Rural China Staggering towards the Digital Era: Evolution and Restructuring

Abstract

1. Introdugction

- (a)

- What are the development stages, major changes in rural society in China, and key policy frameworks underpinning the changes and evolution of rural China?

- (b)

- What are the latest policy frameworks and development trends of rural digital development in China?

- (c)

- What are the evolving dynamics of rural China across different development stages in terms of policy contexts, governance regimes, villagers’ identity and mobility, socio-economic morphologies, linkages with urban counterparts; and how the underpinning mechanism and driving factors of rural China’s evolution would transform embracing the digital era?

- (d)

- What are the potential (multi-faceted) restructuring of rural China driven by digital transformation?

2. Research Methodology

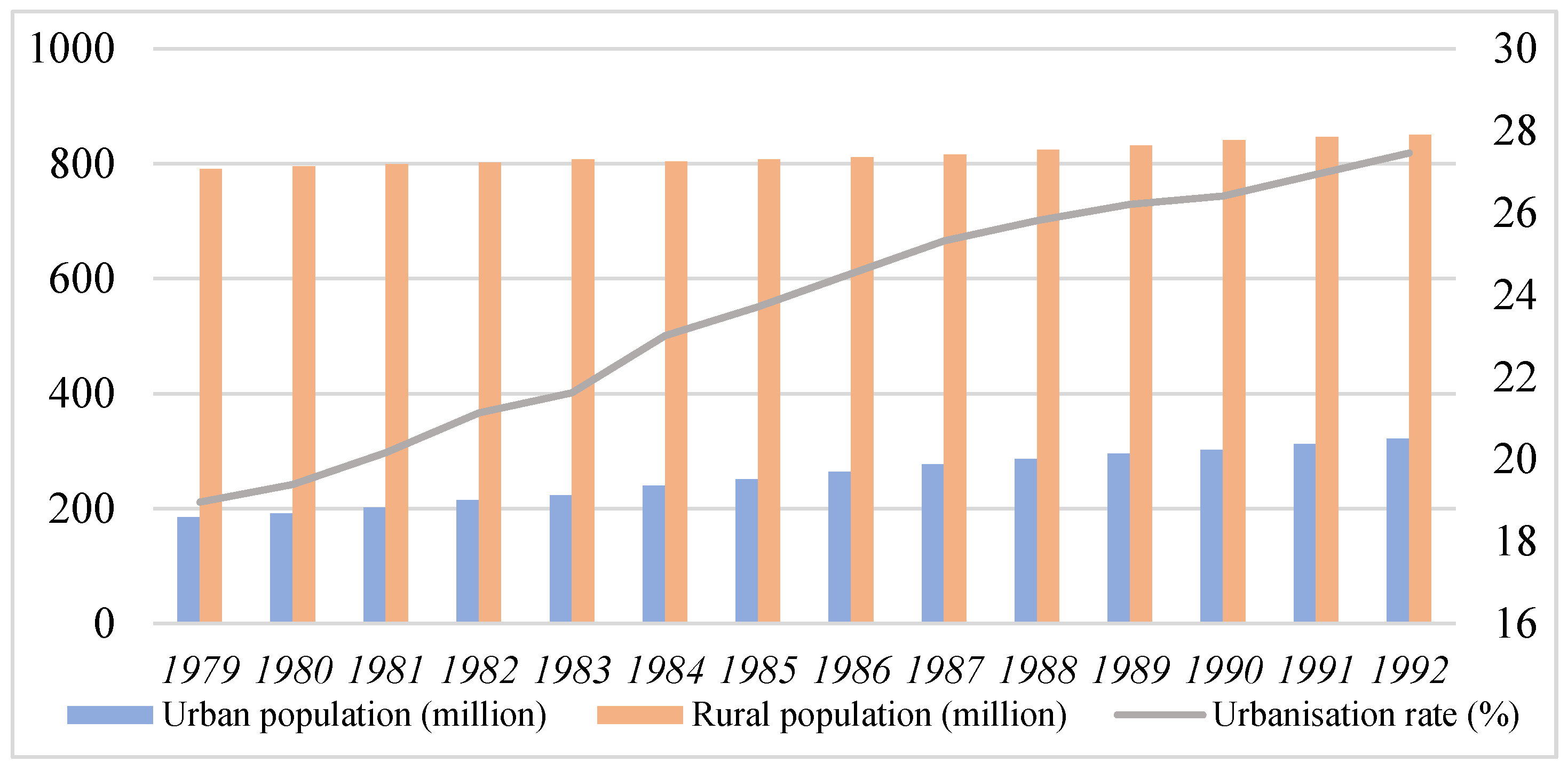

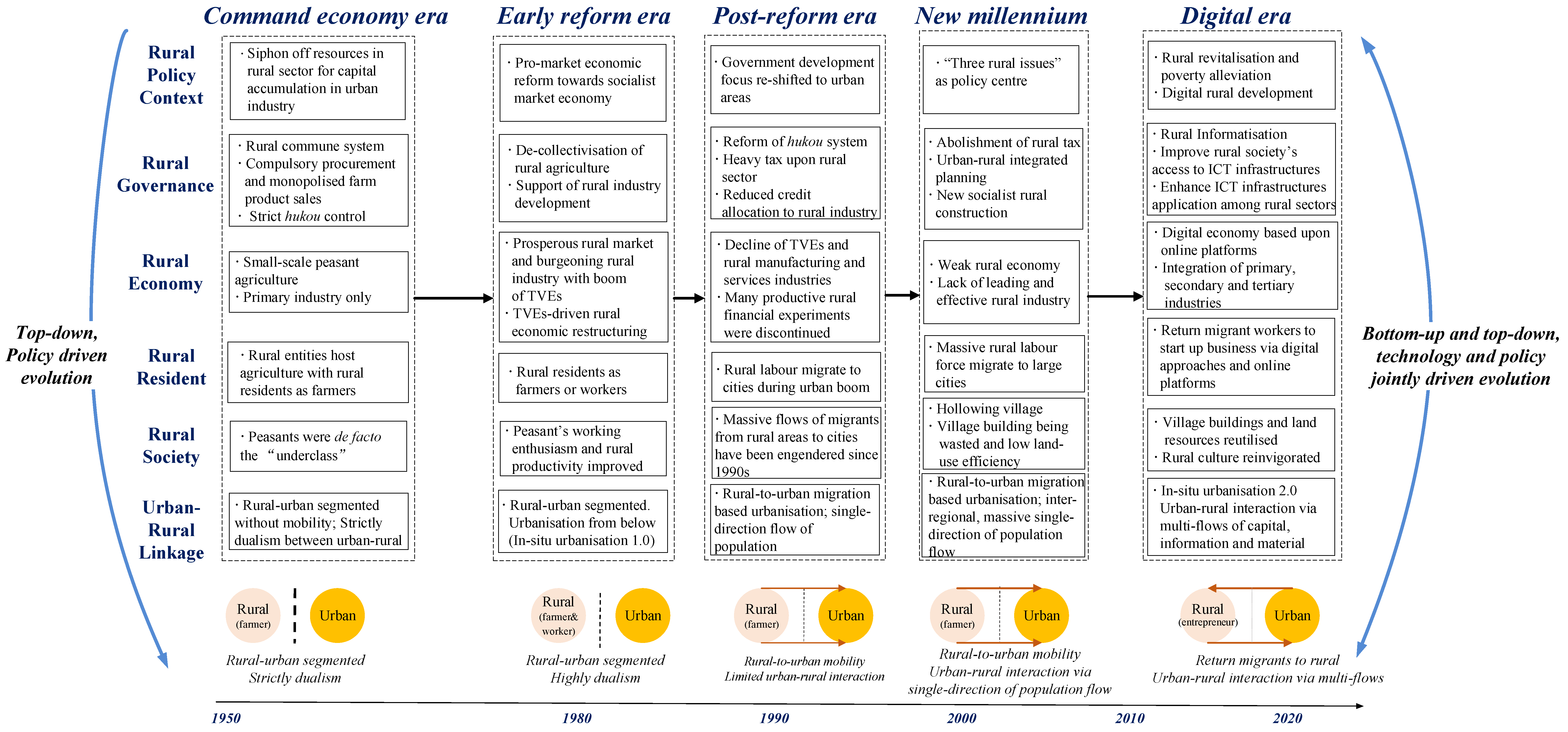

3. Understanding the Tale of Rural China at Different Development Stages

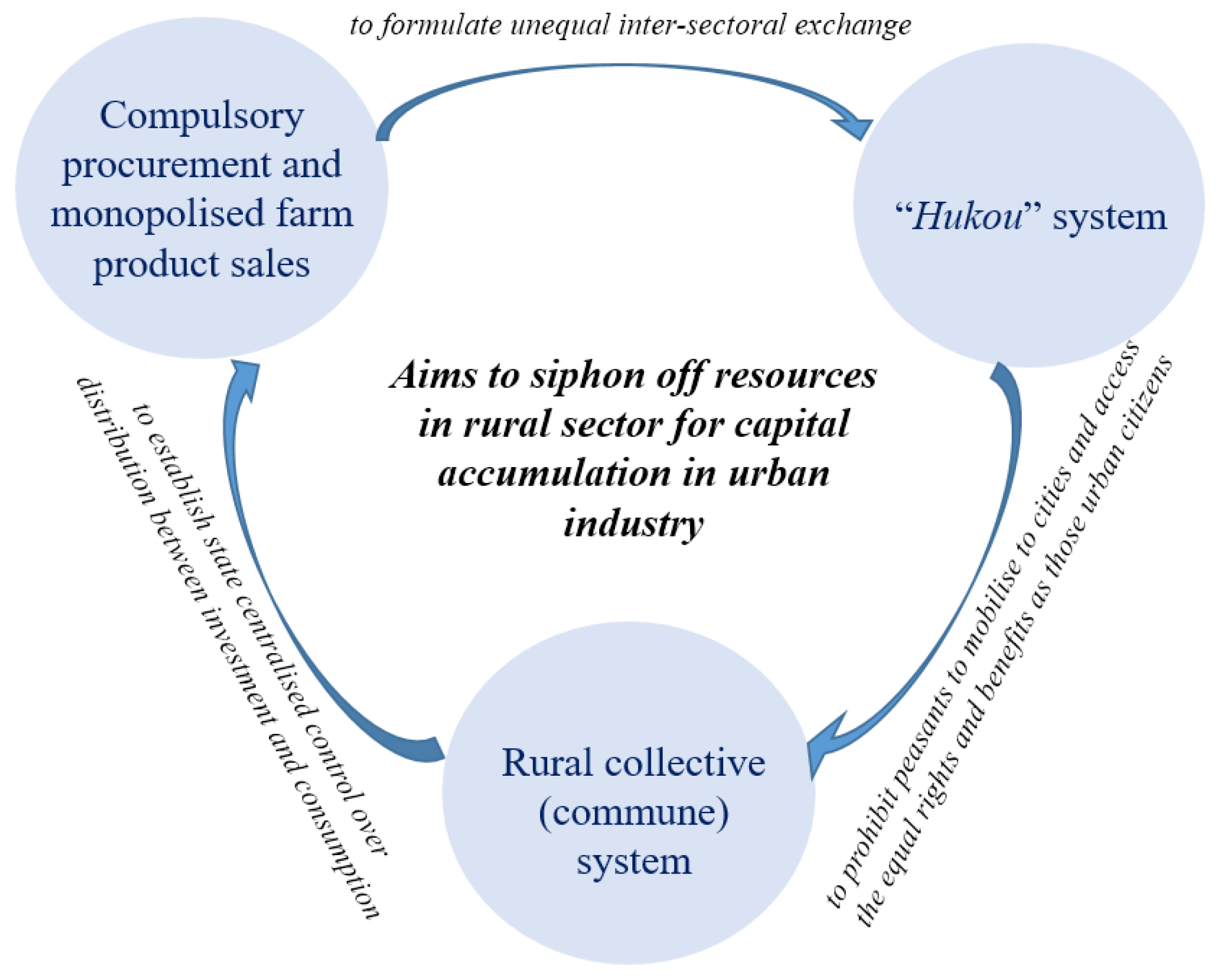

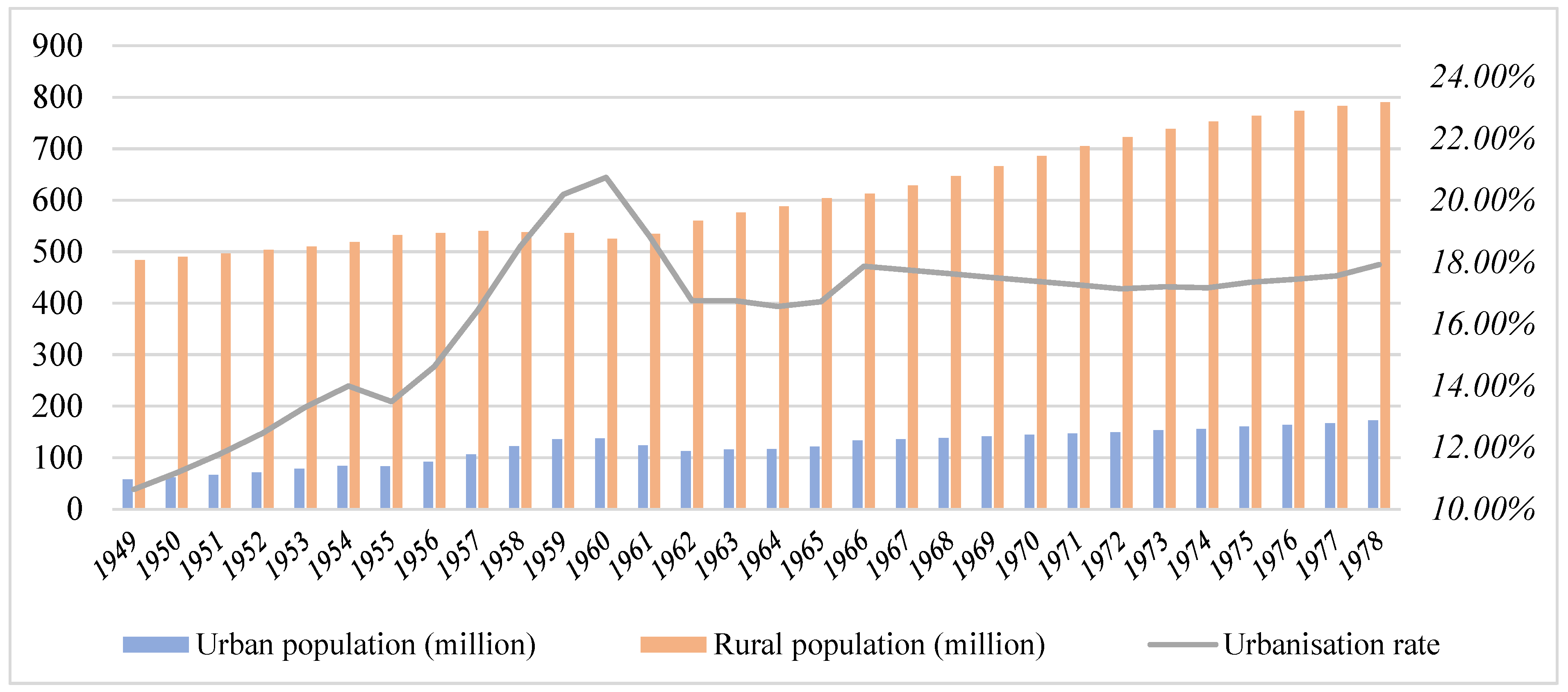

3.1. Rural Society in the Command Economy (1949–1977)

3.2. Rural China Amidst the Reform Era of the 1980s

- De-collectivisation of rural agriculture

- Township and Village Enterprise (TVE) development and rural industrialisation

3.3. Rural China Suffered an Unfavourable Policy Environment in the 1990s

3.4. Rural China as Policy Centre Issue in the New Millennium

- The “No.1 Central Document”, centred on rural issues, published by the Chinese central government in 2004, the first after almost twenty years’ absence since 1986, addressed income improvement and poverty alleviation among rural villagers [44].

- The pursuit of a “Harmonious Society” (hexie shehui) was introduced and this conception emphasised the coordinated and integrated development of the urban and rural sectors [45].

- The “New Socialist Rural Construction Programme”, issued in the 11th National Economic and Social Development Plan (2006–2010), aimed to modernise the Chinese countryside and appreciated rural villages as a potential place to stimulate economic growth, under the rhetoric of narrowing urban–rural disparities [46].

- The rural tax reform was initiated to phase out the agricultural tax, and the agricultural tax was officially abolished in 2006, which was a major relief to peasants’ tax burden in rural China (it used to be eight percent of a peasant’s agricultural output) [47]. Additionally, the reinforcement of rural minimum living security system, the strengthening of rural welfare such as medical and educational systems, and the promotion of many transfer policies also helped to accelerate poverty reduction in rural China.

- Urban-rural integrated planning: the conventional urban-centred planning paradigm was reformed by the 2008 Urban and Rural Planning Act, which demarcated a watershed as it was the first time in the PRC’s history that rural territories were included in the master planning. Such a reform indicated that the state planning power has been extended into the largely “unplanned” rural areas [31].

- Transformation of rural population: in order to absorb the rural surplus population, the 2010 “No.1 Central Document” emphasised the reform of the “hukou” system and the important role of townships in receiving surplus rural population, to encourage and guarantee the rural transforming population to settle in small towns and enjoy the same social benefits of local township residents [48].

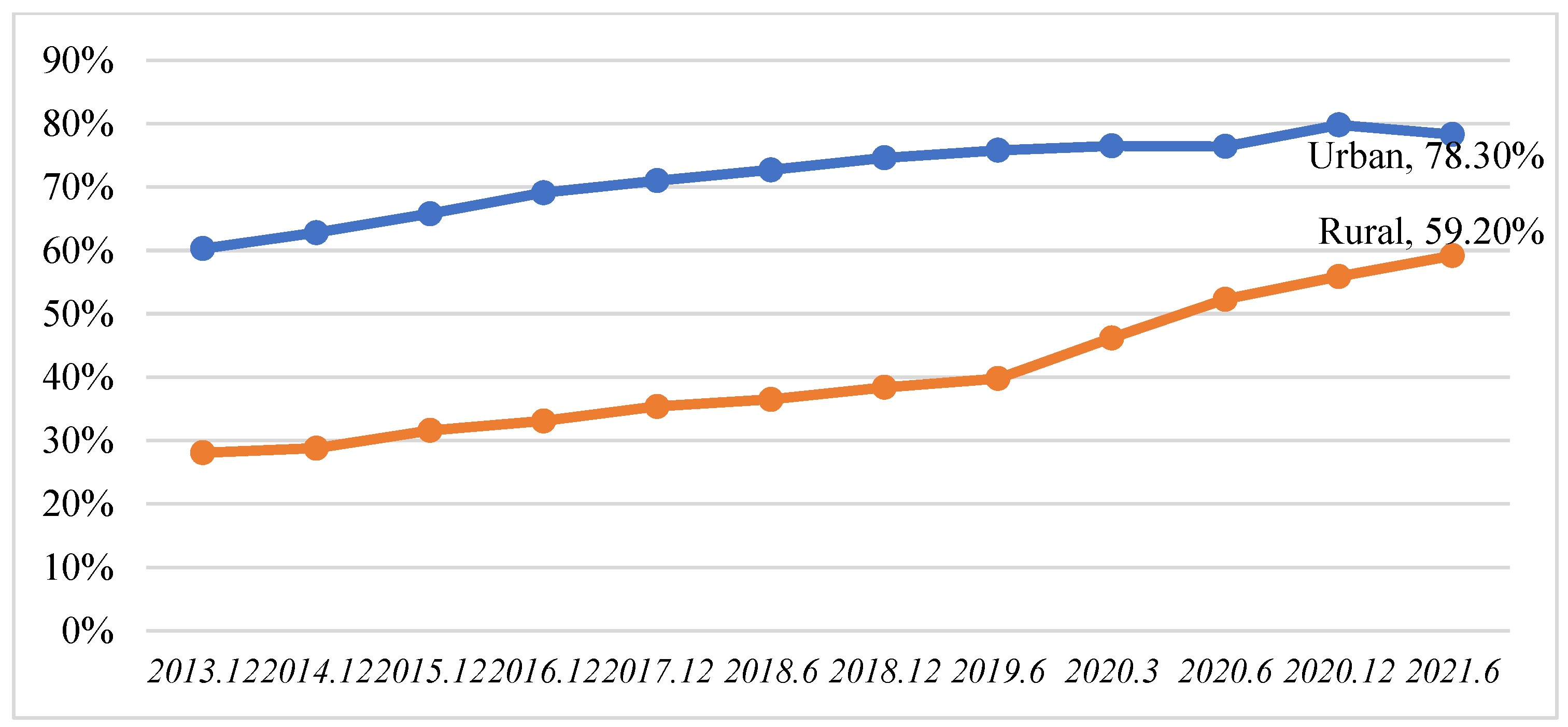

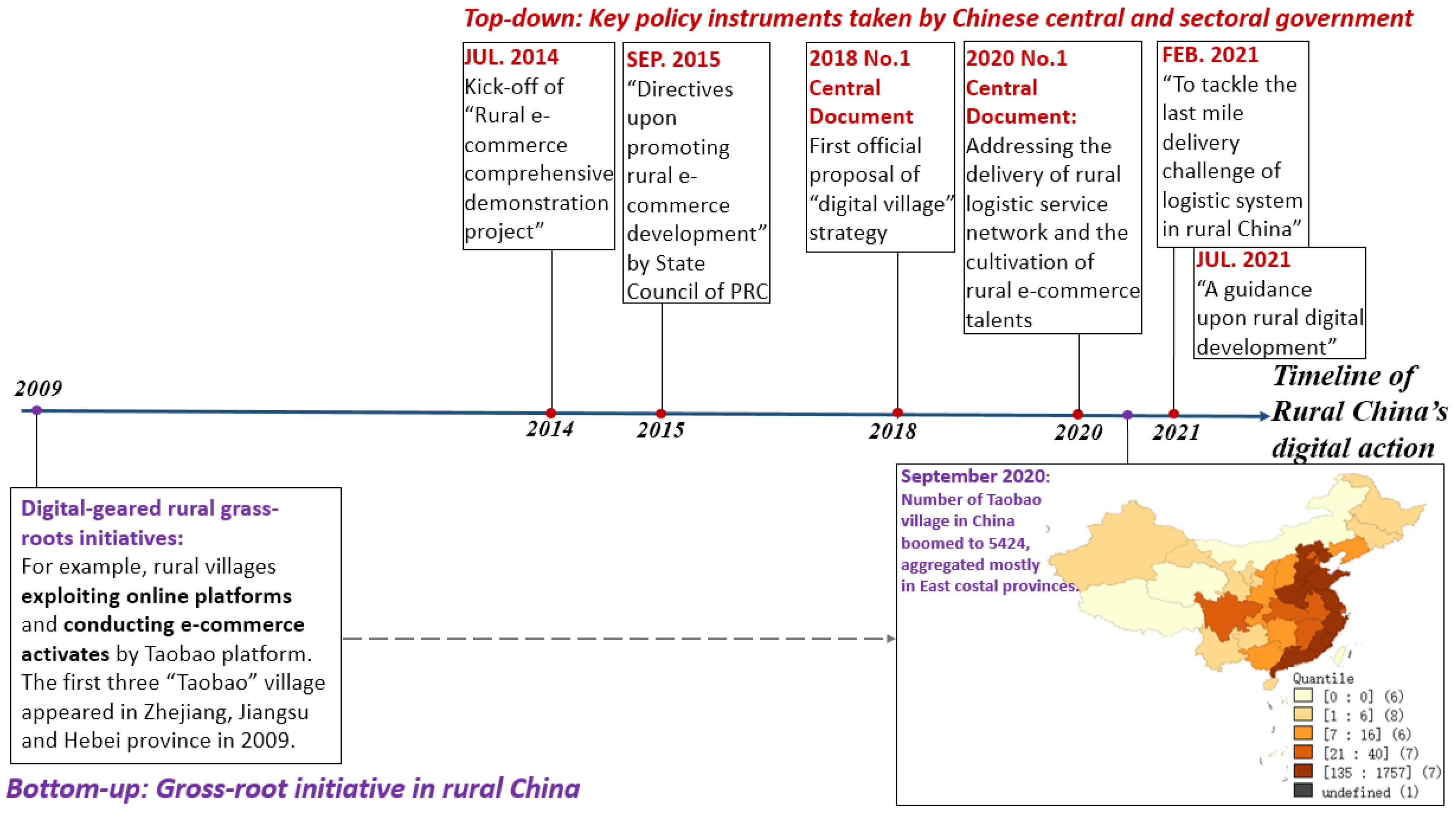

3.5. Rural China Embracing the Digital Era

- Improving rural society’s access to communication infrastructures, with telephone, television, and the internet included;

- Providing applications of communication infrastructures across various aspects of rural development, such as the websites of local government, the services stations at the village level, and agriculture information-related websites and e-commerce portals at the township and village levels.

4. Delineating Rural China’s Evolving Trajectories across Different Stages

- Evolution of rural development in China: from top-down to the emergence of top-down and bottom-up drivers

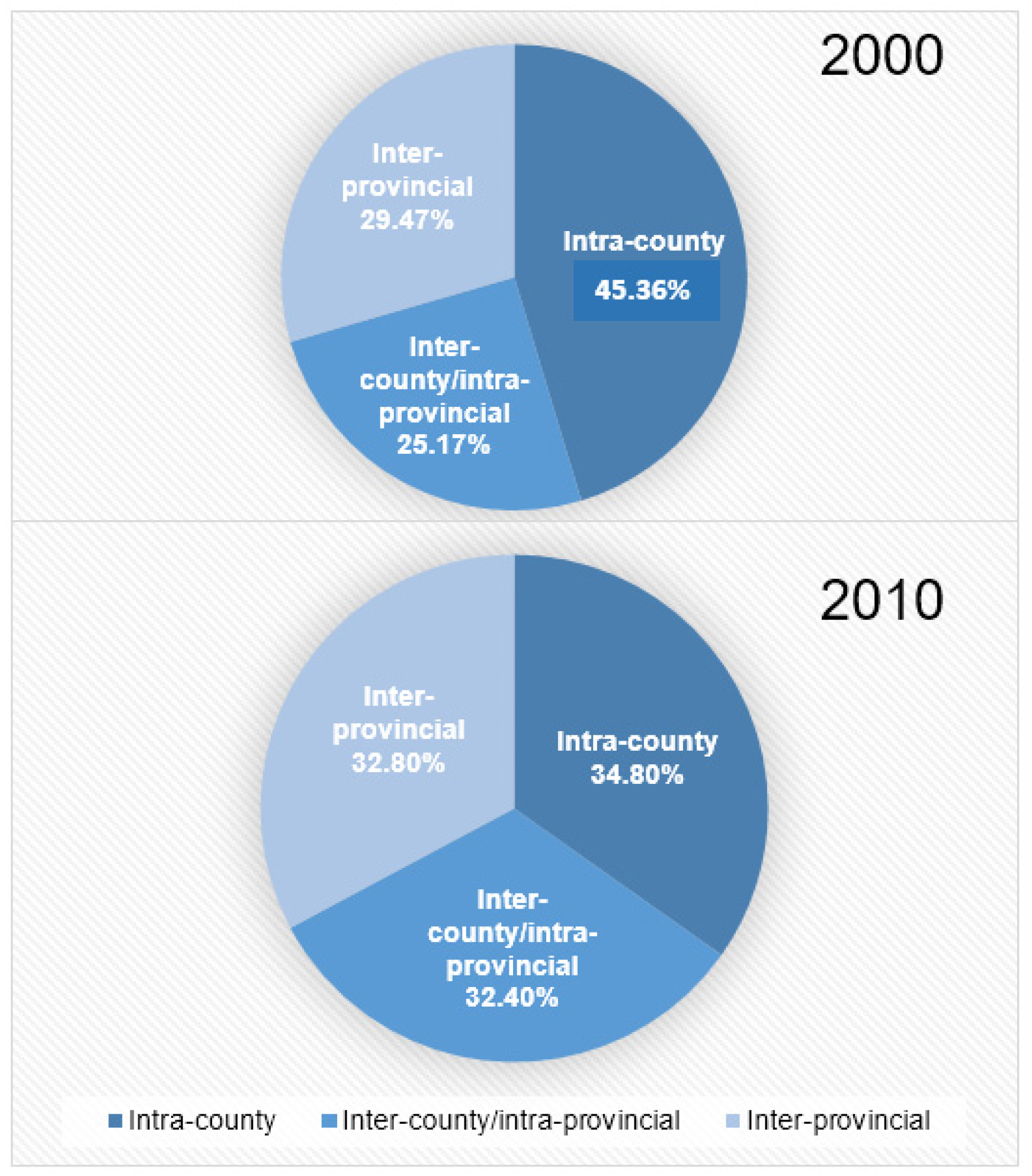

- Evolving trajectory of rural resident’s engagement in urbanisation

5. Restructuring of Rural Society Amidst the Digital Era in China

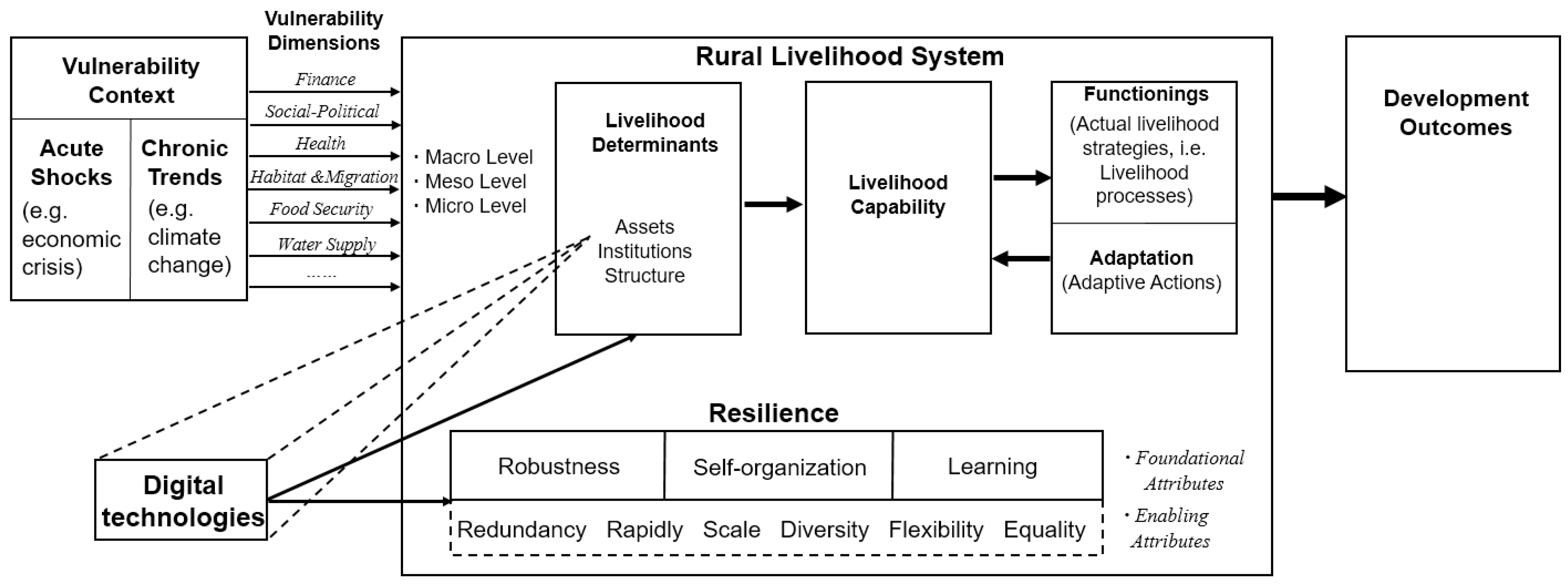

5.1. The Interplay of Digital Technologies and Rural Development: A Theoretical Understanding

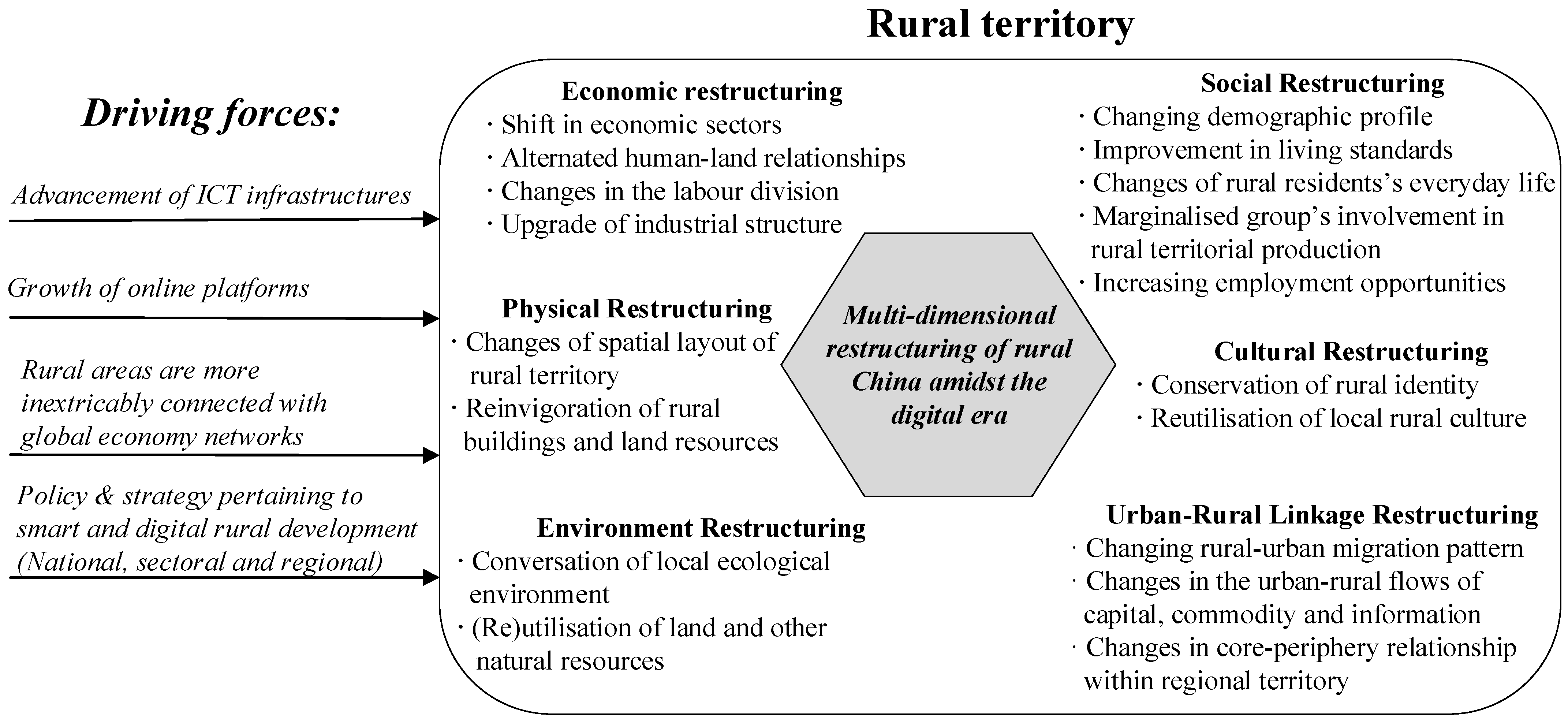

5.2. The Restructuring of Rural China amidst the Digital Era: An Explorative Analysis

6. Challenges, Policy Responses and Future Research Avenues

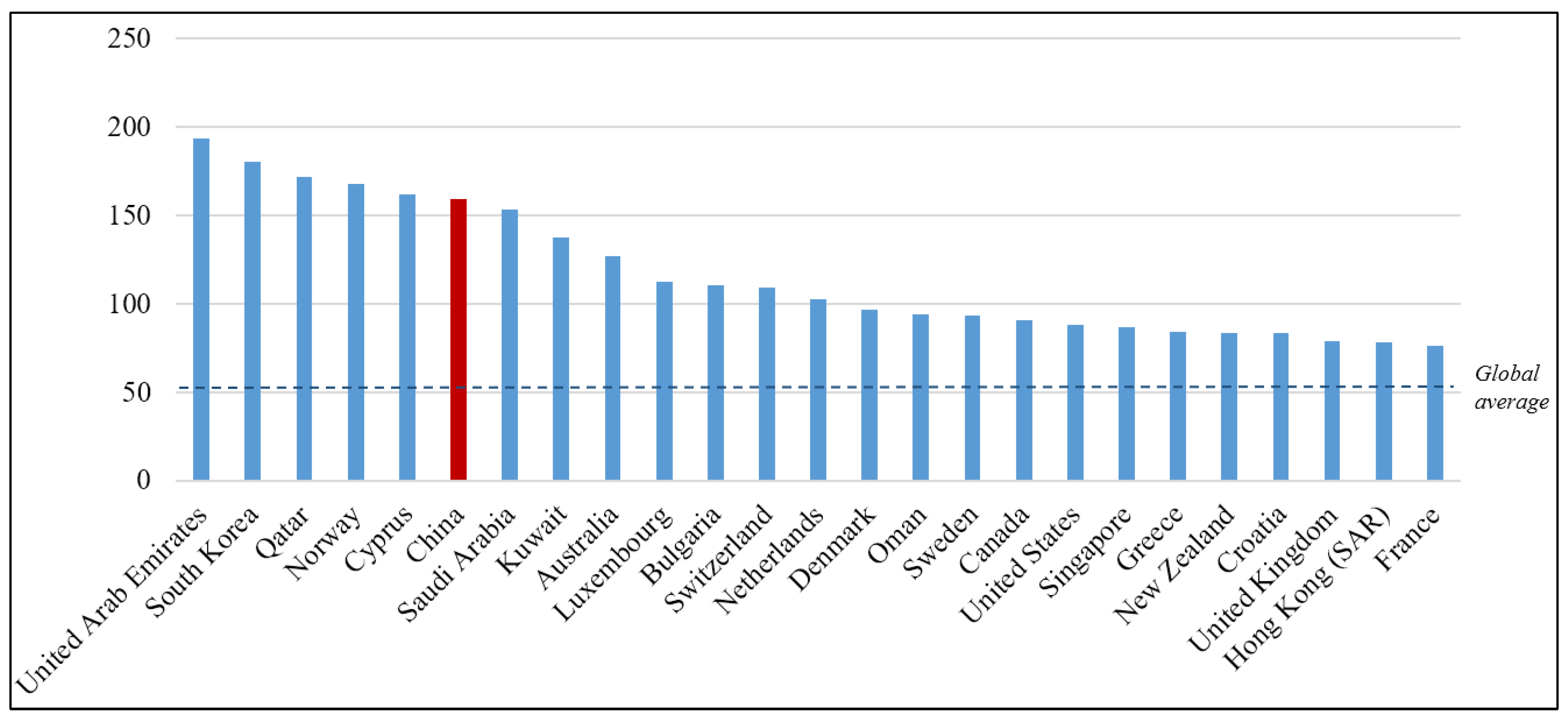

- Tackling the challenges of the “digital divide” between urban and rural areas

- Concluding remarks and future research avenues

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | State-owned enterprises, guoyou qiye; Rural people’s commune, renmin gongshe. |

| 2 | One archetypal case of rural household responsibility initiatives being widely reported is Xiaogang village in Anhui province. |

| 3 | For five consecutive years of 1982 to 1986, the State Council of China has published the “No.1 Central Document” to approve multi-reform policies for rural society. |

| 4 | Available via: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj2018/ (accessed on 1 January 2021) (In Chinese). |

| 5 | Available via: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-05/16/content_5392269.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021) (In Chinese). |

| 6 | Available via: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2020zyyhwj/2020zyyhwj/202002/t20200205_6336614.htm (accessed on 1 May 2021) (in Chinese). |

| 7 | Available via: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2021zyyhwj/2021nzyyhwj/ (accessed on 1 January 2022) (In Chinese). |

| 8 | Available via: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/25/content_5588715.htm (accessed on 1 March 2022) (In Chinese). |

| 9 | Available via: http://www.moa.gov.cn/hd/zqyj/202301/P020230104556857814615.pdf (accessed on1 March 2022) (In Chinese). |

| 10 | Information of Taobao village in China is collected from AliResearch (2020). Policy documents of Chinese central and sectoral government are collected via government website of State Council, CPC Central Committee, Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of PRC, available at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-11/09/content_10279.htm (accessed on 1 Janurary 2021), http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/jj2020zyyhwj/2020zyyhwj/202002/t20200205_6336614.htm, http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-02/25/content_5588715.htm, (accessed on 1 March 2021) http://www.cac.gov.cn/2021-09/03/c_1632256398120331.htm (accessed on 1 March 2022). |

References

- Pradhan, R.P.; Mallik, G.; Bagchi, T.P. Information communication technology (ICT) infrastructure and economic growth: A causality evinced by cross-country panel data. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2018, 30, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.K.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Akram, S.V.; Das, P.K. Village 4.0: Digitalization of village with smart internet of things technologies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 165, 107938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, H.; Ma, L.; Tu, S.; Li, Y.; Ge, D. Analysis of rural economic restructuring driven by e-commerce based on the space of flows: The case of Xiaying village in central China. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 93, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 45th China Statistical Report on Internet Development; CNNIC: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.R. The China dream is an urban dream: Assessing the CPC’s national new-type urbanization plan. J. Chin. Polit. Sci. 2015, 20, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, N.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Why small towns can not share the benefits of urbanization in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X. Challenges facing China’s unbalanced urbanization strategy. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y. Bottom-up initiatives and revival in the face of rural decline: Case studies from China and Sweden. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H. Rural restructuring in China: Theory, approaches and research prospect. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, D.; Qu, Y. Rural restructuring at village level under rapid urbanization in metropolitan suburbs of China and its implications for innovations in land use policy. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, L. Spatial–temporal changes of rurality driven by urbanization and industrialization: A case study of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area in Chongqing, China. Habitat Int. 2016, 51, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Woods, M.; Zou, J. Accelerated restructuring in rural China fueled by ‘increasing vs. decreasing balance’ land-use policy for dealing with hollowed villages. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zheng, C.; Guo, F.; Zhao, H.; Ma, S.; Cheng, Y. Spatial differentiation of digital rural development and influencing factors in the Yellow River Basin, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerli, P.; Whalley, J. Digital entrepreneurship in a rural context: The implications of the rural-urban digital divide. In Handbook of Digital Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK, 2022; pp. 291–305. [Google Scholar]

- He, X. Digital entrepreneurship solution to rural poverty: Theory, practice and policy implications. J. Dev. Entrep. 2019, 24, 1950004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Du, K.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.Y. Poverty alleviation through government-led e-commerce development in rural China: An activity theory perspective. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 914–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerli, P.; Whalley, J. Fibre to the countryside: A comparison of public and community initiatives tackling the rural digital divide in the UK. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, C.R. Entrepreneurs in the rural environment. J. Rural. Stud. 1989, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, Y. Urbanization for rural development: Spatial paradigm shifts toward inclusive urban-rural integrated development in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 71, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, H.T. Peasant Life in China: A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley; Routledge: London, UK, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, D.F. Deagrarianization and rural employment in sub-Saharan Africa: A sectoral perspective. World Dev. 1996, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. The Chinese hukou system at 50. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2009, 50, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, B. The new common economic program: China’s eleventh five year plan and what it means. China Leadersh. Monit. 2005, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.W.; Wei, Y. Two systems in one country: The origin, functions, and mechanisms of the rural-urban dual system in China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2019, 60, 422–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jia, L.; Wu, W.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Urbanization for rural sustainability–Rethinking China’s urbanization strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.W.; Tang, B.S.; Liu, J. Rethinking China’s Rural Revitalization from a Historical Perspective. J. Urban Hist. 2020, 48, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M. Economic Linkages of China’s Small Towns: Urban-Rural Integration in a Learning Economy; The University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, P. De-collectivisation of agriculture in China, 1979–1982: A long-term perspective. Camb. J. Econ. 1983, 3, 192–220. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Institution and inequality: The hukou system in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2005, 33, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1383–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T. Distortions of Agricultural Incentives; Indiana University: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H. Towards the Development of a Spatial Planning Framework for Rural Development in China: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. Rural development and rural to urban migration in China 1978–1990. Geoforum 1995, 26, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Whalley, J.; Zhu, L. The impact of China’s economic reforms on agricultural productivity growth. J. Polit. Econ. 1989, 97, 781–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X. The evolution of township and village enterprises (TVEs) in China. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of PRC. The History will not Forget the Great Contribution of TVEs. 2018. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/bmdt/201807/t20180731_6154959.htm (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Zhao, S.X.; Wong, K.K. The sustainability dilemma of China’s township and village enterprises: An analysis from spatial and functional perspectives. J. Rural. Stud. 2002, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Cars, G. Future urban-rural relationship in China: Comparison in a global context. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2010, 2, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoken, H.; Sato, H. Public policy and long-term trends in inequality in rural China, 1988–2013 (No. 2017-16); CHCP Working Paper; The University of Western Ontario, Centre for Human Capital and Productivity (CHCP): London, ON, Canada, 2017; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/180861 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Liu, T.; Qi, Y.; Cao, G.; Liu, H. Spatial patterns, driving forces, and urbanization effects of China’s internal migration: County-level analysis based on the 2000 and 2010 censuses. J. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 236–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Service and Management of Migrant Population, National Health and Family Planning Commission of China (DSMMP/NHFPCC). Report on China’s Migrant Population Development; China Population Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- State Council of China. No.1 Central Document. 2004. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/test/2006-02/22/content_207415.htm (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- Central Government of PRC. Decision of the CPC Central Committee on Several Major Issues Concerning the Construction of a Harmonious Socialist Society. 2006. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2006/content_453176.htm (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Qian, H.; Wong, C. Master planning under urban–rural integration: The case of Nanjing, China. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhan, P.; Shen, Y. New Patterns in China’s Rural Poverty (No. 2017-17); CHCP Working Paper; The University of Western Ontario: London, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of PRC. No.1 Central Document. 2010. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj/wjhg/201202/t20120215_2481486.htm (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Xia, J. Linking ICTs to rural development: China’s rural information policy. Gov. Inf. Q. 2010, 27, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of PRC. No.1 Central Document Upon the Promotion of Socialist New Villages by CPC Central Committee and State Council of PRC. 2006. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj/wjhg/201202/t20120214_2481239.htm (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 48th China Statistical Report on Internet Development; CNNIC: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of PRC. Opinions on Implementing the Rural Revitalization Strategy. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2018-02/04/content_5263807.htm (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. How do smart villages become a way to achieve sustainable development in rural areas? Smart village planning and practices in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AliResearch. Development Report of China’s Taobao Village; 2020. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- China Family Finance Investigation and Research Center. Rural Online Business Development Report. 2016. Available online: http://www.cbdio.com/BigData/2017-01/17/content_5433226.htm (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Zhu, Y. In situ urbanization in rural China: Case studies from Fujian Province. Dev. Change 2000, 31, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Shang, X.; Cui, Y.; Blaxland, M. Migration, Urbanisation, Climate Change and Children in China—Issues from a Child Rights Perspective; UNSW Social Policy Research Centre: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Shen, L.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shi, F. A novel evaluation method for urban infrastructures carrying capacity. Cities 2020, 105, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Q.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y. Addressing the rural in situ urbanization (RISU) in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region: Spatio-temporal pattern and driving mechanism. Cities 2018, 75, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qi, X.; Shao, H.; He, K. The evolution of China’s in situ urbanization and its planning and environmental implications: Case studies from Quanzhou municipality. In Urban Population-Environment Dynamics in the Developing World: Case Studies and Lessons Learned; Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 213–245. Available online: http://www.ciesin.columbia.edu/repository/pern/papers/urban_pde_zhu_etal.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Heeks, R. CT4D 2016: New Priorities for ICT4D Policy, Practice and WSIS in a Post-2015 World. Development Informatics Working Paper 2014. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3438431 (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- World Trade Organization (WTO). World Trade Report 2008: Trade in a Globalizing World; World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Best, M.L.; Maier, S. Gender, culture and ICT use in rural south India. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2007, 11, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R. ICTs and Poverty Eradication: Comparing Economic, Livelihoods and Capabilities Models. Development Informatics Working Paper 2014. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3438433 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Ng, B.K.; Wong, C.Y.; Santos MG, P. Grassroots innovation: Scenario, policy and governance. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 90, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, W.; Heeks, R. Impact of ICTs-in-Agriculture on Rural Resilience in Developing Countries. Development Informatics Working Paper 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3517468 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Ospina, A.V. Climate Change Adaptation and Developing Country Livelihoods: The Role of Information and Communication Technologies. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Guo, H.; Jin, S.; Ma, W.; Zeng, Y. Do farmers gain internet dividends from E-commerce adoption? Evidence from China. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Min, S.; Ma, W.; Liu, T. The adoption and impact of E-commerce in rural China: Application of an endogenous switching regression model. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Xie, X.; Lv, Z. Taobao practices, everyday life and emerging hybrid rurality in contemporary China. J. Rural. Stud. 2016, 47, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lv, B.; Wen, T. New Patterns of County In-Situ Urbanization and Rural Development Based on E-Commerce. Urban Plan. Int. 2015, 1, 14–21. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Cui, L. China’s e-commerce: Empowering rural women? China Q. 2019, 238, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Marafa, L. Tourism Imaginary and Landscape at Heritage Site: A Case in Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, China. Land 2021, 10, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Singh Chandel, R.B.; Xia, X. Analysis on regional differences and spatial convergence of digital village development level: Theory and evidence from China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, P.; Townsend, L.; Salemink, K. Smart rural futures: Will rural areas be left behind in the 4th industrial revolution? J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. The Evolution Model of and Factors Influencing Digital Villages: Evidence from Guangxi, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D. The participation society and its inability to correct the failure of market players to deliver adequate service levels in rural areas. Telecommun. Policy 2018, 42, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, S.; Zhang, J.; Furuya, K. Increased Attention to Smart Development in Rural Areas: A Scientometric Analysis of Smart Village Research. Land 2022, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Number of Townships | Year | Number of Townships |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 2361 | 1986 | 10,718 |

| 1980 | NA | 1987 | 11,103 |

| 1981 | 2678 | 1988 | 11,481 |

| 1982 | NA | 1989 | 11,873 |

| 1983 | 2968 | 1990 | 12,084 |

| 1984 | 7186 | 1991 | 12,455 |

| 1985 | 9140 | 1992 | 14,539 |

| 1982 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural– to–urban migrants (million) | 11.5 | 37.5 | 102.0 | 221.0 | 247.0 |

| As % of national population | 1.1 | 3.3 | 8.0 | 16.5 | 18.0 |

| Title, Published Governmental Body and Time of the Policy Strategy | Key Issues Addressed |

|---|---|

| 2018 No.1 Central Document “Opinions on implementing the rural revitalisation strategy”, by the State Council of the PRC (February 2018)4 |

|

| “Outline of the digital rural development strategy”, by the State Council of the PRC (May 2019)5 |

|

| 2020 No.1 Central Document “Directives on the key tasks for the issues of agriculture, countryside, and farmers to achieve the moderately prosperous society in all aspects”, by CPC Central Committee and State Council of the PRC (January 2020)6 |

|

| 2021 No.1 Central Document “Opinions on comprehensively promoting rural revitalization and accelerating agricultural and rural modernization”, by the State Council of PGR (January 2021)7 |

|

| “To ensure the last mile delivery of rural logistic system in China”, by the Ministry of Commerce of the PRC (February 2021)8 |

|

| “A guidance upon rural digital development”, by the State Council of the PRC (July 2021)9 |

|

| Key Features | Rural In-Situ Urbanisation 1.0 in the Reform Era | Rural In-Situ Urbanisation 2.0 in the Digital Era |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, Y. Rural China Staggering towards the Digital Era: Evolution and Restructuring. Land 2023, 12, 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071416

Ren Y. Rural China Staggering towards the Digital Era: Evolution and Restructuring. Land. 2023; 12(7):1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071416

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Yitian. 2023. "Rural China Staggering towards the Digital Era: Evolution and Restructuring" Land 12, no. 7: 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071416

APA StyleRen, Y. (2023). Rural China Staggering towards the Digital Era: Evolution and Restructuring. Land, 12(7), 1416. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071416