de Canarias proposes a methodology of cartographic analysis that develops three types: spatial analysis, participatory cartography and critical cartography. In this way, objective data—such as public lighting, accessibility, pedestrian density, presence of vegetation or night-time uses—are articulated with subjective information obtained through sensitive cartographies, interviews and accompanied tours. This approach allows us to contrast formal urban planning with the daily experience of the users, making visible the gaps between the designed city and the lived city.

One of the central axes of the work is the notion of multiscale. Far from being limited to a single dimension of analysis, the study addresses the phenomenon of insecurity from different scales: the object scale (related to specific urban elements such as lighting or furniture), the neighbourhood scale (neighbourhood interaction, urban vitality) and the district scale (general infrastructure, connectivity, distribution of resources). This strategy allows us to obtain a more complete view of the urban conditions that influence the perception of safety and the night-time habitability of public spaces.

From a theoretical point of view, the work is based on the contributions of feminist urbanism, critical geography and the theory of urban perception. The contributions of classic authors such as Jane Jacobs [

9] or Dolores Hayden [

10] are taken up, together with the more recent Ana Falú [

11], or Leslie Kern [

12], among others, who have highlighted the need to build more inclusive urban environments, sensitive to the diversity of bodies, rhythms and ways of inhabiting [

13]. The current regulatory frameworks are also considered, which transfer the provisions of the Spanish Urban Agenda and the 2030 Agenda regarding the integration of the gender approach in urban policies [

14].

This research not only aspires to be a diagnosis of the current conditions of the central district of Madrid, but also a propositional project that presents the cartographic method as a tool for the analysis, planning and design of the city. Through the results obtained, strategies are proposed to rethink the night-time public space from a perspective we have defined as “cat’s eyes”, alluding to the popular name by which the inhabitants of Madrid are known. This feminist and inclusive vision is committed to an urban planning that recognizes the complexity of urban experiences and guarantees the right of all people to move and inhabit the city safely and freely.

The structure of the work is organized around four blocks. First, the cartographic method used is presented, detailing the spatial and qualitative analysis tools used. The results of the analysis of objective and subjective data on urban night-time safety are presented below. Subsequently, a discussion section is included where the theoretical, methodological and practical implications of the approach adopted are reflected, ending with some conclusions derived from the research.

2. Materials and Methods

The research presented in this text is framed in a mixed methodological approach, articulating quantitative and qualitative techniques with the aim of comprehensively understanding the perception of urban security from a gender perspective. This approach seeks to overcome the limitations of traditional methods of urban planning, which tend to privilege objective and measurable indicators, but fail to capture the subjective experiences that structure daily living, especially of women [

15,

16].

Among these techniques, the use of cartography as a tool for characterizing urban dynamics is seminal. Traditionally, cartography has been a discipline of knowledge and territorial exploration that, since the Digital Revolution, incorporates the set of data linked to the territory to visualize the complexity itself triggered by the Technological Imperative, developing new graphic strategies that allow interpreting and analyzing processes involved [

17] capable of reflecting the cognitive perception of public space by human beings [

18]. These contemporary forms of cartography go beyond representing physical aspects of a place, integrating dynamic elements such as patterns of behaviour, future projections, human flows, or responses to unforeseen events. That is why they have begun to be linked to technologies derived from artificial intelligence, such as self-organizing maps (SOMs), capable of generating organized structures based on semantic patterns [

19]. Because of digitalisation, the use of Big Data, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and new technologies such as the aforementioned AI, new cartographies can represent all kinds of information have been developed.

Cartography is used in this work not only as a tool for spatial representation, but also as a method of general analysis that structures the process of urban research and diagnosis. The cartographic method is articulated here from two complementary approaches: the deductive process and the inductive process.

The deductive approach is based on a great-scale analysis based on the collection and processing of objective quantitative data (mobility, night-time uses, green areas, urban environment). Through its cartographic representation, a broad spatial diagnosis is generated that allows the identification of general patterns of (in)security, materialized, for example, in the elaboration of heat maps that synthesize the areas of greater or lesser urban vulnerability.

On the other hand, the inductive approach assumes the premise that knowledge of the urban context cannot be limited only to aggregated quantitative data. From this perspective—widely defended by critical geographers—we work on the micro scale and local experiences to identify more complex spatial dynamics. In this work, this approach has materialized through sensitive cartography, built from qualitative information obtained through interviews, accompanied tours and participatory mapping, and aimed at making visible the perceptions, emotions and narratives associated with the nighttime use of public space.

The proposed cartographic methodology, therefore, simultaneously integrates deductive and inductive processes, allowing the phenomenon of night-time urban security to be approached from a double perspective: the objectivity of spatial patterns and the subjectivity of lived experiences. This integration enriches urban analysis, aligning it with the principles of a feminist urbanism that recognizes the importance of scales, bodies, and perceptions in the social production of space.

As a consecutive stage in this methodological path, the research incorporates criteria of data visualization, a discipline considered fundamental in the translation of the complexity of the environment and whose study aims to graphically manage an amount of information that exceeds our capacity to process it. In this field, the systematic patterns of Manuel Lima [

20], as well as the maps of Picon and Ratti [

21] are presented as a new generation of cartographies capable of revealing unexplored realities of the cities we inhabit.

2.1. Layers of Urban Data

In this territorial complexity orchestrated by the avalanche of contents, it has been resorted to considering the organization of the data linked to the territory in thematic layers that structure the informational landscape of the city. If each of these layers provides information related to a specific area, their superposition brings us closer to the emerging reality of the territory under consideration [

22].

Combining data sources and analysis methods makes it possible to establish relationships between the physical conditions of the urban environment and the emotions, trajectories and personal experiences of the users. To do this, various analytical tools were used, structured around four fundamental layers: mobility, the urban environment, green areas and night-time uses. These layers were selected for their direct impact on the perception of safety and their relevance within urban planning with a gender approach.

The contents of the four data layers explored in this methodological section are detailed below.

2.1.1. Layer 1: Mobility

The mobility analysis focuses specifically on active mobility and the use of collective public transport. Other modes of transport, such as private motorised vehicles, are excluded, both because of the significant restrictions on road traffic existing in the area of study and because of the explicit desire to promote a sustainable, accessible and equitable mobility model. This factor is considered key in the study of night-time safety from a gender equity perspective, as it conditions women’s access to public space and their right to the city. In addition, the design of public transport and the urban environment does not always take these experiences into account, which reinforces vulnerability and highlights the need to plan safer, more inclusive and gender-sensitive night-time mobility.

A thematic cartography has been developed with four relevant layers in the GIS environment. For active mobility, cycling routes and Bike’s APP BiciMAD stations have been incorporated. Regarding public transport, the urban bus routes and the corresponding stops have been mapped.

2.1.2. Layer 2: Environmental Quality

It encompasses the natural elements present in the urban fabric, its state of conservation and lighting conditions. These elements play a fundamental role in improving environmental comfort, urban health and the quality of public space. However, their configuration, density and state of maintenance can have a negative impact on the perception of safety. In particular, excessively dense vegetation, poor visibility, deterioration of the plant environment or poor lighting can generate spaces perceived as unsafe, especially during night hours.

For its analysis, four layers have been represented in GIS. The first corresponds to green areas, which includes tree masses, landscaped areas, green spaces and landscape elements. The second layer collects the sheets of water, with special attention to the Manzanares River and the pond of the Retiro Park, as well as other smaller aquatic surfaces. Thirdly, a layer is incorporated that assesses the health of the vegetation cover using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). Finally, a layer is added that represents the urban lighting network, fundamental for the analysis of the perception of security at night.

2.1.3. Layer 3: Urban Environment

This concept refers to the physical and sensory configuration of the urban space, as experienced by users, and its direct influence on the perception of safety.

The presence of dirt, deteriorated street furniture or abandonment of public space projects an image of institutional neglect and little social control, generating a greater sense of vulnerability. On the contrary, the continuous and diverse presence of people—understood as human infrastructure—contributes to greater informal surveillance and reinforces the perception of security through social visibility. The permeability of the environment, i.e., the ability to see and be seen, is essential to avoid situations of isolation and promote natural surveillance. In the same way, noise, especially at night, can act as a deterrent or generate concern, as it is associated with potential conflicts or loss of control of the environment.

For its spatial analysis, four layers traditionally associated with the perception of insecurity have been represented in the geographic information system: urban dirt, presence of people in public space, visual permeability and ambient noise levels.

2.1.4. Layer 4. Uses and Nighttime Activities

The spatial configuration of uses and activities in the urban fabric directly determines the intensity, frequency and character of pedestrian and motorized traffic, especially in terms of the proximity, typology and operating hours of the establishments. This dimension is especially relevant during the nighttime period, in which the presence—or absence—of urban activity has a decisive influence on the occupation of public space, the perception of vitality and visibility. These factors are decisive in the subjective construction of safety, since environments with little traffic or lack of activity tend to be perceived as more unsafe, particularly by certain user profiles.

In order to analyze this dimension, four thematic layers have been represented in the GIS environment: nightlife venues (pubs and nightclubs), restaurants and shops open 24 h a day, cultural facilities for night-time operation (cinemas and theatres) and police presence, understood as an element of formal surveillance of the environment.

2.2. Objective Spatial Analysis

The first methodological phase consisted of a spatial analysis of the objective data of the Central district of Madrid, based on the compilation of quantitative information from official sources such as the Madrid City Council (Open Data Portal, Geoportal and the

Nomecalles gazetteer) [

23,

24,

25], the National Institute of Statistics (INE) [

26], the Cadastre [

27], the Municipal Transport Company [

28] and the Regional Transport Consortium [

29]. Through Geographic Information Systems (GIS) tools, these data were organized into thematic layers and represented cartographically to identify patterns of urban vulnerability.

The variables analyzed included: the night-time public transport network, public bicycle stations, urban lighting coverage, the distribution of green areas, environmental quality (NDVI), pedestrian density, noise levels, urban cleanliness and the presence of active uses at night (bars, theatres, restaurants, nightclubs). These layers of information were analyzed both individually and superimposed, allowing critical areas of structural insecurity to be detected.

This analysis adopted a deductive logic; that is, it started from generalized data at the district level to extract patterns that could later be contrasted with the subjective experience of women in specific contexts. In addition, a multi-scale approach was applied, adapting the cartographic representations to the characteristics of each of the layers considered in the analysis.

2.3. Collective Mapping

The next methodological level addressed the design and execution of a collective mapping exercise, focusing on the subjective perception of security of women in the neighbourhood of Lavapiés, one of the most diverse and conflictive areas of the central district. To this end, online surveys and accompanied tours were carried out with ten women selected according to criteria of age, origin and daily use of public space.

Each participant was provided with a file where they had to record a night itinerary of a maximum of five minutes, identifying five points of the route considered safe or unsafe, and justifying their perception based on elements such as lighting, presence of people, cleanliness, noise or open commercial activities. Although the tours were carried out in groups for safety reasons, the recording of perceptions was individual.

The results of the mapping were digitized and georeferenced, using graphic symbology (red and green dots, icons, colour codes) to represent the factors indicated. This information was integrated into a GIS that allowed contrasting individual perceptions with the objective conditions of the environment, thus generating a cross-database on perceived insecurity and urban variables.

To ensure the comparability and validity of the results in reference to internationally recognized methodologies for assessing perceptions of quality of life—particularly in a cross-national comparative framework—several questions included in this survey were adapted from the research structure of the World Values Survey (WVS). The WVS is a long-term multinational survey initiative that gathers representative data on cultural, political, and social attitudes in over 100 countries [

30]. This methodological alignment strengthens the study’s analytical framework and situates its findings within a global discourse on subjective well-being, urban security, and public space.

The design of the questionnaire draws from WVS formats, particularly through the use of Likert-type response scales (e.g., 1–4, 1–10) and thematic groupings focused on public safety, interpersonal trust, and gender roles in urban environments. Additionally, this methodological approach is informed by the WVS’s broader analytical model, which identifies two major dimensions of cross-cultural variation: traditional values versus Secular-rational values, and survival values versus Self-expression values. In this case, the study aligns most directly with the Survival values dimension, which places a strong emphasis on economic and physical security—precisely the central concern of this project’s investigation into perceived urban safety and vulnerability.

These two value dimensions were empirically derived through factor analysis conducted across multiple waves of the World Values Survey. Specifically, WVS researchers created composite indices using ten validated indicators—five for each dimension—which have consistently appeared across all four waves of the survey to ensure temporal comparability and statistical robustness. The adaptation of survey elements from this standardized model allows the current study not only to capture local perceptions of safety and trust in a rigorous way, but also to benchmark those results within a well-established international typology of values and urban experience.

By anchoring the local survey in the WVS’s structure, the methodology supports both context-specific insight and comparative analysis, enabling a clearer understanding of how perceptions of safety are embedded in broader cultural frameworks and how these might shift in relation to social vulnerability, governance, and urban form. This inclusion of the WVS methodology in the formulation of specific study questions serves as a verification tool for assessing the relationship between social change and countercultural shifts. It has been used to evaluate patterns of social acceptance on a wide range of issues, including attitudes toward high taxation, the impact of multicultural transformations, and the potentially harmful effects these changes may generate [

31,

32].

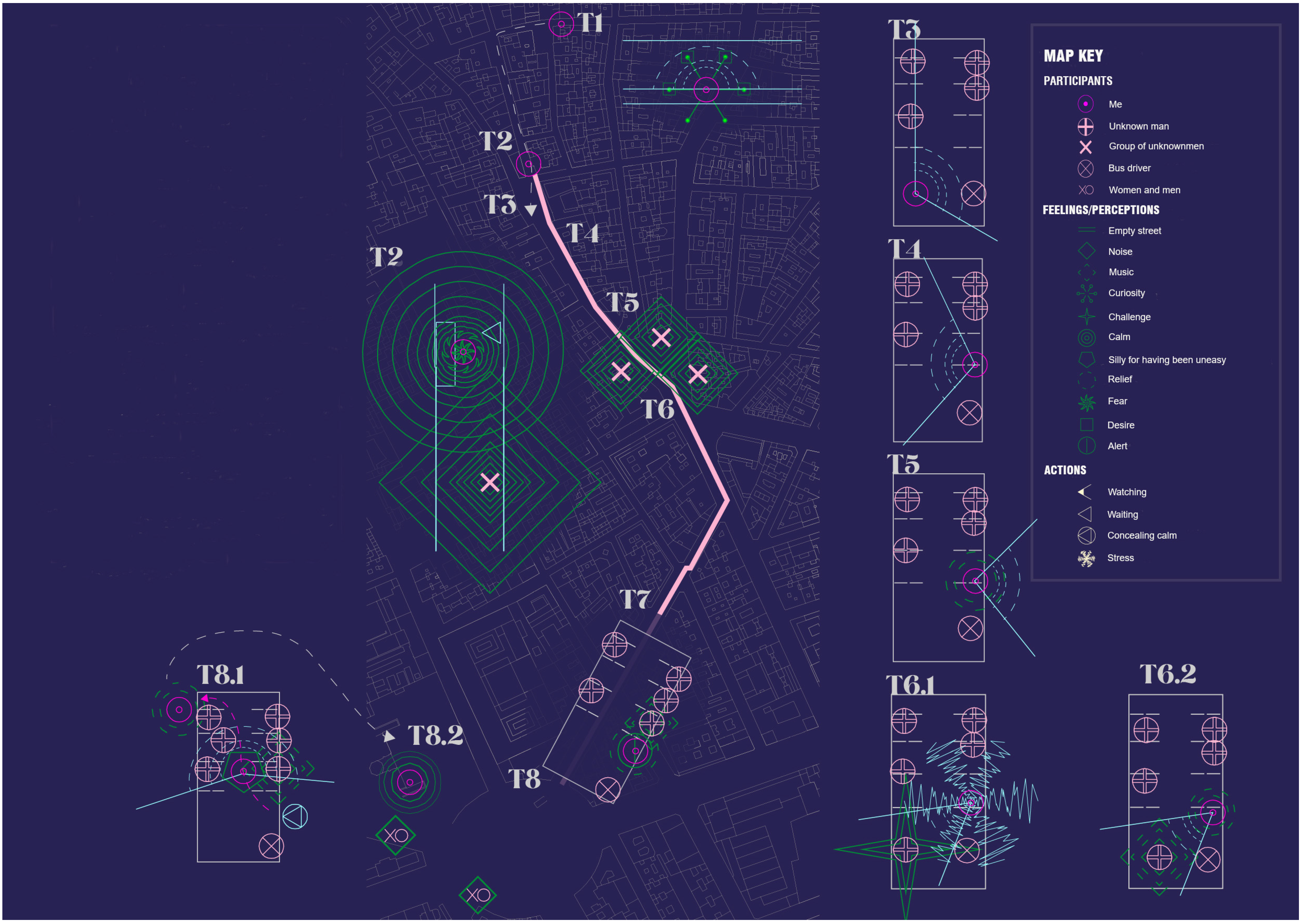

2.4. Sensitive Cartography

The third methodological tool used was sensitive cartography, understood as an instrument of qualitative representation capable of incorporating emotional, symbolic and bodily dimensions of the urban experience [

33]. Far from seeking quantifying objectivity, this technique values the user’s situated knowledge and allows them to represent aspects normally excluded from technical analysis. This methodology, heir to the conceptual foundations of Víctor Cano Ciborro’s cartographic research [

34], is justified within the framework of an inductive and qualitative research approach, in which knowledge is built from the personal experiences of the users, allowing the identification of emerging patterns from the local and the lived.

To this end, it was decided to carry out an exercise to apply this strategy on the mobility layer of the objective analysis. The purpose was to analyze the perception of security in women’s daily commutes, emphasizing the factors of the urban environment that influence their subjective experience of security, such as the width of the streets, the large obstacles or the premises that are not very permeable to the views, among others. This sensitive cartography is based on the experience of a user during a night bus journey, recording her journey from the exit of an establishment to her final destination.

The proposed approach seeks to enrich the representation of the nocturnal city from an alternative and experiential perspective. A sensitive cartography fosters the revelation of the collective emotions and imaginaries that inhabit it, generating a platform for deep and contextualized knowledge of the territory [

35]. This strategy, which can be extended to various urban scales and to the other layers of objective analysis, enables the construction of sensitive cartographies at the district or urban level, always preserving the inductive, experiential approach and with a gender perspective [

36].

2.5. Methodological Value

The method proposed in this work adds to the vindication of feminist urbanism towards traditional forms of urban planning. However, it introduces a critical tension in this framework: it recovers objective cartographic analysis as the main diagnostic tool, an instrument usually questioned by feminism for its abstract, distant and supposedly “neutral” nature. The decision to privilege spatial analysis through Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and measurable indicators (lighting, transport density, vegetation cover, land use) supposes, in a way, a shift with respect to the classic methods of feminist urbanism, which tend to distrust quantification as a reproducer of structural biases. However, this approach does not uncritically reproduce the technocratic bias, but rather subverts it, demonstrating that the feminist reading of space can also be nourished by verifiable metrics, if they are interpreted from a framework of spatial justice.

The main methodological contribution of the research lies in the articulation of two traditionally separate worlds: urban technoscience and feminist critical frameworks. The layering of the scope of action also allows the overlapping of a subjective layer, generating a hybrid model of analysis that enables the mutual reinforcement of data of different natures, stimulating a dialectic capable of characterizing the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed analysis. This articulation is especially effective because it gives empirical legitimacy to subjective perceptions, preventing them from being relegated to a merely testimonial plane, while at the same time giving interpretative density to objective data, which could otherwise be presented as decontextualized figures. Consequently, the methodological combination not only enriches the reading of the territory by combining diverse scales and perspectives but also transforms the flow of existing information into knowledge capable of responding to social demands linked to spatial and gender justice.

3. Results

The results obtained through the mixed methodological approach allow us to identify multiple dimensions of urban insecurity in the Central district of Madrid. These findings are grouped according to the four thematic axes defined: mobility, urban environment, green areas and night uses. Each of these axes has been approached from a double perspective: on the one hand, through objective spatial analysis; on the other, through subjective perception collected through collective mapping and sensitive cartography. The articulation between both dimensions allows us to understand in greater depth the conditions that configure the experience of (in)security in the night-time public space.

3.1. Objective Spatial Analysis Results

This section presents the results obtained from the objective analysis of the Central district of Madrid, structured in four main dimensions: mobility, urban environment, green areas and night uses. The systematization of these data makes it possible to clearly identify spatial patterns that would otherwise remain invisible, such as inequalities in the distribution of infrastructures, concentrations of uses or discontinuities in connectivity. The value of this approach lies in offering a verifiable empirical basis that provides solidity to the study and makes it possible to accurately contrast the material conditions that affect the configuration of the nocturnal urban space.

3.1.1. Mobility

The cartographic analysis of mobility in the central district of Madrid reveals significant inequalities in terms of coverage, accessibility and connectivity of public transport and complementary infrastructures. Firstly, the night transport network (owl buses) shows a marked radial orientation, with routes that start from the Puerta del Sol to different peripheral points of the city. This structure, although efficient for intermunicipal connection, leaves internal areas of the district with less accessibility, especially neighbourhoods such as Lavapiés and Embajadores, where the density of stops is lower than that of other sectors (

Figure 1).

The cycling network, evaluated by superimposing the official routes and the inventory of BiciMAD stations, presents notable discontinuities. Many sections lack spatial continuity and have signage deficits, which makes it difficult to use them as an alternative for night-time mobility. The coverage of public bicycle stations is heterogeneous: there is a concentration around Gran Vía and Sol, while peripheral residential areas within the district lack immediate access.

The analysis of the pedestrian infrastructure shows that, although there are main corridors with good connectivity (Gran Vía, Atocha, Princesa), there are still areas with steep slopes, stairs or narrowings that hinder fluid traffic. Universal accessibility is not guaranteed either, since the cartographies reveal points with the absence of recesses in sidewalks or the presence of architectural barriers. In terms of general mobility, the district presents a centralized pattern, with high accessibility in main axes and clear deficits in secondary areas. This inequality in spatial distribution conditions the fluidity of night-time journeys and the territorial integration of the district.

3.1.2. Environmental Quality

The spatial analysis of the green areas shows limited coverage in the Centro district and restricted access at night. The main green spaces of reference—such as the Retiro Park or the Sabatini Gardens—remain closed at night, which significantly reduces the availability of walkable plant areas in these time slots. The accessibility mapping, made from 300-metre buffers around open parks, confirms that a large part of the resident population is excluded from immediate access to night-time green spaces.

The calculation of the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) applied to satellite images shows that the vegetation cover in the district is low compared to other areas of Madrid. The highest values are concentrated in areas closed to the public at night, while in accessible spaces a low vegetation index predominates. This translates into a scarce presence of natural elements in the urban night-time fabric. (

Figure 2).

The squares and small neighbourhood gardens, which represent the majority of open spaces in night-time use, have deficiencies in terms of lighting, maintenance and connectivity. The mapping of the distribution of luminaires shows that, in some of these spaces, the central areas are left in semi-darkness, reducing the perception of visual control. In addition, dense tree cover at certain points generates areas with low visibility, recorded as “cartographic shadows” in spatial analysis models.

In view of the above, it can be said that the green areas of the Centro district show limited availability, with restricted access and unequal distribution, which reduces their potential as transit spaces or overnight stays.

3.1.3. Urban Environment

The cartographic analysis of the urban environment reveals an unequal distribution of factors that directly affect night-time habitability. Public lighting, measured from the density and location of luminaires registered in the open data portal, shows concentration in commercial axes and main avenues, while secondary streets have significantly lower levels of light coverage. This difference is accentuated in areas such as Lavapiés, where the density of luminaires is 35% lower than on Gran Vía.

The state of street furniture, assessed from municipal inventories and represented by thematic cartography, reflects a similar pattern: greater presence and maintenance in areas of high tourist and commercial influx, compared to a more evident deterioration in residential areas. Likewise, the street cleaning data, collected through the records of sweeping frequency and installed containers, show a concentration of resources in tourist transit areas (Sol, Gran Vía), with less attention in neighbourhoods with less media visibility.

The night-time noise pollution maps, based on environmental sensor records, show that the areas with the highest recreational activity have values above 65 dB between 11:00 p.m. and 2:00 a.m. Malasaña, Chueca and Huertas concentrate the highest levels, generating an environment with acoustic saturation that contrasts with peripheral areas of the district, such as Conde Duque or the surroundings of Lavapiés, where the records are lower. (

Figure 3).

3.1.4. Night Uses

In general terms, nighttime uses configure a fragmented spatial pattern, in which the vitality concentrated in certain areas coexists with the inactivity of others, generating significant contrasts within the district. The cartographic analysis reflects a marked concentration of recreational and commercial activities around specific axes, such as Gran Vía, Malasaña, Huertas and La Latina (

Figure 4). These areas have a significantly higher density of bars, restaurants, theatres and nightclubs compared to other areas of the district. The cartographic representation of activity points shows a polarized pattern: while some neighbourhoods concentrate great nighttime vitality, others remain practically inactive after 10:00 p.m. These factors are decisive in the subjective construction of safety, since environments with little traffic or lack of activity tend to be perceived as more unsafe, particularly by certain user profiles.

The contrast between areas of high and low activity is also reflected in the pedestrian traffic data. The corridors with the highest density of premises maintain active pedestrian flows until the early hours of the morning, while adjacent streets experience a drastic decrease in footfall after the closure of shops. This duality generates discontinuous urban landscapes, with areas of great social dynamism close to uninhabited spaces in short strips of distance.

Likewise, the urban surveillance cartography, which includes data on the presence of cameras and proximity to police stations, reveals a bias in coverage: areas with a higher concentration of entertainment venues have more control devices, while residential neighbourhoods have less night-time surveillance infrastructure.

3.2. Collective Mapping Results

The results of the collective mapping show how the participants identify the spaces of the central district in a differentiated way according to the sensations they awaken during the night. The resulting maps show avoided routes, areas associated with greater tranquillity and places marked as alert points, forming an emotional geography that complements the material reading of the territory. This cartography reveals significant contrasts between adjacent streets and allows us to recognize how certain urban configurations acquire specific meanings linked to the feeling of security or vulnerability.

As part of this process, an online survey was designed structured in several sections aimed at collecting information on women’s experiences, needs and perceptions during their daily journeys through frequented urban spaces. The questionnaire considered variables related to the use of public space, activities carried out, transit schedules, modes of transport and subjective assessment of perceived safety at different times of the day and night.

The survey made it possible to systematize the information from a large sample of participants, obtaining data that were later statistically processed to identify trends and recurring patterns. Based on the exploratory analysis of these data, a study area was selected that concentrated a high perception of insecurity: the Lavapiés neighbourhood, in the central district of Madrid, which also had urban characteristics that made it especially relevant for the objective of the research (high pedestrian density, functional diversity, morphological complexity).

To ensure the validity of the data collected, quality control techniques such as debugging of inconsistent responses and analysis of relative frequencies were applied. The survey phase thus constituted the fundamental basis to guide the next stage of the research, fieldwork using participatory mapping techniques.

Subsequently, a collective mapping exercise was designed with the participation of ten women, aged between 20 and 60 years, in the Lavapiés neighbourhood (Centro district, Madrid), selected for their high perception of insecurity. It is intended to emphasize that the scale of the study area —limited to the neighbourhood of Lavapiés within the central district— makes this qualitative sample of ten people relevant, since the objective is not statistical extrapolation, but the identification of spatial patterns of perceived insecurity and the construction of sensitive cartographies capable of dialoguing with the objective analyses, in an analogous way to other parallel studies [

37]. In this sense, a sample of 10 women allows balancing the depth of the fieldwork (accompanied tours, individual files, associated narratives) with the logistical feasibility of the exercise, while guaranteeing a level of detail and a manageable volume of information for analysis and cartographic integration.

The fieldwork was carried out on 23 November 2024 in two different time slots, organized in two groups of five participants to capture temporal variations in the nighttime experience. In this way, the first group made up of five women carried out the activity at 8:00 p.m., while the second group, also made up of five participants, carried it out at 0:00 a.m.

Giving their explicit consent for the processing of the data, each participant completed an individual registration form that collected:

Basic personal information.

Mobility behaviours in the district.

Base plan of Lavapiés, on which he had to trace a free itinerary (maximum five minutes on foot) and identify five significant points related to the perception of security/insecurity.

The route, the selection of the route and the recording of perceptions (

Figure 5a,b) were carried out individually, allowing a diverse subjective reading of the urban space to be obtained.

Data Processing and Mapping

From the set of routes recorded, three representative itineraries were selected for cartographic representation, considering the coverage of main roads and spatial variety.

The cartography was elaborated from:

Objective basis: Street mapping, public lighting, parking areas, urban waste areas and opening hours of commercial premises (sources: Municipal Geoportal, Electronic Headquarters of the Cadastre and Open Data of the Madrid City Council).

Subjective information: Qualitative data recorded in the files of each participant.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) tools were used for the integration and processing of the data, using specific symbology (icons) to represent key aspects such as the presence of people, the premises open at night, the availability of public transport, the existence of green areas, the level of lighting and the degree of dirtiness (

Figure 6).

This method was conceived as the basis for the development of a future digital platform accessible by QR code, aimed at the collaborative collection of female urban experiences, aimed at improving perceived safety through the visualization and exchange of information.

3.3. Sensitive Cartography Results

With the aim of delving into the subjective dimension of the perception of urban security, and from a feminist perspective that places women’s differentiated experiences at the centre, a sensitive mapping methodology was developed in this work, aimed at capturing the individual nuances of the experience of public space.

This sensitive cartography is characterized by being a situated, feminist representation directly linked to experiences, emotions and perceptions in everyday interaction with the environment. Although its intensive nature limits its direct extrapolation to large scales, its value lies in offering a qualitative, deeply contextualized and situated reading of phenomena that cannot be captured by purely objective methods. For this reason, and in coherence with the multi-scale approach adopted in this research, it is integrated as a complementary methodological tool that enriches the spatial analysis.

Although the work starts from a detailed scale (urban microscale), its scalability to broader contexts is considered through digital tools such as ArchGIS Survey123 (v. 3.21.66, 2025), a platform for capturing georeferenced data and dynamic forms. This strategy facilitates the dynamic transition from a neighbourhood scale to a higher one, facilitating their interrelation and feedback between the two, especially in phenomena such as female night-time mobility. Thus, it is possible to build sensitive cartographies at the neighbourhood, district or urban level, always preserving the inductive, experiential approach and with a gender perspective.

The research applies this methodological path, which allows a more refined analysis of the factors that shape the perception of safety in night-time urban environments, on the mobility layer already addressed in point 3.1.1., although its versatility is applicable to the rest of the layers. The exercise has been designed and carried out using specific techniques, adjusted to the nature of the dimension analyzed, allowing the construction of a collective spatial narrative that manifests experiences traditionally invisible in conventional urban approaches.

Sensitive Cartography of Mobility

The results of the sensitive mapping of mobility highlight how night trajectories in the central district not only respond to the available infrastructure, but also to the emotions aroused by certain routes. The exercise is based on the experience of a user during a night bus journey, recording her journey from the exit of an establishment to her final destination. Specifically, the experience that is mapped is that of a young woman who leaves the Virata bar on Calle Olivar nº 32 and who takes the M-1 bus to reach the Embajadores’ square roundabout (see

Appendix A to read the full tale of the route).

In accordance with the aforementioned methodology of Víctor Cano, a cartography is elaborated using the linear stroke as a form of sensible representation [

38]. An object scale is used, centred on the interior of the bus as a micro-space for analysis, which allows not only to reflect the physical layout of the route, but also to map the emotional perceptions linked to each section. Aspects such as exterior lighting, the density of occupation of the space, the profile of the people present (especially in terms of gender and age group) and visibility at transit points are recorded and georeferenced. Through this methodology, it seeks to offer a sensitive, qualitative and situated reading of the nocturnal urban space, allowing us to understand how mobility and public space are experienced in a differential way by women.

The construction of this cartography incorporates the inductive and multi-scalar approach previously worked: it starts from the bus scale (object scale) but can be projected towards a more far-reaching reading, identifying critical sections or areas of vulnerability in the transport network as a whole. In this way, the cartography of mobility not only highlights the perceived risks or discomforts, but also reveals the spatial strategies adopted by women in their movements, thus integrating the principles of feminist mobility and sensitive to the nocturnal urban context.

From the subjective perspective, the participants of the collective mapping stated that walking at night is conditioned by lighting, visibility and the presence of people on public roads. A clear avoidance of narrow or little-travelled streets was observed, and a preference for avenues with active storefronts, terraces or continuous pedestrian traffic. Participants mapped out longer alternative routes, prioritizing “safe” routes over “fast” routes. This avoidance strategy reveals how urban design can condition autonomy and freedom of movement (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The cartographic synthesis elaborated from the superposition of the four layers of analysis—mobility, environmental quality, night-time uses and urban environment—allows to accurately identify areas of the urban fabric that present higher and lower levels of perceived safety, especially in the night-time context and from the situated experience of women in public space (

Figure 8). This methodological integration, of an inductive and situated nature, translates into a visual representation through points, which allows us to clearly observe the spatial contrasts in the nocturnal experience of the city.

The so-called green points emerge from the positive convergence of these indicators: presence of well-lit and active pedestrian mobility networks at night, well-preserved and perceptively pleasant plant environments, functional diversity with constant activity beyond business hours, and a well-cared-for, clean urban environment with adequate lighting infrastructure. In this analysis, the surroundings of Ópera and Chamberí stand out, where these conditions converge and favour a safer, more accessible and comfortable experience of public space. These areas can be considered urban references, useful for the formulation of replicable strategies aimed at improving night-time habitability from a feminist approach.

In contrast, the red dots indicate those spaces where one or more of the factors analyzed are deficient: limited mobility or with poor visibility, degraded or poorly maintained green areas, low night-time activity or functional monoculture, and obsolete or neglected urban infrastructures. In this study, the areas of Lavapiés and Huertas concentrate a high density of these red spots. The overlapping of urban voids, insufficient lighting, lack of diverse night-time uses and feelings of lack of protection make these neighbourhoods priority areas for intervention, where action is urgently needed to reverse the conditions that reinforce the perception of insecurity.

The results derived from the second methodology, based on a collective mapping exercise carried out in the centre of Madrid between 8:00 p.m. and 00:00 a.m., allow us to delve deeper into the subjective perception of safety of women in the night-time public space. This methodology combined cartographic representation with participatory dynamics, which facilitated not only the location of critical areas, but also collective reflection on the factors that condition the urban experience from a gender perspective.

The pre-mapping phase, developed through a structured survey, allowed for the collection of a significant database on everyday experiences, specific needs and sensations associated with nighttime travel. Through the analysis of the responses, shared patterns of behaviour and perception were evidenced, related to the uses of public space, preferential transit schedules, typologies of routes and subjective safety criteria. This information was essential to contextualize the results of the collective mapping, by identifying certain points of convergence in the spatial experience of the participating women.

During the mapping activity, participants identified, through simple iconography and accessible visual language, those places that they associated with positive or negative experiences in relation to safety. Among the most recurrent factors associated with negative perceptions are the poor quality of public lighting, the accumulation of waste, the deterioration of street furniture and the presence of people who generate discomfort or suspicion. These elements were identified as key indicators of urban vulnerability, not so much because of their materiality in themselves, but because of the social and symbolic imaginary they activate in certain spatial and temporal contexts.

The analysis of the results made it possible to verify that the presence or absence of people in public space operates as a determining factor. Lively areas, with continuous pedestrian traffic, open premises with guaranteed visibility, were perceived as safe environments. On the contrary, empty, poorly lit or abandoned spaces generate an experience of lack of protection and exposure. Significantly, participants highlighted how the combination of cleanliness, social density, and adequate lighting contributes to building environments of trust, while their absence reinforces feelings of insecurity.

The exercise also made it possible to identify and spatially represent positively valued points, associated with dynamics of social accompaniment and urban vitality, as well as critical points where perceived risk factors are concentrated. This sensitive cartography not only makes visible the physical conditions of the environment, but also provides a situated reading of urban emotions, showing how the nocturnal city is experienced unevenly depending on gender, context and time.

In summary, this methodology showed that the elements that have the greatest impact on the perception of safety are not necessarily those that appear in urban design manuals, but those that affect legibility, habitability and the symbolic appropriation of space. The incorporation of women’s experiential knowledge, translated into a collaborative graphic representation, constitutes a valuable tool for urban planning with a gender approach, making it possible to detect urban voids not registered by exclusively technical methodologies and to propose improvement strategies adjusted to the real needs of the users of public space. The research also shows that diagnoses of insecurity cannot be approached as a homogeneous experience. Although there are urban factors that generate insecurity in a way that is shared by the general population, it is women who experience certain risks associated with harassment and gender violence more acutely, which makes a qualitative difference in the experience of the night-time public space.

The third cartography developed within the framework of this study focused on delving into the personal dimension of the perception of safety, based on a representation of subjective data from an experience applied to the mobility layer. In this way, pedestrian and bus trajectories were mapped using lines and diagrams at object scale, collecting variations in emotional perception along the route. The analysis showed a marked sensitivity to the presence of people—especially unknown men—which, depending on the context, can generate both a sense of protection and a sense of threat. This ambivalence shows that the human presence in public space is not perceived in a homogeneous way, but is mediated by the spatial disposition, the behaviour of individuals and the ability to anticipate reactions in contexts that are not very controllable. In contrast, it was observed that factors such as the visibility of the environment and homogeneous lighting generate a constant perception of safety, acting as material conditioning factors that modulate the emotional experience of the journey.

The subjective analysis carried out using sensitive mapping made it possible to establish clear spatial distinctions between areas perceived as safe and others that generate discomfort or insecurity, as well as to identify the factors that underlie these perceptions. The former are characterized by adequate lighting, the active and continuous use of public space and the presence of a diversity of people. The latter, on the other hand, are defined by low visibility, nighttime inactivity and the physical deterioration of the environment. Although the study has focused on a small number of participants and on a specific spatial area, this focused scale has facilitated the development of a detailed diagnosis consistent with the objectives of the research. However, it is recognized that future research could expand the sample and consider comparisons with other genders, which would enrich the understanding of differences in the perception of nighttime space and contribute to validating the applicability of the methodology in diverse urban environments.

This methodology, by explicitly incorporating the emotions, sensations and experiences of a specific user, reveals layers of meaning that are usually absent in conventional urban diagnoses, and provides fundamental keys to a comprehensive understanding of the night-time space from a gender perspective. This work projects a horizon of research and action that transcends the specific case of the Lavapiés neighbourhood or the central district of Madrid, proposing a cartographic methodology that can be replicated and adaptable to other urban contexts.

5. Conclusions

The research has addressed the problem of urban security from a feminist perspective, focused on the experience of women in the night-time public space of the central district of Madrid. Through a mixed methodology that combined quantitative (spatial analysis using GIS) and qualitative (collective mapping and sensitive cartography) tools, it has been possible to make visible the multiple dimensions that make up the feeling of (in)security in the urban environment, as well as its structural and territorial causes. The articulation of both approaches has also made it possible to establish a clear difference between the population’s perception of global security and that specific to women. While the objective data reveal common deficits that affect citizens as a whole—such as inequalities in lighting, discontinuities in mobility or shortcomings in urban maintenance—the integration of the qualitative dimension shows how these same factors translate into particular risks linked to harassment and gender-based violence.

The crossover between objective and subjective promotes the development of a detailed and situated diagnosis of the territory, which transcends the methodologies of the official analytical cartography of the field of action, which transcends official maps and puts daily experiences at the centre. This approach has revealed a structural disconnect between the planned city and the lived city, where traditional urban analysis tools are insufficient to capture the gender inequalities that operate in space.

One of the main contributions of this work lies in demonstrating that urban insecurity is not explained only by material or criminal variables, but is deeply linked to the symbolic, social and emotional configuration of the space. The perception of risk is built from a complex network of factors that includes lighting, the vitality of the environment, the type of uses present, the quality of urban furniture, and pedestrian density, among others. However, this research has also made it possible to verify that there is a substantial difference between the dangers perceived generically by the population and those that predominantly affect women. While certain urban deficits generate insecurity in a broad sense, in the case of women a specific dimension linked to the risk of harassment and gender violence is added, which turns uncomfortable spaces into restrictive scenarios. Thus, it has been shown that women develop adaptation strategies—such as avoiding certain journeys, modifying schedules or walking accompanied—that limit their freedom of movement and condition their right to the city.

Likewise, the work has demonstrated the methodological value of incorporating participatory and expressive techniques such as sensitive mapping and collective mapping. These tools not only enrich the analysis, but also empower the participants, generating collective and horizontal knowledge that can be used as a legitimate input for urban decision-making. The articulation between objective data and situated perceptions has made it possible to highlight not only material shortcomings of the urban space, but also the way in which these become differential limitations for women. Thus, the method contributes to showing that insecurity does not operate uniformly but is intertwined with social structures that produce spatial inequality by gender.

Based on the approach adopted in this research, various future lines of work are opened that allow us not only to deepen the results obtained, but also to move towards urban models that are fairer, more inclusive and sensitive to the diversity of experiences in public space. These lines should not be understood as closed proposals, but as open horizons that invite the co-creation of knowledge between disciplines, technical knowledge and lived experiences, articulating a more democratic and empathetic urban approach.

Firstly, a territorial and temporal extension of the study is proposed, which allows the methodology applied to other neighbourhoods of Madrid or to cities with similar socio-spatial characteristics to be scaled. This comparative approach would facilitate the identification of common or divergent patterns in relation to the perception of safety, contributing to a better contextualization of the results and the formulation of recommendations adapted to different urban realities. In addition, it is proposed to incorporate a temporal dimension in the analysis—of a diachronic nature—that allows the evolution of the perception of security to be evaluated over time, particularly after the implementation of urban interventions or regulatory modifications, which would provide a dynamic understanding of the phenomenon.

Secondly, the methodological reinforcement of subjective mapping is considered relevant, through the inclusion of new variables related to perception, such as the feeling of control over the environment or the level of anxiety experienced in situations of prolonged waiting in poorly lit environments. This expansion would allow for more accurate capture of the affective complexities that make up the urban experience at night and enrich diagnoses based on qualitative and sensitive data. Another possible way to incorporate this into the study lies in carrying out a comparative exercise of subjective perception between different genders, which could provide a more nuanced understanding of how insecurity is experienced based on diverse identities, identifying both the common elements and the specific differences that cross the experience of the nocturnal urban space. At this stage, it is appropriate to point to a consideration of the size of the sample of inhabitants chosen for collective mapping. Although it has already been pointed out that the object of the research did not foresee the achievement of statistical values, it is pertinent to consider that, to avoid possible limitations and biases in the results, the population involved in the study should be increased. For further research, it would be pertinent to expand the scale of analysis and diversify the sample of participants, incorporating comparisons between genders and between different urban contexts. In this way, the methodology presented could be tested in broader scenarios, consolidating its potential as a tool to understand the links between urbanism, gender and security.

In a third way articulated with the previous one, it is necessary to consider the integration of technology in spatial analysis. Although the incorporation of tools such as artificial intelligence, big data analysis or the use of urban sensors makes it possible to develop predictive models capable of anticipating risk areas based on historical patterns of perception and criminality, offering massive and apparently accurate representations of the territory, they often make invisible the social and political mechanisms that produce space and reproduce inequalities. The methodology presented in this research stands as an alternative to this trend, by placing at the centre the articulation between objective data and situated experiences, with the purpose of evidencing the structural conditions that generate urban insecurity. Thus, rather than relying on technological sophistication, the approach proposed here highlights the critical capacity of multi-scale analysis and the intersection with feminist approaches, pointing out that the real challenge lies not only in measuring the city, but in understanding how it is built and who benefits or is excluded in its material and symbolic configuration.

As a fourth axis, experimentation with spatial interventions is proposed based on the results of the analysis, using tactical urbanism strategies aimed at improving lighting, street furniture, visibility or cleaning of critical points identified by the participants. It is necessary to qualify the usual interpretation that associates safety only with clean streets, furniture in good condition and intense lighting. The physical deterioration of public space acts not only as a functional obstacle, but also as a social sign that transmits institutional abandonment and inequality, projecting imaginaries of risk that reinforce the feeling of vulnerability. On the contrary, maintained urban environments, linked to middle-class dynamics, tend to communicate order and predictability, which is culturally interpreted as a lower level of threat. This reading shows that policies focused on “beautifying” or “brightening more” spaces are insufficient if the structural causes of urban inequality are not addressed.

Rather than being limited to providing routine recipes, since this research is focused on the application of a cartographic analytical methodology, the recommendations of this work aim to question the structural mechanisms that produce spatial inequality in the nocturnal city. Cartographic evidence shows that the deficits are not accidental or the result of isolated imbalances, but the result of urban planning decisions and economic dynamics that concentrate resources in areas of tourist centrality while making residential neighbourhoods precarious. For this reason, rather than betting only on tactical interventions or proximity formulas, a comprehensive strategy is proposed that articulates three levels: an equitable redistribution of night-time urban resources (lighting, transport, cultural uses) that breaks with the logic of concentration in commercial axes; a critical review of the regulatory frameworks that regulate the use of public space, incorporating gender criteria in the planning of schedules, licences and night-time activities and, finally, the construction of governance devices that allow the affected groups to participate in decision-making beyond the neighbourhood scale, in a binding and structural way. In this way, the recommendations are not reduced to specific interventions but are conceived as mechanisms to dispute the very production of urban space and move towards a more inclusive and fair night-time city.

In relation to mobility, a line of work is suggested focused on the design of safe routes with a gender approach, which guarantee connectivity, universal accessibility and the continuity of urban space during night journeys. This type of planning would make it possible to respond directly to the demands expressed by public transport users and to reinforce confidence in the use of the city outside of daytime hours.

Another strategic dimension is linked to citizen participation and advocacy in urban policy. In this sense, the creation of participatory digital platforms that allow reporting, collaboratively and in real time, situations of perceived insecurity is proposed. This type of tool would facilitate the construction of a community surveillance system based on the direct experience of citizens and would strengthen the processes of co-production of urban knowledge. At the same time, it is necessary to systematically incorporate the gender approach in urban planning regulations, requiring that all actions on public space explicitly consider their impact on safety from an inclusive perspective. Likewise, it is suggested to work with local networks of collaboration between neighbourhoods, businesses and associations to consolidate an urban culture based on proximity and co-responsibility.

It also highlights the importance of establishing mechanisms for impact assessment and monitoring of results. To this end, the design of specific indicators is proposed to measure how urban interventions affect the perception of safety in the short, medium and long term. This evaluation would be enriched by comparing it with international reference experiences, identifying replicable elements and good practices adaptable to the local context. At the same time, it is considered essential to incorporate an intersectional approach, which allows for analyzing how variables such as age, origin, socioeconomic level or gender identity condition the spatial experience and the perception of risk in the urban environment.

Finally, the emotional analysis of urban space through biofeedback and physiological sensors is pointed out as an emerging line, which would allow people’s bodily responses—such as heart rate or skin conductance—to be recorded in different urban environments, particularly at night. This approach would make it possible to draw up maps of emotional intensity that complement subjective narratives and quantitative data, opening new ways for the design of spaces that minimize urban stress and enhance feelings of comfort, control and security.

All in all, these lines of work project a horizon of research and action that transcends the specific case of the Lavapiés neighbourhood or the central district of Madrid, proposing a methodology that can be replicated and adaptable to other urban contexts. The combination of technological tools, citizen participation, spatial intervention and critical analysis of regulatory frameworks constitutes a powerful methodological path that can be applied in cities of different scales—from large metropolises to intermediary cities—adjusting the availability of data, technical resources and the degree of community involvement. Replicability requires, however, particular attention to the cultural, social and institutional specificities of each place, so that the methodology is deployed as a flexible framework and not as the imposition of a standardized model, being able to expand the diversity of profiles in collective mapping exercises to move towards safer and equitable cities.

Ethics on data collection: The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The data collection protocol was carried out strictly from a research perspective, without the inclusion of personal or sensitive data—whether sensitive or non-sensitive—from the voluntary participants. Consequently, the collection of personal data is not defined within the scope of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in any of its aspects. Given the absence of identifiable information, the lack of any form of physical or psychological intervention, and the voluntary, informed nature of participation, the study does not fall under the categories that would require prior ethical review or formal consent as defined by the Declaration. Nonetheless, its principles regarding transparency, respect, and minimization of risk have been fully observed. This study is framed within the academic and research obligations of the Master’s Degree in Urban Design and Sustainable Mobility at the School of Architecture of the Universidad Europea de Canarias and entails the public dissemination of results as part of its commitment to knowledge transfer.