Abstract

The Great Wall, as a globally important large-scale linear cultural heritage asset, is an example of the integration of architecture and landscape, demonstrating the interaction and feedback between heritage and the environment. In the context of advocating the holistic protection of cultural heritage and surroundings, this study utilizes landscape character assessment (LCA) to identify the landscape character of the Great Wall heritage area. Taking the heritage area of the Great Wall in Beijing, China, as an example, principal component analysis (PCA), two-step clustering, and the eCognition software were used to identify and describe the landscape character types, and the interaction mechanism between heritage and the environment was further explored through the reclassification process. A total of 20 landscape character types and 201 landscape character areas were identified in the study area, and a deep coupling relationship between heritage and the environment and cultural landscape spatial patterns were found in the core heritage area. The heritage and environmental character of linear heritage areas should be integrated so as to protect, manage, and plan cultural heritage areas at the landscape level. This study identifies and describes the character of the coupling of heritage and the environment in the Great Wall area for the first time, expands the types and methods of landscape character assessment, and carries out the exploration to combine natural and cultural elements of large-scale linear cultural heritage areas.

1. Introduction

The study of the holistic conservation of heritage and the environment is an important research direction in the field of international heritage conservation [1,2]. Heritage academics have also advocated that the conservation of cultural heritage should be extended to part of a larger landscape [3] in order to protect its unique cultural landscape character and spatial structure. Linear cultural heritage (LCH) refers to a collection of cultural heritage assets in a linear geographic space, characterized by a large spatial span and rich biocultural resources [4]. Unlike monolithic, concentrated architectural heritage, LCH is a complex mosaic of human settlements, cultural heritage, and the surrounding environment, whose evolution over time inevitably involves the interaction of natural and cultural elements and is widely influenced by the surrounding community [5]. The sustainable development of LCH areas is currently faced with many problems such as landscape fragmentation, community construction, tourism development, and heritage conservation [6,7], which has been lacking effective means to solve the problems in terms of conservation and management. Therefore, there is a strong need to explore the possibility of a more flexible and dynamic management of LCH areas from the perspective of integrating heritage and the environment, which would allow for change, development, and renewal, while, at the same time, allowing them to maintain their character.

The Great Wall was added to the World Heritage List in 1987 as a great architectural work, whose outstanding universal value (OUV) is that “it is an example of the integration of architecture and landscape” [8]. The Great Wall is a typical example of large-scale LCH [5], with rich cultural heritage and natural environment character. Military architectural heritage sites such as fortresses, fortified towers, and beacon towers are combined with natural patches such as croplands, woodlands, grasslands, and wetlands and change with topographic relief and elevation. The military heritage of the Great Wall and the surrounding natural environment together form the landscape character of the Great Wall heritage asset. However, research on the Great Wall is still limited to the “traditional” heritage concept of treating it as a building or an archaeological site [9,10,11] and seldom combines the Great Wall with its natural environment, in addition to the fact that the local government pays less attention to the environmental protection of the heritage area, which makes the authenticity and integrity of the historical environment around the Great Wall seriously threatened. Therefore, a systematic study of the coupled relationship between heritage and the environment in the Great Wall heritage area should be carried out to protect the regional heritage network composed of cultural heritage and natural environment as a whole.

The landscape character assessment (LCA) method is currently the mainstream method for assessing the value of regional landscapes, which is currently mostly applied in areas where the natural environment dominates, such as natural heritage areas and nature reserves, and the variables in the identification process are dominated by natural factors, with a few cultural factors also used [12], because the cultural landscape is complex and difficult to quantify and there are rarely spatial data of sufficient detail and quality at the regional scale [13]. Therefore, currently, LCA lacks comprehensive research and practice on large-scale LCH sites such as the Great Wall, especially the use of heritage as an indicator to discuss how heritage and the environment organize different landscape character patterns, which is not conducive to the holistic perception of the heritage value of cultural heritage areas.

In large-scale linear heritage areas, where heritage and the environment are strongly interconnected, there is a need to discuss how to develop a management approach to landscape zoning and a deeper understanding of the relationship between heritage and the environment. Therefore, this study aims to carry out the following: (1) construct a holistic approach to identify and describe the landscape characters of heritage and the environment in linear heritage areas through LCA; (2) as the cultural landscape of the Great Wall involves complex natural and cultural attributes, it is necessary to integrate large amounts of spatial data using machine-based identification and clustering methods; and (3) try to use a combination of case studies and field research, joint experts and communities, to form a working group to identify and describe landscape character types in depth and explore the coupling relationship between heritage and the environment at large-scale linear heritage areas. This study is aimed at constructing a natural–cultural value network of the Great Wall to complement and enhance the multifaceted heritage values and connotations of the Great Wall. The methodology is also applicable to LCH areas with outstanding natural and cultural characters and provides a reference for the protection, management, and planning of heritage areas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Holistic Conservation of Heritage Areas

Cultural heritage conservation has expanded from the conservation of individual cultural heritage buildings to the holistic conservation of heritage values from a regional perspective. The Nairobi Recommendation, adopted by the UNESCO in November 1976, states that “each historic area and its surroundings should be viewed as a whole as an interrelated unity, whose coherence and identity depend on the association of its components, including human activities, buildings, spatial structures and the surrounding environment” [14]. Heritage and the environment share a complex interrelationship, and the environment is an indispensable component of cultural heritage areas, adding value to heritage and existing as a co-creator of heritage [15,16]. However, after the successful nomination of World Heritage sites, the landscape conservation and sustainable development of heritage sites have always been neglected. Local conservation and planning efforts for cultural heritage still remain in the form of the over-protection and renovation of buildings or cultural sites. Large-scale, disorderly restoration inevitably results in the loss of heritage structures and cultural information [17], and a number of projects have been criticized for their destructive restoration [18,19].

LCH is a geospatial unit covering a large area, which may span provincial, municipal, or even national scales, with a complex natural environment and rich cultural heritage resources [19], and faces serious conservation and management problems. Due to urbanization, the biophysical conditions of the environment in heritage areas are changing [2,20,21], resulting in an irreversible loss of heritage values and resources [22]. Heritage areas are a U.S. approach to the preservation of the country’s large-scale cultural landscapes [23] that involves the protection of larger-scale unique resources, either natural resources, such as rivers, lakes, or mountains, or cultural resources, such as canals, railroads, and roads. Guided by the heritage area concept, the object of heritage conservation has shifted from traditional single isolated heritage sites to regional cultural landscapes with human habitation [24]. Not only the US but also many other regions have proposed relevant policies and methods for the holistic conservation of cultural heritage areas, such as China’s national cultural park system [25], Italy’s concept of planned preventive conservation (PPC) [26], and so on. However, there is still a lack of a unified and adaptive approach to integrate large-scale linear cultural heritage assets in the surrounding environment.

The integration of landscape and heritage studies has great strategic potential for creating new connections between heritage resources in a region [27]. The landscape proved to be a suitable concept for enhancing cultural character and nature conservation [28]. Cultural heritage landscapes have been recognized as landscapes of high value [29,30], but they are very vulnerable to change. In recent years, the international heritage field has begun to implement programs such as the Connecting Practice Project, Nature–Culture/Culture–Nature Journey, etc., aimed at collaborative expeditions to registered natural or cultural heritage sites to identify the interconnections between natural and cultural values and actively promote integrated nature–culture management approaches [31,32]. Concepts such as “biocultural diversity” and “resilience” have also been developed to connect nature and culture programs [33]. Based on the above concepts, this study attempts to establish a methodology to scientifically recognize and assess the important components and attributes of cultural heritage and the surrounding environment under the premise of the variable landscape character of heritage sites [34,35] and carry out landscape-scale design and planning by scientifically combining natural and cultural resources [36,37] to ensure the holistic conservation of cultural heritage and the natural environment.

2.2. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA)

Landscape character assessment (LCA) is a set of recognized techniques and procedures of the European Landscape Convention (ELC) [38,39,40] for identifying countries, regions, or places with different characters, including the process of landscape characterization and making judgments based on landscape character, which can be used to integrate natural and cultural landscapes and people’s perceptions. LCA provides a communication reference tool that promotes a better understanding of landscape resources among researchers, managers, and planners [39,41,42], enabling decision makers to consider future landscape planning and development strategies for the region. The LCA method is currently diversified and practiced in European countries and commonly used in territorial spatial planning [43,44,45], land-use management [46,47], and other applications based on land initiatives [48,49]. Other regions, such as China, have just begun to study landscape characters in national, urban, protected areas, national parks, and other regions [50,51,52]. However, there is a lack of LCA practices for large-scale cultural heritage areas and even fewer studies using LCA for LCH areas [53].

Currently, geographic information systems (GISs) and clustering algorithms are commonly used in LCA [54,55] to improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of identification. Li and Zhang [56] used a GIS-based AP algorithm to visualize and identify landscape character types in the multi-ethnic Wuling Mountains at two levels. Yang et al. [57] used a combination of parametric and holistic methods to hierarchically identify landscape character types and areas in Lushan National Park and its fringes. Lu et al. [58] utilized urban big data and machine learning technology to establish a block-scale urban landscape character evaluation technology system and completed the urban landscapes evaluation of Beijing and Shanghai.

The cultural landscape has been found to be an emerging research frontier in landscape characterization [42]. The European Landscape Convention states that the landscape is an essential part of natural and cultural heritage that expresses its cultural understanding of the landscape [59]. The convention also encourages the exploration and analysis of the characters of cultural landscape in various fields [60]. The landscape character assessment of cultural heritage areas can help to complement and enhance the diversity and uniqueness of cultural heritage [61,62]. However, landscapes are constantly changing over time, with natural and cultural value attributes being deposited over time by generations of communities in a changing context [63]. To manage this change, the contemporary significance of heritage to local communities needs to be considered in urban planning [64]. The UNESCO Recommendation on Historic Urban Landscapes [65] proposes new concepts and approaches to managing change in urban landscapes, placing urban heritage management at the center [66] and identifying heritage values and attributes based on a multidisciplinary and community-driven perspective, resulting in a complex layering of cultural and natural value attributes [67]. Local people, as part of the landscape [68], are the ones who actually use and continually shape the living environment, and their requirements and expectations need to be prioritized and addressed. Community participation is important in determining the variables for LCA [69], so we advocate for a combination of expert perspectives and community resident perspectives to be involved in the assessment process. This helps to provide insights into the interplay between the natural and cultural attributes that distinguish different places from each other and identify important characters.

2.3. The Great Wall’s Heritage Value

As the world’s largest and most widely distributed architectural heritage asset, the Great Wall is a huge military defense project dating back to ancient China, consisting of a system of continuous walls and supporting fortified towers, fortresses, beacon towers, etc. [70,71]. The location, direction, and form of the Great Wall are closely related to the natural geography and topography of the region [72,73]. For generations, the Great Wall has enclosed fertile land and abundant rivers within the territory and controlled areas rich in water and grass resources, oases, and pastures so that they could be developed into cantonment areas, making it difficult for the enemy to survive [74]. With the accumulation of history, the Great Wall has also integrated itself into the rich and colorful landscapes along its route, such as mountains, grasslands, forests, the Gobi, deserts, farmlands, and oases, presenting a landscape character in terms of the fusion of heritage and the environment [70].

The core value of the Great Wall is primarily its role as a military heritage asset, a connotation which includes three types of military functional areas, namely, defense, reclamation, and military intelligence, and their mixture to form a composite functional area [75]. In particular, the fortified towers serve the function of military defense, the fortresses help with military garrison and cultivation, and the beacon towers aid military intelligence and information transmission. Fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers can be regarded as three important aspects of the Great Wall, which form different spatial defense logics and visual landscape characters.

The establishment of a sustainable conservation strategy based on the understanding of authenticity and integrity is an urgent need for the conservation and utilization of Great Wall heritage [76]. The ICOMOS Guidelines on Fortifications and Military Heritage [77] were issued by the ICOMOS International scientific committee on fortifications and military heritage (ICOFORT) in 2021. As the first international guideline on military fortification heritage assets in the heritage field, this document expands the scope of the conservation of traditional military fortification heritage sites by recommending synergistic conservation management and the valuation of military fortification facilities and the surrounding cultural landscape. The conservation of Great Wall heritage should continue to focus not only on the heritage asset itself but also on the overall authenticity and synergy of its surrounding environment [70]. Systematic research on the cultural landscape of the Great Wall should be carried out to promote a deeper understanding of its heritage value through the in-depth coupling of cultural heritage and the natural environment and protect the regional heritage network formed by cultural heritage and the natural environment as a whole.

This study aims to use the LCA as a tool for integrating cultural heritage with the surrounding natural environment, thus identifying the landscape characteristics of large-scale cultural heritage areas and forming a zoning of the heritage landscape character, so as to put forward new requirements for the conservation, management, and planning of heritage sites. The main contributions are the following: (1) mapping and briefly describing the landscape character types of the Great Wall heritage area in Beijing using available data at the level of the natural environment and cultural heritage; (2) further exploring the deep coupling relationship between the natural ecological environment and cultural heritage in the Great Wall area; and (3) analyzing the spatial pattern of the Great Wall’s cultural landscapes through case studies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

The Great Wall is a collective name for the massive military projects built by ancient China at different times to defend the country from nomadic invasions from north of the Serbian border. In particular, the Great Wall of Beijing, which has covered the military function of safeguarding the security of the capital since ancient times, is the best-preserved, most valuable, most complicated, and culturally rich section, which formed a military defense system with the Great Wall’s fortified towers, beacons, and fortresses in the Ming Dynasty [78]. With the accumulation of history, the Great Wall heritage areas have gradually formed a variety of cultural forms such as temple culture, red legacy of war resistance culture, transportation route culture, and mausoleum culture, showing the rich cultural diversity and social characters of the area [79]. The Great Wall of Beijing has historically played an important role in the defense of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, profoundly influencing the human–land relations in the mountainous areas north of Beijing. Although the military function of the Great Wall has gradually receded, the influence of its military culture and the various forms of culture derived from it have not been fully demonstrated.

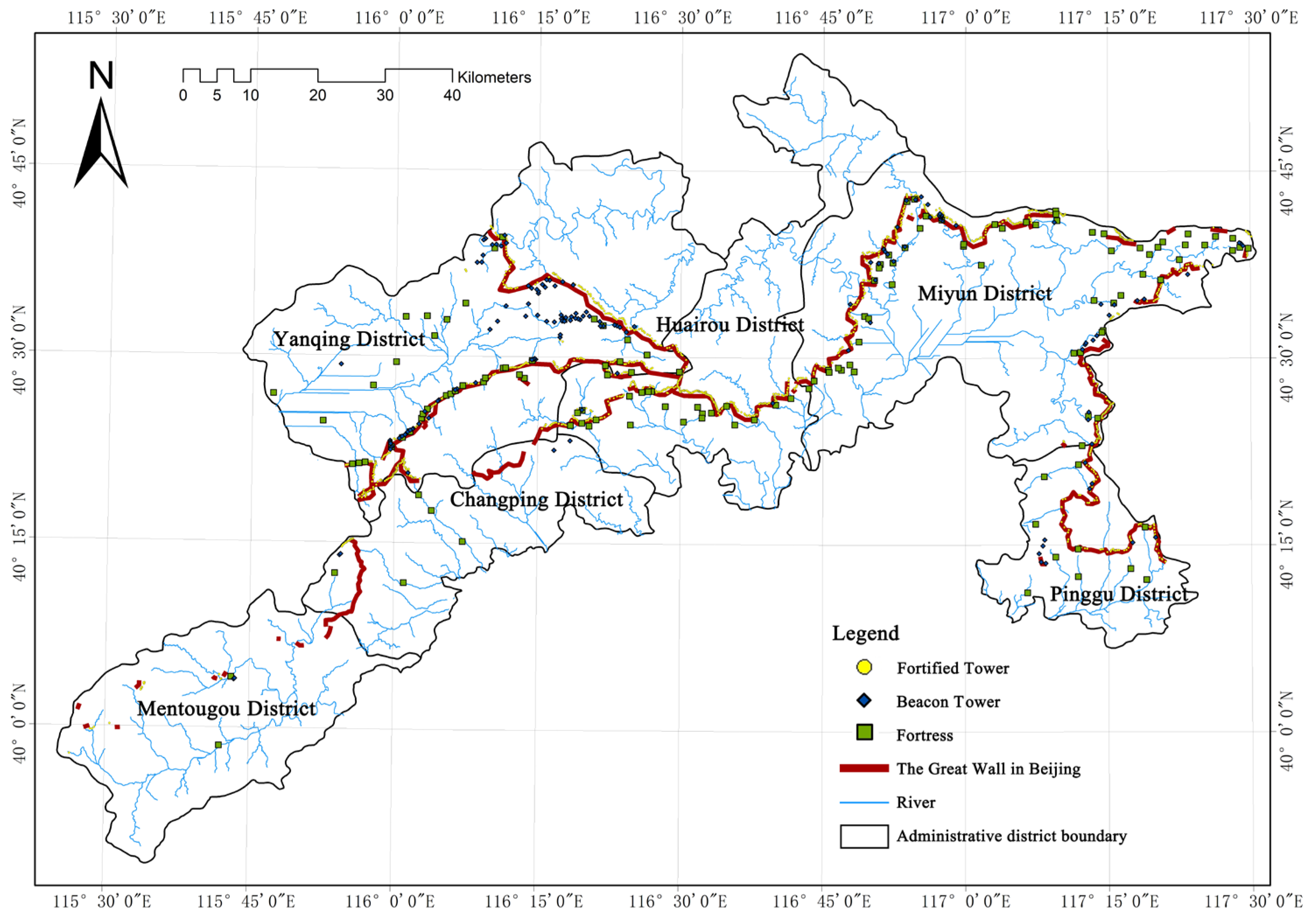

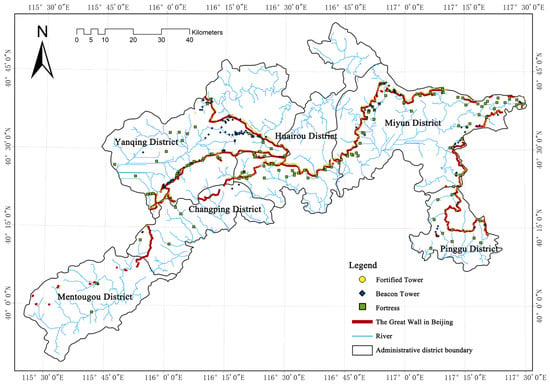

The study area is the “Beijing Great Wall Cultural Belt” and its extension (Figure 1), which is delineated in the “Plan for the Protection and Development of the Beijing Great Wall Cultural Belt (2018–2035)” [79], with an area of about 5142.54 square kilometers, accounting for about 30% of the area of the Beijing Municipal Government. The Ming Great Wall in Beijing is about 600 km long, with 1487 fortified towers, 142 fortresses, and 149 beacon towers. The study area is rich in resources of cultural heritage and the natural landscape, which is typical of large-scale linear cultural heritage areas and representative of the sustainable utilization of historical culture and natural ecology.

Figure 1.

The research area and the distribution of side walls, fortified towers, beacon towers, and fortresses.

3.2. Landscape Character Assessment Based on the Coupling of Heritage and the Environment

3.2.1. Methodology

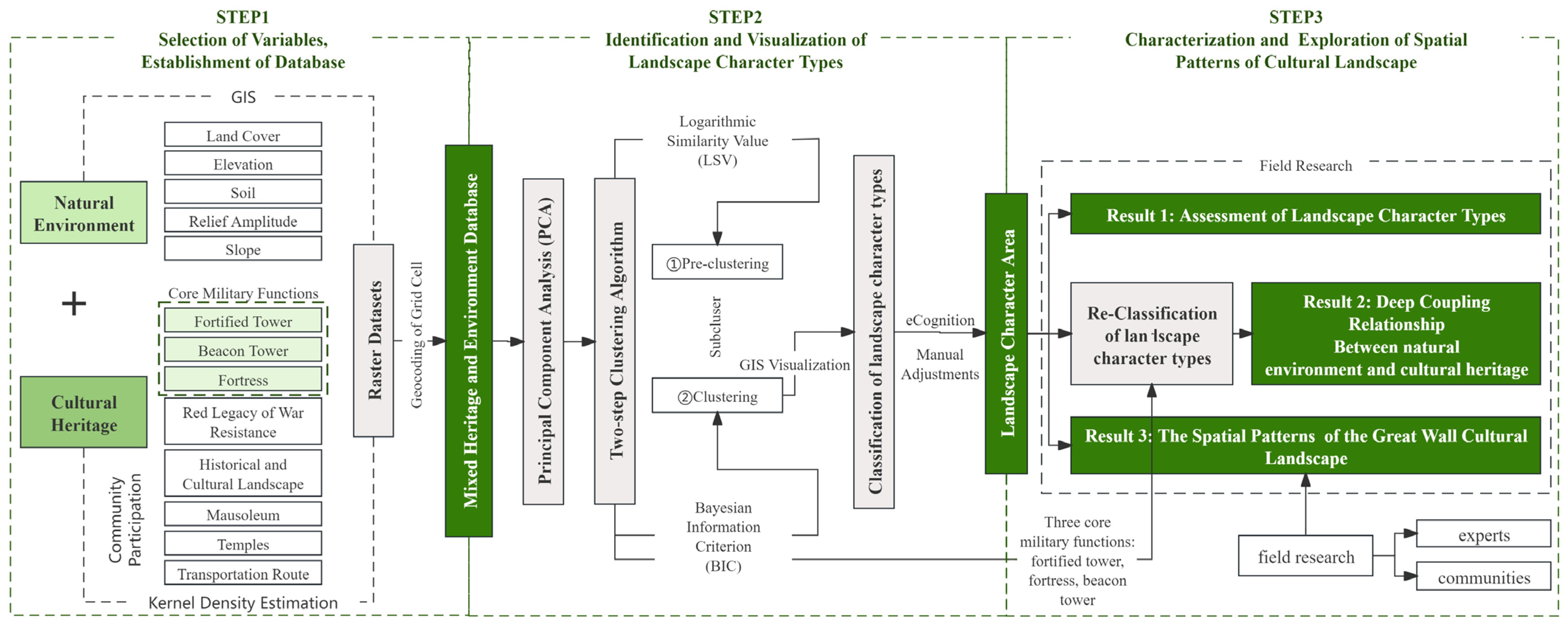

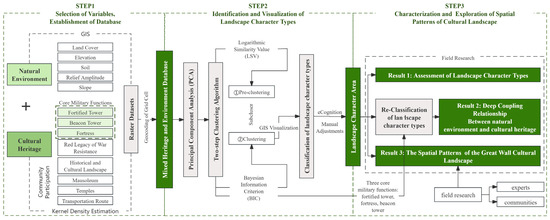

The research process (Figure 2) was divided into three steps: (1) Selection of variables and establishment of a database: collecting data on the research area to construct a mixed heritage–environment database of the Beijing Great Wall heritage area. (2) Identification and Visualization of Landscape Character Types: Using GIS to overlay the variables’ data then using principal component analysis (PCA) and the two-step clustering algorithm to identify, classify, and visualize the landscape character types, and, finally, using the eCognition 9.0 software and manually delineating and adjusting the landscape character areas in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area. (3) Characterization and exploration of spatial patterns of the cultural landscape (Result): Firstly, we described the landscape character types based on the results of field research and a cluster analysis, then reclassified the landscape character types based on the density ratio of the three core military and defense heritage assets (fortified tower–fortress–beacon tower) and further explored the deep coupling relationship between the natural ecological environment and cultural heritage in the core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site, and, finally, we discussed the spatial pattern and multifaceted value of the Great Wall cultural landscape through case studies.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework for landscape character assessment based on the integration of heritage and the environment.

3.2.2. Selection of Variables and Establishment of Database

The variables included two levels: natural landscape and cultural heritage. The selection of the variables at the natural landscape level referred to the common indicators used in the landscape character assessment of the UK [38] and the landscape character assessment of mountainous regions in China [56,57,80]. The natural landscape level was defined by five raster datasets: land cover, elevation, relief amplitude, slope, and soil. Table 1 lists the 42 variables derived from the five datasets and the data sources, with capital letters used as acronyms to denote these variables. DEM was used to calculate the elevation, slope, and relief data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) global 30 m resolution DEM data (2020 NASA DEM, https://earthdata.nasa.gov/esds/competitive-programs/measures/nasadem, accessed on 3 November 2022). The west-central part of the study area is at a higher elevation than the eastern part, with significant variations in relief and slope, with a maximum relief of 200 m and a maximum slope of 80 degrees. The land cover data came from the 2020 Global 30 m Ground Cover Fine Classification Product (http://data.casearth.cn/sdo/detail/5fbc7904819aec1ea2dd7061, accessed on 18 October 2022) of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Information Innovation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. After the mosaicking, cropping, and processing steps, the Beijing Great Wall heritage area was classified into 16 land cover types. Soil data were obtained from the 1:1,000,000 HWSD V1.2 provided by the Harmonized World Soil Database (HWSD, http://www.fao.org/soils-portal/soil-survey/soil-maps-and-databases/harmonized-world-soil-database-v12/en/, accessed on 25 October 2022), in which the study area covered nine soil types, such as brown soil, cinnamon soil, and skeletal soil. The different resolutions were unified by the nearest neighbor method of resampling using GISs.

Table 1.

Variables used for landscape classification at the natural landscape level.

The selection of cultural heritage-level variables was based on expert judgment and also took into account the traditions and perceptions of local communities regarding the cultural landscape of the Great Wall. Collectively, the cultural heritage connotation of the Great Wall could be defined by three core military functional heritage assets and their additional cultural resources. Table 2 lists nine cultural heritage variables and data sources. The Great Wall military defense heritage data, consisting of the historical and geographical information on the three military architectural heritage assets of the Great Wall—fortified towers, beacon towers, and fortresses—were derived from the Register of Immovable Cultural Relics of the Third National Cultural Relics Census. For the cultural resources related to the Great Wall, we focused on the rough descriptions of the local communities on elements such as villages, temples, postal routes, anti-war heritage, royal tombs, stone carvings, and waterfalls. The records and memories of local people about the culture of the Great Wall were fragmented, so we only recorded the keywords based on their historical information or oral descriptions. After screening and merging nearly 30 keywords, a total of five cultural heritage variables were summarized: military defense villages (122), transportation routes (14), temples (139), red legacy of war resistance (59), mausoleum (22), and historical and cultural landscapes (30). The point data were derived from the Beijing Great Wall Cultural Belt Protection and Development Plan (2018–2035).

Table 2.

Variables used for landscape classification at the cultural heritage level.

Military defense villages were military guards, posts, and fortresses along the Great Wall, most of which had been continuously growing and expanding to become natural villages, which have preserved many tangible and intangible cultural heritage aspects, such as traditional folk beliefs and farming life. Ancient transportation routes, postal stations, and modern transportation facilities along the Great Wall objectively ensured the smooth flow of trade from the east to the west and from the north to the south of Beijing. A large number of military settlements with garrison and production emerged, along with the large-scale construction of the Great Wall, and a large number of temples and other religious belief spaces were also built to pray for peace, which also promoted multi-ethnic exchanges and the prosperity of military culture along the transportation route. The Great Wall Resistance War was an important part of the early anti-Japanese struggle, and the red legacy of war resistance in the study area includes military facilities and places where the events took place, memorial sites, etc. The mausoleums are the sites of the World Heritage Ming Tombs, and the Great Wall was built partly to guard these imperial tombs. The historical and cultural landscape refers to a number of natural landscape attractions along the Great Wall that have historical and cultural information. All the above heritage information is point vector data, which we chose to analyze for kernel density to facilitate the conversion to raster data for the subsequent computational work.

We evenly divided the study area into 27,297,500 m × 500 m grid cells by geocoding it based on data resolution and the extent of the study area. With each grid cell defined as a landscape sample point and each cell involving a unique variable of a factor, we integrated all the variable attributes for an overlay analysis and created a geodatabase. For example, one of the grid cells at the broad scale may have been composed of L1, E2, R3, SL4, S5. All spatial analyses and geodatabases were completed using the ArcGIS 10.3 software.

3.2.3. Identification and Visualization of Landscape Character Types

Multivariate analysis and cluster analysis are frequently used in landscape classification [55]. Out of these, we selected a combination of principal component analysis (PCA) and the two-step clustering algorithm for Great Wall heritage data, which were both complex in type and huge in quantity [81,82,83,84]. The algorithm had the advantage of the fast processing of large datasets and the automatic determination of the number of different cluster groupings, and it could handle both continuous and discrete variables [85], effectively overcoming the limitations of the K-Means method.

First, a connectivity matrix of the variables to the grid cells was created, and, since all the data were raster data, the matrix was populated with variables that were either present (1) or absent (0). PCA was then performed to reduce the number of variables [86]. The new variables, as the components, were aggregated by a two-step cluster analysis in SPSS 22. The log similarity value was chosen as the distance measure, and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was chosen as the clustering criterion [87]. Taking advantage of the automatic determination of the cluster number by the software, different cluster distributions and cluster combination occupancy ratios could be formed. After that, types were assigned to all landscape sample points, with each landscape character type representing a specific combination of variables which responded to the landscape character [88]. Finally, the types of attribute data of the landscape sample sites were imported into the grid units within the corresponding geographic encoding to complete the visualization of the types in the GIS map. To delineate the landscape character areas in the eCognition software [89] based on the visualization results, we used a semi-automatic supervised-multi-resolution segmentation tool using a control variable approach to set the parameters of scale, shape, and compactness. Then, in order to delineate the final landscape character areas, the final results were adjusted beforehand by manual delineation based on satellite images.

3.2.4. Characterization and Exploration of Spatial Patterns of the Cultural Landscape

The first step was to describe the Great Wall heritage landscape character area based on the results of landscape character type identification and field research (Section 4.1). Most areas of the Great Wall region are difficult to access, which added a great deal of difficulty to our field research. Before the analysis, it was necessary to conduct a rough research of the study area using drones to assist us in assessing the landscape conditions and integrity so as to clarify the main characters, attributes, and distribution areas of the landscape. Then, a brief description of the landscape character areas was made based on the analysis of the clustering results, remote sensing image identification, and natural and social information.

After that, in order to deeply analyze the coupling relationship between heritage and the environment in the Great Wall heritage area (Section 4.2), we reclassified the existing landscape character types. We chose 9 cultural heritage variables (Table 2) in Section 3.2.2 as the cultural elements for identifying the landscape characters of the Great Wall area. But, the fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers were still the most central heritage elements in the Great Wall’s military defense function system, representing defense, cantonment, and military intelligence, respectively, while the other elements were all subsidiary functions. Therefore, based on the identified landscape character types and interpreting the outliers of the two-step cluster analysis, we reclassified the landscape character types based on the percentage of the variables of the fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers, in order to explore the deep coupling relationship between the natural environment and cultural heritage in the Great Wall heritage area.

Finally, due to the wide coverage of the study area, we selected typical cases for in-depth research to mark the characteristic patterns of the area’s cultural landscape (Section 4.3) and draw targeted directions for landscape conservation, planning, and management (Section 5). The field survey sheet (Appendix B) was drawn up for the geographic distribution of the cultural elements, the spatial pattern of the cultural landscape, and the visual assessment. In the visual assessment part, we invited experts from different disciplines, such as landscape, heritage conservation, and history, and public participation, such as Great Wall protectors, volunteers, and directors of cultural relic institutes and community residents, to conduct a joint scoring of these elements and recorded both sides’ detailed descriptions of the landscape characters of the typical areas. After the GIS analysis and field research, we drew a spatial pattern map of the cultural landscape in the core area of the Beijing Great Wall Heritage, which included five aspects: (i) pattern category: random or regular; (ii) typical pattern combinations: obtained by extracting, analyzing, and summarizing the patterns of all the patches of the cultural landscapes; (iii) specific characteristics: obtained from the above cluster analysis, field research, and pattern extraction; (iv) occurrence of landscape character type related to geographic location: marked the location of each landscape character type on Google map and analyzed its specificity; and (v) typical case: selected typical cases in the study area to draw the boundary of the heritage elements and patches.

4. Results

4.1. Zoning and Description of Landscape Character Types

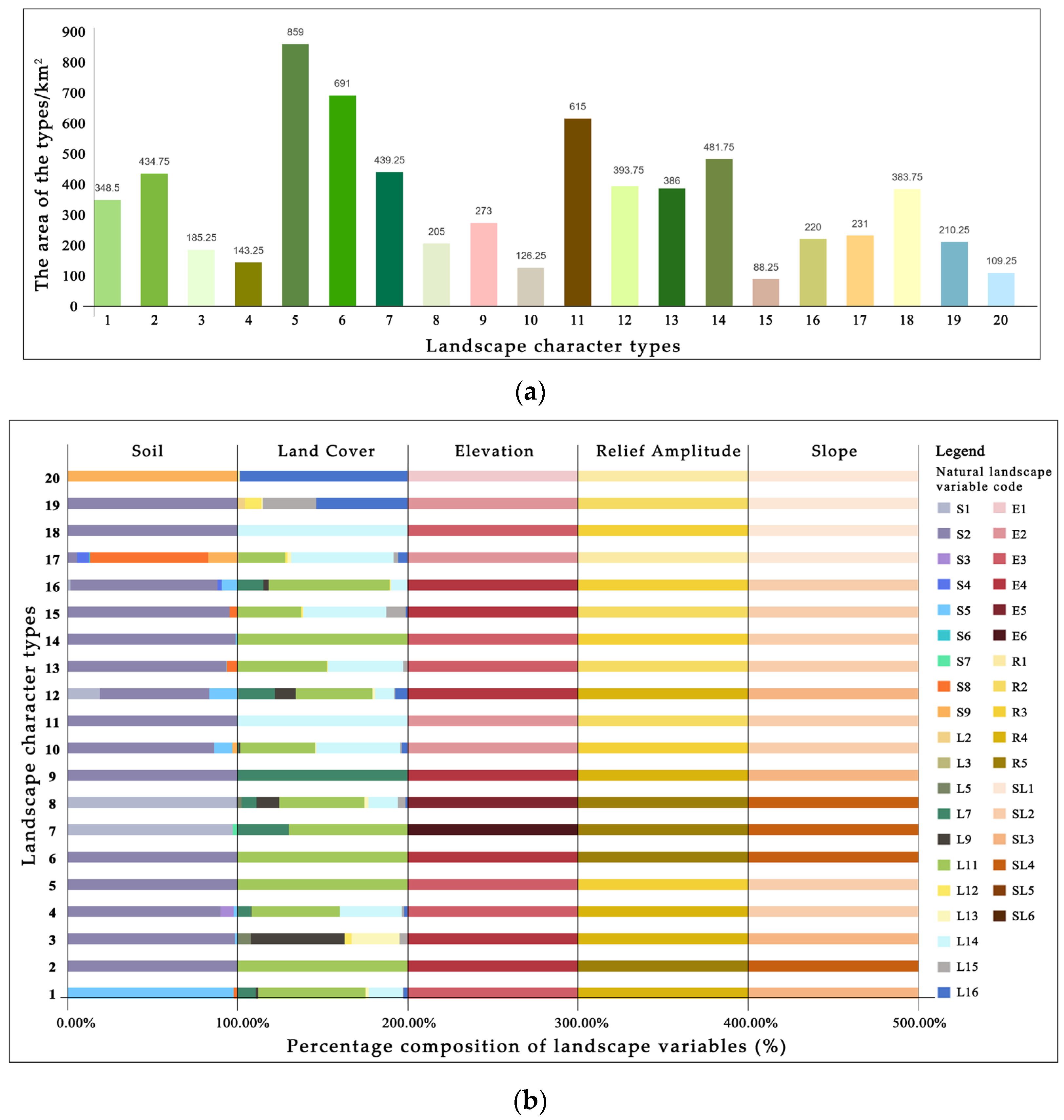

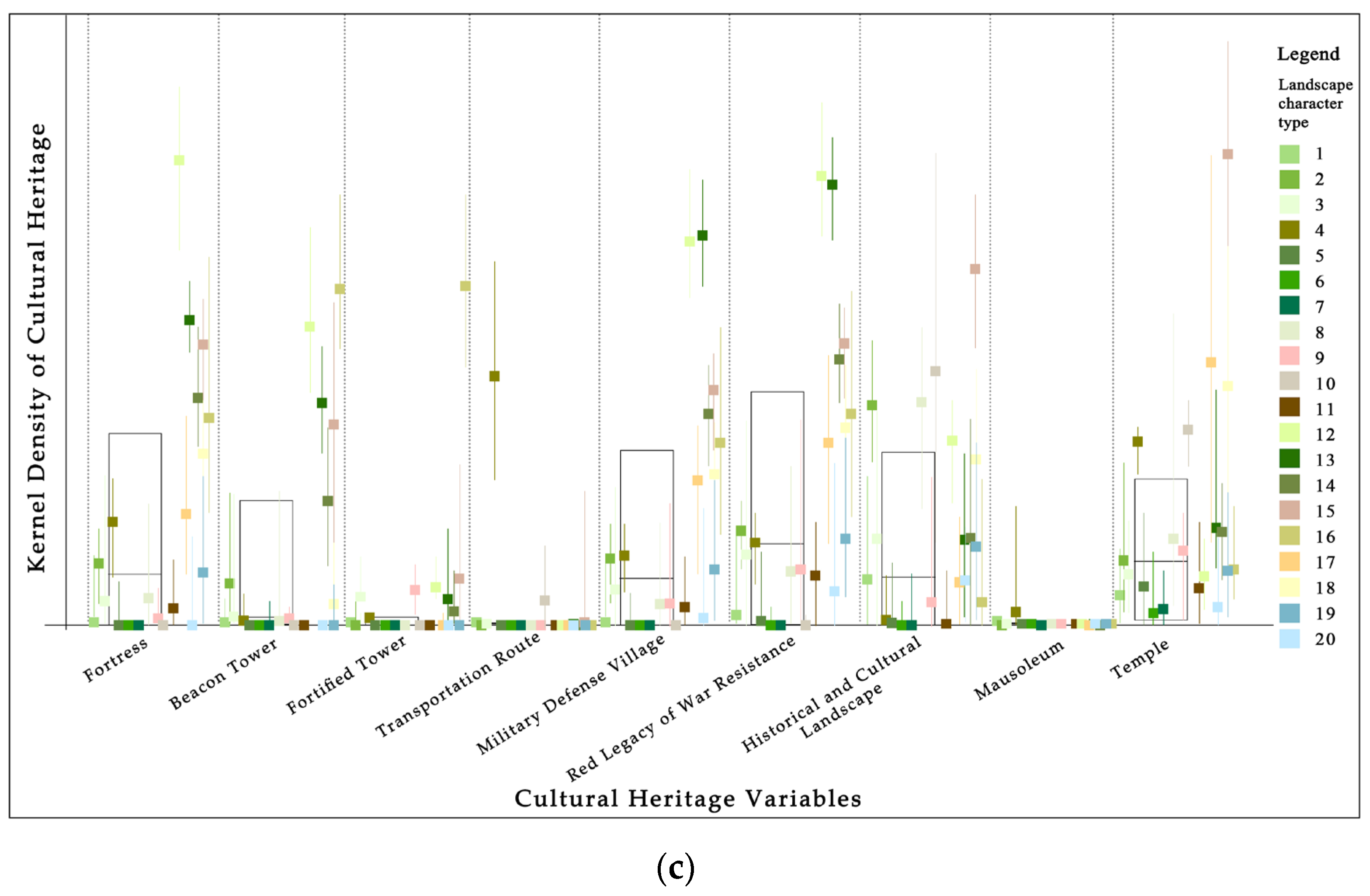

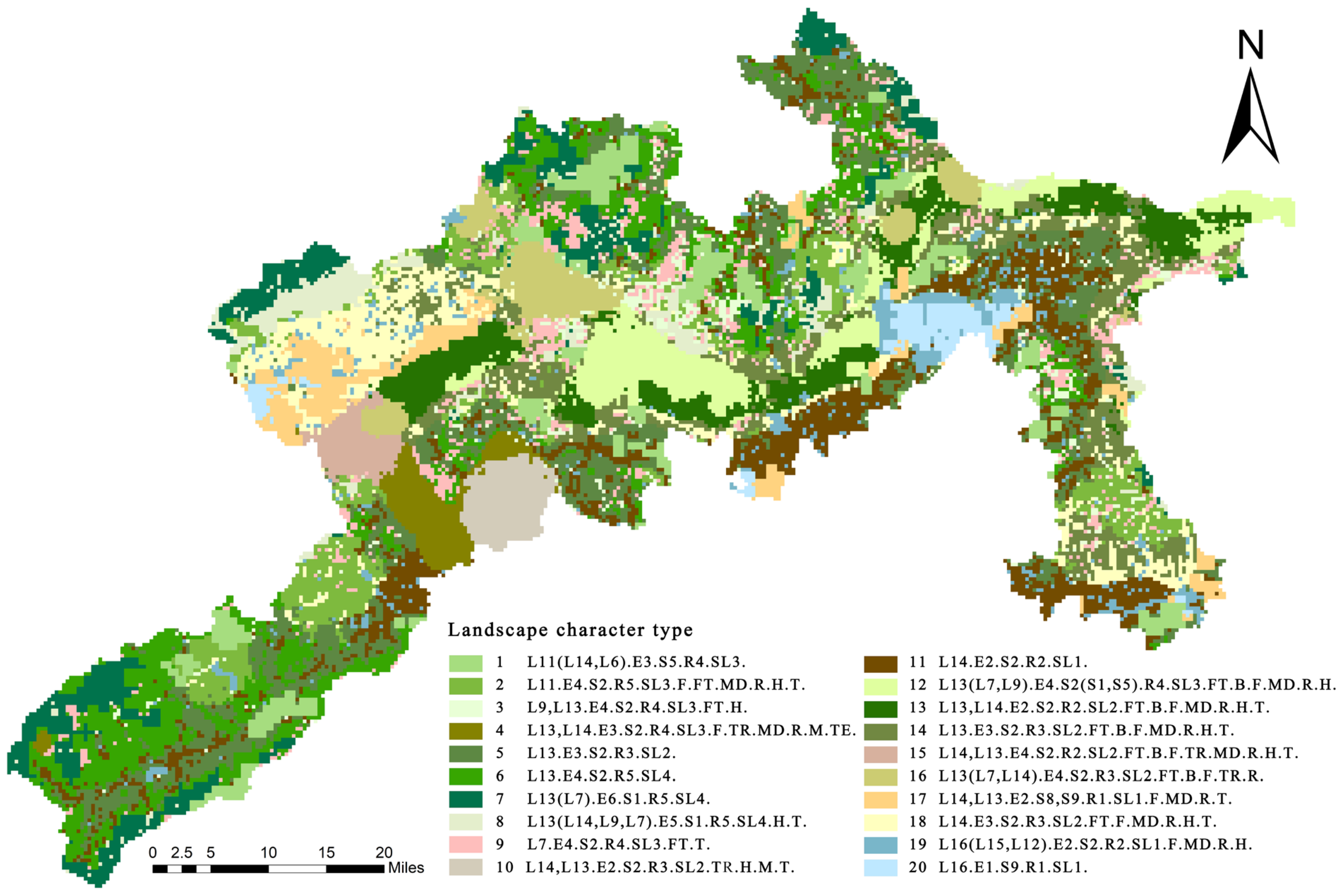

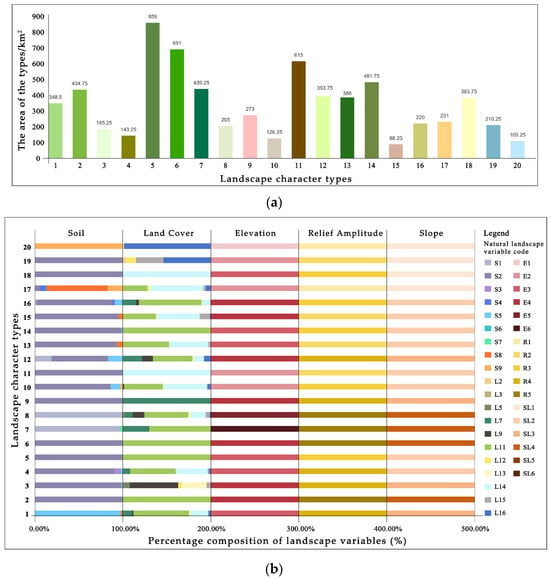

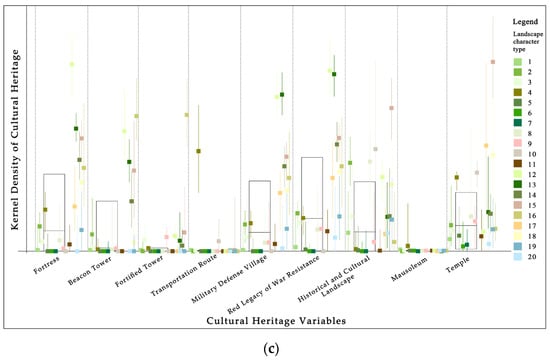

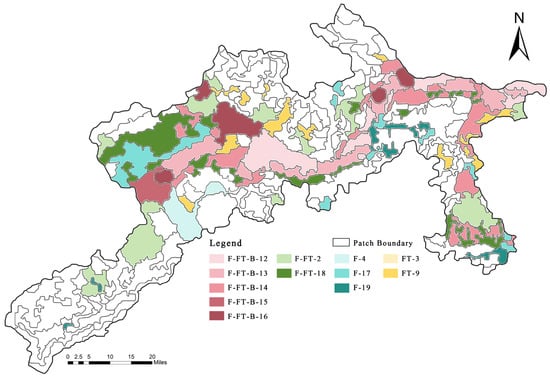

A total of 20 landscape character types were identified in the study area after database construction and classification via the clustering algorithm (Figure 3). According to the combination of clustering occupancy (Figure 3a), the largest area shares were types 5, 6, 11, and 14, all of which had a proportion of more than 7% and, thus, became the decisive landscape character types in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area. In addition, based on the analysis of two-step clustering, the percentage of cultural and natural variables in each landscape character type (Figure 3b,c) could clarify the dominant heritage and natural elements behind the 20 landscape character types, which made it possible to explain the complex cultural landscape character of the Beijing Great Wall heritage area. The machine-recognized landscape character type map of the Beijing Great Wall heritage area was obtained after the visualization in GIS, and the interpretation of the landscape character type was indicated by the code name (Figure 4), e.g., type 12 was named L3 (L7, L9).E4.S2 (S1, S5). R4.SL3.FT.B.F.MD.R.H, meaning that the majority of the land cover was grassland and a small portion of it was closed evergreen/deciduous needle-leaved forest, with an altitude of 600–800 m. The main soil type was cinnamon soil, with a small portion of brown soil and skeletal soil, with a relief amplitude of 80–110 m and a slope of 15–20 degrees, with a dense distribution of the three types of military defense buildings—fortified towers, beacon towers, and fortresses—and a large number of military defense villages, red legacies of war resistance, and historical and cultural landscapes.

Figure 3.

Results of the two-step cluster analysis: (a) the area of the landscape character types of the Beijing Great Wall heritage area; (b) the proportion of the various natural landscape-level variables in each landscape character type (link to Table 1); and (c) the box plots of the kernel densities of the cultural heritage variables for each landscape character type (link to Table 2).

Figure 4.

Map of landscape character types in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area (machine identification).

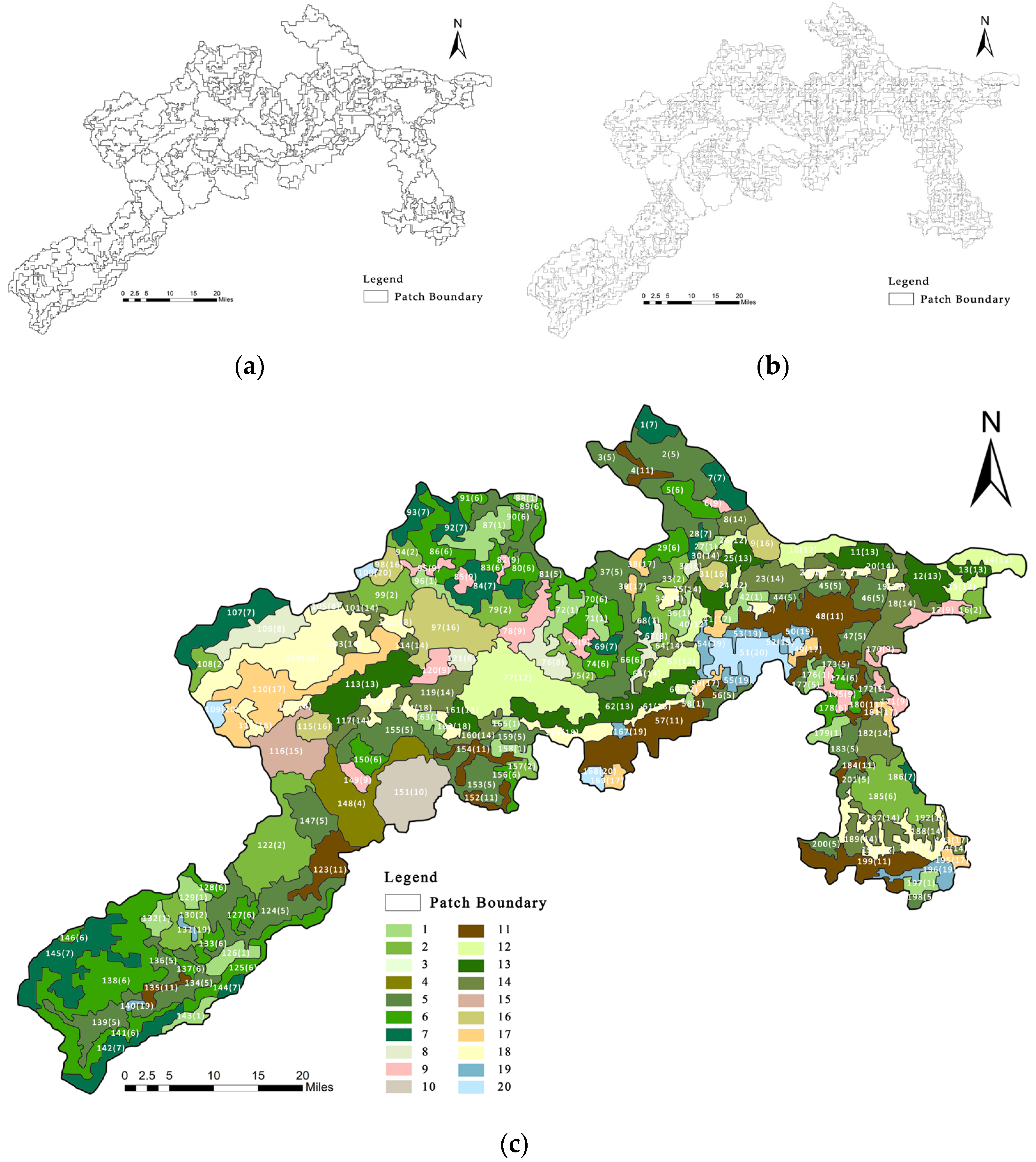

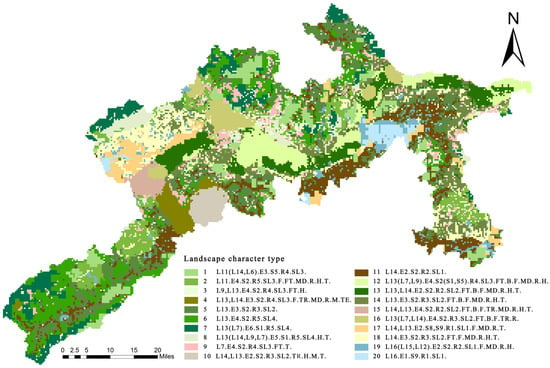

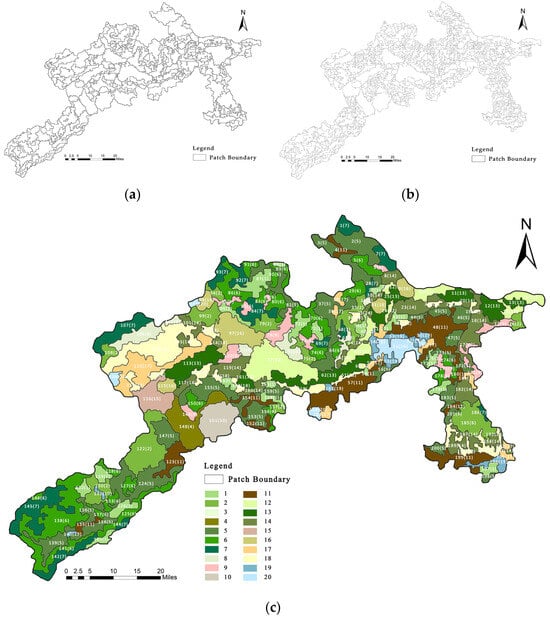

Then, the eCognition tool was used to delineate the final landscape character areas, and the visualization results were compared with the remote sensing images with two sets of machine-learning parameters of scale, shape, and compactness of 30, 0.4, and 0.5 and 50, 0.4, and 0.5, respectively (Figure 5a,b). After manual adjustment, 201 landscape character areas were finally identified, and the area codes consisted of the landscape character area codes and their landscape character types (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Landscape character areas: (a) delineation in eCognition with scale parameter 30; (b) delineation in eCognition with scale parameter 50; and (c) delineation by manual adjustments.

Type-4: With numerous fortresses located in areas of high relief and low elevation, it is a unique landscape type in the Beijing Great Wall region. The only patch is located in the “Juyongguan Pass Ravine”. This 20 km long ravine is surrounded by two mountains in the east and west, with steep cliffs and narrow roads, making the terrain very dangerous. Therefore, the main road of the Guan Gou including the Shangguan Fortress, the Juyongguan Fortress, the Nankou Fortress, and the Badaling Fortress together constitute the Guan Gou military defense system.

Type-13: It is located in a hilly area with a low terrain, surrounded by grasslands and construction sites. The central part of the area is the site of the Huanghua Fortress and the Bohai Fortress, and, in order to strengthen the defense, a defense system was formed with the most important fortress (Yellow Flower Fortress) as the military command center, with the related facilities (fortified towers and beacon towers) around it and smaller surrounding fortresses. The place was named the Yellow Flower Great Wall (黄花城) because of the yellow flowers on the mountains, and it is also called the Water Great Wall because there are three sections of the Great Wall that enter the water, i.e., the lake disconnects the Great Wall, creating a strange landscape, with the Great Wall playing with water.

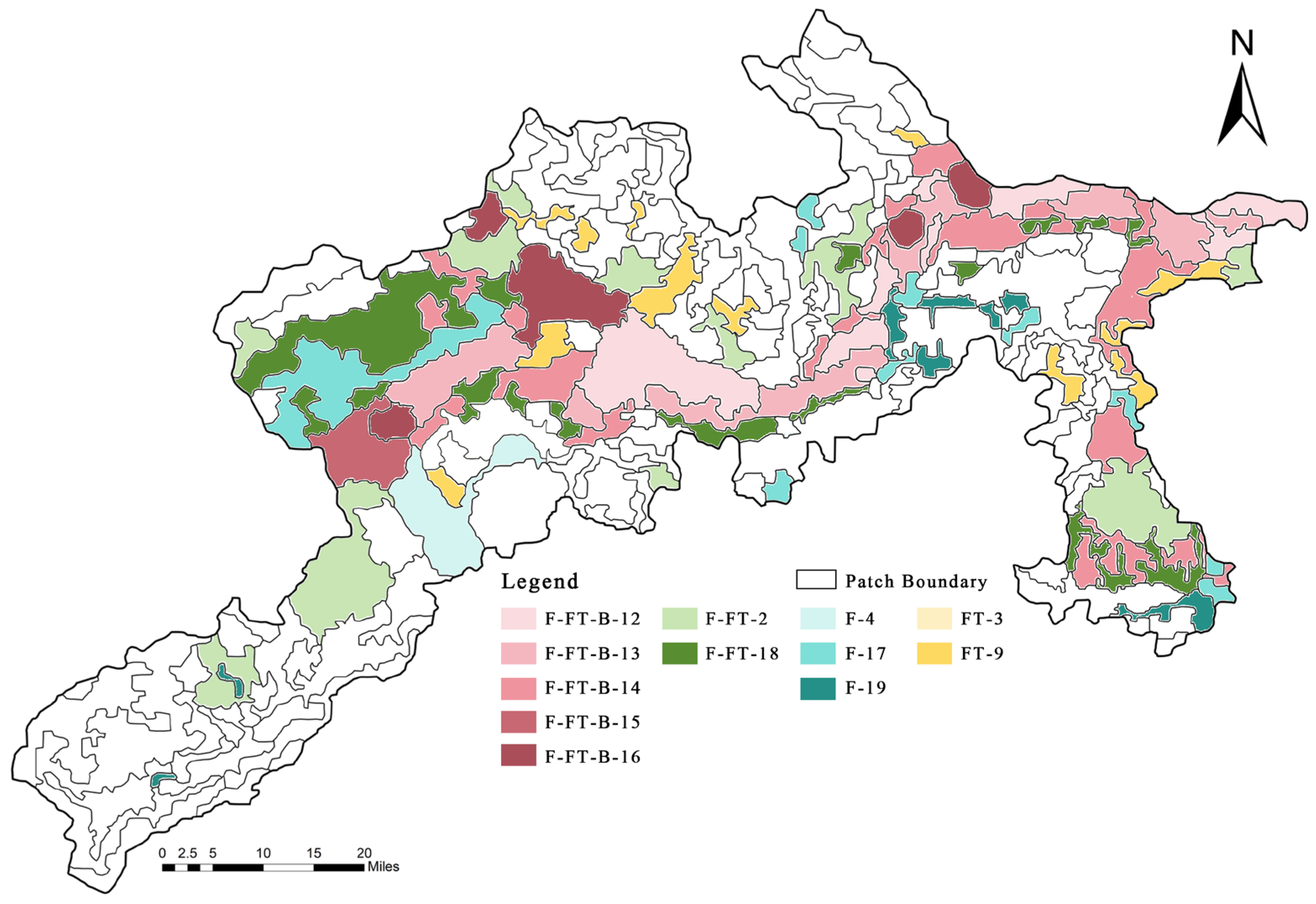

4.2. Coupling of the Cultural Heritage and the Natural Environment in the Core Area of the Great Wall Heritage Site (Reclassification)

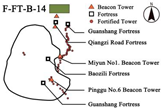

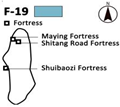

Based on the identified landscape character types (Figure 5c) and interpreting the outliers from the results of the two-step cluster analysis (Figure 3c), we reclassified the types based on the percentage of the variables of the Great Wall’s fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers, and explored the coupling relationship between its heritage and the environment. The reclassification was divided into four major categories and thirteen subcategories, which were named and counted (Table 3). The names of the reclassified landscape character types were formed by the combination of the Great Wall heritage codes (Table 2) and the landscape character types of the first classification, such as F-FT-B, representing the area where the distribution of the Great Wall fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers was relatively concentrated. The areas related to the distribution of the Great Wall heritage assets (F-FT-B, F-FT, F, FT) accounted for 45.83%, 23.81%, 17.06%, and 13.29% of the area, respectively, and the four types together constituted the core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site (Figure 6). There was no similar geospatial relationship between the remaining region (N) and the Great Wall heritage area itself, but there were many settlements in the region (N) that relied on the spirit or brand of the Great Wall for the development of fortresses, which also played an important role in cultural conservation, inheritance, and utilization. Since this study discusses the coupling relationship between the Great Wall heritage assets and the surrounding environment, the region (N) is not included in the subsequent analysis of this study, at least for the time being.

Table 3.

Natural and cultural information on the reclassification of the core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site.

Figure 6.

The core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site.

According to the analysis in Table 3, it was found that (1) in the core area of the Great Wall heritage site exist rich natural environment characters. In terms of land cover, most of the areas were dominated by grassland (L11), construction land (L14), and woodland (L5, L7, L9), with a small amount of wetland (L13) and bare land (L15). In terms of the degree of relief amplitude, most of the areas were between 50 and 100 m (60%), with obvious reliefs. In terms of elevation, most of the areas were located at an elevation of about 400–700 m (55%), and a small portion of this elevation was above 700 m (21%). From the point of view of the slope, most of the areas were in the range of 14–21 degrees (56%), so most of the distribution areas of Great Wall heritage assets were steep slopes according to the international slope grades. In terms of soil, the vast majority was cinnamon soil (S2), a small portion of brown soil (S1) and skeletal soil (S5), and a small amount of fluvo-aquic soil (S8) and reservoirs (S9).

(2) In terms of the reclassified types, there was a unique combination of culture and nature in the core area of the Great Wall heritage site. The F-FT-B type had the largest share of area (45.83%), which was the area with the richest Great Wall heritage types, and its land cover types were also the most abundant; the F-FT tended to be distributed in a single land cover type, dominated by grassland and construction land, and was distributed on mountains and plateaus, with a relatively homogeneous landscape environment. The F-FT type, compared to the other categories, was distributed at a lower altitude, with most of these areas located in the valley areas with a lower degree of undulation, aiming at controlling water sources and promoting the production of cantonment, with a few of them located in valley areas with a higher degree of undulation, mainly for military defense. Compared to the other categories, the F type was located at a lower altitude, mostly in the valley area with a lower degree of undulation, with the goal of controlling water sources and promoting the production of fields, and a small portion of it was located in a valley area with a higher degree of relief, focusing on the main goal of military defense. The FT type was also located in the mountainous woodlands with a high degree of altitude and relief, and, according to the increase in the altitude, the land cover along the heritage sites of the Great Wall became more and more homogeneous.

(3) Generally speaking, the vast majority (73%) of the core areas of Great Wall heritage site was located in high-altitude mountainous or hilly areas with a mixed distribution of grasslands and woodlands, a small portion (14%) was located in the plateau areas with an altitude of above 500 m with a mixed distribution of grasslands and construction land, and a smaller portion (13%) was located in the plains with a distribution of grasslands, construction land, and water. This was due to the objective demand of the Great Wall defense system. The defensive role of the Great Wall is reflected in the fact that it tends to be located in mountainous areas with “high mountains and deep valleys” rather than plains with no dangers to defend; among these mountainous areas, woodlands and grasslands are dominant, which is caused by the annual precipitation and overall climate in the region, not man-made factors.

4.3. Spatial Patterns of the Cultural Landscape in the Core Area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage Site

The natural landscape characters of the Great Wall heritage area have changed dynamically from the Ming Dynasty to the present day. Taking into account the stability and intergenerational inheritance of historical geographic structural characters at the regional level, current land use still reflects, to a certain extent, the intrinsic relevance of the historical geographic framework, natural landscape, and cultural elements of the area along the Great Wall. On the one hand, this correlation reflects the historical formation logic of the landscape character of the Great Wall area, providing a functional, historical, and ecological explanation for its landscape pattern; on the other hand, in this study, this correlation is ultimately presented in a certain visual combination mode, and the specific landscape character unit formed by the integration of the natural landscape and cultural heritage has become the material witness and visual characterization of the formation logic behind the Great Wall. From the reclassification (F-FT-B, F-FT, F, FT), the diversity of the different sub-classes within each major category can be seen. In the following section, some typical cases are cited, and their spatial patterns are mapped to explore the spatial patterns of the Great Wall cultural landscape (Appendix B for the details on the rest of the field research cases).

From the spatial patterns of the cultural landscape in the core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site (Table 4), we can find that there is a special connection between the location and arrangement of Great Wall heritage assets and the surrounding natural environment.

Table 4.

Spatial patterns of cultural landscape in the core area of the Beijing Great Wall heritage site.

The F-FT-B can be broadly categorized into regular and random types. Types 12, 14, and 13, in the random type, have a complementary relationship in terms of geographic location, and the pattern map is usually more random. Types 12 and 14 are F, FT, and B elements evenly and densely distributed, with the difference that type 12 is located in steep mountainous, mixed woodland–grassland areas, and type 14 is located in hilly–grassland areas at lower elevations. In contrast, type 13 is the distribution of F and FT-B clusters that are farther apart, their distribution related to the degree of relief and land use, which can be interpreted to mean that these fortresses tend to be situated in plain areas with a predominance of building land, while the fortified towers and beacons tend to be situated in grassland areas with a marked degree of relief for military purposes. Type 15 and type 16, in the regular type, are more special types, out of which the former is more special in terms of its geographic environment. It is located in the northern end of the Forty Mile Pass Ditch, the exit beyond two mountains being an open plateau, where, for military purposes, people needed to build, in the open space, three defensive fortresses, such as the Juyongguan and Badaling Pass military outposts. Type 16 is special in the arrangement of beacon elements, and dozens of beacons are clustered around the F-FT structures to form a defensive belt.

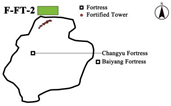

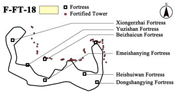

Types 2 and 18 of the F-FT category are relatively random, with type 2 being dominated by the architectural element of fortified towers, which were built in conjunction with pass forts to guard mountain passes, and the surrounding mountains being high and steep, forming a pattern which is easy to defend and difficult to attack. Type 18 is dominated by the architectural element of fortresses, densely packed in the plains around the fortified towers, with a wide variety of functions, and there exist a number of fortresses converted from military to civilian use.

Types 4, 17, and 19, in category F, form a distinctive heritage landscape pattern based on the different functions of the fortress elements. Among them, type 4 is a special type: there are four large battle fortresses in the patch, which are located in the canyon area with a low elevation but a high degree of relief, which had been an excellent place for battle. Type 17 is mostly a cantonment-type fortress, situated at a lower altitude, in a relatively flat and open area, often surrounded by water sources and cultivable land, suitable for cantonment farming, to assume the functions of a combat center and a cantonment of troops and provisions. Type 19 is a garrison type of fortress located near the river, guarding the channel, historically assuming the function of acting as the front line, guarding the pass, and performing real-time monitoring of the enemy situation.

Types 3 and 9 in the FT category are situated in an elevation-dependent environment, with type 3 situated in the mid-mountain region, surrounded by a rich variety of land cover, dominated by dense deciduous coniferous forests, with some wetlands and patches scattered throughout the region. Type 9 is located in the high mountainous area, surrounded by a single type of land cover, mainly closed evergreen coniferous forest. The woodland had a defensive effect in the past, on the one hand containing the onslaught of enemies and, on the other hand, serving as a barrier to prevent detection by the enemy.

5. Discussion

5.1. Landscape Management Based on Coupled Nature–Culture Relationships

Firstly, the Great Wall heritage area needs to break the existing barriers between the different management departments and establish a heritage management organization or system that integrates nature and culture. The Great Wall is a complete cultural ecosystem covering a wide range of natural geographic units, and there are multiple heritage values related to it, such as nature and culture, whose conservation and management in this heritage area require multisectoral synergistic management and planning [90]. Currently, the management system of the Great Wall heritage area lacks a mechanism to assess the value of nature and culture as a whole and manage the landscape [76]. Many management departments involved in the Great Wall heritage area lack a holistic perception of the value of the cultural landscape starting from their own departmental perspectives and interests, such as the local forestry and grassland departments responsible for managing the natural environment around the Great Wall heritage site, the Bureau of Cultural Relics responsible for the protection of the cultural heritage related to the Great Wall, and the Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources responsible for the management of construction activities, with a lack of integrated management among the various departments. This paper shows that the value of the Great Wall heritage site exists as a whole with the natural environment, vegetation, and rural built-up areas. The management of the Great Wall cultural landscape requires the establishment of an integrated lead department or cooperative management mechanism to promote the integrated management of the natural and cultural elements in the Great Wall area.

Secondly, the Great Wall heritage area needs to break traditional administrative boundaries and establish a boundary management method applicable to large-scale linear heritage. The European landscape typology (LANMAP) is a new methodology for characterizing landscapes across the European region [12], which can be used to integrate regulatory boundaries between countries and regions and is an effective tool for providing a real-time basis and a raw dataset for landscape-related policies. From the results of the landscape character zoning of the Great Wall heritage area (Figure 5 and Figure 6) in our study, the character zoning based on the identification of natural and cultural elements did not have any correspondence with the administrative boundaries and heritage protection boundaries drawn by the government. Therefore, for the Great Wall, which is a large-scale linear cultural heritage asset across provinces, cities, and watersheds, it is necessary to break the restriction posed by administrative boundaries, take the characteristic patches coupled with the natural landscape and cultural heritage as the control unit to carry out macro-control efforts, and implement the definition of refined zoning.

Furthermore, the Great Wall heritage area should establish guidelines for landscape change management. Carlier et al. have presented a new landscape classification map for the Republic of Ireland [44], which, for the first time, identifies landscape categories by combining landform and land cover. Their method is applicable to a wide range of users, such as planners and policy makers, and can be used to effectively detect, compare, and analyze ecological and other land use data, as well as generate new landscape classifications by integrating it with other variables to detect landscape change. In the current Great Wall heritage protection plan, the delineation of the Great Wall heritage protection scope and the construction control zones follow an oversimplified and conservative approach—the edges of the architectural cultural heritage areas are horizontally offset by a certain distance, set as the boundary of the protection scope [76]. The construction activities are strictly limited in this area. This spatial scope does not adequately cover the complete landscape unit in which the Great Wall heritage site is located, and its rigid management restricts the local landscape potential and development rights. We suggest that reasonable positive changes to the landscape and facilities along the Great Wall should be allowed, and whether the changes are reasonable or not needs to be based on landscape character assessments, full communication between multiple communities, and the scientific and objective judgment of expert groups.

5.2. Planning and Designing Based on Natural–Cultural Spatial Patterns

With significant pressure on urban and rural construction and tourism development along the Great Wall, how to plan and design heritage areas while respecting cultural heritage and its surrounding landscape has become a primary challenge for heritage conservation and development [91]. The results of the UK’s Exmoor Park Landscape Character Assessment generated a landscape planning guide relevant to this national park [92]. This guidance is intended to be used by planners, developers, land agents, and members of the public submitting planning applications to enable people to think about and understand the relationship between buildings/structures and their landscape environment. This will promote sensitive design and the location of new development projects so that they fits comfortably into the landscape and make a positive contribution to the landscape and settlement characters. This could demonstrate the indicative role of landscape character assessment methods in landscape planning and design. As for the issue of planning and designing heritage sites along the Great Wall, we believe that it should be the focus of future work to plan and design landscapes based on the spatial patterns of cultural landscapes, and we suggest that attempts should be made in the following aspects.

First, the construction land development boundary should be controlled so that it does not occupy core natural and cultural elements. From the coupling relationship between heritage and the environment in the core area of the Great Wall heritage site (Table 3), it can be seen that the land cover types of the Great Wall heritage area are dominated by grassland and woodland, and the combination pattern of grassland, woodland, and heritage is a common landscape pattern which people need to focused on controlling and maintaining.

Secondly, the theme, content, and outward interpretation of a construction project and should be controlled so as not to affect the value and appearance of the heritage site and perpetuate the cultural connotation of the area surrounding the heritage site. For example, F-FT-B-13 is a plain area where a large number of fortresses are concentrated, and the fortresses, their military command system, and the residents’ life and production should be the theme of displays in and utilization of this area.

Further, details such as construction appropriateness and building height should be emphasized so that they do not obscure the connection between the cultural element points and the natural landscape at the perceptual and functional levels. The perceptual dimension is reflected in the sightline relationships between heritage elements or between heritage and the landscape and, in particular, the views between beacons and between beacons and fortresses, which have, historically, a military transmission value, should be carefully assessed and retained. The functional dimension is reflected in the transportation routes between the heritage site and the landscape (e.g., farmland and fortress) or between heritage sites (e.g., between levels of fortresses, or between fortresses and fortified towers), which are hereby proposed to be preserved to highlight the historical functional links between the cultural and natural elements. Thus, local development design in the Great Wall heritage area needs to be refined by respecting the existing spatial pattern that connects nature and culture. The field survey sheet (Appendix B) places more emphasis on the description of the structural character of the cultural landscape and also includes visual and perceptual dimensions, with experts and communities scoring the experience of the whole area, a process which will help to monitor changes in the landscape and provide detailed information for future planning and management [93].

5.3. Historic Landscape Character Study Based on Landscape Archaeology and Historical Documents

The Great Wall, as a historical and cultural landscape, should be placed in a continuous spatial and temporal framework to study the laws of its formation, development, and change and, thus, integrate its historical significance with the contemporary environment. According to the UNESCO [94], the authenticity of heritage has been extended from an heritage asset itself to its surrounding historic environment. The vegetation, agriculture and livelihood practices, and water facilities around the Great Wall are all important components of heritage authenticity. Adopting environmental archaeology and digital simulation to analyze and verify the role of the relationship between nature and culture along the ancient Great Wall is beneficial for the authentic display and reproduction of the Great Wall cultural landscape [95]. In the Ming Dynasty, it was recorded that, for the military defense of the Great Wall and the food supply needs of the army, specific tree types and agricultural activities were located along the Great Wall. However, these records are rather sketchy and lack an empirical scientific basis. In the core scenic spots of the Great Wall heritage area, such as the Badaling Scenic Spot, it is possible to transmit to tourists real information about the historical environment of the Great Wall if physical restoration and digital displays of forest vegetation types, crop types, and water environment and conservation facilities dating back to the Great Wall of the Ming Dynasty can be, respectively, carried out and placed on the basis of environmental archaeology.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

There are three shortcomings in this study. (1) With respect to the selection of variables and the enhancement of the clustering methods, although we upgraded the traditional cultural variables, the variables used in landscape categorization are still limited and the landscape is in a constantly dynamic state [47]. In future studies, the number of variables could be increased, and more clustering methods could be trialed to simultaneously examine and optimize the changing landscape characteristics of the Great Wall heritage area. (2) The area covered by the Great Wall is huge, which can lead to target expansion or a focus shift to new research scopes. Due to the limitation of our research data, this study is only a landscape characterization study of the typical Beijing Great Wall heritage area, with the rich cultural landscape types of other areas of the Great Wall still missing. In the future, this study can be expanded to cover the Great Wall heritage areas in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, and even the whole country, to protect the heritage landscape of the Great Wall in China in a more holistic way, so as to provide a reference for conservation research on linear heritage in China and even the world. (3) The landscape characterization approach based on heritage and the environment is also meaningful for the landscape conservation, planning, and management of other linear heritage areas, including canals, city walls, railroads, and many other heritage types. Linear cultural heritage has prominent natural and cultural characters in large-scale geographical environments, and landscape character assessment should be utilized to integrate and analyze the landscape characters of heritage sites and their surrounding environments, which is of great significance to regional heritage conservation, management, and planning.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we emphasized that heritage conservation and sustainable development in linear heritage areas depend on the integration of heritage and the environment. A conceptual framework for the construction of landscape character in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area is proposed. From the perspective of integrating heritage and the environment, this framework is divided into three steps: database construction, landscape character identification and description, and cultural landscape spatial pattern study. A total of 20 landscape character types of the Great Wall heritage area in Beijing were identified and reclassified around their core historical military orientation, consisting of fortified towers, fortresses, and beacon towers, further obtaining the deep coupling relationship between the natural ecological environment and cultural heritage and the spatial patterns of the cultural landscape. This systematic approach promoted the integration of the Great Wall heritage area at the heritage and environmental levels. In future studies, multidisciplinary data and community participation can be further complemented and optimized to evolve into a multilevel nested landscape management and conservation system at national, regional, and local scales. Due to the effectiveness and flexibility of this methodology, it can be easily applied to other regions of China to facilitate landscape conservation and planning in linear heritage areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H. and W.C.; methodology, W.C.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, D.H. and W.C.; data curation, D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.; writing—review and editing, D.H. and J.Z.; visualization, W.C.; supervision, D.H.; project administration, D.H. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China National Natural Science Foundation, with grants number 52378002 and 52178029.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of landscape character types in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area.

Table A1.

Description of landscape character types in the Beijing Great Wall heritage area.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Surrounded by steep mountainous areas with an average elevation of around 600 m, there are large areas of grassland accompanied by small amounts of construction land and artificial evergreen coniferous forests. The soil type is all skeletal soil, not suitable for agricultural use and treatment. The largest patch is located in the northwestern corner, which is a mountainous ecological conservation area and the location of the Beijing Silica Trees National Geopark. Surrounded by mountains on all sides, the park contains numerous geological, anthropogenic, and natural landscapes and is the only national geopark in North China with typical rare and precious silica tree groups as its main landscape. |

| 2 | Located in a treacherous mountainous area with an average elevation of about 750 m, the unique terrain presents more fortified towers and fortresses to match, historically, the offense and defense efforts in this area. The southwestern corner of the patch is located in the Changyu Fortress, a military fortress of the Ming Dynasty, built in a high mountain valley, next to the White Sheep Fortress, which constitutes the defense line of the Northwest Border Pass. In ancient times, it was a place to resist the invasion of northern nomads, and, in more modern times, it has been a battlefield against Japanese invaders. |

| 3 | Patches are scattered throughout the map. The fortified towers are distributed in a continuous line in the steep mountainous area, with forest vegetation formed by deciduous coniferous forest and deciduous broad-leaved forest with a small amount of wetland distributed on both sides. Nearby are more historical and cultural landscapes such as the Liuli River (the site of China’s early Western Zhou capital) and the Qifeng Mountain (strange peaks, pines, and springs). |

| 4 | Numerous fortresses are located in areas of high relief and low elevation, and the area presents a unique landscape type in the Beijing Great Wall region. The only patch is located in the “Juyongguan Pass Ravine”. This 20 km long ravine is surrounded by two mountains, in the east and west, with steep cliffs and narrow roads, making the terrain very dangerous. Therefore, the main road of the Guan Gou including the Shangguan Fortress, the Juyongguan Fortress, the Nankou Fortress, and the Badaling Fortress together constitute the Guan Gou military defense system. |

| 5 | It is located in a grassy hilly area far from the Great Wall heritage site; the average elevation is around 500 m above the sea level; and the main soil type is brown soil, located on higher ground with a certain slope, well drained, and suitable for fruit trees and crops. |

| 6 | It is located in the Meadow Mountain area, which is far away from the heritage assets of the Great Wall, and the average altitude is around 800 m, with high vegetation coverage, mostly nature reserves, a low population density, and less human interference. |

| 7 | It is located in a high-altitude mountainous area far from the Great Wall heritage site, with an average elevation of around 1100 m. The surrounding landscape is dominated by meadows and woodlands. Influenced by the altitude, the soil type of the area is brown soil, which is an important forest soil type suitable for the development of forestry, with a large number of oak and pine trees distributed in this area. |

| 8 | It is located in a high-altitude mountainous area far away from the Great Wall heritage site, with an average elevation of about 1000 m. The surrounding landscape is rich and diverse, dominated by grasslands, with a small amount of construction land, artificial evergreen coniferous forests, and artificial deciduous coniferous forests. The Beijing Songshan National Nature Reserve and part of the Yudu Mountain Scenic Area are distributed within this plot, with rich historical and cultural landscapes, monasteries, and temples. |

| 9 | The fortified towers are distributed in the steep mountainous terrain, with an average elevation of around 700 m. The surrounding landscape is dominated by artificial evergreen coniferous forests, and there are temples such as the Nine Immortals’ Temple and the Guandi Temple within this plot of land. |

| 10 | The patches are all located in the area of Beijing’s Ming Thirteen Tombs, a complex of burial buildings for Ming emperors, with multiple mausoleum burial sites, listed as a World Heritage Site in 2003. The mausoleum area is surrounded by mountains on three sides and has a vast territory, with the emperors’ tombs staggered in the middle basin, which was regarded as a feng shui site by the Ming Dynasty and was planted with evergreen pine and cypress trees. A large number of villages exist around the mausoleum, most of which are the descendants of the guardians of the mausoleum. Within the mausoleum area, there are cultural heritage sites such as the Thirteen Mausoleums’ Sacred Path (postal transportation road), the Shuigouquan Memorial Forest (historical and cultural landscape), and the Longwangmiao (temple) of Jingling Village. The construction of the Thirteen Mausoleums was closely related to the Great Wall, large sections of which were built not only to guard the capital but also to serve as an important gateway to guard the Thirteen Ming Tombs. |

| 11 | Located in a combination of low mountains and plains, there are the Xiong’erying Fortress and the Zhaitang Fortress. The Zhaitang Fortress is located on a terrain that is relatively flat and is west of Beijing with respect to the main transportation and old trade routes, as the Ming Dynasty built this fortress to guard the ancient road running through it. The Zhaitang Fortress is rich in historical and cultural resources: there are the Lingyue Temple, Ming and Qing Dynasty ancient residential villages, and other historical relics in the city. |

| 12 | Located in a steep mountainous area, the surrounding land types are grassland, artificial evergreen coniferous forests, and artificial deciduous coniferous forests, with more than 90% of vegetation cover and rich soil types. The central patch is the location of the “Beijing Knot” of the Arrowbolt Great Wall, which is the meeting point of the three Great Walls. This section of the Great Wall is the most treacherous and majestic section of the Great Wall in Beijing, with a unique architectural style and a dense number of fortified towers, and it was an important gate to guard the capital and the imperial tombs in the Ming Dynasty. |

| 13 | It is located in a hilly area with a low terrain, surrounded by grasslands and construction sites. The central part of this area is the site of the Huanghua Fortress and the Bohai Fortress, and, in order to strengthen the defense, a defense system was formed with the most important fortress (Yellow Flower Fortress) as the military command center, with the related facilities (fortified towers and beacon towers) around it and smaller surrounding fortresses. The place was named Yellow Flower Great Wall (黄花城) because of the yellow flowers on the mountains, and it is also called the Water Great Wall because there are three sections of the Great Wall that enter the water, i.e., the lake disconnects the Great Wall, creating a strange landscape, with the Great Wall playing with water. |

| 14 | It is located at the edge of the core conservation area of the Great Wall, with great reliefs, an average elevation of about 500 m, and the land type being mainly grassland. The facilities related to fortresses, fortified towers, and beacon towers form a complete and tight military defense system. In addition to the facilities of the Great Wall itself, there are many military defense villages, historical and cultural landscapes, and temples in the area, which are various types of historical and cultural sites related to the Great Wall. |

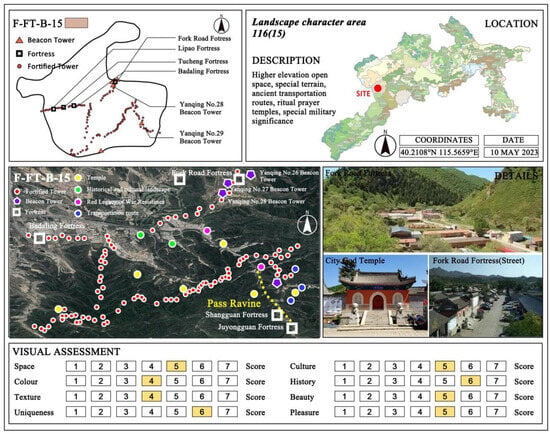

| 15 | The whole patch is located in the northern part of the Badaling Great Wall section in an open area with higher elevation, surrounded by construction land and grassland. There are four fortresses, namely, the Lipao Ancient Fortress, the Tucheng Ancient Fortress, the Badaling Fortress, and the Fork Road Ancient Fortress. The Fork Road Fortress has been a transportation fortress since ancient times and is surrounded by mountains, which are full of red leaves in the fall. This area comprises an historical military cultural zone of the Great Wall and the cultural exchange zone of the northwest seaside, with the Guandi Temple, the Chenghuang Temple, mosque ruins, government offices, mansions, theaters, other architectural remains, and 300-year-old acacia trees, as well as a military drill ground, an ammunition warehouses, and other cultural heritage sites. |

| 16 | Located in a steep mountainous area with an average elevation of about 700 m, the surrounding land is rich in grasslands, artificial evergreen coniferous forests, and construction land. The northwestern part of this patch is a belt of nearly dozens of beacon towers connected in the Yanqing district, and the wall and the belt of the beacon towers historically formed a deep defense system with the fortresses and the fortified towers. |

| 17 | Located in hilly areas of river valleys, the surrounding land is dominated by built-up land and grassland, and the soil is predominantly moist. The fortresses in the patch, such as the Xiangying Fortress and the Ma Ying Fortress, are all abandoned and used for other purposes. There are other patches that are currently used more as wetland parks for public recreation, such as the Mallard Lake Wetland Park and the Sanlihe Wetland Park. |

| 18 | Located in the plain area, it is surrounded by construction land. The northwestern part of this patch is the location of Ming Dynasty fortresses such as Shuangying, Miliangtun, Dongbaimiao Fortress, etc. The fortresses had various functions, not only as barracks but also for postal communications, forming a network system, which is now mostly abandoned. The southeastern part of this patch comprises Xiong’erzhai, Yuzishan, the Beizhai Village, Emeishanying, Heishuiwan, and other Ming Dynasty fortresses, now developed into fortress-city-type villages, adapted from military to civilian use. These fortress cities attach importance to the construction of temples, so the Guandi Temple, the City God Temple, the Niangniang Temple, and other temple buildings can be found here. |

| 19 | The area is mostly located on a riverbank, and the geographical environment, with suitable cultivated land and water sources, was suitable for the construction of fortresses. The largest patch is located around the Miyun Reservoir, with Maying Fortress and Shitanglu Fortress to the west. With the expansion of the reservoir area, Maying Fortress has now sunk to the bottom of the reservoir, and only Shitanglu Fortress still exists. |

| 20 | The central patch is the site of the present-day Miyun Reservoir in Beijing, which is the largest comprehensive water conservancy project in North China and is a water conservation area. The northwestern patch is the site of the present-day Guanting Reservoir in Beijing, surrounded by numerous tourist attractions. |

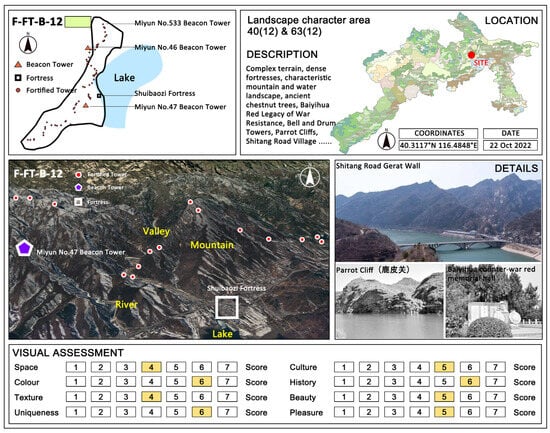

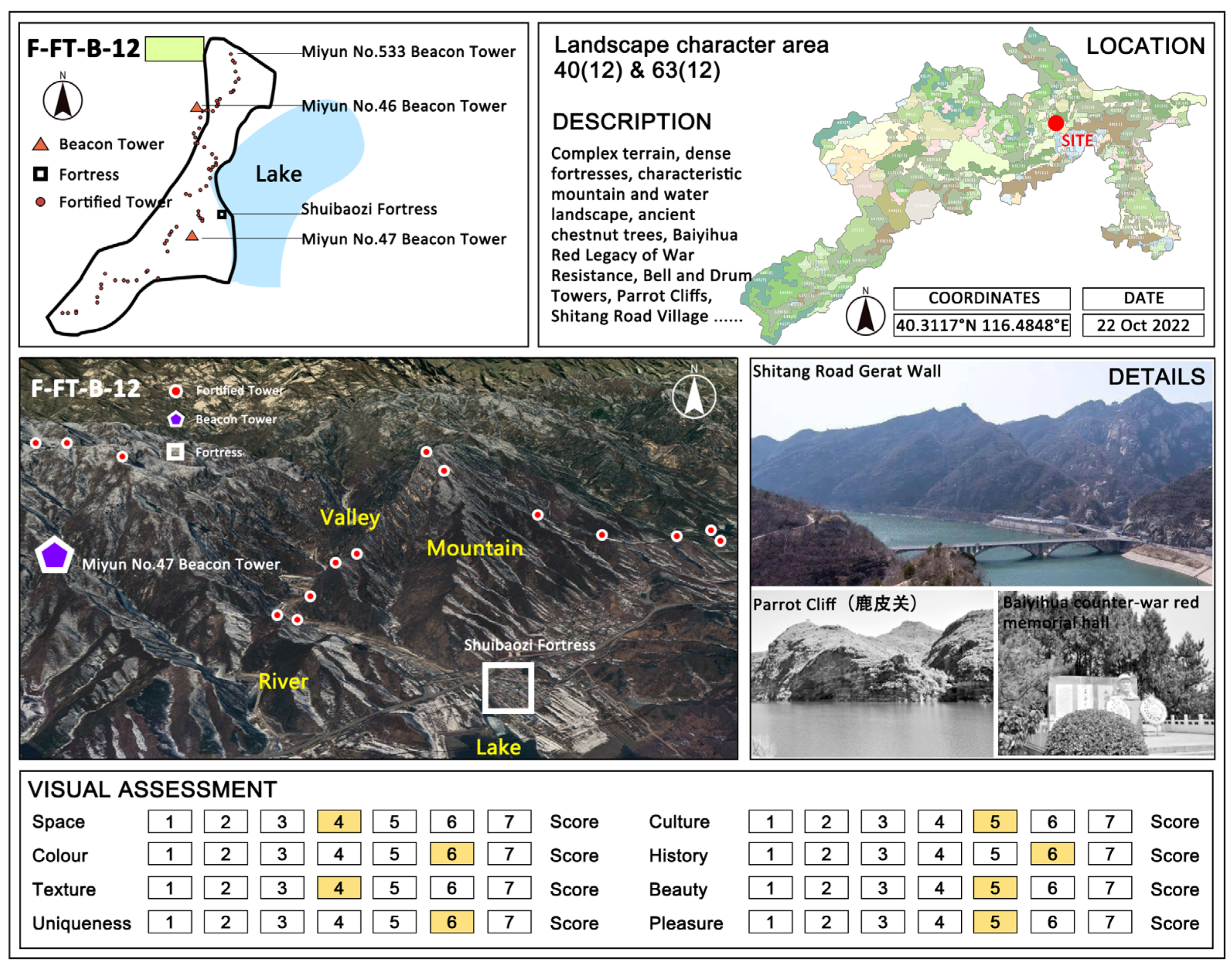

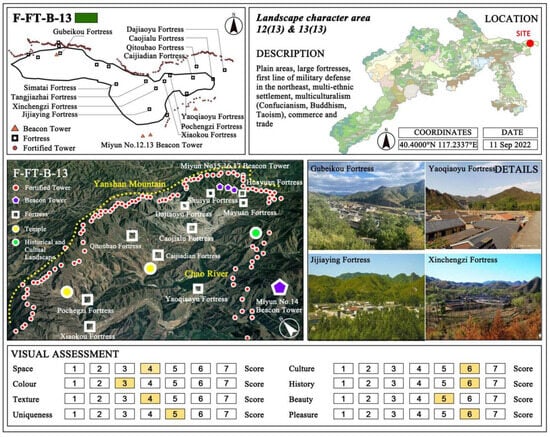

Appendix B

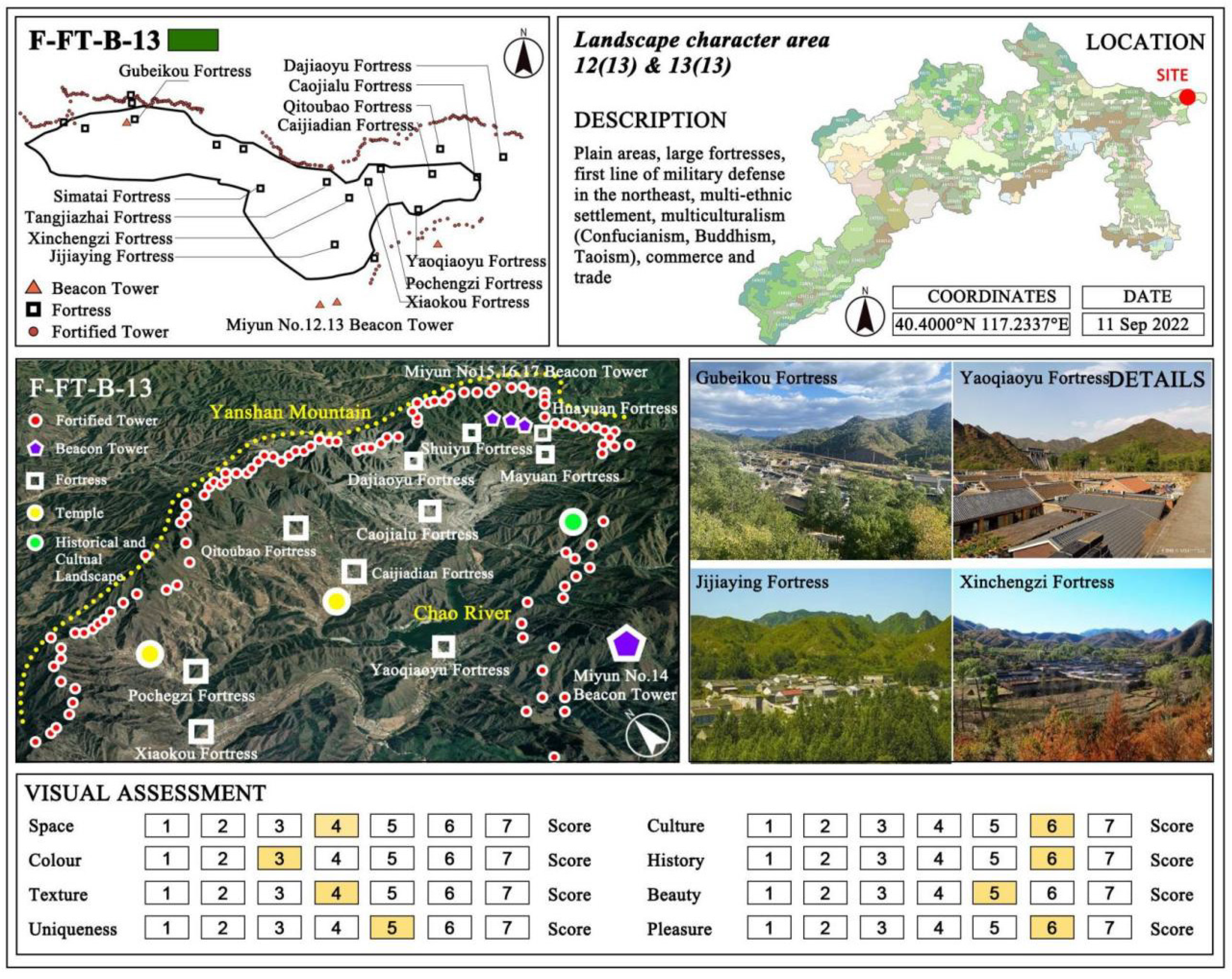

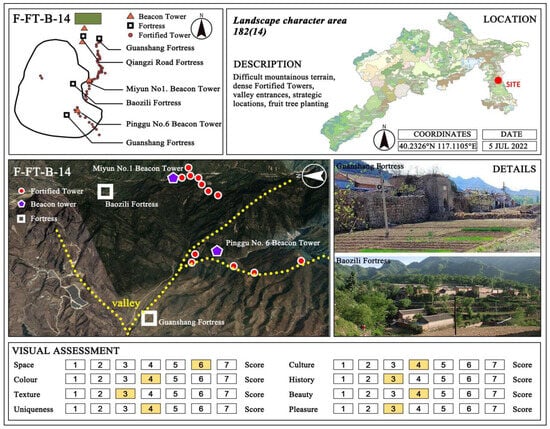

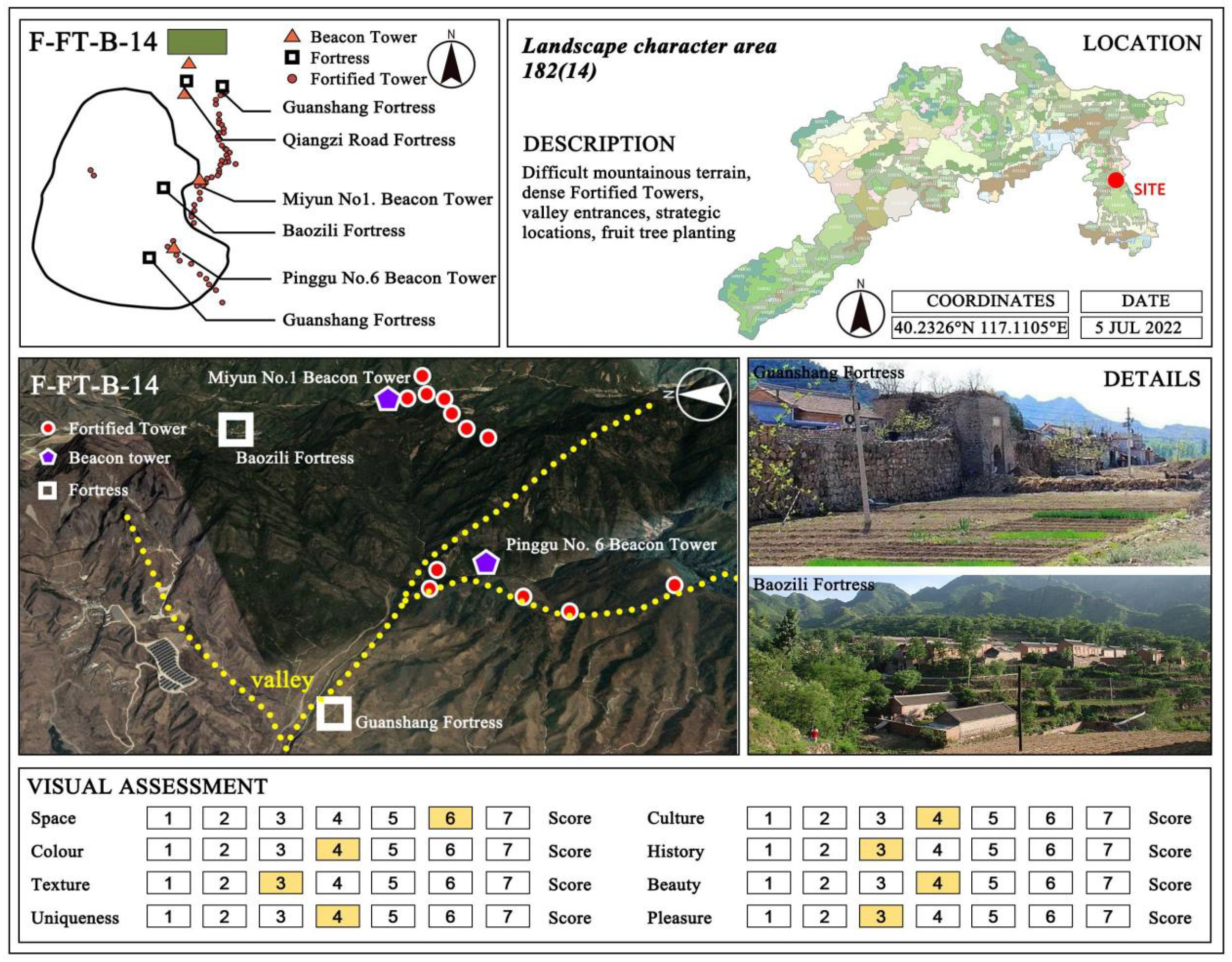

Field survey sheet of the Great Wall cultural landscape: On the upper left is a map of the distribution of the cultural elements; on the upper right is the distribution of the geographic locations and a brief description; on the lower left is a map of the spatial patterns of the cultural landscapes; on the lower right are pictures of the field research; and at the bottom is a visual assessment form (the same goes for all the figures that follow).

Figure A1.

F-FT-B-12 field survey sheet for the Shitang Road (formerly known as the Lupi Pass Great Wall, undeveloped), located in the eastern foothills of the Yunmeng Mountain and the west bank of the Miyun Reservoir. Generally speaking, the Great Wall stretches across the top of the mountain, from west to east, while the Great Wall on Shitang Road has a section that turns sharply downward, in a north–south direction, only because of the towering mountains, complex terrain, dense fortresses, and numerous passes near the river, which were historically easy to defend and difficult to attack. This is a very characteristic landscape area and also the only place where mountains, valleys, rivers, lakes, and the Great Wall converge and overlap. There were chestnut trees here in ancient times. Although the garrison generals in the Ming Dynasty had rations issued by the court, they were located in deep forests and could use chestnuts to fill up their hunger when they encountered floods, torrential rains, or inconveniences in transportation. Here, there are also the Baiyihua Counter-war Red Memorial Hall, the Shitanglu Village, the Bell and Drum Tower, the Parrot Cliff, and other cultural sites.

Figure A1.

F-FT-B-12 field survey sheet for the Shitang Road (formerly known as the Lupi Pass Great Wall, undeveloped), located in the eastern foothills of the Yunmeng Mountain and the west bank of the Miyun Reservoir. Generally speaking, the Great Wall stretches across the top of the mountain, from west to east, while the Great Wall on Shitang Road has a section that turns sharply downward, in a north–south direction, only because of the towering mountains, complex terrain, dense fortresses, and numerous passes near the river, which were historically easy to defend and difficult to attack. This is a very characteristic landscape area and also the only place where mountains, valleys, rivers, lakes, and the Great Wall converge and overlap. There were chestnut trees here in ancient times. Although the garrison generals in the Ming Dynasty had rations issued by the court, they were located in deep forests and could use chestnuts to fill up their hunger when they encountered floods, torrential rains, or inconveniences in transportation. Here, there are also the Baiyihua Counter-war Red Memorial Hall, the Shitanglu Village, the Bell and Drum Tower, the Parrot Cliff, and other cultural sites.

Figure A2.

F-FT-B-13 field survey sheet. The Great Wall is the section from Gubeikou to Simatai, which is located in the Yanshan Mountain Range, with steep peaks on both sides, and the wall is built along the ridge, through which the Chaohe River flows from north to south. The clustered area is on a plain with a low degree of elevation, which was the first military defense line for northeastern Beijing and has been an important pass or postal transportation route since ancient times. It is located on a relatively flat and open terrain, with historically a large number of troops stationed here and a large scale of settlements, where the Chaoheguan, Simatai, Jijiaying, and Xinchengzi Fortresses are all located. Due to the special geographic location of Gubeikou, there are not only magnificent natural landscapes but also heavy historical and cultural deposits. Due to historical evolution, location advantages, and the change of several dynasties and military forces, Gubeikou is not only a “military town” but also an important hub for multi-ethnic settlement and multi-cultural (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism), commercial, and trade exchanges inside and outside of the Customs and Excise Department. Under the special effects of geography, military, culture, and the economy, it has created numerous scenic spots and unique human landscapes in the area.

Figure A2.