Abstract

Against the backdrop of China’s large-scale collective forest tenure reform, examining the actual effects of land policies at the household level is crucial for advancing sustainable forestry. This study aims to comprehensively analyze the impacts of tenure formalization (forest tenure certificates) and market-based incentives (bamboo forest certification) on household production inputs and harvesting behavior by disentangling the objective implementation of policies from households’ subjective perceptions. Based on survey data from 1090 households in Fujian Province, China, and employing double-hurdle and Tobit models, this study reveals a central finding: households’ management decisions are driven more strongly by their subjective perceptions than by objectively held policy instruments. Specifically, perceived tenure security serves as a key incentive for increasing production inputs and adopting long-term harvesting plans, whereas the mere possession of forest tenure certificates exhibits limited direct effects. Similarly, households’ positive expectations about the market value enhancement from bamboo forest certification significantly promote investments and sustainable harvesting practices—an effect substantially greater than that of mere participation in certification. Consequently, this study argues that the successful implementation of land governance policies depends not only on the rollout of instruments but, more critically, on fostering households’ trust and positive perceptions of policies’ long-term value.

1. Introduction

Within the global context of sustainable forestry transition, effectively motivating small-scale operators—especially vast numbers of rural households—to enhance their engagement and investment has become a critical challenge for forestry policies in developing countries [1,2]. As one of the nations with the most profound collective forest tenure reforms globally, China has consistently advanced tenure formalization and the adoption of sustainable forest management instruments since 2003 [3]. Throughout this process, property rights, institutional arrangements, and market-based incentives have been vested with high expectations. Policy instruments such as tenure certification and forest certification aim to stimulate household investment and eco-friendly practices, thereby achieving synergy between ecological conservation and livelihood improvement [4,5,6]. However, the translation of policy instruments’ “intended objectives” into “household responses” relies not only on the supply of institutions themselves but, more fundamentally, on households’ subjective perceptions and behavioral response mechanisms [7,8,9].

On the one hand, collective forest tenure reform attempts to provide households with long-term operational certainty through the issuance of forest tenure certificates. Theoretically, this should reduce investment risks and enhance forestry investment incentives [5]. On the other hand, market-based incentives like forest certification endeavor to guide households toward more sustainable management practices while strengthening their value-capturing capacity within industrial chains [10,11,12]. Nevertheless, existing research predominantly focuses on “whether institutional instruments are effectively implemented” [13,14], paying insufficient attention to “how they are perceived, whether they are trusted, and whether they translate into tangible actions”. Empirical evidence reveals a significant “perception gap” between institutional supply and household response, substantially diminishing policy effectiveness at the micro-level [15,16,17]. This points to a fundamental inadequacy in conventional policy thinking, which often implicitly assumes a direct, rational link between the provision of a formal instrument and a desired behavioral change. The critical issue is, therefore, not to confirm the self-evident premise that “perception matters” in human decision-making, but to address a more pressing empirical question with profound policy implications: What is the relative importance of the objective institutional instrument versus the subjective perception in driving behavior? Answering this question is essential for understanding why well-intentioned policies often fail and how to design more effective interventions.

Thus, clarifying the relationship between the “perception pathways” and “behavioral outcomes” of institutional instruments necessitates an in-depth exploration of both objective and subjective dimensions of institutional incentives. Specifically, forest tenure certificates—as a core manifestation of tenure formalization—may promote households’ long-term investment behaviors primarily through their subjective perception of tenure security. Similarly, bamboo forest certification (as an application of forest certification in the bamboo sector) likely exerts its incentive effects via households’ expectations and perceptions of its market value.

Against this backdrop, this study selects Sanming City, Fujian Province, China, as its research area. Drawing on micro-level survey data from 1090 households and adopting dual analytical dimensions—objective institutional arrangements and subjective perceptions—it systematically evaluates the impact pathways of tenure formalization and forest certification on households’ bamboo forest investment and harvesting behaviors. By constructing double-hurdle and Tobit models and incorporating perception variables to identify mechanisms, this paper addresses a central question: Are households’ forestry behaviors driven by “passive compliance with institutional arrangements” or “active response to institutional perceptions”? Furthermore, it aims to reveal how perception construction serves as a critical prerequisite for policy incentive effectiveness in sustainable forestry institutional design.

This study makes three interrelated contributions: first, it disputes the effects of institutional instruments along subjective perception and objective possession dimensions, offering a novel theoretical perspective for forestry policy evaluation; second, it develops a dual perception variable system and behavioral response models to provide empirical evidence for identifying effective institutional incentive mechanisms; and third, based on micro-level evidence, it proposes actionable recommendations for policy communication and perception construction to enhance the practical performance and sustainability of forestry policies.

2. The Literature and Theoretical Review

2.1. Tenure Formalization and Forestry Management Behavior

Collective forest tenure reform is widely recognized as a pivotal institutional arrangement for advancing marketization and sustainable management of China’s forestry sector [3]. Its core objective is to enhance households’ perceived tenure security by clarifying property boundaries, thereby stimulating production inputs and long-term management commitment [18]. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that tenure formalization reduces the risk of forestland reallocation, stabilizes expectations regarding output rights and disposal rights, and significantly increases investments of capital, labor, and technology in forestland [6,19]. Concurrently, it establishes an institutional foundation for forestland mortgage financing and transfer transactions, facilitating access to external capital and optimized resource allocation [20,21]. Regarding harvesting behavior, tenure formalization often incentivizes households to extend harvesting cycles to capture value appreciation, reflecting a stronger commitment to sustainable management [22].

However, scholars note that formalization does not invariably translate into significant incentives; its efficacy hinges on whether tenure security is genuinely internalized at the household level [23]. In some regions, despite possessing forest tenure certificates, households’ limited trust in institutional enforcement and concerns about policy instability constrain investment incentives [24,25]. This suggests that institutional perceptions may exert stronger behavioral influence than objective possession.

2.2. Forest Certification and Eco-Friendly Management

As a market-based incentive tool led by non-state actors, forest certification promotes sustainable forestry practices through environmentally conscious production standards and certification systems [10,11,12]. Research indicates that certification not only enhances product market bargaining power and export competitiveness [12] but also constrains harvesting behavior via institutionalized management criteria, thereby advancing long-term forest conservation and ecological goals [26,27]. For households, market signals and income-boosting expectations transmitted by certification constitute the primary mechanism motivating participation in sustainable management [12,28].

However, some research indicates that forest certification does not yield significant material wealth [29] or affect deforestation [30]. This suggests that relying on “behavioral participation” alone may lead to policy failure, highlighting the often-overlooked role of “perception construction”. In essence, a household’s decision to adopt higher-standard practices depends more on their belief in the certification’s ability to deliver price premiums and improve market access, rather than on mere participation [28,31].

This positive perception transforms a farmer’s management strategy from short-term, high-intensity extraction to long-term sustainable yield management. This shift often manifests in a specific harvesting pattern: more frequent but lower-volume selective cutting. This behavioral logic is twofold. First, from an economic perspective, it reflects a transition toward seeking a continuous and stable income stream, akin to earning a regular salary, rather than a one-time, high-risk windfall. Second, it signifies an internalization of the sustainable management principles required by certification standards themselves, which often mandate or encourage selective cutting to maintain forest health and ecological integrity. This nuanced approach moves beyond simple compliance to a deeper alignment with the philosophy of sustainable forestry.

2.3. Mechanism Analysis and Hypothesis Development

Integrating these dimensions reveals a key mediator in institutional incentives: subjective perceptions. The function of property rights institutions lies in constructing stable long-term expectations—not merely “certificate possession”; the efficacy of forest certification resides in shaping market value expectations—not binary “participation status”. This “perception-over-possession” logic has gained prominence in recent studies on institutional effectiveness and behavioral mechanisms [2,32,33]. This concept resonates with broader social science theories. In institutional economics, for instance, subjective perceptions can be understood as powerful “informal institutions” that often shape behavior more directly than formal rules [34]. Similarly, from a behavioral economics perspective, this aligns with concepts like “mental accounting”, where the subjective value and cognitive frame an individual assigns to an asset (the ‘perception’) dictates their subsequent actions, rather than its objective form alone [35]. Prevailing research often treats institutional variables as “exogenous inputs”, neglecting individuals’ interpretive processes and trust-building—an approach inadequate for precision-oriented policy analysis.

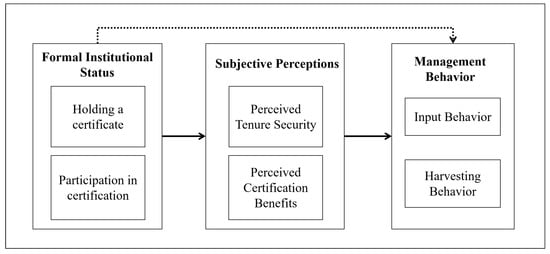

Accordingly, this study adopts the dual-dimensional conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 1 to analyze the distinct impact pathways of tenure and certification. This framework deconstructs each institutional instrument into two core components, allowing us to test our central “perception-over-possession” hypothesis. For tenure, we differentiate between the Objective Tenure Status—the formal, de jure possession of rights, operationalized as holding a government-issued certificate—and the Subjective Tenure Perception, which captures the household’s de facto sense of security. In parallel, for forest certification, we distinguish the Objective Certification Status, defined as formal participation in a program, from the Subjective Certification Perception, which reflects the household’s belief in the program’s market and ecological benefits. This precise conceptualization forms the basis for the hypotheses proposed below.

Figure 1.

Policy–Perception–Behavior response model. This model illustrates how formal institutional status (e.g., holding a certificate) influences management behavior primarily through the mediating pathway of farmers’ subjective perceptions (e.g., perceived security). The solid arrows indicate the significant indirect pathway investigated in this study, while the dotted arrow represents the generally non-significant direct pathway.

H1.

Stronger perceived tenure security positively correlates with higher household production input intensity.

H2.

Stronger perceived tenure security positively correlates with extended harvesting cycles and increased harvesting volume per extraction.

H3.

Stronger perceived benefits of bamboo forest certification positively correlate with higher household production input intensity.

H4.

Stronger perceived benefits of bamboo forest certification positively correlate with shorter harvesting intervals but reduced harvesting volume per extraction.

Through empirical testing of these hypotheses, this study aims to (a) unveil the micro-level transmission logic of institutional incentives in household decision-making; (b) emphasize the critical role of perception variables in evaluating institutional performance; and (c) provide evidence for designing behavior-oriented forestry policy systems.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Research Area and Survey Methodology

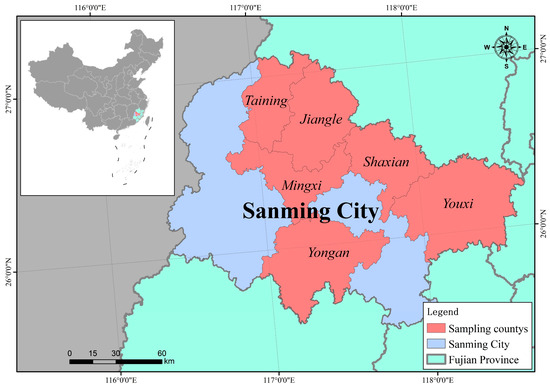

This study selects Sanming City, Fujian Province, China, as the case study area (as shown in Figure 2). The selection of this site was purposive, based on two key criteria: its status as China’s renowned “Bamboo Capital”, ensuring high resource endowment, and its role as a “National Comprehensive Reform Pilot Zone for Collective Forestry”, ensuring advanced institutional innovation. This unique combination renders it a particularly suitable case study area for examining the impacts of tenure formalization and bamboo forest certification.

Figure 2.

Location of the survey area.

The primary data were collected using a multi-stage stratified sampling design. The process was as follows: First, we purposively selected six key counties with highly developed bamboo industries from within Sanming City (Yong’an, Youxi, Jiangle, Sha, Taining, Mingxi). Second, within each selected county, we purposively chose 2–3 townships that serve as centers of the local bamboo economy. Third, for the final stage of household selection, we obtained official and comprehensive household rosters from the local village committees, which served as our sampling frame. From these lists, we employed a systematic random sampling method to select the households for our survey.

Field surveys using face-to-face interviews were conducted during March and June–July 2021 by a team of experienced researchers in forestry economics. This process yielded 1090 valid questionnaires from the structured survey, representing a 94.29% validity rate, with rigorous cross-verification protocols ensuring data reliability.

3.2. Data Analysis Strategy

3.2.1. The Double-Hurdle Model for Input Behavior

Household production input behavior constitutes a classic two-stage decision process: first determining whether to invest (participation decision), then deciding how much to invest (intensity decision). Conventional econometric models often fail to effectively disentangle these interrelated stages. While the Heckman two-step model is widely applied to such double-hurdle decisions, its core assumption—that error terms across stages are correlated—may induce sample selection bias if unobserved factors from the first-stage selection equation propagate into the outcome equation.

To overcome this limitation, this study employs the double-hurdle model [36], which refines the Tobit framework by decomposing input decisions into two independent sequential stages: the first hurdle governs investment participation, while the second determines investment intensity. Crucially, this specification (1) allows for distinct determinants for each decision stage, (2) assumes independent error terms across stages, and (3) eliminates bias from error-term correlation. Consequently, the model more accurately reflects actual household decision-making processes while enhancing econometric robustness.

Specifically, the first-stage Probit equation for input participation is specified as follows:

where indicates whether the household engages in investment behavior; is a vector of explanatory variables, including perceived bamboo certification and perceived tenure security, and represents the corresponding parameters to be estimated. Equation (1) captures the case where the household makes no investment, while Equation (2) applies when investment occurs. The function denotes the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.

The second-stage equation for the intensity of household investment is constructed as follows:

where denotes the conditional expectation, representing the intensity of household investment; is the inverse Mills ratio; is a vector of explanatory variables, including perceived bamboo certification, perceived tenure security, as well as control variables such as the household head’s gender and age; denotes the parameters to be estimated, and represents the standard deviation of the truncated normal distribution.

Based on Equations (1)–(3), the corresponding log-likelihood function can be constructed as follows:

where denotes the value of the log-likelihood function, and all parameter estimates are obtained through maximum likelihood estimation.

3.2.2. The Tobit Model for Harvesting Behavior

The Tobit model is a regression approach designed for situations in which the dependent variable is censored. In this study, both the harvesting interval and the ratio of harvesting volume to planting volume are considered censored variables: harvesting intervals among bamboo farmers typically range from 2 to 6 years, and the harvest-to-planting ratio generally falls between 0 and 1. Therefore, the Tobit model is appropriate for analyzing these outcomes. The model is specified as follows:

where denotes either the harvesting interval or the ratio of harvesting volume to planting volume for household i; is a vector of explanatory variables; is the coefficient vector, and the error term is assumed to be independently and normally distributed as follows: .

After specifying the Tobit model, the next step is to estimate and . Let and denote the probability density function and cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, respectively. The conditional expectation of , given that , is

Thus, the observed dependent variable can be expressed as

Since is not independent of , using ordinary least squares (OLS) would result in biased and inconsistent estimates. Therefore, the parameters of the Tobit model are best estimated using maximum likelihood estimation. Let and , then the probability that is

The likelihood function is expressed as

To estimate the parameters of the Tobit model, maximum likelihood estimation is employed by solving the following:

where is the log-likelihood function corresponding to the likelihood and is given by

3.2.3. Multicollinearity Test

Prior to model estimation, variance inflation factors (VIF) were used to assess multicollinearity. Results show the following: for the double-hurdle model, VIF values of independent variables range from 1.05 to 1.60 (mean = 1.14 < 10); for the Tobit model, VIF values range from 1.04 to 1.59 (mean = 1.15 < 10). Thus, no severe multicollinearity exists in the estimations.

3.2.4. Robustness Test

This study further tests the robustness of the estimation results by applying alternative estimation methods. For models originally estimated using the double-hurdle approach, we re-estimate them using Probit and Tobit models. For models initially estimated with the Tobit model, we use ordinary least squares (OLS) as an alternative. The corresponding estimation results are presented in the Supplementary Materials. The robustness tests show that the signs and significance levels of the key explanatory variables remain largely consistent, indicating that the original estimation results are robust.

3.3. Variable Definitions and Measurement

The dependent variable in this study is designed to comprehensively characterize farmers’ bamboo forest management decisions. Specifically, the measurement of forest management investment behavior follows a double-hurdle model framework. The first stage, the participation decision, is a binary dummy variable (0 = no investment, 1 = investment). The second stage, the intensity of investment, is measured as the total annualized monetized value of land, labor, and capital inputs per unit of area (mu). For this calculation, land input is monetized using the local rental rate per unit area, and labor input is monetized using the average local wage rate. Concurrently, harvesting behavior—operationalized through harvesting intervals (years) and harvest intensity (ratio of harvested quantity to planted quantity)—serves as an additional dependent variable to assess sustainable utilization.

The core explanatory variables are bamboo forest certification and tenure security, each measured along both objective and subjective dimensions. The objective variable for bamboo forest certification is a dummy variable indicating whether a farmer participates in the certification system. The subjective variable is a composite index of perceived certification benefits, calculated as the mean score of three Likert-scale items (Table 1). Similarly, the objective variable for tenure security is a dummy variable for the possession of a forest tenure certificate, while the subjective variable is a composite index measuring the farmer’s perceived confidence in the stability and completeness of their tenure, likewise calculated as the mean score of three Likert-scale items (Table 1). This multidimensional measurement approach is intended to allow for a more in-depth analysis of the composite effects of formal institutional arrangements and individual subjective perceptions on farmer behavior.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

To mitigate omitted variable bias, controls encompass three domains: (1) household head characteristics (gender, age, education, village cadre status) and household attributes (labor force size, per capita annual income, cooperative membership); (2) forest plot features (average slope, distance to residence/roads); and (3) management/cognitive traits, including forestry income share, risk preference index, and perceptual constructs (management value, government support, market information access, climate change perception) measured through Likert-scales.

3.4. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

The descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in Table 1. The survey captures a profile of typical rural households in the region. The households are predominantly led by male (93.1%) household heads, with an average age of approximately 60 years and a formal education level beyond primary school (avg. 6.5 years). The average household has 3.4 members in its labor force, and a minority participate in specialized cooperatives (17.2%).

In terms of livelihoods, forestry plays a significant but varied role. Income from all forestry activities constitutes, on average, 15.14% of total household income. However, the high standard deviation (27.41) indicates substantial heterogeneity, with some households being highly dependent on forestry, while for others, it is a supplemental income source. The landscape of the study area is a characteristic subtropical mosaic, dominated by extensive bamboo forests that reflect the region’s status as China’s “Bamboo Capital”. Interspersed with these bamboo stands are other key land uses, including timber forests (such as Cunninghamia lanceolata and pine), tea plantations on terraced slopes, and small-scale rice paddies or vegetable plots in the valleys adjacent to village settlements.

As shown in Table 1, most households currently invest in forest management. The average input intensity for a full production cycle is 1772 yuan/mu. It is important to note that this figure is a comprehensive economic measure, including not only direct cash outlays (e.g., for fertilizer and hired labor) but also the imputed opportunity cost of the household’s own land and labor. The average harvesting interval is 3.76 years. The mean harvest-to-planting ratio is 0.369, indicating that households typically harvest approximately one-third of their bamboo stands every 3–4 years. Participation in bamboo forest certification remains limited (average certified area: 8 mu), though households’ perceived certification benefits are relatively high (mean score: 3.8). Regarding tenure security, over half of households possess forest tenure certificates, and most report strong perceived tenure security (mean score: 4.3). An overwhelming majority exhibit risk-averse preferences. For perceived management value, households rate self-use value moderately (mean: 2.7) but assign a higher value to environmental benefits (mean: 3.5).

4. Results

4.1. Impacts of Tenure and Certification on Household Inputs

Table 2 and Table 3 present double-hurdle model results for tenure security and bamboo certification effects on input behavior. Empirical findings indicate the following: (1) Possession of forest tenure certificates shows positive but statistically insignificant effects on both input participation and intensity; (2) Perceived tenure security significantly enhances input participation ( = 0.481 *) and investment intensity ( = 387.6 *) at the 1% level, supporting Hypothesis 1; (3) Bamboo certification participation demonstrates no significant direct impact on input intensity; (4) Perceived certification benefits significantly increase input intensity ( = 283.5 ***), validating Hypothesis 3. This confirms that certification incentives operate primarily through perceptual pathways rather than institutional participation itself. It is also worth noting that the significant influence directions of control variables such as risk preference and education level are consistent with existing theories and the literature findings, which increases the robustness and validity of our model setting.

Table 2.

Influence of tenure security on farmers’ investment in bamboo forest management.

Table 3.

Influence of bamboo certification on farmers’ investment in bamboo forest management.

4.2. Impacts of Tenure and Certification on Harvesting Behavior

Tobit model estimates (Table 4 and Table 5) demonstrate: (1) Forest tenure certificate possession shows no significant effects on harvesting intervals or harvest-to-planting ratios; (2) Perceived tenure security significantly increases harvesting intervals ( = 0.682 **) and harvest intensity ( = 0.184 *), validating Hypothesis 2—indicating enhanced security perception promotes longer-interval, higher-volume harvesting; (3) Bamboo certification participation exhibits no significant impact; (4) Perceived certification benefits significantly reduce intervals ( = −0.351 ***) and harvest intensity ( = −0.217 **), supporting Hypothesis 4—confirming that stronger certification perception shortens harvesting cycles and lowers volume per extraction, reflecting sustainable management adoption through heightened industry confidence.

Table 4.

Influence of tenure security on farmers’ logging behavior in bamboo forest management.

Table 5.

Influence of bamboo certification on farmers’ logging behavior in bamboo forest management.

5. Discussion

5.1. Perception over Possession: The Critical Pathway for Institutional Instrument Effectiveness

This study reveals that the incentive effects of property rights institutions and forest certification on household forestry behavior stem more from subjective perceptions than the objective existence of institutional arrangements. Our findings corroborate growing scholarly emphasis on cognitive pathways in policy implementation while empirically verifying perception-behavior causality at the micro-level. Although collective forest tenure reform has formally achieved tenure formalization, forest tenure certificate possession demonstrates no significant effects on input or harvesting behaviors. Instead, households’ expectations regarding future tenure stability—whether their rights will remain secure and uninterrupted—constitute the core determinant of decision-making.

This result provides strong support for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. The finding for H1 that perceived security significantly enhances production inputs is theoretically grounded in the idea that secure tenure reduces investment risks and stabilizes long-term expectations [5]. Our results show that this mechanism is activated by the farmer’s subjective belief, not the physical certificate, which confirms that policy effectiveness is contingent on genuine internalization at the household level. This aligns with existing evidence that formalization translates into investment incentives only when it strengthens perceived security [23,25].

For forest certification, an analogous mechanism operates: mere certification participation fails to significantly boost inputs or alter harvesting strategies. Conversely, households with positive expectations about certification’s market premiums, brand reputation, and ecological impacts are more likely to adopt long-term, orderly, and eco-conscious practices. This validates the behavioral logic proposed in Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 4. The support for H3 demonstrates that market-based incentives function through perceived economic benefits [31]. Farmers increase investment when they believe that certification will lead to tangible rewards like higher prices or better market access, confirming that the expectation of value capture is the primary motivator [12]. This perception-mediated institutional incentive resonates with findings on forest product certification, further underscoring the centrality of cognitive trust [4].

Collectively, policy instrument effectiveness depends not on institutional deployment or formal structures, but on whether instruments are perceived, understood, and internalized as behavioral references. Policy design and dissemination must, therefore, simultaneously advance institutional functionality and perceptual value construction through strategic information delivery, cognitive guidance, and value shaping—ensuring that tools evolve from paper-based designs to field-level actions.

5.2. Institutional Types and Behavioral Responses: Divergence in Long-Term vs. Short-Term Strategies

While the absolute perception levels observed in this study are sample-specific (as presented in Table 1), the core analysis concentrates on the behavioral implications of the variation in these perceptions. Further analysis reveals distinct temporal preferences and behavioral pathways in how property rights institutions and forest certification influence household management decisions. Perceived tenure security reinforces an asset-based logic, promoting longer-cycle, higher-intensity harvesting (as predicted in H2); conversely, perceived certification benefits guide households toward shorter-cycle, lower-intensity sustainable practices (confirming the outcome of H4). This institutional–behavioral alignment reflects fundamental differences in the operational logic of policy instruments.

Property rights institutions prioritize stability and predictability: by eliminating policy volatility and securing benefit entitlement, they bolster confidence in forestland as a long-term asset. Under this logic, households increase upfront investments and extend management cycles to capitalize on timber appreciation—a mechanism corroborated by Zhang and Song [22] and consistent with our validation of H2, where enhanced security perception promotes longer-interval, higher-volume harvesting.

In contrast, forest certification emphasizes market norms and ecological accountability, transmitting effects through improved market access and product premiums [26], thereby incentivizing adaptive, ecology-conscious management. This provides the context for our results supporting H4, where stronger certification perception encourages a sustainable yield approach with shorter harvesting cycles and lower volume per extraction. This finding adds a crucial nuance to the literature. While studies often confirm that certification promotes conservation goals and constrains overall harvesting [26,27], our results specify a precise behavioral mechanism for how this occurs at the household level: a shift to a more frequent, less intensive harvesting pattern. This demonstrates that different types of institutional perceptions can foster divergent, yet equally rational, sustainable management strategies, driven by the unique market and income expectations that certification creates [12,31].

Critically, uncoordinated differences in institutional objectives, temporal rhythms, and constraint intensities may cause strategy conflicts or incentive misalignment. Policy practice must, therefore, integrate tenure systems and market mechanisms through complementary designs that synchronize incentive timing and behavioral pathways. Combining institutional stability with market flexibility can guide households toward eco-efficient transitions that balance ecological protection and economic gains.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite rigorous econometric validation using large-scale Fujian survey data, this study has limitations. First, as institutional perception construction is dynamic and processual, our cross-sectional design cannot capture temporal perception–behavior evolution; future research should incorporate longitudinal surveys or experimental interventions to trace causal pathways.

Second, while controlling for key perceptual and social variables, unobserved external factors (e.g., policy interactions, social networks) may persist; we recommend integrating social network analysis (SNA) and psychological modeling to deepen institutional–behavioral inquiry. For instance, an SNA approach could model individual households as ‘nodes’ and the pathways of information sharing or trust as ‘links’. Such an analysis could reveal how a household’s structural position within the village network—such as their centrality or their proximity to trusted opinion leaders—shapes their perception of policy instruments like tenure security and certification, thereby influencing their behavioral responses.

Third, while our study demonstrates that subjective perception is more influential than formal status, it does not fully unpack the underlying reasons why these formal instruments underperform. Future research could build directly upon our findings by investigating these specific institutional and market-based mechanisms. For instance, regarding the forest tenure certificate, qualitative studies could explore whether its ineffectiveness stems from weak local government enforcement or a legacy of policy instability that erodes farmers’ trust in formal documents. Similarly, concerning forest certification, future studies could employ market-chain analysis to determine if the lack of behavioral change is due to insignificant market premiums or profit capture by intermediaries, which would clarify the poor actual participation experience for farmers.

6. Conclusions

Amid deepening collective forest tenure reform and expanding forest certification, understanding how institutional instruments influence forestry behavior through cognitive pathways is critical for ecological sustainability and policy efficacy. Based on large-scale household data from Fujian, China, this study disentangles objective possession and subjective perception dimensions of tenure security and bamboo certification, systematically evaluating their impacts on input and harvesting behaviors. Key findings reveal: the following

First, perceived tenure security significantly enhances input participation, investment intensity, and harvesting scales, while tenure certificate possession shows no significant effects. This confirms that tenure institutions incentivize behavior primarily by strengthening subjective security expectations—where perception proves substantially more influential than formal possession.

Second, perceived forest certification benefits significantly boost input intensity and promote sustainable harvesting through shorter intervals and reduced volume per extraction. By contrast, mere certification participation exhibits insignificant results. Forest certification’s efficacy thus depends on households’ positive cognition of market/ecological value—not symbolic compliance.

Third, tenure and forest certification manifest divergent temporal preferences: tenure security reinforces long-term asset logic, while forest certification perception fosters adaptive sustainability. This divergence necessitates complementary institutional designs that harmonize behavioral incentives to prevent strategic conflicts.

Our findings offer significant and actionable policy implications for institutional reforms in China and other developing regions. To move from passive policy implementation to active perception management, we propose the following concrete strategies:

First, to bolster perceived tenure security, policymakers must go beyond the administrative act of issuing certificates. A strategic communication plan is essential, utilizing accessible channels like local radio, community bulletin boards, and village-based social media groups (e.g., WeChat) to clearly articulate farmers’ rights and dispute resolution processes. Crucially, to build genuine trust and foster positive cognition, governments should establish demonstration households—showcasing successful farmers who benefit from secure tenure—and leverage influential rural social networks. Engaging respected village leaders and early adopters to share their positive experiences can be far more persuasive than top–down propaganda, ensuring the message is delivered by trusted sources.

Second, for market-based instruments like forest certification, a proactive approach to value shaping is critical. Instead of merely hoping for market recognition, certification bodies and local governments should guide farmers’ cognition by making benefits tangible and visible. This includes organizing targeted training on sustainable practices that align with certification standards, facilitating direct matchmaking between certified producers and buyers, and widely publicizing success stories of income growth through local media. These actions transform certification from a symbolic label into a clearly perceived pathway to economic and ecological rewards.

Finally, the divergence between long-term tenure logic and shorter-term certification incentives requires an integrated policy design. A concrete strategy is to position secure, long-term tenure as a foundational “gateway” to participating in advanced, high-value certification schemes. By structurally linking these policies—for example, making tenure verification a streamlined part of the certification application—governments can help farmers see how long-term stewardship and market opportunities are mutually reinforcing, thereby harmonizing motivations for both sustainable land use and immediate returns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14101979/s1, Table S1: Robustness test results.

Author Contributions

Y.H., conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation; writing—original draft preparation; Y.W., supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72404265).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

This study was conducted in strict adherence to ethical guidelines. All participants were provided with a comprehensive explanation of the research objectives and procedures prior to the interviews. They were assured that their participation was entirely voluntary. Following this, explicit oral informed consent was obtained from each individual before the commencement of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments during the revision process, which greatly improved the rigor and quality of this study. We would also like to thank the Fujian Provincial Forestry Bureau for its significant assistance during the questionnaire survey phase. Finally, we extend our sincere gratitude to all the villagers who participated in this survey for their valuable time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Xu, C.; Lin, F.; Li, C.; Cheng, B. Effects of designating non-public forests for ecological purposes on farmer’s forestland investment: A quasi-experiment in southern China. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 143, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadera, A.; Tadesse, T.; Zeweld, W.; Tesfay, G.; Gebremedhin, B. Trust, tenure security and investment in high-value forests. For. Policy Econ. 2024, 166, 103268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xue, C.; Yousefpour, R. Forest land property rights and forest ecosystem quality: Evidence from forest land titling reform in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumbiegel, K.; Tillie, P. Sustainable practices in cocoa production. The role of certification schemes and farmer cooperatives. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 222, 108211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Si, R. Research on the impact of land rights certification on farmers’ operating behavior. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xie, H.; Huang, Z.; Gai, Q. Property rights, resource reallocation and welfare effects: Evidence from a land certification programme. Land Use Policy 2025, 154, 107562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, H. Farmers’ adoption of agriculture green production technologies: Perceived value or policy-driven? Heliyon 2024, 10, e23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Does policy cognition affect livestock farmers’ investment in manure recycling facilities? Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Wei, X.; Chen, W. Study on the effect of wildlife damage compensation on farmers’ willingness to sustain cultivation under the dual objective constraint of conservation and development. J. Nat. Conserv. 2025, 86, 126938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatz, C.; Kadam, P.; Pfeuffer, A.; Dwivedi, P. The portrayal of forest certification in national and state newspapers of the United States. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 130, 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, K. Global bamboo forest certification: The state of the art. Adv. Bamboo Sci. 2024, 7, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeta, D.; Ayana, A.N. The contribution of forest coffee certification program to household income and resource conservation: Empirical evidences from Southwest Ethiopia. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 25, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canessa, C.; Ait-Sidhoum, A.; Wunder, S.; Sauer, J. What matters most in determining European farmers’ participation in agri-environmental measures? A systematic review of the quantitative literature. Land Use Policy 2024, 140, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Fan, D.; Chen, J.; Li, S. From policy to participation: Exploring the influence of property rights on rural revitalization efforts. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 86, 1660–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovska Stojcheska, A.; Kotevska, A.; Bogdanov, N.; Nikolić, A. How do farmers respond to rural development policy challenges? Evidence from Macedonia, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Land Use Policy 2016, 59, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiranya, J.; Joshi, H.G. Bridging the psychological and policy gaps: Enhancing farmer access to agricultural credit in India. Acta Psychol. 2025, 255, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridi, M.; Rahimian, M.; Ghanbari Movahed, R.; Molavi, H.; Gholamrezai, S.; Payamani, K. Policy insights for drought adaptation: Farmers’ behavior and sustainable agricultural development. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 26, 100603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Has China’s new round of collective forest reforms caused an increase in the use of productive forest inputs? Land Use Policy 2017, 64, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y. Devolution of tenure rights in forestland in China: Impact on investment and forest growth. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 154, 103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Yang, L. Rural venture investments with credits mortgaged on farmer’s forests—A case study of Zhejiang, China. For. Policy Econ. 2022, 143, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starfinger, M.; Tham, L.T.; Tegegne, Y.T. Tree collateral—A finance blind spot for small-scale forestry? A realist synthesis review. For. Policy Econ. 2023, 147, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, W. Effect of Collective Forest Tenure Reform on Peoples Harvesting Behaviors. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2012, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhola, S.; Gwaindepi, A. Land tenure formalisation and perceived tenure security: Two decades of the land administration project in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2024, 143, 107195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Heerink, N.; Ruben, R.; Qu, F. Land rental market, off-farm employment and agricultural production in Southeast China: A plot-level case study. China Econ. Rev. 2010, 21, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leight, J. Reallocating wealth? Insecure property rights and agricultural investment in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 40, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, C.; Fortmann, L. Community and industrial forest concessions: Are they effective at reducing forest loss and does FSC certification play a role? World Dev. 2023, 170, 106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Sills, E.O. Inviting oversight: Effects of forest certification on deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. World Dev. 2024, 173, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Poudyal, N.C.; Lu, F. Understanding landowners’ interest and willingness to participate in forest certification program in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doremus, J. Unintended impacts from forest certification: Evidence from indigenous Aka households in Congo. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 166, 106378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Goff, L.; Rivera Planter, M. Does eco-certification stem tropical deforestation? Forest Stewardship Council certification in Mexico. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 89, 306–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, N.; Rubino, E.C.; Gan, J.; Gutierrez-Castillo, A.; Pelkki, M. Private landowners’ willingness-to-pay for certifying forestland and influencing factors: Evidence from Arkansas, United States. Environ. Chall. 2022, 9, 100600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adere, T.H.; Mertens, K.; Maertens, M.; Vranken, L. The impact of land certification and risk preferences on investment in soil and water conservation: Evidence from southern Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulmin, C. Securing land and property rights in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of local institutions. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H. Mental Accounting Matters. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 1999, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, J.G. Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica 1971, 39, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).