Hospital-Oriented Development (HOD): A Quantitative Morphological Analysis for Collaborative Development of Healthcare and Daily Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Related Concepts of HOD: Inspirations and Advancements of Accessibility, Community Life Circle, and TOD Paradigm

2.2. Multi-Scale Research and Factor Analysis on Hospital Planning and Design

2.3. Quantitative Measurements for Evaluation of Collaborative Development

2.4. Current Gaps and Our Study

- First, despite extensive explorations into the macro- and micro-scale dimensions of hospital-related research, few studies explore the meso-scale, i.e., the collaborative development of hospital-surrounding areas.

- Second, existing evaluations rely on limited indicators, either the performance of the hospital itself or isolated factors, lacking a comprehensive indicator system and systematic quantitative measurements.

- Third, most designs are case-specific and experience-led with poor generalizability; a spatial prototype and evidence-based benchmarks that can directly and precisely guide the urban design practice of hospital areas are urgently needed.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area and Data Sources

3.2. Research Framework

3.3. Methods

4. Results

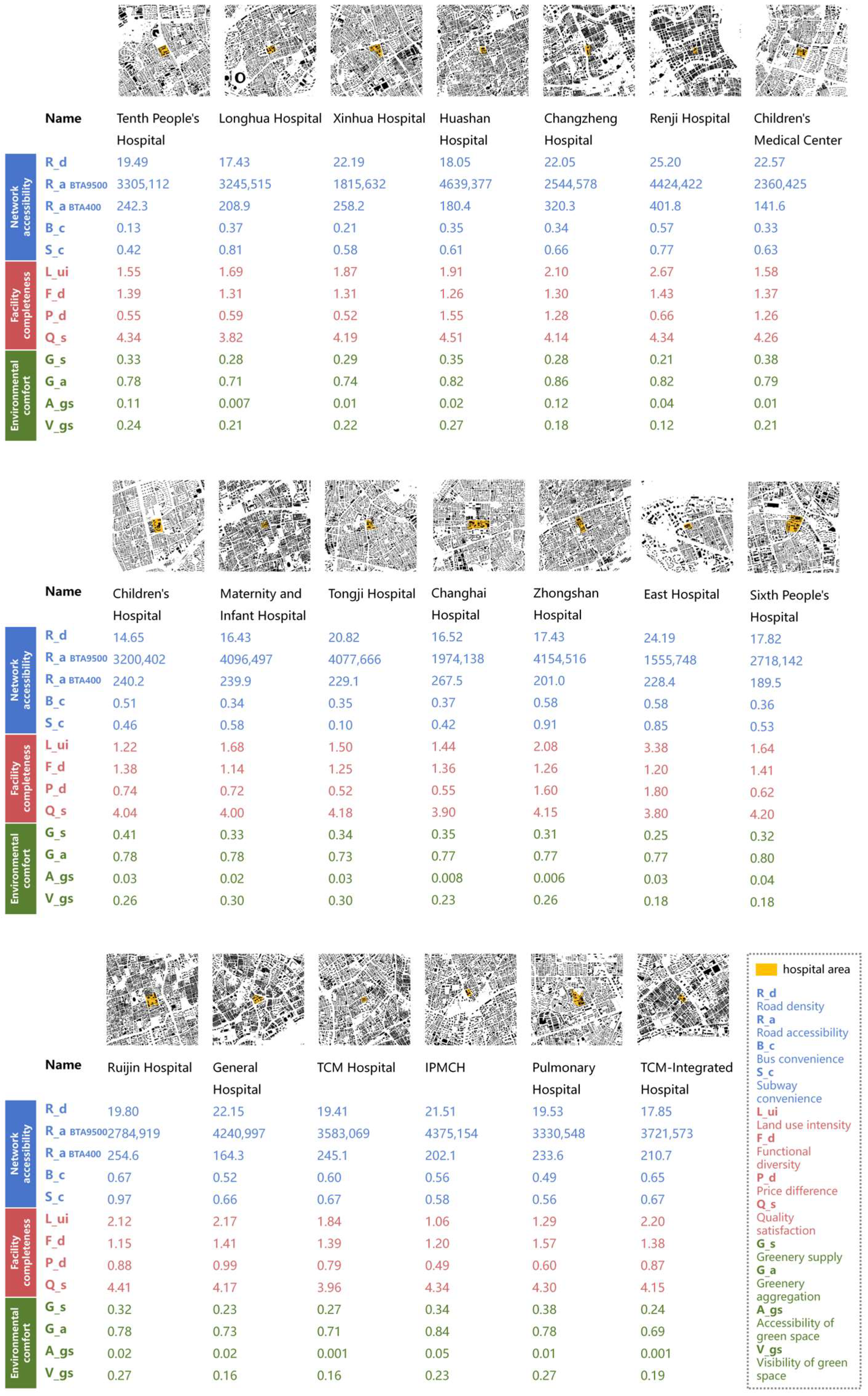

4.1. Calculation Results of Indicators

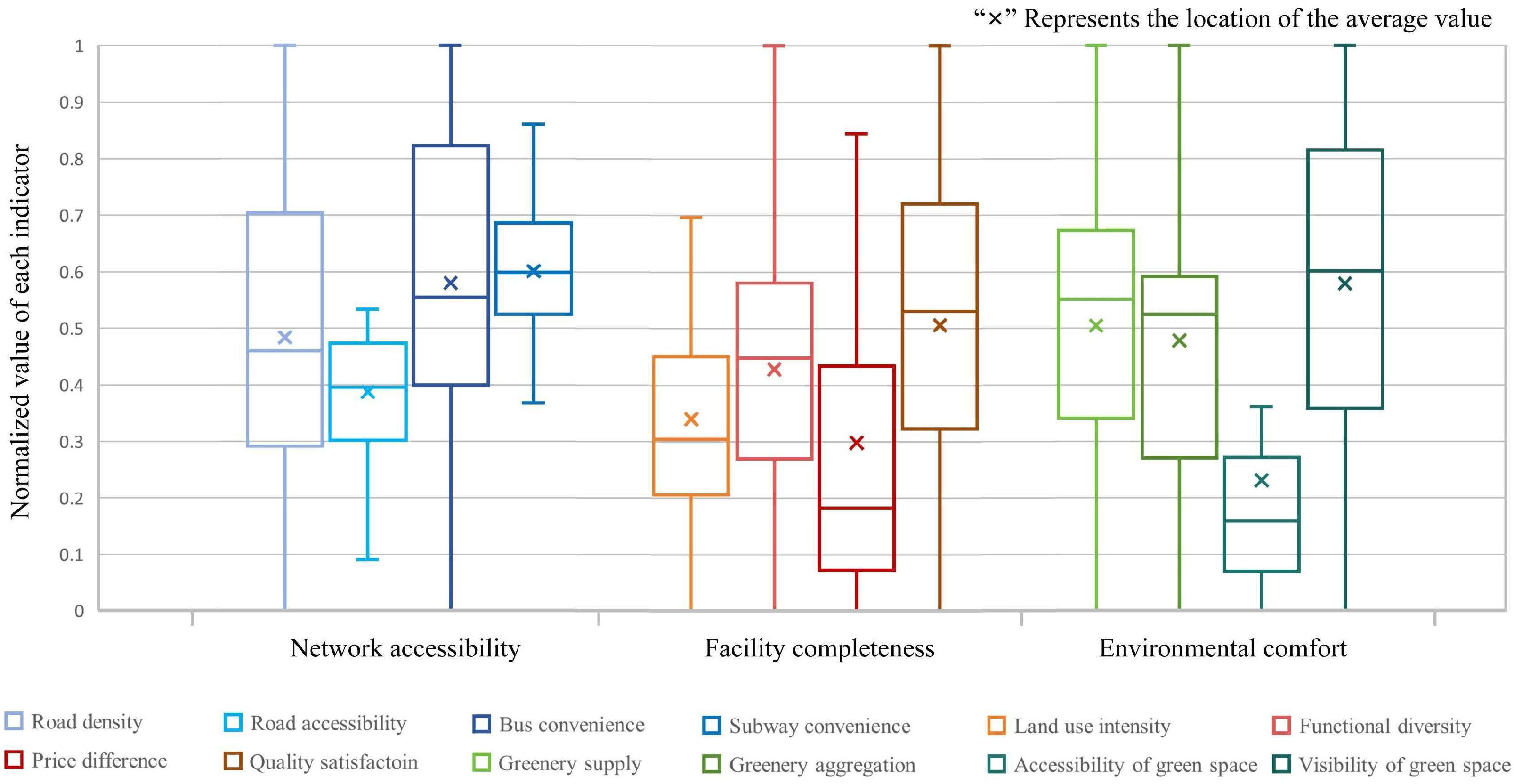

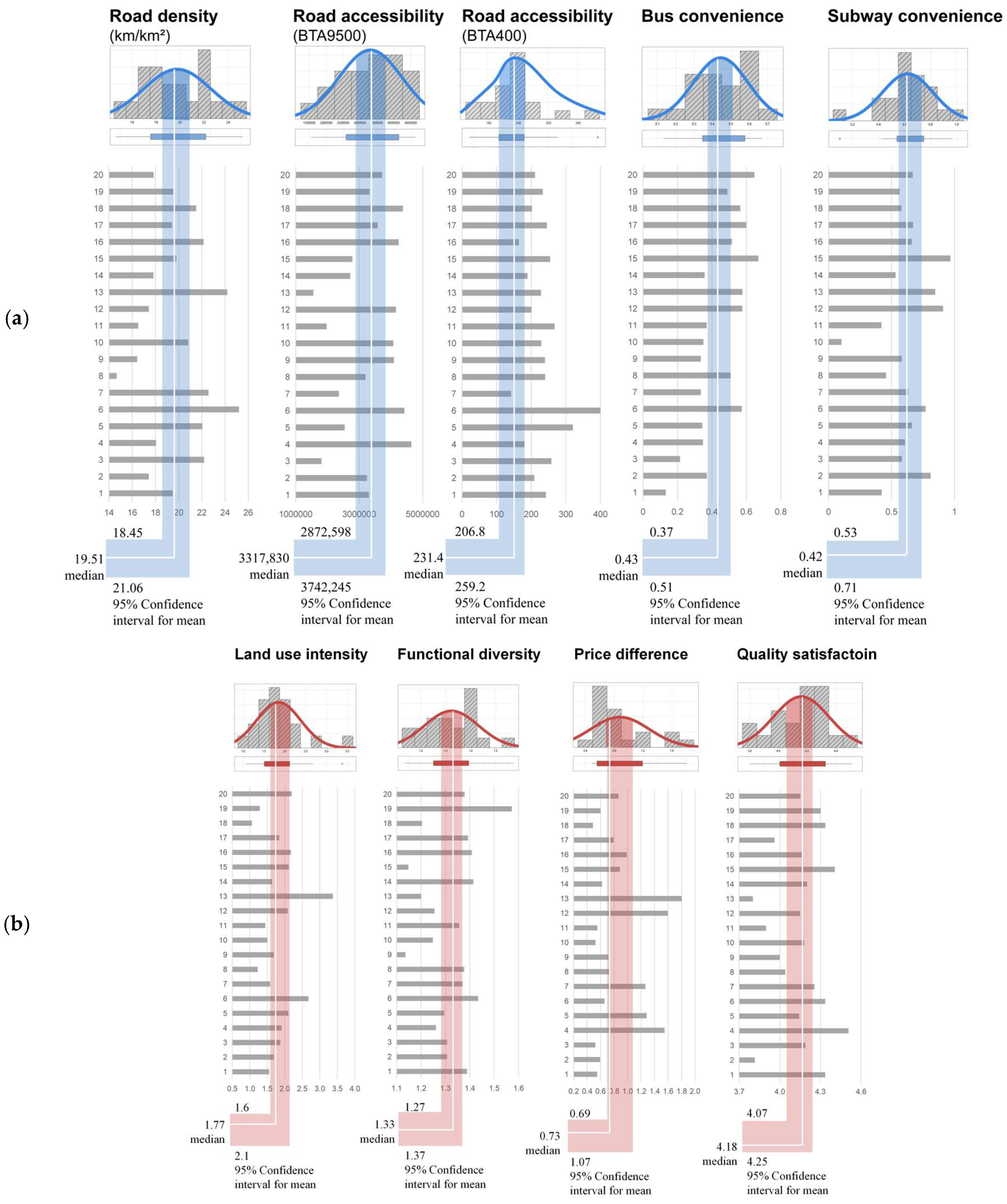

4.2. Confidence Interval Analysis of Indicators

4.2.1. Network Accessibility

4.2.2. Facility Completeness

4.2.3. Environmental Comfort

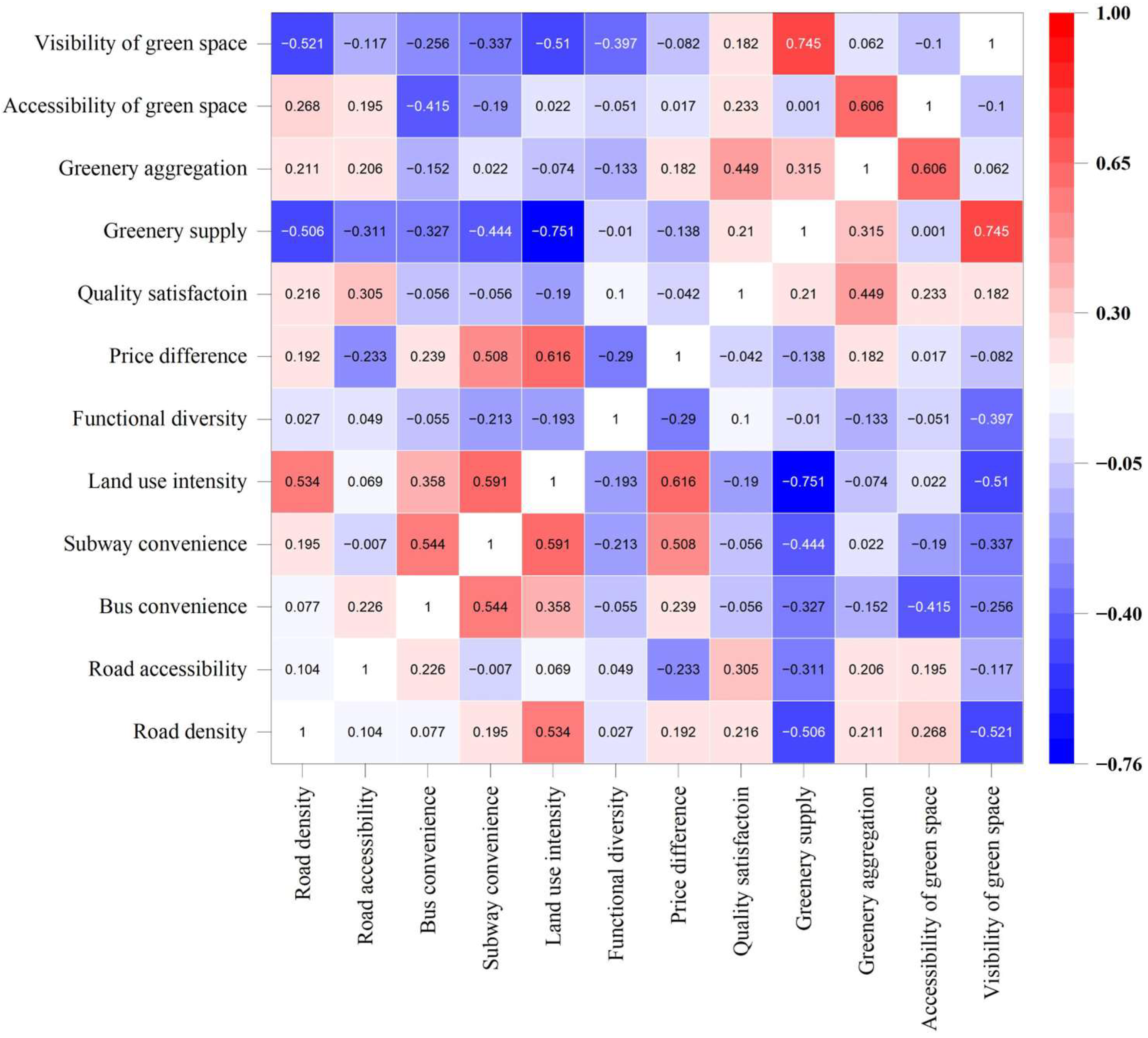

4.3. Synergistic Effect on HOD Performance of Indicators

5. Discussion

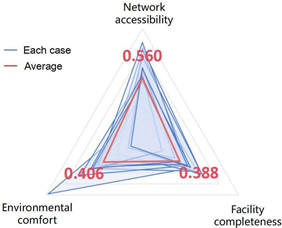

5.1. Composite Scores of HOD Performance

5.2. Prototype Construction and Empirical Illustration

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contribution: Conceptual Framework Establishment

6.2. Empirical Contribution: Quantitative Evaluation

6.3. Practical Contribution: Prototype Construction

6.4. Limitations and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HOD | Hospital-Oriented Development |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| UGC | User-generated Content |

References

- Hong, C.; Sun, L.; Liu, G.; Guan, B.; Li, C.; Luo, Y. Response of Global Health Towards the Challenges Presented by Population Aging. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 884–887. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Botta, F. The Geography of Inequalities in Access to Healthcare across England: The Role of Bus Travel Time Variability. J. Phys. Complex. 2025, 6, 025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; van Eck, J.R. Accessibility Measures: Review and Applications. Evaluation of Accessibility Impacts of Land-Use Transportation Scenarios, and Related Social and Economic Impact; Universiteit Utrecht-URU: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Sun, D. 15-Min Pedestrian Distance Life Circle and Sustainable Community Governance in Chinese Metropolitan Cities: A Diagnosis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wu, C.; Chung, H. The 15-Minute Community Life Circle for Older People: Walkability Measurement Based on Service Accessibility and Street-Level Built Environment—A Case Study of Suzhou, China. Cities 2025, 157, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Li, J.; Shen, L.; Wu, Y.; Bao, H. Contributions to a Theoretical Framework for Evaluating the Supply–Demand Matching of Medical Care Facilities in Mega-Cities: Incorporating Location, Scale, and Quality Factors. Land 2024, 13, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zeng, H.; Wu, L.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, N.; He, R.; Xue, H.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J.; Liang, F.; et al. Spatial Accessibility Evaluation and Location Optimization of Primary Healthcare in China: A Case Study of Shenzhen. GeoHealth 2023, 7, e2022GH000753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calthorpe, P. The Sustainable Urban Development Reader; Beatley, T., Wheeler, S.M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-136-99848-5. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, C.; Renne, J.L.; Bertolini, L. Transit Oriented Development: Making It Happen (Transport and Mobility); Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-7546-7315-6. [Google Scholar]

- Khodadadi, S.; Tasooji, T.K.; Shariat-Mohayman, A.; Kalantari, N. A Multi-Objective Simultaneous Routing, Facility Location and Allocation Model for Earthquake Emergency Logistics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.22487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Zhang, G.; Lin, T.; Hamm, N.A.S.; Li, C.; Wu, X.; Hu, K. Quantitative Evaluation of Spatial Accessibility of Various Urban Medical Services Based on Big Data of Outpatient Appointments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Mu, L.; Kang, C.; Liu, Y. Evaluating Healthcare Resource Inequality in Beijing, China Based on an Improved Spatial Accessibility Measurement. Trans. GIS 2021, 25, 1504–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y. Urban and Rural Disparities in General Hospital Accessibility within a Chinese Metropolis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wijngaarden, J.D.H.; Braam, A.; Buljac-Samardžić, M.; Hilders, C.G.J.M. Towards Process-Oriented Hospital Structures; Drivers behind the Development of Hospital Designs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayal, I.S.; Farid, A.M. Designing Patient-Oriented Healthcare Services as a System of Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 13th Annual Conference on System of Systems Engineering (SoSE), Paris, France, 19–22 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Study on Sustainable Development Oriented Community Public Hospital in China Based on Optimal Decision Making Model for Environment Renovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petros, A.K.; Georgi, J.N. Landscape Preference Evaluation for Hospital Environmental Design. J. Environ. Prot. 2011, 2, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, S.; Varni, J.W.; Seid, M.; Cooper-Marcus, C.; Ensberg, M.J.; Jacobs, J.R.; Mehlenbeck, R.S. Evaluating a children’s hospital garden environment: Utilization and consumer satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Self-Organization of Peripheral Service Facilities of Top-Three Hospitals in Big Cities: Taking Xinjiekou District of Beijing Jishuitan Hospital as an Example. Huazhong Archit. 2022, 8, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Zeng, W.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y. The Visual Quality of Streets: A Human-Centred Continuous Measurement Based on Machine Learning Algorithms and Street View Images. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1439–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, S.; Tong, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, P.; Long, Y. Associations between the Quality of Street Space and the Attributes of the Built Environment Using Large Volumes of Street View Pictures. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2022, 49, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Qiu, H. Environmental and Social Benefits, and Their Coupling Coordination in Urban Wetland Parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Ren, F.; Yuen, K.F.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, D. The Spatial Coupling Effect between Urban Public Transport and Commercial Complexes: A Network Centrality Perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xuan, Z. Quantifying the Impact of Sports Stadiums on Urban Morphology: The Case of Jiangwan Stadium, Shanghai. Buildings 2025, 15, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Urban Regeneration: Economic and Social Impacts of a Multifunctional Sports Park in Reggio Calabria. Buildings 2025, 15, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kim, Y.N. Exploring the Symbiotic Growth of Urban Sports Facilities and Ecology within the Framework of “Internet+” Strategy. Int. J. e-Collab. 2024, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Municipal Health Commission. List of Tertiary Medical Institutions in Shanghai. Available online: https://wsjkw.sh.gov.cn/fwjg/20180601/0012-55891.html (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- GB 51039-2014; General Hospital Architectural Design Standards. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Guiding Principles for the Planning of Medical Institutions (2021–2025). Available online: http://big5.www.gov.cn/gate/big5/www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2022-02/01/5671603/files/ebc7f734128e4a3c8f4311ce803d3441.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Shanghai Planning and Land Resources Administration. Shanghai Planning Guidance of 15-Minute Community-Life Circle; Shanghai Planning and Land Resources Administration: Shanghai, China, 2016.

- TD/T 1062-2021; Spatial Planning Guidance to Community Life Unit. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China, 2021. Available online: http://www.nrsis.org.cn/mnr_kfs/file/read/21d2d1d71032b84e847e2baeb6aaf39c (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Ibrahim, S.M.; Ayad, H.M.; Turki, E.A.; Saadallah, D.M. Measuring Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Levels: Prioritize Potential Areas for TOD in Alexandria, Egypt Using GIS-Spatial Multi-Criteria Based Model. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 67, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Richards, D.; Lu, Y.; Song, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Zhong, T. Measuring Daily Accessed Street Greenery: A Human-Scale Approach for Informing Better Urban Planning Practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, R.; Grigolon, A.; Brussel, M. Evaluating TOD in the Context of Local Area Planning Using Mixed-Methods. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.S.; Han, Y.; Ye, Y. Coastal Waterfront Vibrancy: An Exploration from the Perspective of Quantitative Urban Morphology. Buildings 2022, 12, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ning, J.; You, H.; Xu, L. Urban Intensity in Theory and Practice: Empirical Determining Mechanism of Floor Area Ratio and Its Deviation from the Classic Location Theories in Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijkelenboom, A.; Bluyssen, P.M. Comfort and Health of Patients and Staff, Related to the Physical Environment of Different Departments in Hospitals: A Literature Review. Intell. Build. Int. 2022, 14, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Van Dijk, T.; Tang, J.; Berg, A. Green Space Attachment and Health: A Comparative Study in Two Urban Neighborhoods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14342–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimension | Indicator | Definition | Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network accessibility | Road density (km/km2) | The total length of the roads divided by the area | Rd: Road density; : Total road length in this district; : Land area |

| Road accessibility | The number of times each street segment x is traversed by the “shortest” path between any two other street segments y and z within a particular analysis radius | This study utilized BTA9500 and BTA400, which fitted both nearby residents and patients from afar. | |

| Bus convenience | Comprehensive evaluation of attenuation coefficient of distance, station coverage, station distribution density, and number of bus stations based on AHP * | WD = attenuation coefficient of distance STC = station coverage STD = station distribution density STN = station amount | |

| Subway convenience | Comprehensive evaluation of attenuation coefficient of distance, station coverage, station distribution density, and number of subway stations based on AHP | ||

| Facility completeness | Land use intensity | The intensity of land development in the region, expressed as plot ratio | PRi: Plot ratio; : The total area of buildings; : Land area |

| Functional diversity | The diversity of subcategories of service facilities in the region, representing the degree of user choice when using a type of facility | H: The POI diversity index; : The total number of POI; :The relative abundance of the POI | |

| Price difference | The degree of dispersion in the unit price of a certain type of service facility in the region | Cv: Coefficient of variation; : Standard deviation of probability distribution; : Mean of probability distribution | |

| Quality satisfaction | The average score of a certain type of service facility in the region evaluated by consumers | : Average score of type A, : A certain score evaluated by consumer (5 points for total score) | |

| Environmental comfort | Greenery supply | The number of available green spaces within a region, which is quantified by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | NIR: Near-infrared band reflectance, : Red light band reflectance (this study took the mean NDVI for the region) |

| Greenery aggregation | The connectivity or dispersion trend of green spaces within a region, generally quantified using the Aggregation Index | gn: The number of similar adjacent patches of corresponding landscape types | |

| Accessibility of green space | The distance from large green spaces or the proportion of large-scale green spaces in the surrounding area | Sg: The total area of various public green spaces in the surrounding area; : Total area of the region | |

| Visibility of green space | The proportion of green plants in the street view, using green visual index (GVI) as the main measurement indicator, which can be automatically identified by semantic segmentation methods | Pg: The number of green pixels in the image; : Total number of pixels in the image |

| Main Dimensions | Weight | Indicators | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network accessibility | 0.2605 | Road density | 0.0148 |

| Road accessibility | 0.0386 | ||

| Bus convenience | 0.0386 | ||

| Subway convenience | 0.1685 | ||

| Facility completeness | 0.6334 | Land use intensity | 0.2702 |

| Functional diversity | 0.1106 | ||

| Price difference | 0.1043 | ||

| Quality satisfaction | 0.1483 | ||

| Environmental comfort | 0.1061 | Greenery supply | 0.0427 |

| Greenery aggregation | 0.0043 | ||

| Accessibility of green space | 0.0426 | ||

| Visibility of green space | 0.0166 |

| Name | Average Level Among Three Dimensions | HOD Performance | Normalized Score (100 Mark System) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tenth People’s Hospital |  | 0.4011 | 38.95 |

| Longhua Hospital | 0.3252 | 17.90 | |

| Xinhua Hospital | 0.3719 | 30.85 | |

| Huashan Hospital | 0.5551 | 81.63 | |

| Changzheng Hospital | 0.5183 | 71.44 | |

| Renji Hospital | 0.6214 | 100.00 | |

| Children’s Medical Center | 0.4582 | 54.77 | |

| Children’s Hospital | 0.3291 | 19.00 | |

| Maternity and Infant Hospital | 0.3132 | 14.57 | |

| Tongji Hospital | 0.2606 | 0.00 | |

| Changhai Hospital | 0.2631 | 0.68 | |

| Zhongshan Hospital | 0.5584 | 82.52 | |

| East Hospital | 0.6123 | 97.46 | |

| Sixth People’s Hospital | 0.3867 | 34.95 | |

| Ruijin Hospital | 0.5605 | 83.12 | |

| General Hospital | 0.4923 | 64.21 | |

| TCM Hospital | 0.3991 | 38.37 | |

| IPMCH | 0.3391 | 21.76 | |

| Pulmonary Hospital | 0.4432 | 50.62 | |

| TCM-Integrated Hospital | 0.4774 | 60.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lei, J.; Tan, H.; Wang, X.; Ye, Y. Hospital-Oriented Development (HOD): A Quantitative Morphological Analysis for Collaborative Development of Healthcare and Daily Life. Land 2025, 14, 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101996

Chen Z, Wang Y, Zhang H, Lei J, Tan H, Wang X, Ye Y. Hospital-Oriented Development (HOD): A Quantitative Morphological Analysis for Collaborative Development of Healthcare and Daily Life. Land. 2025; 14(10):1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101996

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ziyi, Yizhuo Wang, Hua Zhang, Jingmeng Lei, Haochun Tan, Xuan Wang, and Yu Ye. 2025. "Hospital-Oriented Development (HOD): A Quantitative Morphological Analysis for Collaborative Development of Healthcare and Daily Life" Land 14, no. 10: 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101996

APA StyleChen, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Lei, J., Tan, H., Wang, X., & Ye, Y. (2025). Hospital-Oriented Development (HOD): A Quantitative Morphological Analysis for Collaborative Development of Healthcare and Daily Life. Land, 14(10), 1996. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14101996