1. Introduction

Cities and regions today face increasing challenges, including social fragmentation, environmental pressures, and growing complexity in governance and development. Traditional top-down planning models often struggle to respond effectively to these demands [

1], while bottom-up approaches, although more inclusive, face difficulties with scalability and integration across diverse planning contexts [

2]. When planning urban places generally, inspiration is often drawn from other urban areas and influenced by prevailing trends. This is part of the competitive effort to create the most attractive places possible for new residents, visitors, and businesses. A sense of anxiety about competition and remaining ahead in the race for image creation and marketing processes can frequently arise [

3]. Digital media and digital marketing often play a significant role. Visibility can sometimes become more important than focusing on substance, quality, sustainability, and democratic processes. This tension highlights a notable gap in current planning practice as well as research. Geomedia studies, which combine media and communication studies with human geography, emphasise this perspective [

4], demonstrating how digital media influence our daily lives [

5]. Geomedia studies offer a reflective approach to how places are experienced, portrayed, and negotiated, contributing to a broader understanding of place, place identity, and people’s perception of place. Geomedia also contributes with a reflective perspective of the power relations between place, people, and technology [

6].

This article is based on the rising influence of digital media in shaping perceptions of place, which often prioritise visibility and branding over substance, sustainability, and democratic participation. It also considers the dominance of urban norms that influence planning ideals and marginalise alternative lifestyles and spatial experiences. Additionally, Thomas [

7] argues that effective planning requires decisions to be made through participation, emphasising the involvement of end-users alongside planning specialists within an urban design framework. Consequently, planning is a complex challenge. Given this complexity, this article problematises and integrates place into urban design [

8] as a transformative approach to address such intricacies [

5,

9]. By incorporating place design and digital dimensions through Geomedia studies [

4], it explores how digital aspects can be embedded into participatory planning.

Place design as a concept acts as a bridge between the physical, digital, and social realms, linking the past with heritage and history, and the future. It also helps connect expert knowledge with civic participation [

10,

11]. Place design involves a targeted approach that emphasises understanding the local community by collaborating with resources and actors familiar with the place. Employing a place design approach in a design process can foster creative placemaking, influencing social systems. Cilliers and Timmermans [

12] and Semeraro et al. [

13] argue that it can assist in solving problems innovatively and, in line with placemaking, generate measurable value through iterative and exploratory processes.

This article aims to examine the transition from planning for people to designing with people, emphasising its narratives and representations within a Geomedia-based and participatory urban planning approach. It poses the following questions:

- -

How can planning processes mirror the complexity of place?

- -

In what ways can digital representation be meaningfully incorporated into participatory planning?

- -

Who is included or excluded in the creation and representations of places?

Drawing on theory, case studies presented from the municipalities of Kristinehamn, Sunne, and the community of Sysslebäck in Värmland, Sweden, demonstrate various ways of capturing representations of place to foster inclusivity and democracy in urban planning (see

Figure 1 for an overview of the theoretical foundation, research design, methodology, and pathways to outcomes). Ultimately, the article advocates for a planning approach that begins with preparatory, participatory processes, enabling a deeper understanding of representations of place and establishing the groundwork for more democratic, inclusive, and context-aware development.

This paper is organised as follows. It starts with a theoretical framework of design and place design, drawing on Geomedia theory and discussions on representations of place. Next, the design is introduced as a methodological and participatory approach, along with the various methods used to develop an understanding of a place. The following section presents results from case studies in Värmland, Sweden. These results highlight similarities and differences in representations, exclusions, inclusions, and invisible boundaries, among other aspects. The article concludes with a discussion and final remarks.

3. Materials and Methods

Place design has inspired a participatory and methodological approach to managing the complexity inherent in planning [

7,

51]. To contextualise place design, we highlighted various elements central to the process, such as socio-cultural aspects of place, geomedia, and representation [

7]. These elements have been fundamental to understanding place and have laid the foundation for further collaborative and participatory processes.

The research builds on action-based projects conducted over several years. Here, a few selected cases are highlighted to illustrate examples from the studies. These cases, the municipalities of Kristinehamn and Sunne, as well as the smaller community of Sysslebäck, are located in Värmland, Sweden (Studies in Sunne and Kristinehamn were conducted between 2018 and 2021. Studies in Sysslebäck took place between 2021 and 2024.).

Kristinehamn is a municipality in the southeastern part of Värmland, situated on the shores of Lake Vänern. Kristinehamn leverages Lake Vänern as a resource for tourism and has a tradition of boat and boat engine manufacturing. In the old days, there was an important port on Lake Vänern for shipping iron and steel to destinations worldwide.

Sunne is a municipality situated in the heart of Värmland, on the shores of Lake Fryken. It is celebrated for its culture and storytelling traditions. Additionally, Sunne is notable as the birthplace of Nobel laureate Selma Lagerlöf in 1909. The area is also a popular tourist destination, especially during the summer, with numerous attractions.

Sysslebäck, the smallest settlement, lies in a peripheral municipality, Torsby, near the Norwegian border, influenced by both Swedish and Norwegian cultures. The municipality is recognised for its entrepreneurial spirit among small and medium-sized enterprises. However, it faces a significant challenge due to seasonal population changes driven by tourism, including nature-based and winter sports tourism. These cases do not represent large urban areas, but they can help to illustrate how place design can be applied in urban planning, for both large and small cities.

3.1. Place Design as a Research Methodology

Stakeholders such as residents, planners, and others have been involved to identify issues, set goals, and develop solutions. An initial step was to carry out an “in-depth interview” with the different cases, which fostered an understanding of other perspectives [

26,

37]. A crucial starting point was to identify the unique characteristics and spirit of each place, to uncover new and exciting aspects to include in the planning process. This included existing power structures that span the past, present, and future, as well as socio-cultural or historical perspectives [

6].

Participatory action research (PAR) and the design process guided us in facilitating a cycle-based approach, where each cycle involved investigation, action, and reflection. This involved transferring knowledge from inclusive actors from one cycle to the next [

26]. The aim was for the knowledge and perspectives generated within each cycle to inform subsequent cycles (cf. the design literature on the double diamond model [

52]). PAR served as the foundation for collaboration, reflection, and action through close dialogue with selected actors [

51]. First, key partners were identified. In cooperation with official stakeholders and our key partners from each case, we asked who uses the place, has an interest in it, or will be affected by its planning [

18]. Which stakeholders possess expert knowledge about the place, such as planners, local authorities, developers, or other impacted actors? The goal was to involve all parties in the process to ensure diverse representations (cf. [

36]). For each case, we then selected several actors involved in different parts of the detailed studies. Practically, we conducted ‘in-depth studies’ of various places.

3.2. In-Depth Studies of Place

Several methods were employed to capture the complexity of the place and the perspectives of the actors. We started with field observations, conducted document studies, and carried out interviews with various stakeholders (see

Table 1). Additionally, we performed qualitative digital text and image analyses, as well as a survey study.

Field observations and document studies were carried out to gain an understanding and appreciation of the place, its resources, history and cultural heritage. Through interviews with residents and stakeholders, we explored their experiences of the place and their ideas and perceptions about it. Interviews offered insights into how different people connect with the place, its history, identity, and future. Many stories and memories shared by those linked to the location were documented. Here, we captured representations of the place, as well as expressed needs and challenges for planning and development. By involving citizens, we revealed how people relate to their environment, the practices of different groups, and the daily routines that shape and sustain their everyday lives [

53]. Through the stories told by informants, it becomes possible to gather diverse images of experiences, which are reflected in the reality they live in. We also included questions on how they connect with different images and symbols or with local history or buildings considered part of the shared cultural heritage.

We examined perspectives from producers, such as a municipality’s policy documents and marketing materials for areas. We also included the work of authorities, like the county administrative board’s efforts in cultural heritage preservation and decisions regarding environments and sites that should be conserved.

Geomedia-based tools and platforms were used to visualise the different layers of the place, i.e., the digital representation. Other forms of user-generated content, such as videos, comments, discussions, and rankings on various platforms, provide valuable feedback on how visitors and prospective visitors gather information about the place.

The survey conducted with visitors provided an external perspective on functions, such as their expectations, preferences, and experiences of the place. The survey highlighted opportunities to enhance what the place offers, improve information access, and identify what attracts visitors.

Through these various methods, we deeply engaged with the physical location, its local history, and cultural heritage. We focused on capturing different representations, both historically and currently, as well as digitally. This led to comprehensive studies of each place, aiming to gain a deeper understanding of local history, culture, landscape, and natural resources, adopting a relational perspective on the place [

36,

39]. Questions were asked about the material on how a place is represented historically and in the present. What aspects are included or excluded? By highlighting different voices and connecting history to the present, we aimed to create a more equitable and inclusive image of the place [

39]. By viewing the place from a reflective standpoint, we uncovered new facets and aspects of the story, as well as identified paths and themes that guided the design of the place.

Analyses were subsequently carried out in multiple stages. Thematic analysis of document studies and interviews identified key themes relating to the significance, identity, and potential of the site. A critical discourse analysis was undertaken on digital representations and planning documents to uncover power dynamics, inclusion and exclusion, and alternative visions of the future. We compared images, texts, and other materials demonstrating how the site is currently depicted, contrasting these with historical sources. Additionally, we evaluated the representation of the place against its digital portrayal.

Regarding the material collected, we have asked ourselves several questions about it, including questions such as: Who and what are represented in the story, and what image of the place emerges? What has been included in the narrative about the place, and which parts of the narrative have been left in the shadows? Are there interesting connections between the history of the place and what exists there today, including its appearance and cultural heritage? Which actors are included, and which are excluded, in the planning of the place and its representation? Are local needs and challenges considered in planning processes? Can locals and visitors gain a better understanding of the place and its planning by experiencing parts of its history? Using these critical questions [

26], we highlight perspectives on whose stories or cultural heritage are visible, as well as marginalised viewpoints on time and space, gender, age, nature, and culture, along with invisible boundaries and political issues.

A prerequisite for undertaking this type of in-depth study is to conduct thorough groundwork and gather various representations. Combining these methods allows for a deeper understanding of how place design can serve as a platform for local participation, managing aspects of cultural heritage, identities, representations, and so forth. This material then formed the basis for a creative co-creation process conducted through a series of workshops, to which stakeholders were invited (for a detailed description of a collaborative workshop series, see [

26]).

These workshops focused on co-creation based on the resources, needs, and visions of the area, using both physical and digital technologies such as GIS, digital storytelling, and mapping. Public actors, the experts responsible for urban planning, participated in the workshop series [

18], where they discussed why these places are vital. Alongside entrepreneurs, representatives from associations, and cultural heritage organisations, we explored what relates to resources and supplies. A workshop was also held with end users, including residents and visitors, who talked about how to approach planning and development based on identified needs, challenges, and insights from previous workshops. In the final stage, we developed and tested concepts to create concrete proposals for future planning and development. In this way, co-creation was promoted, tailored to the specific conditions of the area.

4. Results

The results of the studies showed that place design as an approach acted as a catalyst for local voices and different representations. By capturing different perspectives of a place using various methods that promote both inclusion and co-creation, three main themes emerged: the voice of the place, digital representation and contrast, and collective ownership and visions for the future. The three different cases are used to illustrate these various results.

4.1. Contrasts Between Representations

Through place interviews, a strong desire arose among participants to share their challenges, needs, experiences, memories, and visions related to the place. Many described how previous planning processes had ignored their perspectives, leading to feelings of exclusion. By “interviewing the place”, the participants felt listened to, which enhanced their sense of belonging and legitimacy in the planning process, leading to the voice of place.

In the case of Kristinehamn, there were examples of different representations, invisible boundaries, and a lack of connection to gender and culture. A representation of Kristinehamn, with its harbour and gateway to the large Lake Vänern and its manufacturing boat industry, emerged, along with a cultural-historical link to the history of ironworks. This was a result of both document studies and interviews.

The history of men, the history of industry, and the maritime cultural heritage were predominant, as well as the men involved in the industry (see

Figure 2 for an example of a mapping of representation).

There was a clear pattern of underrepresentation of women, children, and the working class. We had to search in documents and archives to find cultural heritage that actively included women. The results of the thematic analysis showed that stories about social life and these places as communities were overlooked, as the narrative mainly focuses on economic and industrial history. The study of the different representations provided insights into the relationship with time, where some places lacked a connection between the present and history. In contrast, other places struggled to link historical resources to the present. The survey made with visitors and digital text and images analysis resulted in representation by visitors at Kristinehamn waterfront, i.e., a digital representation, showing activities and water, but a lack of cultural values (see

Figure 3). They felt disconnected and excluded from local information and history and marginalised by the locals.

Sunne is officially described as ‘part of the fairy tale’, reflecting its long tradition of renowned writers who have lived in the area. In the town of Sunne, known for its cultural heritage, much of the digital portrayal focused on some of the town’s most notable attractions, which often allude to the famous author and Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf. Online, a few destinations representing so-called “high culture” were showcased. The portrayal of the place emphasises its social and cultural capital, with a strong focus on storytelling. This gave rise to a sense of personification that symbolises the place and forms part of its identity (see

Figure 4). The interview results with stakeholders indicated a desire to strengthen this sense further.

In contrast, much of the user-generated content, from text and image analysis, confirmed by the survey study, tended to concentrate on various leisure activities and hobbies (water parks, sports, youth culture, and gardening) that visitors and locals partake in. Visitors saw Sunne as a museum where places are meant to be visited rather than experienced, thus excluding it from the ‘fairy tale’. The analysis of data collected using various methods revealed a strong focus on history over the present, culture over nature, and women over men, accompanied by a lack of leisure activities. The results showed that boundaries had been created between place marketing and how both visitors and locals viewed the place. As a result, there was a marked difference between the image conveyed by public actors and that expressed by visitors and locals.

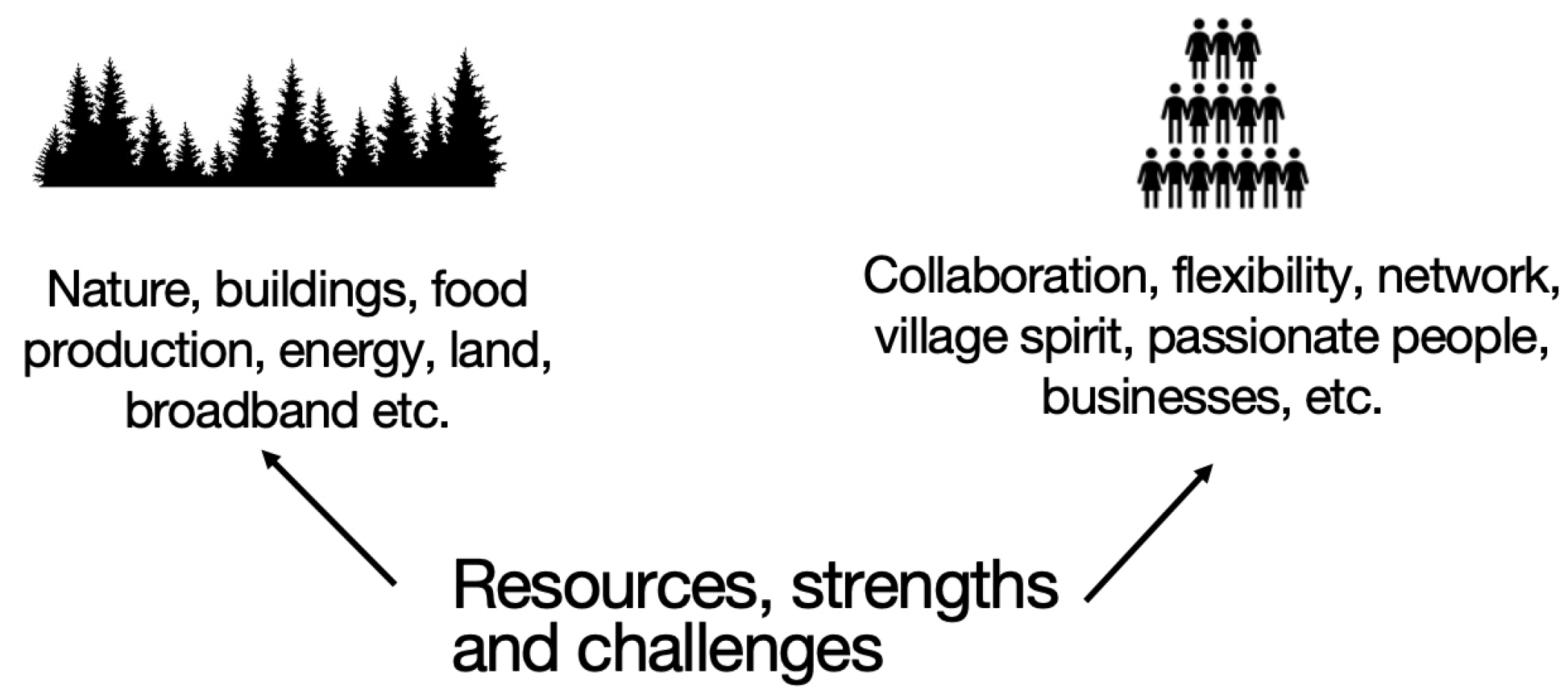

The results of the study in Sysslebäck demonstrate how in-depth interviews can identify both tangible and intangible resources (see

Figure 5). The interviews uncovered specific needs and challenges, as well as strengths and resources to be leveraged. Concrete resources such as empty premises or the surrounding nature were recognised as potential assets for future development. Participatory observations supported this. The identity of the place, the willingness to collaborate, the enthusiasm, and the networks were emphasised as strengths and opportunities for development and future planning.

A key finding from our analysis of the place’s representation was that social aspects were emphasised. Emerging themes included ways of being and living, the interaction between town and countryside, what towns can learn from rural areas and vice versa, as well as transferring knowledge about production, cohesion, and closeness to nature. It also involved loosening existing urban norms and fostering a more positive attitude towards smaller towns. The spirit, collaboration, enthusiasm, and entrepreneurship within the area were highlighted as aspects that need reinforcement and expansion. The visitor survey results showed a general lack of awareness about what the place truly offers beyond the specific attractions promoted in place marketing, such as a large ski resort or nature experiences in the forest and countryside. There was also limited knowledge about housing or business opportunities available in the area.

These results revealed contrasts between official planning images and the residents’ own experiences, as well as an exclusion for potential future residents and businesses. The results of these studies also showed that highlighting different representations of the actors involved contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the places, their history, heritage and resources, as well as the role of the media in shaping places, especially as a means and an influencing factor in how a place is portrayed and thus perceived. Digital media thus functioned both as a tool for inclusion and as a mirror that highlighted exclusion. An awareness arose of the differences that can exist between media representation and local perspectives. The result was also increased knowledge and awareness among municipal representatives, who reflected on how and what they communicate about a place. A concrete result of this, a side effect of the case study in Kristinehamn was that this understanding led to the development of a new digital solution. The solution focused on digital storytelling, which enabled both residents and visitors to explore local history through gamification and interactive quest codes. This involved travelling to various quest stops in the city and along the waterfront to gain a greater understanding of the nature, culture and history of the place.

4.2. Collective Ownership

In Sysslebäck, our analysis of the different data resulted in three distinct areas that generate categories of opportunities suggested by local stakeholders. Three main types of actions to strengthen the local community emerged: (1) Providing information about existing local attractions and events (tangible). How can we share more details about what already exists? How can we make current activities more visible to residents and visitors? How can we showcase this digitally? This was, for example, a result of the exclusion of information about the location and its potential for visitors, which was revealed by the survey. (2) Storytelling about local culture and collaboration (intangible). How do we tell the story of the place, its history, and cultural heritage? How do we highlight community, collaboration, and a welcoming atmosphere? How can we make this visible digitally? The interviews resulted, for example, in stories about historical conflicts between small communities, people who do not know each other, and ignorance about local resources and strengths. (3) Enhancing existing services and visitor experiences (for residents, businesses, visitors, and part-time visitors). How can we improve the experience of the place? How can we better serve residents and businesses? How do we attract more visitors, new residents, and businesses? Interviews with locals and entrepreneurs, as well as a survey of visitors, clearly showed how different representations of the place were highlighted for various target groups. Visitors rarely gained an understanding of the place. Stakeholders proved to lack a sense of how locals wanted to strengthen their relationship with visitors to create new opportunities.

Despite its small size, the case of Sysslebäck effectively demonstrated how collective ownership and community spirit could be developed by listening and facilitating meetings. By engaging local stakeholders, listening to their needs and challenges, and considering their perspectives and experiences of the place, they gained a deeper understanding and improved knowledge.

By including stakeholders in the process from the outset, concrete ideas were generated during the interviews on how the site could be designed in a way that preserves its identity while meeting new needs. Making insights about different representations visible to the actors was part of a collective learning process, in which they jointly “rediscovered” these patterns of representation. This knowledge was then applied in the next part of the design process, particularly in co-creation processes such as workshops [

26]. Inviting participants into a collaborative co-creation, the idea of forming a local development group was born (

Figure 6). What is now an association has over 100 members, including representatives from companies, organisations, and private individuals, focusing on critical local issues concerning schools, care, and business. From the outset, the association has achieved improved cooperation with the municipality on matters such as waste management and has initiated discussions with the authorities regarding the upgrading of roads. The association has also received financial support from the municipality to create a website. This has also led the municipality to realise that it needs to start working differently and engage in greater dialogue with local groups within the municipality.

The collaborative process and the formation of a local development group had positive side effects. Other key business partners have established new collaborations and networks to jointly improve the area’s appeal to entrepreneurs, residents, and visitors, with initiatives to assume local ownership of planning processes.

The study showed that the combination of knowledge and critical thinking in the process helped participants gain new perspectives, broaden the narratives about each place, and encouraged local authorities to adopt new approaches. Participants created collective ownership and visions for the future, not only by identifying problems and challenges, but also by developing shared ideas and visions for the future of the place. Several participants said they felt more confident after the process. One participant said, for example, ‘Being creative together creates innovation’ (local entrepreneur, 8 March 2019).

5. Discussion

By giving the place a voice and highlighting its intangible values, conditions are created for more inclusive, democratic, and sustainable urban development [

6]. Listening to the voice of the place through the stories, memories, and visions of its residents marks a shift from an expert-driven to a relationship-based planning model. This supports previous research by, for example, Jeličić [

1] and Massey [

39], which shows that local knowledge not only complements but often challenges established planning norms. For example, analysing various representations has become a tool for both inclusion and exclusion. Studying digital representations raises awareness of how they are created, highlighting the relation between place, people and technology [

6], which contributes significantly to planning. Digital representations often focus on visitors and specific activities aimed at them, primarily to promote the location. However, what is omitted can provide valuable insights for planning and development. Analyses of different representations can, as the results of the studies showed, also reveal marginalised perspectives or invisible boundaries, such as the unseen dividing line between areas meant for visitors and areas intended for the local population [

26]. As a result, if a place’s cultural heritage is not clearly or adequately represented, it becomes invisible.

Discovering nuances within the main themes of a place and its digital representation helps identify gaps in how these representations are created, along with additional themes and perspectives that can be incorporated into the design process. It concerns who we design for, what is visible to whom, and which stories and cultural heritages are made visible and to whom. Norms, perceptions, and preconceptions about places continue to influence contemporary narratives. What is considered too sensitive or perhaps not interesting enough may remain unseen if it is not uncovered. This raises questions about who has held the power to decide what a place should represent and, consequently, what was included in the planning processes.

Incorporating this knowledge into planning processes can both enhance the legitimacy and relevance of the decisions made [

27]. It can also allow for highlighting what is often excluded, such as more perspectives from those who live, work, and visit the area. Factors such as gender, age, geographical areas within a city, people from different ethnic backgrounds with various views and understandings, and even the use of a place appeared as key considerations. This is a way of considering different spatial practices [

36] and socio-cultural aspects [

39].

Reflecting on different representations and power relations leads to an understanding of the present and future but also requires linking them to the past. This offers a perspective on the connection between past and present, or vice versa, which is evident in certain places and incorporated into planning and development processes. In line with McQuire [

7] and Braunerhielm [

6], digital layers can uncover power structures and create new opportunities for inclusion. At the same time, this requires awareness of the limitations of technology and its potential exclusionary effects. By analysing the various layers of a place, the inclusion of Geomedia technology enables the addition of more stories and emphasises a place’s cultural heritage [

31]. Digital technologies can, for example, foster inclusion and openness in planning, increase transparency, and invite more voices and stories. With knowledge of history and cultural heritage, an understanding of the present and contemporary urban places is developed, as well as tacit knowledge [

54]. Therefore, adding digital layers in the planning process can help visualise representations and serve as tools to enhance the story of a place, its history, or cultural heritage.

Highlighting different layers and representations of a place, incorporating diverse voices, and establishing a foundation for future co-created processes help participants develop a sense of collective ownership over the place’s future [

14,

37] and strengthen sensemaking processes [

25]. This is crucial for achieving long-term sustainability, both socially and culturally. As pointed out by Palermo & Ponzini [

11], planners need to reflect on both the physical and social contexts critically. Design can facilitate this collaboration and the sharing of knowledge [

1,

9,

23], as well as revitalise the civil and social roles of urban planning and urban design [

24].

Collective and co-creative processes often encounter challenges and limitations. Co-creation demands time, resources, and sincere commitment from all participants. There is also a risk that some voices, especially those of the most marginalised, will remain unheard, even in participant-focused processes. This highlights the importance of thorough preparatory work, where so-called place data is gathered through in-depth studies, from a variety of actors, and, for example, marginalised groups are included [

26]. Therefore, it is essential to continuously reflect on power relations and representation at each stage of the planning process [

6,

39].

The research findings highlight the importance of using methods that identify local stakeholders. Collecting information about a place and its stakeholders early in a planning process is a vital and necessary step to increase influence [

14,

37]. Emphasising a creative and co-creative approach also enhances the chances of securing local ownership of the process and providing valuable input into urban planning. Local ownership is essential for ensuring that place design remains sustainable and enduring, allowing planning ideas to be effectively managed and developed. Social interaction plays a crucial role in creating, understanding, and conveying the culture, collective spirit, and sense of community within a place, which in turn becomes a creative force that attracts entrepreneurs, residents, and visitors.

As stated by Rubin [

17] and Egenhoefer [

3], design is situated and relational, enabling democratic and inclusive urban development by giving voices to the place [

6]. Due to the ongoing design process, the main benefit of participatory design is that needs are recognised, and user perspectives are incorporated throughout the entire process.

To clearly establish the need for place design, a place, its resources, identity, and cultural heritage, created by people within a socio-cultural context, must be considered to foster a sensibility towards place [

6]. Place design can therefore serve as an approach to bridge the gap between conservation and development by building on the unique identity of the place and its cultural heritage [

12]. This can lead to new planning ideas that respect the past while looking towards the future [

50]. Consequently, this necessitates new ways of thinking and working with design in planning. Verganti et al. [

21] reinforce the fact that this requires a shift from a user focus to collaboration between place, people, and technology through tangible encounters and joint creation. Based on Rubin [

17], I thus argue that place design can contribute to a methodological renewal. Research should, therefore, be conducted not about a place but with a place [

2,

5].

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that place design, when implemented through co-creation and participatory methods, can reshape urban planning towards greater inclusion, sustainability and local anchoring. Firstly, this article contributes to a conceptual aspect. By integrating different representations, places are given a voice that reflects historical depth and future potential, considering the digital everyday life we live in today. Place design thus highlights the power relations between place, people, and technology, adopting a Geomedia-based approach. Place design is therefore not just about spatial aesthetics but is a relationship- and value-driven approach that promotes shared visions and cultural continuity.

Secondly, place design contributes to social and cultural influence. It strengthens local ownership. Approaching place design as an approach helps to engage communities in a process that enhances a sense of belonging and responsibility. This inspires place design with a participatory and Geomedia-based approach that promotes cultural continuity by ensuring that urban planning respects local narratives and traditions and is adapted to the identity of the place. The Geomedia perspective also helps to challenge norms. The approach has the potential to challenge conventional planning paradigms and introduce alternative futures.

Thirdly, place design has specific practical implications for urban planning. This approach requires urban planners to adopt new working methods that are responsive to the complexity of the place, its different representations and the lived experiences of its inhabitants. This requires new ways of thinking and working with design, and a clear transition from planning for places to designing with people and places. Finally, research indicates the need for place design that incorporates Geomedia and participatory approaches, enabling planners to develop more democratic, sustainable, and context-sensitive strategies. This shift from planning for places to designing with people and places is therefore essential for democratic and inclusive development but also necessary to address today’s urban challenges.

This article illustrates how place design as an approach can inspire different methods for gathering knowledge and understanding a place before beginning a planning process. It builds on several previous studies that have used similar methods. However, studies related to urban planning have their limitations. For example, data could be improved with a more detailed analysis of the role of the planner and their ability to guide and facilitate a similar design process. Knowledge is crucial for understanding the approach, collecting and managing data, and supporting and facilitating the entire design process. Increased collaboration and innovative working methods are needed within organisations, which place new demands on planners. Therefore, further research is needed on the role of the planner and how the design process can be integrated into the practical work of urban planners. Future research should also explore the relationship between place, representation and participation at a deeper level. Particular attention should be paid to how digital technology can facilitate and improve participation processes.

An important challenge for place design, which aims to promote a collaborative and transformative process, is also to delve deeper into who owns the process. Future research should therefore focus on more inclusive and collective working methods to ensure unique place conditions, cultural identity and empowerment for both people and places. It is important to pay attention to how local ownership is ensured in future research. There is also a need for methods that help us ensure the inclusion of those who will be active in the future and attract young people to understand and appreciate the historical and cultural heritage of places as well as to get involved in planning for the future.