Abstract

This paper intends to delve deeply into the current understanding of the ways in which the transition from a central-based economy to an economy relying on free competition has led to changes in the big urban centers, bringing about a change in the relationships with the suburban areas. The authors take into account the high population density, the lack of space, and the elevated price of land within the big cities, which leads to urban functions migrating beyond the administrative boundaries, thus favoring the process of suburbanization. Given the context, commercial forces shift, migrating from the center to the urban peripheries or even outside them. This research is based on a comprehensive process of participative investigation (2012–2022) in Bucharest, Romania’s capital city. The research relies on field investigation, statistical and quantitative analyses and bibliographical sources. The conclusions rely primarily on the idea that political changes cannot be separated from economic, cultural and environmental ones, highlighting globalizing flows and the development of big cities. Industrial activities, strongly developed within a central-based economy, have significantly declined, which is partly compensated for by the development of the tertiary sector and, in particular, of commercial services leading to a functional reconversion of the urban peripheries and of suburban areas. The conclusions suggest that it is very important to be highly careful regarding the dilemmas and challenges ensuing from uncontrolled urban growth; therefore, several measures of urban planning should be taken with a view to achieving a better cooperation between urban stakeholders and those from the metropolitan areas so as to attain some common objectives in infrastructure in order to reach an integrated regional development.

1. Introduction. Targets

Deindustrialization, as the opposite process to industrialization, implies a decrease in the industrial capacities, which is followed by the reconversion of the laid-off labor force. In large cities, this happens mainly in the services sector (tertiarization), or it generates divergent, centrifugal migratory flows, which are often materialized through a decrease in urban population and the increase in the suburban one [1]. The border between urban and rural spaces is increasingly taking on a transitional aspect; suburbanization processes intensify, consisting of the development of peripheral urban areas to the detriment of central ones as well as the development of human and capital flows from the center toward the outskirts.

The consequences of these processes on territorial planning are manyfold: from the need to reconfigure communication ways as a result of changes in the intensity of transport flows to problems related to the demographic pressure on the technical building infrastructure in peripheral areas as a result of the rapid expansion of the built-up area or the need for administrative change in accordance with the new demographic and economic–social reality [2,3].

After 1989, once communism had fallen in Europe, the states east of the former Iron Curtain faced major economic and social transformations caused by the transition from the centralized economic system to the one based on free competition. Political and economic openness has translated to a greater or lesser extent, from state to state, through an opening to globalizing flows and a sudden shift from autarchy to integration [4]. The disappearance of political and ideological constraints has radically changed the paradigm of urban development from one based on the ideological factor to one subordinated to economic and social constraints [5] in which cultural influences caused by globalizing flows play an increasingly important role [6,7,8]. Cities, especially large ones, were the first to be marked by this evolution trend. Industrial units, mostly energy consuming and uncompetitive, ceased or reduced their activity, their place being taken over by units from the tertiary sector insufficiently developed during the communist period. The urban organization has seen profound changes, the industrial peripheries being replaced by peripheries with tertiary and especially commercial functions, which are developed most often in the vicinity of major roads and railways, thus favoring the processes of suburbanization and peri-urbanization [9,10]. Large cities have developed by incorporating peri-urban spaces; polarized spaces have become integrated spaces as the urban surface was in a continuous expansion [11].

In this global and regional context, this paper puts forth a prospective analysis of the consequences of the insertion of these phenomena in Romanian cities, casting a special look at its capital, Bucharest, as a case study for an area less addressed in the international geographic literature.

The article aims to deepen the current understanding of the ways in which the transition from a centralized economy to one based on free competition has led to changes in large urban centers by reconfiguring the development of peripheral urban spaces and the connection with suburban settlements.

The research focused on tracking the relationship between globalization, deindustrialization and tertiarization as well as the latter’s impact on urban and suburban space planning. In this context, the common characteristics, in particular, are highlighted for cities in central and eastern Europe, as well as for Romania, which are influenced by the policies of centralized development in the last five decades of the last century.

The new scientific elements that this study contributes to the global literature are oriented both toward a better understanding of the interdependence between the three phenomena (deindustrialization, tertiarization and suburbanization) in the process of developing the peripheral areas of large urban centers, of the particularities of these connections in the central and eastern European space, which inherits a territorial arrangement subordinated to various political–ideological constraints, as well as to the enrichment of the scientific literature on this subject with a representative case study for the studied phenomena and area, which uses recent data and information.

The directions followed after 1990 by the industrial units from Bucharest have been the main focus of urban researchers in the past two decades, with a series of articles and books highlighting the mutations in terms of functionality [12,13,14], urban regeneration of brownfield lands [15], population perception toward the conversion of the industrial spaces [16,17], capitalization, risks and development prospects of technical and industrial heritage [18], structural dynamics of tertiary activities in industrial parks and scenarios regarding their evolution [19], etc. The current study tries to highlight the transformations that the industrial areas from Bucharest have experienced, not strictly from a functionality point of view, but also to support new research approaches by the authors in terms of the relations established with the surroundings, respectively: the characteristics of the areas where these industrial units were activated, location opportunities for future activities, land use regulation, territorial disparities, etc.

This paper is based on the experience of an extensive participatory research process carried out over a period of ten years (between 2012 and 2022) in Bucharest, the Romanian capital. Bibliographic sources, data and statistical information were used alongside historical maps and the results of field observations and surveys. The results were compared with statistics and publications of other authors who addressed this topic.

2. Political Industrialization and Urbanization in Central and Eastern Europe1

The collapse of the communist political system highlighted the consequences of centralized planning according to the Soviet model, which in 1945 had already been implemented for over two decades in the USSR, being “exported” to states that came into its sphere of influence after World War II [21,22]. This development model was based on an economic growth caused by the hypertrophied development of the industry, especially heavy industry, the metallurgical and machine building industry, including the promotion of the working class and defense-oriented investments in an autarchic political and social framework in relation to the global constraints at the moment. Since the 1960s, the industry in western Europe and the USA had already begun to enter a restructuring process, in parallel with the large industrial investments east of the former Iron Curtain, where the center of gravity of development was transferred to high-tech branches.

The industrialization of central and eastern Europe, out of sync in relation to its western part, generated profound social and spatial mutations, which imprinted differentiated particularities on this part of the continent, the consequences of which are still felt today. The policy of industrialization generated a rapid urbanization after 1945 either by building new cities near existing industrial centers or on an empty site, as a result of new industrial investments, or the expansion of existing ones as a result of migratory flows from the rural area to new industrial units [23]. In most cases, development policies have directed new industrial investments to small towns with predominantly agricultural or commercial functions (former fairs) or even to rural settlements, which has led to their explosive population growth based on migratory flows followed by the lending of an urban status to these settlements. Thus, there appeared workers’ replicas of museum–cities, old cultural, historical or religious centers, seen at that time as “aristocratic”, in order to change their image in the minds of the inhabitants [20]. Thus, Krakow, Poland’s historical and religious center of tradition, was “doubled” by Nowa Huta, which styled itself as its “proletarian” counterpart [24].

New suburbs appeared, some even gaining a city status: Novi Beograd (1948), Nowe Tychy (1950), Novi Zagreb (1953), Halle-Neustadt (1967) [20], or in the suburban areas of Berlin [25], Prague [26], Bratislava [27], Budapest [28] or even the New Bucharest district, integrated in Bucharest in the 1950s, virtual cities within a city, working-class neighborhoods of traditional urban centers. For example, Militari district, which became part of the Romanian capital in 19502, numbered over 125,000 inhabitants and about 40,000 apartments in 1983, which is comparable to the big cities of Romania. Their characteristic was lent by a uniform and monotonous urban landscape [29], consisting of large block-type collective buildings, inspired by Soviet cities, oriented toward creating new social relationships, in which individual personality and any trace of opposition to the political system could be easily annihilated [30].

Part of another category includes the cities developed on the basis of the political–administrative function, their assigning of an administrative status preceding the setup of industrial objectives. It is the case of cities such as Târgovişte or Călăraşi, to name just two in Romania. They are urban centers that registered a strong development in the 6th and 7th decades of the previous century as a result of their becoming county capitals in 1968. This fact was one of the decisive arguments in the setup of large steel companies in these cities.

Currently, the common characteristic of all these urban centers is given by an intense degradation of the urban architectural heritage, the uniformity of the peripheries and suburbs, which require high maintenance costs, the under-sizing of green spaces and urban transport infrastructure, and prior to the 1990s, by the insufficiency of service and leisure characteristics. Thus, in terms of infrastructure, the degree of technical and urban features and the urban way of life in general, many of these cities, especially those of a small and medium category, are far from meeting the minimum European standards to which the Romanian legislation was aligned3. Wherever it manifested itself, however, the Soviet-type spatial model produced poorly developed territorial structures functionally dependent on central urban nuclei, but at the same time, it served as a framework for a real modernization of states lacking an industrial tradition and a well-developed, urban infrastructure.

3. Literature Review

Changes in the organization of the territory arising from the dynamics of urban spaces have been the subject of systematic research since the first half of the 20th century. Studies performed [31,32,33,34,35] remain a cornerstone for the expansion of American cities, together with those of Mihăilescu [36,37] and Rădulescu [38] regarding the urban–rural relationship in Romania during the interwar period.

The political and ideological clash of the 1950s, coupled with post-war reconstruction efforts, made the research in this field somewhat come to a halt only to resume in the 1960s–1970s. Among the authors who contributed at that time to the improvement of the theoretical and methodological framework regarding the connection between cities and areas of influence are [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Romanian geography rose up during that time through the studies of Cucu [48], one of the first monographic syntheses on the cities of Romania, and Iordan [49] who issued studies on the peri-urban area of the capital. The 1980s marked a transition toward quantitative approaches by introducing mathematical models of analysis [50,51,52], etc.

The second political and ideological clash of the 20th century caused by the failure of the communist ideology was reflected in a considerable expansion of the range of approaches in the field of urban and social geography. Studies have multiplied quantitatively and diversified in terms of thematic area. Urbanization and, in particular, the dynamics of the urban–rural interface, were analyzed both in terms of exurbanization [53,54,55,56], peri-urbanization [57,58], urban morphology [59,60], the cultural segregation of space [61,62,63], physiognomy [64,65], the degree of integration [66] or the improvement of the theoretical and methodological framework [67,68,69]. Studies regarding central and eastern Europe thus departed from the ideological approaches and related more to the influx of global concerns.

From a spatial point of view, the study was documented through representative case studies regarding the particularities of the urbanization and suburbanization of regional metropolises in central and eastern Europe located both west of the former Iron Curtain (in Germany—Berlin [25,70], Munich [71]; in Austria—Vienna [72]) as well as east of it (in the Czech Republic—Prague [26]; in Slovakia—Bratislava [27]; Poland—Warsaw [73], Krakow [24,74], in Hungary—Budapest [28,75]; in Romania—Bucharest [12,13,14,76], Cluj-Napoca [58], Brașov [58], Iași [3,58], Galați [77], Timișoara [78]) or in the former Soviet area (Moscow [20]).

The Romanian urban system thus began to be analyzed in terms of the dynamics of the relations between settlements [79,80,81]: the degree of connectivity [82], of industrial dynamics and unemployment [16,83,84,85,86,87], of urban image and segregation [12,88,89,90] or of the quality of urban life [91]. Given the context, the present study wishes to contribute to improving the knowledge of current processes affecting Romanian urban areas, as part of a globalized continent, with a focus on the consequences of the industrialization and urbanization of the socialist era, and on the relationship between deindustrialization, deurbanization, suburbanization and tertiarization.

4. Methodology and Dataset

The methodological approach is based on the analysis of the historical and political context of industrialization and urbanization on the one hand and deindustrialization, tertiarization and suburbanization on the other hand in Romania and its capital, Bucharest, both based on bibliographic sources and on the analysis and processing of statistical data, including satellite and photographic images but also field information.

Urbanization in Romania was analyzed in a comparative manner, in the broader context of urbanization within Europe and the former socialist states, based on documents and bibliographic sources, emphasizing both general characteristics and regional differences imposed by the economic and socio-political particularities of each country. Certain aspects were highlighted, such as the features of the Romanian urban system, the urban functional typology as well as the role of the political factor in industrialization and urbanization, the demographic flows that accompanied these processes and their consequences.

The sources of statistical data took into account the dynamics of the number of active persons employed in industry for the year of maximum industrialization in Romania (1989) but also for the subsequent censuses of 1992, 2002, 2011 and 2021, the number of people employed in services, urban industrial entrepreneurship, as well as the number and area of industrial units in the years chosen as a benchmark. Thus, deindustrialization, with Romania’s capital as a case study, was analyzed based on the ratio between the number of employees in industry in 1989 and 2021, the data and information that attest to the conversion of former industrial units into spaces with other uses, but also on satellite images which show the way of reconversion of former industrial spaces toward tertiarization. The value of land, expressed through its price at the urban district level, is also an indicator intended to quantify the trends regarding the change in the use of urban land.

The intensity of suburbanization is documented by the changes in the demographic size of the human settlements adjacent to the large urban centers with a regional polarization function compared to the urban nuclei as well as by the dynamics and functionality of the built-up area of these metropolitan centers.

At the same time, a corresponding graphic and cartographic representation of the analyzed phenomena was taken into account at the regional, national and local level.

5. Results and Discussion

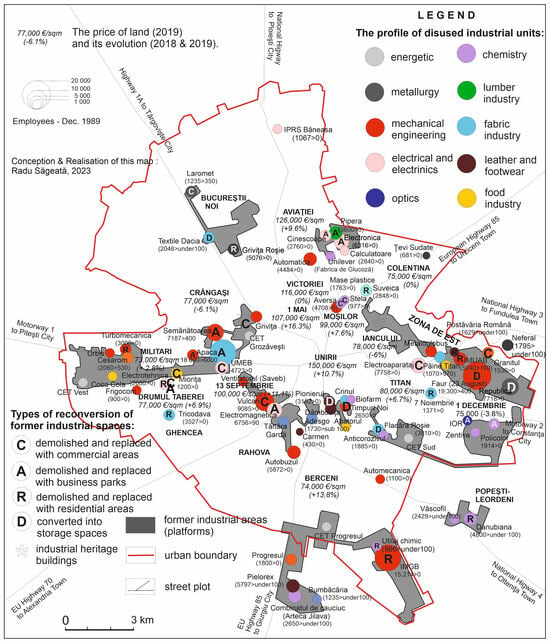

Observations in relation to functionality, characteristics of the areas where industrial units activated, location opportunities for future activities, land use regulation and territorial disparities were developed on the one hand in the Figure 1 and afterwards overlapped in a synthesis as shown in the Figure 4 with the purpose of analyzing possible scenarios in the evolution of areas still in process of transformation in Bucharest. Taking into account the realities identified in statistics and combined with the observations in the field, we can come to the following conclusions: on the place of former industrial plants and platforms have developed commercial, business centers or residential areas within private investments; new transformations that occurred in capitalism times in the former industrial areas were made entirely in the framework of private investments; public investments are missing in these areas, including in public-private partnerships; the functional profile of former industrial areas did not play a decisive role in the choice of activities types; all new investments raised the price of the areas, in general.

Figure 1.

Disused industrial units and the price of land in Bucharest City.

Starting from these findings and the different stages noticed in the transformations occurred up to this moment with an impact as well in the surrounding areas, two scenarios can be outlined: a) an harmonious organization of the areas with a balanced functionality of the activities; b) a chaotic development of activities that impact both resident and in transit population: the intensification of traffic in the area, imbalances in terms of organization and architectural harmony, negative perception of these transformations etc. From the graphic representations, we can notice a more pronounced development of different tertiary activities in some areas of Bucharest, indeed more populated, but it would be interesting to analyze in detail each of the two scenarios at micro level and see if there are models to be followed or not in further projects of transformation.

5.1. Deindustrialization, Tertiarization and Suburbanization in Romania

Romania was no exception to the developments that have been a main trait, since the 1980s, of all the states located east of the former Iron Curtain. The disappearance of inter-industrial ties, a consequence of the collapse of the centralized economic system associated with failed privatizations, corruption and incompetence at all levels of decision making has led to the disappearance or reduction in the activity of a large number of industrial units. Thus, if at the end of 1989, the final year for the centralized economy, 58% of Romania’s national income was generated by industry and only 27% was generated by services, almost three decades later, the 2021 data showed a reversal in the share of the two sectors in terms of GDP: 62.6% for the service sector and only 33.2% for industry. In Bucharest alone, out of 47 large industrial units4, only 12 still ran in 2008 and at a much-reduced capacity [92]. In most cases, the former productive units were demolished and the lands capitalized on the real estate market (Figure 1).

Thus, new residential districts, business centers, malls and supermarkets cropped up on the site of former industrial areas (Figure 2). Several former halls and industrial buildings were sold and later used for other purposes (storage, commercial services, car repairs etc.) or abandoned waiting to be demolished when the price of land becomes attractive enough.

Figure 2.

Types of conversion of former industrial spaces in Bucharest City. (Photos: R. Săgeată). (top left): AFI Cotroceni, one of the largest mall-style shopping centers in Bucharest, built on the site of the former UME Bucharest; (top right): Cora Lujerului, a shopping center built on the former site of the Mioriţa dairy factory; (down left): new residential investments built on the former site of one of the branches of the Bucharest Heavy Machinery Enterprise; (down center): Vulcan Value Center, a commercial and business center developed on the former site of the Vulcan plant industrial halls; (down right): new business buildings on top of the former “Pirotechnica” Factory (Politechnica Area).

New reconfigurations took place concerning urban spaces; the industrial units located in the urban area were demolished or relocated toward the periphery, and peripheral ones were replaced with residential districts, commercial and storage areas. For most large cities in Romania, the consequence was an increase in urban areas. The evolutions ranged significantly, varying between stagnation (Braşov) and increases of over 100% (RâmnicuVâlcea, 143%) (Table 1), which led to a considerable decrease in urban population density5. The city of Buzău registered an increase of 64.7% in urban area due to a slight demographic decrease (−0.5%). Significant increases of urban areas were also registered in Galaţi (41.92%) and Sibiu (28.38%) followed by Cluj-Napoca (13.43%), Iaşi (11.44%) and Timişoara (10, 62%). The urban area of the capital saw the largest increase (with an area of 8040 ha, namely 33.24%), which exceeded the total area of some regional metropolises such as Constanța, Iaşi, Timişoara, Craiova, Galați or Ploieşti. This increase was due to the suburbanization processes, especially at the northern, western and eastern peripheries along the major road ways to Craiova-Timişoara, Ploieşti-Braşov and Constanţa, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

The evolution of the area and population of Romania’s main cities at the last censuses.

On the other hand, deindustrialization has led to layoffs and centrifugal migrations, either regarding a return to the countryside (motivated by land laws enacted in 1991 and 1996) or people leaving to work abroad. These departures, associated with the sharp decline in natural growth, due to the elimination of pronatalist legislative constraints during the socialist period, have led to a decline in population in most urban centers of the country but predominantly in small and average-sized cities with fewer opportunities for professional retraining. Compared to the general trend, large cities have had an atypical demographic evolution, registering most of the substantial demographic increases. Thus, while the total population of Romania decreased by 1,893,213 inhabitants and the urban population decreased by 1,346,440 inhabitants6, the largest cities in Romania7 registered an increase of 340,881 inhabitants and 19,195 ha in urban area, resulting in an obvious tendency to concentrate the population within large cities. The increase was achieved through suburbanization [93], which was followed sometimes by the integration of newly developed areas into the urban area.

From an administrative point of view, however, the phenomenon is reflected at the level of suburban localities, which are closely but functionally linked to the metropolitan nuclei. The latter have seen spectacular growth both demographically and as a built-up area. Thus, while from a statistical point of view, between the last two censuses (2011–2021) some large cities recorded considerable population losses (Bucharest: −8.8%, Cluj-Napoca: −11.7%, Timișoara: −21.4%; Iași: −6.4%, Constanța: −7.1%), both the population and the number of homes have significantly grown in their neighboring towns (Table 2).

Table 2.

The suburbanization of the big cities in Romania (2011–2021).

Surplus land in the suburbs obtained as a result of deindustrialization and a drop in prices compared to those in central areas have created the premises for profitable real estate investments and services in the peripheral areas of large urban centers. Thus, new spatial polarizations were created at the urban level, generated by the new demographic flows, which put pressure on the transport and urban services infrastructure, which has developed at a slower pace, as it was managed by municipal authorities8.

Therefore, the dynamics of peripheral urban spaces result from the complementarity of the potential of the two types of local administrative structures (LAUs) which converge here: those benefitting from an advanced degree of urbanization, namely large cities, nuclei of regional and departmental (county) convergence on the one hand and the communes included in their peri-urban area on the other hand. The former, characterized by the highest population densities in the urban area and by small administrative territories, have the largest local budgets; neighboring communes, on the other hand, having limited financial resources and surplus area. The high price of land in the urban area fuels the exurbanization phenomenon by locating investments related to the city in its suburban and peri-urban areas, while administrative boundaries become purely formal. The city expands through suburbanization, sometimes beyond its administrative boundaries, the rural area thus changing status from polarized space to integrated space.

5.2. Case Study: Deindustrialization and Tertiarization through Commercial Investments. Changes in Urban Space Organization

The first malls built in Romania were raised on the site of the unfinished buildings of former food complexes, whose construction had begun in the 1980s in areas of population flows convergence, subsequently contributing to the development of their neighborhoods.

In a second stage, the policy of industrialization aimed at overlapping agro-food and public food units in the big industrial areas for workers to have swift access to them and, thus, shorten dinner-break time [17]. Since the construction of these units was abandoned in the early 1990s, foreign capital has come in, making them functional for mall-style shopping centers (Bucharest Mall, 1999; Plaza Romania, 2004; City Mall, 2005; Liberty Centre, 2008).

Bucharest Mall, the first of its kind in Romania, was built in the former industrial area of Vitan district and swiftly grew into a demographic convergence core. A second mall (Plaza Romania), opened by the same investor, is situated in the western part of the city (Drumul Taberei and Militari districts) also on the precincts of buildings left unfinished before 1990 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plaza Romania, mall-style shopping center created by converting an abandoned food complex in 1989, located between the districts of Drumul Taberei and Militari (Bucharest City) (Photo: R. Săgeată).

The placement of other commercial investments focused on either empty spaces on the outskirts of the city (Carrefour and Metro Militari, Cora Pantelimon), using the rail-and-road infrastructure existing at the outskirts of Bucharest or the sites of former industrial units later demolished (e.g., Cora Lujerului, built on the site of a dairy factory, could use Cotroceni railway station). Similarly, AFI Cotroceni Mall (the biggest in Romania), situated on the precincts of some former production shops of the Bucharest Electric Machines Plant, had the advantage of a railway infrastructure, while Megamall (in Pantelimon district) is located on the grounds of the former Electroaparataj Plant.

Commercial and business parks, i.e., Sema Park, located on the precincts of the former Semănătoarea Plant in Bucharest, Atrium Centre in Cluj-Napoca (occupies the former production units of Someşul knitware factory), Electroputere Park, Craiova (functions in the shops of the homonymous plant), Plaza Centre, Timişoara (stands on the precincts of the former slaughter-house), Korona Shopping & Entertainment Center, located in the former Fartec Plant, and Coresi Shopping Resort, which occupies the former Tractorul industrial platform (both in Braşov), or Bistriţa Retail Park (on the precincts of the former UCTA Plant), are but a few examples of the reconversion of some former industrial areas into commercial areas.

In many situations, big commercial investments were preferentially located in the administrative territories of certain communes situated in and around big cities where real estate prices were lower (the case of supermarkets such as Auchan Timişoara-South, Piteşti-Bradu, Piteşti-Găvana, Sibiu-Şelimbăr; Carrefour Brăila-Chiscani, Floreşti-Cluj, Piteşti-Bradu, Ploieşti-Blejoi, Real Oradea-Episcopiei, Selgros Bucureşti-Pantelimon, Târgu Mureş-Ernei, Dedeman Constanţa-Agigea, Roman-Cordun, Brăila-Baldovineşti (catering to both Galaţi and Brăila cities), Hornbach Baloteşti, Leroy-Merlin Bragadiru, Praktiker-Voluntari (near Bucharest) etc. Advantageous locations have led, in time, to the development of commercial parks outside Bucharest: Bǎneasa—on the DN1 highway to Ploieşti, Militari—on A1 motorway to Piteşti, and Dragonul-Roşu—on the highway to Voluntari-Urziceni. A similar commercial park is scheduled to develop outside Sibiu (European Retail Park in Şelimbăr residential area, on the highway to Bucharest), Ploieşti (Ploieşti Shopping City on the highway to Braşov), Constanţa (on the highway to Mangalia), Braşov (on the highway between Ploieşti and Bucharest), Galaţi (on the highway to Brăila), and Piteşti (on the A1 motorway to Bucharest) etc.

Another location strategy is to modernize the large commercial units built before 1989 in the center of each county seat (the so-called universal stores) and turn them into malls (Winmarkt Shopping Centre in Galaţi, Tomis Mall in Constanţa, Mureş Mall in Târgu Mureş, Moldova Shopping Centre in Iaşi, River Plaza in Râmnicu Vâlcea, Maramureş Shopping Centre in Baia Mare, Aktiv Plaza in Zalău, etc.). A typical example of such a strategy are the Unirea stores in Bucharest, which were extended and updated into what is now Unirea Shopping Center, with a Carrefour supermarket developing in its proximity. New commercial investments, making the best use of the local polarization nuclei in the center of some 2nd-tier towns, have been made in Alba Iulia (Alba Mall), Piatra Neamţ (Forum Centre), Deva (Deva Mall, Ulpia Shopping Centre), Satu Mare (Satu Mare Shopping Plaza), etc.

Student campuses are considered potential markets for commercial complexes. In Bucharest, Carrefour Orhideea, in the close vicinity of the student campuses of Grozăveşti and Regie, is a typical example of such a strategy. Iulius Mall in Cluj-Napoca, located in Gheorgheni district, near the campus of the University of Economic Sciences, or Iulius Mall in Iaşi, located near the campus of the Polytechnic University, follow the same placement logic; in other cases, entertainment is complementary to the shopping experience.

Bucharest stands out through the number and volume of new commercial investments. According to estimates [94], the city market, which concentrates about one-third of Romania’s commercial leasable area (2.9 mill. m2), is already oversaturated. At the same time, Bucharest is the only administrative unit in this country boasting an above-EU living standard average [95], which confirms the close relationship between poverty grade and the spread of commercial investments.

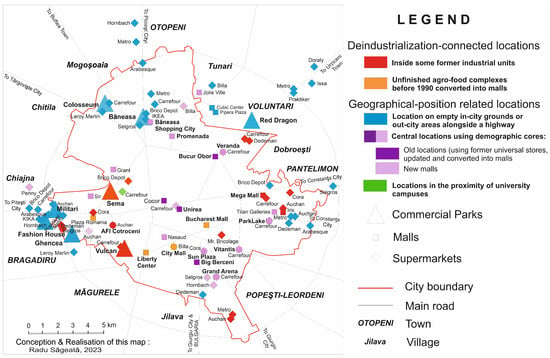

Equally, the big international retailers chose the Romanian market, opting for locations on the outskirts of the city, or around it, along the big, intensely circulated highways. Thus, large commercial areas would appear, first in the West of Bucharest (Militari Commercial Park) on the motorway to Piteşti city and, at a later date, in the North (Băneasa Commercial Park), on the motorway to Ploieşti city, and on the highway to Urziceni town and the Moldova region (Red Dragon stores). Westwards, a commercial area on the outskirts of the city started being developed in 1996, when a second Metro supermarket was opened in Romania, which was followed by Praktiker, Carrefour, KIKA and Hornbach retail networks and the Auchan and Militari Shopping City supermarkets (2009). At the northeastern periphery of Bucharest stands “Dragonul Roşu” (Red Dragon), which is part of the China Town Project (10 supermarkets on 147,570 m2 of commercial area); in the northwest, there is Colosseum Retail Park (2011) on the Bucharest-Târgovişte highway; in the southwest, we have Ghencea Shopping Centre (2013); while in the southeast, there is Vulcan Value Center (2014) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A typology of commercial investments localizations in Bucharest City.

Within Bucharest, new malls opened on dismantled industrial areas [96] and became centers of demographic convergence: City Mall was the first investment (2005) in the south of the city, next came Liberty Centre (2008), AFI Cotroceni (2009), Sun Plaza (2010), Promenada Mall (2013) and Megamall (2015). In 2016, Park Lake Plaza was commissioned on the site of a former sports and leisure activity base in Titan Park and the Veranda Shopping Centre was built on the precincts of a former plastics factory both in the northeast of the city. Thus, the density of modern commercial locations in Bucharest exceeded 490 m2/inhabitant, which was much above the national average (103.6 m2/1000 inhabitants [97].

And yet, new investments are on the way (i.e., Victoria City Lifestyle Retail Center in Bucureştii-Noi District, in the northwest of Bucharest), while other investments have been abandoned since 1990. It is the case of Dâmboviţa Centre, lying on the banks of the Dâmboviţa River, on the site of a former turf; its construction started in early 1986, and it was initially intended to host the National History Museum of the Socialist Republic of Romania. Abandoned after 1989, the building, in an advanced stage of construction, was put forward for various purposes, first as the Romanian Broadcasting Center (Radio House) (1992–2008) and then sold to an Israeli company to develop a commercial and business center. After being sectioned and having its central structure demolished, it was abandoned yet again (2009) because of the economic crisis [98].

6. Conclusions

Romania and its capital, Bucharest, represent a case study for a comprehensive approach of three complex processes and phenomena showing a solid cause–effect relationship: deindustrialization, tertiarization and suburbanization. When these occur on a very dynamic (but not necessarily positive) economic, legislative and demographic background, the effects are more complicated, even tangled, and the results consist of many and varying new shapes and trends of urban development. In central and eastern Europe, the big moment of change was in 1989. Since then, and, dare we say, until now, the consequences of the oversized, politically coordinated industrialization, yet uncorrelated with the potential of the cities’ areas of influence, were materialized and generated somewhat severe imbalances between the urban nuclei and their peri-urban areas. On the other hand, the transition from a central-based economy to an economy relying on free competition generated imbalances in the provision of services between the central urban nuclei and the large residential districts located on the periphery, which were hastily built as a reflection of industrialization. Furthermore, the collapse of ideological barriers after 1989 put the cities east of the former Iron Curtain back on a natural development trajectory in relation to the potential and constraints of economic factors relying on free competition.

Three major issues had the most impact on Romanian towns: the post-1990 industrial restructuring, Romania’ accession to the EU (2007) and the financial crisis of 2007. The transition from the pre-1989 industrial town type to the early 21th century one, consisting of well-represented services, was complex and long-lasting for Romania on the one hand while also having social implications and high costs on the other. The post-1989 economic and urban crisis caused the functional destructuring of towns and increased the future urban functional model based on the future services town. This was reflected in many cases through the process of deindustrialization, as residential districts or service areas, especially commercial ones, were developed on the site of former industrial units with a view to absorb the services deficit in peripheral urban areas.

Romania and its capital, Bucharest, are typical cases for such developments. While the total population of the country together with the urban population decreased considerably, the population and the urban area of the big cities increased. This growth was achieved through the development of peripheral urban areas and suburban spaces and the replacement of former industrial units with residential and commercial areas. Thus, the functional urban areas were reconfigured, as were the directions and intensities of the flows from the urban spaces as well as between them and the suburban areas. The issue is whether the case study teaches us—academics and actors in urban planning—how to avoid future errors and how to solve or fix the current imbalances which have appeared and developed within the urban dynamic in Romania, especially in large towns and in Bucharest City in the most visible way. For the future, the research should be focused on different categories of towns approached as study cases, thus scientifically sustaining any future urban planning actions.

The article highlights the changes that have taken place at the level of the spaces adjacent to the large urban centers in Romania, and particularly at the level of its capital, Bucharest.

While the neighboring localities closely linked functionally to the metropolitan centers recorded spectacular increases in population and built-up area, in the large urban nuclei, the population dropped in numbers. The flows of population and capital from the center to the outskirts and to suburban areas were thus intensified as did, implicitly, the pressure that traffic exerted on the communication ways, which often turned out to be undersized.

At the same time, there were major changes at the level of urban functionality, which were stimulated on the one hand by the bankruptcy of large industrial units developed hypertrophically during the centralized economy, and, on the other hand, by the lower price of land in peripheral and suburban areas. These changes came as a result of the migration of residential and service functions toward the outskirts and the suburbs, taking the place of former industrial or agricultural areas.

The communication ways and the large residential areas developed during the centralized economy era against the backdrop of industrialization and migrations from the countryside were also attractive elements for the redirection of large investments in the tertiary sector and of large commercial centers in particular.

These phenomena, a result of globalizing processes, are not characteristic of the big cities in Romania and, specifically, Bucharest. Nevertheless, they have registered a greater intensity in this country due to the more self-sufficient aspect of its economy during the communist era and the sudden, post-1989 open attitude, which generated an avalanche of economic and social consequences.

The results obtained in this study are particularly valuable and represent the basis of future micro-level research of the impact that deindustrialization has brought to the respective areas. The outlining of similarities and contrasting situations in various case studies and other findings can be useful in the differentiation of more targeted types of tertiarization in Bucharest City. However, this type of investigation requires a more complex analysis at the level of each area, application of new research methods including from the qualitative ones, and intended to be study object of future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and T.H.; methodology, R.S. and B.M.; software, R.S.; validation, A.-L.C., T.H. and I.G.; formal analysis, R.S. and B.M.; investigation, R.S., A.-L.C. and I.G., resources, R.S., A.-L.C. and T.H.; data curation, R.S., A.-L.C., and I.G., writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review & editing, R.S. and A.-L.C., visualization, R.S., A.-L.C., T.H. and I.G., supervision, R.S., A.-L.C., T.H. and I.G., project administration, R.S., funding acquisition, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was conducted under the research plan of the Romanian Academy “Geographical studies on the evolution of population in Romania after 1989” and under the joint academic research project “Cross-border Cooperation in the Middle and Lower Danube Basin. Geographical Studies with focus on Hungarian and Romanian Danubian Cities”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We include in central Europe the geopolitical ensemble composed of Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Austria and Switzerland (central–western Europe), and Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, Belarus, Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova and Romania (central–eastern Europe), and in eastern Europe, the European sector of the Russian Federation [20]. |

| 2 | Here, the construction of the apartment buildings started in 1962 as a response to the construction of the industrial platform to the west of the Romanian Capital. |

| 3 | The Law on the approval of the National Territory Improvement Plan no. 351 of 6 July 2001. Section IV: The Network of localities, Official Monitor, XIII, 408 of 24 July 2001. |

| 4 | The majority of production units were grouped into five industrial platforms. |

| 5 | In the case of Râmnicu Vâlcea municipality, urban population density fell from 5567.1 inhabitants/km2 in 2007 to 2432.1 inhabitants/km2 in 2017. |

| 6 | From 21,537,563 inhabitants to 19,644,350 inhabitants, from 11,877,695 inhabitants, to 10,531,255 respectively (data for the 1 July 2007 and 1 July 2017 interval). For the same interval, the degree of urbanization dropped from 55.1% to 53.6%. Source: Romanian Statistical Yearbooks 2008 and 2018, National Institute of Statistics, Bucharest. |

| 7 | These accounted for almost half (49.5%) of Romania’s urban population. |

| 8 | In many cases, cooperation between urban municipalities and those of suburban communes is lacking, despite their integration into homogeneous territorial structures such as metropolitan areas. |

References

- Lever, W.-F. Deindustrialization and the reality of the post-industrial city. Urban Stud. 1991, 28, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H.; Abrams, J. Amenity migration: Diverse conceptualization of drives, socioeconomic dimensions, and emerging challenges. Geojournal 2011, 76, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntele, I. Urbanisation et countreurbanisation dans l’Europe d’après-guerre [Urbanisation and counterurbanisation in post-war Europe]. Rev. Roum. De Géographie Rom. J. Geogr. 2009, 53, 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. The Global City; Princeton University Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Tokyo, Japan; Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Musterd, S.; Marcińzak, S.; van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. Increasing separation between poor and rich. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 1062–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S.; Creţan, R.; Ianăş, A.; Satmari, A. The Romanian Post-Socialist City: Urban Renewal and Gentrification; West University Publishing House: Timișoara, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ham, M.; Tammaru, T. New perspectives on ethnic segregation over time and space. A domains approach. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucu, I.-S. Urban identities in music geographies: A continental-scale approach. Territ. Identity Dev. 2018, 3, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.-P., Jr. Towards a typology of urban-rural relationships. Prof. Geogr. 1971, 23, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S.-M. Urban policy mobilities, argumentation and the case of the model city. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; de Vries, J.; Tasan-Kok, T. Planning cultures and histories: Influences on the evolution of planning system and spatial development patterns. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2127–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelcea, L. Bucureştiul Postindustrial. Memorie, Dezindustrializare şi Regenerare Urbană [Post-Industrial Bucharest. Memory, Deindustrialization and Urban Regeneration]; Polirom Publishing House: Iași, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cepoiu, A.-L. Rolul Activităților Industriale în Dezvoltarea Așezărilor din Spațiul Metropolitan al Bucureștilor [The Role of Industrial Activities in the Development of Settlements in the Metropolitan Area of Bucharest]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Săgeată, R. The Urban Systems in the Age of Globalizaton. Geographical Studies with Focus on Romania; LAP Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Paraschiv, M.; Nazarie, R. Regenerarea urbană a siturilor de tip brownfield. Studiu de caz: Zonele industriale din sectorul III, Municipiul București [Urban regeneration of brownfield land. Case Study: Industrial areas in sector III, Bucharest Municipality]. Analele Asoc. Prof. A Geogr. Din România 2010, 1, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Saghin, I.; Iojă, C.; Gavrilidiș, A.; Cercleux, L.; Vânău, G. Perception of the Industrial Areas Conversion in Romanian Cities—Indicator of Human Settlements Sustainability, 48th ISOCARP Congress, 2–3. 2012. Available online: https://www.isocarp.net/Data/case_studies/2120.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Săgeată, R. Commercial services and urban space reconversion in Romania (1990–2007). Acta Geogr. Slov. 2020, 60, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercleux, A.-L.; Merciu, F.-C. Patrimoniul tehnic și industrial în România. Valorificare, riscuri și perspective de dezvoltare [Technical and industrial heritage in Romania. Capitalization, risks and prospects of development]. Analele Asoc. Prof. A Geogr. Din România 2010, 1, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cercleux, A.-L.; Peptenatu, D.; Merciu, F.-C. Structural dynamics of tertiary activities in industrial parks in Bucharest, Romania. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2015, 55, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R. Fluctuating geographical position within geopolitical and historical context. Case Study: Romania. Geogr. Pannonica 2020, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourcher, M. Fragments d’Europe. Atlas de l’Europe Médiane et Orientale; Fragments of Europe. Atlas of Middle and Eastern Europe: Fayard, Paris, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Churkina, N.; Zaverskiy, S. Challenges of Strong Concentration in Urbanization: The Case of Moscow in Russia. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R. Structurile urbane de tip socialist—O individualitategeografică? [Socialist urban structures—A geographical individuality?] Analele Univ. Din Oradea Geogr. 2003, XII, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Romańczyk, K.-M. Krakow—The City profile revisited. Cities 2018, 73, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, W.; Schwedler, H.-U. Urban Planning and Cultural Inclusion. Lessons from Belfast and Berlin; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2001; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9780230524064 (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Sýkora, L. Changes in the Internal Spatial Structure of Post-Communist Prague. GeoJurnal 1999, 49, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavík, V.; Grác, R.; Klobučník, K. Development of Suburbanizations of Slovakia on the Example of the Bratislava Region. In Urban Regions as Engines of Development; Polish Academy of Science: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; pp. 35–58. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265847165_Development_of_Suburbanizations_of_Slovakia_on_the_Example_of_the_Bratislava_Region (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Berényi, I. Transformation of the Urban Structure of Budapest. GeoJournal 1994, 32, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigorea-Oprea, L.; Popa, N. Industrial brownfields: An unsolved problem in post-socialist cities. A comparison between two mono industrial cities: Reşiţa (Romania) and Pančevo (Serbia). Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 2719–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săgeată, R. Politics and its Impact on the Urban Physiognomy in Central and Eastern Europe: A Case Study of Bucharest. Cent. Eur. J. Geogr. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 1, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, E.-W. The Growth of the city. An Introduction to a Research Project. In The Trends of Population. Publication of the American Sociological Society; American Sociological Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1925; Volume XVIII, pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, H. One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago, 1st ed.; Beard Books & Franklin Classics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C.H.; Ullman, E.-D. The nature of the cities. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1945, 242, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, E.-W. The Growth of the city. An Introduction to a Research Project. In Urban Ecology. An International Perspective on the Interaction between Humans and Nature; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, H. One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago, 2nd ed.; Beard Books & Franklin Classics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, V. Bucureştii din punct de vedere antropogeografic şi etnografic [Bucharest, considered from the antropo- geographical and etnographical point of view]. Anu. De Geogr. Şi Antropogeografie 1915, 4, 145–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, V. Oraşul ca fenomen antropogeografic [The town as an antropogeographical phenomenon]. Cercet. Şi Stud. Geogr. 1937–1938, I, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rădulescu, N.-A. Zonele de aprovizionare ale câtorva oraşe din sudul României [Supply areas of several cities in southern Romania]. Rev. Geogr. 1944, I, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, J.-B.; Chabot, G. Traité de Géographie Urbaine [Treaty of Urban Geography]; Librairie Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, W. Location and Land Use. Toward a General Theory of Land Rent; Harvard University Press: Harvard, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, R.-E. City and Region. A Geographic Interpretation; Routledge: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M.-H.; Koln, C.-F. Readings in Urban Geography; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Choley, R.-J.; Haggett, P. (Eds.) Models in Geography; Methuen: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Badcock, B.-A. A preliminary note on the study of intra-urban physiognomy. Prof. Geogr. 1970, 22, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abler, R.; Adams, J.; Gould, P. Spatial Organization; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Soppelsa, J. Des distorsionsrécentes de la théorie des lieuxcentraux. Propositions pour une nouvelle approche de la notion de hiérarchieurbaine [Recent distorsions of central place theory. Proposal for a new deepening of the notion of urban hierarchy]. Bull. De L’association Des Géographes Français 1977, 439–440, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastié, J.; Dézert, B. L’espace Urbain [Urban Space]; Masson: Paris, France; New York, NY, USA; Barcelona, Spain; Milan, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cucu, V. Oraşele României [The Cities of Romania]; Scientific Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Iordan, I. Zona Periurbană a Bucureştilor [The Periurban Area of Bucharest]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ungureanu, A. Oraşele din Moldova. Studiu de Geografie Economică [Towns in Moldavia. Study of Economic Geography]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ronnais, P. Urbanization in Romania. A Geography of Social and Economic Change Since Independence; The Economic Research Institute, Stockholm School of Economics: Stockholm, Sweden, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I. Oraşele şi Organizarea Spaţiului Geografic. Studiu de Geografie Economic Asuprat Eritoriului României [Towns and the Organization of the Geographical Space. Studies of Economic Geography on Romania’s Territory]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, A.-C.; Dueker, K.-J. The exurbanization of America and its planning policy implications. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 1990, 9, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, A.-X. Exurbanization and Aldo Leopold’s human-land community. In The Planner’s Guide to Natural Resource Conservation; Esparza, A.-X., McPherson, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, I. Modificările Mediului în aria Metropolitană a Municipiului București [Environmental Changes in the Metropolitan Area of the City of Bucharest]; Romanian Academy Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Majewska, A.; Malgorzata, D.; Krupowicz, W. Urbanization Chaos of Suburban Small Cities in Poland: “Tetris Development”. Land 2020, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Fetner, C.; Piorr, A.; Nielsen-Thomas, S. Peri-urbanization and multifunctional adaptation of agriculture around Copenhagen. Dan. J. Geogr. 2011, 111, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghia, M. The peri-urbanisation effect: Emerging functional spatial patterns in Romania. Case-study for 4 major cities: Brașov, Cluj-Napoca, Iași and Timișoara. J. Urban Landsc. Plan. 2021, 6, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gospodini, A. Urban morphology and place identity in European cities: Built heritage and Innovative design. J. Urban Des. 2004, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, G.; Gilliland, J. Mapping urban morphology: A classification scheme for interpreting contributions to the study of urban form. Urban Morphol. 2006, 10, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warf, B. Global cities, cosmopolitanism and geographies of tolerance. Urban Geogr. 2015, 36, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieling, J.; Othengrafen, F. Planning Culture—A Concept to Explain the Evolution of Planning Policies and Processes in Europe? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 2133–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezin, E.; Moizeau, F. Cultural dynamics, social mobility and urban segregation. J. Urban Econ. 2017, 99, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudny, W. The study of the landscape physiognomy of urban areas—The methodology development. Methods Landsc. Res. Diss. Comm. Cult. Landsc. 2008, 8, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Koter, M.; Kulesza, M. The study of urban form in Poland. Urban Morphol. 2010, 14, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann, A. Is the “Central german metropolitan region” spatially integrated? An Empirical assessment of commuting relations. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 1853–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacşu, M.-C. Oraşul Sub Lupă. Concepte Urbane. Abordare Geografică [The City Under the Magnifying Glass. Urban Concepts. Geographic Approach]; Pro-Universitaria Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Storper, M.; Scott, A.-J. Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 1114–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. Creative destruction in urban planning procedures: The language of “renewal” and “exploitation”. Urban Geogr. 2019, 40, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thierfelder, H.; Kabisch, N. Viewpoint Berlin: Strategic urban development in Berlin—Challenges for future urban green space development. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 62, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, F.; Dang, K.-A.; Hölzl, M.; Pedrazzoli, A.; Schmidkunz, M.; Wang, J.; Thierstein, A. Regional Urbanization through Accessibility?—The “Zweite Stammstrecke” Express Rail Project in Munich. Urban Sci. 2020, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, J.; Gruber, E.; Görgl, P.; Hemetsberger, M. Wie Wien wächst: Monitoring aktueller Trends hinsichtlichBevölkerungs- und Siedlungsentwicklung in der Stadtregion Wien [How Vienna Grows: Monitoring of Current Trends of Population and Settlements Dynamics in the Vienna Urban Region]. Raumforsch. Und Raumordn. Spat. Res. Plan. 2018, 76, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, J. Spatial context of urbanization: Landscape pattern and changes between 1950 and 1990 in the Warsaw metropolitan area, Poland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 93, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurek, S.; Wójłowicz, M.; Gałka, J. The changing role of migration and natural increase in suburban population growth: The case of non-capital post-socialist city (The Krakow Metropolitan Area, Poland). Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2015, 23, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, Z.; Szigeti, C.; Harangozó, G. Assessing the sustainability of urbanization at the sub-national level: The Ecological Footprint and Biocapacity accounts of the Budapest Metropolitan Region, Hungary. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guran-Nica, L.; Sofer, M. Migration Dynamics in Romania and the Counter-Urbanisation Process: A Case Study of Bucharestʼs Rural-Urban Fringe. In Translocal Ruralism. Mobility and Connectivity in European Rural Spaces; Hedberg, C., do Como, R.-M., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Săgeată, R.; Buza, M. Die Industrieentwicklung und das Organisieren des städtischen Raumes im rumänischen Sektor der Unteren Donau. Der Studienfall: Galaţi [Industrial development and urban space organisation in the Romanian sector of the Danube. Case study: Galaţi City]. Rev. Roum. De Géographie Rom. J. Geogr. 2014, 58, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Marian-Potra, A.-C.; Ișfănescu-Ivan, R.; Ancuța, C.-A.; Pavel, S. Temporary Uses of Urban Brownfields for Creative Activities in a Post-Socialist City. Case-Study: Timișoara, Romania. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoş, I. Sisteme Teritoriale. O Abordare Geografică [Territorial Systems. A Geographical Approach]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I. Dinamica Urbană. Aplicaţii la Oraşul şi Sistemul Urban Românesc [Urban Dynamics. Applications on the City and the Romanian Urban System]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I.; Heller, W. Spaţiu, Economie şi Sisteme de aşezări [Space, Economy and Settlements Systems]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tălângă, C. Transporturile şi Sistemele de Aşezări din România [Transportation and the Settlement Systems in Romania]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Groza, O. Les Territoires de L’industrie [The Territories of the Industry]; Didactic & Pedagogical Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, C. Industria Românească în Secolul XX. Analiză Geografică [Romanian Industry in the 20th Century. A Geographical Analysis]; Oscar Print Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nica-Guran, L. Investiţii Străine Directe. Dezvoltarea Sistemului de Aşezări din România [Foreign Direct Investments and the Development of the Settlements in Romania]; Technic Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, B. Oraşele Monoindustriale din România între Industrializare forţată şi Declin Economic, [One-Industry Town in Romania between Forced Industrialization and Economic Decline]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mocanu, I. Şomajul din România. Dinamică şi Diferenţieri Geografice [Unemployment in Romania. Dynamics and Geographical Differentiation]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Neacşu, M.-C. Imaginea Urbană, Element Esenţial în Organizarea Spaţiului [The Urban Image, an Essential Element in the Organization of the Space]; Pro-Universitaria Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gavriş, A. Mari Habitate Urbane în Bucureşti [Large Urban Habitats in Bucharest-City]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mionel, V. Segregarea Urbană. Separaţi dar Împreună [Urban Segregation. Separate but Together]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nae, M. Geografia Calităţii vieţii Urbane. Metode de Analiză [Geography of Urban Quality of Life. Methods of Analysis]; University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Giurescu, C.-C. Istoria Bucureştilor [The History of Bucharest], 3rd ed.; Vremea Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, I. Suburbanismul, ca Fenomen Geografic în România [Suburbanism, as a Geographical Phenomenon in Romania]; Meronia Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NAI Romania. Piaţa Spaţiilor Comerciale. Studiu de Piaţă Imobiliară 2014. Tendinţe 2015 [The Market of Commercial Areas. A Housing-Market Study 2014. Trends 2015]; NAI Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; Available online: http://www.nairomania.ro/images/publicatii/doc_34_53.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2017).

- Isărescu, M. Opening Address at the Scientific Gathering on “Romania in the European Union”, Organized by the Romanian Academy. 2017. Available online: http://www.storage.dns.mpinteractiv.ro/media/pdf (accessed on 20 July 2019).

- Mirea, D.-A. Industrial landscape—A landscape in transition in the Municipality Area of Bucharest. Geogr. Phorum—Geogr. Stud. Environ. Prot. Res. 2011, X, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman & Wakefield. România pe Ultimul Loc în Europa la Densitatea de Spaţiicomerciale [Romania at the Bottom of Commercial Area Density in Europe]; DC News: Bucharest, Romania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, I.; Kucsicsa, G.; Mitrică, B. Assessing spatio-temporal dynamics of urban sprawl in the Bucharest Metropolitan Area over the last century. In Land Use/Cover Changes in Selected Regions in the World; International Geographical Union, Charles University: Prague, Czech Republic, 2015; pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).